ABSTRACT

This paper presents findings from a survey among Norwegian K-12 teachers (n = 771), addressing their perceived collaboration with parents when students exhibit internalizing or externalizing behaviour. Positive teacher-parent collaboration is important to enhance student learning. However, behaviour difficulties among students may put the teacher-parent relationship under strain and affect the teachers’ sense of self-efficacy. Through factor analysis, analysis of variance and multiple regression analysis, the paper identifies how individual teacher variables such as gender, years of experience and additional training in psychology or special needs, and school variables such as grade levels, the schools’ participation in mental health training programmes and collective teacher efficacy, may affect perceived quality of collaboration. The findings showed that collective teacher efficacy is significant for positive teacher-parent collaboration, and that teachers perceived the collaboration as more conflictual when students show externalizing behaviour. Female teachers and teachers at grade levels 11–13 also reported less negative collaboration.

Introduction

It is well documented that positive teacher-parent collaboration is important to enhance student learning and promote student well-being in school (Deng et al., Citation2018; Hattie, Citation2009; Niia et al., Citation2015). It is also well documented that students with behaviour difficulties tend to underperform academically and present psychosocial vulnerabilities including interpersonal problems and poor relationships with peers and teachers (Rocchino et al., Citation2017). Therefore, good collaboration and information exchange between teachers and parents is vital to understand the students’ problems at home and at school and through that be able to provide sufficient help and support. However, existing research on teacher-parent collaborative relationships indicate that externalizing or internalizing behaviour difficulties among students may challenge the relations and put them under strain (Miller, Citation2003). Discussing students’ behaviour difficulties with parents is perceived as stressful to teachers, and the difficulties may also cause teachers to doubt their classroom management and relationship-building competencies (Galloway & Goodwin, Citation1987; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2007).

Although school and family are different spheres, they also share common goals and responsibilities for the child’s growth, development, and wellbeing, as represented in Epstein’s (Citation1987) model of overlapping spheres. Here it is argued that the different demands and pressures on parents, children, and teachers in their representative spheres, need to be accounted for in order to understand, or change family-school relations. Positive parent-teacher collaboration is, according to Epstein, mutual beneficial; parents who are actively included in their child’s education feel more confident in supporting their child at home and rate the teacher more favourably on interpersonal and teaching skills, and support from parents also make teachers more effective and confident in their instructional practice. The quality of teacher-parent collaboration may also affect the teachers’ perceptions of the child. When teachers and parents share a positive relationship, teachers rate the students’ social skills more favourably and view the students’ externalizing difficulties as less problematic (Minke et al., Citation2014). However, in an American study, teachers report low-frequency and low-quality contact with 11% of parents in elementary school. The poor ratings are mainly due to family problems and/or social, academic and emotional problems among students (Stormont et al., Citation2013). Similar findings are presented in a Norwegian study, indicating that students’ behaviour problems may be partly caused by and partly causing poor teacher-parent collaboration (Nordahl & Drugli, Citation2016). When experiencing poor or challenging relationships with parents, teachers may be tempted to withdraw from collaborative efforts. It is therefore essential to support the teachers’ sense of mastery and efficacy in such situations to prevent the collaboration from collapsing (Westergård & Galloway, Citation2010). Hence, the present paper departs from a systemic perspective, and aims to discuss how factors at individual and organizational level affect the quality of teacher-parent collaboration when students exhibit behavioural problems.

A Systemic Perspective on Teacher-parent Collaboration

The connections among teachers, students and parents is an interactional and triangular relationship, based on what Bronfenbrenner (Citation2005) calls a N + 2 relationship. In this perspective, the relation between two parts is strongly affected by the relationship each has to a third part. In the teacher-parent relationship, the third part may be the student, but also the school organization comprising the routines, procedures and collective teacher efficacy that affects the quality of collaboration. According to Day (Citation1999), teachers are faced with norms of being and behaving as a professional “within personal, organizational and broader political conditions which are not always conducive to teacher development” (p. 13). A similar perspective is presented by Buehl and Beck (Citation2015) in their model of the teachers’ belief-practice relationship within a multi-level context of various internal and external factors (p. 74). The model identifies various factors at individual and organizational levels that serve as supports and hindrances for professional practice and development. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, and their beliefs about the students’ proficiencies, vulnerabilities, and needs are examples of internal factors, whereas parental, administrative, and collegial support are examples of external factors.

