?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

While individual and family factors behind students’ school absenteeism are well-researched, fewer studies have addressed school climate factors. This study investigated the association between school climate in Swedish schools and students’ absenteeism. A multi-informant survey of school climate was conducted in 101 schools and analysed in relation to the history of absenteeism of 2770 students attending those schools in the 7th grade at inception, with follow-up until completion of the compulsory school (9th grade). Data on absenteeism was extracted from schools’ registers. Student (but not teacher) positive ratings of school climate were associated with lower absenteeism between the age of 13 and the age of 16. The associations between student rated school climate and absenteeism appeared stronger among students with highly educated parents.

Attending school is important for children’s academic, social and personal development (Kearney & Graczyk, Citation2014). The short- and long-term consequences of absenteeism can be detrimental, including poor school performance (London et al., Citation2016; Silverman, Citation2012), school dropout (Kearney, Citation2008), mental health problems (Kearney & Albano, Citation2004), and later unemployment (Rocque et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to identify and address the factors and conditions that play a role in school absenteeism.

The factors increasing the risk of absenteeism can be divided into three categories: individual-, family and school-related factors (Daraganova et al., Citation2014; Kearney, Citation2008). Individual factors encompass mental health problems (Garvik et al., Citation2014; Skedgell & Kearney, Citation2016), and aggressive behaviour, rule-breaking behaviour, hyperactivity and inattention (Skedgell & Kearney, Citation2016) as well as learning difficulties (Chen et al., Citation2016; Maynard et al., Citation2018). Family-related factors include parental involvement, parental psychopathology, family conflicts and separation (Thornton et al., Citation2013). While individual and family factors behind absence have been extensively investigated (see Ek & Eriksson, Citation2013 for a review), fewer studies have addressed school-level factors, such as the quality of school climate (Hendron & Kearney, Citation2016).

Absenteeism – Authorized or Unauthorized

A variety of definitions have been used to characterize school absenteeism (Kearney et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b). In schools, absenteeism is divided into authorized and unauthorized, the latter being a major concern for educators (Kearney, Citation2008). An authorized absence is allowed by parents and/or school and may be due to illness, holidays, family emergencies or school suspension. In contrast, unauthorized absences include a broad range of behaviours like school refusal, truancy, or unexplained absences (Hancock et al., Citation2017; Kearney, Citation2008). Unauthorized absences are typically classed as such by school administration policies and can include both parent-endorsed absences (e.g., an unauthorized family vacation) and absences not endorsed by parents (e.g., truancy).

Furthermore, a distinction has been made between school refusal, caused by negative emotions related to school, and truancy, explained by lack of motivation to attend school (Havik et al., Citation2015), and these two behaviours are likely to be predicted by different factors. Obviously, within a given period of time, students can experience multiple types of absences (Hancock, Citation2019) for example, truant students can be on sick leave or other authorized absences in addition to unauthorized absences.

An important dimension of unauthorized absenteeism is its duration (Kearney et al., Citation2019a). Unauthorized absence encompasses more than 25% of school days during a period of two weeks or 10 days; or 15% during a period of 15 weeks of a school year (Havik et al., Citation2015; Kearney, Citation2008; Skedgell & Kearney, Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2013). However, different cut-off points for problematic unauthorized absence have been presented, ranging from >3 days during a past month (Virtanen et al., Citation2009) to >20 days in the past 90 days, also denoted as chronic absenteeism (Balfanz & Byrnes, Citation2012; Berman et al., Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2013; Van Eck et al., Citation2017). When the association between unauthorized absence and standardized performance test results has been studied, even small amounts of unauthorized absence have been found to be associated with lower test results (Hancock et al., Citation2017). Therefore, even low cut-off points can be used to represent problematic levels of unauthorized absence.

School Climate

School climate refers to how school personnel, students and parents experience school life, from academical, social, ethical, and emotional viewpoints (Thapa et al., Citation2013). Four major domains of school climate have been identified in previous research (a) academic environment, (b) social environment, including relationships with peers and sense of connectedness to school, (c) safety, and (d) institutional environment (Thapa et al., Citation2013; Wang & Degol, Citation2016). Academic school climate includes curricula, teaching and learning, and teachers’ professional development. Social climate concerns the quality of interactions among school personnel and students, including sense of connectedness to school. Safety concerns physical and emotional security at school, including order and discipline. Finally, institutional environment refers to infrastructural factors such as, teacher resources, technology, school building, and class size (Thapa et al., Citation2013; Uline & Tschannen-Moran, Citation2008).

