Abstract

This study investigates the effects of three Collaborative Reasoning (CR) strategies including pre-trained CR, scripted CR, and pre-trained + scripted (mixed) CR on the argumentative decision-making skills of primary school students. Forty-six school students were requested to write a reflective essay on a social-moral issue, and after participating in a six-week story-based CR with three different conditions, they were asked to write their reflective essay. A follow-up test was conducted two weeks later. The results showed that students in the pre-trained CR condition performed better than students in the scripted CR condition with regard to acquiring and transferring decision-making skills. However, compared to students in the mixed CR condition, the performance of the students in the pre-trained condition was lower for acquiring and transferring decision-making skills. In terms of learning satisfaction, students with the mixed CR condition declared higher learning satisfaction compared to students in the other two conditions. We discuss these results and provide agenda for future research and practice.

Introduction

Primary education is typically the first stage of formal education where children between the age of 6 to 12 go to school (Firmansyah, Citation2018). Decision-making is one of the basic and crucial skills that primary school students should acquire (Mettas, Citation2011) as in everyday life they are expected to continuously go through a decision-making process (Visscher, Citation2021), especially about real-life controversial issues (Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009). Students need to improve their critical and logical thinking skills to make informed decisions (Gutierez, Citation2015). The process of decision-making compounds complex mechanisms of human thinking (de Acedo Lizárraga et al., Citation2007) in which students need to internally process information, and identify and prioritize key points relevant to the subject (Acar, Citation2008). Scholars suggest that argumentation plays a key role for decision-making, particularly regarding controversial topics (Acar, Citation2008; Amgoud, Citation2005; Janjua et al., Citation2013).

In argumentative decision-making, decisions are commonly made based on arguments and counter-arguments (Amgoud, Citation2009; Dimopoulos et al., Citation2004). A thoughtful decision-making process on a controversial issue requires students to learn how to reason logically, argue both sides, consider arguments and counter-arguments, and finally make a conclusion (Amgoud, Citation2009; Latifi & Noroozi, Citation2021; Noroozi, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2016). Prior studies have shown that decision-making with solid argumentation strategy is a challenging task for school students (Hasancebi et al., Citation2021; Introne & Iandoli, Citation2014; Latifi et al., Citation2021; Shahali Zadeh et al., Citation2016). For example, Al-Ajmi and Ambusaidi (Citation2022) showed a low level of logical thinking skills for 11th-grade students. They found that students lack in providing proportional, probabilistic, and associative reasoning. In another study, Latifi et al. (Citation2021) reported that students fail to provide a high level of argumentation, reasoning, and criticism on a controversial issue. This could be due to different reasons such as students’ insufficient knowledge about features of good argumentation, cognitive limitations, or lack of a guideline on how to argue solidly and make a good decision (Introne & Iandoli, Citation2014; Latifi et al., Citation2021; Nisbett & Ross, Citation1980; Noroozi et al., Citation2016).

In primary schools, teachers use different instructional strategies to teach students how to make argumentative and reasonable decisions when they discuss controversial issues (Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009). One of the promising instructional strategies to improve students’ decision-making skills on controversial issues is collaborative reasoning (CR) (Moshman & Geil, Citation1998; Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009). In general, CR refers to an active engagement in collective rationality on a dialectical topic and is defined as a form of collaborative discussion that provides opportunities for students to expand their repertoire of responses to a specific topic and explore diverse perspectives (Waggoner et al., Citation1995). The main goal of CR is to improve students’ reasoning skills (Traga Philippakos et al., Citation2018; Traga Philippakos & MacArthur, Citation2020). In a CR strategy, students are typically provided with a controversial story to read and then engage in small discussions about the controversial issue (Zhang et al., Citation2016). CR strategies help with expanding primary school students’ perspectives and way of thinking, so they can see outside of the box, and think of both positive and negative sides of the issue to make a proper decision (Clark et al., Citation2003). This strategy improves primary school students’ critical thinking skills and helps them with understanding the critical elements of argumentative decision-making (Anderson et al., Citation2001; Clark et al., Citation2003; Mundwiler & Kreuz, Citation2018; Traga Philippakos et al., Citation2018; Traga Philippakos & MacArthur, Citation2020).

