ABSTRACT

Research in the Scandinavian school context has indicated that physical education (PE) is dominated by activities and values from a sports discourse. The main aim of this study was to explore students’ experiences of two competitive activities provided by the teacher. The participants were 49 students (13–15 years old) and their two teachers from two secondary schools in Norway. Methods included written narratives, interviews, observation, and video recordings of PE lessons. Data were thematically analysed. Results showed that the teacher-facilitated one competitive activity with the aim of winning and another activity with the aim of educating the students. The teacher’s facilitation of the activities influenced the students’ experiences, goals, and effort in these activities. The study shows that it is important that teachers have clear learning outcomes for lessons and make students aware of those learning outcomes, and that students find the lessons useful in their everyday lives.

Introduction

Physical education (PE) in Norway is influenced by a sports discourse (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020). The logic and values of competition in sports, such as high normative performance and test scores, may influence how competitions are perceived by the teacher and students and how the teacher presents competitive activities in PE lessons (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Aggerholm et al., Citation2018; Erdvik, Citation2020; Lòpez-Pastor et al., Citation2013). However, the degree of influence from the logic and values of sports in PE may differ. Competitive activities in PE may be presented similarly to the way they are presented in actual sports but may also “look-like-competition” inspired by sports (Erdvik, Citation2020; Larsson & Karlefors, Citation2015; Ward & Quennerstedt, Citation2016). Depending on how the competitive activities are presented, being competent in PE may be based upon students’ performance and effort in competitive activities and physical tests (e.g., Aasland et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the intentions behind competitive activities may differ from the intended meaning and aims of competition in PE. According to Hovdal et al. (Citation2020, Citation2021), Dewey (Citation2015) and the Norwegian education programme (UDIR, Citation2019a), activities in PE, including competitive activities, should facilitate experiences and learning that are useful for society and the students within the society. We, therefore, investigated the consequences of the way competitive activities are facilitated in PE by considering students’ experiences, goals, and effort. In the following, we present research on experiences of competition in PE.

Research on PE in Norway indicates that most students appreciate the subject (Moen et al., Citation2018; Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015). However, the logic derived from competitive sports in PE lessons seems to influence those students that participate in sports in their leisure time to enjoy the subject more than students who do not (Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015). Providing competition in PE may lead to either positive or negative meaningful experiences for students (Beni et al., Citation2017). It is, therefore, understandable that 43% of PE students in Säfvenbom et al.’s (Citation2015) study reported that they would like the subject to be taught differently. Students vary in whether they like PE, in general, or competitions in particular, and whether they find competition in PE to be useful or meaningful (Beni et al., Citation2017; Erdvik, Citation2020; Munk, Citation2017; Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015; Walseth et al., Citation2017). Experiences of competition that are ambivalent may hinder the student’s potential for personal development and learning in the subject (Erdvik, Citation2020; Nyberg & Larsson, Citation2014; Redelius et al., Citation2009; Wilkinson et al., Citation2013). While the studies mentioned (e.g., Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020) have indicated that competitive activities in PE are influenced by sports, they have not focused on how the activities were taught or whether there may be better ways to facilitate competitive activities in PE. Redelius and Larsson (Citation2010) indicated that PE teachers have focused mainly on traditional competitive sports as teaching materials and activities. For instance, pre-service teachers in Norway expected and were more interested in learning multiple games than in learning the nature of teaching in PE (Hordvik et al., Citation2020), which may place their focus on the activity itself, rather than what ought to be taught and what students are expected to learn (Redelius & Larsson, Citation2010). Bernstein et al. (Citation2011) stated that competitive activities should be part of a positive learning context where the created atmosphere should focus on learning, rather than certain outcomes. In this sense, the presentation of competitive activities in PE should be different from the presentation of competition or “looks-like competition” in sports (Larsson & Karlefors, Citation2015; Ward & Quennerstedt, Citation2016).

The presentation of competition should be in accordance with the Norwegian education programme, which states that “students and apprentices shall develop knowledge, competence, and attitudes for mastering their lives and to participate in work and community in the society” (UDIR, Citation2019a, p. 3). The Norwegian PE curriculum emphasizes effort as an important competence goal that should be learned in PE: “Effort in PE includes students trying to solve challenges with persistence and without giving up, demonstrating independence, challenging one’s physical capacity and cooperating with others” (UDIR, Citation2019b, p. 8). Providing effort in competitive activities based on the competitive sports values of winning and social comparison are, therefore, not the same as the educational values of attitudes and competence for students to master their lives (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020; UDIR, Citation2019a). At present, little is known about how teachers present and teach competitive activities in PE in real-life situations and how students perceive these activities. To gain such an understanding, one needs to consider PE activities as open, social and complex systems, and the investigation should take place in actual situations (Dewey & Nagel, 1986; Hovdal et al, Citation2020, Citation2021; Ovens et al., Citation2013; Postholm, Citation2013).

