ABSTRACT

Teachers with strong professional agency (TPA) in the classroom make efforts to constantly learn and develop their teaching practices. The aim of the present study is to identify teachers’ different TPA development profiles and their association with experiencing burnout symptoms and abilities to use proactive strategies in regulating well-being. A total of 1920 Finnish primary school teachers responded during the two-year follow-up study. The data were analysed using longitudinal latent profile analysis. Four profiles were found: (1) High and stable professional agency; (2) Moderately high professional agency; (3) Increasing professional agency; and (4) Decreasing professional agency. Most teachers experienced strong and stable professional agency and only few changes in their sense of professional agency over time. Socio-contextual burnout symptoms and proactive strategy use differentiated the profiles well. Teachers with lower professional agency profiles experienced more burnout symptoms and less ability to use proactive strategies.

1. Introduction

Teachers with a strong sense of professional agency in the classroom make efforts to learn and develop at work (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012, Citation2014; Soini et al., Citation2016). They are also engaged in school development, invest in promoting students’ learning, and have lower levels of stress (Bruce et al., Citation2010; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Vermunt & Endedijk, Citation2011). Accordingly, teachers’ professional agency (TPA) seems to provide resources for both new learning and teacher well-being. Teachers’ strong sense of professional agency has been shown to predict itself over time (Heikonen et al., Citation2020; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). It has also shown to be associated with decreased risk of perceived exhaustion and inadequacy in teacher–student interaction (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022) as well as increased ability to use proactive strategies in preventing burnout (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015).

At the same time, understanding of intra-individual variation between teachers in the development of their sense of professional agency in the classroom based on a person-centred approach (see Bergman & Magnusson, Citation1997) is limited. Even less is known about the interrelation between proactive strategy use and TPA in the classroom. There are only few longitudinal studies on TPA in general (Heikonen et al., Citation2020; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022), and even fewer exploring intra-individual variation in perceived professional agency. Hence, our study is among the first to examine TPA development by combining longitudinal and person-centred approaches and exploring professional agency in relation to proactive strategy use and teacher burnout.

1.1. The development of teacher’s professional agency

Teachers’ professional development calls for active efforts to develop and learn in the classroom, to constantly rethink and reflect on one’s teaching and way of thinking.

TPA in the classroom refers to teachers’ motivation, efficacy and skills to actively learn through working together with and for the benefit of students (Edwards, Citation2005; Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012, Citation2014; Sachs, Citation2000; Soini et al., Citation2016; Turnbull, Citation2005). A strong sense of professional agency in the classroom is suggested to be a precondition for professional development and growth. It involves reflecting on one’s teaching in order to learn, and making efforts to develop pedagogical practices and the learning environment in collaboration with the students (Edwards, Citation2005; Eraut, Citation2004; Ketelaar et al., Citation2012; Meirink et al., Citation2007; Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). The evolution of such teacher activities is highly embedded in interactions with the students.

Learning by reflecting is a foundation for TPA in the classroom (Hoekstra et al., Citation2007; Mälkki, Citation2019; Soini et al., Citation2015; Toom et al., Citation2015). Learning by reflecting refers to an open and curious attitude and desire for learning, as well as strategies to evaluate one’s thinking and teaching. However, co-regulative and collaborative learning are also shown to be crucial for teacher development (e.g. Akiba et al., Citation2019; Saariaho, Citation2020). Accordingly, co-creating a collaborative learning environment and transforming practices towards building functioning relationships and a stimulative atmosphere for learning with students in the classroom is another main element of professional agency in the classroom.

Our previous studies show that these two modes of TPA; learning by reflecting, and transforming classroom practices and the learning environment collaboratively, seem to develop hand in hand and enhance each other (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). In other words, the more teachers aim to learn by reflecting, the more they learn together with students, as well. Even though Finnish teachers generally have a strong and stable sense of professional agency (Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022), they face an array of opportunities and challenges during their careers that affect their professional development. It has been shown that teachers’ professional development does not necessarily progress as a steady rise or from stage to stage, but the development trajectories are more likely to vary depending on personal factors, such as skills and attitudes, and contextual factors, such as changes in the working community, that provide affordances and constrains for teacher development (Dall’Alba & Sandberg, Citation2006; Kyndt et al., Citation2016; Vermunt & Endedijk, Citation2011). There are only few studies that have examined the relation between TPA and gender or work experience. In our previous studies we have not found differences in gender or work experience in relation to teachers’ perceptions of professional agency (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Pyhältö et al., Citation2014).

Based on the above, we presume that also the intra-individual development of TPA is likely to be non-linear and affected by both personal and contextual factors. We further assume that developing a strong sense of professional agency can be an important asset in overcoming the different changes and challenges of a teaching career (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016) by enabling intentional modification of working environment dynamics and obtaining new competences.

