ABSTRACT

This paper looks at the experiences of school history education and explores the impact this education has had on the development of young adults and their sense of identity in England. Adopting a qualitative approach, this study used semi-structured interviews with twenty young adults, aged 18–22, some from white backgrounds, but most from minoritized ethnic backgrounds.Footnote1 Four broad categories were identified in the data, namely ‘values and value’, ‘identity development', ‘curriculum connections’ and ‘narrative templates’. In the majority of cases, these young adults felt that history was important and had a role to play in addressing societal issues such as racism. However, the curriculum largely ignored the histories of minoritized ethnic groups, as the dominant narrative template favoured a white, Anglo-centric view of the world, and so served to fuel a sense of disconnection to the curriculum and to the state more generally. This paper suggests there is a need to pay closer attention to the place of history education in shaping a sense of belonging and personal identity, through a multiperspectivity approach.

Introduction

The killing of George Floyd in May 2020 sparked a huge global reaction, highlighting major concerns around long-standing racial inequality and injustice in many societies. In turn this gave momentum to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) campaign, with mass demonstrations across the world. Within the UK, much attention focused on Bristol and the statue of Edward Colston, a divisive figure, as he was a major benefactor for the city, but whose wealth had been founded on the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. In June 2020, protestors toppled the statue before throwing it into the nearby river. This event turned a particular spotlight onto history, raising significant questions about Britain’s involvement in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, and wider questions about British colonialism, and the role of Empire in creating racist ways of thinking and systematizing racism that still permeate many facets of society today (Bhopal, Citation2018).

Amidst this mixture of social and political events, there were widespread calls in the UK to decolonize the school curriculum, especially the history curriculum, and move away from a dominant white Western vision of the world. Such calls were contested. In response to perceived attacks on the portrayal of Britain’s past, the Conservative government, with other right-wing support, launched what can be seen as a ‘culture war’. Robert Jenrick, a government minister, published an article, claiming ‘We won’t allow people to censor our past nor pretend we have a different history to the one we have’ (Jenrick, Citation2021). However, the issue is that different groups identify with and look for different things from the past; as Lévesque (Citation2017) argues:

most ethnic minorities seek cultural accommodation and more equitable inclusion within the dominant national narrative so as to avoid exclusion … national groups want to maintain distinctive cultures and historiographical narrations because they constitute the essence of their community identity

Social psychologists recognize the central role that history plays in ‘tell[ing] us who we are, where we came from and where we should be going’ (Liu & Hilton, Citation2005, p. 537), as history helps to create, maintain or challenge a sense of individual and collective identity.

It is against this background that this paper is set. Participants were young adults, aged 18–22, of whom 15 were from a minoritized ethnic or mixed ethnic background. Apart from one, who was educated in Northern Ireland, all participants had been educated in England. The study focused on their study of history and the impact of this on their sense of identity. The focus on ethnicity as a key factor was due to existing research that suggests students from minoritized ethnic backgrounds found little personal connection to history in schools (Harris & Reynolds, Citation2014; Wilkinson, Citation2014), which undermines attempts to create a stable sense of self. Previous research in this area has predominantly focused on the experiences of students in schools and their encounters with school history, rather than young adults who have left school and continue to encounter history in their everyday lives.

In order to explore these issues the following research questions were set:

What were these young adults’ experiences of school history?

What is the relationship (or ongoing relationship) between these young adults’ encounters with history, both in and out of school, and their sense of identity?

Literature review

In order to examine the experiences of young adults and the ways in which learning about the past has impacted on their sense of self, the literature review will firstly explore the relationship between history and identity. The next section will then explore how school history is experienced. This section is broken into three sub-sections: namely what is taught in school history; the importance of narrative templates; and finally the experiences of minoritized ethnic groups and their encounters with school history.

History, belonging and identity

Generally speaking, ideas about identity formation have moved from psychological theories, which stress the role of the individual in shaping their own sense of being, towards a more sociological model, where contextual factors also shape identity (Schachter, Citation2005). As such, micro- and macro-systems in which one is situated, such as family, school, the wider community and society as a whole, become important factors in moulding identity. Knowledge of the past encountered at these different levels can shape one’s sense of self.

The role of history within this process is however complicated and contested, and partly dependent on how the purpose and nature of history are understood. Lee (Citation1992), for example, argues that the point of studying history is to get better at history. This involves a focus on the disciplinary nature of the subject—this includes understanding how claims to knowledge are made, based on an incomplete evidential record, and how our understanding of the past is structured and constructed (e.g. through second-order concepts such as causation, change and continuity, which shape how we think about the past). Lee (Citation1992) states that studying history does not necessarily make someone more patriotic or a better citizen. He does not deny that history can help pupils see the world differently, but that is not the explicit objective of learning history. The Ajegbo Report (DfES, Citation2007) however explicitly presented the case that history has a role in developing social cohesion through an emphasis on diversity and identity, as a means of promoting tolerance and acceptance. Barton and Levstik (Citation2004) argue that history should help people work towards a democratic, common good. One way in which this can happen is through some form of identification with a community, however they warn that ‘when we link ourselves to one community, we often cut ourselves off from others, sometimes with ruinous consequences’ (Barton & Levstik, Citation2004, p. 46).

Consequently, debates about what form of identity should be developed and therefore what history should be taught are common. Many governments attempt to control what is taught in the history curriculum (Taylor & Guyver, Citation2011) to present a positive, nationalistic view of the past, which can act as a source of a cohesive, collective memory, or ‘hegemonic historical representation’ (Liu & Hilton, Citation2005). This approach tends to assume that national identity is relatively fixed and stable, and offers people the ability to align with a group. This fits with Tajfel and Turner’s (Citation1979) social identity theory, where people identify themselves as belonging to particular social groups. As Liu and László (Citation2007, p. 86) argue, most people are striving for a ‘positive distinctiveness, coming to understand herself as part of a group or category that is positively distinct from out-groups’. However, as Hall (Citation1994) has shown, identity is more fluid. He acknowledges that cultural identity is in part based on ‘stable, unchanging and continuous frames of reference’ (Hall, Citation1994, p. 393), which develops a shared, collective sense of self, but also argues that identity is about differences. Identity is a process of production, that is never fully complete, but is always in construction, through an ongoing series of interactions in time and space (Hall, Citation1994).

