ABSTRACT

The general thesis of this article is that ‘nation’ and ‘state’ are often understood as almost equivalent and that this understanding has led to aberrations in educational research, not only with regard to citizenship but also with regard to questions of modernity, claims of globalization, visions of a coming world culture, or even the proclamation of the end of history. The assumed equivalence expresses a particular discourse that traps reflections and research alike, and this discourse is borne by those nation-states that have profited the most from the coupling of the idea of the nation with the idea of the state―that is, foremost, England, Germany, France, and the United States. Two related shortcomings are identified: the large underestimation of nationalism in education and curriculum research and the ignorance of education in the theoretical study of nationalism. The more precise thesis of this article is that we will never understand nationalism in all its layers if we exclude education from the study of nationalism, and that we will never understand modern education if we exclude nationalism in the emergence of the modern nation-states.

Introduction

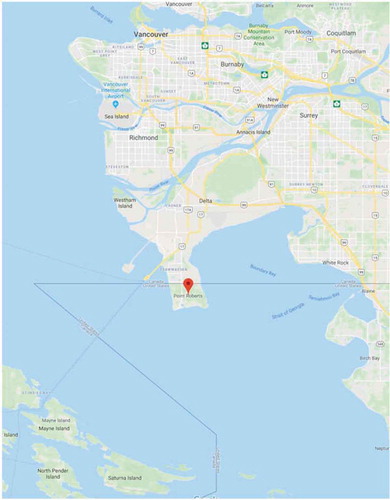

Point Roberts, Washington is a U.S.-American communityFootnote1 with approximately 1,300 residents living in an area of less than five square miles (see ). It has no local administration but a post office, a community jail, a Lutheran Church, a history centre, a kindergarten, and a primary school for first and second grade and, depending on funding, sometimes also third grade. From the third or the fourth grade on, Point Roberts’ children―currently some 25 in number―take a one-hour school bus ride to an upper primary school and high school in a community called Blaine.Footnote2

This situation might be not seen as extremely exceptional, if there were not alternatives much closer to Point Roberts. The reason why Point Roberts’ youngsters have to take on the burden of travelling an hour twice each day is their geopolitical location at the very end of a peninsula some 22 miles south of Vancouver in British Columbia, Canada. Their closest upper primary school and high school options would be in Tsawwassen, a town less than 10 minutes away by car or some 15 minutes by bike―but this town is located in Canada, where Point Roberts’ students would, as international students, have to pay some 15,000 CAD in school fees a year. The nearest U.S. school would be only 13 miles away as the crow flies, but unfortunately there is no ferry, so it can only be reached by bus, which has to travel a bit more than 25 miles—across Canada. The students have to cross two borders to get to the school, first the Canadian and then the U.S. border, and the other way around on their way back.

The monetary aspect―the 15,000 CAD school fees a year―is certainly an important reason for Point Roberts authorities and parents to encumber their children with a two-hour bus ride every day. Other reasons are that, at a Canadian school, Point Roberts’ U.S.-American children would have to get used to slightly different spelling than the spelling in the United States; they would also learn, for instance, that the proper name of a wild goose is an outarde; and, unlike most United States’ residents, Canadians actually do refer to different educational institutions when they use the terms ‘college’ versus ‘university’. Presumably, however, these differences would be deemed less important than the fact that the students would learn about a different form of political government, taught with pride, and would become acquainted with Canada’s bilingualism: In Grade 10, Canadian ‘students are expected to know … government, First Peoples governance, political institutions … Canadian autonomy, [and] Canadian identities’ (British Columbia Ministry of Education [BCMOE], Citation2019a). In Grade 11, they would be exposed to ‘Francophone History and Culture’ BCMOE, Citation2019b), and in Grade 12 to ‘Comparative Cultures’ or ‘[BC] First Peoples’ BCMOE, Citation2019c). All in all, they might be pleased to have no more than 172 school days a year (Sailor, Citation2017), but they would be singing Canadian songs, getting acquainted with Canadian culture, and learning Canadian geography and Canadian history.

Hence, like their fellow fates in the United States, they would learn that since the London Convention of 1818, the 49th parallel north between the Great Lakes and the Rocky Mountains has demarcated the United States from British Canada, but in addition they would learn that this border had been called the ‘Medicine Line’ by First Peoples because they believed that magic medicine stopped U.S. soldiers from prosecuting and killing them north of that line. The students would also learn that, in 1846, this demarcation line was expanded to the Pacific Ocean as a compromise between the United States’ ambition to claim the whole west coast way up to Russian Alaska (‘Fifty-four forty or fight!’) and the British claim to incorporate the territory along the Columbia River; the result was the Oregon Treaty, excluding Victoria Island from this demarcation. In a contemporary Canadian textbook, this compromise to end the boundary dispute is depicted as perhaps too weak a measure against American imperialism:

like the rest of British North America, British Columbia had a fraught relationship with the United States. The boundary with the American territories to the south was established in 1846, but the fear remained that American gold-seekers were probing for weaknesses and opportunities to see the BC mainland annexed to the American republic. (Belshaw, Citation2016, p. 36)

In addition, to stay in this context, the students would learn that it was this U.S.-American expansionism that is the cause of their very personal situation, for the Oregon Treaty had left out the question of how to territorialize the San Juan Islands between the mainland and Victoria Island. This dispute lead to the Pig War in 1859, a war that only cost the life of one pig and that was solved in favour of the United States’ interests, incorporating the whole San Juan Islands into the United States and, as a consequence, drawing the 49th parallel further west, right up to the shores of Victoria Island. This resulted in the cutting of a tiny southern end of a Canadian peninsula south of Vancouver and assigning this spot, named Point Roberts, to the United States, the home country of these students. This is what forces them to either travel two hours by bus every day or attend a nearby fee-based Canadian school, with its curriculumFootnote3 as machinery for fabricating the minds of Canadian citizens, and, in turn, as Point Roberts’ author and historian Mark Swenson emphasized in an interview,Footnote4 students would learn hardly anything about U.S. history in general, and nothing about the Civil War in particular.