Drawing on Dewey (Citation2015), one must consider the students’ experiences (and learning) in competitive situations. Dewey (Citation2015) stated that schools should be “one of education of, by, and for experiences” (p. 29). These experiences (and learning) should, therefore, be relevant for the students themselves and the society, and the activities should be facilitated by the teacher. Hovdal et al., (Citation2021) introduced a model called “learning through experiences and reflection”. The model considers Dewey’s (Citation2015) educational perspective, using the starting point of students’ experiences and further work on a shared goal that is of relevance for the students themselves and for the society (Hovdal et al., Citation2021; Dewey, Citation2015). In short, the circular model consists of the teacher facilitating a discussion in group/class on a shared goal. Thereafter, the students and the teacher share their experiences and learning relevant to the decided goal, followed up by proposing concrete actions to achieve the goal. If it is a team activity, the students break into small groups and decide how to implement such actions into the activity. If it is not a team game, then the students should probably reflect about how to use concrete actions themselves in the activity (the article does not mention this). After the activity, the group/class once again meet and share their experiences and learning. Based on these experiences and learning, the students and teacher continue with the same goal or change it; therefore, the process is circular (Hovdal et al., Citation2021). Hence, the students’ experiences and learning in competition in PE is influenced by how the teacher presents and facilitates the competitive activities.

In this paper, we look at how the implementation of competition from a sports discourse, or “looks-like-competition” from sports, may influence students’ experiences and goals toward social comparison, and how the implementation of competition may influence students’ experiences and goals towards developing skills and attitudes that may be useful to them in society. Students who focus on social comparison have been considered to have a fixed mindset, whereas students who focus on learning and development have been considered to have a growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2019). The growth mindset provides the best opportunities to help students’ personal development and lifelong learning (Dweck, Citation2019; Warburton & Spray, Citation2017). One of the main reasons for this is that students with a growth mindset may look at obstacles as opportunities for learning and growing, which motivates them to maintain or increase their effort (Dweck, Citation2019). Students with a fixed mindset may see obstacles as having the potential to make them look bad in front of others and thus, may avoid or reduce their effort (Dweck, Citation2019) as a self-handicapping strategy or a hiding technique (Coudevylle et al., Citation2020; Lyngstad et al., Citation2016; Ommundsen, Citation2001, Citation2004). Further, the use of self-handicapping strategies and hiding techniques may depend on the contextual situation (Lyngstad et al., Citation2016). By looking at situations in PE as open, social and complex systems, students’ mindsets are influenced by how the teacher facilitates the activities (Hovdal et al., Citation2020; Dweck, Citation2019), such as whether they focus on social comparison and winning, or on learning and development (Dweck, Citation2019). If the teacher’s facilitation focuses on social comparison and winning, one may expect the teacher to provide opportunities for students to see how they perform in relation to others and obtain positive feedback on social success. If the teacher’s focus is on learning and development, one may expect the teacher to provide opportunities for learning and development and obtain positive feedback on development and learning strategies (Dweck, Citation2019; Yeager & Dweck, Citation2012).

To sum up, the facilitation of competitive activities and testing in PE may draw on logic and values from competition in sports, which may lead to positive and negative experiences for the students and further influence them towards a fixed mindset. The attitudes and values from a fixed mindset are not constructive for students learning to master their lives in society and are, therefore, inconsistent with the Norwegian education programme. In the present study, we investigated students’ experiences and goals in competitive activities in general, and in two competitive activities in particular. One competitive activity reflected competitions in general in a class, and focused mainly on winning, while the other competitive activity focused mainly on learning and development. The aims of this study were twofold: (1) to investigate students’ experiences and goals in competitive situations; and (2) to investigate students’ experiences and goals in one competitive situation where the teacher focused on winning and one competitive situation where the teacher focused on learning and development.

Methods

The present study was a part of a larger research project investigating experiences and learning in PE (Hovdal et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). The study was based on Rorty’s (Citation1982) philosophical pragmatism and pragmatist methodology (Allmark & Machaczek, Citation2018; Feilzer, Citation2010; Morgan, Citation2007). Pragmatism was chosen because its starting point is from human purpose and its endpoint is whatever behoves us to believe will best serve that purpose (Allmark & Machaczek, Citation2018). Dewey (Citation1938) stated that “any problem of scientific inquiry that does not grow out of actual (or ‘practical’) social conditions is factitious; it is arbitrarily set by the inquirer instead of being objectively produced and controlled” (p. 499). Dewey further argued that social science must be in direct relation to the field, whereas in physics, one may use laboratories, where everything is controlled (Delanty & Strydom, Citation2003; Dewey, Citation1938). This suggests that knowledge from social science should grow out of the field, be acquired by controlled observation and exist in actual situations (Dewey, Citation1938).

In this study, a variant of convergent design and triangulation of multiple methods was used (Abdalla et al., Citation2018; Creswell, Citation2014). To enable the various elements to complement each other and to reduce the limitations of each of the single data creation methods, the data creation consisted of a triangulation of written narratives, observations, video recordings and interviews (Appendix). The number of interviews and observations was chosen to ensure that sufficient data were available to understand students’ experiences in the situations (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The participants and the researcher spoke the same language (Norwegian). The quotations in the Results section have been translated into English. The translation of the quotations was undertaken with the support of a professional translator and checked for the original intended meanings (Van Nes et al., Citation2010).

