ABSTRACT

Schools for specific purposes (SSP) are and have been a significant feature of the education ecosystem since the roll out of mass schooling in Australia and elsewhere. SSPs serve some of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged communities. While their social and emotional worth to their communities (students, educators, families) is rarely questioned, the role of SSP in the pursuit of equity and inclusivity remains contested. This has significant implications for those charged with leading such schools, particularly principals. Drawing on the emerging field of relational studies, this paper undertakes a relational inquiry into the provision of education (RIPE) analysis of specific purpose schools for students with moderate and high support needs in the Australian state of New South Wales.

Introduction

On a global scale, pursuing Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) – ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all – has led to more children attending school than at any point in history. However, how best to deliver equitable and inclusive schooling at scale, particularly for students requiring additional support needs remains a contested space. Since at least the 1980s debates have raged concerning the separation and potential merger of special and mainstream schooling (Cologon Citation2013, Citation2019; Frick, Faircloth, and Little Citation2013), with many calling for the abolishment of special schools (Cologon Citation2019). For those charged with leading special schools, most notably principals, the need to guide and support an apprehensive collection of students, staff and community members can be taxing professionally and personally. This amplifies existing issues for school leaders such as having ever expansive roles, increasing stress, time pressures and burn-out resulting from workload intensification (Riley et al. Citation2020). There is an urgent need for comprehensive research on the social and professional expectations and responsibilities of the contemporary School for Specific Purposes (SSP) principal to inform how best to support and develop them.

Decisions on how best to support SSP principals requires a combination of large-scale data on the provision of schooling and localised narratives of the experience of school leaders. Due to the unique composition of their cohorts, both staff and students, fluctuations in societal norms are felt more heavily by SSPs since they typically have greater reliance on social, spatial, cultural and political relations than the economies of scale that larger and mainstream schools can access. Given these powerful relational dynamics implicated in the operations of SSPs, a relational approach to understanding SSPs is useful to consider and assist these schools and their leaders. The stakes are high. In addition to the contestation over their very existence, the vulnerability of students and families who attend SSPs mean the work of the school is fundamental to avoiding significant community costs and fallout were they to be closed or absorbed into nearby schools.

This paper employs a relational inquiry into the provision of education (RIPE) analysis to SSPs in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW). As a unique feature of Australian Federalism, each state/territory is constitutionally responsible for education and takes a different approach – our argument is focused solely on NSW, where multiple policies and reforms have been initiated in recent times (NSW Department of Education Citation2019, Citation2020). In addition to delivering descriptive analysis from publicly available datasets, the paper works with interview data from a study with 23 SSP principals. Based on our analysis we argue that SSPs exist in a state of constant tension where they are a distinction form of schooling yet part of a larger system. This plays out in particular ways concerning the underlying generative assumptions held regarding the purpose(s) of schooling, relations with orthodox forms of data on school performance, and ongoing debates about how SSPs fit within inclusive education. In building our argument, and as a structure for the paper, after providing a brief overview of the larger project and articulating the RIPE approach (methodology, key concepts, and analytical procedure), the paper is structured around the five moves of the relational approach: generative assumptions of SSP; problematising SSPs; how that plays out in practice; overcoming dualism; and a generative contribution.

Materials and methods

The larger project

Recognising that students with moderate and high support needs have limited opportunities to have their say in education, the larger project was conducted with 24 NSW public schools (i.e. 22 SSPs and 2 mainstream schools with support units). Students with moderate and high support needs have delays in intellectual and cognitive functions (Bellamy et al. Citation2010), need support in communication and require adjustments in teaching and learning to meet their needs (Ahsan and Sharma Citation2018; Luijkx, van der Putten, and Vlaskanp Citation2019). They are also referred to as students with profound and multiple learning difficulties (Nind and Strnadová Citation2020). The aim of the larger project was to determine the effectiveness of the trial of My Say My Way (MSMW), which consists of several accessible methodologies that were co-designed and co-produced. These accessible methodologies are three versions of survey, each catering to a different level of support need, Photovoice, and body mapping. In total, 195 students with moderate and high support needs participated in the surveys, Photovoice and/or body mapping, while 28 teachers took part in focus group discussions to inform the evaluation of the trial, and 25 principals participated in interviews to examine their experiences with the implementation of MSMW in their schools.

As a part of this larger project, the 23 interviews with medium / high support needs SSP principals has created an opportunity to explore the provision of SSPs and the implications for those charged with leading those schools. As an overview of the profile of participants: they are drawn from schools located throughout the state; the average age was 51 years (n = 20, σ = 6.6, x̃ = 50), with 26 years of teaching experience (n = 23, σ = 7.2, x̃ = 27), and an average of 18.5 years teaching students with moderate and high support needs (n = 15, σ = 10.8, x̃ = 20); the average tenure at current school was 7.5 years (n = 23, σ = 6.6, x̃ = 4); and 52 per cent (n = 12) have a post-graduate qualification (e.g. master’s degree). Pseudonyms have been adopted throughout the paper to protect participants’ anonymity and while interviews were transcribed verbatim, some text has been slightly altered to protect any incidental disclosure of school or location.

Relational inquiry into the provision of education (RIPE)

A theoretical and methodological framing

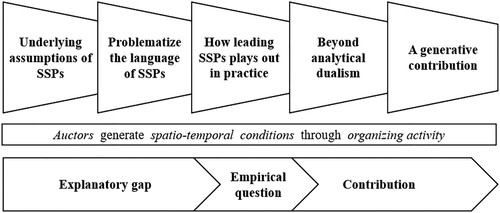

Drawing on the emerging field of relational studies (Dépelteau Citation2018), RIPE analysis is built on Eacott’s (Citation2018) relational approachFootnote1 and serves as a theoretical and methodological framework sensitive to the nuance of leading an SSP. As a methodological framing, the relational approach consists of five moves (). Although appearing linear in the figure, the analytical approach is one of constantly relating unfolding activity to other unfolding activity in an iterative process – all informed by the key concepts of organising activity, auctor and spatio-temporal conditions. For this study, the relational approach and concepts illuminates the underlying generative assumptions of SSPs as articulated in publicly available datasets on the provision of schooling, research literatures on special education leadership and administration and data generated from project participants regarding what it means to lead an SSP [the explanatory gap]. It then uses these insights to describe and explain how leading an SSP plays out in practice for principals [the empirical question].