Building on these systemic approaches to understand teaching practice, our paper addresses teachers’ perceptions of the quality of collaboration with parents of students with behaviour difficulties and explores how these perceptions may be related to individual and organizational factors. Individual factors include gender, years of experience and additional training in psychology and/or special needs among teachers, and organizational factors include grade levels, the schools’ participation in mental health training programmes and collective teacher efficacy. Collective teacher efficacy encompasses the individual teacher’s perceptions of the schools’ or the teaching faculty’s joint ability and capacity to meet various demands and produce given attainments, whereas individual self-efficacy is more related to the teacher’s personal experiences and mastery expectations (Bandura, Citation1997; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2007). However, individual self-efficacy is closely related to and influenced by collective teacher efficacy through the establishment of norms and standards for professional action (Klassen, Citation2010). One such norm is the expectation towards teachers to possess high relational competencies and be able to build positive relationships with students and parents. Thus, the “relational-oriented teacher” has become a normative ideal for the teaching profession, and meeting this standard is therefore important for individual as well as collective teacher efficacy (Eriksen & Lyng, Citation2015). According to Sørlie and Torsheim (Citation2011), collective teacher efficacy clearly affects student behaviour and how teachers act as a group to deal with behaviour difficulties among students. The relationship between teacher efficacy and teachers’ management of students who present challenging behaviour is well documented, and much of the teachers’ feeling of being successful and efficacious in their profession depends on their ability to deal with behavioural difficulties and manage interpersonal dynamics (Gibbs & Powell, Citation2012; Guidetti et al., Citation2018; Tschannen-Moran et al., Citation1998). However, Guskey and Passaro (Citation1994), separate between internal and external factors in self-efficacy. Internal factors represent perceptions of personal skills and competence in student-teacher interaction, whereas external factors relate to factors beyond the control of the individual teacher, such as the students’ home settings. For example, Poulou and Norwich (Citation2002) found that the more the teachers attributed the students’ emotional and behavioural difficulties to the school environment and their own teaching practice, the more stressed and helpless they felt. Whereas the more they attributed the difficulties to the pathology of the individual student, the more efficacious they felt in dealing with the problems.

Internalizing and Externalizing Difficulties

In this paper, we apply the terms internalizing and externalizing behaviours to describe various degrees of behaviour difficulties among students. There is no clear consensus about the relationship between mental and emotional difficulties and behaviour difficulties, and the terms are somewhat overlapping reflecting their comorbidity in that students with behavioural difficulties may also suffer from mental problems such as anxiety and depression (Stacks & Goff, Citation2006). Externalizing difficulties are defined as negative behaviours that are directed toward the external environment, and encompass the full range of disruptive and destructive behaviour, from mild behaviour problems with attention and noncompliance to conduct problems in terms of severe verbal and physical aggression (Hukkelberg et al., Citation2019; Ogden, Citation2009). Internalizing difficulties or withdrawn behaviour are terms often used to describe students who are quiet, shy, worried and less socially active (Mjelve et al., Citation2019; Paulsen & Bru, Citation2016). Shyness and social withdrawal are overlapping concepts comprising personal traits as well as psychological, physiological/genetic, and social aspects, causing students to remove themselves from opportunities for social interaction (Li et al., Citation2016; Lund, Citation2016; Totura et al., Citation2009). In sum, behavioural difficulties vary in severity, scope and duration, and the degree of challenging behaviour is assessed based on the level and frequency of difficulties and the potential need for additional services (Minke et al., Citation2014). The key criterion for defining behaviour as problematic is the extent to which the behaviour inhibits or negatively interferes with the student’s learning situation and social relationships. Therefore, threshold judgements largely depend on whether teachers and/or parents find the student’s behaviour disturbing or destructive (Galloway & Goodwin, Citation1987).

The Contextual and Relational Dependency of Behaviour Difficulties

According to Kostøl and Mausethagen (Citation2011), behaviour difficulties are a relational and contextual phenomenon that is largely dependent on and emerges from the quality of relationships to teachers and peers and the degree to which the students’ needs for academic and social support are met in school. Thus, behavioural difficulties are identified when the students’ behaviour largely deviates from present norms, rules and expectations, based on the current context and the students’ age and developmental stage. In this perspective, the students’ behaviour is not a constant, but something that is vastly dependent on the classroom interactions and relationships between teachers, parents and students (Sidorkin & Bingham, Citation2004). For example, a Chinese study of stress-related risk identified exposure to stressors at school and home as a direct cause of externalizing behaviour (Brady et al., Citation2014). Also, the contextual dependency relates to the match between the students’ capacity or motivation to behave in a certain way and the environment’s expectations and demands. Often, the student may behave differently at school and at home/in leisure activities, making it difficult for teachers and parents to reach a common understanding of the students’ problems or needs. A meta-analysis addressing the cross-informant agreement on students’ social competence identifies moderate correspondence in teacher-parent ratings (Renk & Phares, Citation2004). In the American Head Start programme, teachers reported significantly lower levels of externalizing behaviour among girls than what parents did, and the teachers also reported significantly higher levels of internalizing difficulties for both genders than what parents did (Stacks & Goff, Citation2006). In addition, it is vital to establish a teacher-parent consensus about what is positive and appropriate behaviour and communicate these standards and expectations to the child both at school and home (Hill & Taylor, Citation2004).