1.2. Teacher burnout and professional agency in the classroom

School does not always provide an optimal working environment for teachers. In fact, levels of teacher stress have repeatedly shown to be elevated compared to other highly educated professionals (Desrumaux et al., Citation2015; Hakanen et al., Citation2006). Prolonged and severe work-related stress can gradually result in teacher burnout (Foley & Murphy, Citation2015; see also Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Teacher burnout in the school’s social context consists of three different symptoms: exhaustion, characterized by feelings of strain and lack of energy at work; cynicism, referring to frustration and sense of irrelevance towards work despite efforts, particularly toward colleagues; and inadequacy, consisting of experiences of failure and inadequate competency, especially in teacher-student interaction (Brouwers & Tomic, Citation2000; Hakanen et al., Citation2006; Lindqvist et al., Citation2017; Maslach & Leiter, Citation2016; Pietarinen et al., Citation2013).

Individual and contextual antecedents of teacher burnout, such as work experience and working environment, have been widely recognized in the teacher burnout literature (e.g. Brewer & Shapard, Citation2004; Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2014; Gavish & Friedman, Citation2010). Particularly, social interactions with students, colleagues and parents have been shown to contribute to the development of teacher burnout (Aloe et al., Citation2014; Cano-Garcia et al., Citation2005; Dorman, Citation2003; Gavish & Friedman, Citation2010). They seem to play a complementary, but distinct, role in the development of burnout symptoms. While failures and disappointments with students tend to give rise to feelings of inadequacy, unsolved problems within the work community and dissension with colleagues can lead to cynicism (Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2014; Pyhältö et al., Citation2011). In contrast, the interrelation between teacher learning and burnout has been explored to a lesser extent.

The effect of teacher’s strong self-efficacy beliefs and motivation for learning in reducing and preventing burnout has been recognized widely (e.g. Ryan & Deci, Citation2016; Zeng et al., Citation2019). In addition, adapting new learning strategies can increase teacher’s sense of personal accomplishment and decrease emotional exhaustion (Oliveira et al., Citation2021). These three, self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and strategies for learning, are the main elements of TPA. Our recent variable-centred studies showed that teacher’s sense of professional agency in the classroom and burnout symptoms are mainly negatively associated with each other. Especially, teacher engagement in regulating learning collaboratively with students reduces exhaustion and feelings of inadequacy (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). However, a teacher’s high tendency to merely reflect on their teaching behaviour may even increase feelings of inadequacy and cynicism toward colleagues (Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). We seek to clarify this ambivalence by investigating the relation between individual profiles of TPA and burnout symptoms. Furthermore, we presume that employing a strong or increasing professional agency trajectory in the classroom is likely to reduce teachers’ risk of burnout symptoms.

1.3. Proactive strategies as regulators of teacher burnout and professional agency in the classroom

Teachers can use several strategies when confronting stressful situations. Commonly used reactive strategies include adapting to or ignoring the challenging situation (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013b), modifying the environment, or processing encountered emotions (Foley & Murphy, Citation2015). However, it is important to note that also proactive strategies can be utilized to help prevent the development of teacher burnout by utilizing the resources available and creating new ones (e.g. Pietarinen et al., Citation2016, Citation2021; Pyhältö et al., Citation2021; Schwarzer & Hallum, Citation2008; Straud et al., Citation2015; Väisänen et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). It has been shown that proactive, social, and optimistic strategies are more effective than reactive ones when dealing with stressors and burnout prevention (Klassen & Durksen, Citation2014; Pietarinen et al., Citation2013b).

Proactive strategies can be divided into self-regulation and co-regulation. Proactive self-regulation strategies refer to an individual’s strategies to regulate their emotions, behaviour and cognition, such as reducing duties or slowing down the work pace, while proactive co-regulation strategies involve joint efforts, such as promoting reciprocal help and support among colleagues to buffer burnout development (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013b; Tikkanen et al., Citation2017; Väisänen et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). There is a growing body of evidence on the benefits of using proactive strategies in teacher burnout prevention in general (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013b, Citation2021; Väisänen et al., Citation2018a), yet understanding of the relationship between TPA and proactive strategies is still in its early stages.

The research evidence suggests that TPA in the teacher community, i.e. the perceived capacity to intentionally use others as a resource for learning and, respectively, to act as a support for them (Edwards, Citation2005; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012), have a positive association with proactive co-regulative strategy use. This indicates that the processes of building and modifying professional relationships in the professional community and the self- and co-regulative strategies used for reducing burnout symptoms are intertwined by nature (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Tikkanen et al., Citation2017). However, this relationship between proactive strategies and TPA agency in the classroom, i.e. teachers’ perceived capacity to learn by modifying and reflecting on teacher-student interaction, has not been studied widely. It can be assumed that a teacher who has a strong sense of agency in the classroom is more likely to use proactive strategies to prevent work-related burnout. More specifically, teachers’ perceived capacity to anticipate, transform and evaluate teacher-student interaction may result in more active proactive strategy use also in terms of reducing burnout (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Soini et al., Citation2016).