Previous research on school climate and student absenteeism (both authorized and unauthorized) demonstrated an inverse association, i.e., more positive climate was associated to lower absenteeism (Berman et al., Citation2018; Brookmeyer et al., Citation2006; Hendron & Kearney, Citation2016; Van Eck et al., Citation2017; Virtanen et al., Citation2009). These studies have focused particularly on the social environment of schools, including peer relations and teacher-student relations, perceptions of safety and school as physical environment (Berman et al., Citation2018; Demir & Akman Karabeyoglu, Citation2015; Hendron & Kearney, Citation2016; Ramberg et al., Citation2019; Virtanen et al., Citation2009). A factor that stands out as important in all these studies, is the quality of relationships between teachers and students. For instance, Demir and Akman Karabeyoglu (Citation2015) found that the teacher-student relationship affected the students’ commitment to school, a variable explaining 22% of the variance in absenteeism in their study.

School academic environment, as teaching activities or teacher expectations, have been given scarce attention in previous research. Van Eck et al. (Citation2017) included in school climate students’ perceptions of learning environment, including teacher expectations and orderliness of the environment. The authors concluded that overall negative ratings of school climate were strongly associated with absenteeism but did not study learning environment as a separate factor. Teachers’ poor classroom management is another factor associated with absenteeism (Havik et al., Citation2015). Dislike of a lesson or teacher have been reported as reasons for unauthorized absenteeism from school (Attwood & Croll, Citation2006). Given the reciprocal relationship between academic failure and students’ unauthorized absenteeism (Chen et al., Citation2016; London et al., Citation2016; Maynard et al., Citation2018; Silverman, Citation2012), there is a need to study the unique contribution of different dimensions of school academic environment. In addition to lack of studies on academic dimensions of school climate, previous studies had several methodological limitations.

For instance, few studies have provided multi-informant ratings of school climate. Most of the studies have relied on either teachers’ (Berman et al., Citation2018; Ramberg et al., Citation2019) or students’ ratings of school climate (Brookmeyer et al., Citation2006; Havik et al., Citation2015; Hendron & Kearney, Citation2016; Van Eck et al., Citation2017; Virtanen et al., Citation2009). According to Wang and Degol (Citation2016), school climate is a multidimensional construct and there is a need for multi-informant studies. For instance, teachers tend to rate school climate more positively than students (Dernowska, Citation2017; Mitchell et al., Citation2010), probably due to their different roles. While teachers may rate school climate according to a comprehensive overview of classroom and school activities, students are more focused on their recent individual experiences. Despite the need to consider informants’ perspectives, in Wang and Degol’s (Citation2016) review few studies accrued information from students, teachers and parents. With the exception of Brookmeyer et al. (Citation2006) previous studies used a cross-sectional one-point measurements of school climate, despite the need for multiple measurements, recommended by Wang and Degol (Citation2016).

In addition, school climate can be measured as a school-level or an individual-level variable. Measuring school climate using individual students’ perspectives posits that of the experience of school climate will differ for every informant in a school and that this difference is highly informative (Van Horn, Citation2003). On the other hand, measuring school climate as school-level variable by aggregating individual ratings within a school, assumes that climate is a property of the school itself, therefore its different impact on individuals does not depends on its measurement (Fan et al., Citation2011). Both types of approaches entail limitations. Individual-level measurements, on the one hand, may contain errors attributed to lack of knowledge, experience or bias in individuals’ responses. School-level measurements, on the other hand, may fail to consider individual perceptions of school climate.

Common Factors Associated with School Climate and Absenteeism

Common or co-occurring factors identified as important to both school climate and absenteeism are several. For example, parent’s with high educational level, as well as parents’ employment and high income have been linked to lower absenteeism (Balkis et al., Citation2016; Thornton et al., Citation2013). These demographic characteristics may in turn have a bearing on which school a child will attend, thereafter the exposure to a particular school climate. The same can be hypothesized concerning ethnic or geographical origin of the family, as being a member of an ethnic minority, in some countries, has been associated with greater absenteeism and lower educational attainment (Skedgell & Kearney, Citation2018).

In studies in the United States (U.S.) and Australian context, students at schools situated in areas characterized by poverty and neighbourhood crime were also reported to be more likely to be absent from school (Berman et al., Citation2018; Hancock et al., Citation2017). In the Swedish context, the difference between independent and municipal schools must be considered. Independent (privately run) schools are usually smaller in size than municipal schools and may have larger proportions of students with high socioeconomic status and students’ parents are likely to have high educational attainment (Giota et al., Citation2019). Among schools in Stockholm, higher ratings of school ethos (school norms, values and beliefs) were also related to lower absenteeism (Ramberg et al., Citation2019).

Absenteeism in Swedish Schools

In Sweden, compulsory school education comprises nine years between the age of seven and 16 years of age. Since the introduction of “free school choice” legislation in 1992, the Swedish school system has become decentralized with many independent schools. Independent schools are required to follow the same national policies and regulations as municipal schools (Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE], Citation2019).

According to surveys by SNAE (Citation2010) and the Swedish School Inspectorate (SSI, Citation2016) less than 1% of the students in compulsory school had been absent for more than one month. The presence of long-term absence was twice as high in the secondary school compared to primary and middle school. Approximately 2% of the students were repeatedly absent, defined as absence from single lessons or days exceeding 5% of teaching time, over a period of at least two months. In July 2018, a law amendment to reduce unauthorized absences was introduced, urging school leaders to immediately start an inquiry of the reasons for students’ absences (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2010, 800).

