Abstract

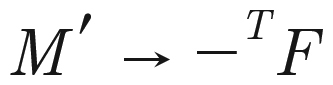

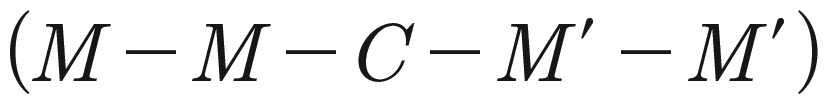

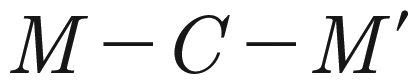

This article refines the analysis of interest-bearing capital and debt in Marx’s circuit of capital, incorporating Kōzō Uno’s critique for a more precise depiction. It reassesses Marx’s model of interest-bearing capital ( ) and Uno’s distinction between creditor and debtor roles, proposing an advanced model that highlights the role of financial instruments (

) and Uno’s distinction between creditor and debtor roles, proposing an advanced model that highlights the role of financial instruments ( ) and debt (

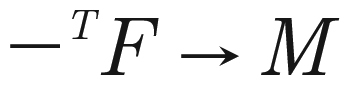

) and debt ( ). The form of money-lending capital for the creditor is articulated as

). The form of money-lending capital for the creditor is articulated as  , where

, where  represents the issuance of a loan and

represents the issuance of a loan and  the collection of debt. On the other hand, the form of merchant capital with debt for the debtor is depicted as

the collection of debt. On the other hand, the form of merchant capital with debt for the debtor is depicted as  , incorporating both the borrowing (

, incorporating both the borrowing ( ) and repayment (

) and repayment ( ) processes within the form of merchant capital. This approach not only clarifies the transactions between creditors and debtors but also builds upon Uno’s theoretical contributions, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of interest-bearing capital and the movement of capital with debt. The revision aims to elucidate the processes of loan issuance, debt collection, borrowing, and repayment, rectifying previous conceptual oversights and offering a solid foundation for future economic research.

) processes within the form of merchant capital. This approach not only clarifies the transactions between creditors and debtors but also builds upon Uno’s theoretical contributions, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of interest-bearing capital and the movement of capital with debt. The revision aims to elucidate the processes of loan issuance, debt collection, borrowing, and repayment, rectifying previous conceptual oversights and offering a solid foundation for future economic research.

In Marxian economics, the circuit of capital model, as proposed by Karl Marx, adeptly delineates the cyclical dynamics of money, commodity, and productive capital within a capitalist economy. While effective in analyzing these elements, its application to the domain of interest-bearing capital, a key aspect of modern finance, necessitates further development. This article aims to extend the circuit of capital model to better encompass the complexities of interest-bearing capital and debt.

This endeavor is inspired by Kōzō Uno’s critique, which highlighted the model’s limited scope in addressing the nuances of interest-bearing capital, a concept further divided by Uno into money-lending and merchant capital.Footnote1 Motivated by Uno’s insights, this study aims to deepen the analysis within the circuit of capital, focusing on the emergence, circulation, and eventual dissolution of debt within the capitalist economy.

The article is structured to progressively build upon this expanded theoretical foundation. Initially, it revisits Marx’s concept of interest-bearing capital and critically examines Uno’s critique. The subsequent section refines Uno’s formulations to better represent financial transactions, particularly those involving financial instruments like IOUs. The next section introduces a comprehensive formulation of capital, acknowledging debt as a crucial element in the capitalist circuit. This section delves into the dynamics of borrowing and repayment and their implications for both debtors and creditors. Ultimately, this study endeavors to enhance Marx’s circuit of capital by addressing its limitations and widening its scope to reflect the intricacies of interest-bearing capital and debt more accurately in contemporary economics.

Formulation of Interest-Bearing Capital by Marx and Uno

The circuit of capital is pivotal in Marxian economics for clarifying how capital continuously transforms within the economy, assuming different roles in the production and circulation processes. Within this framework, interest-bearing capital is a critical form that embodies the financial relationships and transactions foundational to capitalist systems. Marx’s representation of interest-bearing capital is encapsulated in the formula  , where

, where  signifies money,

signifies money,  a commodity, and the prime (

a commodity, and the prime (![]() ) an increase in quantity.

