ABSTRACT

Students’ school success and general well-being can improve when they believe in their academic abilities and are aware of the purpose of their studies. This paper explores the development of Icelandic students’ academic self-concept and sense of purpose in their learning. The focus is directed at the period from the end of compulsory school through the upper secondary level, with an emphasis on students’ track and school-type. Using survey and registered data spanning four years, models of mixed ANCOVA indicate that change in both constructs was the result of the interaction between time and school-type and track. Academic self-concept and sense of purpose decreased among academic students in all-academic schools but increased among vocational students. This suggests that students comparing themselves to their fellow students has a stronger effect on how their attitudes toward themselves and their education develop than the different status of tracks and school-types.

Helping students develop a stronger academic self-concept and positive school attitude is important for both their motivation (Lent et al., Citation1984; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, Citation2003) and general well-being (Craven & Marsh, Citation2008). Tracking of students has been shown to be related to their academic self-concept and their attitudes towards school (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Dockx et al., Citation2019; Van Houtte, Citation2005). Tracking refers to how students are grouped in different schools, educational programmes, or classes and is implemented differently and at different ages across education systems. Educational tracks have a different status in society and they differ with regard to the average academic ability of students (Dockx et al., Citation2019; Trautwein et al., Citation2006).

The frame of reference with which students develop their school attitudes and their academic self-concept can be grounded in both the common values that society holds towards different tracks and the academic ability of their school peers. The differentiation-polarization theory addresses the polarization of school attitudes and behaviours when students are differentiated into tracks of dissimilar status. According to the theory, students in higher tracks should have more positive attitudes towards school than lower track students (Hammersley, Citation1985; Hargreaves, Citation1967; Lacey, Citation1970).Footnote1 On a more individual level, two empirically supported theories focus on students’ self-concept and how students compare their academic ability to the performance of other students or the societal status of their track and school. The first one, called the basking in reflected glory effect (BIRGE) describes how a member of a certain group internalizes the value that society ascribes to that group (Cialdini et al., Citation1976; Dockx et al., Citation2019). The second one is known as the big-fish-little-pond-effect (BFLPE) and refers to how accomplishments are evaluated in relation to frames of reference where students focus on their immediate environment (Marsh, Citation1987; Marsh et al., Citation2008). According to BIRGE, students in higher tracks should have a greater self-concept compared to lower track students while higher tracks should have the opposite effect on students’ self-concept according to BFLPE.

The purpose of the current study is two-fold: (1) to assess if students’ attitudes towards themselves and their school are related to their educational track and type of upper secondary school and (2) if and how it changes over time. These questions will be explored using quality longitudinal data from Iceland, focusing on two dependent variables: academic self-concept and students’ sense of purpose in their learning, both measured at two time points. Students’ sense of purpose is used here as a measure of students’ attitudes towards school. By exploring academic self-concept and sense of purpose, which have been shown to promote students’ engagement and learning (Linnenbrink & Pintrich, Citation2003; Westbroek et al., Citation2010), our approach will contribute to a better understanding of the role tracking mechanisms play in the formation of students’ attitudes to themselves and their studies. The Icelandic system is characterized by late tracking, where students follow the same educational trajectories up until the age of 16, which is scarce in the research literature applying either the basking in reflected glory effect or the big-fish-little-pond effect. Thus, our research has the added value of further understanding these mechanisms among older students whos’ self-concept and attitudes are more developed compared to participants in studies from early tracking systems. Moreover, this study could possibly fill a gap in the literature for the fact that most research employing the differentiation-polarization theory use qualitative data, with a few exceptions though (see Berends, Citation1995; Van Houtte, Citation2006; Van Houtte & Stevens, Citation2009 for examples of quantitative approaches).

Academic Self-Concept and Frame of Reference Effects

Academic self-concept is one of the several facets of general self-concept, which is the overarching idea people have of themselves, and how they believe they are perceived by others (Shavelson et al., Citation1976). It is one of the most widely used representation of positive self-beliefs, a central construct in educational psychology and in theoretical models of motivation (Marsh et al., Citation2019). Students who strongly believe in their educational capability achieve higher grades and persist longer in their studies than students with low academic self-concept (Lent et al., Citation1984; Lerang et al., Citation2018; Richardson et al., Citation2012; Robbins et al., Citation2004; M. Schneider & Preckel, Citation2017).

Frames of reference play an important role in the development of the academic strand of self-concept (Bong & Skaalvik, Citation2003; Marsh, Citation1987). Individuals are influenced by the attitudes of others, they judge and evaluate themselves by comparing themselves to certain individuals, groups or social categories, and use their own behaviours as a basis for making inferences about their self-descriptions or competencies (LaRossa & Reitzes, Citation2009). As noted above, the basking in reflected glory effect describes the across-group comparison where students internalize the value society ascribes to the group they belong to (assimilation effect). Being a member of a group that is positively valued in society is likely to create feelings of pride among students (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Cialdini et al., Citation1976; Dockx et al., Citation2019; Marsh et al., Citation2000). In contrast, the big-fish-little-pond effect focuses on the within-group comparison where students compare their educational achievement with that of their classmates (contrast effect) rather than forming an impression of their abilities in comparison with the views held by society. Accomplishments are evaluated in relation to frames of reference where students’ academic self-concept depends both on their own achievements and other students in the class or school. Thus, the big-fish-little-pond effect occurs when strong students in high-ability schools compare themselves to their equally strong or stronger fellow students, causing them to feel less confident than if they would compare themselves to classmates in a low-ability school. Being a member of homogenous high-track class can thus have a negative impact on students’ academic self-concept (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Lavrijsen & Nicaise, Citation2017; Marsh, Citation1987; Trautwein et al., Citation2006).