Key concepts

The key concepts of the relational approach enable us to bridge the explanatory gap with the empirical question. Rather than assuming a static and singular version of what is an SSP, our analysis illuminates how the idea(s) held by participants and arguably wider society serve as an organising activity for how we think about SSPs. That is, how the underlying generative assumptions about SSPs are constitutive of and emergent from how participants and wider society describe SSPs and their work [the explanatory gap]. This means that participants and wider society are not passive spectators but embedded and embodied in the ongoing ways we think of SSPs [bridging the explanatory gap and empirical question]. Auctor, meaning ‘s/he who generates’ enables us to have the level of analytical sensitivity to illuminate how organising activity is generative of ongoing activity. Positive, or negative perceptions of the work of SSPs comes down to alignment between underlying assumptions and how they are experienced. These experiences are then correlated with the experiences of others in legitimising the organising activity of auctors and shaping contexts. Conceiving of auctors as embedded in and embodying this organising activity means that time and space (spatio-temporal conditions) are not separate to but generated through the constant unfolding of activity [the empirical question]. Taken together, the logic of these three key concepts is that auctors generate spatio-temporal conditions through organising activity. This logic explains how the assumptions of SSPs are constitutive of and emergent from assessments of the work of SSPs.

Analytical approach

To establish the underlying generative assumptions of SSPs required a synoptic perspective of how SSPs are constructed (or not) in publicly available statements concerning the definition of an SSP, the literatures of educational leadership and administration, and the individual transcripts of participants. This was an important analytical move as the pre-existing normative assumptions of participants and wider society shape how their work is perceived – including in relation to others. As embedded and embodied auctors these underlying assumptions are rarely called into question or subjected to analysis as they feel natural and not as assumptions at all. It is because of this unconsciousness however that these assumptions serve as an organising activity as they shape not only what one comes to expect but also what they see and do not see.

Building from the identification of underlying generative assumptions, the meaning assigned to SSP became the basis of analysis. Working within and across transcripts, publicly available data sets on the provision of SSPs and mapping using Geographic Information Systems (e.g. QGIS v3.18), this analytical activity problematises the idea of SSPs and serves as a reminder that we cannot assume that labels have a shared and universal meaning. Doing so highlights why the underlying generative assumptions of SSPs (as an organising activity) are a more appropriate focus of inquiry than uncritically accepting SSP as a static and forevermore idea. In addition, locating the analysis of interviews in relation to other data sets (e.g. publicly available data on the provision of schooling) demonstrates how context (spatio-temporal conditions) is embedded and embodied in the assumptions we hold of SSPs. These first two analytical tasks provide the basis for an analysis of the explanatory gap for the paper.

Foregrounding the interview transcripts, the next analytical task was to use examples from participants to show how assumptions play out in practice. Apart from serving as a test for internal validity in individual transcripts by demonstrating coherence between claims and descriptions, this activity draws attention to how the organising activity of auctors is constitutive of and emergent from spatio-temporal conditions. This ensures that, in this paper we can offer both an explanatory and descriptive account of SSPs and deliver on the empirical question of what it all means in practice for SSP principals.

To specifically go beyond simply adding to the volume of literatures on SSP (as a proxy for special education) school leadership, the next task was to relate the descriptions provided to one another by working across all data sources and the critique of SSPs without defaulting to analytical dualism (e.g. inclusive/exclusive). No activity occurs in a vacuum and the analytical task of relating activities is integral to building our argument. Having worked through the above four analytical tasks, this paper makes a generative contribution (the fifth move of the relational framing, see ) to dialogue and debate on SSPs principalship in Australia, with potential applicability for other jurisdictions and types of schools.

Generative assumptions regarding SSPs

Public schooling in New South Wales, Australia was established in 1848. The category of SSP has a history dating back to 1923. Having SSPs as a distinct category of school creates a partitioning of the school system where different types of schools are perceived as discrete knowable entities, even if sharing many similarities. In relational terms, the separation is an organising activity for the field. Reinforcing and legitimising this separation, the New South Wales Department of Education describes SSPs as some of the most unique and specialised settings within the system. Distinct categories of schools are not necessarily a negative, but they do specific work for perceptions – often reinforcing pre-existing assumptions held about types of schools and their work. Using the New South Wales Department of Education database, SSPs are defined as schools that:

… provide specialist and intensive support in a dedicated setting for students with moderate to high learning and support needs.

Schools for specific purposes support students with intellectual disability, mental health issues or autism, students with physical disability or sensory impairment, and students with learning difficulties or behaviour disorder.

They cater for students from kindergarten to Year 12 who meet the Department's disability criteria. (NSW Government Citationn.d.)

