ABSTRACT

There has been considerable focus on the widespread destruction of cultural heritage in Afghanistan since the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001 and much concern over the future for heritage in the region on the return of a Taliban regime in 2021, yet comparatively little has been written on the fate of Afghanistan’s national collection of paintings, manuscripts, and works on paper. Through a quasi-experimental study and using a combination of evaluation methodologies, this paper discusses whether the overall impact achieved in conservation capacity-building and training schemes in conflict zones justify the cost and risk of operating in such regions. Using an international collaborative conservation training course carried out in 2020 at the Afghan National Gallery in Kabul as a case study, it discusses the appropriateness and effectiveness of the signature pedagogies in conservation when working in a conflict scenario, and highlights the limitations present in conservation training programmes in post-conflict scenarios and the need for sustainability of such programmes. The results of the study found that common constructivist-focused, Eurocentric conservation pedagogies may not be effective for training museum professionals in regions where this approach is unfamiliar.

Introduction

Destruction of cultural heritage has a long history of being used as a means by which to assert control, as a bargaining tool, or as political propaganda (Viejo-Rose Citation2007; Stone Citation2015; Brosché et al. Citation2017). However, cultural heritage and its wilful destruction have been placed in sharp focus in recent years due to the widespread media coverage of destruction and looting of important cultural heritage sites in Mosul and Palmyra in Iraq in 2014 by Daesh/ISIS (Hassan Citation2015), and the sixth and seventh century Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001 (Grissmann Citation2006; Harrison Citation2010; Leslie Citation2014). The unprecedented media coverage of the destructive acts of extremist groups in recent years has been both advantageous and disadvantageous in bringing attention to the lack of provision for securing significant cultural heritage sites and collections in regions of active conflict. The impact of such media coverage is often a strong outpouring of support and condemnation from the public, which foster a number of international conservation initiatives. While, arguably, this has created the perception that risk to cultural heritage in conflict zones is confined to dramatic, intentional acts of destruction and looting, and less so on the impact of political instability, lack of literacy and education, and the effect of untrammelled urban development on heritage sites (Guzman et al. Citation2018; Gerstenblith Citation2009), robust international condemnation has enabled high impact conservation initiatives that have been designed to predict and protect heritage at risk in the future. A significant part of this has been the training of local conservators by museum professionals and educators from Europe and the USA. Despite overwhelmingly positive outcomes, the sustainability and long-term impact of these interventions is difficult to evaluate and the development and implementation of effective and appropriate pedagogical approaches for the provision of conservation and collections care education in active and post- conflict zones is under-researched.

Background

Afghanistan has a rich and troubled history. Despite immense progress in infrastructure, culture, and civil society though international development initiatives since 2001, the future of the region remains uncertain after the chaotic exit of international forces and the swift takeover of the country by a resurgent Taliban in 2021. Elimination of poverty and hunger, the provision of security, and the establishment of effective and stable governance were, and remain, primary concerns (Fitzgerald and Gould Citation2009; Yamin Citation2013). At the time of writing, the withdrawal of US and international troops from Afghanistan, the lack of effective governance and economic control, and the freezing of assets has led directly to an imminent humanitarian crisis. Increasingly frequent insurgent attacks, concerns for the position of women and girls in a post-withdrawal society, and widespread discrimination against non-Pashtun ethnic groups and Afghans who previously worked with foreign bodies all represent ongoing concern for the future stability of the region (Akseer and Rieger Citation2019).

Invaded by Soviet Russia in 1979, Afghanistan became a proxy battleground for the primary actors of the Cold War. The Mujahadeen, supplied in arms and support by the US, helped bring about the end of the 10-year Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, yet left the region destabilised politically and economically. The vacuum that was left ushered in a destructive civil war, quickly followed by the short but brutal reign of the Taliban and the imposition of an extreme and restrictive form of Sharia Law across the country. During more than forty years of conflict, an estimated one million Afghans were killed, and half the population was displaced, largely fleeing to Pakistan or Iran. In 2020, refugees from Afghanistan represented the third largest refugee group in the world by country of origin (below Venezuela and the Syrian Arab Republic), and this has been a sobering trend since the 1980s (UNHCR Refugee Data Citation2020). Despite large international investment and a recovering economy between 2001 and 2021, Afghanistan is still considered a country of low human development, ranked 168 out of 189 world countries on the Human Development index by the UNHCR (UNHCR Citation2020).Footnote1

Heritage destruction in Kabul

Long before the destruction at Bamiyan, the country’s cultural heritage was profoundly affected by civil war. By some estimates, by the time of the invasion of the US-led coalition in 2001, in the region of 70% of the national museum’s collection was lost, looted, or destroyed and countless historic sites were damaged (Dupree Citation2006). The Afghan National Gallery (ANG) and National Museum were both damaged and looted throughout 1993–1996, during the period of Mujahedeen interfighting in Kabul, where both buildings were on the front lines of the conflict.Footnote2 Jolyon Leslie, a founder member of the Society for the Protection of Afghan Cultural Heritage (SPACH), was witness to the destruction in Kabul in the 1990s and observed the looting of the National Museum first hand and warned of the promises given to protect heritage by those in command: ‘Between each of our visits, Mujahedeen fighters returned to loot, despite assurances from commanders who controlled the area that they would intervene to prevent this. The objects that we saw for sale on the roadside on the way back to the city after such visits, brought home to us that our appeals had fallen on deaf ears’ (Leslie Citation2014).

At the time, many paintings in the national collection were saved by being removed from their frames, rolled up, and hidden by staff. Others were removed to the National Palace, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and elsewhere. A catalogue of the collection prior to the destruction, (if it existed at all) did not survive, and so the extent of the loss is difficult to gauge. Losses at the National Museum, which was shelled during the conflict, were much larger, much worse, and more significant. Much of the core collection, however, was removed and stored in central Kabul. It survives today thanks to quick thinking staff. An important collection of early Qur’ans, manuscripts, and miniature paintings were removed and stored at the National Archives, where they remain today. Like the National Gallery, it is difficult to gauge how much of the National Museum collection has been lost through neglect, theft, or destruction. Inventory catalogues that survived the collapse of the building were destroyed, and paper records, furniture, and carved wooden sculptures were burnt. Militias looted what remained of the collection to sell on the black market and although international efforts to return stolen artifacts have had some success, much of the collection remains missing (Grissmann Citation2006).

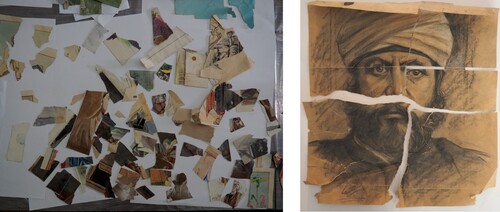

Further deliberate destruction at the ANG and the National Museum occurred in 2001, where figurative sculptures, paintings, and film considered to be idolatrous were amongst objects destroyed by local Taliban commanders in KabulFootnote3 (). Again, many objects survived thanks to the quick thinking and bravery of curators and archivists. Staff hid objects from the National Museum (Smith Citation2008), and much of the collection of the Afghan National Film Institute survived when staff hid original Afghan films behind a false wall, substituting them with low quality copies of Indian and American films, which were promptly burned (Nasr Citation2019). At the ANG, figurative easel paintings were removed from frames and stretchers and hidden in attics and sometimes beneath the gallery carpets. In perhaps the most remarkable act of bravery, local doctor and artist, Mohammad Yousef Asefi, spent weeks in the stores of the ANG, painstakingly painting over human figures and other perceived offensive elements in paintings, using reversible gouache paint (), and saving 122 paintings from the bonfire and the knife (Asefi Citation2019). Not all objects could be hidden, and the gallery’s large collection of print, drawing, and watercolour portraits, which had remained on display or in storage, were almost all torn to pieces.Footnote4

