ABSTRACT

Governments’ occasional failures to respond to voters’ preferences are usually ascribed to ‘rational’ behaviours; that they are knowingly being ‘responsible’ rather than ‘responsive’, prioritising perceived policy benefits over electoral goals. Yet given the increasing evidence that decision-makers are poor at estimating public opinion, could an additional explanation for their occasional failure to respond simply be that they fail to anticipate the unpopularity of such decisions? In this study, I trace the decision-making process in three cases where UK governments took electorally costly decisions to explore whether and why decision-makers misjudged voters’ reactions. I find that key decision-makers dismissed signals that voters would punish them for these actions, often prioritising information that reinforced their existing policy preferences. The results support findings that decision-makers’ judgements are compromised by motivated reasoning and shed light on how politicians’ failure to estimate public opinion plays out in practise.

Introduction

Why do governments sometimes take electorally damaging decisions? This is a question that has received surprisingly little scholarly attention within the large literature on the relationship between government decisions and public opinion. Existing scholarship has mostly focused on ‘rational’ explanations for governments’ failure to respond to voters. These highlight the tension between governments being ‘responsive’ to voters’ preferences and ‘responsible’ to voters’ interests (Bardi et al., Citation2014; Karremans & Lefkofridi, Citation2020; Mair, Citation2009) such as prioritising desired policy goals over electoral self-interest (Jacobs & Shapiro, Citation2000; Salmon, Citation1993; Strøm, Citation1990; Wittman, Citation1983). A recent study of Belgian politicians confirmed that decision-makers identified such factors as reasons why they might take unpopular decisions (Soontjens, Citation2022). Alternatively, it has been theorised that unpopular governments are more likely to take electorally risky policy decisions in an effort to regain electoral ground (Elmelund-Præstekær & Emmenegger, Citation2013; Vis & Van Kersbergen, Citation2007), or that governments may enact policies that are electorally damaging in the short-term but strategically advantageous in the long-run (Dunleavy & Ward, Citation1981). All these theories share the expectation that political decision-makers are able to gauge voters’ preferences, but that they may sometimes prioritise goals other than short-term responsiveness to voters’ preferences. As such, they describe ‘rational’ deviations from responsiveness.

However, are unpopular decisions always knowingly taken? Scholars have alluded to the possibility that decision-makers may misjudge how voters will react to their decisions (Converse & Pierce, Citation1986) but there has been limited investigation of the extent to which this occurs. Studies into cases of policy failure have found that politicians make misjudgements about policy outcomes (e.g. Smith, Citation1991), but do not tend to focus on misjudgements about electoral outcomes.

Although being able to make good judgements about public opinion might be seen as a necessary skill for political elites, there is increasing evidence that politicians and their advisors are poor at estimating levels of support for different policies (Broockman & Skovron, Citation2018; Dekker & Ester, Citation1989; Hertel-Fernandez et al., Citation2019; Holmberg, Citation1999; Norris & Lovenduski, Citation2004; Pereira, Citation2021; Walgrave et al., Citation2023). There are however two limitations to these findings from surveys of political decision-makers. Firstly, we do not know whether political actors expend more effort in finding out information about voters’ preferences outside of a survey setting in which they may draw on heuristic, unreflective thinking when answering questions about the likely levels of support for a particular policy. In practise political actors may take more time to consider information about the likely electoral effects of a decision, leading them to more accurate conclusions. Secondly, existing surveys have focused on the perceptions of legislators and their advisers (and even sometimes on local politicians’ perception of support for national issues). Whilst legislators are usually responding to the initiatives of others when deciding how to act in a roll-call vote, executives have more agency to set the political agenda, except in the case of decisions that are forced on them by external events. Additionally, since it is highly likely that multiple actors are involved in decisions taken by executives, misperceptions of voters’ perceptions by individual political actors should be unlikely to result in electorally damaging decisions unless these misperceptions are shared across all decision-makers involved. Therefore, unforced decisions by executives that prove electorally costly offer a peculiar puzzle.

This paper contributes to our knowledge by examining three electorally costly decisions from the UK to understand how the electoral reactions to those decisions were perceived: the New Labour government’s decision to allow Eastern European EU migrants to seek work in 2004, the Liberal Democrats’ U-turn on tuition fees in 2010, and the Conservatives’ healthcare reforms in 2012. Did decision-makers knowingly fail to respond to public opinion, did they misjudge voters’ reactions, and if the latter, why did those misjudgements occur? For all cases, evidence is presented that decision-makers misjudged voters’ responses to their decisions, in particular by under-estimating the potential salience of the decisions that they were taking. In two cases, decision-makers prioritised signals about public opinion that reinforced their existing policy preferences, in line with theories of motivated reasoning (Baekgaard et al., Citation2019). The results shed light on how findings from surveys about political decision-makers’ inability to accurately estimate public opinion play out in practise, and reinforce that unpopular government decisions are not always taken knowingly.

