Abstract

This study investigates how a country’s promotion of its culture affects another country’s consumption patterns. We collected primary data from Malaysians about their exposure to Korean drama and consumption of Korean cosmetics in order to test whether the imaging of Korean cultural richness through the international marketing strategy termed Hallyu (entailing the use of Korean TV drama to image South Korea as a celebrated country) instigates conspicuous consumption in Malaysia. Respondents with higher levels of education but lower income watched Korean drama more intensively, and the intensity of watching Korean drama was positively associated with the consumption of Korean cosmetics. Our results highlight the ability to affect trade between countries by advertising through mass culture and exploiting the need for conspicuous consumption by those individuals experiencing perceived relative deprivation

Conspicuous consumption could be a key motivating factor to demand imported goods. When imports of entertainment manifest themselves as linchpins in everyday conversation and when knowledge of the most up-to-date developments of that entertainment is crucial in informing peers about an individual’s engagement with that entertainment, it becomes necessary to be conspicuous about entertainment viewing habits and display cultural engagement signals that positively affect an individual’s relative position in society. Veblen’s (Citation1899) argument that individuals need to actively display their wealth in order to gain status applies equally well to physical and cultural wealth; the aim of this study is to explore the intricate nature of this mechanism by examining the interaction between culture, psychological mechanisms, and the decision to purchase an import.

Entertainment, cultural emulation, and consumption patterns are inextricably linked (Veblen Citation1899; Scitovsky Citation1976; Bourdieu Citation1986), and capturing these interlinkages is crucial for understanding the socio-economic environment. Culture is difficult to define, its economic impact is difficult to measure (Pratt Citation1997), and no one conception of culture is likely to be fully appropriate (Duncan and Duncan, Citation2004), even though culture does matter for all socio-economic processes (Sahlins and Service Citation1960; Mayhew 1987; Tool Citation1990; Galbraith Citation1992; Jennings and Waller Citation1995; Waller Citation2003; Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales Citation2006; Fernandez Citation2011; Alesina and Giuliano Citation2015).Footnote1 We will use here the Culture-Based Development paradigm and its definition for culture as: “the ruling group of attitudes belonging to a critical mass of residents—typically the majority of the population in a locality” (Tubadji Citation2012 and Citation2013).Footnote2 From this vantage point, the current study investigates the effects of the aggressive promotion of South Korean mass culture in Malaysia (Dator and Seo Citation2004; Huat and Iwabuchi Citation2008) on Malaysians’ perceptions of the richness of Korean society and their consumption patterns. HallyuFootnote3 (sometimes referred to as the “Korean Wave”) is a term used to denote a complex marketing tool combining a range of cultural items that are communicated by Korea in international markets (Segers Citation2000). Hallyu has maneuvered Korean drama and mass culture (which Koreans themselves value higher than foreign culture, see Moon et al. Citation2015) into a fashionable brand of entertainment among the young generation in Malaysia. Korean drama exports were worth $250 million in 2018, with most trade going to Asia (70%) and the remaining going to the United States.Footnote4 South Korean is among the top ten global beauty markets and was worth more than US$13 billion in 2017 (Mintel Citation2017). Malaysia is the second largest purchasing power territory in Asia with a population over 32.4 million, of which about 78% belong to the middle and upper classes (Cosmetic Observatory of Malaysia Citation2021) who are also opulently concerned with their well-being and appearances. Six percent (US$ 63.2m) of Malaysia’s imports of beauty and skin care products in 2015 came from South Korea and this has been increasing at a rate of 1 percent per annum since 2013 (U.S. International Trade Administration Citation2016), but this steady growth is puzzling as there appears to be no product characteristics that directly justify its expansion. And further puzzles accompany this claim. For instance, Japan, which is arguably a very affluent country and a recognized world leader in cosmetics, does not enjoy the same success in the Malaysian market as Korea (Malaysia Cosmetic Observatory Citation2021). This is surprising from a trade theory perspective, as Japan is geographically proximate to Malaysia, and yet Japan does not rank among the top three countries shipping cosmetics into Malaysia, while South Korea does. South Korea’s history in cosmetics has been ahead of China and Japan, and some advertisements of Korean cosmetics build on this cultural persistence and insist on the qualitative differences between European (more aggressive) and South Korean (more natural and youth highlighting) styles (see Menon Citation2019). This study assesses whether there is an indirect association between the exposure to Korean drama and consumers’ tastes in Malaysia which creates a conspicuous consumption mechanism through art-based marketing intervention. If this is the case, this takes the link between marketing and conspicuous consumption to a whole new level of an intentional instrumental relationship, previously noted by David Hamilton (Citation1989) as an unintended or neglected consequence. Moreover, if there is credence in the intentional use of culture in marketing to create conspicuous consumption and boost sales, it becomes paramount to understand which consumers are exploited most by it. Our study answers these questions. Future comparisons between the international effects of Japanese and Chinese traditional and current prestige and the prestige of the Korean cosmetic industry on the Malaysian consumer merit future research.

Paola Manzini and Marco Mariotti (Citation2016) show theoretically that prominent product characteristics could lead consumers to choose inferior alternatives, especially when they are associated with salient positive externalities. We build on Manzini and Mariotti’s (2016) work by assuming that the positive externality could be a source of prestige that can be displayed to others. Exports of entertainment that highlight Korean mass culture and project an image of richness and superiority of the Korean lifestyle may strengthen the impression that a positive spillover is bestowed on an individual’s prestige when they consume Korean products. Our entire estimation strategy demonstrates that the Veblenian conspicuous consumption mechanism can be identified as crucial for model specification, and therefore standard neoclassical modelling leads to serious model under-specification.

Operationalizing an empirical investigation that ascertains whether watching Korean drama enhances the likelihood of consuming Korean cosmetics for conspicuous consumption motives is not without difficulties. In addition to parameterizing a model that assesses the association between the propensity to watch Korean drama and the probability of purchasing Korean cosmetic goods, we need to underpin this association with a selection model whereby only an individual who is concerned with prestige-related conspicuous consumption is more likely to watch Korean drama. An appropriate empirical modelling solution to this estimation challenge is to combine standard regressions with a Heckman selection model, and we operationalize the model using primary data collected specifically for this purpose. We collected data on a sample of 252 (predominantly female) Malaysian consumers using a survey that contained questions about their intensity of exposure to Korean drama, preferences about Korean cosmetics, perceptions of Korean lifestyle, and self-perceptions about their own life satisfaction, happiness, and relative socio-economic positioning.Footnote5

The results suggest that Malaysians perceive Korean lifestyle to be culturally richer than in Malaysia, which encourages them to consume Korean goods as this conveys perceptions of prestige. Respondents with higher levels of education and lower wages watched more Korean drama, and their intensity of watching Korean drama was positively associated with their consumption of Korean cosmetics. Although respondents generally did not view Korean society as being culturally richer or more affluent than in Malaysia, they did view it as more financially prosperous, and hence the consumption of Korean cosmetics is a conspicuous consumption that is more likely to be motivated by relative income than the search for moral prestige.

In addition to being the first academic study to illustrate the effect of Hallyu on conspicuous consumption, this article emphasizes that the international transfer of tastes and cultural norms can enhance foreign trade even when products do not have a quality advantage and that the promotion of mass culture can create a positive spillover in the form of additional social status. These findings corroborate the Culture-Based Development (CBD) concept (Tubadji Citation2012 and Citation2013) which extends the understanding that culture affects economic outcomes (a stand maintained by many institutional and evolutionary contributions, such as Sahlins and Service Citation1960; Mayhew 1987; Tool Citation1990; Galbraith Citation1992; Jennings and Waller Citation1995; and Waller Citation2003). Yet, CBD brings the synthesis regarding the impact of culture a step further by positing that culture is not only historically inherited (i.e., affected by cultural heritage) but is also endogenously man-made in the current moment (i.e., affected by living culture) and, in line with Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1979), its valuation and impact on social closure varies across these two types in an important manner (see Tubadji Citation2012 and Citation2013; and Tubadji et al. Citation2022).

The next section reviews the literature on consumption, value, and price through social and cultural origins, and clarifies the CBD model linking mass culture with conspicuous consumption. The following two sections describe respectively the primary dataset and the estimation strategy. The pre-last section summarizes the results and analytical interpretations and the paper ends with a concluding section.

