ABSTRACT

In this piece the author provides a critical response to the new ‘Looking at Our School’ quality framework in Ireland and illustrates how policy overlooks critical scholarship. The author questions the claim that the updated policy reflects recent thinking and developments, and critiques the policy's stance on notions of both distributed leadership and effectiveness, and the policy overload it generates. Although much broader issues relating to the disconnect between research and policy and the prominence of the ‘what works’ discourse in education, this new framework in Ireland typifies a case of critical scholarship being passed over in policy. While this respondent is unconvinced by the policy that has been produced, packaged, and presented by policy makers, perhaps there is room for optimism in that recent personnel changes in the education ministry in Ireland could possibly pave the way for more much-needed critical perspectives in policy making. More critical scholarship is also needed, and there is a need for academics to not only advise policy makers but, professionally of course, challenge their thinking and question their decisions.

Introduction

On 26th August 2022 Ireland’s Department of Education (DoE) published a new quality framework, ‘Looking at our School’ (LAOS), to support school self-evaluation (SSE) in the country’s schools. This is the third cycle of compulsory SSE in Ireland: the first was for the period 2012-2016; the second was 2016–2020, although this was extended until recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic; and now the latest version is set to cover September 2022 to June 2026. Nearing the end of the first decade of mandatory SSE, a recent critical paper published in this journal put forward that while improvement is predominantly promoted in official discourse, accountability and economic logics dominate SSE in Ireland, which could potentially undermine the improvement logic and teachers’ sense of professional responsibility (McNamara et al. Citation2022). This piece now offers a response to the latest policy, by focusing on ‘Looking at Our School 2022: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools’ (DoE Citation2022a), which will be referred to here as LAOS 2022. In doing this, the manuscript examines the policy through a critical lens and draws attention to how critical scholarship is being ignored in policy; critical scholarship being work that is subjective, draws on theoretical resources from, for example, sociology and philosophy, pays close attention to context, challenges taken-for-granted assumptions, and looks for deeper or hidden meanings.

With the previous cycle of SSE being due to cease in 2020, coupled with two years of an extension due to the unprecedented circumstances of a global pandemic, we may have expected something more refined than what has been produced, packaged, and presented. What arrived in email inboxes gives the impression of policy introduced in haste. The point was made by Stephen Ball three decades ago that the text that arrives does not do so ‘out of the blue’ as it has an interpretational and representational history (Ball Citation1993), and although it was known that an updated framework was to eventually come, the release of LAOS 2022 in late August, as well as the accompanying ‘School Self-Evaluation: Next Steps’ (DoE Citation2022b) document, seems peculiar – could these documents not have come well in advance of the new school year? For schools, thankfully there are not a lot of major changes to brush up on, but it is ‘simply assumed that schools can and will respond, and respond quickly, to multiple policy demands and other expectations’ (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012, 9). Moreover, the document itself is unconvincing. A foreword is notably absent – the previous 2016–2020 document included one from the then Minister for Education and Skills. Little work appears to have gone into the actual document, and for the most part a response to the new 2022 policy is in many ways a response to the previous 2016 version too. Indeed, it is acknowledged that ‘the structure and content of Looking at Our School 2022 remain substantially the same as in the 2016 publication’ (DOE Citation2022a, 6).

The following section looks at recent scholarly thinking and developments of a critical nature, predominantly put forward by the current author, that are missing from LAOS 2022. There are then three consecutive sections that critique the stance of LAOS 2022 on, first, distributed leadership and, then, effectiveness, with a section on the policy overload LAOS 2022 generates wedged in between. The penultimate section explains why critical scholarship is not being reflected in policy, and finally the paper ends by stressing the need for more critical perspectives in policy making. In offering this critical response and looking at the absence of critical scholarship in policy, there is a lot to cover and the pressures of space mean that throughout these sections not everything has been able to be covered and not everything included has been able to be covered in thorough detail. Instead, this piece focuses on flagging some key issues with LAOS 2022 and connects this to the wider issue of critical scholarship being passed over in policy. To make use of the words of Farzana Shain and Jenny Ozga, the ‘paper has very large ambitions and is unable to provide a comprehensive review of all relevant issues’ and it is ‘undoubtedly guilty of omission and over-simplification’ (Shain and Ozga Citation2001, 109).

