ABSTRACT

Over the last 50 years, the school subject of history has increasingly been described as a subject about interpretation and multi-perspectivism. Discussing the subject this way might require a specific view of the subject’s nature. This study investigates the genre position and epistemic cognition of Swedish upper secondary school history teachers. The study uses a questionnaire to which 375 teachers responded and the results show that in relation to the theoretical framework, more than one half of the teachers demonstrate epistemic inconsistency, putting teachers’ ability to voice their epistemic views and/or theoretical assumptions into question. The age of teachers is the only studied structural category that appear to impact the teachers’ views of the subject, with older teachers being more optimistic about a true correspondence between the past and history, than younger teachers. The study also shows that there is not a straightforward relationship between genre position and epistemic cognition.

Introduction

In this article, the views about the nature of history and historical knowledge held by Swedish history teachers in upper secondary school are investigated in relation to theoretical assumptions about epistemic cognition. In the steering documents for Swedish history teaching, as well as in the steering documents for history teaching in many other countries, history is viewed as a subject that is based on interpretation, and therefore, contains multiple perspectives (see e.g., Ammert, Citation2013; Mathis & Parkes, Citation2020; Stoel et al., Citation2017; Wendell, Citation2018). Related to how curricula, in the last 50 years, have come to emphasise historical thinking competencies and the nature of historical knowledge, researchers interested in epistemic issues of history teaching have specifically pointed to these matters as important for history teachers to understand.

As Mathis and Parkes have put it: “To understand historical thinking competencies, history teachers need not only to have subject matter knowledge in terms of substantive content and procedural concepts of history but also knowledge of the epistemology of history as a discipline” (Mathis & Parkes, Citation2020, p. 196). I subscribe to this notion and this article is therefore concerned with this issue, although more openly. Assessing and critically discussing theoretical assumptions in the field, the questions I will address are: What do Swedish upper secondary school history teachers regard as being the nature of the subject they are teaching, and how do they conceptualise the relationship between the past itself and the historical narratives about this past? Does the position they take regarding the nature of the subject also impact how they reason about how knowledge of specific events in the past is produced? By engaging in this research, I also intend to shed some light on how theoretical claims in previous research may be understood in relation to teachers’ own view of the realities of teaching. These research questions will be addressed utilising a questionnaire that was answered by 375 Swedish teachers who teach history in upper secondary schools.

Given how the syllabus for history teaching in Sweden is formulated, the issue of how teachers reason about what kind of knowledge they are teaching comes to the fore. In the very first paragraph of the Swedish syllabus for history in upper secondary schools (gymnasieskola), the narrative and interpretative nature of the subject is described: “Women and men throughout the ages have created historical narratives to interpret reality and shape their surroundings” (Lgy11, English version, Citation2011, p. 208). As part of the aim of the subject, the students are also supposed to develop their ability to “reflect over their own and other’s use of history in different contexts and from different perspectives, and use historical concepts to analyse how historical knowledge is organised, created and used” (Lgy11, English version, Citation2011, pp. 208–209).

The Swedish syllabus for history teaching in upper secondary schools thus particularly addresses how history is used in society, making the Swedish case particularly interesting as the nature of historical knowledge is forwarded as a contingent construction, and it begs the question: Do Swedish teachers’ view of the nature of history match this, at least in a sense, constructionist view of historical knowledge?

Previous Research

The theoretical implications of the narrative structure of historical inquiry have been debated for decades, with much focus on Hayden White’s seminal work Metahistory (Carr, Citation1986; White, Citation1973). This has also been debated in regard to history education for quite some time (see e.g., Levisohn, Citation2010; Seixas, Citation2000; Straub, Citation2005).

In a number of studies conducted in the last decade, Swedish researchers have shown considerable interest in how teachers conceptualise history teaching; how they consider the subjects raison d’être (Alvén, Citation2017; Berg, Citation2014; Hansson, Citation2010; Lilliestam, Citation2013; Lozic, Citation2010; Nygren, Citation2009; Persson, Citation2017; Thorp, Citation2015; Wendell, Citation2018). Many of these studies demonstrate that teachers consider the subject of history to be very complex and hard to define. They also indicate that teachers approach the subject in very different ways and that they often have a hard time deciphering the intentions of steering documents, particularly in relation to their own view of the subject’s main objectives. Research from other parts of Europe shows similar results regarding student teachers. Virta (Citation2001) and McCrum (Citation2013a, Citation2013b) have shown that student teachers in Finland and England often have very different views about what history is and what it is good for; and they do not always seem to be able to convey a coherent view of the subject’s epistemological basis.

Most of these studies have had a specific interest in the contrast between a view of history (and history teaching) that is related to a traditional way of teaching history with a strong focus on historical facts, and a more experiential and empathetic relation to history. However, they generally do not have a specific interest in the question of the epistemological stances of teachers’ and/or student teachers’, their view of the relationship between the past and history.

