ABSTRACT

This paper has explored teachers’ integration of ICT in a primary school practice, in particular how the content and its subject matter emerge in teachers’ preparatory discussions and how they are enacted in the classroom. The theoretical foundation lies in the tradition of Didaktik and the analysis focuses on the teachers’ choices of content in relation to ICT, and how the content and its matter are enacted in the classroom.

The analysis indicates a lack of discussion of the subject matter and of the aims for how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils. Further, the teachers’ choices to demonstrate different software resulted in enacting the software as the content. Consequently, the way the teachers demonstrated the software in classroom teaching could be seen as a shift to direct ICT use, i.e. an interaction between the pupils and the software. The way in which the teachers in the study chose to use their pedagogical freedom, in relation to the integration of ICT in the primary-school classroom, raises an important issue regarding the importance of highlighting teachers’ didactical competences in relation to ICT.

Introduction

During the last decade in Sweden, there have been huge investments in digital devices in compulsory school. The argument for these investments was, and still is, that technology is a key enabler for bringing about the necessary fundamental innovation and modernization of education (Selwyn & Facer, Citation2013). Much of the debate about ICT and education focuses on digital technology as a catalyst for changes in teaching style, learning approaches, and access to information (Selwyn, Citation2016).

In Sweden, as well as in many other countries, teachers are supposed to find operational ways of integrating ICT into teaching. In that process, local ICT policies are developed from national and global guidelines but also through the influences of economic interests in schools (Player-Koro et al., Citation2017; Selwyn et al., Citation2017). The optimistic rhetoric in the policy documents published by the Swedish government foregrounds technology in education and its potential to enhance educational environments. This is salient in national policy documents, which emphasize that ICT could improve education and lead to pedagogical development and a new role for the teacher.

Despite more than four decades of research, there is still a lack of evidence that educational technology meets the optimistic expectations in the policy documents (Oliver, Citation2011; Selwyn & Facer, Citation2013). The introduction of a new technology alone does not guarantee improved learning experiences or greater learning outcomes (e.g. Engeness, Citation2020; Prieto et al., Citation2011; Wegerif, Citation2010); teachers find the classroom practice challenging and ask for more ICT training (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2013, Citation2016). With regard to these challenges, this paper focuses on teachers’ didactical relationship with ICT and relates directly to teachers’ choices of subject content and their use of ICT in the classroom.

The implementation of 21st century competences concerns the role of teachers and their professional development in forms of innovative teaching approaches, such as: problem-based and co-operative learning (Voogt & Roblin, Citation2012). This is based on the assumption that students have to construct their own understandings and knowledge, and teaching has become understood as the facilitation of learning rather than ‘being taught’ by the teacher (Biesta, Citation2013). This shift from teaching to learning is accompanied by the rhetoric connected to the use of ICT (Haugsbakk & Nordkvelle, Citation2007).

On the Swedish curriculum level, the influences of European policies have resulted in ideas about organizing school knowledge in terms of competencies (Sivesind & Wahlström, Citation2016). Recent revisions in the Swedish curricula were made in 2017 to strengthen students’ digital competences (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2017). The guidelines emphasize the use of ICT in teaching without explicitly problematizing how ICT should be integrated in relation to the subject domains (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, Citation2017). Digital competence is not part of assessment and therefore cannot be referred to as a standard to be obtained but rather as a skill to use in order to acquire achievements within the subject domains.

The changes around the use of ICT have led to new expectations about teachers’ work and their roles in facing and dealing with challenges and changes (Edwards, Citation2015). Factors that influence ICT integration can be manifold and complex, but a body of research has shown that the key to the effective use of ICT in education relies very heavily on how successfully teachers integrate it into teaching and learning (e.g. Nikolopoulou & Gialamas, Citation2015).

In this paper, the aim is to explore the use of ICT, in particular the relation between the content and subject matter in the teacher’s selection of the subject matter and how it is enacted in the primary classroom. The theoretical foundation of this paper is the tradition of Didaktik (Hopmann, Citation1999, Citation2007), which addresses the Didaktik triad of questions (what, why and how) as a whole. This serves as an exploratory and classificatory structure, and relates the general elements of the teacher, the content and the student to each other (Hopmann, Citation1999; Klafki, Citation1995). However, in this paper, the focus is on the relationship between the teacher and the content, and the enactment of teaching and learning.

Many research studies with a particular focus on ICT in relation to the content have been conducted since the beginning of the 21st century, showing that changes in practice are more often related to issues of management and organization than to learning and assessment objectives (e.g. Hennessy et al., Citation2005; John, Citation2005; Watson, Citation2001). Findings have also indicated a perceived conflict concerning whether to use ICT in order to facilitate subject learning, or whether the emphasis should be on demonstrating ways in which ICT can be used and on teaching technical skills (Hennessy et al., Citation2007).

However, later studies on the role of contemporary technologies in classrooms point more in the direction of focusing on digital technology from perspectives that underline distinctive ways in which the computer software can participate in and support education (e.g. Björkvall, Citation2014; Edwards-Groves, Citation2011; Flewitt et al., Citation2015; Hillman & Säljö, Citation2016; Jewitt, Citation2014; Stenliden et al., Citation2017).

Many studies from the Swedish and international contexts highlight the complexity in digital environments (e.g. Nilsen et al., Citation2018; Voogt & Roblin, Citation2012). Teachers´ aim to teach with ICT and teachers’ pedagogical reasoning about the appropriate use of the technologies seem to be important (Holmberg et al., Citation2018; Tay et al., Citation2012). Research findings also emphasize the crucial importance of teachers’ awareness about the type of support that ICT and other resources can provide, with the purpose of integrating digital resources to enhance pedagogy and students’ capacity to learn within and across subject domains (Engeness, Citation2020; Tay et al., Citation2012). The teachers’ close assistance at the beginning of the lesson seems help the learners to develop their understanding about how to approach the task and to reveal the potential of the resources useful for solving the task. In doing this, the teacher may have enhanced the learners’ understanding of how to engage with the task (Engeness, Citation2020).