The overarching motivations that lie behind cultural heritage destruction during conflict are complex, and while some authors have attempted to explore motives or provide systematic typologies of destruction (Brosché et al. Citation2017; Viejo-Rose Citation2007), the subject remains under-researched. In the context of Afghanistan however, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas and the actions of Daesh/ISIS in Iraq and Syria in 2014 fostered a general discourse in the international media that it was the cultural ideology of the Taliban that was entirely responsible for widespread heritage destruction in the region. Yet as pointed out above, much of the worst destruction, looting, and deliberate neglect of heritage sites and objects occurred before the Taliban first came to power. Indeed, prior to the imposition of a more radical policy on heritage in 2001, the Taliban initially assisted in the protection of Afghan heritage sites and collections (Harrison Citation2010). UN operatives in Kabul were in frequent contact with the Taliban authorities between 1996 and 2000 on policies for protecting cultural property and on the issue of the Bamiyan Buddhas. Prior to 2001, the Buddhas were under the protection of the regime, viewed by Taliban leaders as having no idolatrous status, since the site was not a place of religious worship and Buddhism was no longer practiced in the country. With the support of the Taliban Minister of Culture, the UN, working together with SPACH, negotiated the secure storage and protection of the National Museum collections and much of the national collection of paintings (Grissmann Citation2006; Jolyon Leslie. Personal communication, 2020). It may be prudent to point out that since 2001, it has been politically expedient to underemphasise the wilful destruction and neglect of cultural heritage that occurred in the ten years prior to Bamiyan, in favour of focusing the narrative on the actions of the Taliban (and correlating these with those of Daesh/ISIS) as a way to promote soft diplomacy and to secure foreign funding for preservation and reconstruction projects. Nonetheless, it is fair to say that events between 1992, when Soviet forces left the country, and 2001 when the Taliban was overthrown by NATO forces, can be considered a monumental disaster for the country’s cultural heritage.

Soft diplomacy and limitations for conservation interventions

Cultural heritage is seen as an important contributor to soft diplomacy in relations between developed countries and active and post-conflict zones, and the visibility of cultural diplomacy is regarded as having a key role in public diplomacy for the enhancement of international relations (Harrison Citation2010; Luke and Kersel Citation2013). However, there is a challenge in accurately assessing the long-term impact of such diplomacies, and several authors have pointed out the problematic nature of conceptualising a shared global heritage to promote diplomatic relations (Harrison Citation2010; Klimaszewski, Bader, and Nyce Citation2012; Kersel and Luke Citation2015). It is notable, for example, that the protection of cultural heritage was cited as a key outcome to promote both the invasion of Iraq in 2000 and of Afghanistan in 2001. Indeed, the United Nations Security Council Resolution S/Red/1333, which imposed a number of far-reaching sanctions on the Taliban and Al Qaeda in 2000 explicitly cites ‘ … respect for Afghanistan’s cultural and historical heritage’ as an affirmation of the resolution (United Nations Security Council Citation2000). The negative effect of such sanctions on the provision of much-needed humanitarian aid have been widely reported (Ahmad Citation2001; Khabir Citation2001; Martin and Enderby Smith Citation2021).

Klimaszewski and colleagues have also noted that while heritage protection projects may aim to have wide impact and diplomatic efficacy, the central idea of a global shared heritage is predicated on assumptions made by those in power and may not always have the desired impact. Local community views are multi-faceted, and conservators and other heritage professionals engaged in post-conflict projects may not always have an informed and nuanced view of the forces that construct and divide a community (Klimaszewski, et al. Citation2012). Community engagement as a critical component of heritage conservation projects is widespread today in a way it was not in the past, but at the same time ethnic, social, economic, and other concerns are often unique to a particular demographic. Generic policies about how and what heritage should be preserved are not necessarily appropriate for all. To paraphrase Klimaszewski and colleagues – in Afghanistan, an ethnic Pashtun and an ethnic Tajik may have radically different perceptions of history and culture.

As noted, the impact of heritage projects is difficult to predict and assess. It is possible at the same time to engage community stakeholders in conservation and preservation decisions and acknowledge that there are multiple histories and voices that dictate how the past is seen and interpreted, while simultaneously and implicitly projecting the idea that ‘the West knows best’ (Kersel and Luke, Citation2015). This is especially true where projects are designed with well-intentioned and well-defined outcomes but are directed by one partner – typically the one providing the funds. At best this creates an imbalance where the developing country/conflict zone receives minor monetary and strategic advantage, but where the economically larger partner receives diplomatic power and influence (Klimaszewski, et al. Citation2012). At worst, misjudged cultural diplomacies may lead unintentionally to catastrophic consequences. International pressure and the promotion of the concept of shared global heritage were undoubtedly a key modifier in the Taliban’s decision to reverse previous promises and carry out the wilful destruction of heritage in 2001 (Harrison Citation2010).

A key limitation for conservation interventions in Afghanistan is that Afghans in general have little or no concept of this global shared heritage. Heritage is rarely considered to be of national importance, particularly when stacked against the more present, much larger concerns over security, food, poverty, education, and health. Although the recent re-opening of the National Museum is a positive step forward, heritage in the post-withdrawal era can only be seen by the majority of Afghans as a luxury and of minimal importance in the present climate Footnote5 (Becatoros Citation2021). Even prior to the catastrophic withdrawal of international forces in 2021, an incorruptible police force, humanitarian aid, a stable economy, and the installation of basic, modern infrastructure and facilities were a very real preoccupation for the population. In post-conflict recovery, as Stanley-Price rightly points out, it is difficult to quantify the immediate benefits of spending significant amounts of money on heritage preservation projects when compared with the building of a hospital or creating a reliable, consistent electricity supply (Stanley-Price Citation2005). Furthermore, cultural heritage education that might help to provide a national sense of cultural ownership is practically non-existent, even in the more educated urban regions. Cultural heritage was not included in any meaningful way in the general school curriculum, schools did not visit heritage sites, and few adults visited the National Museum, National Archives, or National Gallery. The connection between identity and heritage in Afghanistan is also complex. Cultural identity in the region is connected more to political, ethnic, and tribal affiliation rather than to a sense of national pride derived from a universally-owned heritage (Dupree Citation2006; Caesar and Rodriguez García Citation2006). The Ministry of Information and Culture, while supportive of heritage initiatives in general, was, and is, critically understaffed and underbudgeted.

Without education to place objects of other cultures in context with their own, many Afghans do not see cultural objects as art, and the idea that cultural heritage can be part of a solution to solve decades of conflict and distrust is difficult to understand. This is an important consideration, as education for the Afghan public is essential to foster understanding of conservation and what it can mean for what remains of the rich cultural heritage of the region. The National Museum in Kabul has been regarded as a powerful symbol of Afghanistan’s recovery, but it is uncontroversial to state that the majority of Afghans know little about the collection. As Leslie points out, the Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum exhibition that was toured internationally in 2014, and displayed in high profile museums in New York, London, and many other cities, has led to a situation where people in the US, Europe, and UK are much more familiar with items in Afghanistan’s national collection than are the people of the region (Leslie Citation2014). Isakhan and Meskell have similarly argued that UNESCO’s mission to revive the spirit of Mosul in Iraq and reconstruct the old city after the destruction wrought by Daesh/ISIS in 2014 relied on ‘problematic assumptions about how the local population value and engage with their heritage, how they interpret its destruction and the value they place on its reconstruction’ (Isakhan and Meskell Citation2018).