Recent thinking and developments missing from LAOS 2022

LAOS 2022 does procced to state that ‘the framework has been updated to reflect recent educational reform, thinking and developments’ (DOE Citation2022a, 6) but this is again unconvincing, to this respondent. It reflects, for the most part, recent reforms, but a wealth of scholarly thinking and developments of a critical nature are missing.

Policy implementation?

While school context is frequently acknowledged, which is appreciated and welcomed, there does continue to be an emphasis on policy implementation in LAOS 2022 which totally overlooks the recent literature highlighting how policies such as SSE are not implemented but enacted in schools through interpretations and translations (Skerritt et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b). LAOS 2022 refers to, inter alia, ‘the planning and implementation of the school curriculum’ (DoE Citation2022a, 15), to ‘how the code of behaviour is understood and implemented’ (DoE Citation2022a, 28), and to how it is best practice for:

Those with leadership and management roles (to) develop and implement highly effective policies and practices that are reflective of all stakeholders’ inputs to support students’ educational, social and personal wellbeing. (DoE Citation2022a, 36)

the meaning of policy itself is frequently just taken for granted and/or defined superficially as an attempt to ‘solve a problem’. Generally, this problem solving is done through the production of policy texts such as legislation or other locally or nationally driven prescriptions and insertions into practice … The problem is that if policy is only seen in these terms, then all the other moments in processes of policy and policy enactments that go on in and around schools are marginalised or go unrecognised … Teachers, and an increasingly diverse cast of ‘other adults’ working in and around schools, not to mention students, are written out of the policy process or rendered simply as ciphers who ‘implement’. (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012, 2)

Student voice?

One of the key principles of LAOS is ‘Students as active agents in their learning’ and it is to be commended that the latest version is extended to state that students are ‘afforded the opportunity to engage in meaningful discussions with teachers to inform learning and teaching’ (DoE Citation2022a, 9). In the academic literature, as part of an attempt ‘to provoke more critical thinking regarding how student voice plays out in Irish post-primary schools vis-à-vis classroom practice’ (Skerritt, O’Hara, and Brown Citation2021c, 2) discussions focused on classroom practice have been conceptualised as ‘classroom-level consultations’ and ‘management-level consultations’ (Skerritt, O’Hara, and Brown Citation2021c), the former of which is said can represent a positive development while the latter is more concerning (Skerritt, Brown, and O’Hara Citation2021d) but no heed is paid to any of this.

While there are many cases of what could be called student voice in LAOS 2022, surprisingly there is not a single use of the term ‘student voice’. Whereas so much of this new policy is either identical to the previous one, or slightly amended, it is also notable that the following paragraph from the previous version about the quality framework facilitating ‘meaningful dialogue’ between students and others has now been removed from the latest version:

Making the quality framework publicly available will help parents and others to understand the evaluative judgements in inspection reports. The common language provided by the framework will facilitate meaningful dialogue between teachers, educational professionals, parents, students, school communities and the wider community about quality in our schools. (Department of Education and Skills Citation2016, 6)Footnote1

School Self-evaluation (SSE) and the existence of a parent and student charter will complement each other in the life of the school. SSE is vital for school improvement and the parent and student charter will be critical to securing the legitimate interest of parents and students in relation to the quality of student learning. (Department of Education and Skills Citationn.d, 7)

Professional responsibility and accountability?

Some other ‘key uses of the framework’ are for ‘Transparency, accountability and improvement’ (DoE Citation2022a, 22) as the framework is said to provide ‘a means of identifying areas for development and improvement’ and ‘a guide to support teachers and leaders in being professionally responsible, responsive and accountable to their communities’ (DoE Citation2022a, 23). A standard for school leaders is also to ‘develop and implement a system to promote professional responsibility and accountability’ (DoE Citation2022a, 25) but this indicates a fundamental misunderstanding of professional responsibility in that accountability is at odds with it. The two are not compatible:

the distinction between accountability and responsibility … is more than a matter of semantics. The former often connotes obligation and coercion, while the latter suggests professional willingness and commitment. (Cochran-Smith Citation2021, 14)

Solbrekke and Englund’s (Citation2011) distinction between professional responsibility and professional accountability is set out in , with much of the ‘Professional Accountability’ column applying to LAOS. Even for internal evaluation such as SSE, professional responsibility will be undermined when mixed with accountability.

