ABSTRACT

This study investigates teachers' perceptions of school democracy within a low-stakes accountability context. While previous studies have focused on teachers' perceptions of school climate and citizenship norms, we know less about factors associated with their perceptions of democracy in their schools. Through a multiple regression analysis of survey data, we investigated possible predictors of teachers' perceptions regarding their schools' democratic character within Norway's low-stakes accountability system. In this study, theories on professionalism and educational and democratic leadership serve as an overarching framework. Results suggest a positive relationship between teachers' experience of trust, support, and an inclusive relationship with their principal/leadership team and perceptions of democratic features in their school. Moreover, the higher the importance teachers place on teaching skills and values related to democracy, the more democratic they perceive their schools to be. Finally, findings indicate that education for democracy is embedded in collaboration structures at the school level.

Introduction and Purpose

How schools prepare students to become active citizens in different contexts is an area of study that has received increased attention in the literature in recent years (Mathé & Elstad, Citation2018; Schulz et al., Citation2018; Trujillo et al., Citation2021). The role of schools in promoting democracy is accentuated by sociopolitical events, especially due to the increasing political polarization in Western democracies. Earlier studies have emphasized tensions between promoting features of democratic schools that depend on upholding professional standards on the one hand, and increasing managerial demands, such as monitoring of performance data from central and district levels, on the other (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021). The significance of contextual conditions in the promotion of democracy and social justice within schools has been highlighted in the literature, specifically the notion that high-stakes, as opposed to low-stakes testing contexts, may create obstacles for promoting the democratic features of schools among school principals (Trujillo et al., Citation2021).

Norway, which represents a low-stakes testing context, is described as a social democratic welfare state (Esping-Andersen, Citation1989) – one that has traditionally embraced democratic values and ideals, such as justice, equity, and participation. A key principle in the social democratic welfare system is the equitable distribution of resources and services, particularly in the education sector. During the 1980s and early 1990s, neoliberal reforms gained ground internationally. Norway was no exception, and performance measurement and accountability-based practices were introduced at the beginning of the new millennium (Moller & Skedsmo, Citation2013). However, the introduction of these policies culminated in a clash between managerial notions of leadership and a focus on “what works,” on the one hand, and the social democratic ideology that encompasses notions of the equitable distribution of resources and democratic participation, on the other.

As a result of such policy changes, educational professionals found themselves in the position of having to negotiate conflicting demands and tensions in their work. In particular, they were positioned in a hierarchical structure in which they were required to report the results (learning outcomes in basic skills) to local educational authorities, guided by the aim of improving academic results (Skedsmo & Moller, Citation2016). Simultaneously, they were expected to ensure a healthy learning environment for all students within their schools while promoting civic and democratic participation. Therefore, the aim of the current article is to increase knowledge about how teachers perceive school democracy in practice in a low-stakes accountability context. This is achieved by conducting a multiple regression analysis based on survey data, with the aim of mapping possible predictors of teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their respective schools (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the research question guiding this study is as follows: Which factors are associated with how teachers perceive the state of democracy in their schools?

Previous studies on teachers’ relationships with their principals indicate that the perceived support and care received by teachers, along with their possible active participation in various decision-making processes, are important factors in a functioning democratic school (Apple & Beane, Citation1995; Hoog et al., Citation2007). Another strand of research has demonstrated the importance of communication and collaboration between school leaders and teachers in a school democracy (e.g., Apple & Beane, Citation1995; Zachrisson & Johansson, Citation2010). Other studies have focused on the perceptions of principals (Trujillo et al., Citation2021), teachers (Sampermans et al., Citation2021), and students (Mathé & Elstad, Citation2018) regarding education for democracy. However, we currently have limited knowledge about how teachers perceive school democracy in practice within a low-stakes accountability context. Thus, in the current study, we explore this issue by using Norway as an example of a low-stakes accountability context in which test-based accountability demands have been institutionalized over time (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021). Knowledge about this topic is important in understanding how a school democracy may further teachers’ democratic practices. In turn, we can further promote democratic practices within the school setting by building on these conceptualizations. We start by paying attention to some aspects of the Norwegian context.

The remainder of the article is organized into sections. First, we present our theoretical understanding of some key concepts in this study (i.e., educational leadership for democracy, professionalism, and accountability) before showing how previous research has influenced the development of the study. The following sections present the methodology and results of the analysis. Finally, we discuss the significance of our findings and their implications for educational practice and research.

Contextual Background

Research in the Scandinavian context has demonstrated school leaders’ prominent role in promoting the democratic spirit, highlighting their duty to internalize national goals and prioritize these in the educational agenda (Höög et al., Citation2007; Zachrisson & Johansson, Citation2010). However, when the new General Curriculum was introduced in 2017, it was accompanied by new demands for working with democratic processes, thus exacerbating the conflicting tensions in teachers’ work (Larsen et al., Citation2020). In Norway, school leaders and teachers are required to work on “Democracy and Citizenship” as a cross-curricular theme:

The teaching and training shall give the pupils knowledge and skills to face challenges in accordance with democratic principles. They shall understand dilemmas that arise when recognizing both the preponderance of the majority and the rights of the minority. They shall train their ability to think critically, learn to deal with conflicts of opinion and respect disagreement. (Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training, Citation2017)

