?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the role of different types of firms in related and unrelated diversification in regions, in particular the extent to which foreign-owned firms induce structural change in the manufacturing capability base of 67 Hungarian regions between 2000 and 2009. Doing so, it connects more tightly the literatures of evolutionary economic geography and international business. The results indicate that foreign-owned firms deviate more from the region's average capability match than domestic-owned firms. However, this deviation is larger on the short run than in the long run, and more pronounced in peripheral regions and in the capital region.

INTRODUCTION

Regional diversification is often depicted as a branching process in which new activities draw on and combine local activities (Frenken & Boschma, Citation2007). This is because search costs tend to rise rapidly as the gap widens between existing capabilities and new capabilities required to develop new activities, and also because new activities unrelated to existing local activities tend to have a lower probability to survive (Nelson & Winter, Citation1982). A growing body of studies on industrial and technological diversification in regions has documented that related rather than unrelated diversification is indeed the rule (Boschma, Citation2017).

What is still underdeveloped, though, is a microfoundation to this process of regional diversification, despite the fact that there is substantial evidence in the management literature that related diversification is a predominant feature within organizations (Palich, Cardinal, & Miller, Citation2000). Klepper (Citation2007) was one of the first to provide evidence of related diversification in regions at the micro-scale by showing that spinoffs and diversifiers from related industries tend to give birth to new industries in regions. However, we still have little understanding about what types of firms induce more related or more unrelated diversification. More in general, there is little knowledge about how the capability bases of regions evolve over time, and what types of economic agents are responsible for more or less structural change. To our knowledge, Neffke, Hartog, Boschma, and Henning (Citation2018) is the only study to date to have investigated systematically the link between firm dynamics and structural change at the regional scale. They found that the inflow of new plants from outside the region, and not so much local start-ups and incumbents, introduce more unrelated diversification in regions.

This finding of external agents driving structural change in regions makes it relevant to analyze the impact of inward foreign direct investment (FDI), and especially the role of multinational enterprises (MNEs). Studies have focused on the impacts of MNEs on economic development, but most research is performed at the national scale. Beugelsdijk, Mudambi, and McCann (Citation2010) and Iammarino and McCann (Citation2013) have advocated the integration of research in international business and economic geography by investigating more systematically the geography of MNEs at the sub-national scale. In recent years, papers have been published on how MNEs influence the economies of host regions (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013). However, to our knowledge, no paper has yet investigated the extent to which MNEs induce structural change in regions in terms of related or unrelated diversification, also in comparison with other types of firms: Does novelty arise from local domestic firms, or is it introduced by actors from outside the region?

The objective of the paper is to investigate the extent to which FDI induces more related or unrelated diversification in 67 regions between 2000 and 2009 in Hungary, a country that has been invaded by FDI after the fall of the Iron Curtain. From 1990 onwards, foreign firms have become key actors in export, employment (Radosevic, Citation2002; Resmini, Citation2007) and knowledge spillovers (Békés, Kleinert, & Toubal, Citation2009; Halpern & Muraközy, Citation2007; Inzelt, Citation2008). This study is done in the context of a recent finding by Boschma and Capone (Citation2016) that Eastern European countries, as compared with Western European ones, tend to diversify into new industries that are more closely related to their existing industries. The Hungarian case is a prime example of dependent market economies in Central and Eastern Europe (Nölke & Vliegenthart, Citation2009), relying heavily on the international value chains and research and development (R&D) expertise of MNEs, which are predominantly viewed as vehicles for regional economic development (Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2011, Citation2015). The case presented here is also relevant for lagging regions in more developed economies, attempting to attract MNEs in the hope of inducing structural change.

We test whether MNEs, operationalized as firms with majority foreign ownership, are responsible for more unrelated diversification compared with domestic firms in Hungarian regions, using a novel approach developed by Neffke et al. (Citation2018) which measures structural change in terms of how unrelated new activities are to existing ones in regions. We extend that study by placing MNEs into the spotlight as potential agents that can drive structural change of regions by bringing in new capabilities from other locations. As the diversification process may differ between regions (Xiao, Boschma, & Andersson, Citation2018), in a further step we take a look at diversification in three different types of regions. In particular, we focus on MNEs that may bring in novelty to different degrees in a highly urbanized core region, in regions with a long tradition in manufacturing activities and in peripheral regions. While these region groups reflect a well-documented spatial structure in Hungary (Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2015; Lux, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), the analysis on region groups remains explorative at this stage.

In doing so, this paper connects more tightly the literatures of international business and evolutionary economic geography around the theoretical framework of related and unrelated regional diversification. We find that foreign firms tend to show a higher deviation from the region's average capability match and, thus, induce more unrelated diversification in regions, as compared with domestic firms. However, this is conditional on the time frame and the type of regions involved. Foreign firms are agents of structural change on the short run but not that much on the long run; and they generate more structural change in peripheral regions and in the capital city, but less in regions with a long manufacturing tradition.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section develops the theoretical argument, discussing a micro-perspective on related and unrelated diversification in regions, and introduces the case of Hungary. In the empirical section the data and methodology are described, followed by the presentation of the main findings. The last section summarizes the results and offers some conclusions and possible avenues for further research.