Theoretical Expectations

It is commonly expected that governments in office will respond to public opinion in order to maximise their chances of re-election. Their ability and willingness to respond to voters’ preferences are however constrained. Firstly – if we assume that political decision-makers and political parties are policy-seeking as well as office-seeking (Strøm, Citation1990; Wittman, Citation1983) – then it follows that they may resist responding to public opinion if they think that alternative policies would better serve the public interest. Scholars have identified that the tension between governing responsively and responsibly (Mair, Citation2009) also includes deprioritising public opinion in the face of international treaty obligations, existing policy decisions, international financial markets or the preferences of party donors. I define such actions as ‘rational unresponsiveness’, where decision-makers take unpopular decisions with an awareness of the electoral risks associated with them. In such cases, decision-makers will rationally try to minimise the electoral damage either by trying to persuade the public of the decision’s merits and taking it early in the electoral cycle (Canes-Wrone & Shotts, Citation2004; Lindstädt & Vander Wielen, Citation2011; Soontjens, Citation2022) or by only taking unresponsive decisions on matters that are of less salience to voters (Knecht & Weatherford, Citation2006; Soontjens, Citation2022).

The alternative is that given the growing evidence that political decision-makers are poor at estimating levels of public support for policies (Broockman & Skovron, Citation2018; Hertel-Fernandez et al., Citation2019; Walgrave et al., Citation2023), government decision-makers might take electorally damaging decisions unknowingly. Accurately gauging the likely reaction of voters to a policy-decision is trickier than estimating current levels of support for a policy. Opinion polls provide one obvious source of information, but decision-makers may face conflicting signals from qualitative public opinion research, discourse on social media, or ‘postbag’ correspondence (Herbst, Citation1998; Soontjens, Citation2020). They must also consider that voters may indicate a preference for policy but react negatively to the consequences of that policy decision. Further, the framing of a decision by media and opposition actors can affect its electoral outcomes in ways that decision-makers did not anticipate. For example, when former UK Chancellor George Osborne proposed raising VAT on pre-baked goods to bring it in line with tax on freshly cooked takeaway food he likely did not anticipate that opponents would successfully brand it a ‘pasty tax’ and force an embarrassing U-turn (Quinn, Citation2012). Further, if politicians are most concerned with voters’ preferences on more salient issues (Burstein, Citation2014), they must find a way to identify what issues really matter to voters amongst all the noise. In an environment rich with signals about voters’ preferences, decision-makers with limited attention time (Jones & Baumgartner, Citation2005) may struggle to accurately anticipate how voters will react to a decision.

These struggles may be exacerbated by various cognitive biases. People do not process information proportionately. Our perceptions and judgements are compromised by the use of heuristics and biased by similar decisions in the past, inertia, cues from those within our network or institution, and the framing of choices (Jones, Citation2001; Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979; Vis, Citation2019). Therefore, even though political parties in office have access to significant amounts of information about public opinion, decision-makers may fail to use such information to form accurate judgements about voters’ preferences. Qualitative studies of how legislators form judgements about public opinion have previously revealed that they rely on information other than opinion polls to anticipate voters’ reactions, whether that be the opinions of trusted colleagues (Petry, Citation2007), pressure groups (Herbst, Citation1998), or conversations with constituents (Kingdon, Citation1989).

Further, political actors’ judgements as to the electoral implications of policy decisions may be affected by their own evaluations of the utility of those policy decisions. Individuals interpret information either with the aim of accurately assessing the information, or to activate directional goals by trying to confirm a desired conclusion (Kunda, Citation1990). Seeking out or providing more weight to evidence which reinforces existing preferences is a phenomenon known as ‘motivated reasoning’ (Kunda, Citation1990). When forming judgements of the electoral consequences of a policy decision, the desired conclusion that politicians or advisers may be seeking to reach could relate to the goal of re-election. In such a case, we would expect decision-makers to process information with the aim of reaching an accurate conclusion about voters’ likely reactions. Alternatively, they may assess information with the aim of confirming their policy goals (Baekgaard et al., Citation2019). A political actor’s preference for a particular policy may trigger the use of motivated reasoning when encountering information indicating that enacting the policy will have negative electoral consequences.

Experiments have previously shown that politicians may engage in motivated reasoning to confirm their existing policy preferences (Christensen & Moynihan, Citation2020), including dismissing the views of an opposing constituent as being uninformed on a matter (Butler & Dynes, Citation2016), or strengthening their existing attitudes when presented with evidence that their preferred policy would lead to undesired outcomes (Baekgaard et al., Citation2019). Several studies have found that politicians in various countries assume that more voters share their policy preferences than is actually the case (Belchior, Citation2014; Clausen et al., Citation1983; Holmberg, Citation1999; Norris & Lovenduski, Citation2004; Pereira, Citation2021; Sevenans et al., Citation2023). However, little is known about whether motivated reasoning or other cognitive biases actually affect political actors’ calculations of likely electoral consequences during the policy-making process.

Case Study Selection

To investigate whether electorally damaging government decisions may be affected by decision-makers misjudging electoral reactions, I identified three case studies within which to examine decision-makers’ perceptions and motivations. This study follows in the tradition of using case studies to understand political actors’ perceptions in order to explain episodes of decision-making and produce more generalisable theories (Brady et al., Citation2004; Levy, Citation2008). The critical criteria for case selection was that cases should be examples of electorally damaging policies, to explore whether these were the result of a rational, or accidental, failure to respond to voters’ preferences. By ‘electorally damaging’, I refer not to all policy decisions that were polled as unpopular at the time or subsequently, but only those that harmed the electoral prospects of the party or parties who took them. Governments may take unpopular decisions on less salient issues that do not harm them electorally; this is not the focus of this study.

