ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to analyze the perceptions on the local school and further education in the local community from a school leader’s perspective. Another aim is to explore characteristics of sparsely populated rural areas. Data were derived from a survey on Swedish school leaders (n = 1,270). The results show significant variances between four municipality types – the local school and further education are, according to the school leaders, generally valued highest in the large cities and lowest in sparsely populated rural municipalities. The article also reveals certain details of sparsely populated rural areas, for instance, a different type of expectation but also value of the local school, and well-developed collaborations between the schools and the local community. Furthermore, low expectations on the local school is also voiced by school staff. These nationwide results contribute to ongoing discussions on school leadership and education in the Scandinavian countries.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, there is a great variety of local school contexts, establishing specific conditions for school leaders’ work. Research have shown that successful school leadership is linked to the capacity to understand and adapt leadership to the specific setting (e.g., Hallinger, Citation2011; Moos et al., Citation2011; Wahlstrom et al., Citation2015) which, however, does not mean that school leaders must use qualitatively different practices in every different context (Leithwood et al., Citation2008). Against this background, this article draws specific attention to school leaders in rural areas, a research area that hitherto has received modest attention in leadership research, both internationally and in the Scandinavian context.

In reviewing the current body of research on school leadership in rural areas, Preston et al. (Citation2013) identified important challenges that are typical of rural school leaders. With regard to school accountability and improvement work, rural school leaders, as opposed to their colleagues in larger cities, often lack administrative support and basic resources even if they are expected to be held to the same accountability standards (see also Arnold et al., Citation2005; Ashton & Duncan, Citation2012; Canales et al., Citation2008). Also, these school leaders work more frequently with social issues due to poverty and families’ socio-economic standards, handling a wide range of tasks and expectations in the local leadership. In this regard, the work of Loeb et al. (Citation2010) showed that school leaders who have less experience and less education often work in the most challenging contexts – in their case with many low-income, non-White and/or low-achieving students. As noted by Helgøy and Homme (Citation2017), parents with less formal education are also more insecure when it comes to their own experiences of school and education, which could reduce collaboration between parents and schools. Several studies have also shown that school leaders in rural areas spend a greater amount of time building strong community relations with local organizations and their members (Harmon & Schafft, Citation2009). Research have also revealed that rural school leaders spend less time collaborating with other school leader colleagues, e.g., due to long distances between schools, a wide range of tasks, and a culture of working alone (e.g., Steward & Matthews, Citation2015).

Regarding Scandinavia and Sweden, influential research have shown that context counts and that leadership values are essential. School leaders, as leaders, are handling relations with many different groups inside and outside of schools, both in hierarchy and in different networks (Paulsen et al., Citation2016). In Sweden and in the other Nordic countries, school leaders have to navigate between the national leadership (through the Education Act, nationwide curricula), local political leadership (school boards with members nominated by political elections), and superintendents (serving the municipal political board and head of the department). These relations have also been subject to longitudinal studies in the Nordic countries (see e.g., Moos et al., Citation2016; Moos & Paulsen, Citation2014). The ongoing interactive processes, holding different power relations, build on confidence and trust and involve both risks and opportunities for school leaders (Helstad & Møller, Citation2013). One dilemma, with respect to these contextual differences, concerns how to develop equivalence in education in all schools, regardless of the local context, size, socio-economic situation, and so forth. Statements regarding these dilemmas also address the perception of the entire mission of education and bildung (cf. Moos et al., Citation2016). It is worth emphasizing in this regard that former research have also suggested that the current trends of globalization and New Public Management (NPM) shape an inequality between urban and rural education (Freie & Eppley, Citation2014; Starr & White, Citation2008). Recent research on Swedish school leaders’ professional identity (Nordholm et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b) also raised questions on how the local context is taken into account and integrated in school leaders’ leadership. The point of departure in this article draws attention to these former observations, particularly when it comes to school leadership in rural areas and how inquiries of this nature are played out in these areas, both in Sweden and in Scandinavia.