The Present Study

Based on the theoretical perspectives and research presented above, the benefits of positive parent-teacher collaboration are made clear. Building on a systemic perspective, our study aimed to explore what factors at an individual and organizational level that may be related to variances in teachers’ perceived quality of collaboration with parents of students with behavioural difficulties. The perceived quality was measured through the degree of conflicts with parents, parental withdrawal from collaboration and challenges in teacher-parent collaboration. The individual teacher factors were teacher self-efficacy, gender, years of experience and additional training in psychology and/or special needs, and the organizational factors were grade levels, collective teacher efficacy and the schools’ participation in mental health training programmes.

Based on this, the main research question of the present study was: Which individual and organizational factors may affect teachers’ perceived quality of parental collaboration when students exhibit externalizing or internalizing behaviour?

Materials and Methods

Sampling, Sample Characteristics and Data Collection Procedures

The data was derived from a national survey of K-12 teachers in the western part of Norway. The survey was distributed in April–June 2012, and a total (n) of 771 teachers responded. Altogether, teachers from 51 schools took part in the survey, and the schools were randomly selected based on a register of all public K–12 schools in Norway. The sample was stratified to ensure representativeness of the sample according to grade level (1–7, 8–10 and 11–13) and school size: small (S), <100 students; medium (M), 100–300 students; and large (L), >300 students. The sample frame included three different counties with different demographic characteristics and student population sizes. Thus, the sample was not representative of the actual student populations within each county. The sample is presented in .

Table 1. Number of schools in different categories of the survey sample.

The principals at each school gave their informed consent for the school to participate and provided access to the teachers’ e-mail addresses for individual distribution. The teachers received a link to the survey and were also given a digital information letter to ensure their informed consent. The response rate was 49% (N = 1575). The main sample characteristics; gender, years of experience, grade levels, participation in mental health training programmes, and additional training in psychology and/ or special needs, are presented in .

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

Ethics

The survey was conducted in line with the Norwegian Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Humanities, Law and Theology (De nasjonale forskningsetiske komiteene, Citation2016), regarding the protection of privacy and informed consent. The project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). All participants were adults who gave their free and informed consent to participate, and no sensitive information was collected. Although it was not possible to withdraw from the study after the survey had been submitted, the participants had the opportunity to skip individual items.

Measures

The survey instrument comprised a total of 13 items and was constructed based on individual items from the pre-validated scales, the Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy Scale and the Norwegian Teacher Self-efficacy Scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2007). The items from these scales were supplemented with some self-designed items to better cover the research question of the study and capture teachers’ perceptions of negative collaboration with parents of students with externalizing and internalizing behaviour. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree). From the Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy Scale, we adopted three items. The first two were: (1) “At this school, we are able to create a safe and inclusive atmosphere even in the most difficult classes”; and (2) “As teachers of this school, we can get even the most difficult pupils engaged in their schoolwork”. In both items, the word “difficult” was replaced with “challenging” to match the Norwegian translation. In addition, we split and adjusted the third item: (3) “At this school, we have a common set of rules and regulations that enables us to handle disciplinary problems successfully”. This yielded two replacement items for it: (3a) “At this school, we have a common set of rules and regulations that enables us to handle students with externalizing behaviour in a good way”; and (3b) “At this school, we have a common set of rules and regulations that enables us to handle students with internalizing behaviour in a good way”. From the Norwegian Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (NTSES) we adopted two out of four items from the subcategory “Cooperate with Colleagues and Parents”. These items were “I cooperate well with most parents” and “I collaborate constructively with parents of students with behavioural problems”. The latter was adjusted and split into two items (a) “I collaborate constructively with parents of students with externalizing behaviour” and (b) “I collaborate constructively with parents of students with internalizing behaviour”.