Theoretical Framing of Key Concepts

Multiple definitions of education for democracy have been proposed in the literature (e.g., Apple & Beane, Citation1995; Dewey, Citation1916; Habermas, Citation2015; Mouffe, Citation2005; Woods, Citation2005). In addition, Dewey’s (Citation1916) emphasis on faith in experience, along with his argument that the best way to teach and learn democracy is to practice it, has inspired many contemporary works on democracy in education. For instance, Stray (Citation2010) understands education for democracy in a way that is both broad and anchored in a tripartite understanding involving three elements: education about democracy (intellectual knowledge), education for democracy (attitudes and values), and education through democratic participation. Furthermore, we argue that it is necessary to supply this perspective with an understanding of education as a public good in which the key aim is to achieve inclusion in a pluralistic community (Englund, Citation1994). Similarly, Anderson and Cohen (Citation2018) emphasized working for a common good with the aim of securing equal opportunities for all students. Following this broad understanding of education for democracy, our conceptual framework draws on theories of educational leadership and perspectives of professionalism and accountability.

First, we understand educational leadership as a relational concept in which leadership practice takes place in interactions between people in specific contexts. This implies that educational leadership is not necessarily synonymous with a particular position. We distinguish between educational leaders in formal roles and leadership as practice (Lingard et al., Citation2003). In local schools, educational leaders in formal roles include principals, assistant principals, and deputy heads. Moreover, we assume that teachers serve as key actors in democratic schools by taking on informal leadership roles, such as educational leadership, through practices that are dispersed across the organization (Lingard et al., p. 53), while also being included in decision-making processes (Woods, Citation2005). Earlier studies have suggested that teachers play a key role in educational leadership in schools (e.g., de Villiers & Pretorius, Citation2011; Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017). For the purpose of our research, we assume that teachers take on leadership responsibilities in addition to their teaching activities (Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017 p. 140). For example, an indication of leadership responsibility outside the classroom is reflected in collaboration with other teachers and with school leaders in formal leadership positions (cf. Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017).

Additionally, we draw from democratic leadership theory inspired by Woods’ (Citation2005) conceptualization. In democratic leadership, one of the main responsibilities of educational leaders is to promote democratic values in both the school and the community. This conceptualization is based on a developmental conception of democratic practice (Woods, Citation2005, p. 12) involving four rationalities, each with its distinct focus and priority: decisional, concerning the right to participate; discursive, concerning the possibilities for open debate; therapeutic, concerning the creation of positive feelings of involvement and social cohesion; and ethical, concerning aspirations to truth and distributions of internal authority (Woods, Citation2005, pp. 11–15). The four rationalities may relate to the definition of educational leadership proposed by James et al. (Citation2020, p. 632): “Educational leadership practice is a legitimate interaction in an educational institution intended to enhance engagement with the institutional primary task.” They further argued that a definition of educational leadership practice must specify the legitimacy of such practices, including, for example, the ethical/moral basis of agency.

In the Norwegian context, the “institutional primary task” includes three dimensions of education about, for, and through democracy (cf. Stray, Citation2013). This implies that both school leaders and teachers engage in the primary tasks of education, including the abovementioned three dimensions. We are also inspired by theories on professionalism, particularly Evetts’ (Citation2011) theory on occupational professionalism and Anderson and Cohen’s (Citation2018) conceptualization of democratic professionalism. Evetts (Citation2011) emphasized that what is termed “occupational professionalism” involves collegial authority (as opposed to the authority of results) and relationships based on trust. Meanwhile, Anderson and Cohen’s (Citation2018) conceptualization involves culturally responsive and democratic teaching while viewing the principal and the teachers as colleagues within a democratic school community. They further argued that democratic professionals display sensitivity to the problematic relationship between performance indicators and demographics and that being a democratic professional requires teachers to work with rather than on the students (Anderson & Cohen, Citation2018). It demands that teachers draw from students’ prior experiences and frames of reference to ensure that learning encounters are more relevant for them. This conceptualization is well aligned with the expectations outlined in the Norwegian National Curriculum.

Democratic professionalism encompasses notions of democratic leadership, especially the inclusion of teachers in decision-making processes. As educational professionals, school leaders and teachers are situated between managerial mechanisms of accountability operating within a hierarchy. This means being answerable to superiors regarding specific outcomes or results, on the one hand, and professional accountability – guided by internalized codes of ethics – on the other (Evetts, Citation2009). In addition, educational professionals face democratic mechanisms of accountability, which entail collective choice and public control over decisions, such as when they have to justify their decisions to parents (Ranson, Citation2003).

Previous Research Influencing the Development of the Present Study

Corresponding to our understanding of educational leadership as practice (Lingard et al., Citation2003), studies have demonstrated that teachers taking part in decision-making processes are important features of a democratic school (Apple & Beane, Citation1995; Höög et al., Citation2007; Moller, Citation2006; Woods, Citation2005). Moreover, empirical studies have proposed some key factors for making democratic schools possible. These factors, which are relevant for school leaders and teachers, include the free flow of ideas, irrespective of popularity; faith in the capacity for problem-solving, both individually and collectively; critical reflection and analysis concerning ideas, problems, and policies; concern for the welfare of others and the common good; concern for the dignity and rights of individuals; and the promotion of democracy not as an abstract ideal but as a set of values that must be lived (Apple & Beane, Citation1995). Enabling these key factors presupposes the fostering of democratic structures and processes as well as a democratic curriculum (Apple & Beane, Citation1995, p. 10). Apple and Beane (Citation1995) further proposed that promoting democracy is a collective project and that enabling democratic structures and processes occur through co-operation, not competition (see also Proitz, et al., Citation2019). This understanding underscores the importance of trust and collaboration in schools.