By observing this current body of Scandinavian and Swedish research, it becomes clear that few studies have analyzed nationwide data from a comparative perspective to explicitly explore similarities and differences between school leaders in rural areas and other contexts. Having this focus, this article engages with the growing body of research that draws attention to school leaders in rural areas, which mostly have been conducted in American, Canadian, and Australian contexts (cf. Preston et al., Citation2013). As an empirical case, Sweden is a sparsely populated country; thus, there is a long tradition of small schools in the countryside. About 125 of Sweden’s 290 municipalities have a population of fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, and 25 of these have fewer than 5,000 inhabitants (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2017). The work of Johansson (Citation2017) as well as Beach et al. (Citation2018), however, have contributed important insights on participation and the influence of young people in different rural and urban contexts. These former findings also address essential questions on equality and power relationships between town and countryside. In times when some areas are being de-populated and inequality occurs between those who move into the large cities and those who decide to live in the countryside, one could argue that schools and their school leaders have a key function in the local community.

Accordingly, there are strong arguments to pay further attention to perceptions regarding the local school and further education in the local community as well as to the experiences of school leaders, especially in rural areas. Empirically, this article builds on data obtained from a survey on Swedish school leaders, completed in January 2019 (subsequently detailed). The article applies the categorization of municipalities defined by the Swedish Board of Agriculture (Citation2019) (“large city,” “city,” “rural areas,” and “sparsely populated rural areas”). The aim of this article is to analyze the perceptions on the local school as well as further education in the local community from a school leader’s perspective. Another aim is to explore characteristics of sparsely populated rural areas. The following research questions directed the analytical work:

(1) What are the perceptions of school leaders in different municipalities regarding the local school and further education in the local school community?

(2) Do school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas have specific characteristics, and, if so, how can these differences be explained?

The article is structured as follows. First, details on the analytical work is provided. The results of the quantitative and the qualitative data analysis are then presented in an integrated write-up. The article ends with a discussion and some conclusions.

2. Method

2.1. Survey and Sample

Regarding the survey, e-mail addresses to school leaders were obtained from the Swedish National Agency for Education. According to the official statistics (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2019), there are currently 3,600 school leaders in Sweden in full-time employment. With regard to how the school leader’s assignment is formed in the Swedish context, a number of considerations were made. Temporary appointed or hired-in school leaders were excluded because they have fewer opportunities to answer detailed questions on leadership linked to the local community. Deputy school leaders were also excluded because in Sweden, they do not have an overall responsibility from a school leadership perspective, for instance, regarding legal matters and economic issues such as budget and salary setting. School leaders in both public and independent schools, however, were included. One main argument for integrating and merging the different forms of school ownership was that no significant differences were detected between the various forms.

Taking this into consideration, the survey targeted approximately 3,000 school leaders. After sending the initial e-mail, it became obvious that the e-mail addresses were not entirely updated; consequently, some work was done to find the “missing” school leaders. New e-mails were sent to these school leaders. Thereafter, two reminders were sent out to all the school leaders.

Despite these challenges, the data collected meet the purpose and objectives of this article. The final sample of school leaders (n = 1,270) represented 249 out of the 290 local municipalities. There was a nice spread between the four types of municipalities defined by the Swedish Board of Agriculture (Citation2019) (large city, city, rural areas, and sparsely populated rural areas). Another strength of the empirical data is that there was a good spread, in terms of age, number of years in the profession, size of the school unit, gender, and a satisfying spread in terms of school ownership.

Regarding the non-response analysis, some possible factors need to be highlighted. One difficulty already highlighted was the struggles in obtaining updated e-mail addresses from the National Agency for Education. Another factor is that Swedish school leaders tend to change jobs more often than their European colleagues (OECD, Citation2016), which means that positions are vacant and that quite a lot of school leaders are replaced by a temporary school leader. An additional factor was also that some e-mails got stuck in the municipal spam filters; therefore, all reminders were sent directly to the schools. Thirteen participants were dropped because of missing data.

2.2. The Quantitative Data Analysis

The questionnaire consisted of 42 questions. However, only questions on school leaders’ backgrounds and those addressing perceptions on education in the local community were used in this analysis. The first part of the questionnaire included questions on the following background variables: school authorities (independent or public), type of school (preschool, primary, or secondary), type of municipality, gender, age, and length of time as school leader.