The big-fish-little-pond effect has been hypothesized to be the net effect of the two counter-balancing processes that may occur concurrently: the positive assimilation effect of being a student in a high-status class or school and the negative contrast effect of comparing oneself with academically strong(er) schoolmates. Most previous studies have concluded that the negative contrast effects are stronger than the positive assimilation effects (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Marsh et al., Citation2000; Preckel & Brüll, Citation2010; Trautwein et al., Citation2006), with some exceptions (i.e., Wolff et al., Citation2021). In a longitudinal survey, Liu et al. (Citation2005) found that low-track students had a more negative self-concept than high-track students immediately after being tracked but the roles had reversed three years later. This suggests that there is an initial short-term assimilation effect due to across-group comparison at the beginning of secondary school, which is then overpowered by the negative contrast results of within-group comparison.

Sense of Purpose and the Polarization of Students’ School Attitudes

For students to be motivated and to value their studies they need to be provided with opportunities to see the relevance of their course of study. It is beneficial for them to see how their tasks can contribute to achieving particular objectives because an understanding of goals encourages them to engage more deeply in academic activities (Westbroek et al., Citation2010; Xerri et al., Citation2018). Students’ sense of purpose can be found in the answer to the question, “why am I studying this?” (Kember et al., Citation2008) and those who are able to sense the relevance of their schooling tend to persist in their studies and adjust better academically (Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, Citation1994). Moreover, they tend to get higher grades, are less likely to fail courses and have fewer school absences (Stoker et al., Citation2017). Sense of purpose is comparable to the term utility value which is determined by the usefulness of a task for future goals in Expectancy value theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2000) and has also been referred to as a future relevance (Rosenbaum et al., Citation1998) and importance of school for the future (Easton et al., Citation2008).

The differentiation-polarization theory addresses the polarization into students’ negative and positive school attitudes and behaviours when they are differentiated into tracks of dissimilar status. According to the theory, low-track students develop negative attitudes while high-track students’ attitudes towards school and education are more positive (Trautwein et al., Citation2006). The original support for this theory is mainly sought in the ethnographic case studies of Hargreaves (Citation1967) and Lacey (Citation1970), who showed that students in the top tracks were more committed to school values than students in lower streams (Abraham, Citation1989; Ball, Citation1981). Given the high societal status of academic education, vocational students have been found to be less engaged in their studies (Van Houtte, Citation2006; Van Houtte & Stevens, Citation2009) and to be more likely to develop negative attitudes of themselves and their school than students following academic courses (Belfi et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, students in lower tracks have also been found to experience a lower sense of purpose, because they see the schooling as less beneficial for their future. They do not see their school involvement as having a future payoff to the same extent that higher track students do (Lavrijsen & Nicaise, Citation2017). These negative attitudes can lead to disengagement from schoolwork, possibly resulting in them dropping out of upper secondary school without diplomas (Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, Citation1994; Lent et al., Citation1984; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, Citation2003). The reasoning behind this polarization in attitudes is that lower track students may suffer from status loss and feel like they failed academically while higher track students are likelier to experience school as a positive environment in light of the status of their track (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Van Houtte, Citation2005, Citation2006).

The Icelandic Context and the Hierarchy of Educational Tracks

The educational system in Iceland is characterized by heterogeneous classes in an otherwise homogeneous compulsory school system with integrated non-ability grouping. There is a general agreement on the basic requirement that education remains free of charge and the fundamental idea of the system is to provide equal educational opportunities to all with no tracking at the primary and lower secondary level (Blondal et al., Citation2011). Children in Iceland start school at the age of six and progress automatically from one year to the next throughout 10 years of compulsory education. The system is relatively standardized and could largely be described as egalitarian in that it is mainly public. Students follow the same trajectory and have the statutory right to upper secondary schooling which is voluntary and funded by the state. These attributes have been typical to other Nordic educational systems working towards equity, participation, and welfare with their publicly funded comprehensive primary and lower secondary school system (Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Imsen et al., Citation2016; Telhaug et al., Citation2006) (see more detailed discussion on the Nordic education system in the appendix).

After the completion of the 10th grade, around 95% of students continue their studies at the upper secondary level (Statistics Iceland, Citation2020). The upper secondary schools in Iceland fall into two main categories: Traditional grammar schools offering only matriculation examination programmes (all-academic schools); and comprehensive schools that offer both vocational programmes and academic programmes with a firm distinction between tracks (multilateral schools) (Ministry of Education Science and Culture, Citation2012).

In Iceland, as in the other Nordic countries, students choose a course of study when they start upper secondary education (Antikainen, Citation2006; Carlgren et al., Citation2006), referred to here as late tracking. In early tracking systems, students are assigned into different tracks, often before starting lower secondary school, usually based on their academic achievement (Trautwein et al., Citation2006). Tracking has been recommended to take place later rather than earlier since late tracking has been shown to reduce the impact of socio-economic factors, such as family background, and bring more equality and opportunities to lower class students (Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Betts, Citation2011; Schütz et al., Citation2008), while low upward social mobility in education has been linked to early tracking (Demanet et al., Citation2018; Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006; Nairz-Wirth et al., Citation2017). When Icelandic students transition from lower to upper secondary level, they usually join student groups with a more homogenous composition than before, in terms of their academic abilities (Eiríksdóttir et al., Citation2018). Strong emphasis is placed on academic education and parents generally want their children to follow the academic track, while vocational education (VET) is seen as a poorer option regardless of students’ strengths and interests (Blondal et al., Citation2011; Eiríksdóttir et al., Citation2018). In Iceland in 2016, 32% of students were enrolled in VET programmes compared to the OECD average of 44% (OECD, Citation2020) and only 16% of newly enrolled students at the upper secondary level chose vocational programmes (Statistics Iceland, Citation2018).

The Present Study

Most studies focusing on the basking in reflected glory effect, the big-fish-little-pond effect, and the differentiation-polarization theory are conducted in educational systems characterized by early tracking and ability grouping. Additionally, studies on the differentiation-polarization theory mainly build on qualitative data. This paper, however, presents a quantitative study conducted among students in Iceland, where the emphasis is placed on an integrated non-ability grouping system and late tracking. Due to the known interrelation between academic self-concept and academic achievement (Wu et al., Citation2021) and how the latter varies between students of different educational tracks (Blondal et al., Citation2011), academic achievement is controlled in the analyses. To examine how the basking in reflected glory effect and the big-fish-little-pond effect may apply in a late-tracking educational system, we ask the following research questions:

Is there a difference in students’ academic self-concept at the end of compulsory school (age 15) depending on their educational track at upper secondary level?