The Current Study

This study aims to investigate the association between the school climate in the Swedish schools and adolescent students’ absenteeism. It is anticipated that (a) positive school climate and specifically its pedagogical dimensions such as teachers support and positive expectations, are associated with less unauthorized absenteeism among students aged 13–16 years (i.e., the last block of compulsory education); (b) the association between school climate and unauthorized absenteeism is moderated by factors such as school management, parental education, or parental ethnic background.

Method

Participants

This study is part of a large longitudinal study (Galanti et al., Citation2016), set up to examine the association between school climate and students’ mental health. The longitudinal sample included students in 7th grade at the study start (about 13 years of age) attending schools located in central Sweden. Informed consent from students’ guardians was obtained prior to data collection and students received detailed information on the study (Galanti et al., Citation2016). The study was approved by a regional Swedish Ethical Review Board (reference numbers: 2012/1904-31/1 and 2016/1280-32).

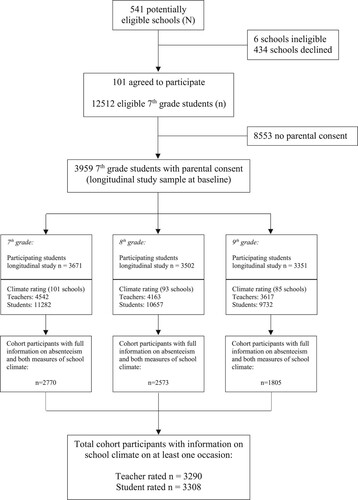

The recruitment of schools and students for the longitudinal study was conducted during two subsequent school years (2013–2014 and 2014–2015). Both independent and municipal schools in the selected regions with at least 20 students in each grade 7 to 9 were eligible. Out of 535 eligible schools, 101 (19%) agreed to participate. Students were potentially eligible if they could read and write in the Swedish language, (i.e., students with a history of immigration to Sweden during the previous year did not participate in the study). Intellectual disability was an exclusion criterion. In all, 3,959 students were recruited as participants in 7th grade. Two follow-up surveys were conducted (in 8th and 9th grade).

The longitudinal sample in the present study (also referred to as “the cohort”, see for its derivation) included only students for whom data on school climate and unauthorized absence from school was available (n = 2770) at baseline in 7th grade (70% of those initially recruited), 2573 in the 8th grade (65%) and 1805 in the 9th grade (46%). Students who emigrated from the participating schools were excluded because of lack of information on school climate in the corresponding year, but were retained for the years they actually attended any of the participating schools.

Measures

School Climate

The instrument used to describe school climate was the Pedagogical and Social Climate Questionnaire (PESOC; Grosin, Citation2004), which aims to capture the social interaction between different groups as well as the interaction between structural and cultural factors in school, largely in accordance with the conceptualization of school ethos outlined by Rutter et al. (Citation1979) and Rutter and Maughan (Citation2002). The PESOC encompasses separate versions for teachers and students, described in detail below. Both versions cover dimensions of school climate concerning (a) order, safety and discipline, (b) teaching and learning, (c) social relationships, (d) shared parent- and teacher norms and (e) quality of school facilities.

Teacher Version

The PESOC teacher version (T-PESOC) includes 67 items grouped according to 13 dimensions (subscales) labelled as TE = Teachers expectations for students’ behaviour and academic performance, PTA = Perceived teacher agreement about school goals, norms, and rules, SF = Student focus, BA = Basic assumptions about students’ ability to learn, HOME = Communication between school and home, TC = teacher interaction and cooperation, TPD = teachers’ confidence and professional development, TA = Teaching activities, EV = Evaluation of students’ academic progress, P = Principal’s pedagogical leadership, SM = Teachers’ perception the school management’s involvement and support of teachers.. The reliability and validity of the instrument have been investigated by Hultin and colleagues (Hultin et al., Citation2018), to which we refer for further details. The model-based composite reliabilities for PESOC subscale scores, as indexed by Raykov’s rho (Raykov, Citation2012) ranged from .69 to .94. The multi-level confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) indicated that a two-factor model at the teacher level and a one-factor model at the school level provided the best fit. The second factor in the model (labelled as “Pedagogical activities and social relationships”), included the three subscales explored in this study (Hultin et al., Citation2018).

Items in the teacher instrument are formulated as statements with four response options on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 Not at All to 4 Completely Agree. A response option Don’t Know is also included. Items scores are averaged into a total scale as well as subscale scores, with the don’t know response treated as missing.