In the second part, the school leaders were asked to estimate different statements regarding their perceptions on the value of education in their local context. The school leaders were asked to answer the questions by indicating on a scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (to a great extent), how much they agreed with the statements. The statements in the questionnaire pertained to: the value of the education in the local community, the number of students continuing on to upper secondary school, the number of students continuing on to university studies and finally, the opportunities to find employment after elementary school. The questions, individually and combined, address important aspects regarding the prevailing perceptions on the local school and further education in the local community from a school leader’s perspective. Thus, the quantitative analysis primarily addresses the first research question. Concerning the first question, it provides an indicator of the overall ideas and perceptions that exist in the local community. When it comes to questions two and three, they address the attitudes toward further education after compulsory school and also whether further studies are considered important in the local community. Regarding the fourth and final question, it exemplifies an alternative (or competitor) to further education. Thus, the question says something about the relationship between further studies and employment, and whether both girls and boys should study when there may be jobs in the local community.

Data were analyzed using software for quantitative data analysis (SPSS) by comparing distributions of the ratings for the questions on school leaders’ prevailing perceptions on the local school and further education in the local community. The Chi2-analyses were executed by computing measures and testing the relationships between the items in the questionnaire and the type of municipality. To examine the relationship between the type of municipality and school leaders’ perceptions, a post hoc test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was performed.

2.3. The Qualitative Data Analysis

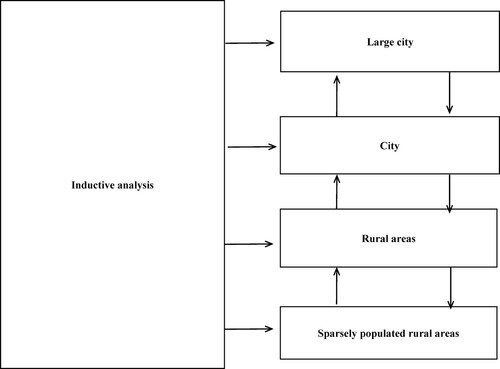

The qualitative data analysis complemented and deepened the Chi2-analysis. Free text answers were imported and organized with the assistance of software for qualitative data analysis (NVivo 12). An analysis scheme (cf. Miles et al., Citation2014) was developed to structure the analytical work (see ). Initially, the analysis strived to detect extracts demonstrating what the school leaders’ perceptions are on the local school and further education in the local community. These descriptions were grouped by the four municipality types defined by the Swedish Board of Agriculture (Citation2019) (large city, city, rural areas, and sparsely populated rural areas). Extracts and quotes from school leaders from the four municipality types were, in turn, compared and analyzed to explore whether school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas have certain characteristics, and, if so, how these differences can be explained. Accordingly, the qualitative analysis primarily addressed research question two by exploring the variations shown in the quantitative analyses.

The extracts and quotes provided below are selected because they are illustrative examples but also contrast cases in order to deepen the quantitative analysis. It is also worth highlighting that each anonymized school leader is unique, i.e., they are only used once in the result presentation.

3. Results

This section is structured by the four statements that the school leaders were asked to rate by indicating on a scale ranging from 1 to 6 the extent to which they agreed with the statements. The results are presented under three subheadings (perceptions on the local school, perceptions on further education, and job opportunities after elementary school). The results of the qualitative analysis are, as noted, used to explore and expand the results of the Chi2-analyses and the two research questions put forward.

3.1. Perceptions on the Local School and Education

In the initial analysis, school leader’s perceptions of how the local school and education are valued in the local community are centered. The distribution of school leaders’ estimation is presented below (see ).

Tabel 1. Distribution of principals’ estimation of the value of education in the local society.

As shown in , school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas estimated the value of education in their local community lower than school leader’s estimation in the three other municipality types. Thus, the Chi2-analysis showed a significant relationship between the type of municipality and estimations made by the school leaders, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 174.70, p < .001. Measures of relationship between columns and rows were computed, and the Cramer’s V equaled .35, indicating a moderate effect size. Post hoc test showed that education was less valued in rural areas and sparsely populated area (p < .005).

The qualitative analyses provided a more in-depth picture of the Chi2- analysis concerning characteristics of sparsely populated rural areas, contrasting the three other municipality categories. More precisely, no school leader in this municipality type depicted that the expectations on the local school are high, at least from a pedagogical point of view, and that education is valued highly in the local community. In their explanations, school leaders described these perceptions in the local community, in terms of the “rural culture,” “the mentality of a small municipality,” “industrial community mentality,” and “low education culture.”