As stated above, it was put forward in advance of LAOS 2022 that despite the emphasis on improvement in official discourse in Ireland, accountability and economic logics seem to dominate SSE, which poses a grave threat to the improvement logic and teachers’ sense of professional responsibility in that ‘attention could paradoxically be taken away from teaching, relationships, caring, and all of the other unmeasurable aspects of school life that help improve not only performances in the narrowest sense, but experiences in the broadest sense’ (McNamara et al. Citation2022, 168). Accountability reworks and erodes professional responsibility. As explained elsewhere more recently,

Accountability can unsurprisingly damage the goodwill of teachers and the busy nature and reality of teachers’ daily work means that there is not adequate time to see to all the tasks, duties, and responsibilities that they are faced with, never mind the add-ons. (Skerritt Citation2022, 9)

Table 1. Distinction between professional responsibility and professional accountability (Solbrekke and Englund Citation2011, 855).

Why distributed leadership?

As in the past, LAOS 2022 is rooted in the notion of distributed leadership. If anything, distributed leadership is more prominent in this latest policy, with the introduction now stating:

The framework also informs Circular 003/2018. This circular on leadership and management in post-primary schools sets out the leadership model for post-primary schools. It emphasises that, in accordance with the principles of distributed leadership, systems of school leadership and management should build on and consolidate existing school leadership and management structures in schools in line with best practice as articulated in the Looking at Our School framework. (DoE Citation2022a, 6)

it was inevitable that distributed leadership, or some form of post-heroic leadership, should become popular in education … The … intensification of work for those in formal management roles at or near the apex of hierarchical organisational structures, with no increase of staffing, meant it was inevitable there would be a flow of new work to others … To some extent the delegation of the new work, sometimes labelled leadership, has contributed to the popularisation of the EF perspective … especially in Ministry and Department of Education documents emphasising improvement.

Policy overload

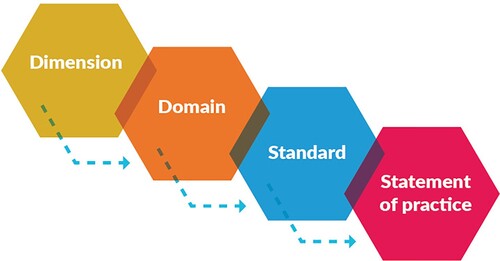

LAOS 2022 continues with the same structure as before. It is difficult to class this structure as straightforward, however, as there is a lot to come to grips with. The quality framework consists of dimensions, domains, standards, and statements of practice (see ). There are two dimensions, which both have four domains. All four domains have four standards, and every standard contains multiple statements of ‘effective practice’ and ‘highly effective practice’. Despite the common desires of policymakers for brief, concise, uncomplicated information, the idea that this kind of information may be appreciated by schools too can be lost on some makers of policy. LAOS alone is overloaded.

Figure 1. An overview of the LAOS quality framework (DoE Citation2022a, 12).

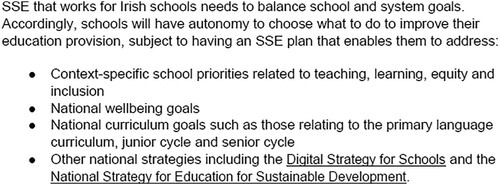

There is then further overload through the typical pretence of autonomy. The supplementary document entitled ‘School Self-Evaluation: Next Steps’ (DoE Citation2022b) lists a raft of policy areas that must be covered by schools to balance both school and system requirements (see ), and once this is done, they can then choose their own focus.

Figure 2. Balancing school and system requirements (DoE Citation2022b, 6).