More than just policy statements and classifications of schools, in the research literatures of educational administration and leadership, the work of principals in special education (in its broadest sense) are at best peripheral (Caldwell Citation2020). If anything, it is a separate sub-field of educational administration and leadership partitioned off from core discourses of the field – symbolic of the partitioning of special schools and units from mainstream schools. That said, there has been a steady stream of handbooks (Crockett, Billingsley, and Boascardin Citation2018; Wang, Reynolds, and Walberg Citation1995), books (Bateman and Cline Citation2019; Rayner and Ribbins Citation1999), chapters (Skoglund and Stäcker Citation2016) and articles (Frick, Faircloth, and Little Citation2013; Sider et al. Citation2021) building a knowledge base. Partitioning leadership in special education sites away from mainstream school leadership research is not surprising given the separation serves as an organising activity for how we understand SSPs. More than just a theoretical exercise, the empirical implications for activities are clear. In New South Wales, principals of SSPs have their own professional association – Special Education Principals’ and Leaders’ Association (seplansw.org.au) – and it has a national level equivalent – Australian Special Education Principals Association (ASEPA). These run in parallel to state/territory and national primary and secondary principal associations further positioning not just SSPs as a distinct category of school but also the work of principals in SSPs as distinct to that of other school principals.

While 80 years ago Berry (Citation1941) argued that the problems of special education administration are like those in educational administration, the constantly unfolding complexities of how to create, assess, and evaluate programmes to serve students with disabilities creates a need for leadership with unique knowledge, skill, and experience (Pazey and Yates Citation2018). What has remained elusive is a theory of special education administration (Billingsley, McLeskey, and Crockett Citation2018; Willenberg Citation1966). Explanatory frameworks for the principalship in special education settings have drawn from varied sources such as education, law, disability studies, public health, economics of education, among others. Recent trends have conflated the principalship with ‘inclusive school leadership’ (e.g. Sider et al. Citation2021; Skoglund and Stäcker Citation2016). A major challenge for research and practice relating to the principalship in special education is describing and explaining what principals need to know and be able to do as they work with others to optimise the outcomes for students, educators, families, and communities (Billingsley, McLeskey, and Crockett Citation2018) and articulating, if it is the case, that this is distinct from other education providers.

It is this search for distinctions that creates a significant tension for SSP principals. While acknowledged as a different type of school, SSPs are still subjected to the same expectations as all systemic schools with regards to administration and to a lesser extent performance data. SSPs are required to undertake the same planning cycles as mainstream schools and engage in external validation processes and mapping against the School Excellence Framework.Footnote2 In the interview data from this study, Principal 12 points out, the Department of Education still ‘asks for evidence that you are doing a good job at your school’. Requesting, and expecting, data on the performance of school programmes is not problematic. Rather, it is the need for data and evidence that meets the Department’s standards that is not easily met by SSPs where students do not – and cannot – complete traditional forms of assessment. Generating data on student learning is an ‘intense process for SSPs’ [Principal 4]. For many SSP principals, it is even difficult discussing this with their Director of Educational Leadership (DEL, equivalent to a superintendent) because ‘unless they have direct experience within SSP settings, it can be difficult to grasp what it means to work with students with medium to high support needs’ [Principal 9].

Principal 6 provides some further insights into the nuance of SSPs. He notes:

If I pull up the SCOUT [systemic data platform] dashboard for my school, which every school lives on, there is just reams and reams and pages and pages of data that you can see on student learning, student attainment, student growth. All the NAPLAN [national testing regime in years 3, 5, 7 & 9] bands, all the levels, if you are in secondary, it is national science testing, it is everything. But for our special schools, you open it up and there is no data there. A case in point recently, with the new School Improvement Plan and the new School Excellence Framework, is that we must set growth and attainment targets, and that is now the mandatory number one part of your school plan. You are allowed three areas, but number one is now Department dictated where it was always a school’s choice.

He later adds:

Every DEL has been told to meet with their principals, go through the data on the SCOUT dashboard and then set goals. They are all around external tests for the high schools and primaries, and when [the DEL] comes in to talk to me, you know, what does that look like? It is a completely different conversation, and strangely, not many special education principals end up as DELs, because we are obviously viewed as not “real” principals, because we do not really understand learning! So there is very few DELs out there that would have a specific understanding, [of an SSP].

The partitioning of SSPs as a separate category of school, their legitimation and sustainment through discrete professional associations and the scale of provision suggest a distinctiveness to the principalship. In theoretical terms the separation and bespoke professional associations grant ontological status to SSP as a discrete, separate, and knowable entity, and gives them an explanatory value. Any sense of identity as an SSP principal is simultaneously constitutive of and emergent from relations with others. For while SSPs are a unique form of school, they still exist within the larger New South Wales public school system. The distinctions are an organising activity for how we come to understand schools – and notably different types of schools – and it is auctors who are complicit in sustaining and legitimising these distinctions through their ongoing activities. For SSP principals, they are at stake in the distinctions. The core of their identity as SSP principals is caught up in the ongoing separation of SSPs from other forms of schools and the uniqueness of their roles. Understanding this requires a shift from trying to establish the definitive role of an SSP principal to locating the work of SSP principals in relational terms.

Problematising SSPs

Not surprisingly given the broad scope of SSPs in policy statements, as a collection of schools they are not homogenous. Currently, based on Centre for Educational Statistics and Evaluation (CESE) and Australian Curriculum And Reporting Authority (ACARA) datasets, there are 117 SSPs in New South Wales distributed across seven classifications, these include: medium / high support needs (n = 64); behaviour disorder (n = 22); emotional disturbance (n = 12); hospital schools (n = 10); juvenile justice establishments (n = 6); debilitated by physical difficulties (n = 2); and diagnostic remedial reading assessment locations (n = 1).

