ABSTRACT

This article is a response to Backman and Barker’s Re-thinking Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Physical Education Teachers-Implications for Physical Education Teacher Education. It affords us an opportunity to correct their misrepresentation of our research. Multiple perspectives on teaching and teacher education are necessary to advance the field because they provide different lenses to help us understand a particular phenomenon. However, there is a critical difference between interpretation and misrepresentation. Interpretation is the right due to all researchers to draw inferences. Misrepresentation, in contrast, is the attributing of positions and outcomes that are not supported by the empirical record. In making their case for phronesis in a 2020 publication, Backman and Barker used our research as the basis for their critique and in doing so, they misrepresented our body of research as well as the epistemology of Radical Behaviorism. We identify misrepresentations in their paper and address them using the empirical record.

In their article Re-thinking pedagogical content knowledge for physical education teachers-implications for physical education teacher education, Backman and Barker (Citation2020) propose a new perspective in the consideration of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) in physical education. A perspective grounded in phronesis. We, like they, agree that multiple perspectives on teaching are both good and necessary. Multiple perspectives provide different lenses that help us understand a particular phenomenon. As Backman and Barker (Citation2020) noted, different perspectives serve to “broaden teachers’ and teacher educators’ views of competent teaching in physical education” (p. 452). Multiple perspectives are also good because they raise the issue of philosophic doubt which is a cornerstone of good science requiring practitioners to question both the purposes and the research findings from a particular lens (Cooper et al., Citation2020).

However, in making their case for phronesis, Backman and Barker (Citation2020) used our research as the basis for their critique and in doing so they misrepresented it. This was not an interpretive difference as one might expect if an epistemology or a method was critiqued directly, but our findings and conceptual positions were misrepresented, and this misrepresentation then served as the basis for Backman and Barker (Citation2020) critique. In short, the authors attributed positions to us we do not support or are more nuanced in our support. They used selective and incomplete statements of ours to base their arguments, ignoring both the details and nuance discussed in our articles. In this paper, we respond specifically to areas of misrepresentation of our research and the epistemology of Radical Behaviorism (Skinner, Citation1974). We do not object to Backman and Barker (Citation2020) proposal that PCK research in physical education could benefit from more epistemological perspectives. We welcome different perspectives and the discussions they evoke in the field, and we strongly support the right of researchers to state different perspectives. We also support critiques of our conceptual positions and methods; however, we object to the misrepresentation of our work.

Responses to Backman and Barker (Citation2020)

We have organized our responses relative to misrepresentations made by Backman and Barker (Citation2020) for the most part as they first appeared in the chapter. As a matter of form, we have used “we” to report our responses because Backman and Barker’s critique is specifically about our work. Backman and Barker (Citation2020) wrote:

From our perspective as socially critical constructivist researchers we believe that by only adopting a behavioral perspective of CK, i.e., a perspective which aims to change students’ behaviors without necessarily changing knowledge or practices, pre-service teachers are unlikely to reflect on context and culture or how these affect the students with whom they will work. (p. 452)

By arguing that reflection, decision-making, and adaptation to teaching do not occur in our work, Backman and Barker (Citation2020) demonstrate a lack of understanding of our conceptualization of PCK and content knowledge, the epistemology of behavior analysis, and the empirical evidence reported in our research. All of which lead to misrepresentation of our work in their paper.

Conceptual understandings of PCK and content knowledge

Our conceptual formalizations are informed by the task systems orientation of Doyle (Citation1986), the PCK knowledge bases proposed by Shulman (Citation1987) and the epistemology of behavior analysis (Cooper et al., Citation2020). Doyle (Citation1986) in education and Hastie and Siedentop (Citation2006) in physical education, have argued that tasks are the mechanism by which a curriculum is enacted. Tasks define how students come to understand the meaning of the content teachers emphasize. A teacher’s understanding of the content that they teach is fundamental to notions of quality teaching (Ward, Citation2013; Ward et al., Citation2020). It is this understanding that affects the decisions teachers make as they design, implement, and modify instruction (Rovegno, Citation1995). Shulman (Citation1987) described PCK as “an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organized, presented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented for instruction” (p. 8). A teacher’s ability to adapt instruction to the individual learner’s needs is a characteristic of PCK. This can be seen in the way content is presented to students as a task and differentiated according to a student’s performance.

Our conceptualization of PCK derives from joining the work of Shulman (Citation1987) and Doyle (Citation1986) with behavior analysis (Cooper et al., Citation2020) leading to the following definition. PCK is:

A focal point, a locus, defined as an event in time (and therefore contextually specific) where teachers make decisions in terms of content based on their understandings of a number of knowledge bases (e.g., pedagogy, learning, motor development, students, contexts, and curriculum). (Ward, Kim et al., Citation2015, p. 2)

