ABSTRACT

The current study examined the associations between students’ perceptions of classroom interactions and students’ emotional and behavioral engagement. Given the nested structure of the data, multilevel analyses were employed to examine these associations. A total of 1769 Norwegian fifth to tenth graders from 100 classes and 10 schools participated in a web-based survey. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics, confirmatory factor analysis and multilevel structural equation modeling. The results indicated that students who perceived high-quality classroom interactions were more engaged in school, and teachers’ emotional support showed the strongest association with engagement at both levels. Furthermore, the findings indicated that primary school students were more engaged emotionally than lower secondary school students, and female students were more behaviorally engaged than male students.

Introduction

Teachers make countless numbers of decisions every day, such as how to facilitate interactions with and among students (Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, Citation2008). Teachers must ensure that their students are engaged in the learning process to optimize each student’s learning and development and to prevent gradual disengagement, school failure or dropout. The research question of the current study is how classroom interactions and student engagement (SE) are associated based on student self-reports, when including gender and grade level as covariates and SES as a control variable.

An ecological approach to studying schools underscores the importance of considering how classroom contextual factors engage students. Teachers’ actions in the classroom are of importance, including how teachers promote teacher–student interactions, their methods of instructional delivery and their support for SE (Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, Citation2012). The current study’s underpinning theory is based on the “Teaching Through Interactions” framework, which sees classroom interactions as important for successful student development and uses measures of teachers’ emotional support, classroom organization and instructional support (Hamre et al., Citation2013). Previous research has revealed an association between high-quality classroom interactions and student learning, effort, adaptive learning strategies, achievement, well-being, behavior, motivation and engagement, among others (e.g., Allen et al., Citation2013; Allen, Pianta, Gregory, Mikami, & Lun, Citation2011; Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, Citation2012; Roorda, Koomen, Spilt, & Oort, Citation2011). Despite this evidence, Pianta and colleagues (Citation2007) claimed that the testing of schools and students receives more attention than the quantity and quality of classroom interactions (Pianta, Belsky, Houts, Morrison, & The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, Citation2007). More than ten percent of schools in the US chronically fail to engage students in productive learning opportunities (NCES, Citation2014 in Pianta, Citation2016).

The present research was conducted in a Norwegian context. Because most previous research on SE is from the US (Quin, Citation2017), it is important to note the differences between the school contexts in the US and Norway and other Nordic countries. In recent decades, Nordic countries have aimed to build a Nordic Education Model comprising a compulsory school system and “A School for All” (Blossing, Imsen, & Moos, Citation2014). In particular, classrooms in Norway, Sweden and Finland emphasize that equal opportunities will be provided for all students within this framework (Klette et al., Citation2018). According to Gustafsson and Nielsen (Citation2016), there is some evidence that countries with similar cultures and educational policies have similar educational results. Being part of The Nordic Education Model indicates that classrooms in Norway exhibit variance and diversity in students. This might affect classroom interactions and SE. Further, results (OECD, Citation2015) indicate that Norwegian students exhibit better well-being than the US students, based on questions about “sense of belonging at school” and “schoolwork-related anxiety”.

Based on a systematic review, several studies from the US indicate that classroom interactions are an important contributor to SE (Quin, Citation2017). However, there are few research studies from Norway and other Nordic countries regarding classroom interaction and SE (Haapasalo, Välimaa, & Kannas, Citation2010; Virtanen, Lerkkanen, Poikkeus, & Kuorelahti, Citation2015). Further, only a few studies concerning SE involve multilevel approaches nested at a school level (Lee, Citation2012; Reyes, Brackett, Rivers, White, & Salovey, Citation2012; You & Sharkey, Citation2009). A Nordic study from Finland found variations in classroom interactions and behavioral engagement among classrooms based on classroom observations and surveys (Virtanen et al., Citation2015). Moreover, SE is thought to be a dynamic construct, and one cannot label a student as engaged or not engaged (Park, Holloway, Arendtsz, Bempechat, & Li, Citation2012). Thus, assuming that SE varies between classrooms, a student might be highly engaged in one classroom but less engaged in another.

Based on the outlined introduction, the aim of the present study is to increase knowledge to the association between students’ perceived classroom interactions and SE in a Norwegian school context and to investigate how classroom interactions and SE are associated, based on student self-reports, when including gender and grade level as covariates and SES as a control variable.

Student Engagement

SE is defined as “energy in action” (Appleton, Christenson, Kim, & Reschly, Citation2006, p. 428). Several subtypes of SE exist, such as academic, cognitive, intellectual, institutional, emotional, behavioral, social and psychological (Taylor & Parsons, Citation2011). Most commonly, SE is studied as a multidimensional construct that consists of three interrelated subtypes: behavioral (i.e., time on task), emotional (i.e., students’ feelings, attachment and ties to their school) and cognitive (i.e., self-regulation and learning strategies) (e.g., Fredricks & McColskey, Citation2012; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, Citation2004; Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993).

Teachers want to encourage their students to be motivated, engaged and enthusiastic. SE is related to positive academic and social aspects of school life (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Conner & Pope, Citation2013; Kortering & Christenson, Citation2009) and psychosocial benefits (Reddy, Rhodes, & Mulhall, Citation2003). Moreover, SE predicts enhanced student achievement, retention and graduation from high school (Barkatsas, Kasimatis, & Gialamas, Citation2009; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Miller, Greene, Montalvo, Ravindran, & Nichols, Citation1996; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2000), the acquisition of knowledge and skills (Furlong et al., Citation2003; Ladd & Dinella, Citation2009), and improved emotional functioning (Skinner, Furrer, Marchand, & Kindermann, Citation2008). Further, SE protects against risky adolescent behaviors such as truancy, dropout, gang involvement and delinquency (Finn & Voelkl, Citation1993; Janosz, Archambault, Morizot, & Pagani, Citation2008; Jimerson, Campos, & Greif, Citation2003; Li & Lerner, Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2008).

Students who are engaged pay attention and participate in classroom discussions, exert effort in classroom activities and exhibit an interest and motivation to learn (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Marks, Citation2000; Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993). Moreover, they share ideas, ask questions and follow each other’s leads. In classrooms where students are engaged, teachers can clearly identify what their students understand and which concepts and topics need more explanation and deeper discussion. Engaged students who work in groups continue to discuss, ask each other and their teachers questions, listen critically to each other and argue with examples from their own lives and from previous knowledge. Classrooms in which most students are actively engaged have more energy, and students give more energy to their peers and to their teachers (Furrer, Skinner, & Pitzer, Citation2014).

Effective learning is contingent upon the extent to which students are engaged in learning activities in the classroom (Chen, Citation2005; Finn & Rock, Citation1997; Osterman, Citation2000; Wang & Pomerantz, Citation2009). Middle school students who report higher levels of SE are 75% more likely to obtain higher grades and attend school more regularly than students with less engagement (Klem & Connell, Citation2004). However, it is important to note the findings of Park and colleagues (Citation2012), who indicated that one cannot label a student as engaged or disengaged because engagement is a dynamic, malleable construct (fluid across time and context) in which particular contextual conditions affect a student’s engagement (Park et al., Citation2012). Therefore, studying differences in SE at the classroom level is important.