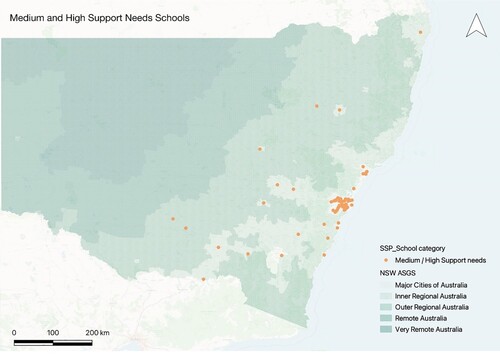

As an initial articulation of the scale of provision, displays a crosstabulation of SSPs by type and their location using the Australian Statistical Geographic Standard (ASGS) categories. Most SSPs (of all classifications) are in major cities – reflective of population centres – with fewer SSPs in regional (inner and outer) locations and none in remote or very remote localities. At face value, this demonstrates that the further one is located from a major population centre the fewer resources there are available for families with children requiring additional supports and seeking to enrol in an SSP. From an explanatory standpoint, this provision pattern embeds spatiality in how we come to understand SSPs. Put simply, the intimate relations between schooling, and in this case SSPs, and space cannot be separated.

Table 1. Crosstabulation of Schools for Specific Purpose by Geographic Location.

Temporality matters too. While the category of SSP was established in 1923, based on CESE data on the schools currently listed as SSP, they have histories dating back to 1913 (pre-dating the official category), with the most recent commencing in 2021. The average year for the first appointment of a teacher across the 117 SSPs is 1979 (n = 117, σ = 22.8, x̃ = 1978), with significant periods of growth including the decades 1970–1979 (n = 25, 21 per cent of all SSPs), 2000–2010 (n = 21) and 1960–1969 and 1980–1989 (n = 17).

Narrowing our focus to ‘medium / high support needs’ SSPs (which are the focus of this paper), the average establishment year is 1976 (n = 64, σ = 21, x̃ = 1974), with the most significant periods of growth being the 1970–1979 (n = 19), 1980–1989 (n = 13) and 1960–1969 (n = 12) with 69 per cent of all medium / high support needs SSPs established between 1960 and 1989. Taking the average (1976) or median (1974), individual SSPs have a history of 40 + years of provision. Their presence is multi-generational and very much part of the educational ecosystem of the New South Wales public school system, mindful however of the uneven spatial distribution of schools throughout the state. To visually display this distribution, is a map of medium / high support needs SSPs throughout New South Wales.

Embedding spatio-temporal conditions in how we understand and conceive of SSPs also requires some attention to the scale of provision and the communities in which the schools serve. In relation to the scale of operations, using ACARA 2020 school profile datasets, SSPs constitute 5.28 per cent of the New South Wales public school system (117 / 2,214 schools), 0.71 per cent of all students, 2.5 per cent of teaching staff, and 8.29 per cent of non-teaching staff. Medium / high support needs SSPs make up 76 per cent of all SSP students (n = 4,413), 67 per cent of teaching staff (n = 867) and 67 per cent of non-teaching staff (n = 874). SSPs, of all categories, are on the periphery of provision within the public school system due to their relatively small size. Despite the potential for volatile enrolment fluctuations, 84 per cent of medium / high support schools are older than 30 years, yet their relative size (as with all SSPs) compared to the provision of primary, central and secondary schools keep them on the periphery.

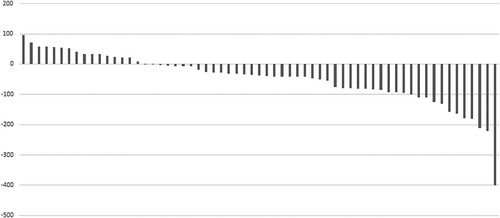

As an initial insight into the communities the schools serve, drawing on ACARA’s Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) it is possible to establish a profile of the SSPs. As an overview, displays the ICSEA for the medium / high support needs SSPs against the median score (μ = 1000) for all Australian schools. A quarter (n = 16) of the schools have an ICSEA above 1000, and therefore three quarters of the schools have an ICSEA below the median (n = 63, x̅ = 953, σ = 84, x̃ = 964). Nationally, across all schools, the range for ICSEA is from approximately 500 (representing the most extremely disadvantaged) through to approximately 1300 (representing the most extremely advantaged). While higher than the median for all SSPs (n = 103, x̅ = 922, σ = 118, x̃ = 925), the medium / high support needs schools serve communities that are more likely to be socio-educationally disadvantaged, further compounding their location on the periphery of school provision.

Working with diverse communities also introduces the prospect of varying purposes of schooling. One challenging aspect for SSPs is balancing expectations. Examples of parental expectations provided by participants included ‘no, my child cannot learn’ [Principal 6] and ‘I just want my child to be happy’ [Principal 12], ‘we are not here for an ATAR (Australian tertiary admissions rank)’ [Principal 18], not to mention the grief, sense of loss and low self-esteem experienced by some parents [Principal 17]. Many of the students in medium / high support require substantial 24 hr a day support which can be exhausting for families [Principal 1], parents are often in survival model [Principal 5], and school hours act as a kind of respite [Principal 11]. This creates a potential tension for SSPs. More than any other form of schooling, SSPs operate at the intersection of education, health, and social work. Much of the day for support staff is consumed with matters of student well-being, personal care, health care, and administration generating significant time pressure on the educational role of schools. But as Principal 12 notes, ‘we often have to remind parents that it is a school, and therefore we have to focus on the curriculum’.

These perspectives are not limited to parents and caregivers. Principal 6 spoke of arriving at a school (SSP) where there was no evidence of any curriculum in reporting or planning, even experiencing some staff responding with ‘since when have key learning areas been mandatory’. Complicity with the idea that SSPs are a distinct form of schooling allows ideas to germinate and proliferate that the purpose(s) of them as school is distinct from that of other schools. It can for many groups reduce the educational expectations on SSPs and recast them as something other than a school. Uncritical acceptance of these distinctions means that the work of SSPs is rarely called into question. The idea of difference, that serving as the organising activity for how we come to understand SSPs, and actively advanced by auctors, becomes the identifying feature of and generative of the spatio-temporal conditions in which SSPs operate.

