ABSTRACT

Between 1902 and 1913 two acclaimed educational reformers wrote several series of children’s primers in the Netherlands. Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra collaborated closely with the painter Cornelis Jetses who provided the illustrations. The series would become classics in both text and image. In this article the symbolic educational function of the places depicted on the illustrations are analysed. It shows how concrete locales inside the house, outside on the streets and in nature symbolise progressive educational ideas using existing models and metaphors of family life, schooling, and freedom and constraint.

Introduction

Between 1902 and 1913 a Dutch trio produced a sequence of primers that would become the core of Dutch reading instruction for decades. Hindericus Scheepstra (1859–1913) possessed the might of the pen, Jan Ligthart (1859–1916) owned the force of the idea, and Cornelis Jetses (1873–1955) held the power of the image. Ligthart was the standard bearer of the series. His progressive school in the poor quarters of The Hague was visited by Ellen Key,Footnote1 for he was internationally known for his optimistic view on the nature of the child, his plea for an intuitive, kind, full-hearted approach of the child, his interest in socially less privileged children, and his rejection of a methodical, cognitive approach of education. As was the case with other educators who are associated with umbrella terms like new education, progressive education, éducation nouvelle, and Reformpädagogik, his progressive ideas were rooted in historical continuity from Comenius, Locke, Rousseau, Pestalozzi, and Froebel to Ellen Key,Footnote2 all starting from the concept of “natural education”, for the “natural child”.Footnote3 Lighthart however was not connected to any radical emancipation programme or with the “new” science of psychology as some other educational reformers were.Footnote4 Like many progressive German elementary school teachers, he was of the opinion that children needed appropriate guidance to develop their potential.Footnote5

Dutch progressive pedagogy was rooted in Romanticism and the Kulturkritik of the fin de siècle, with its fear of disruption of intimate social structures like the family, because of modernisation. Also, Lighthart aimed for a better world and better people by educating children in the right way, with room for intuition and creativity based on personal bounds, with moral values as taking responsibility and with an interest in the full child which needed to be confronted with full life.Footnote6 Like for example Verheyen in Flanders,Footnote7 he tried to implement his ideas in which he wanted to overcome the deficiencies of the stiff, disciplined, and knowledge-centred “Old School”, within the existing grammar of schooling. He did so not working from doctrines, not even within the “Vom Kinde aus” doctrine, which was widely embraced among educational reformers, but pragmatically, placing “pedagogical tact” at the core of proper education.Footnote8

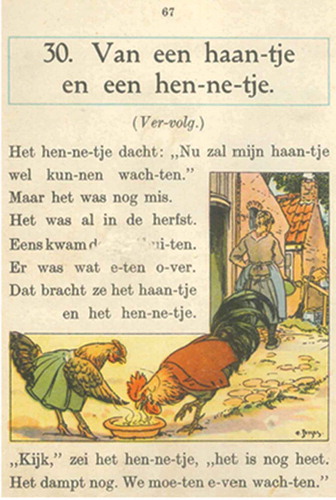

The series of primers produced by Ligthart, Scheepstra, and Jetses became widely used in Dutch elementary schools and contributed to the spread of progressive educational ideals in mass education.Footnote9 Next to the series for first reading, they published an integrated method for (social) sciences (Het volle leven), including a series of wall charts and another series of schoolbooks that would become children’s classics. This article is about the first reading books. Although written as primers, splitting polysyllabic words to ease the reading for children, the series are considered and discussed as children’s literature representing the genre of family stories.Footnote10 They represent a romantic version of Dutch progressive education in text, ideology, and illustration, by presenting young children and their families, living harmoniously together in a rural environment with an abundance of places to play.

The collaboration started with Hindericus Scheepstra and Jan Ligthart. Publisher Wolters had asked them to make a series of anthologies for the purpose of reading lessons. They decided they rather wrote the books themselves, following the so called “belletrist” tradition of Scheepstra’s former instructor Lubbertus Leopold.Footnote11 Leopold had designed a series of readers that graduated in difficulty, broadened the conceptual universe of the child with each volume and, most importantly, aimed at an aesthetic and pleasurable reading experience instead of solely focusing on transmitting useful information. Scheepstra and Ligthart decided to adopt this procedure, with the exception of the writing style. Whereas Leopold’s style was characterised by a sentimental and highfalutin tone, Scheepstra and Ligthart opted for the everyday language of young children. Moreover, they decided not only to reflect this child-centred approach in the language used, but also in the content. The series follow the gradually expanding world of children from being very dependent on their parents and staying close to home to gradually enhancing the distance between their parents and home by literally going further and further away from home.

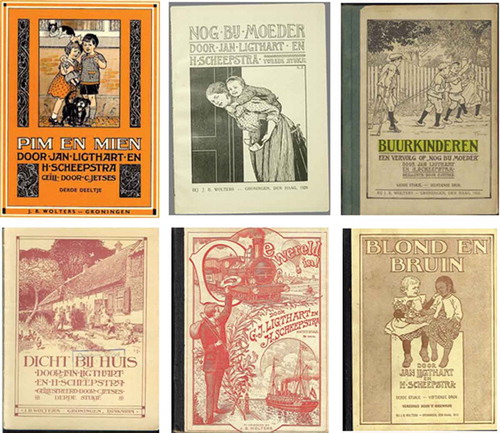

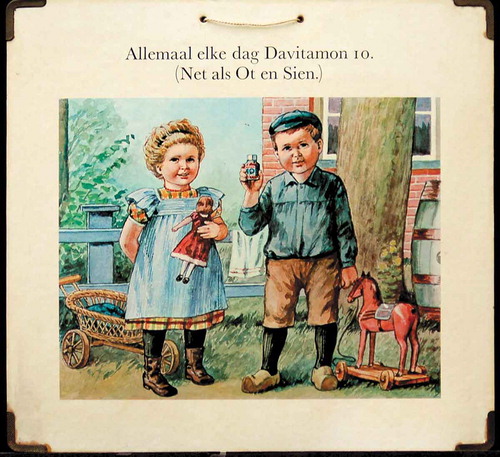

The first series, De wereld in! (Into the world! 1898–1902, eight volumes) was partly written by Scheepstra, partly by Ligthart, and illustrated by W.K. de Bruin. Much more successful were the series that followed, when both men took up what suited them best; Scheepstra the writing for children and Ligthart the educational ideas behind the stories.Footnote12 Moreover, Cornelis Jetses was asked to make the illustrations. The series Dicht bij huis (Close to home, 1902–1903, four volumes), Blond en Bruin (Blond and brown, 1902, four volumes), Nog bij moeder (Still with mother, 1904–1905, four volumes), Pim en Mien (Pim and Mien, 1907–1908, four volumes) and Buurkinderen (Neighbour children, 1911–1913, four volumes) have been used for reading education until the 1970s and Jetses’ illustrations have been used for advertisements of all kinds and are to be found on merchandise throughout the whole twentieth century (see ).

Figure 1. Advertisement to take Davitamon vitamins every day, “Just like Ot and Sien” (collection Dutch national museum of education, Dordrecht)

The series were presented as two reading cycles. The first cycle for the youngest readers is centred around Nog bij moeder, with Pim en Mien as precursor and Buurkinderen as sequel. The second cycle was for more advanced readers and centred around De wereld in, with Dicht bij huis as precursor and Blond en Bruin as “parallel series” (see ).

Much is written about the influence of the books on Dutch education, the child-focused style of writing, and the attractive illustrations that present an idyllic version of Dutch country life.Footnote13 However, the relationship between the depicted settings and their educational functions has never been analysed. That is the focus of this article.