REGIONAL DIVERSIFICATION AND MULTINATIONAL ENTERPRISES

New activities in a region do not start from scratch but are embedded in territorial capabilities, that is, they tend to spin out and draw on activities that already exist in the region. This branching phenomenon (Frenken & Boschma, Citation2007) has been analyzed by Hidalgo, Klinger, Barabasi, and Hausmann (Citation2007) at the country level, showing that countries build a comparative advantage in new export products related to existing export products in the country. Neffke, Henning, and Boschma (Citation2011) investigated diversification at the regional level and found a higher entry probability of an industry in a region when technologically related to pre-existing local industries. This finding on related industrial diversification in regions has been replicated in many follow-up studies (e.g., Colombelli, Krafft, & Quatraro, Citation2014; Essletzbichler, Citation2015; He, Yan, & Rigby, Citation2018), also focusing on technological diversification in regions (e.g., Boschma, Balland, & Kogler, Citation2015; Kogler, Rigby, & Tucker, Citation2013; Rigby, Citation2015).

The above findings triggered research to explore conditions that make regions more likely to diversify into related or unrelated activities (e.g., Boschma & Capone, Citation2015, Citation2016; Petralia, Balland, & Morrison, Citation2017). What is still underdeveloped in this literature is a microfoundation to this process of regional diversification. The management literature has shown overwhelming evidence that organizations tend to diversify in related activities (Farjoun, Citation1994; Palich et al., Citation2000). Klepper was one of the first to provide a micro-perspective to the regional branching literature. Studying a number of emerging industries (Klepper, Citation2007; Klepper & Simons, Citation2000), Klepper found that start-ups founded by entrepreneurs with pre-entry experience in related industries (i.e., spinoffs from related industries) and incumbents that diversified from related industries played a crucial role in the formation of new industries in a region.

However, we have little understanding of what types of firms induce related diversification, and what types of firms induce more unrelated diversification. More in general, there is little knowledge of how the capability base of regions evolves over time, and what types of agents are responsible for more radical and transformative change. Neffke et al. (Citation2018) was one of the first studies to investigate systematically the relationship between firm dynamics and structural change in regions. It showed that new plants from outside the region, rather than local start-ups and incumbents, tend to introduce more unrelated diversification in regions. In the short run, this applies especially to new plants set up by entrepreneurs, as compared with new plants set up by incumbents (subsidiaries). In the long run, Neffke et al. found that the difference between these types of new plants disappeared: it turned out to be harder for stand-alone entrepreneur-owned plants to survive in regions that offered no related externalities, while subsidiaries could overcome the liability of newness in host regions that provided no supportive environment by drawing on firm-internal resources of the parent in the home region.

This makes it crucial to study the role of MNEs for regional diversification,Footnote1 an agent type not included in Neffke et al. (Citation2018) because of the lack of data. MNEs take up a large (and still increasing) part of the world economy (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013). Scholars in international business and economic geography have argued there is a scarcity of studies on the geography of MNEs at the sub-national scale (Beugelsdijk et al., Citation2010). In this context, Iammarino and McCann (Citation2013) and Santangelo and Meyer (Citation2017) have advocated the integration of evolutionary concepts such as path dependency and related variety into the study of the geography of MNEs. The technology-gap literature (Fagerberg, Verspagen, & von Tunzelmann, Citation1994) has demonstrated that catching up in countries is more likely to be successful when building on stronger capabilities and the smaller the distance from the technological frontier, but such studies at the sub-regional scale are scarce (Petralia et al., Citation2017). Studies on the internationalization strategies of MNEs have shown that their R&D investments tend to concentrate in a few world-leading centres of excellence where their own technological expertise is related (to benefit from local spillovers) but not identical (to avoid knowledge leakage) to the local technological capabilities (Cantwell & Iammarino, Citation2003; Cantwell & Santangelo, Citation2002). What is missing, though, is systematic evidence on the extent to which MNEs contribute to radical or incremental changes in the economic structure of regions.

MNEs may have a direct effect on structural change in their host economies, depending on the extent to which their investments concentrate in activities that are different from activities in which local firms are active (e.g., Cantwell & Iammarino, Citation2000).Footnote2 R&D investments by MNEs in technologies that are related but not identical to existing technologies in the host region, with the purpose of tapping and exploiting local knowledge while avoiding leakage of their own knowledge, would reflect related diversification in the host region in our terminology. Instead, when MNEs invest in an activity that is new to the host region to exploit low local labour costs, this would reflect more unrelated diversification. Besides a direct effect, there may be also an indirect effect of MNEs on structural change in host regions that may be caused by productivity spillovers (such as inducing local firms to introduce innovations through tougher competition and collaboration with MNEs) and market access spillovers (such as making local firms exporting) (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013). Studies have focused on the impact of MNEs on the upgrading and diversification of indigenous firms (Békés et al., Citation2009), such as Javorcik, Lo Turco, and Maggioni (Citation2018), who found that FDI inflows stimulate the upgrading of indigenous capabilities of local domestic firms, making them move into complex products. What studies demonstrate is that new knowledge brought in by MNEs will not just spill over freely and benefit local firms. This spillover effect of FDI on indigenous firms in host regions depends on the absorptive capacity of local firms (Cantwell & Iammarino, Citation2003), their dynamic capabilities (Teece & Pisano, Citation1994), and the degree of fit between the characteristics of the MNE and the host region (Crescenzi, Gagliardi, & Iammarino, Citation2015; Delios, Xu, & Beamish, Citation2008; Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013).

Despite this vast literature, to our knowledge no paper has yet investigated the extent to which MNEs induce structural change in regions, and related or unrelated diversification in particular, in comparison with other types of firms. Based on the above, we expect that MNEs will induce more structural change than local firms. This is because foreign firms are more connected to international value chains, while local firms have more access to, are more familiar with and more embedded in local capabilities (Neffke et al., Citation2018; Pouder & St. John, Citation1996). This is especially true in the longer run, as we expect MNEs to have higher survival rates than local firms when introducing a new activity more distantly related to existing activities in a region, as MNEs can build on firm-internal resources and capabilities in other regions to which they have access through their intra-corporate networks (Alcácer & Chung, Citation2007; Almeida, Citation1996; Cantwell & Piscitello, Citation2005; Neffke et al., Citation2018).