In a study, Traga Philippakos and MacArthur (Citation2020) found that CR strategy combined with cognitive strategy instructions based on the think-aloud strategy can improve students’ argumentation performance in opinion writing. Likewise, Zhang et al. (Citation2016) compared the impacts of two instructional strategies including CR and direct instruction (DI) on improving students’ competence as decision-makers. In this study, both groups received a controversial story called “Pine Wood Derby story”. This story was about the dishonesty of a person in the competition and the dilemma of his friend, to tell the truth to the community. Students in the CR group were invited to interact and collaborate as a group and provide their reasons and arguments on the controversial story. The teacher played the role of a facilitator in the CR group, while students in the DI group received direct instruction from the teacher. The results showed that students in the CR group showed better decision-making competence compared to students in the DI group. Similarly, Traga Philippakos and MacArthur (Citation2020) reported that CR is an effective instructional strategy to improve primary school students’ opinions in argumentative writing. Similar findings are reported by other scholars (e.g., Traga Philippakos et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, some other studies have shown that students’ reasoning performance is better when it is in a collaborative format rather than in an individual way and this is due to the occurrence of peer interaction in collaborative reasoning where students can co-construct an argument in a more sophisticated way than individually (Moshman & Geil, Citation1998).

Despite the effectiveness of the CR strategies for improving students’ argumentative decision-making skills, there are still concerns about students’ reasoning competence and high-quality argumentation performance (Brooks & Jeong, Citation2006; Ramon-Casas et al., Citation2019). Evidence shows that in the CR learning environment, students are not completely aware of the required elements of high-quality reasoning, and even in case of knowing the elements of critical reasoning, they do not know how to perform it in action (e.g., when they write reflective essays) (Brooks & Jeong, Citation2006; Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009; Tsai & Chuang, Citation2013). This suggests that students should be supported in the CR process (Karacapilidis & Papadias, Citation2001; Noroozi et al., Citation2016; Tsai & Chuang, Citation2013). Various instructional support such as worked examples (Latifi et al., Citation2020; Valero Haro et al., Citation2022), pre-training (Brooks & Jeong, Citation2006), and scripts (Noroozi et al., Citation2013, Citation2016) have been used as CR strategies to improve students reasoning and argumentation skills. For example, Brooks and Jeong (Citation2006) provided a pre-training by developing a pre-structure model based on Toulmin’s (Citation1958) argumentation model and asked students to review this structured model before they debate with peers. The findings of this study showed that pre-training can increase argument frequency. Latifi et al. (Citation2020) study also confirmed that using scripts and worked examples can improve students’ argumentation and reasoning skills in essay writing.

Therefore, what we know from the literature is that supported CR strategies are useful in improving students’ critical thinking, reasoning, and argumentation skills for competent decision-making on controversial issues (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2001; Karacapilidis & Papadias, Citation2001; Latifi & Noroozi, 2021; Tsai & Chuang, Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2016). However, what is not known in the literature is which instructional strategies can serve better and be more effective to improve students’ argumentative decision-making skills. Previous studies do not provide information in this regard. It is known that pre-trained and scripted approaches for supporting CR have been investigated independently (e.g., Brooks & Jeong, Citation2006; Stegmann et al., Citation2007), however, the impacts of these two CR strategies and their mixed effects on various aspects of argumentative decision-making skills are unknown. Thus, in this study, we aim to investigate the effects of three CR strategies including pre-trained CR, scripted CR, and mixed (pre-trained + scripted) CR on different aspects of argumentative decision-making skills of 6th-grade school students and explore to what extent students are satisfied with the learning process of the three strategies.

We also focus on exploring the extent to which students are satisfied with the learning process of the three strategies as learning satisfaction can play a key role in the active implementation of CR strategies and if students are not satisfied with the CR strategy, they might not be willing to implement it properly (Yeung & Lowrance, Citation2006). Prior studies have shown that CR as an instructional strategy plays a positive role in students’ motivation and satisfaction (e.g., Clark et al., Citation2003; Dewiyanti et al., Citation2007; Serrano-Cámara et al., Citation2014; Spears & Miller, Citation2012; Stegmann et al., Citation2007; Zhu, Citation2012). However, it is not known yet which CR strategy can result in better learning satisfaction. By saying this, the following research questions are formulated to guide this study:

What are the effects of pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR strategies on the acquisition of primary school students’ argumentative decision-making skills?

Does the transfer of primary school students’ argumentative decision-making skills differ in pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR conditions?

How satisfied are primary school students in relation to their argumentative decision-making learning in pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR conditions?