Participants

The participants (13–15 years old) came from two classes from two secondary schools located in the south of Norway. The study started at the end of the students’ eighth-grade year and lasted until the end of their ninth-grade year. In total, there were 49 students (16 boys and 8 girls in one class, 12 boys and 13 girls in the other class) and their two male PE teachers, who were also in charge of the students’ respective school classes. The follow-up interviews in the fifth data creation stage (see Data Creation section and Appendix) consisted of one class (12 boys and 13 girls) and their PE teacher, because of the importance of context when investigating socially situated situations (O’Brien & Battista, Citation2020).

Ethical Considerations

The schools’ principals, teachers and students were informed of the study verbally and in writing, and the students’ guardians were informed in writing. Written consent was obtained from the teachers, students and the students’ guardians. The participants were ensured confidentiality and anonymity (using code sheets separated from the written narratives and anonymous interviews). The video recordings were stored on an external hard drive. This study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD-58504) and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health and Sport Science at the University of Agder.

Data Creation

The data creation process consisted of five stages (see Appendix). The first dataset consisted of written narratives at the end of the students’ eighth-grade year regarding situations (with peers, teachers and tasks) in PE that the students liked the most and least. The second dataset consisted of individual interviews with 12 students and their two PE teachers. These students were selected to facilitate richer data based on the themes created from the first dataset (Patton, Citation2014). The third data creation stage consisted of observation and video recordings of 14 PE lessons (eight in one class and six in the other). The fourth data creation stage consisted of written narratives from all the students, conducted at the end of each PE lesson, concerning the situations they liked the most and the least in the PE lesson. The first four datasets provided the foundation for the fifth data creation stage (see “Creating the Overarching Theme” section below). The fifth dataset consisted of interviews with 19 students from one class and their PE teacher. The follow-up interviews in the fifth data creation stage focused on the students’ experiences and goals in different (competitive) situations in PE and the teacher’s experiences in and reasons for the facilitation of different competitive situations. The main dataset in this article consisted of the observation/video recording from the third data creation stage, students’ narratives from the fourth data creation stage and the interviews of the students and teacher in the fifth data creation stage.

Data Analysis

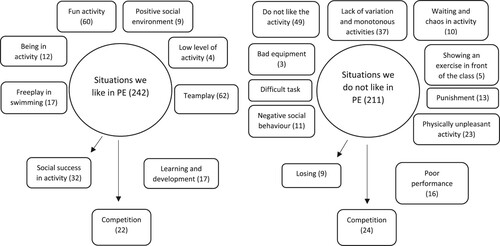

The interviews and video recordings were transcribed into written text, and together with the written narratives and field notes, were used to conduct thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The data were analysed bottom-up using the six basic steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): (1) Familiarizing yourself with the data; (2) Generating initial codes; (3) Searching for themes; (4) Reviewing themes; (5) Defining and naming themes; and (6) Producing the report. The analysis of the narratives, interviews and observation/video recordings were on a semantic and/or latent level (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). As shown in , one may see an analysis on the semantic level of the data creation under the category “Sub-theme”, and an analysis on the latent level of the data creation under the category “Main theme”. The main themes and the sub-themes each provided information on different levels of the overarching theme of “competitive situations in PE”. Therefore, the Results section presents competitive situations in PE in general, and in two specific contrasting competitive situations, to address the aims of the study. Consequently, the main themes and sub-themes will be baked into the result section. In the following section, we show how the overarching theme was created. provides an example of how multiple methods were used to create the main themes and sub-themes. shows the resulting main themes and sub-themes.

Table 1. Creation of main theme from third, fourth and fifth datasets.

Table 2. Overview of the main and sub-themes in this study (from third, fourth, and fifth datasets).

Creating the Overarching Theme

The creation of the overarching theme in this study, competitive situations in PE, came from repeated readings and viewings of the interviews, narratives, field notes and video recordings (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). Based on the first written narratives (first dataset), the students did not like “competition” and “testing and normative pressure”. The teacher said in his first interview that he could use competitions as a way of motivating the students in PE. In the observation and video recordings (third data creation stage), the researcher (main author) noticed students giving up and “not trying” in the wrestling activity. Students were not observed giving up in the running test activity. Students’ written narratives about the wrestling and running test activities (fourth dataset) indicated differences in whether they liked the activities. The students liked or disliked wrestling based on their performance in relation to others. By contrast, students liked or disliked the running test based on their personal improvement. In other words, the goals in the wrestling activity were related to normative success, while those in the running test activity were related to their improvement. This led to an interest in investigating these activities further in the fifth data creation stage. The main findings in this paper are derived from the students’ narratives in the fourth dataset, which led to the use of relevant clips from the video recordings (third dataset) and further interviews of the students and the teacher (general questions and questions based on the video clips) for the fifth data creation stage.

Results

In this section, we first present the students’ experiences of competition through their written narratives which were conducted at the end of each PE lesson, and show their experiences of competition in general. We then present how the teacher provided the situational contexts of two competitive activities and the students’ experiences of these activities.

Students’ Experiences of Competition in PE in General

(below) shows the quantification of qualitative themes (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017) and presents the students’ narratives written after each of the 14 PE lessons (fourth data creation stage). The number of narratives within each theme is shown in parentheses. Situations in “Competition” provided both negative and positive experiences in PE. While the themes “Losing” and “Social success in activities” (such as winning) refer to the results of a competition, the theme “Competition” consisted of experiences within competitions and is slightly more diverse (see ). We, therefore, interviewed the students further about competition in general and within the context of their PE lessons.

