ABSTRACT

Inadequate academic functioning among students might be a main cause of the considerable dropout rates, and well-being and achievement problems in higher education. Few studies address the role of motivation for academic functioning. Thus, using Self-Determination Theory, the main goal of this study was to investigate motivational determinants of academic functioning among 406 biology students (mode age 21-25, 69.5% females) from nine higher education institutions in Norway. Data were collected using an online survey and analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling. Results show that teacherś autonomy-support positively predicts autonomous motivation and perceived competence among the students. In turn, autonomous motivation and competence positively predicts vitality, and negatively predicts dropout intentions. Achievement was only predicted by perceived competence. We recommend that instructors adopt an autonomy-supportive teaching style, for example by providing a meaningful rationale when introducing teaching and learning activities, for students to feel more competent and autonomous in their motivation.

1. Introduction

Finding ways to optimize students’ academic functioning is an important task for instructors and higher education institutions alike. Academic functioning is an umbrella term that consists of negative and positive indicators of studentś academic experience (Bélanger & Ratelle, Citation2021). A negative indicator of academic functioning is dropout. Each year, student dropout from higher education is costing society millions of dollars globally. According to the OECD (Citation2019), institutions spend, on average, 15 600 USD per higher education student, while the financial return for the society is 112 750 USD for each student graduating. Dropout also has negative impacts on the individual level: students that drop out of higher education have lower personal finances (2000 USD more in financial return per year for a graduated individual), poorer social justice, and reduced health in a life-long perspective compared to students that graduate (Groot & Maassen van den Brink, Citation2007; Larsen et al., Citation2013; Vossensteyn et al., Citation2015). The problem is notable: in Norway, 34% of students drop out completely during higher education and only 49% of the students complete a bachelor and master degree within the stipulated time (Høgestøl et al., Citation2017; Statistics Norway, Citation2019). Furthermore, approximately 50% of all students change their initial institution, field of study, or transfer to another institution (Hovdhaugen, Citation2009). Similar dropout rates are found elsewhere in Europe and in the United States (McFarland et al., Citation2019; Vossensteyn et al., Citation2015). Students might drop out of higher education for a number of reasons, mainly erroneous educational choices or lack of motivation (Meens et al., Citation2018).

Positive indicators of academic functioning consist of psychological well-being and academic achievement (Bélanger & Ratelle, Citation2021). Studentś psychological well-being has decreased in recent years. For example, students in higher education in Norway report that they experienced more pressure in 2018 compared to 2010, and severe mental health issues among students increased from 16% to 29% in the same period, causing mental health problems such as low energy, negativity, and exam anxiety (Knapstad et al., Citation2018). This suggests that it is necessary to explore and test factors that improve well-being. Well-being is a multifaceted psychological construct with two main conceptualizations, where “feeling good” (hedonic well-being) is contrasted with “doing good” (eudaimonic well-being) such as acting with agency and develop and master skills (Hope et al., Citation2019). Vitality is an aspect of eudaimonic well-being, defined as the experience of feeling energetic and alive (Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997). Vitality is regarded as an easily accessible marker of well-being (Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997) and a significant indicator of positive outcomes such as positive affect, higher productivity, and more resiliency towards stress (Ryan & Deci, Citation2008). These positive outcomes makes vitality an important focus for research (León & Núñez, Citation2013; Ryan & Deci, Citation2008).

Finally, achievement has been linked to a range of important outcomes (e.g., Schneider & Preckel, Citation2017). For example, prior performance is predictive of future achievement (e.g., undergraduate achievement has been linked to future achievement at the graduate level), hiring decisions, future salary, and post-educational job performance (Hattie, Citation2009; Kuncel et al., Citation2005; Strenze, Citation2007). Hence, investigating the causes of achievement is an important task in and of itself.

As above-reviewed, academic functioning is an important area to investigate, and improved understanding of the determinants of academic functioning can identify actions and strategies to positively impact studentś academic experience. Investigating studentś academic functioning from a motivational lens may be valuable because of its link to adaptive student outcomes (Fourie, Citation2020; Larsen et al., Citation2013; Richardson et al., Citation2012). However, according to Vossensteyn et al. (Citation2015), there is a lack of studies investigating the role of motivation for academic functioning in higher education. Thus, investigating the motivational determinants of academic functioning is important for understanding the underlying mechanism of positive and negative student experiences and outcomes. Thus, the main aim of this study is to investigate motivational determinants for academic functioning. In the present study, we operationalize academic functioning as dropout, vitality, and academic achievement.

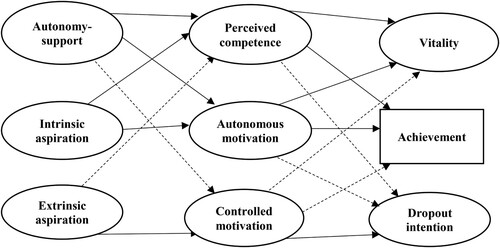

Through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), we investigate motivational determinants of studentś academic functioning. SDT is chosen because it is a broad theory on human motivation that provides a theoretical account for factors that enhances studentś academic motivation and competence, and its effect on academic functioning (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). We propose a motivational model of academic functioning based on SDT and previous empirical research that consists of three pillars. First, predictors: studentś social support and individual aspirations. An important source of social support for students in higher education is the instructor’s ability to provide support for students’ motivation. Moreover, students enter higher education with different levels of aspiration which impact motivation. Second, mediators: instructor support and level of aspiration, in turn, enhances studentś academic motivation and competence. And third, outcomes: students with a high degree of motivation and competence, in turn, have lower dropout intention, higher vitality, and higher achievement. Integrating these interlinked motivational determinants in a coherent and theoretical approach is necessary for understanding academic functioning. Such a coherent understanding of the determinants of academic functioning is needed to promote better student outcomes and societal outcomes of higher education. gives an overview of our model. Below, we provide evidence and theoretical justification for the proposed model and hypothesized relations.

Figure 1. Motivational model of academic functioning and success. Note: The figure depicts the hypothesized relations in our motivational model. Solid lines indicate positive hypothesized relations. Stippled lines indicate negative hypothesized relations.