Corruption is also acknowledged as a major issue for international heritage projects in Afghanistan, at present ranked at 165 out of the 180 most corrupt countries in the world (Corruption Perception Index Citation2020). A total of 83.7% of participants in a 2019 Asia Foundation survey believed corruption is a significant problem for the region, and a quarter of Afghan citizens stated that they experienced corruption or bribery in 2020 (Akseer and Rieger Citation2019). Prior to the 2021 withdrawal, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicator for 2017 showed that Afghanistan is among the world’s 10 worst performers in terms of government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption (Bak Citation2019). In 2019, bribery was considered to be endemic and considered a normal part of applying for jobs, interacting with government bodies, and for admission to schools and universities (Akseer and Rieger Citation2019). Despite an encouraging move by the present administration toward modernisation, it remains to be seen how the resurgent Taliban, even if recognised as a legitimate government, will tackle such persistent problems.Footnote6

The number of NGOs working in Afghanistan increased greatly in the years after the 2001 fall of the Taliban, and more recently these have included several that focus specifically on cultural heritage.Footnote7 However, many Afghans are somewhat sceptical about the role of both national and international NGOs (Mitchell Citation2017). While overall impact has been strong, there is a great deal of scepticism about international educational programmes in Afghanistan, specifically focused on where international aid money is spent. Michell notes that by 2010, Kabul was swamped with a number of short training courses provided by various donors and organisations – many of which were criticised for being superficial, supply-driven, and uncoordinated. Additionally, this kind of training was rarely independently evaluated, and typically conducted without a baseline, making it difficult to assess its impact (Mitchell Citation2017). Cultural heritage projects, particularly for historic sites and monuments, have largely had positive outcomes, but there remain examples of short-sightedness. The Afghan National Archives, for example, received a large and valuable supply of conservation materials from the UK in 2007, yet were not given instruction in what these were, or how they should be used with the collection, and the materials have remained unopened since they were delivered (Anonymous Citation2020). Viejo-Rose has observed that while NGOs and foreign governments are often called upon to reconstruct, restore, and recalibrate cultural heritage in post conflict regions, it is rare that local communities are consulted, and these interventions can often ‘adopt a paternalistic role, with echoes of colonialism’ (Viejo-Rose Citation2007). Barakat echoes this view and notes that there is inherent risk that ‘imported and externally imposed models ignore the two most basic needs for humans in the aftermath of conflict: to reaffirm a sense of identity and regain control over one’s life’ (Barakat Citation2005). While intentions are good and local scepticism may be unfounded, short-term conservation interventions can nonetheless be met with some suspicion in the region.

Conservation training in Afghanistan

Over the last 20 years, a large number of NGO, international government, and foundation-driven capacity-building and educational projects have taken place in developing countries and post-conflict zones to train local conservators. Notable interventions in Iraq (Pearlstein and Johnson Citation2020), Myanmar (Henderson et al. Citation2021), India (Seymour et al. Citation2019; Haldane et al. Citation2012), Afghanistan (Cassar and Nagaoka Citation2007; Stein Citation2017; Boak Citation2019) and the Central Asian republics (Stein Citation2019) have yielded strongly positive impacts.Footnote8 In Afghanistan, organisations such as the Afghan Cultural Heritage Consulting Organisation (ACHCO), and the Society for the Preservation of Afghan Cultural Heritage (SPACH) have a long history of implementing heritage projects for both collections and archaeological sites which have incorporated training of local Afghans. Early Buddhist wall paintings in the network of caves behind the niches in Bamiyan where the Buddhas once stood, continue to be the subject of a significant conservation and educational campaign (Maeda Citation2006), and the formation of the Turquoise Mountain School in Kabul in 2006 may be viewed as a model of how the training of local Afghans in traditional artisan crafts such as stone carving and manuscript painting can have a significant and sustainable impact on cultural heritage in the region, while providing income for local communities.Footnote9

Some authors, however, have cautioned against the privileging of elite, expert, and Eurocentric knowledge over local sources, particularly on the preservation of monumental heritage (Barakat Citation2005; Stanley-Price Citation2005; Nankivell Citation2016). In an Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) study of media coverage of heritage destruction in Iraq and Syria, Nankivell found that Western experts and institutions were quoted or referred to nearly 2.5 times more than Iraqi or Syrian experts or institutions, and that where they were cited, the truthfulness and validity of statements by locals and government officials were questioned or required confirmation from another source (Nankivell Citation2016). Perhaps more importantly, others highlight the danger of equivocating the loss of heritage with the loss of people and living culture, and the reinforcement of more dominant, Western discourses in heritage (Chulov Citation2015; Hassan Citation2015; Fredheim and Khalaf Citation2016). While educating conservators with little or no background in the subject may require the teaching of the foundational principles of modern conservation, the pedagogical approaches typically used in Eurocentric conservation courses may be difficult and unfamiliar to those unused to these forms of learning.

Conservation education in Afghanistan. HUNAR: A case study

Heritage Unveiled: National Art Restoration (HUNAR) was one of three heritage conservation projects funded by the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund and implemented by a partnership between the Foundation for Culture and Civil Society (FCCS) and Sayed & Nadia Consultancy at the Afghan National Gallery, part of the Ministry of Culture and Information of the Afghan Government. A 2018 field study in Kabul by the project team surveyed the damaged collection at the ANG and identified 50 easel paintings and works of art on paper in need of urgent conservation. These were fully conserved during a second phase in 2019, which also brought conservation materials from the UK to build and equip modular paintings and works on paper conservation studios in Kabul.

A key objective for the HUNAR programme in 2020–2021 was to address the lack of skills and knowledge in heritage management and conservation in Afghanistan. This included the design and implementation of a simple collections management database at the ANG, the translation of key conservation sources on paper and easel paintings conservation into Dari and Pashto, and an intensive training course for participants from the National Gallery, National Museum, National Archives, Kabul University, the Art Institute, and four provincial galleries. The training took the form of a short, ten-day course on the theory and practice of collections management, conservation, artists’ materials and techniques, and preventive conservation to be carried out in situ in Kabul in 2020. However, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic and a worsening security situation in Kabul meant that travel to the region was not possible, and the training was moved online. The course was provided via recorded lectures with live translation, followed by a live online ‘Q&A’ session with all participants. A small group of high-scoring trained participants were then selected to travel to regional galleries at Kandahar, Herat, Balkh, and Nangarhar to train local staff in condition reporting and basic collections management.

Social and gender inclusion was promoted strongly throughout the project. As with most sectors in Afghanistan, there are structural inequalities that make accessing decision-making and leadership roles in the heritage sector difficult. In most provinces there are no female employees in the sector. HUNAR was the first project of its kind to carry out a formal gender and social inclusion assessment for the heritage sector in the region. In Afghanistan, a clear international sustainable development goal is to promote the empowerment of young women (Wimpelmann Citation2017), and the inclusion of heritage in the international development agenda represented a significant opportunity to re-appraise the role of women in contemporary Afghanistan, especially since women are over-represented in higher education art and design courses, the traditional entry route into heritage roles (Hashimi Citation2021). The Ministry of Culture employees 2023 people, of which 14% are female. However, the vast majority work in the capital. The ratio is almost non-existent in the provinces, where in general there is also very low education attainment for women. While female heritage workers report little workplace gender discrimination (salary scales are the same for both men and women), widespread corruption means that overtime and favouritism are widespread. Ethnically, the majority of workers in heritage positions are Tajiks (63%), followed by Pashtun (26%), Hazara (7%), Uzbeks (2%), and others (3%). This, at least, is consistent with proportional distribution of ethnic groups around the country (Afghan Ethnic Groups Citation2011). In the conservation training component of the HUNAR project, the participant balance was 60/40 male/female in Kabul and 82/18 in the provincial galleries (Hashimi Citation2021).

