ABSTRACT

This article is based on a case study of the school life of Fatou, a newly arrived adolescent student with limited experiences of formal schooling. Drawing on Goffman’s theories on impression and stigma management, the article explores the techniques employed by Fatou in order to pass as a “normal” student in the mainstream classroom. The results point to the significance of institutional frameworks in these efforts, and show how Fatou and her teachers collectively employ different impression management techniques in order to downplay the mis-match between Fatou’s prior knowledge and the academic demands of the classroom. As a result, it is argued that for Fatou, school becomes a place where, rather than learning subject content, she is “learning to pass”.

Introduction

In maths, Fatou is actually at grade two or three level. But she is in grade seven taking grade seven maths. So, the things she learns … Let me put it like this: she has learned to run before she can walk. She has not learned the basics at all.Footnote1 (Recorded meeting, 21 September 2017)

In line with an ethnographic tradition, which seeks to understand local classroom practices in light of changes in the social and political landscape, the study’s point of departure is twofold. Firstly, Swedish authorities (SOU Citation2017) have reported a sharp increase in the proportion of newly arrived students with limited schooling in recent decades. Secondly, it has been argued that Swedish compulsory schools remain poorly adapted to organising teaching for this student group (SOU Citation2017).

By and large, Swedish compulsory school is guided by an inclusive ideal, which, among a wide range of different ideas, entails the view that students should, as far as possible, be placed in mainstream classes (Isaksson and Lindqvist Citation2015). Different forms of “special” teaching groups do, however, still exist. This applies in the case of the organisation of the education for newly arrived students.Footnote2 Hence, if a newly arrived student “lacks sufficient knowledge in Swedish to be able to benefit from the ordinary teaching” (Skolverket Citation2016, p. 49), they may be placed in separate teaching groups called preparatory classes. Similarly to other exceptions to the inclusive ideal, this practice is strictly regulated. The school law prohibits students from being taught full-time in the preparatory class and from spending any longer than two years in it. Policy recommendations also emphasise that students should leave the preparatory class “as soon as possible” (Skolverket Citation2016, p. 8) and that the maximum placement of two years should only be applied in exceptional cases (Prop. Citation2014/15:45). The current policy thus promotes rapid participation in and complete transition to a mainstream teaching group.

In an attempt to facilitate suitable class placements and to better meet each student at their individual level, municipalities are, since 2016, obliged to carry out a screening of newly arrived students’ previous knowledge (Skolverket Citation2016). Placement in an “age appropriate” class is nonetheless “strongly recommended in the legislation due to social reasons” (Tajic and Bunar Citation2020, p. 3). These recommendations – i.e., rapid integration into an age-appropriate class – reflect the importance that is placed within Swedish compulsory school on students’ participation in age-homogeneous classes (Bartholdsson Citation2007). As in many other school systems, age here constitutes a fundamental organising principle whereby students are sorted into grades and classes. Since school years are normally not repeated in Sweden (SFS Citation2011, p. 185), academic demands are thus aligned, and increase, with the student’s age. At compulsory school level, no alternative structure exists that specifically targets students whose school background conflicts with this logic (cf., SOU Citation2017). Hence, a student who arrives in Sweden without previous schooling, at an age that matches the later grades of compulsory school will in many cases be placed in a grade that matches their age but clashes with their prior (school subject) knowledge. How students in this situation navigate in the mainstream setting thus appears as an important empirical case for exploration.

In this article, I will explore the strategies employed by Fatou in order to manage in the mainstream classroom. The focus will be on her attempts to pass as a “normal” student in a classroom setting in which her prior knowledge and experiences do not match with the demands and expectations of the institution.

Research Context

The research interest in education for newly arrived students has grown significantly in the Scandinavian context in recent decades. Attention has also increasingly been directed towards individual, institutional and ideological positioning in relation to inclusion, belonging and exclusion for these students (Bunar and Juvonen Citation2021). A relatively large body of research has explored the effects of so called “mainstreaming” vs. separate teaching practices for newly arrived students and has thereby contributed to the on-going discussion on the many conflicting conceptions of the meaning of “inclusive education” (cf., Armstrong, Armstrong and Spandagou Citation2010). Several studies have pointed critically to how separate teaching practices for newly arrived students may lead to social exclusion, and that they rely on – and/or reinforce – a deficit construction of newly arrived students (e.g., Hilt Citation2017; Bunar and Juvonen Citation2021). However, studies have shown that a physical placement in the mainstream setting can also have exclusionary effects if it is not accompanied by adequate pedagogical adjustments (e.g., Nilsson Folke Citation2017).