1.1 Predictors of Academic Functioning: Instructor Support and Life Aspirations

In our proposed model, we investigate how instructorś support and studentś individual aspirations influence studentś motivation and competence. In an educational context, the instructor is the authority that sets the learning atmosphere and either supports or thwarts the studentś motivation and competence. Within SDT, an autonomy-supportive instructor takes the students’ perspective, provides students with meaningful choices where possible, informative feedback, optimally challenging learning activities, meaningful rationales, and genuinely cares for the students (Reeve, Citation2009).

Autonomy-supportive instructors increase studentś autonomous motivation and perceived competence because they satisfy their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). For instance, higher education instructors with an autonomy-supportive teaching style increase studentś need satisfaction (Girelli et al., Citation2018; Jang et al., Citation2016), autonomous motivation (Levesque-Bristol & Stanek, Citation2009; Niemiec & Muñoz, Citation2019; Waaler et al., Citation2013), perceived competence (Guay & Vallerand, Citation1996; Jeno et al., Citation2018; Vallerand et al., Citation1997), persistence (Guiffrida et al., Citation2013; Pichon, Citation2016; Settle, Citation2011; Trolian et al., Citation2016), and psychological well-being (Benita et al., Citation2014, study 1). Thus, because autonomy-supportive instructors provide choice and rationale (i.e., support autonomy) and provide informative feedback and structure (i.e., support competence), we expect that autonomy-support from the instructor will positively increase studentś autonomous motivation and perceived competence, and be negatively related to controlled motivation, for learning activities in higher education courses (see for specific hypothesized relations). Further, due to autonomy-supportive instructors’ ability to provide scaffolding, acknowledging signs of improvement and mastery, listening to students, being responsive to studentś comments, and caring and relating, we expect that autonomy-support will indirectly decrease dropout intention, and positively enhance vitality and achievement, mediated through autonomous motivation and perceived competence.

Another important antecedent of studentś motivation is the studentś individual aspirations. Within SDT, life aspirations are differentiated between intrinsic (community, contribution, health, growth, affiliation) and extrinsic (wealth, fame, physical appearance) aspirations (Kasser & Ryan, Citation1996; Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2006). Research by Kasser and Ryan (1993, 1996) have shown that placing importance on intrinsic aspirations, relative to extrinsic aspirations, is positively related to well-being and negatively related to ill-being. In a longitudinal study, Niemiec et al. (Citation2009) found that attaining extrinsic aspirations was positively related to ill-being, whereas attaining intrinsic aspirations was positively related to psychological well-being. In a similar vein, Hope et al. (Citation2019) found that intrinsic aspirations positively predicted changes in well-being across five time points. Moreover, holding intrinsic aspirations, as opposed to extrinsic aspirations, has been found to directly and indirectly predict persistence and achievement (e.g., Fryer et al., Citation2014; Jeno et al., Citation2018; Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2004).

Hence, intrinsic aspirations seem to have both direct and indirect relations to beneficial educational outcomes. Therefore, we expect that intrinsic aspiration will positively and directly predict autonomous motivation and perceived competence, whereas extrinsic aspiration will positively and directly predict controlled motivation and negatively predict perceived competence. This is because intrinsic aspirations are usually pursued for autonomous reasons, whereas extrinsic aspirations are usually pursued for controlled reasons (e.g., Sheldon et al., Citation2004). Thus, having intrinsic aspirations, relative to extrinsic aspirations, is assumed to enhance autonomous motivation and perceived competence because they are inherently need-satisfying, and thus related to interest enjoyment, value, and feelings of mastery and effectance (Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2006). This line of reasoning is supported by SDT and research on university students (Hope et al., Citation2019; Jeno et al., Citation2018; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017)

Furthermore, we expect that intrinsic aspiration will indirectly reduce dropout intention and positively influence vitality and achievement, through the effect of autonomous motivation and perceived competence. In contrast, we expect that the positive effect of extrinsic aspiration on dropout intention, and the negative effect on vitality and achievement, through the effect of controlled motivation. This is because students pursuing intrinsic aspirations, relative to extrinsic aspirations, are energized by satisfaction of the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which according to SDT is necessary for psychological well-being and growth, and optimal functioning (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Hence, a student with intrinsic aspirations for studying, will more likely have autonomous reasons for studying biology and feel more competent at it, which in turn manifest as less dropout intentions, more vitality, and higher achievement outcomes.

1.2 Autonomous Motivation and Perceived Competence, and its Relation to Academic Functioning

According to SDT, motivation is depicted as a continuum ranging from highly controlled to highly autonomous (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Controlled motivation refers to behaviors done out of external or internal pressure. Controlled motivation encompassed external regulation (undertaking activities purely for rewards or avoidance of punishments) and introjected regulation (undertaking activities out of internal pressures like shame, guilt, or pride). In contrast, autonomous motivation refers to behaviors done out of personal endorsement, volition, and choice. Autonomous motivation encompasses identified regulation (activities done out of value of the activity), integrated regulation (activities done out of value, and in congruency with other core values and interests), and intrinsic motivation (activities done out of inherent interest and enjoyment). Moreover, SDT suggests that perceived competence, when measured as a motive and belief, is important for studentś academic functioning (Patrick & Canevello, Citation2011). That is, measuring perceived competence (perceiving having necessary skills to perform an action or activity) within a specific context, in addition to measuring autonomous motivation, is important in order to understand the reason for doing an activity (controlled vs autonomous motivation) and the belief for performing the activity (perceived competence) (Patrick & Canevello, Citation2011; Ryan & Deci, Citation2006). In the present study, we include autonomous and controlled motivation, and perceived competence as mediators in our model.