However, the results showing low expectations on the local school and further education could be problematized. More precisely, even if the expectations, generally, are lower in these municipalities from a pedagogical point of view, parents still have clear expectations on the local school. Parker, a school leader in a sparsely populated municipality, explained:

I work in a small municipality in which there is only one F-6 school. Parents have an expectation to be involved and decide about many things in the school, especially if things are not good. Therefore, I have to work a lot to promote good forms of collaboration with them.

There is a culture in the municipality that the social (mission) of the school is more important than the education itself. Many people also know how it should be.

The fact that I live and work in the same small community makes me feel greater pressures from the surrounding community. Here, I cannot resign and seek another school leadership job because then, I let the whole village down.

3.2. Perceptions on Further Education

The second analysis centered around school leaders’ estimations on whether students continue on to upper secondary school. This analysis also focused on school leaders’ estimation of students continuing on to university studies. The distribution of school leaders’ estimations is shown below (see and ).

Table 2. Distribution of principals’ estimation that only a few students continue on to upper secondary school.

Table 3. Distribution of principals’ estimation that only a few students continue on to university studies.

The table shows a significant relationship between the type of municipality and school leaders’ estimations on whether students continue to upper secondary school, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 68.90, p < .001. More precisely, school leaders in large cities and cities estimated that more students continue on to upper secondary school than school leaders in rural and sparsely populated rural areas. It is worth noting that nearly 30% of the school leaders could not estimate the extent to which students continued on to upper secondary school. The measure of the relationship in this analysis was Cramer’s V = .16, indicating a small effect size. Post hoc tests showed that principals in rural areas and in sparsely populated areas perceived that only a few students would continue on to upper secondary school (p < .005).

The table shows a significant relationship between the type of municipality and the estimation of the school leaders, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 89.82, p < .001. More detailed, school leaders in large cities and cities estimated that students continue on to university studies to a greater extent than school leaders in rural and sparsely populated rural areas (p < .005). Comparable to the former question, over 30% of the school leaders could not estimate the number of students continuing on to university studies.

The qualitative data analysis generally confirmed the overall picture revealed in the Chi2 analysis. To start with, none of the school leaders in the city municipalities commented that only a few students go on to upper secondary school, or that university studies are considered to be unimportant, or that students find employment immediately after compulsory school in their local community. This is also true for the school leaders in more “challenging” school contexts. However, this does not mean that such perceptions do not exist in these local communities, but they do not appear to be characteristic of these two municipality types.

Regarding characteristics of school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas, the qualitative analysis identified details that could expand the understanding of the differences between the municipality types. Some school leaders argued that there is a “lack of an education culture” and that there is “skepticism toward education” in general, particularly toward university studies. Such examples contrast the opinions voiced by school leaders in the other municipality types, most clearly in the city and large city category. Especially in the two city categories, school leaders in both the public and the independent schools expressed that parents and the local community have high expectations that the school should provide a solid knowledge base for pupils’ further studies and that pupils should receive high grades so that they can enter the “right” upper secondary school. Quinn exemplified such expectations:

(We have) strong parents who have both the financial and the educational status, which can be a challenge. Many times … they can be burdensome if they receive a negative answer when it comes to a holiday request or low grades.

The lack of academic traditions in the local community, but also among the school staff. There is also a lack of knowledge based on facts among school staff and among parents.

Finally, it may also be relevant to note that school leaders actively sought to influence attitudes toward further education. School leaders also expressed a desire to influence pupils and youths by encouraging them to undertake further studies. For example, Billie argued that “I would like to create an increased interest in studies in general, meaning that students should be able to realize the advantages of further studies.” Another school leader, Jamie, stated that (s)he would “like to see a greater future for our young people to stay in the municipality – opportunities to study further (without having to move).” In a similar vein, Kim explained that “I want the school to be the foundation that makes young people stay in the countryside, or choose to move back.”

Summing up this second section, school leaders in large cities and cities estimated that more students continue on to upper secondary school compared to school leaders in rural and sparsely populated rural areas. In addition, school leaders in large cities and cities also estimated that students continue on to university studies to a greater extent than school leaders in rural and sparsely populated rural areas. Regarding the qualitative analysis and characteristics of sparsely populated rural areas, these school leaders described that there is a “lack of an education culture” in these municipalities and that there is “skepticism toward education” in general, particularly toward university studies. As noted, such vocabularies and explanations were not found among school leaders in the other municipality types. These dictums also contrast the school leaders in the two city categories, who recurrently emphasized high expectations among parents and in the local community regarding the level of teaching and on pupils’ grades.