Examples from primary classrooms show that using ICT without a clear method does not bring about improvements and that digital resources need to be matched to the pedagogic intention of the teacher (e.g. Genlott & Grönlund, Citation2013; Kervin et al., Citation2019). These findings have opened up the interest to further investigate teachers’ integration of ICT in a primary school practice.

The complexity of preparing for teaching with technology is also in focus in studies based on the tradition of Didaktik (Hopmann, Citation1999, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007; Klafki, Citation1995). These studies conclude that teachers preparing to teach with ICT in schools would benefit from considering how the didactic relation between the ‘what, why and how’ of content and ICT can be articulated clearly (e.g. Hudson, Citation2007; Loveless, Citation2007, Citation2011). Findings show that there is a tension between ICT as a direct subject domain and as a resource to support curriculum learning (Loveless, Citation2003, Citation2007). Loveless (Citation2007, Citation2011) argues that a framework of teacher professional knowledge that highlights the relations between subject domain knowledge, digital technologies and various teaching situations can support teaching with ICT.

One assumption of this paper is that Didaktik provides ways of thinking which highlight educational ICT questions (Hudson, Citation2007) that could contribute to pedagogical perspectives in Sweden and in other countries. With this in mind, the research questions of this paper are formulated from a didactical perspective concerning the content and the subject matter:

How do the content and its subject matter emerge in teachers’ preparatory discussions in teachers’ integration of ICT in a primary school practice?

How are the content and its subject matter enacted in the classroom?

A tool for the analysis is the Didaktik triad, i.e. the relationships between teacher, student and content, with particular focus upon the teacher and the content, which according to Didaktik is the core of a teacher’s professionalism (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007).

Theoretical foundation

The theoretical foundation of this study is the Central and Northern European tradition of Didaktik (Hopmann, Citation2007; Klafki & MacPherson, Citation2000). In the Nordic countries, current practices are to some extent based on the tradition of Didaktik (Kansanen, Citation2002). Sweden has an inheritance of Didaktik which was revived in the early 1980 s after being out of use for some decades (Bengtsson, Citation1997; Nordkvelle, Citation2004). The Swedish curricula have since then been influenced to a greater or lesser extent by the German Didaktik tradition. Today in Sweden, education has an orientation towards competence curricula and learning goals, with a focus on school subjects (Sivesind & Wahlström, Citation2016). Despite the use of ICT and competence frameworks, Didaktik provides ways of thinking about educational questions and the German notion of Bildung is still crucial in discussions related to education (Friesen, Citation2018).

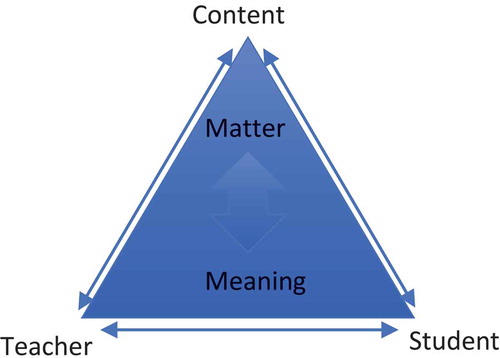

In this paper, Didaktik provides a framework for exploring teachers’ enactment of the most fundamental how, what and why questions in relation to the content and the subject matter being taught. Hopmann (Citation2007) distinguishes between content and subject matter in terms of the teacher’s selection of the subject matter in relation to the content and the student. The substance of the subject matter could be seen as a meeting between the teacher, the content and the student: ‘Any given matter can represent different meanings and any given meaning can be opened up by many different matters’ (Hopmann, Citation2007, p. 116). (see ).

Figure 1. The Didaktik triad and the concepts of matter and meaning (Hopmann, Citation2007)

In the Didaktik triad (), meaning is what emerges when the content and its matter are enacted in a classroom based on the methodological decisions of a teacher, which are a part of what constitutes the teacher’s pedagogical freedom. It is a question of the teacher’s choices when dealing with a given content in relation to the enactment of the matter with the aim of opening up the educative substance for the students in their individual meeting with the matter in the given teaching process.

The decisions regarding curricula remain part of the ‘inner-didactic discourse’ (Hopmann, Citation1999, p. 93), meaning that the school practitioners do their own planning, more or less within the framework of the guidelines. In other words, among teachers, there is a pedagogical freedom or freedom of method, i.e. they can choose what is valid in teaching (Hopmann, Citation1999; S. T. Hopmann, Citation2003).

On the one hand, the curriculum gives general directions and thus restricts the degree of freedom to act in the institutional context (Kansanen, Citation2002). The current Swedish curriculum has descriptions of core content in line with a ‘conditional program’ (Sivesind, Citation2013). On the other hand, there are also descriptions of achievement in terms of learning processes and products in line with a ‘purposive program’. The curriculum thus consists of a mix of conditional and purposive programmes and serves as a frame for teachers’ planning. In other words, there is a tension between a teacher-oriented and a learner-oriented approach, in which teachers have to consider how the subject content could be made relevant in relation to pupils’ potential and their previous experiences (Bachmann, Citation2005).

When transforming content from the national curriculum into lesson planning, teachers’ responsibility is to decide on what specific content should be taught in a particular lesson and why. In the tradition of Didaktik, this is explained as a dimension of teachers’ rhetorical act of re-thinking the intentions of the curriculum guidelines, while at the same time selecting and organizing what is worthy of being taught (Künzli, Citation1998). During teachers’ preparatory work, the relation between teacher and content becomes crucial.

Digital technology is nowadays one of the tools alongside others that afford possibilities and limitations in teaching and learning in schools. In teachers’ integration of ICT, the formal curriculum serves as a frame for teachers’ planning but the policy documents do not exemplify how teachers may design, plan and organize teaching with ICT and how they communicate the content, which opens up a space of freedom as well as entailing responsibilities for the teacher. Teachers have opportunities to re-think what the curriculum makers intended and consider how the content and its matter could be enacted in the classroom. It is a matter of teachers’ choices about how the subject matter can be interpreted as meaningful to the pupils (Willbergh, Citation2015).