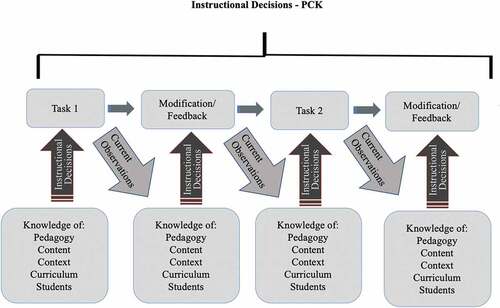

Each decision teachers make in their teaching involves applying their prior knowledge (e.g., knowledge of the student, pedagogy, content) and is influenced by the lesson’s current context (e.g., equipment, space, and student performances) so that the next decision is potentially informed by the previous decision, and all such decisions are influenced by teachers’ perceptions of student learning in variable school environments. provides a graphic representation of the operationalization of PCK within a lesson. In this depiction, PCK is a dynamic phenomenon influenced by students and pedagogical environments. Iserbyt et al. (Citation2020) summarized this perspective as follows:

Central to Ward, Kim et al.’s (Citation2015) definition is the assumption that PCK changes moment to moment as the teacher encounters student performance of instructional tasks or engages in reflection and planning their future lessons. Adaptation to the instructional conditions is the key contextual variable that demonstrates that teaching is a decision-oriented profession rather than a prescriptive one. (p. 539)

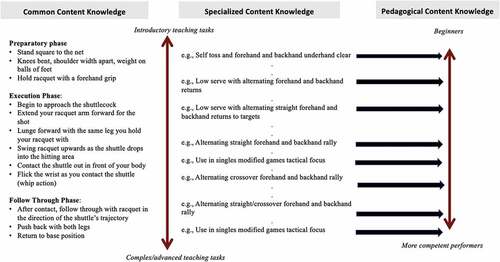

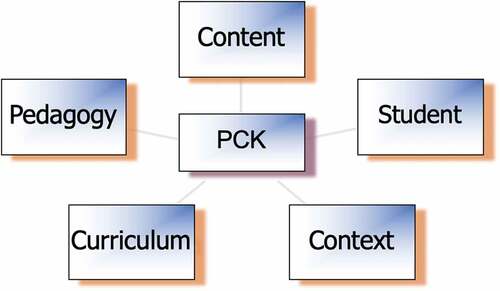

As Ward, Kim et al. (Citation2015) noted, content knowledge is but one component of PCK (See ). Different researchers argue for different knowledge bases as influences on PCK, but common to all conceptions of PCK are the knowledge bases of content and pedagogy (Ward & Ayvazo, Citation2016). Our work has specifically focused on the contribution of content knowledge to PCK relative to addressing student needs with the goal of improving student learning.

Figure 2. Major knowledge bases influencing PCK (Ward and Ayvazo, Citation2016).

Drawing on the work of Ball et al. (Citation2008) in classroom research we have conceptualized content knowledge as occurring in two domains: common content knowledge (CCK) which is the knowledge of how to perform movements and includes knowledge of etiquette, rules, techniques, and where relevant tactics and game sense; and specialized content knowledge (SCK), which includes knowledge of how to present tasks to students in understandable ways, instructional tasks, and performance errors (Kim et al., Citation2018; Ward & Ayvazo, Citation2016; Ward et al., Citation2020). illustrates the relationship among CCK, SCK and PCK. In the first column CCK may change slightly according to the different tasks, though typically remains similar across instructional tasks that develop a movement (e.g., the sit-up or the forearm pass in volleyball or downward-facing dog in yoga). The second column is SCK, which describes the instructional tasks that a teacher knows to inform their instruction. But it is only when a teacher draws on that knowledge to address particular pedagogy, curriculum contexts, and students that it is used. For example, in teaching the handstand, the teacher may determine that walking the feet up the wall from a push-up position is an appropriate next step for the student who needs support (i.e., knowledge of the student). However, the teacher may be teaching outdoors without any walls to use and thus that task will need to be replaced.

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) stated that, “It [SCK] is also different from PCK in the sense that the context is assumed to be neutral (i.e., the knowledge is the same regardless of the pupils’ characteristics)” (p. 455). This is inaccurate. SCK is one of the content knowledge domains (see , column 2). It is also a component of PCK (see , column 3) when the teacher makes an instructional decision relative to addressing the needs of a student or students. As such, it is student and setting specific (see , column 3). Backman and Barker (Citation2020) are correct when they claim that SCK is neutral (i.e., as a domain of content knowledge in , column 2). But they are wrong that it is neutral because as a component of PCK, it is selected to meet specific student needs along with other elements of PCK (e.g., pedagogy)

Behavioral perspectives on PCK

Behavior analysts find evidence of reflection and decision-making through teacher talk (e.g., discussions or answers to questions), writing (e.g., lesson plans, journaling or other reflective practices), or in the act of teaching. These are common strategies to examine teaching behaviors such as decision-making and reflection used by most researchers who study in teaching and teaching education, regardless of their epistemology. Behavior analysis considers that individuals are unique with their own genetic and learning histories that are different from one another, because they were and are shaped by their environments. Thus, behavior analysis is not a one size fits all epistemology, but one that focuses on the individual as the unit of analysis. It is an epistemology that considers the learning history of the individual (e.g., prior knowledge) and their current environment (e.g., student performance).