The process of interaction between the past and a current sense of self is one of the reasons why it is challenging to understand how history impacts on identity. Savenije et al. (Citation2014, p. 522) found pre-existing identities shape students’ ability to engage with the past and that ‘[w]hen students cannot integrate their own understanding, history will be less meaningful to them’. This idea is supported by other studies from differing contexts (Angier, Citation2017; Goldberg, Citation2013; Peck, Citation2018). Huber and Kitson (Citation2020) however feel the relationship between identity and history teaching is more complex. Schachter (Citation2005) argues that because there is a connection between the psychological development of identity and culture, the existence of multiple diverse cultures means there are multiple developmental psychologies. Thus, in Huber and Kitson’s (Citation2020) view young people have multiple (sometimes conflicting) identities, which are not always based around a sense of belonging to a nation; therefore the way young people engage with history may be more fluid. But as Barton (Citation2013) argues, the issue with identity and history is less to do with the fluidity of identity but understanding what these multiple identities consist of.

The complex nature of identity, especially those from minoritized or mixed ethnic backgrounds has long been recognized. Du Bois (Citation1903) spoke about ‘twoness’ and having a double consciousness, where one is aware of one’s own identity as well as how one is seen by others. For this study though, the notion of a hyphenated identity seemed more appropriate. The term hyphenated identity implies a dual (or more complex) identity, where the individual seems to oscillate between different cultures and as Radhakrishnan (Citation1996, xiii) states, the hyphen is the space where individuals try ‘to co-ordinate, within an evolving relationship, the identity politics of one’s place of origin with that of one’s present home’. As Raghunandan (Citation2012) explains, the term has emerged out of the move towards holding multiple identities and is often applied to the second- or third-generation descendants of migrants. The term underscores the importance of a sense of displacement and a quest for belonging (Chen et al., Citation2012), and also seems to reflect the ways in which many of the participants identified.

The experience of school history

What history is taught in schools?

It is surprisingly difficult to identify what anyone in a school in England would have studied in history, particularly between the ages of 11–13/14 (beyond this age history is an optional subject, but it is slightly easier to identify general areas of history which are taught for examination post-14). This is partly because the History National Curriculum, which sets out what should be covered in the 11–13/14 age range, does not strictly apply to all types of secondary schools in England; for example, although state-funded comprehensive schools (which are controlled by Local Authorities) have to follow the National Curriculum, state-funded schools like academy schools (which increasingly make up the bulk of secondary schools in England but are independent of Local Authorities) have more curricula freedom.

The most recent survey by the Historical Association (HA) (Burn & Harris, Citation2021) does suggest many secondary schools are changing their curriculum by including more diverse content. For example, 86 schools out of the 286 which responded said they were teaching a topic on pre-colonial Africa. History related to migration stories was also becoming more prevalent. Yet such changes seem to be a recent phenomenon. Prior research, although limited in scope, does suggest that the history curriculum in schools is characterized by a focus on white, British history. Also that there is considerable inertia in content selection, i.e. following the introduction of the history National Curriculum in 1991, amendments to the curriculum in 1995, 2000, 2008 and 2014 did not fundamentally change what was taught (Harris & Reynolds, Citation2018). The individuals involved in the study reported in this paper would have been in school when the 2008 and 2014 versions of the curriculum existed.

A long-standing criticism of the history curriculum has been its narrowness and lack of diversity. Arday (Citation2020, p. 12) argues that Black and other minoritized ethnic groups have long been positioned as ‘space invaders’ or ‘outsiders’. Lidher et al. (Citation2021) also argue that the history taught in English schools has been a highly selective, monochrome national history that omits or forgets the diversity of peoples that are covered under the title of ‘British’ history. Such an approach does little to foster a sense of belonging for minoritized groups, nor does it help the majority group to understand why Britain is a multicultural nation.

Not only is the content of the history curriculum important, but the way in which that content is presented also matters. One approach, and noted previously as one of the reasons for teaching history, is to adopt a disciplinary approach. This has been a central idea in discourse about the history curriculum in England since the 1972 Schools Council History Project (SCHP, now known as the SHP). One aspect of this approach is the need to understand that the past is constructed and therefore it is possible to have competing interpretations of history (see for example, Historical Association, Citation2019). However this does not necessarily ensure that students learn to see the past from a range of views, as students may deconstruct a particular interpretation, without exploring alternative ones, or if they study competing interpretations these may be competing Anglo-centric perspectives. A more fruitful approach appears to be teaching using multiperspectivity. Abbey and Wansink (Citation2022, p. 68) describe this as ‘the process, strategy, or predisposition of looking at a situation from different points of view’. It is an approach that has been used in post-conflict societies to help bridge divides by examining the past from the perspectives of the different sides. In Northern Ireland, Barton and McCully (Citation2010, Citation2012) found that students who were taught about alternative perspectives were able to draw upon these to inform their own views on the troubled nature of the region’s past, but that students could still struggle to fully engage with alternative historical perspectives. Another approach, that has gained attention following the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, is to decolonize the curriculum. In some ways, decolonizing the curriculum is similar to a multiperspective approach, as it is about ‘ensuring that the views and voices of marginalized groups are heard, acknowledged and appreciated’ (Moncrieffe et al., Citation2020, p. 9), but it goes further than multiperspectivity as there is also a need for ‘whiteness’ and ‘white privilege’ to be recognized and to understand how they have shaped how the past, present and future is seen.

The importance of narrative templates

Wertsch’s (Citation2002, Citation2008) notion of a narrative template helps explain what view of the past exists within collective memories and how this shapes the way people engage with history. Narrative templates are powerful ways of thinking:

they reflect strongly held commitments to a particular narrative account, commitments that are often masked by a tendency to think that our account simply relates what happened.

Such templates are often presented, created and/or reinforced through various cultural tools, such as heritage sites, national commemorations and, importantly, school curricula. These templates can therefore play a significant role in the formation and social construction of in- and out-groups. As Bertossi et al. (Citation2021) explain, stories of migration are used to determine who are deemed ‘natives’ and are therefore part of the national story, and those who are ‘non-natives’ and therefore excluded. Lidher et al. (Citation2021) exemplify this in the case of the Windrush Scandal; the arrival of the passenger liner, the Windrush, with several hundred men from the Caribbean shortly after the Second World War is portrayed as a story of migration and the start of multicultural Britain in public discourse and collective memory. Yet, these arrivals were not migrants; legally, as members of the British Empire, they were British citizens. This narrative template also ignores the extensive historical record that shows Britain was a multicultural society for centuries beforehand.