Is there a difference of over-time change in academic self-concept from age 15 to 19 between students who follow different educational tracks, independent of their academic achievement?

And to examine how the differentiation-polarization theory may apply, we ask:

Is there a difference in students’ sense of purpose at the end of compulsory school (age 15) depending on their educational track at upper secondary level?

Is there a difference of over-time change in sense of purpose from age 15 to 19 between students who follow different educational tracks, independent of their academic achievement?

Method

Procedure and Participants

This research is part of an ongoing longitudinal study: The International Study of City Youth (ISCY, see Blondal et al., Citation2019). We build on both survey and registered data. The study population included all students in the Reykjavík area of Iceland who were born in 1999 and who attended upper secondary school four school years later. The baseline sample was the population of all students aged 15 (the 1999 cohort) in the capital area during the autumn of 2014 (N = 2408). These students were attending their last year of compulsory education. There are 44 public schools in the capital area. Permission for the study was granted by the Icelandic Data Protection Commission (notification number S7011) and the educational authorities in all six municipalities in the capital area. Participants in the study answered an online questionnaire during school hours with the help of trained data-collectors. A total of 1956 students (52.5% females), or 81.2% of the cohort, participated at baseline.

The follow-up study was conducted in 2018, when participants were 19 years old. Answers to the online survey were collected at the upper secondary schools. At the time of the follow-up, 1662 of the baseline participants (N = 1956), were enrolled in upper secondary school in Iceland and therefore represented the study population. Out of the 1662, a total of 1047 participated again in 2018, yielding a response rate of 63.0% (58.5% females). This group of participants will be used in the following analysis.

Measures

Academic Self-Concept and Sense of Purpose

The scales used to measure academic self-concept and students’ sense of purpose were based on a framework created by ISCY researchers, modelling items on existing surveys and scales, such as the Big Five, and My Voice, My School (Lamb et al., Citation2015; Palardy & Rumberger, Citation2019; see also Zeiser et al., Citation2018 for sense of purpose). Principal component analysis on a 46-item list from the baseline data produced 12 components, including one for academic self-concept (component loadings ranging from .70 to .84) and another for sense of purpose (component loadings ranging from .74 to .88). These findings highly correspond with the analysis conducted on data from the same questionnaire from nine cities by Lamb et al. (Citation2015), suggesting a strong construct validity. The scale for academic self-concept consisted of four items: I am confident of doing well in school; right now I see myself as being pretty successful as a student; I can think of many ways to reach my current goals; and I can think of many ways around any problem that I am facing now. Students’ sense of purpose was also measured using four items which had to do with the meaning of school and their studies, viewed in the long term: Working hard in school matters for success in the workforce; what we learn in school matters for success in the future; school teaches me valuable skills; and my classes give me useful preparation for what I plan to do in life. Both constructs were measured when students were 15 and again when they were 19 years old. Response categories ranged between 1 (strongly disagree) and 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for academic self-concept was .88 at age 15 and .79 at age 19, and .84 and .83 respectively for sense of purpose, confirming reliability of the scales. The mean scores were used as measures of academic self-concept and sense of purpose for participants who answered at least three out of the four items for each scale. Higher scores indicate greater academic self-concept and a clearer sense of purpose.

Student Group: Type of School and Educational Track

Statistics Iceland provided access to registered data on students’ educational trajectories at upper secondary school (aged between 16 and 19). This information was used to group students according to their type of school and educational track. Since there are no upper secondary schools in Iceland offering only VET programmes, students fell in one of the following three groups: (1) Academic track at an all-academic school; (2) Academic track at a multilateral school; (3) Vocational track at a multilateral school. The criteria for each group were that participants had to be enrolled in the abovementioned type of school and educational track for majority of their upper secondary schooling and for a minimum of two years out of the possible four. Students who were registered in school for two years or longer but changed tracks or type of school were only 38 in total. They could not be viewed as a homogenous group of students in terms of the type of school or educational track and were therefore not included in the analysis.

Academic Achievement in the 10th Grade

The Directorate of Education provided standardized scores from the Icelandic National Examination in English, Icelandic, and mathematics, taken at the end of compulsory school (age 15, 10th grade). The measure for academic achievement was the mean score for students who had conducted at least two exams out of the three (Cronbach’s alpha = .84).

Data Analyses

One-way ANOVA models and Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to estimate the simple main effects of student groups at the end of compulsory school (age 15) and at upper secondary school four years later (age 19) on academic self-concept and sense of purpose as well as the simple main effect of time. Group means were compared using the effect size measures of Cohen’s ds, and Cohen’s drm was used to compare the means for each group between the two time points. The commonly used benchmarks of small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8), suggested by Cohen (Citation1988), are referred to in the results. To examine how academic self-concept and sense of purpose changed between the beginning and end of upper secondary school (from age 15 to 19) and whether it was dependent on the student group, two-way mixed ANCOVA models were used. Student group was used as a between-subjects factor, time (measures at age 15 and age 19) as a within-subjects factor, and z-standardized scores for academic achievement as a covariant where the scores were mean centred within each student group as recommended by B. A. Schneider et al. (Citation2015).Footnote2 Even though the principal component analysis and Cronbach’s alpha suggest that using the four items of the academic self-concept scale is valid, sensitivity analyses were conducted since the wording of two of the items do not refer to the academic context in a clear way. The results from the mixed ANCOVA models were equivalent after removing each of the items from the academic self-concept scale, further indicating the robustness of the measure.