This paper will test the above expectations in the context of Hungary, a Central and Eastern European country. In Central and Eastern Europe, inward FDI has been a major feature after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Broadly speaking, in the first stage of transition, foreign ownership caused little structural change in these former Communist countries, as investments came into established industries where previously state-owned companies were privatized. In the subsequent stage, inward FDI took place more in new and growing industries (such as automotives). The more recent phase has been characterized by the predominance of foreign-owned firms investing in high-tech and export-oriented industries, in contrast to domestic firms (Damijan, Kostevc, & Rojec, Citation2018; Nölke & Vliegenthart, Citation2009). The time window of the investigation, 2000–09, represents the latter two stages. Regional development policy throughout these stages made efforts through infrastructure development and tax breaks to attract key MNEs that would increase demand for labour and become the core of local traded sectors (Lengyel & Cadil, Citation2009). Regarding diversification, Boschma and Capone (Citation2016) found that Eastern European countries tend to diversify into new industries more closely related to existing industries than do Western European countries.

The second contribution of this paper is an explorative analysis on MNEs as agents of structural change in relatively more developed versus relatively less developed regions. Despite the vast literature on the interaction between MNEs and their host regions discussed above, the question whether MNEs induce more change than domestic firms in both types of regions is non-trivial. As Narula and Dunning (Citation2010) pointed out, the location choice of FDI and location advantages co-evolve over time as regions move through different stages of the investment development path (IDP). More developed regions typically offer different location advantages for MNEs than less developed regions, and the local industry structure is an important element of these advantages (Dunning, Citation2000). However, it is not clear how the local economy is influenced by MNEs attracted by these diverse advantages. Furthermore, Xiao et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that unrelated diversification is more likely in innovative regions and less likely in non-innovative regions. However, it is not clear how local innovative capacities of MNEs or local firms influence the nature of the diversification process. Consequently, whether MNEs induce more structural change than domestic firms in all types of regions is still underexplored.

Hungarian regions differ from one another with respect to industrial structure and FDI intensity. Previous research found that FDI integrated into regional economies to greater extent in relatively developed regions and had only loose local embeddedness in peripheral regions of the country (Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2015). Following the territorial distinction of Lengyel and Leydesdorff (Citation2015) and those of others focusing on re-industrialization (Lengyel, Vas, Szakálné Kanó, & Lengyel, Citation2017; Lux, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), in a final step we check whether the diversification dynamics induced by foreign firms is different in three region types. The first is the capital city (Budapest) that is a frequent host for foreign firms, and which is subject to a general outflow of manufacturing industries. The second is the manufacturing integration zone in the relatively developed north-western part of the country that gained access to international value chains through foreign actors. The third is a group of peripheral regions in the south and east that are relatively underdeveloped and characterized mostly by low value-added activities such as textile and food industries, and where the main objective of foreign firms is the access to low labour costs and consumer markets. As we do not have clear theoretical expectations on how agents (and MNEs in particular) affect diversification in these territories differently, this part of the paper is more explorative in nature.

DATA, SAMPLING, VARIABLES AND METHODS

The investigation relies on a firm-level panel micro-database, made available by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, which contains various balance sheet data on companies conducting business in Hungary and using double-entry bookkeeping. These concern tax declaration data that firms in Hungary have to submit to the National Tax Office. Data include the location of the company seat at the municipality level, the number of employees, the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE) classification of the main activity of the company at the four-digit level, and several balance sheet variables such as the ownership structure of the total equity capital. We limit our investigation of structural change to the 10-year period between 2000 and 2009 due to data availability.

We imposed some restrictions on the data to arrive at the final sample of companies. First, we focus only on manufacturing firms (industries 15–37 in NACE Rev. 1.1 coding) because company seat data are at our disposal, which are more likely to represent the actual place of economic activity in the case of manufacturing. In order to increase the reliability of the data, we limit our analysis to those firms that had at least two employees between 2000 and 2009. Naturally, increasing this threshold would further improve data reliability. However, doing so would also introduce bias towards incumbent firms as new entrants tend to be smaller in size.

In order to classify firms into agent types, we use two dimensions yielding a total of eight agent types. The first dimension for classifying agents is ownership. There is a significant heterogeneity of MNEs with respect to structure (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013), nationality, motives and ownership (Smeets, Citation2008). We operationalize MNEs based on the latter aspect, whereas we cannot take into account other aspects due to lack of data. In this paper a firm is considered foreign-owned if more than 50% of its total equity capital belongs to a foreign owner. In principle, the degree of foreign ownership could be indicative of the nature of MNE activity (Smeets, Citation2008). However, the ownership distribution of Hungarian firms is extremely polarized, that is, the share of foreign ownership in most cases is either > 90% or < 5% (see Figure A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

The second dimension concerns firm life cycle, meaning we divide firms into entrants, growing incumbents, declining incumbents and exits. For analytical purposes we consider a firm an entrant in year if it is present that year, but not in the previous one. We classify a firm incumbent in year

if it was present in the previous year as well as in the next year. Finally, we consider a firm to exit in year

if it is present in the data that year but not in the proceeding one. To distinguish between growing and declining incumbents, we compare the employment of those firms classified incumbents in year

with their employment value in

. Incumbents that managed to increase their employment are deemed growing incumbents, while those firms that decreased in size are considered declining incumbents. Unfortunately, unlike Neffke et al. (Citation2018), we cannot identify entrepreneurial activity and new establishments of existing firms with the data at hand.