Realistically, can teachers be familiar with the ‘ins and outs’ of every policy? I am with Braun, Maguire, and Ball (Citation2010) when they suggest that this would be impossible. I am also reminded of this comment made by a member of school staff when discussing SSE in a recent critical study:

There’d be a policy in this school on everything. There’s so many policies you could nearly open a library. A lot of us wouldn’t necessarily be familiar with the details of every policy and we couldn’t be, it would be unreasonable. Usually you are familiar with the policies that are most relevant to your own areas of work … Teachers wouldn’t be thinking all the time about the school self-evaluation process. It wouldn’t impinge their, I mean if you’re by and large teaching kids you wouldn’t automatically be thinking about the school self-evaluation process. It’s there in the background and it does happen but it wouldn’t be the most immediate thing as you go about your day to day work. (Skerritt et al. Citation2021a, 18)

What is effectiveness?

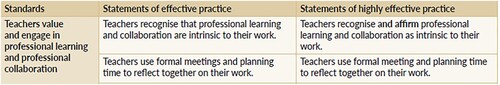

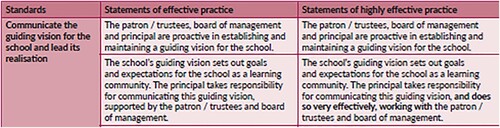

Through the statements of practice, LAOS essentially provides checklists to schools, which is problematic in itself. The statements of practice enable performances to be classed as ‘effective’ or ‘highly effective’ but what is effective and what is highly effective? Some are more distinguishable, but it must be flagged that many of the statements of effective practice are not too dissimilar to the statements of highly effective practice – they are separated by a fuzzy obscureness. On many occasions, the corresponding statements are identical. In , for example, we can see that the statements in the second row are completely identical, while in the first row the difference between effective practice and highly effective practice is that after recognising that professional learning and collaboration are intrinsic to their work, teachers being ‘highly effective’ will ‘affirm’ this. Similarly, the statements in the first row of are identical, and the difference between effective practice and highly effective practice in the second row is that as part of the latter, principals communicate the school’s guiding vision ‘very effectively’ (whatever that means!) and work ‘with’ others as opposed to being supported by them.

Figure 3. Example of statements of practice (DoE Citation2022a, 33).

Figure 4. Example of statements of practice (DoE Citation2022a, 40).

Perhaps the vagueness and the ambiguity are intentional. Not only are boxes to be ticked, but the logic of improvement offers to produce better performances while keeping perfection out of reach (Ball Citation2015) – ‘to refine practice, to always do more, to go above and beyond’ (Skerritt Citation2022, 7). The discourse of continuous improvement means that ‘we must not rest on our laurels but instead be unsatisfied with imperfect results and always strive for better’ (McNamara et al. Citation2022, 167).

Why critical scholarship is not being reflected in policy

In the education literature, it has been put forward that policy can be based on ideology, values, attitudes and beliefs (Forrester and Garratt Citation2016), personal experiences (Lupton and Hayes Citation2021), or ‘gut instinct’ (Exley and Ball Citation2011) – what in the political sciences may be referred to as the ‘irrational’ shortcut policy makers take in their decision making by drawing on emotions, gut feelings, deeply held beliefs, and habits (Cairney, Oliver, and Wellstead Citation2016; Cairney and Kwiatkowski Citation2017; Cairney Citation2019). While I am unconvinced by LAOS 2022, this is compounded by unsuccessful attempts to engage with policy makers on recent thinking and developments of a critical nature. Policy makers should have been aware of the bulk of my own critical work because it was brought directly to their attention. Almost 12 months before the publication of LAOS 2022 and the next steps, I gave a public lecture on some aspects of my work which was attended by some senior policy makers and, of course, they engaged during the Q&A session. However, my attempts to continue this relationship proved fruitless – a subsequent email containing critical papers I sent to the highest-ranking policy maker in attendance went unreturned, while another did have some exchanges with me but when I later provided them with more newly-published critical scholarship and suggestions that we continue our conversations further, the response I received was ‘I am afraid that I am not in a position to give you a department view on your paper or your research’. Public policy scholar Joshua Newman provides good food for thought:

should academics be concerned that their research is not being used to inform or influence public policy? Should they feel slighted, mistreated, ignored? This is the classic formulation of the problem: academics and other professional researchers spend vast resources and most of their time producing knowledge, much of which is potentially highly relevant for public policy, and yet policy-makers do not seem to be using it. (Newman Citation2017, 1109)