How leading an SSP plays out in practice

The New South Wales public school system is one of the largest in the southern hemisphere with over 823,000 students, 94,000 teachers and staff across more than 2,200 schools and an annual operating budget of approximately $17.4 billion. With such a scale, systemic reforms are designed to work for most schools (e.g. primary, secondary, central), amplifying the location of SSPs on the periphery. Principal 6 noted, ‘they could start with us, but it would cost them a hell of a lot more and take a lot more time, so it is easier to put out a generic thing and ask “where doesn’t it work for an SSP and let’s see it we can tweak it a bit”’. Even then, as Principal 21 adds, the system is only ever considering the highest functioning students not the range of students in SSPs. For principals of SSPs, their location within the larger systems creates a sense of little or even a muted voice within the large data catchment and policy making machinery of the Department [Principal 3].

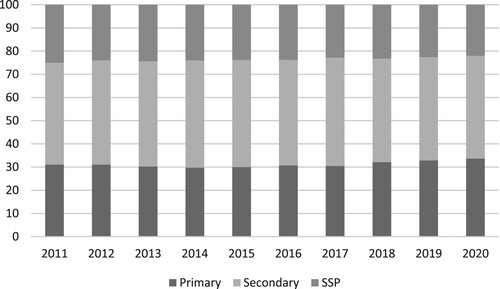

Compounding the perception of a muted voice, enrolments in SSPs make up less than a quarter of all students in specialised support units within the New South Wales public school system. displays the percentage of student enrolments in primary and secondary school support units and SSPs in the period 2011–2020. Over this ten-year period, the total number of students in support units has risen by 35 per cent from 19,437 through to 26,264 yet the distribution of those students in SSPs has steadily dropped from 25 per cent (2011–2012) to 24 per cent (2013–2016) then 23 per cent (2017–2019) and now represents 22 per cent (2020). In short, SSPs are not just a small part of the system but also a declining part of the support unit infrastructure in the provision of public schooling in the state.

Narrowing down to medium / high support needs SSPs, and using ACARA school profile data (2020), the average medium / high support needs school has an enrolment of 70 students (n = 63, x̅ = 70.05, σ = 33.14, min = 19, max = 185, x̃ = 61) made up of 50 boys (σ = 23.72, min = 12, max = 124, x̃ = 43) and 20 girls (σ = 10.92, min = 2, max = 61, x̃ = 20) with 15 per cent identifying as Indigenous (n = 57, x̅ = 14.67, σ = 11.22, min = 1, max = 42, x̃ = 11), 36 per cent with a language background other than English (n = 61, x̅ = 36.41, σ = 26.14, min = 2, max = 88, x̃ = 31) all being taught by 16.25 full-time equivalent teaching staff (σ = 6.99, min = 4.70, max = 39.70, x̃ = 14.50) and supported by 14.68 full-time equivalent non-teaching staff (σ = 6.40, min = 4.40, max = 37.20, x̃ = 12.50). As noted previously, they are more likely to be in major cities or inner regional location and have been in operation for 40 + years.

The issue with SSPs is not just their size, as with all schools in the system, SSPs have difficulties finding high impact staff. But more specifically, there is difficulty finding ‘special education qualified teachers’ [Principal 14]. That is, quality educators with the necessary background and skillset for working in SSPs. For many students in SSPs, the standard (national or state iteration) curriculum is not accessible [Principal 1] and having the teachers capable of translating curriculum to meet individual student needs is paramount. At the same time as struggling to attract and retain staff, SSPs are also seen as a resource by local schools (primary and secondary) for their support units when they have a particular student who they are having difficulties meeting their needs [Principal 6]. This potential stretches staff in many different directions and the unique conditions of SSPs have them operating in a state of constant tension where they are at the periphery of the system yet also seen as a resource for others. They are at once different yet treated the same.

For example, the National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) testing that takes place annually for Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 across all Australian schools is problematic for SSPs – at least the medium / high support needs variety. Every year SSP principals need to write – in a very carefully crafted letter – to families for information (e.g. confirming their child has a severe disability) to enable an exemption [Principals 3, 4, 6, 9 & 12]. For many, this is perceived as just another thing that systemic staff simply do not understand about SSPs [Principal 6]. Principal 4 spoke of how every second year or so there would be a phone call from a systemic staffer suggesting that surely some students at the school could undertake NAPLAN and would then need to outline why the students cannot and how that is the reason the students attend the school in the first place. In short, Principal 4 is being asked to justify how they take the highest support needs children who require additional supports and how they cannot complete the same tasks as mainstream students. In doing so, principals are not just being asked to justify their school’s own approach to engagement (or not) with NAPLAN but on a larger scale, also justify the very existence and purpose of SSPs in the first place. This burden is often invisible but arguably takes a toll on principals.

Orthodox approaches to generating (e.g. NAPLAN, Tell Them From Me) and curating data (e.g. SCOUT) in public schools are either not possible or not useful for SSPs [Principal 3, 12]. While mainstream principals can push a button to generate data visuals and tables, SSP principals need to curate data to map against individual learning plans for each student [Principal 4]. This does not mean that quantitative targets are not present, but they mean something different in SSPs. As an example, it might be possible to claim that ‘X students achieved theory literacy outcomes’, but those outcomes were not standardised or benchmarked against any external indicators of success (e.g. curriculum documents) and not all students will have learning plans in the same area. Practically, for educators, the almost paper-less teaching and learning approaches of SSPs means that generating data on student learning can be very labour intensive. Furthermore, the work of SSPs tends to be inefficient, with each school doing its own thing, and essentially reinventing the wheel.

