Abstract

This article reconsiders the association, common globally and ubiquitous in Neolithic Turkey, between dead bodies and domestic architecture. Residential burial has conventionally been handled in a representational framework. Buildings’ physical and meaningful aspects are analytically separated, so that they can act as ‘containers of meaning’ in funerary contexts and as concrete technologies in others. Here, a provocative dataset challenges this separation: infant bodies and curated remains buried against the bases of unstable Çatalhöyük walls, as if to reinforce them. Rather than asking what such bodies meant, I adopt a more-than-representational approach inspired by Mol’s (2002) ‘enacting ontology’ and Barad’s (2007) ‘agential realism’ that asks what bodies could do. Doing so extracts bodies and walls from separate domains of mortuary and mechanical action, and asks how they were enacted as objects within Neolithic practice. I trace practices that enacted walls and bodies in Neolithic worlds – making walls’ futures responsive to subsurface burial. This example raises broader implications for the way archaeologists investigate spatial aspects of mortuary practice, and mortuary aspects of architecture, and more broadly the way we determine what the objects of our study are.

INTRODUCTION

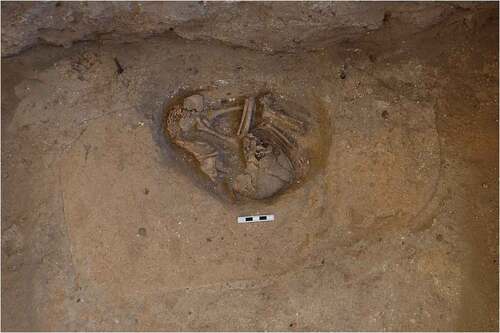

Eight thousand five hundred years ago, an infant’s body was embedded within a brick and placed against the base of a wall at Çatalhöyük in Neolithic Turkey (). This was not a one-off. Sometimes, people at Çatalhöyük embedded bodies – almost always infants or small fragments of adults – against the base of unstable structures, as if doing so might reinforce the walls. This practice challenges our interpretive comfort zones, especially the reflex to divide bodies and brickwork onto separate registers of meaning and mechanics, respectively. Instead, I develop a more-than-representational framework to suggest a much richer understanding of how walls and bodies collaborated to shape Neolithic futures. This, in turn, has implications for how we understand ‘meaningful’ aspects of architecture more broadly.

Fig. 1. Neonate embedded in a mudbrick at the base of a leaning mudbrick wall. Photo: Jason Quinlan. Courtesy Çatalhöyük Research Project.

Most archaeological approaches to counterintuitive finds like start by parsing the past into two registers: universal, material reality and culturally specific representations such as meanings, beliefs, or discourses (Alberti and Marshall Citation2009). If we see people in the past behaving in ways that do not seem fit for purpose, we often explain their actions as directed towards representations: ‘bodies don’t materially reinforce walls, but perhaps bodies represented concepts such as vitality, ownership, or care that resonated with architecture.’ Variations of this approach have driven discourse on residential burial in recent decades (Adams and King Citation2010). Representational approaches often diminish the real material, political consequences that structured past worlds. They risk quarantining the unfamiliar on a plane of meaning while expecting the ‘material side’ of things to play out in universal terms. To understand burials in the built environment, I argue, we need to move beyond what bodies and masonry represent to ask how they worked in conjunction with one another to structure futures.

Inspired by the broader material and ontological turn, I suggest a more-than-representational approach (Harris Citation2018), particularly one inspired by Mol’s (Citation1999, Citation2002) enacting ontology and Barad’s (Citation2007) agential realism. I examine human remains incorporated within, below or against mudbrick walls at Çatalhöyük in Neolithic Turkey. This approach centres not how bodies and bricks were juxtaposed but how they were enacted as definite objects in the first place. It allows us to understand more fully the way interventions like embedding bodies and maintaining walls rippled consequentially through Neolithic communities – giving material, political structure to different possibilities for action (Law and Mol Citation2008).

Below, I consider the embedding of human remains within or against the foundations of walls at Çatalhöyük East (ca. 7100–5950 BCE). Intramural burial was normative at Çatalhöyük; however, bodies were rarely placed against walls. As we will see, bodies were worked into masonry that was unstable, or especially likely to be. The first section establishes this pattern in the data. The second critiques representational understandings of intramural burials, and outlines a more-than-representational approach. The third traces details of Neolithic practice that defined walls’ and bodies’ qualities and propensities. These enacted walls that worked differently from mudbrick walls in other contexts, and that were responsive to the embedding of bodies against or below them. In conclusion, I argue that bodies embedded in walls shaped the material, political futures of structures – something only apprehensible if we take an ontologically open approach to what walls and bodies are, and how they work.

HUMAN REMAINS IN WALLS AT ÇATALHÖYÜK

Çatalhöyük East is the largest Neolithic settlement in Central Anatolia. Like nearby Aşıklı Höyük (Esin et al. Citation1991, Özbaşaran et al. Citation2018) and Canhasan III (French et al. Citation1972), Çatalhöyük was a ‘clustered neighbourhood’ settlement (Düring Citation2006). Mudbrick buildings were built wall-against-wall with few open spaces between. The architecture was traversed at rooftop level, and people descended into buildings by ladder. After standing for decades – occasionally up to several generations (Cessford Citation2005) – buildings were imploded and the rubble compacted, forming a platform for a new structure. The tell grew outward and upward throughout the first half of the 7th millennium. After 6500 BCE widespread abandonments created a sparser settlement (Marciniak et al. Citation2015), eventually shifting to a new tell (Çatalhöyük West) across the Çarşamba River around 6000 BCE.

Every building at Çatalhöyük served as living space and in ritual and political capacities. Buildings’ prominence in these roles was negotiable and shifted as they were occupied (Kay Citation2020). Each contained a changing assortment of cooking installations; storage and food processing features; and raised platforms used for burial and likely sleeping. Although it is unlikely that all bodies at Çatalhöyük were buried, those that received burial were almost always interred in houses, with no consistent bias based on age or osteological sex (Haddow et al. Citation2021). Buildings were also locations for display of feasting remains, paintings, sculptures, and deposition of artefact clusters. Although various models for Çatalhöyük social structure have been proposed (Kay Citation2020), they concur that buildings were simultaneously spaces of daily life and the negotiation of larger political affiliations.

REMAINS IN WALLS

Of the more than 800 Neolithic burials excavated at Çatalhöyük, I have compiled 35 instances of human remains directly engaged with masonry: deposited within walls, foundation trenches, or set against walls in pits or packing layers (). This count includes only bodies in direct contact with walls or buttresses, or in cuts that truncated walls. Burials near walls that do not actually touch them are excluded, to avoid an arbitrary cut-off for ‘nearness’; however, a few such bodies do appear to be aligned along walls, and may have been placed in floor packing during the construction process (Carter et al. Citation2015). Sometimes multiple bodies were incorporated in the same deposit, thus there are 41 individuals in the sample. Several walls have multiple bodies against them; only 25 walls are affected. The remains date from the earliest excavated levels to shortly after Çatalhöyük’s apogee (early-mid 7th millennium).