However, McCrum’s study of student teachers (Citation2013a, Citation2013b) is more related to epistemology. McCrum shows how student teachers have a rigid and traditional conceptualisation of the epistemological nature of their subject, with a very empirically-based view of the essence of the subject. The student teachers used puzzle metaphors to explain their view of what historians do. Very few of the student teachers described the work of historians in terms of interpreting or sense-making. In a Swedish context, Thorp (Citation2015) has shown similar results in a smaller study on teachers’ interpretation of historical texts.

VanSledright and Reddy (Citation2014) have also shown that prospective history teachers in the USA appear to have difficulty coordinating their epistemic position. According to the authors, this problem could be addressed by ensuring that prospective history teachers get to work with historical sources and develop a vocabulary to talk about epistemology to make sure they are aware of their own position. Given how this awareness is almost taken for granted in instructions for history teaching and in syllabi, these findings highlight the importance of researching the ways that teachers acknowledge their own epistemic position.

Most research on multi-perspectivity in history teaching is related to the idea of history as a tool for gaining an understanding for one’s own culture(s) and the culture(s) of others. Most historians also tend to point to a change in history teaching in the latter part of the twentieth century during which time the subject changed from being facts orientated, via problem orientated to competence orientated, which is more in line with multi-perspectivity (von Borries, Citation2001). The perceived ability of history teaching to ensure that students of the subject gain a grander perspective of culture has also been highlighted as a somewhat new and required direction in history teaching (see e.g., Eliasson & Nordgren, Citation2016; Nordgren, Citation2006). Much of the historical research on the development of history education also shows that tradition has a strong hold of the subject, that changes are gradual, and that these changes tend to generate debates that persist for decades (Barton, Citation2012; Cubitt, Citation2007; Elmersjö, Citation2017; Persson, Citation2019).

However, some research has also been conducted on the epistemological complexity of multi-perspectivity (see e.g., Parkes, Citation2011; Stradling, Citation2003). This research shows how the integration of multi-perspectivity in history teaching is very time-consuming and that teachers have problems in achieving such teaching while still maintaining their perceived obligation to teach “true history” (Nygren et al., Citation2017; von Borries, Citation2001). Most ideas about so-called perspective recognition in history teaching are focused on a “true narrative” in which students are supposed to recognise the perspective of the people in the narrative, not the perspective of the narrative itself (see e.g., Levstik & Barton, Citation2011).

Theoretical Assumptions

Epistemic cognition, understood as the cognitive ability to assess the criteria, limitations, and certainty of knowing, defines how an individual understands knowledge, its applications, and its acquisition. With specific reference to history, epistemic cognition impacts how an individual approaches studying the past, and how they make sense of historical texts, narratives, and other source materials. Educators in the field of history are by no means exempt from processes of historical cognition. Thus, what they choose to teach, and how, is probably very much influenced by their implicit understanding of epistemic cognition (VanSledright & Reddy, Citation2014).

One previously developed model of epistemic cognition, the Levels of Epistemic Understanding Model, developed by Kuhn and Weinstock (Citation2002), establishes a continuum with four categories that individuals move through as they modify their understanding of the relationship between knowledge and reality, termed realist, absolutist, multiplist, and evaluativist (Maggioni et al., Citation2009. See also King & Kitchener, Citation2002). Although they imply a progression of knowledge, this categorisation should not be understood as linear, in which knowledge somehow “improves” as a person moves along the continuum. However, the view of the relationship between assertions and reality increases in complexity from a very simple relationship in the realist category (assertions are seen as copies of reality), to a much more complex notion of this relationship in the evaluativist category (assertions are seen as judgements that can be evaluated following certain rules). This also suggests that there is a change in criticality, from an objectivist view that do not indicate a need for critical assessment in the realist and absolutist categories, towards a subjectivist view where there is a perceived need to critically examine all knowledge claims, associated with the multiplist and evaluativist categories.

One way of connecting these concepts of epistemic cognition to the subject of history, while also enabling a deeper understanding of how teachers see the nature of their subject, is to study the genre positions of historians, as suggested by Alun Munslow and Keith Jenkins. In their view, all historical research can be considered to be written from different genre positions, specifically, a reconstructionist, constructionist, and deconstructionist position (see e.g., Elmersjö et al., Citation2017; Jenkins & Munslow, Citation2004; McCrum, Citation2013b; Parkes, Citation2013).

The reconstructionist position in historical scholarship is characterised by many of the epistemological assumptions associated with “traditional” history teaching; the belief that the past has an innate meaning that historians (and students of history) are able to discover. It is a genre devoid of theory. This position entails the belief that historical truth can be found and also taught, but also that this truth can be accurately represented by a narrative.

The constructionist position is mainly characterised by the notion that the past and history are diametrically different things, and that the relationship between them is complex. Theory is seen as the bridge across the gap between the past itself, and the histories about it. However, this gap is seen as unbridgeable by historians and teachers who hold a deconstructionist position. From this position, all meaning is applied to history by the needs of the historian/teacher in the present, or by the needs of the society in which they are writing/teaching.