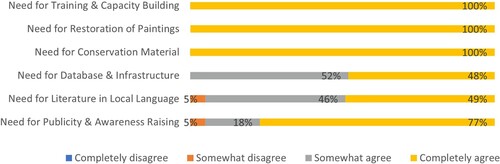

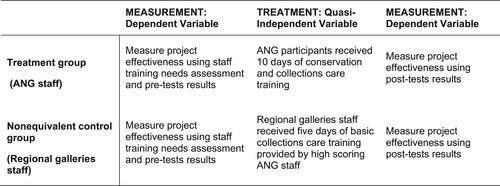

A needs assessment was carried out via simple gap analysis and an anonymous needs survey completed by all participants prior to the project. Given the low baseline, gap analysis between present knowledge and skill in the region and that of an ideal target situation (for example, in a conservation department in a UK museum) was of limited use. Unsurprisingly, in the needs analysis survey, 100% of respondents cited the need for training and capacity building in the region as a priority, along with the restoration of conflict-damaged paintings and the need for quality conservation materials (). Overall impact for the training was assessed by a peer-reviewed impact evaluation report carried out in 2021 by S&N Consultancy. The impact evaluation took place following an established quasi-experimental design, where both a comparison and control group both received training, but with different durations and methods. Quasi-experimental designs offer an opportunity to gather causal evidence where a randomised control trial (RCT) is impossible or impractical to implement. In this context, data from a comparison group that is as similar as possible to the intervention group is captured via a counterfactual scenario (what the outcome would have been had the project/intervention not been implemented). While controlled trials remain the ‘gold standard’ for impact studies, several authors have outlined the distinct advantages of quasi-experimental studies over RCTs, particularly where rapid impact evaluation is required (White and Sabarwal Citation2014; Campbell et al. Citation2017).

For HUNAR, comparative data on participants’ performance before and after training was calculated using a scenario-based counterfactual in order to provide a rapid, meaningful impact assessment. Programme stakeholders were asked to assign a number to different parts of the project, and these were compared to assess the total impact of the project. The data from the non-equivalent control group was drawn from the participants from the four regional galleries after they were trained by the highest scorers from the original treatment group. Criteria for measuring pre- and post-assessment is shown in (Hashimi Citation2021). To establish the overall net impact, project stakeholders were asked to assess both the effect of the programme and the effect of a scenario-based counterfactual alternative (an ideal programme). The impact evaluation was based on probability that the project would have the desired outcome. Overall, general conclusions showed that there was an increase efficiency in ANG staff work practices of 86%, particularly through practical workshops, exposure to previously unknown international standards in conservation and preservation, and through the use of a written resource library in local languages (Hashimi Citation2021).

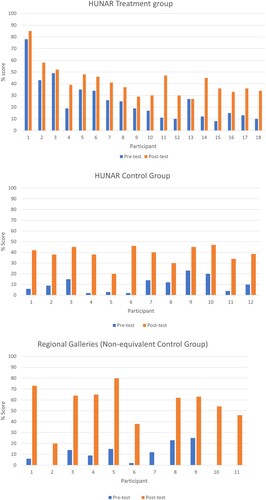

Figure 4. HUNAR: Treatment group and non-equivalent control group pre-test/post-test measurement (Hashimi Citation2021).

To assess the overall impact of the conservation training programme, participants were asked to complete a short test before the training in order to demonstrate their baseline knowledge, and then again after the training. Overall, the progression from the pre-course test to the post-course test showed incremental but significant gains (). Participants from the pre-treatment group (nine participants from the Afghan National Gallery), who had experienced some training under the previous field study had a broader range of improvement (ranging between 9% improvement at the lowest and 65% at the highest). Participants from the HUNAR treatment group (18 participants from other heritage and higher education institutions) demonstrated significantly stronger improvements of between of 30 and 85%. The control group, which was comprised of participants from regional galleries who were trained over a shorter duration by Afghan trainers from the treatment group, and who did not participate in group activities also made strong gains (20–45%) indicating that the training of trainers had a successful outcome. In general, male participants performed better than female, and younger participants performed considerably better overall than their older counterparts.

Figure 5. Pre- and post-test training results showing treatment, control, and non-equivalent control groups (Hashimi Citation2021).

Outcomes were positive and indicated that the training methodology was effective. Younger participants were observed to be considerably more engaged in both the theory and practice of collections care and conservation, indicating a strong interest for the subject. However, a clear theme that emerged was that engagement with the theoretical lectures and group discussion and exercises was less favourable. Additionally, for many participants, there was a strong bias toward a desire to learn aesthetic restoration techniques over (the much more needed) basic preventive conservation and collections care. A clear limitation was in the translation of both documents and spoken lectures with technical terms and concepts that were often challenging to translate into local languages. Many technical terms associated with preservation and conservation in English do not have an equivalent in Dari and Pashto, and staff from different heritage institutions often used different terms for the same concepts. To support this, key theoretical conservation texts were translated into both languages for participants. However, the assessment of written test results and condition reporting exercises strongly indicated that these were not consulted by participants. Participant feedback highlighted access to international expertise in conservation as an important factor in the training, as there is a lack of expertise in heritage and collections care in general. However, with this in mind, learning was generally expected to be passive, and reflective practice and critical or enquiry-based approaches were less successful.

Overall, the results demonstrated that while short-term courses and workshops certainly made significant gains in addressing the knowledge gap in heritage conservation in Afghanistan, lack of engagement with theoretical aspects, reflection, and decision making in a group context still requires some work to achieve. It may be that the culture of education in the region favours a more behaviourist, authority-based approach, or simply that these structures of learning require more time to enact the required culture change. It is likely that a move from short-term training and workshops to a longer-term educational structure for cultural heritage staff would be more sustainable. This, of course, requires culture shift in the approach to learning in the region, and not inconsiderable investment, but also perhaps a more cautious and adaptable approach from international educators. It seems likely that where possible, attention should be focused less on sending international experts to the region, which requires significant cost in terms of travel and security and remains fairly low impact given the small number of participants able to attend, and more towards the development of longer term training. A strategic focus on the root cause – the lack of general education in art history, heritage science, collections management, museology, and preventive conservation – is also required. Similarly, the complete lack of conservation literature in Dari and Pashto, and the large cost of translation is a notable issue that remains to be addressed. The creation of a resource library on preventive conservation and a simple digital database for documenting the collections at the ANG is a significant improvement, but whether this can be expanded to cover collections in institutions across Afghanistan remains to be seen, as cross-institutional cooperation is also lacking even amongst the small number of institutions in Kabul. Working on a local curriculum for elementary conservation and collections care at an Afghan university is an endeavour that would significantly facilitate sustainability in heritage conservation in the region. However, whatever the format of training provided, observations made during the HUNAR project, and noted above, also suggest that the direct application of the signature pedagogies typically used in international postgraduate conservation programmes may not always be directly applicable to learners in Afghanistan and similar regions (Shulman Citation2005).

Toward an effective conservation pedagogy for conflict zones

In general, the signature pedagogies in conservation are fairly traditional, and in many ways have not changed much from the apprenticeship-style training that was the norm for many years. Because of this studio apprenticeship heritage, conservation students can sometimes feel that the subject is a practical/scientific one with a theoretical framework loosely attached. Theory, ethics, problem-solving, and decision-making are all key skills in conservation practice (Henderson and Parkes Citation2021.) Yet the integration of theory and practice can sometimes be a challenge for students (Di Pietro, Buder, and Künzel Citation2021). Initially the HUNAR approach to training followed recognisable and fairly standard constructivist pedagogies utilising reflective practice, discussion, and collaborative problem-solving, with a conscious and intentional distancing from notions of imposing the authority of the expert toward a more interactive, student-focused learning experience.