This distortion happens because the narrative template tends to reflect the perspective of the dominant group in society, as well as the political views of those in power, and can become embedded in curriculum documents and/or textbooks (Foster, Citation2011; Taylor & Guyver, Citation2011). As Wertsch (Citation2008, p. 142) explains, the power of these templates ‘stems in part from the fact that their abstract nature typically leads to their being unnoticed and especially “transparent” to those employing them’. For the large majority of the population, the narrative template is invisible and uncritiqued because it is what they believe happened. In many ways this replicates notions of white privilege, which is largely invisible to white people (Bhopal, Citation2018). Thus, historical narratives created in school history curricula in England, are often based around a white, male, Anglocentric curriculum (Harris & Reynolds, Citation2018). This can simply reproduce notions of white, British exceptionalism, adopting what has been termed ‘our island story’.Footnote2

Minoritized ethnic students’ experiences of being taught history

The invisibility of narrative templates has been noted in a number of studies that have explored the experiences of minoritized ethnic students and the history they encounter in schools. Wilkinson (Citation2014) stresses the absence of the Muslim experience within the history curriculum, and the alienating impact this has on Muslim boys. Drawing on the idea of a ‘null’ or ‘absent’ curriculum, Wilkinson carefully details the ways in which the Muslim role in history and place within notions of British history is systematically omitted. Harris and Reynolds (Citation2014) show how students from minoritized ethnic backgrounds see little personal connection to the history curriculum because of their absence or their negative portrayal. There is either an incessant focus on white history, or where there is a Black presence in the history studied, this is invariably from the perspective of victimhood. Additionally, there is a concern that issues are ‘displaced’; for example many students in England study Black Civil Rights in the US, rather than in Britain, thereby implying this is an issue pertinent to the American, rather than the UK, context. Students from minoritized ethnic backgrounds often find it hard to engage with school history, as it presents them with a different view of the past to the one they had acquired elsewhere (Epstein, Citation2009; Peck, Citation2010).

Yet missing from many of these studies is the experience of young adults. Typically, studies have involved young people whilst still at school and how they engage with the school history curriculum. What is less clear is whether this has any lasting impact on how young people identify, and the role of history beyond compulsory schooling in the continuing renewal and renegotiation of identity.

Methodology

This article offers an in-depth, qualitative study of a sample of 20 young adults who had completed formal education in the UK, who were able to offer detailed accounts and introspections of their encounters with history, both in and out of a formal education context, and how this had affected their sense of identity.

The study originated as an undergraduate dissertation, but due to the numbers wishing to be involved, funding was obtained to expand the research. Participants were recruited initially through social media and were asked to complete a questionnaire, indicating their willingness to be interviewed for this study, so the early recruitment process was opportunistic. Thereafter the sample ‘snowballed’ with the questionnaire being shared through participants’ connections. Through this process, 31 individuals indicated they would be happy to be interviewed, of whom 20 ultimately agreed to an interview. Information about the participants’ ethnic backgrounds and their educational profiles, especially in the context of history education, is detailed in below. Ethical approval was requested and granted by the host institution, and participants’ consent was obtained, having been given full information about the project.

Table 1. Demographic background and educational experience of participants.

Participation in the research involved one semi-structured online interview (due to Covid restrictions at the time), that typically lasted 45–60 minutes, where students were asked about their experiences of learning history in school, their views of the history curriculum in England, and how this may (or continue to) influence their sense of identity/ies. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Personal details were removed for confidentiality and anonymity purposes, and the names of participants were replaced with pseudonyms. Clearly, interviews, particularly those that involve a degree of retrospection, may suffer from participants’ selective memories. In addition, the study happened at a time, following the BLM protests, where there was heightened awareness of issues around the history curriculum. The context of this study, and what participants recollected, however partial, and the impact of societal concerns was important, because it is this working memory and its intersection with socio-cultural issues that helps to shape people’s sense of identity.

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022) was used to analyse the data. Familiarization with four initial transcripts was followed by a process of open coding by all three researchers (Saldaña, Citation2016). This was followed by a meeting to discuss codes and to generate initial themes. Coding around enjoyment of history and its purpose became the theme of ‘value and values’. Codes around sense of self, belonging and perceptions of exclusion led to the theme of ‘identity development and history’. Coding around what participants recollected learning in history and a sense of omission fed into the theme of ‘curriculum connections’. Codes around the perspective that seemed to be adopted by the teacher and a sense of distortion were linked to the theme of ‘narrative templates’. Each member of the research team was then allocated a theme or themes to explore and review in the remaining transcripts. The analysis undertaken for each theme was then checked by the more experienced member of the research team. This was followed by collaboration between all three researchers, revisiting and refining the codes and data in an iterative process, to ensure a consensus was reached that there was a clear demarcation between the themes. Also at this stage, dimensions or sub-themes of the main themes were identified; for example within the theme of ‘values and value’, key ideas around the purpose of and attitudes towards history were identified.

Whilst presenting the findings, it is also important to acknowledge the potential limitations of the study. Our research highlights rich retrospections and perspectives, and is underpinned by the assumption that reality is multiple, and knowledge is co-created, in this case, by the participants, researchers and readers. While our study was small-scale and limited by time and resources, Smith (Citation2018) suggests qualitative data can still be generalized through ‘naturalistic generalizability’, such as, if the perspectives highlighted in the research ring true to the reader, or through ‘transferability’, if the perspectives remind the reader of similar experiences they may encounter in other settings. However, this relies heavily on readership, and we accept that not all of our interpretations will be relatable, true, nor transferable for every reader. Our analysis is also shaped by our view that conceptual and theoretical generalizations are not fixed but fluid and responsive to the context and positions of the researchers. As researchers we occupy different identities; for the purpose of this paper it is worth acknowledging that the first author identifies as British-Indian, whilst the other authors identify as white British (and the second author is a third-generation descendent of migrants). However, we did not discuss our interpretations of the data with the participants following data collection, which is a limitation of the study, despite our efforts to ensure their ideas were understood during the interviews. Nonetheless, we have tried to highlight the importance of participants’ voices.

Findings

In this section we present the four key themes that emerged during the analysis of the interviews. One theme focuses on what value the participants attributed to the study of history and the ways in which they think history is important in a rounded education. A separate issue, although connected to the idea of value, is how history shapes individuals’ sense of identity/ies. In particular, an issue that emerged was how there is an on-going, iterative process between an understanding of history and an understanding of one’s identity/ies. This in turn reflects the two other themes that were identified. One focuses on the actual curriculum these participants experienced and their sense of the appropriateness and relevance of this to their lives. This then links to the notion of ‘narrative templates’ and the stories that are told through history, and the impact these have on shaping perceptions.

Value and values

A major theme that was identified was the value which the participants attached to the study of history, as well as the values that they thought ought to be promoted through its study. Only four of the participants specifically mentioned that history lacked any importance to them, and for three of these part of the reason was the one-sided nature of what they had been taught. Seven participants stated that they actively enjoyed history (not necessarily at school) but they thought the subject was fascinating and was important in a good education.

The overwhelming reason for studying history, mentioned by 16 participants, was the understanding and insights that it could provide in understanding the world as it is today. As Amal explained:

I think history education should teach children about the world where they have grown up in and a variety of experiences faced by those who live on our planet, not just a particular type of people, not just European history, but also looking at things like America, South America, Africa, and Asia.