Figure 1. The themes created from the students’ narratives written at the end of each PE lesson. The full model is provided for transparency of the resulting themes.

Table 3. Illustration of narratives within the theme competition in (fourth dataset).

The students expressed in their interviews that activities in PE often ended up as a competition. If the activities were not competitive, then the students sometimes perceived them as less important and reduced their effort, as indicated by Ole:

I feel that they do not care as much. Even though the competition is not important. If we are running, then we are not doing what we should be doing exactly. We are running, but not as well as if it had been a competition … I feel that at least my effort and what I am doing becomes better when it is a competition.

The students could further perceive their competence in relation to others in competitions. According to Victoria, not mastering a team running competition could mean that one was not good at it, ran slowly or did not pay attention. She was asked about what it would mean to be running slowly and said it was in relation to others: “If you are running slow and they (other students) catch up with you, then the team loses”. The students could also reduce their effort in competitions if they believed they would lose. Sara expressed it in this way: “Then I do nothing. I do not think really. I do not really think that much about it. I just thought that ‘Oh, then I just don’t care’ [about trying], ha-ha”. These comments were consistent with the observation and video recordings. The goal with the competitions was winning or not losing, as indicated by Stefan:

To win as much as possible—I did not have a goal of winning the whole competition, but to win as much as possible … The goal is to win every match without losing, and to end up in the final and win it. To become the best.

To sum up, competitions could provide both positive and negative experiences for the students and lead to both an increase and a decrease in effort. In the following, we present two competitive situations: one in which the teacher influenced the context by focusing on winning and effort, and another in which the teacher influenced the context by focusing on learning, improvement and effort. These two situations were experienced differently by the students regarding the competitive aspect of the situations.

Experiences of the Wrestling Situation

Wrestling was one of the activities that became competitive in the PE lessons. The wrestling activity was organized so that every student was wrestling at the same time, one student against another. The groups (of two) were wrestling on their own mats, which were placed in a circle around the teacher who stood in the middle. One round lasted until one of the students had won and all groups had to be finished before the next round started. If one pair tied, then they wrestled again while the other students waited and watched. After the first round, the winners went to the next mat, and the losers waited on the mat for the next opponent. After a few rounds, the teacher asked whether anyone had not lost a match yet, and students would raise their hands if they had not. At the end of the wrestling activity, they sometimes had a final match, where two students wrestled and everyone else watched. The teacher gave the following reason for organizing the final: “I think it is because, sometimes, to give recognition to those who, yes, are simply good at it. I think it is a nice thing to do”. In his last interview, the teacher explained why he used competition as motivation:

It is a bit difficult to answer really. It is to trigger the competitive instinct, to make it easier to take the “last step”, to push oneself. Having a goal or something to reach for. It is normally important for motivation, I think …

The teacher used competition as motivation because he himself also became motivated by competition:

Also, I often become triggered if there is some competition. It does not need to be something big, it can be a quiz, Ludo [a board game] or anything. At least, I get triggered by the competition aspect. And I think that is something normal to be [triggered], but to different degrees.

The teacher was further asked about how he motivated the students in the wrestling activity:

Mmmm … er … yes, how do I motivate them? I do not know. I do not always think about how I do it. I can [motivate] during, like in the moment. Then I can, like, cheer them on, and [say] “come on, you can take him”. Or try to get them geared up. Some of the students do not get motivated at all, and almost leave the mat, on purpose. I see that. And I do not put a lot of focus on it, if they do not want to, so … Mostly, I think it works well for the vast majority, and most of them do their best. At least, it seems that way to me.

After a PE lesson that ended with a wrestling activity, the teacher came to the researcher (main author) and said that it seemed that the students liked this activity. However, the student narratives indicated that the students were more ambivalent. There were 19 students in this PE lesson. Different activities were completed, with handball as the main activity, based on the length of time spent. Two students liked the wrestling activity the best in the PE lesson and seven students liked the wrestling activity the least. The students were then interviewed about two wrestling activities they had completed in the PE lessons. The students who disliked these activities said it was because they were “stressful and uncomfortable”, there was “pressure to win” and they had “poor performance compared with others”. One student had goals of “winning”, “not losing” and “doing what the teacher said”. This seemed to be related to the pressure of winning, as expressed by Sara: “It is the competitive instinct. I feel that I almost must win. Yes, I think that is the problem”.

The students who liked the wrestling activities said that this was because they increased their effort because they had wanted to win, and that “it was fun”. These students expressed their goals as “don’t know”, “making an effort”, “winning” and “performing as well as possible”. In contrast to the students who found the pressure to win to be a negative experience, these students seemed to enjoy the pressure, as expressed by Clara: “I am getting a little geared up. I have a bit of a competitive instinct”.

The students’ answers indicated that their goals were mainly winning and not losing, and this could lead to positive and negative experiences.