However, in what way the teachers use their pedagogical freedom in regard to the curriculum guidelines and the expectations that surround the use of digital technologies is an empirical question. Therefore, it is urgent to investigate teachers’ choices when dealing with the content and the enactment of the subject matter in relation to ICT tools in their classroom teaching. The relationship between teacher, content and student can give rise to the traditional didactical questions of what content is chosen, why it is chosen and how it is enacted in the classroom, which are explored in this paper. In addition, the didactical approach includes a process of critically questioning the purpose of the added value of ICT use and whose interests are served by ICT (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007).

Material and methods

This paper is a part of a larger ethnographical study conducted in a primary school located in the south of Sweden. The larger study has the ambition to gain knowledge about patterns between teachers and pupils in everyday classroom interaction (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007). Whereas the overall research focus is the possibilities and limitations of ICT use in relation to content, design and interaction, rather than what the technology itself can bring to a primary-school practice. Moreover, ethnography as a research-approach usually involves the researcher participating over an extended period of time, watching, listening, asking questions, collecting documents (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007), which also means that the researcher must be prepared to consider many different types of data. The researcher has to be engaged in the material, to invest time and to have a mutually trustful human connection with the participants (Walford, Citation2008). The research methods used in the study are the ethnographic techniques of long-term observation of classroom practice, formal and informal interviews with teachers and pupils and the use of written material such as school documentation.

Previous results from the study has been published in three papers. The results show a variety in the interaction patterns between the pupils and subject content of the software (Öman & Sofkova Hashemi, Citation2015; Öman & Svensson, Citation2015). An analysis of the final products created by the pupils stresses that the impact of the instruction and the teacher’s design on pupils’ meaning-making needs to be considered and further explored (Kjellsdotter, Citation2017).

The focus of this particular paper is the classroom practice and a descriptive approach to Didaktik, where the aim is to conduct empirical education studies (Bengtsson, Citation1997). The analysis in this paper relies on the thick ethnographical data collection in order to investigate a didactical dimension of classroom interaction, namely the one relating content, teachers and pupils to each other in the digitalized classroom, at Bezel primary school.

Bezel primary school

Bezel is a Swedish public primary school situated in the south of Sweden, in a middle-class area where the school children come from various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, and has about 300 pupils from 6 to 12 years of age. The school has an ICT profile and is engaged in ICT projects, which includes all pupils having access to a digital artefact (a laptop or tablet computer). The school was involved in a project called ‘2-to-1ʹ, which started in February 2009, where two pupils shared one laptop, which was frequently used in learning activities in more or less all subjects.

The study presented in this paper focuses on a school context in which the school was to make a development plan for the implementation of ICT and, together with seven other schools, provide a good example of ICT teaching for the rest of the schools in the municipality. Bezel primary school had applied for and was selected together with seven other schools in the municipality to become a model for evaluation for further ICT implementation in all schools in the municipality. The school fulfilled the criteria for being a selected school such as: ICT competence, competence for working in teams, being open to changes, multiculturality, and a range of ages of pupils in the school.

The idea was to further invest in digital technology and to scale up the investment so that it would cover all the schools in the municipality. During the time of the study, investment in so-called one-laptop-per-student (1:1) initiatives was the most common way for local school ministries in Sweden to encourage and push for the integration of ICT in schools.

In developing a local ICT plan for a five-year period, from 2010 to 2015, the principal of the school created a school ‘pilot group’ in which five teachers from the school, here called Alana, Beata, Cecilia, Diana and Eve, were members. These teachers had between 7 and 20 years of teaching experience in elementary schools. The plan was written by three of the teachers in the group together with the principal and there was a desire to develop new ways of teaching by integrating ICT into daily practice. The idea of the group was to create a collective knowledge of ICT in education, which could be distributed to all teachers in the school, using the local development plan with the title: The ICT development plan of Bezel primary, from December 2010 to August 2015, for teachers, pupils and parents. The ICT development plan was a kind of roadmap for the process of developing collective knowledge about ICT in education, i.e. what teachers, pupils and parents should do and how this should be done.

The pilot group consisted of teachers with good insights into and willingness to use ICT technology. Overall, there was an interest in integrating ICT into teaching among all the staff at the school, which contributed to the school’s reputation for having an innovative approach. The aim was to increase the number of and the use of digital artefacts by 2015, which included: providing a device to all pupils by that time; involving parents in becoming familiar with these digital artefacts as a natural part of the pupils’ learning processes, and developing the teachers’ competence in relation to digital artefacts in order to redefine their perspectives on knowledge building.

Data collection

The data was produced by studying written policy documents, taking field notes, recording and, later on, transcribing audio- and videotapes. Altogether, the data corpus of this study consists of approximately 28 hours of audio and video material plus field notes consisting of interviews and classroom observations. Three months of participant observation from the total body of fieldwork has informed this paper in order to consider the context in which knowledge about teaching and learning operates.

The fieldwork was concentrated on approximately 120 lessons (1-hour lessons) where teachers and pupils worked with digital technologies in a third-grade classroom, discussions from five meetings (10 hours in total) in the pilot group, and formal and informal interviews with the five teachers in the group. The different data collections have been processed and analysed in relation to the research question regarding how the content and the subject matter are developed during pilot-group meetings and by the teacher in the classroom integration of ICT, which is a part of the ethnographic work (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007).

During the ethnographical work, field notes of the observations were made during and after every school day. The field notes taken during the observations presented in this paper were written down during the five meetings of the pilot group and also during classroom activities. During classroom observations, protocols were used with the purpose of capturing teachers’ and pupils’ interaction with ICT. The discussions from pilot-group meetings were audio recorded and classroom observations were video recorded. Video recordings were used in order to record aspects of classroom activities in real time and to provide opportunities to transcribe and analyse film segments several times (Heath et al., Citation2010; Wolfinger, Citation2002). The video represents a selected event available for analysis and from an ethnographic perspective, videos and other field notes are ways of representing the social context. Both audio and video recordings were transcribed digitally. The formal semi-structural interviews with teachers in the pilot group were audio recorded and transcribed in the same way. These interviews were carried out individually after the school day. Informal interviews were regularly carried out during the school day and were valuable in the sense of clarifying the observations of teachers’ enactment in the classroom.