Electoral damage can be measured in one of several ways. Most obviously via a drop in either the governing party’s poll ratings, the party’s reputation in that policy area, or in the party’s reputation for a desirable attribute such as competence or trustworthiness as a result of the decision taken. Alternatively, studies may identify a particular issue as a significant factor in vote switching away from the governing party. To justify the case selection, the following section summarising the cases includes evidence of the electoral effects of the decisions.

I chose to avoid cases relating to economic or foreign policy on the basis that governments are more likely to behave ‘responsibly’ (Mair, Citation2009) in such areas. The cases chosen were decisions taken within 15 years of the start of the research project to allow for the possibility of interviewing protagonists involved in the decision. Within this time period, the cases differ in terms of having been taken by one of each of the three main UK parties (Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat), enabling the study to investigate whether there were patterns of behaviour that were consistent across different institutions or administrations.

Immigration Case

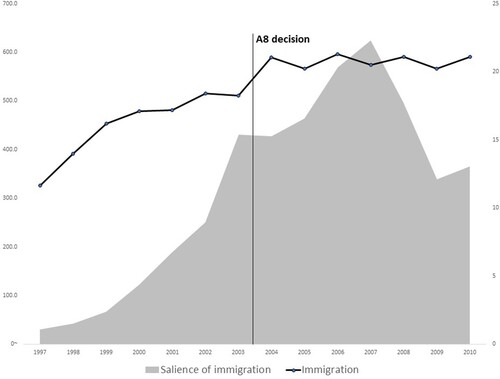

The first case concerns New Labour’s decision to allow migrants from the ‘A8’ nations (Eastern European countries joining the EU) the right to work in the UK in 2004. This was the most high-profile of several measures which contributed to a steady rise in immigration to the UK during Labour’s tenure in office (Consterdine, Citation2017). This increase in immigration, coupled with high profile failures of administration in asylum and immigration policy drove an increase in the salience of immigration among voters (Ford et al., Citation2015). highlights how the increase in immigration (line, left hand axis) after the 2004 A8 decision was followed by an increase in the proportion of voters citing immigration as the most important issue facing the UK (shaded area, right hand axis) around 2006 and 2007, seemingly in reaction to the increased level of immigration.

Figure 1. Levels of immigration to the UK and salience of immigration, 1997–2010. Sources: John et al. (Citation2013); ONS (Citation2018).

The A8 decision thus increased the salience of immigration, an issue that became an electoral weakness for Labour. Between 2005 and 2010 (when the Labour government lost power at a general election), immigration was the issue on which voters were most likely to trust the Conservative Party over Labour (Carey & Geddes, Citation2010). Further, it has been found that negative perceptions of Labour’s performance on immigration had a greater effect on Labour’s loss of support between the 2005 and 2010 election than perceptions on any other issue, including the economy (Evans & Chzhen, Citation2013).

Nhs Case

The second case is the Conservative-led decision to undertake an organisational reform of the NHS in 2012. Despite the Conservatives having promised during the 2010 election not to introduce any further ‘pointless reorganisations’ of the NHS (Timmins, Citation2012), once in office the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government announced plans to completely overhaul the structures of the NHS and controversially put competition at the heart of the NHS’s commissioning policies. These reforms were very much associated with the Conservative Secretary of State for Health Andrew Lansley, and were rejected by healthcare unions and by members of the Liberal Democrats at their Spring Conference in 2011 (Timmins, Citation2012).

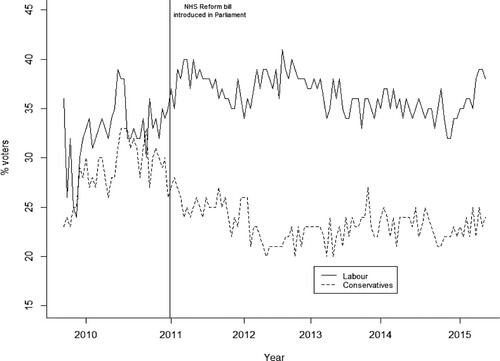

The reforms severely damaged the Conservative Party’s reputation for competence on healthcare. displays the proportion of survey respondents naming either the Conservatives (dashed line) or Labour (solid line) as being the best party to handle the NHS over the course of the coalition government. It shows that whilst during 2010 the Conservatives were often level-pegging with Labour, once the NHS reforms hit the headlines in early 2011 their reputation fell and never recovered. This thus satisfies the conditions of electoral damage by causing a decline in their reputation on a key issue. This was particularly significant since the Conservatives had expended so much effort between 2005 and 2010 into improving their reputation on their ability to look after the NHS (Kavanagh & Cowley, Citation2010).

Figure 2. Voters’ perceptions of which party would be best to handle the NHS, 2010–2015. Data: YouGov (Citation2015).