Method

Participants

This study was conducted in Iran and in this context, primary school refers to students from 1st grade to 6th grade. In total, 46 sixth-grade students participated from three classes of different schools including Mehregan, Mehrdanesh, and Bahman in the academic year 2020-2021. All three schools were public schools in the same city. The location of three schools was close to each other in an urban neighborhood where the socioeconomic status of students was almost the same. All participants were 12 years old (SD = 1.51). They were male students as in Iran, primary schools are offered separately for males and females. There were no students with special needs that may require special learning support. Students in each class were randomly assigned to follow one of the CR strategies (class A: pre-trained CR, N = 15; class B: scripted CR, N = 15; class C: mixed CR, N = 16). The intervention was conducted in the social studies course for all classrooms. Teachers were responsible to implement the intervention and they were experienced teachers with more than 5 years of teaching experience. To comply with ethical considerations, all participants were informed about the research set-up of the class and they all were given a choice to decline participation. However, none of the participants declined participation

Study design

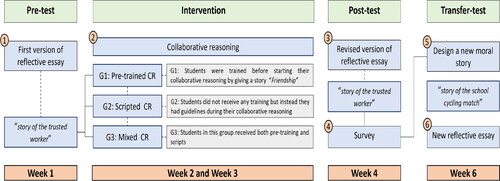

This study was a quasi-experimental research with a pretest and post-test design. The design of this study was composed of four sections including the pretest phase, intervention phase, post-test phase, and transfer-test phase. In the beginning, all students were told a social-moral story drawn from the “decision-making” chapter of the Social Studies Course and then were asked to write a reflective essay on the given story (pretest phase). The story was given to all students in the class by the teacher and then they were asked to reason and argue about that story. Later, students were assigned to three pre-trained CR, scripted CR, and mixed CR conditions, and all students followed two weeks CR process (intervention phase). Then, students were requested to revise their first draft of the reflective essay based on the reasoning they had in their conditions and then fill out the survey on their learning satisfaction (post-test phase). Finally, two weeks later, a new social-moral story was given to students and they were invited to write a reflective essay on the given story (transfer-test phase) ().

Procedure

Students followed a module of CR activity for six weeks to practice and learn how to decide on a social-moral issue given through a story (see also ). In the first week, students were provided with an introduction to the module (e.g., how to follow the module, what are the important notes and deadlines, what is the goal of this module, and what is expected from them). Then, students in all three conditions were requested to write a reflective essay about a new moral issue called “story of the trusted worker” as a pretest. This story is about a municipal worker who is poor and has been facing financial problems. One day, he has found a bag with lots of money and jewelry inside. In the bag also there was information on the owner of the bag. Students were asked to write a reflective essay on what would they decide to do with the bag. Would they keep the bag for themselves or take it back to the owner? The reflective essay was supposed to entail arguments and counter-arguments regarding the taking position and the conclusion and decision they made based on those arguments and counter-arguments. In the second week, students in the pre-trained CR group received training in the form of an example where they could practice their collaborative reasoning and argumentative decision-making skills on a given story called “Friendship” (), while students with the scripted CR condition did not receive any pre-training, however, they were provided with a guideline and question prompts on how to argue and do collaborative reasoning to decide on the given social-moral issue ().

Table 1. Pre-trained CR condition.

Table 2. Scripted CR condition.

Students in the mixed CR group not only received the pre-training but also were provided with scripts the same as the scripted CR group during their collaborative reasoning. Later, students in all three conditions started with the presentation of their position regarding the social-moral issue and discuss the positive and negative aspects of their position. All students were asked to provide ideally four arguments and four counter-arguments regarding the taken position. In the third week, students were asked to compare all the positive and negative aspects of their position and evaluate all the arguments and counter-arguments to make a conclusion and decide on the controversial issue. In the fourth week, as a post-test, students were asked to revise their reflective essays based on their collaborative reasoning in the last two weeks. In addition, they were invited to fill out a survey about their satisfaction with the learning experiences they had. Two weeks later, in week 6, a transfer test was performed to explore the extent to which students could apply their argumentative decision-making skills in a new situation for a new social-moral issue. Therefore, in the sixth week, students wrote a new reflective essay on a new social-moral story called “story of the school cycling match ().

Table 3. The procedure of the study.