1.4. Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to examine different profiles of primary school teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom over time and whether the profiles differ in terms of experienced burnout symptoms, perceived abilities to use proactive strategies, and gender and work experience. The following hypotheses were tested:

H1. Different profiles of teacher’s sense of professional agency in the classroom, including collaborative learning environment and transformative practice, and reflection in the classroom, can be detected among primary school teachers. The majority of teachers employ relatively strong and stable professional agency over time (Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). However, we also expect to find a small group of teachers who experience changes in their sense of professional agency. (Heikonen et al., Citation2020)

H2. The profiles differ from each other in terms of experienced burnout symptoms. We assume that teachers’ strong sense of professional agency is related to lower levels of burnout symptoms. (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022)

H3. The professional agency profiles differ in terms of reported use of proactive strategies. We expect that teachers with a strong sense of professional agency and experiencing lower levels of burnout tend to use proactive strategies more often. (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015)

H4. Based on our previous studies, we assume that the professional agency profiles do not differ in terms of teacher’s gender or work experience. (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Pyhältö et al., Citation2014)

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and data collection

The study took place during 2016–2018 when the new Finnish core curriculum was being implemented in schools. This reform urged teachers to adopt the new curriculum, reflect on and transform their ways of conducting teaching and learn new practices, so it provides a rich context to study teachers’ professional agency development. Implementing the new curriculum is a long-term process (Sahlberg, Citation2017), so a two-year time period was chosen for the research project. The data collection followed the first three implementation years and was collected in the autumn of 2016, 2017 and 2018.

The data was collected using clustered sampling in Finnish comprehensive schools (n = 75). In this study we focus on teachers who reported that they teach in primary schools, and we refer to them as primary school teachers. Finnish primary school teachers complete a 5-year university education and graduate with a master’s degree in education. After their teacher education they are qualified to teach grades 1–6 (age 7–13) in primary school. Altogether 1920 primary school teachers responded, of which 1119 teachers participated at T1, 1171 at T2, and 1137 at T3. All of the teachers in the schools were asked to answer the survey at each time of measurement. In total, 477 primary school teachers participated at all times, 224 participated at T1 and T2 only, 221 participated at T2 and T3 only, and 110 participated at T1 and T3 only.

The majority of participants were female (68%, n = 1308; men: 19%, n = 365). Average work experience was 15 years at T1 (min/max 0/46). At Time 1 there were 49 primary and 16 combined primary and lower secondary schools in which the primary school teachers reported that they worked. The other ten schools were lower secondary schools and thus not included in the study. The data collection was based on informed consent and the guidelines for responsible conduct of research and ethical principles were followed throughout the study (Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity, Citation2019).

2.2. Measurements

The data were collected through the Curriculum Reform Inventory developed by Pietarinen et al. (Citation2017) (see also Pietarinen et al., Citation2021; Soini et al., Citation2021; Sullanmaa et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). The following three scales were used in this study: (1) Teacher’s professional agency in the classroom, comprising two subscales: Collaborative environment and transformative practice, and Reflection in the classroom (Pyhältö et al., Citation2012, Citation2014); (2) Socio-contextual burnout, comprising three subscales: Cynicism towards teacher community, Inadequacy in teacher-pupil interaction, and Exhaustion (Elo et al., Citation2003; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981; Pietarinen et al., Citation2013a, Citation2013b); and 3. Proactive strategies, comprising two subscales: Self-regulation and Co-regulation (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013b, Citation2021). The scales, subscales and items are described in more detail in the supplemental material. All items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 7 = completely agree) except the item work-related stress, which was rated on a ten-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 10 = very much).

2.3. Analysis

First, preliminary examination of the data was carried out. The main reason for missing values was that not all teachers participated at each time of measurement. Some teachers had stopped or started working at the schools during the follow-up study. Due to this, data were not missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: x2(2617) = 2777.837; p = .014) and the missing value percentages varied from 39.0 to 43.1 per item. Gender and work experience distribution remained similar regardless of which response times the respondent had participated in. Pairwise comparisons showed that teachers who responded only at T3 reported slightly higher levels of inadequacy than teachers who responded at T1, T2 or at several time points, otherwise there were no differences in the studied variables in terms of how teachers had responded by different times of measurement. In conclusion, we assume the data to be missing at random (MAR), and thus use full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation in the analysis (Schafer & Graham, Citation2002).

The data have a nested structure, so the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which depicts the proportion of variance in the used measurements between schools, was tested (see Table S1 in supplemental material). The suggested interpretation of ICC is that .05 represents small, .10 medium and .15 large effect (Hox, Citation2010). According to the ICC (range T1: 1–17%, T2: 1–13%, and T3: 1–14%) there were only two scales, cynicism towards teacher community and co-regulation, in which the coefficient showed values over 5% (Table S1 in supplemental material). This nesting of teachers within schools was taken into account in the CFA analyses using complex option, i.e. design-based correction of standard errors in Mplus (Asparouhov, Citation2005).

After the preliminary examination, the data was analysed using structural equation modelling and the structural validity of the TPA scales was examined using confirmatory factor analysis. The statistics used to evaluate the model fit were the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and, with caution due to its sensitivity to a large sample size, the chi square test. The criteria for adequate or good fit were above .90/.95 for CFI and TLI and below .07/.05 for RMSEA (Hooper et al., Citation2008; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). After that, measurement invariance was tested for the TPA scales at three levels: configural (the baseline model or one-factor longitudinal model with adequate model fit), metric (model where the factor loadings are constrained to be equal between time points), and scalar (factor loadings and intercepts are constrained to be equal between time points) invariance using MLR and FIML estimators (see Chapter 2 and Table S2 in supplemental material).