Tuition Fees

The third case is that of the Liberal Democrats’ notorious U-turn on tuition fees. Following the May 2010 general election, the Liberal Democrats entered into a coalition government for the first time. A year previously, the Labour government had launched the Browne Review into higher education finance which was largely expected to recommend an increase in university tuition fees. When the Review reported back in October 2010, the Liberal Democrat Cabinet Minister responsible for Higher Education proposed trebling tuition fees (Butler, Citation2021). This was despite all his party’s MPs having signed pre-election pledges not to vote for any tuition fees rise, and despite over a decade of Liberal Democrat campaigning to abolish tuition fees altogether and a recent history of electoral success in university constituencies linked to this campaign (Fieldhouse et al., Citation2006).

The party’s support among students dropped from 45% at the 2005 and 2010 general elections to just 15% at the 2015 election (Clarke et al., Citation2016; Cutts et al., Citation2010; Fieldhouse et al., Citation2006). The U-turn came to be seen by many voters as symbolising how the party abandoned its principles for power (Ashcroft & Culwick, Citation2015). Over half of undergraduate students claimed that it was still a factor for them in deciding whether to vote Liberal Democrat at the 2017 general election (Harrison, Citation2017). Given the importance of students to the Liberal Democrats’ electoral performance in 2010 (Cutts et al., Citation2010), the tuition fees decision clearly diminished support for the party among a key part of their electoral coalition.

Research Design

The subjects of this research project are the perceptions of decision-makers regarding how voters were likely to react to the case study decisions and the basis on which these judgements were made. To uncover this information, I consulted existing histories of the decisions supplemented by interviews with key decision-makers. Between April 2018 and July 2020 I conducted semi-structured interviews with politicians who took the decisions and their advisers. These interviews explored how decision-makers anticipated electoral reactions in these cases, and on what evidence those calculations were formed. Answers from interviewees were then analysed alongside evidence from other historical accounts of the cases, policy documents, available internal party communications and media reports. These sources of secondary evidence also served as a check on potential hindsight bias from the interviewees themselves. A full list of secondary sources reviewed is provided in the Online Appendix.

Interviewees were approached due to their known role in the decision-making process. In the immigration and NHS cases, I relied heavily on existing sources, particularly Timmins (Citation2012) and Consterdine (Citation2017) to identify key actors to approach. Despite the notoriety of the Liberal Democrats’ tuition fees U-turn, at the time of the project no detailed history had been written about the decision. This led to more interviewees being approached in that case since there was less initial clarity about which advisers and MPs were pivotal in the relevant decisions. In all cases interviewees recommended other actors to approach. I stopped seeking new interviewees once interviews failed to offer any additional insights as to how electoral reactions were anticipated.

In total, I interviewed 22 of the 35 political decision-makers who I approached, a 63% participation rate. A summary of the success of approaches by the role of participants and by the three cases is set out in . Generally, politicians were no less willing to participate than advisers. Approaches to decision-makers (particularly MPs) involved in the NHS case were less successful.

Table 1. Success of interview approaches.

Individuals identified as key in the decision-making process were approached via email or LinkedIn message and asked if they would be willing to participate in the research project. Interviews were usually conducted face-to-face in a venue of the interviewee’s suggestion and were recorded. Participants were given the opportunity to review excerpts quoted in the study. Disagreements between accounts were rare. Given the lack of buck-passing observed in the interviews, I am confident that the data gathered offers a relatively accurate account of decision-makers’ calculations of the anticipated electoral reactions towards different policy choices.

Questions focused on perceptions of electoral reactions at different stages in the process and what information interviewees could recall reviewing when forming their judgement of the likely electoral reaction. While there was some commonality in the themes of questions asked of interviewees, the fieldwork was conducted using an interactive strategy (Bergman, Citation2014) whereby answers in the initial interviews helped guide questions in later interviews as key points in each decision-making process became more visible. I sought to verify whether perceptions about electoral reactions recalled by earlier interviewees were shared by later interviewees whilst avoiding questions that prompted respondents with specific explanations for their behaviour or perceptions. The template interview script is provided in the Online Appendix, alongside examples of the questions posed in individual interviews.

Data from the interviews and relevant documents was coded to highlight information on the following major themes: the motivation behind the decision, the anticipated electoral reaction to the decision, and the justification or basis for the electoral reaction calculations. The coding process underwent several iterations as themes emerged from the data. The final list of major topic and sub themes codes is set out in .

Table 2. List of topic codes.

Findings

Were Electoral Reactions Anticipated?

In all three cases decision-makers claimed that they had not anticipated the electoral reactions that arose. In the tuition fees case, decision-makers were well aware of the immediate controversy surrounding their U-turn but believed that the anger would dissipate. The perception that voters would soon forgive the decision was mentioned by seven of ten interviewees (see also memoirs of then Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg, Citation2016, p. 33).

We thought that once people started to see access data there would be a grudging respect going, ‘Fair enough, you said that this was going to actually help not hinder poorer students going to university and you were right’. (Interview with former Adviser, 2018)

It’s like ‘How do airplanes get in the sky?’ People who fly don’t really care as long as they’re there, it’s the same with the NHS. We shouldn’t expect the public to engage with the details of the debate about the NHS. (Interview with former Adviser, 2019)

There was a very simple rubric: economic migration is a good thing, we just need to manage it and control it. Irregular migration and asylum-seeking are bad, particularly in the more right-wing heartland that New Labour was trying to maintain. Labour voting areas felt it as well. The reason it fell down was because that’s not actually how the world divided. (Interview with former Adviser, 2020)

Was Information About Likely Electoral Outcomes Overlooked?