Few Swedish studies have inquired into the school situation for the sub-group of newly arrived compulsory school students who lack, or have limited, experience of formal schooling (SOU Citation2017). However, existing literature focusing on newly arrived students more generally indicates that students with limited schooling are considered the “biggest losers” in models that promote rapid inclusion into mainstream settings (Tajic and Bunar Citation2020, p. 11). A small body of research from the US and Australian contexts has depicted how some of these students experience mainstream educational settings. A recurring story is that the students are faced with academic demands “of overwhelming difficulty” (Brown, Miller and Mitchell Citation2006, p. 158), thus, experiencing school in terms of a series of failures and a sense of learning very little or even nothing at all (e.g., Woods Citation2009; Roy and Roxas Citation2011). Students’ strategies to handle these situations and avoid shame are central in some of the studies that have depicted the schooling experiences of this student group.

In an ethnographic study in a US high school, Valenzuela (Citation1999, p. 134), for example, finds that there is a “stigma attached to ‘preliterates’”, a term used by teachers to refer to students with immigrant backgrounds and limited experiences of schooling. This is confirmed by the students, according to whom teachers and other students treat them “like if we had a disease” (Valenzuela Citation1999, p. 135). As a consequence, students express a reluctance to ask teachers or classmates for help, in part because such attempts are regarded as futile but mainly to avoid exposure of their incapabilities. Similarly, an ethnographic inquiry (Dávila Citation2012) into the school situation for a group of refugee US high school students with limited formal education, concludes that the students’ “academic and linguistic struggles” are neutralised through their quiet and obedient behaviour. This behaviour is put forward as a way for students to “stay afloat” and remain welcome in their mainstream classes (Dávila Citation2012, p. 139, 144). Adaptive techniques are further described by King and Bigelow (Citation2012), who explore how two high school students with no previous schooling navigate in a US English-as-a-second-language classroom in order to “do school”. The authors use this term to refer to strategies employed by the students to get school tasks done but that did not seem to lead to learning, at least not of the subject content intended by the teacher. King and Bigelow suggest that rather than being learning strategies, these strategies should be understood as “coping mechanisms” or “survival strategies” (p. 177). Similar conclusions was drawn from a case study of a third-grade student with little previous schooling (Platt and Troudi Citation1997). The findings show that the student developed a large repertoire of “coping strategies” to get by in a classroom where little consideration was taken of her academic needs. These strategies include “stalling techniques”, such as: “writing, erasing, looking for materials” (Platt and Troudi Citation1997, p. 43). The authors conclude that while these strategies were essential for the student’s short-term socialisation as a mainstream student, in the long run they prevented her from “catching up” academically with her peers.

The above studies have brought attention to mechanisms of student’s “coping strategies” and how these, in various ways, are put to work in classrooms in the US context. In addition to an inquiry into adjustment techniques of an individual student, the present study aims to explore how such strategies emerge and are upheld collectively, and how this relates to institutional frames.

Theory

To account for and analyse Fatou’s “response to the spot [s]he is in” (Goffman Citation1963, p. 151), I draw on the works of Erving Goffman and his concepts of impression and stigma management. Goffman’s microsociology is based on the assumption that social life relies on “the sharing of a single set of normative expectations”, collectively upheld by rituals, repetition and routines (Goffman Citation1963, p. 152). A stigma can be defined as “an undesired differentness” (Goffman Citation1963, p. 15) that makes an individual unable to abide by these norms. Importantly, an attribute is not seen as discrediting or crediting in itself, but dependent on expectations specific to the institution, context or setting in which it is defined. For example, it is unlikely that attributes such as lack of literacy or numeracy skills are stigmatising for a 6-year-old or for a person living in a predominantly oral society. But, as suggested above (e.g., Valenzuela Citation1999), for a teenager in a Western mainstream school setting, they may very well be.