After the structural validity was shown to be sufficient in terms of CFA and measurement invariance model fit indices, a latent profile analysis was conducted with Mplus version 8.7 to study the individual variation in teachers’ perceptions and development of professional agency in the classroom over a two-year period (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2010). The mean variables of the two professional agency subscales at all three time points were used as latent class indicators. Altogether seven class solutions were estimated, and the most suitable solution was chosen using the following criteria: finding the lowest values for Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted BIC (aBIC) indices, and statistically significant p-value for the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood Ratio Test (VLMR), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted LRT (aLRT), and the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) (Berlin et al., Citation2014; Morin et al., Citation2016; Nylund et al., Citation2007), as well as the entropy value (the general accuracy of the profiles) and latent class probability values (the accuracy of the classification for each profile separately) close or above .80 (Clark & Muthén, Citation2009).

After the most suitable latent profile solution was identified, the mean differences between and within the profiles were examined with a model constraint test. Lastly, we analysed how the covariates (burnout symptoms and proactive strategies) at the third time of measurement and background variables (gender and work experience) differed between the profiles. The BCH comparison was chosen for the covariate analysis because it allows examination of the relationships between profiles and continuous distal outcomes (in this study, socio-contextual burnout and proactive strategies) across latent profiles. The R3STEP procedure was chosen for analysing the differences in background variables (gender and work experience) between the profiles. It utilizes a multinomial logistic regression and gives the odds ratios that describe the effect of the background variables on the likelihood of membership in each of the latent profiles compared with other profiles (Asparouhov & Muthen, Citation2014).

3. Results

3.1. Profiles of teacher’s professional agency in the classroom

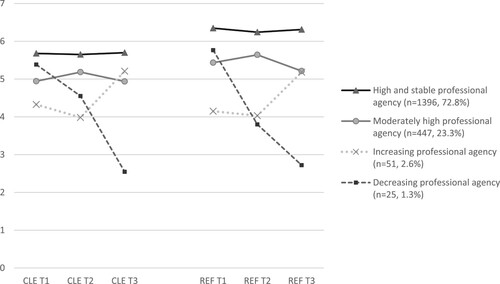

Four profiles of TPA in the classroom were identified: (1) High and stable professional agency; (2) Moderately high professional agency; (3) Increasing professional agency; and (4) Decreasing professional agency (). The fourth profile solution was chosen based on Morin and colleagues’ (Citation2016) information criteria and elbow plots (see Table S3 in supplemental material). Most of the primary school teachers had either a high and stable professional agency profile (72.8%) or a moderately high professional agency profile (23.3%). This indicates that most of the teachers believed they wanted, could, and had, the skills to learn actively in the classroom and develop as teachers. The other two profiles were considerably less prevalent: increasing professional agency (2.6%), and decreasing professional agency (1.3%). Those with the former profile experienced that their abilities to learn and develop as teachers strengthened during the two-year follow-up, while the latter experienced that their capacity to develop as teachers diminished over time.

The results show that both modes of professional agency in the classroom, collaborative environment and transformative practice (CLE) and reflection in the classroom (REF), are very similar in level and shape in all four profiles. In other words, a teacher who makes efforts to constantly learn and develop the classroom in collaboration with the students is likely to reflect on and evaluate teaching situations and also him- or herself as a teacher. Moreover, when a teacher experiences diminishing skills, motivation and efficacy in revising their pedagogical practices, the tendency to reflect on and assess these practices is also likely to decrease.

The results concerning mean differences within and between the profiles showed that there were only few significant changes in the level of the High and stable professional agency profile over time (see ). This group of teachers experienced strong professional agency that remained relatively stable over time (mean variation over the two-year period: CLE: 5.65–5.70 and REF: 6.24–6.35). There was only a small significant decrease in perceived sense of reflection in the classroom at T2.

Table 1. Differences in mean values of indicator variables within and between the profiles.

Teachers who belonged to the Moderately high professional agency profile also experienced relatively strong professional agency over time (mean variation: CLE: 4.94–5.12 and REF: 5.21–5.64). However, in this group teachers experienced a statistically significant rise in sense of professional agency in both modes of learning (CLE and REF) from T1 to T2 and then a slight drop by T3. Teachers in the Increasing professional agency profile experienced moderate professional agency at the first two measurement times, which then increased statistically significantly at the third time of measurement (mean variation: CLE: 3.98–5.21 and REF: 4.03–5.18). Teachers in the Decreasing professional agency profile perceived high professional agency at first, which then decreased significantly throughout the whole follow-up study (mean variation: CLE: 2.54–5.38 and REF: 2.72–5.77). Finally, all four profiles differed statistically significantly from each other in sense of professional agency at most of the time points (). The results supported the H1.

