ABSTRACT

This article aims to undertake a comparative investigation of school administration to understand further the frames of curriculum making. School administration is an under-illuminated aspect of curriculum research. The paper commences from the notion that, in mass education, a school system is operationalized by many schools, which are coupled to each other and to political decisions. Here is the curriculum vital. Building on the classic work of Stefan Hopmann, a curriculum is part of the administrational structure of the school system. The Article suggests several categories that can describe the nature and function of school administration in various contexts. There are external matters of schooling, such as school buildings, school food, etc. and internal matters of schooling, such as curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation. Individual schools and school administration are coupled via licences, and programmatic, professional, and procedural supervision. The article employs these categories with a comparison of a decentralized Sweden and a centralized Germany. The comparison investigated 290 Swedish municipality school administrations and 45 state education authorities in 4 German federal states. In this comparison many interesting similarities between both contexts can be hightligthed.

Introduction

There is a vast body of literature on the effects of such decentralization and accountability reforms in school systems across the Western world (Altrichter & Maag Merki, Citation2016; Proitz et al., Citation2017). There have also been numerous prominent efforts to explain what these changes mean for schools in practice, as well as the nature of curriculum making (Hopmann, Citation2003). It is almost common sense among scholars in curriculum research that the path from curriculum making as national policy practice to curriculum making as practice of schools is not linear, but rather characterized by translation, implementation and autonomy gaps (Ball, Citation2003; Proitz et al., Citation2023). It is also highly affected by contextual factors (Schulte & Wermke, Citation2019).

When we see curriculum making and evaluation as a nexus between education policy and education practice (Proitz et al., Citation2023), it has also been pessimistically portrayed, with claims that curriculum reforms are more important for politicking than policy-making (Kauko et al., Citation2018). In this line of thought, reforms are self-referential activities within the political system (Luhmann, Citation2002), which are, however, only loosely coupled to the pragmatic level in schools and classrooms (Schulte, Citation2018; Weick, Citation1976). The practice, or ‘grammar’ of schooling often remains immune to many of the changes (Hopmann, Citation2015). More positively described, the curriculum, as also other education policies, is enacted by the school professionals (Ball, Citation2003) or recontextualized (Fend, Citation2008). In other words, the practical process of curriculum making is an interpretation done at various levels, always attributed to a certain amount of autonomy (Wermke & Salokangas, Citation2021).

What is often under-illuminated in such empirical and conceptual considerations concerning the levelled nature of the curriculum is how mass education is organized in detail (Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2023), looking at what issue of schooling at scale must be organized and how these are organized. This would, for example, relate to whether decentralized school systems do actually provide a diversity of school organizations, or if we can simply observe more of the same. With this, we can learn more about the frames of curriculum making for policy and practice. This perspective shifts the focus in curriculum research towards the investigation of school administration, or the making of school organizations at scale. Following the rationale of Kuper (Citation2020), this approach would focus less on schools as independent organizations, instead understanding them as components in an overall organization that includes all schools in a school system. Consequently, school administration means the organization of many schools within the same (national) school system.

From this perspective, all schools are, in principle, bound by the decisions of parliaments. The curriculum is such a decision. However, the idea of a continuous chain of legitimacy, which links every action in the school to a parliamentary process, is indeed restricted, as we have discussed earlier. For reasons of practicability, the transformation must take place in a model with which the planning and implementation responsibilities of the actors in the system are secured. This would be the very nature of the administration of all schools in the system. Consequently, when discussing education policy trends in international contexts, we must understand the universalities and particularities of school administration better. This is the purpose of this article. We aim to examine the organization of public administration from a comparative perspective in order to understand variations in and factors behind the structuring of school administration. We will suggest categories that can describe the structures of school administration in various contexts, both decentralized and centralized. In doing so, we aim to make a contribution to curriculum research, as we argue that school administration is a conditio sine qua non of curriculum making.

The paper commences from the notion that, in mass education, a school system is operationalized by many schools, which are coupled to each other and to political decisions. Building on the classic work of Stefan Hopmann (Citation1988), curriculum work is also administrational activity. There are very few comparative studies of school administration. The few that exist, are very much related to curriculum research. Still, the early work of Hopmann and Haft (Citation1990), and the later work of Fries et al. (Citation2013) shows how fertile such comparisons can be, as they reveal nation-specific constitutional mindsets, i.e. ways of understanding variations in public education structures in light of their overall administration. Hopmann defines constitutional mindsets as ‘the well-established, basic social patterns of the understanding of schooling that have sedimented in the respective traditions’ (Hopmann, Citation2015, p. 18). In particular, the early work of Hopmann (Citation1988) has inspired our work. In his study on curriculum making as an administrative action (Lehrplanarbeit als Verwaltungshandeln), he was able, in the case of Germany, to show how stability and continuity of school systems are organized by organizational means. He was also able to show how education administration has been shaped over time, built upon and participating in the emergence of stable mindsets. This early work, also due to its socio-historical theoretical character, remains very valid.

Our comparative work builds on the cases of Sweden and Germany. Sweden and Germany are fascinating to compare, since both represent two opposing education policy governance examples on the centralization and decentralization continuum, related to paradigms of input versus output controlling (Wermke & Salokangas, Citation2021). Sweden since the 1990s has undergone stringent educational reforms that have decentralized a formerly very centralized education system by way of a radical push of responsibilities onto municipalities and independent school owners. However, the last decade has been characterized by re-centralization, related to the return of strong state steering (Rönnberg, Citation2012). Germany, particularly at the state level (Germany is a federation of states), presents a traditionally centralized and uniform system, with a strong central state administration, even if there is today a shift towards greater decentralization, implementation of national examinations, and low stakes school inspections. This is valid for teachers’ employment, curriculum-making, and national examination. The physical materials of schooling, such as buildings, equipment, etc. are firmly in the hands of the municipalities.

The article is structured in the following way: First, we present our understanding of school administration, with its bureaucratic nature, as the way to make mass education work. In this section, we will also elaborate on several analytical categories that can support us in describing school administration in various temporal and spatial configurations. Robust descriptive categories are essential for comparing multiple solutions for organizing mass education. We then present both our comparative methodological approach and our empirical material. The results section is structured into two parts. First, we provide analyses of the Swedish and German school organizations by employing the analytical categories from our section on the nature of school administration as the facilitator of mass education. Here, we will see differences, but also significant similarities. In the second part of the results section, we will see that the structures within the two national school systems’ decentralized and centralized school administrations also are characterized by more similarities than differences. Finally, in the discussion section, we will discuss our findings as a complement to comparative studies on curriculum making across time and space.