In this study, we used the total score of T-PESOC and three subscales as predictors of absenteeism, specifically focusing on the academic school climate. The subscale Teacher Expectations (TE) includes four items about the staffs’ and principals demands for academic results and staff’s endorsements about all students being able to reach the curriculum goals (Raykov’s ρ = .69). The subscale Basic Assumptions (BA) includes three items about the importance of the quality of the teaching, the importance of setting knowledge goals and the belief that all students can learn what is required of them (Raykov’s ρ = .75). The subscale Teaching Activities (TA) includes six items about teachers’ practice to improve their pedagogic performance, teachers’ possibility to use the time for teaching, and again the belief that all students can gain basic knowledge and skills (Raykov’s ρ = .74).

In this study teacher ratings on the pedagogical and social climate were reported for each school year in the participating schools, by 4542 teachers in 101 schools (100% of the enrolled schools) at the first assessment in the 7th grade, and by 3617 teachers in 81 schools (80% of the originally enrolled schools) at the third assessment in grade 9 ().

Student Version

The PESOC version for students (S-PESOC) consists of 53 items grouped according to 8 dimensions (sub-scales), labelled Expectations (E, four items); Perception of Teacher Norms (P, 12 items); Teachers’ Support (TS, five items); Teaching Activities (TA, 15 items); Student Participation (SP, three items); School Environment (SE, three items); School and Home (SH, five items); School Management (SM, six items).

The psychometric properties of the instrument have been previously reported, based on the same sample of schools recruited for this study (Hultin et al., Citation2019). We refer to this publication for details (e.g., single items, subscale content and properties). In brief, a series of multi-level confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) was performed, yielding a best fit and most parsimonious specification for a model containing one factor at the school level and 8 factors (corresponding to the 8 subscales) at the student level, (Hultin et al., Citation2019). Reliability was assessed as multilevel composite reliability estimates (ω; Geldhof et al., Citation2014) based on model factors identified in the MCFA. Estimates ranged from .68 and .91 for the student level factors, while the estimate was .98 for the unique climate factor at the school level.

In this study, item and scale scores were derived as described for the teacher version. The total scale score of S-PESOC and three subscales, chosen to specifically address the academic school climate, were used to predict absenteeism. The subscale Expectations includes four items about perceived teachers’ expectations for students’ academic results. The subscale Teacher Support includes five items about teachers’ attention and support to the students, both in the classroom and outside. The subscale Teaching Activities includes 15 questions about the teachers’ ability to make learning goals interesting and motivating.

Each year the questionnaire was administrated to and potentially answered by all students attending grade 9 (final year of the compulsory school in Sweden) in the participating schools, because these students were considered most reliable informants, having in most cases attended the school for 3 years. Thus, in this study students rating the school climate were not coinciding with participants in the longitudinal sample, apart (partially) at the last assessment.

Student ratings on the pedagogical and social climate was reported for each school year in the participating schools, by 11282 students in 100% of the 101 enrolled schools at the first assessment in the 7th grade and by 9732 students in 85 schools (84% of the enrolled) at the final assessment in the 9th grade ().

Absenteeism

Data concerning authorized and unauthorized absences were obtained from individual school records. Absenteeism in this study was defined as missing more than 2% of the school year due to unauthorized absences (approximately four full days of unauthorized absence across the academic year). Using this definition, absenteeism concerned 7.6%, 10.5% and 10.3% of students in grades 7, 8 and 9 respectively.

Covariates

Because of the a-priori reasons elucidated in the introduction, we considered parental education and birthplace, self- reported by the parents of the index students at baseline as potential individual-level confounders, as well as effect modifiers of the association of interest. Parents’ educational level was dichotomized into “High parental education” (yes/no) if at least one parent had attended university for at least three years. Parental birthplace was categorized as “Both parents born in Sweden” vs. “Either parent born outside Sweden”. School management (municipal or independent) was considered as school-level confounder as well as school-level modifier. Mental health problems of the participants were primarily assessed through the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman et al., Citation2000).

Statistical Analysis

T-PESOC and S-PESOC scores for the full scale and for the chosen sub-scales were analysed in quartiles of the respective distributions in the measurement performed at the cohort inception (cut-offs provided in ). This was done in order to keep a time-invariant categorization. For pedagogic purposes, the lowest quartile was labelled as “Poor climate” and the highest quartile as “Good climate”.

Table 1. Mean and quartile distribution of the school climate score (PESOC), at the cohort inception in 7th grade.

The scores quartiles were used as independent variables in the analysis. Registered unauthorized hours of absenteeism was used as the dependent variable, dichotomized above 16 h (over 2% of school time) versus less than 16 (less or equal to 2%). This categorization was used because the range of absenteeism in this sample was rather skewed towards low values, thus the cut-off point was determined based on the distribution of the data to enable efficient and reliable statistical analyses, after Hancock et al. (Citation2017).

First, we compared unauthorized absenteeism in grade 7–9 across baseline characteristics of the study sample (parental education, parental birthplace, student’s gender) and school management (), as well as across categories of the scales scores (). The chi-square test was used to explore the departure of the observed from the expected proportions. Mixed model logistic regression was employed to model the association between independent and dependent variables, with two level random effects to accommodate for clustering of data within subjects (repeated measurements during three years) and within schools. The following equation was used in the modelling, where i refers to the individual, j to the school and t to the assessment (grade 7, 8 or 9), while U and W are the two random intercepts

Table 2. Proportions of students with unauthorized absenteeism across socio-demographic and school characteristics.