Despite the importance of SE and the amount of research in this field in general, schools in several countries still fail to engage many students (Lee, Citation2014). Possible reasons for the lack of engagement in the US might be that middle and high school classrooms tend to be characterized by an increase in teachers’ control and discipline, which is related to teachers’ monitoring, with fewer opportunities for students’ decision making, control and self-management (Eccles et al., Citation1993). A study of Norwegian teachers found similar results (Roland, Citation2012). Moreover, when students enter middle school, they often experience a transition from a small, more personalized, task-focused classroom environment to a larger, impersonal, and achievement-oriented environment (Loukas & Murphy, Citation2007). Some countries have different teachers for different subjects, which may make it more difficult to establish close relations between teachers and students and thus affect SE.

Adding complexity to this field, Wang and colleagues (Citation2015) claim that the school system influences student work, the classroom motivational climate and the school-wide climate and practices (Wang, Chow, Hofkens, & Salmela-Aro, Citation2015). Each of these aspects might establish a school environment that fails to meet all students’ needs and thus reduces student motivation, engagement and outcomes over time, which are particularly important among young adolescents. Therefore, SE seems to be one of the greatest challenges that teachers, educators and researchers face. One challenge is to close the “engagement gap”, i.e., keep students engaged in the entire learning process as they move through the educational system (Yazzie-Mintz, Citation2007).

Emotional and Behavioral Engagement

Emotional engagement (EMEN) and behavioral engagement (BEEN) are subtypes of SE included in the current study. EMEN, or affective engagement, concerns students’ feelings and attachment toward their school, learning, teachers and peers (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Jimerson et al., Citation2003), students’ positive and negative reactions or feelings, and students’ ties to their school. These factors might influence students’ willingness to perform schoolwork and to attend school. Further, EMEN is related to experiences of warmth (Skinner et al., Citation2008), bonding, connectedness, attachment, involvement (Jimerson et al., Citation2003; Libbey, Citation2004), school belonging, acceptance by teachers and peers (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Finn, Citation1993; Fredricks et al., Citation2004) and membership in school (Wehlage, Rutter, Smith, Lesko, & Fernandez, Citation1989).

BEEN includes observable student actions, involvement or participation, both academically and socially while at school; students’ positive conduct; efforts on task; participation in extracurricular activities; attendance; and work habits (Chapman, Citation2003; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Jimerson et al., Citation2003; Skinner et al., Citation2008). Examples are paying attention, asking pointed questions and seeking help to enable task accomplishment, and participating in discussions in class. Briefly, BEEN is “engagement in the life of the school” (Yazzie-Mintz, Citation2007), which is considered crucial for achieving positive academic outcomes and preventing school dropout (Archambault, Janosz, Morizot, & Pagani, Citation2009; Janosz et al., Citation2008).

Previous research has revealed that EMEN might affect students’ academic performances via BEEN (Finn & Zimmer, Citation2012; Pietarinen, Soini, & Pyhältö, Citation2014; Roorda et al., Citation2011; Voelkl, Citation2012; Walker & Greene, Citation2009; Wang & Degol, Citation2014). Although changes in EMEN might change BEEN, students do not have to have EMEN to perform well academically (Wang et al., Citation2015; Wang & Peck, Citation2013). Despite the somewhat inconsequent claims, EMEN and BEEN are both treated as dependent variables in the present study.

Classroom Interaction

A common description is that classroom interaction is a multidimensional concept that includes emotional support, classroom organization and instructional support (e.g., Pianta et al., Citation2008). Emotionally supportive teachers are sensitive to students’ needs and interests and are responsive and warm toward students (Pianta et al., Citation2008). Quality classroom organization involves using proactive rather than reactive approaches to discipline, establishing clear and stable routines, carefully monitoring students to keep them involved in academic tasks and providing interesting activities (Emmer & Stough, Citation2001; Pianta et al., Citation2008). The concept of monitoring is used in the current study and corresponds to behavior management and negative climate according to the perspective of Pianta and colleagues (e.g., Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, Citation2012), but it relates less to productivity (Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018). Instructional support (or instrumental support; Federici & Skaalvik, Citation2014; Malecki & Demaray, Citation2003) involves providing a setting and support for students (Yates & Yates, Citation1990), creating opportunities for conceptual development, and offering appropriate questioning and feedback for students (La Paro, Pianta, & Stuhlman, Citation2004; Pianta et al., Citation2008). These three domains are important for students’ academic achievement and SE (e.g., Allen et al., Citation2013; Hamre & Pianta, Citation2005; Howes et al., Citation2008). Although student achievement as a concept is not included in the present study, it is appropriate to reveal the importance of classroom interaction and SE for achievement as well as how they are related to each other.

Classroom Interaction and Student Engagement

SE and academic achievement are often viewed as individual attributes more than outcomes of teachers’ support or teaching structures (Urdan & Schoenfelder, Citation2006). However, several factors, such as individual characteristics and relationships with parents, peers and teachers, have been reported as influencing SE (You & Sharkey, Citation2009). Previous research indicates that classroom interactions are associated with SE (e.g., Hughes & Chen, Citation2011; Lee, Citation2012; Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, Citation2012; Roorda et al., Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2008; Spilt, Koomen, & Thijs, Citation2011; Willms, Friesen, & Milton, Citation2009). The findings from a study of 9th- and 10th-graders in Norway indicated the importance of teachers’ emotional and instrumental support on the measured motivational constructs (Federici & Skaalvik, Citation2014). When students have teachers who care and encourage their development, students are more likely to be engaged in school. A study of high school students indicated that close teacher-student relations were associated with students’ positive attitudes in the classroom and views of school (Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993). The findings from another study indicated that stronger teacher-student interactions were associated with higher academic achievement and with fewer disciplinary problems (Crosnoe, Johnson, & Elder, Citation2004). Klem and Connell (Citation2004) indicated that students and teachers reported that teacher support is important for SE. Students who perceive teachers as creating caring, well-structured learning environments with high expectations that are clear and fair are more likely to report SE. Further, high SE is associated with higher attendance and test scores, which indicates an indirect link between student perceptions of teacher support and academic performance via SE (Klem & Connell, Citation2004).

However, teacher-student interactions promote student outcomes in many ways (e.g., Patrick, Ryan, & Kaplan, Citation2007; Pianta et al., Citation2008). Students’ relations with both teachers and peers are fundamental for developing academic engagement and achievement (Furrer et al., Citation2014). Such quality classroom interactions are particularly important for students with high-incidence disabilities (Murray & Pianta, Citation2007) or low socioeconomic status (SES) (Pianta et al., Citation2008).