Experiences of the Running Test Situation

The running test was one activity that did not seem to become competitive in the PE lessons. The students had completed a pre-running test activity before the start of the observation and video recordings in this study. The students had the opportunity to run one to three laps, where one lap was circa 1 kilometre. The students had to work out which length suited them best and then run that number of laps in their post-test. The students’ post-test activity was observed, and a video recording was made by the researcher (main author). In the post-test, the students ran in groups based on their number of laps. In a PE lesson before the post-test, the teacher reminded the students of the importance of training to improve their time. At the post-test, the teacher focused again on their improvement. The teacher said the students’ times aloud at the finish line but did not focus on the normative success. His feedback was related to their improvement and effort. In the following PE lesson, the students answered questions on their computer regarding the running test activity and their improvement or lack thereof as a part of the running test activity. For example, they indicated whether they had improved their time and what the reasons might be. The teacher explained the goal of the running test activity as follows:

There are perhaps several goals, but we have changed the direction over recent years towards the idea that they are going to take a test. Then [they] train, or at least have the opportunity for a period of training, and then take a new test. Thereafter, they reflect on their improvement or deterioration. That is really the main goal. A reflection. What influenced this performance?

Altogether, it seemed that the running test activity focused on the students’ improvement. The teacher was, therefore, asked whether the focus on the students’ personal improvement was intended (in contrast to the “Social success” mentioned in the wrestling activity):

Yes, it is. We have worked on it. That for the running test activity, it is about yourself and your achievement and your improvement. We do not run for a top three, really. And I do not have the impression that they [students] have been that focused on how fast the others ran. Some of them might have some internal competition, maybe. But [if they do], it is likely to be two boys who are at the same level and use it to push each other, which I think is positive. But they are not that occupied with what everyone else did, or what time he or she ran in. It is just positive. “Wow, you did so well”. But yes, the goal in that situation is that they should be concerned with themselves. And their improvement. That is quite clear.

The teacher was asked about how he motivated the students in the running test activity:

I say that if you are going to do a test, then you have to do your very best. If you do not, then the test will not be worth much. And the goal for taking a test is to measure whether your training is working. That is the reason you are testing. I do it myself in my training, in my spare time. Comparing where I am this year, to [where I was] last year, for example. If the training worked well or if I need to do something different. So, the main goal is to teach them that. And in the longer term, maybe they can design and conduct their own test. In other words, trying to create an understanding for why it is important to test, and why we do it.

The students had their post-test in one PE lesson, which directed their narratives towards the running test activity. The students had positive experiences and narratives of the following: the warm-up, that they were cheering each other on, that it was good weather for running, that when they had finished the test run, they felt they had made a good effort and that they improved their time. Their negative experiences and narratives were as follows: it was cold, the running itself, there was not enough time for the test, the teacher said their time aloud at the finish line, the run led to a sore throat, peers were watching when they ran, there was pressure to perform, they did not perform as well as they had hoped and they experienced competition and stress. Overall, the students did not seem to be as occupied with their performance in relation to others, or to indicate that they had “given up”, as they had in the wrestling activity. However, two students said that they did not like it because of the “competition and stress”. These narratives seemed to include the students’ performance in relation to others. Sara said the running test activity was stressful: “It is because we are running with others. That I am running with my friends. I want to beat them, sort of”. Cassandra also said it was stressful:

I do not know, or anything [about the running test being stressful]. The running test activity is talked about a lot—what did you get—and I heard it on the video clip straight away: “what did you get?” immediately after one student passed the finish line. And I think that is the wrong way of looking at it.

Cassandra said that she experienced pressure from talking about the performance and in relation to improving her time. She was, therefore, asked what she thought put her under the most pressure and answered: “Maybe that you have to run faster, or at least run equal to your previous time”.

Overall, the running test activity could be stressful for the students, but not in relation to comparing their performances to others (except for Sara and to some degree Cassandra). This might be further illustrated by David, who was the fastest runner in a group that ran three laps. In his previous narratives, David often wrote that he liked winning and scoring goals the best in the PE lessons. By contrast, after the running test activity, he expressed in his narrative that: “I liked it best when I beat my own time by a minute. It shows that the extra training I put in worked”. In the interview, he expressed that his goal in this activity was: “Getting better, improvement”.

Discussion

Based on the aims of this study and our findings, we discuss how a sports discourse might influence competitions in PE, how competitions could be facilitated in PE and the influence on students’ experiences, goals and effort in the activities. We further consider the possible reasons for students providing effort in the wrestling versus the running test situation. We end the Discussion section by discussing the teacher’s influence on the students’ learning outcomes.