Tuition Fees Case

Liberal Democrat decision-makers had access to information that signalled the potential electoral costs of their decision. Aside from their high support among students at the 2010 election, Liberal Democrat decision-makers knew from their own private polling prior to that election that their position on tuition fees was their second most popular policy (Interview with former Adviser, 2018) and therefore may have contributed to their strong performance. However, they persuaded themselves that since their manifesto front page had highlighted other policies, these were the policies which their supporters expected them to deliver in office (mentioned by five of ten interviewees).

Liberal Democrat decision-makers also persuaded themselves that they could electorally survive a U-turn on tuition fees as New Labour had done under Tony Blair when performing a similar U-turn on tuition fees in 2003.

What people didn’t understand enough was how long-term that was; I think partly because of what Blair had done on tuition fees where he had basically said that he wouldn’t increase them and then he had. There was some sense that ‘Well this will all be very hard in the short-term but we’ll weather through it’. (Interview with former Adviser, 2018)

The information about likely electoral reactions that Liberal Democrat decision-makers prioritised was that which reinforced their existing policy preferences. Despite the party’s long-standing policy commitment to abolish tuition fees, several senior Liberal Democrats MPs did not believe in the merits of abolishing tuition fees and had tried unsuccessfully to convince their party to drop the policy prior to the 2010 election (Clegg, Citation2016; Laws, Citation2016). Once in office, their conviction that tuition fees were a progressive way to fund higher education appears to have clouded their judgement regarding the electoral reaction to their U-turn on the issue.

NHS Case

Conservative Party polling prior to the 2010 election had revealed that mention of the phrase ‘reform’ in the context of the NHS was unpopular (mentioned by three interviewees, see also Timmins, Citation2012, p. 34).

The message was to offer reassurance on the NHS and be radical in nature on education because that’s what polling at the time showed voters wanted. (Interview with former Adviser, 2019)

Further, Lansley was committed to his reforms, which he had been working on since his appointment as the Conservatives’ Shadow Health Secretary in 2004 (Lansley, Citation2005; The Conservative Party, Citation2007). Lansley’s conviction in the merits of his reforms comes through strongly in previous scholarly accounts of the case (Jarman & Greer, Citation2015; Seldon & Snowdon, Citation2016; Timmins, Citation2012). This commitment to a plan may have biased Lansley to selectively process information about healthcare professionals’ support for the plans.

He honestly couldn’t understand why people didn’t see what he was trying to do. (Interview with former Adviser, 2019)

They had a lot of confidence in him and he had a pretty strong conviction that this would all be welcomed by the health service. (Interview, 2019)

Immigration Case

Although I found no evidence that the New Labour government had access to any data specifically on whether voters would support increased migration from Eastern Europe, decision-makers were aware of various signals that voters’ concerns about immigration were not limited to asylum seekers. A former adviser recalled internal party polling finding that ‘asylum and immigration’ was considered the most important issue facing the country by voters in summer 2000 (Owen, Citation2010), two and a half years before the A8 decision was taken (Consterdine, Citation2017). Around that time, New Labour’s Chief Pollster Philip Gould diary revealed that ‘polling in the autumn was miserable: there were doubts about trust and delivery, and an increased concern with asylum and immigration’, (Gould, Citation2011, p. 466). Deborah Mattinson, another New Labour pollster, recalled that immigration was a constant concern raised in focus groups throughout the New Labour government (Mattinson, Citation2010). Despite this evidence, New Labour governed with an acknowledgement of public concern about asylum but not about immigration (confirmed by all six interviewees). In part, this reflected the tabloid media attention on the administration of the asylum system rather than on economic migration. In the words of a former Home Office Minister:

The real absolute focus from the Prime Minister downwards was on being seen to reduce the number of illegal asylum seekers coming into the UK. In a sense there wasn’t much of a focus on immigration as a problem, and therefore I think across government there was an explicit acknowledgement that immigration was important in terms of the needs of employers and we had to strike a balance, but it wasn’t regarded as the problem because the problem was asylum at that point. (Interview with former MP, 2019)

Interviewees differed in their perspectives of how much these figures were unanticipated. David Blunkett, Home Secretary at the time of the decision, claimed that the Home Office did not believe the numbers in the report, whereas an adviser to then Prime Minister Tony Blair reflected that in the pressures of the decision-making environment, the headline figures were key to providing reassurance about the effects of the policy.

We didn’t use the figures. I’ve made a challenge to one or two researchers and journalists recently – find me a quote from a Minister using those figures – but nevertheless, we were wrong. We thought that it would be somewhere between there and 100,000, I don’t think any of us envisaged that it would be 140-150,000. (Interview with David Blunkett, 2020)

What I remember was looking at the forecast and thinking ‘Well that’s not very much, so this is not a big deal’ and giving that advice to Tony Blair. (Interview with former Adviser, 2020)

summarises the reasons why the electoral reactions were not anticipated in the three cases. In all three cases there was a clear misjudgement as to the potential salience of the decision or issue, whilst in the tuition fees and NHS cases there were also mistaken beliefs about how voters would react to the outcomes generated by these decisions.