After finishing the data collection, the next step was to obtain a preliminary review of the data corpus. Video recordings, field notes and audio recordings were digitally organized and summarized, divided into different parts and then put together to get an overview (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007).

Analysis

In order to explore the research questions of this paper, classroom observations and discussions from the pilot-group meetings became the primary data sources. The formal and informal interviews serve as complementary sources in the analysis of this paper. The ICT policies from the municipality and the school serve as background material. The material in these different parts enabled me to compare and contrast aspects of the data in the analytical process (Heath et al., Citation2010).

In the analysis, the theoretical foundation of Didaktik (Hopmann, Citation2007) provides a framework which places the teacher at the heart of the teaching-learning process, and highlights the autonomy of the teacher and teachers’ enactment of the fundamental what, why, how questions around their work (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007). The Didaktik triad is here reduced to a focus on how the content and its matter are intertwined with the teachers’ orchestration of ICT, i.e. teachers’ design of task, instruction and real-time classroom activities. Additionally, by going back and forth and analysing the ethnographical data, using concepts in the tradition of Didaktik, samples of the data corpus were compared (Silverman, Citation2010). Hammersley and Atkinson (Citation2007) have suggested that the analytical process is iterative and that there should be a movement back and forth between theories and data.

After repeated analysis of the data corpus, the material was categorized in relation to the preparatory discussions of teachers’ choices of content and its subject matter, and how the content and the subject matter were enacted in the classroom. The analysis continued by narrowing down the common features of the relationship between teachers and content starting in the categories of teachers’ preparatory discussions, in order to give rise to the traditional didactical questions of what content, why and how?

The next step was to identify the transformation of curricular content into the local teaching in relation to ICT integration in the primary school. The analytical lenses were concentrated on teachers’ choices of what content and subject matter in relation to curricular subject domains and how they have been enacted in the classroom in relation to the digital technologies available to teachers (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007). According to Hopmann (Citation2007), this is a way of understanding how the subject matter is enacted and how the teaching intentions, i.e. the educative substance, become part of the teaching process.

A key tool for the analysis in this paper is the relation between the concepts of the content, its matter and its educative substance that serve as an analytical tool in the process of categorizing teachers’ choices of subject content in relation to ICT. This was performed by analysing the rich data of preparatory discussions in the ICT pilot group and observations of teachers’ demonstrations of the tasks together with teacher interviews. More precisely, the analysis focuses upon teachers’ choices of subject matter in relation to a given content and how it is enacted in the classroom to open up the educative substance for the pupils in the creation of meaning. According to Hopmann (Citation2007), the question is how the subject matter will be enacted in relation to, for example, conceptual or structural changes and how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils in the meeting with the content in a given process. The pupils’ educative meaning is defined as that which emerges when the content is enacted in a classroom based on the methodological decisions created by the teachers’ pedagogical freedom (Hopmann, Citation2007).

To sum up, the data analysis focused upon the teachers’ negotiations about the content, the subject matter and the educative substance in relation to ICT in the primary practice. The findings presented here concern how the school practitioners do their own planning. This entails analysis of how the inner-didactic discourse was formed at meetings and transformed into classroom teaching. In order to answer the research question concerning the content and the subject matter, the analysis was not focused on how pupils learn or what pupils should be able to do or know. Rather, it focused on the teachers’ choices of content, the enactment of the matter and asking what this can signify to the pupils, and how pupils themselves are able to experience this significance (Hopmann, Citation2007; Künzli & Horton-Kriiger, Citation2000).

Results

In this study, the five teachers together with the principal of the school regularly held pilot-group meetings. The main agenda of the meetings consisted of sharing information about new insights, e.g. the teachers’ own classroom experiences or information from school conferences, discussing potential software and the teacher’s role in relation to ICT. The classes in which teachers in the pilot group were teaching were part of the ICT integration plan and also documented in the local development plan of the school. The analysis was concentrated on the way in which the content and the subject matter emerged and were enacted in the ICT classroom. The findings are presented under two sub-headings:

The emergence of the software as content’ and ‘Enacting the software in the classroom.

The emergence of the software as content

For the teachers, the work in the pilot group was the starting point for the journey towards the development of knowledge for ICT in education. This knowledge was operationalized as working with different software applications. The intention, according to the local ICT plan, was that this would lead to sharing of experiences, which was to take place by May 2011: ‘We have found a way of sharing learning about ICT with everyone [at school]’. According to the text in this plan, learning about software applications and sharing this knowledge among colleagues will lead to changes in teachers’ professional role. There was a consistency in the pilot-group between the teachers’ comments and what is expressed in the school’s ICT plan.

In the pilot-group meetings, the principal of the school and all five teachers brought their own laptops, and the projector was frequently used in order to demonstrate various ICT tools, e.g. a website from the British Council (https://learnenglishkids.britishcouncil.org/) and Storybird (https://storybird.com/). An example from one of the meetings illustrates how the software emerged as the content for teaching with a demonstration of a story-composing software, Storybird. Storybirds are short, art-inspired stories with an instructional movie where you can easily learn how to create a story and to pick up and drag pictures.

The meeting started with a demonstration by one of the teachers in the group, Beata. She presented a story created in the software. The story consisted of text and image () made by one of the pupils during an English lesson. During the demonstration, the positive experiences of using the software in teaching were put forward.

There are a lot of good things about Storybird … the pupils can create stories … as you can see and it is also possible to make classrooms in Storybird in order to save pupils’ work … on YouTube there is a demonstration film called ‘The school bag’ I will show you …Beata [audio recordings]

Beata continued the demonstration with a YouTube clip, focused on the possibilities of using Storybird and the various themes of content that could be taken into account.