However, this approach, while somewhat effective, failed to consider that students from more traditional cultural backgrounds often expect to be taught in a formal behaviourist manner. Avoiding careless over-generalisation, the teaching team observed that in most cases, students did not expect to engage in group discussion, or question key principles provided by the teacher. Furthermore, participants often expected to be provided with a single solution to a given problem and requested a ‘manual of conservation’ that would tell them how to conserve an object from beginning to end. Students also found it challenging to engage with conservation and preservation theory. In a post-training survey in 2019, theory was often viewed as mundane and dull and with little relevance to practice (Mulholland Citation2019). Participants tended to privilege practical aesthetic restoration techniques over theoretical concepts. A bias toward practical training is perhaps expected for most conservation learners, but deeper cultural feelings were likely also a factor in this case. The strong preference for learning restoration of paintings over basic storage, display, and disaster management principles for example, was reflective not only of the students’ educational background (most are fine art graduates), but also perhaps linked to the fact that the full aesthetic restoration of paintings thought to have been destroyed may be seen as political and social victory over fundamentalism and tyranny.

In his study of constructivist learning theory, Hein notes that our epistemological views dictate our pedagogical views (Hein Citation1991). In other words, our own understanding of learning the theory and practice of conservation tends to influence how what we believe will be effective for all learners. There is an increasing body of literature on how international students learn in Eurocentric contexts, particularly when students from more traditional societies study in a ‘Western’ pedagogical context. Overall, students from more traditional and conservative cultures often expect to memorise information and feed it back in the same way. O’Creevy and van Mourik found in a recent study on the experience of Japanese students in UK HE institutions that the idea of the university entrance exam in Japan, in which the answers are largely learned by rote, often led to the presumption that assessment would follow this pattern in UK HE institutions, sometimes with less than favourable results (O’ Creevy and van Mourik Citation2016) Although the correlation is far from exact, Afghan students, in this limited study, appeared to find this form of learning to be more familiar.

Realistically, of course this is not true of all international students and all ‘non-Western’ societies, but both the literature and empirical observation suggest that this may be a contributing factor in many students’ learning regardless of culture. In conservation, the subject traditionally has a number of rules and practices of learning – an existing academic scaffolding – and to be a competent and confident practitioner requires a tacit understanding of reflective decision making and creative problem-solving (Schon Citation1991). This is not always immediately understandable for students unfamiliar with the context. Inexperienced learners in conservation in general, as noted above, often request a key text on a single issue – something to inform them of the right answer to a problem. This is correlated particularly well in a well-researched study by Ramsden et al. on learning in the medical sciences. The authors noted that inexperienced medical students tended to use a more descriptive approach in their problem solving, using elementary and surface links between symptoms and diagnoses. More mature learners, on the other hand, were used to a more critical approach with more complex, causal chains of reasoning and were able to relate previous case studies and knowledge to the problem more effectively (Ramsden, Whelan, and Cooper Citation1988).

Another important issue for capacity-building in conflict zones is the ability to work optimally in digitally enhanced environments where teaching in person may be impractical. A key impact of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2020–2021was the pressure testing of online pedagogies, on which much has already been written (see for example Morin Citation2020). Some authors note however, that the impact of digital creative pedagogies may or may not result in a new and improved set of creative and competent capacities (McWilliam Citation2007). Applied to the enhancement of conservation capacity in regions of conflict, online/remote technologies may simply be derivative and at risk of reproducing existing social dynamics. While the overall picture of the impact of COVID-19 on conservation education is not yet clear, recent work on remote learning in the advent of the pandemic in the medical sciences has highlighted the pedagogical opportunities for creative teaching for practical/vocational subjects, and this certainly has some correlation with conservation education (Morin Citation2020).

Head has written critically about the pedagogy of discomfort, outlining that how we teach in the context of conflict and war might also reveal innate structures of power (Head Citation2020). However, more traditional approaches to transmitting information may be a foundational requirement before constructivist approaches can be introduced. Though it is well outside the remit of this paper to interrogate critical pedagogical theories, there may well be aspects of this approach that are relevant in reflecting upon the Eurocentric approaches typical in conservation interventions within conflict zone scenarios. In the 1970s the formal lecture began to be criticised, notably by Paolo Freire, as an outdated means of simply ‘banking education’, wherein information is passively ‘deposited’ in student/participant by an authority/expert on the subject and not reflected upon, questioned, or criticised (Freire Citation1970). Foundational work on constructivist approaches to education has led to a much more critical and reflective pedagogy in higher education in Eurocentric/‘Western’ societies. Yet, in practice, the formal and theoretical lecture can allow foundational knowledge of a subject to be provided within a short space of time.

Often students in higher education (and by extension adult learners) in more traditional cultures find the freedom to participate in more reflective discussions around a topic to be daunting, particularly where it may be less practiced culturally. In a 2018 study of lecturers to undergraduate in the UK, Clark found that although most lecturers identified as constructivist teachers and critical pedagogues, many found that it was difficult to engage undergraduate (and some postgraduate) students in reflective and critical thought if they had not been exposed to this kind of learning before (Clark Citation2018). This may be a critical lesson in our approach to teaching heritage conservation in cultures with which we are unfamiliar. In Clark’s study, one participant observed that students may in fact find themselves at a disadvantage if they are suddenly exposed to a more democratic and critical educational setting. Today, the constructivist, flipped classroom approach is employed in many, if not most, postgraduate conservation courses, where critical reflection on decision-making is an integral part of learning to be a competent conservator (Henderson and Parkes Citation2021). The approach may well be beneficial in challenging the authority of the expert, but the power balance between teacher and student in more traditional cultures is complex, may be more deeply rooted, and not be simple (or desirable) to overcome in a short course or workshop.

It is important to point out that this phenomenon is not only observed in more traditional or conservative cultures. Di Pietro et al. have noted that in the context of conservation in the Bern undergraduate programme in Switzerland there was a weakness in graduates’ ability to apply their knowledge in new and unfamiliar scenarios (Di Pietro, et al. Citation2021). The authors carried out an employee evaluation survey in which a key finding was that many Swiss cultural heritage employers found a disconnect between the education of the conservation students and the application of their knowledge in new contexts. The HUNAR project highlighted a similar disconnect, and many Afghan students struggled when faced with applying what they had learned to unfamiliar problems in the context of their day-to-day work. While a great deal of domain-specific knowledge could be absorbed from the HUNAR lecture course, the reflection and critical thinking required to be a competent collections care or conservation practitioner was a considerably more challenging skill to acquire.

The postgraduate conservation student today is generally expected to be self-directed and a self-determinate learner in order to become a capable and competent practitioner. In practice, this follows both andragogical and heutagogical approaches to learning. Andragogy, defined in the 1970s by Knowles and others, privileges learning process above learning content as the most effective approach for adult learners. It emphasises self-directed learning, where learners are actively involved in identifying their needs and planning how these needs are met. Instruction is task-oriented and based on enquiry or problem-solving (Knowles Citation1975). The approach allows learners to develop the capacity for self-direction and utilise the input of their own personal experience, beliefs, and cultures. Above all, students need to know why they are learning something and have this firmly planted in a practical context. A more recent iteration of this is heutagogy, which emphasises self-determined learning – a more holistic approach toward developing capability in addition to competency (Bhoryrub et al. Citation2010; Archino Citation2020). Teacher control over learning and structure lessens with both andragogy and heutagogy. However, both require significantly more maturity and autonomy from the learner, which can be difficult to achieve if the learner lacks confidence or familiarity from their own learning background.

