ABSTRACT

Artists have been making their mark on the world for at least 70,000 years. Some of the best known examples of what is commonly referred to as cave art are from the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe, at sites which are popular tourist attractions, their visitors wondering at the motivations of those responsible. In some ways, contemporary graffiti are not so dissimilar: passers-by stopping to view art without ever seeing the artists at work, puzzled at their intentions. As in the caves, these more recent works have a sense of the mysterious, while bringing light and dynamism to otherwise mundane and unspectacular spaces, giving these spaces new meaning and adding value. In this paper, we focus on ways that archaeological interpretation contributes to understanding the cultural significance of the interstitial places where these historic and contemporary artworks are often found and also, therefore, the marginalised people who typically inhabit them.

Introduction

Graffiti are often understood to be ‘the repeated stylized writing of a name or symbol on public space in an effort to gain recognition both for the name or symbol and the individual producing it’ (Mitman Citation2018, 4). However, this definition can be extended to include any expression on public or authoritatively controlled space that presents an individual’s or group’s identity, opinion, worldview, or cause.

Whether Upper Palaeolithic, historic or contemporary in origin, various forms of art and graffiti, what we might define collectively as wall writing, have been studied in depth over many years. As Chippindale and Taçon (Citation1998, 1) have said, human beings have symbolically marked landscapes for millennia and this can be seen as a ‘characteristically human trait’, being ‘one of the ways we socialise landscapes’. Ralph (Citation2014, 3103) has further emphasised this historic lineage of graffiti, stating that it can be seen as ‘a continuation of landscape-making and mark-making communication practices’ that have been used by humans for tens of thousands of years. The earliest examples include cave art which has been researched by archaeologists for over a century (e.g. Breuil and Capitan Citation1901; Leroi-Gourhan Citation1967; Samson et al. Citation2017), while medieval and later graffiti has been the subject of more recent historical and archaeological investigation (e.g. Clarke, Frederick, and Hobbins Citation2017; Champion Citation2015; Bopearachchi and Rajan Citation2002). In other fields of research, sociologists and art historians have been studying modern graffiti and wall writing since the early 1970s (e.g. Castleman Citation1984; Mitman Citation2018; Snyder Citation2009). While much of the emphasis in early graffiti and wall art research took place in Europe and North America, this emphasis has now shifted. Examples of graffiti research from outside of Europe include: Palmer’s (Citation2016b) examination of the distinction between brigade muralists and the graffitero in Chile; Abaza’s (Citation2016) discussion of post-2011 Egyptian graffiti; Rukwaro and Maina’s (Citation2020) work on East African graffiti artists; Yamakoshi and Sekine’s (Citation2016) discussion of graffiti and street art in Tokyo and the city’s surrounding districts; Obłuski and Maczuga’s (Citation2021) overview of graffiti from the Ghazali Northern Church in Sudan; and Peteet’s (Citation2016) work on Palestinian graffiti.

In terms of a research focus, scholars have more recently begun to consider how graffiti can help better understand how individuals and communities from the past interacted with place and with the landscape (). Baird and Taylor Citation2016, 20), for example, have described how graffiti could be used to map particular areas within the ancient city, studying marks to consider questions of temporality and spatiality through the production and content of the graffiti, as well as considering the relationship between the artist as performer and the viewers as audiences. As Benefiel (Citation2010, 60) has similarly said in regard to Pompeii, ‘[A]ncient graffiti were not merely texts on particular themes; they were also part of the built environment. … They mark where people spent time … graffiti indicate where Pompeians would be present – and where there might be an audience for such writings’. In addition, researchers are now studying tourist graffiti, where visitors have carved their names, initials, dates and expressions of affection into walls, rocks and on tree trunks (Anderson and Verplanck Citation1983, 341). This tradition appears universal, drawing a parallel with the contemporary tradition of engraved love locks, padlocks with the initials of lovers, attached to railings in public places to affirm a relationship (Houlbrook Citation2021, 8).