Table 1. Human remains in contact with masonry at Çatalhöyük East. Age categories: (Np) pre-term neonate; (N) neonate (0–6 months); (I) infant (6–36 months); (J) juvenile (3–12 years); (ado) adolescent (12–19 years); (Ay) young adult; (Ai) indeterminate adult. Data accessible at www.catalhoyuk.com/research.

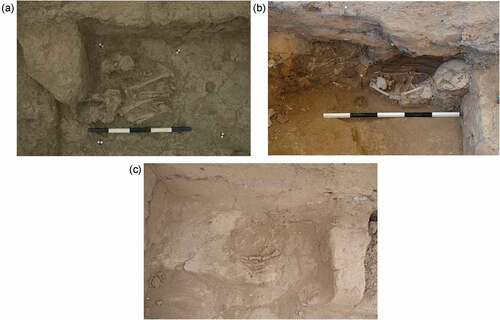

Various actions placed remains in relation to walls (). 17 of 35 features were created during construction: placed into foundation cuts dug for the walls, shortly before or after the brickwork was laid and before the cut was filled (n = 6); incorporated in levelling deposits (n = 7); dug into an underlying wall before construction of a new one atop it (n = 1); wedged between the new wall and an adjacent building (n = 1); one metatarsal embedded in mortar, and one neonate within a mudbrick high in the wall. Of remaining instances, most occurred while the building was inhabited. Some appear to be ‘typical’ burials, but in cuts following the face of the wall down (n = 7). These instances are rare among ‘typical’ burials at Çatalhöyük, and many are in rooms without other burials, suggesting that they were not simply a consequence of overcrowded burial platforms, but a deliberate juxtaposition. Other inhabitation-phase actions include cutting laterally into walls to insert bodies (n = 4) or embedding bodies in bricks or ‘ramps’ of dirt pressed against the masonry (n = 3). Four instances reflect abandonment activities: cut into walls after the last floors in a house were laid (n = 2) or placed in pits made to retrieve wall-supporting posts prior to demolition (n = 2).

Fig. 2. Human remains in and against walls at Çatalhöyük. (a) F.7330: Juvenile and neonate cranium against a buttress, in foundation packing. (b) F.1570: Infant cut into leaning wall at closure. (c) F.3681: Articulated adult fingers below bottommost bricks in a retaining wall. Photos: Scott Haddow (a), Jason Quinlan (b, c). Courtesy Çatalhöyük Research Project.

Of the 41 individuals involved, 23 are neonates. Seven are estimated 6–36 months old, and five are older juveniles. Of the five adult individuals and one adolescent, only one is a primary inhumation; four are isolated bones, and one consists of articulated fingers laid below the bottom course of bricks in a retaining wall. Only the primary adult inhumation (a possible female) could be osteologically sexed; the neonate wedged between a wall and an oven in Building 50 is genetically female (Yaka Citation2020). The demographic profile of burials in and against walls is markedly different from residential burial across the site as a whole (approximately 37% neonate/infant and 38% adult) (Knüsel et al. Citation2021, p. 318).

Altogether, these instances suggest a rare but distinctive mortuary pathway. Bodies were rarely closely engaged with masonry despite the extensive subfloor burial populations of Çatalhöyük houses. When they were, the bodies and practices that engaged with walls do not appear as a random subset of sitewide mortuary activity. Rather, the acts that placed bodies against brickwork stand out as a specific way of working with dead bodies.

ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXT

At first glance, there is little pattern to the architectural context of these bodies. Most conventional ways to assess the context of residential burials – in relation to other traits of the spaces that contain them – are equivocal. A total of 17 bodies in/against walls appear in houses that contained 10 or more other burials (e.g. Buildings 1, 17, and 77), while 4 bodies are the only known burials in their respective buildings (Buildings 2 and 45). The buildings in question range from among the most visually elaborate (e.g. Buildings 1, 77 and 131, all rich in sculpture and painting) to among the simplest (e.g. the virtually unadorned Building 56). The walls with bodies in/against them appear in main rooms, side rooms, and as partition walls between rooms; in ‘clean’ elevated areas of houses (where intramural burials are often found) and ‘dirty’ areas associated with cooking and storage.

However, these bodies were not only associated with buildings or rooms – they touched masonry. I reviewed field documentation, annual reports and excavation monographs to understand the architectural characteristics of the 25 walls with bodies against/below/within them.Footnote1 The results are summarized at right in . Most walls reveal particular structural concern or attention. Nine bear evidence of chronic instability such as repairs (n = 5) or a dramatic lean (n = 4). Eight have masonry reinforcements, a rarity at Çatalhöyük in the periods under consideration (see below): brick buttresses or unusually complex foundations (revealing concern already at the time of construction), or else retaining walls added alongside them (sometimes at the same time as the ‘main’ wall was built, but often after a period of use). Four walls sit atop midden sediments rather than the more stable footing of an older building. In total, 18 (72%) of the walls met one or more of these criteria, while seven were ‘typical’ early to mid-7th millennium walls, standing atop older walls and without reinforcement or repair.

Although instability and mitigating measures are common at Çatalhöyük, human remains appear preferentially in unstable walls. To understand the overall incidence of instability, I reviewed field documentation of walls from Level North G, a large exposure of Neolithic buildings from the mid-7th millennium. This broadly samples architectural diversity around the time most of the bodies were embedded in walls. 24 of 182 walls reviewed (13%) met one or more criteria for instability explored above. This figure may be somewhat low: some walls in the sample have not been excavated to their foundations, where additional signs of instability could be located. Nevertheless, the dramatic difference in rates of instability/reinforcement in the walls with human remains suggests that bodies were deliberately incorporated into unstable or at-risk structures.

The timing of bodies’ incorporation reinforces the sense that they were part of architectural projects. The sample is, admittedly, small. But notably, among walls built on midden or supported by buttresses – walls whose stability was likely a concern before construction began – six of seven bodies were added during initial construction. By contrast, walls with visible repairs or retaining walls supporting them have roughly equal numbers of bodies added at construction (n = 7) and during occupation (n = 6), suggesting response to emerging instability.

RETHINKING BODIES IN HOUSES: BEYOND WHAT THEY REPRESENT

The most straightforward way to understand the practice of embedding bodies against unsteady walls is that Çatalhöyük people meant to reinforce walls in this way. However, this explanation pushes against the conventional conceptual guardrails archaeologists keep around burials in buildings.