The genre position of the teachers may be assumed to have some impact on how they teach their subject with regard to multi-perspectivity. Because after all, why would a teacher want to teach history as if there were multiple and equally true narrative interpretations if they thought of history as being the same as the past, and as having an innate meaning? However, this is an empirical question that is not addressed in this article and it needs further research, involving classroom studies.

In this article I will utilise both genre position and epistemic cognition as theoretical analytical tools to try to address the above questions, but in different ways. Genre positions will be utilised to address whether or not teachers identify a gap between the past and history, while epistemic cognition will be utilised to identify the way they conceptualise how we can know anything about certain events in the past, and also what it means “to know”. These analytical tools may be assumed to overlap, with constructionists (and perhaps deconstructionists) being more aligned with an evaluativist position, but this is an empirical question that is addressed in the following. However, since these analytical tools are devised to understand how a person understands the epistemology of history, and not particularly how they think about how history could be taught, I will also utilise empirical data to critically assess these theoretical constructs and their ability to frame teachers’ ideas about history and its relation to history teaching. An open question regarding this would be: Does these theoretical assumptions capture the complexity of epistemology when it comes to not only think about history, but also teach it?

Method

In the autumn of 2019, a questionnaire was distributed to 1,000 history teachers in Swedish upper secondary schools. The Swedish statistics agency, Statistics Sweden (Statistiska centralbyrån, SCB), administered the questionnaire and randomly selected the 1,000 participants from their database of teachers who had been assigned to teach history in Swedish upper secondary schools for at least the equivalent of 10% of their teaching schedule during the previous academic year (2018/19). 375 teachers responded to the questionnaire (i.e., 37.5%).

Generally, there is a selection bias in responses to these kinds of surveys since teachers who are not interested in epistemological issues probably have less incentive to spend 20 or 30 minutes answering a questionnaire on this topic. This means that the teachers who responded to this questionnaire probably had a greater than average interest in epistemological issues of history. A few structural, qualitative and discrete variables that might also influence the teachers’ propensity to respond to the questionnaire and create a selection bias were scrutinised by SCB. These variables were gender, age, place of birth (in Sweden or elsewhere), place of residency (urban or rural), civil state, the percentage of history in their teaching schedule, and academic degree. Three variables appear to have slightly affected the teachers’ propensity to respond to the questionnaire: age, place of birth and place of residency. 44.6% of older teachers (aged 50–65 years) responded, compared to 33.2% of teachers younger than 40 years. 37.2% of teachers aged 40–49 years responded. Teachers born in Sweden were more inclined to respond (38.4%) than teachers born outside Sweden (27.7%). Teachers residing in large cities were also more inclined to respond (42%) than teachers residing in smaller towns and rural areas (36.6%). The other variables showed no differences in the teachers’ propensity to respond to the questionnaire.

The questionnaire comprised of two parts: The first part consisted of statements regarding the nature of history and Likert-scale responses (“fully agree”, “strongly agree”, “somewhat agree”, and “do not agree at all”). 363 teachers responded to all these statements. The second part consisted of textual responses (free-text boxes) to questions about how we can know about specific events in history (Gustav I Vasa’s entry to Stockholm in 1523, the battle of Poltava in 1709, and World War II). The reason for the free-text responses to these questions was to ensure that the teachers responded in their own words without being influenced by predetermined responses. If the word “sources”, “interpretation”, or “historians” had been mentioned in the questions this would probably have pointed the teachers in a certain direction.

For this study, the data were first explored with the intent of understanding the structural variables (e.g., age, gender, academic degree, amount of history studied, or years in service) that influenced the teachers’ view of the nature of history, that is how the teachers responded to the first set of questions. In the second analysis the free-text responses to the questions regarding how we can know something about specific events were evaluated in relation to empirically-based categories of teachers related to the theoretical assumptions discussed above, that is reconstructivist, constructivist and deconstructivist teachers.

Empirical Findings

One of the more obvious results from the questionnaire is that many of the teachers’ views of the nature of history were not easily definable within this theoretical paradigm. The fact that teachers tend to “wobble” or demonstrate epistemic inconsistency that makes it hard to define their epistemological standpoint has also been discussed in previous research (e.g., McCrum, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Stoddard, Citation2010; Stoel et al., Citation2017; VanSledright & Reddy, Citation2014).

The questionnaire had three similar statements: (1) “the past can be truly known”, (2) “history can tell us the truth about the past”, and (3) “the past has an innate meaning that we can hope to discover”. Given the different theoretical constructs of epistemic cognition and historiographical genre position, if you responded “do not agree at all” to statement 1, then it would be virtually impossible to think of a reason why you would respond “totally agree” to statement 2. In other words, if the past cannot be truly known, then how can history tell us the truth about the past? Only four teachers (out of 373 who responded to both questions) actually responded in this way. However, taking the three exemplified statements together, less than 50% of the teachers responded consistently, that is, they were either critical or optimistic about access to the truth about the past. By consistently I mean they responded using either totally or strongly agree to all statements or to none of them. Also, out of the 46 teachers who responded that they disagreed with the statement “the past can be truly known”, more than one quarter of them still either strongly agreed (8) or totally agreed (4) with the statement “history can tell us the truth about the past”.