In this model of self-determined learning, Cairns has shown that students must learn both competencies and capabilities (Cairns Citation1996). Competencies are understood as a proven ability in acquiring knowledge and skills within a subject domain – arguably easy to acquire and demonstrate in conservation, where the teacher typically demonstrates, while the student observes, imitates, and practices, while at the same time considering how theoretical frameworks are applied to a particular problem. Capabilities, on the other hand, are characterised by learner confidence in their own competencies and an ability to take action to formulate and solve problems in both familiar and unfamiliar settings. When learners are competent, they demonstrate a range of knowledge and skills that can be repeated. When they are capable, according to heutagogical theorists at least, their competence is extended, and they are able to adapt to new situations (Gardner et al. Citation2008). The dual focus better addresses the needs of learners in complex and changing cultural environments and facilitates adaptation of theory to practice in decision-making and problem-solving.

This has particular relevance to the experience of teaching adult learners with little or no previous knowledge of cultural heritage, preservation, or conservation. There is a commonality in students’ need to find a ‘textbook’ answer to a single problem, and not to engage in a sophisticated way with theoretical frameworks to enhance their capabilities in applying their knowledge to real and more unfamiliar problems. In the absence of elementary knowledge in art history, cultural theory, conservation theory and museology, it is perhaps unsurprising that Afghan students felt that a lecture series on preventive conservation was not immediately applicable to their own experience as heritage professionals. Where the use of case studies, reflection, and self-evaluation are useful in modern conservation education, for students that lack the elementary structural knowledge that underpins conservation, these strategies may be unfamiliar and, in some cases, inappropriate in many circumstances.

Returning to the participants in the HUNAR study, implementation of small-group learning, while demonstrably successful for postgraduate conservation students in the UK, was less successful in the context of Afghanistan. An example of effective constructivist learning in the Conservation of Fine Art masters degree course at Northumbria University, UK is where students are asked to work in small groups on a single problematic case study or question, then present their discussion/research back to the class, with the lecturer acting as chair/mediator for the discussion. In this way, all participants are given the opportunity to learn individually, while simultaneously working as a group and communicating their theoretical learning to the class. Implementing a similar situation for participants in Afghanistan only works where there is a presumption that participants have the experience of group discussion and working with peers. Though very competent learners, we observed that participants in Kabul often did not have the experience or capacity to work in small groups and to apply their learning to a complex case study. Following the andro-heutagogical model, learners were initially asked to carry out a certain amount of self-directed learning and apply this to a hypothetical case study, for example on disaster recovery, or on the organisation of an exhibition. The exercise is intended to develop capability and competency in various areas related to collections care/management in an unfamiliar setting. Lacking a direct model for the unfamiliar scenario from the relevant lecture or a specific answer to the problem caused some confusion and resulted in a general inability to adapt new learning to solve the problem.

Henderson and Parkes have recently demonstrated that conservators have a strong theoretical and tacit understanding of social values and an understanding not only of their duty to society to protect, but also of the meanings and values embodied in a cultural object, site, or cultural practice. They stress a values-based competency framework that is goal-oriented, rather than a more process-driven pedagogy. This may well have particular relevance for conservation education in complex scenarios, given that both time and equipment are often limited. As the authors state, ‘the intuitive, fluid, decision-making that embodies real expertise take hundreds of hours of repeated experiences and reflection to achieve’ (Henderson and Parkes Citation2021). This is rarely achievable either practically (in the short intensive training sessions typical of conservation interventions in active and post-conflict zones), or culturally (in terms of the implementing the andro and heutagogical approaches described above) in the context of more traditional cultures. It may be that we should ‘transform students from passive docile learners into critical co-investigators in dialogue with the teacher’ (Freire Citation1970). However, this may be significantly more difficult to achieve in some cultures than others.

Conclusion

It is important to state that there is no common narrative for cultural heritage and the peoples that it represents. This limited study has demonstrated that although international conservation interventions in post-conflict zones can have significant impact, it is often challenging to create a sustainable impact where cost and security issues generally mean that training takes place over an intensive, but short, period of time. The HUNAR case study presented here by no means describes all conflict-zone interventions. However, it is a useful example that has relevance for future interventions, and it serves as a useful reflection upon the variable ways in which diverse students learn across cultures. For Afghanistan, the only solution is to create long-term institutional change in the country, which is not a simple task. The project team continues to work with international partners and the Afghan Ministry of Information and Culture on developing a full-time conservation programme at Kabul University. While Afghanistan is in an increasingly precarious position at the present time, and hopes dim by the week, and with the risk to its people and its cultural heritage again highlighted by the international community, international development remains crucial. Yet, it is paramount to remain critical and self-reflective about the impact international interventions can have, maintain a cautious approach, and above all understand how we might maximise our efforts to highlight the vital importance of cultural heritage in the region and throughout all world conflict zones.

Ethics approval

This non-interventional study employed participant survey and assessment data. All participants were provided with an information sheet and signed an informed consent form. Participants were informed that they may withdraw their contributed information at any point. All personal data is anonymised. All participant data is held on secure servers at the University of Northumbria and at S&N Consultancy.

Acknowledgements

The author is extremely grateful to the British Council-Cultural Protection Fund, who funded the project, and who continue to make significant impact for cultural heritage in conflict zones throughout the world. Particular thanks are due to Daniel Head, Project Grant Manager at the BC-CPF for his help and guidance throughout. Much gratitude is due to Ms Nadia Hashimi, project manager of HUNAR and CEO of S&N Consultancy, who worked tirelessly to ensure the project was a success. Thanks are also due to the Ministry of Culture and Information, former Islamic Republic of Afghanistan; to Mr Timor Shah Hakimyar (Director at FCCS, Kabul) and his staff; and particularly to Ms Elsa Guerreiro, Director of International Fine Art Conservation Studios (IFACS) Bristol, who brought the project to the author’s attention and coordinated the conservation component with great patience and expertise. Also thanks to conservators Michael Correia and Fred Stubbs, who were invaluable to the work in Kabul. Mr Jolyon Leslie, founder member of SPACH and ACHCO, and Dr Gill Stein (Oriental Institute, University of Chicago) provided incredibly useful insights into present and past conservation interventions in Afghanistan. Above all, this paper is dedicated with deep appreciation and respect to colleagues at the National Gallery, National Museum, National Archives, and heritage institutions throughout Afghanistan who were enthusiastic participants throughout the project, and who remain in the country to protect and preserve its cultural heritage in the face of severe limitations and not inconsiderable danger.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The statistics on the Anglo-American and NATO conflict in Afghanistan are sobering. By the time of the 2001 defeat of the Taliban, the vast majority of Afghans still lived in villages with no electricity. According to the most recent data from the Watson Institute Costs of War project at Brown University, between 2001 and 2022 the total number of deaths directly attributable to conflict in Afghanistan was estimated at 176,000. NATO forces lost 3484 troops, of which 2324 were from the US military. The US spent around 2.3 trillion dollars (Watson Institute Citation2021). Despite the staggering loss of life, quality of life did not dramatically increase over the period. In 2019, lack of employment opportunities (72%) and lack of educational opportunities (38.5%) were cited as the biggest issues facing young people. 72% of respondents stated they feared for their personal safety daily, a percentage that has steadily risen in the survey since 2012 and is undoubtedly higher after the withdrawal of international forces from the region. In 2019, the Taliban were still perceived as the most significant group threat, with only a slightly diminished perception of threat from Khorasan group/Daesh/ISIS (Akseer and Rieger Citation2019). This threat remains all too present in 2022, exacerbated by the prospect of an imminent refugee and humanitarian crisis. At the time of writing, the UNHCR has warned that nearly 55% of the population face extreme levels of hunger.