Consumption and Value

The mainstream economics perception is that the price of a product reflects its market value (Mankiw Citation2011) where this monetary value is determined by production costs, productive efficiency, and objective product characteristics (Lancaster Citation1966). The classical paradigm is that higher price signifies higher product quality and reflects its success in responding to consumer needs (Chi, Yeh and Huang Citation2009 Tariq et al. Citation2013), but it does not illustrate the variation in utility that each individual might receive from the good or the differences across individuals’ willingness to pay for the product (Seton Citation1957).Footnote6 One way to explore the consumer valuation of a product beyond the observable equilibrium price is to employ a willingness-to-pay approach using survey data (see, for example, Throsby Citation1984 and Snowball Citation2008). The reliance on self-reported pricing data is increasing in traction as a valid research approach.

The valuation of product characteristics differs according to the consumers’ needs and their socio-economic and demographic characteristics, such as age (Abdu Gianie Citation2013) and income (Chen and Seock Citation2014). Individual lifestyle also predicts buying behavior, with a consumer who has a habit of using beauty products being more willing to purchase them at a higher price or purchase more types of beauty products and being more demanding about objective product characteristics (Abdu Gianie Citation2013). Lifestyles are products of a complex social construction (Bourdieu Citation1979). Linda McDowell (Citation1997) argues that the economy and society has evolved such that the post-industrial middle class has cultural capital and middleclass values of the established bourgeoisie but did not attend elite universities or read established degree subjects. This new middleclass became the mass elite and formed mass audiences for mutually recognized high cultural objects, including films and television (Lash Citation1990).

The literature reveals further intricacies of the pricing mechanism, such as the saliency of branding as a factor for consumers’ emotional engagement (Erics et al. Citation2012; Gogoi Citation2013; Tih and Lee Citation2013; Dursun et al. Citation2011).Footnote7 Branding is a link between the objective and subjective functions of consumer choice and plays a prominent role in creating loyal consumers and retaining companies’ market share (Arslan and Altuna Citation2010; Irshad Citation2012).

Based on the above, it is clear that any analysis of product valuation should account for both the relative importance of objective product characteristics and consumer-specific subjective valuations after controlling for demographic market segmentation. Yet, subjective valuations are intricate and strongly influenced by social factors that vary by location, culture, and exposure to shaping factors such as advertisement.

Social Factors Governing Consumption

Social factors influence consumption patterns and are a vector of socially constructed conditions that reflect subjective valuations of a product beyond its production cost. Classical Veblenian scholars (Veblen Citation1899; Hamilton Citation1973; Trigg Citation2001) and various studies from related disciplines (Thøgersen and Zhou Citation2012; Wilkinson and Klaes Citation2012) find that people seek social approval before purchasing a new product.

The study of social factors in pricing and choice has been advanced in the realms of willingness-to-pay surveys (McFadden Citation1997), contingent valuation methods (Snowball Citation2008), and hedonic models (Palmquist Citation1984). Hedonic price models can reveal the impacts of context and space within a classical econometric setting, since they focus on the empirical exploration of consumers’ utility functions and their determinants rather than imposing a fixed set of components. This more open exploration of consumer motivations sanctions estimations of the prominence of social factors in determining choice (Orford Citation2000).

Individual perceptions of product value operate within powerful and multifaceted social confines. Here we focus on one classic example of social influence suggested by Veblen (Citation1899), where the consumption and valuation of products are driven by social perceptions of prestige and richness or relatedness to one’s reference group(s).Footnote8 Veblen suggested that conspicuous consumption is associated with higher product prices because the higher price provides more salient markers of affluence (Veblen Citation1899), which unlocks the possibility that a product’s market price is an endogenous consumption factor. In this sense, Veblenian goods can be understood from Manzini and Mariotti’s (2016) perspective, as products that yield utility both through their direct product characteristics and through their indirect spillovers in the forms of social recognition and prestige.

Consumption of cultural goods is claimed to be a powerful illustration of social forces. According to Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1986), culture influences people’s thoughts and tastes and people associate with the culture of the society to which they belong. Belonging to a society or a group manifests itself through the consumption of its culturally valued goods, which ensures the transmission of cultural capital across generations and determines how our society perceives us.

Conspicuous consumption can be understood better when Veblen’s work is read through the lens of Bourdieu’s notions of social construct and distinction (Trigg Citation2001). Bourdieu interprets the consumption of certain goods as a source of distinction based on cultural capital, such as valuing a particular language/dialect based on class belonging. Veblen adopted the same reasoning by claiming conspicuous consumption is driven by “knowledge” (Veblen Citation1899, 45), whereas Bourdieu calls it “habitus” (i.e., the knowledge of a certain field of social life that one has inherited as cultural capital from one’s parents’ experience in this field of social life). According to both Veblen and Bourdieu, this “knowledge” embodies a socially constructed value that is dissociated from direct objective merit and is bestowed entirely based on social valuation of the culture and knowledge typical of a particular social group (Trigg Citation2001).

Here we interpret Bourdieu’s (Citation1986) cultural capital perspective from the viewpoint of Veblen’s conspicuous consumption perspective, and do so through the CBD lens (Tubadji Citation2012 and Citation2013). The CBD approach emphasizes the endogeneity and inequality related implications of conspicuous consumption. Explicitly, Malaysians are interpreted as economically consuming Korean mass culture as it nurtures a prestigious cultural capital association with Korean lifestyle. A special class of socio-economically vulnerable people are suggested as victims of this intentional endogenous cultural advertisement, though this group is not the newly rising rich as with Veblen but quite another relatively deprived group: the “Sour Grape” consumers.Footnote9

Sour Grapes

Building on Bourdieu’s classical theory of the leisure class, and following Trigg (Citation2001), the CBD approach suggests a general Sour Grape mechanism underpinning conspicuous consumption that makes it empirically explicit why it is synonymous with different lifestyles and is endogenous to advertisements. Daniel Gilbert et al. (Citation1998) postulate that individuals have a psychological immune system that enables them to adjust to problematic events by attuning their subjective expectations towards existing conditions and depreciating alternatives. Evidence confirms that such adaptation is typical behavior of ordinary, healthy individuals who aim to limit emotional costs of negative circumstances and expand the hedonic pleasure derived from consumption and experiencesFootnote10 (Taylor and Brown Citation1988; Lyubomirsky and Ross Citation1999).Footnote11

Grounded on this type of economic and psychological evidence, Annie Tubadji and Steve Pratt (Citation2019) proposed a Sour Grape mechanism where conspicuous consumption is triggered when an individual feels relatively worse off in a particular socio-economic dimension (specifically when they perceive they have relative deprivationFootnote12): individuals conspicuously consume by trading off sorrow for objects with socially salient characteristics. The Sour Grapes mechanism represents a group of evolutionary psychological processes based on the tendency of the human mind to bring preferences in line with an individual’s circumstances and is a defense mechanism that preserves people’s psychological and social stability (Kay, Jimenez, and Jost Citation2002); hence, conspicuous consumption can be influenced by a consumer’s exposure to mass culture and the wider social receptiveness towards a product. We formalize the above theory into a system of equations built around the CBD model, such that:

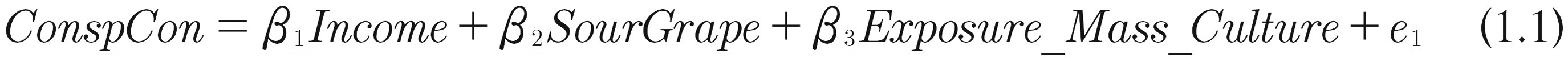

where ConspCon is the propensity to consume conspicuously, Income is a vector of socio-economic variables reflecting the income of the person available for a type of product, SourGrape is the psychological state of the individual’s feelings towards a disadvantaged socio-economic position relative to their reference group, Exposure_Mass_Culture is the degree of exposure to mass culture from the exporting country (which makes the consumption economically endogenous to economically driven advertisements), Cons is the individual’s level of consumption of a product, Product is a vector of objective product characteristics, Social is a vector of social factors (such as the opinions by peers, family, friends, etc. in the spirit of Veblen-Bourdieu’s cultural and social capital influences), Imports is the aggregate quantity of imports of a particular good from different countries, and Physical distance and Cultural distance are the geographical distance and the difference in attitudes respectively between importing and exporting countries under analysis. Equations (1.1) and (1.2) describe a micro mechanism that generates an aggregate effect expressed in equation (1.3). Our empirical analysis focuses on the operationalization of individual level mechanisms in the CBD model—equation (1.1) and (1.2)—because our data corresponds to one recipient country, Malaysia, and one sending country, Korea; thus, in our empirical model, physical and cultural distance in equation (1.3) are constant at the aggregate level.

Data

Quantitative data were collected in 2018 using a survey posted online via a Google Form and the questionnaire link posted at relevant Malaysian Facebook pages. Specific Facebook pages were targeted in order to ensure that the Malaysian sample had a sufficient number of respondents with high levels of interest in Korean pop culture.Footnote13 We chose to adopt a broad definition of Korean pop culture when establishing the data sample and chose not to select Facebook pages that attracted Malaysians who had a specific interest in Korean drama because of the potential lack of variation in the sample’s viewing habits of Korean drama. A total of 252 respondents completed the questionnaire.