Outlining the problem between citizenship, education, the nation, and the state

The perception that modern schooling is designed to fabricate future citizens has become a truism in international curriculum studies. As early as in 1902, Robert E. Hughes, in his book The Making of Citizens: A Study in Comparative Education, emphasized that ‘every school is a machine deliberately contrived for the manufacture of citizens’ serving the ‘progress of the State’ (Hughes, Citation1902, pp. 4, 338). But at that time, and up to today, it seems that there has been confusion between the concept of the state and the concept of the nation. We can see this, for instance, in another popular comparative education book by Andy Green in 1990, where Green, as the title indicates, examines Education and State Formation (Green, Citation1990) but then focuses in his study solely on nations, national education systems, or nationhood.

This peculiar interchangeability of ‘nation’ and ‘state’ and the associated perfectly obvious interest in education probably results from the fact that, for a very long time, only scholars in very powerful nation-states―that is the correct way to name them―cared about the interrelation between education and nation-state building―namely, scholars in England, Germany, France, and the United States, and as a rule they looked at exactly these four countries, as Hughes did in 1902 and Green in 1990. Hence, the misleading equation of ‘nation’ and ‘state’ itself results from nationalist perceptions that the respective self-confident states are the ultimate expression of the most laudable nation and vice versa. And this is why the world’s most encompassing organization, the United Nations Organization, is in fact a misnomer. The UN does not assemble the different nations of the world―otherwise the Kurds, the Sami, or the Palestinians (Palestine at least has the status of being an observer) and many others would be official members―but rather states, nation-states. The proper name of this organization would have been the United States Organization (USO), but since 1941 USO has been used as an acronym for United Service Organizations Inc., a non-profit patriotic corporation that has provided live entertainment (one of the stars was Bob Hope and another Marilyn Monroe, for instance) to uniformed members of the United States Armed Forces, USO was not available.

The misleading equivalence between the state and the nation has―and this is the general thesis of this article―misled large parts of research in education not only with regard to citizenship but also with regard to questions of modernity, claims of globalization, visions of a coming world culture, or even the proclamation of the end of history. It expresses a particular discourse that traps reflections and research alike, and this discourse is borne by those nation-states that have profited the most from the coupling of the idea of the nation with the idea of the state―that is, again, England, Germany, France, and the United States. And it has affected both research focusing on education and citizenship and research trying to understand the nation as a cultural fact apart from the state. In particular, I identify two phenomena of shortcomings that both express the discursive trap and reinforce it―namely, the large underestimation of nationalism in education and curriculum research and the ignorance of education in the theoretical study of nationalism. The more precise thesis of this article is that we will never understand nationalism in all its layers if we exclude education from the study of nationalism and that we will never understand modern education if we exclude nationalism in the emergence of the modern nation-states.

The aim of the article is to sort out ideologies, driving forces, epistemologies, and schooling; to clarify concepts, especially in terms of their historical change, in order to make sense of the thesis with regard to the overall question of what brings and holds nation-states together beyond the sheer power of laws (Wimmer, Citation2018); and to clarify what the role of education, schooling, and curriculum is in this cohesion. This endeavour will not culminate in empirical evidence supporting the thesis but in making its relevance evident. At the end, there will be no data-based case studies but a research agenda that allows the conducting of larger international research projects. This issue will be addressed by arguing that―taking the example of Point Roberts―the problem is not so much that the students from the United States would be exposed to a machinery fabricating Canadian citizens but most of all to a machinery fabricating Canadian citizens, a kind of constitutionally-defined legal person characterized by a set of attitudes, practices, and values that are, in the end, national and thus distinct from others. This is a result of the amalgam of in fact two very different ideas, the nation and the state, that develop their thorough and sometimes explosive power only in their mutual, synergetic relationship as nation-state.

In order to do so, this article will continue in five steps. First, the two shortcomings in the study of nationalism and in curriculum research indicated above will be identified and analysed in order to subsequently clarify the concepts of nation, nationalism, and statehood and then the concepts of citizenship and society. This will allow me, in the last section, to draw a rough outline of a research approach that matches the title of this article, National literacies, or modern education and the art of fabricating national minds.

The first shortcoming in the study of nationalism: theories of nationalism

It goes without saying that the picture drawn in the following is a rather rough simplification, and in this sense it does injustice to exceptions that certainly exist. In addition, it has to be mentioned that, here, nationalism does not refer to the tangible extremist or aggressive ideologies often depicted in public media but more to what Billig (Citation1995) called ‘banal nationalism’ in his book of the same name―that is, everyday representations of the nation(-state) that build a common sense of national belonging among people. These are everyday practices of identity formation and geopolitics, which are unobtrusive and unrecognizable because of their everyday nature. They are therefore particularly powerful and effective, and in times of crises, they are the very basis of aggressive nationalism, which is not at stake, here, however.

One shortcoming in the study of nationalism is to be found in those studies explicitly devoted to the theory of nation or nationalism.Footnote5 The theory’s major exponents―Benedict Anderson, Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm, Walker Connor, John Breuilly, or Anthony D. Smith―are either British, Irish, or American scholars in the political sciences, history, sociology, philosophy, or social anthropology. With the exception of Gellner, most of them either ignore education or refer to it in a rather marginal way. Gellner (Citation1983), in turn, indeed claims the importance of education in the process of industrialization as an engine of modernization and nationalism that has brought a demand for standardized skills to be developed by centrally controlled systems of education (p. 54). Smith (Citation1991) confirms Gellner’s emphasis that education ‘is as much a consequence as a cause of nationalist ideology and consciousness’ (p. 192) and highlights, in addition to Gellner’s more instrumental view on primary education, the aspect of ‘civic education’ as the expression of a secular curriculum which is the ‘most significant feature of territorial nationalism and the identity it seeks to create’ (p. 118).

In an effort to examine the phenomena of the nation or of nationalism, Atsuko Ichijo and Gordana Uzelac invited prominent exponents (John Breuilly, Walker Connor, Steven Grosby, Eric Hobsbawm, Anthony D. Smith, and Pierre L. van den Berghe) of the three ‘schools’ of the study of nationalism―primordialism, modernism, and ethno-symbolism―to discuss the seminal question ‘When is the nation?’ (Ichijo & Uzelac, Citation2005). This question had been raised by Walker Connor in 1990 in trying to find an alternative to the hardly answerable but popular essentialist question ‘What is a nation?’ The alternative was historical, as Connor had asked ‘At what point in its development does a nation come into being?’ (Connor, Citation1990, p. 99). In his attempt, Connor had been motivated by the seminal book by Eugene Weber, Peasants into Frenchman (Weber, Citation1976), according to which many of the ordinary French people were not even aware of their being French even as late as the First World War, and the idea of France as a comparatively old nation―1789―was thus problematic.