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) in writing about the concept of phronesis state that: “This concept can, we believe, complement the behavior analytic discussion of PCK in physical education and PETE and provide some sense of the subjective, ethical and moral dimensions of teaching” (p. 457). The issue here is that Backman and Barker (Citation2020) imply in their paper that we do not value the subjective, ethical, and moral dimensions of teaching. The empirical evidence of our valuing the subjective, ethical, and moral dimensions of teaching can be found in Ward (Citation2014, Citation2016). The practical evidence is that the authors of this paper are teachers and teacher educators who are committed to subjective, ethical, and moral dimensions of teaching in our practice.

We understand that Backman and Barker are socially critical constructivist researchers. Their theoretical orientation structures a contrasting view of science and perhaps teaching, learning, and schooling to the one we hold. We have proceeded with due recognition of the inherent selectivity in our questions, research designs, findings, and interpretations. The same selectivity is apparent in our recommendations for policy, teacher education, and school-level practice.

We especially appreciate how and why differences in paradigms and exemplars (e.g., Kuhn, Citation1962) give rise to learning-rich interchanges among scholars with different affiliations. However, it is important that scholars avoid creating artificial divides founded on assumptions regarding privileged standpoints and superior research agendas. Multiple perspectives create depth in analysis and that multiple perspectives mean that we all have a piece of the puzzle (Lawson, Citation2009).

Not all studies can examine all the pieces of the puzzle. The reminder here is that selectivity encourages specialization, and specialization gives rise to lines of research with studies that are additive and integrative. Our line of research follows suit. While our work provides what we believe is the largest data sets in our field, our work addresses only the following questions: What are the knowledge levels of pre-service teachers and practicing teachers?; Can we improve knowledge levels in teacher education and professional development?; In what ways in teacher education and professional development we can help teachers acquire improved knowledge leading to better decision-making?; What are the effects of this improved knowledge on teaching and in particular, on student learning?

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) commented with regard to behavior analysis:

From our perspective, physical education teachers’ interpretations of their students seem to play a marginal role in the behavior analytic research about PCK … As we understand it, the behavior analytic approach pays little heed to the adjustment’s teachers must make in response to students’ actions in situ. (p. 459)

We hope that in the previous few paragraphs, we have pointed to the erroneousness of this view. But by the persistent reference to this in their paper, it is clear that Backman and Barker incorrectly attribute characteristics to our research and to the behavior analytic approach that are not accurate. For example, in their intervention study on PCK, Sinelnikov et al. (Citation2016) noted: “Participant teachers were free to develop their own plan and also to respond to students needs in the lesson as they arose” (p. 13). Similarly, Ward, Chen, et al. (Citation2018) reported: “Adjusting lesson plans and lessons from one occasion to another is evidence of reflective learning” (p. 22). Ward and Ayvazo (Citation2016) reported that “Knowing the context characteristics of their students helps teachers tailor instruction for individuals” (p. 200). Collectively, these quotes together with our earlier discussion of the conceptual roots of our research, provide evidence that directly contradicts Backman and Barker (Citation2020) claim that “Physical education teachers’ interpretations of their students seem to play a marginal role in the behavior analytic research about PCK” (p. 459).

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) also observed:

However, most of the current behavior analytic research of CK and PCK does not consider movement as means for learning (i.e., that through wrestling we might learn about content such as sport history or perhaps gender roles in sports), but primarily as an object for learning in itself (i.e., that by doing wrestling we can learn in and about wrestling), which in turn limits the conceptualization of content knowledge in physical education and PETE. (p. 456)

We agree wholeheartedly. We have not focused on other dimensions of content. There is not enough research on PCK in physical education and not just in terms of learning through movement, but also in other content areas that have not been examined and in terms of intersections and integration of health and physical education. We welcome such research efforts.

Empirical evidence demonstrating our conceptualization of content knowledge and PCK

Prospective teachers do not arrive in PETE programs ready-made or understanding teaching practice or the knowledge bases that inform teachers very well. A key part of the obligation of PETE programs is to focus on what works and the pedagogies of how to teach what works. Our research both focuses on and provides evidence of changes in knowledge and practice of teachers (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2020; Iserbyt et al., Citation2016; Iserbyt, Theys et al., Citation2017; Iserbyt, Ward et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2018). Changes in teacher knowledge and practice are mediated by the context which for the most part, involves knowledge of learner’s abilities and current performance and the resources (e.g., equipment and characteristics of the setting, space, safety considerations) in which students are performing.

Our early work on measuring CCK was predictably exploratory. We relied on content validity from teachers and content experts. Since then, our validity measures have been informed by a priority for construct validity. Our studies have occurred in six countries, with different authors and research teams, studying 8874 pre-service teachers and 877 practicing teachers (e.g., Dervent, Devrilmez et al., Citation2018; Dervent et al., Citation2020; Dervent, Ward et al., Citation2018; Devrilmez et al., Citation2019; He et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2018; Tsuda, Ward, Li et al., Citation2019).

Similarly, SCK has been validated using concurrent validity in a similar number of countries and has been assessed with 5137 pre-service teachers and 1027 practicing teachers (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2020; Dervent et al., Citation2020; Ward, He, et al., Citation2018). These CCK and SCK assessments using different measures of a variety of content in diverse cultural, linguistic, and educational systems have revealed similar findings (e.g., Dervent et al., Citation2020; Dervent, Devrilmez et al., Citation2018; He et al., Citation2018; Iserbyt, Ward et al., Citation2017; Stefanou et al., Citation2020; Tsuda, Ward, Yoshino et al., Citation2019; Ward, He et al., Citation2018). This research led us to conclude that the challenges of CCK and SCK are commonly faced worldwide by teacher education and by teachers.