Although the series were explicitly aimed at children, implicitly they also addressed adults. By means of the stories, the authors transmitted the same educational ideas they disseminated through essays and teacher manuals to educators. They thus paved the way for integrating these ideas in the minds of educators and expanding their educational literacy.Footnote14 These ideas were progressive in their focus on the world and experiences of children, though the chosen settings of the stories also show a more conservative approach to certain elements, such as the emphasis on the importance of family life with a mother staying home to take care of the children and her breadwinning husband.Footnote15 In the series, these ideas are expressed in the stories, but also in the illustrations. Focusing on the settings that are depicted in these illustrations, we decided to use Peter Hunt’s notions of “outer place” and “inner space” to explore the relationship between the concrete locales in which the stories take place and the symbolic function of these locales. “Outer place” refers to the specific locations in which the stories are set, such as the family living room, the garden, the street, and the school. “Inner space” concerns the educational ideas these places represent. Although concrete locales in books for children seem realistic, they are more fictive than the symbolic meaning they represent, Hunt claims: ‘the internal spaces tend to explore the relationship between children, and between adults and children … the inner, abstract spaces may seem to be essentially fictive, whereas they often address those psychological areas of conflict, tension, and resolution which provide the unique driving-force of serious children’s literature, and are, in that sense, quintessentially ‘real’.’Footnote16

To shed light on the relationship between the depicted locales (i.e. the outer places) and the educational ideas behind them (i.e. the inner space), the illustrations by Jetses in the series for the youngest readers (Pim en Mien, Nog bij moeder, Buurkinderen) will be compared to the educational ideas and ideals Scheepstra and Ligthart explicated in their books and articles. Scheepstra and Ligthart developed their ideas in close friendship. They corresponded intensively and visited each other regularly to talk about the series.Footnote17 Jetses for his part was involved through several meetings. He enthusiastically endorsed Scheepstra’s and Ligthart’s ideas and described their collaboration as a good “interaction”.Footnote18 Whereas Scheepstra was more a practical thinker on education, expressing his ideas in a much-used teachers’ manual, Ligthart’s writings were more philosophical, literary, and sometimes even a bit free-floating. He explicitly connected his educational ideas to specific locations in the essays he wrote on education, which made it possible to compare the essays and the series even better. Using familiar outer places, such as the family living room, free nature, the street, the school, and the story as symbols for inner spaces, he incorporated existing educational models in his pragmatic interpretation of progressive education.

To analyse the visual rhetoric of Jetses’ illustrations, we use Nikolajeva and Scott’s elaboration of the iconotext theory. Iconotext theory explains the relationship of the visual and the verbal text.Footnote19 Applied to illustrated children’s books and picture narratives, Nikolajeva and Scott identify symmetrical and complementary interactions between image and text. In a symmetrical interaction, words and pictures tell the same story. They make each other redundant; if the pictures would be taken away, the story would not change. In a complementary interaction, the pictures may enhance, counterpoint, or contradict the story. In an enhancing interaction, illustrations add to the meaning of the story. In a counterpoint dynamic, the illustrations show something different than the story tells, in such a way that the meaning of the words is expanded. When illustrations convey another meaning than the words do, the dynamic is called contradictory. Ligthart’s, Scheepstra’s, and Jetses’ series have often been classified as “illustrated books”, books in which the pictures are subordinated to the words and the text is not dependent on the illustrations to convey its essential message.Footnote20 In this article we will show how the producers themselves thought otherwise and a close reading of the illustrations also shows otherwise.

Innocent ignorance

Illustrated books date back to the invention of printing in the late Middle Ages. In Western Europe, illustrations in books for children got an impulse in the seventeenth century, first with Comenius’ Orbis Sensualium Pictus (1658), followed by the claim of John Locke that pictures were a necessity to learn to read in Some thoughts concerning education (1693). Subsequently, many illustrated alphabet books and prints were published in Western Europe. The pictures used for those books and prints were mass-produced and often re-used. Around 1900 progressive educationalists started to aim at a more aesthetic approach; books for children had to be more than mass production, hackwork, and learning material: it had to be art. Children’s books were assigned a role in the elevation of the people.Footnote21

With regard to illustrations, two approaches took shape in this period in the Netherlands: a moral approach and an artistic one. Adherents of the first approach considered texts for children a tool to moral education of both the individual child and the world. For them, illustrations were close to a danger. Illustrated books would discharge children to use their own imagination; illustrations were “bait for superficial buyers”.Footnote22 Adherents of the artistic approach considered the moral of a story subordinate to aesthetics. They considered illustrations very important, not so much to teach children an understanding of art, but to help them develop their own artistic creativity.Footnote23 They wanted children to be able to enjoy illustrations for their beauty and sought for real artists to provide for them. It was in this context that Cornelis Jetses was asked to make the illustrations for Scheepstra and Ligthart’s primers.Footnote24 “Beautiful illustrations [are] an important means to develop the aesthetic sense of children”, Scheepstra wrote in his teachers’ manual in 1901.Footnote25 However, the emphasis on aesthetic development did not mean an exclusion of ethical development of the readers. On the contrary, the aesthetic development was meant to enhance the ethical effect of the stories.Footnote26

Cornelis Jetses was indeed educated as an artist. He was born in a poor family in the north of the Netherlands. At 12 years old, he got a scholarship to study at art academies in the Netherlands and Germany and became a painter of historical pieces. After illustrating a catalogue of furniture for publisher J.B. Wolters, who also published Scheepstra and Ligthart’s work, Jetses was asked to illustrate their books for young readers.Footnote27

Scheepstra and Ligthart wanted their books to represent the world of children. They wanted it to be a world that children knew.Footnote28 “From the beginning onwards”, Scheepstra wrote in his teachers’ manual, “the child has to learn to read naturally; it has to read ‘as if it speaks.’ The reading matter can help, by being about simple things, derived from children’s experiences, but above all by the form of the words.”Footnote29 Thus, children themselves were in the centre of the stories, the language was their language, the adventures could have been the readers’; identification of the child-reader with the child-protagonists was the key.Footnote30 To be able to do this, a writer had to identify with children, Scheepstra wrote. He considered many primers dry, trivial, meaningless, unpleasantly sweet, and thereby infantile: “When writing for children, one should first imagine oneself fully into their thoughts, look at the world with child’s eyes.”Footnote31

The primers were meant for a wide audience of children, irrespective of their religious denominations and social class. Therefore, in the stories the yearly seasons were followed, but specific celebrations, such as Saint Nicholas and Christmas, were left out. The authors were also sensible of the issue of social inequality, with both Ligthart and Jetses coming from humble social backgrounds themselves. Furthermore, Ligthart was headmaster of a progressive elementary school for the poor for more than 30 years (1885–1916). The settings of the books were diverse: bourgeois in Pim en Mien, rural in Nog bij moeder and Buurkinderen, showing working or peasant class families.

The idea was that the characters would become friends to young readers. So much so that, after a few reading lessons, young readers would want to read on by themselves, to find out how those friends continued to fare. Thus, Scheepstra and Ligthart adopted the model of the book series, with a connected storyline to hold onto their readers and a threefold purpose blended in an old recipe: practise reading skills and transmit pedagogical lessons through offering entertainment. They called their concept “run-through-books” (door-ren-boekjes): books “that will delay neither in content, nor in language … Books, [children] can run through one after the other”.Footnote32

To offer young readers a world they could relate to, Scheepstra and Ligthart geared the stories to young children’s environment. The protagonists, always slightly younger than the intended readers to ensure the child would recognise their adventures,Footnote33 had small adventures close to home. Domestic elements define their experiences, such as the house cat, a fall, the water butt, a duck, or the rain. Adults stay in the background, only to speak up when the children need educational steering. The focus is on children’s perception of the world. The style of the stories is realistic.