The question that Weber and Connor ask has a lot to do with education, for how people learn what they are supposed to be with regard to nationhood is an educational question. Weber, indeed, had addressed this question in a marvellous chapter on French schooling (Weber, Citation1976, pp. 303–338), but surprisingly enough, Connor did not engage with this question at all. This might have been the reason why Ichijo and Uzelac (Citation2005), who took up Connor’s ‘When is a nation?’, raised exactly this question among others in their collaborative volume mentioned above, When is the Nation? Towards an Understanding of Theories of Nationalism. The result, however, is sobering if not disappointing.

The question posed to Hobsbawm, Breuilly, and Smith was: ‘What sort of educational impact do the topics of nation, nationhood and nationalism have?’ (Ichijo & Uzelac, Citation2005, p. 129). Hobsbawm answered that the education systems have been too ‘deeply imbued with nationalism’ and that the ‘main problem is precisely how we can emancipate education and higher education from this built-in nationalist virus’ (p. 130). Breuilly is ‘pessimistic’ and laments that this question was under-explored because ‘school education has become so complex’ (p. 130). In any case, history as a school subject needs to be subverted in its nationalist stance, and the question remains, according to Breuilly, whether the ‘good end’ of schooling is to have a good (for instance, multicultural) end or none at all (p. 130). Smith claims that education had been a victim of nationalism ‘to the detriment of dispassionate analysis, and has thereby encouraged one-sided and exclusive attitudes’ (pp. 130–131) and adds that ‘the study of nations and nationalism can serve a useful corrective function—both to nationalist one-sided bias, and to naïve and idealistic cosmopolitanism’, even if Smith doubts that the school can ever meet these expectations (p. 131).

What can be seen here is how little is known about schooling and that school education is being seen as a thoroughly moral issue. Education is a victim of nationalism and deserves to be emancipated (Hobsbawm) or subverted (Breuilly), possibly by studying nationalism, whereby it is doubted that the school can take on this task at all. Although from the point of view of education or curriculum research, we could but should not accuse these nationalism researchers of knowing too little about school or school education. Instead, we should look where education research, which is all too often saturated with moralism, has been lacking. That leads to the second shortcoming.

The second shortcoming in the study of nationalism: education and curriculum studies

There is no need to mention specifically that education as a social practice is a highly moral issue. Whenever people have made an effort to educate or teach, it has most often been for a moral purpose. Since the early Enlightenment, a less significant part of these efforts has indeed been to enable the next generation to participate in the economic and social processes and progress and, for the elites, in political developments. A more significant part of these educational measures, however, was to tame the real or even feared consequences of these economic or social developments. The normative background of these educational interventions was, as a rule, shaped by religious ideas, especially in Protestantism, which by virtue of its own theology could, much more than Catholicism, focus on softening or taming the heart or soul of the person exposed to this changing world (Tröhler, Citation2020).

In a long process, the theological and ecclesial background of these educational interventions was transferred bit by bit to the state, which represents the breeding ground of the modern mass school system. This process, often labelled as secularization, is assumed to encompass far more than only institutional changes and to also include mental or cultural aspects of life: It culminates in the rational modern citizen being emancipated from superstition, prejudice, and faith. This assumption has been challenged by recent research emphasizing if not the ecclesial at least still the religious background of educational reasoning (Buchardt, Citation2015; Tröhler, Citation2011). In addition, we are becoming more aware that, in the course of the 18th century, it was not simply a rational state detached from the church that emerged: Many intellectuals felt that the state had a need for something that CitationRousseau ([1762] 2002), in The Social Contract, called civil religion, indicating the state’s need for a ‘civil profession of faith’ expressing ‘sentiments of sociability, without which it is impossible to be a good citizen or a faithful subject’ (pp. 252–253). This is where the nation comes in. The French Revolution, for the first time, combined the nation, in its cohesive power, with the power structure of the (constitutional) state. When the first French Constitution, adopted in 1791, declared the French king the ‘King of the French’ (and not by the grace of God) (Title 3, Chapter II, para. 2), who, on his accession to the throne, ‘shall swear an oath to the nation to be faithful to the nation’ (Title 3, Chapter II, para. 4). Thus it became clear that the principle of statehood was intensively connected to the principle of the nation. In this way, the principle of the nation was seen to be the overall cohesive cultural power of the new constitutional monarchy and to be in need of constant renewal, which is a popular education measure: ‘National festivals shall be instituted to preserve the memory of the French Revolution, to maintain fraternity among the citizens, and to bind them to the Constitution, the Patrie, and the laws’ (Title 1).

The educational consequences of combining educational questions with the nation-state were well-known over a hundred years ago, even if the distinction between the nation and the state were unclear. One of the first comparatists in education, the British historian Michael Sadler, wrote: ‘A national system of education is a living thing, the outcome of forgotten struggles and difficulties and “of battles long ago”. It has in it some of the secret workings of national life’ (Sadler, Citation1900, p. 11). Sadler wrote this in 1900 in the knowledge that half the world was looking to Prussia, which had meticulously organized and expanded its school system. Sadler’s emphasis is a national warning notice in favour of the British school system in the same way that Robert Hughes remarked two years later that ‘the discipline of the German school is admirable, so is the general system of training—for German children; yet there can be no doubt that such a system would be the very worst for English or American children’ (Hughes, Citation1902, p. 11). The same could be said of Horace Mann’s report on the German education system much earlier in the 19th century.