Goffman (Citation1963) outlines a number of strategies to navigate a stigmatised position and reduce its potential negative effects. A common strategy entails the concealment of the stigma and techniques to “pass as normal”. Due to the great advantages in being positioned as “normal”, Goffman (Citation1963, p. 95) argues that: “almost all persons who are in a position to pass will do so on some occasions”. Passing techniques can be understood as an application of the impression management that takes place in all social interactions and that involves attempts to control the impression of the self given to others (Goffman Citation1956). Using dramaturgical metaphors, Goffman argues that the goal of impression management is acceptance from the audience, in other words that the audience perceive the performer as he or she wishes to be perceived. Or at least, that the audience gives the appearance of accepting the performance, thus allowing the performer to avoid “losing face” or being exposed to shame. A person who wishes to “pass as normal” is similarly dependent on cooperation and tactfulness from their surroundings (Goffman Citation1963). In addition to passing techniques used by the individual, Goffman’s theoretical framework has thus made it possible to analyse processes of mutual adaption between a person in a stigmatised position and their surroundings.

However, Goffman’s framework is insufficient to explain the specific “institutional matrix” in which Fatou, her classmates and teachers are embedded (Jackson Citation1968, p. 176). To analyse school as an institution with its specific forms of interaction, rituals and norms, I, therefore, turn to Jackson (Citation1968) and his study Life in Classrooms. Jackson divides the demands and interaction orders of the classroom into two major types: academic and non-academic, where the latter refers to the institutional rituals and routines through which students are socialised into specific characteristics and behaviours. Desired student behaviours include, for example, cooperativeness, docility, showing interest and a willingness to work hard. Such demands – that unlike those of the official curriculum are not formally required but tacitly expected – “form a hidden curriculum which each student (and teacher) must master if he is to make his way satisfactorily through the school” (Jackson Citation1968, pp. 33–34). In relation to Goffman’s theoretical framework, Jackson’s perspective enables a less individual-orientated analysis that allowed me to explore the impact of certain aspects of a school’s institutional rituals and routines in processes of stigma management.

Method and Material

This study was conducted as a part of a larger ethnographic study carried out between 2016 and 2018, with the overarching aim of inquiring into how newly arrived students with limited prior schooling are positioned and approached within the framework of Swedish compulsory school. This article draws on data produced at one of the three schools included in this study, Anchor School.

Anchor School is a compulsory school located in a large Swedish city. The school is what you might call a “multi-ethnic” school: more than 80 per cent of the students have either immigrated to Sweden themselves or have parents who have immigrated. In comparison with the national average, the proportion of newly arrived students is also high.Footnote3 Thus, both students and staff at Anchor School are used to a relatively continuous influx of newly arrived students. Albeit not entirely frictionless, the school’s approach towards this student group is therefore well established: At their enrolment, all newly arrived students are assigned to a mainstream class while simultaneously being placed in a preparatory class. In line with a common arrangement of this teaching practice nationally, most students initially spend most of their school days in the preparatory class, and then gradually take more and more subjects with their mainstream class (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016). The speed of this transition is individual, but most newly arrived students at Anchor School transfer completely to mainstream teaching after about one year.

The field work was carried out over a period of one year, during which a combination of compressed and selective intermittent ethnography (Jeffrey and Troman Citation2004) was employed. A compressed phase of the field work began in the autumn of 2016, when Fatou was in 6th grade. Fatou was then 12 years old and had lived in Sweden and been enrolled in Anchor School for one year. She was identified by school staff as a student with no previous schooling experience on her arrival in Sweden, and therefore as a suitable student to follow more closely. The statement below from Fatou’s Individual Education Plan (IEP)Footnote4 contains information provided by the school at this point in time. This particular statement is made in relation to the subject of English:

Fatou is relatively newly arrived, and was illiterate upon her arrival in Sweden. Since she has never attended school, she is in need of basic English so that she can start her journey from the beginning (Document, Anchor School, 2016).