To determine these firm attributes, we also used the panel data for 1999 and 2010, but left these years out of the final sample, as otherwise all firms would have been considered entrants in 1999, while all firms would have exited in 2010. To perform this classification, we consider only those firms that are present in the panel without gaps, and are present for more than one year. The latter step is necessary to avoid classifying a firm as entry and exit in the same year.

We use micro-regions as the spatial unit of analysis because these 175 territories represent nodal regions of towns in Hungary and correspond to the local administrative unit (LAU)-1 administrative level of the European Union spatial planning system. In the final step of the sample selection process, we restrict the analysis to those regions that had at least five domestic and foreign firms throughout the period 2000–09. As a consequence, 67 micro-regions constitute our final sample of regions, representing larger settlements with at least some manufacturing activities. The pool of firms in our analysis represents on average 37% of all manufacturing firms in the data, and these firms employ on average 74% of all employees in manufacturing (see Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). On average, 87% of firms in the sample are domestic; however, these firms represent on average 52% of employees. In addition, the share of domestic firms slightly increased during the period 2000–09, while their share of total employment slightly decreased (see Table A2 in Appendix A online).

For our investigation of structural change, we follow the novel measurement approach introduced by Neffke et al. (Citation2018). First, we measure the degree of skill relatedness between industries (Neffke & Henning, Citation2013) (for a visual representation of the skill relatedness network, see Figure A4 in Appendix A online), by using a matched employer–employee data set provided by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, making it possible to track labour flows between industries for the period 2003–10. As shown in equation (1), the skill relatedness measure () compares the observed labour flow (

) between a pair of (four-digit NACE) industries (

) with the expected labour flow between them

:

(1)

(1)

The normalized form of skill relatedness is used, meaning that it ranges form –1 to 1, with a higher value meaning stronger skill relatedness between industries. For analytical purposes, we subsequently consider a pair of industries related if their skill relatedness is > 0. The manufacturing focus of the analysis makes it necessary that we exclude those ties between industries that involve non-manufacturing industries.

Next, with the help of the skill relatedness measure, we calculate the amount of related employment () in a region (

) in a year (

) for each four-digit NACE industry in the sample. We dichotomize the skill relatedness measure with an indicator function (

) so that it gives a value of 1 if skill relatedness is > 0, and 0 otherwise. The measure allows for similarity of industries, meaning that related employment for each industry equals the sum of employment in related industries and the industry itself:

(2)

(2)

The third step is to quantify how each industry matches the industrial structure of a region in a year. To do so, a modified location quotient is used that measures how overrepresented are related industries () in a regional industry portfolio (

) compared with the share of related industries (

) in the overall country level portfolio (

):

(3)

(3)

To reduce the skewness of the distribution of the location quotient, it is normalized to produce the capability match () variable, which ranges from –1 to 1. A match value > 0 indicates an overrepresentation of related industries in a region in a year. Industries with a high match value are more related to the regional industrial portfolio of that year:

(4)

(4)

Industries in a regional portfolio of a given year have different match values, but industries in some regions are more related on average than in others. To capture this coherence (), we calculate the weighted average capability match within each region in each year, where the weights are the share of employment of each industry (

) from the regional portfolio (

) that year. As shown in equation (5), a higher value of coherence would indicate that a region has more industries that are more related to the regional portfolio:

(5)

(5)

Now each agent () in a regional economy can be characterized by the deviation of its industry's capability match from the region average (

). A positive value of such deviation implies that the agent's industry is above-averagely related to the regional portfolio. We aim to find out whether agents of the same agent type tend to deviate from the region average capability match over time. To describe the distribution of this deviation within an agent type, in the final step we calculate the structural change induced by an agent typeFootnote3 (

) over a period of time (between

and

, where

) as the weighted average level of deviation of the base year (

). Here the weights are calculated as the share of employment created or destroyed by an agent of an agent type (

) in the total employment change (

) induced by the agent type over a period of time (

). As shown in equation (6), the employment effect of entrants and exits is measured as their employment value in the year of entry or exit, while the employment effect of growing and declining incumbents is the change in their employment values over the period concerned:

(6)

(6)

The values of the structural change variable range from –2 to 2, and values > 0 indicate above-average capability match between an agent type and the regional industrial portfolio. The regional capability base will be reinforced over time if an agent type tends to create employment in industries with above-average match score, that is, it shows a positive score on the structural change variable. Below-average match score would instead indicate the weakening of the same regional capability base. Agent types that destroy employment have an influence in the opposite direction. This is summarized in . The aim is to determine which agents change the economy of a region. Following Neffke et al. (Citation2018), we estimate the above unconditional mean structural changes with a weighted regression. We obtain short-term change using employment weights between 2000 and 2001, and long-term structural change values using weights calculated over the period 2000–09, while capability match and coherence values for the base year of 2000 are used.

Table 1. Summary of the relationship between agent types and regional capability bases.

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN HUNGARIAN REGIONS

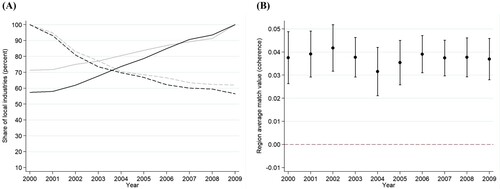

shows there are substantial changes in the industrial composition of regions during the period 2000–09. Only 60% of the four-digit industry–region combinations present (i.e., with concentrated employment, ) in 2000 were still present in 2009, while 30–40% of the industry–region combinations present in 2009 were not present in 2000. When considering employment in foreign and domestic firms separately, it is revealed that a lower percentage of industry–region combinations of 2009 were already present (i.e., with concentrated employment considering only foreign firms,

) in 2000 in the case of foreign firms compared with the industry–region combinations considering employment only in domestic firms. The differences between the ownership groups are marginal when it comes to industries phasing out from the industrial composition of regions. This finding already suggests that foreign firms are more active in exploring new (to-the-region) economic activities compared with domestic firms.