Certainly, education research has come to recognize the extent to which curricula are designed to fabricate the future citizens (Kim, Citation2018; Popkewitz, Citation2004), but it has extremely rarely realized that ‘citizen’ should always be seen as a floating signifier, as a concept that is materialized very differently in the different cultural contexts of the nation-states (Tröhler, Citation2016). Hence, we should not talk about citizens but about national citizens, or nationally-minded citizens. And, to come back to the initial story, a national Canadian mind is different from a U.S.-American mind, from a French one, a German one, and all the other ones. How little this has been recognized in curriculum theoryFootnote6 can be demonstrated by the two large contemporary handbooks in curriculum research, the SAGE Handbook of Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Assessment, issued in 2015, and the SAGE Handbook of Curriculum and Instruction, issued in 2007; both books comprise approximately 1,800 pages. The certainly not very elaborated test is to see whether the keyword ‘nationalism’ is listed in the index. What we find is that, in both publications altogether, there are 61 keywords that are connected to the notion of the nation but none to the phenomenon of nationalism. In all those 61 keywords, such as National Association of Secondary School or National Curriculum, the nation is taken for granted and is not problematized and up for discussion.

If in education or curriculum research the topic of nationalism is indeed mentioned, as a rule, it is addressed as aggressive and not as banal nationalism. It is thus likely constructed as something moral, as something to be worried about, and the ‘disruptive impact of nationalism on citizenship education’ is demonstrated (Siebers, Citation2019). It is something to combat through tolerance education or intercultural education or subversive actions (Lugg, Citation2017). This brings us back to the moralizing character of educational reasoning but not to the excavation of the foundations of modern education thinking and of modern education organizations in the context of nation-building.

Nation, nationalism, and statehood

As mentioned above, in the context of modernity it is necessary to talk about nation-states, which raises the question of how this coalescence between the nation and the state came about in such a way that, today, the distinction is hardly recognizable anymore. The answer must take into account two different transformations that took place around 1800 and that allowed ‘state’ and ‘nation’ to be thought of together, creating something of a win-win situation from which both ‘nation’ and ‘state’ benefited. One aspect was the transformation of the concept of the nation in the face of growing nationalism as a discourse, and the other aspect was the justification of state power in the face of theories of natural rights and ideas of the social contract.

Within the research on nation or on nationalism, there is an ongoing discussion about the relation between them. One of the crucial questions is: Which one proceeds or which one results from the other? Most scholars in the field would agree that the concept of the ‘nation’ is, if not perennial, old, much older than the phenomena labelled as ‘nationalism’. Whereas a minority of scholars argue that there is a continuing line of this idea since almost the dawn of mankind up to our times, the majority argues that in the 18th century this concept of the nation underwent a process of politicization by virtue of the ideology or discourse of nationalism. They argue that rising nationalism defined the nation(s) much more accurately than ever before and made the concept thereby reflective, discussable, and debatable. In this respect, Calhoun (Citation1997) defines nationalism as a ‘discursive formation’ or ‘a way of speaking that shapes our consciousness’ (p. 3). In that sense, nations, in our modern understanding, come to consciously exist within the discursive context of nationalism: ‘Nation’ is then a politically relevant ‘particular way of thinking about what it means to be a people’ (p. 99).

Hence, ‘nation’ is a cultural thesis about collective identity that becomes intellectually tangible in the moment that nationalism as ideology performs this nation as nation; it is seen as ‘discourse’, as ‘a particular way of seeing and interpreting the world, a frame of reference that helps us make sense of and structure the reality that surrounds us’ (Özkirimli, Citation2010, p. 206). Nationalism thereby tends to naturalize itself and hide itself in everyday practices that are taken for granted (Özkirimli, Citation2010, pp. 210–217); it becomes, in this aspect, banal (Billig, Citation1995). Also, since nationalism as a discursive formation arose precisely in the time of what is called secularization, it is in that sense thoroughly political and gives the concept of the nation a political fundament. The ‘nation’ becomes a field of ambition, of power struggles, as Verdery (Citation1993) emphasized when she suggested understanding ‘nation’ as a symbol with multiple meanings, ‘competed over by different groups maneuvering to capture [its] definition and its legitimating effects’ (p. 39). This politicization of the ‘nation’ makes it compatible with the state, for it is the state that can implement and maintain powerful institutions to perpetuate the dominant interpretations of the nation by approximating people to its normative ideas. It can erect, support, and celebrate national symbols, and it can implement school systems in which students are being aligned to the nation’s genius. Yet that is only one side of the story, for the modern state itself was very much in need of ties that bind, of dominating cultural theses of identity.

One thing the Enlightenment had brought about was the idea of natural freedom, of equality, of inalienable rights, and of a social contract between formerly completely free and independent beings who are able to ask themselves what advantages they receive by living in social, coercive relationships. Normally, this idea of a free state of nature was understood as a heuristic tool to assess the normative quality of a state and the inequality of its inhabitants. This question had been raised by the Academy of Dijon prize competition in 1754, asking ‘What is the origin of inequality among people, and is it authorized by natural law?’ The most famous answer was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, even though he did not win the prize competition. Rousseau wrote that the social inequality in contemporary France was not justifiable by nature and that the positive law, the real existing law, privileging a very small number of people, was in contradiction to natural law. For, as Rousseau concludes almost a half a century before the French Revolution, ‘it is evidently against the law of nature that children should command old men, and fools lead the wise, and that a handful should gorge themselves with superfluities, while the starving masses lack the barest of life’ (Rousseau, Citation[1755] 2002, p. 138)―the then acting king of France, Louis XV, had been enthroned in 1715 at the age of 5.

After 1789, the explosive effects of these kinds of thoughts were well-known, for people had indeed started to ask why they should pay taxes without having any political rights, why they worked extremely hard without enjoying any property or security, or why they had to give their lives in war for a king that they did not know. It is exactly here that the politicized nation comes in. Wrapped up and heated up by the discursive formation of nationalism, the nation became, politically, the anti-thesis of the natural rights theories and the idea of a social contract. The idea that the people actually form a national whole or a community obviously acts as the mitigator of the danger of critique, upheaval, or even revolution. Hence, the nationalized nation on the one side and the state potentially composed of unencumbered selves on the other side had good reasons to coalesce with each other and to form a nation-state.

One of the central means to implement this coalescence between the nation and the state was the adoption of a constitution. The constitution codifies the dominant visions regarding power distribution (here, we can easily detect different religious mentalities, as Catholic countries are, as a rule, much more centralized than Protestant ones) and regarding, in general, the social order of the national community. The constitution lies at the bottom of every other law regulating the life of the citizens, including, of course, the school laws that regulate schooling in general and curricula in particular in their purpose of fabricating the loyal minds of the future citizens.