The six self-designed items were: (1) Collaboration with parents of students with externalizing behaviour is very challenging to me, (2) Collaboration with parents of students with internalizing behaviour is very challenging to me, (3) My relation to parents of students with externalizing behaviour is conflictual, (4) My relation to parents of students with internalizing behaviour is conflictual, (5) I experience that parents of students with externalizing behaviour withdraw from their collaborative responsibilities and (6) I experience that parents of students with internalizing behaviour withdraw from their collaborative responsibilities.

Analyses

All items were subject to an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) that identified the three main dimensions (scales) presented in . The analysis was performed as a principal component analysis (PCA) using a varimax rotation with a Kaiser normalization due to the assumption of a correlation between the variables. The analysis revealed three components with eigenvalues > 1. A three-component solution explained 61.7% of the total variance. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was .691, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached statistical significance (p < .001). The scales all reached a satisfying reliability value as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α > .700).

Table 3. Principal component analysis with items from the perceived collective teacher efficacy scale, the Norwegian teacher self efficacy scale and self-designed items (Varimax Rotation with Kaiser Normalization) (n = 771).

Factor 1 comprised items concerning perceived levels of conflict and withdrawal and was labelled Negative Teacher-Parent Collaboration (NTPC). Factor 2 comprised items related to perceived constructive collaboration with parents, and the items were all based on the Norwegian Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2007). This factor was labelled Teacher Self-Efficacy in Parental Collaboration (TSEPC). Finally, Factor 3 comprised items concerning collective rules and effectiveness enabling the teachers to deal with behavioural challenges, and the items were all based on the Collective Teacher Efficacy Scale (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2007). This factor was labelled Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy (PCTE). To address the research question concerning teachers’ perceived quality of parental collaboration when students have behavioural difficulties (dependent variable), the factors were subject to ANOVA tests with individual-level factors such as gender, years of experience and additional education in psychology or special needs and organizational-level factors such as grade levels and participation in mental health training programmes as independent variables. In addition, to further explore the potential relationship between variables, a multiple regression analysis with the factor NTPC as dependent variable was conducted. The independent variables were gender, grade level, additional education and the factors PCTE and TSEPC.

Results

Descriptive statistics provided information regarding the percentage distribution of answers for the different survey items. The results are presented in , according to the three factors identified in .

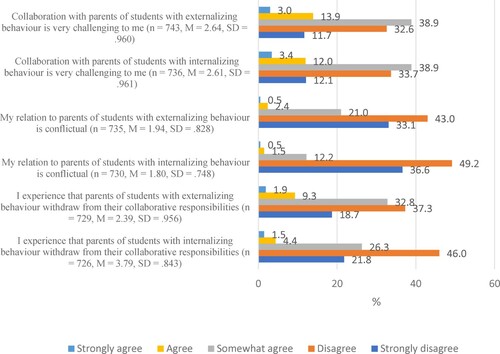

Figure 1. Percentage distribution of answers on items comprising the factor negative teacher-parent collaboration (NTPC).

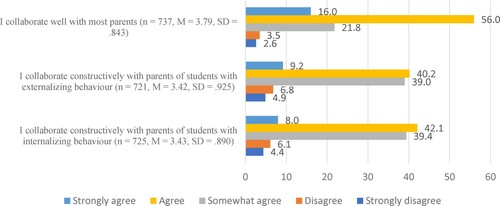

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of answers on items comprising the factor teacher self-efficacy in parental collaboration (TSEPC).

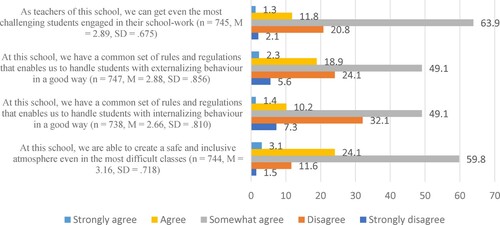

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of answers on items comprising the factor perceived collective teacher efficacy (PCTE).

The results in indicate that 15–17% of the teachers found the collaboration with parents very challenging when the students had behavioural difficulties. There was little difference here based on whether the student showed internalizing or externalizing behaviour. However, it seems like collaboration with parents was more conflictual when students had externalizing behaviour, and that teachers perceived that parents more often withdrew from their collaborative responsibilities in such cases. Still, shows that there were no differences in how teachers perceived their ability to collaborate constructively with parents regardless of the student’s type of behaviour difficulty. Furthermore, indicates that schools had better routines and procedures to deal with externalizing rather than internalizing behaviour.