) an increase in quantity.

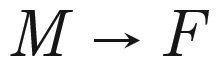

The formula’s initial phase,  , delineates the motion of lending and borrowing money. It begins with a lender who holds an amount of money (the first

, delineates the motion of lending and borrowing money. It begins with a lender who holds an amount of money (the first  ), which is then provided to a borrower, leading to the second

), which is then provided to a borrower, leading to the second  in the sequence. This step lays the groundwork for subsequent economic activities, representing the essential transaction of money lending.

in the sequence. This step lays the groundwork for subsequent economic activities, representing the essential transaction of money lending.

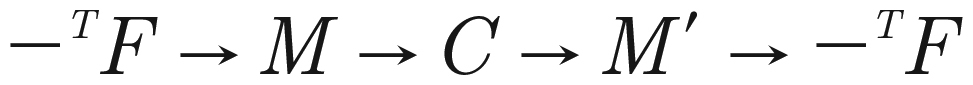

Following this, the second phase  illustrates the operations of merchant capital. Here, the borrower utilizes the borrowed money

illustrates the operations of merchant capital. Here, the borrower utilizes the borrowed money  to purchase commodities

to purchase commodities  . These commodities are then sold, ideally at a markup, resulting in a larger sum of money

. These commodities are then sold, ideally at a markup, resulting in a larger sum of money  . This part of the sequence captures the capitalist act of buying low and selling high, a fundamental process for capital accumulation in market economies.

. This part of the sequence captures the capitalist act of buying low and selling high, a fundamental process for capital accumulation in market economies.

The final phase,  , highlights the completion of the cycle with the borrower repaying the debt, including the accrued profit. The lender receives the original sum plus interest, thus the “interest-bearing” quality of the capital is realized. Marx’s formulation may serve as a conceptual framework, capturing the intricate economic transactions underpinning capitalist economies. However, this formulation, while insightful, has been critiqued for certain oversights, leading to the need for further refinement.

, highlights the completion of the cycle with the borrower repaying the debt, including the accrued profit. The lender receives the original sum plus interest, thus the “interest-bearing” quality of the capital is realized. Marx’s formulation may serve as a conceptual framework, capturing the intricate economic transactions underpinning capitalist economies. However, this formulation, while insightful, has been critiqued for certain oversights, leading to the need for further refinement.

Uno’s critique of Marx’s formula addresses these concerns by arguing that Marx’s portrayal conflates distinct economic transactions, namely the physical transfer of money and the exchange of commodities. Uno contends that the hyphens in Marx’s formulae  should not be interpreted uniformly. Instead, the hyphens between

should not be interpreted uniformly. Instead, the hyphens between  should read as “is transferred to,” highlighting the movement of money between separate entities, such as a creditor and a debtor. In contrast, the hyphen in

should read as “is transferred to,” highlighting the movement of money between separate entities, such as a creditor and a debtor. In contrast, the hyphen in  should be read as “is exchanged for,” indicating commodity trading. In this view, the sequence represents the transformation of capital from one form to another within a single economic agent’s domain—from money to commodity, and back to a greater sum of money.

should be read as “is exchanged for,” indicating commodity trading. In this view, the sequence represents the transformation of capital from one form to another within a single economic agent’s domain—from money to commodity, and back to a greater sum of money.

To rectify the potential confusion, Uno visualized his critique as with introducing new notations.Footnote2

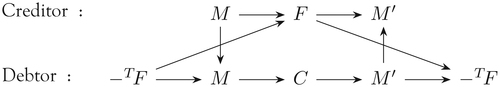

Figure 1. Uno’s Formulation of the Interest-Bearing Capital

Source: Author’s adaptation of Uno (Citation[1954] 1974, 190)

![Figure 1. Uno’s Formulation of the Interest-Bearing CapitalSource: Author’s adaptation of Uno (Citation[1954] 1974, 190)](/cms/asset/7f66b289-e960-40e2-b9fc-8206294e9de3/mjei_a_2344451_f0001_b.jpg)