Table 3. Summary of electoral misperceptions.

Discussion

Research has previously shown that political elites are poor at estimating public opinion in surveys (Broockman & Skovron, Citation2018; Dekker & Ester, Citation1989; Hertel-Fernandez et al., Citation2019; Holmberg, Citation1999; Norris & Lovenduski, Citation2004; Pereira, Citation2021; Walgrave et al., Citation2023) and this study has found that political elites were also poor at anticipating voters’ reactions when actually taking policy decisions. This demonstrates that these misperceptions can be consequential; it is not necessarily the case that poor judgements by some political actors cancel each other out, or that at some stage in the process key decision-makers respond rationally to information about voters’ preferences.

Instead, these misjudgements can contribute to governments taking electorally damaging decisions. In all three cases, decision-makers had access to information that could have alerted them to the potential electoral consequences of their decisions but chose to dismiss it in favour of signals that reinforced their existing policy preferences, or in the case of New Labour, in favour of the assumption that by tackling asylum they could assuage public concern about immigration. None of these decision were wholly irrational in the sense that they were taken with the primary aim of seeking electoral reward, they were all attempts at ‘responsible’ decisions motivated by perceptions of the country’s ‘best interests’. The irrationality lies in the failure to anticipate the negative electoral reactions and adopt strategies to mitigate these consequences.

Several patterns of note emerge from the data as to why politicians misjudged electoral reactions. Firstly, key decision-makers in the tuition fees and NHS cases prioritised information that reinforced their existing policy preferences. This is consistent with the action of motivated reasoning (Kunda, Citation1990) and confirms previous findings from surveys that politicians’ judgements of voters’ reactions are affected by motivated reasoning (Baekgaard et al., Citation2019; Butler & Dynes, Citation2016; Pereira, Citation2021). This demonstrates the importance for governments of having a diverse set of views represented during the decision-making process in order to overcome such bias in accurately judging voters’ likely reactions.

This need is particularly pronounced given the link between politicians’ areas of specialism and misperceptions of public opinion (Varone & Helfer, Citation2022). This may reflect that politicians’ personal policy preferences are of greater importance to them in policy areas that they consider more salient, and therefore they are more likely to activate directional goals when processing information about electoral preferences in such areas. In the context of the case studies examined in this paper, it may be the case for example that Andrew Lansley was a better judge of public opinion on issues other than the NHS, or that Liberal Democrats were better at anticipating voters’ reactions on issues other than education, and it was their attachment to their policy goals in these areas that affected their judgements of electoral reactions.

Arguably the most significant misjudgement in all three cases relates to the under-estimation of salience. Decision-makers may have been trying to act ‘responsibly’ and judged that voters would be relatively unconcerned about these decisions. Perhaps it is a more difficult judgement for decision-makers to judge how much voters will care about an issue rather than gauging what proportion of voters will support or oppose a decision, and future research into political elites’ perceptual accuracy should test the accuracy of decision-makers’ estimations of the salience of different policy issues.

Additionally, there was a common misperception that voters would judge parties on the outcomes produced by their decisions, rather than necessarily by the decisions themselves. Whilst voters do judge parties in power on the outcomes that their policies produce (Green & Jennings, Citation2017), they also perceive parties’ policy positional shifts, particularly on important issues (Plescia & Staniek, Citation2017), so it is odd for political elites to rationalise that they will primarily be judged on outcomes.

Further, decision-makers in the UK may be particularly prone to misjudgements given the limited attention that Ministers can give to their own and each other’s decisions given the centralisation of powers in the UK system (Dunleavy, Citation1995). Existing comparative research in this area has only compared the accuracy of politicians’ estimates of public opinion in federalised states (Walgrave et al., Citation2023) and confirmed that politicians are relatively poor judges of public opinion across different countries. Scholars in this area should also investigate whether politicians in more federalised and less centralised states are better able to accurately gauge public opinion.

Supplementary material

Download MS Word (27.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Gijs Schumacher, Barbara Vis, Rob Ford, attendees at a Utrecht University School of Governance seminar in 2019 and particularly Karolin Soontjens and Francesca Gains for their extremely helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chris Butler

Chris Butler is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Antwerp. His research focuses on how political elites conceive of, and respond to public opinion and how these judgements are affected by their backgrounds and by cognitive biases. E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Ashcroft, M., & Culwick, K. (2015). Pay me forty Quid and I’ll tell you. Biteback Publishing.

- Baekgaard, M., Christensen, J., Dahlmann, C. M., Mathiasen, A., & Petersen, N. B. G. (2019). The role of evidence in politics: Motivated reasoning and persuasion among politicians. British Journal of Political Science, 49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000084

- Balls, E. (2016). Speaking out. Arrow Books.