PCK has been measured by focusing specifically on what is the enacted task students are asked to do drawing, as we noted earlier, on the work of Doyle (Citation1986). The validity of these measures has been verified through interobserver agreement and measures of internal validity. The studies have measured a variety of content from elementary to secondary school, in four different countries that varied in terms of cultural, linguistic, and educational systems, with both classroom and physical education teachers. As we reported earlier, our PCK data include 98 teachers and 2101 students (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2020; Kim & Ko, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2018; Stefanou et al., Citation2020). The studies have consistently reported changes in the decisions that teachers made in adapting and tinkering with instructional tasks. The teachers in these studies have ranged from first year beginning teachers to 15 to 20-year veteran teachers considered competent, and in some cases, highly competent by their principals, peers, and university faculty.

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) did not discuss these PCK studies demonstrating the effects of improved teacher decision–making on student learning. Student learning has been demonstrated in daily changes in behavior for the full duration of instructional units (e.g., Kim & Ko, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2018) and by pre-post control group studies with effect sizes exceeding 1.0 (Iserbyt, Ward et al., Citation2017; Stefanou et al., Citation2020). To illustrate the significance of these effects, Kim et al.’s (Citation2018) meta-analysis reported: “To place this in perspective, if these were standardized assessments rather than unstandardized, the results with an ES of 1.0 would increase percentile scores from 50 to 84” (p. 9).

Our studies have demonstrated changes in teacher knowledge using pre-post and control group experimental and cross-sectional research designs examining CCK and SCK of pre-service and practicing teachers (e.g., Stefanou et al., Citation2020; Tsuda, Ward, Li et al., Citation2019; Ward, Tsuda et al., Citation2018). These studies have been conducted with just over 16,000 pre-service and in-service teachers in Belgium, China, Korea, Japan, Turkey, and the United States demonstrating cross-cultural similarities, despite different educational systems (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2020; Iserbyt et al., Citation2016; Iserbyt, Theys et al., Citation2017; Iserbyt, Ward et al., Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2018; Stefanou et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2017). The studies show that (a) a majority of undergraduates arrive in universities knowing little about the content they are to teach in schools- typically around 60% for CCK and extremely low for SCK, (b) typical PETE instruction improves CCK by approximately 20% but does not impact SCK in significant ways, and (c) instruction focused on SCK can significantly improve their understanding of the content (Kim et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2020).

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) commented relative to culture: “Pre-service teachers are unlikely to reflect on context and culture or how these affect the students with whom they will work” (p. 452). This is an erroneous conclusion based on the empirical evidence in our research papers where we have repeatedly demonstrated changes in both teacher knowledge and teaching practices. Our studies have been conducted in seven countries (Belgium, China, Cyprus, Japan, Korea, Turkey, and the United States) representing different languages, religions, cultures, different schooling systems, different teacher education systems, and different policies governing education. We have developed teacher knowledge tests, pre-service and in-service teacher training to reflect the unique cultural characteristics of each setting. To argue that we do not attend to the culture at either a local or national level is incorrect.

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) also noted: “The idea of quantitative measurement of CK and PCK makes comparison, evaluation and assessment possible and helps to make a case for the inclusion of more CK in PETE courses” (p. 456). Our argument is not about the addition of more classes, though we think too few credit hours in most PETE programs are spent on the content to be taught in K-12 physical education. It is about how and why content knowledge is taught in PETE programs. It is also about ways of thinking about the teaching of content, because it is unrealistic to presuppose that all the content a teacher needs to know to teach, could be taught in a PETE program within the limited time available. The research is also about helping K-12 students learn what they are being taught, and assisting teachers in making informed decisions that may not always be the right decision. But through tinkering with their teaching and reflection, they are able to become lifelong learners of their students and subject matter.

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) made the following claim about our research: “It also raises questions with regards to inclusion and exclusion when the teaching abilities are transformed into numbers. What conceptualization of movement learning for example, do we promote when we label some movements as correct and some as incorrect?” (p. 456). This sweeping statement glosses over important issues our research team has strived to address. What is correct and incorrect in a movement is neither a dichotomous position nor absolute. For example, a student moving through developmental stages 1–3 in learning to throw, might in stage one be performing correctly according to developmental stages, but not be performing the stage two or three (Chang et al., Citation2020). Learning to perform a volleyball pass as a beginner requires different teacher expectations than someone more advanced. Teacher expectations of whether students can improve (or not) their performance and how the teacher can help them do so (or not) involve far more than fundamental discrimination of performance. In summary, quantitative measurement may not satisfy Backman and Barker (Citation2020) epistemology, but to discount it is problematic, if we are to place an understanding of teaching and learning ahead of ideological battles. In short, there are many pieces of the puzzle that is schooling and many sources of evidence.