Figure 1. The later cell block to the right of the medieval keep at Richmond Castle, North Yorkshire, the location of First World War graffiti left here by conscientious objectors. Image reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Figure 2. Graffiti in an alleyway in London. Image included with kind permission of Instagram user Grafflens.

Against the background of a much deeper history, such personalised graffiti and marks have therefore been created over at least two millennia, in the form of signatures sometimes accompanied by simple political or personal messages. Some examples were deliberately placed to be on public view while others are carved or drawn in quiet, out-of-the-way places. To take London as an example, Cody (Citation2003, 82) describes how its inhabitants ‘scribbled marks in public spaces long before they suffered from modern anomie. Perhaps even more surprisingly, some eighteenth- and nineteenth-century citizens even celebrated graffiti, presenting these public scrawls as a delightful and democratic language they could all share. … Every lane teems with big instruction, and every alley is big with erudition.’ This historic situation continues today with contemporary artists making street art and graffiti in plain sight, often in prominent locations, along busy roads and in city centres. Yet now, perhaps unlike in the past given higher levels of regulation, graffiti artists create their work clandestinely, often at night, often making their mark while the city sleeps.

The furtiveness with which many wall writers work is a byproduct of how what they are doing comes into conflict with the ideological construction of the space where they produce that work. The ideological construction of a space, though, is a complex thing. It is influenced by the hegemonic values of the wider culture, but it is more directly a product of the authority of those who claim ownership over it, the space’s particular history, the competing interests that debate how the space should be used, the way those who claim ownership over the space are able to marshal the legal system to function on their behalf, as well as many other influences. This is what we refer to when we discuss authority. As Frederick (Citation2009) has argued, graffiti can be ‘not only interpreted as a record of human presence and the social construction of space but as a function of efforts to make claims over space’. We mean the values that define a space, ones that are tacitly acknowledged but that often remain invisible until they are pointed out or revealed by being challenged. Here, we examine specific instances of wall writing, what these acts mean, and how they challenge the particular forms of authority in the spaces where they occur.

In this paper, we use archaeology as a lens for shaping a cross-cultural and multi-period theory of mark making. Our aim is to frame the work of wall writers within the related contexts of marginalisation and identity, both of those being represented and those doing the representation. We focus on the materiality of wall writing, the locations of the artworks, and the motivations of the artists and audience reactions to the works. Our interests are in the commonality of our selected examples but also in any differences. Ultimately, we are interested in what these examples tell us about society and, in particular, those people who are marginal to the mainstream and who occupy those places that are often hard to find and hidden from view. This is not a study which seeks to translate knowledge from the present into past societies. Rather, our concern is for what wall writing contributes to our understanding of the contemporary world.

Specifically, the paper draws together two ongoing projects, at the universities of York and York St John (UK). The first project is focused on historic graffiti recorded at sites managed by English Heritage. This collaborative project involving English Heritage and the University of York, was established to create a better appreciation of these graffiti and their significance in understanding the sites on which they are found, not least through reference to modern graffiti and mark making. A particular focus of this paper is on the well-documented graffiti left by conscientious objectors in their cells at Richmond Castle (North Yorkshire, England) during the First World War. The second project examines more contemporary forms of graffiti and their relationships with interstitial and public space and public discourse. In this context we discuss a well-known piece of graffiti (Spin’s 1982 ‘Dump Koch’ car) and a less famous one by street artist John D’oh. These two pieces were chosen to illustrate how wall writers use their art and public space to express opinions and political ideas that would otherwise not have an outlet. In terms of method, the historical example of Richmond Castle (UK) relied heavily on a detailed study of the cell-block graffiti (including photographic recording and historical analysis of contemporary sources), involving one of the authors. The second case study (involving recent and contemporary graffiti from New York City and Bristol, UK) used existing public knowledge about each of these graffiti pieces through a combination of visual analysis of the images and discursive analysis of the messages they convey and the politics with which they engage.

We will now discuss these projects separately, before drawing out some broader issues for discussion.