Citizenship and society

The power of the cultural thesis embodied in the concept of the nation depended on loyal actors; you cannot simply kill all the sceptics and heretics, as was the attempt during the French Reign of Terror in 1793/94, when some 16,500 people were executed. The label of these loyal actors was the ‘citizen’, a notion that had been well-known in the previous centuries, as Maarten Prak (Citation2018) has shown in his fine, recent book, Citizens Without Nations: Urban Citizenship in Europe and the World, ca. 1000–1789. In contrast to the time before 1789, when citizenship had always been connected to the city (Latin civitas) and was therefore built on personal membership in political human associations that entailed expected standards of behaviour with regard to this membership (Prak, Citation2018, pp. 5–6), the French Revolution emancipated the concept from the cities and nationalized and, based on the constitution, generalized it to all male inhabitants of France.

Under Title II of the first French Constitution of 1791, mentioned above, the status of the French citizen was defined as follows:

The following are French citizens: Those born in France of a French father; Those who, born in France of a foreign father, have established their residence in the kingdom; Those who, born in a foreign country of a French father, have established themselves in France and have taken the civic oath; Finally, those who, born in a foreign country and are descended in any degree whatsoever from a French man or a French woman expatriated because of religion, have come to reside in France and have taken the civic oath. (para. 2)

What follows are explications that are not unfamiliar to us, but at the time they were brand new: They regulate the procedures and conditions of naturalization; the notion of ‘naturalization’ is used, indicating the equation of ‘nation’ and ‘nature’, serving as the anti-thesis of ideas of natural freedom. They define the oath, ‘I swear to be faithful to the nation, to the law, and to the King’ (in that order!), and among other things, define that ‘French citizenship is lost: 1st, by naturalization in a foreign country’ or ‘2nd, by condemnation to penalties which entail civic degradation, as long as the condemned person is not reinstated.’ (para. 6).

Making citizens feel as if they were a natural part of the constitutional nation-state (in France: first as a monarchy and a bit later as a republic) was the general educational task that the nationalization and generalization of the concept of citizenship entailed. It aimed at two very different kinds of loyalties. The one loyalty was, obviously, towards the ‘naturalness’ of national identity, but also of uniqueness and often also of superiority in contrast to other nations, and the other was loyalty towards social distinctions. To be sure, all constitutions declared in some way or another the equality of all its citizens, but only in equality ‘before the law’. Both the constitutions and the laws could privilege social groups, and they hardly prevented wealth accumulation or social distinctions.

In order to explain and justify the social distinctions within the field of legal equality and national unity, another term was transformed: the concept of society. Previous to 1800, ‘society’ (societé, Gesellschaft) had been used for social, intellectual, economic, or moral associations of urban citizens, but after 1800, the notion became, in parallel to the concept of the citizen, generalized and nationalized. It is probably no coincidence that the first person to use the modern notion of ‘society’ was the French intellectual, August Comte, in his seminal Plan de travaux scientifiques nécessaires pour réorganiser la société (Plan of scientific studies necessary for the reorganization of society), published in 1822. It was Comte who paved the way for an understanding of ‘society’ as a large social group sharing the same social territory, the national borders, and typically subject to the same political system or authority and to dominant cultural expectations. Ever since, ‘society’ has been nationally framed. Today, we talk about American society, German society, Swedish society, Japanese society, but we would never talk about the Idaho society or the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern society, but perhaps, exceptionally, about ‘New York society’ as a notion of the wealthy and fashionable.

Comte is normally considered to be the father of sociology, the study of society. Depending on the idea of the nation but in contrast to its harmonizing wholeness, sociology is designed to identify differences and correlations between social categories. However, as Ian Hacking (Citation1986) has observed, what seems to be a descriptive function is a mechanism of ‘making up people’ by statistical numbers and correlative hypotheses about type-specific patterns of behaviour and of providing a system of red flags that tell the state where it must intervene preventively. These statistical mechanisms helped state bureaucracies to strengthen their governmental power in implementing the cultural thesis of the nation, not least by the creation of normality and by that of deviance. For both cases, the state responded educationally. Those students with the potential and prospect of becoming normal citizens went through the regular school, and for all others, the state has implemented special needs schools with specially-trained teachers and their own curricula, and even with the promise of permeability between school types. Obviously, the nation state, depending on loyal citizens, is deeply educationalized, and the emerging educational sciences were set up to support this educationalization with academic knowledge and to give this educational practice and endeavour an appropriate reputation. It is here that we see how the epistemologies that were born out of the emergence of the academic disciplines were deeply national(ist) in their character, and it is exactly this mark of Cain makes it as blind today towards nationalism as its religious fundament has made it blind towards religion.

National literacies or modern education and the art of fabricating national minds

The turn from the 18th to the 19th centuries brought some fundamental changes in the way that people perceived the world and started to organize the world. These changes encompassed the transformation of central concepts such as the nation, the state, the citizen, and society, and they were all brought together in an extremely sustainable way, so that to this day there seems to be hardly any alternative, not politically or intellectually. The nation-state and its construction of the citizen and its society is taken for granted, as the research literature on curriculum issues shows, but it is also deeply educationalized, as theories on nations and nationalism have failed to realize more accurately.

However, these transformations have not produced a homogeneous world culture and are not the starting point of such a culture either, when it still builds on ideas of the nation and thus on the idea of cultural difference which have been materialized in the very fundaments of the modern state, the constitutions. What is common is faith in the combination of the nation and the power structure of the state, the creation of the citizen and the society and the educationalization of this project; but the intellectual and organizational machineries in fabricating the essential loyal citizens, loyal to both the nation and to social stratification, are very different. Long-standing traditions do still affect educational reasoning, planning, and organization in the different nation-states in several layers. The traditional weak engagement of England in education that fostered the elites’ preferences for private schooling also affected the organization of schooling in Canada and the United States, which in turn largely ignored thorough organization of vocational training. In contrast, the strong French reasoning of the state has resulted in the organizing of vocational training as a part of the state school system, quite contrary to the German-speaking realm, where vocational training was organized in close cooperation between professional associations, private companies, and the state. Another layer which affects the educationalized nation-states is religion. The fact that Protestant countries, with their religious sensitivity to equality, as a rule favour comprehensive K-12 public schools, whereas in contrast, Catholic countries, with their inherent sense of hierarchy, are more likely to select children for different ‘avenues’ at the ages of 12, 11, or even 10, as for instance, in Italy or Austria. Additionally, U.S.-Americans, with their identity building within high schools and colleges and their exhibitionist love for public glory and parades, organize marching bands and homecomings to welcome back alumni and former residents and elect a homecoming king and queen, which is all built around a central event, such as a banquet or dance and, most often, a game of American football, the most national sport of the United States.