This study follows the ethical guidelines issued by the Swedish Research Council, which means, for example, that all participants have given their active consent to participateFootnote6 and that the name of the school as well as the names of participants have been anonymised through the use of pseudonyms. As Murphy and Dingwall (Citation2001) point out, however, an instrumental following of an ethical “checklist” constitutes no guarantee that the study will avoid harm to its research participants. This is perhaps especially true in relation to school-based research carried out with children, whose freedom to choose to reject participation can be questioned (Morrow Citation2008). Regarding the ethical considerations taken in relation to this specific study, I have taken into account that Fatou is in a vulnerable position, and that my presence in her school environment and the depiction of the same can be regarded as an intrusion into a fragile situation (cf., Bigelow and Pettitt Citation2016). I have thus continuously made efforts to avoid putting Fatou in uncomfortable situations where she could feel singled out or exposed. I have, for example, interviewed other students in her class and also observed lessons when she was not present. As a result of these strategies not to draw attention to Fatou, we never developed a close relationship. One negative effect of this is reflected in the result section of the article, where her “voice” is perhaps more absent than one would have wanted. At the same time, this distance can be seen as a way of protecting her.

In these ways, I have tried to prevent harm to Fatou, but to fully eliminate this risk must be considered impossible (cf., Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). It could, for example, still be argued that Fatou is exposed in the presentation of the study’s results, albeit in an anonymised form. Also, my efforts during field work to avoid her exposure involved a certain amount of dishonesty – or impression management if you will – which could also draw criticism from an ethical point of view. All in all, I have nevertheless made the judgement that the potential harm caused by this study was reduced by my efforts, and that the benefits of illuminating the school situation of Fatou outweigh the remaining potential harm.

The analytical process has been ongoing since the start of the fieldwork and has consisted of a recurrent process of “shifting back and forth” between the theoretical framework and the empirical data (Willis and Trondman Citation2000, p. 399). While the analytical focus of this article is empirically grounded, in the sense that it emerged from what I perceived as recurrent patterns in the fieldwork, the data produced were coded, categorised and analysed primarily with the help of central concepts from the theoretical framework outlined above. The presentation of the results is concentrated on the ways in which Fatou and her teachers managed her stigmatised position, which are discussed under three sub-headings: Attempts to pass, A good adjustment and A phantom acceptance.

Attempts to Pass

Fatou’s mainstream class was described by the teachers as a positive and high-achieving class. This was confirmed by my observations, which showed a classroom setting in which it was considered high status to score high on tests and to have the correct answers to classroom questions. The classroom work was also largely characterised by neatness, diligence and a focus on school tasks. Early during the field work, it became evident that while Fatou seemed – in these respects – adjusted to the social order of the classroom, she was unable to cope with the academic demands. Further, much of Fatou’s activities in the classroom seemed directed at concealing these academic struggles. An excerpt from an English lesson depicts a typical lesson in Class 6A with regard to the structure of the lesson as well as Fatou’s behaviour.

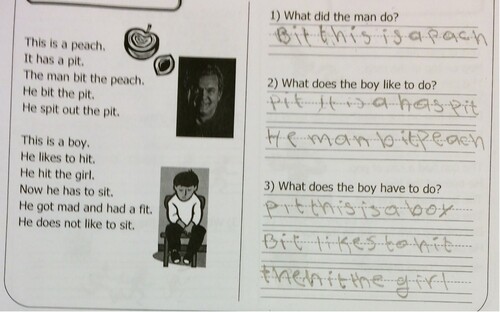

It’s 8 AM and the lesson is getting started. The teacher asks the class: ‘You know what to do?’ Some students answer yes, open their computers and start working, while others do not seem to know what to do. Fatou is one of the latter. After a while, the teacher gives handouts to the inactive students and instructs them to read the text and answer the reading comprehension questions. After receiving her assignment, Fatou looks at it for a long time. She then takes out her phone and uses the dictionary. She turns the page, and looks at the new page for a long time. Many of the students cooperate in pairs or in groups but the girl that was initially sitting next to Fatou changed her seat to collaborate with another student, so Fatou sits alone. The teacher walks by her seat and asks her: ‘How is it going? Is it going well?’ Fatou nods, and he continues to the next group. A while later, the teacher comes back to Fatou and sits beside her. He asks what part of the task she finds difficult. When he does not get any response, he continues by more or less telling her the answer to the first question. When he leaves, Fatou slowly begins to write. She then erases everything and starts over. When the lesson ends, all students leave their assignments on their benches for the teacher to collect. I am then able to observe and photograph Fatou’s assignment, included below. (Field notes, 29 November, 2016)