Here we can see that history is seen as helping young people gain a wide understanding of people and the world in which we live, and should reflect a more global perspective. This seemed to be an important concern, for as Harun stated, history should help young people understand others:

it also helps you understand differences between different communities, different cultures and backgrounds and why people possibly do things in a certain way, or dress in a certain way, different faith groups. So it just helps you have a very good understanding of the multicultural world that we live in, in today’s day and age.

For many of the participants this meant that history was a means to open minds, allowing people to have a more critical understanding of the past and its implications. For Ana:

history sort of links to everything. And I think that it would give a more rounded view to people as to why certain people are viewed a certain way, and what sort of narrative that was fitting at a certain time. And so yeah, yeah, I definitely do think that that would shape people’s views around race relations, and, you know, how people have sort of been taught to be less inclusive of certain groups.

History is therefore seen as having the ability to create a space where understanding of the complexity of the world in which we live can be developed, with a sense that this knowledge can help to create a more harmonious and cohesive society. Such a view emphasizes the more extrinsic, civic reasons for studying the past such as history’s potential to understand and accept others. There were however caveats to this expectation. The majority of participants noted this could only happen when people were aware of multiple perspectives. For Neal, drawing on his experiences growing up in the sectarian divides of Northern Ireland, the need to understand the perspectives of others was paramount, and which probably reflects the type of multiperspective approach that is adopted within the Northern Irish history curriculum. Also, Cillian was aware that his history education was lacking, particularly noting the absence of the history of the British Empire, and that history is ‘not all sunshine and rainbows’. Indeed, several participants were concerned that a narrow, one-sided perspective view of the past was unhealthy. For example, Harun was worried such history makes people believe ‘one flag is better than another, or one group of people are better than another’.

The extension of this is the development of racist attitudes. In Jaspreet’s view, the Anglo-centric view of the past, which dominated her experience:

just reinforces [racism], that they’re the best people that being English is the best race compared to anything else. And it’s like, they’re … superior, which you’re just reinforcing racism. And then you, then people question why are people racist here, it’s because you don’t teach anything except the English curriculum.

Such views highlight the concerns that history, if approached from an overly celebratory view of English history, far from promoting social cohesion can have a corrosive effect.

Collectively, the majority of the participants had a positive attitude towards history and recognized that it had an important role to play in everyone’s education, but only if certain challenges were addressed about the range and nature of what is studied (this will be explored more fully in the following three sections). The benefits of a good history education were seen to be quite profound. Although a number of participants mentioned the need to learn from past mistakes, many felt the most important lessons of the past were that issues such as racism and social cohesion could only improve if there was a more thorough understanding of the past and a recognition of the role played by the British Empire in shaping attitudes today, and an acknowledgement of the harm associated with the Empire.

Gaining a more rounded view of the past is therefore seen as imperative. Rita illustrates this, drawing on her own experiences:

when you get older, you actually start to realise how important history is, like, just for everything … there’s some people that just don’t know why are there so many Algerians in France, like that simple history, people don’t understand. And in order to understand that you understand the way things work. Or why is there always so much tension, with Israel? Why is this? … people just don’t understand? Because they, you can’t understand the world, you know? Yeah. I feel like that’s why [history] is so important.

Identity development and history

Although a handful of participants identified as white British (and of these one felt more Scottish due to feeling embarrassed about Britain’s history, and another from Northern Ireland felt his white peers saw him as not British enough due to his Northern Irish accent), the majority of participants came from a range of minoritized ethnic backgrounds. These participants described having a hyphenated identity, and many said they were not clear where they truly belonged. A common theme running through a number of interviews was experiencing some form of identity crisis. For example, Idris described encountering ‘an inner turmoil’, whilst Taran said: ‘I am British, but I guess I’m more Punjabi in my mind’. Similarly Jaspreet explained:

we’re living in a country where you know that they’ve done terrible stuff to your people at home. You know they have and they’re still doing it. They don’t care about your country, but you still live in it (Britain). So half the time like don’t want to live in this country anymore. But half the time that is a better life. You know, it is you can’t live a life in India that you live here.

In many ways this identity crisis contributed to a sense of dislocation. For Inayah trying to reconcile her identity as African, and as an Arab and as someone born in Britain was challenging, reflecting the idea of a hyphenated identity where people oscillate between different aspects of their identity, seeking an aspect to secure themselves to. For some, these issues are not helped by the way in which identities get ‘policed’. Although Idris, for example, felt accepted by the vast majority of people he encountered, many reported a clear sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and reported occasions where they had been ‘othered’. Harun said:

on a personal level, I feel like, and it’s not just me, I feel like people in my sort of, sort of background, feel like we’re sort of stuck in a limbo, in a sense, where we don’t have our own sort of Motherland that we can associate ourselves to, or sort of like a flag that we feel proud of and can stand behind. We don’t feel as though we’re fully accepted into British society, if that makes sense.

Amal described being one of only a handful of minoritized ethnic students studying history at university, and how the class naturally segregated along ethnic lines. Samira described how she would also police herself depending on who she was with, for example when discussing British history, she said:

you always have to be semi careful around how you speak about Britain and British history to white British people, as opposed to how you may discuss it with people of other ethnicities and everything. Because white British people will usually have that one sided history education coupled with the fact that like, there’s a great, great sense of national pride, especially recently, so you have to sort of tone down your criticisms of Britain … . It’s just to keep the peace on it just to keep yourself sort of on the safe side.

Aside from these issues relating to the participants’ sense of personal identity, the vast majority of them also recounted how they seldom related history to their own family backgrounds in school. As Ishaan explained: ‘I felt it was, felt there was more to the story than what we were being told … I feel like it’s like we said, it’s like a narratives or like a curated narrative’. This notion of being told a partial story or a highly selective story was common across participants. Ana, whose heritage is Spanish and Algerian, felt that her background was ignored in school history:

as a North African, I think that it’s quite it’s, it feels as if like that history isn’t as important as everywhere else in the world. And I think that that shouldn’t really be the case. I do think that some sort of African history should be touched on.

Rita, who identified as British Congolese, felt there was a ‘negative stigma’ about African history. Such feelings and the impact on participants whilst at school seem quite profound. Rita described how ‘it took me quite some time to grow into like, being African, if you can say, like become confident about being more African’. Cillian, whose parents are Irish and Vietnamese, described how learning about the Vietnam War had a massive positive impact on his sense of self:

I had been bullied a little bit in secondary school. So when we were learning about the Vietnam War, I just kind of felt quite proud. And my family are from Hanoi, so in around the Vietcong side, we just, it was quite fun in class, I really enjoyed, sort of like, being the centre of attention, people, you know, laughing and looking at me whenever we were saying stuff

However, Cillian’s positive experience is atypical. Nearly all of the participants felt as if they had been marginalized as a result of the history curriculum. There was a strong sense that minoritized ethnic histories are positioned as ‘other’ and outside of the normative story of a ‘white nation’, completely ignoring the complex diversity of history and the interconnectedness between past societies and cultures.