3.3. Job Opportunities After Elementary School

The last part of the analysis focuses on school leaders’ estimation of the opportunity to find employment after elementary school. The results are presented below (see ).

Table 4. Distribution of principals’ estimation that opportunities to find employment after elementary school are good.

The table shows a relationship between the type of municipality and school leaders’ estimations, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 41.10, p < .001. However, this relationship was rather weak, as shown by a Cramer’s V = .16. Post hoc test showed that principals in rural areas, in particular, estimated that the opportunities to find employment after school were low (p < .005). In addition, the same pattern as for the above questions was found, that is, nearly 30% of the school leaders could not estimate the possibilities to find employment after elementary school.

Thus, to delve deeper into the questions on job opportunities after compulsory school and the relationship between further studies and employment, the qualitative analysis provided some details of sparsely populated rural communities. For example, some school leaders explained that there are well-developed collaborations between schools and actors in the local community that can facilitate students finding employment even directly after elementary school. Such descriptions are in contrast to those in the other municipality types, not least the large city and the city type where school leaders instead request closer collaborations between schools and local companies, for instance, through internships, study visits, and so forth.

At the same time, several school leaders commented that jobs are getting fewer even in sparsely populated rural areas, which increases the importance of education and the existence of the local school. Some school leaders also underscored that one thing does not necessary exclude the other, that is, there is no contradiction between more students getting an academic education and that local companies, for example, in the forest or steel industry, continue to develop, as described here by Kendall:

(I wish) that the attitude toward education is increased and that the students are given the opportunity to work in the village. (I wish) also that the inhabitants, in line with increased educational level, develop the business sector in more areas and also in sustainable development.

4. Discussion

The above-analysis has addressed two research questions. The first question centered around prevailing perceptions regarding the local school and further education in the local community from a school leader’s perspective. The second question focused on whether school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas have certain characteristics, and, if so, how these differences could be explained. The results showed significant variances between the four municipality types defined by the Swedish Board of Agriculture (Citation2019) (large city, city, rural areas, and sparsely populated rural areas) regarding perceptions on the local school and further education. Generally, the local school and further education, according to participating school leaders, are valued highest in the large cities and lowest in the sparsely populated rural municipalities. In addition, the analysis showed that these school leaders estimated that the opportunities to find employment after elementary school was higher compared to their colleagues in the three other municipality types, even if this relationship was somewhat weak. Another finding of relevance is that a rather large number of school leaders had difficulty answering several of the survey questions. This indicates that Swedish school leaders might have a somewhat vague knowledge on the local context and how it impacts their leadership. This seems problematic, not least because successful leadership is rooted in the local context (cf. Hallinger, Citation2011; Wahlstrom et al., Citation2015).

Regarding characteristics of school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas and how these characteristics can be explained, the qualitative analysis generally confirmed the results of the Chi2 analyses. However, even if school leaders expressed that the expectations on the local school and further education are low from a pedagogical point of view, they explained that the local school, as such, can have an important function in the local community. Thus, parents’ expectations and perceptions are somewhat different compared to the other types of municipalities. Noteworthy that school leaders expressed that school staff also had feelings of low expectations on the local school and skepticism toward further education. Some school leaders expressed that they try to influence pupils and youths by encouraging them to undertake further studies. Regarding the opportunities to find employment after elementary school, school leaders of sparsely populated rural areas described that there are well-developed collaborations between schools and actors in the local community that can facilitate students finding employment even after elementary school. However, against the background that jobs are getting fewer even in rural areas, some school leaders stressed that further education in fact could be a prerequisite for young people to stay in these municipalities because remaining companies need well educated people. From a broader perspective, a higher education level can possibly also impinge on the attitudes and expectations on the local school and further education.

These results add important pieces to the current body of research on school leadership, both from a Scandinavian and an international perspective. Linked to previous research highlighting the importance of understanding and building school leadership rooted in the local context (see, e.g., Hallinger, Citation2011; Moos et al., Citation2011), these variations become important to consider. In recent studies on Swedish school leaders’ identity (Nordholm et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b), questions are raised regarding how the local context is taken into account and integrated in school leaders’ leadership. In this regard, the mandatory National Principal Training Program in Sweden is organized into three courses: “Educational law,” “Governance, organization and quality,” and “School Leadership.” The revised program placed a lot of focus on school law, resource allocation, systematic quality work, and governance issues. Without denying the importance of profound knowledge in these areas, we still believe that there is a need to further emphasize that school leadership, also in Sweden, is context-dependent and that the local context forms a specific starting-point for successful leadership and school improvement. Against the results of this article, this becomes perhaps even more important for school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas.