In previous theories, SE has been suggested to be both a process and an outcome (e.g., Bryson, Cooper, & Hardy, Citation2010; Reschly & Christenson, Citation2012). SE might be seen as a relational process activated by reciprocal interpersonal relationships (Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, Citation2012; Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993), indicating that classroom interaction is associated with SE (“engaging students”). SE as an outcome refers to what students do (“students engaging”). In this view, one could claim that the process is not SE but that SE is an outcome. Moreover, SE is also viewed as a mediator between students’ educational contexts and student outcomes (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Skinner et al., Citation2008). In the current study, we examine SE as an outcome, and we investigate how classroom interactions are associated with SE at the student and classroom levels. Therefore, we use SEM to model the causal relations between classroom interaction and SE.

Female students are more engaged than male students (Covell, Citation2010; Finn, Citation1989; Furrer & Skinner, Citation2003; Pagani, Fitzpatrick, & Parent, Citation2012), which may be related to declining self-reported SE from primary to secondary school, particularly among male students (Wigfield, Eccles, Schiefele, Roeser, & Davis-Kean, Citation2007). However, other studies show no gender differences in self-reported SE (Virtanen et al., Citation2015). Research indicates that SE and motivation decrease as students move through the educational system (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Klem & Connell, Citation2004; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2008; Wang & Eccles, Citation2012). In addition, students perceive decreasing classroom interaction from primary to secondary school (e.g., Bokhorst, Sumter, & Westenberg, Citation2010; Malecki & Demaray, Citation2002) or gradually from 5th to 10th grade (Bru, Stornes, Munthe, & Thuen, Citation2010). These research results indicate the importance of increasing high-quality classroom interactions and SE, particularly as students move through the educational system. In addition, high SES is associated with higher engagement among students (e.g., Finn, Citation1989; Finn & Cox, Citation1992). Therefore, gender and grade level are included as covariates and SES is included as a control variable in the current study.

Aims and Hypotheses

Research aim and Hypotheses

The aim of this study was to investigate the associations between students’ perceived classroom interactions and SE.

The research question of this study is how classroom interactions and SE are associated, based on student self-reports, when including gender and grade level as covariates and SES as a control variable.

Hypothesis 1a: High-quality classroom interactions are positively associated with EMEN and BEEN at both the student and classroom levels.

Hypothesis 1b: Female students and primary school students perceive more engagement compared to male students and lower secondary students, respectively, when controlling for SES.

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 1769 students from grades five to ten in 100 classrooms in 10 schools and 2 counties in Norway. The response rate for all students in the participating classes/schools was 80.6%.

Procedures

Students from the participating schools were invited to complete a self-reported web-based questionnaire during an ordinary 45-minute classroom period. Data were drawn from the first data collection at the end of the fall term in 2014. A teacher or a school administrator who had received instruction on how to implement the survey was present in the classroom. The study was conducted in accordance with the standards described by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. Only students whose parents had provided written consent were invited to participate in the survey. Students were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The sample was not randomized; however, both urban and rural as well as small and large schools in different geographical locations were included.

Missing

Missing data on the included measurements varied from 1.2% to 3.5%. None of the items had a high number of extremes (based on univariate statistics in SPSS). A full information maximum likelihood approach was used to address missing data, which allowed us to use all observations in the data set when estimating the parameters in the model.

Measurements

Classroom interaction was measured as a two-level construct, the student level and the classroom level, with three domains, students’ perception of teachers’ emotional support, classroom organization and instructional support, based on previous studies (Ertesvåg, Citation2016; Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018; Havik, Citation2017). Ertesvåg and Havik (Citation2018) tested different measurement models of classroom interaction and found that a model of a three-dimensional concept at both the individual and classroom levels fit the data best. For more details on this measurement model, see Ertesvåg and Havik (Citation2018). More details about the three domains are given below.

Teachers’ emotional support is the affective aspect of classroom interactions and includes dimensions such as personal care and warmth toward the students (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2007; Hughes, Citation2002). Monitoring refers to whether the teacher redirects misbehavior and follows up with student behavior and learning expectations. Both of these measurements have four-item scales with a four-step scoring format (from 0 to 3): “Disagree strongly”, “Disagree a little”, “Agree a little” and “Agree strongly”. These scales are included in previous studies (e.g., Bru et al., Citation2010; Bru, Boyesen, Munthe, & Roland, Citation1998; Ertesvåg, Citation2009; Havik, Bru, & Ertesvåg, Citation2015). Instructional support is measured by a five-item scale based on Pianta and colleagues’ theoretical outline and its operationalization in the CLASS-S manual (Pianta, Hamre, & Mintz, Citation2012). Instructional support addresses teachers’ descriptions of clear learning targets, help in understanding concepts and facts, asking challenging questions, giving feedback and encouraging discussions that extend students’ knowledge (for more information, see Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018). The items were rated on a six-point scale (scored from 0 to 5) ranging from 0 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Completely true”. The mean scores of the items are included. The factorial structure of the students’ ratings of classroom interactions as a 3w(ithin)/3b(etween)-factor model has previously been validated (Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018). Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.84, 0.81, and 0.87 for emotional support, monitoring, and instructional support, respectively.

SE is a multidimensional concept, and several components have been identified in previous studies. However, most studies include EMEN and BEEN, as in the current study (e.g., Lee, Citation2014). The EMEN and BEEN measurements are derived from Skinner, Kindermann, and Furrer (Citation2009). They include four-item scales with a four-step scoring format (from 0 to 3): “Disagree strongly”, “Disagree a little”, “Agree a little” and “Agree strongly”. The reliability of the internal consistency was good for both EMEN and BEEN (Cronbach’s alpha .89 and .88). EMEN was included as a two-level construct with a good model fit with four observed variables, while BEEN was included as a one-level construct. EMEN included the following four variables: “Class is fun”, “I enjoy learning new things in class”, “When we work on something in class, I get involved” and “I think school work is interesting and useful”. BEEN included the following four variables: “I try hard to do well in school”, “In class, I work as hard as I can”, “I pay attention in class” and “When I’m in class, I listen very carefully”. The factor loadings for classroom interactions and SE are presented in the appendices.

In addition, grade level and gender were included as covariates, and SES was included as a control variable. Gender was scored “1” for male students and “2” for female students. Grade level was scored from 5 to 10, consistent with the grade level of the student. The control variable SES was measured by two items that addressed students’ perceived family wealth and housing standards: “I think our family, compared with others in Norway, is” (response options: “Very poorly off”, “Poorly off”, “Average”, “Well off” and “Very well off”) and “How is the standard of the house or the flat where you live?” (“Very bad”, “Quite bad”, “Average”, “Quite good” and “Very good”). Items were rated on a five-point scale (scored from 1 to 5). Higher scores indicated high SES. The two SES items have been used in previous studies (e.g., Bru et al., Citation2010; Veland, Midthassel, & Idsoe, Citation2009).