3.2. Differences in perceived socio-contextual burnout symptoms and proactive strategies

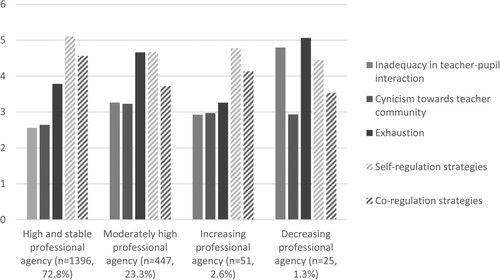

The further investigation showed that the professional agency in the classroom profiles differed from each other also in terms of perceived burnout symptoms and abilities to use proactive strategies at time point 3 (see and ). Teachers who belonged to the Moderately high professional agency profile were more likely to experience higher levels of all three burnout symptoms; cynicism, inadequacy, and exhaustion, than teachers who belonged to the High and stable professional agency profile. However, perceived cynicism towards the teacher community did not differentiate the profiles.

Figure 2. Burnout symptoms and proactive strategies in the professional agency in the classroom profiles.

Table 2. Differences in mean values of outcomes between the profiles.

Sense of inadequacy in teacher-student interaction differentiated the profiles the most. Teachers who experienced more inadequacy and failure in teacher-student interaction were more likely to belong to the Decreasing professional agency profile than to any other profile. Correspondingly, teachers who experienced the lowest level of inadequacy in teacher–student interaction were most likely to belong to the High and stable professional agency profile. However, feelings of inadequacy did not seem to affect whether the teacher belonged to the Increasing professional agency profile or to the High and stable or Moderately high professional agency profiles. Moreover, teachers who experienced more exhaustion were more likely to have a decreasing or moderately high professional agency profile than an increasing professional agency profile.

Additionally, perceived proactive strategies, i.e. how teachers experienced their abilities to use self-regulative and co-regulative strategies, differentiated some of the professional agency profiles. Teachers who reported using more self-regulation and co-regulation belonged more likely to the High and stable professional agency profile than the Moderately high professional agency profile. Otherwise, the perceived use of self-regulation strategies did not differentiate any other professional agency profiles. Finally, teachers in the High and stable professional agency profile were more likely to report higher use of co-regulation strategies than teachers in the Decreasing professional agency profile. Accordingly, H2 and H3 were supported.

3.3. Differences in gender and work experience

The 3-step analysis showed some differences in gender and work experience among the four profiles. Both background variables differentiated the two biggest profiles, High and stable professional agency and Moderately high professional agency. Female primary school teachers were more likely to belong to the High and stable professional agency profile than the Moderately high professional agency profile (b = −1.03, SE = .24, p = .000; OR = .36, 95% CI .23–.57). In addition, primary school teachers who had less work experience had higher odds of belonging to the High and stable professional agency profile than the Moderately high professional agency profile (b = −0.02, SE = .01, p = .052; OR = .98, 95% CI .96–1.00). However, the latter result shows only a small difference and the result is only nearly statistically significant.

3.4. Summary of results

We found four profiles of teacher’s professional agency among Finnish primary school teachers: (1) High and stable professional agency, (2) Moderately high professional agency, (3) Increasing professional agency, and (4) Decreasing professional agency. Most teachers belonged to the first two profiles and experienced strong and stable professional agency over time. Only a few teachers experienced changes in professional agency and belonged to the third and fourth profile.

The profiles differed in terms of experienced burnout symptoms, proactive strategy use, gender, and work experience. The primary school teachers in the High and stable professional agency profile experienced lowest levels of burnout symptoms and highest abilities to use proactive strategies to prevent burnout. Female and less experienced primary school teachers had higher odds of belonging to the High and stable professional agency profile than the Moderately high professional agency profile.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in light of previous research

The results showed that the Finnish primary school teachers typically had a strong sense of professional agency in the classroom, comprised of teacher motivation, self-efficacy, and strategies for learning, realized in the classroom as the teacher’s efforts to learn actively and skilfully by reflecting and constructing learning environments together with students. The professional agency employed by the teachers also remained relatively stable over time, supporting the H1, and our previous results (Heikonen et al., Citation2020; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). The results suggest that, in general, teachers perceive learning as an important part of their work in the classroom. However, variation between the teachers was also detected: in addition to the high and moderately high professional agency profiles, some teachers had either increasing or decreasing professional agency profiles. Such developments are likely to result from changes in teacher–working environment dynamics that can either cultivate or hinder their agency in the classroom (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Priestley et al., Citation2015), such as the changes resulting from an intensive period of developing and implementing a new curriculum. Moreover, this result is in line with the previous research showing that teachers’ professional development can include ups and downs rather than being a steady rise (Dall’Alba & Sandberg, Citation2006; Vermunt & Endedijk, Citation2011). In addition, it offers new insight to the teacher’s professional development literature by introducing Finnish primary school teachers’ developmental patterns of professional agency in the classroom.