Archaeologists have explored a range of interpretations of burials in buildings, many of which provide informative parallels for the bodies above. Infants are notably singled out for burial within buildings in many societies (Yıldırım et al. Citation2018). More generally, archaeologists’ main routes for understanding burials in houses include that the practice:

Kept people, especially infants, close out of sentiment (see critical review in Eriksen Citation2017)

Was the appropriate treatment of people with certain identity traits (Hofmann Citation2009, Sullivan and Rodning Citation2010, Çevik Citation2019)

Was apotropaic or prosperity magic, based on understandings of the dead as liminal beings with vital potential, able to intervene in events on behalf of the household (Moore Citation2009, Tibbetts Citation2017, Yıldırım et al. Citation2018)

Manipulated, enhanced or sanctioned the social status of a household (Laneri Citation2010, Brereton Citation2013, Carter et al. Citation2015)

Comprised a form of memory- or history-making (Guerrero et al. Citation2009, Hendon Citation2010, Joyce Citation2010, Hodder Citation2018)

These approaches are not mutually exclusive, and most authors draw on several ways of understanding bodies. Several have been particularly useful to archaeologists interrogating bodies and buildings at Çatalhöyük. For example, Tibbetts (Citation2017), noting the close connection between infant death and architectural construction, argues that the unfulfilled potential of lives cut short gave infants a special form of animacy, which was channelled back into communities by embedding infants in architecture. Carter et al. (Citation2015), following Moses (Citation2008), note that some buildings contain too many recently dead infants in construction contexts to derive from a single household. While Moses views the occurrence of multiple, apparently simultaneous deaths as possible evidence of infanticide, Carter et al. suggest that pooling infants from large social networks (i.e. large enough to ‘contain’ several recently dead infants without necessarily needing to kill any) helped to sanction and position new households in the broader social fabric.Footnote2 Meskell (Citation2008) and CitationHodder (Citation2018) have both focused on the curation of remains, and the way ultimately embedding those remains in buildings may have negotiated histories within which houses were made meaningful. These contributions stand out within a rich broader debate about deathways in Neolithic southwest Asia, which have explored, e.g., the contrasts between residential and non-residential burial practice (Guerrero et al. Citation2009, Plug et al. Citation2021), different scales of memory (Kuijt Citation2008, Baird et al. Citation2017), differences in mortuary treatment along lines of identity and kinship (Pearson et al. Citation2013, Yaka Citation2020). All of these contributions help to understand the links between death and architecture at Çatalhöyük and provide entry points that I will follow below.

However, in each approach discussed above, the objects of burial action are to some extent abstracted from the physical house: bodies act most directly upon memory, identity, or danger, and only secondarily on bricks, mortar, floors and yards. As McAnany (Citation2010, p. 138) puts it, architecture appears in many residential burial studies as a ‘container of meaning’ – i.e. as a primarily conceptual entity. Hendon (Citation2010, p. 12) discusses this risk of reifying memory (and we could add identity, status, etc.) as an entity that exists behind material action, rather than an emergent dynamic of action. This reification places houses on two, uncomfortably separate registers: on one, as architecture (a material structure that endures or falters due to mechanical properties of its construction) and one, as a meaningful container (potentially full of bodies, with less role for the brick and mortar).

I suspect there is a great deal of truth to the idea that Çatalhöyük people understood infants as sources of vitality, and that gathering bodies helped to situate houses in the broader social fabric. It seems indisputable that, in some way, burials shaped social memory; refigured the meaning of the house and household; and negotiated people’s understandings of life and death. But it is still possible to extract out of these positions a sense that the link between houses and bodies was one of thought or belief. The objects of action are still in the mind, however much they extend through the material.

A MORE-THAN-REPRESENTATIONAL APPROACH: ENACTING OBJECTS

There is more to be said about the way ‘vitality’ and ‘the social fabric’ are enacted in – to some extent, simply are – the mechanics of mudbrick walls than we have yet captured. A more-than-representational approach explores this possibility.

More-than-representational approaches vary widely, as a part of the broader material, relational turn in the humanities and social sciences (Alberti and Marshall Citation2014, Crellin et al. Citation2021). What they share is their focus on material events where ideas and discourse are not fundamentally separate from the material world in which they operate. Rather than presupposing a ‘real’ object (say, a stone axe) and a secondary, overlain ‘meaning’ or ‘idea’ (the stone axe as an archaeological type exemplar), more-than-representational theory collapses these distinctions by attuning to unfolding events where thought, experience, and physical histories emerge together in equally concrete ways. I use the term ‘more-than-representational’ rather than the more common ‘nonrepresentational’ (Anderson and Harrison Citation2010) or ‘anti-representational’ (Alberti and Marshall Citation2009). Non-representational theory is often mistaken for a rejection of phenomena conventionally discussed as representations, e.g. symbols, ideas, discourse, and subjectivity (Doel Citation2010, Harris Citation2018). However, most non-representational thinking simply insists that ‘representations’ are no less materially constituted than other phenomena: not shadows of ‘real things’, nor vice versa. In a more-than-representational view, concepts and discourse are historical phenomena, because they shape and are shaped by events (including talking, writing, painting, and much more) that configure material reality and negotiate its future. A stone axe would be unlikely to be dug up, cleaned and placed in a glass case without archaeological typologies, nor would those typologies have developed without the excavation, manipulation, drawing and publication of axes. In this way, ‘meaning is an ongoing performance of the world’ with very physical consequences (Barad Citation2007, p. 335).

I am especially inspired by Mol’s (Citation1999, Citation2002) enacting ontology approach and Barad’s (Citation2007) agential realism. These share a core idea: that objects with determinate size, scope, qualities and capacities only emerge in interactions. As Mol (Citation1999, p. 75) puts it, ‘reality does not precede the mundane practices in which we interact with it, but is rather shaped within these practices’. Barad’s (Citation2007, chap. 3) account of experimental physics provides a (deliberately) simple example. Under different experimental conditions, some physical objects (such as light) may behave as particles at some times and energy at others – despite fundamental logical and practical contradictions between these conditions. It is only when engaged by particular experimental apparatuses (the social and material events within which particles interact) that light operates as a wave or particle, with measurable qualities and manipulable futures. Mol’s (Citation2002, Citation2015) ethnographies of medicine complicate this basic premise, showing how the apparatuses of hospital practice such as questionnaires, language barriers, budget spreadsheets, anaesthesia and misogynist surgeons all play a part in enacting bodies as objects with definite qualities like disease, sex, or dis/ability. The precise combination of these that comes to enact a given body may shape the way that body is diagnosed, treated, scarred – in dire cases, whether it can carry on living at all. What a body is, and what it can possibly become, are at stake. All of this forms a ‘material politics’ (Law and Mol Citation2008) where the possible futures that a body (or particle – or wall!) might arrive at depend upon exactly how it is enacted as a definite object in practice.

These approaches are thus forms of ontological inquiry, but with a distinctive angle: we are invited to think about the nature of walls and bodies emerging in the ways that they are worked with. This way of exploring archaeological objects aligns selectively with other ontological approaches and has a number of profound implications for how we understand past worlds:

It means that we cannot expect past worlds to have been populated by the same kinds of objects that make up our own (Lucas Citation2013). Past people did things differently and thus enacted different kinds of objects. Even familiar things like walls or axes could have had unfamiliar qualities or potentials.

Equally, it means that ontology is not an all-encompassing structure of reality. An enacting approach assumes that diverse practices structure reality in different ways (Harris and Robb Citation2012). Thus, although close examination of practices may highlight the alterity of past worlds, the goal is not to attribute societies with overarching ontologies (‘animist’; ‘relational’) but to investigate ontology at work in specific events.

To some extent, objects are defined by how they might shape the future, in collaboration with humans and other things. This is why Mol (Citation1999, Citation2008) refers to enacting objects as material politics, because by enacting objects, the futures of clay, flesh, stone (etc.) are contested.