As exemplified above, Fatou remains reluctant, not only to raise her hand and call the teacher over, but also to expose her difficulties when he comes over anyway. By carefully looking at the handout, checking her dictionary, looking for materials and erasing and re-writing – what Platt and Troudi (Citation1997) refer to as “stalling techniques” – I suggest that she is trying to avoid attracting the teacher’s attention. Also, her attempt at answering the questions can be interpreted as primarily an effort to, at least temporarily, conceal her difficulties and stay unnoticed in the classroom. Fatou displayed this behaviour consistently throughout the field work, during which I very rarely – if ever – saw her ask teachers or classmates for help. Instead, she continuously tried to handle her assignments in ways similar to those she used in this English lesson. This was commented on in the following way by Simon, one of her teachers:

She thinks that she knows the right answer, but she doesn’t […] And that is also a sign of a lack of self-awareness. She thinks: ‘yes, I know the right answer to this’ and then she sits there and thinks she’s doing fine, though she’s really writing pure gibberish. (Recorded meeting, 21 September, 2017)

The teacher instructs the students to do a quiz on the physics of sound. The quiz is online and the multiple choice questions, involving topics such as sound waves and frequency, are displayed on the white board via a projector. The students use their computers or mobile phones to answer the questions. When they log in, they choose an alias. Fatou uses ‘Sara’ as an alias while her classmates all use their real names. After responding to the first question, Fatou quickly put her cell phone on her desk with the display facing the desk, so nobody can see if she is right or wrong. After a while, she takes a quick peek at the display and when she discovers that she has the right answer, she turns the phone with the display upwards and lets it lie there. On this particular question, only three students have the correct answer. One student shouts out: ‘Who was right?’ Another student replies: ‘Admir!’ The student sitting next to Fatou calls out: ‘And Fatou!’ Another boy says: ‘Did Fatou have the right answer!?’ with manifest surprise in his voice. He and the students next to him look at each other with smug smiles. On the following questions, Fatou continues to hide her answers by turning her phone upside down on her desk. (Field notes, 9 November, 2017)

A Good Adjustment

Above, I have outlined examples of Fatou’s attempts at disguising her inabilities to comply with academic demands. However, as demonstrated by the statements from Simon and her classmates, Fatou is not successful in these attempts. As pointed out by Goffman (Citation1963, p. 153): “[a] mere desire to abide by the norm […] is not enough”, and it seems as though Fatou lacks the prerequisites needed to be able to pass as a competent or ordinary student. In cases such as these, when it is not feasible to conceal a stigma, Goffman (Citation1963) outlines alternative, or complementary, strategies. One of these is referred to as a “good adjustment”, whereby a person in a stigmatised position “cheerfully and unself-consciously” adapts in ways that will avoid exposing people in their surroundings to discomfort or embarrassment (Goffman Citation1963, p. 146).

This concept can be used as a way to understand why, in my interview with her, Fatou said nothing to indicate that she struggles with classroom assignments or that she is unhappy with her school situation in any way. On the contrary, with few exceptions, she depicted a nearly ideal school life. This is exemplified by Fatou’s answer when asked what she does when encountering a classroom task that she does not understand:

I raise my hand and the teacher comes to me, and I ask him […] And then the teacher explains the purpose of the task and what is required (Interview, Fatou).

Further, this answer can be interpreted as a sign of loyalty to the school and her teachers. Hence, while the classroom observations suggest that both Fatou and her teachers are struggling to meet institutional demands and expectations, she depicts a scenario in which both parties fulfil their part of the agreement. This can be understood as a “good adjustment”, in that Fatou accepts her position and acts “so as to imply neither that [her] burden is heavy nor that bearing it has made [her] different” (Goffman Citation1963, p. 147). Hence, she has learned that the model student needs “to suffer in silence” (Jackson Citation1968, p. 18). In the following section, I will explore how this behaviour can be seen as part of a silent agreement between Fatou and her teachers.