According to earlier studies, Norwegian school leaders have reported a relatively high level of teachers’ involvement in decision-making (e.g., Huang et al., Citation2017). We have built on these findings related to how teachers themselves perceive the possibilities of being included in school-wide decision-making through teacher – leader collaboration. We assume that such collaboration, which implies leadership support and inclusion in decision-making, is a possible factor associated with how teachers perceive the state of democracy in their schools.

Extensive research has been conducted on the connections among democracy, the role of professional communities, and teacher collaboration in schools (Clark & Wasley, Citation1999; Fielding, Citation1999; Vangrieken et al., Citation2015; Westheimer, Citation2008). In the following, Westheimer (Citation2008) elegantly communicated the idea of teacher collaboration and emphasized that democracy entails more than just collective decision-making:

[It is] a form of human community in which human flourishing is best realized and which is, therefore, essential to good life. Thick democracy agrees that democratic practices promote fair decision-making, but its value goes well beyond this. Thick democracy attaches significant value to such goods as participation, civic friendship, inclusiveness, and solidarity. (p. 767)

Recent empirical studies have contributed to understanding students’ knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, and activities, as well as to promoting the democratic features of schools (Arthur, Citation2011; Mathé, Citation2019; Schulz et al., Citation2018). These studies have demonstrated that teachers hold an important position in promoting such features, especially regarding values education and students’ moral development (Arthur, Citation2011). Of relevance is the recent International Civic and Citizenship Study (ICCS) from 2016 (Schulz et al., Citation2018), which, based on a large-scale survey, investigated the various ways in which young people are prepared for citizenship in different countries. In one study, over 6000 Norwegian 9th grade students were tested on their civic knowledge and were surveyed on their civic attitudes and activities (Huang et al., Citation2017). The findings revealed that, among the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Norwegian students ranked fifth in the civic knowledge test and demonstrated significant levels of trust in democratic institutions. Moreover, the ICCS study demonstrated that most school leaders and teachers (79% and 74%, respectively) perceived developing students’ capabilities of independent and critical thinking as the most important factor in schools’ citizenship education. These findings underscore the importance of teaching democracy in an educational setting, and, consequently, we know that the teaching dimension is central to a school democracy. In fact, this also includes how teachers work to support citizenship activities for students in school and beyond (Arthur, Citation2011; Babic, Citation2019; Chadjipadelis et al., Citation2020; Mathé & Elstad, Citation2018; Stray, Citation2010; Thomas, Citation2009). Therefore, we found it reasonable to believe that a connection exists between how teachers perceive the state of democracy in their schools and their ideas regarding teaching democracy.

In addition, parental support from home seems to be an important factor in enabling democratic and equitable features of schools (Hahn, Citation2015; Marschall, Citation2006; Miklikowska & Hurme, Citation2011). The same is true for home – school collaboration, especially when it comes to creating more equitable opportunities for students coming from disadvantaged backgrounds (Moles, Citation1993; Raffaele & Knoff, Citation1999). These strands of research have paid attention to students representing particular minorities (Hahn, Citation2015; Marschall, Citation2006). As these studies revolve around notions of democracy and equity, we expect that the opportunities provided by schools to assist students who do not receive sufficient support from home are associated with teachers’ perceptions of school democracy. In other words, if teachers experience that they are not able to compensate for a lack of parental support, this might influence their perceptions of their school’s democratic character.

Furthermore, earlier studies have emphasized tensions between promoting features of democratic schools that depend on professional standards on the one hand, and increasing managerial demands that connect with features of new public management (NPM), such as monitoring of performance data from central and district levels, on the other (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021; Larsen et al., Citation2020). The contextual conditions for promoting democracy and social justice within schools are also crucial (Trujillo et al., Citation2021). Specifically, high-stakes, as opposed to low-stakes testing contexts, may create obstacles for promoting the democratic features of schools among school principals (Trujillo et al., Citation2021). In Norway, which represents a low-stakes testing context, traditional social democratic ideals have been put under increased pressure from neoliberal reforms inspired by the global market (Volckmar, Citation2008). Moreover, Lieberkind (Citation2015) argued that changes in Scandinavian educational discourse – from a focus on democratization to that on students’ knowledge and skills – have exerted pressure on democratic education in schools due to the emergence of new paradigms of accountability. On the basis of such information, we assume that contextual conditions may be related to teachers’ perceptions of democracy in schools.

In summary, this review has revealed several factors that may play important roles in how teachers perceive the state of democracy in their schools. First, it has been shown that teachers play a possible role in educational leadership in schools through involvement in school-wide decision-making. Second, following previous research, it appears that leadership responsibility outside the classroom is reflected in collaboration with other teachers. Third, the teaching dimension is central to a school democracy, and this also includes how teachers work to support citizenship activities for students in school and beyond. Fourth, previous research has highlighted how the support received by students from home is related to democracy in schools. Accordingly, we found it reasonable to believe that all of these factors are related to teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools.