Research within SDT has found positive outcomes for studentś autonomous motivation and perceived competence. For example, a recent meta-analysis found that more autonomous types of motivation, compared to controlled forms of motivation, are consistently related to positive outcomes such as achievement, less dropout intentions, engagement, and study effort (Howard et al., Citation2021). Similar studies have been found in individual studies. In a representative sample of biology students in Norway, Jeno et al. (Citation2018) found that autonomous motivation and perceived competence uniquely and positively predicted achievement, and negatively predicted dropout intention. Girelli et al. (Citation2018) found similar results for academic adjustment and dropout intention. Moreover, across two studies, Litalien et al. (Citation2017) found that autonomous motivation positively predicted satisfaction with studies and negatively predicted dropout intention and ill-being. In sum, research on the positive effect of autonomous motivation and perceived competence, and the negative effect of controlled motivation consistently predicts dropout and achievement, in line with assumptions of SDT (e.g., Lavigne et al., Citation2007; Vallerand & Bissonnette, Citation1992). Due to autonomous motivation and perceived competence being related to interest, enjoyment, personal importance, and mastery, as opposed to controlled motivation, we reason that autonomous motivation and perceived competence can protect against dropout (Respondek et al., Citation2017) and increase vitality and achievement (Brahm et al., Citation2017; Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997). Hence, we expect that autonomous motivation and perceived competence will reduce dropout intention and enhance vitality and achievement. In contrast, controlled motivation is expected to increase dropout intention and lower vitality and achievement.

1.3 The Present Study

In sum, our motivational model is based on the theoretical assumptions of SDT in which we investigate both social support (i.e., instructor autonomy-support) and individual aspirations (i.e., intrinsic vs extrinsic aspirations), and mediators (autonomous motivation and perceived competence vs. controlled motivation), on academic functioning (dropout, vitality, and achievement). There have been studies investigating aspects of motivation and academic functioning in higher education, but they are few. Thus, we extend previous research in several important ways. First, in contrast to other studies (e.g., Guay & Vallerand, Citation1996; Hope et al., Citation2019; Vallerand et al., Citation1997) we investigate a more comprehensive SDT-based model by not only including the social support, but also individual characteristics such as life aspirations, as antecedents of autonomous motivation and perceived competence. This is important in order to understand the underlying factors that account for studentś autonomous motivation and perceived competence. Further, as opposed to Jeno et al. (Citation2018), Hardre and Reeve (Citation2003), and Meens et al. (Citation2018), we include vitality as a measure of well-being in addition to dropout intention and achievement. This is an important extension of the literature because it allows us to understand simultaneously the effects different motivational determinants have on academic functioning.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedures

The participants comprised 406 (69.5% females) biology students in Norwegian higher education. Response rate for this study was 23.7%. All students in Norway studying general biology were asked to participate. This includes a total of nine higher education institutions. The sample is thus nationally representative for biology students in Norwegian higher education. Age was reported in 5 categories, 20 and below (5.9%), 21–25 (62.5%), 26–30 (19.4%), 31–35 (6.1%), and above 35 (5.9%) years of age. The use of categories ensured anonymity for the participants. Students were studying either for a Bacheloŕs degree (65.6%) or a Masteŕs degree (34.4%).

Students were contacted to participate one month after the spring semester had commenced (approximately in mid-February). This was done to ensure that the students had become acquainted with the course and the course instructors. All measures were self-reported by students and collected at this time-point, except the achievement variable which was collected by the end of the semester (approximately at the end of June), and which is an objective measure of studentś biology achievement. Permission to conduct our study was granted by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). Principals of all institutions that offer higher biology education in Norway were asked whether they allowed their students to participate in our study. All institutions agreed to participate. Student emails were collected from each institution and surveys were distributed online. Student participation was voluntary, and they were given the opportunity to withdraw at any time. Students were given the possibility to win one of two tablets, otherwise, no compensation was offered. The questionnaire was written in both Norwegian and English to increase the number of potential participants. See Appendix 1 for an overview of the items for each measure. Conventional procedures were followed to ensure that the translation procedure was done appropriately (see Hole et al., Citation2016).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Autonomy Support

The 6-item Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ; Williams et al., Citation1996) was used to measure studentś perception of autonomy-support from their instructors. The students responded on a rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Item examples are “I feel understood by my lecturers” and “My lecturers encourage me to ask questions”. McDonaldśs omega estimate of reliability in this study was ω = .92.

2.2.3 Life Aspirations

Studentś life aspirations for starting their study were measured with a short 6-item version of the Aspiration Index (Kasser, Citation2019; Kasser & Ryan, Citation1993). Students were asked to rate how important the following reasons were for studying biology. Three items measured intrinsic aspiration (“To help the environment”), and three items measured extrinsic aspiration (“To be a wealthy person”). Participants responded on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very). The McDonaldśs omega for intrinsic and extrinsic aspiration were ω = .90 and ω = .83, respectively.

2.2.4 Motivation

The 12-item Learning Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-L; Black & Deci, Citation2000; Williams & Deci, Citation1996) was used to measure studentś motivation. The questionnaire asked three stems for why students engage in different learning-related activities. Students responded on either autonomous (“I will participate in biology courses because a solid understanding of biology is important for me”) or controlled (“I will participate in biology courses because others may think badly of me if I do not”) reasons for participating in different biology learning-related activities and attending biology courses. Responses were made on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not all true) to 7 (very true). McDonaldśs omega for autonomous and controlled motivation in this study were ω= .80 and ω = .80, respectively.

2.2.5 Perceived Competence

Four items from the Perceived Competence Scale (PCS; Williams & Deci, Citation1996) were employed to measure students’ competence for learning biology. An example item is “I feel confident in my abilities to learn biology”. Students responded on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). McDonaldśs omega for perceived competence was ω = .94.

2.2.6 Dropout Intention

Three items were used to capture studentś dropout intention (e.g., “I often consider dropping out of my courses”). The scale was adapted from Hardre and Reeve (Citation2003) and Jeno et al. (Citation2018). Respondents answered on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). McDonaldśs omega level for dropout was ω = .71.

2.2.7 Vitality

We employed three adapted items from the Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS; Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997) to measure the state of studentś vitality when at the university. Students responded on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). Two item examples are “I feel alive and vital” and “I look forward to each new day”. McDonaldśs omega for vitality was ω = .92.

2.2.8 Achievement

To assess studentś achievement, we collected studentś end of semester grades in biology. Students were asked to provide their student identification or personal number to collect their end of semester grades. Studentś identifiable data were deleted after collecting their grades. In instances where students had multiple biology courses, we used an average. Of 406 participants, 144 (35.4%) allowed us to retrieve their grades. Studentś grades ranged from E (fail) to A (highest score). We converted these letter grades to numbers, 1–6, for analysis purposes.