With the emergence of new infrastructures and the datafication of education policy and governance (e.g. Gulson and Sellar Citation2019), it is not surprising that principals of SSPs, as with all schools, want more information on how programmes are going and students are progressing [Principal 1, 2, 6, 14, 18]. Currently, a lot of the data in SSPs is generated by educators or parents with little from students [Principal 5]. This remains the most substantive evidence void for SSPs [Principal 21]. In an almost paper-less learning environment, data generation is constrained by the verbal abilities of students [Principal 13] or the capacity – including informed consent – to record interactions [Principal 1]. Even if this is possible, against what would assessments be made? As noted earlier, many parents often state they just want their child to be happy at school. But what exactly does that mean? Even if taking happiness to be the goal, how can a school distinguish between a student being happy because they are at school or whether they are happy not to be somewhere else? [Principal 12]. The absence of individual or school-level student performance (against curriculum standards) or well-being (e.g. happiness) data means that students relying heavily on parents and educators to advocate for them [Principal 14].

While parents may sometimes express purposes not associated with standard markers of school success (e.g. high grades, university entry), it does not mean there is no long-term goal. As Principal 18 notes, ‘parents are very stressed about what happens in year 13, when [students] leave’. To address this, parents want to see ‘major projects and money spent on getting the kids out in their community’ throughout their schooling – not just at the very end [Principal 18]. Opening schooling and its pursuit to beyond the school gates makes for constantly unfolding relations. In addition to calling on a wider range of professionals (e.g. occupational therapists, speech therapists), negotiating transport and design options, the principalship in SSPs is located visibly at the intersection of education, allied health, disability, and social work.

Beyond analytical dualism

Schools, of all varieties, are more than mere physical buildings. Claims that schools are embedded in context are ubiquitous, but what exactly is meant by context is rarely elaborated (Eacott Citation2018). Similarly, the idea that schools generate more than academic outcomes (Ladwig Citation2010) is commonly acccepted but usually without any alternate data provided to support the case. The absence of at scale data matter in more ways here than may at first appear. Without a clear narrative of the contribution of SSPs and robust data to support that position, others will impose their own version on SSPs and make judgements accordingly. In doing so, there is frequently the establishment of an analytical dualism (e.g. efficient / inefficient, inclusive / segregated) which is not only unhelpful but leaves schools open to unnuanced, ill-founded and often unfair critique.

Education systems are constantly looking for more efficient ways to deliver equitable and inclusive education to populations. Assessing efficiency is often limited to economics and has a long and contested history in educational administration (e.g. Callahan Citation1962). The spend on special education (as the largest part of equity and welfare expenditure) was identified as a potential cost saving area within the New South Wales Department of Education in a 2010 report from the Boston Consultancy Group (BCG). It was suggested that there was an opportunity to restructure the fast growing spend through a balancing of increasing support and integration costs within federal and state anti-discrimination legislation to ensure that marginalised students were not further disadvantaged (BCG Citation2010).

Based on 2018–2019 financial year reporting on the Australian Government MySchool website, the average recurrent funding per student for medium / high support needs SSPs was $61,738 (n = 62, σ = 13,383, min = 44,887, max = 115,831, x̃ = 58,972) with 76 per cent sourced through New South Wales government recurrent funding (22 per cent from Australian Government; 0.3 per cent fees; and 2 per cent other sources). SSPs are more expensive per student than other forms of public school provision (e.g. primary, secondary, combined). They also attracted an average of $264,743 in capital expenditure in the previous three years (n = 62, σ = 847,452, min = 15,202, max = 4,852,043, x̃ = 67,481), funded almost exclusively by the state government. SSPs are more expensive to run than mainstream schools as staffing ratios, architecture and infrastructure requirements make such costs necessary to meet student needs. Reducing assessment of SSPs to a single economic measure loses the nuance that constitutes those expenses. Failure to make these necessary adjustments would make schooling inaccessible for students. However, meeting students’ needs and their right to be educated is a contested discourse.

There is a very strong and vocal anti-SSP lobby in New South Wales and Australia. Citing Article 24 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which stresses inclusive education is a fundamental human right for every child with a disability, anti-SSP lobbyists see SSPs as an example of education segregation. Although this claim may hold up at face value, as students are educated in separate sites, it is a difficult argument to sustain in the Australian context where according to 2020 Australian Bureau of Statistics data 34.4 per cent of students attend non-government schools where entry is dependent on financial capacity, religious affiliation, or specific attributes (e.g. gifted and talented, sporting). This does not even include students attending government selective schools or those based on gender (e.g. girls or boys schools). Segregation and stratification are embedded in the current provision of schooling in Australia.

Attempts to classify SSPs as inefficient, devoid of performance data, or outside the school system are misplaced. SSPs are part of a larger education ecosystem and cannot be understood outside the relations they share with that ecosystem. Even the separation of SSPs as a form of schooling – the very organising activity of their existence – means that their most distinctive properties are relational (what they are, or are not, in relation to others). Critique that defaults to dualism becomes constrained by its own structure (efficient or not, inclusive or not) and cannot provide any means of something different other than to impose a pre-existing normative assumption. To move beyond critique or advocacy, there is a need to acknowledge the existing frontiers of knowledge claims and push them further by understanding SSPs to best support those who lead them.

A generative contribution

We are still some distance from fully grasping what it means to lead an SSP and propose an elusive theory of special education administration (Billingsley, McLeskey, and Crockett Citation2018; Willenberg Citation1966). This paper makes its contribution to this larger and historical agenda by focusing on the provision of SSPs in the Australian state of New South Wales through diverse data.