Using online survey data has its strengths and weaknesses. Although we do not claim the data to be fully representative of the Malaysian population, there are obvious benefits of employing this methodological approach including that the ability of respondents to contribute to the study is open to all internet-connected Malaysians and therefore there is the potential to gain scale and reach while maintaining anonymity. Participation by the respondent is flexible, at their convenience, time efficient and cost effective. The data maybe more valid than data collected via interview and in-person surveys because inherent anonymity should eliminate interviewer bias and enhance objectivity in responses. Inevitably, there will be self-selection due to voluntarily responding to and answering questionnaires per se and self-selection into accessing the website initially. We account for potential self-selection bias by utilizing a Heckman selection model.

The survey contained thirty-two questions and focused on gathering information on the type of Malaysians who purchase Korean cosmetic products (buy_fromK), their willingness to pay for an objectively top quality product (price_criteria_all), product country of origin, and their watching habits of Korean drama (watch_K_drama). The main dependent variable, buy_fromK, reflects the propensity to buy a cosmetic product from Korea while the main explanatory variable, watch_K_drama, captures the frequency of watching Korean drama; both are captured on Likert scales. The other main explanatory variable is the price that the respondents were willing to pay for a cosmetic product that fulfills a list of objective product quality characteristics typically relevant for the Malaysian market, such as anti-acne, anti-aging, moisturizing, oil control, pore care, and face whitening; this price question was open ended, and answers ranged from RM18 to RM1000.Footnote14 Details of all variables included in the analysis are provided in the appendix.

Another set of important variables for our analysis are Veblenian_consumer and Non_Veblenian_consumer, which are dummy variables reflecting whether the respondent thought they would be esteemed if they purchased a product that was in a Korean drama. We have control variables such as the perception of Korean style (style_K_better and style_K_NOT_better) that reflect whether the respondent thinks Korean style is relatively better than Malaysian style, and we use controls for objective product characteristics, interviewee demographics, and happiness.Footnote15

An important issue is whether Veblenian consumers are strictly the people who buy cosmetic products from Korea. There is a correlation between these variables of 0.3196 suggesting some Veblenian consumers do buy cosmetic products from Korea, but this value is not particularly high and pairwise t-tests reveal that these two variables are reflecting significantly different things.

We have data from one country (Malaysia) and are unable to identify cross-country differences in tastes, but the findings are relevant for improving understanding of the mechanisms through which an exporting country’s mass culture can influence an importing country’s consumers’ perceptions of cultural proximity, shape their consumption habits in favor of exported products, and trigger conspicuous consumption towards these products. This case study is particularly pertinent because the cultural effect may be creating abnormally high sales, not because of superior product characteristics but because the product may be perceived as a Veblen-type prestige good simply because of its country of origin.

Hypotheses and Estimation Method

Given the underlying literature and primary data, we have four working hypotheses.

• H01: The propensity to buy Korean cosmetics depends on watching Korean drama

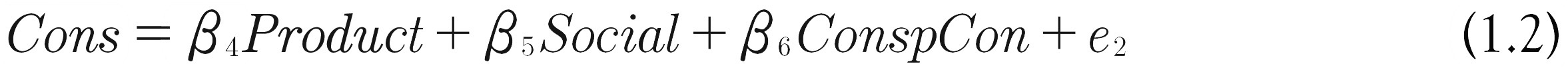

Hypothesis 1 is operationalized as:

where the likelihood of buying a cosmetic product from Korea (Buy_fromK) is determined by the frequency of watching Korean drama (Watch_K_drama) and a vector of demographic and control variables, X.

• H02 (willingness to pay): People are willing to pay more for higher quality cosmetic products if they come from Korea.

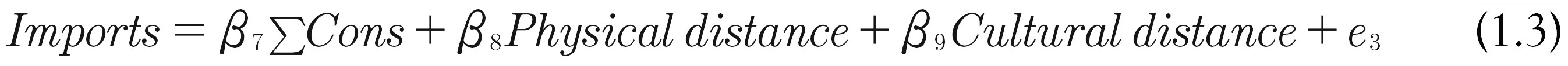

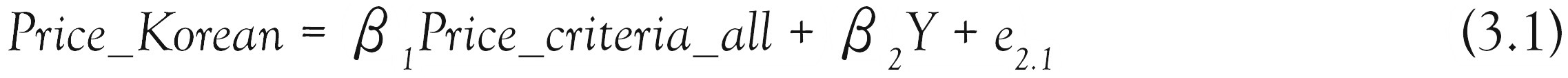

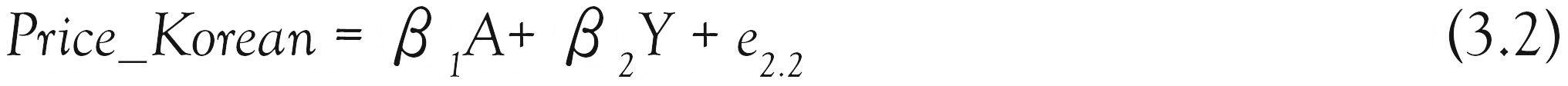

Hypothesis 2 captures the impact of the objective product characteristics on the consumption of Korean products. The operational model for testing H02 compares the results of two independent OLS estimations of models (3.1) and (3.2):

In equation (3.1), the price that the respondent is willing to pay for a Korean cosmetic product (Price_Korean) is determined by the price that the individual would pay for a cosmetic product that fulfils all of their attribute needs (Price_criteria_all). In equation (3.2), the same dependent variable is determined by A, which is a vector of objective quality product attributes (such as treatment for acne, anti-aging, moisturizing, pore care, oil control, and skin whitening). Demographic controls, Y, are present in both cases. If the valuation of Korean cosmetics is objective, then Price_criteria_all and A should not differ significantly in terms of their effects on the price that the consumer is willing to pay for Korean cosmetics.

• H03 (Conspicuous Consumption): People are more likely to buy Korean cosmetic products when they perceive Korea as a more affluent country.

Hypothesis 3 reflects the impact of conspicuous consumption on the consumption of Korean cosmetics in the CBD model, which is operationalized as:

The model in equation (4) relates the likelihood of buying a Korean product (Buy_fromK) to the perception of Korea as a richer country (K_Richer), a vector of perceptions of Korea as an affluent society (Affluent) including perceptions regarding the skill level, professionalism, and lifestyle of Koreans. We control for a vector of individual factors, D, which include the sensitivity of consumer preferences to fashion, advertisement exposure and preferences of the respondent’s family members.

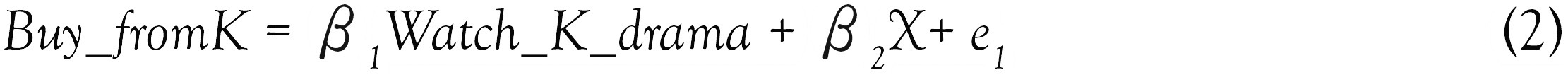

• H04 (Sour Grapes—relative deprivation): People watch more Korean drama when they are underpaid for their educational level

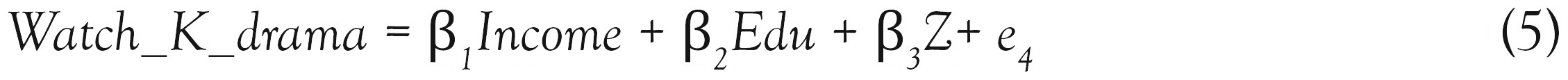

Hypothesis 4 captures the impact of relative deprivation (i.e. the Sour Grape effect) in equation 1.1 of our model, and is operationalized as:

In equation (5), the likelihood of watching Korean drama (Watch_K_drama) is predicted by the respondent’s income and education as well as demographic controls, Z. Equation (5) presents the test of the direct association between watching Korean drama and conspicuous consumption of Korean cosmetics, and this allows us to explore indirect implications of the Sour Grape effect by examining dependencies between income, education, and life satisfaction.