2.3 Analytical Strategy

All analyses were performed using the statistical software R (R Core Team, Citation2018). Data preparation and descriptive analyses were performed through the following packages “psych” (Revelle, Citation2018), “car” (Fox & Weisberg, Citation2011), “summarytools” (Comtois, Citation2020), “memisc” (Elff, Citation2019), “multicon” (Sherman, Citation2015), “apaTables” (Stanley, Citation2018), and “semPlot” (Epskamp, Citation2019).

The R-package “lavaan” (Rosseel, Citation2012) was used to analyze the scale of each factor structure through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and also to test the proposed structural equation model (SEM). Conventional model fit criteria were used to evaluate the appropriateness of the model (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Specifically, a non-significant chi-square test (Schermelleh-Engel et al., Citation2003), comparative fit index (CFI), tucker-lewis index (TLI) and incremental index of fit (IFI) values above .90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) below .08. Model misspecification was done by evaluating large Lagrange Multiplier in which larger numbers reflect “drop in overall chi-square if a particular parameter would be freely estimated in a subsequent trial”, and re-specifying a new model (Byrne, Citation2016). We followed a theoretical approach for model specification, not a statistical approach (Kline, Citation2011).

Finally, missing data were handled by using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach (Byrne, Citation2016). The FIML approach is the least biased and most efficient and consistent approach to handling missing data compared to other approaches, and thus recommended within the SEM framework (Byrne, Citation2016).

It is important to note that in the present study, despite using SEM, the causal representation of our model is based on theoretical assumptions, prior empirical studies, and our research design, without proving causality (Bollen & Pearl, Citation2013). All our variables are cross-sectional and latent in nature, except achievement which is a manifest variable collected prospectively.

3. Results

Results from the descriptive analyses along with correlations of the variables are shown in . Significant correlations are all in the expected direction. Specifically, autonomy-support, perceived competence, and vitality are positively correlated with achievement. Also, autonomy-support, intrinsic aspiration, perceived competence, and autonomous motivation are positively correlated to vitality, whereas extrinsic aspiration and controlled motivation are negatively related to vitality. Finally, controlled motivation is positively related to dropout intention, whereas autonomy-support, intrinsic aspiration, perceived competence, and autonomous motivation are negatively related to dropout intention.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals for study variables.

Given that a minority (35.4%) of the students allowed us to retrieve their grades, we tested for mean difference between students who provided grades and students who did not. We recoded our achievement variable and coded 0 (n=262) for missing values and 1 (n=144) for grades. Several t-tests were run to test for mean differences on our study variables. Results from the comparison between students who provided grades and students who did not show that all tests were non-significant for autonomy support, t(302) = −1.42, p = .15, 95% CI [−0.41, 0.06], intrinsic aspiration, t(324) = −1.57, p = .11, 95% CI [−0.50, 0.05], extrinsic aspiration, t(300) = −1.32, p = .18, 95% CI [−0.47, 0.09], perceived competence, t(303) = −1.55, p= .12, 95% CI [−0.45, 0.05], autonomous motivation, t(308) = −0.93, p = .35, 95% CI [−0.27, 0.09], controlled motivation, t(291) = −0.42, p = .66, 95% CI [−0.29, 0.18], dropout intentions, t(287) = 0.49, p = .61, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.33], or vitality, t(287) = 0.92, p = .35, 95% CI [−0.18, 0.51], indicating that the cohort who provided grades were representative of the full sample. Hence, we retained the achievement variable for subsequent analyses. Furthermore, as can be seen from , our data has some missing in all of our variables.

Results from our overall measurement model fit the data adequately, χ2(499) = 984.71, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, IFI = .91, RMSEA = .05 [.05, .06], SRMR = .06. Next, we tested our hypothesized SEM-model. Our initial full hypothesized model produced unsatisfactory model fit, χ2(539) = 1194.16, CFI = .90, TLI = .89, IFI = .90, RMSEA = .05 [.05, .06], SRMR = .08. Modification indices suggested omitting one item from the autonomous motivation subscale (“because I think lecturers seems to have insight about how to learn the material”) due to low inter-item correlations, and to covary the residuals of two items from the controlled motivation subscale (item 5 “because a good grade in biology will look good in my diploma/degree” and item 6 “because I want other people to see that Ím intelligent”). These items measure the “pride/self-esteem” aspect of introjected regulation (controlled motivation), and similar covariation between residuals has been found in similar studies (Evans & Bonneville-Roussy, Citation2016; Jeno et al., Citation2018). Our respecified model produced satisfactory model fit, χ2(505) = 910.06, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, IFI = .92, RMSEA = .05 [.04, .05], SRMR = .07. When comparing the models, our respecified model has significantly better model fit, χ2-diff = 184.1(34), p < .001, compared to our baseline model. See Appendix 2 for an overview of the study items and the associated factor loadings.

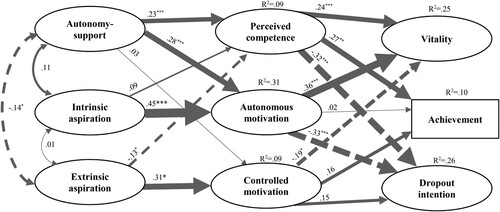

Our respecified model accounts for 26%, 25%, and 10% of the variance in dropout intention, vitality, and achievement, respectively. See . Specifically, we find that autonomy-support positively and directly predicts perceived competence and autonomous motivation. Further, autonomy-support positively and indirectly predicts vitality and achievement via perceived competence, and negatively predicts dropout intention via perceived competence. Similarly, autonomy-support positively and indirectly predicts vitality via autonomous motivation, and negatively and indirectly predicts dropout intention via autonomous motivation. Extrinsic aspiration negatively and directly predicts perceived competence, and positively predicts controlled motivation. An indirect effect was found for extrinsic aspiration on vitality, through controlled motivation. For intrinsic aspiration, we found a direct and positive effect on autonomous motivation, and an indirect and positive effect on vitality via autonomous motivation, and an indirect and negative effect on dropout intentions via autonomous motivation. Vitality is positively predicted by perceived competence and autonomous motivation, and negatively predicted by controlled motivation. For dropout intention, we find that both perceived competence and autonomous motivation are negative predictors. Finally, we find that perceived competence enhances achievement. Results of the indirect effects are presented in .