- Bardi, L., Bartolini, S., & Trechsel, A. H. (2014). Responsive and responsible? The role of parties in twenty-first century politics. West European Politics, 37(2), https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887871

- Belchior, A. M. (2014). Explaining MPs’ perceptions of voters’ positions in a party-mediated representation system: Evidence from the Portuguese case. Party Politics, 20(3), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811436046

- Bergman, M. (2014). 7 Quality of inferences in mixed methods research: Calling for an integrative framework. In Advances in mixed methods research. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857024329.d10

- Brady, H. E., Collier, D., & Seawright, J. (2004). Refocusing the discussion of methodology. In H. Brady & D. Collier (Eds.), Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards (pp. 3–21). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Broockman, D. E., & Skovron, C. (2018). Bias in perceptions of public opinion among political elites. American Political Science Review, 112(3). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000011

- Burstein, P. (2014). American public opinion, advocacy, and policy in congress: What the public wants and what it gets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Butler, C. (2021). When are governing parties more likely to respond to public opinion? The strange case of the Liberal Democrats and tuition fees. British Politics, 16(3), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-020-00139-3

- Butler, D. M., & Dynes, A. M. (2016). How politicians discount the opinions of constituents with whom they disagree. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12206

- Canes-Wrone, B., & Shotts, K. W. (2004). The Conditional Nature of Presidential Responsiveness to Public Opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 690–706. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519928

- Carey, S., & Geddes, A. (2010). Less is more: Immigration and European integration at the 2010 general election. Parliamentary Affairs, 63(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsq021

- Christensen, J., & Moynihan, D. (2020). Motivated reasoning and policy information: Politicians are more resistant to debiasing interventions than the general public. Behavioural Public Policy, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.50

- Clarke, H. D., Kellner, P., Stewart, M. C., Twyman, J., & Whiteley, P. (2016). Austerity and political choice in Britain. In Austerity and political choice in Britain, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137524935

- Clausen, A. R., Holmberg, S., & deHaven-Smith, L. (1983). Contextual factors in the accuracy of leader perceptions of constituents’ views. The Journal of Politics, 45(2), 449–472. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130134

- Clegg, N. (2016). Politics: Between the extremes. Penguin.

- Consterdine, E. (2017). Labour’s immigration policy: The making of the migration state. In Labour’s immigration policy: The making of the migration state. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64692-3

- Converse, P. E., & Pierce, R. (1986). Political representation in France. Harvard University Press.

- Cutts, D., Fieldhouse, E., & Russell, A. (2010). The campaign that changed everything and still did not matter? The Liberal Democrat campaign and performance. Parliamentary Affairs, 63(4), https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsq025

- Dekker, P., & Ester, P. (1989). Elite perceptions of mass preferences in The Netherlands; biases in cognitive responsiveness. European Journal of Political Research, 17(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1989.tb00210.x

- Dunleavy, P. (1995). Policy disasters: Explaining the UK’s record. Public Policy and Administration, https://doi.org/10.1177/095207679501000205

- Dunleavy, P., & Ward, H. (1981). Exogenous voter preferences and parties with state power: Some internal problems of economic theories of party competition. British Journal of Political Science, 11(3), 351–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400002684

- Elmelund-Præstekær, C., & Emmenegger, P. (2013). Strategic re-framing as a vote winner: Why vote-seeking governments pursue unpopular reforms. Scandinavian Political Studies, 36(1), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2012.00295.x

- Evans, G., & Chzhen, K. (2013). Explaining voters’ defection from labour over the 2005-10 electoral cycle: Leadership, economics and the rising importance of immigration. Political Studies, 61(SUPPL.1)), https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12009

- Fieldhouse, E., Cutts, D., & Russell, A. (2006). Neither north nor south: The liberal democrat performance in the 2005 general election. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/13689880500505306

- Ford, R., Jennings, W., & Somerville, W. (2015). Public opinion, responsiveness and constraint: Britain’s three immigration policy regimes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(9), https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1021585

- Gould, P. (2011). The unfinished revolution: How new labour changed British politics for ever. Abacus.

- Green, J. & Jennings, W. (2017) The politics of competence: Parties, public opinion and voters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, E. (2017). Election 2017: Will the Liberal Democrats win over young voters? BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2017-39952676

- Herbst, S. (1998). Reading public opinion. University of Chicago Press.

- Hertel-Fernandez, A., Mildenberger, M., & Stokes, L. C. (2019). Legislative staff and representation in congress. American Political Science Review, 113(1). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000606

- Holmberg, S. (1999). Wishful thinking among European Parliamentarians. In Political representation and legitimacy in the European Union. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198296614.003.0011

- Jacobs, L.R. & Shapiro, R.Y. (2000) Politicans don't pander. University of Chicago Press.

- Jarman, H., & Greer, S. L. (2015). The big bang: Health and social care reform under the coalition. In The conservative-liberal coalition: Examining the Cameron-Clegg Government. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137461377_4

- John, P., Bertelli, A., Jennings, W., & Bevan, S. (2013). Policy agendas in British politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, B. D. (2001). Politics and the architecture of choice. University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. University of Chicago Press.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185. ISSN 0012-9682.

- Karremans, J., & Lefkofridi, Z. (2020). Responsive versus responsible? Party democracy in times of crisis. In Party politics (Vol. 26, Issue 3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761199.