School administration: enabling change and stability in school systems

School administration as bureaucracy

We argue, in line with other researchers (such as Hopmann, Citation1988; Kuper, Citation2020; Ohlhaver, Citation2005), that Weber’s ideal type of bureaucratic organization is highly valuable in understanding several public education relations, such as between the school administration and the individual school. From this perspective, the term ‘organization’ states that the phenomenon in focus has an organizational purpose. There is a division of labour and a division of power. There is a line of authority between one or several centres of power and an operational core. These various lines must be coordinated and controlled. There are even systems and standards for recruiting organizational members, salary schemes, and regulations for potential sanctioning. These definitions lead us further to the idea of bureaucracy as the backbone of school administration.

The central characteristics of a bureaucracy are pronounced in this relationship. School administrators, such as superintendents, represent an organizational focal point for the schools, represented by principals. The relationship is structured in an accentuated, hierarchical manner. In his classic essay on economy and bureaucracy (1914/1980), Max Weber puts forward the following characteristics of bureaucratic structures: Administration by formal documents; regulated competencies; administration through learnable/comprehensive rules; administrative hierarchies and lines of authority. Finally, the full-time administration position requires specific, subject-based education and training. Another factor is that the nature of bureaucracy must always be understood in the context of its particular environment, which is contingent and dynamic, at least in terms of its claims (the validity of its decisions for the society), its legitimation, and its patterns of power. Legitimacy (of authority) can come from tradition, charisma, competency, or legality, which are context dependent. Authority thus results in both power and autonomy (Ohlhaver, Citation2005).

The development of school systems relates to negotiations of interests, on the one hand, and focal ideas on necessary structures (such as obligatory schooling, years, subjects etc.) on the other. This necessitates systems of coordination, governing, and control. A compulsory school system must assure compatibility, permeability, and social justice. There must be a rationale for schooling that secures cooperative relations between students and teachers to educate, socialize, and distribute life chances to students (Ohlhaver, Citation2005). This must be sustainable and stable. Educational tracks cannot change on short notice. Assessment must have and keep a specific meaning and value.

Couplings and licences in school administration

Concerning our earlier considerations, the purpose of school administration is securing a) the dynamics of a school system which underpin instruction as a pedagogical institution, b) the transmission of specific knowledge (such as mathematics, language, etc.), c) the education of the youth towards particular essential qualifications, such as social competence, communication competence, teamwork, media/methodological competence, problem solving, planning/project management competence, and so forth (Hopmann, Citation1988, still valid today).

Consequently, the school administration’s core purpose is to operationalize the curriculum from a perspective of change and sustainability. Given these premises, how should school administration be organized? The school administration must build on both didactical/pedagogical and bureaucratic competencies. Hopmann (Citation1988) called this bureau-didactics. There must exist systematic legitimation and examination procedures that enable the connection of schools and school types (e.g. primary, secondary, and upper secondary schools) with each other, and thereby enable the division of labour and the control of schools’ ‘performance’. The existence of a legitimate, controlled/appealable selection or differentiation of student performance is necessary. A coherent system of teacher education and teacher recruitment is required. There must be appropriate places for instruction, school buildings and classrooms, and these must have adequate facilities and equipment. Each student must have an allotted space for the time in which education is planned—during the day and within the students’ biographies. Schools must also ensure that each student can be transported to the school.

In practice, it is very complex and difficult to deal with the size of the school system and the differentiated nature of everyday life in its intricacies. For reasons of practicality, the transformation must consequently take place in a model that delegates planning and implementation responsibilities to various actors within the system (Kuper, Citation2020). This is why the state attributes a specific amount of autonomy to various units in an education system. To a certain degree, the state must also supervise how discretion is applied and whether particular goals have been achieved. It must provide support and consultations and take responsibility for significant frames of the practice of subordinate units (ibid).

This leads our attention to how the units are coupled. First of all, they are coupled through decisions (Kuper, Citation2020; Luhmann, Citation2000). The unique feature of communication in the medium of decisions lies in the concentration of attention on decisions made from a spectrum of alternative possibilities. Communication in the medium of decisions allows for the organization of communication such that decisions set guidelines for subsequent decisions.

‘Decisions to be made in education are many, e.g. grading of students, the decisions surrounding a pedagogical profile, the existence of different school types, and the choice of instructional method or material are only a handful of the significant decisions to be made. These decisions are contingent, so the option of making a specific decision before another must be motivated. Communication in the medium of decision-making is an attribution of responsibility to the respective decision-makers in an organization. In detail, there is regulation of what school principals decide, what school supervisors decide, and what individual teachers decide. Even students and their parents must be taken into account in some decisions’. (Kuper, Citation2020, p. 88, our translation)

These guidelines can concern what Luhmann (Citation2000) called decision-making premises. This term is significant because it considers how an organization sets the conditions for its decisions through higher-level decision-making. Luhmann distinguishes three possibilities for organizations to bind themselves in pending decisions to preceding decisions: They can decide on programmes that will be implemented in subsequent decisions; They can decide on personnel decisions, which are linked to the allocation of more or less concrete task spectrums and expectations of competence; Finally, decisions can determine the procedures through which processes are to be handled.

Superior (school administration authorities) and subordinate units (schools) are consequently coupled insofar as the first provides the decision-making premises for the latter. The first provides room for manoeuvre. This also leads us to the question of just how autonomous schools or lower units of school authority can be. Kuper (Citation2020) and Rürup (Citation2020) (both in reference to Avenarius, Citation2010), argue that, from a legal point of view, the term ‘autonomy’ does not adequately characterize the relationship of the individual school to the school supervisory authorities. In a legal sense, a unit is autonomous when it is empowered to manage its affairs through the power to regulate the law by issuing legal norms (statutes). However, schools do not have this authority. They are, legally speaking, ‘institutions without legal capacity’. Consequently, their relationship with the administration is rather one of increased self-responsibility. Both legally, and in terms of organizational theory, these vague terms do not reflect a concrete administrative relationship between the management of a school and its supervision. The relationship initially remains underdetermined and is thus dependent on interpretation (Kuper, Citation2020, p. 89).