Figure 2. Final structural equation model (SEM) of the proposed motivational model. Note: For clarity, we omitted the factor loadings from the measurement model. All paths are standardized estimates. Explained variance is shown as R2 for endogenous variables. Solid lines indicate positive relations, whereas stippled lines indicate negative relations. Thicker arrows indicate stronger relationships between variables. * indicates p < .05, ** indicates p < .01, *** indicates p < .001.

Table 2. Indirect effects.

4. Discussion

The main aim of this study was to investigate motivational determinants of studentś academic functioning in higher education based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT). The results from our structural equation model partially support our line of reasoning. We found some support that our predictor variables and mediating variables were indirectly and directly related to our indicators of academic functioning.

According to SDT, when instructors provide students with choice, informative feedback, meaningful rationales, and opportunities for self-initiation, students becomes more autonomous in their motivation, and experience more competence and mastery (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). This is presumably due to instructorś support for the basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Our results are in line with this assumption. That is, we found that students who perceived their instructors as autonomy-supportive, reported higher autonomous motivation and perceived competence.

In contrast to our expectation, autonomy-support remained unrelated to controlled motivation. This was unexpected given that we reasoned that autonomy-supportive teaching style would provide the necessary nutriments for students to internalize why a learning activity is important or valuable, which may help the student become less controlled and more autonomous in their motivation (Deci et al., Citation1994; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Future studies needs to investigate if autonomy-support is solely the driver of autonomous motivation, whereas controlling teaching style is related to controlled motivation, which would be in accordance with the dual process model within SDT, or if these processeś cross-load (Jang et al., Citation2020).

Results from our model further suggests that intrinsic and extrinsic aspiration have differential effect on autonomous and controlled motivation. Specifically, we found that intrinsic aspiration predicted autonomous motivation, and that extrinsic aspiration negatively predicted perceived competence and positively predicted controlled motivation. This finding renders support to the notion that intrinsic aspirations are pursued for autonomous reasons and, conversely, that extrinsic aspirations are done for controlled reasons (e.g., Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2010). In contrast to our expectation, however, intrinsic aspiration was unrelated to perceived competence. While extrinsic aspiration was negatively related to perceived competence, it was unexpected that intrinsic aspiration was unrelated given that we reasoned that intrinsic aspiration is inherently related to psychological need satisfaction. However, there might be other drivers that supports studentś perceived competence that are not characterized by intrinsic aspirations. For instance, structure, feedback, and optimal challenges may be stronger enhancers of perceived competence (Deci & Moller, Citation2005) than intrinsic aspirations such as personal growth, community, and health.

Our findings further suggests that the indirect effect of intrinsic aspiration on academic functioning seems more predictive than extrinsic aspiration. That is, intrinsic aspiration seems to explain more variance in academic functioning (i.e., dropout intentions and vitality) than extrinsic aspiration. Furthermore, our findings suggest that we can expect lower dropout intentions and higher degrees of vitality, to the extent that studentś motivation is autonomous. These findings are in line with the general tenet that the content (i.e., intrinsic vs extrinsic) of the aspiration students pursue, is predictive of mental health and lack of dropout due to the satisfaction of the basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (e.g., Fourie, Citation2020; Guiffrida et al., Citation2013). However, neither aspirations seem to account for studentś achievement. There might be other dynamics that accounts for achievement in higher education that is not predicted for by life aspirations. For instance, type of exam evaluation, teaching activities, studentś learning strategies, and peer collaboration (Biggs & Tang, Citation2011; Dunlosky et al., Citation2013; Schneider & Preckel, Citation2017), might be more predictive of achievement.

As expected, our mediating variables (i.e., autonomous motivation and perceived competence) were negatively associated with dropout intention. These findings corroborate SDT (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017) and previous findings that suggest that autonomous motivation is negatively related to dropout (e.g., Larsen et al., Citation2013; Rump et al., Citation2017). These findings suggest that when studentś motivation and beliefs are characterized by interest, enjoyment, personal value, and mastery and confidence, they are less likely to report intentions of leaving their education because the reason for studying is endorsed and personally chosen by themselves. In contrast to our expectation, controlled motivation remained unrelated to dropout intention in our model. One explanation to this might be the nature of controlled motivation. Controlled motivation is characterized by external or internal pressure. Hence, when the environment forces you to study a degree because of a future reward or career opportunity (external regulation) or because your parents expect you to have a degree (introjected regulation), you might persevere with the education (no dropout intention) but might have less optimal experience at the university (less vitality). These underlying motivational forces and emotional experiences seems also to lead to mixed results on the impact of controlled motivation on dropout (Jeno et al., Citation2018; Koestner & Losier, Citation2002; Lavigne et al., Citation2007; Renaud-Dubé et al., Citation2015). These different motivational dynamics are important for the phenomenology of the students, because despite no dropout intention when their motivation is fueled by controlled motivation, their experiences at the university might be characterized by less energy and aliveness. This is what we found in our model and would be interesting to replicate in a more longitudinal design.

Relatedly, despite personal and societal costs associated with dropout, some dropout is healthy and may be personally endorsed by the students. That is, if a student chooses to leave the institution autonomously, we would predict that this would be associated with less personal conflict and guilt. In some cases, it might even be positive for the student, as a dropout sometimes is a change to a study or institution in more accordance with the student’s own interests. Such cases have still, however, a societal cost. However, a student may leave the institution by controlled reasons, for instance out of external pressure (e.g., no financial support) or introjection (parents conditional regard depends on the student starting a different education), which we would expect to be detrimental for well-being. For instance, Hovdhaugen (Citation2009) found that the reasons for sector dropout were different from the reasons for changing path. Sector dropout correlated with students’ background, such as gender and parents’ educational level, while changing path of study correlated with educational goals and reasons for entering higher education. Thus, further studies need to unpack these dynamics to understand the autonomous and controlled reasons for dropping out.