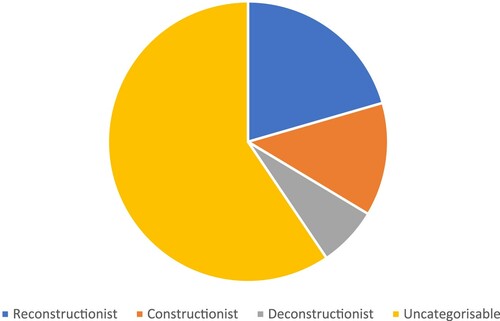

This means that it was rather difficult to assign any specific theoretical category to the teachers, as demonstrated in . Teachers who have indicated that there is an innate meaning within the past and that history can tell the truth about the past have been labelled reconstructionist. Teachers who clearly identify the gap between the past and history, but still seem to see this gap as bridgeable in their answers, have been labelled constructionist. Given the questions in the questionnaire, and the way teachers answered them, it was very difficult to establish the difference between constructionist and deconstructionist teachers. However, the very few teachers who do not display any kind of belief that the identified gap between the past and history can be overcome have been labelled deconstructionist. Given that this line between constructionist and deconstructionist teachers was difficult to establish, it is also possible to regard both categories as one – more critical – category of teachers, as opposed to the less critical reconstructionist group.

Figure 1. Categorisation of teachers’ genre-position. Only teachers who gave an assessment of all three statements (N=363).

Education and Genre Position

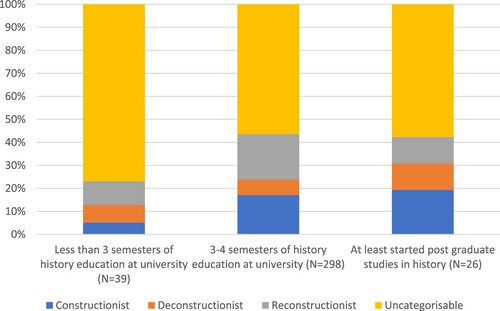

The impact of education on genre position was difficult to assess as most of the teachers had the same educational background. The standard requirement for becoming a history teacher in upper secondary schools in Sweden is to complete three to four semesters of history education at university level. Only 39 of the teachers who responded had completed less education and 26 had completed more.

Even if the numbers in are small, it would appear that educational background does not significantly impact genre position. In all three groups of different educational background, most teachers responded to the statements inconsistently; slightly more so in the less educated group and a greater proportion of the more educated teachers are categorised as constructionist or deconstructionist. However, the number of teachers in two of the groups are too small to make this result statistically significant. If we break this down into a single statement and analyse the precise responses, it becomes more obvious that more education tends to mean a greater level of criticality towards the notion of correspondence between knowable history and the past itself. However, the most frequent response, regardless of educational category, was “strongly agree” to the statement “the past can be truly known” (see ). And again, the number of teachers in the less and the more educated groups were too small to yield a statistically significant result.

Figure 2. Categorisation of teachers’ genre-position in relation to education in history (%). Only teachers who gave an assessment of all three statements (N=363).

Table 1. Replies to the statement “The past can be truly known”, split by educational level (Absolute numbers, percentage in parentheses).

Age and Genre Position

The responses to the questionnaire show a correlation between age and genre position. Age is also strongly related to years in service, and the two are difficult to separate. However, when teachers were grouped according to their years in service and only teachers from the same age group were examined, there was no difference between the groups. Still, when comparing statements from teachers with the same number of years in service, 6–15 years (and the same level of history education at university), but with different ages, there was still a small age-based difference. However, the very small number of older teachers with less than 15 years of service did not yield a statistically significant result, see . Younger teachers appear to be more inclined to have a more critical attitude than older teachers towards definite knowledge of the past, indicating that age is an important factor on its own, perhaps related to the general conceptualisation in historical culture and within the subject of history at the time when the teachers themselves were young and attended school.

Table 2. Replies to the statement “The past can be truly known”, split by age group. Only teachers with 6–15 years of service and three semesters of history education at university (Absolute numbers, percentage in parentheses).

Age was a divider in the responses to all the statements, perhaps particularly so regarding the statement “The past has an innate meaning that we can hope to discover”, which the younger teachers were more sceptical about than the older teachers.

As is evident from , very few of the teachers totally agreed with this statement, regardless of age group. However, there are vast differences in the inclination to respond “strongly agree”. 45% of the older teachers (37 individuals) responded that they strongly agreed with this statement, while only 18% of the younger teachers (18 individuals) responded in the same way. This is a statistically significant result.

Table 3. Replies to the statement “The past has innate meaning that we can hope to discover” within different age groups. Only teachers with three semesters of history education at university (Absolute numbers, percentage in parentheses).

Many Western countries have incorporated the idea of teaching “history as interpretation” (therefore not ascribing the past an innate meaning) in curricula (Mathis & Parkes, Citation2020, p. 192). This could also be seen as a reasonable understanding of the Swedish history syllabus for upper secondary schools (Lgy11, English version, Citation2011, p. 208). This statement (“history is interpretation”) also appeared in the questionnaire and only five of the 373 teachers who responded to this question indicated that they “do not agree at all” with this statement, all of them older than 55.