Measurement

Measurement of students’ argumentative decision-making performance

Students’ argumentative decision-making performance in the reflective essay was measured by a coding scheme developed by the authors based on the review of the relevant literature (e.g., Moshman & Geil, Citation1998; Noroozi et al., Citation2016; Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009; Toulmin, Citation1958; Waggoner et al., Citation1995). The coding scheme was developed based on the structure of high-quality collaborative reasoning and argumentation for decision-making on controversial issues. The elements of this coding scheme include (a) position on the issue, (b) presentation of the positive aspects, (c) presentation of the negative aspects, (d) comparing both positive and negative aspects, and finally (e) conclusion on the decision. This coding scheme is scored differently for each element () and all given points together indicate students’ argumentative decision-making performance. Students’ performance for argumentative decision-making was measured in three phases including pretest, post-test, and transfer-test. Cohen’s kappa coefficient analysis was used to measure the inter-rater reliability between the coders and the results revealed that there is a reliable agreement between the coders in all three phases as follows: 81% agreement in the pretest, 82% agreement in the post-test, and 80% agreement in the transfer test (p < 0.01).

Table 4. Coding scheme to measure students’ argumentative decision-making skills in reflective essays.

Measurement of students’ learning satisfaction

Students learning satisfaction was measured by using a short version of the questionnaire designed by Noroozi and Mulder (Citation2017). The questionnaire includes three main categories. Items 1 to 5 include questions regarding students’ satisfaction with perceived domain-specific learning (e.g., the module broadened my knowledge on the topic; the module deepened my knowledge on the topic). Items 6 to 11 include questions about students’ satisfaction with perceived domain-general learning (e.g., the module helped me learn how to bring various pros and cons of the topic to the table; the module helped me learn essential elements of a sound argument for or against various perspectives on the topic), and items 12 to 19 include questions about students’ satisfaction with the learning task (e.g., I enjoyed working on the module; the assignments in various phases of the module were clearly formulated). The reason why this questionnaire was chosen for this study is that the items of this questionnaire not only cover students’ satisfaction with the task itself but also comprehensively cover students’ satisfaction with the general domain and specific domain of learning. All 19 items of this questionnaire were developed on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “almost never true = 1”, “rarely true = 2”, “occasionally true = 3”, “often true = 4”, to “almost always true = 5”. According to Noroozi and Mulder (Citation2017), a higher score on this questionnaire means a higher level of satisfaction. More specifically, the mean score between 1 to 2 is interpreted as students’ complete dissatisfaction with the task. The mean score between 2 to 3 is considered a low level of satisfaction. The mean score between 3 to 4 is interpreted as an acceptable level of satisfaction and above 4 is defined as a high level of satisfaction. The reliability of this questionnaire for reuse was confirmed by Noroozi and Mulder (Citation2017). For this study, high reliability was reported for all three categories (Cronbach a = 0.85, 0.86, and 0.89, respectively).

Analysis

The MANOVA for repeated measurement test was conducted to compare the effectiveness of the three CR strategies for improving students’ argumentative decision-making performance from pretest to post-test and from post-test to transfer-test. In addition, the MANOVA test was used to measure students’ learning satisfaction among the three conditions.

Results

RQ1: What are the effects of pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR strategies on the acquisition of primary school students’ argumentative decision-making skills?

The results showed that the argumentative decision-making performance of all students in three conditions improved from pretest to post-test, however, a difference was found in students’ decision-making performance among the three conditions. Students’ overall argumentative decision-making performance in the mixed CR condition increased from 3.91 (SD = 0.96) in the pretest to 12.05 (SD = 0.45) in the post-test which is a higher improvement than the other two conditions. In addition, students’ overall argumentative decision-making performance in the pre-trained CR condition was increased from 3.99 (SD = 1.13) in the pretest to 9.06 (SD = 1.17) in the post-test which is higher than the scripted CR condition ().

Table 5. Differences for argumentative decision-making skills from pretest to post-test among three conditions.

RQ2: Does the transfer of primary school students’ argumentative decision-making skills differ in pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR conditions?

The results displayed that all students’ argumentative decision-making performance in the three conditions decreased in the transfer test compared to the post-test, and this decrease was different among the three conditions. Students’ scores in the mixed CR condition decreased from 12.05 (SD = 1.15) in the post-test to 10.52 (SD = 1.35) in the transfer test which indicates less decrease in argumentative decision-making performance compared to the other two conditions. This means that students in the mixed CR condition showed a better learning transfer of argumentative decision-making skills in the new learning situation compared to the pre-trained CR and scripted CR conditions ().

Table 6. Differences for argumentative decision-making skills from post-test to transfer-test among three conditions.

RQ3: How satisfied are primary school students in relation to their argumentative decision-making learning in pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR conditions?

The results revealed a high level of learning satisfaction for all three conditions. According to the mean score difference between the three groups, there is a possibility that students in the mixed CR condition revealed a higher level of learning satisfaction (M = 4.68, SD = 0.28) compared to the pre-trained CR condition (M = 4.08, SD = 0.62) and the scripted CR condition (M = 4.24, SD = 0.41) ().