The ANOVA tests related to variables at the individual level (gender, years of experience and additional training in psychology and/or special needs) identified no significant differences in scores based on years of experience for all three factors. However, there were significant between-group differences based on additional training and gender on the scale Teacher Self-Efficacy in Parental Collaboration (TSEPC). Teachers with additional training in psychology or special needs reported significantly higher scores here (M = 11.0, SD = 2.19) than teachers without such education did (M = 10.5, SD = 2.50), F(1, 692) = 5.78, p = .016. Despite reaching statistical significance, the actual difference in mean scores was small, with an effect size of .01 (eta-squared = .008). Moreover, male teachers (M = 10.30, SD = 2.36) reported significantly lower scores on the TSEPC scale than female teachers did (M = 10.97, SD = 2.42, F(1, 702) = 8.86, p = .003). Still, the eta-squared value was .01, indicating a very small effect size.

The ANOVA tests related to variables at the organizational level (grade levels, collective teacher efficacy and participation in mental health training programmes) identified no significant differences based on the schools’ participation in mental health training programmes. However, there were statistically significant differences based on grade levels on all three factors, as identified by post-hoc comparisons using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. The results are presented in .

Table 4. Significant findings from one -way ANOVA on three scales (dependent).

The results in indicate that teachers at Grade Levels 11–13 reported significantly lower score levels on all three factors. This means that they reported lower levels of negative teacher-parent collaboration but also lower levels of individual and collective teacher efficacy than what teachers at other grade levels did. A correlational analysis (Pearson’s r) identified a significant weak positive covariate relationship between collective efficacy and individual efficacy (r = .217, p < .001). No such relationship was found between perceived collective teacher efficacy and negative collaboration.

To further explore the potential relationship and interdependency among variables, multiple regression analyses were conducted with the factor Negative Teacher-Parent Collaboration (NTPC) as dependent variable and teacher gender, grade level, additional training and the scales Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy (PCTE) and Teacher Self-Efficacy in Parental Collaboration (TSEPC) as independent variables. The categorical variable of grade was recoded into a dichotomous variable with Grades 1–10 at one level and Grades 11–13 at the other, due to the previously identified differences between teachers in Grades 1–7 and 8–10 versus Grades 11–13. The results are presented in .

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis for negative teacher-parent collaboration.

The findings in show that grade levels, teacher gender and teacher self-efficacy made a unique significant contribution to explaining the variance in negative collaboration. However, the overall model of negative teacher-parent collaboration accounted only for 2.5% of the variance, R-squared = .025, F(5, 685) = 3.50, p < .01. This indicates that several other variables than the ones included in the model, account for variances in perceived negative collaboration with parents of students with internalizing or externalizing behaviour.

Summary of Findings

The descriptive statistics showed that teachers perceived the collaboration with parents of students with externalizing behaviour as more conflictual and negative and the school seemed to have better routines to deal with internalizing behaviour. Analyses of variance aimed to identify factors at individual and organizational level relevant to explain variance in scores on the three scales Negative teacher-parent collaboration (NTPC), Perceived collective teacher efficacy (PCTE), and Teacher self-efficacy in parental collaboration (TSEPC). Among individual level factors, additional training and gender were significant variables to explain variance in TSEPC. Among organizational level factors, grade level was significant to predict variance on all three scales. Post hoc tests identified that teachers at grade level 11–13 reported lower levels of conflictual collaboration with parents, but also lower levels of collective and individual teacher self-efficacy than teachers at grade level 1–10 did. Finally, regression analysis identified individual teacher efficacy, grade level, and gender as significant to explain variance in negative teacher-parent collaboration.

Discussion

The presented study set out to explore which individual and organizational factors may affect teachers’ perceived quality of parental collaboration when students exhibit externalizing or internalizing behaviour. The descriptive statistics indicated that collaboration with parents was perceived as more conflictual and negative when students showed externalizing behaviour. Moreover, the schools seemed to have better routines to deal with externalizing behaviour rather than internalizing behaviour, but the survey-items did not gather what kinds of routines these may be. Research shows that internalizing difficulties among students often remain undetected or unattended to, and according to Zee et al. (Citation2016), students with internalizing behaviour more often go undetected or ignored in class. Their findings also indicate that although externalizing and internalizing behaviour have equal widespread negative consequences for the students’ academic learning and social relationships, externalizing difficulties affect teachers’ perceived efficacy more negatively. This impact is most salient if the teachers attribute the students’ difficulties to the school environment or to their own teaching practice, rather than to the individual student or the family environment (Poulou & Norwich, Citation2002).