The results of our model show that autonomous motivation and perceived competence were positively related to vitality, and negatively explained by controlled motivation, as expected. These findings are in line with SDT that suggests that more volitional and personally important reasons for studying manifest as more energy and less depletion (Ryan & Deci, Citation2008). This differential effect of forms of motivation on vitality seems to be consistent across the literature (Howard et al., Citation2021). That is, performing a learning activity out of intrinsic motivation or identified regulation is more associated to wellness, and thus vitality, than performing an activity out of external regulation or introjected regulation (Koestner & Losier, Citation2002). Additionally, feeling competent at doing the activity, positively contributes to experiencing vitality.

Finally, only perceived competence was uniquely associated with achievement. In contrast to our reasoning, autonomous and controlled motivation remained unrelated to achievement. It appears that in the context of biology education, perceived competence is more necessary for achievement than autonomous motivation. Similar results have been found by Jeno et al. (Citation2018). These findings are in contrast to other SDT-based research that consistently finds that autonomous motivation is crucial for achievement (Guay & Bureau, Citation2018; Guay & Vallerand, Citation1996). However, these previous studies have not measured a comprehensive model of academic functioning, and more studies are needed to test a full SDT-based model on academic functioning, to conclude if perceived competence is the sole contributor of academic achievement.

4.1 Limitations

There are several limitations that are worth discussing when interpreting the results. First, our study is correlational, and despite using SEM, which provides the opportunity to test causal relations based on theoretical propositions, the data are cross-sectional in nature. We collected the studentś prospective achievement in their biology courses, which provides us with a refined interpretation of the relationship between motivation and achievement. Furthermore, using theory, empirical studies, and research design to inform a causal model to fit the data is better when using cross-sectional data (Bollen & Pearl, Citation2013). However, no causal inferences can be made. Future studies should test these relations in a longitudinal design. That is, to investigate if an autonomy-supportive environment and level of aspiration predicts sustained autonomous motivation and perceived competence and leads to reduced dropout rates, higher levels of vitality and achievement.

Second, we had missing values in our measured variables, especially for the achievement variable. This may be due to the online survey format which has been shown to have lower response rates (Nair & Adams, Citation2009). Furthermore, only 35% of the students allowed us to retrieve their grades. However, we found no significant difference in our study variables between students who provided us with their grades and students who did not. Hence, our decision to retain achievement in the model seems appropriate. Since we cannot be sure that the students who provided grades are representative of the full cohort, we still recommend interpreting the results of this variable with care. Moreover, future investigations with larger sample sizes are needed to provide validity for our model and the ability to generalize to larger and other populations.

Third, our study employed dropout intention as opposed to actual dropout. This limits our ability to infer causality. Intention to drop out, as opposed to actual dropout, was chosen due to methodological issues related to measuring actual dropout. For instance, program dropout (leaving the program for another program within the institution) may not be considered dropout for the institutions, as opposed to institutional dropout (leaving an institution for another), which may be of concern for the institution but not for the student (e.g., Hovdhaugen, Citation2009). However, sector dropout (leaving higher education altogether) may be problematic for the student, in addition to the institution(s). Such fine-grained analyses are complex and require strict operationalization of dropout (e.g., leaving the sector and not returning to an educational program within five years). In contrast, dropout intention is a subjective measure of the studentś indication of studentś willingness and experience of dropping out (Ajzen, Citation1991). Moreover, measurement of intentionality has proven to predict actual behavior (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, Citation2016). Hence, our strategy was deemed appropriate for the purpose of our study.

Fourth, due to space constraints in our survey, some of our scales (e.g., aspiration and vitality) were shorter than recommended in the original scales (e.g., Kasser, Citation2019; Ryan & Frederick, Citation1997). Despite this limitation, we found good statistical support for retaining the scales in our model, i.e., satisfactory Omega scores and acceptable model fit along with standardized loadings. Furthermore, for both autonomous motivation and controlled motivation, we had to remove an item and covary the residual between two items, respectively. In the instance of controlled motivation, both items measure the “approach” side of introjection. Hence, it could be argued that measuring controlled motivation (and autonomous motivation), which contains both external regulation and introjected regulation, is problematic because it may oversimplify the motivational continuum suggested by SDT (e.g., Howard et al., Citation2017). In order to investigate each motivational regulation in detail, we recommend future studies to employ bifactor exploratory SEM with each individual regulation as mediators (Howard et al., Citation2018) or person-centered approaches (Abós et al., Citation2018).

Finally, despite testing a comprehensive model of academic functioning, we acknowledge the possibility of including other important factors that might account for the unexplained variance in our dependent variables (e.g., personality, socio-economic status, learning strategies), or including more indicators of academic functioning such as school satisfaction, academic engagement, and academic burnout (Bélanger & Ratelle, Citation2021). We recommend future studies include such predictors and outcomes in their model to further test how these interact with our motivational constructs.

4.2 Practical Considerations

Practical recommendations to instructors and institutions in higher education emerge from our study. First, it is important to consider studentś life aspirations when entering higher education. Students may differ in their relative priority of intrinsic (community) or extrinsic (wealth) aspirations. Because our findings indicate that intrinsic aspirations are more conducive to academic functioning, we recommend framing recruitment, course expectations, teaching activities, assignments, and learning outcomes using intrinsic aspirations, as opposed to extrinsic aspirations (Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2009), for example, by emphasizing personal growth instead of financial success. Moreover, institutions can support students by framing intrinsic reasons for why and how a particular education relates to intrinsic aspirations.

Second, we encourage instructors to adopt an autonomy-supportive teaching style, for example by providing a meaningful rationale when introducing teaching and learning activities and encourage students to participate in course design. Our study shows that this may increase studentś autonomous motivation and perceived competence, which in turn decreases dropout intention and increases well-being. Additionally, it is important to listen to students’ concerns, provide choice in teaching, learning, and assessment activities, and to provide scaffolding and appropriate feedback to facilitate feelings of competence. Recent research suggests that active learning may be a pathway to facilitate autonomous motivation and perceived competence, if provided in an autonomy-supportive way (Levesque-Bristol et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Hovdhaugen (Citation2009) found that active participation prevented dropout.