- Kavanagh, D., & Cowley, P. (2010). The British General Election of 2010. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kingdon, J. W. (1989). Congressmen’s voting decisions: Third Edition. University of Michigan Press.

- Knecht, T. M., & Weatherford, S. (2006). Public opinion and foreign policy: The stages of presidential decision making. International Studies Quarterly, 50(3), 705–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00421.x

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

- Lansley, A. (2005). Speech to the NHS Confederation: The future of health and public service regulation. https://conservative-speeches.sayit.mysociety.org/speech/600287

- Laws, D. (2016). Coalition: The inside story of the conservative-liberal democrat coalition. Biteback Publishing.

- Levy, J. S. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940701860318

- Lindstädt, R., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2011). Timely shirking: Time-dependent monitoring and its effects on legislative behavior in the U.S. Senate. Public Choice, 148(1–2), 119–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9649-y

- Mair, P. (2009) Representative versus responsible government, MPIfG Working Paper, No. 09/8, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne.

- Mattinson, D. (2010). Talking to a brick wall: How new labour stopped listening to the voter and why we need a new politics. Biteback Publishing.

- Norris, P., & Lovenduski, J. (2004). Why parties fail to learn: Electoral defeat, selective perception and British Party Politics. Party Politics, 10(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068804039122

- ONS (2018) Dataset: Long-term International Migration 1.01, components and adjustments, UK. Retrieved October 5, 2019, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/datasets/longterminternationamigrationcomponentlsandadjustmentstable101.

- Owen, E. (2010). Reactive, defensive and weak. Prospect Magazine, 15–16.

- Pereira, M. M. (2021). Understanding and reducing biases in elite beliefs about the electorate. American Political Science Review, https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100037X

- Petry, F. (2007). How policy makers view public opinion. In Policy analysis in Canada: The state of the art. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442685529-017

- Plescia, C., & Staniek, M. (2017). In the eye of the beholder: Voters’ perceptions of party policy shifts. West European Politics, 40(6), 1288–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1309623

- Quinn, B. (2012). A brief history of the pasty Tax, The Guardian, 29 May. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/may/29/pasty-tax-brief-history

- Salmon, P. (1993). Unpopular policies and the theory of representative democracy. In A. Breton, G. Galeotti, P. Salmon, & R. Wintrobe (Eds.), Preferences and democracy. International studies in economics and econometrics (Vol. 28). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-2188-0_2

- Seldon, A., & Snowdon, P. (2016). Cameron at 10: The Verdict. William Collins.

- Sevenans, J., Walgrave, S., Jansen, A., Soontjens, K., Brack, N., & Bailer, S. (2023). Projection in politicians’ perceptions of public opinion. Political Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12900

- Smith, P. (1991). Lessons from the British poll tax disaster. National Tax Journal, 44(4), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41788932

- Soontjens, K. (2020). The awareness paradox: (Why) politicians overestimate citizens’ awareness of parliamentary questions and party initiatives. Representation, https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1785538

- Soontjens, K. (2022). Inside the party’s mind: Why and how parties are strategically unresponsive to their voters’ preferences. Acta Politica, 22, 731–752. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00220-9

- Straw, J. (2012). Last man standing. Pan Books.

- Strøm, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 34(2), 565–598. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111461

- The Conservative Party. (2007). NHS autonomy and accountability: Proposals for legislation. http://www.nhshistory.net/NHSautonomyandaccountability.pdf

- Tiggle, N. (2010) GPs ‘uncertain if NHS shake-up will benefit patients’. BBC News, 7th October. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-11488780

- Timmins, N. (2012). Never Again? The story of the Health and Social Care Act. Institue for the Government, The King’s Fund.

- Vargas-Silva, C. (2011). Lessons from the EU eastern enlargement: Chances and challenges for policy makers. CESifo DICE Report, 9(4), 9–13.

- Varone, F., & Helfer, L. (2022). Understanding MPs’ perceptions of party voters’ opinion in Western democracies. West European Politics, 45(5), 1033–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1940647

- Vis, B. (2019). Heuristics and political elites’ judgment and decision-making. Political Studies Review, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929917750311

- Vis, B., & Van Kersbergen, K. (2007). Why and how do political actors pursue risky reforms? Journal of Theoretical Politics, 19(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629807074268

- Walgrave, S., Jansen, A., Sevenans, J., Soontjens, K., Pilet, J. B., Brack, N., Varone, F., Helfer, L., Vliegenthart, R., van der Meer, T., Breunig, C., Bailer, S., Sheffer, L., & Loewen, P. J. (2023). Inaccurate politicians: Elected representatives’ estimations of public opinion in four countries. The Journal of Politics, 85(1), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1086/722042

- Wittman, D. (1983 March). Candidate motivation: A synthesis of alternative theories. American Political Science Review, 77(1), 142–157. (1989). Why democracies produce efficient results. Journal of Political Economy, 97. 6 (December), 1395–1424. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956016

- YouGov. (2015). Best Party on Issues Tracker. YouGov. https://d25d2506sfb94s.cloudfront.net/cumulus_uploads/document/9drub35(7f/YG-Archives-Pol-Trackers-Issues(1)-Best-Party-on-Issue-270415.pdf.