Figure 1. Turnover of regional industries and average levels of regional coherence, 2000–09.

Note: (A) Turnover of regional industries, 2000–09. Dashed lines indicate the share of industry–region combinations with concentrated employment () in 2000 out of the industry–region combinations with concentrated employment (

) in year

; solid lines indicate the share of industry–region combinations with concentrated employment (

) in 2009 out of the industry–region combinations with concentrated employment (

) already in year

. Black lines indicate shares calculated with employment concentration considering only the employment in foreign firms; grey lines indicate shares calculated with employment concentration considering only the employment of domestic firms. (B) Average levels of regional coherence, 2000–09. The dashed line indicates no average over- or underrepresentation of related industries in year

. Values above this line indicate on average a concentration of related employment in regions.

However, the mere appearance of new industries may or may not change the underlying capability base of regions. Indeed the average skill relatedness of industries within regions (i.e., coherence), averaged across regions, as shown in , is positive and relatively stable over time. This means that regions house a concentration of related industries for economic agents. Moreover, the average concentration of skill related industries in regions shows stability, in spite of the considerable turnover of industries.

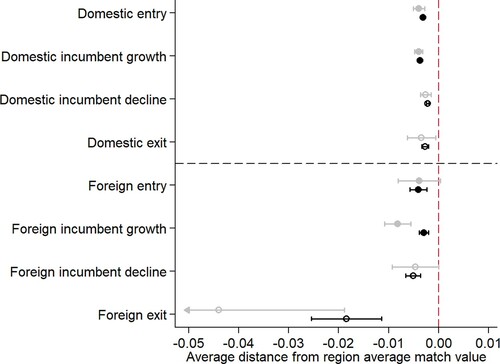

Now we turn to the change in the composition of the aforementioned regional bundle of capabilities, starting with short-term (one-year) change. As shown in , new firms and growing incumbents tend to weaken the regional capability base by creating employment in industries that are below-averagely skill-related to the region. While declining incumbents as well as exits appear to be below-averagely related to the region as well, this indicates that they reinforce the capability base, because they destroy employment in more unrelated activities. This pattern of firm population dynamics underpins the observation about the stability of the regional capability base made above, as new and successful economic actors balance out, on average, declining and exiting firms.

Figure 2. Short- and long-term structural change in regions by agent type.

Note: The vertical dashed line indicates the average distance of agent types from the regional average match value. Values to the right of this line indicate more related (i.e., above-average) diversification, while values to the left indicate more unrelated (i.e., below-average) diversification. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The base year is 2000. Grey markers indicate a one-year change; black markers indicate a 10-year change.

Looking at the firm population dynamics, in general we find no statistically significant difference between new entrants and growing incumbents in terms of relatedness to the region's capability base, both bringing novelty to the region. This finding is different from what Neffke et al. (Citation2018) found. Second, growing firms engage in activities that are on average more unrelated to the existing capability base compared with declining incumbents, although this is not statistically significant. Third, in the case of foreign firms, new entrants are more related on average to the capability base of the region compared with exiting firms. This is in line with Neffke et al. and our understanding of the evolution of regions following a path-dependent process in which activities more related to the region are more likely to enter, while those that are less related are more prone to exit (Neffke et al., Citation2011). In sum, this dynamic reinforces the capability base of regions to some extent, as the employment created is more closely related to regional activities than the employment destroyed.

Zooming in on domestic versus foreign ownership, we found that in the short run, growing foreign incumbents in particular happen to occur in industries that are more unrelated to existing activities in the region as opposed to domestic ones. In line with our expectations, this finding suggests that successful foreign incumbents are shaping regional capability bases to a higher degree than successful domestic incumbents. However, this pattern does not hold statistically significantly for pairwise comparisons between domestic and foreign entrants and declining incumbents. The fact that growing foreign firms can deviate more from the regional capability base suggests that MNEs may be able to compensate for the lack of access to regional capabilities through their intra-corporate networks. When assessing their impact on the regional capability base, one has to keep in mind the relatively low number of foreign firms (15%) in our data set, although their share in employment (47%) is considerable (see Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

Another finding is that foreign exits tend to deviate most from the regional capability base, and foreign exit occurs at lower average capability match compared with domestic exit. This is not surprising, as one would expect foreign firms that are disconnected from regional capabilities to be less harmed because of their access to firm-internal resources. Having said that, caution is warranted when interpreting the foreign exit match distribution, because it is by far the most volatile among the agent types and through different time horizons (see Figure A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). This volatility is most likely caused by the relatively small number of exits in the sample, as well as the ‘chunkiness’ of employment, meaning that an exit event affects the number of employees at once. In the base year of 2000, 70 instances of foreign exit occurred, representing 0.71% of the firm sample in that year, averaging 100 employees each (see Table A2 in Appendix A online).

These findings on structural change are for the most part persistent over time, with a slight shift towards more related activities when moving from the short to the long term ( and see also Figure A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). This shift is most pronounced when looking at growing foreign firms and foreign exits on the long run (10-year structural change). This suggests that persistent success requires a stronger fit to the regional capability base even for MNEs that have access to firm-internal resources to compensate for the lack of local capabilities. This may partly be attributed to stronger relationships between MNEs and local firms established over time (Wintjens, Citation2001). It is interesting to see that the average match of growing foreign firms gets close to the average match of growing domestic firms over time (see Figure A3 in Appendix A online), indicating that, in the longer run, growing firms, regardless of ownership, rely on the regional capability base to a considerable degree.