Considering this relation, Hopmann (Citation1988) suggests the concept of licencing as a coupling mechanism, as it regulates the coordination and degrees of freedom of various sub-systems. Licences are the hinges between differentiated parts within the same context. In Hopmann’s terms, licencing is the certification to be allowed to do something with a particular autonomy, as long as established rules and regulations are followed. However, the rules do not define the details of the actions to be taken. Hopmann (Citation1988) explains this with the classic example of a driver’s licence. Driver’s licences and traffic codes and regulations, not unlike the teacher exam and the state curriculum, prescribe that the traffic participant must adhere to several conditions of participation, but not where they have to drive, or how they have to teach. Moreover, the authority that allocates the licence is not liable for any misbehaviour of the licenced person. The question will always be: Was the person who erred licenced, and did they follow the licencing conditions?

Hopmann (Citation1988) argues that in school administration, licencing is a fertile instrument for administratively and legally standardizing particular actions without the tremendous transfer costs related to the governance of the very complex dynamics involved in education processes (see above), and without the administration being held to account for all failures. Licencing is consequently a strategy of governance at a distance (for example by decentralized organizations). Licencing is a bureaucratic action that replaces control over individual decisions and their consequences with the formulation of premises of preparation, process, and evaluation of action. Licences are built on the existence of particular procedures. As long as an action can be related to a certain procedure, the action can be assumed to be approved. The procedure can then be filled with a variety of subject matter.

As a complement to the concept of licence in loosely coupled school systems, we suggest the term ‘supervision’, as it describes the role of the licence ‘provider’: namely, control as well as support. This is encapsulated in the German term ‘Aufsicht’. Supervision, the usual English translation for this term, comes from the noun ‘to supervise’ and refers, according to the Oxford dictionary, to observing and directing the execution of a task, an activity, or a person. It unites the actions of controlling and consulting. Both are related to each other in a complementary way. Both are strategies to maintain the coupling of two units that are hierarchically associated. Less of the first dimension would mean more of the other, and vice versa (Kuper, Citation2020; Mintzberg, Citation1979).

The subjects of supervision and licencing

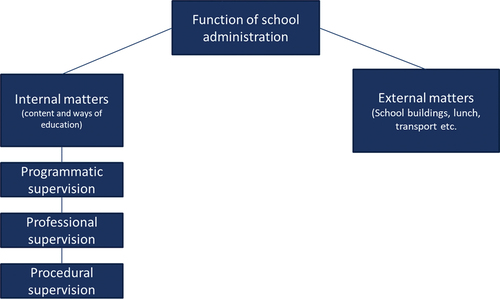

After discussing the form and nature of school administration (in terms of its couplings by licences), it remains to be clarified again: What is the subject of regulation in a school administration? Here, the German literature on school organization and public administration (Bogumil, Citation2017; Bogumil & Ebinger, Citation2019) provides very useful categories for description, even of other school systems. Applying Luhmann’s rationale of decision-making and decision-making premises, we will further utilize the following categories:

External matters concern the school buildings and their interiors, learning technologies, school transport, and school lunches. In sum, the artefacts of schooling. Financed by tax revenue, the municipalities often handle such issues via earmarked funding. The state can support some development, for example, of digitalization or barrier-free schooling.

Internal matters concern the content and frames of education. These include curricula (including assessment questions), teachers’ work and education, and school laws. The state often regulates such matters, i.e. as legislated by the parliament, executed by the government and its authorities, and enforced by the judicial system.

Decision-making in internal matters of schooling couples schools and school administrations through three types of supervision:

2.1 Programmatic supervision concerns the content and aims of schooling (including assessment questions): What is functional in the school; Does the school follow its designated purpose?

2.2Professional supervision concerns teachers’ and principals’ work and professional behaviour: do school professionals know what they are expected to do? Do they have the right qualifications? How are they ‘paid’, and for which positions and which tasks?

2.3 Procedural supervision concerns the legal framing of schools: Do the schools provide the education the pupils have a right to, in the right way?

Methodology: comparing local school administration

In our study, we employ a comparative approach which will enable us to illuminate the relation of practices in inclusive schools and various context-specific particularities. The latter can change over time and differ across locations. Contingency is a well-trodden concept in the humanities and social sciences, and here we can only present part of the existing scholarly work to define the term theoretically. A common-sense definition is that something might have unfolded differently or take some other form. Contingency means not simply infinite possibilities but a specified infinity in which something is neither necessary nor impossible, but is a natural alternative. Contingency is about understanding available options, facilitating understanding of the complex possibility structures, and the fluid construction of this reasoning (Kauko & Wermke, Citation2018). Contingency thus becomes visible through an awareness of other possibilities that are genuine alternatives. These genuine alternatives can be related to certain contextual particularities, or, in the words of Mintzberg (Citation1979), ‘contingency factors’. Different or similar ways to solve a particular problem, in relation to varying contextual conditions constitute a device for theorizing on the nature of a phenomenon. Simply put, similarities might point to universal traits, and differences to context-dependent particular traits. This requires an investigation of the specific and complex systems of interrelation and interaction within the specific cases (Schriewer, Citation1999), in which both time and space are important dimensions.

Inspired by the work of Luhmann, Schriewer’s (Citation1999) comparison therefore provides a follow up of several analytical steps containing ‘generalization’ and ‘respecification’, meaning firstly an ‘act of establishing general terms and secondly eliminating different alternatives of these in concrete settings’. The generalizing operation is closely connected to a profound knowledge of the ‘subject area’ of interest and thereby determines which alternatives are possible, or in other words which options from the general cause-effect chain exist and are able to be investigated. This process is indeed highly theory-oriented. The ‘specificative operation’ examines the general relations and possible options among the constraints of the particular context. However, ‘a conditional analysis of this kind may in turn embrace two perspectives. It can emphasize, firstly, the decisions taken in favour of particular solutions and, by the same token, against other problem solutions. It can also focus, then, on the consequences, and follow-up problems resulting from such decisions’. (ibid, p. 59). Here, time and space are relevant for our understanding. The investigation of different configurations which lead to different patterns requires an historical perspective. This means that the explanation of the particular emergence of certain phenomena should be sought in historical developments which made a particular configuration possible while preventing another (ibid.).