Genre Position and Epistemic Cognition

How does the genre position of teachers generally translate into epistemic cognition with regards to specific historical events? What do teachers think is required in order to make defensible knowledge claims about past events? Given the different views on the nature of historical knowledge, it could be anticipated that there would be a clear correlation between being constructionist or deconstructionist, on the one hand, and epistemic cognition leaning towards evaluativist, on the other. However, these tendencies of correlation were only slightly visible in the responses.

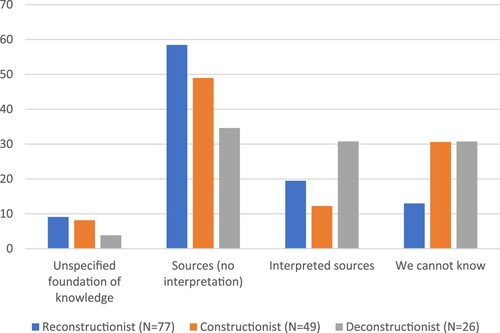

The questionnaire contained open questions on knowledge claims about specific historical events: two events from older Swedish history: Gustav I Vasa’s entering of Stockholm in 1523 and the battle of Poltava in 1709. The third event was the global and modern historical event of World War II. The differences in the responses to these questions showed a slight correlation with the teachers’ genre position. Since these were free-text responses, they were first coded into four categories:

Responses that obviously point in the direction of knowing, but without being specific as to how historical knowledge is created (e.g., “We know about this through stories/textbooks”), or only utilise one particular account of what happened (e.g., “We know, because researcher X said it happened this way”).

Sources were mentioned in isolation, either using the word “sources” (källor or primärkällor) or by mentioning specific primary sources.

In addition to the sources there was an acknowledgement of interpretation or scholarly work. Historians were explicitly described as doing something with the sources, (e.g., “Sources interpreted by historians”).

Critical responses that obviously pointed in the direction of not being able to know at all, even though sources or research were mentioned (e.g., by stating that all sources are biased rendering true knowledge impossible, stating that research is biased, or by simply stating “We can’t know”).

Responses corresponding to the first and second category tend to lean towards an absolutist understanding because they do not acknowledge any interpretive process in an obvious way. However, there is also a difference between these categories, as an interpretive process could be implied in a response relating to the second category, while this is harder to see in responses relating to the first category. Also, responses in the first category could also be interpreted to mean what VanSledright has called “encyclopedic epistemology” (VanSledright, Citation2002), suggesting that there are texts that can provide uncontested meaning. The third category corresponds to at least a multiplist view but could also correspond to an evaluativist view. The fourth category corresponds to an evaluativist view, or in some cases a multiplist view depending on what reasons (if any) are given, and could also correspond to a deconstructionist genre position.

Not surprisingly, the reconstructionist teachers showed a greater inclination to base their knowledge on unspecified “narratives” (1) or only mention sources without expressing any views about interpretation (2). The constructionist and deconstructionist teachers were slightly more inclined to give critical responses (4). Interestingly, the reconstructionist teachers gave more responses corresponding to the third category (“interpreted sources”) than constructionist teachers, but only when responding to the oldest event. For the other events, the numbers in all categories were largely the same, although almost all the teachers who gave no response or who claimed it impossible to know about Gustav Vasa’s entering of Stockholm, changed to “Interpreted sources” when discussing the Battle of Poltava and World War II, which meant that the percentage of constructionist and deconstructionist teachers increased significantly in this category. Moreover, the differences were negligible, meaning that no correlation between the teachers’ genre position and their epistemic cognition could be established (), which might be considered surprising.

Figure 3. Categorisation of teachers’ answers to the question “How do we know anything about Gustav I Vasa’s entering of Stockholm in 1523?” (%).

Interestingly, the uncategorisable teachers who responded inconsistently to the statements and therefore appeared to “wobble” or send mixed messages about their genre position, responded to the open questions with an almost identical distribution between the four categories, as did the teachers who could be categorised as reconstructionist. However, the differences between these two groups and the groups of constructionist and deconstructionist teachers are not statistically significant, making the connections between genre position and epistemic cognition appear almost arbitrary.

Discussion and Conclusion

Earlier research has underlined what is at stake when discussing teachers’ epistemological understanding of the subject they are teaching. Bruce VanSledright and Liliana Maggioni wrote in 2016 when summarising research on epistemic cognition in history: “The absence of capabilities for deeply understanding the past, and to make defensible knowledge claims about it, places democratic deliberation in jeopardy” (VanSledright & Maggioni, Citation2016, p. 142). If teachers do not have an explicit understanding of their own comprehension of epistemological claims in history, then it will probably be very difficult to instil something that is akin to epistemological reasoning in their students. After all, teaching history as a form of interpretation from multiple perspectives includes some measure of explaining how there can be more than one perspective, and what that means for our understanding of the difference between the history of an event and the event itself. If this puts democratic deliberation in jeopardy then it is a most alarming problem. However, if these discussions about how teachers understand the epistemology of history are based on theoretical assumptions that are not capable of capturing how most history teachers reason about history, then this problem is perhaps less severe.