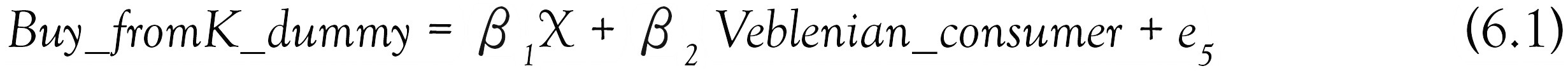

Finally, we estimate H01 and H04 simultaneously by employing a Heckman selection model described in equations (6.1) and (6.2), such that:

where being vulnerable to conspicuous consumption (Veblenian_consumer) in equation (6.1) pre-selects those who buy Korean cosmetics after watching more frequently Korean drama (buy_fromK_dummy). In equation (6.2), product characteristics, Y, and the intensity of watching Korean drama, Watch_K_drama (cleaned from pre-selection through the use of equation 6.1), are posed as objective and emotive factors for purchasing Korean cosmetics. If there is evidence for such pre-selection, then the estimation of Heckman’s selection model will reveal significance in the pre-selection equation (6.1) and eliminate this effect in the model that tests whether the intensity of watching Korean drama affects the purchasing of Korean cosmetics (equation 6.2).

Results

An inspection of the data reveals that most respondents were female higher education students in their early to mid-twenties. Data for the main dependent variable, buy_fromK, indicates that the sample includes individuals with a high propensity to buy a cosmetic product from South Korea. The second dependent variable, Price_criteria_all, has an average value of RM96.44, which is in line with the International Trade Administration’s (2016) observation that the average price of cosmetic products of this kind in Malaysia is around RM55 (mass market) and RM145 (premium). The first main independent variable, watch_K_drama, reveals that the average respondent watches Korean drama quite frequently.

The variables Veblenian_consumer and Non_Veblenian_consumer show that 22 percent of respondents are not motivated by conspicuous consumption motives, while 37 percent are. Sixty-five percent of respondents stated that Korean style is better than the local Malaysian style, with only 3 percent stating that Korean style was inferior for them. Thus, the descriptive statistics indicate a high propensity to buy Korean products and a high willingness to pay for them, and yet there remains the critical question whether there is a relationship between the objective qualities of Korean cosmetic products and the price the consumer is willing to pay for that product, or whether this relationship is merely a function of the exposure to Korean drama and the advertisement of Korean products which trigger conspicuous consumption.

The Effect of Watching Korean Drama on the Propensity to Buy Korean Cosmetics

H01 suggests an association between watching Korean drama and the propensity to buy Korean cosmetics. presents the results of a test of the direct association between our dependent and main independent variable with and without additional control variables. The results show a statistically significant association between watching Korean drama and the likelihood of buying Korean cosmetics. Consumer behavior seems dependent on lower income and higher education, and people who receive lower pay relative to their education category are likely to watch Korean drama more often. People who are better educated but paid less are the ones who seek to consume Korean cosmetic products, which corroborates our relative deprivation hypothesis.

Table 1. Basic Hypothesis

Willingness-to-Pay for Korean Cosmetics and Watching Korean Drama

presents the results of tests associated with H02, which corresponds to the importance of price and product attributes on the willingness to pay for Korean cosmetics. Respondents are generally willing to pay equal amounts for a Korean product and a product that responds to their demands for all product characteristics, suggesting that people perceive Korean cosmetics to be genuinely higher quality. The anti-aging attribute seems to be the most important factor that enhances the willingness to pay for Korean cosmetics. However, the willingness to pay a higher price for Korean cosmetics is associated with professional occupations and office workers, while students are willing to pay more than any other categories of buyers for high quality products. This could mean that higher educated people value Korean cosmetics more, as our previous findings suggest, especially when these people do not have high incomes.

Table 2. Willingness to Pay for Korean Products

Inspection of the correlation table (not shown for brevity - but included in the supplementary material for the editor and referees) reveals that age is associated with higher pay but not with higher education, and females in our dataset are predominantly young, which suggests that young females have lower incomes than other respondents. As the gender pay gap is a known phenomenon in Malaysia (Arshad and Ghani Citation2015), these correlations demonstrate that our results are intuitively appealing and valid. The result confirms the relevance of our use of demographic controls for gender and age, and gives an insight into the income disadvantage of young females.

Conspicuous Consumption of Korean Cosmetics

Social factors may influence the decision to consume Korean cosmetics, and social factors may be sensitive to the frequency of watching Korean drama. We capture alternative attitudes towards Korean cosmetics, such as Korea being perceived as a richer country, the respondent having a Veblenian predisposition, as well as perceptions of Korean quality of life, expertise, and style. Further, we test whether advertisements and fashion influence the decision to consume Korean cosmetics.

Our findings reveal that a Malaysian’s perception of the richness of Korean society, its fashion, style, and advertisement are all statistically significant predictors of an individual’s consumption of Korean cosmetics. However, views about Korean expertise and quality of social life are not important for this type of consumption. These results corroborate the view that the consumption of Korean cosmetics in Malaysia is an act of conspicuous consumption, and the results remain stable even after introducing demographic controls. The results imply that inserting advertisements and details of mass culture into Korean drama, either embedded within programs or in advertisement breaks, could strongly affect people with a propensity to consume conspicuously. An individual’s perception of Korean social affluence seems to affect their Korean cosmetics consumption decision more than do their family members’ consumption patterns. This suggests again that buying Korean cosmetics is associated with the need to create relations with a higher social circle and is not governed by herding behavior through immediate peer effects or stable friendships. See below.

Table 3a. Conspicuous Consumption

Table 3b. Conspicuous Consumption with Controls

Sour Grape Effects

We are interested in understanding in more depth the direct and indirect motivations to watch Korean drama and wish to understand which people conspicuously consume Korean cosmetics. Consuming Korean drama could be a compensatory mechanism for deriving the pleasure in life that is missing in some important aspect of life, such as income, education, the meritocratic match between education and income, or general life satisfaction. The illusionary narrative of the Korean drama helps an individual alleviate the pain of the immediate reality in which they live. The Sour Grape effect occurs when an individual conspicuously consumes a source of pleasure that alleviates the pain from an alternative unattainable reality, and make it part of their life physically. In this case, the consumption of Korean cosmetics is a type of conspicuous consumption geared towards alleviating the dissatisfaction from being an underpaid, highly educated individual, where the dissatisfaction associated with lower wages is offset by the consumption of Korean cosmetics.

The direct effects from income, education, and life satisfaction on the propensity to watch Korean drama are explored in , which illustrates that watching Korean drama is strongly negatively associated with income and strongly positively associated with education, which are consistent with our results above. However, when we introduce the controls for gender and age the statistical significance disappears for income and education, suggesting that the females in our dataset are younger and receive lower pay.

Table 4. “Sour Grape” Effect–Direct

reveals that both income and education positively affect life satisfaction. However, in our dataset there is little correlation between education and income (0.03). Given that our respondents are mostly women, and that most of our occupation controls have negative signs, we interpret these findings as evidence consistent with the literature of the gender pay gap in Malaysia (Arshad and Ghani Citation2015). Underpaid young women watch more Korean drama and buy more Korean cosmetics, which corroborates the compensatory effect for perceived relative deprivation, as suggested by the Sour Grape effect.Footnote16

Table 5. “Sour Grape” Effect–Indirect

Sour Grape Pre-Selection into Conspicuous Consumption

Malaysian individuals who are sensitive to social opinion and prone to conspicuous consumption (whom we already found to watch more Korean drama) may select into consuming more Korean cosmetics. We examine this proposition using Heckman’s selection model and the results are shown in . Specification 1 reveals that buying Korean products is a function of objective product characteristics and watching Korean drama, with the effect of Korean mass culture having the most prominent statistically significant effect. However, specification 2, where we control for the pre-selection of people sensitive to conspicuous consumption, removes the effect of watching Korean drama on the sales of Korean cosmetics. We interpret this result as evidence that conspicuous consumption is triggered by individuals who already suffer the Sour Grape effect and are in need of an illusionary substitution for their reduced set of capabilities, such that they consume more goods with positive spillovers on their own social image. Korean exporters benefit from conspicuous consumption tendencies in the Malaysian market.

Table 6. Heckman Selection Model—”Sour Grape” Pre-selection

The above analysis reveals that the category of people who respond to the marketing brand appeal of conspicuous consumption are a group whose identification is rooted in deprived socio-economic positioning and represent a victimization of the weak among the consumers, even in a straightforward Benthamian pleasure and pain setting (i.e., a setting where the consumer is assumed to operate for maximizing one’s own pleasure). This finding demonstrates that the existence of the market for conspicuous consumption does get marketeers an “F” for their social function, when profit-maximizing with regard to conspicuous consumption, as stated by Hamilton (Citation1989). Furthermore, it shows that this is not just a difficult to detect side-effect, but a clearly testable and documentable empirical observation.