The profiles differed from each other in terms of experienced burnout symptoms and reported use of self- and co-regulation strategies, as expected in our second and third hypotheses. Teachers’ experiences of inadequacy in teacher-student interaction and co-regulation strategy use differentiated the profiles the most. This result supports our previous findings regarding the intertwining of teacher learning, agency and well-being in the classroom and teacher-student interaction (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Soini et al., Citation2010; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). The teachers with high and stable professional agency profiles reported using more proactive strategies, especially co-regulation. They also reported lower levels of all three burnout symptoms: inadequacy in teacher–student interaction, cynicism towards the teacher community, and exhaustion. In contrast, teachers with a Moderately high professional agency profile experienced the highest levels of cynicism towards the teacher community. These findings indicate that even small differences or changes in teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom can significantly increase or reduce their risk of socio-contextual burnout and, even further, their ability to use proactive strategies. In other words, teachers with moderately high professional agency profiles may have an increased risk of burnout. It is important to identify these risk factors of burnout as, according to recent studies, up to half of teachers are at risk of developing burnout (Pyhältö et al., Citation2021).

In addition, the profiles differed in terms of gender and work experience. It seems that female and less experienced primary school teachers are more likely to have a High and stable professional agency profile than a Moderately high professional agency profile. These are novel observations regarding research on TPA. Female teachers have been shown to experience higher emotional and quantitative work demands and feel less able to limit their engagement in work and responsibilities towards students and colleagues than male teachers (Stengård et al., Citation2022), which might explain why female teachers report higher scores when assessing their sense of professional agency. Furthermore, there are two possible directions for interpreting the result that inexperienced teachers have higher odds of having a High and stable professional agency profile. On the one hand, early career teachers have been shown to occasionally overestimate their abilities as teachers (Mortensen et al., Citation2008), and on the other, experienced teachers have been shown to be more cynical towards their own work (Byrne, Citation1991). These might affect how teachers in different phases of their career experience their sense of professional agency.

The identified profiles representing the developmental patterns of TPA may explain some of our previous conflicting results of the interrelation between TPA and teacher burnout suggesting that a teacher's high tendency to reflect may even increase feelings of inadequacy and cynicism in some cases (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). These variable-centred studies were unable to take into account the heterogeneity of the research samples, which is possible in person-centred approaches.

Our results also contributed to new understanding on the relation between proactive strategies and professional agency in the classroom. Teachers with a high and stable professional agency profile reported more systematic use of self- and, particularly, co-regulative strategies to prevent burnout in their work, compared to teachers with other profiles. However, the differences were less pronounced compared to those with burnout symptoms. The results nevertheless supported the hypotheses and imply that teachers’ ability to prevent burnout in advance strengthens their professional agency not only in the teacher community but also in teacher-student interaction in the classroom (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015).

4.2. Practical implications

The present study indicates that most Finnish primary school teachers experience strong professional agency. They have the skills, motivation and efficacy to constantly learn and develop at work by reflecting and constructing learning environments together with students. They also experience only moderate levels of burnout symptoms and have good abilities to regulate their well-being and coping at work.

However, it is important to consider that even a small drop in a teacher’s sense of professional agency in the classroom may indicate that the teacher is experiencing higher levels of inadequacy, exhaustion and cynicism, and, consequently, less consistently uses self- and co-regulative strategies to buffer stressful transactions. In addition, Finnish teachers tend to give only the highest positive scores when asked to rate their abilities, motivation and self-efficacy as teachers (e.g. Soini et al., Citation2016; Yli-Pietilä et al., Citation2022). This implies that further studies on teachers with a moderately high professional agency profile and the differences in their experiences compared to teachers with a high and stable professional agency profile are needed in order to develop sufficient means to support TPA development in teacher education and in schools.

Moreover, the novel results on the relations between teachers’ professional agency profiles and reported use of self- and co-regulation strategies imply that cultivating the use of proactive strategies, especially when confronting changes and new challenges, might be a good investment in terms of both teacher learning and well-being. The good news is that teachers can choose which proactive strategies to use and how, and they can always learn new kinds of strategies. Here, the shared practices of the working community play an important role in how teachers use and learn these strategies (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013; Saariaho, Citation2020; Tikkanen et al., Citation2017; Väisänen et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). From this perspective, it is crucial that the whole working community collectively adopts such strategies and employs them as part of their everyday practices.

In line with prior studies, our results suggest that it would be beneficial to practice and utilize proactive strategies during teacher education (Saariaho, Citation2020; Väisänen et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). It is also essential to focus not only on self-regulation but also co-regulation strategies. This could take place through mentoring early career primary school teachers as well as creating more opportunities to utilize co-teaching among primary school teachers.