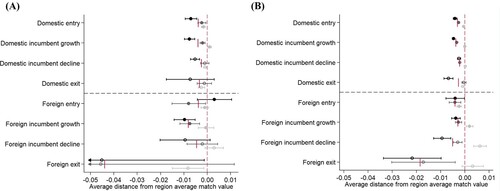

Figure 3. Structural change by agent type in the three region groups.

Note: (A) Short-term (one-year) structural change; and (B) long-term (10-year) structural change. The vertical dashed lines indicate the average distance of agent types from the region average match value. Values to the right of these lines indicate more related (i.e., above-average) diversification, while values to the left indicate more unrelated (i.e., below-average) diversification. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The base year is 2000. Black error bars depict the manufacturing integration zone; dark grey error bars indicate the peripheral regions; light grey bars signify the capital city; and the solid vertical lines indicate the agent type-average structural change.

In a final step, we refine the above findings by differentiating between three groups of regions because, as argued in the theoretical section, the co-evolution of FDI activity and industrial structure may be conditional on the type of region involved. A high share of FDI characterizes the surrounding regions of the capital city, and also the north-west of the country, representing the manufacturing integration zone (see Figure A4 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Interestingly, the regional coherence values do not correlate with the share of inward FDI in the region, as the correlation coefficient is –0.03 over the period 2000–09. This suggests that the strong presence of foreign firms is not necessarily accompanied by a regional capability base that contains more unrelated elements.

shows the degree of structural change induced by each agent types in the three region groups. In the manufacturing integration zone, both growing and declining firms tend to be more unrelated to the regional portfolio of activities compared with other region groups, although this difference is not statistically significant for foreign firms. Interestingly, foreign entrants in these regions initially match the capability base well, but these firms gradually introduce more and more unrelated activities to the region as time passes (see Figure A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Moreover, domestic entrants are also exploring more unrelated activities, staying further from the region average match than in any other region group. The pattern that emerges from the long-term structural change values is that there is a large amount of exploration going on by both domestic and foreign agents in the manufacturing integration zone, as most new entries, as well as growing incumbents, are associated with unrelated activities. On the flip side, declining and exiting firms in this region group also tend to be more unrelated to the capability base of 2000 compared with the other two region groups. This difference is statistically significant in the case of domestic incumbent decline on the short run and domestic exit and foreign incumbent decline on the long run.

In peripheral regions, most agent type behaviour tends to mimic the overall pattern seen for Hungary. As shows, both domestic and foreign agents, with the exception of foreign entry, show smaller average deviations from the region's average compared with the manufacturing integration zone, although the difference is not significant in some cases. Employment creating foreign firms show a higher average capacity for inducing structural change compared with domestic firms on the short run.

The capital city is very different from the manufacturing integration zone. As shows, domestic firms barely exhibit any tendency to deviate from the region average match score, especially on the long run. Foreign entrants tend to well match the capability base at an average level in the short run, and gradually become slightly more unrelated over time (see Figure A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). This indicates that foreign entries slightly weaken the capability base in the capital region. From a location choice perspective, foreign firms may seek out locations that are more successful at signalling their available resources, and the capital city has the most capacity to do so. Domestic firms, on the other hand, are well endowed with locally available knowledge, matching the capability base more tightly over time. Foreign exit on the short run happens at a larger distance from the regional capability base; however, this deviation is the smallest among the region groups. Foreign incumbents match the capability base averagely in the short run. Interestingly, foreign incumbents and exits shift to the related side in the longer run, meaning that foreign growing incumbents reinforce the regional capability base, while foreign declining incumbents and foreign exits weaken the manufacturing capabilities in the capital over time.

CONCLUSIONS

The literature on regional diversification has demonstrated that local capabilities are a strong driving force behind regional diversification, but that regions also evolve in more unrelated directions now and then (Boschma, Citation2017). However, there is still little understanding of what types of firms, including external agents such as MNEs, induce related and unrelated diversification in regions. We show that MNEs are key agents of structural change. Following a novel measurement approach introduced by Neffke et al. (Citation2018), our study of 67 Hungarian regions show that foreign firms induce more structural change in regions than do domestic firms. In particular, the fact that growing foreign firms (and to a lesser extent the entry of foreign firms) can deviate more from the regional capability base suggests that MNEs may be able to compensate for the lack of access to regional capabilities through their intra-corporate networks. We also observed a slight shift towards more related activities in the long run, especially for growing foreign firms and foreign exits, suggesting that a stronger fit to the regional capability base is important even for MNEs despite access to firm-internal resources. Finally, we found significant differences across regions: agents in the manufacturing integration zone tend to be more unrelated to the region capability base than in the capital city. What makes the Budapest region unique is that growing and declining foreign firms as well as foreign exits are more related on average to the capability base of the region in the long run. Interestingly, in the short term, foreign entry induces related diversification in the manufacturing integration zone and more unrelated diversification on the periphery, but it drives more unrelated diversification in all regions in the long run. It was also revealed that, compared with their domestic counterparts, successful foreign incumbents introduce more unrelated activities particularly on the periphery in the short run, that foreign entrants and declining foreign incumbents induce more structural change in the capital city, while these differences are not significant in the case of the manufacturing integration zone.

This paper takes a first step to integrate research on regional diversification with the vast literature on MNEs. However, as any other paper, our study has a number of limitations that should be taken up in future research.