Statistical Data Analysis

Descriptive data (means, crosstabs and Cronbach’s alpha) were obtained using SPSS 21.0 (Norusis, Citation2011). The model was fitted to the data using a robust maximum likelihood procedure implemented in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–Citation2015). Considering the nested structure of the data, students (level 1) were nested within classrooms (level 2). To evaluate fit indices, Hu and Bentler's (Citation1999) recommendations for goodness of fit were followed: cut-off values of 0.95 for the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), 0.08 for the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and 0.05 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A multilevel model was used to test the hypothesis. We expected that high-quality classroom interactions would be positively associated with EMEN and BEEN at both the student and classroom levels and that female students and primary school students would perceive more engagement compared to male students and lower secondary students, respectively.

Results

The aim of the present study was to examine how classroom interactions are associated with SE. Hypothesis 1a was that high-quality classroom interactions would be positively associated with EMEN and BEEN at both the student and classroom levels. In hypothesis 1b, we assumed that female students would be more engaged than male students and that younger students would be more engaged than older students, when controlling for SES.

The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) of the multilevel model was .00 for BEEN, which indicates that BEEN had no variance at the classroom level. However, the ICC was .10 for EMEN, indicating that approximately 10% of the variance of EMEN was explained at the classroom level. Design effect considers group size, and design effects greater than 2.0 are often used as a criterion to judge the statistical relevance of a multilevel model (Muthén & Satorra, Citation1995). The design effect for EMEN in this model was 2.6. Therefore, multilevel structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the associations between classroom interactions and SE at both the classroom and student levels. This approach is suitable to consider the association between classroom interaction and SE at the classroom level as well as at the individual level based on students’ perceptions.

Descriptive Analyses

The sample comprised 49.4% male students and 100 classes/clusters (average cluster size 17.69). shows the mean values, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis for the included measurements. The mean value was significant higher for BEEN (2.32) than for EMEN (1.91), which is in line with a study by Skinner et al. (Citation2008).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), Skewness (Ske) and Kurtosis (kurt) for the measurements.

shows the results of independent-sample t-tests of differences in BEEN and EMEN between genders. Male students rated BEEN significantly lower (2.26) than female students did (2.39). There were no significant gender differences in EMEN. shows grade differences. Fifth- to seventh-grade students reported significantly higher BEEN (2.54) and EMEN (2.42) than 8th- to 10th-grade students did (BEEN 2.29 and EMEN 1.81).

Table 2. Independent sample t-test – gender differences.

Table 3. Independent sample t-test – primary vs lower secondary school level.

Multilevel Model

A multilevel model was used to investigate the research questions and to test the hypotheses for the current study. This approach is suitable because we wanted to consider both the classroom and student levels of a phenomenon and because classroom interaction is considered to be a classroom-level phenomenon, given that students perceive the same teacher in the same classroom, and has previously been measured as a two-level construct (Ertesvåg, Citation2016; Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018; Havik, Citation2017).

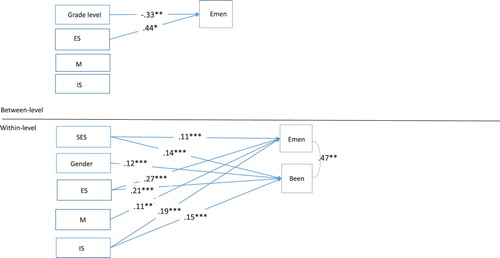

To simplify the model, BEEN was not included at the classroom level based on ICC data. The final model includes associations between teachers’ monitoring, emotional and instructional support and SE. Model-fit indices for the final model were χ2 1.172(2); p < .56; RMSEA = .000; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.006; SRMRw = .004; SRMRb = .001. These indices indicate a good fit, according to Hu and Bentler (Citation1999). Due to the relatively large number of subjects, a traditional χ2 test may provide an inadequate assessment of model fit (Jöreskog, Citation1993). Thus, the χ2 test was performed but is not discussed. Notably, research on the interpretation of global fit indices in multilevel models is limited ().

Figure 1. The associations between teachers’ monitoring, emotional and instructional support and SE.

Multilevel SEM was included to account for student- and classroom-level variances. The findings showed significant associations between teachers’ support and EMEN and BEEN. The strongest association was between emotional support and EMEN at the student level. In addition, there was a significant association between emotional support and EMEN at the classroom level, indicating classroom differences: classrooms with emotionally supportive teachers had students with higher levels of EMEN. This finding indicates that the teacher’s emotional support was the most important factor for each student’s engagement in addition to students in classrooms in which teachers were emotionally supportive.

There were significantly positive associations between teachers’ instructional support and EMEN and BEEN at the student level. The weakest association was between monitoring and EMEN. These findings indicate that when students perceive teachers to be supportive and monitor them well, students perceive higher EMEN.

Further, the findings indicated that classroom interaction was more strongly associated with EMEN than with BEEN. This finding indicates that classroom interactions are most important for students’ EMEN (i.e., students’ feelings and attachment towards their school, learning, teachers and peers) (e.g., Fredricks et al., Citation2004), which might influence their willingness to perform schoolwork and attend school. Notably, there was a correlation between emotional and behavioral engagement at the student level (.47**).

Gender was associated with BEEN such that female students showed more BEEN than male students did. The findings showed no gender differences in perceived BEEN. Moreover, grade level was negatively associated with EMEN such that older students perceived less EMEN than did students at lower grade levels. SES was associated with both EMEN and BEEN such that students with higher SES tended to be more engaged in school than students with lower SES.

Discussion

Classroom Interaction and Student Engagement

The aim of the present study was to investigate the associations between classroom interactions and SE based on student self-reports when including gender and grade level as covariates and SES as a control variable. Moreover, this study investigated whether classrooms differed with respect to SE and the extent to which classroom interaction predicted classroom differences regarding SE. The hypotheses were that high-quality classroom interactions would be positively associated with SE at both the student and classroom levels and that female students and primary school students would perceive more engagement compared to male students and lower secondary students, respectively.

Based on the ICC, EMEN was measured as a two-level construct using student and classroom levels, while BEEN was measured at the student level only. The findings indicated that EMEN is only a classroom-level phenomenon, while BEEN does not differ depending on the classroom a student attends but rather reflects each student’s individual choices and behaviors. EMEN is partly (approximately ten percent) related to the classroom level, which indicates that it is mainly an individualized concept; however, which classroom a student attends affects students’ EMEN. The practical implications of this finding are that teachers should support students’ EMEN in their classroom. Given that the unit of differentiation is mainly based on the individual student’s engagement, a teacher’s job is more demanding because students mostly show individual perceptions of engagement.

The current data confirmed the hypothesis that high-quality classroom interactions are positively associated with students’ EMEN and BEEN. However, the strength of these associations differed, which may have different explanations.