The fact that only 150 out of 363 teachers (who responded to all the statements) were consistent enough in their assessment of the statements in the questionnaire to be assigned a genre position category demonstrates one, two or all three of the following: (1) many of the teachers did not understand the questions; (2) theories on epistemic cognition and genre position do not really take into account the way that teachers think about the nature of knowing, perhaps due to the teachers’ didactical rather than epistemic approach to questions about their teaching subject, and (3) many history teachers have vague and/or inconsistent ideas about the epistemic nature of the subject they are teaching.

It seems implausible that over one half of the teachers did not understand these three statements. It was precisely for the purpose of limiting misunderstandings that only a few statements were used in the questionnaire. It seems to be more plausible that the reason that only around 4 out of 10 teachers could be categorised as reconstructionist, constructionist, or deconstructionist is a combination of weakness in theory and history teachers’ vague/inconsistent ideas about these matters. These two explanations are also related because discussions about the nature of history could also be lacking in the education of history teachers in Sweden, as has been shown in previous research elsewhere (McCrum, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Stoddard, Citation2010; VanSledright & Reddy, Citation2014), making history teachers’ views on these matters purely didactical.

Regarding the impact of education, it is possible, and perhaps even plausible, that there are important differences between the reason for responding “totally agree” or “strongly agree” to the statements that are at least somewhat dependent on the kind of history education a teacher has received. A teacher who holds a PhD in history (which some of the teachers did) might respond “strongly agree” to the statement “History can tell us the truth about the past” or “The past can be truly known” as a very conscious statement relating to the academic debate regarding what historical research actually means, and what it can tell us about reality. At the same time, someone in the less educated group – some of whom had not studied any history other than what they had learned in upper secondary school themselves – might respond “totally agree” or “strongly agree” because they cannot see any reason to critically examine historical knowledge claims. Therefore, their response might be less of a statement and more of a direct consequence of a very absolutist and/or encyclopaedic view of history’s epistemic nature. Comments to the questions by some of the teachers tend to indicate these kinds of differences. For example, one teacher who had a PhD in history and responded “strongly agree” to the statement “The past can be truly known” wrote this as a comment to the questionnaire:

Historical research is a complex endeavour; that is, seeking out new knowledge in areas in which there are knowledge gaps paves the way for teaching to demonstrate the challenges that exist in creating new knowledge […] (Response 201).

However, some of the teachers with less education who responded “strongly agree” to statements that downplayed the differences between the past itself and history also had more nuanced comments. Moreover, responses to other statements such as “History is interpretation” and “The past has an innate meaning that we can hope to discover” also indicated that there are minor rather than major differences between the more and less educated teachers regarding their responses to this questionnaire, even if the more educated teachers had a slightly higher tendency to agree with the former statement and disagree with the latter. One particularly telling aspect is that all three groups with different educational backgrounds basically had the same “curve” in their responses. That is, in all groups, from those that had started post-graduate studies, to those with less than three semesters of history education at university, the most common response to the statement “the past can be truly known” was “strongly agree”.

From this data it is not possible to show any correlation between the teachers’ education in history and their genre position. The data points in a direction that indicates that more history education tends to make teachers more critical towards the idea of equivalence between historical narratives and the past itself, although the impact appears to be small to non-existent. However, considering the plausibility of the different reasons for responding in a certain way, related to educational background, this issue needs to be further researched.

The statistically significant differences in responses according to age could indicate that more general life experience makes teachers less critical about these matters. It could also indicate changes based on years in service, since the response sample was too small to yield statistically significant results when controlling for years in service, because years in service naturally corresponds to age. After all, no teachers under the age of 40 have been teaching for 20 years, whereas most teachers over the age of 60 have been teachers for more than 20 years.

However, there could be a case for the differences in responses dependent on age being related to how history was generally conceived and taught when they were young. In such case, the differences might indicate that epistemological attitudes develop earlier in life. The role of history in society and in school has changed significantly in the last 40 years (Elmersjö, Citation2021; Kjeldstadli, Citation1994; Seixas, Citation2000; Zander, Citation2001).

The critical inclination regarding epistemological issues appears to change somewhere in the age range of 40–49 years (on a group level), an age group that holds a middle ground in . This group was born between 1970 and 1979 and – if they lived in Sweden (and over 95% of the responding teachers were born in Sweden) – started compulsory school (grundskola) between 1977 and 1986, most of them would have finished upper secondary school (gymnasieskola) somewhere between 1988 and 1998. This period coincides with significant changes to historical culture which are also apparent in changes to history syllabi. Major changes to the way history was taught, in both compulsory school and upper secondary school, were made in between 1980 and 1994. In line with overall changes to historical culture during the 1970s and 1980s, these changes pushed the subject towards more criticality, dependent on historical thinking skills and orientation in time (see e.g., Ammert, Citation2013: ch. 2; Elmersjö, Citation2017, Citation2021). This gives a window of change regarding how the subject of history was viewed in syllabi as well as how history in general was viewed within Swedish and Western historical culture, that coincide with changes in attitudes towards the statements in the questionnaire.