I have been working a lot with Storybird … we had a theme about friendship and also Christmas stories … and one of the pupils who usually does not write very much did well … he did not write that much but it is a lot for him …Beata [audio recordings]

The following discussion in the pilot group concerned advantages of using Storybird in relation to the organization of pupils’ work, e.g. files for different tasks, but also as an opportunity for pupils who usually have difficulties in finding motivation for schoolwork. The discussion continued with some of the other teachers sharing their ideas and experiences:

The software includes a lot of possibilities, which is a great opportunity for teachers if you want to use them … I think it is a good thing to make instructional films in Quick Time … the pupils could watch them and work more independently from the teacher … it would make things easier for us … I have already made an instructional film about how to use Google Earth in case the pupils have questions or problems, they could watch it instead of asking me …Diana [audio recordings]

The example above shows a common way of demonstrating software in the pilot group. The teachers tried to define the content of the classroom teaching and pointed out that there were a lot of software options in almost all subjects, but also that there were problems with choosing the right software because of the large number of options. Rather than discussing the subject matter related to the content, they negotiated possible content by showing options for different software based on the directions of the local development plan. The teachers’ own experiences of software came into focus regarding what content the classroom teaching should focus upon. Consequently, the software, with its possibilities and/or limitations for the pupils, became the content. This will be illustrated by means of the audio recordings, which started with a question from the principal during one of the meetings and teachers’ responses to this question:

Can you say something about learning and software and whether it is motivating?Principal [audio recordings]

I think that the pupils are making increasing progress by using the laptop and there is a lot of good software and they can also help each other … The cooperation between teachers and pupils is important, we need to know how it is working and if the pupils think that they learn new things as well as if it has affected their school work. Most important is what they find is the best thing with laptops in education.Eve [audio recordings]

There are a lot of changes, the laptops make things easier for the pupils, they find things easy which creates another way of learning … and there are examples …. they dare to talk more easily in English by recording their voices in different software.Beata [audio recordings]

The statements above demonstrate a faith that laptop features would lead to changes in education. Turning to the data, the principal of the school raised a critical question in relation to software:

You must be critical of the software, do not use not everything […] start with the syllabus goals but use ICT.Principal [audio recordings]

This quotation illustrates how the focus of teaching with ICT emerged in the pilot group. The principal’s statement shows a way of handling ICT as the important content to take into consideration together with the syllabus goals of the Swedish curriculum.

The principal invites a discussion; however, the analysis shows a lack in the discussion regarding the choices of subject matter and how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils in relation to the software. As a consequence, this depended on the interaction between the pupils and the mediating software. The teachers’ focus on the software as the content meant that they expressed a need for further ICT training:

I feel a great need for more knowledge about various applications … and I have asked for help from the IT department in the municipality … Per and Anders [IT support] will come and help us if they have time …Cecilia [audio recordings]

The IT support didn’t show up during three months of fieldwork and in one of the meetings one of the teachers stressed the importance of professional ICT training, arguing that the ‘technical support in the municipality’ should educate all the staff. There was a desire to be more knowledgeable in relation to technological issues. This was a recurrent topic in the pilot group, e.g. where to publish pupils’ work, the techniques of producing digital instructions with the aim of being a resource for pupils or sharing pupils’ work.

The teachers in the pilot group—all with between 7 and 20 years of teaching experience—agreed that the use of ICT would change the teacher’s role. The recurring question at the meetings in the pilot group concerned the change in the professional role in relation to ICT in teaching, something that could be traced to the local ICT plan, which suggests that the teachers should discuss a change in teachers’ professional role. The overall objective with the ICT implementation that should be achieved in 2015: ‘We have a new professional role! We have a redefined perspective on teaching and knowledge’ [Local ICT plan].

The analysis shows that this change included the educational practice in many ways, i.e. in what way members in the pilot group talked about changes in the teacher’s professional role and the outcomes of the change in classroom teaching. The teachers also pointed out specific changes in relation to the orchestration of software in teaching.

The change in the teacher’s role is more than the technology … other ways of orchestrating teaching … We get a lot of support when we can work together and then we can get inspired … and it is very good to use laptops in education because the pupils find it more fun to do classroom work and they are so skilful when it comes to teaching and learning from each other.Diana [audio recordings]

They [the pupils] can work more independently […] I could get more time to help pupils with special needs … . and I become more of a coach …Alana [audio recordings]

Alana’s comment can be related to the possibilities of using pedagogical freedom to develop the interaction between the pupils and the knowledge built into the software and in that way changing the professional role in the direction of a coach rather than a lecturer. The principal’s comment expresses something similar:

Everything goes faster now […] you know like finding words in dictionaries on the computer, finding information and the pupils turn information into knowledge. It is difficult to define learning when it’s so easy to get an answer.Principal [audio recordings]

To sum up, the pilot group demonstrated an optimistic view of ICT as having the inherent capability of changing teaching and learning. It also, according to the plan, seems to be rather unproblematic to achieve these changes; ICT seems, in other words, to have great educational potential. The analysis, applying the Didaktik framework, helped to distinguish that teachers’ choices of subject matter were never on the agenda in the pilot-group meetings; instead the focus pointed in the direction of discussing choices of various applications. The analysis shows that the discussions in the pilot group indicated a lack of discussion of the subject matter and of the aims for how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils.

The following section elucidates similar phenomena when ICT technology was put to work in classroom teaching.

Enacting the software in the classroom

The way the teachers enacted the software demonstrates similar tendencies to those found in the discussions in the pilot group and in the local development plan. Most of the software ideas demonstrated in the pilot group were orchestrated in whole-class teaching. The methodological decisions of the teachers followed a certain pattern: teachers gave whole-class demonstrations of software rather than demonstrating the design and knowledge built into the software in relation to the subject matter. The lessons included pupils’ interaction with software features, individually, in pairs or in groups. The interactions were mainly between the pupils and the software (Öman & Svensson, Citation2015).

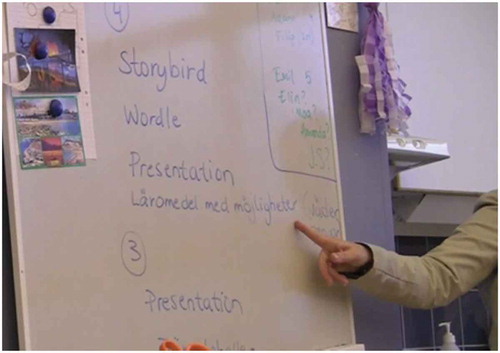

In this study, the teachers orchestrated the classroom teaching by making a brief introduction of various software options. The pupils were encouraged to create digital stories in Storybird, practise grammar in Wordle, create presentations in Keynote, including recipes for food or a description of their Christmas holidays, and finally use digital tutorials for languages and mathematics. The software options were listed on the whiteboard and the teachers demonstrated the activities afforded by the software.