A dotted line (![]() ) signifies capital movements outside the circulation process, and arrows depict transfers: a downward arrow (

) signifies capital movements outside the circulation process, and arrows depict transfers: a downward arrow (![]() ) for lending and an upward arrow (

) for lending and an upward arrow (![]() ) for repayment. This visualization emphasizes the distinct processes of lending and repayment, as opposed to the exchange of commodities, thus offering a clearer understanding of the nuanced financial transactions that constitute the capitalist economic landscape. Uno’s critique brings clarity to the distinct transactions of money-lending capital and merchant capital in Marx’s formula, delineating the roles of different economic agents. However, it does not fully articulate the mechanisms of credit and debt. We will extend Uno’s groundwork, offering a more detailed portrayal of the financial intricacies within the capital circuit.

) for repayment. This visualization emphasizes the distinct processes of lending and repayment, as opposed to the exchange of commodities, thus offering a clearer understanding of the nuanced financial transactions that constitute the capitalist economic landscape. Uno’s critique brings clarity to the distinct transactions of money-lending capital and merchant capital in Marx’s formula, delineating the roles of different economic agents. However, it does not fully articulate the mechanisms of credit and debt. We will extend Uno’s groundwork, offering a more detailed portrayal of the financial intricacies within the capital circuit.

Redefining Money-Lending Capital: A Critique and Beyond of Uno’s Formulation

Uno’s Money-Lending Capital Formula: Unpacking the Ownership Paradox

Uno’s interpretation of the loan process in Marxian economics, represented as  , introduces a critical perspective but overlooks how the creditor acquires a financial claim in return for the loaned money. We advocate for a redefinition of Uno’s money-lending capital formula to encapsulate the realities of loan transactions and the subsequent debt collection more accurately.

, introduces a critical perspective but overlooks how the creditor acquires a financial claim in return for the loaned money. We advocate for a redefinition of Uno’s money-lending capital formula to encapsulate the realities of loan transactions and the subsequent debt collection more accurately.

In both Marx and Uno’s formulations, there appears to be a misapprehension regarding the merchant’s capital ownership, symbolized as  in the

in the  sequence. Marx presents the

sequence. Marx presents the  process as the sale of a commodity, which in this context is the right to use money, where the interest paid by the borrower reflects the usage price. This notion, however, presents an inherent conflict concerning who truly owns the initial money. Marx’s position that the lender retains ownership despite the borrower’s usage rights leads to a paradox when the money changes hands in the market, seemingly transferring ownership away from the lender.

process as the sale of a commodity, which in this context is the right to use money, where the interest paid by the borrower reflects the usage price. This notion, however, presents an inherent conflict concerning who truly owns the initial money. Marx’s position that the lender retains ownership despite the borrower’s usage rights leads to a paradox when the money changes hands in the market, seemingly transferring ownership away from the lender.

To resolve this issue, the ownership of the initial money  should be ascribed to the debtor upon the loan’s execution, deviating from the implication in

should be ascribed to the debtor upon the loan’s execution, deviating from the implication in  that it remains with the creditor. For example, when a lender provides a 100-pound loan, Marx’s logic would still consider the lender as the capital owner, even though the borrower utilizes it in transactions. Yet, this contradicts the lender’s capital valuation, which should not be nullified between the lending and repayment.

that it remains with the creditor. For example, when a lender provides a 100-pound loan, Marx’s logic would still consider the lender as the capital owner, even though the borrower utilizes it in transactions. Yet, this contradicts the lender’s capital valuation, which should not be nullified between the lending and repayment.