The main encounters with participants’ own history came through family stories. In many cases the stories told were deeply moving; Amal recounted how she learnt about her grandfather’s story:

I ended up calling my grandma one day. I think I just called her cos she wasn’t feeling well or something. And she was like … did you know that my dad moved from India to South Africa at the age of 11 on his own? I was like, what? So like, that’s like an 11 year old boy going to work in South Africa from India, because his parents couldn’t afford to keep him, like, alive in India, and he worked for another Indian family in South Africa.

Ignoring young people’s identity in the history classroom was seen as harmful. For participants such as Inayah and Amal this was an issue, as learning about how they fitted into history would have made them more comfortable in their identity. As Rita explained:

I feel like to deprive young people from that [their history] really derails them, you know, because some people, they just need something that interests them to keep going, you know, that one piece of history. Well, especially when you’re in secondary school, you’re really having an identity crisis, having that one lesson where you can actually learn about information that you can identify with, relate to information that’s just correct, you know, it’s important.

Many participants had a genuine interest in the past, often linked to their personal histories and had learnt more about their own backgrounds, either through their degree studies or out of personal interest. For many, there appeared to be a discernible shift in how they saw themselves, and as their knowledge of the past, connected to their backgrounds developed, so they felt more secure and settled in their personal identity. However, this shift is dependent on understanding their own personal histories. As Aliyah explained:

I think it’s important for children of colour, to also be able to understand why they are here in this country, their own history, and make them you know, actually be able to understand identity. I think, you know, for a lot of second-generation immigrants, for children of immigrants, I think they struggle with their identity, because they’ve obviously been born, for example, in Britain, they’ve grown up here, but because of the colour of their skin, or things like that, because of their family, I think they might have identity issues. And I think being able to understand your identity will really help them to feel more comfortable and not kind of feel afraid of being for example, British Asian or British African or whatever.

However, it seems minoritized ethnic students are being largely ‘short-changed’ by the school history curriculum, due to the absence of their historical experience and heritage from the curriculum.

Curriculum connections

An issue that emerged strongly from the interviews was the sense of (dis)connection to the topics the participants remembered being taught. In only a few cases could students genuinely feel what they studied had any connection to them and their sense of identity. For example, Charlotte, as a white British student, felt that the history she had studied in schools was interesting, and felt some sort of personal attachment:

I remember learning about World War Two and World War One and like the Great Fire of London and stuff like that. I found that quite interesting … I think with those, like with the world wars and stuff, like our grandparents were alive during that time. So I think it’s quite interesting to see what they experienced when they were younger.

Whilst, Neal, another white student from Northern Ireland, felt history should focus on British history first, and only once that has been learnt should a wider perspective be studied:

there’s people making a fuss to learn about other countries. But like without being rude, like, they don’t mean anything to us, personally, unless you have family there, they’re your background, whatever it is, your heritage and you wanna learn about the history, but I think it needs to start within the Union … learn about the people that are the ones closest to you. So why would you learn about some random African village that like, you have no idea about

In contrast, Harun, felt that learning British history was appropriate as he lived in Britain, but he also enjoyed studying the Crusades and the contribution of Indian troops in World War One as it resonated with him. Others, such as Inayah, Amal and Rita also explicitly referred to learning about the American civil rights movement. For Inayah, this was an important topic, because ‘especially as you’re growing up, and you’re trying to understand more about the people around you, and maybe your own background as well’. Amal also recounted how a study of civil rights ignited a genuine interest in history because it linked to her experiences, and how she used her local university library to read a range of books, such as Malcolm X’s autobiography. Unfortunately, too often the history taught did not connect with students from minoritized ethnic backgrounds. When talking about the Second World War, Idris said: ‘I thought it was very boring. We’re learning about bombs being dropped on England and how the Germans lost the war. Like who cares?’ Rita was so bored by studying history in school that she opted to study geography as one of her exam classes ‘because I learned more about the world’.

Generally there was a sense that the history taught failed to connect with students of colour, and this was recognized by white students, such as Charlotte:

People of colour, so they’ve, like, they’re not talking about their history at school. And that’s not fair. Because they’re still part of this country. So why should they not learn about their history in their culture?

Narrative templates

Throughout the interviews all participants referred to some sort of curated narrative at play when discussing the history education they received. There was a clear recognition that the history taught presented a one-sided, positive perspective of Britain’s history, and this was perceived as being because nearly all history teachers were white, and that this was what was expected in the curriculum. Keerat said ‘we never see the side of the story from the other countries’, whilst Rafi felt ‘there’s a lot of things that aren’t mentioned’. Two participants spoke of white and nationalistic portrayals of British colonialism, which were dominant in popular public discourse during the time of the interviews. As Harun explained, with reference to Winston Churchill, ‘[he] has been rated like the greatest Britain of all time … Yet … he was directly responsible for the death or the starvation of three million Indians’. Emily, one of the white British students, described the history curriculum as being ‘whitewashed’ and felt white students did not understand the negative impact Britain had on many countries. Nine of the participants mentioned that their different perspectives on the past came from their families and awareness of their family histories. Jaspreet, who was training to be a history teacher, described her feelings about how the history of Britain is presented:

Because when you’re getting told that the British Empire is such a good thing … by an English person, it’s like, you really do know that they’re just talking, they’re just talking about their own country. And it’s like, it’s limited. I’m looking at them thinking, how can they just have one perspective on it? Because they didn’t have the other perspective. Like, obviously, I know what happened in British Empire and what they did in India. I know both sides, whereas they didn’t, they would always side with British Empire.

Maeve described how her teachers used a British colonization board game, which was played in her all-white primary school, which she remembers enjoying, but on later reflection presents a naïve view of the process of colonization:

It made the experience of colonisation fun … “Oh, yeah, we’re going to go take that land”, “ahh yayy its got a gold mine on it” … we didn’t view it as offensive because it wasn’t talking about anything bad that happened. It was almost like this is a really positive thing. And I guess for the white people, the white British people, that was it was beneficial for them. … And maybe it’s dangerous, because it enabled us to just not think about it and just completely ignore the bad stuff, which I do.

For some participants the way history was taught was a form of deliberate distortion. Rafi felt history teachers were ‘indoctrinating these children with kind of false information … when’s there’s a whole other background story that isn’t mentioned that would maybe change the perspectives of certain people’. Ishaan described it as:

want[ing] people in Britain to maybe appreciate Britain or something like that. And so we will teach them history that paints it in a positive light that makes you more proud to be British, I don’t know something like that. It wouldn’t be financially or … it wouldn’t make sense to sort of, educate the youth of Britain in a way that would make them not like Britain, if that makes sense, I guess in the minds of like, governing bodies.