All matter is worked with differently at different times. So the same stone, flesh or clay can take on different (even contradictory) capacities and qualities – over time, or even simultaneously (Jones et al. Citation2016). Thus, the world isn’t made up of a set list of things; it is made up of partially-overlapping ‘multiples’ (Mol Citation2002).

Archaeologists have drawn on enacting approaches to understand the nature of archaeological evidence in the present (Lucas Citation2012, pp. 175–178, Fowler Citation2013, pp. 40–43) and to study enactments of objects in the past (Alberti and Marshall Citation2014, Jones et al. Citation2016, Crellin Citation2020, pp. 113–114). Beyond direct invocations of Mol’s and Barad’s work, archaeologists have arrived at similar ideas from various more-than-representational starting points (e.g. Bailey and McFadyen Citation2010, Harris Citation2018). This broader range of thought around the ontological implications of practice forms a platform for rethinking bodies in walls.

ENACTING WALLS WITH BODIES AT ÇATALHÖYÜK

One implication of a practice-based approach to ontology is that, in order to define how walls worked, we have to investigate the arrays of practices that engaged with them, and how these practices responded to clay and sand, texture and angle, memories and promises. It was in such interactions that the walls and bodies of Çatalhöyük became objects with precise boundaries, capacities, vulnerabilities and possibilities. Within the entangled material world of Çatalhöyük, where humans and things emerged in constant dialogue with one another (Hodder Citation2012), there was no definitive list of what existed or what acted on anything else, independent of specific moments of interaction. Only in interaction did ‘a differential sense of being – with boundaries, properties, cause, and effect – [become] enacted in the ongoing ebb and flow of agency’ (Barad Citation2007, p. 338).

This section explores practices that enacted walls at Çatalhöyük. Space does not allow a comprehensive account (see Love Citation2013, Tung Citation2013, Barański et al. Citation2015, Citation2022, Doherty Citation2020). Rather, I am interested in practices that enacted walls’ durability and that seem unintuitive to western structural mechanics. I trace two such sets of practice that configured walls in two ways: walls included what was below them, and walls stood or fell depending on whom they could gather together. The final set of practices highlights that infant bodies and isolated adult remains, as enacted at Çatalhöyük, were well fitted to engage with walls’ durability. The discussion brings these three facets together, showing how bodies may indeed have made tenuous architecture more likely to endure.

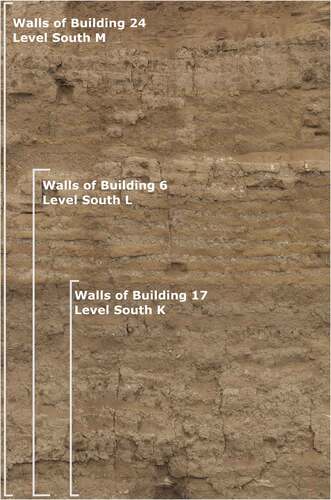

WALLS INCLUDED WHAT WAS BELOW THEM

It is at their foundations that Anatolian Neolithic mudbrick walls differ most dramatically from mudbrick walls elsewhere. At Çatalhöyük, imploded structures formed the foundations for new walls in almost all cases. By the mid-7th millennium, sequences of rebuilds spanning hundreds of years reached deep into the tell (). The combined social and technical ramifications of this practice have been widely remarked (e.g. Hodder and Pels Citation2010). Superimposed construction gave stability, with old structures effectively serving as very deep foundations. Atop these foundations, most Çatalhöyük walls through the early-mid 7th millennium were built simply, without stabilizing techniques like compound masonry or buttressing.

Fig. 3. The walls of Building 24, incorporating the buried structures Buildings 6 and 17. Photo: Jason Quinlan. Courtesy Çatalhöyük Research Project.

However, its mechanical benefits do not explain away the practice of superimposed construction. The small number of walls built on previously open space are exceptions that prove the rule: well-known techniques could stabilize a wall without superimposition, including retaining walls, deep-cut or compound foundations, or buttresses (Barański et al. Citation2022). Rather, the general tendency to build atop older, buried walls tell us about the apparatus of Çatalhöyük practices, in relation to which qualities like extent (where does one wall end and another begin), importance and durability could emerge. It was this apparatus that enabled the less intuitive stabilizing techniques discussed in this paper, in part precisely because of the way Çatalhöyük practice incorporated the subsurface within walls.

The practice of superimposed construction meant that, as walls were built and futures planned, structures incorporated matter already buried in the tell. Earlier structures were exposed and their brickwork integrated into new walls. Although archaeologists habitually divide the stacked architecture into sequential units, it is more accurate to consider them like nesting dolls, each new structure incorporating all prior structures below it. Building walls that relied on buried structures, rather than buttresses, enacted objects that stretched deep into the subsurface. It also relied on precise curated knowledge of the tell’s subsurface. This is especially true where old walls had been buried and invisible for decades or even centuries (e.g. Farid Citation2005a, p. 304).

Representational approaches might prioritize either the ‘meaningful’ or ‘mechanical’ aspects of building superimposition at Çatalhöyük. Perhaps building atop old walls was a convenient technical solution that was embellished into beliefs about history; or perhaps houses were institutions that were strengthened by rebuilding (Hodder and Pels Citation2010), while the mechanics were a side-effect. A more-than-representational approach collapses these aspects. Superimposed masonry emerged from different actions than mudbrick walls built otherwise and took on different propensities for future change. Meanings that emerged in this action were no less material in their consequences.

WALLS STOOD OR FELL DEPENDING ON WHOM THEY COULD GATHER TOGETHER

Walls at Çatalhöyük were never finished products. Although careful connections to matter below them provided deep foundations, they were still thin structures of unbaked clay atop a geomechanically active mound (Barański et al. Citation2015), in a high-altitude mosaic wetland characterized by seasonal swings from cold to hot and wet to dry. Without regular maintenance, they would have rapidly deteriorated. In this regard, they were not unlike mudbrick walls in other places and times, tied together by the vibrancy of clay as a material (e.g. Boivin Citation2000).

However, the precise ways maintenance was practiced at Çatalhöyük sets them apart from mudbrick walls elsewhere: in particular, the frequency and sheer count of maintenance episodes per wall. Most Çatalhöyük walls – including virtually all walls in main dwelling rooms – are coated with fine marl plaster layers. Some are no thicker than a millimetre, and they number dozens to hundreds on each wall (to a maximum of ca. 450 layers: Matthews Citation2005). Comparisons of plaster counts to radiocarbon dates suggest at least one coating per year in most main rooms, likely more in many buildings (Matthews Citation2005). Experimental work (St. George Citation2012) suggests that efficient plastering may have required more than a dozen workers. Afterwards, houses may have been disused for several days while the plaster dried.Footnote3

Mudbrick walls everywhere place conditions on the future: they will be maintained, or they will decay. However, the ‘obsessive’ plastering on Neolithic walls and floors has always been something of a puzzle (Karamurat et al. Citation2021, p. 38). In many ethnographic contexts, such maintenance can be, and often is, put off for years by coating walls in thick plaster layers (e.g. Horne Citation1994, pp. 140–141). Where maintenance happens annually or more, the rationale often involves religious/political calendars or alternative ontologies of clay (Boivin Citation2000). Çatalhöyük maintenance practices did not minimize effort or frequency. Quite the opposite. Working-groups were mustered, sometimes multiple times a year, to carry out plastering work for each house on the tell. These groups may have included significantly more people than routinely inhabited a given house, and when the job was done, the house’s usual inhabitants may have been temporarily displaced, relying on other living quarters.