Conclusion

This article presented the results of research designed specifically to investigate the influence of mass culture on conspicuous consumption and the decision to purchase imports. It explored a conspicuous consumption microeconomic mechanism underpinning international trade and set within a Culture-Based Development model. This mechanism allows for the aggregate market level tendency for exporters to use culture-based approaches to exploit foreign markets. We show that exporters can exploit individual consumers in foreign markets who are in psychologically vulnerable positions due to a mismatch between their aspirations and their achievements. Specifically, the aims of this study were to explore the interaction between culture and psychological factors and to assess whether mass culture drove the conspicuous consumption of Korean cosmetics in Malaysia.

We collected primary data to enable a focus on the effects of South Korea’s mass culture policy in the Malaysian market, often referred to as Hallyu, or the Korean Wave, on the demand for Korean cosmetic imports. We adapted Veblen’s (Citation1899) argument that individuals need to actively display their financial wealth (in order to gain status): our adaptation suggests that Veblen’s theory applies equally to the needs of individuals to display their cultural wealth in order to gain status. Consumers do this by demonstrating their knowledge and association with products that are purchased from a wealthier foreign country that is deemed to have a lifestyle that is of a higher quality (an effect that is termed in behavior economics as the “magical contagion effect” [Fernandez and Lastovicka Citation2011]).

Our analysis devoted separate attention to different facets of the relationship between consumption patterns of Korean cosmetics, their valuation from objective and emotive viewpoints, and the complexity of the link between these variables. We placed specific attention on consumers’ psychological needs and estimated the importance of the pre-selection of individuals into a particular lifestyle pattern. Our empirical results revealed that the importance of mass culture entertainment on the cosmetic purchasing decision was higher for people with high social aspirations but lower income. Consumption of Korean cosmetics were greater for individuals who watched Korean drama more frequently, and these individuals are the ones who were most vulnerable to the need for conspicuous consumption according to their self-reported responsiveness to Veblenian goods.

Our respondents generally viewed Korean society as richer though not necessarily more affluent than Malaysia, which means that the consumption of Korean cosmetics is the result of conspicuous consumption forces that are more likely to be driven by relative income motivations than the search for prestige. These results are generalizable under the Culture-Based Development notion of the Sour Grape effect, which posits that conspicuous consumption is heterogeneous in nature since it is more prominent for those individuals who are facing a mismatch between their aspirations and achievements.

More broadly, our results suggest that if an exporting country combines its export strategy with the promotion of a favorable lifestyle, then this may positively affect its outgoing trade flows. The success of this promotional strategy will be driven not only by social proximity and the similarity of cultures but also by the exploitation of a Sour Grape effect that gives rise to the conspicuous consumption of normal goods that are made salient through positive spillovers associated with richness, affluence, and/or prestige. Individual-specific mismatches between aspirations for higher income, higher affluence, and/or higher prestige drive the need for the individual to gain compensation through conspicuous consumption. The impact of South Korea’s mass culture policy on the Malaysian market is an illustration of a more general tendency where exporters use existing culture-based mechanisms to exploit consumers in foreign markets who have a mismatch between their aspirations and their achievements.

A strength of this article is in the novel approach and its operationalization using primary data, but future research should seek to establish whether these relations hold for other pairs of countries using a larger sample of respondents that is generalizable to whole populations. Naturally, alternative potential explanations may lie behind our empirically illustrated associations. Future research could explore the standard cultural gravity model augmenting its home bias component with a correction for the Sour Grape effect on the dynamics of trade flows.

Our contribution provides empirical evidence, using the very language of hedonic valuation, that consumers’ preferences are strongly dependent on cultural shaping and exploit the social vulnerability of people. Specifically, we demonstrated that the intentional marketing use of art (such as, in the case of the marketing tool Hallyu, the use of Korean TV drama) could be and is de facto used to instigate conspicuous consumption and does so among the most vulnerable people who feel already socio-economically deprived. These findings reinforce both the claim of Hamilton (Citation1973) that institutional and evolutionary economics add to neoclassical economics, and demonstrates that a classical hedonic model will be underspecified if the cultural factor is not accounted for, as maintained by Tubadji (Citation2014) and elsewhere by the CBD paradigm.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annie Tubadji

Annie Tubadji is in the Economics Department at Swansea University. Ruxiang Wee is in the School of Economics at the University of the West of England. Don J. Webber is in the Sheffield University Management School at the University of Sheffield. The authors thank Simon Rudkin for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Ruxiang Wee

Annie Tubadji is in the Economics Department at Swansea University. Ruxiang Wee is in the School of Economics at the University of the West of England. Don J. Webber is in the Sheffield University Management School at the University of Sheffield. The authors thank Simon Rudkin for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Don J. Webber

Annie Tubadji is in the Economics Department at Swansea University. Ruxiang Wee is in the School of Economics at the University of the West of England. Don J. Webber is in the Sheffield University Management School at the University of Sheffield. The authors thank Simon Rudkin for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Notes

1 From an empirical standpoint, not including culture in an economic choice model will always lead to under-specification of the model due to omitted variable bias (Tubadji Citation2014).

2 Alternative definitions of culture with similar essence are available in Rose (Citation2018) or for earlier compatible evolutionary economics definitions by Ayres and Neale, see Tool (Citation1988).

3 Hallyu began with the release of “Winter Sonata” by the Korean Broadcasting System in 2002 (Han and Lee Citation2008) and expanded to include television drama, variety shows, Korean-pop music, movies, fashion, and trends promoted by Korean celebrities. Ng and Chan (Citation2019) also report an effect of Hallyu on tourism.

4 Meanwhile, the exchange rate between 2013 and 2021 has fluctuated up and down, but if anything it has fallen from 1:374 to 1:280 (Malaysia:South Korea) over the period 2013–2021. Despite this, our respondents kept self-reportedly perceiving South Korea as a more affluent place. In our interpretation, this is an anecdotal demonstration that social construction of value is not entirely driven by price and monetary factors.

5 The sample was collected following a digital form of snowball sampling. The first five respondents were contacted directly by the research team with the request to pass the link for the questionnaire to their friends, with a similar request for the friends. Thus, we accumulated a sample influenced by networks shaped by proximity and friendship, and therefore we expect some correlation in the error terms. However, we would not expect the responses to these questions to be particularly sensitive to the data generation process. Although the sample is not necessarily representative, the number of observations is sufficient for internal validity of the findings after controlling for pre-selection bias.

6 Economic psychology presents the anchoring effect, where setting first a high price and then moving to a lower price for a product can lead to very different consumer behavior than if a pricing strategy moves from a low to a high price (Sitzia and Zizzo Citation2012).

7 Another dimension of product characteristics, but this time entirely dependent on the subjective valuation function, is known as the “perceived price,” which is the assessment of worth of the product by consumers (Hellier et al. Citation2003). It does not reflect the price paid, cost, or ease of acquiring the product (Khare, Achtana, Khattar Citation2014) but does reflect what consumers consider a reasonable price given the quality of the product. Rao and Monroe (Citation1988) found that perceived price is one of the strongest indications of perceived product quality.

8 Hyman (Citation1942) defines the term “reference group” as “a person or a group of persons [who] significantly influences an individual’s behavior.” A reference group is the group that an individual aspires to belong to by mimicking the consumption behavior of the individuals in that group. While many would agree about the relevance of this term in its essence for the core of Veblen’s ideas regarding conspicuous consumption, this term has been insufficiently used to link Veblen’s idea of reference group to the neoclassical application and improvement that it implies (see Oh, Park, and Bowles Citation2012 for a rare exception).

9 There are important aspects of social factors and cultural relativity that bear a Bourdieu-Veblen nexus; we develop this in the Appendix as they are not the focus of our empirical test, which instead focuses on the main effect between two specific countries

10 Numerous examples for this tendency exist in the literature. For instance, unemployed individuals will focus on consuming entertainment activities not accessible for people whose time is employed at work (Gimenez-Nadal and Molina Citation2014). People’s preferences are known to adapt fast to new conditions and create depletion of the pleasure from a newly acquired status, good or service over the time of its possession—in a kind of amortization of pleasure called a “hedonic treadmill” (see Mochon, Norton, and Ariely Citation2008).

11 Relative deprivation operates between individuals and between groups (Zubielevitch, Sibley, and Osborne Citation2019).

12 See Birt and Dion (Citation1987) and Zoogah (Citation2010) for examples of studies into the theory of Relative Deprivation.

13 These pages were www.facebook.com/malaysiakpopfans/, www.facebook.com/GoKpopMalaysia/ and www.facebook.com/MyKpopHuntress/. Each page on these websites contain at least 10,000 likes, so these are not obscure minority Facebook groups and may accurately reflect Malaysian interest in Korean pop culture.

14 RM is the abbreviation for the currency Malaysian Ringgit.

15 This variable identifies the propensity to consume conspicuously, ConspCon, in the micro-economic mechanism in model (1.1).