First, with our data at hand, we could not make a distinction between different internationalization strategies of MNEs that might be highly relevant for the type of diversification MNEs might cause directly or indirectly in regions (Santangelo & Meyer, Citation2017). The present analysis is focused on the direct effects of MNEs on regional diversification and not on the indirect effects of MNEs on local indigenous firms. Therefore, there is a need to conduct a systematic analysis on both the direct and the indirect effects of MNEs on structural change in regions. In this respect, one could hypothesize that when the direct effect of MNEs cause unrelated diversification (investing, for instance, in activities completely new to the host region to benefit from low costs to produce standardized goods), we expect the indirect spillover effects to local indigenous firms to be low due to the large gap between the new and existing local activities. On the contrary, when the direct effect of MNEs would induce related diversification (through, for instance, R&D investments in activities related to local activities for the purpose of exploiting local learning opportunities), one would expect the indirect effects to be larger because spillovers are enhanced across related activities.

Second, there is a need to integrate our approach on industrial diversification in regions with the global value chain approach that focuses more on stages of production within industries (Los, Timmer, & de Vries, Citation2015). This is because the impact of MNEs on regional diversification may be reflected in a move into new industries (as shown in our study), but also into new production stages (e.g., from low to high complexity) within the same industry. The latter would mean the region would diversify into new (and more sophisticated) stages of the global value chain, which requires also very different capabilities and, therefore, would be completely in line with the definition of structural change employed in this study.

Another limitation of our study is that it was limited to manufacturing industries due to data restrictions. Future research should focus on the impact of MNEs on diversification into service industries that nowadays take up a considerable part of regional economies (Ascani & Iammarino, Citation2018).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.9 MB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Matte Hartog, Frank Neffke, Simona Iammarino and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose for helpful suggestions. They acknowledge the assistance of members of the Economics of Networks Unit and the Data Bank of Institute of Economics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in creating the skill-relatedness matrix. An earlier working paper version of this study was made available as part of the Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography series (No. 18.12) of the Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In international business studies, regional diversification often gets a different meaning. While we focus on diversification of regions at the sub-national scale (as embodied in the successful emergence of an industry or technology that is new to the region), the international business literature often refers to regional diversification when an MNE pursues a diversification strategy within a region or across regions (Qian, Li, & Rugman, Citation2013).

2. Taking a global value chain perspective focusing on shifts in tasks rather than industries, MNEs could also cause a shift from low- to high-tech tasks within the same industry in the host region (Damijan et al., Citation2018). This could be interpreted as structural change, as it requires different capabilities in the host region to make that shift. The present paper follows Neffke et al. (Citation2018) and sticks to industrial change because this enables one to make a distinction between related diversification, defined as industrial change within the same set of capabilities, and unrelated diversification, defined as industrial change requiring a transformation of underlying capabilities.

3. Structural change was indicated by A in Neffke et al. (Citation2018).

REFERENCES

- Alcácer, J., & Chung, W. (2007). Location strategies and knowledge spillovers. Management Science, 53(5), 760–776. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0637

- Almeida, P. (1996). Knowledge sourcing by foreign multinationals: Patent citation analysis in the US semiconductor industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 155–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171113

- Ascani, A., & Iammarino, S. (2018). Multinational enterprises, service outsourcing and regional structural change. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(6), 1585–1611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bey036

- Békés, G., Kleinert, J., & Toubal, F. (2009). Spillovers from multinationals to heterogeneous domestic firms: Evidence from Hungary. World Economy, 32(10), 1408–1433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01179.x

- Beugelsdijk, S., Mudambi, R., & McCann, P. (2010). Introduction: Place, space and organization: Economic geography and the multinational enterprise. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(4), 485–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq018

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R., Balland, P.-A., & Kogler, D. F. (2015). Relatedness and technological change in cities: The rise and fall of technological knowledge in U.S. metropolitan areas from 1981 to 2010. Industrial and Corporate Change, 24(1), 223–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtu012

- Boschma, R., & Capone, G. (2015). Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Research Policy, 44(10), 1902–1914. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.06.013

- Boschma, R., & Capone, G. (2016). Relatedness and diversification in the European Union (EU-27) and European neighbourhood policy countries. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(4), 617–637. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614729

- Cantwell, J., & Iammarino, S. (2000). Multinational corporations and the location of technological innovation in the UK regions. Regional Studies, 34(4), 317–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400050078105

- Cantwell, J., & Iammarino, S. (2003). Multinational corporations and European regional systems of innovation. London: Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203986714

- Cantwell, J., & Piscitello, L. (2005). Recent location of foreign-owned research and development activities by large multinational corporations in the European regions: The role of spillovers and externalities. Regional Studies, 39(1), 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320824

- Cantwell, J., & Santangelo, G. D. (2002). The new geography of corporate research in information and communications technology (ICT). Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 12(1), 163–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2720-0_17

- Colombelli, A., Krafft, J., & Quatraro, F. (2014). The emergence of new technology-based sectors in European regions: A proximity-based analysis of nanotechnology. Research Policy, 43(10), 1681–1696. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.07.008

- Crescenzi, R., Gagliardi, L., & Iammarino, S. (2015). Foreign Multinationals and domestic innovation: Intra-industry effects and firm heterogeneity. Research Policy, 44(3), 596–609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.12.009

- Damijan, J., Kostevc, Č, & Rojec, M. (2018). Global supply chains at work in Central and Eastern European countries: Impact of foreign direct investment on export restructuring and productivity growth. Economic and Business Review, 20(2), 237–267.