Walls at Çatalhöyük were enacted as high-maintenance machines. Much as walls today, with their inclusions of plumbing and wiring, rely on specialist labour mustered through the capitalist market, Çatalhöyük walls’ durability relied on a social apparatus. Where walls could generate a steady rhythm, gathering-in and dispersing human bodies through social networks, they could stand for decades or even generations. By contrast, walls where no such rhythm was sustained quickly deteriorated. Excavators have noted this in several houses, where sloughed-off plaster and fallen sculptural elements reveal that caretaking was withheld for a time prior to demolition (e.g. Yeomans Citation2013). The mechanical futures of Çatalhöyük walls hinged as much (or more) upon human labour, commitments and relationships as upon buttressing and other aspects that look mechanical to our eyes. This fact was embraced, and amplified, in the way they were built and maintained. If the challenge of accounting for wall maintenance – how were sufficiently large social networks assembled to allow it to happen? – sounds reminiscent of the debate around infant deposition discussed above – how were sufficiently large social networks assembled to allow multiple infant burials at one time? (Moses Citation2008, Carter et al. Citation2015) – this may point to a critical interface: practices enacting bodies and practices enacting walls could reinforce one another (or indeed be one and the same).

BABIES AND FRAGMENTS OF ADULTS CREATED GATHERINGS BY MODIFYING THE SUBSURFACE

The variety of Çatalhöyük deathways is staggering. Some bodies were buried promptly; others possibly desiccated or excarnated (Pilloud et al. Citation2016). Bodies could be bound in cords, cloth, baskets or boxes; disarticulated, rebundled, mixed together (Haddow et al. Citation2021). Burials were often reopened to remove skeletal elements or add new bodies. Thus, one burial often prompted later action in the same location, relying on precisely spatialized knowledge of the subsurface below each house. Most mortuary activity focused on raised, plastered platforms within houses; however, secondary and tertiary remains (Haddow and Knüsel Citation2017) and infants (Tibbetts Citation2017) are more spatially varied.

Not all Neolithic bodies worked in the same way. It is not just that there was room for improvisation or diversity within mortuary practices. The actions and associations in which bodies were involved varied tremendously and, in a more-than-representational framework, we are invited to consider that this enacted truly different kinds of object (Eriksen Citation2020). Here, I focus the enactment of infant bodies and curated adult bones as depositional objects – the small subset of Çatalhöyük deathways that culminated sometimes against the foundations of unstable walls. If walls’ durability was made tangible and manipulated by establishing subsurface connections and rhythms of gathering and dispersal, how might embedding specific human objects have intervened in architectural futures?

Infant bodies were often handled distinctively. Infants are the only demographic recurringly buried in side-rooms (associated with storage and processing of foodstuffs) and near ovens/hearths. They are overrepresented in foundation contexts, with some buildings containing too many recently dead infants in construction layers to represent natural deaths in a household (Moses Citation2008, Carter et al. Citation2015). Many are recovered in baskets or other containers, suggesting that they were handled differently than adults, perhaps more portably. As with adults at Çatalhöyük, dental morphometrics and genetics demonstrate that infants were rarely buried in the same house as close biological kin (Pilloud and Larsen Citation2011, Chyleński et al. Citation2019, Yaka Citation2020). On these grounds, Carter et al. (Citation2015) suggest that dead infants operated as partible parcels of communities that could be ‘gifted’, transported, and buried in buildings. Space does not allow a full expansion here on how the intertwined practices of birthing a neonate, caring for it, potentially killing it, bundling and transporting it, embedding it alongside other recently dead infants produced the specific objects that dead infants were (cf. Eriksen Citation2017). But in short, by enacting bodies as simultaneously portable, recombinatory and yet intimately tied to place-making, the practice of gifting dead babies allowed reformulation of people’s commitments to collaborative projects.

Detached elements of adult bodies may also have circulated as a way of affirming commitments and relationships (Meskell Citation2008, Karamurat et al. Citation2021). Even more than infants, it is clear that curated remains were integral to the enactment of depth at Çatalhöyük: a vital part of most walls’ stability (see above). In a range of practices, they provide tangible links between the tell’s surface and buried material. Many curated remains likely originated by reopening primary burials and removing skeletal elements. Curated remains were also frequently redeposited in ways that drew on – and visually or rhetorically demonstrated – detailed spatial knowledge of what lay below ground. For example, archaeologists have caught Neolithic people in the act of:

burying a bodyless head in the precise location where – years before and metres below – the headless body of a different individual was buried (Farid Citation2005b, pp. 274–275)

pulling the teeth from a person’s cranium, burying the body; then after the house in question was inhabited, demolished, and rebuilt (likely years later), burying the teeth alongside other curated remains in the exact same location (Hodder and Farid Citation2013, p. 19)

burying a cache of skulls and obsidian mirrors in precisely the spot where – metres below – a person was buried with a collection of skulls and an obsidian mirror in their hand (Tripković Citation2017, p. 44)

Such vertical connections have long impressed archaeologists, prompting conversations about history-making and social memory at Çatalhöyük (Meskell Citation2008, Hodder Citation2018). But they are also conspicuously precise in their spatiality, and this has been less discussed. It is not just that people at Çatalhöyük took account of history in the way they made communities – that history had a precise physical form and location, buried below people’s feet. The ability of infant remains and isolated adult body parts to engage with this subsurface world and to centre it in ongoing community relations would have given them special force in negotiating material futures, especially when those futures were fundamentally tied to things ‘down there’ and ongoing commitments to place.

FROM MEANINGFUL CONTAINERS TO MATERIAL FUTURES: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

These brief explorations of architectural and mortuary practice converge. Within the more-than-representational framework traced here, walls never simply have mechanical traits like durability, full stop. Rather, their durability is enacted within a social, material apparatus: within practices. At Çatalhöyük, the apparatus that rendered durability visible and worked upon it relied on two, non-universal dynamics: (a) revealing and articulating walls with subsurface remains and (b) establishing broad interpersonal networks committed to gathering and maintaining a structure. Likewise, not all bodies at Çatalhöyük were the same kind of object. Infant bodies and fragments of adults were especially enacted in ways that created points of reference in the subsurface and generated commitments to places, people and projects. In short, they were precisely fitted to the kinds of apparatus in which walls’ stability was worked upon. Ultimately, it is unsurprising to find these kinds of objects working in tandem.