According to Nordahl (Citation2003), teachers form a construction of how the parents are, based on the student’s behaviour, and parents of students with academic, social or behavioural difficulties report more negative collaboration with the school. This is likely to reproduce positive and negative interaction patterns and mirror the complexity of the N + 2 relationships (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005). Our study identified significantly higher levels of self-efficacy in parental collaboration among teachers with additional education in psychology or special needs. It can be logically reasoned that such additional education may serve as an influence in enhancing teachers’ competence and understanding of behavioural difficulties among students, and by that, enhance the likelihood of more positive collaboration with parents.

Still, behavioural difficulties among students often put the teacher-parent collaboration under strain (Miller, Citation2003; Nordahl & Drugli, Citation2016; Stormont et al., Citation2013), and collaboration with parents of students with externalizing difficulties are more frequently dominated by negative contact (Eriksen & Lyng, Citation2015). Thus, in order to obtain a good teacher-parent relationship, it is important that the school establish routines for positive contact and stress the teachers’ responsibilities to actively convey positive messages about the child, even if there are behavioural challenges. Often, the constant negative messages about their child may cause parents to feel guilt or shame and, in turn, may influence them to take a defensive position towards the teacher. Seeing their child struggling at school evokes a special vulnerability in parents, making then either withdrawn, aggressive or defensive (Nordahl & Drugli, Citation2016). This negative interaction may be further aggravated if the school lacks good routines and procedures to deal with externalizing difficulties in a good way, and thus, the school is less able to provide support to the teachers, students and parents.

Measures of such perceived support was covered by the Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy scale in our study. Existing research show that collective and individual efficacy are strongly related constructs in which collective efficacy affects the individual teachers’ beliefs of their capacity to positively affect the behaviour of students (Gibbs & Powell, Citation2012; Guidetti et al., Citation2018; Sørlie & Torsheim, Citation2011). Our results supported this correlation, identifying a significant but weak positive covariate relationship between the constructs of collective and individual teacher efficacy.

However, the regression analysis did not identify collective teacher efficacy as a significant predictor for variance in negative collaboration. What did seem to matter was teacher self-efficacy, gender and grade level. One of the dimensions in the teacher self-efficacy scale is cooperating (with parents and colleagues), and according to Skaalvik and Skaalvik (Citation2007), gender and collective teacher efficacy are both significant predictors for variance in teacher scores on this dimension. Gender differences were also identified by the ANOVA results in our study, in which female teachers reported significantly less negative collaboration with parents than male teachers did. Prior research conducted by Drugli (Citation2013) show that externalizing and internalizing problems among students are associated with lower levels of closeness and higher levels of conflict with teachers of both genders, even though female teachers report significantly lower levels of conflict than what their male colleagues do. Nonetheless, several studies identify higher levels of emotional distress among female teachers than among male teachers due to students’ behaviour difficulties (Antoniou et al., Citation2006; Chaplain, Citation2008; Klassen & Chiu, Citation2010). However, these studies do not focus on how this stress may affect teachers’ collaboration with parents. Thus, our findings signify the need to learn more about how the triangular relationship between teachers, students, and parents is related to perceived quality of teacher-parent collaboration when students exhibit behavioural difficulties.

Finally, our study showed that teachers at higher grade levels reported less negative collaboration with parents. There is very little research to support these findings. In Norway, there is no mandatory collaboration between teachers and parents after the students reach the age of majority (18 years). Thus, at Grade Levels 12 and 13, there may be less contact between the school and home. However, the frequency is not necessarily related to the quality aspects. A study of the frequency and quality of teacher-parent collaboration in elementary school identified that teachers rated 71% of the collaborative relationships as low in frequency but high in quality, whereas 18% were rated as high in both. Low ratings were mainly due to family problems and/or behavioural or academic problems among students (Stormont et al., Citation2013).