Table 7. Differences in terms of mean scores for learning satisfaction among three conditions.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the effects of three CR strategies including pre-trained, scripted, and mixed CR on students’ argumentative decision-making performance and their satisfaction with learning experiences.

Our findings showed that all three CR strategies improved students’ argumentative decision-making performance which is in line with previous studies that emphasize the positive effects of CR on decision-making skills and reasoning (e.g., Al-Ajmi & Ambusaidi, Citation2022; Anderson et al., Citation2001; Introne & Iandoli, Citation2014; Janjua et al., Citation2013; Traga Philippakos et al., Citation2018; Traga Philippakos & MacArthur, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2016). The positive impacts of CR strategies on students’ argumentative decision-making performance could be due to the nature of CR itself. In the CR approach, students are invited to engage in a collaborative learning environment where they are encouraged to share their opinions, and thoughts on the given story, hear peers’ opinions on the story and expand their perspectives and way of thinking (Moshman & Geil, Citation1998; Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009; Waggoner et al., Citation1995; Zhang et al., Citation2016). All these elements and following this process are critical to making argumentative decision-making (Clark et al., Citation2003; de Acedo Lizárraga et al., Citation2007; Edward, 2004; Gutierez, Citation2015).

We found that students in the mixed CR condition outperformed the pre-trained and scripted CR conditions both in the acquisition and transfer of argumentative decision-making skills. This finding indicates that the best CR strategy among the three mentioned strategies to support students’ argumentative decision-making performance is the combination of receiving training about CR before its use and also supporting students during the CR through scripts. One reason for this outperformance could be related to the complementary nature of both pre-trained and scripted CR strategies which together can provide strong educational support. That is to say that on one hand, the pre-trained CR strategy helps students with an understanding of the elements of good CR, and without pre-training, students may not know the basic and critical concepts of high-quality CR. On the other hand, scripted CR guides students in their reasoning process and students get support in their argumentation with their peers. Together, as the results showed, mixed CR seems to be a better CR strategy for improving primary school students’ argumentative decision-making performance. This finding is in line with previous studies that highlight the positive effects of pre-trained and scripted CR strategies on improvements in students’ argumentation competence on complex and controversial issues (Anderson et al., Citation2001; Janjua et al., Citation2013; Karacapilidis & Papadias, Citation2001; Latifi & Noroozi, 2021; Traga Philippakos et al., Citation2018; Traga Philippakos & MacArthur, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2016).

It was also found that students’ performance in the pre-trained CR condition was better than students in the scripted CR condition. This finding means that if students receive training about CR before the CR strategy, they can perform better compared to the time when they only receive support and guidance during the CR strategy. A reason to explain this finding is that pre-training helps students to learn what is a good CR and how a CR with peers should be followed. Therefore, when students follow the CR process in class, they already know what to do and how to manage their CR activity properly (Brooks & Jeong, Citation2006). When students only get support through scripts in the CR process, they only follow what they are told and they do not learn the underlying reasons why these elements of CR should be followed (Noroozi et al., Citation2016; Latifi & Noroozi, 2021).

In addition, findings revealed that students in all three conditions had a high level of satisfaction with their learning experiences. Our finding is supported by prior studies that report positive impacts of CR on students’ motivation and satisfaction (e.g., Clark et al., Citation2003; Dewiyanti et al., Citation2007; Serrano-Cámara et al., Citation2014; Stegmann et al., Citation2007). One plausible reason why students’ learning satisfaction with CR is high could be related to the social presence of students in collaborative learning environments (Molinillo et al., Citation2018). Human is naturally social and he/she can develop knowledge profoundly in a group through interacting with others (Adams, Citation2006; Banihashem et al., Citation2022). Creating such an interactive and collaborative learning environment can lead to high learning satisfaction (e.g., Spears & Miller, Citation2012; Zhu, Citation2012). Our findings also showed the possibility of higher learning satisfaction for mixed CR compared to pre-trained and scripted CR. Although our literature review did not show any relevant and similar studies to compare this result, one possible reason for students’ higher learning satisfaction in the mixed CR group can be related to the fact that students have full support in their learning process through pre-training as well as having guidelines on how to reason in a collaborative environment. Such support resulted in better learning outcomes and there is a strong correlation between students’ academic achievement and learning satisfaction (e.g., Park et al., Citation2010; Simões et al., Citation2010). In other words, students in the mixed CR condition not only received training on CR in advance but also were supported by scripts in the CR process. Therefore, their argumentative decision-making performance was supported in two ways which led them to perform better and this high performance also resulted in higher learning satisfaction.