Using Wilks’s statistic to test for attrition bias, there was a significant difference in the research variables at baseline between those who only participated at baseline and those who participated both at baseline and in the follow-up, Λ = 0.98, F(3, 1652) = 13.41, p < .001. The former group had lower academic self-concept (M = 3.12, SD = 0.62), a lower sense of purpose (M = 3.26, SD = 0.56), and poorer academic achievement (M = 30.78, SD = 8.04) compared to the latter group (M = 3.24, SD = 0.56; M = 3.33, SD = 0.57; M = 33.29, SD = 8.46, respectively). Thus, relative to those who did not participate in the follow-up, the final group of participants were biased in favour of students with stronger academic self-concepts, more positive view of their studies, and a stronger academic achievement. These attrition biases call for caution as they might affect the generalization of the findings. For example, the biases could restrict the evaluation of the effect of student groups as the variability of the dependent variables is constrained.

Results

Descriptive statistics for students’ academic self-concept and sense of purpose at age 15 (in the last year of compulsory school) and at age 19 (in upper secondary school), and for academic achievement at age 15 are shown in for the overall-sample and the three student groups. Students who chose academic track in academic schools showed higher academic achievement on the standardized tests at the end of compulsory school compared to students who chose vocational or academic track in multilateral schools, (F(2, 956) = 88.18, p < .001; Tukey’s post-hoc test p < .001).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for students’ academic self-concept, sense of purpose, and academic achievement for the overall sample, and comparison of student groups at age 15 and 19.

Academic Self-Concept at age 15

A simple main effects analysis showed a significant effect of student group on academic self-concept at age 15 (F(2, 989) = 24.83, p < .001). The Tukey’s post-hoc test revealed that students who selected an academic track at an all-academic school had higher academic self-concept in their last year of compulsory school than academic students in multilateral schools (MD = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < .001), with a small to medium difference in terms of Cohen’s d (ds = 0.41). Their academic self-concept was also higher than among vocational students (MD = 0.42, SE = 0.07, p < .001) where the difference was large (ds = 0.77). The academic self-concept of academic students in multilateral schools was also higher than among vocational students (MD = 0.20, SE = 0.08, p < .05), generating a small to medium difference of ds = 0.37.

Change Over Time in Academic Self-Concept From Age 15–19

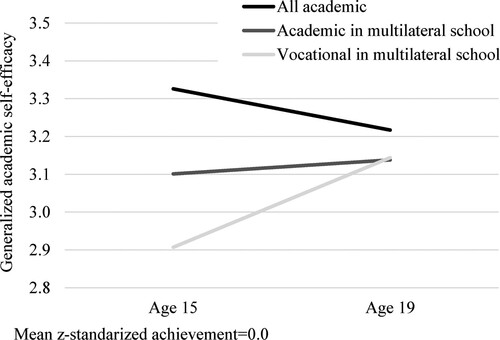

Holding academic achievement constant, a mixed model ANCOVA showed a statistically significant effect for the interaction “time × group” with regard to academic self-concept (F(2, 956) = 9.82, p < .001) (see ). This indicates that mean academic self-concept changed differently over time depending on the student group. The interaction effect is illustrated in , where covariates are evaluated at the overall z-standardized mean academic achievement.

Table 2. Mixed model ANCOVA for academic self-concept.

An analysis of simple main effect of time on academic self-concept showed that by the age of 19, academic self-concept had decreased among academic students in all-academic schools (F(1, 761) = 22.23, p < .001), although the effect was small (drm = 0.2), but increased among vocational students (F(1, 56) 5.31, p < .05) with a Cohen’s drm of 0.38. There was however not a simple main effect of time among academic students in multilateral schools (F(1, 169) = 0.614, p = .434). As a result of the development over time, the difference of academic self-concept between student groups that was detected at age 15 was not significant at age 19 (F(2, 989) = 1.86, p = .156).

Sense of Purpose at Age 15

The simple main effect of student group relating to sense of purpose at the end of compulsory school (age 15) was statistically significant (F(2, 988) = 7.72, p < .001). The Tukey’s post-hoc test showed that sense of purpose was greater among academic students in academic schools compared to vocational students (MD = 0.28, SE = 0.08, p < .01), with a medium difference between the groups according to Cohen’s d (ds = 0.53), but not compared to academic students in multilateral schools (MD = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p = .11).

Change Over Time of Sense of Purpose From Age 15 to 19

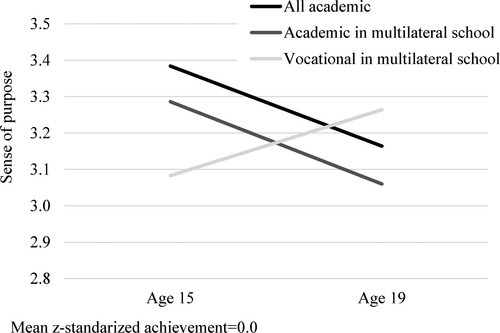

A mixed model ANCOVA with academic achievement as a covariant showed that mean sense of purpose changed differently over time depending on student group, (F(2, 955) = 9.87, p < .001) (see ). The interaction effect of “time × group” is illustrated in and shows how sense of purpose increased among vocational students while decreasing among academic students.

Table 3. Mixed model ANCOVA for sense of purpose.

A simple main effects analysis showed a significant effect of time in connection with a lowered sense of purpose among academic students in academic schools (F(1, 760) = 97.14, p < .001), and among academic students in multilateral schools (F(1, 169) 17.08, p < .001), but showed a reverse effect among vocational students, where sense of purpose increased (F(1, 56) = 4.45, p < 0.05). The effect of time was however below medium among all groups (drm = 0.39; drm = −0.37; drm = 0.34 respectively).

The findings for sense of purpose at age 19 showed significant difference between student groups, (F(2, 988) = 3.78, p < .05). The Tukey’s post-hoc test showed that sense of purpose was lower among academic students in multilateral schools than among vocational students (MD = 0.23, SE = 0.09, p < .05), with a Cohen’s ds of 0.39. No other difference was noted. The result of the over-time change showed that sense of purpose at age 19 was highest among vocational students, whereas sense of purpose at age 15 had scored highest among academic students in academic schools.