In some cases, participants emerged from their history education with major omissions. For example, four claimed, that having studied the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in school, they were unaware of Britain’s significant role in this, seeing it largely as an American issue. They only remembered being taught about Britain’s role in ending this trade. This does not necessarily mean the participants were not taught about Britain’s role, but that is what they left the classroom believing. The one-sided sense of how history is presented in the curriculum was further underlined by the feeling that ‘other’ history was either portrayed negatively or was simply absent. As Rita explained:

in history, or even in news, like all these Comic Relief, Red Nose Day, depicting Africans as poor, depicting Africa as unstable in the news. And, also, just like in history, they don’t teach you about Africa. They teach you about, okay, like the poorest country in the world, or kind of the problems of Africa, but they never teach about why it is what it is like, even when I was in history, I think in secondary school, they’ll teach you about British colonisation, but skip all the other bits … they’ll tell you about the Brits, that they went to India for the resources or whatever it was, like for cotton … .But then they’ll just skip like a whole bunch of history and then come back to like, Europe.

As mentioned in the section on the value and values of history, participants felt that the curriculum had to offer a more rounded perspective of the past, namely in the choice of topics to provide perspectives beyond the narrow white British stories encountered. As Jeevan explains, it is actually hard for white students to appreciate they are being presented with a particular narrative template:

you would need an outsider to challenge those views (white perspective on history). But if you’re from a white household and the teachers, like your friends are white, and you learn about white history, you wouldn’t be able to even consider learning about other people’s history, you will just, they will just go, you will ignore it, you will just not notice it.

Yet, because the majority of the participants had hyphenated identities and were from minoritized ethnic backgrounds, they felt in a stronger position to recognize the narrowness of the perspective they encountered in school history. As Idris explained:

It’s just if you’re white in England, you probably just don’t realise as or don’t consider the other races, constantly, all day. But if you are brown, you’re already thinking about being brown, you know, you know what I mean?

For eighteen participants, as mentioned previously, the realization about how perspectives of the past could be different came about because of their own personal research (reading, internet or social media) and/or through family histories. Three of the participants from minoritized ethnic backgrounds explicitly mentioned doing their own research whilst at university (although not necessarily connected to their studies) and six others said they had done additional research following the resurgence of the BLM movement. For students from white backgrounds the focus was on informing themselves about Black history, whereas students from minoritized backgrounds tended to focus more on histories related to their cultural heritage. It was generally unclear from the interview data when discussions with family members took place (i.e. when still in formal schooling or subsequently), but in twelve cases it was clear that finding out about history was an on-going activity, following the end of formal schooling, and this provided participants with evolving insights into the past.

Discussion

When examining the participants’ experiences of school history, a number of issues stood out. Much of the existing literature that has focused on how students from minoritized ethnic backgrounds feel about history shows that overwhelmingly these students are disconnected from history as a school subject. This is reflected in the paucity of minoritized ethnic students that choose to study history for GCSE, A levels and undergraduate level (Rodeiro, Citation2009; Royal Historical Society, Citation2018). However, this study makes clear that most participants felt that history was an important subject. This disparity may partly be explained by emphasizing that the participants’ concerns with history are to do with school history, and what they encountered in the history classroom, not history per se. Another explanation for the participants’ levels of interest in history may have been to do with the timing of the study, as a number of participants cited the Black Lives Matter movement as significant. Yet as noted above, many young people from minoritized ethnic backgrounds do feel alienated from school history (Wilkinson, Citation2014). In this regard, the participants appear typical of those in other studies, however few studies have examined the views of young people from minoritized ethnic backgrounds and their interest in history beyond the school curriculum. As such, this study raises further questions about interest in and perceptions of history more generally amongst this group.

The disconnect the participants felt was not necessarily related to the topics studied but was related more to how topics, such as the British Empire, were portrayed. It was the narrative template, seen as presenting a celebratory view of ‘our island story’ that was seen as problematic. The majority of participants wanted a more objective portrayal of the past, which chimes with findings elsewhere (Grever et al., Citation2008). The celebratory narrative template of British history was however not being challenged. Several of the participants claimed they ‘policed’ themselves when discussing history with their white counterparts so they did not feel in a position to challenge the dominant narrative. Nor did participants feel teachers, who were predominantly white, or other white students were going to challenge this narrative as it was invisible to them. Participants also felt the story they encountered was enshrined in the National Curriculum, and failed to realize the degree of agency teachers actually have to construct their curriculum (especially outside of examination courses). The professional literature highlights examples of where teachers have developed a different curriculum (e.g. Chaudhry, Citation2021; Lyndon-Cohen, Citation2021), and the latest report from the HA (Burn & Harris, Citation2021) suggests more schools are broadening their history curricula, but the extent to which this is common and the nature of the changes is less clear. Previous research (Harris & Reynolds, Citation2018) has noted a considerable inertia in the history curriculum. And there has been no central government directive to change the curriculum, indeed the current Conservative government, through various media statements, has made it clear that it sees no need for change (Gibb, Citation2021) and is actually resistant to what is perceived to be a ‘woke’ reaction to the history curriculum (Maidment, Citation2021).

Interestingly, the participants held similar views about the value of history in schools. In contrast to earlier studies (Haydn & Harris, Citation2010) which show that students lack a clear, coherent understanding of why they study history, the participants in this study were quite clear that history has a role to play in addressing racism and also promoting stronger mutual understanding amongst different social and cultural groups. For the majority of participants with hyphenated identities, history was valued for its extrinsic societal merits. It was also clear that participants did not want a ‘balance sheet’ approach to learning about topics such as the British Empire. The inadequacies of such an approach have been explained by Benger (Citation2022), as it fundamentally fails to acknowledge the impact and legacy of British rule on those harmed by colonization, and how imperialism has contributed to many modern global and societal global issues. Instead participants advocated a model of history teaching that adopts multiple perspectives, an approach that has hitherto not had much traction in history teaching in England. As noted earlier, the curriculum in England tends to revolve around a disciplinary approach to teaching history, which would involve teaching about different interpretations of the past, but this does not guarantee a range of perspectives will be examined. However an approach that adopts a multiperspectivity approach would ensure that perspectives from different groups would be taught, and could be incorporated into disciplinary ways of teaching history. This would allow history to help pupils ‘see’ the world differently (Lee, Citation1992). It would also require a decolonized approach to history teaching, where subaltern voices are given more prominence.