Competitive Activities in PE and Their Complexity

Students might have positive and negative experiences of PE in general, and in competition in particular, and may find competition to be more or less meaningful (Beni et al., Citation2017; Erdvik, Citation2020; Moen et al., Citation2018; Munk, Citation2017; Säfvenbom et al., Citation2015; Walseth et al., Citation2017). The present study showed the complexity of students’ experiences in different competitive activities. The findings suggest that most of the competitions in this study were based on a sports discourse rather than on being educative (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020; Gard et al., Citation2012; Munk, Citation2017). For instance, in the wrestling activity, giving the two students who had not lost a single match a final round, because the teacher wanted to “give recognition to those who, yes, are simply good at it”, would indicate that winning equates to being good at an activity in PE. The teachers’ aims for most competitive activities were to motivate students through social comparison and elicit a high level of effort. One may argue that motivating students through social comparison is a legacy from sports ideologies, in contrast to motivating students for learning and development through competitive activities. The findings indicate that the teacher focused mainly on students providing a high level of effort as a goal for physical exertion, in contrast to maintaining or increasing effort when facing obstacles. The main differences between the mentioned goals (winning versus learning, and a high level of effort in physical exertion versus a high level of effort as a way to learn and develop) is an important aspect, and the goals of maintaining or increasing effort under adversity are important for the students’ learning and development in ways that are useful to them in society, as well as for society itself (Dweck, Citation2019; UDIR, Citation2019a). In this case, we presented two activities to illustrate differences in the facilitation of activities in PE. One competitive situation, wrestling, was facilitated with the logic and values of sports, and another competitive situation, the running test, was facilitated to be educative (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020; Gard et al., Citation2012; Munk, Citation2017). In the wrestling situation, the teacher facilitated the activity in a way so that students’ normative performances were visible to all; there was a final round between the two best students and a winner was declared. We, therefore, argue that this activity was based on the logic and values from sports, or at least, “looks-like-competition” from sports (Erdvik, Citation2020; Larsson & Karlefors, Citation2015; Ward & Quennerstedt, Citation2016). In the running test situation, the teacher facilitated the activity in a way that allowed the students to decide on the number of laps they wanted to run and improve on and highlighted the importance of training to improve between the pre- and post-test, and the students reflected after the post-test on their improvement or lack thereof. As such, the teacher provided a situation for learning and development closer to the educative goal of the Norwegian Education programme (Bernstein et al., Citation2011; Dweck, Citation2019; Redelius & Larsson, Citation2010; UDIR, Citation2019a). The running test situation showed that competitive activities in PE do not have to be based on competitive activities from sports logic and values (Aasland et al., Citation2020; Erdvik, Citation2020). We, therefore, argue that it is not just about the activity, it is also about how the activity is facilitated.

Different Competitive Situations, Different Outcomes?

The growth mindset provides the best opportunities to help the students’ personal development and lifelong learning, and effort when facing obstacles is an important part of personal development (Dweck, Citation2019; UDIR, Citation2019b). Students who reduced their effort and gave up when facing adversity in the wrestling activity may be showing a fixed mindset (Dweck, Citation2019). These students, in contrast to the teacher’s intention, did not become motivated by competition in these situations. Students maintaining or increasing efforts when facing obstacles in the running test may indicate a growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2019). As well as the motivational environments leading to reduced effort through self-handicapping strategies and hiding techniques (Coudevylle et al., Citation2020; Lyngstad et al., Citation2016; Ommundsen, Citation2004), some of the differences may also be attributable to rational choice in both activities (e.g., Dietrich & List, Citation2013). For instance, the teacher’s different ways of presenting and facilitating the situations might influence a student’s adaptation to each situation (e.g., Renshaw & Chow, Citation2019; Sigmundsson et al., Citation2017). In the running test activity, the students’ goals were mainly to improve their time, and their performance was measured by their exact time, rather than in relation to others (e.g., ranking list). One may argue that the rational choice in this activity is to run as fast as possible and not give up on achieving the best possible time. By contrast, this might not be a rational choice in the wrestling activity, where the students’ goals were mainly to win against their opponents and the performance was recorded dichotomously as either a win or a loss. One student said that his goal was to win as many matches as possible, and therefore, his choice of reducing effort and giving up in some matches seemed rational; he provided enough effort if he knew he would win, reduced effort if he knew he would lose and maximum effort if he was not sure whether he would win. Based on his goal in this activity, it seemed to be rational to save energy for the matches where he was not sure whether he would win, and thereby increase his opportunity to win as many as possible. However, although his behaviour (reduced effort in some matches) was rational for the short-term goal (winning as much as possible), it might not be considered rational in the long term regarding personal improvement and mindset when facing obstacles later in life (Dweck, Citation2019; UDIR, Citation2019a).

Teacher’s Influence on Students’ Learning Outcomes

Students may find it difficult to know what they are supposed to learn in PE if the goals or learning outcomes are not well articulated by the teachers (Redelius et al., Citation2015). In the present study, the teacher clearly articulated the learning outcomes in the running test activity, but not in the wrestling activity. As such, the students seemed to be aware that they should learn to test their performance to observe whether they improved in the running test activity, while in the wrestling activity, they seemed to be less sure. In the study of Redelius et al. (Citation2015), students could answer “cooperation perhaps” (p. 647) as a legitimate answer on what they had learned in the lesson when they had nothing else to say (and seemingly did not know what they were supposed to learn). By contrast, students in the present study seemed to be influenced by a sports discourse (e.g., Erdvik, Citation2020) in the absence of well-articulated learning outcomes from the teacher. In fact, it could be argued that the teacher himself was influenced by a sports discourse when his only goal for an activity was high physical exertion. These results indicate the importance of teachers being aware of their learning outcomes in PE lessons and to articulate these learning outcomes well to their students, either through teaching-by-telling or by including the students in the process of creating the learning outcomes (Hovdal et al., Citation2021). The clarity of the learning outcomes for the teacher in this study influenced how the teacher facilitated the activities, what he observed and his further actions (e.g., how he motivated students) in the competitive activities. As already discussed, how teachers facilitate activities influences the students’ experiences, goals and efforts in these activities.