Assumptions made by Backman and Barker (Citation2020)

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) suggest there are four assumptions that drive our research. In this section, we address each of them.

Assumption one: “The teacher needs to be able to perform activities with the correct technique, know the tactics and have knowledge about rules and etiquette in order to have PCK” (Backman & Barker, Citation2020, p. 454)

We have argued that in teacher education, there is an over-emphasis on content classes teaching performance of motor skills over CCK and in particular SCK (Kim, Citation2015; Ward et al., Citation2012). In several papers, we have noted the widespread, but erroneous assumption in PETE that to teach an activity, you must be able to perform the activity (Kim, Citation2015; Ward, Citation2011; Ward et al., Citation2012). Our research has shown the consequences of requiring PETE students to be strong performers of the content they are to teach at the expense of CCK and SCK (Dervent et al., Citation2020; Kim, Citation2015; Tsuda, Ward, Li et al., Citation2019; Ward, Tsuda et al., Citation2018). We have argued extensively that more time must be devoted to CCK and SCK and that less time should be devoted to a focus on performance (Ayvazo et al., Citation2010; Dervent et al., Citation2020; Kim, Citation2015; Ward, Citation2009, Citation2011; Ward et al., Citation2012).

Moreover, recent research has shown that at the low levels of knowledge that many pre-service and in-service teachers have there is little to no relationship between CCK and SCK (Dervent et al., Citation2020; Tsuda, Ward, Li et al., Citation2019). This finding suggests that CCK and SCK: (a) are independent of each other when knowledge is low, but they theoretically should be related when knowledge of SCK is higher, and (b) should be treated as discrete response classes in teacher training though this does not mean developing them separately. Importantly we have found weak to no correlations depending on the sport between performing and either CCK or SCK (Dervent et al., Citation2020; Tsuda, Ward, Li et al., Citation2019). In brief, while we believe teachers should be able to perform some of the content they teach, they do need to know CCK; importantly, and teachers must also know SCK.

A second point, is how would a teacher teach the lay-up, freestyle crawl, or yoga without knowing the techniques of these movements or knowing the tactics where necessary? Discovering how to do this on your own is time-consuming, hence the role of instruction that should both facilitate and accelerate learning. Performance in sport, dance, weight training, and such is a shared knowledge base that is global and as such as established standard. Third, if the major purposes of learning movements in physical education are to use them in games and life-long activities for fitness, enjoyment, sporting or social outcomes, students should learn the movement in ways that allow them to participate with others who share the same performance understanding (e.g., when to step in dance, the rules of a game, or etiquette).

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) also claimed: “Pre-service teachers’ lack of knowledge concerning movement techniques and rules is seen as highly problematic” (p. 455). How can teachers help students learn content that they (i.e., teachers) do not know? More profoundly, how can teachers who lack content knowledge monitor students’ learning and evaluate students’ competence? For example, we believe that few parents would entrust their children to swimming teachers who did not know the basics and techniques of swimming. Content knowledge is an essential component of PCK and improving teachers’ content knowledge has been demonstrated to improve student learning significantly (Kim et al., Citation2018). Not focusing on improving teaching with demonstrated effective practices raises questions relative to the ethical responsibilities of teachers and teacher educators and the moral imperative of improving schooling.

The erroneous element in Backman and Barker (Citation2020) statement is the phrase “to have PCK.” This represents a fundamental misrepresentation of how we have framed PCK. PCK represents a teacher’s efforts to match content to student learning drawing on a number of knowledge bases (see earlier discussion of PCK). As such, the matching typically is in the form of a task representation and the instructional task may be poor or good or even excellent in facilitating student learning. Sometimes what works in one class or with one student does not work with others. As decision-makers, teachers adapt their instruction, instructional tasks, feedback, and the like to their students. Thus, all instruction is PCK. It varies on continuums from weak to strong and from ineffective to effective (Ayvazo & Ward, Citation2011; Kim, Citation2015). Sometimes, teachers with weak PCK may be able to provide clear and appropriate task representations that result in effective teaching. Similarly, teachers with strong PCK may be ineffective in teaching. However, often weak PCK results in poor student learning whereas strong PCK leads to significant student learning.

Assumption two: “The teacher needs to be able to detect errors and design task progressions in order to have PCK” (Backman & Barker, Citation2020, p. 455)

We have argued that these elements which we call SCK are essential knowledge for teachers (Kim et al., Citation2018; Ward & Ayvazo, Citation2016; Ward et al., Citation2020). Backman and Barker (Citation2020) also claimed: “The emphasis on being able to detect errors and design task progressions raises questions regarding the basis on which errors are identified and task progressions constructed” (p. 455). We do not believe or teach that there is one progression or method for teaching or that a teacher must work from some prescriptive plan. On the contrary, while we build a diverse, practice-responsive competency set for teachers, we are also combatting the de-skilling (also known as “proletarianization”) of teachers and teaching. For example, we have emphasized teachers’ adaptive competence – tinkering with instructional tasks – by which we mean modifying and creating new tasks tied to reflection on their effects. This is a fundamental way for teachers to improve their teaching of content (Ward & Lehwald, Citation2018; Ward, Piltz et al., Citation2018). Schön (Citation1983) defined reflection-on-action as reflecting on how practice can be developed, changed, or improved after the event has occurred, which is an integral part of true learning, to become an active decision-maker and reflective practitioner. In this paper, we have previously addressed the fallacy that our work is prescription-based, arguing that we view the teacher as a adaptive decision-maker.