The fact that it was not possible to establish statistically significant differences regarding epistemic cognition between the teachers who had been categorised as reconstructionist and the teachers who had been categorised as constructionist or deconstructionist, further emphasises the difficulty in assessing the teachers’ epistemic views of the subject within this theoretical construct. Obviously, many of the teachers who responded to this questionnaire do not have a consistent view of the nature of the subject, of the relationship between the past itself and history, or about how defensible knowledge claims are constructed. This is particularly interesting as it might be expected that the 37.5% of randomly selected teachers who responded to this questionnaire have a greater than average interest in such matters.

Many of the free-text responses demonstrate some deeper understanding of history and about the nature of knowledge claims that can be made about the past in historical research and narratives. However, for the most part, these responses tend to be isolated and are not part of a consistent view that corresponds to any of the theoretical categories. This could be because teachers tend to think about these matters as teachers, not as historians. Their primary task is to teach history and they therefore responded to these questions according to a combination of what is teachable for their age group, what is in the syllabus, what they think their young students need in relation to what they already know, and perhaps only sometimes some aspects of what they themselves might think about the nature of history. One free-text response from an experienced older teacher (who was “wobbling” regarding their epistemic position) might shed some light on this:

It is very important to teach a lot of facts about the historical periods, different individuals and other factors that influence historical development. To neglect fact-orientated subject matter in favour of analysis and nuance is not the right way to go. This debate has been going on for a couple of years now and [in many of my students] there appears to be a frightening ignorance about what has happened in the world and in Sweden in different periods (Response 493).

Having said that, given that the history syllabus in Swedish upper secondary school is also very much about teaching the nature of history, the use of history, and competences in interpreting history, it would perhaps be more satisfying if the teachers themselves had the time, the language and the general epistemological knowledge to form an informed view of the nature of their subject, detached from their role as educators.

In conclusion, at least half the teachers seem to wobble or have an inconsistent view of the nature of their subject, as evident both from how they see the relationship between the past and history, as well as how they reason about how to reach defensible historical knowledge claims. This might point to a problem in their education and in the way they address their subject, that will probably affect students. The study also shows that there are age related differences between the teachers, with younger teachers being more critical towards objective knowledge than their older colleagues. However, there are some indications pointing to these results being affected by the teachers commenting, not on the nature history itself, but the history they see fit to teach in their classroom.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers and also to Kent Löfgren, who helped me with the statistical calculations. I am also indebted to my project collaborator Paul Zanazanian, McGill University.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alvén, F. (2017). Tänka rätt och tycka lämpligt: Historieämnet i skärningspunkten mellan att fostra kulturbärare och förbereda kulturbyggare. Malmö högskola.

- Ammert, N. (2013). Historia som kunskap: Innehåll, mening och värden i möten med historia. Nordic Academic Press.

- Barton, K. C. (2012). Agency, choice, and historical action: How history teaching can help students think about democratic decision making. Citizenship Teaching & Learning, 7(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1386/ctl.7.2.131_1

- Berg, M. (2014). Historielärares ämnesförståelse: Centrala begrepp i historielärares förståelse av skolämnet historia. Karlstads universitet.

- Carr, D. (1986). Time, narrative and history. Indiana University Press.

- Cubitt, G. (2007). History and memory. Manchester University Press.

- Eliasson, P., & Nordgren, K. (2016). Vilka är förutsättningarna i svensk grundskola för en interkulturell historieundervisning? Nordidactica, 6(2), 47–68. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/19028/17219

- Elmersjö, HÅ. (2017). En av staten godkänd historia: Förhandsgranskning av svenska läromedel och omförhandlingen av historieämnet 1938–1991. Nordic Academic Press.

- Elmersjö, HÅ. (2021). An individualistic turn: Citizenship in Swedish social studies and history syllabi, 1970–2017. History of Education, 50(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2020.1826052

- Elmersjö, HÅ, Clark, A., & Vinterek, M. (2017). Introduction: Epistemology of rival histories. In HÅ Elmersjö, A. Clark, & M. Vinterek (Eds.), International perspectives on teaching rival histories: Pedagogical responses to contested narratives and the history wars (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hansson, J. (2010). Historieintresse och historieundervisning. Umeå University.

- Jenkins, K., & Munslow, A. (2004). The nature of history reader. Routledge.

- King, P., & Kitchener, K. S. (2002). The reflective judgement model: Twenty years of research on epistemic cognition. In B. Hofer, & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 37–61). Erlbaum.

- Kjeldstadli, K. (1994). Fortida er ikke hva den en gang var: En innføring i historiefaget. Universitetsforlaget.

- Kuhn, D., & Weinstock, M. (2002). What is epistemological thinking and why does it matter? In B. Hofer, & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 121–145). Erlbaum.