To make the learning outcomes educative for the students, the learning outcomes also need to be meaningful or useful for the students in their everyday lives (e.g., Beni et al., Citation2017; Dewey, Citation2015). As seen in the present study, one student could reduce her effort if she thought she would lose in the wrestling activity and thereby did not care about the activity, while in the running test activity, a student exerted high effort because he wanted to see whether his extra training had worked. Consequently, in this example, the running test activity may arguably be more useful or meaningful than the wrestling activity for the students in their everyday lives (e.g., Beni et al., Citation2017; Dewey, Citation2015). As such, teachers may do well to make the learning outcomes useful or meaningful to the students’ everyday lives (e.g., Beni et al., Citation2017; Dewey, Citation2015).

Conclusion and Implications of the Study

The present study shows the complexity of competitive activities in PE. Students had both positive and negative experiences in competitive activities based on sports logic. Students were able to reduce their effort when the activity was not competitive, when they thought they would perform poorly, or through rational choice to conserve energy to achieve their overall best performance in the activity. Teachers may facilitate competitive activities based on sports logic and values or on educative values. By facilitating the competitive activities as educative, the teacher may focus on the students’ progress and learning, which again, may influence students towards a growth mindset in the activity. This might include, for instance, motivating students to increase their effort by referring to their progress and learning, and the relevance of their learning in their everyday lives. Learning, in this sense, is the physical outcome (improvement) and reflection of why one did or did not improve, and the consideration of what one should try next to improve one’s performance in competitive situations. The present study indicates that teachers should reflect on how they might use competitive activities to create constructive experiences and learning for students that is relevant for the students themselves in society and for society itself (UDIR, Citation2019a). Within the activities, teachers may observe and facilitate situations where the students can articulate their experiences, learning and goals in the activities. This information might influence the teacher to facilitate further situations to move students closer to the activity’s goal of being educative, thereby creating a circular method (Hovdal et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The main strengths of the study consist of the triangulation of the methods (Appendix), including observations/video recordings and students’ and teacher’s experiences in real-world natural settings in PE. These methods allowed us to show that teachers do not necessarily construct different competitive activities in the same way (e.g., focusing on winning or learning), but rather, that their facilitation may be a result of their own experiences, reflections and competence in different activities. The methods further allowed us to show the consequences on the students’ experiences and learning through different types of facilitation in competitive real-life situations. As a result, one may apply the practical implications of the findings to real-world situations in PE.

A limitation of the present study is that we did not include an in-depth investigation of how the teacher reached a level of competence in facilitating activities such as the running test. Further studies should investigate teachers’ socialization processes in PE (e.g., the acculturation, professional socialization and organizational socialization phases) and connect them to concrete actions in natural settings in PE (Templin et al., Citation2016), thereby understanding how teacher competence is learned within the socialization process of becoming teachers. In this way, the present article may contribute to creating a change in the teacher’s facilitation of competitive activities from the logic and values from sports to becoming educational for the students.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aasland, E., Walseth, K., & Engelsrud, G. (2020). The constitution of the ‘able’ and ‘less able’ student in physical education in Norway. Sport, Education and Society, 25(5), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1622521

- Abdalla, M. M., Oliveira, L. G. L., Azevedo, C. E. F., & Gonzalez, R. K. (2018). Quality in qualitative organizational research: Types of triangulation as a methodological alternative. Administração: Ensino e Pesquisa, 19(1), 66–98. https://doi.org/10.13058/raep.2018.v19n1.578

- Aggerholm, K., Standal, Ø, & Hordvik, M. (2018). Competition in physical education: Avoid, ask, adapt or accept? Quest, 70(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1415151

- Allmark, P., & Machaczek, K. (2018). Realism and pragmatism in a mixed methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(6), 1301–1309. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13523

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

- Bernstein, E., Phillips, S. R., & Silverman, S. (2011). Attitudes and perceptions of middle school students toward competitive activities in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 30(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.30.1.69

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Coudevylle, G. R., Boulley-Escriva, G., Finez, L., Eugène, K., & Robin, N. (2020). An experimental investigation of claimed self-handicapping strategies across motivational climates based on achievement goal and self-determination theories. Educational Psychology, 40(8), 1002–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1746237

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Delanty, G., & Strydom, P. (2003). Philosophies of social science: The classic and contemporary readings. Open University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: The theory of enquiry. Henry Holt.

- Dewey, J. (2015). Experience and education. Macmillan Publishing.

- Dietrich, F., & List, C. (2013). A reason-based theory of rational choice. Noûs (Bloomington, Indiana), 47(1), 104–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0068.2011.00840.x

- Dweck, C. S. (2019). The choice to make a difference. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804180

- Erdvik, I. B. (2020). Physical education as a developmental asset in the everyday life of adolescents. A relational approach to the study of basic need satisfaction in PE and global self-worth development [Doctoral dissertation]. Norwegian School of Sport Science. ISBN 978-82-502-0582-6. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://nih.brage.unit.no/nih-xmlui/handle/11250/2677136

- Feilzer, M. (2010). Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: Implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809349691

- Gard, M., Hickey-Moody, A., & Enright, E. (2012). Youth culture, physical education and the question of relevance: After 20 years, a reply to Tinning and Fitzclarence. Sport Education and Society, 18(1), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.690341