2 For a comprehensive overview of the troubled history of the Kabul National Museum from 1920 to 2006; see Grissmann Citation2006.

3 Although a small number of random acts of ideological heritage destruction had occurred since the Taliban seized power in 1996, in general it was not widespread until October 2001, when Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, having previously issued a decree in 1999 demanding the protection of all cultural relics in Afghanistan and harsh punishment for illegal excavations and looting, reversed this decision, citing the Western privileging of funding the preservation of statues over humanitarian aid, and proclaimed that figurative representations of living beings should be destroyed (Grissmann Citation2006; Harrison Citation2010).

4 Since watercolours, prints, and drawings were considered of lesser value than oil paintings, and suspicion would be raised were Taliban inspectors to find the walls and storage rooms empty, staff made the difficult decision to sacrifice this collection to save more important works (Anon, ANG, personal communication October 2019).

5 At the time of writing, several months after the 2021 withdrawal of international forces, the resurgent Taliban regime in Kabul has opened the National Museum, restored the Ministry of Culture and Information, and has made promises to protect cultural heritage in the region. However, the ANG and other heritage institutions remain closed and female staff have not yet been permitted to return to work.

6 From 1996 to 2001, only three countries - Pakistan, The United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Saudi Arabia – formally recognised the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan under the Taliban as a legitimate government. At the time of writing, no government has formally recognised the 2021 Islamic Emirate under Taliban leadership.

7 Between 2000 and 2014, 891 NGOs were identified in Afghanistan, of which about 388 were Afghan, 268 were International, and 45 were undetermined. The majority of these NGOs were in education and health. In cultural heritage, the Afghan Cultural Heritage Consulting Organisation (ACHCO), Society for the Protection of Afghan Cultural Heritage (SPACH), and Foundation for Culture and Civil Society (FCCS) are notable exceptions.

8 The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago has implemented a number of far-reaching training partnerships for the conservation of archaeological objects in Afghanistan and more recently for the ‘C5’ Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan). From 2018 to 2020, the Institute organised intensive workshops for conservators from the national museums from the five republics.

9 Founded in Afghanistan in 2006 by HRH Prince of Wales, Turquoise Mountain has restored over 150 historic buildings, trained over 15,000 artisans and generated over $17 million in sales of traditional craft items in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. See: https://www.turquoisemountain.org/afghanistan [Accessed 2 August 2021]

References

- Afghan ethnic groups: A brief investigation. 2011. Civil Military Fusion Center. Norfolk: NATO Allied Commands Operation.

- Ahmad, K. 2001. “Aid Organisations Rebuke UN for Afghanistan Sanctions.” The Lancet 357: 45.

- Akseer, T., and J. Rieger. 2019. Afghanistan in 2019: A Survey of the Afghan People. The Asia Foundation. [accessed 29 July 2021]. https://asiafoundation.org/publication/afghanistan-in-2019-a-survey-of-the-afghan-people

- Anonymous. 2020. Afghan National Archives, Kabul, Personal Communication.

- Archino, Sarah. 2020. “Addressing Visual Literacy in the Survey: Balancing Transdisciplinary Competencies and Course Content.” Art History Pedagogy and Practice 5: 1.

- Asefi, M. Y. 2019. Interview. By Richard Mulholland. 15 October 2019.

- Bak, M. 2019. Corruption in Afghanistan and the role of development assistance. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (U4 Helpdesk Answer 2019:7)

- Barakat, S. 2005. “Post-war Reconstruction and the Recovery of Cultural Heritage: Critical Lessons from the Last Fifteen Years.” In Cultural Heritage in Post War Recovery, edited by N. Stanley-Price, 26–40. Papers from the ICCROM forum. Oct 4–6. Rome: ICCROM.

- Becatoros, E. 2021. Afghan Museum Reopens with Taliban Security – and Visitors. Associated Press News, 6 December 2021.

- Bhoryrub, J., J. Hurley, G. R. Neilson, M. Ramsay, and M. Smith. 2010. “Heutagogy: An Alternative Practice-Based Learning Approach’.” Nurse Education in Practice 10 (6): 322–326.

- Boak, E. 2019. “From Conflict Archaeology to Archaeologies of Conflict: Remote Survey in Kandahar, Afghanistan.” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 14 (2–3): 143–162.

- Brosché, J., M. Legnér, J. Kreutz, and A. Ijla. 2017. “Heritage Under Attack: Motives for Targeting Cultural Property During Armed Conflict.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (3): 248–260.

- Caesar, B., and A. R. Rodriguez García. 2006. “The Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage: An Overview of Activities Since 1994.” In Art and Archaeology of Afghanistan: Its Fall and Survival, edited by J. van Krieken-Pieters, 15–38. Leiden: Brill.

- Cairns, L. 1996. “Capability: Going Beyond Competence.” Capability 2: 80.

- Campbell, D. T., J. C. Stanley, N. L. Gage, T. Bärnighausen, P. Tugwell, J. A. Røttingen, I. Shemilt, et al. 2017. “Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Quasi-Experimental Study Designs Series - Paper 4: Uses and Value.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 89: 21–29.

- Cassar, B., and M. Nagaoka. 2007. Project Final Report: Project of Endangered Movable Assets (EMA) of the National Cultural Heritage - 24225110KAB. Documentation and Conservation of Collections in the National Museum of Afghanistan, Unpublished Report. UNESCO. March 15, 2007.

- Chulov, M. 2015. “A Sledgehammer to Civilisation: Islamic State’s War on Culture” The Guardian. 7 April 2015. [Accessed on 11 January 2022] http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/07/islamic-state-isis-crimes-againstculture-iraq-syria.

- Clark, L. B. 2018. “Critical Pedagogy in the University: Can a Lecture be Critical Pedagogy?” Policy Futures in Education 16 (8): 985–999.

- Corruption Perception Index. 2020. Transparency International. [accessed 29 July 2021]. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index.

- Di Pietro, G., A. Buder, and M. Künzel. 2021. “Improving Transfer in the Education of Conservators- Restorers.” In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation, ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, 17–21 May 2021, edited by J. Bridgland. Paris: International Council of Museums.

- Dupree, N. H. 2006. “Prehistoric Afghanistan: Status of Sites and Artefacts and Challenges of Preservation.” In Art and Archaeology of Afghanistan: Its Fall and Survival, edited by J. van Krieken-Pieters, 79–94. Leiden: Brill.

- Evaluation of UNHCR’s Country Operation: Afghanistan. 2020. ITAD Ltd. The United Nations Refugee Agency.

- Fitzgerald, P., and E. Gould. 2009. Invisible History: Afghanistan’s Untold Story. San Francisco: City Lights.

- Fredheim, L. H., and M. Khalaf. 2016. “The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (6): 466–481.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Continuum.

- Gardner, A., S. Hase, G. Gardner, S. V. Dunn, and J. Carryer. 2008. “From Competence to Capability: A Study of Nurse Practitioners in Clinical Practice.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 17 (2): 250–258.

- Gerstenblith, P. 2009. “Archaeology in the Context of War: Legal Frameworks for Protecting Cultural Heritage During Armed Conflict.” Archaeologies 5: 18–31.

- Grissmann, C. 2006. “The Kabul Museum: Its Turbulent Years.” In Art and Archaeology of Afghanistan: Its Fall and Survival, edited by J. van Krieken-Peters, 49–61. The Netherlands: Brill.

- Guzman, P., Pereira Roders, A. R., and B. Colenbrander. 2018. "Impacts of Common Urban Development Factors on Cultural Conservation in World Heritage Cities: An Indicators-Based Analysis." Sustainability, 10: 853. http://doi.org/10.3390/su10030853

- Haldane, E., S. Glenn, S. Hunter, and L. Hillyer. 2012. “Raksha: Raising Awareness of Textile Conservation in India.” In Post Prints, American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works 40th Annual Meeting Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2012, Vol. 22, edited by A. Holden, S. Stevens, J. Carlson, G. Peterson, E. Scuetz, and R. Summerour, 19–31.