Our analyses commenced from formal descriptions of both national school administrations. Building on the particular education act, responsibilities and relations are described. In other words, descriptive context descriptions are the empirical material for our first comparisons, as presented in or analyses of the structures of the contexts.

Secondly, we collected organizational descriptions of all municipalities’ school administrations in Sweden (n = 290) between May and December of 2022. This was carried out by writing an email to the municipality, and asking for either an organizational flowchart or a written description of roles and relations in the respective organization. Due to the principle of public access to information in the Swedish case, public authorities (in states and municipalities) must always give access to documents concerning their practice to provide citizens with the greatest possible transparency. In other words, the municipalities were obliged to answer our request and make their organization transparent. The size of municipalities in Sweden differs significantly. Therefore, we sorted the descriptions into three groups, following the Swedish authority of statistical categories, distinguishing between metropolitan areas, e.g. big cities and their sub-municipalities, (more minor) urban regions, bigger towns and their sub-municipalities, and rural regions, using the classification of Swedish Statistics.

In the German case, we chose four of 16 federal states, including their state school authorities. Each of the authorities has a webpage on which we were able to find either an organizational flowchart or, more often, a very detailed contact list with all positions and respective contact details. As described in the context of Germany, the local school authorities are federal and state authorities. We collected from the Internet data concerning the positions in all local state school authorities in three states in Germany, two from West Germany (Hesse and Baden Württemberg) and two from the East (Thuringia and Brandenburg). As illustrated, municipal school administrations are responsible for the school buildings, school food, and school transport. Here, analysing an organizational structure at scale was not possible. Such information is not public access material, as it is in the Swedish case. A systematic overview through municipality websites was also not possible.

We analysed the descriptions by quantitative content analyses carried out in MS Excel. We counted the positions in the organizations and their frequency in the respective authority organization. This has consequences for our analytical ambitions. Our results, though mostly at scale, are mainly descriptive. For both countries, there are different data sources and contexts. We aim to present for each case a somewhat average local school administration. These will be compared to enable the identification of empirically grounded universalities and national particularities. After collecting the information by email or web research, we commenced on the qualitative part of our work. The information reported from the municipalities had various forms, some being organizational flow charts, others being telephone lists related to specific areas, or just plain descriptions of the organization of the school administration. However, the most significant difference in the material was what we were able to collect from Sweden and Germany. While we could gain a detailed picture from the local school authority offices in Germany, we needed help finding systematic information from the municipalities. From the German school authorities, we know in reasonable detail how many positions are attributed to specific tasks, but such information was only seldom available in the Swedish case. These particularities in our data have consequences for our findings and theoretical ambitions. For the Swedish material, we can present how many of the 290 municipalities have a particular focus area in their school administration. For the German material, presented by four federal states, we can even ascertain the size of the focus areas relative to the total size of all areas.

Although we try to present average school administrations from a depiction of all Swedish municipalities’ and four German länders’ state school administrations, our focus in this paper is not a generalization in a statistical sense. Consequently, we have not undertaken any significance analyses. Due to this partly varying nature of both the national material, including also the eventual biases in self-description and subjectivity in our coding, the conditions of such statistical analyses would be prejudiced. We instead aim to contribute to analytical generalization, i.e. theorizing on the nature of school administration by using a comparative approach. Consequently, we first of all look at the relations of each of the various tasks and positions to each other. Which task areas in the authority are the biggest, or how do their respective sizes relate to one another? This can reveal what is seen as relevant for school administrations in different national contexts. Nevertheless, we aim to use data at a certain scale in order to increase the validity, coherence and plausibility of our analyses. Therefore, we tried to collect information from all available local state authority offices (Germany) and municipality school administrations (Sweden).

School administration in contexts: couplings by decisions, decision premises, and decision supervision

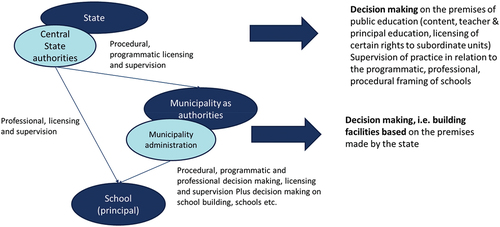

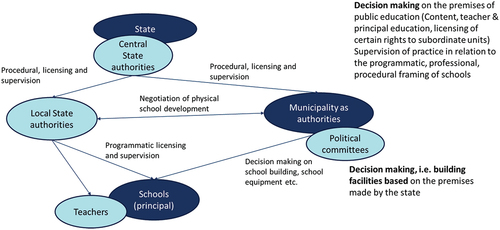

In this section, we will use our categories to describe both school systems’ school administrations. The material for this takes the form of descriptives, which we present by using our categories. We were able to describe the German system as depicted in , and the Swedish in .

In Germany, each federal state has various levels of school administration (education is a federal state matter), headed by the first level, the Ministry of Education (Kultusministerium). School administration or school authority (Schulaufsicht) refers to the state’s sovereignty regarding the school system’s organization, planning, steering, and control. Consequently, a school administration is allowed to make regulations regarding schooling (below the education law level, which must go via the parliament). Federal state constitutions regulate the general matter/basic questions of instruction: e.g. in Bavaria, the individual rights of citizens for education are stated, compulsory schooling, aims of public education, function and structure of school administration, ownership of schools (Schulträger), the position of teachers in the state, private schools as well as the role of religious education. The operationalization of the constitution is the school law. The parliament constitutes the school administration through its law and budget, functions of state, and the ministry of education by its various levels of administration.

Through regulations (Verordnungen), school administration is quite dynamic and can solve particular problems in some depth. Regulations that the school administration can enact below the constitutional law handed down by the parliament are a fairly effective tools. When Ohlhaver (Citation2005) analyses the number and scope of administrational regulations in various federal states, he sees similar structures: Curricular matters are one area, and a share relates to the structure of schooling in relation to equity and equality (in terms of recourses of a different type). Another area relates to assessment and examination. Finally, there is a part related to custodial aspects of schooling, security, hygiene, etc. Some, however few, aspects deal with teacher cooperation, instruction, professional development, etc.