Recent education literature flags some further issues relating to the research, thinking, and developments that are indeed valued more by policy makers, which reflects the marginalised position of critical scholarship. To begin, a former civil servant with more than a decade of experience in England’s education ministry admitted to Sonia Exley that new ways of thinking tended to come ‘from groups that were aligned with what the government was thinking anyway’ (Exley Citation2021, 251). A good example being the influx of ideas and influences from the private sector into education that emphasise, inter alia, accountability, productivity, and the economy, and resonate well with taxpayers. However, there is a particular kind of academic research that does tend to capture the attention of policy makers, to some extent, and this is at the expense of critical perspectives. Hugh Lauder and colleagues note that from the 1990s policy makers in England ‘turned to the school effectiveness and improvement tradition for support, largely because its explanations, based on theories of management, were consistent with their own assumptions’ (Lauder, Brown, and Halsey Citation2009, 576). With research in education highly concentrated in school effectiveness research and in the evaluation of specific policies, Ozga also points to the rise of ‘de-contextualised, technical approaches to school improvement, especially through data use’ in the 1990s (Ozga Citation2021, 299). School improvement and effectiveness research continues to enjoy prominence today among many policy makers and researchers around the world, but to the detriment of other ontological and epistemological traditions, as eloquently articulated by (Niesche and Gowlet Citation2019, 137):

In recent times, education has been constructed as ‘in crisis’ in many parts of the globe, with positivist, instrumentalist and, more recently, school effectiveness and improvement agendas dominating discussions about how to ‘fix’ the system. Anything (be that research, policy or attitudinally) that is not seen to be moving in the direction of providing a ‘what works’ (read ‘best practice’) solution is positioned as peripheral because it is portrayed as out of touch with the day-to-day lives and realities of teachers and those working in schools. Hang on – let us rephrase this and take a moment to really absorb the logic at play here – anything that is seen to not give simple and formulaic responses to complex issues is positioned as being out of touch. There is something seriously concerning about that.

Data that are seen as objective and solution-oriented and focused on telling us ‘what works’ are deemed the best data by policy makers, and this can be obtained through school improvement, school effectiveness, and educational leadership research, if they choose to look to academia to aid their decision making. When they do engage with academics, policy makers want answers, solutions, and to know ‘what works’, or to be told that what is already in play is working, and researchers that do this, regardless of how devoid of context their research is, are more likely to be valued by the makers of policy. In policy making circles there is less of an appetite for work that is subjective, although ironically policy makers will often choose evidence that suits them, and evidence can be interpreted, re-interpreted and spun in certain ways. On the whole, critical scholarship is generally considered meaningless by policy makers. Rather than telling policy makers what they want to hear, critical perspectives will highlight, inter alia, tensions, problems, and injustices.

The need for more critical perspectives in policy making

One of the recent critical papers brought to the attention of the policy makers was published in this very journal and finished up by ‘calling for more critical discussion and open debate vis-à-vis policy formulation that pays due attention to the views of those doing SSE on the ground’ (McNamara et al. Citation2022, 168). Now, this does not seem to have happened, but it was also suggested that to do so ‘could potentially, in time, lead to conversations about revising or reforming Ireland’s Inspectorate’ (McNamara et al. Citation2022, 168). Shortly after the publication of LAOS 2022 and the next steps for SSE it was announced that the Chief Inspector had retired, and what was striking was the highly-favourable public posts of praise made by some education academics as they paid homage to the retiree, which was in stark contrast to the general reaction of members of the teaching profession. This indicates not only a lack of critical scholarship but also how the lived realities of school-based actors are not being reflected in the scholarship that is being undertaken. Moreover, if policy makers do turn to academics as part of their policy making, what kind of policy advice are they realistically given if the existing relations between them are too amiable and agreeable? There is a need for more critical perspectives to not only better reflect the experiences and perceptions of those at the coalface, but to make better policy.