“Realistic”, however, must not be understood literally, but in the same literary sense as Hunt characterised the “real” outer places more fictive than the symbolic inner spaces.Footnote34 Social issues are absent. The world is represented as simple and kind. The adults are loving and consistent educators, always present when they need to be, and never at a loss about how to handle a situation or a child. Likewise, all children are good, honest, and well behaved. If they slip, it is an unintended slip and only due to innocent ignorance. Using Jenks’s clear and twofold typology of discourses of the child in his sociological exploration of childhood, one could say that in the books an image of children and childhood was sketched that follows from the Apollonian image of the child. An image in which children represent sweetness, moral purity, innocence, and light: “Children in this image are not curbed nor beaten into submission; they are encouraged, enabled and facilitated.”Footnote35

Jetses’ illustrations were realistic in the same literary sense as the stories, masking the inner space with seemingly realistic outer places.Footnote36 He situated the world of Scheepstra and Ligthart’s paper children in an idyllic, mostly rural environment. He was inspired by good memories of his own childhood, extended stays with families in the countryside of the Northern Netherlands, and a romantic image of children and childhood. In his pictures, he left out the actual harshness of living in the countryside around the fin the siècle.Footnote37

At first sight, the relationship between text and image seems to be symmetrical; words and pictures tell the same story, they repeat the information in different forms of communication.Footnote38 Scheepstra and Ligthart, however, considered the pictures more than mere illustrations that show what is expressed in the text. In their preface to the series Dicht bij huis, they emphasised how for them the illustrations were essential additions to the text: “The illustrations are part of the book, and should be read as much as the text. You should pay close attention to them with your pupils – to the vignettes as well, and you will soon find out, how stimulating and instructive such a careful consideration is.”Footnote39

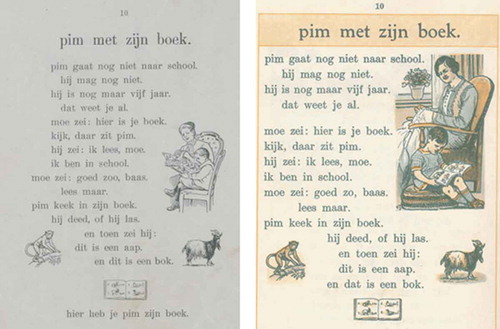

Consequently, Scheepstra and Ligthart claimed an enhancing interaction,Footnote40 in which the pictures expand the information given by the words alone, to be discovered through careful “reading” of the images. The importance of the illustrations was accentuated in reprints and later editions for which Jetses was asked to revise his illustrations, so that the illustrations could continuously be tested against “the full life of this time”.Footnote41 Of some illustrations there are even two revisions, with the second one modernised in terms of clothes, hair style, buildings, and machines (see ).Footnote42

Monsters of mischief

While the paper children happily frolic through the stories, in which a day of rain, a cold or a scraped knee represent the biggest educational challenges, Ligthart did show he was well aware of the other side of education in his essays for adults. He recounted, for example, “a difficult moment” in which his proudly displayed method, of approaching all children with kindness and love to emphasise their uniqueness and generate moral behaviour, dramatically failed.Footnote43 After he invited a group of young boys into his school, they wildly entered, tumbling over one another with “reckless, loud uncontrolledness”. They “ran around like madmen, screaming, jumping, not paying attention to any order … shouting like Indians”. And they did not come once, but each day after school they squeezed themselves through the school gate, these “little monsters of mischief”. There he stood, the self-proclaimed “pedagogue of the heart”, unable to control a group of eight-year-olds. His account of this side of childhood and education coincides with Jenks’s Dionysian discourse, in which children are seen as chaotic, amoral, and unruly: “The child is Dionysian in as much as it loves pleasure, it celebrates self-gratification and it is wholly demanding in relation to any object, or indeed subject, that prevents its satiation.”Footnote44

Thus, we see how Scheepstra and Ligthart in their booklets for children presented their young readers with a conveniently arranged small world in which any problem, social, economic, or educational, seems miles away. However, simultaneously, Ligthart showed adults, mainly parents and educators who were the audience of his essays, that he was well aware of this space that constituted the distance between reality and ideal. His answer to bridge this distance was a specific educational approach. Hence, the space between Dionysian challenges and the Apollonian ideal was space in which there was room for education: educational space.

In the essay about his Dionysian adventure, Ligthart linked unruliness and uncontrolledness to the streets, while everything inside the school gate represented order. Within the school gates, the children neatly walked in line, but after arriving on the streets it was difficult to maintain the line, for the “young Cossacks” quickly invaded and darted off again, too quick to run after. Again, the street boys Ligthart invited into the school, represent unruliness, this time infecting the school children, as well. Bursting through the fence, the little rascals brought uncontrolledness inside the gates. The partition between the Dionysian and the Apollonian world was trespassed, the pedagogue of the heart remained defenceless:

What to do?Now this was the difficult moment. My hands were aching to grab a couple of the most cheeky monkeys in the neck and hurl them back onto the street. That would have scared them immediately. All of them would have ran away. But first, I would not be able to defend myself against litigant parents in case this hurling method would end badly. They would reproach me, and not without reason: ‘Why then, did you let them enter in the first place? You should not have started this.’ Second, and more importantly, I would not achieve my goal: the boys would start fearing me, hate me, become my enemies instead of my friends.Footnote45

Ligthart decided to use his domain, inside the school gate, the place of order, to break the boys’ anarchy. He did so by approaching them as the wild children they were and taking them even deeper inside the school gate. He took them into the school and he won them over with his pedagogical tact; instead of punishing them, he reached out to them. In awe of all the educational prints and tools, the little rascals fell silent. Some of them even took off their hats. Ligthart had tamed them.Footnote46

Ligthart represented chaos and order by using the street and the school to symbolise these extremes. He bridged the distance between chaos and order with education, starting from pedagogical tact and love for all children, including the wild ones. This sheds light on the symbolic role of the specifically chosen outer places in his work. In what follows, we will show how he links more outer places to specific educational ideas and ideals in his essays for adults and his and Scheepstra’s stories for children. Whereas the street and the school symbolise chaos and order, the family home, the city, the garden, and free nature represent his ideas on the role of the mother, the importance of guided freedom, and the tension between imagination and fantasy. Three kinds of outer places were found in Ligthart’s and Scheepstra’s work: places inside, places outside, and fantasy worlds.