We have also argued in papers that content knowledge is developmental and specific (Ward & Ayvazo, Citation2016; Ward, Tsuda et al., Citation2018) and that tasks for teaching must be meaningful, relational, progressive, and modifiable (Ward, Tsuda et al., Citation2018). Though the terms used to describe teaching content may be different, this approach is common to most subject matters: primary school content (Ward, Citation2020). We have also argued that professional knowledge and subject-specific knowledge underpinning the decisions a teacher makes should be grounded in the assumption that they work (Kim et al., Citation2018; What Works Clearinghouse, Citation2020). Moreover, teacher educators in pre-service education and professional development are obligated to focus on providing teachers with knowledge that has been demonstrated to be useful (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, Citation2005). We have also recognized that technical aspects of teaching are not the only influence on teaching, as Kim et al. (Citation2018) noted: “The professional judgments of teachers are not only informed by evidenced-based practice, but they are also informed by craft knowledge” (p. 133).

Assumption three: “The teacher needs to be able to select and modify appropriate tasks as well as give feedback in order to have PCK” (Backman & Barker, Citation2020, p. 455)

In their discussion of this assumption Backman and Barker (Citation2020, p. 455) reported on Ayvazo and Ward’s (Citation2011) study noting the physical education teachers “knew which tasks would work.” The teachers in this study were two veteran elementary school teachers recognized by their district, colleagues and university faculty; and from studies as master teachers who had taught elementary school for more than ten years. The teachers knew which tasks would work because of years of teaching experience with the content for specific grade levels at the elementary level and continued professional development along the year. Such expertise results in quite a precise anticipation of students’ responses to the content, and enhanced ability to select appropriate tasks, present tasks accurately and provide precorrection (i.e., correcting an error before it has occurred) or precise corrective feedback for performance. Anticipating student performance and errors is not an unusual outcome for highly competent teachers and is indicative of expertise (Stigler & Miller, Citation2018).

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) also noted, “Again, we would suggest that some consideration of appropriateness is necessary” (p. 455). Fair enough, but it is not clear what Backman and Barker (Citation2020) mean by appropriateness. It is a value-loaded concept. If their comment is relative to what content is being taught, this would be a curricular question, as we have previously noted. If it is the way to teach content, this would be a pedagogical question. If the comment is relative to the appropriateness of the previous tasks or from a safety or lesson objective perspective, this would be a content question. In our studies, we judge the appropriateness in a number of ways.

First, from a developmental perspective, we consider if the task is appropriate for students’ developmental level. Teachers make decisions about the developmental stages of students, and the speed, space, complexity of what is being asked of the student. Second, appropriateness is also judged in terms of alignment to the instructional goal, the degree of complexity from the previous tasks, whether the task was progressed, and the success of students performing the tasks (Kim & Ko, Citation2017; Ward et al., Citation2020). Third, from a content perspective, we would make the case that as teacher educators, researchers, and professional developers we do consider the appropriateness of the content. We also consider curricular and pedagogical questions in our larger work. Our research on content knowledge by definition assumes that these are questions teachers and researchers have determined prior to the selection of content and, at times, from their reflection in and on the action of teaching.

Backman and Barker (Citation2020) concluded their critique with this statement, “What is considered an appropriate or inappropriate task seems to be based on normative assumptions rather than the emerging result of teaching and learning practices” (p. 456). In our discussion above and throughout this paper, we have emphasized teachers’ adaptive competence in variable contexts in service of students’ learning and enjoyment. Adaptive competence, short- and long-term, is a learned orientation. It entails tinkering with instructional tasks, learning from experience as well as from others. This makes the case that all of these elements contribute to a teacher’s knowledge and that there is no one way to teach content. We would consider this as a good example of emerging from teaching and learning practices. Thus, Backman and Barker (Citation2020) are correct that we believe and have demonstrated in our studies that teachers should be able to select and modify appropriate tasks as well as give feedback. When teachers do this, students are more likely to learn than when they do not do this (Kim et al., Citation2018; Stefanou et al., Citation2020). But this is true for every subject area and it is often a part of core teaching practices (Ward, Citation2020).

Assumption four: “The teacher’s level of movement content knowledge and PCK can be quantitatively measured” (Backman & Barker, Citation2020, p. 456)

We agree with this statement. Behavior analytic research is grounded in an inductive model of data collection characterized by observation and experimentation with the goal of supporting education practice. In our work, content knowledge and PCK has been defined as dependent variables and observed through for example, questionnaires and lesson observations. PCK has been observed by focusing specifically on what is the enacted task students are asked to do drawing, as we noted earlier, on the work of Doyle (Citation1986). What is observed can be quantified and thus reported in a number of ways such as totals or frequencies per lesson, as ratios among variables and percentages of the lesson. The validity of these measures has been verified through interobserver agreement and measures of internal validity. Our research outcomes presented in this paper provides strong evidence that CCK, SCK and PCK can be quantitatively measured (e.g., Devrilmez et al., Citation2019; Iserbyt et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2017). However, we would point out that our “numbers, ratios and percentages” are themselves qualitatively determined requiring judgments about the quality of the performance, the appropriateness of decisions, and the success of decisions.