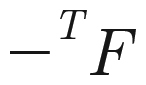

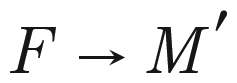

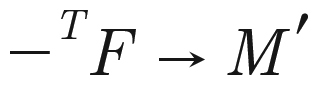

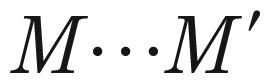

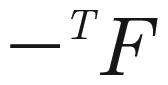

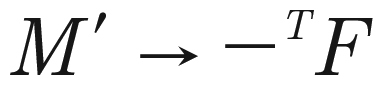

We propose a revised formula:  , where

, where  stands for a financial instrument reflecting the lender’s claim to the money plus interest.Footnote3 After lending, the lender holds an instrument equivalent to the loan value, thereby maintaining their capital’s worth until repayment. In this formulation, after the lender provides the 100-pound loan, they receive a financial instrument

stands for a financial instrument reflecting the lender’s claim to the money plus interest.Footnote3 After lending, the lender holds an instrument equivalent to the loan value, thereby maintaining their capital’s worth until repayment. In this formulation, after the lender provides the 100-pound loan, they receive a financial instrument  —such as a bond, bill, or insurance note—equivalent to the loan amount. And then the lender collects the 100 pounds and the interest 15 pounds as

—such as a bond, bill, or insurance note—equivalent to the loan amount. And then the lender collects the 100 pounds and the interest 15 pounds as  . We delve deeper into the implications and nuances of this revised formula.

. We delve deeper into the implications and nuances of this revised formula.

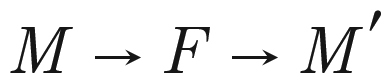

From  to

to  : Rethinking Uno’s Interpretation of Money-Lending Capital

: Rethinking Uno’s Interpretation of Money-Lending Capital

The two-fold operation of the loan process is best captured by the new formulation  , which reflects the lending and debt collection phases, respectively. It is imperative to note that this process is fundamentally different from the Marx-Uno interpretation of

, which reflects the lending and debt collection phases, respectively. It is imperative to note that this process is fundamentally different from the Marx-Uno interpretation of  .

.

Initially, the  transaction is conceptualized not as a straightforward loan, but as the creditor acquiring a financial claim (

transaction is conceptualized not as a straightforward loan, but as the creditor acquiring a financial claim ( ), akin to purchasing a commodity. This claim could take various forms, such as bonds or bills, and represents the creditor’s right to future repayment with interest. This approach diverges significantly from the conventional Marx-Uno model, where the loan process was simplified as a direct money transfer. Instead, it recognizes the creditor’s acquisition of financial instruments as an integral part of the capital circuit, underscoring the transformation of money capital into a financial claim.

), akin to purchasing a commodity. This claim could take various forms, such as bonds or bills, and represents the creditor’s right to future repayment with interest. This approach diverges significantly from the conventional Marx-Uno model, where the loan process was simplified as a direct money transfer. Instead, it recognizes the creditor’s acquisition of financial instruments as an integral part of the capital circuit, underscoring the transformation of money capital into a financial claim.

The repayment phase,  , is reinterpreted as a consumption process rather than a mere transaction. Here, the creditor “consumes” the formal use-value of the financial instrument by claiming the repayment. This perspective aligns with Marx’s view of money’s dual use-value—its formal role in transactions and its material form. The financial instrument’s use-value is realized when the debtor fulfills their obligation, thus completing the capital circuit. This phase differs from traditional sale processes, as it involves the unilateral fulfillment of a contract by the debtor, marking a distinct departure from the bilateral nature of commodity exchanges.

, is reinterpreted as a consumption process rather than a mere transaction. Here, the creditor “consumes” the formal use-value of the financial instrument by claiming the repayment. This perspective aligns with Marx’s view of money’s dual use-value—its formal role in transactions and its material form. The financial instrument’s use-value is realized when the debtor fulfills their obligation, thus completing the capital circuit. This phase differs from traditional sale processes, as it involves the unilateral fulfillment of a contract by the debtor, marking a distinct departure from the bilateral nature of commodity exchanges.

By redefining the money-lending capital model, this article not only challenges the established Marx-Uno interpretation but also deepens the understanding of the creditor-debtor dynamics. It highlights the often-neglected debtor’s perspective in Marxian economics, providing a more holistic view of the capital circuit. This reformulation illuminates the intricate processes of interest-bearing capital and sets a foundation for further exploration and discussion within Marxian economic theory.