Table 3. Proportions of students with unauthorized absenteeism in relationship to school climate.

The intra class correlations (ICC) for both random effects were calculated within the empty model. The school level ICC was .20 and the individual level ICC was .60, i.e., a strong indication that both levels contributed to the total variance and that none should be dropped. Results were expressed as cross-sectional odds ratios (OR) of absenteeism for each lower quartile of climate score compared to the highest, together with their corresponding 95% confidence limits (CI) averaged across three years. In this analysis, each individual in the cohort contributed observations until retained at follow-up, i.e., until attending one of the schools enrolled in the study.

Adjustments were made for parents’ educational level, parents’ country of origin, and school management. These variables were all used as binary indicators in the models. Furthermore, to test for possible effect modification of gender, parents’ educational level, parents’ country of origin or school management we conducted separate models for each of these categories. Individuals included in these analyses were those with at least one data point with full information on all variables. This listwise deletions resulted in slightly different samples in the adjusted analyses. In order to explore the robustness of the results we conducted a sensitivity analysis through multiple imputation (Azur et al., Citation2011). In order to accommodate for the presence of potential confounding due to mental health problems we repeated the analysis after exclusions of students who in any given year reported high score for the SDQ scale, according to the internationally agreed cut-off for the age (Goodman et al., Citation2000). Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and Stata 14.2.

Results

The distribution of the school climate scores (PESOC total score and relevant sub-scales) is reported in for the year relative to the cohort recruitment, separately from teachers’ and students’ ratings. The range of climate scores was small, with very little difference between the lowest and the highest quartiles (See ). However, both teachers’ and students’ ratings increased over time, being lowest at the first assessment (cohort inception) and highest at the last assessment, corresponding to participants attending the 9th grade (not shown).

provides the proportions of students with unauthorized absenteeism in each grade, across socio-demographic and school characteristics. The proportion absentees did not differ by gender. At all time-points, the proportion of absentees was lower among students whose parents achieved a university education and/or were both Swedish-born than among those whose neither parent attended university or at least one parent was not born in Sweden. Unauthorized absenteeism was more frequent among students who attended municipal schools than among those attending independent schools, particularly in the 9th grade.

provides the proportions of students with unauthorized absenteeism in relationship to school climate. Except for the sub-scale “Expectation” in the teacher rating, the proportions of absentees were higher in the lowest quartile of climate (poor climate) than in the highest quartile (good climate), but there was no clear or consistent gradient across score quartiles.

In , the cross-sectional odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% Confidence intervals (CI) of unauthorized absenteeism are presented, averaged across all three years at high school. Thus, this approach is based on multiple observations obtained from all participants.

Table 4. Cross sectional odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of unauthorized absenteeism in grades 7–9 according to quartiles of school climate scores.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors there was no clear or consistent pattern in the association between teacher ratings of school climate (T-PESOC) and unauthorized absenteeism (See ).

Using student ratings of school climate, there were consistent patterns of associations with unauthorized absenteeism in the predicted direction (better climate associated with lower likelihood of unauthorized absenteeism), although the estimates not always attained statistical significance (See ). The analysis of subscales revealed that students’ perceptions of teachers’ expectations was the dimension that contributed most to the relationship between school climate and unauthorized absenteeism. Students who rated teacher expectations as good (4th quartile) or fairly good (3rd quartile) were less likely to be absentees (OR = 0.55 [95% CI: 0.35–0.85]; OR = 0.58 [95% CI: 0.39–0.87]). The association was weaker but still apparent when controlling for potential confounders in the adjusted model. The exclusion from the analyses of students scoring above the cut-off for mental health problems in the SDQ scale did not yield different results. The same was true for analyses conducted in imputed datasets.

In , the results of separate analyses are presented for subgroups, defined by socio-demographic circumstances and by school management. The associations did not importantly differ between subgroups, with the possible exception of parental education when climate was rated by students. The association seen in the whole group appeared to be stronger for students with highly educated parents than for students whose parents did not attend university. There was a tendency to higher unauthorized absenteeism in municipal schools (but not in independent schools) with the highest quartile of teacher rated climate

Table 5. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of unauthorized absenteeism according to total scores of school climate, separately by socio-demographic characteristics of the students and by school management.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between school climate and unauthorized absenteeism among students aged 13–16 years. Contrary to our initial hypothesis there were no clear nor consistent associations between school climate and unauthorized absenteeism when school climate was rated by teachers. However, the results showed that a positive school climate was associated with less unauthorized absenteeism when the climate was rated by students in the school, consistent with the original study hypothesis. These associations were not significantly modified by parental origin, or type of school management, while appeared somewhat stronger among children of highly educated parents.