A Phantom Acceptance

As already argued, the management of a stigma is a collective effort, in which a person’s aim for acceptance is dependent on cooperation from their surroundings (Goffman Citation1963). As a student, Fatou is reliant on “the approval of two audiences” whose tastes, interests and investment may differ (Jackson Citation1968, p. 24). As exemplified earlier, Fatou’s classmates could, occasionally, call her out, in the sense that they explicitly positioned her as different, and less capable, than the rest of the class. In this section, I will shift the focus towards Fatou’s teachers, a group that emerged as significantly more tactful and cooperative with Fatou. Several of the teachers talked to me about Fatou’s strong desire to “be like the other kids in her grade” (Interview, Sally). As already indicated, the teachers seemed to adapt to this inclination in the sense that they did treat Fatou in similar ways to the rest of the class. However, interviews and field notes suggest that Fatou is not perceived as similar to “the other kids”. The excerpts below from a lesson in mathematics followed by my subsequent conversation with the maths teacher provide an illustration of this duality.

It is Friday morning and 7A has a maths test. When the students enter the classroom, the benches are spread apart with two papers placed on each bench. One contains the test and one is for students to write their answers. The students are asked to take a seat, after which the teacher, Susan, gives a short introduction. During the remainder of the lesson, the students write in silence, with the exception of occasional questions to Susan, who walks around and helps students who ask for help. Unlike most of the students, Fatou does not ask for any help. She writes slowly on her paper, with long pauses when she is seemingly doing nothing at all. During these pauses, she places the test paper on top of her answer paper, so that her answers are concealed from others. Five minutes before the lesson ends, she submits her test. (Field notes, 9 November, 2017)

‘There is no point in her doing the test, there is no way that she is going to pass it. I don’t understand why she’s not in the preparatory class!’ […] When we look at Fatou’s test together, Susan has her suspicions confirmed, when she is unable to find any correct answers. Apologetically, she tells me: ‘I didn’t plan anything special for her, she is not my responsibility!’ (Field notes, 9 November, 2017)

This silent agreement is, however, challenged by my presence, which forces Susan to display Fatou’s test results to an outside actor. In this way, Fatou’s shortcomings are exposed, whereby Susan’s ambition to appear as a competent teacher is also threatened. Against this background, I suggest that Susan’s rather remarkable disclamation of responsibility for Fatou’s education can be understood as a way for Susan to save her own face in front of me. However, it also signals that Fatou is not accepted as a full member of the class, thereby illuminating the conditionality of her acceptance (cf., Goffman Citation1963).

The abrupt switch between the different scenes in this example constitutes an illustration of the ambiguous performances repeatedly – albeit not always as manifestly – displayed by Fatou’s teachers. This will be further explored in the following excerpts from my interview with Johan, a teacher in the preparatory class where Fatou has a few lessons per week. Despite the fact that these excerpts are derived from the same interview, divergent – and in part, contradictory – images of Fatou’s school life are presented, depending on the imagined audience. In the first quote, Johan lets me know that Fatou has occasionally been sad during lessons.

I believe that what makes her so sad sometimes, is that she feels – and knows – that: ‘I'm not doing well and this is too difficult’. And then a tear comes. (Interview, Johan)

When I meet her parent […] I would like to be able to say that: ‘decisions have been taken and this and that will happen to Fatou’. But now it feels like I don't have much to say to her dad that would make him happy. But that is also the reality. I can say that Fatou is still here every day and that she is happy. And she keeps on working.

Discussion

The article has provided insights into how a newly arrived student with limited schooling and her teachers operate in order to handle the mismatch between institutional demands and the experiences and needs of a student. The findings suggest that Fatou and her teachers are mutually, and in different ways, adapting to this situation. This can be described as a process in which many actors, including the institution as such, are involved in – and influence – different performances. For Fatou, this means that while she is unable to meet the academic demands of the mainstream teaching, she has clearly learned to master some of the institution’s unwritten rituals and codes. The results show examples of her attentive and skilful navigation of the complex demands and expectations that are placed on her. As demonstrated, this navigation includes attempts at concealing her academic incapabilities, but also a “good adjustment”, whereby she employs a compliant and accepting attitude towards a learning environment that clearly does not cater to her needs.