All this now concerns only the formal and ritual side of the national school systems and their task of fabricating nationally-minded citizens, but it is indeed important for the children who are integrated in this factory, as are the various transitional arrangements between the formal elements of school education, their respective curricula in the different school types, levels, and tracks. This actually could take us back to Point Roberts, the U.S. exclave at the southern end of the Tsawwassen Peninsula, and not only because Canada’s national sport is in fact hockey and not football.

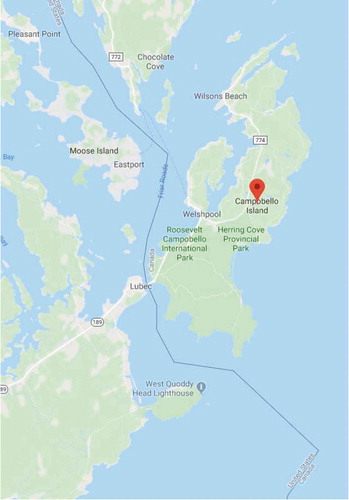

From a European point of view, the solution lies at hand. All agree that the situation of Point Roberts is difficult, and the solution could be to exchange land. For on the very eastern end of the North American continent, we find Campobello Island, an island in New Brunswick, Canada, three times the size of Point Roberts but with only slightly more than half the number of residents (see ). The island has no road connection to the rest of Canada; but it is connected by the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Bridge to nearby Lubec, Maine.

Why not exchange these territories and ease the life of their residents? Well, because they are more than only residents. They are citizens, national citizens, who have learned how worthy it is to be a member of this or that imagined community, labelled nation, organized by a state, no matter what the daily difficulties are. No interviews with Campobello Island residents were conducted for this article, but there is hardly any doubt that they would say the same thing as the interview partner in Point Roberts. Just as he insisted that he was (U.S.-)American, not Canadian, and that annexation of Point Roberts to Canada was unthinkable, so would the Canadians of Campobello Island most probably react to the proposal of annexing their island to the United States.

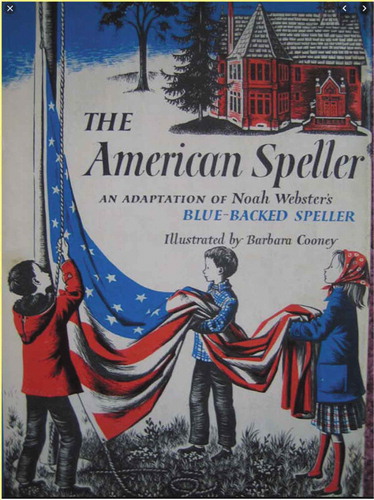

This adherence to the status quo, as irrational as it may seem from afar, is, among other ingredients, the effect of what can be called the fine art of modern education in fabricating national minds. Certainly, many governmental and cultural initiatives are constantly flagging the nation, to use Billig’s (Citation1995) convincing metaphor representing what he calls banal nationalism. Billig, however, like most of his colleagues engaged in understanding nationalism, underestimates the role that schooling plays in this making and maintaining of identity. Of course, the official United States Flag Code applies to schools as well; and the singing of the national anthem before football games in high schools, colleges, and in professional games has its effects; and of course curricular fields like history, geography, singing, or even biology, or nationalized arithmetic textbooks play an important role. Yet these practices and provided learning opportunities do not draw the whole picture. It is less about what someone has to learn to know and to be able to do, defined knowledge and skills, and it is not only about developing in a person a particular attitude. It is about shaping the person while learning to spell in the first place, and the fundamental imaginations to which spelling is connected. Noah Webster’s famous three volume compendium, A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, consisting of a speller (Webster, Citation1783), a grammar (Webster, Citation1784), and a reader (Webster, Citation1785), did not aim simply at empowering Americans to spell, write, and read, but at creating Americans by virtue of spelling, writing, and reading (Bynack, Citation1984). Indeed, this concept has been extremely successful, as may be indicated by an illustrated adaption of Webster’s language education by Barbara Cooney (Cooney & Webster, Citation1960).

The book cover of the textbook (see ) brings it to the point. English learning is not only about learning English and the ability to assert oneself in life in a more or less articulated way, but it is about becoming a certain person within a cultural collective, the nation. In this case, it was about becoming a loyal U.S.-American, and this was in fact already Noah Webster’s concern after U.S. independence. In relation to the formation of school subjects, this phenomenon has been identified as Creating an American Institution (Popkewitz, Citation1987), and, with regard to textbooks, it has been discussed on several occasions, for example, in Ruth Miller Elson’s (Citation1964) Guardians of Tradition: American textbooks of the nineteenth century or Hillel Black’s (Citation1967) American Schoolbook. Yet, although (U.S.-)‘American’ is highlighted in these studies, it is hardly explicitly discussed as a particular national-cultural thesis about belonging and identity, even though it can be, and in fact is, quite different in other countries that are governed in their own practices of the overall cultural processes of curriculum-making by the idiosyncratic values of their respective nations.Footnote7 Hence, the issue is not only about the knowledge children are exposed to and have to learn while going through curricula in their school life, although that is certainly important. More important, however, seems to be, in this context, the development of what may be called ‘national literacy’,Footnote8 aiming at nationally-minded citizens who are able to ‘read’ the constant national symbols, and understand and interpret them as an assurance of their collective identity. The modern school―and this is the final thesis―is the genuine state or public organization that develops this ‘national literacy’, the fundamental skill that permanently tells us whether we are at home or abroad or whether we are among our national peers or surrounded by foreigners.

Figure 3. Cover of The American Speller: An Adaptation of Noah Webster’s Blue-Backed Speller (Cooney & Webster, Citation1960).