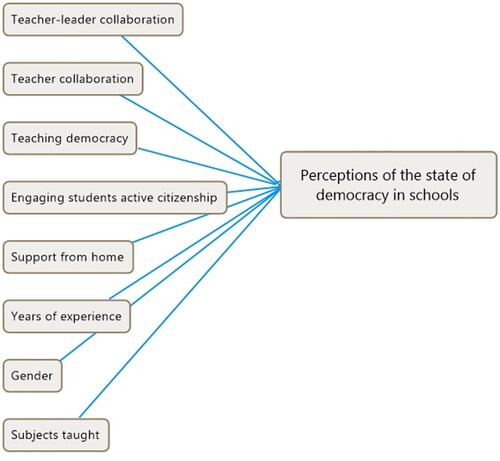

Additionally, we include background measures that are frequently used in empirical survey studies (cf. Burroughs et al., Citation2019), namely, gender, teachers’ years of experience, and the subjects they teach. Following the abovementioned perspectives and previous research, we outline the expected relationships between teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools and the potential associated factors in below. Later, we present the methods, results, and findings of this work.

Methods

This article reports on a study conducted in Eastern Norway among teachers in lower secondary schools. We designed a quantitative study to explore the strength of the relations between teachers’ perceptions of the democratic character of their schools (dependent variable) and each of the associated factors based on previous research (e.g., Huang et al., Citation2017; Sampermans et al., Citation2021; Trujillo et al., Citation2021). This kind of study allowed us to determine patterns and associations on an aggregated level rather than within or across individual responses.

Sample and Data Collection

We collected quantitative data through a paper-and-pencil questionnaire distributed in person at five lower secondary schools in Eastern Norway.Footnote1 Given that fulfilling schools’ democratic mandate might be challenging in diverse local communities and municipalities (Andersen & Ottesen, Citation2011), we purposively sampled lower secondary schools in urban areas of Eastern Norway to include heterogeneous schools, especially with respect to students from minority backgrounds. All the sampled schools had at least 350 students (M = 489).

Prior to recruiting participants, we contacted the principal at each school and asked for permission to visit in person and conduct a survey among the teaching personnel during a staff meeting. Interestingly, related to the purpose of this study, all principals responded that they would need to discuss with their teachers whether the latter could spend their staff meeting time participating in our study before making a final decision. Due to time constraints, one school declined to participate. Education for democracy is part of schools’ mandate in Norway; thus, we invited all teachers to participate regardless of the subjects they taught. The sample included a total of 206 teachers (63.6% women and 33% men, with 3.4% missing values). As no teachers declined participation, we received a 100% response rate from the teachers who were present at each school.

Research Ethics

This study complied with the ethical standards required by the National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (2016) and obtained approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Furthermore, we discussed the study’s aims with the participants and obtained informed consent from each of them. We also notified the teachers that they could choose not to answer questions or withdraw from the study at any time while completing the survey, as we would not be able to trace their anonymous data after this. Participants’ privacy and confidentiality were assured, as we collected no personal or identifiable information.

Measures

The variables were each based on two to five items developed by the researchers and colleagues (see the Appendix). We also included some background information questions to control for the likelihood of observed differences caused by participants’ gender, years of experience, or the subjects taught. Except for the background variables, all the measures included in this study were scored on a 5- or 7-point Likert scale with a middle neutral value. Therefore, the variables were assumed to be at an approximate interval level. The variables are as follows:

Teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schoolsFootnote2 (dependent variable): This variable comprises two items intended to measure teachers’ perceptions of how democratic their school is. Sample item: “How democratic is your school for students?”

Teacher – leader collaboration: This consists of four items intended to measure teachers’ perceptions of support from their school leaders. Sample item: “I feel that my voice is heard when the school makes school-wide decisions.”

Teacher collaboration: This comprises three items aiming to measure teachers’ perceptions of the conditions for teacher collaboration in their school. Sample item: “Teachers here observe one another and share feedback.”

Teaching democracy: This comprises five items and aims to measure teachers’ perceptions of the importance of teaching various skills and values related to democracy to their students. Sample item: “All teachers are responsible for nurturing democratic values in students.”

The importance of citizenship activities for students: This consists of five items adapted from the ICCS study (2016) and aims to measure teachers’ perceptions of the importance of students’ citizenship activities. Sample item: “Participating in political discussions.”

Students’ support from home: This comprises three items intended to measure teachers’ opinions about the opportunities provided by schools to help students who do not receive necessary support from home. Sample item: “When the students’ families are unable to provide enough support for their children academically, it is unreasonable to expect the school to meet those same needs.”

Teachers’ years of experience (background variable): This background variable consists of two items and measures each participant’s years of experience as teachers. Sample item: “How long have you been a teacher?” Response alternatives: 0–4 years (coded as 1), 5–9 years (coded as 2), 10–14 years (coded as 3), and 15 years or more (coded as 4).

Gender (background variable): We constructed the measure of gender to obtain information about teachers’ self-identified gender. This variable is dichotomous (1 = female, 2 = male).

Subjects taught (background variable): The teachers were asked to choose which kinds of subjects they taught. Response alternatives: Languages, Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Social Studies, Practical–Aesthetic subjects, and Elective subjects.

The Appendix presents the constructs and items that were originally distributed in Norwegian and then translated into English for this article. presents the bivariate correlations, descriptive statistics, and Cronbach’s alpha (α) for each construct. We deem the reliabilities satisfactory for the purpose of this study.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and bivariate correlations.

Data Analysis

We conducted multiple linear regression analysis to examine the relationships between the variables. Its estimation using ordinary least squares (OLS) is a widely used tool that allows for an estimation of the relation between a dependent variable and a set of independent or explanatory variables (Cohen et al., Citation2017). Initially, we examined descriptive item statistics using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The item scores were approximately normally distributed for all variables. Then, we conducted principal component analyses (PCA) for all measures. The items associated with each variable emerged as one component of the PCA (see the Appendix). Then, we combined the respective items to make up the variables used in the regression analysis.