Few studies have investigated the association between absenteeism and school climate as academic environment. Those that did identified teacher expectations, teacher-student relationships, and teacher classroom management as factors associated with lower absenteeism (Havik et al., Citation2015; Van Eck et al., Citation2017; Virtanen et al., Citation2009). Overall, our results with students’ ratings are in line with these observations. Our study points towards a particular importance of teachers’ clear communication of high expectations towards their students’ achievements. Admittedly, teachers’ expectations are difficult to modify with improved professional curricula as this change would involve attitudes rather than practices and routines. However, this result deserves attention because it is consistent with previous findings from this longitudinal study, where students endorsing high academic expectations had a better profile of mental health than students having low expectations (Almroth et al., Citation2018).

The association between positive school climate and lower unauthorized absenteeism in students’ ratings in this study appeared robust to the adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics such as parents’ educational level, parents’ country of birth, or students’ gender. Thus, while links between these characteristics and absenteeism have been reported in previous studies (Balkis et al., Citation2016; Havik et al., Citation2015; Skedgell & Kearney, Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2013), in this sample they did not significantly confound the association between school climate and absenteeism. Of note, a separate analysis according to parental education indicated that the “protective” effect of an overall good school climate was stronger among students with highly educated parents.

However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of low sample sizes in subgroup analyses and because the high number of comparisons may have entailed some associations to emerge by chance.

The absence of clear associations between school climate rated by teachers and students’ unauthorized absenteeism was unexpected. In previous studies, a tendency has been identified for teachers to give more positive ratings of school climate than students (Dernowska, Citation2017; Mitchell et al., Citation2010). This tendency was also observed in this study, in which teachers gave higher average climate scores than students. Indeed, in the cited study by Hultin et al. (Citation2018) there was a poor correlation between the two climate ratings. It is possible that the teachers’ instrument includes perspectives (for instance, cohesion between teaching personnel) that are somewhat more distal with respect to students’ perceptions and corresponding behaviours. On the other hand, students’ perceptions of school climate may be closely related to individuals’ decisions of attending/not attending school. This difference suggests that in future studies of school climate, it will be essential to include both teachers’ and students’ perspectives.

The counter-intuitive result that the utmost positive range of climate score rated by teachers was not associated with less unauthorized absenteeism – rather the contrary, especially in publicly run schools cannot be easily interpreted. A chance finding due to the high number of comparisons cannot be ruled out. However, it may also reflect the social heterogeneity of students in municipal schools, which also constitute the larger proportion in the sample and reported a higher proportion of absentees than independent schools. In public schools, students’ behaviour and bond to school may not be linked to the positive view that the teaching staff have of the pedagogic climate. Independent schools in Sweden are generally attended by smaller groups of students of high socio-economic backgrounds (Giota et al., Citation2019), whose behaviour may more be easily influenced by the general academic climate rated by the staff.

Strengths and Limitations

The multi-informant approach in the measurement of school climate is a prominent strength of this study, as school climate is a multi-dimensional construct (Wang & Degol, Citation2016). A second advantage rests on the longitudinal design, as multiple measurements of school climate collected during grades 7, 8 and 9 render a more stable measure of school climate.

The design of the present study does not allow causal interpretations of the relationship between school climate and unauthorized absenteeism, among other things because exposure to school climate and response changes were studied concurrently. However, it is reasonable to assume that a student’s unauthorized absenteeism during a particular academic year is more influenced by proximal factors (i.e., what is actually happening in the school during that year) than it is by factors distant in time (i.e., what happened in the previous year). In this study a broad range of potential confounders was considered at the family, schools and individual level. Nevertheless, it is possible that residual positive or negative confounding explains part of the observed associations, or the lack of associations.

Importantly, school climate in this study was measured as ecologic construct at the school-level through informants who were independent from the individuals on whom the actual unauthorized absenteeism was measured. While this methodological feature has the obvious strength to avoid reverse causation (i.e., truant individual reporting poor climate as justification of their behaviour) it may not provide measurement that are very sensitive to individual perceptions and changes in such perceptions, thus explaining the modest strength of the associations.

The results of this study may also have been influenced by the choice of cut-off point for absenteeism, in accordance with Hancock et al. (Citation2017), i.e., lower than in previous studies (Balfanz & Byrnes, Citation2012; Berman et al., Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2013; Van Eck et al., Citation2017). Thus, the low threshold for unauthorized absenteeism may have diluted the associations with school climate. However, we note that the threshold used identified between 5% and 12% of the study population while increasing the threshold would have identified very few students as being absentees. In this context, the students’ level of unauthorized absence still represents more problematic absence compared to their peers.