When exploring the relationship between history and the participants’ sense of identity, it was clear that school history was not seen to be contributing significantly to the varied elements of participants’ hyphenated identity, as engaging with a diverse range of histories in the curriculum was absent. Instead the perception of a celebratory ‘island story’ narrative template seemed to make many participants feel ‘othered’. Clearly, school history is not the only resource people can draw upon to inform their sense of being, but as Barton (Citation2013, p. 103) states:

educators should seek to expand rather than constrict the range of identity resources available to students. Narrowing the range only ensures that school history will play a less important role for students than the alternatives and that it will fail to address the kinds of issues students consider important.

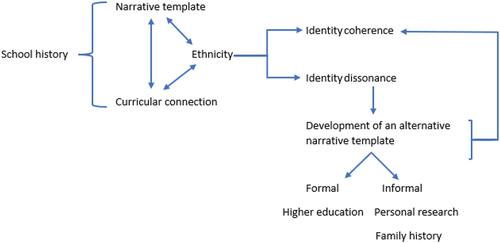

outlines a possible model for understanding this process as encountered by the participants. The relationship between school history and identity formation is mediated by the interplay between the narrative template presented, the connection students make with the curriculum, and the students’ ethnicity, hence its fluidity (Hall, Citation1994). The interaction between these elements helps to determine whether there is an identity coherence or dissonance. If the former, then history helps to affirm a student’s sense of self, but if the latter, then the student is only able to achieve identity coherence via engagement with history outside of school, offering a different narrative. The failure of the curriculum to engage with aspects of participants’ hyphenated identities means many encountered a dissonance, forcing them to look elsewhere to gain a stronger sense of self. This invariably meant that the participants were unable to engage strongly with their British sense of identity. It was the subsequent pursuit of history outside of school, either through personal research or through family stories, that participants were better able to understand themselves as individuals. This appears to be reflected in a stronger sense of attachment to participants’ personal cultural backgrounds, rather than developing ties to any sense of Britishness. Essentially there was not a consensual national story to which many of these participants could connect. As Liu and Hilton (Citation2005) highlight, the absence of an agreed historical representation of the past creates antagonism, which makes it hard for individuals to see themselves as part of an in-group.

This raises clear questions about the purpose and nature of school history. History is often justified as a school subject for its perceived ability to create a sense of identity, framed around a national narrative, and thereby looking to achieve a degree of social cohesion (Harris, Citation2013). The findings in this study would suggest that the failure of school history to adequately support the identities of minoritized ethnic students may only serve to create division within society, rather than bring it together. Governments across the globe use history to create and/or perpetuate particular visions of the national past (Taylor & Guyver, Citation2011), yet as Berger (Citation2007) argues ‘historiographic nationalism has contributed to xenophobia, exclusion, discrimination, violence, war and genocide’ and politicians ought to promote alternative ‘solidarities’. Adopting a multiperspectivity approach to history potentially offers such a ‘solidarity’, as rather than an agreed single narrative, an acceptance of a pluralistic past, with multiple narratives, seems to be something these participants were seeking. However the challenges of a multiperspectivity approach need to be acknowledged. Teachers can find it hard to teach alternative perspectives that fundamentally challenge their own beliefs, especially in post-conflict societies (Zembylas & Kambani, Citation2012), whilst students can find it hard to adopt different perspectives, especially if those perspectives are in conflict with strongly held community beliefs (Barton & McCully, Citation2012; Wertsch, Citation2000). Yet, as Barton and McCully (Citation2010) also show is that young people are able to see and appreciate the perspectives of others. At the very least, it would seem that it is important for students with minoritized ethnicity to encounter a history that is representative of their backgrounds, and for the majority group to become aware of a wider breadth of perspectives that exist. As Lee (Citation1992) has argued, history has the power to change how young people see the world, whilst for Wineburg (Citation2001) history has the power to ‘humanize’ us by coming to know others. Creating a curriculum that has multiperspectivity firmly embedded has the potential to transform our understanding of self and others.

Conclusion

History is clearly an important subject to many of the participants, yet in relation to the first research question asked, the majority of the participants found their experience of school history to be a negative one. Many did not see themselves represented in the past, nor did they encounter a narrative, for example around British colonialism, which they recognized. Consequently, they encountered a dissonance between their sense of self and the narrative they were being taught. In terms of the second research question many participants consciously appeared to use history (or their recollections of what they had learned) at various points in their lives, to examine and (re)configure their sense of self. It was only through their own studies and/or engagement with personal and family histories that most of these young adults were able to affirm their identities. The result was that many felt unable to connect to the ‘British’ element of their hyphenated identity. It would be worthwhile, echoing Barton’s (Citation2013) call, to do further research to explore more precisely how history, both in and out of school impacts on adolescent identity development and whether there are significant epiphanies. This current study suggests that far from being reconciled to a history of Britain, many felt a stronger alignment with their cultural and minoritized ethnic background, and were essentially disconnected to any strong sense of a British heritage. This should be a matter of concern given school history, as experienced by the participants in this study, seems to be a potential source of division rather than cohesion. There ought to be a focus on how the curriculum could be modified to present the multiple perspectives that reflect a history, in which all groups feel a connection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Throughout the article we refer to people from minoritized ethnic groups, adopting Gunaratnam’s (Citation2003) use of the term, which reflects the way in which people are actively minoritized by others.

2. ‘Our Island Story’ was a book published for young children by Henrietta Marshall in 1905 and presents a triumphant and heroic view of Britain and its past. It was a term used by Michael Gove, the Secretary of State for Education 2010–2014 to describe the type of history he wanted students to encounter in school.

References

- Abbey, D., & Wansink, B. G. J. (2022). Brokers of multiperspectivity in history education in post-conflict societies. Journal of Peace Education, 19(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2022.2051002

- Angier, K. (2017). In search of historical consciousness: An investigation into young South Africans’ knowledge and understanding of ‘their’ national histories. London Review of Education, 15(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.15.2.03

- Arday, J. (2020). The black curriculum: Black British history in the National Curriculum report 2020 The Black Curriculum.

- Barton, K. (2013). School history as a resource for constructing identities: Implications of research from the United States, Northern Ireland and New Zealand. In M. Carretero, M. Asensio, & M. Rodríguez-Moneo (Eds.), History education and the construction of national identities (pp. 93–108). Information Age Publishing.

- Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barton, K., & McCully, A. (2010). “You can form your own point of view”: Internally persuasive discourse in Northern Ireland students’ encounters with history. Teachers College Record, 112(1), 142–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811011200102

- Barton, K., & McCully, A. (2012). Trying to “see things differently”: Northern Ireland students’ struggle to understand alternative historical perspectives. Theory & Research in Social Education, 40(4), 371–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.710928

- Benger, A. (2022). Beyond the balance sheet: Navigating the ‘imperial history wars’ when planning and teaching about the British Empire. Teaching History, 187, 8–19.