First, teacher support was significantly and positively associated with BEEN, indicating that when students perceive high levels of emotional and instructional support from teachers, they appear to work harder in class. This may be because their achievements, such as obtaining good grades and reaching their goals, improve, as researchers such as Conner and Pope (Citation2013) suggest. This finding is in accordance with a study by Furrer and colleagues, which indicated that students have more energy and work harder when teachers monitor students’ work (i.e., when they observe what students understand and address whether there are concepts that need additional explanation) (Furrer et al., Citation2014). Moreover, students who perceive higher-quality emotional support from teachers experience more feelings of belonging at school (Skinner et al., Citation2008) in addition to feelings of warmth and acceptance by teachers and peers (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Fredricks et al., Citation2004). However, Virtanen and colleagues (Citation2015) found no direct association between teachers’ emotional support and BEEN, but they found an indirect effect between emotional support and BEEN via organizational and instructional support.

No significant association was found between monitoring and BEEN, indicating no link between teachers’ redirecting of misbehavior and follow-up of student behavior and learning expectations and students’ perceptions of their own actions, involvement and participation in school (BEEN). The measurement of monitoring corresponds mainly to classroom organization with the exception of productivity (Pianta et al., Citation2008). The findings did not support the hypothesis that monitoring is associated with BEEN. This may be because productivity was not included; this dimension probably has a stronger link to BEEN than the included dimensions (behavior management and negative climate). The degree of coherence might also explain the findings because the three domains of classroom interaction are correlated (Ertesvåg & Havik, Citation2018) in addition to the correlations between EMEN and BEEN.

Second, students’ perceived support and monitoring from teachers were significantly and positively associated with students’ EMEN. The strongest association was between teachers’ emotional support and EMEN, which is in line with previous research (e.g., Patrick et al., Citation2007; Reyes et al., Citation2012; Roorda et al., Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2008). This association was significant at both the student and classroom levels. The association between teachers’ emotional support and EMEN at the classroom level indicates that there are differences between classrooms and that students in classrooms with greater emotional support from the teacher appeared to show greater EMEN than students in classrooms with less emotional support. On the other hand, BEEN appeared to be a more individualized concept; the findings indicated no classroom differences in BEEN. These findings are in line with previous research indicating an association between EMEN and a feeling of connectedness with the teacher (Furrer & Skinner, Citation2003). Moreover, connectedness with the teacher is as an idea closely related to the emotional support of the teacher, which includes students feeling appreciated by teachers, teachers making academic activities more interesting and fun, and students feeling happy and comfortable in the classroom.

The findings from the descriptive analyses indicated that students perceived higher levels of BEEN than EMEN (see ). If teachers focus more on aspects of BEEN, students might perceive BEEN as more important as well, and they might feel more BEEN than EMEN. In addition, previous research has focused more on BEEN than on EMEN (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Hart, Stewart, & Jimerson, Citation2011). However, it is important for students to show EMEN and be motivated by school content, subjects or lessons rather than only obtaining high academic results and high grades. Previous research has indicated that EMEN is positively related to school connectedness, involvement, feeling accepted by teachers and peers, and a willingness to work and attend school (e.g., Appleton et al., Citation2006; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Jimerson et al., Citation2003; Libbey, Citation2004). Therefore, teachers should increase students’ EMEN, possibly through strategies to promote engagement in general, such as developing high-quality teacher-student relations (Fredricks, Citation2014; Taylor & Parsons, Citation2011), using collaborative learning (Wentzel, Citation2009), creating meaningful activities in school (Fredricks et al., Citation2004), providing support for student autonomy (Reeve, Jang, Carrell, Jeon, & Barch, Citation2004) and providing mastery-oriented learning environments rather than performance-oriented learning environments (Anderman & Patrick, Citation2012). However, previous research has revealed that teachers tend to focus more on monitoring activities than on promoting student EMEN (Eccles et al., Citation1993; Roland, Citation2012).

The data reveal that EMEN and BEEN are two separate constructs but are significantly associated at an individual level, indicating a correlation between these two measures. This finding is in line with previous research showing that SE consists of several interrelated subtypes (Fredricks et al., Citation2004) that might correlate or be a precondition for each other. Further, students might show BEEN and choose to work hard and do well in school without simultaneously showing EMEN in their schoolwork. This phenomenon supports previous research indicating that students do not have to show EMEN to do well academically (Wang & Peck, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2015). Taylor and Parsons (Citation2011) question whether students need to perceive belonging to school (EMEN) to be able to achieve high grades and to be successful academically. However, findings indicate that BEEN strongly predicts academic achievement (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Lee, Citation2014; Reyes et al., Citation2012).

Age, Gender and Student Engagement

The second part of the current study’s hypothesis was that younger students would show higher engagement than older students and that female students would show higher engagement than male students.

First, the findings indicated that SE is a greater challenge among lower secondary school students than among primary school students, supporting the hypothesis, which was based on previous studies. EMEN decreased dramatically from primary to lower secondary school, in accordance with previous research (e.g., Conner, Citation2016; Skinner et al., Citation2008; Wang et al., Citation2015). This finding could be explained by the fact that students have several teachers at higher school levels and therefore less time with each teacher, thus limiting the opportunities to build relationships between students and teachers (e.g., Conner, Citation2016). Teachers in lower secondary schools should therefore work harder to establish positive relationships with each student and use all opportunities to do so (e.g., Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering, Citation2003). Moreover, school systems are different in different countries; for example, Norwegian students have often the same teacher in the same subject for several years (levels 1–4, 5–7 and 8–10). When students have the same teacher for several years in one or more subjects, close relations between teachers and students might be easier to establish, which might influence SE. Thus, SE might present different challenges in different school systems.

Students should maintain their EMEN as they grow older and experience physiological and psychological changes because gradual disengagement might lead to academic failure, school dropout and truancy (e.g., Henry, Citation2007; Li & Lerner, Citation2011). The fact that SE declines as students age creates a challenge for scholars, researchers and politicians in preventing students’ negative psychosocial outcomes. However, despite declining SE, students might still be able to attain high levels of academic achievement (Wang et al., Citation2015), which indicates that there are other important factors in a student’s academic success in addition to the student’s feelings about school. However, students should be emotionally connected to school and actively participate in schoolwork to feel comfortable, be happy and socialize with peers at school. Schools should not only be places to perform, compete and strive for high scores on tests. This idea is related the goal-orientation theory, which implies that teachers and students are mastery or performance oriented. Students in classrooms that are mastery oriented are found to have, for example, higher SE in school subjects and lower degrees of anxiety (e.g., Harackiewicz, Barron, Pintrich, Elliot, & Thrash, Citation2002; Senko, Hulleman, & Harackiewicz, Citation2011). Thus, teachers should strive for mastery-oriented classrooms to create higher levels of SE. In addition, a strong association has been found between a mastery orientation and teachers’ emotional support (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2013). Moreover, the findings from one study indicate that students who reported high levels of teacher support also tended to report higher levels of mastery orientation; however, only emotional support was significantly associated with mastery orientation at all three grade levels included in that study (Lerang, Ertesvåg, & Havik, Citation2018). In addition, previous research consistently connects teachers’ emotional support with students’ motivation and engagement (e.g., Reyes et al., Citation2012; Roorda et al., Citation2011; Ruzek et al., Citation2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2013). Teachers’ emotional support is of particular importance in lower secondary school because students’ perceptions of teacher support decrease from primary to secondary school (e.g., Bokhorst et al., Citation2010; Bru et al., Citation2010; Malecki & Demaray, Citation2002).