The example given below aims to illustrate one of the demonstrations of software in classroom teaching.

One of the teachers, Cecilia, is pointing at the text on the whiteboard: tutorials with opportunities (see ). She turns to the class, pointing at the whiteboard and says: ‘The last line, tutorials with opportunities, where can you find it?’ One of the pupils, Sofia, raises her hand and answers: ‘In Fronter.’ The teacher responds: ‘In Fronter, yes there is a lot of stuff if you find it … and you can use the software … ’[video recordings]

Based on the data analysis, the classroom teaching continued in the same pattern: demonstration of the software was followed by pupils’ interaction with ICT, i.e. the design and knowledge built into the software. Later in the same lesson, one of the teachers continued by referring to the website of the British Council.

Beata is watching and talking to the class: On the website of the British Council, you can practise tutorials about money and the weather and they have a lot of funny songs. Do help each other if you have forgotten how to find the website, ask each other … some pupils have made a bookmark so they can find it easily. [video recordings]

In the example, the aim of the activity was to practise the English language and the teacher mainly demonstrated the particular software (the website of British council) by pointing at the text on the whiteboard. The pupils were supposed to interact with the design and knowledge building of the software, which could afford possibilities and/or limitations for opening up the subject matter and the educative substance.

Another classroom example focused on introducing film-editing software with the purpose of creating advertising films about planets in ‘Space’. In the introduction to the task during three mini lessons, the teacher focused on the film-editing software but the content of the advertising films, e.g. ‘Space’, and the genre of advertising, were left implicit for the pupils, which is exemplified below.

The teacher looks at the software displayed on the project screen and talks about features of the software application. She points at the box with a musical note and asks the class what it is (see ). One of the pupils answers: music. The teacher continues showing the icons of image and text and each icon is separately pointed out in the software. She tells the class that the photos or images could be handled in two ways: the pupils could use the computer library with a fixed range of photos or search for images for free download on websites on the Internet.[video recordings]

After the demonstration, the pupils started interacting in small groups with the film software. The way in which the subject matters of ‘Space’ or ‘advertising as a genre’ could be opened up for the pupils in the given process of making meaning depended on the pupils’ interaction with the software.Footnote1

To sum up, the analyses using the framework of Didaktik showed that the teachers’ choices to demonstrate different software resulted in enacting the software as the content. Consequently, the way the teachers demonstrated the software in classroom teaching could be seen as a shift to direct ICT use, i.e. the interaction between the pupils and the software. The way in which the pupils come into contact with the subject matter at hand was afforded by the possibilities and/or limitations of the design and knowledge built into the software.

Discussion of the ICT integration at Bezel primary

The findings presented here indicate that ICT became the content in focus because the aim of teaching was developed in the direction of demonstrating software options to the pupils. This was captured by the Didaktik framework, which identifies the relation between the content and the subject matter. The software emerged as the content and the possibilities and/or limitations of opening up the subject matter and the educative substance were placed in the interaction between the pupils and the knowledge built into the software.

The results suggest that teachers’ choices of subject matter were never on the agenda in the pilot-group meetings; instead the focus pointed in the direction of discussing choices of software. The analysis shows that the discussions in the pilot group indicated a lack of discussion of the subject matter as well as aims regarding how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils. In the teaching in this study, the software was enacted as the content. The findings here also imply that the teachers used their pedagogical freedom to transfer the subject matter to the design and knowledge built into the software, with its possibilities or limitations. Consequently, the way the teachers demonstrated the software in classroom teaching could be seen as a shift to direct ICT use, i.e. the interaction between the pupils and the software.

From an educational perspective in the tradition of Didaktik, one question that should be on teachers’ agenda is to begin with a prospective object of learning and to ask what it can and should signify to the pupils, and how pupils themselves can experience this significance (Künzli & Horton-Kriiger, Citation2000). The teachers in this study repeatedly chose to enact the software as the content under the given circumstances instead of asking the traditional didactical questions of what content to select as well, as why and how, in relation to the digital technologies at hand (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007).

In understanding the findings here, the question of how the subject matter and the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils in their individual meeting with the content in the given teaching process (Hopmann, Citation2007) has to be taken into consideration. The data analysis captured the relation between the content and the subject matter but also revealed the fact that the subject matter was never on the agenda during the pilot-group meetings nor in the classroom.

The teachers’ discussions showed rather the complexity of teaching with ICT. Previous research highlights the didactic relation with ICT and the importance of teachers’ awareness about the purpose of integrating digital resources to enhance pupils’ learning within and across subject domains (Engeness, Citation2020; Hudson, Citation2007; Loveless, Citation2007, Citation2011). Moreover, previous research has shown that teachers’ close assistance at the beginning of the lesson seems to help the learners to develop their understanding about how to engage with the task and to reveal the potential of the resources useful for solving the task (Engeness, Citation2020). The teachers in this study gave whole-class demonstrations of software rather than demonstrating the design and knowledge built into the software in relation to the subject matter. The interactions were mainly between the pupils and the software (Öman & Svensson, Citation2015).

From this analysis follows the question of why the teachers chose to use their pedagogical freedom as they did and chose not to focus upon the subject matter and the idea of what pupils should learn. From the pupils’ perspective, the educative meaning emerges when the content is enacted in a classroom based on the methodological decisions of a teacher, which is a part of the teacher’s pedagogical freedom (Hopmann, Citation2007). One answer might be found in the rhetoric of the national ICT policy documents, which point out the potential of ICT to innovate in education and the idea of organizing school knowledge in terms of competencies (Sivesind & Wahlström, Citation2016; Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011). The findings here indicate that the teachers have been influenced to use their pedagogical freedom in the direction of ICT as a catalyst for a change in education. In doing so, the teachers tried to find operational ways of teaching from the vague curriculum guidelines of how ICT should be integrated in relation to the subject domains (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, Citation2017). One example is the comment from the principal: ‘start with the syllabus goals but use ICT’, which left no space for knowing in what way ICT could be a resource in education. Consequently, the emphasis on using ICT in classroom teaching overshadowed teachers’ considerations of how the subject content could be made relevant in relation to ICT and in relation to pupils’ potential and their previous experiences (Bachmann, Citation2005).