Studying may involve high workload and demands that could be perceived as draining, but this can be counterbalanced by subject interest, enjoyment, and relevant content and work forms (Jensen et al., Citation2018), and by students being engaged in and identifying with their choice of study (Herrmann et al., Citation2017). Broadly, our results support the theoretical constructs we posited in our study design and can be a substantial contribution towards untangling the multifaceted effects that explain students’ academic functioning. Specifically, perceived competence and autonomous motivation are both important for increasing vitality and decreasing dropout – but they emerge from different paths (teacher support vs intrinsic aspirations). Supporting both are important for improving academic functioning.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.6 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

R-codes for the analyses are available in the GitHub repository https://github.com/lujeno/bioCEED2018/blob/main/R-codes

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abós, Á, Haerens, L., Sevil, J., Aelterman, N., & Garcia-Gonzalez, L. (2018). Teachers’ motivation in relation to their psychological functioning and interpersonal style: A variable- and person-centered approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.010

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

- Bélanger, C., & Ratelle, C. F. (2021). Passion in university: The role of the dualistic model of passion in explaining students’ academic functioning. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 2031–2050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00304-x

- Benita, M., Roth, G., & Deci, E. L. (2014). When are mastery goals more adaptive? It depends on experiences of autonomy support and autonomy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034007

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Black, A. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A Self-Determination Theory perspective. Science Education, 84(6), 740–756. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-237X(200011)84:6<740::AID-SCE4>3.0.CO;2-3

- Bollen, K. A., & Pearl, J. (2013). Eight myths about causality and structural equation models. In S. L. Morgan (Ed.), Handbook of causal analysis for social research (pp. 301–328). Springwe.

- Brahm, T., Jenert, T., & Wagner, D. (2017). The crucial first year: A longitudinal study of students’ motivational development at a Swiss business school. Higher Education, 73(3), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0095-8

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Comtois, D. (2020). Summary tools: Tools to Quickly and Neatly Summarize Data. R package version 0.9.8. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=summarytools

- Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00797.x

- Deci, E. L., & Moller, A. C. (2005). The concept of competence: A starting place for understanding intrinsic motivation and self-determined extrinsic motivation. In A. J. Elliot, & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 579–597). The Guilford Press.

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

- Elff, M. (2019). memisc: Management of Survey Data and Presentation of Analysis Results. R package version 0.99.17.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=memisc

- Epskamp, S. (2019). semPlot: Path Diagrams and Visual Analysis of Various SEM Packages’ Output. R package version 1.1.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semPlot

- Evans, P., & Bonneville-Roussy, A. (2016). Self-determined motivation for practice in university music students. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 1095–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735615610926

- Fourie, C. M. (2020). Risk factors associated with first-year students’ intention to drop out from a university in South Africa. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(2), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1527023

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2011). An R Companion to applied regression (2nd ed.). Sage. http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion

- Fryer, L. K., Ginns, P., & Walker, R. (2014). Between students’ instrumental goals and how they learn: Goal content is the gap to mind. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 612–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12052

- Girelli, L., Alivernini, F., Lucidi, F., Cozzolino, M., Savarese, G., Sibilio, M., & Salvatore, S. (2018, November 5). Autonomy supportive contexts, autonomous motivation, and self-Efficacy predict academic adjustment of first-year university students [original research]. Frontiers in Education, 3(95). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00095

- Groot, W., & Maassen van den Brink, H. (2007). The health effects of education. Economics of Education Review, 26(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.09.002

- Guay, F., & Bureau, J. S. (2018). Motivation at school: Differentiation between and within school subjects matters in the prediction of academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.05.004

- Guay, F., & Vallerand, R. J. (1996). Social context, student's motivation, and academic achievement: Toward a process model. Social Psychology of Education, 1(3), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02339891

- Guiffrida, D. A., Lynch, M. F., Wall, A. F., & Abel, D. S. (2013). Do reasons for attending college affect academic outcomes? A test of a motivational model from a Self-Determination Theory perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 54(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2013.0019

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 20(10), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315585005

- Hardre, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of high school. Journal of Education Psychology, 95(2), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Herrmann, K. J., Bager-Elsborg, A., & McCune, V. (2017). Investigating the relationships between approaches to learning, learner identities and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Education, 74(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-9999-6

- Hole, T. N., Jeno, L. M., Holtermann, K., Raaheim, A., Velle, G., Simonelli, A. L., & Vandvik, V. (2016). bioCEED survey 2015. Bora - Bergen Open Research Archive.

- Hope, N. H., Holding, A. C., Verner-Filion, J. R. M., Sheldon, K. M., & Koestner, R. (2019). The path from intrinsic aspirations to subjective well-being is mediated by changes in basic psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: A large prospective test. Motivation and Emotion, 43(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9733-z

- Hovdhaugen, E. (2009). Transfer and dropout: Different forms of student departure in Norway. Studies in Higher Education, 34(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802457009

- Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X. Y., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966789

- Howard, J. L., Gagné, M., & Bureau, J. S. (2017). Testing a continuum structure of self-determined motivation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1346–1377. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000125

- Howard, J. L., Gagné, M., Morin, A. J. S., & Forest, J. (2018). Using bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling to test for a continuum structure of motivation. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2638–2664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316645653

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, structural equation modeling. A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Høgestøl, A., Nordhagen, I. C., & Skjervheim, Ø. (2017). Analyse av studentflyt og sektorfrafall i høyere utdanning i Norge (Rapport 04:2017). idead2evidence.

- Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Halusic, M. (2016). A new autonomy-supportive way of teaching that increases conceptual learning: Teaching in studentś preferred ways. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(4), 686–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2015.1083522

- Jang, H.-R., Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Song, Y.-G. (2020). Dual processes to explain longitudinal gains in physical education students’ prosocial and antisocial behavior: Need satisfaction from autonomy support and need frustration from interpersonal control. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9(3), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000168

- Jeno, L. M., Danielsen, A. G., & Raaheim, A. (2018). 2018/10/21). A prospective investigation of students’ academic achievement and dropout in higher education: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1163–1184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1502412

- Jensen, F., Henriksen, E. K., Holmegaard, H. T., Madsen, L. M., & Ulriksen, L. (2018). Balancing cost and value: Scandinavian students’ first year expereince of encountering science and technology higher education. Nordic Studies in Science Education, 14(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.2343

- Kasser, T. (2019). An overview of the Aspiration Index https://www.timkasser.org/scholarship

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(5), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press.