Considering bodies as part of the apparatus within which walls could endure opens new insights into past practice. Like fitting a lens onto a microscope so that previously unimaginable aspects of the world become actionable parts of it, fitting bodies into walls amplified people’s abilities to work on architectural challenges. And by attending to bodies, not as a ‘meaningful’ appendage to walls but a part of their enactment, we can start to follow that spotlight as people navigated specific challenges in Neolithic life. Despite the small sample size, there are tantalizing hints of diversity in the dataset presented here. When bodies were buried below the lowermost bricks of a wall, perhaps they amplified people’s encounters with footing: the textures and pressures, old walls and soft midden sediments that turned up as trenches were dug. When they were placed alongside the foundations of walls, perhaps they amplified people’s sensitivity towards emerging signs from the masonry itself during construction, helping them to determine how successfully the build was progressing. Certainly, bodies added during wall repair or reinforcement suggest a particularly amplified attention to instability after it had already emerged – and to the shared consequences to communities of faltering architecture. Each of these amplifications created vectors for sustaining walls into the future that walls without bodies did not possess. At the same time, using bodies as part of an apparatus for enacting durable architecture reminds us that human beings are equally enacted objects, neither timeless nor autonomous in our capacities, and prone to being used in the projects of others (Eriksen and Kay Citation2022).

My argument goes beyond conventional interpretations of residential burial, precisely because it does not start by asking what houses or bodies represented. Representational interpretations might discuss the way bodies in walls manipulated social memory, reflected personhood, affected the political positioning of a house, or similar. They might be right about a great deal. But the first step of such analyses divides walls’ and bodies’ conceptual and physical existence from one another, letting bodies work upon walls’ ‘intangibles’ (and rendering memory, politics and personhood intangible in the process). The real stakes of representational action are too often unclear. By contrast, the objects of the action in my account are more than conceptual. Embedding bodies was one technique to intervene in the conditions under which mechanical futures (strong or faltering walls) were negotiated. I fully agree that it simultaneously helped to situate houses and people in the fabric of Çatalhöyük communities (Carter et al. Citation2015), but not because architecture had an overlain register of political meaning. Rather, actions that produced walls also had ramifications for human experiences, bonds, antipathies, memories, indeed for life and death.

Thus, the argument here is not anti-representational (Harris Citation2018). The apparatus within which walls’ durability was made visible and manipulable included phenomena that archaeologists regularly describe as ‘representations’. These included performances of digging and revealing the subsurface of the tell; storytelling and memory to sustain that knowledge while the subsurface was invisible; negotiation, social obligations, and gift-giving as working groups larger than the day-to-day inhabitants of a house were mustered. Perhaps, in some instances, fraught spectacles of violence played a role, if infant bodies or articulated fingers were ‘sourced’ forcibly (Haddow and Knüsel Citation2017, cf. Eriksen Citation2017).

A more-than-representational approach does not deny thought, spectacle or performance, but integrates these more richly with the material, political dynamics of past worlds. Change in the material is not separated out from the process of negotiating social structure; in this approach, social futures are material futures (Crellin Citation2020). Thus, observations about bodies in buildings do not point to ways people negotiated ‘memory’ or ‘status’ as reified abstracts. They point to ways memory and status were practiced, in tandem with a house and all the lives that were lived with it (Hendon Citation2010). A fuller treatment of houses at Çatalhöyük would show that architecture, living space and domestic life were not enacted in one coherent way. Rather, an array of practices and communities enacted houses as different kinds of object, with different (and sometimes contradictory) qualities, capacities and potential futures. Archaeologists have called for a greater attention to how past futures were negotiated (Gardner and Wallace Citation2020), and a more-than-representational approach is the best available tool to do this.

The embedded bodies in walls at Çatalhöyük resonate with other practices in Neolithic southwest Asia. Fagan (Citation2017) has described the architecture of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey as ‘hungry’, arguing that the site’s stone enclosures were situated in roles that demanded feasts (and potentially bodies) to be brought into them. There is obviously much more to be said about the widespread practice of curating bones or bodies and embedding them in significant locations in the Neolithic (Kuijt Citation2008, Guerrero et al. Citation2009, Karamurat et al. Citation2021) in light of an enacting approach. And Çatalhöyük was not the only place where building atop precisely located, buried remains was an important part of the architectural apparatus (Baird et al. Citation2017, Hodder Citation2018, Özbaşaran et al. Citation2018, Plug et al. Citation2021). In an enacting approach, fine differences of practice sometimes matter much more than overall similarities; however, it seems likely that further study might begin to construct a broader geography of ontological practice (and ontological difference) in the Neolithic past.

However, the approach taken here suggests specific ways of looking for difference in the Neolithic. In particular, it resists the urge to expect ontological insights to coalesce into a coherent philosophical system. An enacted ontology cannot be a strengthened word for past ‘worldviews’, with the implication that there were abstract doctrines governing past worlds that archaeologists should aim to explicate (cf. Arponen and Ribeiro Citation2014, Alberti Citation2016). The question is not what ‘ontological key’ unlocks a particular space and time (Borić Citation2013, p. 44, cf. Fagan Citation2017), i.e. whether the Neolithic world as a whole was animistic, totemistic, etc. An enacting approach may also differ from ontological analyses that lay out ‘a new philosophy of society’ (DeLanda Citation2006) or ‘a new theory of everything’ (Harman Citation2018), insofar as their implicit end-product consists of overarching frameworks for how the universe is structured. These approaches can, undeniably, generate insights in other ways. But the value of Mol’s and Barad’s thinking for archaeology lies in de-totalizing ontology, making it inhere in practice rather than in worlds or the world writ large (Alberti and Marshall Citation2014). In line with important strands of other more-than-representational approaches (e.g. Harris and Robb Citation2012, Lucas and Witmore Citation2021) – an enacting approach explores ontology from the bottom up. It therefore embraces multiplicity. Neither walls nor people at Çatalhöyük need have been consistent in their ontological commitments.

To the contrary, in different practices, distinct objects with different qualities and potentials populated Çatalhöyük’s world. We can therefore investigate the productive tension between ways of working with the world that constituted past politics. What a wall could do was never settled once and for all at Çatalhöyük, because what a wall was depended on how it was worked with. What walls, and the communities that lived with them, could possibly become pivoted around questions of depth, commitment, gathering and dispersal, and could be made to pivot around bodies embedded invisibly in their foundations. In this way – sometimes – embedding a dead infant in a brick wall literally did strengthen the structure.

Acknowledgements

This research sometimes wobbled and was supported by broad social networks. Special thanks are owed to Scott Haddow, Marek Barański, Marianne Hem Eriksen, Oliver Harris, Jess Thompson, Rachel Crellin, and anonymous reviewers who read it in various iterations. It grows out of PhD research funded by the Cambridge Trust, with constant support from the Çatalhöyük Research Project. Any lingering instability remains my own responsibility.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Where remains contacted walls in a corner, data reflect traits in either wall; the two walls count as one in my calculations.

2 There is no direct skeletal evidence for violence on deposited infants; however, infanticide rarely leaves skeletal damage (cf. Eriksen Citation2017). It is worth noting that Moses (Citation2008) and Carter’s et al.’s (Citation2015) accounts are not mutually exclusive.

3 This was suggested to me by Prof Douglas Baird (pers. comm. at PhD viva, 06.2020).

REFERENCES

- Adams, R.L., and King, S.M., 2010. Residential burial in global perspective. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 20 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1551-8248.2011.01024.x

- Alberti, B., 2016. Archaeologies of ontology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 45 (1), 163–179. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095858

- Alberti, B., and Marshall, Y., 2009. Animating archaeology: local theories and conceptually open-ended methodologies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 19 (3), 344–356. doi:10.1017/S0959774309000535

- Alberti, B., and Marshall, Y., 2014. A matter of difference: Karen Barad, ontology and archaeological bodies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 24 (1), 19–36. doi:10.1017/S0959774314000067

- Anderson, B., and Harrison, P., eds., 2010. Taking-place: non-representational theories and geography. London: Routledge.