Fatou’s adaption can be assumed to be carried out under the promise of “the great rewards in being considered normal” (Goffman Citation1963, p. 95). As exemplified in the analysis, Fatou’s good adjustment is also rewarded by her teachers, in the sense that they seemingly accept her performance, at least in the classroom arena. A “phantom normalcy” (Goffman Citation1963) is in this way staged in which Fatou is framed as a student who is able to perform on an “age adequate” level, at the same time as she is evidently not perceived as such. Taken together, these processes have been analysed and described here as a tacit agreement between Fatou and the school, whereby the ritualised orders of the classroom – as well as the faces of Fatou and her teachers – can be maintained.

In this way, acquisition of subject knowledge, in Fatou’s case, becomes subordinated to institutional expectations regarding conduct, order and predictability (cf., Platt and Troudi Citation1997). Here, I am not suggesting that this is a prioritisation that is actively and consciously carried out by individual teachers, but rather that this is underpinned by institutional expectations and frames in which “behavioural” rather than academic demands are prioritised (Jackson Citation1968). Another aspect of the focus on reducing the exposure to shame or embarrassment, is that the institutional logics that make Fatou “abnormal” in this setting remain largely invisible and unexplored. This is reflected in some of the teachers’ actions and utterances, which might appear to position Fatou as both incapable and unworthy of the same pedagogical attention as the other students. Here, it should, however, be mentioned that there are also teachers who talk about Fatou in considerably less deficit-oriented ways, but that does not stop them from still having huge difficulties pitching the subject content at the right level for her.

The focus of this article has been on institutional face-to-face interactions deriving from situations in which an individual has reasons to conceal some of her attributes. Naturally, these situations cannot ‘be fully understood without reference to the history, the political development, and the current policies’ (Goffman Citation1963, p. 151). I therefore want to draw attention once again to two organisational features of Swedish compulsory school that are likely to define and set limits to the encounters depicted in this article: First, the age-based organisation, whereby a connection between level of knowledge and age is implicitly naturalised. Secondly, and related to the first, the ideal of inclusion that entails the idea that newly arrived students should, as soon as possible, be integrated into a mainstream class, which implies a class with students of their own age.

This article is, however, not critical of the organisational principle of a rapid inclusion into mainstream classes per se. While Fatou is physically placed in a mainstream class, she is included in what many scholars would refer to as a “narrow” or “reduced” way (e.g., Armstrong, Armstrong and Spandagou Citation2010; cf., Bunar and Juvonen Citation2021), as she frequently lacks individually tailored support measures and attendance to her pedagogical needs. Also, this study is based on the case study of a single student and does not allow me to entangle all the factors that lead to the situation that I have observed. Nevertheless, in a policy discourse which increasingly places emphasis on the importance of a rapid integration into mainstream classes for newly arrived students, I suggest that the findings from this article are relevant to consider.

This study does not attempt to suggest solutions but makes a contribution to the on-going discussion on the “right” model for education for newly arrived students (cf., Nilsson Folke Citation2017) and associated explorations of the concept of inclusive education. It points to the difficult situation in which Fatou and her teachers are placed and analyses the everyday logics that allow such practices to continue. Here, I suggest that the case of Anchor School and Fatou constitutes an unusually explicit (yet not unique) example, through which processes that are likely to occur in all classrooms, and involve all kinds of students, are highlighted (cf., Jackson Citation1968).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 All quotations and transcripts are translated from Swedish by the author of this article.

2 A student is considered newly arrived for four years after their arrival to Sweden from another country (Skolverket Citation2016).

3 Data on Anchor School was gathered from Skolverket (Swedish National Agency for Education (SiRiS), http://siris.skolverket.se/.

4 An IEP is a document that schools are required to set up for students who are considered to be at risk of not reaching the knowledge requirements in one or several subjects.

5 Since Fatou and I did not share a common language in which we could communicate fluently, this interview was carried out with the help of an interpreter.