In Sweden, as in the German länders, all public power stems from the people. The Parliament is the highest legislative power. The Parliament decides on laws, government revenue (taxes), and expenditures. It also scrutinizes and controls the work of the government and its agencies. There are authorities (myndigheter); these authorities must do what the Parliament and the Government have decided. In Sweden, there are five agencies responsible for school work. The two most significant are the Swedish National Agency of Education (Skolverket), which is responsible for the governance of schooling by making national curricula, working with standards for teacher education, and teachers’ professional development. It funds national school improvement projects. Simply put, it is responsible for the internal matters of schooling. The other is the Swedish School Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen), which controls whether schools, municipalities, and private school owners follow the Education Act and national curriculum.

There are many similarities, as well as differences, between the national solutions concerning the organization of mass education through school administration: First and foremost, the overall power over public education is held by the state in both national contexts. The state decides on the decision-making premises of schooling, the limits of practice, the conditions of the licence, and the programme of schooling (curriculum, pedagogy, evaluation (Bernstein, Citation1977)). In both national contexts, the municipalities make decisions about school buildings, equipment, transport, and lunches, i.e. the material frames of education. On the other hand, the municipal policy committees have little impact on the internal matters of schooling. The administration operationalizes political decision-making but is licenced by the state. The same is true for the principals, who are supervised by school administrators. In both systems, school supervision intervenes in school practice only in cases of extreme jeopardy to the principles of lawfulness and purposefulness.

In terms of differences, we can see that in Sweden, municipalities are granted much more leeway in school administration by the state, due to the system’s decentralized governance, even for the internal matters of schooling. In Sweden, school financing through student vouchers provides parents and students more rights. Even the independent school sector is much bigger and less regulated, which is simultaneously a challenge and an opportunity for municipalities. However, a greater number of stakeholders has contributed to fragmentation, while degrees of freedom have been restricted by top-down bureaucratizing and standardization. This nudged the Swedish system towards the German model, which had been similar in Sweden until the 1990s. Alongside the municipalities, local school authorities also existed, with similar functions to their current German counterparts (Länsskolnämnder). This kind of organization has been partly re-implemented into the Swedish system by establishing several local offices of the National Agency of Education (Skolverket) (Swedish National Agency of Education SNAE, Citation2022).

Inside school administration: positions and tasks

Germany has a federal structure of 16 federate states. All states have a specific system of school supervisory authorities, whereby the organization of the institutions, the school-specific responsibilities, or the allocation to the other Land administration is regulated with some variance. In summary, there are three different alternatives: systems consisting of one tier, or of two, or even three tiers.

This results in the following alternatives among school administrations:

Three-tier model: 1st tier: ministry/state department of education − 2nd tier: state school authorities in regions/counties − 3rd tier: state school authorities offices responsible for several municipalities. This model is found in Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, and North Rhine-Westphalia.

A Two-tier model comprises again in the first tier, the Ministry/state department of Education, and in the second tier, local state school authorities. This model is found in nine Länder: Brandenburg, Hesse, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Lower Saxony, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig- Holstein, and Thuringia.

Four Länder have only one supreme school supervisory authority (ministry): Berlin, Bremen, Hamburg, and Saarland (Bogumil Citation2015).

When relating the three types to demographic particularities, the variances which emerge can be explained quite reasonably by the relative size of the states. Big states have a three-tier structure, both in geographical size and number of inhabitants (such as Baden Württemberg and Bavaria). Very small Länder, such as Hamburg or Saarland, have only one tier. This indicates that administrations also need a certain number of individuals and schools under their responsibility. The most common solution is a two-tier structure. With the re-unification of Germany in 1990, five new States were included within Germany’s national borders (states such as Brandenburg and Thuringia). These states’ school administrations were (re-)built simultaneously at around this time; therefore, they are quite alike in terms of the structures of their two-tier systems (Ohlhaver, Citation2005).

In the analyses of the German data, we present four categories: Professional and programmatic supervision and support, Special educational/psychological support, Organization, and Office management and participation committees. Taken together with the categories we put forward earlier, we see that programmatic (content and aims of schooling) and professional (concerning the work and professional behaviour of educational staff) are intertwined, i.e. executed by similar positions. Teachers have their direct superiors in such positions. As described above, external matters of schooling, as related to school buildings, classroom equipment, school lunches, school transport are responsibilities of the municipalities. However, the state offices have employer responsibilities and all related organizational responsibilities, from recruitment, contractual issues, health schemes to representation of the employees’ rights. Thirdly, special education and school psychological services are a main task of the school administration, including diagnostics, provision of special support to schools, support of students, teachers, parents etc. Finally, the head of office team and the internal office support is of significance, consisting of the organization of the administration, from the head to the post office to the facility management and management of the building.

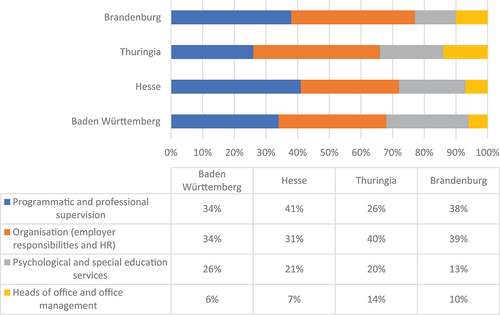

In , the kinds of responsibilities are classed into the four categories.

Table 1. Main and subordinate focus areas in the German case.

In , we depict the distribution of positions across all local school authority offices in four German states, drawing on the information provided on the offices’ web pages by telephone lists, organizational flow charts, and lists of supervisory areas. We present the shares of the areas in relation to the overall organization as manifested in the website descriptions.

26-40 % of positions reported concern the supervision of programmatic and professional supervision, that is, monitoring

31-40% of positions reported concern organizational matters and support, due to the division of labour in the German system (see above), are those matters limited to employer responsibilities and HR issues.

13-26 % of positions reported concern student health and special education services (in Brandenburg, only psychological matters, therefore ‘only’ 13%.)

6-14 % of positions reported concern heads of office and internal office management.

Diagram 1. share of focus areas in local school authority offices (Staatliche Schulämter), Brandenburg (N = 344 in 4 offices), Thuringia (N = 483, in 5 offices), Hesse (N = 1270, in 15 offices), and Baden Württemberg (N = 1036, in 21 offices). N refers to the positions that could be unambiguously categorized). In Brandenburg, the processing of special education needs diagnosis and provision is no longer the task of the local school authority offices, but is instead managed by the municipalities in cooperation with the state school authority offices.