- Arponen, V.P.J., and Ribeiro, A., 2014. Understanding rituals: a critique of representationalism. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 47 (2), 161–179. doi:10.1080/00293652.2014.938107

- Bailey, D., and McFadyen, L., 2010. Built objects. In: D. Hicks and M.C. Beaudry, eds. The oxford handbook of material culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 562–587.

- Baird, D., Fairbairn, A., and Martin, L., 2017. The animate house, the institutionalization of the household in Neolithic central Anatolia. World Archaeology, 49 (5), 753–776. doi:10.1080/00438243.2016.1215259

- Barad, K., 2007. Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barański, M.Z., et al., 2015. The architecture of Neolithic Çatalhöyük as a process. In: I. Hodder and A. Marciniak, eds. Assembling Çatalhöyük. Leeds: European Association of Archaeologists, 111–126.

- Barański, M.Z., et al., 2022. Continuity and change in architectural traditions at late Neolithic Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder and C. Tsoraki, eds. Communities at work: the making of Çatalhöyük. London: British Institute at Ankara, 177–198.

- Boivin, N., 2000. Life rhythms and floor sequences: excavating time in rural Rajasthan and Neolithic Catalhoyuk. World Archaeology, 31 (3), 367–388. doi:10.1080/00438240009696927

- Borić, D., 2013. Theater of predation: beneath the skin of Göbekli Tepe images. In: C. Watts, ed. Relational archaeologies: humans, animals, things. London: Routledge, 42–64.

- Brereton, G., 2013. Cultures of infancy and capital accumulation in pre-urban mesopotamia. World Archaeology, 45 (2), 232–251. doi:10.1080/00438243.2013.799042

- Carter, T., et al., 2015. Laying the Foundations: creating households at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder and A. Marciniak, eds. Assembling Çatalhöyük. Leeds: European Association of Archaeologists, 97–110.

- Cessford, C., 2005. Absolute dating at Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder, ed. Changing materialities at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 65–99.

- Çevik, Ö., 2019. Changing ideologies in community-making through the Neolithic period at Ulucak. In: A. Marciniak, ed. Concluding the Neolithic: the near east in the second half of the seventh millennium BCE. Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 219–240.

- Chyleński, M., et al., 2019. Ancient mitochondrial genomes reveal the absence of maternal kinship in the burials of Çatalhöyük people and their genetic affinities. Genes, 10 (3), 207. doi:10.3390/genes10030207

- Crellin, R.J., 2020. Change and Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Crellin, R.J., et al., 2021. Archaeological theory in dialogue: situating relationality, ontology, posthumanism, and indigenous paradigms. London: Routledge.

- DeLanda, M., 2006. A new philosophy of society: assemblage theory and social complexity. London: Bloomsbury.

- Doel, M.A., 2010. Representation and difference. In: B. Anderson and P. Harrison, eds. Taking-Place: non-Representational theories and geography. London: Routledge, 117–130.

- Doherty, C., 2020. The clay world of Çatalhöyük: a fine-grained perspective. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Düring, B.S., 2006. Constructing communities : clustered neighbourhood settlements of the Central Anatolian Neolithic ca. 8500-5500 Cal. BC. Thesis (PhD). Leiden: Leiden University.

- Eriksen, M.H., 2017. Don’t all mothers love their children? Deposited infants as animate objects in the Scandinavian iron age. World Archaeology, 49 (3), 338–356. doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1340189

- Eriksen, M.H., 2020. ‘Body-objects’ and personhood in the Iron and Viking Ages: processing, curating, and depositing skulls in domestic space. World Archaeology, 52 (1), 103–119. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1741439

- Eriksen, M.H., and Kay, K., 2022. Reflections on posthuman ethics. Grievability and the more-than-human worlds of Iron and Viking Age Scandinavia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 32 (2), 331–343. doi:10.1017/S0959774321000561

- Esin, U., et al., 1991. Salvage excavations at the pre-pottery site of Aşıklı Höyük in Central Anatolia. Anatolica, XVII, 123–174.

- Fagan, A., 2017. Hungry architecture: spaces of consumption and predation at Göbekli Tepe. World Archaeology, 49 (3), 318–337. doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1332528

- Farid, S., 2005a. Level VII: space 113, space 112, space 105, space 109, building 40, space 106, spaces 168 & 169, buildings 8 & 20, building 24 and relative heights of level VII. In: I. Hodder, ed. Excavating Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-1999 seasons. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 283–338.

- Farid, S., 2005b. Level VIII: space 161, space 162, building 4, space 115, buildings 21 & 7, building 6 and relative heights of level VIII. In: I. Hodder, ed. Excavating Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-1999 seasons. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 227–282.

- Fowler, C., 2013. The emergent past: a relational realist archaeology of early bronze age mortuary practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- French, D., et al., 1972. Excavations at Can Hasan III, 1969-1970. In: E.S. Higgs, eds. Papers in economic prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 181–190.

- Gardner, A., and Wallace, L., 2020. Making space for past futures: rural landscape temporalities in Roman Britain. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 30 (2), 327–342. doi:10.1017/S0959774319000647

- Guerrero, E., et al., 2009. Seated memory: new insights into near Eastern Neolithic mortuary variability from tell halula, Syria. Current Anthropology, 50 (3), 379–391. doi:10.1086/598211

- Haddow, S.D., et al., 2021. Funerary practices I: body treatment and deposition. In: I. Hodder, eds. Peopling the Landscape of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2009-2017 seasons. London: British Institute at Ankara, 281–314.

- Haddow, S.D., and Knüsel, C.J., 2017. Skull retrieval and secondary burial practices in the Neolithic Near East: recent insights from Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Bioarchaeology International, 1 (1–2), 52–71. doi:10.5744/bi.2017.1002

- Harman, G., 2018. Object-oriented ontology: a new theory of everything. London: Pelican.

- Harris, O.J.T., 2018. More than representation: multiscalar assemblages and the Deleuzian challenge to archaeology. History of the Human Sciences, 31 (3), 83–104. doi:10.1177/0952695117752016

- Harris, O.J.T., and Robb, J., 2012. Multiple ontologies and the problem of the body in history. American Anthropologist, 114 (4), 668–679. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1433.2012.01513.x

- Hendon, J.A., 2010. Houses in a landscape: memory and everyday life in Mesoamerica. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hodder, I., 2012. Entangled: an archaeology of the relationships between humans and things. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hodder, I., 2018. Introduction: two forms of history making in the Neolithic of the Middle East. In: I. Hodder, ed. Religion, history and place in the origin of settled life. Louisville: University Press of Colorado, 3–32.

- Hodder, I., and Farid, S., 2013. Questions, history of work and summary of results. In: I. Hodder, ed. Çatalhöyük excavations: the 2000–2008 seasons. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 1–34.