16 In this specific case it represents relative deprivation on the labor market with regard to gender pay inequality.

17 Culturally shaped preferences evolve with exposure to new cultures albeit with grounding on the culture that was initially present, which is a phenomenon known as cultural path dependence (Zhang and Weng Citation2017).

18 An alternative definition, strongly consistent with this one but with evolutionary economics origins was suggested by Clarence Ayres: “Culture, the organized corpus of behavior of which economic activity is but a part, is a phenomenon sui generis. It is not an epiphenomenon, a result of something else, explicable in other and non-cultural terms, it is the stuff of social behavior, the universe of discourse of the social sciences, the aspect which the data of observation assume at that level of generalization.” See Tool (Citation1988) for more clarifications on the evolutionary interpretation of this definition.

19 Analyses of macro effects linked with cultural factors are more numerous and relate to attracting migration, FDI and trade flows. In these studies, the cultural effect is called ‘home bias’ (Tadesse and Shukralla Citation2013) and described as the power of cultural proximity between localities to influence economic choices. Cultural relativity gives rise to a cultural gravity mechanism (Tubadji and Nijkamp Citation2015) which is the phenomenon of mutual attraction between two entities due to the relatively small cultural difference between them.

20 A prominent and well-studied form of social influence is the peer effect—the effect exerted by the taste of the group one belongs to on the individual’s preference and behavior. Zhu et al. (Citation2016) show that peer-influence on social media platforms affects online purchasing behavior of consumers. Studies conducted in developed countries with an individualistic culture propose that social influence fundamentally affects the purchase of green products (Costa, Zepeda, and Sirieix Citation2014; Salazar, Oerlemans, and van Stroe-Biezen Citation2013). Similar results were found in studies on collectivist cultures and consumption behavior (Bagozzi et al. Citation2000).

21 The basic idea of cultural relativity is summarized in the need of people to accept certain set of culturally established definitions of what is good and bad according to a group in order to belong to it and share its identity.

22 From a cultural perspective, a primary mechanism driving consumption is homophily (Smith Citation1759; Ryan and Patrick Citation2001), which is a source of sympathy towards others shown through emulation.

References

- Abdu Gianie, Purwanto. 2013. “Analysis of Consumer Behavior Affecting Consumer Willingness to Buy in 7-Eleven Convenience Store.” Universal Journal of Management 1 (2): 69–75. 10.13189/ujm.2013.010205

- Abraham, Aby, and Sanjay Patro. 2014. “‘Country-of-Origin’ Effect and Consumer Decision-Making.” Management and Labour Studies 39 (3): 309–318. 10.1177/0258042X15572408

- Alesina, Alberto, and Paola Giuliano. 2015. “Culture and Institutions.” Journal of Economic Literature 53 (4): 898–944. 10.1257/jel.53.4.898

- Arshad, Mohd Nahar Mohd, and Gairuzazmi Mat Ghani. 2015. “Returns to Education and Wage Differentials in Malaysia.” Journal of Developing Areas 49 (5): 213–223. 10.1353/jda.2015.0072

- Arslan, F. Müge, and Oylum Korkut Altuna. 2010. “The Effect of Brand Extensions on Product Brand Image.” Journal of Product and Brand Management 19 (3): 170–180. 10.1108/10610421011046157

- Bagozzi, Richard P., Nancy Wong, Shuzo Abe, and Massimo Bergami. 2000. “Cultural and Situational Contingencies and the Theory of Reasoned Action: Application to Fast Food Restaurant Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 9 (2): 97–106. 10.1207/S15327663JCP0902_4

- Billet, Bret. 2007. Cultural Relativism in the Face of the West: The Plight of Women and Female Children. New York and London: Springer.

- Birt, Catherine M., and Kenneth L. Dion. 1987. “Relative Deprivation Theory and Responses to Discrimination in a Gay Male and Lesbian Sample.” British Journal of Social Psychology 26 (2): 139–145. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1987.tb00774.x

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. Distinction. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John Richardson, 241–258. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. “La Domination Masculine.” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 84: 2–31. 10.3917/arss.p1990.84n1.0002

- Chao, Paul. 1993. “Partitioning Country of Origin Effects: Consumer Evaluations of a Hybrid Product.” Journal of International Business Studies 24: 291–306. 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490851

- Chen, Jue, Antonio Lobo, and Natalia Rajendran. 2014. “Drivers of Organic Food Purchase Intentions in Mainland China–Evaluating Potential Customers’ Attitudes, Demographics and Segmentation.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (4): 346–356. 10.1111/ijcs.12095

- Chen-Yu, Jessie H., and Yoo-Kyoung Seock. 2002. “Adolescents’ Clothing Purchase Motivations, Information Sources, and Store Selection Criteria: A Comparison of Male/Female and Impulse/Nonimpulse Shoppers.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 31 (1): 50–77. 10.1177/1077727X02031001003

- Chi, Hsin Kuang, Huery Ren Yeh, and Ming Wei Huang. 2009. “The Influences of Advertising Endorser, Brand Image, Brand Equity, Price Promotion on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Effect of Advertising Endorser.” The Journal of Global Business Management 5 (1): 224–233.

- Costa, Sandrine, Lydia Zepeda, and Lucie Sirieix. 2014. “Exploring the Social Value of organic Food: A Qualitative Study in France.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (3): 228–237. 10.1111/ijcs.12100

- Dator, Jim, and Seo Yongseok. 2004. “Korea as the Wave of a Future: The Emerging Dream Society of Icons and Aesthetic Experience.” In Korea: The Past and the Present, edited by Susan Pares and Jim Hoare. Leiden: Brill.

- De Groot, Olaf J. 2011. “Spillovers of Institutional Change in Africa.” Kyklos 64 (3): 410–426. 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2011.00513.x

- Denzau, Arthur T., and Douglass C. North. 1994. “Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions.” Kyklos 47: 3–31. 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1994.tb02246.x

- Dinnie, Keith. 2004. “Country-of-Origin 1965–2004: A Literature Review.” Journal of Customer Behaviour 3 (2): 165–213. 10.1362/1475392041829537

- Duncan, James S., and Nancy G. Duncan. 2004. “Culture Unbound.” Environment and Planning A 36 (3): 391–403. 10.1068/a3654

- Dursun, Inci, Ebru Tümer Kabadayı, Alev Koçan Alan, and Bülent Sezen. 2011. “Store Brand Purchase Intention: Effects of Risk, Quality, Familiarity and Store Brand Shelf Space.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 24: 1190–1200. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.133

- Edwards, José M., and Sophie Pellé. 2011. “Capabilities for the Miserable; Happiness for the Satisfied.” Journal of the History of Economic Thought 33 (3): 335–355. 10.1017/S1053837211000216

- Erciş, Aysel, Sevtap Ünal, F. Burcu Candan, and Hatice Yıldırım. 2012. “The Effect of Brand Satisfaction, Trust and Brand Commitment on Loyalty and Repurchase Intentions.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 1395–1404. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1124

- Fernández, Raquel. 2011. “Does Culture Matter?” Handbook of Social Economics 1: 481–510.

- Fernandez, Karen V., and John L. Lastovicka. 2011. “Making Magic: Fetishes in Contemporary Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 38 (2): 278–299. 10.1086/659079

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1958. The Affluent Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1967. The New Industrial State. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1992. The Culture of Contentment. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Gilbert, Daniel T., Elizabeth C. Pinel, Timothy D. Wilson, Stephen J. Blumberg, and Thalia P. Wheatley. 1998. “Immune Neglect: A Source of Durability Bias in Affective Forecasting.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 (3): 617. 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.617

- Gimenez-Nadal, J. Ignacio, and Jose Alberto Molina. 2014. “Regional Unemployment, Gender, and Time Allocation of the Unemployed.” Review of Economics of the Household 12: 105–127 10.1007/s11150-013-9186-9

- Gogoi, Bidyut Jyoti. 2013. “Study of Antecedents of Purchase Intention and its Effect on Brand Loyalty of Private Label Brand of Apparel.” International Journal of Sales and Marketing 3 (2): 73–86.

- Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2006. “Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20 (2): 23–48. 10.1257/jep.20.2.23

- Hamilton, David. 1973. “What has Evolutionary Economics to Contribute to Consumption Theory?” Journal of Economic Issues 7 (2): 197–207. 10.1080/00213624.1973.11503104

- Hamilton, David. 1989. “Thorstein Veblen as the First Professor of Marketing Science.” Journal of Economic Issues 23 (4): 1097–1103. 10.1080/00213624.1989.11504976

- Han, Hee-Joo, and Jae-Sub Lee. 2008. “A Study on the KBS TV Drama Winter Sonata and its Impact on Korea’s Hallyu Tourism Development.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 24 (2–3): 115–126. 10.1080/10548400802092593

- Hauser, Christoph, Gottfried Tappeiner, and Janette Walde. 2015. “The Roots of Regional Trust.” No. 2015–13. Working Papers in Economics and Statistics.