Discussion

One of the main findings of our study is the relationship found between both academic self-concept and sense of purpose at the end of compulsory school and students’ educational trajectories (type of track and school) at upper secondary school. At age 15, students who pursued an academic track in all-academic schools were the most confident about reaching their academic goals, second came those who also selected an academic track but in multilateral schools. The least confident group were the students who opted for vocational education. Moreover, students’ sense of purpose at age 15 was higher among those who chose to go to academic schools than among those who chose vocational education.

Another major finding is the definitive development of both academic self-concept and sense of purpose between the beginning and end of upper secondary school and how it differs depending on students’ track and school type, even after controlling for academic achievement. The major trend being that the attitudes and self-concept of vocational students strengthened over time while growing weaker among academic students in academic schools. Academic self-concept decreased from age 15 to 19 among academic students in academic schools, was stable among their counterparts in multilateral schools, and grew stronger among vocational students. This is in line with previous research, including the literature review of Belfi et al. (Citation2012). Moreover, the change in students’ beliefs in their educational capability detected at age 15 changed during upper secondary school to the extent that by the time they were 19 years old there was no difference between the groups. Students’ sense of purpose decreased among both groups of academic students while it increased among vocational students. These findings are the opposite of what to expect from the differentiation-polarization theory (e.g., Berends, Citation1995; Van Houtte, Citation2006). At age 15, vocational students had the lowest sense of purpose of the three student groups, but by the age of 19, their sense of purpose had become stronger than that of academic students in multilateral schools. Although the effect sizes for the changes over time were small, the distinguishable trend of different student groups cannot be ignored.

Both sense of purpose and academic self-concept was relatively low at the end of compulsory school but grew stronger at upper secondary level among vocational students. This may reflect the strong academic emphasis in the Icelandic compulsory school system while at upper secondary school vocational students can choose subjects more in line with their interests and abilities. The opposite trend was observed for academic students which also links to the strong academic emphasis at compulsory level as well as the high value attributed to academic education. As a result, most students enrol in academic tracks in upper secondary school. It is reasonable to assume that a part of these students developed lower academic self-concept and lost their sense of purpose since they felt pressured towards academic education instead of a more suitable VET programme.

Tracking students have repeatedly been found to be beneficial for weaker students’ academic self-concept while being rather detrimental for stronger students’ attitudes towards themselves (Belfi et al., Citation2012). Our findings support this and the decrease in academic self-concept among students in all-academic schools found in our study is in line with the big-fish-little-pond effect. We found that strong academic students generally had strong academic self-concept at the end of compulsory school, suggesting that at this stage they compared their abilities with other teens in their heterogeneous class. When these students started their studies at all-academic upper secondary schools, they were now surrounded by similar or stronger abled students to whom they compared their skills and abilities. As a result, their academic self-concept declined because they no longer saw themselves as belonging to the group composing the strongest students in class. However, vocational students found themselves in a school environment that appreciated their skills and interests and among other students with similar abilities and strengths as themselves. The new situation meant that these students had now acquired a different kind of reference group and therefore a new framework through which they could build their self-concept. This suggests that both student groups, i.e., students in all-academic schools and vocational students, acquired a different kind of reference group where they now compared themselves and their abilities to more homogenous fellow students, resulting in a stronger effect of a within-group comparison, as opposed to the across-group comparison among students described by the basking in reflected glory effect. This is somewhat in line with the study of Liu et al. (Citation2005), where low-track students had a more positive self-concept than high-track students three years after being tracked, even though it was the other way around when they were first tracked.

Our findings concerning students’ sense of purpose in their education do not support the differentiation-polarization theory, according to which we would expect students’ views to become more negative among vocational students over time, since their track is commonly viewed as less valuable and less prestigious than academic tracks in the curriculum hierarchy. Here we found that sense of purpose decreased among academic students regardless of their type of school but grew stronger among vocational students. There is a reason to stress that the current study differs in several ways from other studies that have focused on the differentiation-polarization theory which limits the comparability with earlier findings. First, a vast bulk of the existing research was conducted among students that were being tracked based on their academic abilities at a younger age than in the Icelandic system. Being a vocational track student is considered below par and the assumption is that the student is not fit to meet the standards set by academic tracks (Dockx et al., Citation2019). Receiving this message at a young age could lead vocational students to develop negative school attitudes where they feel like they have failed academically. Conversely, academic students are aware of the high status of their track and see schooling as a positive experience. Delaying this across-group comparison until students are older could reduce the effect of the polarization on their school attitudes since their self-concept and attitudes are more developed in general. A second way in which the current study differs from previous ones is the fact that it builds on quantitative data. Most support for the differentiation-polarization theory is found in qualitative research (e.g., Ball, Citation1981; Hargreaves, Citation1967; Lacey, Citation1970), but our findings contradict both the qualitative ones and the few quantitative studies that have been conducted (see Berends, Citation1995; Van Houtte, Citation2006; Van Houtte & Stevens, Citation2009). The third factor relates to the operationalization of students’ school attitudes. The differentiation-polarization theory focuses on school culture or group culture while our measure of school attitudes addresses the factor of sense of purpose on the individual level. This factor of students’ school attitudes focuses on how school is preparing them for the future, and we can assume their views to differ depending on their type of track and school. The academic tracks can be seen as a preparation for entering university while most of the vocational tracks prepare students for the labour market. The fact that vocational students gain a stronger sense of purpose when at upper secondary school suggests that they see value in studying for their future job, while academic students might struggle with understanding how some of their subjects relate to the field of study that they are aiming for at university. It should therefore be noted that an attempt to compare this single factor of students’ views to a large-scale ethnographic research of students’ polarization of attitudes should be done with caution. Including a measure of the climate or culture of the student group could be valuable for future research.