- Hodder, I., and Pels, P., 2010. History houses: a new interpretation of architectural elaboration at Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder, eds. Religion in the emergence of civilization: Çatalhöyük as a case study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 163–186.

- Hofmann, D., 2009. Cemetery and settlement burial in the lower bavarian LBK. In: D. Hofmann and P. Bickle, eds. Creating communities: new advances in central European neolithic research. Oxford: Oxbow, 220–234.

- Horne, L., 1994. Village spaces: settlement and society in Northeastern Iran. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Jones, A.M., Díaz-Guardamino, M., and Crellin, R.J., 2016. From artefact biographies to ‘multiple objects’: a new analysis of the decorated plaques of the Irish sea region. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 49 (2), 113–133. doi:10.1080/00293652.2016.1227359

- Joyce, R.A., 2010. In the beginning: the experience of residential burial in Prehispanic Honduras. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 20 (1), 33–43. doi:10.1111/j.1551-8248.2011.01026.x

- Karamurat, C., Atakuman, Ç., and Erdoğu, B., 2021. Digging pits and making places at Uğurlu during the sixth millennium BC. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 40 (1), 23–42. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12209

- Kay, K., 2020. Dynamic houses and communities at Çatalhöyük: a building biography approach to prehistoric social structure. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 30 (3), 451–468. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000037

- Knüsel, C.J., et al., 2021. Bioarchaeology at Neolithic Çatalhöyük: biological indicators of health, well-being and lifeway in their social context. In: I. Hodder, eds. Peopling the landscape of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2009-2017 Seasons. London: British Institute at Ankara, 281–314.

- Kuijt, I., 2008. The regeneration of life: neolithic structures of symbolic remembering and forgetting. Current Anthropology, 49 (2), 171–197. doi:10.1086/526097

- Laneri, N., 2010. A family affair: the use of intramural funerary chambers in Mesopotamia during the late third and early second millennia B.C.E. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 20 (1), 121–135. doi:10.1111/j.1551-8248.2011.01031.x

- Law, J., and Mol, A., 2008. Globalisation in practice: on the politics of boiling pigswill. Geoforum, 39 (1), 133–143. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.08.010

- Love, S., 2013. The performance of building and technological choice made visible in Mudbrick architecture. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 23 (2), 263–282. doi:10.1017/S0959774313000292

- Lucas, G., 2012. Understanding the archaeological record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lucas, G., 2013. Afterword: archaeology and the science of new objects. In: B. Alberti, A.M. Jones, and J. Pollard, eds. Archaeology after interpretation. returning materials to archaeological theory. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 369–380.

- Lucas, G., and Witmore, C., 2021. Paradigm lost: what is a commitment to theory in contemporary archaeology? Norwegian Archaeological Review, 55 (1), 64–77. doi:10.1080/00293652.2021.1986127

- Marciniak, A., et al., 2015. The nature of the household in the upper levels at Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder and A. Marciniak, eds. Assembling Çatalhöyük. Leeds: European Association of Archaeologists, 151–166.

- Matthews, W., 2005. Micromorphological and microstratigraphic traces of uses and concepts of space. In: I. Hodder, ed. Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995–1999 Seasons. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 355–398.

- McAnany, P.A., 2010. Practices of place-making, Ancestralizing, and re-animation within memory communities. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 20 (1), 136–142. doi:10.1111/j.1551-8248.2011.01032.x

- Mellaart, J., 1963. Excavations at çatal Hüyük, 1962: Second Preliminary Report. Anatolian Studies, 13, 43–103. doi:10.2307/3642490

- Meskell, L., 2008. The nature of the beast: curating animals and ancestors at Çatalhöyük. World Archaeology, 40 (3), 373–389. doi:10.1080/00438240802261416

- Mol, A., 1999. Ontological politics. A word and some questions. The Sociological Review, 47 (1_suppl), 74–89. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03483.x

- Mol, A., 2002. The Body multiple: ontology in MEDICAL PRACTICE. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mol, A., 2015. Who knows what a woman is … On the differences and the relations between the sciences. Medicine Anthropology Theory, 2 (1), 57–75. doi:10.17157/mat.2.1.215

- Moore, A., 2009. Hearth and home: the burial of infants within romano-British domestic contexts. Childhood in the Past, 2 (1), 33–54. doi:10.1179/cip.2009.2.1.33

- Moses, S.K., 2008. Çatalhöyük’s foundation burials: ritual child sacrifice or convenient deaths? In: K. Bacvarov, ed. Babies reborn: infant/child burials in pre- and protohistory. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 45–52.

- Özbaşaran, M., Duru, G., and Stiner, M.C., eds., 2018. The early settlement at Aşıklı Höyük: essays in honor of Ufuk Esin. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları.

- Pearson, J., et al., 2013. Food and social complexity at Çayönü Tepesi, southeastern Anatolia: stable isotope evidence of differentiation in diet according to burial practice and sex in the early Neolithic. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 32 (2), 180–189. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2013.01.002

- Pilloud, M.A., et al., 2016. A bioarchaeological and forensic re-assessment of vulture defleshing and mortuary practices at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 10, 735–743.

- Pilloud, M.A., and Larsen, C.S., 2011. “Official” and “practical” kin: inferring social and community structure from dental phenotype at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 145 (4), 519–530. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21520

- Plug, J.-H., Hodder, I., and Akkermans, P.M.M.G., 2021. Breaking continuity? Site formation and temporal depth at Çatalhöyük and Tell Sabi Abyad. Anatolian Studies, 17, 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0066154621000028

- St. George, I., 2012. Çatalhöyük murals: a snapshot of conservation and experimental research. In: R. Tringham and M. Stevanović, eds. Last house on the hill: BACH area reports from Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 473–480.

- Sullivan, L.P., and Rodning, C.B., 2010. Residential burial, gender roles, and political development in late prehistoric and early Cherokee cultures of the southern appalachians. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 20 (1), 79–97. doi:10.1111/j.1551-8248.2011.01029.x

- Tibbetts, B., 2017. Perinatal death and cultural buffering in a Neolithic community at Çatalhöyük. In: E. Murphy and M.L. Roy, eds. Children, death and burial: archaeological discourses. London: Oxbow, 35–42.

- Tripković, J., 2017. Building 131. In: S.D. Haddow, ed. Çatalhöyük archive report 2017. Stanford: Çatalhöyük Research Project, 36–47.

- Tung, B., 2013. Building with Mud: an analysis of architectural materials at Çatalhöyük. In: I. Hodder, ed. Substantive technologies at Çatalhöyük REPORTS from the 2000–2008 seasons. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 67–80.

- Yaka, R., 2020. Archaeogenomic Analysis of Population Genetic Relationships and Kinship Patterns in the Sedentary Societies From Neolithic Anatolia. Thesis (PhD). Ankara: Middle East Technical University.

- Yeomans, L., 2013. Building 66. In: I. Hodder, ed. Çatalhöyük excavations: the 2000–2008 seasons. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 481–484.

- Yıldırım, B., Hackley, L.D., and Steadman, S.R., 2018. Sanctifying the house: child burial in prehistoric anatolia. Near Eastern Archaeology, 81 (3), 164–173. doi:10.5615/neareastarch.81.3.0164