Tracing the Motion of Debt: A Comprehensive Examination of Debt Creation, Circulation, and Elimination

Tully System as a Key to Understand Debt

The development of the money-lending capital formula ( ) leads to an important inquiry: the origin of

) leads to an important inquiry: the origin of  , representing financial instruments. While the debtor’s operations, captured by

, representing financial instruments. While the debtor’s operations, captured by  , show no direct indication of these instruments, a deeper exploration is required to understand their role in capitalist economies.

, show no direct indication of these instruments, a deeper exploration is required to understand their role in capitalist economies.

A historical excursion to medieval England’s tally system provides crucial insights into debt’s creation, circulation, and elimination.Footnote4 This system used a carved wooden stick (“tally”) to record debts, demonstrating the tangible manifestation of financial obligations and repayments.

In this system, the creation of debt involved a tally stick, notched to symbolize the borrowed amount. Upon initiating a loan, typically with the English exchequer as the borrower, a tally stick was crafted, its notches symbolizing the borrowed amount. This served as a physical, mutual record of the debt for both parties. The stick was then split into two halves: the “stock” for the lender and the “foil” for the debtor. In this arrangement, the stock signified the creditor’s claim, while the foil served as a reminder to the debtor of their repayment obligation.

The circulation of debt was evident through the distribution of the tally halves. The stock indicated the sum owed, while the foil represented the repayment duty. This division crystallized the creditor-debtor relationship, visually encapsulating the contractual obligations.

Debt elimination occurred upon full repayment, marked by the unification and annulment of both tally halves. This action symbolized the conclusion of the debt, eradicating all records and obligations related to it.

The tally system’s examination offers profound insights into debt’s lifecycle, from creation to elimination. This historical perspective enriches our understanding of financial instruments in current capitalist frameworks, providing a foundation for further exploration of their creation and function within a Marxian economic context.

Debt Transformation in Marxian Economics: A Numerical Approach to the General Formula

To comprehend the creation, circulation, and elimination of debt in a capitalist economy, we turn to a numerical example inspired by Marx’s principles. Imagine a debtor requiring 100 pounds. In modern capitalist terms, this situation mirrors the tally system’s principles. The debtor initiates the process by creating a financial instrument akin to the tally stick’s “stock,” representing a claim to 100 pounds. Concurrently, an obligation to repay the amount emerges, similar to the “foil” in the tally system. This scenario generates a symbolic “tally” where credit (+100) and debt (–100) are born simultaneously, resulting in a net zero debt value.

During the circulation phase, the debtor transfers the 100-pound claim to the creditor, who now holds a financial instrument representing the claim. The creditor’s holding of this claim resembles the “stock” from the tally system, while the debtor’s continued obligation to repay mirrors the “foil.” This transaction introduces a new debt of –100 pounds (=0–100), reflecting the debtor’s obligation.

The final phase, analogous to the tally’s cancellation, occurs when the debtor repays the loan. The creditor presents the financial instrument, now worth (0–100) pounds, indicating the need for repayment with the interest. Upon the debtor’s fulfillment of their obligation, the net debt amount transitions from –100 to zero, symbolizing the debt’s cancellation.

Through this numerical example, we illuminate the processes of debt creation, circulation, and elimination, drawing parallels with historical practices and contemporary financial instruments. This analysis sets the stage for a more generalized formula for debt in capitalist economies.

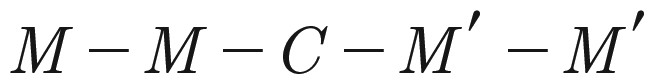

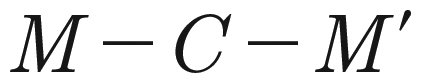

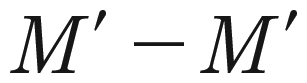

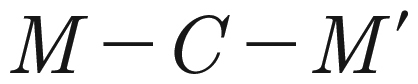

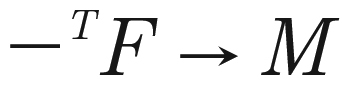

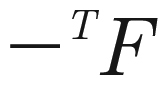

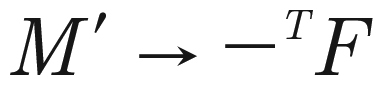

Building on the numerical example, let us introduce a more generalized formula for debt. We employ the negative sign to refer to debt in positive value terms (i.e., in absolute value terms), denoting debt as  , where