More specifically, one result that is worth highlighting regarding context concerns low expectations on the local school and further education, in combination with certain expectations on and an appreciation for the local school among parents, even it is not related to pedagogy and/or school improvement. As noted in the work of Helgøy and Homme (Citation2017), parents with less formal education are often more insecure when it comes to their own experiences of school and education, which could impact on collaborations between parents and schools. These formal results provide important perspectives to explain the characteristics of school leaders in sparsely populated rural areas found in the above analysis. The results of the article also correspond to former work on school leadership in rural areas showing that these school leaders spend a greater amount of time building strong community relations (Harmon & Schafft, Citation2009). In the present case, school leaders recurrently stressed that they put a lot of efforts building relationships with parents. At the same time, they also had to handle the fact that parents in these municipalities wanted to participate and decide on school issues, however, not necessarily related to pedagogy and school improvement. Against this background, it becomes essential for these school leaders to work for a shift regarding parents’ commitment and expectations so that it also includes children’s learning and development, i.e., areas within which they are expected to be involved.

It is also important to put the results of this study in a wider perspective based on previous discussions on the whole purpose and the mission of education in the Nordic countries (cf. Moos et al., Citation2016). Hence the variances revealed between the different municipality types provide important input for further discussions, for instance, on equivalence and the right to a proper education regardless of the region in the country, local school context, socio-economic conditions, and so forth. More specifically, if expectations on the local school and further education are lower among parents (and among school staff) in sparsely populated rural areas, questions could be raised as to equality and whether all students are given the same opportunities in the Swedish school system. At the same time, as some school leaders also pointed out, it is important to underscore that there is no inherent contradiction between further education and being able to stay in the countryside; rather, further education can be a prerequisite for doing so, after completed studies.

This wider discussion, therefore, includes questions on what kind of knowledge children and young people need and request in these areas. In the current trends of NPM and globalization, which tend to have a negative impact on rural areas (cf. Freie & Eppley, Citation2014; Starr & White, Citation2008), perhaps the time is right for a broader discussion on the purpose and goals of education but also on the concept of knowledge. In such a discussion, it becomes essential to highlight practical-aesthetic teaching subjects, but also other teaching subjects that are difficult to measure and evaluate, for example, philosophy and history. Linked to previous research (cf. Moos et al., Citation2016), we believe that there is a need to not only dictate the importance of education but also bildung. Such a discussion, in our opinion, can open up for a more vibrant school leadership rooted in the local context, where sense-making conversations between school leaders and parents can take place, including the role and function of the local school, as well as how further education can constitute a valuable platform for the children and youths in the local community.

That declared, some limitations of the current study must be underlined. Regarding methodology and the analytical work, it is relevant to note that the results of the article are “solely” based on Swedish school leaders’ experiences and therefore should be considered with some caution. Accordingly, in further case studies, it becomes important to integrate parents and other actors in the local community to attain broader and (perhaps) more nuanced images of the local school and further education, especially in sparsely populated rural areas. In addition, the categorization of municipalities (see the Swedish Board of Agriculture, Citation2019) must be highlighted. It is worth considering, for example, that the applied categorization is rather wide, which may lead to some nuances perhaps getting lost in the analysis. However, this categorization appeared more accurate compared to other classifications in the Swedish context (see e.g., Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2017) based on how the concept of “rural” areas and/or regions is presented and understood in an international context.

5. Conclusions

The results of this article show significant variances between different types of municipalities regarding perceptions on the local school and further education in the local community. Generally, the local school and further education, according to participating school leaders, are valued highest in the large cities and lowest in sparsely populated rural municipalities. Regarding further characteristics of sparsely populated rural areas, school leaders explained that even if the expectations on the local school and education are low from a pedagogical point of view, the local school, as such, can still have an important function in the local community. This is true even if parents’ expectations and prospects are somewhat different. Low expectations on the local school and skepticism toward further education are also feelings that are visible among school staff. School leaders also expressed that they try to influence pupils and youths by encouraging them to undertake further studies. They also described that there are well-developed collaborations between schools and actors in the local community that can facilitate students finding employment even after elementary school. Still, school leaders also emphasized that jobs are getting fewer even in rural areas. Some school leaders stressed that further education could be a prerequisite for young people to stay in these municipalities because remaining companies need well educated people.