- Knapstad, M., Heradstveit, O., & Sivertsen, B. (2018). Students’ health and wellbeing study 2018. SIO.

- Koestner, R., & Losier, G. F. (2002). Distinguishing three ways of being internally motivated: A closer look at introjection, identification, and intrinsic motivation. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 101–121). The University of Rochester Press.

- Kuncel, N. R., Credé, M., & Thomas, L. L. (2005). The validity of self-reported grade point averages, class ranks and test scores: A meta-analysis and review of the litterature. Review of Educational Research, 75(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075001063

- Larsen, M. S., Kornbeck, K. P., Kristensen, R. M. L., Larsen, M. R., & Sommersel, H. B. (2013). Dropout phenomena at universities: What is dropout? Why does dropout occur? What can be done by the universities to prevent or reduce it? A systematic review. Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research.

- Lavigne, G. L., Vallerand, R. J., & Miquelon, P. (2007). A motivational model of persistence in science education: A self-determination theory approach. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(3), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173432

- León, J., & Núñez, J. L. (2013). Causal ordering of basic psychological needs and well-being. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0143-4

- Levesque-Bristol, C., Maybee, C., Parker, L. C., Zywicki, C., Connor, C., & Flierl, M. (2019). Shifting culture: Professional development through academic course transformation. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 51(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2019.1547077

- Levesque-Bristol, C., & Stanek, L. R. (2009). Examining self-determination in a service learning course. Teaching of Psychology, 36(4), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280903175707

- Litalien, D., Morin, A. J. S., Gagné, M., Vallerand, R. J., Losier, G. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Evidence of a continuum structure of academic self-determination: A two-study test using a bifactor-ESEM representation of academic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.06.010

- McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Wang, K., Hein, S., Diliberti, M., Cataldi, E. F., Mann, F. B., & Barmer, A. (2019). The condition of education 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019144

- Meens, E. E. M., Bakx, A. W. E. A., Klimstra, T. A., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2018). The association of identity and motivation with students’ academic achievement in higher education. Learning and Individual Differences, 64, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.04.006

- Nair, C. S., & Adams, P. (2009). Survey platform: A factor influencing online survey delivery and response rate. Quality in Higher Education, 15(3), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320903399091

- Niemiec, C. P., & Muñoz, A. (2019). A need-supportive intervention delivered to English language teachers in Colombia: A pilot investigation based on self-determination theory. Psychology (savannah, Ga ), 10((07|7)), 1025–1042. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2019.107067

- Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). The path taken: Consequences of attaining intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations in post-college life. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.09.001

- OECD. (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing.

- Patrick, H., & Canevello, A. (2011). Methodological overview of a self-dermination theory-based computerized intervention to promote leisure-time physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.04.011

- Pichon, H. W. (2016). Developing a sense of belonging in the classroom: Community college students taking courses on a four-year college campus. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2014.964429

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44(3), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

- Renaud-Dubé, A., Guay, F., Talbot, D., Taylor, G., & Koestner, R. (2015). The relations between implicit intelligence beliefs, autonomous academic motivation, and school persistence intentions: A mediation model. Social Psychology of Education, 18(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9288-0

- Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., & Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: Examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(243), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

- Revelle, W. (2018). Procedures for personality and psychological research. In (Version 1.18.10) Northwestern University. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rump, M., Esdar, W., & Wild, E. (2017). Individual differences in the effects of academic motivation on higher education students’ intention to drop out. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(4), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1357481

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self-regulation and the problem of human autonomy: Does psychology need choice, self-determination, and will? Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1557–1586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00420.x

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). From ego depletion to vitality: Theory and findings concerning the facilitation of energy available to the self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00098.x

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality a s a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65(3), 529–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

- Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098

- Settle, J. S. (2011). Variables that encourage students to persist in community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 35(4), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920701831621

- Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2004). The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It's both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(4), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203261883

- Sherman, R. A. (2015). multicon: Multivariate Constructs. R package version 1.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=multicon

- Stanley, D. (2018). apaTables: Create American Psychological Association (APA) Style Tables. R package version 2.0.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=apaTables

- Statistics Norway. (2019). Gjennomføring ved universiteter og høgskoler. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/statistikker/hugjen

- Strenze, T. (2007). Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence, 35(5), 401–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004

- Trolian, T. L., Jach, E. A., Hanson, J. M., & Pascarella, E. T. (2016). Influencing academic motivation: The effects of student-faculty interaction. Journal of College Student Development, 57(7), 810–826. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1845973826?accountid=8579 https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0080

- Vallerand, R. J., & Bissonnette, R. (1992). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational styles as predictors of behavior: A prospective study. Journal of Personality, 60(3), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00922.x

- Vallerand, R. J., Fortier, M. S., & Guay, F. (1997). Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), 1161–1176. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1161

- Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4101_4

- Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C. P., & Soenens, B. (2010). The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. In T. C. Urdan, & S. A. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement, v. 16A—The decade ahead: Theoretical perspectives on motivation and achievement (pp. 105–165). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.246

- Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Verstuyf, J., & Lens, W. (2009). ‘What is the usefulness of your schoolwork?’ The differential effects of intrinsic and extrinsic goal framing on optimal learning. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104320

- Vossensteyn, H., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., Hovdhaugen, E., & Wollscheid, S. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe: Main report. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.767

- Williams, G. C., Grow, V. M., Freedman, Z. R., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.115

- Waaler, R., Halvari, H., Skjesol, K., & Bagøien, T. E. (2013). Autonomy support and intrinsic goal progress expectancy and its links to longitudinal study effort and subjective wellbeing: The differential mediating effect of intrinsic and identified regulations and the moderator effects of effort and intrinsic goals. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(3), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656284