, where  stands for positive debt.Footnote5 Furthermore, we replace the hyphen with an arrow to signify the transformation process, thereby distinguishing it from the minus sign.Footnote6 The arrow then should be read as “is transformed into,” indicating metamorphose in the circuit of capital. In the initial phase, as the debtor creates the claim and obligation, the net debt change is calculated as

stands for positive debt.Footnote5 Furthermore, we replace the hyphen with an arrow to signify the transformation process, thereby distinguishing it from the minus sign.Footnote6 The arrow then should be read as “is transformed into,” indicating metamorphose in the circuit of capital. In the initial phase, as the debtor creates the claim and obligation, the net debt change is calculated as  , suggesting no substantial value creation. The debtor then transfers the 100-pound claim to the creditor, while retaining the obligation to repay. This leads to a net debt change of –100 equating to a debt of pounds. This transaction can be represented as

, suggesting no substantial value creation. The debtor then transfers the 100-pound claim to the creditor, while retaining the obligation to repay. This leads to a net debt change of –100 equating to a debt of pounds. This transaction can be represented as  , where the debtor incurs a debt (

, where the debtor incurs a debt ( ) to acquire money (

) to acquire money ( ). Next, we follow the sequence

). Next, we follow the sequence  , representing the merchant capital operation. Finally, the debtor repays the debt, symbolized by

, representing the merchant capital operation. Finally, the debtor repays the debt, symbolized by  . Upon repayment, the debtor acquires the “stock” equivalent (

. Upon repayment, the debtor acquires the “stock” equivalent ( = 100), nullifying the debt (

= 100), nullifying the debt ( ).

).

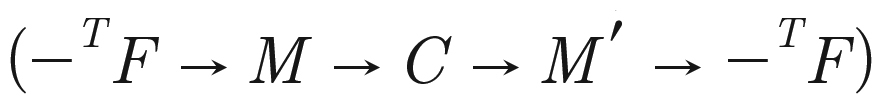

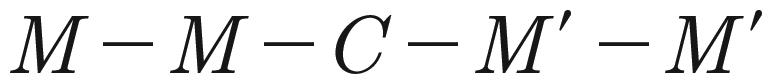

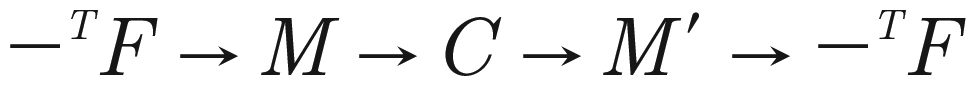

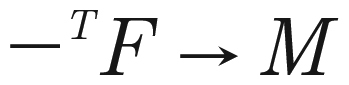

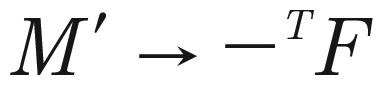

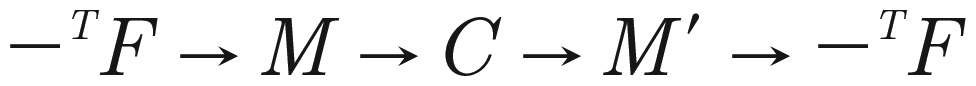

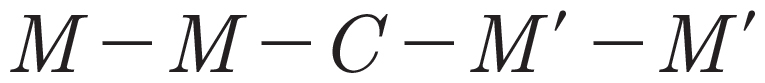

Thus, the general formula for debt emerges:  . In the next subsection, we delve into the implications and interpretations of this formula.

. In the next subsection, we delve into the implications and interpretations of this formula.

A New Formulation of the Interest-Bearing Capital and Debt

The proposed formula,  interweaves the traditional circulation of merchant capital (

interweaves the traditional circulation of merchant capital ( ) with an innovative representation of borrowing and repayment processes (

) with an innovative representation of borrowing and repayment processes ( and

and  ). We finally shed light on these latter aspects, vital yet often underrepresented in debt mechanics analyses.