The findings also indicate teachers’ expectations for ICT to be a catalyst for change in their professional roles. The comment from one of the teachers: ‘I become more of a coach … ’ (Alana) shows that teaching is rather understood as the facilitation of learning (Biesta, Citation2013) and could also be connected to the rhetoric that surrounds the use of ICT (Haugsbakk & Nordkvelle, Citation2007).

The findings from this empirical study could open the way for a discussion about teachers’ professional knowledge and the didactic relation with ICT in various teaching situations. National reports suggest that teachers encounter challenges in the classroom practice and that teachers still have a need for better ICT competences (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2016), which could also be traced in the data presented in this paper, where there is a recurring discussion of the teacher’s new role and an expressed desire to have more training in ICT skills in order to fulfil the ‘new’ expected role. Therefore, the aim of teaching was developed in the direction of demonstrating software to the pupils and consequently, the possibilities and/or limitations of opening up the subject matter and the educative substance were placed in the interaction between the pupils and the knowledge built into the software. In this context, a critical question may be raised as to whether teaching should continue in a direction of developing teachers’ ICT skills instead of developing teachers’ didactical competences in relation to ICT.

Conclusions

The findings presented here point out a shift in the direction of teachers’ integration of ICT, i.e. how they employ their professional competence and to what extent they design appropriate learning tasks in a primary school practice. The teachers in this study found operational ways to achieve the goals of local and national policy documents. In this study, the software emerged as the content, and the ways in which the subject matter and the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils were left to the pupils’ interaction with the mediating software.

The teachers in the study were fully concentrated on finding various ways of using software features in order to develop the necessary skills, which created a distance in the didactic relation between the ‘what, how and why’ of the content of subject domains and the digital technologies available to teachers (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2007). One conclusion might be that, in different ways, it may have become more difficult to govern the content of the teaching by the use of ICT in education.

Based on the above, I argue, in the tradition of Didaktik, that the transformation of educational skills should move in the direction of ICT as a resource in education in connection with the didactical questions of what content, why this content is chosen and how it is enacted in the classroom, in relation to the choice of the matter itself and how the educative substance could be opened up for the pupils. It is also necessary to question the added value of ICT in classroom teaching.

The way in which the teachers in the study chose to use their pedagogical freedom, in relation to the integration of ICT in the primary-school classroom, raises an important issue regarding the importance of highlighting teachers’ professional Didaktik competences in relation to ICT instead of moving towards the development of other ICT influences in schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anne Kjellsdotter

Anne Kjellsdotter research interests concern the use of digital technologies with a focus on didactical questions within classroom practices. Her wider research interests include the impact of the social and cultural relationship between pupils and teachers’ orchestration of ICT, and the institutional conditions in operation.

Notes

1. Previous findings indicate that the interplay in the small groups between the group members and the software seems to be critical in the development of the pupils’ understanding of ICT resources as well as their understanding of the subject content (Öman & Svensson, Citation2015).

References

- Bachmann, K. E. (2005). Læreplanens differens. Formidling av læreplanen til skolepraksis. NTNU, Fakultet for samfunnsvitenskap og teknologiledelse, Pedagogisk institutt.

- Bengtsson, J. (1997). Didaktiska dimensioner. Pedagogisk Forskning, 2(4), 241–261.

- Biesta, G. (2013). Receiving the gift of teaching: From ‘learning from ‘to ‘being taught by’. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32(5), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-012-9312-9

- Björkvall, A. (2014). Practices of visual communication in a primary school classroom: Digital image collection as a potential semiotic mode. Classroom Discourse, 5(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2013.859845

- Edwards, A. (2015). Designing tasks which engage learners with knowledge. In I. Thompson (Ed.), Designing tasks in secondary education: Enhancing subject understanding and student engagement (pp. 13–27). Routledge.

- Edwards-Groves, C. J. (2011). The multimodal writing process: Changing practices in contemporary classrooms. Language and Education, 25(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2010.523468

- Engeness, I. (2020). Teacher facilitating of group learning in science with digital technology and insights into students’ agency in learning to learn. Research in science & technological education, 38(1), 42–62. doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2019.1576604

- Flewitt, R., Messer, D., & Kucirkova, N. (2015). New directions for early literacy in a digital age: The iPad. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(3), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414533560

- Friesen, N. (2018). Continuing the dialogue: Curriculum, Didaktik and theories of knowledge. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(6), 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1537377

- Genlott, A., & Grönlund, Å. (2013). Improving literacy skills through learning reading by writing: The iWTR method presented and tested. Computers & Education, 67(9), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.03.007

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Haugsbakk, G., & Nordkvelle, Y. (2007). The rhetoric of ICT and the new language of learning: A critical analysis of the use of ICT in the curricular field. European Educational Research Journal, 6(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.1.1

- Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research: Analysing social interaction in everyday life. SAGE.

- Hennessy, S., Ruthven, K., & Brindley, S. (2005). Teacher perspectives on integrating ICT into subject teaching: Commitment, constraints, caution, and change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(2), 155–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000276961

- Hennessy, S., Wishart, J., Whitelock, D., Deaney, R., Brawn, R., La Velle, L., McFarlane, A., Ruthven, K., & Winterbottom, M. (2007). Pedagogical approaches for technology-integrated science teaching. Computers & Education, 48(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.02.004

- Hillman, T., & Säljö, R. (2016). Learning, knowing and opportunities for participation: Technologies and communicative practices. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(2), 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1167080

- Holmberg, J., Fransson, G., & Fors, U. (2018). Teachers’ pedagogical reasoning and reframing of practice in digital contexts. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-09-2017-0084

- Hopmann, S. (1999). The curriculum as a standard of public education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 18(1–2), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005139405296

- Hopmann, S. (2007). Restrained teaching: The common core of Didaktik. European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109

- Hopmann, S. T. (2003). On the evaluation of curriculum reforms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270305520

- Hudson, B. (2007). Comparing different traditions of teaching and learning: What can we learn about teaching and learning? European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.135

- Jewitt, C. (2014). Different approaches to multimodality. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 28–39). Routledge.