6 In the case of students under the age of fifteen years, parental consent was obtained. Information about the study was also communicated to Fatou with the help of an interpreter.

References

- Armstrong, A. C., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2010). Inclusive education: Policy and practice. Routledge.

- Bartholdsson, Å. (2007). Med facit i hand: normalitet, elevskap och vänlig maktutövning i två svenska skolor. Diss. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, 2007. Stockholm.

- Bigelow, M., & Pettitt, N. (2016). Narrative of ethical dilemmas in research with immigrants with limited formal schooling. In P. D. Costa (Ed.), Ethics in applied linguistics research: Language researcher narratives (pp. 66–82). Routledge.

- Brown, J., Miller, J., & Mitchell, J. (2006). Interrupted schooling and the acquisition of literacy: Experiences of Sudanese Refugees in victorian secondary schools. Australian Journal of Language & Literacy, 29(2), 150–162. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.157075354919791.

- Bunar, N., & Juvonen, P. (2021). ‘Not (yet) ready for the mainstream’– newly arrived migrant students in a separate educational program. Journal of Education Policy, 1–23. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.1947527.

- Dávila, L. T. (2012). ‘For them it's sink or swim’: Refugee students and the dynamics of migration, and (dis) placement in school. Power and Education, 4(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.2304/power.2012.4.2.139

- Goffman, E. (1956/1990). The presentation of self in everyday life. Penguin.

- Goffman, E. (1963/1990). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Penguin.

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.) Routledge.

- Hilt, L. T. (2017). Education without a shared language: Dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in Norwegian introductory classes for newly arrived minority language students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(6), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1223179

- Isaksson, J., & Lindqvist, R. (2015). What is the meaning of special education? Problem representations in Swedish Policy documents: Late 1970s–2014. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(1), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.964920

- Jackson, P. (1968/1990). Life in classrooms. Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Jeffrey, B., & Troman, G. (2004). Time for ethnography. British Educational Research Journal, 30(4), 535–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000237220

- King, K., & Bigelow, M. (2012). Acquiring English while learning to do school: Resistance and accommodation. In P. Vinograd, & M. Bigelow (Eds.), Low education second Language and literacy (pp. 157–182). University of Minnesota.

- King, K., Bigelow, M., & Hirsi, A. (2017). New to school and new to print: Everyday peer interaction among adolescent high school newcomers. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(3), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2017.1328958

- Morrow, V. (2008). Ethical dilemmas in research with children and young people about their social environments. Children’s Geographies, 6(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701791918

- Murphy, E., & Dingwall, R. (2001). The Ethics of ethnography. In P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, & J. Lofland (Eds.), Handbook in ethnography (pp. 339–351). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Nilsson Folke, J. (2017). Lived transitions: Experiences of learning and inclusion among newly arrived students [Doctoral dissertation. University of Stockholm, Sweden]. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1052228/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Nilsson, J., & Bunar, N. (2016). Educational responses to newly arrived students in Sweden: Understanding the structure and influence of post-migration ecology. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(4), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1024160

- Platt, E., & Troudi, S. (1997). Mary and her teachers: A grebo-speaking child's place in the mainstream classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 81(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb01625.x

- Prop. (2014/15:45). Utbildning för nyanlända elever – mottagande och skolgång. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Roy, L., & Roxas, K. (2011). Whose deficit Is this anyhow? Exploring counter-stories of Somali bantu refugees’ experiences in “doing school”. Harvard Educational Review, 81(3), 521–542. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.3.w441553876k24413

- SFS. (2011). 185. Skolförordningen. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Skolverket. (2016). Skolverkets allmänna råd med kommentarer: Utbildning för nyanlända elever. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- SOU. (2017). 54. Fler nyanlända ska uppnå behörighet till gymnasiet. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Tajic, D., & Bunar, N. (2020). Do both ‘get it right’? Inclusion of newly arrived migrant students in Swedish primary schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–15. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1841838

- Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. State University of New York Press.

- Willis, P., & Trondman, M. (2000). Manifesto for ethnography. Ethnography, 1(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661380022230679

- Woods, A. (2009). Learning to be literate: Issues of pedagogy for recently arrived refugee youth in Australia. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 6(1-2), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427580802679468