Final comments

Our studies have focused on the questions of what is content knowledge and how does it contribute to PCK? Content in this context is without pedagogical influence, or indeed, the other knowledge bases of PCK. It is thus not the purview of our content knowledge studies to discuss what is the content of physical education. Our questions are about the use of content and its development as a way to enact the curriculum. Our studies of PCK consider in addition to content knowledge other components of PCK such as developmental appropriateness (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2020), curriculum (e.g., Iserbyt et al., Citation2016), and pedagogy (e.g., Ayvazo & Ward, Citation2011).

We have focused primarily on movement content and most of that on sports. It is certainly appropriate to make the case that there are other forms of physical education content that we have not yet addressed. However, whether that content is motoric, affective, or cognitive in nature, our assumptions about the role of the task and decisions that teachers make remain unchanged. In other words, teachers use tasks and pedagogies to enact the curriculum regardless of the form of physical education content. This perspective is consistent with the education field at large (Doyle, Citation1986). Backman and Barker (Citation2020) criticism in this area is one that should occur relative to curricular planning and PCK decisions. Questions such as: (a) For what purpose is the content being taught? (b) Who is advantaged, disadvantaged, or excluded by the teaching of this content? (c) What are the messages being conveyed by the teaching of this content in this way (e.g., hidden curriculum effects)? Such considerations should drive the selection of content, and whatever the content is, it will be enacted via an instructional task (Ward et al., Citation2020).

The goal of research on teaching and thus of studies of PCK is to inform teacher education, teachers, and in turn, to improve student learning. Such efforts should be based on both evidence-based practice and demonstrated craft knowledge. Achieving this goal is enhanced by viewing the challenges from multiple perspectives and critiques of the existing research. Our intent in responding to Backman and Barker (Citation2020) was to correct the misrepresentations of our work and not to stymie critiques or the critics of our work. We welcome critiques because our efforts are far from being complete, and our lens is only one way of looking at PCK. We clearly look at PCK through a different lens than do Backman and Barker (Citation2020), but we view our, their, and other perspectives on PCK with open minds. We place an understanding of teaching and learning ahead of ideological battles.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ayvazo, S., & Ward, P. (2011). Pedagogical content knowledge of experienced teachers in physical education: Functional analysis of adaptations. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(4), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599804

- Ayvazo, S., Ward, P., & Stuhr, P. (2010). Teaching and assessing content knowledge in preservice physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 81(4), 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2010.10598463

- Backman, E., & Barker, D. (2020). Re-thinking pedagogical content knowledge for physical education teachers – Implications for physical education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(5), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1734554

- Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59, 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554.

- Chang, S. H., Ward, P., & Goodway, J. D. (2020). The effect of a content knowledge teacher professional workshop on enacted pedagogical content knowledge and student learning in a throwing unit. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(5), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1743252

- Cooper, J., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey-Bass.

- Dervent, F., Devrilmez, E., Ince, M. L., & Ward, P. (2018). Reliability and validity of football common content knowledge test for physical education teachers. Hacettepe Journal of Sport Science, 29(1), 39–52.

- Dervent, F., Ward, P., Devrilmez, E., & Ince, M. L. (2020). A national analysis of the content knowledge of Turkish physical education teacher education students. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(6), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1779682

- Dervent, F., Ward, P., Devrilmez, E., & Tsuda, E. (2018). Transfer of content development across practica in physical education teacher education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(4), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0150

- Devrilmez, E., Dervent, F., Ward, P., & Ince, M. L. (2019). A test of common content knowledge for gymnastics: A Rasch analysis. European Physical Education Review, 25(2), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17751232

- Doyle, W. (1986). Classroom organization and management. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 392–431). Macmillan.

- Hastie, P., & Siedentop, D. (2006). The classroom ecology paradigm. In D. Kirk, D. MacDonald, & M. O’Sullivan (Eds.), The handbook of physical education (pp. 214–225). Sage.

- He, Y., Ward, P., & Wang, X. (2018). Validation of a common content knowledge test for soccer. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(4), 407–412. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0204

- Iserbyt, P., Coolkens, R., Loockx, J., Vanluyten, K., Martens, J., & Ward, P. (2020). Task adaptations as a function of content knowledge: A functional analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 91(4), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1687809

- Iserbyt, P., Theys, L., Ward, P., & Charlier, N. (2017). The effect of a specialized content knowledge workshop on teaching and learning basic life support in elementary school: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation, 112, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.11.023

- Iserbyt, P., Ward, P., & Li, W. (2017). Effects of improved content knowledge on pedagogical content knowledge and student performance in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2015.1095868

- Iserbyt, P., Ward, P., & Martens, J. (2016). The influence of content knowledge on teaching and learning in traditional and sport education contexts: An exploratory study. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(5), 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2015.1050662

- Kim, I. (2015). Exploring changes to a teacher’s teaching practices and student learning through a volleyball content knowledge workshop. European Physical Education Review, 22(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15599009.