We Found that the Items Related to the Dependent Variable Accounted for 80% of the Variance, Whereas the Items Concerning Citizenship Activities for Students, Support from Home, Teacher – Leader Collaboration, Teacher Collaboration, Teaching Democracy, and Years of Experience Accounted for Approximately 54%, 66%, 67%, 65%, 53%, and 85% of the Variance, Respectively.

Next, we tested the hypothesized model by performing a multiple linear regression analysis in SPSS. We based the assessment of the regression model on the adjusted R2, which was a modified fraction of the sample variance of the dependent variable explained by the regressors. The aim of the analysis was to either confirm or reject the strength and significance of the relationships between the independent and dependent variables.

Reliability, Validity, and Limitations of the Study

We used Cronbach’s α, which can capture the breadth of the construct, to assess the indicators’ measurement reliability for each scale (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). Cronbach’s α is influenced by the number of items in a test (Eisinga et al., Citation2013) and ranges from 0–1. Our measures were mostly satisfactory, with values ranging from .728–.841.

While this article is based on new quantitative data from lower secondary school teachers, there are some clear limitations concerning validity. First, we do not claim causality. Johnson and Christensen (Citation2016) established three conditions for making a claim of causation between two variables: (a) the variables must be related, (b) changes in the independent variable must occur before changes in the dependent variable, and (c) there must not be any plausible alternative explanation for the observed relationship between the variables. In our study, while the first condition (presence of a relationship) was met, this was not a sufficient requirement for a causation claim. The second requirement (the temporal order condition) could not be addressed directly, because the data were cross-sectional (i.e., collected at a single point in time). Moreover, we do not claim to have controlled for all alternative explanations. Thus, although the expected relationships were theory-generated, suggesting that the estimated regression coefficients may reveal causal relationships, the identified causal directions may be ambiguous.

The second restriction is that we made no claims to external validity or generalizability due to limitations in the sample (Johnson & Christensen, Citation2016). While the sample comprised over 200 teachers from five schools, we relied on non-probability sampling for this study. Furthermore, we did not suspect selectivity bias to be a clear threat to validity, because no teachers refused to participate in our investigation. A larger sample might improve the validity of the statistical conclusions (Cook & Campbell, Citation1979). However, readers may make naturalistic generalizations by comparing their groups’ demographics and other characteristics to those of the participants in our study (Johnson & Christensen, Citation2016) and decide upon the transferability of the results by comparing the context of the study to their own.

Finally, we acknowledge that self-reported data provide insights into some important aspects of school life – in this case, teachers’ perceptions, but not all. Moreover, we determined not to define important concepts, such as “democracy,” for the participating teachers. Consequently, their various conceptualizations of democracy and related concepts may have influenced their responses.

Results

presents the bivariate correlations (i.e., effect sizes) between the variables as well as the means, Cronbach’s α, and standard deviation for each construct. For readability, we note that for binary and categorical variables, mean values denote the percentage of responses.

Looking at the descriptive statistics in , it is worth pointing out the mean value of the dependent variable, teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools (4.88 on a 7-point scale). This implies that the teachers, on average, rated their school just above the neutral middle value in terms of how democratic they perceived it to be for both students and teachers. Of note in is the strong relation between teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their school and their perceptions of teacher – leader collaboration. We also noted significant correlations between teacher collaboration and their perceptions of the importance of teaching democracy, on the one hand, and the dependent variable, on the other hand. Contrary to our expectations, teachers’ perceptions of the importance of citizenship activities for students and their opinions about the opportunities provided by schools to support students who received insufficient support from home were not significantly related to the dependent variable in this stage of the analysis. Neither were the background variables. Thus, the background variables that were not significantly correlated with the dependent variable were excluded in the next step of the analysis to allow for a simpler regression model.

Unlike the correlations presented in , the regression analysis presented in shows each variable’s unique contribution to explaining the dependent variable. Furthermore, presents the unstandardized (b) and standardized (ß) coefficients of the OLS regression with teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools as a dependent variable, along with the standard error of the regression (SE (B)) and confidence intervals (CI, set at 95%). Overall, the regression analysis mirrored the pattern of the correlation analysis. In particular, the results showed that teacher – leader collaboration was associated with teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools at a significance level of <.001. Additionally, teaching democracy and teacher collaboration were significantly associated with teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools, with significance levels of <.01 and <.05, respectively. Contrary to our expectations based on previous research, teachers’ perceptions of the importance of citizenship activities for students and of opportunities provided by schools to support students who do not receive necessary support from home were not significantly associated with their perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools.

Table 2. Coefficients of regression with teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy as the dependent variable (n=206).

Next, we tested the regression model but found no indication of multicollinearity being a problem in the analysis (variance inflation factor (VIF) values under 2). Below, we discuss this study’s findings in relation to previous research and our understanding of key concepts before we suggest implications for educational practice and present the conclusion of this paper.

Discussion

This study offers new insights into what characterizes the practices of democratic schools in a low-stakes accountability context. First, the analysis revealed a relationship between teachers’ perceptions of how democratic they perceive their schools to be for both students and teachers and teacher – leader collaboration, including teacher involvement in decision-making processes. The relatively strong association between these two variables indicates that teachers who experience trust, support, and an inclusive relationship with school leadership tend to perceive their school as democratic. This finding resonates with previous research in the Norwegian context, which stated that enacting the primary task of education occurs through collaboration within professional communities (Proitz et al., Citation2019), through which school professionals are granted much leeway in translating policy and often draw from their own experiences (cf. Helstad et al., Citation2019).