Places inside

Mother in the middle: the family living room

The educational reformers, who were opposed to the one-way communication in the instructive school environment, emphasised the potential of the family as an educational environment in which there was more space for the individual child.Footnote47 Ligthart connected the family living room explicitly with moral education, especially by the mother. The family living room in both his essays and his primers is the domain of the mother. Here we see how Ligthart adopted the rhetoric of progressive education in his child-centred approach, but stuck to the dominant model of bourgeois family life at the same time.Footnote48 It is within the four walls of the family living room that the mother educates her children, not by explicit instruction or interference, but simply by her presence:

A mother in the living room in a circle of variously aged children is a complete country government: a united legislative and executive branch. And she is so much more. In fact, there is only one image I can think of which represents her significance properly: she is the sun of this little world. She does not have to interfere with the children continuously. The sun just stands and shines. Thus, while mother remains at her seat, her presence brings light and warmth in the family living room-atmosphere. That will make the children grow intellectually, and especially morally.Footnote49

Several of Jetses’ illustrations in the primers depict such a scene of motherly presence, often without or with little interference. For example, in the chapter “Pim met zijn boek” (Pim with his book) in the first volume of Pim en Mien, we see the little boy Pim reading a book with his mother next to him working on an embroidery.Footnote50 They are turned towards each other, obviously both enjoying each other’s company; however, on the revised illustrations in later editions, Pim is completely absorbed by his book, not aware of his mother close by him. She on her part is absorbed by her child, leaving her embroidery, looking at him with quiet appreciation ().Footnote51 This depiction of the scene refers to Ligthart’s characterisation of a true mother: “a woman does not become a mother by bearing children, only by giving herself completely to those children.”Footnote52 In Nog bij moeder, fourth volume, we encounter a similar scene: the children Ot and Trui are in the living room doing their own things – Trui is knitting for school, Ot plays with the cat – while mother is quietly present. Only when Ot asks her a question does she interfere.Footnote53 In the revisions, Jetses added prominently present indoor plants on both pictures, symbolising the concept of indoor growing.Footnote54

On the illustrations in Nog bij moeder and Buurkinderen, both set in working-class and farming families, the family living room and kitchen are one and the same place, representing the small housing of working-class families or the warm place within a bigger farm. Corresponding to Ligthart’s characterisation of a true mother, if the women are not absorbed by their children, they are occupied with care assignments, especially cooking and cleaning.Footnote55 Ligthart scorned mothers who put out the care of their children to others. “Many a child has been made a foundling in its own home”, he wrote.Footnote56 When it comes to the family living room, the presence of the father is not mentioned in Ligthart’s essays. He linked the father to outside places, especially to breaking away from the city into free nature. In Jetses’ first versions of the illustrations, following the stories, the father indeed is not present much in the family living room. However, when he is there, he is actively concerned with the children.Footnote57 In the revisions, Jetses added some illustrations in which the father is present, but his role within the domain of the family living room and kitchen mostly ends with this presence. On many illustrations, he reads the paper. He is not unconcerned with the children, though, looking at them with a smile or holding one of them on his lap.Footnote58 Thus, we see also how the facial expression given to the parents by Jetses in his illustrations corresponds to the educational function of the place: growing by caring presence, both of the mother and the father, in the family living room.

When it comes to intellectual growing, in his essays Ligthart contrasted the family living room to the school. Whereas learning in school is represented by force and control, in the family living room a child is learning by playing:

In school, we have to teach it certain subject matter and certain skills, we have to guide or force it. That is not the case of its play in the family living room, is it? Laws or social demands don’t have anything to say in there. One is able to take the child’s interest into account. And this interest is best accounted for when the child is allowed to live in its own world, to its own pleasures, its own fantasies. It will be absorbed with all its heart, and that is the best prerequisite to powerfully develop its talents.Footnote59

So, the family living room is also characterised as a learning space; not a learning space in which order and pressure rule, concepts which Ligthart linked to school and schooling, but a learning space in which exploration and trial-and-error lead the learning. In the family living room more child-orientedness is possible than in school, which was in the best interest of the child’s development, according to Ligthart. Mothers have to follow the children’s curiosity and explorations; their interests are leading, because that would arouse “full pleasure” in their activities, and full pleasure would enable full learning. Again, mothers were encouraged to interfere as little as possible and only give a hand when a child gets stuck.

As mentioned before, the series succeeded one another in reading difficulty but also in the representation of the children’s world. In each new series, the characters are older, and in each new series the characters go further from home. The distance between the family living room, domain of motherly care, and the child grows, and the representation of this place, both in text and in illustration, decreases with each series. The little adventures of Pim and Mien are most often in the family living room, with mother nearby. Ot and Sien can be found much more often in the garden, although signs of parental constraint are always present. The children in Buurkinderen find their activities mostly outside the family home. Moreover, they already go to school.

Discipline, dust, and dullness. School

As shown in the introductory part of this article, for Ligthart, school as a concrete place symbolised discipline, control, and, especially, order. In the case of the street children, this was a near-to-Apollonian ideal to be achieved through the right pedagogical approach. In his essay on taming the street children, he portrayed his own progressive school. At the same time, in many of his essays Ligthart was very critical of the way schooling had been done and was still mostly done in his time. He opted for a much more free way of teaching in schools, in which the pupils rather than the subject matters were leading. Ligthart explicitly contrasted school life with “child life”, claiming the former not to fit the nature of a child, to be unchildlike:

Those little people actually lead two lives: one real child life and another learning life of pretence; the first natural, the second artificial; the first grown and managed from within, the second forced and controlled from outside; the first full heartedly, the other with compelled obedience.Footnote60

School represents dust and dullness in Ligthart’s essays, a rhetoric that would be adopted by other pedagogues aiming at school reform.Footnote61 In a long parable, he related of a boy who asks his teacher for a day off to go fishing with his father. The teacher withholds his consent, upon which Ligthart painted a romantic fictitious fishing trip that would have taught the boy much more, and much quicker, than a dusty day at school.Footnote62

In the stories for children, however, school is exclusively represented in a positive way. The young children long for the day they will be allowed to go. They play school in preparation. The older children enjoy going to school. They tell about their learning activities enthusiastically. The teachers are kind, empathic adults with an eye for childlike trials and tribulations, joys and sorrows.Footnote63 Of course, the books were meant for school reading; it would be rather contradictory to sabre school in them. Moreover, we already concluded how Ligthart presented different discourses, or, perhaps one could say, different realities: a realistic one and an ideal, in both his essays and in the books for children. Whereas his own progressive school showed the street children the wonders of knowledge and learning with modern devices, complementary to the fictitious schools in the books, other schools referred to in the essays represent ways of teaching Ligthart was opposed to.

Consequently, the illustrations by Jetses show only his and Scheepstra’s own progressive ideal of a child-oriented way of schooling. Pim and Mien, who are too young to go to school, anticipate school in their daily activities. In one of the first stories, Pim enjoys watching pictures in a book, pretending he is really reading the book: “I am reading, mother, I am in school.” Jetses added an enhancing perspective in the image accompanying the story. The readers not only see Pim with his book, but also see what Pim sees in his book depicted next to the illustration of Pim’s book. Jetses took the readers’ perspective to focalise through Pim’s eyes and enjoy the same animal pictures. This way, being “in school” was presented as something pleasurable. Pim even takes his book with him to bed.Footnote64

Ot and Sien, also still too young to attend school, play school in the garden. It is one of the most famous images by Jetses, still reprinted on Dutch nostalgic merchandise: Ot’s big sister Trui pretends to be the teacher, with Jetses giving her the characteristic teacher’s finger held up in the air to ask for attention. Both Ot and Sien have left their toys and look at Trui attentively; even the cat is paying attention, enhancing the pedagogical message by mirroring the children’s activities ().Footnote65

A couple of stories later, Ot and Sien visit the real school and meet a real teacher. They stand watching Trui through the school gate. When the teacher sees them, she comes to the gate. The real teacher does not raise her finger to the small children. She kindly bends over and invites them in. In the new version, Jetses even added a neat line of children entering the school, representing the school order inside the school gates. Moreover, in both the old and the new versions he drew very happy schoolchildren sitting behind their desks. In the background of the new version, he also added one of the wall charts from the series Het volle leven (Real life), that Ligthart, Scheepstra, and Jetses also produced, which were published between 1905 and 1911, referring to the observational education method Ligthart advocated. This way, he explicitly linked Ligthart’s progressive method to a class of happy children, taught by a kind and child-oriented teacher who even has an eye for future schoolchildren.Footnote66