Drawing on our coding, we see, in particular, similarities between the four different states of our German case, which might provide evidence for an argument that promotes the stability of bureaucratic structures and the limited degrees of freedom in them. In all three cases, the greatest shares are found in programmatic and professional supervision and in organizational matters. The first area presents the traditional core area of authority, the control and support of schools around the internal matters of schooling, curriculum, and teacher competencies. Regarding the latter, as described above, German teachers are employed by the state, and the local school authorities exercise all employer responsibilities. There is a large share, albeit smaller than programmatic/professional supervision and organizational, for psychological and special education services, which adopt responsibility when students cannot follow regular schooling for various reasons. Due to their complex tasks, the offices have an extensive infrastructure, meaning that a substantial share of positions concern leadership and internal office functions.

The state of Brandenburg is an exception to the rule in relation to the special education services category. Special education support is currently coordinated at the municipality level. In other words, the local offices exert only psychological assessment and support. This solution also points to trends in the German system to merge municipality and state school authorities to further cooperation (Ebinger, Citation2010) and save costs. Moreover, three states have organized their education offices precisely in relation to municipalities. In particular, the largest German state, Bavaria, and the one with the most citizens, North-Rhine Westphalia, manage, in this way, the size of their constituency (Bogumil, Citation2017). In our data, the state of Baden-Württemberg has undergone a public administration reform in which municipality and school offices have been merged. Due to quality issues, this reform was rolled back (Richter, Citation2010). However, administration reform for apparent increased cost-effectiveness is a prominent trend in Germany, which means that administration reforms often involve cutting positions (Kuper, Citation2020). Fewer school administrators are responsible for more schools and teachers. This may decrease the consulting dimension in the supervision tasks until only control and administration are left.

In Sweden, we examined the school administration departments of all 290 municipalities by investigating their organizational descriptions and considering which focus areas are represented. Again, we focused on the major areas which became primarily visible in the organizational descriptions. Unfortunately, we have no data on how many positions are attributed to the areas, so we cannot, as we could in the German case, show their size. However, we can still illustrate what a municipality’s school administration typically looks like by showing which tasks must be handled by the municipalities in the decentralized Swedish system.

In the analyses of the Swedish data, we also present four categories (see ). However, due to the particularities of the empirical material, we can only identify whether or not a municipality has a specific area in its school administration description. Based on commonalities which cohere among most municipalities, we decided on the following categories as the most significant. This relates to how the municipalities chose to describe their administration when asked for a description of their education organization: Programmatic and professional supervision; organizational matters, psychological and special education student health). Finally, we determined whether, in the respective description, several leadership positions and internal office management are reported.

Table 2. Main and subordinate focus areas in the Swedish material.

Upon first glance at the larger municipalities in our material, big city municipalities (with at least 200,000 inhabitants) and municipalities close to bigger cities, and larger towns’ municipalities (at least 50,000 inhabitants), and municipalities close to such larger towns, most follow a similar pattern. Only significantly smaller rural municipalities follow partly different patterns.

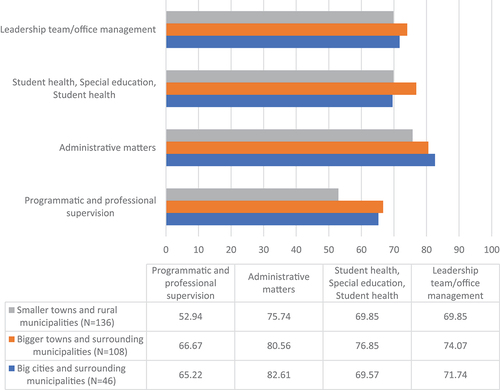

In total, we can see the following picture: (see )

Approx. 52-66 % of the municipalities report that they have units concerning the supervision of programmatic and professional matters

Approx. 75-83 % of the municipalities report that they have organizational units concerning administrative matters (such as HR, finance, and other organizational support)

Approx. 69-77 % of the municipalities report that they have organizational units concerning psychological and special education support

Approx. 69-74 % of the municipalities report on various leadership positions and particular office management structures.

Diagram 2. share of big city municipalities and surrounding municipalities (N = 46), bigger town municipalities and surrounding municipalities (N = 108), and smaller town and rural municipalities (N = 136) which have the displayed focus areas in their respective organization descriptions.

The municipalities’ school administrations have indeed appointed leadership teams, and in most cases, there is leadership differentiation between different school forms (such as compulsory schools, preschools, and upper secondary schools). This is very similar to the German model. Swedish municipalities also deal significantly with organization and staff development. We find programmatic and professional supervision in this category, even if the ‘program’, i.e. the curriculum, comes from the state. The administrative area in Sweden is also very much concerned with the category of external matters of schooling. As described above, in Germany, the local state school authorities are the employers of teachers. Here administrative matters are mostly related to HR. In Sweden, the municipalities are the employers of all the school staff (such as teachers and principals). However, municipalities are responsible even for all external, i.e. technical matters of schooling. School buildings must be maintained, and all IT infrastructure must work, which is why even administrative matters are an essential part of the municipalities’ responsibilities, even if their precise nature is different than in Germany. Smaller rural municipalities report less often that they have individual positions exclusively attributed to programmatic and professional supervision and organizational issues. This is not surprising, since small municipalities in particular have only limited resources for their school administration. Sometimes the head of the school administration is also employed part-time as a school principal. Smaller municipalities often share a single upper secondary school between them. There are also cases in which the head is the only permanently employed individual. This leads to a situation in which several organizational matters are processed by other municipality administrations, and programmatic and professional supervision is rather limited.

Finally, student health, in the form of psychological and special education support, is another major area in the municipalities’ school administration work. In the Swedish system, at the policy level, the issue of dealing with pupils’ special needs is highly institutionalized. According to the Education Act of 2010, municipalities and indeed each individual school are obliged to provide students with special needs access to health teams that are responsible for those students. Such teams consist of special educators, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and principals. The provision of special support is legally binding right of students and their parents. Moreover, the Swedish school inspectorate, i.e. the state, strictly controls whether municipalities and schools follow up individual educational programmes, and actively work on student health issues. In cases where appropriate support or appropriate support and student health structures are not provided, schools and municipalities can be sanctioned, and are often publicly denounced. In other words, the student health support system is more high stakes for school administrations in Sweden than it is in Germany.