Additionally, while we did not include background variables in the regression analysis due to their weak and non-significant correlations with the dependent variable, we would like to highlight the importance of the fact that teachers’ gender, years of experience, and subjects taught were not significantly associated with their perceptions of school democracy in this study. This finding may thus indicate that the characteristics of individual teachers do not matter as much as school-wide processes and conditions (e.g., collaborative environments and professional communities).

Closely linked to professional communities are notions of professionalism in which educational leadership is understood as a relational practice (cf. Anderson & Cohen, Citation2018). Thus, the current study adds to the body of literature in education for democracy, as it demonstrates a strong association between teacher – leader collaboration and teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools. This finding also lends support to earlier claims that, despite the influences of managerial elements, such as NPM and performance-based accountability in the Norwegian school system (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2021; Gunnulfsen, Citation2017; Skedsmo & Moller, Citation2016), collaborations through participation in professional communities still seem to be important among teachers based on findings in our sample. This is illustrated, for example, by the high mean values for the variables teacher – leader collaboration and teaching democracy (4.54 and 4.55 on a 5-point scale, respectively). Although there has been an increased emphasis on performance outputs in low-stakes accountability systems (cf. Lieberkind, Citation2015), teachers still perceive professional communities and collaboration as playing key roles in promoting the democratic mission in Norwegian schools. This cooperation suggests the presence of relationships based on trust, which is an aspect of occupational professionalism (Evetts, Citation2011). Furthermore, the association between teacher – leader collaboration and teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools suggests the presence of professional communities, which play a key part in fostering democratic professionalism (Anderson & Cohen, Citation2018).

A second finding is that the higher the importance teachers place on teaching skills and values related to democracy, the more democratic they perceive their schools to be. Consequently, those who perceive teaching democracy to students as less important also perceive their schools as less democratic. This finding suggests that teachers who include skills, values, and knowledge related to democracy in their teaching are likely to see their schools as having democratic characteristics or are more aware of democratic features in their schools. In particular, the very high mean value of the variable teaching democracy (4.55 on a 5-point scale) indicates that the participants in our study strongly believe in the importance of teaching skills and values related to democracy to their students. In turn, this belief indicates that teachers support a broader school mandate of education for democracy, including the application of a participatory approach and the importance of nurturing democratic values (cf. Anderson & Cohen, Citation2018). However, we do not know how teachers’ underlying conceptualizations of democracy influenced their responses or to what extent notions of inclusion and equity factored into these.

Third, the value of a collaborative environment for teachers has been highlighted, both theoretically and empirically, in previous research. Meanwhile, our study highlights the importance of democratic rationalities at play in schools (Woods, Citation2005). Thus, our findings reflect the presence of positive feelings of involvement, a conceptualization of educational leadership based on a developmental conception of democratic practice (e.g., by participating in practices that are dispersed across the organization), and an inclusive decision-making process as means of striving toward democratic ideals. Therefore, it is not surprising that teachers’ perceptions of the conditions for collaboration with colleagues seem to be associated with their perceptions of their school’s democratic character, especially considering the tradition of cooperation in Norwegian schools (e.g., Proitz et al., Citation2019). Although further research is needed on the topic, our study suggests that the presence of inclusive decision-making, collaboration, and professional communities are key characteristics of democratic practices within a low-stakes system of accountability.

Meanwhile, contrary to our assumptions, the regression analysis results showed that teachers’ perceptions of the importance of citizenship activities for students and of their school’s opportunities to compensate for the lack of parental support from home were not significantly associated with teachers’ perceptions of the democratic character of their schools in this study. These findings are somewhat surprising, especially as the items making up citizenship activities for students are conceptually and empirically (r = .405) related to teaching democracy. This may be explained in two ways: (1) the variable citizenship activities for students mediates teaching democracy, and (2) the importance of citizenship activities for students partly points toward school-external activities and does not, in fact, highlight the role of schools.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to increase knowledge about how teachers perceive school democracy in practice in a low-stakes accountability context by investigating the potential factors associated with their perceptions of the state of democracy in their respective schools. Our main findings revealed that teacher – leader collaboration, teaching democracy, and teacher collaboration were significantly associated with teachers’ perceptions of the state of democracy in their schools, while their perceptions of the importance of citizenship activities for students and the opportunities provided by schools to support students who do not receive necessary support from home were not.

As our study has demonstrated the importance of teaching democracy and teacher – leader and teacher collaborations as key factors related to how teachers perceive the state of democracy in their schools, we present the following implications for school leadership and practitioners. First, practitioners should be aware of the importance of school organization and structure in ensuring democratic processes. There is reason to argue that support from school leaders in formal leadership positions and inclusion in decision-making processes ought to be embedded at every level possible, despite the presence of structural restraints. In particular, there should be room for participation, inclusiveness, and teachers’ collaboration in a so-called “thick democracy” (Westheimer, Citation2008; Strike, Citation1999), such as through working in teams or engaging in collaborative leadership practices (cf. de Villiers & Pretorius, 2011). Including teachers in collaborative processes while also involving the leadership team may also help promote democratic structures and processes, as democracy is a collective project (cf. Apple & Beane, Citation1995).