). We finally shed light on these latter aspects, vital yet often underrepresented in debt mechanics analyses.

Borrowing (Sale of Financial Instruments): The initial step,  symbolizes borrowing. Here, the borrower takes on a debt (

symbolizes borrowing. Here, the borrower takes on a debt ( ) to acquire money (

) to acquire money ( ), akin to selling financial instruments. This mirrors the traditional

), akin to selling financial instruments. This mirrors the traditional  transaction in commodity exchange, where commodities (

transaction in commodity exchange, where commodities ( ) are sold for money (

) are sold for money ( ).

).

Repayment (Distribution of Profit): The concluding phase,  represents debt settlement, where the debtor repays the principal and interest (

represents debt settlement, where the debtor repays the principal and interest ( ). This step involves returning the financial instruments, effectively eradicating the debt. Contrary to conventional purchase transactions, this repayment is unilaterally binding, reflecting the distribution of profit, as illustrated in Marx’s Capital Volume III. It signifies the division of profit into interest (for the creditor) and enterprise profit (for the debtor). This distinction highlights that

). This step involves returning the financial instruments, effectively eradicating the debt. Contrary to conventional purchase transactions, this repayment is unilaterally binding, reflecting the distribution of profit, as illustrated in Marx’s Capital Volume III. It signifies the division of profit into interest (for the creditor) and enterprise profit (for the debtor). This distinction highlights that  transcends mere circulation, embodying a profit distribution mechanism.

transcends mere circulation, embodying a profit distribution mechanism.

In summary, the expanded formula  advances our understanding of the intricacies within debt transactions, framing them within the broader context of Marxian economic theory and emphasizing their role in the distribution of profits within capitalist systems.

advances our understanding of the intricacies within debt transactions, framing them within the broader context of Marxian economic theory and emphasizing their role in the distribution of profits within capitalist systems.

Concluding Remarks

In light of the extensive exploration and discussion presented in this study, we can synthesize our conclusions as follows.

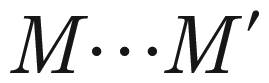

First, we have proposed a comprehensive formula for capital with debt, encapsulated as  . This formula illustrates the debtor’s financial dynamics, representing both the creation of an IOU and the obligation to repay.Footnote7

. This formula illustrates the debtor’s financial dynamics, representing both the creation of an IOU and the obligation to repay.Footnote7

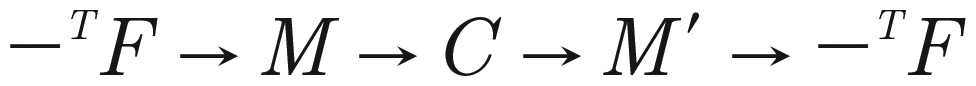

The diagram in encapsulates the process:

The top row of this diagram represents the creditor’s movement of money-lending capital  , while the bottom row demonstrates the debtor’s capital movement, as described by our newly proposed formula. The intersecting arrows signify the essential transactions between creditor and debtor, elucidating the processes of loan and settlement.

, while the bottom row demonstrates the debtor’s capital movement, as described by our newly proposed formula. The intersecting arrows signify the essential transactions between creditor and debtor, elucidating the processes of loan and settlement.

The first intersection represents the loan process, whereby money and financial instruments are exchanged between the debtor and the creditor. The creditor purchases the financial instruments from the debtor, who uses these funds to initiate their capital cycle.

The final intersection portrays the settlement process, where the financial instruments return to the debtor, and the loaned money (plus interest) is repaid to the creditor. This process is multidimensional; it can be interpreted as the creditor’s money collection, the debtor’s debt repayment, the debtor’s distribution of interest from profit, and the creditor’s consumption of the financial instruments’ formal use-value.

This new representation allows us to distinguish between the processes of loan and settlement, which were previously conflated or obscured in Marx’s original formulation ( ) and Uno’s modification (

) and Uno’s modification ( ). Our model, in contrast, shines a light on the importance of financial instruments and articulates the distinct roles and responsibilities of the debtor and creditor.