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

This study provides insights into how CR strategies similarly or differently impacted sixth-grade students’ argumentative decision-making performance and how they are satisfied with their learning experiences. In general, our findings support CR's positive impacts on students’ argumentative decision-making performance and learning satisfaction and extend the literature on understanding the differences among CR strategies to support sixth-grade students’ argumentation competence for making decisions on social-moral issues.

This study had some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the data was collected only from one course, and students’ course domain knowledge may be an influential factor in their argumentation performance (e.g., Valero Haro et al., Citation2022), therefore, the findings of this study may not be represented largely. Future studies should be run in different courses on a large scale to see the extent to which the results obtained in this study can be generalized. Second, according to the literature, students’ argumentation and CR can be affected by their gender (Noroozi et al., Citation2020), epistemic beliefs (e.g., Nussbaum et al., Citation2008), and cultural background (e.g., Tsemach & Zohar, Citation2021). In our study, we did not consider these concepts. In previous studies, the intersection of gender, argumentation, and culture has been investigated in higher education (e.g., Tsemach & Zohar, Citation2021), but this requires further attention in primary school settings. Future studies should consider the impacts of gender, epistemic beliefs, and cultural background on primary school students’ different CR performances. Last but not least, in this study, students performed their argumentative decision-making performance in form of a reflective essay which was considered an individual performance. Therefore, our assessment was based on students’ performance in the reflective essay. What we did not explore in this study is the extent to which students’ CR processes in the three CR conditions differ from each other. How differently or similarly students performed in the CR process. For future studies, it is suggested to develop a coding scheme and conduct a study to measure the CR process itself as the main indication of students’ CR performance.

Finally, based on our findings we recommend practicals for future educational practice in the application of CR for argumentative decision-making performance in primary school settings. We found that when students receive full support (pre-training plus scrips), not only their performance is better than when they only receive pre-training or scrips, but also they are more satisfied with the learning process. This could be due to the fact that primary school students, particularly in our case sixth-grade students are not yet completely self-regulated and self-directed learners and they need support (Schunk, Citation2005; Van Deur & Murray-Harvey, Citation2005). According to these findings, we suggest teachers combine and mix CR strategies for providing full support to students.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Acar, O. (2008). Argumentation skills and conceptual knowledge of undergraduate students in a physics by inquiry class [Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University]. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1228972473

- Adams, P. (2006). Exploring social constructivism: Theories and practicalities. Education 3-13, 34(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270600898893

- Al-Ajmi, B., & Ambusaidi, A. (2022). The level of scientific argumentation skills in chemistry subject among grade 11th students: The role of logical thinking. Science Education International, 33(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.33828/sei.v33.i1.7

- Amgoud, L. (2005). A general argumentation framework for inference and decision making [Paper presentation]. 21st Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, UAI, (Vol. 2005, pp. 26–33).

- Amgoud, L. (2009). Argumentation for decision making. In Simari, G., & Rahwan, I. (Eds). Argumentation in artificial intelligence. (pp. 301–320). Springer.

- Anderson, R. C., Nguyen-Jahiel, K., McNurlen, B., Archodidou, A., Kim, S.-Y., Reznitskaya, A., Tillmanns, M., & Gilbert, L. (2001). The snowball phenomenon: Spread of ways of talking and ways of thinking across groups of children. Cognition and Instruction, 19(1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532690XCI1901_1

- Banihashem, S. K., Farrokhnia, M., Badali, M., & Noroozi, O. (2022). The impacts of constructivist learning design and learning analytics on students’ engagement and self-regulation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59(4), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1890634

- Brooks, C. D., & Jeong, A. (2006). Effects of pre‐structuring discussion threads on group interaction and group performance in computer‐supported collaborative argumentation. Distance Education, 27(3), 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910600940448

- Clark, A. M., Anderson, R. C., Kuo, L. J., Kim, I. H., Archodidou, A., & Nguyen-Jahiel, K. (2003). Collaborative reasoning: Expanding ways for children to talk and think in school. Educational Psychology Review, 15(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023429215151

- de Acedo Lizárraga, M. L. S., de Acedo Baquedano, M. T. S., & Cardelle-Elawar, M. (2007). Factors that affect decision making: Gender and age differences. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 7(3), 381–391.