Second, we suggest that, given the current responsibility of teachers to teach democracy, they should not only be prepared to do so but also to be included in collaborative reflections about what constitutes democratic features in their schools. In doing so, they can become part of a professional community that aims to support an inclusive and participatory school environment for both students and teachers. As we demonstrate the importance of collaboration in relation to teachers’ perceptions of school democracy, our study supports the narrative of a common public school with robust professional communities (Moller, CitationIn Press).

Despite its limitations, we argue that the current study can serve as a point of departure for future research. First, additional factors could be added to the model to increase its explanatory potential. For example, future research could include supplementary variables regarding teachers’ perceptions about school characteristics. Second, more studies are needed to improve the validity of our results. Although the reliability scores in our study are satisfactory, there is potential for developing the operationalization of the constructs examined. Third, although this study benefited from using data from over 200 teachers in five different schools, we relied on a non-probability sample. Thus, future studies could include larger and even more diverse samples to improve external validity.

With that said, our study contributes to building a foundation of knowledge about teachers’ perceptions of democracy in schools, which is understood in a wide sense. In this way, we demonstrate that education for democracy not only occurs in the classroom but is embedded in the structures of decision-making and collaboration at the school level. In addition, our study contributes empirical evidence of school-wide processes in promoting education for democracy in a low-stakes accountability context.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank Associate Professor Tina Trujillo at University of California, Berkeley, and Professor Emerita Jorunn Møller who led the work of developing the survey instrument used in this study. We also would like to extend our gratitude to the research assistants who assisted in the survey development affiliated with the research group P.O.M.E (Policy, Organization, Measurement, Evaluation) led by Dr. Trujillo at UC Berkeley: Jeremy Martin and María Eugenia Rojas. The development of the survey was funded by the Peder Saether Center of Advanced Studies.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Comprising years 8, 9, and 10 of the education system in Norway (ages 13–16).

2 As we were interested in teachers’ perceptions, we did not include a definition of the concept of democracy in the survey instrument. Therefore, we must assume that teachers’ responses relied on their own conceptualizations of democracy—be they implicit or explicit.

References

- Andersen, F. C., & Ottesen, E. (2011). School leadership and ethnic diversity: Approaching the challenge. Intercultural Education, 22(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2011.617422

- Anderson, G., & Cohen, M. I. (2018). The new democratic professional in education. Teachers’ College Press.

- Apple, M. W., & Beane, J. A. (1995). Democratic schools. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

- Arthur, J. (2011). Personal character and tomorrow’s citizens: Student expectations of their teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.07.001

- Babic, M. (2019). Schooling, democracy and the quest for wisdom: Partnerships and the moral dimensions of teaching. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(5), 611–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1675390

- Burroughs, N., Gardner, J., Lee, Y., Guo, S., Touitou, I., Jansen, K., & Schmidt, W. (2019). Teacher variables, and modeling the relationships between teacher characteristics, teacher behaviors, and student outcomes. In N. Burroughs, J. Gardner, Y. Lee, S. Guo, I. Touitou, K. Jansen, & W. Schmidt (Eds.), Teaching for excellence and equity: Analyzing teacher characteristics, behaviors and student outcomes with TIMSS (pp. 19–28). Springer International Publishing.

- Camphuijsen, M. K., Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2021). Test-based accountability in the Norwegian context: Exploring drivers, expectations and strategies. Journal of Education Policy, 36(5), 624–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1739337

- Chadji̇padeli̇s, T., Soti̇roglou, M., & Papaoi̇konomou, A. (2020). Teaching democracy: Tools and methods in the secondary education. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 380–388. https://doi.org/10.24331/ijere.768954

- Clark, R. W., & Wasley, P. A. (1999). Renewing schools and smarter kids: Promises for democracy. Phi Delta Kappan; Bloomington, 80(8), 590–596.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). The design and conduct of true experiments and quasi-experiments in field settings. In Reproduced in part in research in organizations: Issues and controversies. Goodyear Publishing Company.

- de Villiers, E., & Pretorius, S. G. (fanie). (2011). Democracy in schools: Are educators ready for teacher leadership? South African Journal of Education, 31(4), 574–589. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n4a453

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. te, & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach, or spearman-brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3

- Englund, T. (1994). Education as a citizenship right-a concept in transition: Sweden related to other Western democracies and political philosophy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 26(4), 383–399.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1989). The three worlds of welfare capitalism [EPUB]. Polity Press.

- Evetts, J. (2009). New professionalism and new public management: Changes, continuities and consequences. Comparative Sociology, 8(2), 247–266.

- Evetts, J. (2011). A new professionalism? Challenges and opportunities. Current Sociology. La Sociologie Contemporaine, 59(4), 406–422.

- Fielding, M. (1999). Radical collegiality: Affirming teaching as an inclusive professional practice. The Australian Educational Researcher, 26(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219692

- Gale, T., & Densmore, K. (2003). Democratic educational leadership in contemporary times. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 6(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120304819

- Gunnulfsen, A. E. (2017). School leaders’ and teachers’ work with national test results: Lost in translation? Journal of Educational Change, 18(4), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9307-y

- Habermas, J. (2015). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hahn, C. L. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of education for democratic citizenship in schools with transnational youth: A comparative study in the UK and Denmark. Research in Comparative and International Education, 10(1), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499914567821

- Helstad, K., Bekkelien, M., & Solstad, A. (2019). Skoleutvikling på ungdomstrinnet -profesjonalisering innenfra og utenfra. In K. Helstad, & S. Mausethagen (Eds.), Nye lærer- og lederroller i skolen (pp. 165–184). Universitetsforlaget.