4.3. Methodological reflection

This study has limitations that must be considered thoroughly. Firstly, the study is based on the self-reports of the teachers. In future, for example, the views of students and principals on teacher’s professional agency could provide an interesting new perspective on the research of TPA. However, the confirmatory factor analysis and the measurement invariance test showed good construct validity for the scales used in this study and the sample size was large (Byrne & Stewart, Citation2006; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Secondly, although all of the teachers were teaching in primary schools, and most of them had primary school teacher education, the sample may have included some teachers who work or are qualified as subject teachers or special education teachers. Nevertheless, the results provide a broad picture of teachers working in primary schools, and the sample of the teachers represented well the variety of schools in Finland and the distributions of gender and work among Finnish teachers. Thirdly, we combined the longitudinal and person-centred analysis by carrying out a longitudinal latent profile analysis, which can be considered a relatively new way to apply structural equation modelling, and thus it is important to continue testing the method. Fourthly, the four-class solution of the longitudinal latent profile analysis was chosen as the best model based on the information criteria and elbow plots (Morin et al., Citation2016) and to reach more fine-graded information on individual variation in terms of TPA and its development, even though it included two small profiles of less than 5% (see Marsh et al., Citation2009). It has been suggested that profiles under 1% or including fewer than 25 cases should be omitted (Lubke & Neale, Citation2010; Spurk et al., Citation2020). The present study includes profiles of 1.3% (25 cases) and 2.6% (51 cases). Thus, based on the literature, 1% to 5% profiles are possible in studies that have large sample sizes. Although the third and fourth profiles were small, examination of the missing data showed that the profiles were mostly based on non-missing values of indicator variables. In addition, the examined covariates differentiated all of the four profiles well and thus also validated them. The findings of the two small profiles raised an important phenomenon, that some teachers experience ascents and descents in their sense of TPA over time. In future, a qualitative study of teachers experiencing professional agency changes would enable deeper examination of the underlying causes and circumstances behind different developmental patterns of TPA. In addition, it is important to note that this study examined the development of TPA over a two-year period. In future studies, therefore, it would also be important to examine the development of TPA over a longer time period.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.4 KB)Acknowledgements

MA Kaisa Haverinen has contributed to the longitudinal latent profile analysis in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akiba, M., Murata, A., Howard, C., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Lesson study design features for supporting collaborative teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.012

- Aloe, A., Amo, L., & Shanahan, M. (2014). Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multivariate meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 26(1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0

- Asparouhov, T. (2005). Sampling weights in latent variable modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(3), 411–434. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1203_4

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Bergman, L. R., & Magnusson, D. (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 9(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457949700206X

- Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A., & Parra, G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

- Brewer, E. W., & Shapard, L. (2004). Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335

- Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

- Bruce, C., Esmonde, I., Ross, J., Dookie, L., & Beatty, R. (2010). The effects of sustained classroom-embedded teacher professional learning on teacher efficacy and related student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(8), 1598–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.011

- Byrne, B. M. (1991). Burnout: Investigating the impact of background variables for elementary, intermediate, secondary, and university educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 7(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(91)90027-M

- Byrne, B. M., & Stewart, S. M. (2006). The MACS approach to testing for multigroup invariance of a second-order structure: A walk through the process. Structural Equation Modeling, 13(2), 287–321. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_7

- Cano-Garcia, F. J., Padilla-Muñoz, E. M., & Carrasco-Ortiz, M. A. (2005). Personality and contextual variables in teacher burnout. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(4), 929–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.018

- Clark, S. L., & Muthén, B. (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Semantic Scholar. https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf

- Dall’Alba, G., & Sandberg, J. (2006). Unveiling professional growth: A critical review of stage models. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 383–412. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076003383

- Desrumaux, P., Lapointe, D., Ntsame Sima, M., Boudrais, J. S., Savoie, A., & Brunet, L. (2015). The impact of work demands, climate, and optimism on wellbeing and distress at work: What are the mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction? Revue Européenne de Spychologie Appliquée, 65(4), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2015.06.003

- Dorman, J. P. (2003). Relationship between school and classroom environment and teacher burnout: A LISREL analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 6(2), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023296126723

- Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Vanroelen, C. (2014). Burnout among senior teachers: Investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.005

- Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.010

- Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2003). Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(6), 444–451. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40967322 https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.752

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

- Finnish Advisory Board for Research Integrity. (2009). Ethical principles of research in the humanities and social and behavioural sciences and proposals for ethical review. https://www.tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/ethicalprinciples.pdf

- Foley, C., & Murphy, M. (2015). Burnout in Irish teachers: Investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.001

- Gavish, B., & Friedman, I. A. (2010). Novice teachers’ experience of teaching: A dynamic aspect of burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 13(2), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-009-9108-0

- Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2017). Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1169505

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2020). The development of student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom during teacher education. Learning: Research and Practice, 11(7), 324. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2020.1725603

- Hoekstra, A., Beijaard, D., Brekelmans, M., & Korthagen, F. (2007). Experienced teachers’ informal learning from classroom teaching. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600601152546

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315650982

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ketelaar, E., Beijaard, D., Boshuizen, H. P. A., & Den Brok, P. J. (2012). Teachers’ positioning towards an educational innovation in the light of ownership, sense-making and agency. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(2), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.004

- Klassen, R. M., & Durksen, T. L. (2014). Weekly self-efficacy and work stress during the teaching practicum: A mixed methods study. Learning and Instruction, 33, 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.05.003

- Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016). Teachers’ everyday professional development: Mapping informal learning activities, antecedents, and learning outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111–1150. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315627864

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Resolving feelings of professional inadequacy: Student teachers’ coping with distressful situations. Teaching & Teacher Education, 64, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019

- Lubke, G., & Neale, M. C. (2010). Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors: Resolution by maximum likelihood? Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41(4), 499–532. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4104_4