Second, female students reported significantly greater BEEN than male students did, which supports the hypothesis and agrees with previous research (e.g., Covell, Citation2010; Furrer & Skinner, Citation2003; Pagani et al., Citation2012). The fact that female students are more engaged behaviorally could explain why female students have better grades than males in several countries (e.g., Freudenthaler, Spinath, & Neubauer, Citation2008). Female students do not necessarily enjoy school more than male students, but they might work and try harder and have goals of performing better academically than male students do. If female students do work harder, this effort could be related to female adolescents’ higher levels of subjective health complaints (SHC) as well as the association between SHC and stress from schoolwork and lower levels of self-esteem (Aanesen, Meland, & Torp, Citation2017). This topic is important, and teachers’ support is a protective and reducing factor for such complaints (e.g., Ghandour, Overpeck, Huang, Kogan, & Scheidt, Citation2004).

The higher levels of BEEN among female students could be explained by a school system that suits female students better than male students. This phenomenon may have several possible explanations, such as male students’ culture being less study oriented than female students’ culture (e.g., Van Houtte, Citation2004). This difference could also be related to the finding that female students report higher levels of relatedness than male students do (Furrer & Skinner, Citation2003). However, the findings from this previous study show that relatedness to teachers was a more salient predictor of engagement for male students.

Finally, the current findings also confirm that Norwegian students do not have very different perceptions than US students despite the differences in school context and that classroom interactions are an important contributor to SE in both countries. This finding indicates that regardless of the school context, culture or educational policy, classroom interaction is of great importance for SE. The strongest association was between teachers’ emotional support and EMEN, which is in line with previous studies in the US.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study suggest that teachers and educators should pay closer attention to high-quality interactions with all students, particularly lower secondary students, to enhance students’ EMEN and BEEN. To make this happen, teachers should focus on being sensitive, providing emotional support, organizing classrooms well and giving students sufficient instructional support (Pianta et al., Citation2008). The present study reveals that students would benefit from these activities, especially male students and students in lower secondary schools. Moreover, as young people struggle with their mental health some issues might be of even greater importance, such as positive school factors; reduced competition, comparisons and requirements; more supportive relations with teachers and peers; and a feeling of security, all of which are related to fewer subjective health problems (Tanaka, Terashima, Borres, & Thulesius, Citation2012). Further, students are exposed to different classrooms with higher- to lower-quality interactions. The findings indicate that classrooms should be developed to be high in emotional support to increase students’ EMEN.

Methodical Considerations/Limitations

The present study has several strengths. The survey captures students’ perceived SE and includes the two most common concepts of SE (Fredricks et al., Citation2004). Another strength is the use of multilevel analyses of classroom interactions from student surveys. Previous studies recommend the use of a two-level construct (e.g., Ertesvåg, Citation2016) because classroom interaction is considered a classroom-level phenomenon. Moreover, the design effect for EMEN indicates that this concept should be measured as a two-level construct.

Some limitations of the present study must be considered. Researchers often conceptualize SE as a multidimensional concept of emotional, behavioral and cognitive components; however, cognitive engagement was not included in the present study. Moreover, student self-reports capture students’ perception of all their teachers, and students’ answers might be an average of students’ perceptions of all their teachers (“you and your teachers”/“teachers and students”). However, we do not know whether all students thought of the average of their teachers when they answered the survey. Their answers might also depend on the strength of their emotions toward one specific teacher (positive or negative emotions) and on how many lessons per day/week they had with this particular teacher. SE varies across subjects (Archambault & Dupéré, Citation2017), and students experience substantial variations in EMEN depending on the learning context (Park et al., Citation2012). A student might be engaged in one lesson/subject but disengaged in another or with another teacher. The items in the current study consider only general SE and the average of students’ perceived engagement in class. The heading for these items (“What do you think about your motivation for schoolwork”) might therefore mask the variations in SE across different subjects/lessons/teachers, which might be a limitation of this study.

Moreover, the fact that students in Norway often have the same teacher in a specific subject for more than one year could influence SE. The current study did not include information about this aspect, but it should be taken into account in further research that considers classroom interactions and SE.

Because this was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to determine a cause-effect relationship; instead, we identified only associations between independent and dependent variables where SE was the dependent variable.

According a literature review, factors such as parents and peers can influence SE (e.g., Hancock & Zubrick, Citation2015; You & Sharkey, Citation2009). Parents and peers were not included in the current study, which might be a limitation. However, the students’ perceived SES was included as a control variable because SES is associated with SE (e.g., Finn, Citation1989; Finn & Cox, Citation1992). Finally, students’ self-reports were the only source to measure classroom interactions. It has been questioned whether students can be a reliable source of information on teacher behavior (e.g., Fauth, Decristan, Rieser, Klieme, & Buttner, Citation2014; Kunter & Baumert, Citation2007). Findings from a study by Ertesvåg and Havik (Citation2018) indicated that students are able to differentiate between aspects of classroom interaction. However, to provide greater richness of information on classroom interaction, teacher self-reports and classroom observations may provide important insight into this field.

Conclusion

The results of the current study contribute to the understanding of the importance of high-quality classroom interactions in SE, particularly the importance of emotionally supportive teachers in students’ EMEN. Further, the findings indicate that in classrooms with emotionally supportive teachers, students show more EMEN. The findings suggest that educators should pay attention to how to enhance SE, particularly for male students and early adolescents. Positive teacher-student interactions are a fundamental aspect of quality teaching, learning and SE. Schools and teachers should show “pedagogical caring” (Wentzel, Citation1997) because the quality of classroom interactions is important for SE and for students’ academic and social development. Moreover, the fact that EMEN was perceived to be low in the current study indicates a need for research in this field, particularly to examine the challenge of declining EMEN as students age, which is in line with previous research (e.g., Conner, Citation2016; Eccles & Roeser, Citation2010, Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2008; Wang et al., Citation2015). It is important to note how particular lower secondary schools focus on performance and test results and how this focus might affect different aspects of SE, particularly EMEN. Students might perform well despite negative feelings toward school and schoolwork. Students’ emotions and satisfaction toward their school and schoolwork should be considered important because gradual disengagement might lead to academic failure, school dropout and truancy (e.g., Henry, Citation2007; Li & Lerner, Citation2011). PISA indicators of SE among students at the age of 15 show the importance of EMEN; Norwegian students’ attitudes toward school and sense of belonging decreased from 2003 to 2012 (OECD, Citation2013). Despite this, the same report showed that students arrived at school more punctually during the same period. Moreover, they skipped class or days of school less often than the average student in OECD countries. All students should be satisfied with school and feel a sense of belonging at school, and teachers play an important role through their interactions with students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aanesen, F., Meland, A., & Torp, S. (2017). Gender differences in subjective health complaints in adolescence: The roles of self-esteem, stress from schoolwork and body dissatisfaction. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 45(4), 389–396. doi: 10.1177/1403494817690940

- Allen, J. P., Gregory, A., Mikami, A., Lun, J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Observations of effective teacher-student interactions in secondary school classrooms: Predicting student achievement with the classroom assessment scoring system-secondary. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 76–98.