Dissenters are needed in policy making. We need not only people advising policy makers but, professionally of course, challenging their thinking and questioning their decisions, and critical scholars are plausibly best placed to do this. More critical scholarship is needed, but also more value needs to be placed on critical scholarship by policy makers. As political scientists Brian Head and John Alford suggest, ‘it may be feasible for policy designers to involve the antagonists themselves in constructing a shared narrative that recognizes multiple voices, teases out the implications of … value preferences, and seeks to resolve conflicts’ (Head and Alford Citation2015, 723).

Despite the critical stance taken here, perhaps there is room for optimism in that different individual policy makers value and use academic research more than others (Newman, Cherney, and Head Citation2016). Future SSE policies in Ireland will require better policy making, and perhaps this is possible through a new-look Inspectorate. A new Chief Inspector at Ireland’s Department of Education was announced on 6th October 2022 and time will tell but maybe there will be room for more critical scholarship in policy making going forward. Maybe LAOS 2026 will be different!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Craig Skerritt

Craig Skerritt is a Lecturer in Education at the Manchester Institute of Education (MIE), University of Manchester and a member of MIE’s Critical Education Leadership and Policy (CELP) research group. He is also a Convenor of the British Educational Research Association's Educational Research and Educational Policy-Making special interest group.

Notes

1 The education ministry was named the Department of Education and Skills from 2010 up until October 2020 when it was officially renamed the Department of Education.

References

- Ball, Stephen J. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 13 (2): 10–17. doi:10.1080/0159630930130203

- Ball, Stephen J. 2015. “What is Policy? 21 Years Later: Reflections on the Possibilities of Policy Research.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 36 (3): 306–313. doi:10.1080/01596306.2015.1015279

- Ball, Stephen J., Meg Maguire, and Annette Braun. 2012. How Schools do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. Oxon: Routledge.

- Braun, Annette, Meg Maguire, and Stephen J. Ball. 2010. “Policy Enactments in the UK Secondary School: Examining Policy, Practice and School Positioning.” Journal of Education Policy 25 (4): 547–560. doi:10.1080/02680931003698544

- Cairney, Paul. 2019. “The UK Government’s Imaginative Use of Evidence to Make Policy.” British Politics 14 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1057/s41293-017-0068-2

- Cairney, Paul, and Richard Kwiatkowski. 2017. “How to Communicate Effectively with Policymakers: Combine Insights From Psychology and Policy Studies.” Palgrave Communications 3 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0001-8

- Cairney, Paul, Kathryn Oliver, and Adam Wellstead. 2016. “To Bridge the Divide Between Evidence and Policy: Reduce Ambiguity as Much as Uncertainty.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 399–402. doi:10.1111/puar.12555

- Cochran-Smith, Marilyn. 2021. “Rethinking Teacher Education: The Trouble with Accountability.” Oxford Review of Education 47 (1): 8–24. doi:10.1080/03054985.2020.1842181

- Department of Education. 2022a. Looking at Our School 2022: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: Department of Education.

- Department of Education. 2022b. School Self-Evaluation: Next Steps September 2022–June 2026. Dublin: Department of Education.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2016. Looking at Our School 2016: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2018. Leadership and Management in Post-Primary Schools: Circular Letter 0003/2018. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education and Skills. n.d. Students, Parents and Schools-Developing a Parent and Student Charter for Schools. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Exley, Sonia. 2021. “‘Opening Up’ Education Policy Making in England–Space for Ordinary Citizens’ Participation?” Representation 57 (2): 245–261. doi:10.1080/00344893.2019.1652205

- Exley, Sonia, and Stephen J. Ball. 2011. “Something Old, Something New … Understanding Conservative Education Policy.” In The Conservative Party and Social Policy, edited by Hugh Bochel, 97–118. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Forrester, Gillian, and Dean Garratt. 2016. Education Policy Unravelled. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Head, Brian W., and John Alford. 2015. “Wicked Problems: Implications for Public Policy and Management.” Administration & Society 47 (6): 711–739. doi:10.1177/0095399713481601

- King, Anthony, and Ivor Crewe. 2014. The Blunders of Our Governments. London: Oneworld Publications.