SSPs have a long history of provision. However, this provision is defined by a separation from mainstream forms of schooling. While this separation is the organising activity for SSPs it also creates a tension. SSPs are part of the public school system in New South Wales. The idea that they are different yet still the same as other schools within the system is problematic. To highlight the distinctions is to legitimise the separation and given the scale of SSPs within the system, potentially further marginalise SSP principals. At the same time, the systemic expectations do not alter – rather just adjust in an attempt at inclusivity – for SSP with regards to data, targets, and administration. The principalship is not necessarily distinct in SSPs compared to other forms of schooling within the system. What is different is how schooling is organised and how that plays out in SSP in relation to other sites. The underlying generative assumptions that people bring to SSPs and the broader organisation and purpose(s) of schooling matter here. The shift is subtle but significant. Therefore, instead of pursuing an elusive theory of special education leadership or administration, attention might be far better to focus on the organising of schooling.

The distinctions between SSPs and other forms of schooling are legitimised and sustained through various mechanisms. These distinctions are always in relation to others and generated by auctors. They are manifested through systemic classificatory schemes, parallel professional networks and associations, scale within the system, and the lack of comparable data in large-scale data generating infrastructure. Those working within and beyond SSPs are embedded and embody these distinctions and become at stake in the claims. Not only is their work but their identities and a sense of belonging is generated and curated through the distinctions. More than principals, these distinctions generate identity work for educators, students, families, and communities. Embedded within these distinctions are matters of spatiality and socio-educational (dis)advantage.

The boundaries between wider society and schools are much more visible in SSPs. They do not simply have transactions with other agencies (e.g. allied health) or separate physical design of the learning space from pedagogy, instead they all work in relation. The complexity of SSPs, which are not a homogenous category, are grounded in the relations of wider society. Offering descriptive and explanatory insights courtesy of diverse data sets, we have demonstrated that the provision of SSPs is an example of life on 5the margins. They operate on the periphery of the system, have a limited geographic reach, and service communities more likely to be of socio-educational disadvantage. Expectations from parents, systemic personnel, and lobbyists (both supportive and critical) all amplify the relations of working in SSPs. These spatio-temporal conditions are generated by auctors through the underlying assumptions they hold of SSPs. Supporting current and aspiring school leaders in SSPs requires both learning how to lead but also learning for leadership. The latter requires understanding of the many unfolding relations that are simultaneously constative of and emergent from SSPs. This paper is far from the final word on the principalship in SSPs but serves as a call for others to seek to grapple with the complexity that is the equitable and inclusive provision of schooling at scale.

Ethical approval

This work was approved and supported by the UNSW Ethics Committee, ethics approval number HC200186; and the NSW Department of Education Ethics Committee (SERAP), ethics approval number: 2020055.

Acknowledgments

We would like to whole-heartedly thank all school principals who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Iva Strnadová

Iva Strnadová, PhD, is a Professor in Special Education and Disability Studies at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She is also Academic Lead Research at the Disability Innovation Institute at the UNSW. Her research aims to contribute to better understanding and the improvement of the life experiences of people with disabilities, especially people with intellectual disabilities. Combining research with advocacy is essential in her research programme, which builds on supporting the self-determination (including self-advocacy) of people with intellectual disabilities, and is grounded in an innovative inclusive research approach.

Scott Eacott

Scott Eacott, PhD, is Deputy Director of the Gonski Institute for Education and a Professor in the School of Education at UNSW Sydney and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Educational Administration at the University of Saskatchewan. He leads an interdisciplinary research programme that seeks to develop tools for educators, schools, and systems to better understand the provision of schooling through relational theory. Scott has authored >100 publications, been awarded >$3.8M in research fundings, successfully translated his research into policy and practice, and been invited to talk on his work in Norway, Canada, the USA, Indonesia, South Africa, Mexico, and throughout Australia.

Joanne Danker

Joanne Danker, PhD, is a Lecturer in Special Education in the School of Education at the University of New South Wales. She specialises in the well-being of students with developmental disabilities (i.e. autism spectrum and intellectual disabilities), inclusive and special education, and enabling the voices of individuals with disabilities in research. Further details of her work can be found at https://research.unsw.edu.au/people/dr-joanne-cherie-danker

Leanne Dowse

Leanne Dowse, PhD, is Emeritus Professor in Disability Studies at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She is also Associate Director at the Disability Innovation Institute at UNSW. Her work spans an interdisciplinary programme of research in disability aimed at creating knowledge to build capacity to address issues for people with cognitive disability who experience complex intersectional disadvantage, people with complex behaviour support needs and those in contact with the criminal justice.

Brydan Lenne

Brydan Lenne PhD, is a Senior project officer in the Disability Strategy team at the NSW Department of Education. Her work and research interests include using innovative methods to explore educational, diagnostic and clinical trial settings with young people with disabilities, and enabling both parents and young people to have their voice heard.

Dennis Alonzo

Dennis Alonzo is a Senior Lecturer in assessment, evaluation and teacher development. He has an extensive track record in establishing the dimensions of various constructs. He has developed the teacher assessment for learning literacy tool, findings from which were used to develop the empirically-driven framework for defining and describing teacher assessment literacy. The tool has been contextualised for EAL/D teachers and for higher education. As an ECR, he has been involved in many national and international research projects totally ∼$2.5M.

Michelle Tso

Michelle Tso is a PhD student at the University of New South Wales. Her PhD thesis is on the peer interactions of female high school students on the autism spectrum. She is supervised by Professor Iva Strnadová, Dr Sue O’Neill and Dr Joanne Danker. Her research interests are in inclusive and special education, and especially in supporting students on the autism spectrum to have increased well-being in the school environment and beyond. She is a research assistant on projects at the University of New South Wales (School of Education, and the Disability Innovation Institute).

Julie Loblinzk

Julie Loblinzk is a Self-advocacy Coordinator at Self Advocacy Sydney, Inc. She is also an Adjunct Lecturer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. In her role she lectures to undergraduate and postgraduate students about topics such as self-advocacy and parenting with intellectual disability. She is also involved in inclusive research and is currently working with Prof Iva Strnadová on numerous research studies.