- Allen, J. P., Pianta, R. C., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., & Lun, J. (2011). An interaction-based approach to enhancing secondary school instruction and student achievement. Science ( New York, NY), 333(6045), 1034–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.1207998

- Anderman, E. M., & Patrick, H. (2012). Achievement goal theory, conceptualization of ability/intelligence, and classroom climate. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 173–191). New York, NY: Springer.

- Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 427–445. doi:10.1016/j.jsp. 2006.04.002

- Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2017). Joint trajectories of behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in elementary school. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(2), 188–198. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2015.1060931

- Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. (2009). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. Journal of School Health, 79, 408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

- Barkatsas, A., Kasimatis, K., & Gialamas, V. (2009). Learning secondary mathematics with technology: Exploring the complex interrelationship between students’ attitudes, engagement, gender and achievement. Computers & Education, 52(3), 562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.11.001

- Blossing, U., Imsen, G., & Moos, L. (2014). The nordic education model. “A school for all” encounters neo-liberal policy, policy implications of research in education. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10 1007/978-94-007-7125-3_

- Bokhorst, C. L., Sumter, S. R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2010). Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: Who is perceived as most supportive? Social Development, 19(2), 417–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00540.x

- Bru, E., Boyesen, M., Munthe, E., & Roland, E. (1998). Perceived social support at school and emotional and musculoskeletal complaints among Norwegian 8th grade students. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 42(4), 339–356. doi: 10.1080/0031383980420402

- Bru, E., Stornes, T., Munthe, E., & Thuen, E. (2010). Students’ perceptions of teacher support across the transition from primary to secondary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(6), 519–533. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2010.522842

- Bryson, C., Cooper, G., & Hardy, C. (2010, December 14–16). Reaching a common understanding of the meaning of student engagement. Paper presented at Society of Research into Higher Education Conference, Wales.

- Chapman, E. (2003). Alternative approaches to assessing student engagement rates. Practical Assessment, 8(13), 1–7. Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=8&n=13

- Chen, J. J.-L. (2005). Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to Hong Kong adolescents’ academic achievement: The mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(2), 77–127. doi: 10.3200/MONO.131.2.77-127

- Conner, T. (2016). Relationships: The key to student engagement. International Journal of Education and Learning, 5(1), 13–22. doi: 10.14257/ijel.2016.5.1.02

- Conner, J. O., & Pope, D. C. (2013). Not just robo-students: Why full engagement matters and how schools can promote it. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(9), 1426–1442. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9948-y

- Covell, K. (2010). School engagement and rights-respecting schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(1), 39–51. doi: 10.1080/03057640903567021

- Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M. K., & Elder, G. H. (2004). School size and the interpersonal side of education: An examination of race/ethnicity and organizational context. Social Science Quarterly, 85(5), 1259–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00275.x

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2010). An ecological view of schools and development. In J. L. Meece & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 6–22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

- Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Midgley, C., Reuman, D., Iver, D. M., & Feldlaufer, H. (1993). Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. The Elementary School Journal, 93(5), 553–574. doi: 10.1086/461740

- Emmer, E. T., & Stough, L. M. (2001). Classroom management: A critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educational Psychologist, 36(2), 103–112. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3602_5

- Ertesvåg, S. K. (2009). Classroom leadership: The effect of a school development programme. Educational Psychology, 29(5), 515–539. doi: 10.1080/01443410903122194

- Ertesvåg, S. K. (2016). Students who bully and their perception of teacher support and monitoring. British Educational Research Journal, 42(5), 826–850. doi: 10.1002/ber.3240

- Ertesvåg, S. K., & Havik, T. (2018). Student perceived classroom interaction and mental health problems and proactive aggression. Submitted manuscript for publication.

- Fauth, B., Decristan, J., Rieser, S., Klieme, E., & Buttner, G. (2014). Student ratings of teaching quality in primary school: Dimensions and prediction of student outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 29, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.07.001

- Federici, R. A., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2014). Students’ perception of instrumental support and effort in mathematics: The mediating role of subjective task values. Social Psychology of Education, 17(3), 527–540. doi: 10.1007/s11218-014-9264-8

- Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117–142. doi:10.3102/ 00346543059002117

- Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

- Finn, J. D., & Cox, D. (1992). Participation and withdrawal among fourth-grade pupils. American Educational Research Journal, 29(1), 141–162. doi: 10.3102/00028312029001141

- Finn, J. D., & Rock, D. A. (1997). Academic success among students at risk for school failure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 221–234. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.221

- Finn, J. D., & Voelkl, K. E. (1993). School characteristics related to student engagement. The Journal of Negro Education, 62(3), 249–268. doi: 10.2307/2295464

- Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 97–131). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Fredricks, J. A. (2014). Eight myths of student disengagement: Creating classrooms of deep learning. Los Angeles: Corwin.

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept: State of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

- Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763–782). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Freudenthaler, H. H., Spinath, B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2008). Predicting school achievement in boys and girls. European Journal of Personality, 22, 231–245. doi: 10.1002/per.678

- Furlong, M. J., Whipple, A. D., St. Jean, G., Simental, J., Soliz, A., & Punthuna, S. (2003). Multiple contexts of school engagement: Moving toward a unifying framework for educational research and practice. The California School Psychologist, 8(1), 99–113. doi: 10.1007/BF03340899

- Furrer, C. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 148–162. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148

- Furrer, C. J., Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2014). The influence of teacher and peer relationships on students’ classroom engagement and everyday motivational resilience. National Society for the Study of Education, 113(1), 101–123.

- Ghandour, R. M., Overpeck, M. D., Huang, Z. J., Kogan, M. D., & Scheidt, P. C. (2004). Headache, stomachache, backache, and morning fatigue among adolescent girls in the United States associations with behavioral, sociodemographic, and environmental factors. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 797–803. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.797

- Gustafsson, J.-E., & Nielsen, T. (2016). Final remarks. In T. Nilsen & J.-E. Gustafsson (Eds.), Teacher quality, instructional quality and student outcomes: Relationships across countries, cohorts and time (Vol. 2, pp. 135–147). IEA Research for Education. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

- Haapasalo, I., Välimaa, R., & Kannas, L. (2010). How comprehensive school students perceive their psychosocial school environment. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(2), 133–150. doi: 10.1080/00313831003637915

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967.