- Lauder, Hugh, Phillip Brown, and Andrew H. Halsey. 2009. “Sociology of Education: A Critical History and Prospects for the Future.” Oxford Review of Education 35 (5): 569–585. doi:10.1080/03054980903216309

- Lupton, Ruth, and Debra Hayes. 2021. Great Mistakes in Education Policy: And How to Avoid Them in the Future. Bristol: Policy Press.

- McGinity, Ruth, Amanda Heffernan, and Steven J. Courtney. 2022. “Mapping Trends in Educational-Leadership Research: A Longitudinal Examination of Knowledge Production, Approaches and Locations.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 50 (2): 217–232. doi:10.1177/17411432211030758

- McNamara, Gerry, Craig Skerritt, Joe O’Hara, Shivaun O’Brien, and Martin Brown. 2022. “For Improvement, Accountability, or the Economy? Reflecting on the Purpose (s) of School Self-Evaluation in Ireland.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 54 (2): 158–173. doi:10.1080/00220620.2021.1985439

- Newman, Joshua. 2017. “Debating the Politics of Evidence-Based Policy.” Public Administration 95 (4): 1107–1112. doi:10.1111/padm.12373

- Newman, Joshua, Adrian Cherney, and Brian W. Head. 2016. “Do Policy Makers Use Academic Research? Reexamining the “Two Communities” Theory of Research Utilization.” Public Administration Review 76 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1111/puar.12464

- Niesche, Richard, and Christina Gowlet. 2019. Social, Critical and Political Theories for Educational Leadership. Singapore: Springer.

- Ozga, Jenny. 2021. “Problematising Policy: The Development of (Critical) Policy Sociology.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (3): 290–305. doi:10.1080/17508487.2019.1697718

- Reay, Diane. 2020. “Sociology of Education: A Personal Reflection on Politics, Power and Pragmatism.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 41 (6): 817–829. doi:10.1080/01425692.2020.1755228

- Shain, Farzana, and Jenny Ozga. 2001. “Identity Crisis? Problems and Issues in the Sociology of Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 22 (1): 109–120. doi:10.1080/01425690020030819

- Skerritt, Craig. 2022. “Are These the Accountable Teacher Subjects Citizens Want?” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30. doi:10.14507/epaa.30.7278.

- Skerritt, Craig, Martin Brown, and Joe O’Hara. 2021d. “Student Voice and Classroom Practice: How Students are Consulted in Contexts Without Traditions of Student Voice.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society, doi:10.1080/14681366.2021.1979086.

- Skerritt, Craig, Gerry McNamara, Irene Quinn, Joe O’Hara, and Martin Brown. 2021b. “Middle Leaders as Policy Translators: Prime Actors in the Enactment of Policy.” Journal of Education Policy, doi:10.1080/02680939.2021.2006315.

- Skerritt, Craig, Joe O’Hara, and Martin Brown. 2021c. “Researching How Student Voice Plays Out in Relation to Classroom Practice in Irish Post-Primary Schools: A Heuristic Device.” Irish Educational Studies, doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1964564.

- Skerritt, Craig, Joe O’Hara, Martin Brown, Gerry McNamara, and Shivaun O’Brien. 2021a. “Enacting School Self-Evaluation: The Policy Actors in Irish Schools.” International Studies in Sociology of Education, doi:10.1080/09620214.2021.1886594.

- Solbrekke, Tone Dyrdal, and Tomas Englund. 2011. “Bringing Professional Responsibility Back In.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (7): 847–861. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.482205

- Youngs, Howard, and Linda Evans. 2021. “Distributed Leadership.” In Understanding Educational Leadership: Critical Perspectives and Approaches, edited by Steven J. Courtney, Helen M. Gunter, Richard Niesche, and Tina Trujillo, 203–219. London: Bloomsbury.