Notes

1 We adopt the stylistic choice advocated by Eacott (Citation2018) of italicising relational when specifically talking about his approach. Similar conventions are applied to the three key concepts of the organising activity, spatio-temporal conditions, and auctor.

2 See Excellence for schools for specific purposes (nsw.gov.au) and School Excellence Framework Version 2 July 2017 (nsw.gov.au)

References

- Ahsan, T., and U. Sharma. 2018. “Pre-service Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusion of Students with High Support Needs in Regular Classrooms in Bangladesh.” British Journal of Special Education 45 (1): 81–97. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12211.

- Bateman, D., and J. Cline. 2019. Special Education Leadership: Building Effective Programming in Schools. New York: Routledge.

- Bellamy, G., L. Croot, A. Bush, H. Berry, and A. Smith. 2010. “A Study to Define: Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilties (PMLD).” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 14 (3): 221–235. doi:10.1177/1744629510386290.

- Berry, C. S. 1941. “Chapter I: General Problems of Philosophy and Administration in the Education of Exceptional Children.” Review of Educational Research 11 (3): 253–260. doi:10.3102/00346543011003253.

- Billingsley, Bonnie, J. McLeskey, and J. B. Crockett. 2018. “Conceptualizing Principal Leadership for Effective Inclusive Schools.” In Chap.15 in Handbook of Leadership and Administration for Special Education, edited by Jean B. Crockett, Bonnie Billingsley, and Mary Lynn Boscardin, 302–336. New York: Routledge.

- Boston Consultancy Group. 2010. Expenditure Review of the Department of Education and Training (DET) - Initial Scan Draft Final Report. Sydney: Boston Consultancy Group.

- Caldwell, B. J. 2020. “Leadership of Special Schools on the Other Side.” International Studies in Educational Administration 48 (1): 11–16.

- Callahan, R. E. 1962. Education and the Cult of Efficiency. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Cologon, K. 2013. “Recognising Our Shared Humanity: Human Rights and Inclusive Education in Italy and Australia.” Italian Journal of Disability Studies 1 (1): 151–169.

- Cologon, K. 2019. Towards Inclusive Education: A Necessary Process of Transformation. Sydney: Children and Young People with Disability Australia (CYDA).

- Crockett, J. B., B. Billingsley, and M. L. Boascardin. 2018. Handbook of Leadership and Administration for Special Education. New York: Routledge.

- Dépelteau, F. 2018. The Palgrave Handbook of Relational Sociology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eacott, S. 2018. Beyond Leadership: A Relational Approach to Organizational Theory in Education. Singapore: Springer.

- Frick, W. C., S. C. Faircloth, and K. S. Little. 2013. “Responding to the Collective and Individual “Best Interests of Students”: Revisiting the Tension Between Administrative Practice and Ethical Imperatives in Special Education Leadership.” Educational Administration Quarterly 49 (2): 207–242. doi:10.1177/0013161(12463230.

- Gulson, K. N., and S. Sellar. 2019. “Emerging Data Infrastructures and the New Topologies of Education Policy.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (2): 350–366. doi:10.1177/0263775818813144.

- Ladwig, J. G. 2010. “Beyond Academic Outcomes.” Review of Research in Education 34: 113–141. doi:10.3102/0091732X09353062.

- Luijkx, J., A. A. J. van der Putten, and C. Vlaskanp. 2019. “A Valuable Burden? The Impact of Children with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities on Family Life.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 44 (2): 184–189. doi:10.3109/13668250.2017.1326588.

- Nind, M., and I. Strnadová. 2020. Belonging for People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities: Pushing the Boundaries of Inclusion. New York: Routledge.

- NSW Department of Educaiton. 2019. Disability Strategy A living document. Accessed 15 September 2021. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-support/media/documents/disability-strategy-2019-online.pdf.

- NSW Department of Educaiton. 2020. Progress Report: Improving outcomes for students with disability 2020. Accessed 15 September 2021. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-support/our-disability-strategy/Progress-Report_Improving-outcomes-for-students-with-disability-2020.pdf.

- NSW Government. n.d. Schools for Specific Purposes (SSPs). Disability, Learning and Support. Accessed 25 August 2021. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-support/programs-and-services/special-schools-ssps.

- Pazey, B. L., and J. R. Yates. 2018. “Conceptual and Historical Foundations of Special Education Administration.” In Chap.2 in Handbook of Leadership and Administration for Special Education, edited by Jean B. Crockett, Bonnie Billingsley, and Mary Lynn Boscardin, 18–38. New York: Routledge.

- Rayner, S., and P. Ribbins. 1999. Headteachers and Leadership in Special Education. Bloomsbury.

- Riley, P., S.-M. See, H. Marsh, and T. Dicke. 2020. The Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey (IPPE Report). Sydney: Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University.

- Sider, S., K. Maich, J. Morvan, M. Villella, P. Ling, and C. Repp. 2021. “Inclusive School Leadership: Examining the Experiences of Canadian School Principals in Supporting Students with Special Education Needs.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 21 (3): 233–241. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12515.

- Skoglund, P., and H. Stäcker. 2016. “How Can Education Systems Support All Learners? Tipping-Point Leadership Focused on Cultural Change and Inclusive Capability.” In Implementing Inclusive Education: Issues in Bridging the Policy-Practice Gap (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, Vol. 8), edited by Amanda Watkins and Cor Meijer, 111–136. Bingley: Emerald.

- Wang, M. C., M. C. Reynolds, and H. J. Walberg. 1995. Handbook of Special and Remedial Education: Research and Practice. Bingley: Emerald.

- Willenberg, E. P. 1966. “Chapter VII: Organization, Administration, and Supervision of Special Education.” Review of Educational Research 36 (1): 134–150. doi:10.3102/00346543036001134.