- Levisohn, J. A. (2010). Negotiating historical narratives: An epistemology of history for history education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 44(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2010.00737.x

- Levstik, L., & Barton, K. C. (2011). Doing history: Investigation with children in elementary and middle schools. Routledge.

- Lgy 11. (2011). Curriculum for the upper secondary school. English version. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Lilliestam, A. (2013). Aktör och struktur i historiundervisning: Om utveckling av elevers historiska resonerande. Göteborgs universitet.

- Lozic, V. (2010). I historiekanons skugga: Historieämne och identifikationsformering i 2000-talets mångkulturella samhälle. Malmö Högskola.

- Maggioni, L., VanSledright, B., & Alexander, P. (2009). Walking on the borders: A measure of epistemic cognition in history. Journal of Experimental Education, 77(3), 187–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.77.3.187-214

- Mathis, C., & Parkes, R. (2020). Historical thinking, epistemic cognition, and history teacher education. In C. Berg, & T. Christou (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of history and social studies education (pp. 189–212). Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCrum, E. (2013a). Diverging from the dominant discourse: Some implications of conflicting subject understandings in the education of teachers. Teacher Development, 17(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2013.837093

- McCrum, E. (2013b). History teachers’ thinking about the nature of their subject. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 73–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.004

- Nordgren, K. (2006). Vems är historien? Historia som medvetande, kultur och handling i det mångkulturella Sverige. Karlstads universitet.

- Nygren, T. (2009). Erfarna lärares historiedidaktiska insikter och strategier. Umeå universitet.

- Nygren, T., Vinterek, M., Thorp, R., & Taylor, M. (2017). Promoting a historiographic gaze through multiperspectivity in history teaching. In HÅ Elmersjö, A. Clark, & M. Vinterek (Eds.), International perspectives on teaching rival histories: Pedagogical responses to contested narratives and the history wars (pp. 207–228). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parkes, R. (2011). Interrupting history: Rethinking history curriculum after ‘the end of history’. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Parkes, R. (2013). Postmodernism, historical denial, and history education: What Frank Ankersmit can offer to history didactics. Nordidactica, 3(2), 20–37. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/18954/17151

- Persson, A. (2017). Lärartillvaro och historieundervisning: Innebörder av ett nytt uppdrag i de mätbara resultatens tid. Umeå universitet.

- Persson, A. (2019). Kolonisatör eller turist? Frågor och arbetsuppgifter i svenska historieläromedel under en tid av kunskapsideologisk förhandling. Nordic Journal of Educational History, 6(2), 45–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36368/njedh.v6i2.150

- Seixas, P. (2000). Schweigen! die Kinder! or, does postmodern history have a place in the schools? In P. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives (pp. 19–37). New York University Press.

- Stoddard, J. (2010). The roles of epistemology and ideology in teachers' pedagogy with historical 'media'. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 16(1), 153–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600903475694

- Stoel, G., Logtenberg, A., Wansink, B., Huijgen, T., van Boxtel, C., & van Drie, J. (2017). Measuring epistemological beliefs in history education: An exploration of naïve and nuanced beliefs. International Journal of Educational Research, 83, 120–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.03.003

- Stradling, R. (2003). Multiperspectivity in history teaching: A guide for teachers. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Straub, J. (2005). Narration, identity and historical consciousness. Berghahn Books.

- Thorp, R. (2015). Representation and interpretation: Textbooks, teachers, and historical culture. IARTEM e-Journal, 7(2), 73–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21344/iartem.v7i2.747

- VanSledright, B. (2002). Confronting history’s interpretive paradox while teaching fifth graders to investigate the past. American Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 1089–1115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/000283120390041089

- VanSledright, B., & Maggioni, L. (2016). Epistemic cognition in history. In J. A. Greene, W. A. Sandoval, & I. Bråten (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic cognition (pp. 128–146). Routledge.

- VanSledright, B., & Reddy, K. (2014). Changing epistemic beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teachers. . Tempo & Argumento, 6(11), 28–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5965/2175180306112014028

- Virta, A. (2001). Student teachers’ conceptions of history. International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research, 2(1), 1–11. https://www.history.org.uk/publications/categories/304/resource/4853/the-international-journal-volume-2-number-1

- von Borries, B. (2001). ‘Multiperspectivity:’ utopian pretension or feasible fundament of historical learning in Europe? In J. van der Leeuw-Roord (Ed.), History for today and tomorrow: What does Europe mean for school history (pp. 269–295). Hamburg.

- Wendell, J. (2018). History teaching between multiperspectivity and a shared line of reasoning: Historical explanations in Swedish classrooms. Nordidactiaca, 8(4), 136–159. https://journals.lub.lu.se/nordidactica/article/view/19081/17270

- White, H. (1973). Metahistory: The historical imagination in nineteenth-century Europe. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Zander, U. (2001). Fornstora dagar, moderna tider: Bruk av och debatter om svensk historia från sekelskifte till sekelskifte. Nordic Academic Press.