Conclusions

Altogether, the presented findings support previous research on the relationship between collective and individual teacher efficacy in the field of parental collaboration and identify individual efficacy as more important than collective efficacy to explain variance in perceived quality of teacher-parent collaboration. Moreover, the study identified additional training in psychology or special needs as significant to teacher self-efficacy. Even though collective teacher efficacy was not a significant predictor for variance in negative collaboration, it may have a mediating effect through its correlation with teacher self-efficacy. The identified significance of grade level and gender, calls for a systemic perspective on teacher-parent collaboration, paying more attention to the relative impact of individual and organizational factors that may serve as support and hindrances for positive teacher-parent collaboration when students show behavioural problems. As far as we know, few studies have compared the quality of teacher-parent/home-school collaborations in primary school, lower, and upper secondary schools, and even fewer studies have coupled this with the presence of behavioural difficulties among students. Further research through multi-level analysis is needed to explore these differences more fully.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the variables included in the model only explained a small part of the total variance in negative teacher-parent collaboration. This means that there are several individual and organizational factors relevant to the quality of collaboration, not accounted for. Second, we were not able to compare scores on collaboration with parents in general to scores on collaboration with parents of students with behavioural difficulties. Thus, we could not identify challenges due to the difficulties. However, we could identify variances in scores on externalizing versus internalizing difficulties, even if only at a descriptive level. Third, we were not able to differentiate between moderate problems and more severe difficulties, as the items only asked about externalizing and internalizing behaviour. Fourth, not all behaviour difficulties were classified as special educational needs. This caused variance in how teacher-parent collaboration was organized and the extent to which inter-professional support was required and provided. This may have affected the teachers’ perceptions of the quality of collaboration. Finally, there is great variance internationally between school systems and how teacher-parent collaboration is legally regulated and formally organized. Also, results from different international studies are not necessarily immediately transferable to a Norwegian context, due to differences in cultural norms and understandings of behavioural difficulties. Still, our paper includes a broad perspective on behavioural difficulties as contextually and relationally dependent, including Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) interactional and triangular relationship among teachers, students, and parents. The findings may therefore be generalizable to international contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all teachers who took their time to participate in the study. We are also very thankful to our former colleague, associate professor Aina Sætre, who took part in the data collection and construction of the survey. Also, thanks to professor Rune Kvalsund for valuable comments to the manuscript. The survey was supported by grants from The Research Council of Norway through the project “Teachers’ and Students’ Roles in Education” at Volda University College [project number 75019].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antoniou, A. S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A. N. (2006). Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 682–690. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690213

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Brady, S. S., Winston, W., & Gockley, S. E. (2014). Stress-related externalizing behavior among African American youth: How could policy and practice transform risk into resilience? Journal of Social Issues, 70(2), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12062

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory. In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 106–173). Sage Publications.

- Buehl, M. M., & Beck, J. S. (2015). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teachers’ practices. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. pp. 66–84). Routledge.

- Chaplain, R. P. (2008). Stress and psychological distress among trainee secondary teachers in England. Educational Psychology, 28(2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701491858

- Day, C. (1999). Developing teachers: The challenges of lifelong learning. Falmer Press.

- De nasjonale forskningsetiske komiteene. (2016). Forskningsetiske retningslinjer for samfunnsvitenskap, humaniora, juss og teologi [Guidelines for research ethics in the social science, humanities, law and theology]. https://www.etikkom.no/forskningsetiske-retningslinjer/Samfunnsvitenskap-jus-og-humaniora/

- Deng, L., Zhou, N., Nie, R., Jin, P., Yang, M., & Fang, X. (2018). Parent-teacher partnership and high school students’ development in mainland China: The mediating role of teacher-student relationship. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38(1), 15–31.https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2017.1361904

- Drugli, M. B. (2013). How are closeness and conflict in student–teacher relationships associated with demographic factors, school functioning and mental health in Norwegian schoolchildren aged 6–13? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656276

- Epstein, J. L. (1987). Toward a theory of family-school connections: Teacher practices and parent involvement. In K. Hurrelmann, F.-X. Kaufmann, & F. Lösel (Eds.), Prevention and intervention in childhood and adolescence, 1. Social intervention: Potential and constraints (pp. 121–136). Walter De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110850963.121

- Eriksen, I. M., & Lyng, S. T. (2015). Skolers arbeid med elevenes psykososiale miljø. Gode strategier, harde nøtter og blinde flekker. NOVA rapport 14/2015 [Schools’ work with students’ psychosocial environment. Good strategies, hard nuts and blind spots. NOVA report 14/2015]. http://www.hioa.no/Om-HiOA/Senter-for-velferds-og-arbeidslivsforskning/NOVA/Publikasjonar/Rapporter/2015/Skolers-arbeid-med-elevenes-psykososiale-miljoe

- Galloway, D., & Goodwin, C. (1987). The education of disturbing children: Pupils with learning and adjustment difficulties. Longman.