In summary, even though the Swedish system is highly decentralized, at least compared to the German federal states, which might lead us to expect a considerable amount of local autonomy, we see many structural similarities between the 290 municipalities. Organization of schooling at the respective administrative levels must always cover certain given areas, which is why the Swedish municipal organizations often look similar. Moreover, when we look at the areas covered, we see that German and Swedish local authorities are required to organize and supervise similar things. We will discuss these similarities below.

Discussion

In this article, we have argued for the necessity to investigate the nature of school administration in order to further understand the frames of curriculum making. School administration means the organization which operationalizes a national school system by an organization that relates all the individual schools to each other. School administration, as well as the individual schools, are all part of the same organization. We have suggested categories that can be used to describe the nature of school administration, which we repeat in .

We have applied these categories by comparing school administrations in two national contexts, Germany and Sweden, firstly by analysing the overall structure of the school systems and the embedded school administrations, then by examining the tasks and positions within local school administrations at scale. The two case have been chosen purposefully, since they present two apparently opposite versions of governance regimes, and therefore varying conditions of curriculum making. We found that the suggested categories were supportive in order to further understand the nature of school development in its universalities and context-specific particularities.

When we look at the findings of our empirical studies, we see interesting aspects regarding the organization of school administration at different national, federal, and municipal levels. 1) The administrative structures and focus areas in a federally organized state like Germany are similar. 2) A system with high autonomy in municipalities, such as Sweden, is also organized in an equivalent manner at the municipality level. 3) Both Germany, which in its federal state is relatively centralized, and Sweden, which in comparison is much more decentralized, share significant similarities in the organization of school administration.

Our findings imply that there are indeed variances between various contexts. However, even within the national contexts there are variances, though these variances are often related to demographic particularities. In particular, in Sweden, municipalities can differ quite significantly in terms of their size, with consequences for the flexibility of school administration. In Germany, too, size is a significant factor for the structuring of federal states school administration (Bogumil, Citation2017). Moreover, when we further emphasize similarities over differences, we might understand our findings in the following way. The organization of mass education, due a stability imperative both in centralized and de-centralized governance systems, allows for only limited variance. In such organizations, various ways to supervise the parts of the system effectively are very important. Aspects that must be taken into consideration are internal matters, which are programmatic (goal achievement, psychological-special education support for the students), professional (teachers’ work and working conditions), and procedural (transparency and sustainability of the bureaucratic structure) in nature; as well as external matters (buildings, equipment, school lunch, school transport). School administration is really a means of standardizing school systems in order to make mass education possible.

School administration and the individual schools are related by a hierarchical but loose coupling. However, they nevertheless are coupled. The nature of the ‘looseness’ can be described by licence relations, in which principals have a specific licence for the action of school leading within certain borders (Hopmann, Citation1988), or within the frames/decision making premises of their superiors (Kuper, Citation2020; Luhmann, Citation2000). The complementary relation of independence and control can be, as we argue, described by the category ‘supervision’, which unites the aspects of control and support in autonomous decision-making of a superior level towards a subordinate level. This leads us to the question of the nature of autonomy, such as in curriculum making, in ‘centralized’ and ‘decentralized’ education systems. The autonomy of organizations must be answered in terms of whether or not they are able to decide on their premises. As Kuper (Citation2020, p. 88f.) points out: From a legal point of view, the term autonomy does not adequately characterize the relationship of the individual school to the school supervisory authorities. In a legal sense, a unit is autonomous when it is empowered to manage its affairs through the power to regulate the law by issuing legal norms (statutes). He argues further, referring to Luhmann (Citation2000), that Luhmann’s account of autonomy refers to an organization’s power to decide on its decision-making premises. Both legally and in terms of organizational theory, speaking about autonomy does not reflect a concrete organizational relationship between the management of a school and its supervision. The relationship initially remains underdetermined and is, therefore, dependent on interpretation.

Considering this line of thought on decision-making capacity, again as in curriculum making, in school systems, operationalized by school administration, we argue that decentralization in school systems, at least from an organization theory perspective, can be called for divisionalization instead. This term stems from the classic work of Henry Mintzberg (Citation1979), in which the main feature of a divisionalized model concerns the restricted delegation of decision-making to the subsequent organizational units.

There is some room for direct supervision, notably to authorize their significant expenditures and to intervene when their behavior moves way out of line. But too much direct care defeats the purpose of the decentralization […]. The standardization of skills, through training and indoctrination, can also be used to control the behavior of the manager of the parallel decentralized […] unit.

Consequently, Mintzberg argues that divisionalization is not decentralization, but rather centralization (p.386). The question is, however, which decisions are granted to the divisions and which are not. Divisionalization is possible only when the organization’s technical systems can be efficiently separated into segments, one for each division, and is a response to a bureaucracy which consists of a diversity of environments and indeed sizes. As the government grows, it is forced to revert to a divisionalized state. The central administrators, being unable to control all the agencies and departments (divisions) directly, settle for granting their managers considerable autonomy and then control them by performance. The curriculum might then be one of the programmes, probably not the only one, that enable this divisionalization of schooling. Consequently, the curriculum as interpreted by the school administration frames the interpretations of the professionals in the schools. The interpretations of the latter must relate to the legal and material frames as provided by the first. This results in a significant restriction of degrees of freedom in curriculum making. From this perspective, speaking about decentralization at all, might be misleading.

Finally, when we look at how various public education systems are organized, the existence of education mindsets has promoted a way of understanding variations in public education structures. Hopmann defines constitutional mindsets as ‘the well-established, basic social patterns of the understanding of schooling that have sedimented in the respective traditions’ (Hopmann, Citation2015, p. 18). Hopmann himself has developed this thought just in relation to curriculum making. When looking at the stability of institutional mindsets, such as worlds of welfare capitalism (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990), or Nordic models (Telhaug et al., Citation2006), we argue that these are manifested in education administration, rather than in education policy. The latter has incorporated many more homogenizing international policies, laws, and trends, but mindsets probably persist in the administration. It is critical to have a loose coupling or disentanglement between political and administrative arenas to ensure stability, lawfulness, and purposefulness in mass education (Hopmann, Citation1999). From this perspective, decentralization in education is autonomy within the limits of traditional means of school administration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altrichter, H., & Maag Merki, K. (Eds.). (2016). Handbuch Neue Steuerung im Schulsystem (2nd.). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-18942-0

- Avenarius, H. (2010). ”Schulautonomie“und Schulqualität. In H. Avenarius & H.-P. Füssel (Eds.), Schulrecht. Ein Handbuch für Praxis, Rechtsprechung und Wissenschaft, (Handbuch Schulrecht, 8., neubearb. Aufl. pp. 259–278). Link.