- Dewiyanti, S., Brand-Gruwel, S., Jochems, W., & Broers, N. J. (2007). Students’ experiences with collaborative learning in asynchronous computer-supported collaborative learning environments. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(1), 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.021

- Dimopoulos, Y., Moraitis, P., & Tsoukias, A. (2004, September). Argumentation based modeling of decision aiding for autonomous agents. In Proceedings. IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Intelligent Agent Technology, IAT 2004 (pp. 99–105). IEEE.

- Er, E., Dimitriadis, Y., & Gašević, D. (2021). Collaborative peer feedback and learning analytics: Theory-oriented design for supporting class-wide interventions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1764490

- Firmansyah, D. (2018). Analysis of language skills in primary school children (study development of child psychology of language). PrimaryEdu - Journal of Primary Education, 2(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.22460/pej.v1i1.668

- Gutierez, S. B. (2015). Integrating socio-scientific issues to enhance the bioethical decision-making skills of high school students. International Education Studies, 8(1), 142–151.

- Hasancebi, F., Guner, Ö., Kutru, C., & Hasancebi, M. (2021). Impact of stem integrated argumentation-based inquiry applications on students’ academic success, reflective thinking and creative thinking skills. Participatory Educational Research, 8(4), 274–296. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.21.90.8.4

- Introne, J., & Iandoli, L. (2014). Improving decision-making performance through argumentation: An argument-based decision support system to compute with evidence. Decision Support Systems, 64, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2014.04.005

- Janjua, N. K., Hussain, F. K., & Hussain, O. K. (2013). Semantic information and knowledge integration through argumentative reasoning to support intelligent decision making. Information Systems Frontiers, 15(2), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-012-9365-x

- Jeong, A. (2006). Gender interaction patterns and gender participation in computer-supported collaborative argumentation. American Journal of Distance Education, 20(4), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15389286ajde2004_2

- Karacapilidis, N., & Papadias, D. (2001). Computer supported argumentation and collaborative decision making: the HERMES system. Information systems, 20(4) 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4379(01)00020-5

- Latifi, S., Noroozi, O., & Talaee, E. (2020). Worked example or scripting? Fostering students’ online argumentative peer feedback, essay writing and learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1799032

- Latifi, S., Noroozi, O., Hatami, J., & Biemans, H. J. (2021). How does online peer feedback improve argumentative essay writing and learning? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1687005

- Latifi, S., & Noroozi, O. (2021). Supporting argumentative essay writing through an online supported peer-review script Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(5), 501–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1961097

- Mettas, A. (2011). The development of decision-making skills. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 7(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/75180

- Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Anaya-Sánchez, R., & Vallespín-Arán, M. (2018). Exploring the impacts of interactions, social presence and emotional engagement on active collaborative learning in a social web-based environment. Computers & Education, 123, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.012

- Moshman, D., & Geil, M. (1998). Collaborative reasoning: Evidence for collective rationality. Thinking & Reasoning, 4(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/135467898394148

- Mundwiler, V., & Kreuz, J. (2018). Collaborative decision-making in argumentative group discussions among primary school children. In Argumentation and language—Linguistic, cognitive and discursive explorations (pp. 263–285). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73972-4_12

- Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs.

- Noroozi, O., Hatami, J., Bayat, A., van Ginkel, S., Biemans, H. J., & Mulder, M. (2020). Students’ online argumentative peer feedback, essay writing, and content learning: Does gender matter?. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(6), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1543200

- Noroozi, O. (2022). The role of students’ epistemic beliefs for their argumentation performance in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2022.2092188

- Noroozi, O., Banihashem, S. K., Taghizadeh Kerman, N., Parvaneh Akhteh Khaneh, M., Babayi, M., Ashrafi, H., & Biemans, H. J. (2022). Gender differences in students’ argumentative essay writing, peer review performance and uptake in online learning environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2034887

- Noroozi, O., Biemans, H., & Mulder, M. (2016). Relations between scripted online peer feedback processes and quality of written argumentative essay. The Internet and Higher Education, 31, 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.05.002

- Noroozi, O., & Mulder, M. (2017). Design and evaluation of a digital module with guided peer feedback for student learning biotechnology and molecular life sciences, attitudinal change, and satisfaction. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education: A Bimonthly Publication of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 45(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20981

- Noroozi, O., Weinberger, A., Biemans, H. J., Mulder, M., & Chizari, M. (2013). Facilitating argumentative knowledge construction through a transactive discussion script in CSCL. Computers & Education, 61, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.08.013