- Gibbs, S., & Powell, B. (2012). Teacher efficacy and pupil behaviour: The structure of teachers’ individual and collective beliefs and their relationship with numbers of pupils excluded from school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 564–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02046.x

- Guidetti, G., Viotti, S., Bruno, A., & Converso, D. (2018). Teachers’ work ability: A study of relationships between collective efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S157850

- Guskey, T. R., & Passaro, P. D. (1994). Teacher efficacy: A study of construct dimensions. American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 627–643. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312031003627

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. (2004). Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00298.x

- Hukkelberg, S., Keles, S., Ogden, T., & Hammerstrøm, K. (2019). The relation between behavioral problems and social competence: A correlational meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2343-9

- Klassen, R. M. (2010). Teacher stress: The mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. The Journal of Educational Research, 103(5), 342–350. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=afh&AN=51601601&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903383069

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

- Kostøl, A. K., & Mausethagen, S. (2011). Relasjonsorientert praksis og stabile læringsfellesskap : kontekstuelle og relasjonelle forhold i klasserom på skoler med lite atferdsproblemer [Relation-oriented practice and stable learning communities: Contextual and relational aspects of classrooms at schools with little behavioural difficulties]. Paideia, 1(2). http://hdl.handle.net/10642/1150

- Li, Y., Zhu, J.-J., Coplan, R. J., Gao, Z.-Q., Xu, P., Li, L., & Zhang, H. (2016). Assessment and implications of social withdrawal subtypes in young Chinese children: The Chinese version of the child social preference scale. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 177(3), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2016.1174100

- Lund, I. (2016). ‘When words don’t come easily’: Personal narratives from adolescents experiencing shyness as an emotional and behavioural problem in the school context. British Journal of Special Education, 43(4), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12151

- Miller, A. (2003). Teachers, parents and classroom behaviour. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Minke, K. M., Sheridan, S. M., Kim, E. M., Ryoo, J. H., & Koziol, N. A. (2014). Congruence in parent-teacher relationships. The Elementary School Journal, 114(4), 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1086/675637

- Mjelve, L. H., Nyborg, G., Edwards, A., & Crozier, W. R. (2019). Teachers’ understandings of shyness: Psychosocial differentiation for student inclusion. British Educational Research Journal, 45(6), 1295–1311. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3563

- Niia, A., Almqvist, L., Brunnberg, E., & Granlund, M. (2015). Student participation and parental involvement in relation to academic achievement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904421

- Nordahl, T. (2003). Makt og avmakt i samarbeidet mellom hjem og skole: en evaluering innenfor Reform 97 [Power and powerlessness in the home-school collaboration: An evaluation within Reform 97] (Vol. 13/2003).

- Nordahl, T., & Drugli, M. B. (2016). Samarbeidet mellom hjem og skole [Home-school collaboration]. https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/samarbeid/hjem-skole-samarbeid/samarbeidet-mellom-hjem-og-skole/

- Ogden, T. (2009). Sosial kompetanse og problematferd i skolen [Social competence and problem behaviour in the school] (2nd ed.). Gyldendal akademisk.

- Paulsen, E., & Bru, E. (2016). De stille elevene [Quiet students]. In E. Bru, E. C. Idsøe, & K. Øverland (Eds.), Psykisk helse i skolen [School mental health] (pp. 28–44). Universitetsforlaget.

- Poulou, M., & Norwich, B. (2002). Cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses to students with emotional and behavioural difficulties: A model of decision-making. British Educational Research Journal, 28(1), 111–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920120109784

- Renk, K., & Phares, V. (2004). Cross-informant ratings of social competence in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.004

- Rocchino, G. H., Dever, B. V., Telesford, A., & Fletcher, K. (2017). Internalizing and externalizing in adolescence: The roles of academic self-efficacy and gender. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 905–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22045

- Sidorkin, A. M., & Bingham, C. (2004). No education without relation (Vol. 259). Peter Lang.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

- Sørlie, M.-A., & Torsheim, T. (2011). Multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher collective efficacy and problem behaviour in school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2011.563074

- Stacks, A. M., & Goff, J. (2006). Family correlates of internalizing and externalizing behavior among boys and girls enrolled in Head Start. Early Child Development and Care, 176(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443042000302609

- Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., David, K. B., & Goel, N. (2013). Latent profile analysis of teacher perceptions of parent contact and comfort. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000004

- Totura, C. M. W., MacKinnon-Lewis, C., Gesten, E. L., Gadd, R., Divine, K. P., Dunham, S., & Kamboukos, D. (2009). Bullying and victimization among boys and girls in middle school: The influence of perceived family and school contexts. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(4), 571–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608324190

- Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202

- Westergård, E., & Galloway, D. (2010). Partnership, participation and parental disillusionment in home–school contacts: A study in two schools in Norway. Pastoral Care in Education, 28(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2010.481309

- Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teachers’ self-efficacy in relation to individual students with a variety of social-emotional behaviors: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(7), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000106