- Ball, S. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terror of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Bernstein, B. (1977). Class codes and control, towards a theory of educational transmissions. Routledge and Keegan Paul.

- Bogumil, J. (2017). Schulaufsicht im Bundesländervergleich. Lernende Schule 17, 12–15. https://www.friedrich-verlag.de/friedrich-plus/schulleitung/unterrichts-schulentwicklung/schulaufsicht-im-bundeslaendervergleich-1432

- Bogumil, J., & Ebinger, F. (2019). Verwaltungs(struktur)reformen in den Bundesländern. In S. Veit, C. Reichard, & G. Wewer (Eds.), Handbuch zur Verwaltungsreform (pp. 251–261). Springer VS.

- Ebinger, F. (2010). Kommunalisierungen in den Ländern – Legitim – Erfolgreich – Gescheitert? In J. Bogumil & S. Kuhlmann (Eds.), Kommunale Aufgabenwahrnehmung im Wandel. Kommunalisierung, Regionalisierung und Territorialreform in Deutschland und Europa (pp. 47–65). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). Three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity.

- Fend, H. (2008). Schule gestalten. Systemsteuerung, Schulentwicklung und Unterrichtsqualität. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Fries, A.-V., Hürlimann, W., Künzli, R., & Rosenmund, M. (2013). Lehrplan - programm der Schule [curriculum - the programme of the school]. Juventa.

- Hopmann, S. (1988). Lehrplanarbeit als Verwaltungshandeln [curriculum work as administrational actions]. IPN.

- Hopmann, S. (1999). The curriculum as standard of public education. Studies of Philosophy in Education, 18(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005139405296

- Hopmann, S. (2003). On the evaluation of curriculum reforms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270305520

- Hopmann, S. (2015). ‘Didaktik meets curriculum’ revisited: Historical encounters, systematic experience, empirical limits. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(1), 27007. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.27007

- Hopmann, S., & Haft, H. (1990). Comparative curriculum administration history. Concepts and methods. In S. Hopmann & H. Haft (Eds.), Case studies in curriculum administration history (pp. 1–10). Taylor & Francis.

- Kauko, J., Rinne, R., & Takala, T. (2018). Politics of quality in education. A comparative study of Brazil, China, and Russia. Routledge.

- Kauko, J., & Wermke, W. (2018). The contingent sense-making of contingency: Epistemologies of change and coping with complexity in comparative education. Comparative Education Review, 62(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1086/696819

- Kuper, H. (2020). Zum Verhältnis von Schulaufsicht und schulleitung – organisationstheoretische perspektive [on the relation between school supervision and principals- an organisation-theoretical perspective. In E. D. Klein & N. Bremm (Eds.), Unterstützung – Kooperation – Kontrolle (pp. 85–105). Springer.

- Luhmann, N. (2000). Organisation und Entscheidung. Westdeutscher Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-97093-0

- Luhmann, N. (2002). Das Erziehungssystem der Gesellschaft [the education system of the society]. Suhrkamp.

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organisations. A synthesis of the research. Michigan University.

- Ohlhaver. (2005). Schulwesen und Organisation – Zur Gestalt und Problematik staatlicher Schulregulierung am Fall von Lehrplanarbeit. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-80657-4

- Proitz, T. S., Aasen, P., & Wermke, W. (2023). Education policy and education practice nexuses. In T. S. Proitz, P. Aasen, & W. Wermke (Eds.), From education policy to education practice. unpacking the nexus (pp. 1–16). Springer International Publishing.

- Proitz, T. S., Mausethagen, S., & Gedsmo, G. (2017). Investigative modes in research on data use in education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1326280

- Richter, P. (2010). Kommunalisierung der Schulaufsicht – Erfahrungen aus der baden-württembergischen Verwaltungsstrukturreform. In J. Bogumil & S. Kuhlmann (Eds.), Kommunale Aufgabenwahrnehmung im Wandel. Kommunalisierung, Regionalisierung und Territorialreform in Deutschland und Europa (pp. 67–86). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Rönnberg, L. (2012). Reinstating national school inspections in Sweden – the return of the state. Nordic Studies in Education, 32(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-5949-2012-02-01

- Rürup, M. (2020). Schulrätin – Schulverwaltung - Schulhoheit. Einige begrifiche Diferenzierungen zum Untersuchungsgegenstand ‚Schulaufsicht‘. In E. D. Klein & N. Bremm (Eds.), Unterstützung – Kooperation – Kontrolle Zum Verhältnis von Schulaufsicht und Schulleitung in der Schulentwicklung (pp. 15–44). Springer VS.

- Schriewer, J. (1999). Coping with complexity in comparative methodology: Issues of social causation and processes of macro-historical globalisation. In R. Alexander, P. Broadfoot, & D. Phillips (Eds.), Learning from comparing. New directions in comparative educational research (pp. 33–72). Symposium.

- Schulte, B. (2018). Envisioned and enacted practices: Educational policies and the ‘politics of use’ in schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(5), 624–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1502812

- Schulte, B., & Wermke, W. (2019). Internationellt jämförande pedagogik. En introduktion [International and comparative education. An introduction]. Liber.

- Swedish National Agency of Education (SNAE). (2022). Skolverket inrättar kontor på 10 orter. July 20, 2023 https://www.skolverket.se/om-oss/press/pressmeddelanden/pressmeddelanden/2022-02-24-skolverket-inrattar-kontor-pa-10-orter.

- Telhaug, A. O., Mediås, O. A., & Aasen, P. (2006). The Nordic model in education: Education as part of the political system in the last 50 years. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 245–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743274

- Weick, K. (1976). Educational organisations as loosely-coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

- Wermke, W., & Forsberg, E. (2023). Understanding education reform policy Trajectories by analytical sequencing. In T. S. Proitz, P. Aasen, & W. Wermke (Eds.), From education policy to education practice. Unpacking the nexus (pp. 59–73). Springer International Publishing.

- Wermke, W., & Salokangas, M. (2021). The autonomy paradox. Teachers’ perception on self-governance across Europe. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65602-7