). Our model, in contrast, shines a light on the importance of financial instruments and articulates the distinct roles and responsibilities of the debtor and creditor.

In conclusion, this formulation provides a comprehensive and nuanced representation of capital with debt in Marxian economics. It enhances our understanding of the various processes and roles involved in the movement of capital, leading to a clearer picture of financial capitalist economies. Future research is encouraged to further explore this perspective and its implications for Marxian economic theory and practice.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Takashi Satoh

Takashi Satoh is a professor of Marxian economics and analytical political economy at Ritsumeikan University. This article has been refined from its initial version, presented in Japanese at the Seinan branch meeting of the Japan Society of Political Economy (JSPE) in June 2023, utilizing the feedback received there. Special thanks are extended to Costas Lapavitsas for his insightful suggestions; although, regrettably, not all could be fully incorporated into the final manuscript. Further appreciation is directed towards Ellie Paton, Collections Manager at the Bank of England Museum, for her assistance in providing invaluable materials regarding tally sticks. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

Notes

1 See Uno (Citation2022) in Ehara (Citation2022). Uno (Citation1980) also delves into the motion of money-lending capital and merchant capital.

2 See Itoh and Lapavitsas (Citation1999) for further discussion. Itoh and Lapavitsas (Citation1999) argues the formula of industrial capital in this formulation, instead of merchant capital.

3 Earlier initiatives like Sekine (Citation1997 and Citation2021) have attempted to weave credits and debts into the formula of capital. However, these efforts fell short of a complete formulation of money-lending capital and debt. This article fills that gap, articulating a detailed integration of both money-lending capital and debts into the Marxian framework.

4 The delineation of tully’s account is based on Stone (Citation1975).

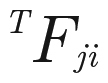

5 The notation  in our model explicitly represents debt. For instance, consider

in our model explicitly represents debt. For instance, consider  as the financial instrument denoting the credit extended by the ith agent (creditor) to the jth agent (debtor). The same financial relationship, when viewed from the debtor’s perspective, is expressed as

as the financial instrument denoting the credit extended by the ith agent (creditor) to the jth agent (debtor). The same financial relationship, when viewed from the debtor’s perspective, is expressed as  . Here, the “

. Here, the “ “ in the superscript signifies a transpose, shifting the focus to the debtor’s obligation. This notation ensures clarity in representing debt, distinguishing it from the credit perspective in our analysis.

“ in the superscript signifies a transpose, shifting the focus to the debtor’s obligation. This notation ensures clarity in representing debt, distinguishing it from the credit perspective in our analysis.

6 We follow this expression proposed by Weeks (Citation2010).

7 Graeber (Citation2011) offers a sweeping theoretical and historical perspective on debt. Nevertheless, his examination misses key processes that are critical to our analysis: both the origination and the eventual elimination of debt.

References

- Ehara, Kei (ed.). 2022. Japanese Discourses on the Marxian Theory of Finance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

- Itoh, Makoto, and Costas Lapavitsas. 1999. Political Economy of Money and Finance. New York: Macmillan.

- Sekine, Thomas T. 1997. An Outline of the Dialectic of Capital, vol. 1–2. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Press.

- Sekine, Thomas T. 2021. The Dialectics of Capital: A Study of the Inner Logic of Capitalism, vol. 1–2. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Stone, Williard E. 1975. “The Tally: An Ancient Accounting Instrument.” Abacus 11: 49–57.

- Uno, Kōzō. (1954) 1974. “Shikinron.” (“Fund Theory.”) In Uno Kōzō Chosakushū Dai Yonkan (Collected Works of Uno Kōzō Vol. 4), 186–205. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Uno, Kōzō. 1980. Principles of Political Economy: Theory of a Purely Capitalist Society. Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press.

- Uno, Kōzō. 2022. “On Money Capitalists in the Theory of Interest in Capital.” In Ehara (2022). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-83324-4_2

- Weeks, John. 2010. Capital, Exploitation and Economic Crisis. London: Routledge.