Striking on the illustrations of the schoolroom is also the light and the suggestion of continuous fresh air streaming through open windows as a contrast to the old way of schooling, which Ligthart described in his essays as dark, dusty, and dull. The windows are almost low enough for the children to look out and see the green trees outside. Again, Jetses seems to have symbolised the concepts of growing and blossoming by drawing plants and flowers in the windowsill.Footnote67

Places outside

Freedom behind a fence

While school is solely connected to great expectations and joy in the stories for children, the image of school as dusty and dull in Ligthart’s essays gets an outside place of contrast representing opposite concepts: free nature, or the countryside.Footnote68 Not only in the essay about the boy asking his teacher for a day off to go fishing with his father, but in many essays, Ligthart sang the praises of leaving school with its imprisoning learning methods and simultaneously leaving the stifling city to refresh oneself in free nature; a refreshing that concerns both body and mind:

And when going to the countryside, oh the countryside, that gorgeous countryside for a city person, you will enjoy double, no centuple. You drink in the green of the meadows, as if you are suddenly moved from the dullness of methods into the freshness of nature with your soul thirsting for silence and beauty. One single day of such joy counts for a year.Footnote69

The countryside was romantically connected to purity, beauty, peace, and harmony. It was linked to the heart instead of the head, teaching more in one day than a schoolteacher could achieve in weeks. Although adults were recommended by Ligthart to refresh themselves in free nature as often as possible, when it comes to children they are always accompanied by an adult in his essays. This points to Ligthart’s ideas on free development within specific boundaries. A child, he wrote, should be able to develop itself in freedom, for constraining its freedom would constrain its development. However, freedom should be understood as freedom within restrictions. Ligthart did not aim at a ceaseless or limitless freedom, as symbolised in his descriptions of free nature. Children’s space should be restricted, both for their own safety, and in the interest of others. Within this restricted freedom, the children would be able to practise their body and mind, their imagination, independence, and conscience.Footnote70

Similarly, in the stories for children, free nature plays a constricted role. The children are too young to go far away from home by themselves, and only occasionally father has a day off to take them on an outing.Footnote71 Comparing the first illustration of this outing, with the revisions of it, there is an interesting difference in the space between the father and the children. In the very first illustration, the children are feeding the duck with father very close by, holding the little bag with bread for them and also holding Ot by the shoulder, so as to prevent him from coming too close to the water. In the first revision, father stands out of reach of the children, just watching them while smoking a cigar in a very relaxed manner, pointing to more autonomy and freedom of movement for the children. In the modernised version (second revision), father holds the bag again, but not the child. In all versions, he has a facial expression of committed joy and love for the children.

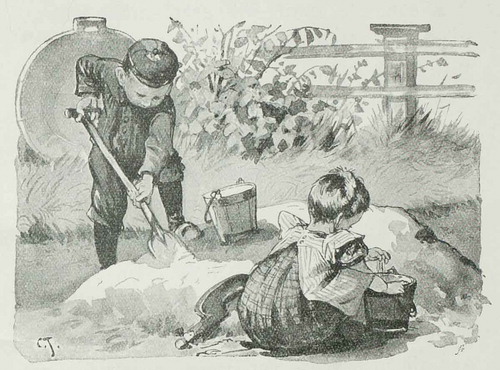

However, the children are also often outside by themselves. In some volumes they are even more often outside without an adult present than inside in the family living room or school. The children are free to wander around the garden and the immediate surroundings of the house, where they play their games using not only toys but also including other elements in their play, such as mother’s dish rack or a water butt.Footnote72 In his illustrations, Jetses found a way to signify that this freedom to play without adult supervision was still a restricted or guided freedom, touching upon Foucault’s notion of “enclosure”, in this case still within the family, in which the parameters of movement are limited:Footnote73 in many illustrations depicting the children outside without an adult watching over them, he included a fence (see ). In particular, many fences can be found in the series about Ot en Sien, Nog bij moeder, which makes sense considering this was the second series in the gradual expansion of the children’s world of experiences.Footnote74

Next to the fence, other elements also refer to an outside place not far from the house, such as the potted plant or the bucket.Footnote75 Often, part of the house is shown instead of a fence,Footnote76 or a wooden palisade.Footnote77 And drying clothes, the house cat, the water butt, and the toys also refer to being in the garden or close to home and not in free nature.Footnote78

A few illustrations in the series do show a young child being outside without references to enclosure, in the form of the home, or the parents nearby. In Nog bij moeder a little girl sits by a pond and sleeps in a meadow.Footnote79 There are no adults around, no fences to be seen: the girl is all alone. However, these illustrations do not accompany the main story, but a story within the main story. When Ot’s older sister Trui comes home, she relates how her teacher told them a story that day and she retells it to Ot and Sien. It is a story about a girl who, indeed, goes out into free nature by herself but loses her way. All the adults panic and a great searching party is set up. In the end, the girl is found by an elderly woman and brought home. Thus, the story shows children the consequences of going too far from home. Adults might read it also as a symbolic representation of the undesirability of total freedom.

Adult proximity

The fence not only symbolises a restricted freedom, it also refers to a more abstract place described in Ligthart’s essays: adult proximity as an educational space within the radius of a parent’s hand, or more literally the educational act of being led by the hand. Adult proximity not only symbolises education in terms of restriction in Ligthart’s essays, being barred, but also education in terms of stimulus: being helped to cross barriers. “When something should be achieved by deliberate education, by adult intervention”, Ligthart wrote, “it is, in my opinion, necessary that those adults feel as one, become as one with the child and lead it this way. By Mother’s hand. And also by Father’s hand.” He evokes the image of a family walk on a Sunday afternoon. At the start, the children are still fresh, but in the end, they slag and drag. “Now, Father takes a warm, little hand in his big one, and look, the child immediately walks more easily … By Father’s hand the child crosses barriers and gets home safely.”Footnote80 Mothers might give their children a hand to persevere in difficult play situations and teachers should do the same in their teaching. In all cases this is done with an eye and open mind for the child’s experience; not raising a hand but offering one. The stories by Scheepstra and Ligthart represent many situations of the helping proximity of adults. They find, mend, and make things, guide children from difficult situation into safe spaces, or offer a virtual hand in the form of advice. The helping hands were warmly depicted by Jetses, for never one of the adults looks reproachful or angry at the children. They always have a smile on their face, or a look of warm concern, often accompanied by tender physical contact. Like Wouter’s teacher, when Wouter suddenly starts to cry in class, because his dog is lost and he is afraid Fox will never come back. The teacher lays an understanding hand on Wouter’s shoulder and helps him to find a solution to search for the dog. And indeed, the same afternoon, Fox is found.Footnote81