- Hordvik, M., MacPhail, A., & Ronglan, L. T. (2020). Developing a pedagogy of teacher education using self-study: A rhizomatic examination of negotiating learning and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 88, 102969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102969

- Hovdal, D. O. G., Haugen, T., Larsen, I. B., & Johansen, B. T. (2021). Students’ experiences and learning of social inclusion in team activities in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 27(4), 889–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X211002855

- Hovdal, D. O. G., Larsen, I. B., Haugen, T., & Johansen, B. T. (2020). Understanding disruptive situations in physical education: Teaching style and didactic implications. European Physical Education Review, 27(3), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20960498

- Larsson, H., & Karlefors, I. (2015). Physical education cultures in Sweden: Fitness, sports, dancing … learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.979143

- Lòpez-Pastor, V. M., Kirk, D., Lorente-Catalàn, E., MacPhail, A., & Macdonald, D. (2013). Alternative assessment in physical education: A review of international literature. Sport, Education and Society, 18(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.713860

- Lyngstad, I., Hagen, P.-M., & Aune, O. (2016). Understanding pupils’ hiding techniques in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 21(8), 1127–1143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.993960

- Moen, K. M., Westlie, K., Bjørke, L., & Brattli, V. H. (2018). Når ambisjon møter tradisjon: En nasjonal kartleggingsstudie av kroppsøvingsfaget i grunnskolen (5.–10. trinn) [Physical education between ambition and tradition: National survey on physical education in primary school in Norway (grade 5–10)]. Høgskolen i Hedmark, oppdragsrapport 1/2018 [Hedmark University of applied sciences, assignment report 1/2018].

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

- Munk, M. (2017). Inclusion and exclusion in the landscape of physical education: A case study of students’ participation and non-participation along with the significance of the curriculum approach in secondary school physical education [Doctoral dissertation]. Aarhus Universitet. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from, https://www.ucviden.dk/da/publications/inclusion-and-exclusion-in-the-landscape-of-physical-education-a-2

- Nyberg, G., & Larsson, H. (2014). Exploring ‘what’ to learn in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 19(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.726982

- O’Brien, B. C., & Battista, A. (2020). Situated learning theory in health professions education research: A scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(2), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09900-w

- Ommundsen, Y. (2001). Self-handicapping strategies in physical education classes: The influence of implicit theories of the nature of ability and achievement goal orientations. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 2(3), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(00)00019-4

- Ommundsen, Y. (2004). Self-handicapping related to task and performance-approach and avoidance goals in physical education. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200490437660

- Ovens, A., Hopper, T., & Butler, J. (2013). Complexity thinking in physical education: Reframing curriculum, pedagogy and research. Routledge.

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Postholm, M. B. (2013). Classroom management: What does research tell us? European Educational Research Journal, 12(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2013.12.3.389

- Redelius, K., Fagrell, B., & Larsson, H. (2009). Symbolic capital in physical education and health: To be, to do or to know? That is the gendered question. Sport, Education and Society, 14(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320902809195

- Redelius, K., & Larsson, H. (2010). Physical education in Scandinavia: An overview and some educational challenges. Sport in Society, 13(4), 691–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430431003616464

- Redelius, K., Quennerstedt, M., & Öhman, M. (2015). Communicating aims and learning goals in physical education: Part of a subject for learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.987745

- Renshaw, I., & Chow, J. Y. (2019). A constraint-led approach to sport and physical education pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1552676

- Rorty, R. (1982). Consequences of Pragmatism: Essays, 1972–1980. University of Minnesota Press.

- Säfvenbom, R., Haugen, T., & Bulie, M. (2015). Attitudes toward and motivation for PE. Who collects the benefits of the subject? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(6), 629–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.892063

- Sigmundsson, H., Trana, L., Polman, R., & Haga, M. (2017). What is trained develops! Theoretical perspective on skill learning. Sports (Basel), 5(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports5020038

- Templin, T. J., Padaruth, S., & Sparkes, A. C. (2016). A historical overview of teacher socialization in physical education. In K. A. R. Richards & K. L. Gaudreault (Eds.), Teacher socialization in physical education: New perspectives (pp. 11–30). Routledge.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet (UDIR). (2019a). Overordnet del – sosial læring og utvikling [Overall responsibility – social learning and development]. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/prinsipper-for-laring-utvikling-og-danning/sosial-laring-og-utvikling/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet (UDIR). (2019b). Læreplan i kroppsøving [Curriculum in physical education]. Retrieved March 25, 2021 from https://www.udir.no/lk20/kro01-05/kompetansemaal-og-vurdering/kv185

- Van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y

- Walseth, K., Aartun, I., & Engelsrud, G. (2017). Girls’ bodily activities in physical education: How current fitness and sport discourses influence girls’ identity construction. Sport, Education and Society, 22(4), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1050370

- Warburton, V. E., & Spray, C. M. (2017). Implicit theories of ability in physical education: Current issues and future directions. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0043

- Ward, G., & Quennerstedt, M. (2016). Transactions in primary physical education in the UK: A smorgasbord of looks-like-sport. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.923991

- Wilkinson, S., Littlefair, D., & Barlow-Meade, L. (2013). What is recognised as ability in physical education? A systematic appraisal of how ability and ability differences are socially constructed within mainstream secondary school physical education. European Physical Education Review, 19(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X13486049

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805