These results add important knowledge to the current body of educational research, both in a Scandinavian and an international perspective, addressing essential questions on school leaders’ work, but also wider angles on the whole purpose of education, bildung, and power-relationships between the town and the countryside.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arnold, M. L., Newman, H. H., Gaddy, B., & Dean, C. B. (2005). A look at the condition of rural education research: Setting a direction for future research. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 20(6), 1–25.

- Ashton, B., & Duncan, H. E. (2012). A beginning rural school leader’s toolkit: A guide for success. The Rural Educator, 33(1), 37–47.

- Beach, D., From, T., Johansson, M., & Öhrn, E. (2018). Educational and spatial justice in rural and urban areas in three Nordic countries: A meta-ethnographic analysis. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1430423

- Canales, M. T., Tejeda-Delgado, C., & Slate, J. R. (2008). Leadership behaviours of superintendent/school leaders in small, rural school districts in Texas. The Rural Educator, 29(3), 1–7.

- Freie, C., & Eppley, K. (2014). Putting foucault to work: Understanding power in a rural school. Peabody Journal of Education, 89(5), 652–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2014.958908

- Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111116699

- Harmon, H. L., & Schafft, K. (2009). Rural school leadership for collaborative community development. The Rural Educator, 30(3), 4–9.

- Helgøy, I., & Homme, A. (2017). Increasing parental participation at school level: A ‘citizen to serve’ or a ‘customer to steer’? Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1343625

- Helstad, K., & Møller, J. (2013). Leadership as relational work: Risks and opportunities. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 16(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2012.761353

- Johansson, M. (2017). Yes, the power is in the town: An ethnographic study of student participation in a rural Swedish secondary school. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 27(2), 61–76.

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060

- Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D., & Horng, L. (2010). Principal preferences and the uneven distribution of principals across schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373710369833

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed). Sage Publications.

- Moos, L., Johansson, O., & Day, C. (Eds.). (2011). How school principals sustain success over time. International perspective. Springer. Studies in Educational Leadership 14.

- Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (Eds.). (2016). Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain. Springer. Educational Governance Research 2.

- Moos, L., & Paulsen, J. M. (Eds.). (2014). School boards in the governance process. Springer. Educational Governance Research 1.

- Nordholm, D., Arnqvist, A., & Nihlfors, E. (2020a). Principals’ emotional identity – the Swedish case. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1716326

- Nordholm, D., Arnqvist, A., & Nihlfors, E. (2020b). Principals’ identity – developing and validating an analyses instrument through a Swedish case. International Journal of Leadership in Education. Pre-published online 10 August. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1804621

- OECD. (2016). Principalship for learning. Insights form TALIS 2013. http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/school-leadership-for-learning_9789264258341-en#.VYgrefJ700

- Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Brinkkjear, U., & Risku, M. (2016). Superintendents in hierarchy and network. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 207–231). Springer.

- Preston, J. P., Jakubiec, B. A. E., & Kooymans, R. (2013). Common challenges faced by rural school leaders: A review of the literature. The Rural Educator. http://epubs.library.msstate.edu/index.php/ruraleducator/article/view/119

- Starr, K., & White, S. (2008). The small rural school principalship: Key challenges and cross-school responses. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 23(5), 1–12.

- Steward, C., & Matthews, J. (2015). The lone ranger in rural education: The small rural school principal and professional development. The Rural Educator, 36(3). https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v36i3.322

- The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. (2017). Kommungruppsindelning 2017. Omarbetning av Sveriges kommuner och landstings kommungruppsindelning. The Swedish Association of Local ities and Regions.

- The Swedish Board of Agriculture. (2019). Kommunindelning. https://nya.jordbruksverket.se/stod/programmen-som-finansierar-stoden/var-definition-av-landsbygd

- Wahlstrom, K. L., Seashore Louise, K., Leithwood, K., & Anderson, S. (2015). Investigating the links to improved student learning. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.