Fantasy worlds

Fiction’s facilities and fear for fantasy

In the essays, one finds that Jan Ligthart had an ambivalent relationship with fiction. On the one hand with their series, he and Scheepstra deployed the possibilities of transportation through fiction for reading lessons. Children who would lose themselves in the stories about Pim, Mien, Ot, Sien, and the others would “run through” the booklets, improving their reading skills along the way. Moreover, in Ligthart’s essays, he propagated reading as recreation, a way to relax.Footnote82 He also claimed stories to have moral educational value; they could “show” children the world and its people, their habits and ways, their universal unity.Footnote83 He even tried to incite writers for children to make use of the power of fiction to show children the importance of certain good works, such as missionary work: “Why did we boys know everything about redskins? Because we roamed around the woods with them, on hunt, at war, smoking the pipe of peace … because we shared their lives.” Dutch authors should take the popular writers Aimard and Cooper as examples, Ligthart wrote, for “[n]o one at school or Sunday school would have had to win us over to the Indians. They were our friends, for whom we would have left our mother and father.”Footnote84

Ligthart proclaimed the educational power of stories to incite children’s imagination in service of imagining the past and their future: “bring your pupils to reality, in such a way, that they can see this reality, either close by or far away, both in place and in time, both sensually and mentally.”Footnote85 Fiction could incite the child’s imagination, which in progressive education was considered a key capacity in the learning process, aimed at both individuation and preparing children for modern society.Footnote86 At the same time, Ligthart was critical of fiction: stories should not delude children with untruths. According to him, many writers of fiction tended to overstep the limits when stimulating the child’s imaginative powers with truthful stories and stuffed up their imagination with fantasy. “Oh those poets”, he wrote, “you can never trust them”. In one of his essays he explained how he often sang one of the songs of a famous Dutch children’s writer in those days, Jan Pieter Heije. The song is about taking a nap in a green wood, where one can lay down on lush moss and rest one’s head on a soft cushion of ferns behind a curtain of leaves. He admitted to have often longed for it when he sang the song with the children in his class. However, when he was on holiday near such a wood with plenty of moss, ferns, and leaves, and tried it, he was rudely awakened: first he was attacked by an army of ants, followed by spiders who crept into his neck, to finally being found by buzzing bloodthirsty flies that stung him in all sorts of placesFootnote87. “A poet is a dangerous man”, he concluded. “… he fantasises”. Fantasy is different from imagination, in Ligthart’s view: “And fantasies are even more dangerous than lies. Because of their charm …”Footnote88 Ligthart wanted truth in the stories children could imagine themselves into. He was not against fantasy in stories per se, but fantasy should be presented as fantasy, not as truth. A child would understand that a fairy tale is not literally true, but presenting Saint Nicholas bringing presents and storks delivering babies as real brings untruths in upbringing.

Nevertheless, and despite Ligthart urging Scheepstra in his letters to remove fairy tales from the series, fantasy stories within the stories were presented in every volume.Footnote89 Fables, parables, realistic stories, poems, and fairy tales were presented as places of playing and learning for the protagonists. Jetses also made illustrations with these stories. What is interesting, though, is that in the first versions of the series, Jetses depicted most of the stories within the story in the same style as the main story. However, in the revisions, Jetses included indicators to help readers to identify the difference between truth and untruth, between imagination and fantasy, using what one might call “signifiers of untruthness” in his images depicting the stories within the story.

The “belles-lettres” were included in two ways: integrated in the main story with an explicit framework and as separate chapters reflecting, commenting or mirroring the main story on a meta level. The signifiers of untruthness were included in the new versions.

The fairy tales belong to the category of stories that are integrated in the story with an explicit framework. In Nog bij moeder (1st volume) Trui, Ot’s big sister, retells her brother and friend Sien the fairy tale of the wolf and the seven little goats that she heard from her teacher that morning. Jetses illustrated the story in the same style as the main story. But in the revised illustrations, he added an illustration of Trui telling the story. To signify it is a story within the main story, he alternated the fairy tale’s illustrations with this new image of Trui, and Ot and Sien hanging upon her lips.Footnote90 The other fairy tales, both in Buurkinderen, were illustrated in a style different from the style of the main story, both in the first versions and in the revised one. Whereas Jetses illustrated the main story in a naturalistic style, “Puss in Boots” and “Goldilocks” were drawn in a baroque fashion, reflecting another time and setting and pointing at the fact this is fiction, fantasy, and should not be confused with the true representation of the world in the main story.Footnote91

Another signifier of untruthness is to be found in the parable mother relates to Ot in the tradition of the example story. When Ot cannot wait for his porridge to cool off and burns his mouth, mother tells him about a rooster who is not able to practise his patience, either. First, the rooster eats unripe berries and gets a bellyache. On a warm day, he drinks too fast and again gets a bellyache. Then, he eats something that is still too hot and gets a bellyache for the third time. Finally, the rooster cannot wait until the ice is strong enough to cross it, falls through, and dies. In the first version of the series, the rooster and his hen, who tries to warn him all the time, were drawn in the same naturalistic style as the images accompanying the main story.Footnote92 However, in the revisions, contrary to the animals the protagonists encounter in real life, the rooster and his hen wear clothes ().Footnote93

Figure 12. Signifiers of untruthness: the rooster and his hen. Source: Collection Scheepstra cabinet, Roden

Figure 13. Signifiers of untruthness: the rooster and his hen. Source: Collection Scheepstra cabinet, Roden

The last example is one of the poems that are given in separate chapters in the series, said to be written by Ligthart.Footnote94 The poems mostly repeat what happened in the main story in another form: a comparison, a poetic image, a commentary, a metaphor, or an analogy. One of the poems is an epic simile; it is called “Chicks and children” and compares a hen taking care and protecting her chicks with a mother doing the same for her children. Jetses helped to interpret the simile by drawing images of the vehicle, the hen, and its chicks in colour and giving the tenor, mother, and children in silhouette, both in the old and the new versions.Footnote95

The belles-lettres accompanying the main, realistic stories about the children function as both places of play and places of learning for the protagonists. They can enter those places in their minds. The stories entertain them, they may recognise their own pleasures and pains, chances and challenges, and in many of the stories a lesson is included. By focalising through the protagonists’ eyes, readers do not only co-read what the protagonists read, they also co-recognise, co-enjoy, and co-learn, often directed in text and image by the producers’ conception of truth and untruth.

Conclusion

The series of primers produced by Jan Ligthart, Hindericus Scheepstra, and Cornelis Jetses are more than illustrated books. The depicted locales in which the stories are set, the outer places, are highly idealistic. They can be related to progressive educational ideas, the inner space, with its pedagogical optimism and great expectations of children’s futures. While Ligthart’s and Scheepstra’s texts for adults are imbued with the rhetoric of progressive education, mentioning concepts such as the child’s interest, world, and experience, neither text nor image in the series enforce radical breaks with former pedagogical models; family life still forms the core of a child’s education, with a caring mother in the centre, and, rather than dethroning the teacher, a new kind of teacher is presented. Given the specific communication situation of children’s stories, in which adults decide what children read both on the level of production and on the level of consumption, the children’s stories can be seen as spaces of adult power, instructing children in expected behaviour and performances. These series did so in a way that was very attractive for the child, representing places children knew well from their own lives and using imaginary settings of children’s experiences that offered young readers worlds to imagine themselves in while at the same time signifying what they should understand as truthful and untruthful. The revisions of the illustrations reveal a continuing attention for keeping the texts attractive and up to date, including even more hints towards the educational ideas of the writers. The inner space revealed in the outer places, in text and in complementary interaction with the illustrations, indirectly instructed adult educators such as teachers and parents, as well. Consequently, the continuum between the Dionysian fears and the Apollonian ideal, expressed in the educational poetics of the authors, was filled in by educational ideas expressed on a concrete level of depicted locations, bringing those ideas to a general public of both children and adults.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Willemijn de Jong for her research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sanne Parlevliet

Dr. Sanne Parlevliet is associate professor at the Nieuwenhuis Institute, University of Groningen, the Netherlands, Department of Education. She has published on the history of children’s literature, literature in culture, cultural transmission and, identity and identification in historical fiction for children and the reciprocity between the history of children’s literature and the history of education.