- Nussbaum, E. M., Sinatra, G. M., & Poliquin, A. (2008). Role of epistemic beliefs and scientific argumentation in science learning. International Journal of Science Education, 30(15), 1977–1999. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701545919

- Park, J. H., Lee, E., & Bae, S. H. (2010). Factors influencing learning achievement of nursing students in e-learning. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 40(2), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2010.40.2.182

- Ramon-Casas, M., Nuño, N., Pons, F., & Cunillera, T. (2019). The different impact of a structured peer-assessment task in relation to university undergraduates’ initial writing skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1525337

- Reznitskaya, A., Kuo, L. J., Clark, A. M., Miller, B., Jadallah, M., Anderson, R. C., & Nguyen‐Jahiel, K. (2009). Collaborative reasoning: A dialogic approach to condition discussions. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640802701952

- Schunk, D. H. (2005). Commentary on self-regulation in school contexts. Learning and Instruction, 15(2), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.04.013

- Serrano-Cámara, L. M., Paredes-Velasco, M., Alcover, C. M., & Velazquez-Iturbide, J. Á. (2014). An evaluation of students’ motivation in computer-supported collaborative learning of programming concepts. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.030

- Shahali Zadeh, M., Dehghani, S., Banihashem, S. K., & Rahimi, A. (2016). Designing and implementation of blending of problem solving instructional model with constructivism’s principles and the study of its effect on Learning and creative thinking. Journal of Innovation and Creativity in Human Science, 5(3), 83–117.

- Simões, C., Matos, M. G., Tomé, G., Ferreira, M., & Chaínho, H. (2010). School satisfaction and academic achievement: the effect of school and internal assets as moderators of this relation in adolescents with special needs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1177–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.303

- Spears, L. R., & Miller, G. (2012, January). Social presence, social interaction, collaborative learning, and satisfaction in online and face-to-face courses. In North Central Region Research Conference Proceedings (p. 147).

- Stegmann, K., Weinberger, A., & Fischer, F. (2007). Facilitating argumentative knowledge construction with computer-supported collaboration scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 2(4), 421–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-007-9028-y

- Taghizadeh Kerman, N., Noroozi, O., Banihashem, S. K., Karami, M., & Biemans, H. J. A. (2022). Online peer feedback patterns of success and failure in argumentative essay writing. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2093914

- Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press.

- Traga Philippakos, Z. A., & MacArthur, C. A. (2020). Integrating collaborative reasoning and strategy instruction to improve second graders’ opinion writing. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 36(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2019.1650315

- Traga Philippakos, Z. A., MacArthur, C. A., & Munsell, S. (2018). Collaborative reasoning with strategy instruction for opinion writing in primary grades: Two cycles of design research. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(6), 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2018.1480438

- Tsai, Y. C., & Chuang, M. T. (2013). Fostering revision of argumentative writing through structured peer assessment. Perceptual and motor skills, 116(1), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.2466/10.23. PMS.116.1.210-221

- Tsemach, E., & Zohar, A. (2021). The intersection of gender and culture in argumentative writing. International Journal of Science Education, 43(6), 969–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2021.1894499

- Valero Haro, A., Noroozi, O., Biemans, H., & Mulder, M. (2022). Argumentation Competence: students’ argumentation knowledge, Behavior and attitude and their relationships with domain-specific knowledge acquisition. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 35(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2020.1734995

- Van Deur, P., & Murray-Harvey, R. (2005). The inquiry nature of primary schools and students’ self-directed learning knowledge. International Education Journal, 5(5), 166–177. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ903897

- Visscher, A. J. (2021). On the value of data-based decision making in education: The evidence from six intervention studies. Studies in educational evaluation, 69, 100899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100899

- Waggoner, M., Chinn, C., Yi, H., & Anderson, R. C. (1995). Collaborative reasoning about stories. Language Arts, 72(8), 582–589. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41482243

- Yeung, D., & Lowrance, J. (2006, May). Computer-mediated collaborative reasoning and intelligence analysis. In International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (pp. 1–13). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/11760146_1

- Zhang, X., Anderson, R. C., Morris, J., Miller, B., Nguyen-Jahiel, K. T., Lin, T.-J., Zhang, J., Jadallah, M., Scott, T., Sun, J., Latawiec, B., Ma, S., Grabow, K., & Hsu, J. Y.-L. (2016). Improving children’s competence as decision makers: Contrasting effects of collaborative interaction and direct instruction. American Educational Research Journal, 53(1), 194–223. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215618663

- Zhu, C. (2012). Student satisfaction, performance, and knowledge construction in online collaborative learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 127–136.