Limitations of the Study

The possibility of selective attrition from follow-up data cannot be excluded. One implication of finding the final group of participants to be biased in favour of students with stronger academic self-concept, greater sense of purpose and stronger academic achievement compared to those missing from the follow-up study might be that our estimates of change are restricted. The group of participants who dropped out of the study before the follow-up were more similar to the vocational students than to the academic students when compared at baseline, suggesting the possibility of an even stronger interaction effect had they remained through to the end of the study. Another limitation is the fact that there are no all-vocational schools in Iceland. The polarization of study involvement and self-esteem between vocational and academic students have been found to be greater in multilateral schools than in categorical schools. Van Houtte et al. (Citation2012) conjectured that vocational students in multilateral schools tend to look toward academic fellow students as a comparative reference group, giving rise to feelings of relative deprivation and resulting in greater study disengagement. However, the polarization is less evident in vocational schools, in the absence of such stark contrasts. Looking more deeply into the issue in the context of a late tracking school system could prove valuable for the discourse surrounding the subject, though such an endeavour could not be carried out in Iceland, for reasons mentioned above. Our research builds on strong, longitudinal, quantitative data. However, a mixed-method approach with in-depth interviews or focus groups among students following the quantitative analysis would have been valuable for a deeper understanding of the findings. Finally, the study is focused on the city area, excluding students from other parts of Iceland. This point should be kept in mind when comparing our results with other research targeting students in both urban and rural areas.

Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to use quantitative data from an educational model with late tracking to test the big-fish-little-pond effect, the basking in reflected glory effect and the differentiation-polarization theory. Taken together, the results on academic self-concept give support to the big-fish-little-pond effect, suggesting a weaker effect of the basking in reflected glory effect, but the results on students’ sense of purpose do not give support to the differentiation-polarization theory. Our findings have implications for school policy and practice and for further research.

Firstly, knowing that academic and vocational students develop their academic self-concept and their sense of purpose in a different way through upper secondary school gives policy makers and educators valuable information on how to positively influence the self-concept of students according to their educational track and school environment. Given the strong academic emphasis at the compulsory school level in Iceland, it is not surprising that students’ self-concept and school attitudes at age 15 are more positive among academically strong students. The fact that vocational students build a stronger academic self-concept and gain a clearer sense of purpose in their studies at upper secondary school suggests that students may have benefitted from a stronger vocational focus at a younger age, when still in compulsory school. Early tracking can have a positive effect on the academic achievement of stronger students (Becker et al., Citation2012) but it has been shown to foster achievement gaps, increase educational inequalities and the stratification of educational opportunities (Belfi et al., Citation2012; Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006). Therefore, our findings should not be seen as an argument for students to be divided into academic and vocational tracks at an earlier age which would raise even more questions about which student groups that would benefit. We suggest that all students be given the opportunity to find their strengths and purpose at the compulsory school level, in both academic and vocational subjects. As Shamah and MacTavish (Citation2015) argue, if students are to develop their sense of purpose they need to be provided with opportunities to see the relevance of their course of study and systematically develop their strengths and talents. To give vocational subjects more value in compulsory school sends a clear message that education is more than the core academic subjects, in contrast to the emphasis that is generally considered acceptable. Fostering the strong sense of purpose among academic students throughout upper secondary school is also of importance. Emphasizing career education and guidance, where students learn about higher education and labour market topics, is likely to contribute to this aim.

Secondly, the support of the big-fish-little-pond effect found in the study motivates further examination into how students’ self-concept may differ as a function of the academic achievement of their peers and their own achievement when taking the type of track and school into account. This can only be tested empirically using an “objective” measure of academic achievement of all participants in the sample. Fortunately, we have access to students’ outcomes from the 10th grade national standardized tests, which will be of great significance for further research. This will also create insights on how to maintain or strengthen academic self-concept and sense of purpose among students in academic schools. With time, and additional data in the longitudinal setting of the research, we will also be able to see the graduation rate for the participants in the study and if and how their educational trajectories are affected by their academic self-concept, sense of purpose, type of track and upper secondary school, as well as by their socioeconomic factors, and their academic achievement.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all researchers that contributed to the International Study of City Youth project. The young people, parents, teachers, and principals who kindly consented to participate in this project are also gratefully thanked.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Both Hargreaves (Citation1967) and Lacey (Citation1970) used the terms differentiation and polarization, but Hammersley (Citation1985) was the first to refer to their theoretical ideas as the differentiation-polarization theory.

2 The distributions in both models were slightly negatively skewed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test of normality (p < .05). Keeping the size of the sample in mind (the central limit theorem) and that two-factor mixed ANOVA is robust to violations of normality, this should not affect the main conclusions. There was homogeneity of variances (p > .05) in both models and homogeneity of covariances (p > .05) for the academic self-concept model, as assessed by Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances and Box’s M test, respectively. The p-value in Box’s M test for the sense of purpose model was 0.017 which is strictly speaking a sign of a violation of the assumption of homogeneity of covariances. However, according to Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2001), the test is acknowledged to be too strict and they recommend to test at the p = .001 level for unequal sample sizes as is the case for the sense of purpose model.

References

- Abraham, J. (1989). Testing Hargreaves’ and Lacey’s differentiation-polarisation theory in a setted comprehensive. The British Journal of Sociology, 40(1), 46–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/590290

- Antikainen, A. (2006). In search of the Nordic model in education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743258

- Arnesen, A., & Lundahl, L. (2006). Still social and democratic? Inclusive education policies in the Nordic welfare states. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743316

- Ball, S. J. (1981). Beachside comprehensive: A case-study of secondary schooling. University Press.

- Becker, M., Lüdtke, O., & Trautwein, U. (2012). The differential effects of school tracking on psychometric intelligence: Do academic-track schools make students smarter? Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027608

- Belfi, B., Goos, M., De Fraine, B., & Van Damme, J. (2012). The effect of class composition by gender and ability on secondary school students’ school well-being and academic self-concept: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 7(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.002

- Berends, M. (1995). Educational stratification and students’ social bonding to school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 16(3), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569950160304

- Betts, J. R. (2011). The economics of tracking in education. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol 3, pp. 341–381). North-Holland.

- Blondal, K. S., Jonasson, J. T., & Tannhäuser, A.-C. (2011). Dropout in a small society: Is the Icelandic case somehow different? In S. Lamb, E. Markussen, R. Teese, N. Sandberg, & J. Polesel (Eds.), School dropout and completion. International comparative studies in theory and policy (pp. 233–251). Springer.