Nations are never built; they are in constant processes of being re-built; as Ernest Renan rightly said some 150 years ago, the nations’ existence is a daily plebiscite (Renan, Citation1882, p. 27). Nations are, in a more recent understanding (Özkirimli, Citation2010), discourses that needs to be performed, langues that need paroles, and vice versa. Thus the modern state, which always needs legitimacy in its power structure and sees in the nation the outstanding means of obtaining this legitimacy through emotions and attitudes, was and is always ready to provide the institutional infrastructure in which the nation is constantly renewed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Tröhler

Daniel Tröhler has been Professor of Foundations of Education at the University of Vienna since 2017 and Visiting Professor at the University of Oslo since 2018. His research interests lie in the inter- and transnational developments of the last 250 years and he relates modern history of ideas and institutional history within the framework of a broader cultural history by focusing on (educational) political and educational ideas and their materialization in school laws, curricula and textbooks, comparing between different national or regional developments and investigating their possible mutual influences. His book Languages of Education: Protestant Legacies, National Identities, and Global Aspirations (Routledge 2011) received the American Education Research Association AERA Outstanding Book of the Year Award in 2012. He is currently working on the development of an ERC project proposal Nation state, curriculum and the fabrication of national-minded citizens.

Notes

1. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Stanford Graduate School of Education 5 September 2019.

2. I am grateful to Mark Swenson, author and Point Roberts historian, to whom I owe much of the following information about Point Roberts. I learned much from his public talk Point Roberts Backstory: Tales, Trails and Trivia of an American Exclave (Swenson, Citation2019), from his book of the same name (Swenson, Citation2017), from an interview with him that was conducted over Skype on 23 August 2019, and from further email exchanges.

3. In this context, I understand ‘curriculum’ as the organized learning arrangements established by the respective authorities and which pursues specific goals that do not necessarily have to be explicit. This latter aspect of the ‘hidden curriculum’—which complements that of the ‘intended curriculum’ (Schubert, Citation2008, pp. 407–408; Westbury, Citation2008, p. 49)—has, here, less to do with social or gendered concepts of social order (see, for instance, Apple, Citation2004) than with the question of how children are to learn national values on their way to becoming loyal citizens of a (nation-)state. I am of course aware that if I look only at this one aspect of curriculum-making—curriculum policy making, that is, curriculum planning and curriculum development as a form of particular practice (Deng, Citation2018, p. 697)—, I pay less attention to other aspects of curriculum studies, especially the questions of what is actually being taught and what is effectively being learned in the classroom. In this sense, these considerations are not made to contribute directly to curriculum development, but to contribute to what Pinar et al. (Citation1995) once called the Understanding Curriculum. However, a better understanding of how certain cultural (or indeed national) values are incorporated into the practical processes of curriculum-making is not irrelevant for improving these curriculum-making processes.

4. See footnote 2.

5. It is important to stress that in the following the article confines itself only to the more theoretical attempts to explain the phenomena of the nation or nationalism. Historical case studies that emphasize the important role of education in the construction of a single nation, such as Weber (Citation1976) for the case of France or Harp (Citation1998) for the controversial border regions of Lorraine and Alsace, are not meant here. For a broader systematic overview on how theories of nationalism deal with educational issues in general and curricular questions in particular, see Tröhler and Maricic (Citation2020).

6. As in footnote 5, it is important to stress that this assessment is not derived from historical case studies, such as that by Tanner and Tanner (Citation1990), or by more general historical reflections, for instance, by Boser (Citation2016), or of cross-national historical case studies (Horlacher, Citation2018; Tröhler et al., Citation2017), but from theoretical clarification attempts and reviews. These may be ignored, but the role of handbooks or encyclopaedias in the codification of knowledge would be underestimated.

7. It seems to me that this issue has not yet been sufficiently researched and, in times of a globalized research logic as promoted by the OECD and that largely ignores national curricula (see next footnote), it is almost ignored or at least not getting the attention it deserves in order to understand what it means to become a loyal citizen of a nation-state.

8. There is a rich discussion on the phenomenon of literacy and literacies (see for instance, Collins, Citation1995; Rex et al., Citation2010) that goes well beyond today’s perhaps dominant understanding of literacy as defined by PISA, according to which the ‘term “literacy” is used to encapsulate … what students can do with what they learn at school’ (OECD, Citation2003, p. 12). The proposal to introduce the concept of ‘national literacy’ in the field of curriculum studies is not so much to challenge the content of these formerly-mentioned, more substantial discussions as to introduce a new dimension that may not have received enough attention so far, particularly not in the realm of PISA where it is said that it ‘uses as its evidence base the experiences of students across the world rather than in the specific cultural context of a single country’ (p. 24). ‘National literacy’, therefore, absolutely means to focus on the particular ‘cultural context of a single country’ that can also be labelled as the ‘nation’, understanding ‘nation’ as a dominant cultural thesis (or discourse) about who ‘we’ are and who others are not.

References

- Apple, M. W. (2004). Ideology and curriculum (3rd ed. ed.). Routledge Falmer.

- Belshaw, J. D. (2016). Canadian history: Post-Confederation. BCCampus.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Sage Publications.

- Black, H. (1967). The American schoolbook. William Morrow & Company.

- Boser, L. (2016). Nation, nationalism, curriculum, and the making of citizens. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory (pp. 1–6). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_3-1

- British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2019a). BC’s new curriculum: Social studies 10. Government of British Columbia. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/10

- British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2019b). BC’s new curriculum: Social studies 11. Government of British Columbia. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/11/courses

- British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2019c). BC’s new curriculum: Social studies 12. Government of British Columbia. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/12/courses

- Buchardt, M. (2015). Cultural Protestantism and Nordic religious education: An incision in the historical layers behind the Nordic welfare state model. Nordidactica - Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 5(2), 131–165.

- Bynack, V. P. (1984). Noah Webster’s linguistic thought and the idea of an American national culture. Journal of the History of Ideas, 45(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/2709333

- Calhoun, C. (1997). Nationalism. University of Minnesota Press.

- Collins, J. (1995). Literacy and Literacies. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000451

- Comte, A. (1822). Plan des travaux scientifiques nécessaires pour réorganiser la societé. Éditions Aubier-Montaigne.

- Connor, W. (1990). When is a nation? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 13(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1990.9993663

- Cooney, B., & Webster, N. (1960). The American speller: An adaptation of Noah Webster’s blue-backed speller. Crowell.