- John, P. (2005). The sacred and the profane: Subject sub‐culture, pedagogical practice and teachers’ perceptions of the classroom uses of ICT. Educational Review, 57(4), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910500279577

- Kansanen, P. (2002). Didactics and its relation to educational psychology: Problems in translating a key concept across research communities. International Review of Education, 48(6), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021388816547

- Kervin, L., Danby, S., & Mantei, J. (2019). A cautionary tale: Digital resources in literacy classrooms. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(4), 443–456. http://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1620769

- Kjellsdotter, A. (2017). From earth to space—Advertising films created in a computer-based primary school task. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1419419. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1419419

- Klafki, W. (1995). Didactic analysis as the core of preparation of instruction (Didaktische Analyse als Kern der Unterrichtsvorbereitung). Journal of Curriculum Studies, 27(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027950270103

- Klafki, W., & MacPherson, R. (2000). The significance of classical theories of bildung for a contemporary concept of Allgemeinbildung. In Westbury, I., Hopmann, S. & Riquarts, K. (Eds.),Teaching as a reflective practice: the German Didaktik tradition. (Vol. 2000, pp. 85–107). Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Künzli, R. (1998). The common frame and places of Didaktik. In Gundem, B.B. & Hopmann S. (Eds.), Didaktik and/or curriculum. An international dialogue (Vol. 1998, pp. 29–45). Lang.

- Künzli, R., & Horton-Kriiger, G. (2000). German Didaktik: Models of re-presentation, of intercourse, and of experience. In Westbury, I., Hopmann, S. & Riquarts, K. (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice: the German Didaktik tradition. (Vol. 2000, pp. 41–54). Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Loveless, A. (2007). Preparing to teach with ICT: Subject knowledge, Didaktik and improvisation. The Curriculum Journal, 18(4), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170701687951

- Loveless, A. (2011). Technology, pedagogy and education: Reflections on the accomplishment of what teachers know, do and believe in a digital age. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 20(3), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2011.610931

- Loveless, A. M. (2003). The interaction between primary teachers’ perceptions of ICT and their pedagogy. Education and Information Technologies, 8(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EAIT.0000008674.76243.8f

- Nikolopoulou, K., & Gialamas, V. (2015). Barriers to the integration of computers in early childhood settings: Teachers’ perceptions. Education and Information Technologies, 20(2), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9281-9

- Nilsen, M., Lundin, M., Wallerstedt, C., & Pramling, N. (2018). Evolving and re-mediated activities when preschool children play analogue and digital Memory games. Early Years, 33(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2018.1460803

- Nordkvelle, Y. (2004). Technology and didactics: Historical mediations of a relation. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(4), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000159476

- Oliver, M. (2011). Technological determinism in educational technology research: Some alternative ways of thinking about the relationship between learning and technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(5), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00406.x

- Öman, A., & Sofkova Hashemi, S. (2015). Design and redesign of a multimodal classroom task–Implications for teaching and learning. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 14(1), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.28945/2127

- Öman, A., & Svensson, L. (2015). Similar products different processes: Exploring the orchestration of digital resources in a primary school project. Computers & Education, 81(2), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.011

- Player-Koro, C., Bergviken Rensfeldt, A., & Selwyn, N. (2017). Selling tech to teachers: Education trade shows as policy events. Journal of Education Policy, 33(5), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1380232

- Prieto, L. P., Dlab, M. H., Gutiérrez, I., Abdulwahed, M., & Balid, W. (2011). Orchestrating technology enhanced learning: A literature review and a conceptual framework. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 3(6), 583. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2011.045449

- Selwyn, N. (2016). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Selwyn, N., & Facer, K. (Eds.) (2013). Introduction: The need for a politics of education and technology. In The politics of education and technology (pp. 1–17). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Selwyn, N., Nemorin, S., & Johnson, N. (2017). High-tech, hard work: An investigation of teachers’ work in the digital age. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(4), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1252770

- Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Sivesind, K. (2013). Mixed images and merging semantics in European curricula. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2012.757807

- Sivesind, K., & Wahlström, N. (2016). Curriculum on the European policy agenda: Global transitions and learning outcomes from transnational and national points of view. European Educational Research Journal, 15(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116647060

- Stenliden, L., Nissen, J., & Bodén, U. (2017). Innovative didactic designs: Visual analytics and visual literacy in school. Journal of Visual Literacy, 36(3–4), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2017.1404800

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). National curriculum and syllabus. Fritzes.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2013). IT use and IT-competences in Swedish schools. Fritzes.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Report on the assignment to propose national IT strategies for the school system Dnr U2015/04666/S.Fritzes.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2017). National curriculum and syllabus. Fritzes.

- Tay, L. Y., Lim, S. K., Lim, C. P., & Koh, J. H. L. (2012). Pedagogical approaches for ICT integration into primary school English and mathematics: A Singapore case study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.838

- Voogt, J., & Roblin, N. P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st century competences: Implications for national curriculum policies. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2012.668938

- Walford, G. (Ed.). (2008). How to do educational ethnography. Tufnell Press.

- Watson, G. (2001). Models of information technology teacher professional development that engage with teachers’ hearts and minds. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, 10(1–2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759390100200110

- Wegerif, R. (2010). Dialogue and teaching thinking with technology. In Littleton, K. & Howe, C. (Eds.)Educational Dialogues: Understanding and Promoting Productive Interaction, (Vol. 2010 pp. 306–318)..London: Routledge.

- Willbergh, I. (2015). The problems of ‘competence’ and alternatives from the scandinavian perspective of bildung. Journal Of Curriculum Studies, 47(3), 334–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.1002112

- Wolfinger, N. H. (2002). On writing field notes: Collection strategies and background expectancies. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794102002001640