- Delios, A., Xu, D., & Beamish, P. W. (2008). Within-country product diversification and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 706–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400378

- Dunning, J. H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review, 9(2), 163–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0969-5931(99)00035-9

- Essletzbichler, J. (2015). Relatedness, industrial branching and technological cohesion in US metropolitan areas. Regional Studies, 49(5), 752–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.806793

- Fagerberg, J., Verspagen, B., & von Tunzelmann, N. (Eds.). (1994). The dynamics of technology, trade and growth. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Farjoun, M. (1994). Beyond industry boundaries: Human expertise, diversification and resource-related industry groups. Organization Science, 5(2), 185–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.2.185

- Frenken, K., & Boschma, R. (2007). A theoretical framework for evolutionary economic geography: Industrial dynamics and urban growth as a branching process. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 635–649. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm018

- Halpern, L., & Muraközy, B. (2007). Does distance matter in spillover? Economics of Transition, 15(4), 781–805. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2007.00308.x

- He, C., Yan, Y., & Rigby, D. (2018). Regional industrial evolution in China. Papers in Regional Science, 97(2), 173–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12246

- Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabasi, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144581

- Iammarino, S., & McCann, P. (2013). Multinationals and economic geography, location, technology and innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Inzelt, A. (2008). The inflow of highly skilled workers into Hungary: A by-product of FDI. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(4), 422–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-007-9053-z

- Javorcik, B. S., Lo Turco, A., & Maggioni, D. (2018). New and improved: Does FDI boost production complexity in host countries? Economic Journal, 128(614), 2507–2537. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12530

- Klepper, S. (2007). Disagreements, spinoffs, and the evolution of Detroit as the capital of the U.S. automobile industry. Management Science, 53(4), 616–631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0683

- Klepper, S., & Simons, K. L. (2000). Dominance by birthright: Entry of prior radio producers and competitive ramifications in the U.S. television receiver industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 997–1016. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<997::aid-smj134>3.0.co;2-o

- Kogler, D. F., Rigby, D. L., & Tucker, I. (2013). Mapping knowledge space and technological relatedness in US cities. European Planning Studies, 21(9), 1374–1391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.755832

- Lengyel, B., & Cadil, V. (2009). Innovation policy challenges in transition countries: Foreign business R&D in the Czech Republic and Hungary. Transition Studies Review, 16(1), 174–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11300-009-0046-5

- Lengyel, B., & Leydesdorff, L. (2011). Regional innovation systems in Hungary: The failing synergy at the national level. Regional Studies, 45(5), 677–693. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343401003614274

- Lengyel, B., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). The effects of FDI on innovation systems in Hungarian regions: Where is the synergy generated? Regional Statistics, 5(1), 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.15196/rs05101

- Lengyel, I., Vas, Z., Szakálné Kanó, I., & Lengyel, B. (2017). Spatial differences of reindustrialization in a post-socialist economy: Manufacturing in the Hungarian counties. European Planning Studies, 25(8), 1416–1434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1319467

- Los, B., Timmer, M. P., & de Vries, G. J. (2015). How global are global value chains? A new approach to measure international fragmentation. Journal of Regional Science, 55(1), 66–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12121

- Lux, G. (2017a). A külföldi működő tőke által vezérelt iparfejlődési modell és határai Közép-Európában. Tér és Társadalom, 31(1), 30–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.17649/tet.31.1.2801

- Lux, G. (2017b). Újraiparosodás Közép-Európában. Budapest–Pécs: Dialóg Campus.

- Narula, R., & Dunning, J. H. (2010). Multinational enterprises, development and globalization: Some clarifications and a research agenda. Oxford Development Studies, 38(3), 263–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2010.505684

- Neffke, F., Hartog, M., Boschma, R., & Henning, M. (2018). Agents of structural change: The role of firms and entrepreneurs in regional diversification. Economic Geography, 94(1), 23–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1391691

- Neffke, F., & Henning, M. (2013). Skill relatedness and firm diversification. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 297–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2014

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

- Nölke, A., & Vliegenthart, A. (2009). Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: The emergence of dependent market economies in East Central Europe. World Politics, 61(4), 670–702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887109990098

- Palich, L. E., Cardinal, L. B., & Miller, C. (2000). Curvilinearity in the diversification–performance linkage: An examination of over three decades of research. Strategic Management Journal, 21(2), 155–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(200002)21:2<155::aid-smj82>3.0.co;2-2

- Petralia, S., Balland, P.-A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Climbing the ladder of technological development. Research Policy, 46(5), 956–969. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.03.012

- Pouder, R., & St. John, C. H. (1996). Hot spots and blind spots: Geographical clusters of firms and innovation. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1192–1225. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/259168

- Qian, G., Li, L., & Rugman, A. M. (2013). Liability of country foreignness and liability of regional foreignness: Their effects on geographic diversification and firm performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(6), 635–647. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.21

- Radosevic, S. (2002). Regional innovation systems in Central and Eastern Europe: Determinants, organizers and alignments. Journal of Technology Transfer, 27(1), 87–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013152721632

- Resmini, L. (2007). Regional patterns of industry location in transition countries: Does economic integration with the European Union matter? Regional Studies, 41(6), 747–764. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701281741

- Rigby, D. (2015). Technological relatedness and knowledge space: Entry and exit of US cities from patent classes. Regional Studies, 49(11), 1922–1937. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.854878

- Santangelo, G. D., & Meyer, K. E. (2017). Internationalization as an evolutionary process. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9), 1114–1130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0119-3

- Smeets, R. (2008). Collecting the pieces of the FDI knowledge spillovers puzzle. World Bank Research Observer, 23(2), 107–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkn003

- Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3), 537–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/3.3.537-a

- Wintjens, R. (2001). Regional economic effects of foreign companies. A research on the embeddedness of American and Japanese companies in Dutch regions (Netherlands Geographical Studies No. 286). Utrecht: KNAG/University Utrecht. [in Dutch]

- Xiao, J., Boschma, R., & Andersson, M. (2018). Industrial diversification in Europe: The differentiated role of relatedness. Economic Geography, 94(5), 514–549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1444989