- Blondal, K. S., Jónasson, J. T., & Hafthórsson, A. (2019). Student disengagement in inclusive Icelandic education: A question of school effect in Reykjavík. In M. Van Houtte & J. Demanet (Eds.), Resisting education: A cross-national study on systems and school effects (pp. 117–133). Springer.

- Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382

- Carlgren, I., Klette, K., Mýrdal, S., Schnack, K., & Simola, H. (2006). Changes in Nordic teaching practices: From individualised teaching to the teaching of individuals. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 301–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743357

- Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

- Craven, R. G., & Marsh, H. W. (2008). The centrality of the self-concept construct for psychological wellbeing and unlocking human potential: Implications for child and educational psychologists. Educational and Child Psychology, 25(2), 104–118.

- Demanet, J., van den Broeck, L., & van Houtte, M. (2018). Social inequality in attitudes and behavior: The implications of the Flemish tracking system for equity. In L. D. Hill & F. J. Levine (Eds.), Global perspectives on education research (pp. 159–181). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351128421-7

- Dockx, J., De Fraine, B., & Vandecandelaere, M. (2019). Tracks as frames of reference for academic self-concept. Journal of School Psychology, 72, 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.12.006

- Easton, J. Q., Ponisciak, S., & Luppescu, S. (2008). From high school to the future: The Pathway to 20. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/high-school-future-pathway-20

- Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 620–146). W. H. Freeman and Company. https://doi.org/10.2307/1422172

- Eiríksdóttir, E., Ragnarsdóttir, G., & Jónasson, J. T. (2018). Þversagnir og kerfisvillur? Kortlagning á ólíkri stöðu bóknáms- og starfsnámsbrauta á framhaldsskólastigi [Paradoxes and system errors? Mapping of the different status of academic and vocational programs at the upper secondary level]. Netla - Veftímarit Um Uppeldi Og Menntun [Netla - Online Journal on Pedagogy and Education]. https://doi.org/10.24270/serritnetla.2019.7

- Frímannsson, G. H. (2006). Introduction: Is there a Nordic model in education? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743233

- Gerdes, H., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1994). Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00935.x

- Hammersley, M. (1985). From ethnography to theory: A programme and paradigm in the sociology of education. Sociology, 19(2), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038585019002007

- Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2006). Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries. The Economic Journal, 116(510), C63–C76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

- Hargreaves, D. H. (1967). Social relations in a secondary school. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd.

- Imsen, G., Blossing, U., & Moos, L. (2016). Reshaping the Nordic education model in an era of efficiency. Changes in the comprehensive school project in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden since the millennium. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(5), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1172502

- Kautto, M., Fritzell, J., Hvinden, B., Kvist, J., & Uusitalo, H. (2001). Nordic welfare states in the European context. Routledge.

- Kember, D., Ho, A., & Hong, C. (2008). The importance of establishing relevance in motivating student learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787408095849

- Lacey, C. (1970). Hightown grammar: The school as a social system. Manchester University Press.

- Lamb, S., Jackson, J., & Rumberger, R. (2015). ISCY technical paper: Measuring 21st century skills in ISCY.

- LaRossa, R., & Reitzes, D. C. (2009). Symbolic interactionism and family studies. In P. Boss, W. J. Doherty, R. LaRossa, W. R. Schumm, & S. K. Steinmetz (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 135–166). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_6

- Lavrijsen, J., & Nicaise, I. (2017). Systemic obstacles to lifelong learning: The influence of the educational system design on learning attitudes. Studies in Continuing Education, 39(2), 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2016.1275540

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Larkin, K. C. (1984). Relation of self-efficacy expectations to academic achievement and persistence. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(3), 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0167.31.3.356

- Lerang, M. S., Ertesvåg, S. K., & Havik, T. (2018). Perceived classroom interaction, goal orientation and their association with social and academic learning outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1466358

- Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308223

- Liu, W. C., Wang, C. K. J., & Parkins, E. J. (2005). A longitudinal study of students’ academic self-concept in a streamed setting: The Singapore context. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(4), 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X42239

- Marks, G. N. (2005). Cross-national differences and accounting for social class inequalities. International Sociology, 20(4), 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580905058328

- Marsh, H. W. (1987). The big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(3), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.3.280

- Marsh, H. W., Kong, C.-K., & Hau, K.-T. (2000). Longitudinal multilevel models of the big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept: Counterbalancing contrast and reflected glory effects in Hong Kong schools. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.337

- Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Arens, A. K. (2019). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy. Beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000281

- Marsh, H. W., Seaton, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Hau, K. T., Omara, A. J., & Craven, R. G. (2008). The big-fish-little-pond-effect stands up to critical scrutiny: Implications for theory, methodology, and future research. Educational Psychology Review, 20(3), 319–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9075-6

- Ministry of Education Science and Culture. (2012). The Icelandic national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools: General section.

- Moos, L., & Krejsler, J. B. (2021). Nordic school policy approaches to evidence, social technologies and transnational collaboration. In J. B. Krejsler & L. Moos (Eds.), What works in Nordic school policies? Educational governance research (Vol 15, pp. 3–26). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66629-3_1

- Nairz-Wirth, E., Feldmann, K., & Spiegl, J. (2017). Habitus conflicts and experiences of symbolic violence as obstacles for non-traditional student. European Educational Research Journal, 16(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116673644

- OECD. (2020). PISA 2018 results (volume V): Effective policies, successful schools. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ca768d40-en

- Palardy, G. J., & Rumberger, R. W. (2019). The effects 21st century skills on behavioral disengagement in Sacramento high schools. In J. Demanet & M. Van Houtte (Eds.), Resisting education: A cross-national study on systems and school effects (pp. 53–80). Springer. http://gradnation.americaspromise.org/

- Preckel, F., & Brüll, M. (2010). The benefit of being a big fish in a big pond: Contrast and assimilation effects on academic self-concept. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(5), 522–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2009.12.007