Finally, the school and student sample in this longitudinal study suffered from low participation rates at inception, which may have restricted the range of socio-economic circumstances, of school climate and of the extent of absenteeism. Also, attrition during follow-up may have biased estimates of associations toward the null if it occurred not differentially for both exposure and outcome, i.e., if the association between school climate and absenteeism were not different among retained and lost to follow-up. A specific case can illustrate this bias. Students moving to schools outside the participating ones were considered “lost to follow-up”, therefore contributed to the attrition of the longitudinal study. This exclusion contributed to a modest loss of statistical power because it concerned a small proportion of the original sample, but it is unlikely that the association under study was different among these students compared to those retained who also changed school, but attended one of those participating in the study.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Further Studies

Besides confirming the academic dimension of school climate, as rated by students, as important to unauthorized absenteeism, this study indicates a potential for future interventions, given the links between absenteeism and academic failure (Chen et al., Citation2016; Maynard et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, it will be important to conduct future studies in more socially diverse school settings and student samples, with the goal to identify factors more specifically predicting unauthorized absenteeism and amenable to be changed through school-level interventions.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board (reference number: 2012/1904-31/01). Written informed consent from the parents/guardians was required for the child’s participation, separately for the three components of data collection (survey, record linkage with registers, saliva sampling and epigenetic analyses).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Melody Almroth at the Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden for her work on creating syntax for the statistical program SAS.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almroth, M. C., László, K. D., Kosidou, K., & Galanti, M. R. (2018). Association between adolescents’ academic aspirations and mental health: A one-year follow-up study. European Journal of Public Health, 28(3), 504–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky025

- Attwood, G., & Croll, P. (2006). Truancy in secondary school pupils: Prevalence, trajectories and pupil perspectives. Research Papers in Education, 21(4), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520600942446

- Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C., & Leaf, P. J. (2011). Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.329

- Balfanz, R., & Byrnes, V. (2012). Chronic absenteeism: Summarizing what we know from nationally available data. Johns Hopkins University.

- Balkis, M., Arslan, G., & Duru, E. (2016). The school absenteeism among high school students: Contributing factors. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.6.0125

- Berman, J., McCormack, M., Koehler, K., Connolly, F., Clemons-Erby, D., Davis, M., Gummerson, C., Leaf, P., Jones, T., & Curriero, F. (2018). School environmental conditions and links to academic performance and absenteeism in urban, mid-Atlantic public schools. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 221(5), 800–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.04.015

- Brookmeyer, K. A., Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2

- Chen, C., Culhane, D. P., Metraux, S., Park, J. M., & Venable, J. C. (2016). The heterogeneity of truancy among urban middle school students: A latent class growth analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(4), 1066–1075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0295-3

- Daraganova, G., Mullan, K., & Edwards, B. (2014). Attendance in primary school: Factors and consequences (Occasional Paper No. 51). Department of Social Services.

- Demir, K., & Akman Karabeyoglu, Y. (2015). Factors associated with absenteeism in high schools. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 62, 55–74. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2016.62.4

- Dernowska, U. (2017). Teacher and student perceptions of school climate. Some conclusions from school culture and climate research. Journal of Modern Science, 32(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.13166/jms/125603

- Ek, H., & Eriksson, R. (2013). Psychological factors behind truancy, school phobia, and school refusal: A literature study. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2013.818899

- Fan, W. H., Williams, C. M., & Corkin, D. M. (2011). A multilevel analysis of student perceptions of school climate: The effect of social and academic risk factors. Psychology in Schools, 48(6), 632–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20579

- Galanti, M. R., Hultin, H., Dalman, C., Engström, K., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Forsell, Y., Karlberg, M., Lavebratt, C., Magnusson, C., Sundell, K., Zhou, J., Almroth, M., & Raffetti, E. (2016). School environment and mental health in early adolescence – a longitudinal study in Sweden (KUPOL). BMC Psychiatry, 16, 243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0919-1

- Garvik, M., Idsoe, T., & Bru, E. (2014). Depression and school engagement among Norwegian upper secondary vocational school students. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(5), 592–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2013.798835

- Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

- Giota, J., Bergh, D., & Emanuelsson, I. (2019). Changes in individualized teaching practices in municipal and independent schools 2003, 2008 and 2014 - student achievement, family background and school choice in Sweden. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 5(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2019.1586513

- Goodman, R., Ford, T., Simmons, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). Using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.6.534

- Grosin, L. (2004). Skolklimat, prestation och anpassning i 21 mellan- och 20 högstadieskolor [School climate, achievement and adjustment in 21 middle schools and 20 secondary schools]. Forskningsrapport 71: Pedagogiska institutionen, Stockholms Universitet.