Hilda T.A. Amsing

Dr. Hilda T.A. Amsing is professor of the history of education at the Nieuwenhuis Institute, University of Groningen, the Netherlands, Department of Education. She has a Master’s in educational sciences and a PhD in the field of the history of education. Her published articles include studies of Dutch education policies and educational reform. Her current research focuses on educational innovations in the post war era.

Notes

1 Jeroen J.H. Dekker, Educational Ambitions in History. Childhood and Education in an Expanding Educational Space from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2010), 104.

2 According to Oelkers “Pädagogik ist immer Reformpädagogik gewesen” since “Es gibt nie Zufriedenheit mit dem Status Quo”: Jürgen Oelkers. Reformpädagogik. Eine kritische Dogmengeschichte (Weinheim: Juventa Verlag, 1989), 35.

3 Jürgen Oelkers, “Break and Continuity: Observations on the Modernization Effects and Traditionalization in International Reform Pedagogy,” Paedagogica Historica 31, no. 3 (1995): 675–713; John Howlett, Progressive Education. A Critical Introduction (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

4 e.g. Freinet and Decroly longed for a new era. Angelo van Gorp, “Ovide Decroly a Hero of Education: Some Reflections on the Effects of Educational Hero Worship,” in Educational Research: Why “What Works” Doesn’t Work, ed. P. Smeyers and M. Depaepe (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006), 37–50; Nicholas M. Beattie, “Freinet and the Anglo‐Saxons,” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 28, no. 1 (1998): 33–45. e.g. Decroly, Montessori, and Claparède were inspired by experimental psychology: Rita Hofsttter and Bernard Schneuwly, “Progressive Education and Educational Sciences: The Tumultuous Relations of an Indissociable and Irreconcilable Couple? (late 19th–mid 20th century),” in Passion, Fusion, Tension: New Education and Educational Sciences, ed. Rita Hofstetter and Bernard Schneuwly (Bern: Peter Lang, 2006), Introduction, 1–15; R. Hofstetter and B. Schneuwly, “Knowledge for Teaching and Knowledge to Teach: Two Contrasting Figures of New Education: Claparède and Vygotsky,” Paedagogica Historica 45, no. 4-5 (2009): 605–29; Angelo van Gorp, Marc Depaepe, and Frank Simon, “Backing the Actor as Agent in Discipline Formation: An Example of the ‘Secondary Disciplinarization’ of the Educational Sciences, based on the Networks of Ovide Decroly (1901–1931),” Paedagogica Historica 40, no. 5-6 (2004): 591–616.

5 Majorie Lamberti, “Radical Schoolteachers and the Origins of the Progressive Education Movement in Germany 1900–1914,” History of Education Quarterly 40, no. 1 (2000): 22–48.

6 Mineke van Essen and Jan Dirk Imelman, Historische pedagogiek. Verlichting, Romantiek en ontwikkelingen in Nederland na 1800 (Baarn: Uitgeverij Intro, 1999), 107; Wolgang Scheibe, Die Reformpädagogische Bewegung (Weinheim: Beltz Verlag, 1984), 5.

7 Marc Depaepe, Frank Simon, and Angelo van Gorp, ‘The “good practices” of Jozef Emiel Verheyen – Schoolman and Professor of Education at the Ghent University,” in Educational Research: Why “What Works” Doesn’t Work, ed. P. Smeyers and Marc Depaepe (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006), 17–36.

8 The term “education” is used in this article in the broader meaning, stretching beyond the context of the classroom and school.

9 See J.D. Imelman and W.A.J. Meijer, De Nieuwe School gisteren and vandaag (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1986); Barbara C. de Jong, Jan Ligthart (1859–1916). Een schoolmeester-pedagoog uit de Schilderswijk (Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1996).

10 Rita Ghesquiere and Vanessa Joosen, “Van de kleine naar de grote wereld. Gezinsboeken en schoolverhalen,” in Een land van waan en wijs. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse jeugdliteratuur, ed. Rita Ghesquiere, Vanessa Joosen, and Helma van Lierop-Debrauwer (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, 2014), 317–19.

11 De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 215.

12 De Jong, Jan Ligthart; N.F. Noordam, “De plaats van Scheepstra in het auteursdriemanschap Hoogeveen, Ligthart en Scheepstra,” Pedagogische Studiën 50, no. 9 (1973): 339–43.

13 i.e. Jacques Vos, “Hindericus Scheepstra,” in Lexicon van de Jeugdliteratuur, ed. Jan van Coillie, Wilma van der Pennen, Jos Staal, and Herman Tromp (Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff, 14 oktober 1994); Harry Bekkering, Aukje Holtrop, and Kees Fens, “De eeuw van Sien en Otje. De twintigste eeuw,” in De hele Bibelebontse berg. De geschiedenis van het kinderboek in Nederland and Vlaanderen van de middeleeuwen tot heden, ed. Harry Bekkering et al. (Amsterdam: Querido, 1990), 437–54; De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 211–44; Jan A. Niemeijer, De wereld van Cornelis Jetses (Kampen: Uitgeverij Kok, 2004), 79–107; Margreet van Wijk-Sluyterman,“Cornelis Jetses,” in Lexicon van de Jeugdliteratuur, ed. Jan van Coillie, Wilma van der Pennen, Jos Staal,and Herman Tromp (Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff, 15 februari 2005); Rita Ghesquiere and Vanessa Joosen, “Van de kleine naar de grote wereld,” in Een land van waan en wijs. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse jeugdliteratuur, ed. Rita Ghesquiere, Vanessa Joosen, and Helma van Lierop-Debrauwer (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, 2014), 317–19; Amalia Astari and Rick Honings, “Met Ot en Sien naar Indië,” Internationale Neerlandistiek 56, no. 2 (2018): 99–120.

14 Schreuder and Dekker refer to this as “mental space”, one of the conditions for realising educational ambitions, next to demographic space, socioeconomic and financial space, and the relation between private and public space: cf. Pauline R. Schreuder and Jeroen J.H. Dekker, “The Emergence of Institutional Educational Spaces for Young Children: In Pursuit of More Controllability of Education and Development as Part of the Long-Term Growth of Educational Space in History,” in Educational Research: The Importance and Effects of Institutional Spaces, ed. P. Smeyers, M. Depaepe, and E. Keiner (Dordrecht: Springer, 2013), 61–78.

15 cf. Sanne Parlevliet, “Daily Chicken. The Cultural Transmission of Bourgeois Family Values in Adaptations of Literary Classics for Children 1850–1950,” Journal of Family History. Studies in Family, Kinship and Demography 36 (2011): 464–82.

16 Peter Hunt, “Unstable Metaphors: Symbolic Spaces and Specific Places,” in Space and Place in Children’s Literature, 1789 to the Present, ed. Maria Sachiko Cecire, Hannah Field, and Malini Roy (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015), 24.

17 De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 213–15.

18 Cornelis Jetses, “C. Jetses 80 jaar,” Ik blijf werken. Orgaan van de bedrijfsvereniging van J.B. Wolters 8 (1953): 111–12. All translations of Dutch quotations are our own.