- Hellier, Phillip K., Gus M. Geursen, Rodney A. Carr, and John A. Rickard. 2003. “Customer Repurchase Intention: A General Structural Equation Model.” European Journal of Marketing 37 (11/12): 1762–1800. 10.1108/03090560310495456

- Huat, Chua Beng. 2008. “East Asian Pop Culture: Layers of Communities.” In Media Consumption and Everyday Life in Asia, edited by Youna Kim, 111–125. New York and London: Routledge.

- Hyman, Herbert. 1942. “The Psychology of Subjective Status.” Psychological Bulletin 39: 473–474.

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. “The Cultural Relativity of the Quality of Life Concept.” Academy of Management Review 9 (3): 389–398. 10.2307/258280

- Hofstede, Geert. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

- International Trade Administration. 2016. “Asia Personal Care and Cosmetics Market Guide 2016.” Trade.gov. Available at www.trade.gov/industry/materials/AsiaCosmeticsMarketGuide.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- Irshad, Walter. 2012. “Service Based Brand Equity, Measure of Purchase Intention, Mediating Role of Brand Performance.” Academy of Contemporary Research Journal 1 (1): 1–10.

- Jennings, Ann and William Waller. 1995. “Culture: Core Concept Reaffirmed.” Journal of Economic Issues 29 (2): 407–418. 10.1080/00213624.1995.11505677

- Kay, Aaron C., Maria C. Jimenez, and John T. Jost. 2002. “Sour Grapes, Sweet Lemons, and the Anticipatory Rationalization of the Status Quo.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28 (9): 1300–1312. 10.1177/01461672022812014

- Khare, Arpita, Dhiren Achtani, and Manish Khattar. 2014. “Influence of Price Perception and Shopping Motives on Indian Consumers’ Attitude Towards Retailer Promotions in Malls.” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 26 (2): 272–295. 10.1108/APJML-09-2013-0097

- Lancaster, Kelvin J. 1966. “A New Approach to Consumer Theory.” Journal of Political Economy 74 (2): 132–157. 10.1086/259131

- Laroche, Michel, Nicolas Papadopoulos, Louise A. Heslop, and Mehdi Mourali. 2005. “The Influence of Country Image Structure on Consumer Evaluations of Foreign Products.” International Marketing Review 22 (1): 96–115. 10.1108/02651330510581190

- Lash, Scott. 1990. Sociology of Postmodernism. Psychology Press. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Lee Ross. 1999. “Changes in Attractiveness of Elected, Rejected, and Precluded Alternatives: A Comparison of Happy and Unhappy Individuals.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (6): 988. 10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.988

- Madsen, Jesper Majbom. 2017. “Looking in from the Outside: Strabo’s Attitude Towards the Roman People.” In The Routledge Companion to Strabo. London and New York: Routledge.

- Malaysia Cosmetics Observatory. 2021. CosmeticObs. Available at https://cosmeticobs.com/en/articles/congresses-48/cosmetics-market-and-trends-in-south-korea-4028.

- Mankiw, Gregory N. 2011. “Principles of Economics.” Mason, OH: South-Western CENGAGE Learning.

- Manzini, Paola, and Marco Mariotti. 2016. “Competing for Attention: Is the Showiest also the Best?” The Economic Journal 128 (609): 827–844. 10.1111/ecoj.12425

- Martin, Ingrid M., and Sevgin Eroglu. 1993. “Measuring a Multi-Dimensional Construct: Country Image.” Journal of Business Research 28 (3): 191–210. 10.1016/0148-2963(93)90047-S

- Mayhew, Anne. “Culture: Core Concept Under Attack.” Journal of Economic Issues 21 (2): 586–603. 10.1080/00213624.1987.11504652

- McDowell, Linda M. 1997. “The New Service Class: Housing, Consumption, and Lifestyle among London Bankers in the 1990s.” Environment and Planning A 29 (11): 2061–2078. 10.1068/a292061

- McFadden, Daniel L. 1997. “Measuring Willingness-to-Pay for Transportation Improvements.” Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley.

- Menon, Alka V. 2019. “Cultural Gatekeeping in Cosmetic Surgery: Transnational Beauty Ideals in Multicultural Malaysia.” Poetics 75: 101354. 10.1016/j.poetic.2019.02.005

- Mintel. 2017. “A Bright Future: South Korea Ranks among the Top 10 Beauty Markets Globally.” Available at http://www.mintel.com/press-centre/beauty-and-personal-care/a-bright-future-south-korea-ranks-among-the-top-10-beauty-markets-globally. Accessed on November 5, 2018.

- Mochon, Daniel, Michael I. Norton, and Dan Ariely. 2008. “Getting off the Hedonic Treadmill, One Step at a Time: The Impact of Regular Religious Practice and Exercise on Well-Being.” Journal of Economic Psychology 29 (5): 632–642. 10.1016/j.joep.2007.10.004

- Moon, Sangkil, Barry L. Bayus, Youjae Yi, and Junhee Kim. 2015. “Local Consumers’ Reception of Imported and Domestic Movies in the Korean Movie Market.” Journal of Cultural Economics 39: 99–121. 10.1007/s10824-013-9214-x

- Ng, Tuen-Man, and Chung-Shing Chan. 2019. “Investigating Film-Induced Tourism Potential: The Influence of Korean TV Dramas on Hong Kong Young Adults.” Asian Geographer 37 (1): 53–73. 10.1080/10225706.2019.1701506

- Oh, Seung-Yun, Yongjin Park, and Samuel Bowles. 2012. “Veblen Effects, Political Representation, and the Reduction in Working Time over the 20th century.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 83 (2): 218–242. 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.05.006

- Orford, Scott. 2000. “Modelling Spatial Structures in Local Housing Market Dynamics: A Multilevel Perspective.” Urban Studies 37 (9): 1643–1671. 10.1080/00420980020080301

- Palmquist, Raymond B. 1984. “Estimating the Demand for the Characteristics of Housing.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 66 (3): 394–404. 10.2307/1924995

- Parkvithee, Narissara, and Mario J. Miranda. 2012. “The Interaction Effect of Country-of-Origin, Brand Equity and Purchase Involvement on Consumer Purchase Intentions of Clothing Labels.” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 24 (1): 7–22. 10.1108/13555851211192678

- Pratt, Andy. 1997. “Guest Editorial.” Environment and Planning A 29 (11): 1911–1917. 10.1068/a291911

- Rao, Akshay R., and Kent B. Monroe. 1988. “The Moderating Effect of Prior Knowledge on Cue Utilization in Product Evaluations.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2): 253–264. 10.1086/209162

- Rose, David C. 2018. “Why Culture Matters Most.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ryan, Allison M., and Helen Patrick. 2001. “The Classroom Social Environment and Changes in Adolescents’ Motivation and Engagement During Middle School.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (2): 437–460. 10.3102/00028312038002437

- Sahlins, Marshall, and Elman R. Service. 1960. “Evolution and Culture.” Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Salazar, Helen Arce, Leon Oerlemans, and Saskia van Stroe-Biezen. 2013. “Social Influence on Sustainable Consumption: Evidence from a Behavioural Experiment.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 37 (2): 172–180. 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2012.01110.x

- Schooler, Robert D. 1965. “Product Bias in the Central American Common Market.” Journal of Marketing Research 2 (4): 394–397. 10.1177/002224376500200407

- Scitovsky, Tibor. 1976. “The Joyless Economy: An Inquiry into Human Satisfaction and Consumer Dissatisfaction.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Segers, Fred. 2000. “Korea Moves.” Hollywood Reporter 362 (34): 14–16.

- Sen, Amartya. 1979. “Equality of What?” The Tanner Lecture on Human Values delivered at Stanford University.

- Sen, Amartya. 1983. “Poor, Relatively Speaking.” Oxford Economic Papers 35: 153–69. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041587

- Sen, Amartya. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Seton, Francis. 1957. “The Transformation Problem.” Review of Economic Studies 24 (3): 149–160. 10.2307/2296064

- Sitzia, Stefania, and Daniel John Zizzo. 2012. “Price Lower and Then Higher or Price Higher and Then Lower?” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (6): 1084–1099. 10.1016/j.joep.2012.07.006

- Smith , Adam . 1759. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Printed for A. Millar, and A. Kincaid and J. Bell.

- Snowball, Janet. 2008. Measuring the Value of Culture: Methods and Examples in Cultural Economics. Berlin: Springer.