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

- Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

- Rosenbaum, J. E., Bailey, T., Deil, R., Hallinan, M., Ludwig, J., Pallas, A., Miller, S., & Biddle, B. (1998). College-for-all: Do students understand what college demands? Social Psychology of Education, 2(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009653501824

- Schneider, B. A., Avivi-Reich, M., & Mozuraitis, M. (2015). A cautionary note on the use of the Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) in classification designs with and without within-subject factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00474

- Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098

- Schütz, G., Ursprung, H. W., & Wößmann, L. (2008). Education policy and equality of opportunity. Kyklos, 61(2), 279–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00402.x

- Shamah, D., & MacTavish, K. A. (2015). Purpose and perceptions of family social location among rural youth. Youth & Society, 50(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X15583655

- Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407–441. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407

- Statistics Iceland. (2018). Nýnemum fækkar í starfsnámi á framhaldsskólastigi [Fewer enrol in vocational studies at upper secondary school]. https://hagstofa.is/utgafur/frettasafn/menntun/nynemar-a-framhaldsskolastigi-1997-2016/

- Statistics Iceland. (2020). Enrolment at upper secondary level by sex, age and domicile 1999-2018. https://statice.is/

- Stoker, G., Liu, F., & Arellano, B. (2017). Understanding the role of noncognitive skills and school environments in students’ transitions to high school (REL 2018-282). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578859.pdf

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Telhaug, A. O., Mediås, A., & Aasen, P. (2006). The Nordic model in education: Education as part of the political system in the last 50 years. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 245–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743274

- Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H. W., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Tracking, grading, and student motivation: Using group composition and status to predict self-concept and interest in ninth-grade mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 788–806. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.788

- Van Houtte, M. (2005). Global self-esteem in technical/vocational versus general secondary school tracks: A matter of gender? Sex Roles, 53(9), 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7739-y

- Van Houtte, M. (2006). School type and academic culture: Evidence for the differentiation-polarization theory. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270500363661

- Van Houtte, M., Demanet, J., & Stevens, P. A. (2012). Self-esteem of academic and vocational students: Does within-school tracking sharpen the difference? Acta Sociologica, 55(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699311431595

- Van Houtte, M., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2009). Study involvement of academic and vocational students: Does between-school tracking sharpen the difference? American Educational Research Journal, 46(4), 943–973. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209348789

- Westbroek, H. B., Klaassen, K., Bulte, A., & Pilot, A. (2010). Providing students with a sense of purpose by adapting a professional practice. International Journal of Science Education, 32(5), 603–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902721699

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/CEPS.1999.1015

- Wolff, F., Lüdtke, O., Helm, F., & Möller, J. (2021, February). Integrating the big-fish-little-pond effect, the basking-in-reflected-glory effect, and the internal/external frame of reference model predicting students’ individual and collective academic self-concepts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101952

- Wu, H., Guo, Y., Yang, Y., Zhao, L., & Guo, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the longitudinal relationship between academic self-concept and academic achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1749–1778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09600-1

- Xerri, M. J., Radford, K., & Shacklock, K. (2018). Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective. Higher Education, 75(4), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0162-9

- Zeiser, K., Scholz, C., & Cirks, V. (2018). Maximizing student agency: Implementing and measuring student-centered learning practices (technical appendix). American Institute for Research.

Appendix

The Nordic education system and late tracking

It is important to be clear about the meaning of the Nordic education model and whether we can in fact describe it as a holistic system common to all the Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Several researchers have concluded that the Nordic countries stand out from other European and OECD nations and that there really is a distinct social democratic welfare model of the Nordic countries. The countries have, nevertheless, also incorporated some traits of the liberal welfare state (Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Kautto et al., Citation2001).

Education is considered to be one of the most important components of the welfare state, which aims to minimize differentiation and social exclusion (Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006). Working towards equity, participation, and welfare, all the Nordic school systems have a publicly funded comprehensive primary and lower secondary school system. One central aspect shared by the education policies in the Nordic countries is the aspect of inclusive education, aiming to have all children in mainstream schools and the fundamental idea in the education policies is to provide equal opportunities to all regardless of their background or special needs and that for education to be free of charge, even at the tertiary level (Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Carlgren et al., Citation2006; Telhaug et al., Citation2006). There are very few private schools in Finland, Iceland, and Norway but the percentage of students who attend government-dependent private schools in Sweden has risen during the last two decades while Denmark has a longer tradition of private schools at the primary and lower secondary level (OECD, Citation2020).

Typical to Nordic educational systems is the mixed ability classes and the lack of tracking or streaming until the age of 16 (Antikainen, Citation2006; Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006; Carlgren et al., Citation2006; Telhaug et al., Citation2006), referred to here as late tracking. It is well known from previous research that early tracking, or other form of educational differentiation at the lower school level, can increases social and educational inequalities. Some form of educational differentiation is inevitable at some point but it should take place later rather than earlier with the flexibility to move between tracks or locations (Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006; Marks, Citation2005; Nairz-Wirth et al., Citation2017). The comprehensive education in the Nordic countries holds a positive reputation from a comparative perspective with little or no tracking at the primary and lower secondary level, producing low social inequalities (Antikainen, Citation2006; Arnesen & Lundahl, Citation2006).

Comparing the similarities and differences of the school system in five countries is a difficult task that includes taking into account the different societal and historical context of each country as well as internationally (Moos & Krejsler, Citation2021). During the twenty-first century there have been signs of diminishing emphasis on the Nordic models’ values of equality and inclusion where strategies such as efficiency, competition, and decentralization have gained more attention (Imsen et al., Citation2016). Despite these changes in the Nordic, Frímannsson (Citation2006) and Imsen et al. (Citation2016) conclude that it is reasonable to refer to a Nordic model of education, consisting of common aims and methods. The comprehensive primary and lower secondary school system is the method common to all the Nordic countries to equalize opportunities and to provide students with valuable skills. Despite the mutual factors, each of the Nordic countries has its distinguishing elements while all incorporate the basic values of equality. Antikainen (Citation2006) argues how the Nordic education model can only be referred to as an ideal type, and instead of talking about one model, the education system is different in each country, even though they hold these similar patterns between them.