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. C. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. L. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (Vol. 11, pp. 49–83). Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., … Hamagami, A. (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113(4), 461–487.

- Hancock, K. J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school. Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA. ISBN: 978-1-74052-337-0.

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Pintrich, P. R., Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Revision of achievement goal theory: Necessary and illuminating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 638–645. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.3

- Hart, S. R., Stewart, K., & Jimerson, S. R. (2011). The student engagement in schools questionnaire (SESQ) and the teacher engagement report form-new (TERF-N): Examining the preliminary evidence. Contemporary School Psychology, 15(1), 67–79. doi: 10.1007/BF03340964

- Havik, T. (2017). Bullying victims’ perceptions of classroom interaction. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice, 28(3), 350–373. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2017.1294609

- Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal- and truancy-related reasons for school non-attendance. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 221–240. doi: 10.1007/s11218-015-9293-y

- Henry, K. L. (2007). Who’s skipping school: Characteristics of truants in 8th and 10th grade. Journal of School Health, 77, 29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00159.x

- Howes, C., Pianta, R. C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R. M., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood. Research Quarterly, 23, 27–50.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hughes, J. N. (2002). Authoritative teaching: Tipping the balance in favor of school versus peer effects. Journal of School Psychology, 40, 485–492. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4405(02)00125-5

- Hughes, J. N., & Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student-teacher and student-peer relatedness: Effects on academic self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.03.005

- Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement Trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 21–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x

- Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., & Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. Contemporary School Psychology, 8(1), 7–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03340893

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1993). Testing structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation modeling (pp. 294–316). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74, 262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x

- Klette, K., Sahlström, F., Blikstad-Balas, M., Luoto, J., Tanner, M., Tengberg, M., … Slotte, A. (2018). Justice through participation: Student engagement in Nordic classrooms. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 57–77. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2018.1428036

- Kortering, L. J., & Christenson, S. (2009). Engaging students in school and learning: The real deal for school completion. Journal Exceptionality. A Special Education Journal, 17(1), 5–15. doi: 10.1080/09362830802590102

- Kunter, M., & Baumert, J. (2007). Who is the expert? Construct and criteria validity of students and teacher ratings of instruction. Learning Environments Research, 9, 231–251. doi: 10.1007/s10984-006-9015-7

- La Paro, K. M., Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. (2004). The classroom assessment scoring system: Findings from the prekindergarten year. The Elementary School Journal, 104(5), 409–426. doi: 10.1086/499760

- Ladd, G. W., & Dinella, L. M. (2009). Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children's achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 190–206. doi: 10.1037/a0013153

- Lee, J.-S. (2012). The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.006

- Lee, J.-S. (2014). The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: Is it a myth or reality? The Journal of Educational Research, 107(3), 177–185. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2013.807491

- Lerang, M. S., Ertesvåg, S. K., & Havik, T. (2018). Classroom interaction, goal orientation and their association with social and academic learning outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. ISSN 0031-3831. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2018.1466358

- Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency & substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233–247. doi: 10.1037/a0021307

- Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08284.x

- Loukas, A., & Murphy, J. L. (2007). Middle school student perceptions of school climate: Examining protective functions on subsequent adjustment problems. Journal of School Psychology, 45(3), 293–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.10.001

- Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychology in the Schools, 39(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1002/pits.10004

- Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. doi: 10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

- Marks, H. M. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 153–184. doi: 10.3102/00028312037001153

- Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Miller, R. B., Greene, B. A., Montalvo, G. P., Ravindran, B., & Nichols, J. D. (1996). Engagement in academic work: The role of learning goals, future consequences, pleasing others, and perceived ability. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21(4), 388–422. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1996.0028

- Murray, C., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). The importance of teacher-student relationships for adolescents with high incidence disabilities. Theory Into Practice, 46(2), 105–112. doi: 10.1080/00405840701232943

- Muthén, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology, 25, 267–316. doi: 10.2307/271070

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- NCES. (2014). The condition of education 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

- Norusis, M. (2011). Outlines & highlights for SPSS 17.0 statistical procedures companion. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 results: Ready to learn: Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs ( Vol. III). PISA, OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264201170-en

- OECD. (2015). PISA 2015 results. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/

- Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367. doi: 10.3102/00346543070003323

- Pagani, L. S., Fitzpatrick, C., & Parent, S. (2012). Developmental pathways of classroom engagement in elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 715–725. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9605-4

- Park, S., Holloway, S. D., Arendtsz, A., Bempechat, J., & Li, J. (2012). What makes students engaged in learning? A time-use study of within- and between-individual predictors of emotional engagement in low-performing high schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(3), 390–401. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9738-3

- Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M., & Kaplan, A. (2007). Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 83–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83

- Pianta, R. C. (2016). Student interactions: Measurement, impacts, improvement, and policy. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 98–105. doi:10.1177/2372732215622457

- Pianta, R. C., Belsky, J., Houts, R., Morrison, F., & The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2007). Opportunities to learn in America’s elementary classrooms. Science, 315, 1795–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1139719

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Allen, J. P. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement (pp. 365–386). New York: Springer Nature.

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Mintz, S. (2012). Classroom assessment scoring system –secondary. Charlottesville, VA: Teachstone.

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system™: manual K-3. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). Students’ emotional and cognitive engagement as the determinants of well-being and achievement in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 67, 40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2014.05.001

- Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669434

- Reddy, R., Rhodes, J. E., & Mulhall, P. (2003). The influence of teacher support on student adjustment in the middle school years: A latent growth curve study. Development and Psychopathology, 15(1), 119–138. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000075

- Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147–169. doi: 10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

- Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2012). Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 3–19). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 700–712. doi: 10.1037/a0027268

- Roland, P. (2012). Thesis: Implementation of the school development program respect ( Avhandling: Implementering av skoleutviklingsprogrammet Respekt). University of Stavanger. ISBN 978-82-7644-486-5.

- Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

- Ruzek, E. A., Hafen, C. A., Allen, J. P., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., & Pianta, R. C. (2016). How teacher emotional support motivates students: The mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learning and Instruction, 42, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004

- Senko, C., Hulleman, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2011). Achievement goal theory at the crossroads: Old controversies, current challenges, and new directions. Educational Psychologist, 46, 26–47. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.538646

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2013). School goal structure: Associations with students’ perceptions of their teachers as emotionally supportive, academic self-concept, intrinsic motivation, effort, and help seeking behavior. International Journal of Educational Research, 61, 5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2013.03.007

- Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effect of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 571–581. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

- Skinner, E. A., Furrer, C. J., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 765–781. doi: 10.1037/a0012840

- Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

- Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher–student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23(4), 457–477. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y