- Deng, Z. (2018). Contemporary curriculum theorizing: crisis and resolution. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(6), 691-710.

- Elson, R. M. (1964). Guardians of tradition: American textbooks of the nineteenth century. Garland Publishing.

- Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Blackwell Publishing.

- Green, A. (1990). Education and state formation: The rise of education systems in England, France and the USA. Macmillan Press.

- Hacking, I. (1986). Making up people. In T. C. Heller, M. Sosna, & D. E. Wellbery (Eds.), Reconstructing individualism: Autonomy, individuality, and the self in Western thought (pp. 222–236, 347–348). Stanford University Press.

- Harp, S. L. (1998). Learning to be loyal: Primary schooling as nation building in Alsace and Lorraine, 1850–1940. Northern Illinois University Press.

- Horlacher, R. (2018). The same but different: The German Lehrplan and curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1307458

- Hughes, R. E. (1902). The making of citizens: A study in comparative education. Walter Scott.

- Ichijo, A., & Uzelac, G. (Eds.). (2005). When is the nation? Towards an understanding of theories of nationalism. Routledge.

- Kim, J. (2018). Lifelong learning for (re)making future citizens through South Korean curriculum reforms and OECD PISA. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1550385

- Lugg, C. A. (2017). Educating for political activism and subversion: The role of public educators in a Trumpian age. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(10), 965–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1312594

- OECD. (2003). Literacy skills for the world of tomorrow. Further results from PISA 2000.

- Özkirimli, U. (2010). Theories of nationalism: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P., & Taubaum, P. M. (1995). Understanding curriculum: An introduction to the study of historical and contemporary curriculum discourses. Peter Lang.

- Popkewitz, T. S. (Ed.). (1987). The formation of school subjects. The struggle for creating an American institution. The Falmer Press.

- Popkewitz, T. S. (2004). Historicizing the future: Educational reform, systems of reason, and the making of children who are the future citizens. Journal of Educational Change, 5(3), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JEDU.0000041042.53119.f5

- Prak, M. (2018). Citizens without nations: Urban citizenship in Europe and the World, ca. 1000–1789. Cambridge University Press.

- Renan, E. (1882). Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? Calmann Lévy.

- Rex, L. A., Bunn, M., Davila, B. A., Dickinson, H. A., Ford, A. C., Gerben, C., McBee Orzulak, M. J., Thomson, H., Maybin, J., & Carter, S. (2010). A review of discourse analysis in literacy research: Equitable access. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(1), 94–115. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.45.1.5

- Rousseau, -J.-J. ([1755] 2002). Discourse on the origin and foundations of inequality among mankind. In S. Dunn (Ed.), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The social contract and the first and second discourses (pp. 69–148). Yale University Press. (Original work published 1755).

- Rousseau, -J.-J. ([1762] 2002). The social contract. In S. Dunn (Ed.), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The social contract and the first and second discourses (pp. 149–254). Yale University Press. (Original work published 1762).

- Sadler, M. E. (1900). How can we learn anything of practical value from the study of foreign systems of education? In Surrey advertiser. Guilford: Surrey Advertiser Office.

- Sailor. (2017, August). How many school days the students have in a BC high school? [Forum post]. http://www.rolia.net/f/post.php?f=4096&p=346

- Schubert, W. H. (2008). Curriculum Inquiry. In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He, & J. A. Phillion (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 399–419). Sage Publications.

- Siebers, H. (2019). Are education and nationalism a happy marriage? Ethno-nationalist disruptions of education in Dutch classrooms. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1480354

- Smith, A. D. (1991). National identity. University of Nevada Press.

- Swenson, M. (2017). Point Roberts backstory: Tales, trails and trivia of an American exclave. Village Books.

- Swenson, M. (2019, March 14). Point Roberts backstory: Tales, trails and trivia of an American exclave. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1n9etwNxpBs

- Tanner, D., & Tanner, L. (1990). History of the school curriculum. Macmillan.

- Tröhler, D. (2011). Languages of education: Protestant legacies, national identities, and global aspirations. Routledge.

- Tröhler, D. (2016). Curriculum history or the educational construction of Europe in the long nineteenth century. European Educational Research Journal, 15(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116645111

- Tröhler, D. (2020). Learning, progress, and the taming of change: The educational aspirations of the Age of Enlightenment. In D. Tröhler (Ed.), A cultural history of education in the Age of Enlightenment (pp. 1–23). Bloomsbury.

- Tröhler, D., & Maricic, V. (2020). Education and the nation. Educational knowledge in the dominant theories of nationalism. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. University of Vienna, Department of Education.

- Tröhler, D., Westberg, J., & Berg, A. (Eds). (2017). Physical education and the embodiment of the nation. Special Issue of the Nordic Journal of Educational History, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.36368/njedh.v4i2.92

- Verdery, K. (1993). Whither “nation” and “nationalism”? Daedalus, 122(3), 37. http://www.jstor.com/stable/20027181

- Weber, E. (1976). Peasants into Frenchmen: The modernization of rural France 1870-1914. Stanford University Press.

- Webster, N. (1783). A grammatical institute of the English language comprising, an easy, concise, and systematic method of education, designed for the use of English schools in America. In three parts. Part I. Containing, a new and accurate standard of pronunciation. Hudson & Goodwin.

- Webster, N. (1784). A grammatical institute of the English language comprising, an easy, concise, and systematic method of education, designed for the use of English schools in America. In three parts. Part II. Containing, a plain and comprehensive grammar, grounded on the true principles and idioms of the language; with an analytical dissertation, in which the various uses of the auxiliary signs are unfolded and explained: And an essay towards investigating the rules of English verse. Hudson & Goodwin.

- Webster, N. (1785). A grammatical institute of the English language comprising, an easy, concise and systematic method of education; designed for the use of schools in America. In three parts. Part III. Containing, the necessary rules of reading and speaking, and a variety of essays dialogues, and declamatory pieces, moral, political and entertaining; divided into lessons, for the use of children. Barlow & Babcock.

- Westbury, I. (2008). Making Curricula: Why do states make curricula, and how? In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He, & J. A. Phillion (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 45–65). Sage Publications.

- Wimmer, A. (2018). Nation building: Why some countries come together while others fall apart. Princeton University Press.