- Souiden, Nizar, Frank Pons, and Marie-Eve Mayrand. 2011. “Marketing High-Tech Products in Emerging Markets: The Differential Impacts of Country Image and Country-of-Origin’s Image.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 20 (5): 356–367. 10.1108/10610421111157883

- Tadesse, Bedassa, and Elias K. Shukralla. 2013. “The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Horizontal Export Diversification: Empirical Evidence.” Applied Economics 45 (2): 141–159. 10.1080/00036846.2011.595692

- Tariq, Muhammad Irfan, Muhammad Rafay Nawaz, Muhammad Musarrat Nawaz, and Hashim Awais Butt. 2013. “Customer Perceptions about Branding and Purchase Intention: A Study of FMCG in an Emerging Market.” Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research 3 (2): 340–347.

- Taylor, Shelley E., and Jonathon D. Brown. 1988. “Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (2): 193. 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193

- Teimouri, Hadi, Nazila Fanae, Kouroush Jenab, Sam Khoury, and Saeid Moslehpour. 2016. “Studying the Relationship Between Brand Personality and Customer Loyalty: A Case Study of Samsung Mobile Phone.” International Journal of Business and Management 11 (2): 1. 10.5539/ijbm.v11n2p1

- Thanasuta, Kandapa, Thanyawee Patoomsuwan, Vanvisa Chaimahawong, and Yingyot Chiaravutthi. 2009. “Brand and Country of Origin Valuations of Automobiles.” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 21 (3):355–375. 10.1108/13555850910973847

- Thøgersen, John, and Yanfeng Zhou. 2012. “Chinese Consumers’ Adoption of a ‘Green’ Innovation–The Case of Organic Food.” Journal of Marketing Management 28 (3–4): 313–333. 10.1080/0267257X.2012.658834

- Throsby, C. David. 1984. “The Measurement of Willingness-to-Pay for Mixed Goods.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 46 (4): 279–289. 10.1111/j.1468-0084.1984.mp46004001.x

- Tih, Siohong, and Heng Lee Kean. 2013. “Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence from Malaysia.” Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6 (2): 107–138.

- Tonglet, Michele, Paul S. Phillips, and Adam D. Read. 2004. “Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate the Determinants of Recycling Behaviour: A Case Study from Brixworth, UK.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 41 (3): 191–214. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2003.11.001

- Tool, Marc. 1988. Evolutionary Economics: Foundations of Institutional Thought. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge.

- Tool, Marc. 1990. “Culture Versus Social Value? A Response to Anne Mayhew.” Journal of Economic Issues 24 (4): 1122–1133. 10.1080/00213624.1990.11505106

- Trigg, Andrew B. 2001. “Veblen, Bourdieu, and Conspicuous Consumption.” Journal of Economic Issues 35 (1): 99–115. 10.1080/00213624.2001.11506342

- Tubadji, Annie. 2012. “Culture-Based Development: Empirical Evidence for Germany.” International Journal of Social Economics 39 (9): 690–703. 10.1108/03068291211245718

- Tubadji, Annie. 2013. “Culture-Based Development: Culture And Institutions—Economic Development in the Regions of Europe.” International Journal of Society Systems Science 5 (4): 355–391. 10.1504/IJSSS.2013.058466

- Tubadji, Annie. 2014. “Was Weber Right? The Cultural Capital Root of Socio-Economic Growth Examined in five European Countries.” International Journal of Manpower 35 (1/2): 56–88. 10.1108/IJM-08-2013-0194

- Tubadji, Annie and Peter Nijkamp. 2015. “Cultural Gravity Effects among Migrants: A Comparative Analysis of the EU15.” Economic Geography 91 (3): 343–380. 10.1111/ecge.12088

- Tubadji, Annie, and Steve Pratt. 2019. “CBD Approach to Magical Thinking and Tourist Preferences in Hong Kong.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Tubadji, Annie, Masood Gheasi, Alessandro Crociata and Iacopo Odoardi. 2022. “Cultural Capital and Income Inequality across Italian Regions.” Regional Studies 56 (3): 459–475. 10.1080/00343404.2021.1950913

- Turner, John C. 1991. Social Influence. Pacific Grove, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

- Veblen, Thorstein. 1915. Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution. New York: The University of Michigan Press.

- Veblen, Thorstein. 1899. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Waller, William. 2003. “It’s Culture All the Way Down.” Journal of Economic Issues 37 (1): 35–45. 10.1080/00213624.2003.11506552

- Wilkinson, Nick and Matthias Klaes. 2012. “An Introduction to Behavioural Economics.” Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zhang, Rui, and Liping Weng. 2017. “Not All Cultural Values are Created Equal: Cultural Change in China Reexamined Through Google Books.” International Journal of Psychology 54 (1): 144–154. 10.1002/ijop.12436

- Zhu, Zhiguo, Jianwei Wang, Xiening Wang, and Xiaoji Wan. 2016. “Exploring Factors of User’s Peer–Influence Behavior in Social Media on Purchase Intention: Evidence from QQ.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 980–987. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.037

- Zoogah, David B. 2010. “Why Should I be Left Behind? Employees’ Perceived Relative Deprivation and Participation in Development Activities.” Journal of Applied Psychology 95 (1): 159. 10.1037/a0018019

- Zubielevitch, Elena, Chris G. Sibley, and Danny Osborne. 2019. “Chicken or the Egg? A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis of Group Identification and Group-Based Relative Deprivation.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 23 (7): 1032–1048. 10.1177/1368430219878782

Appendix:

Main Variables and Definitions

Appendix:

Cultural Variation of Social Factors

Adam Smith (Citation1759) notes the importance of cultural proximity for evoking mutual sympathy. An individual’s knowledge, experience and exposure to context-, location-, and culturally-specific inclinations nurture this cultural effect (Abraham and Patro Citation2014) and underpins Geert Hofstede’s (Citation1991, 5) definition of culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another”.Footnote17,Footnote18

Tibor Scitovsky (Citation1976) emphasizes the vast income differences that exist across societies and how group culture affects economic choices. In affluent societies consumption is driven not by basic subsistence needs (as it is the case in poor societies) but by the need for entertainment to alleviate boredom (Galbraith Citation1958 and Citation1967). Scitovsky’s distinction was refined by Jose Edwards and Sophie Pelle (Citation2011) to incorporate Sen’s capabilities approach (Sen Citation1979, Citation1983, and Citation1992) and the economics of happiness. Utility functions of poor and rich consumers are sufficiently distinct due to their different abilities to access socio-economic alternatives and hence an individual’s relative socio-economic status affects their perception of value.

A product’s country of origin is a factor affecting its consumption.Footnote19 This cultural-relativity approach, is one of the most developed streams of literature in international marketing (Schooler Citation1965; Dinnie Citation2004; Laroche et al. Citation2005). Country of origin influences consumers’ assessments of product quality, their purchase intention (Parkvithee and Miranda Citation2012), and their willingness to pay for it (Thanasuta et al. Citation2009). Ingrid Martin and Sevgin Eroglu (Citation1993) proposed that consumers’ knowledge of a product’s country of origin serves as a psychological shortcut when they do not have other product information, with this country image effect being a source of cultural bias affecting individual choice. A country image effect is the impression created out of beliefs shaped by knowledge of that country. Although these beliefs are descriptive, inferential, and informational in affecting consumers’ subjective utilities, empirical evidence confirms the decisive importance of the country image effect. For instance, evidence suggests a disconnection between the actual quality and the perceived subjective valuation of products produced by less developed countries (Chao Citation1993).

Using his original terminology, Veblen describes the same by acknowledging the matter of conspicuous consumption as a subject of space and time dependent “branches of knowledge” (Veblen Citation1899 and Citation1915; Trigg Citation2001), such as speaking a dead language, occult sciences, or correct spellings, to name a few of Veblen’s original examples. Country of origin effects influence a product’s image and a positive country image increases consumers’ willingness to buy that country’s products (Souiden, Pons, and Mayrand Citation2011). Some claim that consumer choice is more culturally motivated than it is brand motivated (Teimouri et al. Citation2016).

Attitudes have a crucial role in moderating the specificity and strength of purchase intentions (Tonglet, Phillips, and Read Citation2004), which in turn determine the probability of purchase. Attitudes towards cultural goods are a subject of social construction and inherited through local cultural capital and traditions (Bourdieu Citation1986 and Citation1990). Cultural moderations of the social factor operate by evoking change in individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviours in response to their society and surroundings (Turner Citation1991), and people control their own thoughts and actions in order to conform to groups or society (Chen-Yu and Seock Citation2002) in order to gain social belonging to a particular reference group (Veblen Citation1899).Footnote20