- Harrison, R. 2010. “The Politics of Heritage.” In Understanding the Politics of Heritage, edited by R. Harrison, 154–196. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hashimi, Nadia. 2021. Impact Evaluation Report: Heritage Unveiled: National Art Restoration Project, Unpublished Report.

- Hassan, H. 2015. Religious Teaching that Drives Isis to Threaten the Ancient Ruins of Palmyra. The Guardian, 24 May. [Accessed on 29 July 2021]. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/24/palmyra-syria-isis-destruction-of- treasures-feared.

- Head, N. 2020. “A Pedagogy of Discomfort? Experiential Learning and Conflict Analysis in Israel – Palestine’.” International Studies Perspectives 21: 78–96.

- Hein, G. 1991. Constructivist Learning Theory. The Museum and the Needs of People. Conference Papers. CECA: International Committee of Museum Educators. Jerusalem Israel, 15–22 October 1991.

- Henderson, J., A. Dawson, U. Kyaw Shin Naung, and A. Crossman. 2021. “Preventive Conservation Training: A Partnership Between the UK and Myanmar.” In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation, ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, 17–21 May 2021, edited by J. Bridgland, 1–6. Paris: International Council of Museums.

- Henderson, J., and P. Parkes. 2021. “Using Complexity to Deliver Standardised Educational Levels in Conservation.” In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation, ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, 17–21 May 2021, edited by J. Bridgland, 1–9. Paris: International Council of Museums.

- Isakhan, B., and L. Meskell. 2018. “UNESCO’s Project to ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’: Iraqi and Syrian Opinion on Heritage Reconstruction After the Islamic State.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1189–1204.

- Kersel, M. M., and C. Luke. 2015. “Civil Societies? Heritage Diplomacy and Neo-Imperialism.” In Global Heritage: A Reader, edited by L. Meskell, 70–94. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Khabir, A. 2001. “UN Sanctions Imposed Against Afghanistan While Thousands Flee.” The Lancet 357: 207.

- Klimaszewski, C., G. E. Bader, and J. Nyce. 2012. “Studying Up (and Down) the Cultural Heritage Preservation Agenda: Observations from Romania.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 15 (4): 479–495.

- Knowles, M. S. 1975. Self-Directed Learning. New York: Association Press.

- Leslie, J. 2014. Cult, Culture and the Need for Public Education: Why the National Museum in Kabul has Little Meaning for Afghans. Afghanistan Analysts Network. 21 November 2014 [Accessed 29 July 2021]. https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/cult-culture-and-the-need-for-public-education-why-the-national-museum-in-kabul-has-little-meaning-for-afghans/.

- Luke, C., and M. M. Kersel. 2013. U.S. Cultural Diplomacy and Archaeology: Soft Power, Hard Heritage. New York: Routledge.

- Maeda, K. 2006. “The Mural Paintings of the Buddhas of Bamiyan: Description and Conservation Operations.” In Art and Archaeology of Afghanistan: Its Fall and Survival, edited by J. van Krieken-Peters, 127–145. Amsterdam: Brill.

- Martin, G., and C. Enderby Smith. 2021. “UN Sanctions.” In The Guide to Sanctions, edited by R. Barnes, P. Feldberg, N. Turner, A. Bradshaw, D. Mortlock, A. Thomas, and R. Alpert, 9–27. London: Global Investigations Review.

- McWilliam, E. 2007. “Is Creativity Teachable? Conceptualising the Creativity/Pedagogy Relationship in Higher Education.” In Proceedings of the 30th HERDSA Annual Conference, edited by G. Crisp, and M. Hicks, 1–8. Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Inc.

- Mitchell, D. F. 2017. “NGO Presence and Activity in Afghanistan, 2000–2014: A Provincial-Level Dataset. Stability.” International Journal of Security and Development 6: 1.

- Morin, K. 2020. “Nursing Education After Covid-19: Same or Different?” Journal of Clinical Nursing 29 (17–18): 3117–3119.

- Mulholland, R. 2019. Post-training Survey of Participants, Afghan National Gallery, unpublished report. Kabul.

- Nankivell, S. 2016. “Speaking of Sledgehammers: Analysing the Discourse of Heritage Destruction in the Media.” Unpublished MPhil Dissertation. University of Cambridge.

- O’ Creevy, M., and C. van Mourik. 2016. “‘I Understood the Words but I Didn’t Know What They Meant’: Japanese Online MBA Students’ Experiences of British Assessment Practices’.” Open Learning 31 (2): 130–140.

- Pearlstein, T., and J. S. Johnson. 2020. “Recording and Archiving Conservation Education Approaches in Iraq, 2008–2017.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 59 (1): 53–64.

- Ramsden, P., G. Whelan, and D. Cooper. 1988. “Some Phenomena of Medical Students’ Diagnostic Problem Solving’.” Medical Education 23 (1): 108–117.

- Schon, D. A. 1991. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Routledge.

- Seymour, K., R. Hoppenbrouwers, L. Pilosi, and V. Daniel. 2019. “What Does an 18th Century Dutch Hindeloopen Period Room and a 21st Century Training Project Have in Common?: Answer the Indian Conservation Training Program.” The Picture Restorer 55: 36–44.

- Shulman, L. S. 2005. “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions.” Daedalus 134 (3): 52–59.

- Smith, R. 2008. Silent Survivors of Afghanistan’s 4,000 Tumultuous Years. Art Review. New York Times. May 23 2008.

- Stanley-Price, N. 2005. “The Thread of Continuity: Cultural Heritage in Post-war Recovery.” In Cultural Heritage in Post War Recovery, edited by N. Stanley-Price, 1–17. Papers from the ICCROM forum, Oct 4–6. Rome: ICCROM.

- Stein, G. 2017. “The Oriental Institute Partnership with the National Museum of Afghanistan.” In The Oriental Institute Annual Report 2016–2017, edited by C. Woods, 136–143. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Stein, G. 2019. “The Oriental Institute Partnership with the National Museum of Afghanistan.” In Cultural Heritage Preservation work in Afghanistan and Central Asia 2018–2019, edited by C. Woods, 27–36. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Stone, P. G. 2015. “The Challenge of Protecting Heritage in Times of Armed Conflict.” Museum International 67 (1–4): 40–54.

- The Forbidden Reel. 2019. dir. by Nasr, A. Canada: National Film Board of Canada/Loaded Pictures.

- UNHCR Refugee Data. 2020. [accessed 29 July 2021]. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

- United Nations Security Council. 2000. Resolution 1333 (2000), 19th December 2000.

- U.S. Costs to Date for the War in Afghanistan, in Billions FY2001-FY2022. Watson Institute for International & Public Affairs, Brown University [accessed 13 December 2021]. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/human-and-budgetary-costs-date-us-war-afghanistan-2001–2022.

- Viejo-Rose, Dacia. 2007. “Conflict and the Deliberate Destruction of Cultural Heritage.” In Conflicts and Tensions, edited by H. Anheier, and Y. R. Isar, 102–119. London: Sage.

- White, H., and S. Sabarwal. 2014. Quasi-Experimental Design and Methods. Methodological Briefs no 8: Impact Evaluation. UNICEF.

- Wimpelmann, T. 2017. The Pitfalls of Protection: Gender, Violence, and Power in Afghanistan. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Yamin, S. 2013. “Global Governance: Rethinking the US Role in Afghanistan Post 2014.” Journal of South Asian Development 8: 2.