- Hancock, K. J. (2019). Does the reason make a difference? Assessing school absence codes and their associations with student achievement outcomes [Doctoral dissertation]. https://doi.org/10.26182/5cdb79edc35d8

- Hancock, K. J., Lawrence, D., Shepherd, C. C. J., Mitrou, F., & Zubrick, S. R. (2017). Associations between school absence and academic achievement: Do socioeconomics matter? British Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 415–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3267

- Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). Assessing reasons for school non-attendance. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904424

- Hendron, M., & Kearney, C. A. (2016). School climate and student absenteeism and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Children & Schools, 38(2), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdw009

- Hultin, H., Eichas, K., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Dimitrova, R., Karlberg, M., & Galanti, M. R. (2019). Pedagogical and social school climate: Psychometric evaluation and validation of the student edition of PESOC. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1415962

- Hultin, H., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Eichas, K., Karlberg, M., Grosin, L., & Galanti, M. (2018). Psychometric properties of an instrument to measure social and pedagogical school climate among teachers (PESOC). Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1258661

- Kearney, C. A. (2008). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: A contemporary review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012

- Kearney, C. A., & Albano, A. M. (2004). The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: Diagnostic aspects. Behavior Modification, 28(1), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503259263

- Kearney, C. A., Gonzálvez, C., Graczyk, P. A., & Fornander, M. J. (2019a). Reconciling contemporary approaches to school attendance and school absenteeism: Toward promotion and nimble response, global policy review and implementation, and future adaptability (part 1). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02222

- Kearney, C. A., Gonzálvez, C., Graczyk, P. A., & Fornander, M. J. (2019b). Reconciling contemporary approaches to school attendance and school absenteeism: Toward promotion and nimble response, global policy review and implementation, and future adaptability (part 2). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02605

- Kearney, C. A., & Graczyk, P. (2014). A response to intervention model to promote school attendance and decrease school absenteeism. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-013-9222-1

- London, R. A., Sanchez, M., & Castrechini, S. (2016). The dynamics of chronic absence and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(112), https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2741

- Maynard, B. R., Heyne, D., Brendel, K. E., Bulanda, J. J., Thompson, A. M., & Pigott, T. D. (2018). Treatment for school refusal among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515598619

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2010). Education Act, 2010:800. 2 Ch. 25 and 26 §§.

- Mitchell, M. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Student and teacher perceptions of school climate: A multilevel exploration of patterns of discrepancy. Journal of School Health, 80(6), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00501.x

- Ramberg, J., Låftman, S., Fransson, E., & Modin, B. (2019). School effectiveness and truancy: A multilevel study of upper secondary schools in Stockholm. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24, 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1503085

- Raykov, T. (2012). Scale construction and development using structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 472–492). The Guilford Press.

- Rocque, M., Jennings, W. G., Piquero, A. R., Ozkan, T., & Farrington, D. P. (2017). The importance of school attendance: Findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development on the life-course effects of truancy. Crime & Delinquency, 63(5), 592–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716660520

- Rutter, M., & Maughan, B. (2002). School effectiveness findings 1979–2002. Journal of School Psychology, 40(6), 451–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00124-3

- Rutter, M., Maughan, B., Mortimore, P., Ouston, J., & Smith, A. (1979). Fifteen thousand hours: Secondary schools and their effect of children. Open Books.

- Scoring the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for age 4–17 or 18+. (2016). https://www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/c0.py. (20 June 2016, date last updated)

- Silverman, R. M. (2012). Making waves or treading water? An analysis of charter schools in New York State. Urban Education, 48, 257–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085912449840

- Skedgell, K., & Kearney, C. A. (2016). Predictors of absenteeism severity in truant youth: A dimensional and categorical analysis. American Secondary Education, 45(1), 46–58.

- Skedgell, K., & Kearney, C. A. (2018). Predictors of school absenteeism severity at multiple levels: A classification and regression tree analysis. Children & Youth Services Review, 8(6), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.043

- Swedish National Agency for Education [Skolverket]. (2010). Skolfrånvaro och vägen tillbaka: långvarig ogiltig frånvaro i grundskolan ur elevens, skolans och förvaltningens perspektiv. Skolverket.

- Swedish National Agency for Education [Skolverket]. (2019). Snabbfakta om förskola, annan pedagogisk verksamhet, fritidshem, skola och vuxenutbildning [Quick facts about pre-school, other educational activities, after-school activities, school, and adult education]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/snabbfakta-utbildningsstatistik

- Swedish School Inspectorate [Skolinspektionen]. (2016). Omfattande ogiltig frånvaro i Sveriges grundskolor. Skolinspektionen.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357–385. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483907

- Thornton, M., Darmody, M., & McCoy, S. (2013). Persistent absenteeism among Irish primary school students. Educational Review, 65, 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.768599

- Uline, C., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2008). The walls speak: The interplay of quality facilities, school climate, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810849817

- Van Eck, K., Johnson, S. R., Bettencourt, A., & Lindstrom Johnson, S. (2017). How school climate relates to chronic absence: A multi–level latent profile analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.10.001

- Van Horn, M. L. (2003). Assessing the unit of measurement for school climate through psychometric and outcome analyses of the school climate survey. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(6), 1002–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403251317

- Virtanen, M., Kivimäki, M., Luopa, P., Vahtera, J., Elovaionio, M., Jokela, J., & Pietikäinen, M. (2009). Staff reports of psychosocial climate at school and adolescents’ health, truancy and health education in Finland. European Journal of Public Health, 19, 554–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp032

- Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1