- Hoog, J., Johansson, O., & Olofsson, A. (2007). Successful principalship-the Swedish case. In Successful principal leadership in times of change (pp. 87–102). Springer.

- Huang, L., Ødegård, G., Hegna, K., Svagård, V., Helland, T., & Seland, I. (2017). Unge medborgere. Demokratiforståelse, kunnskap og engasjement blant 9.-klassinger i Norge. The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2016. Oslo Metropolitan University - OsloMet.

- James, C., Connolly, M., & Hawkins, M. (2020). Reconceptualising and redefining educational leadership practice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(5), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1591520

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. B. (2016). Educational research (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Larsen, E., Møller, J., & Jensen, R. (2020). Constructions of professionalism and the democratic mandate in education A discourse analysis of Norwegian public policy documents. Journal of Education Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1774807

- Lieberkind, J. (2015). Democratic experience and the democratic challenge: A historical and comparative citizenship education study of Scandinavian schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(6), 710–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.971862

- Lingard, B., Hayes, D., & Mills, M. (2003). Leading learning: Making hope practical in schools. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Marschall, M. (2006). Parent involvement and educational outcomes for Latino students. Review of Policy Research, 23(5), 1053–1076. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2006.00249.x

- Mathé, N. E. H. (2019). Democracy and Politics in Upper Secondary Social Studies: Students’ Perceptions of Democracy, Politics, and Citizenship Preparation (doctoral dissertation), University of Oslo.

- Mathé, N. E. H., & Elstad, E. (2018). Students’ perceptions of citizenship preparation in social studies: The role of instruction and students’ interests. JSSE-Journal of Social Science Education, 17(3), 75–87.

- Miklikowska, M., & Hurme, H. (2011). Democracy begins at home: Democratic parenting and adolescents’ support for democratic values. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 8(5), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2011.576856

- Moles, O. C. (1993). Collaboration between schools and disadvantaged parents: Obstacles and openings. Families and Schools in a Pluralistic Society, 168, 21–49.

- Møller, J. (2006). Democratic schooling in Norway: Implications for leadership in practice. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500498779

- Møller, J. (2009). School leadership in an age of accountability: Tensions between managerial and professional accountability. Journal of Educational Change, 10(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9078-6

- Møller, J. (In Press). Images of Norwegian educational leadership - Historical and current distinctions. In Normand, R., Moos, L., Min, L. & Tulowitski, P. (Eds.), The cultural and social foundations of educational leadership. An international comparison. Springer.

- Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2013). Modernising education: New public management reform in the Norwegian education system. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(4), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2013.822353

- Mouffe, C. (2005). The Return of the Political. Verso.

- Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. (2017). Overordnet del – verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen [General part of the Curriculum]. Retrieved January 7, 2021, https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=nob

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Prøitz, T. S., Rye, E., & Aasen, P. (2019). Nasjonal styring og lokal praksis–skoleledere og lærere som endringsagenter [national governance and local practice–school leaders and teachers as change agents]. In R. Jensen, B. Karseth, & E. Ottesen (Eds.), Styring og ledelse i grunnopplæringen (pp. 21–37). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Raffaele, L. M., & Knoff, H. M. (1999). Improving home-school collaboration with disadvantaged families: Organizational principles, perspectives, and approaches. School Psychology Review, 28(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1999.12085977

- Ranson, S. (2003). Public accountability in the age of neo-liberal governance. Journal of Education Policy, 18(5), 459–480.

- Sampermans, D., Reichert, F., & Claes, E. (2021). Teachers’ concepts of good citizenship and associations with their teaching styles. Cambridge Journal of Education, 1–18.

- Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., & Friedman, T. (2018). Becoming citizens in a changing world: IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2016 International Report. Springer.

- Skedsmo, G., & Møller, J. (2016). Governing by new performance expectations in Norwegian schools. In New public management and the reform of education (pp. 71–83). Routledge.

- Stray, J. H. (2010). Demokratisk medborgerskap i norsk skole? En kritisk analyse [Democratic citizenship in Norway? A critical analysis] (Doctoral dissertation). https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/30460

- Stray, J. H. (2013). Democratic citizenship in the Norwegian curriculum. In E. Bjørnestad & J. H. Stray (Eds.), New voices in Norwegian educational research (pp. 165–178). SensePublishers.

- Strike, K. A. (1999). Can schools be communities? The tension between shared values and inclusion. Educational Administration Quarterly: Eaq, 35(1), 46–70.

- Thomas, N. L. (2009). Teaching for a strong, deliberative democracy. Learning and Teaching, 2(3), 74–97. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2009.020305

- Trujillo, T., Møller, J., Jensen, R., Kissell, R.-E., & Larsen, E. (2021). Images of educational leadership: How principals make sense of democracy and social justice in two distinct policy contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20981148

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.04.002

- Volckmar, N. (2008). Knowledge and Solidarity: The Norwegian Social Democratic School Project in a Period of Change, 1945–2000. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(1), 1–15.

- Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316653478

- Westheimer, J. (2008). Learning among colleagues: Teacher community and the shared enterprise of education. In M. Cochran-Smith & S. Feiman-Nemser (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 756–782). Routledge.

- Woods, P. (2005). Democratic leadership in education. Paul Chapman Educational Publishing.

- Zachrisson, E., & Johansson, O. (2010). Educational leadership for democracy and social justice. In S. Huber (Ed.), School leadership - International perspectives (pp. 39–56). Springer Netherlands.