- Mälkki, K. (2019). Coming to grips with edge-emotions. The gateway to critical reflection and transformative learning. In T. Fleming, A. Kokkos, & F. Finnegan (Eds.), European perspectives on transformative learning (pp. 59–73). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Morin, J. S. A. (2009). Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: Synergy of person- and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(2), 191–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510902751010

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

- Meirink, J. A., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2007). A closer look at teachers’ individual learning in collaborative settings. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600601152496

- Morin, A. J. S., Meyer, J. P., Creusier, J., & Biétry, F. (2016). Multiple-group analysis of similarity in latent profile solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115621148

- Mortenson, B. P., Rush, K. S., Webster, J., & Beck, T. (2008). Early career teachers accuracy in predicting behavioral functioning: A pilot study of teacher skills. International Journal of Behavioral and Consultation Therapy, 4(4), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100861

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2010). Mplus users guide. Muthén & Muthén.

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Oliveira, S., Roberto, M. S., & Veiga-Simão, A. M. (2021). A meta-analysis of the impact of social and emotional learning interventions on teachers’ burnout symptoms. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1779–1808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09612-x

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., & Soini, T. (2016). Teacher’s professional agency – A relational approach to teacher learning. Learning: Research and Practice, 2(2), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2016.1181196

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., & Soini, T. (2017). Shared sense-making in curriculum reform – Orchestrating the local curriculum work. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1402367

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., Haverinen, K., & Leskinen, E. (2021). Is individual- and school-level teacher burnout reduced by proactive strategies? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 9(4), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2021.1942344

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013a). Validity and reliability of the socio-contextual teacher burnout inventory (STBI). Psychology, 4(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.41010

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013b). Reducing teacher burnout: A socio-contextual approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.003

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G. J. J., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., Haverinen, K., Tikkanen, L., & Soini, T. (2021). Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36(1), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00465-6

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Teacher–working-environment fit as a framework for burnout experienced by Finnish teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(7), 1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.006

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Comprehensive school teachers’ professional agency in large-scale educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 15(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9215-8

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency and learning – From adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers & Teaching, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2012). Do comprehensive school teachers perceive themselves as active professional agents in school reforms? Journal of Educational Change, 13(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9171-0

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2016). Facilitating and hindering motivation, learning, and well-being in schools. In K. R. Wentzel, & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 96–119). Routledge.

- Saariaho, E. (2020). Exploring active and skilful student teacher learning: Self-regulated and co-regulated learning in primary teacher education. Helsinki Studies in Education, 91. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Educational Sciences.

- Sachs, J. (2000). The activist professional. Journal of Educational Change, 1(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010092014264

- Sahlberg, P. (2017). Finnish lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(2), 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2017.1312818

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147

- Schwarzer, R., & Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Applied Psychology, 57(s1), 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher Development, 20(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2021). Shared sense-making, agency, and learning in school development in Finnish school reforms. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1659

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., & Pyhältö, K. (2015). What contributes to first year student teacher’s sense of professional agency in the classroom? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044326

- Soini, T., Pyhältö, K., & Pietarinen, J. (2010). Pedagogical well-being: Reflecting learning and well-being in teachers’ work. Teachers and Teaching, 16(6), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517690

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445

- Stengård, J., Mellner, C., Toivanen, S., &, Nyberg, A. (2022). Gender differences in the work and home spheres for teachers, and longitudinal associations with depressive symptoms in a Swedish cohort. Sex Roles, 86(3-4), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01261-2

- Straud, C., McNaughton-Cassill, M., & Fuhrman, R. (2015). The role of the Five Factor Model of personality with proactive coping and preventive coping among college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.055

- Sullanmaa, J., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2021). Relationships between change management, knowledge sharing, curriculum coherence and school impact in national curriculum reform: A longitudinal approach. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1972165

- Sullanmaa, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2019). Trajectories of teachers’ perceived curriculum coherence in the context of Finnish core curriculum reform. Curriculum and Teaching, 34(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.7459/ct/34.2.03

- Tikkanen, L., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2017). Interrelations between principals’ risk of burnout profiles and proactive self-regulation strategies. Journal of Social Psychology of Education, 20(2), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9379-9

- Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., & O’Connell Rust, F. (2015). Teacher’s professional agency in contradictory times. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044334

- Turnbull, M. (2005). Student teacher professional agency in the practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500122116

- Väisänen, S., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2018a). Student teachers’ proactive strategies for avoiding study-related burnout during teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1448777

- Väisänen, S., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2018b). Student teachers’ proactive strategies and experienced learning environment for reducing study-related burnout. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(1), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n1p208

- Vermunt, J., & Endedijk, M. (2011). Patterns in teacher learning in different phases of the professional career. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.019

- Yli-Pietilä, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2022). Primary school teachers’ sense of professional agency and inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. [Unpublished manuscript]. Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University.

- Zeng, G., Chen, X., Cheung, H. Y., & Peng, K. (2019). Teachers’ growth mindset and work engagement in the Chinese educational context: Well-being and perseverance of effort as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(839), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00839