- Berger, S. (2007). History and national identity: Why they should remain divorced. History and Policy. https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/history-and-national-identity-why-they-should-remain-divorced

- Bertossi, C., Duyvendak, J., & Foner, N. (2021). Past in the present: Migration and the uses of history in the contemporary era. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(18), 4155–4171. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1812275

- Bhopal, K. (2018). White privilege: The myth of a post-racial society. Policy Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis : A practical guide. Sage.

- Burn, K., & Harris, R. (2021). Historical association survey of history in schools in England 2021. Historical Association.https://www.history.org.uk/secondary/categories/409/news/4014/historical-association-secondary-survey-2021

- Chaudhry, A. (2021). In pursuit of shared histories: Uncovering Islamic history in the secondary classroom. Teaching History, 183, 72–83.

- Chen, J., Lau, C., Tapanya, S., & Cameron, C. (2012). Identities as protective processes: Socio-ecological perspectives on youth resilience. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(6), 761–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.677815

- DfES. (2007) . Diversity and citizenship curriculum review.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of black folk. A.C. McClurg & Co.

- Epstein, T. (2009). Interpreting national history. Routledge.

- Foster, S. (2011). Dominant traditions in international textbook research and revision. Education Inquiry, 2(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v2i1.21959

- Gibb, N. (2021, April 21). Letter to Catherine McKinnell MP and Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5675/documents/55882/default/

- Goldberg, T. (2013). “It’s in my veins”: Identity and disciplinary practice in students’ discussions of a historical issue. Theory & Research in Social Education, 41(1), 33–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.757265

- Grever, M., Haydn, T., & Ribbens, K. (2008). Identity and school history: The perspectives of young people from the Netherlands and England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00396.x

- Gunaratnam, Y. (2003). Researching ‘race’ and ethnicity. SAGE.

- Hall, S. (1994). Cultural identity and diaspora. In P. Williams & L. Chrisman (Eds.), Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory (pp. 392–403). Routledge.

- Harris, R. (2013). The place of diversity within history and the challenge of policy and curriculum. Oxford Review of Education, 39(3), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.810551

- Harris, R., & Reynolds, R. (2014). The history curriculum and its personal connection to students from minority ethnic backgrounds. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(4), 464–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.881925

- Harris, R., & Reynolds, R. (2018). Exploring teachers’ curriculum decision making: Insights from history education. Oxford Review of Education, 44(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1352498

- Haydn, T., & Harris, R. (2010). Pupil perspectives on the purposes and benefits of studying history in high school: A view from the UK. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 42(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270903403189

- Historical Association. (2019). What’s the wisdom on … Interpretations of the past. Teaching History, 177, 23–27.

- Huber, J., & Kitson, A. (2020). An exploration of the role of ethnic identity in students’ construction of ‘British stories’. The Curriculum Journal, 31(3), 454–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.23

- Jenrick, R. (2021). We will save our history from woke militants. Daily Telegraph 16 Jan 2021 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/01/16/will-save-britains-statues-woke-militants-want-censor-past/

- Lee, P. (1992). History in schools: Aims, purposes and approaches. A reply to John White. In P. Lee, J. Slater, P. Walsh, & J. White (Eds.), The aims of school history: The national curriculum and beyond (pp. 20–34). Tufnell Press.

- Lévesque, S. (2017). History as a ‘GPS’: On the uses of historical narrative for French Canadian students’ life orientation and identity. London Review of Education, 15(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.15.2.07

- Lidher, S., McIntosh, M., & Alexander, C. (2021). Our migration story: History, the national curriculum, and re-narrating the British nation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(18), 4221–4237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1812279

- Liu, J. H., & Hilton, D. (2005). How the past weighs on the present: Social representations of history and their role in identity politics. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(4), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X27162

- Liu, J. H., & László, J. (2007). A narrative theory of history and identity. In G. Moloney & I. Walker (Eds.), Social representations and identity (pp. 85–107). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lyndon-Cohen, D. (2021). Decolonise, don’t diversify: Enabling a paradigm shift in the key stage 3 history curriculum. Teaching History, 183, 50–57.

- Maidment, J. (2021, Dec 8). ‘It is time to be proud of who we are’: Foreign secretary Liz Truss warns ‘woke’ attacks on the UK’s past and culture are a gift to Britain’s enemies as she says the nation should embrace ‘our history, warts and all’. Daily Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10287385/Liz-Truss-warns-against-woke-attacks-UKs-history-culture.html

- Moncrieffe, M., Race, R., & Harris, R. (2020). Decolonising the curriculum. Research Intelligence, 142, 9.

- Peck, C. (2010). “It’s not like [I’m] Chinese and Canadian. I am in between”: Ethnicity and students’ conceptions of historical significance. Theory & Research in Social Education, 38(4), 574–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2010.10473440

- Peck, C. (2018). Intersections of students’ ethnic identifications and understandings of history. In T. Epstein & C. Peck (Eds.), Teaching and learning difficult histories in international; contexts (pp. 231–246). Routledge.

- Radhakrishnan, R. (1996). Diasporic meditations: Between home and location. UOM Press.

- Raghunandan, K. (2012). Hyphenated identities: Negotiating ‘Indianness’ and being Indo-Trinidadian. Caribbean Review of GenderStudies, 6, 1–19.

- Rodeiro, C. L. V. 2009. Uptake of GCSE and A-level subjects in England by ethnic group 2007. Statistics Report Series. No. 11. Cambridge Assessment.

- Royal Historical Society. (2018). Race, ethnicity and equality in UK history: A report and resource for change. RHS.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd edn ed.). Sage.

- Savenije, G., van Boxtel, C., & Grever, M. (2014). Learning about sensitive history: “heritage” of slavery as a resource. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(4), 516–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2014.966877

- Schachter, E. P. (2005). Context and identity formation: A theoretical analysis and a case study. Journal of Adolescence Research, 20(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558405275172

- Smith, B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qualitative Research in Sport. Exercise and Health, 10(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Taylor, T., & Guyver, R. (Eds.). (2011). History wars and the classroom – global perspectives. Information Age Publishing.

- Wertsch, J. (2000). Is it possible to teach beliefs, as well as knowledge about history? In P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history (pp. 38–50). New York University Press.

- Wertsch, J. (2002). Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press.

- Wertsch, J. (2008). Collective memory and narrative templates. Social Research, 75(1), 133–156. 2008. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/527987

- Wilkinson, M. (2014). Helping Muslim boys succeed: The case for history education. The Curriculum Journal, 25(3), 396–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.929527

- Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. Temple Press.

- Zembylas, M., & Kambani, F. (2012). The teaching of controversial issues during elementary-level instruction: Greek-Cypriot teachers’ perceptions and emotions. Theory & Research in Social Education, 40(2), 107–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.670591