- Kim, I., & Ko, B. (2017). Measuring preservice teachers’ knowledge of instructional tasks for teaching elementary content. The Physical Educator, 74(2), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2017-V74-I2-7366

- Kim, I., & Ko, B. (2020). Content knowledge, enacted pedagogical content knowledge, and student performance between teachers with different levels of content expertise. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0292

- Kim, I., Ward, P., Sinelnikov, O., Ko, B., Iserbyt, P., Li, W., & Curtner-Smith, M. (2018). The influence of content knowledge on pedagogical content knowledge: An evidence-based practice for physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0168

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Lawson, H. A. (2009). Paradigms, exemplars and social change. Sport, Education and Society, 14(1), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320802615247

- Lee, H., Ko, B., Ward, P., Lee, T., Higginson, K., He, Y., & Lee, Y. (2018). Development and validation of common content knowledge test for soccer. Korean Journal of Sports Science, 29(4), 650–662. https://doi.org/10.24985/kjss.2018.29.4.650

- Rovegno, I. (1995). Theoretical perspectives on knowledge and learning and a student teacher’s pedagogical content knowledge of dividing and sequencing subject matter. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 14(3), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.14.3.284

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Sinelnikov, O., Kim, I., Ward, P., Curtner-Smith, M., & Li, W. (2016). Changing beginning teachers’ content knowledge and its effect on student learning. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(4), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2015.1043255

- Skinner, B. F. (1974). About Behaviorism. Knopf.

- Stefanou, L., Tsangaridou, N., Charalambous, Y. C., & Kyriakides, L. (2020). Examining the contribution of a professional development program to elementary classroom teachers’ content knowledge and student achievement: The case of basketball. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2020-0010

- Stigler, J., & Miller, K. (2018). Expertise and expert performance in teaching. In K. Ericsson, R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 431–452). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480748.024.

- Tsuda, E., Ward, P., Li, Y., Higginson, K., Cho, K., He, Y., & Su, J. (2019). Content knowledge acquisition in physical education: Evidence from knowing and performing by majors and nonmajors. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 38(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0037

- Tsuda, E., Ward, P., Yoshino, S., Ogiwara, T., He, Y., & Ohnishi, Y. (2019). Validity and reliability of a volleyball common content knowledge test for Japanese physical education preservice teachers. International Journal of Sport and Health Science, 17, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.5432/ijshs.201916

- Ward, P. (2009). Content matters: Knowledge that alters teaching. In L. Housner, M. Metzler, P. Schempp, & T. Templin (Eds.), Historic traditions and future directions of research on teaching and teacher education in physical education (pp. 345–356). Fitness Information Technology.

- Ward, P. (2011). The future direction of physical education teacher education: It’s all in the details. Japanese Journal of Sport Education Studies, 30(2), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.7219/jjses.30.2_63

- Ward, P. (2013). The role of content knowledge in conceptions of teaching effectiveness in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84(4), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.844045

- Ward, P. (2014). A response to the conversations on effective teaching in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 293–296.

- Ward, P. (2016). Policies, agendas and practices influencing doctoral education in physical education teacher education. Quest, 68(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1234964

- Ward, P. (2020). Core practices for teaching physical education: Recommendations for teacher education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0114

- Ward, P., & Ayvazo, S. (2016). Pedagogical content knowledge: Conceptions and findings in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(3), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0037

- Ward, P., Ayvazo, S., Dervent, F., Iserbyt, P., & Kim, I. (2020). Instructional progression and the role of working models in physical education. Quest, 72(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2020.1766521

- Ward, P., Chen, Y., Higginson, K., & Xie, X. (2018). Teaching rehearsals and repeated teaching: Practiced-based physical education teacher education pedagogies. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 89, 20–25.

- Ward, P., Dervent, F., Lee, Y. S., Ko, B., Kim, I., & Tao, W. (2017). Using content maps to measure content development in physical education: Validation and application. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0059

- Ward, P., He, Y., Wang, X., & Li, W. (2018). Chinese secondary physical education teachers’ depth of specialized content knowledge in soccer. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0092

- Ward, P., Kim, I., Ko, B., & Li, W. (2015). Effects of improving teachers’ content knowledge on teaching and student learning in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.987908

- Ward, P., & Lehwald, H. (2018). Effective physical education content and instruction. Human Kinetics.

- Ward, P., Lehwald, H., & Lee, Y. S. (2015). Content maps: A teaching and assessment tool for content knowledge. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86(5), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2015.1022675

- Ward, P., Li, W., Kim, I., & Lee, Y. S. (2012). Content knowledge courses in physical education programs in South Korea and Ohio. International Journal of Human Movement Science, 6(1), 107–120.

- Ward, P., Piltz, W., & Lehwald, H. (2018). Unpacking games teaching: What do teachers need to know? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 89(4), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2018.1430626

- Ward, P., Tsuda, E., Dervent, F., & Devrilmez, E. (2018). Differences in the content knowledge of those taught to teach and those taught to play. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0196

- What Works Clearinghouse. (2020). Resources. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Resources