19 Björn Sundmark, “The Visual, the Verbal, and the Very Young: A Metacognitive Approach to Picturebooks,” Acta Didactica Norge 12 (2018), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/adno.5642

20 Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott, “The Dynamics of Picturebook Communication,” Children’s Literature in Education 31, no. 4 (2000): 225–39; Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott, How Picture Books Work (New York: Garland, 2001).

21 Saskia de Bodt and Rita Ghesquiere, “Verhalen vertellen in woord en beeld. Prentenboeken en geïllustreerde jeugdboeken,” in Een land van waan en wijs. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse jeugdliteratuur, ed. Rita Ghesquiere, Vanessa Joosen, and Helma van Lierop-Debrauwer (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, 2014): 347–50; Nico Boerma, Aernout Borms, Alfons Thijs, and Jo Thijssen, Kinderprenten, volksprenten, centsprenten, schoolprenten: Populaire grafiek in de Nederlanden 1650–1950 (Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2014).

22 Saskia de Bodt, De verbeelders. Nederlandse boekillustratie in de twintigste eeuw (Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2014), 351.

23 Ria Christens, Marc Depaepe, and Mark D’hoker, “From Enlightened Tutelage to Means of Emancipation. The Educational Function of Catholic Children’s and Youth Literature in Flanders in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” in Religion, Children’s Literature, and Modernity in Western Europe, 1750–2000, ed. Jan de Maeyer, Hans-Heino Ewers, and Rita Ghesquiere (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), 59–63.

24 Anne de Vries, “Views on Children’s Literature in the Netherlands After 1880,” in Aspects and Issues in the History of Children’s Literature, ed. Maria Nikolajeva (Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), 115–26; De Bodt, De verbeelders.

25 Hindericus Scheepstra, Onderwijs en opvoeding. Beknopt leerboek voor kweek- en normaalscholen, 6th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1912), 68.

26 Christens, Depaepe, and D’Hoker, “From Enlightened Tutelage,” 60.

27 Jan A. Niemeijer, De wereld van Cornelis Jetses (Kampen: Uitgeverij Kok, 2004).

28 De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 217.

29 Scheepstra, Onderwijs en opvoeding, 52–3.

30 cf. Sanne Parlevliet, “Foxing the Child: The Cultural Transmission of Pedagogical Norms and Values in Dutch Writings of Literary Classics for Children 1850–1950,” Paedagogica Historica 48, no. 4 (2012): 551.

31 Ibid., 566.

32 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, “Voorbericht juni 1904,” in Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, ed. Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, 10th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1949), 3.

33 Scheepstra, Onderwijs en opvoeding, 33, 52, 65.

34 Hunt, “Unstable Metaphors,” 24.

35 Chris Jenks, Childhood (London: Routledge, 2005), 65.

36 Hunt, “Unstable Metaphors,” 24.

37 Bob Verschoor, Dicht bij huis. Het Groningen van Cornelis Jetses (Bedum: Profiel Uitgeverij, 2014); Niemeijer, De wereld van Cornelis Jetses.

38 Nikolajeva and Scott, How Picture Books Work.

39 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Dicht bij huis. Eerste stukje, 5th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1953), 3.

40 Nikolajeva and Scott, How Picture Books Work.

41 Gilles van Hees, “Aan de Collega’s,” in Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Vierde stukje, 9th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1948), 2.

42 cf. Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 24th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1928), 67; 10th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1949), 65; Verschoor, Dicht bij huis, 23.

43 Jan Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1916), 158–79.

44 Jenks, Childhood, 63.

45 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen, 165.

46 Ibid., 176–7.

47 Christens, Depaepe and D’hoker, “From Enlightened Tutelage to Means of Emancipation”, 61.

48 cf. Parlevliet, “Foxing the Child,” 549–70.

49 Jan Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen. Tweede bundel (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1917), 17–18.

50 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Pim en Mien. Eerste stukje, 18th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1918), 10.

51 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Pim en Mien. Eerste stukje, 11th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1949), 10.

52 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen. Tweede bundel, 15.

53 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Vierde stukje, 9th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1928), 49.

54 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Pim en Mien. Eerste stukje, 11th rev. ed., 1950, 10; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Vierde stukje, 9th rev. ed. (1948), 48.

55 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Vierde stukje, 14th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1923), 24.

56 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen. Tweede bundel, 26.

57 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Vierde stukje, 9th rev. ed., 76.

58 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 24th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1928), 28; Nog bij moeder. Derde stukje, 6th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1943), 17; Nog bij moeder. Vierde stukje, 9th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1948), 51.

59 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen, 17.

60 Ibid., 48.

61 Marc Depaepe, Frank Simon, Melanie Surmont, and Angelo van Gorp, “Menschen in Welten. Ordnungsstrukturen des Pädagogischen auf dem Weg zwischen Haus und Schule,” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 52 (2007): 96–109.

62 Ibid., 39–60.

63 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Derde stukje, 15th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1925), 80.

64 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Pim en Mien. Eerste stukje, 18th ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1918), 10-15.

65 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 24th ed., 33.

66 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1949), 49–52; 24th ed., 50–52.

67 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Tweede stukje, 3rd rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1953), 88.

68 The idea of “the blessings of Nature” and the countryside is shared by many educational reformers, and forms the core of the concept of the so-called Open-Air schools: cf. Geert Thyssen and Marc Depaepe, “The Sacralization of Childhood in a Secularized World: Another Paradox in the History of Education? An Exploration of the Problem on the Basis of the Open-Air School Diesterweg in Heide-Kalmthout,” in Between Educationalization and Appropriation, ed. Marc Depaepe (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012), 89–117.

69 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen, 52.

70 Jan Ligthart, Vrijheid en discipline in de opvoeding (Baarn: Hollandia, 1909).

71 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1949), 65; 24th ed. (1928), 67.

72 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Tweede stukje, 9th rev. ed. (Groningen, 1948), 19; 24th ed. (1928), 16; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 39; 24th ed. (1928), 40.

73 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

74 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Derde stukje, 6th rev. ed. (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1943), 14, 21; 23rd ed. (1928), 59, 68; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 5, 16; 24th ed. (1928), 4, 22, 35.

75 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 13, 73; 24th ed. (1928), 13.

76 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Derde stukje, 23rd ed. (1928), 16.

77 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 24; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Derde stukje, 23rd ed. (1928), 74.

78 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 54; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Vierde stukje, 23rd ed. (1928), 15.

79 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Tweede stukje, 9th rev. ed. (1948), 34; 24th ed. (1928), 35; 9th rev. ed. (1948), 38.

80 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen, 21–2.

81 Jan Ligthart and Hindericus Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Derde stukje, 15th ed. (Groningen, 1925), 80.

82 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen. Tweede bundel, 159–80.

83 De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 221.

84 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen. Tweede bundel, 170.

85 Ibid., 118.

86 Individuation has to be understood as achievement of self-actualisation in which the conscious and unconscious are integrated.

87 Howlett, Progressive Education.

88 Ligthart, Verspreide opstellen, 184.

89 De Jong, Jan Ligthart, 225.

90 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Eerste stukje, 10th rev. ed. (1949), 14–17.

91 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Tweede stukje, 3rd rev. ed. (1953), 85; Ligthart and Scheepstra, Derde stukje, 26th ed. (1950), 32–3.

92 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Tweede stukje, 24th ed. (1928), 67.

93 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Nog bij moeder. Tweede stukje, 9th rev. ed. (1948), 67.

94 Vos, “Hindericus Scheepstra,” 4.

95 Ligthart and Scheepstra, Buurkinderen. Derde stukje, 15th ed. (1925), 22; 26th ed. (1950), 22.