Historic graffiti: Richmond Castle

The nineteenth-century cell block at Richmond Castle contains thousands of graffiti marks left by those imprisoned in the cells, or who otherwise accessed the building (). Constructed in the 1850s, the cell block now contains around 2,300 inscriptions dating from the nineteenth century to the 1970s. Between 2016 and 2019 these inscriptions were the focus of an English Heritage project, the Richmond Castle Cell Block Project (RCCB), which sought to conserve, record and research these graffiti.

There are many examples throughout history of prisoners carving graffiti during their incarceration as a reaction to boredom, to try to alleviate psychological stresses caused by such environments or as a form of resistance (e.g. Burton and Farrell Citation2013; Casella Citation2001; McAtackney Citation2016; Palmer Citation2016a). In their analysis of the graffiti left by prisoners at a former Jesuit College which was converted into a concentration camp by Franco’s military during the Spanish Civil War, Ballesta and Rodríguez Gallardo (Citation2008, 202–4) discuss how the marks have a ‘silent presence’ and the walls have become a ‘printing press of the prisoners’ the graffiti which still remains simultaneously demonstrate the diverse voices of the anonymous prisoners whilst also acting as a rite of self-preservation to establish a record of the authors of these marks (Ibid, 205). Interestingly, some modern graffiti found in public spaces may have served a similar resistant purpose, as a reaction to the way in which these environments are increasingly controlled. Thus, in both historic and contemporary settings, graffiti as a resistant act may have been coded by their message or context (such as the prison environment), rather than by the mark itself.

At Richmond Castle, some of the most significant marks left in the cell block were made during the First World War by a group of conscientious objectors (COs) known as ‘The Richmond Sixteen’, people who refused to participate in the War on moral, political and religious grounds and were subsequently detained in the cell block. The Richmond Sixteen were among the first people in the country to defy conscription on moral grounds and included a mix of socialists and committed Christians whose ‘pacifism was informed by their most deeply held beliefs’ (Ross Citation2020, 136). In the following decades, many others left their marks on the cell block, including soldiers from the local Green Howards regiment who were detained for disciplinary reasons during the Second World War (Goodall Citation2016, 31). But it is the conscientious objectors’ graffiti that stand out, having been described as one of the few surviving examples of Great War soldier’s art in military buildings and ‘a rare example of what may have been commonplace’ (Cocroft et al. Citation2006, 38). They function both as expressions of the convictions of conscientious objectors at Richmond Castle and as the tangible evidence of their resistance (English Heritage Citationn.d.a, Citationn.d.b).

During 1915, voluntary recruitment figures began to steadily decline following a massive number of casualties sustained during the First World War’s first year of fighting whilst the number of men needed at the Front increased, leading to an urgent need for more soldiers. In response, the British Government passed The Military Service Act which introduced conscription. Although new conscription laws allowed men to appeal against military service, few conscientious objectors were given total exemption and most were ordered to enter the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), a uniformed branch of the Army where men supported fighting troops without going into battle themselves (Goodall Citation2016, 30). Conscientious objectors who entered the NCC included men from socialist groups who objected to the War on political and humanitarian grounds and men from religious groups such as the Quakers and Wesleyan Methodists who held strong pacifist beliefs and followed the biblical commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill’. Prior to the outset of the First World War, pacifism in Britain had been largely tolerated but during the War it became increasingly unpatriotic (Burnham Citation2014, 6). The introduction of conscription brought the stance of those who opposed the War into sharp focus as those eligible for military service had to decide whether to fight or to what extent they were able to participate in the war effort without compromising their beliefs.

In May 1916, Richmond Castle became the northern base for the NCC. Whilst there, absolutist conscientious objectors, including The Richmond Sixteen, refused to be involved in any contribution to the war effort whatsoever and were subsequently punished and held in terrible conditions in the Cell Block (Ellsworth Jones Citation2008, 103–116; Goodall Citation2016, 30; McMahon Flatt Citation2018, 153). When he was barracked at Richmond Castle, Private Horace Eaton, a CO who served in the NCC, made notes on the brutality that he observed against other COs during their resistance, writing that: ‘The methods adopted to try and make these young fellows into non-combatants or soldiers often made one’s blood boil with indignation’ (cited in Kramer Citation2014, 82).

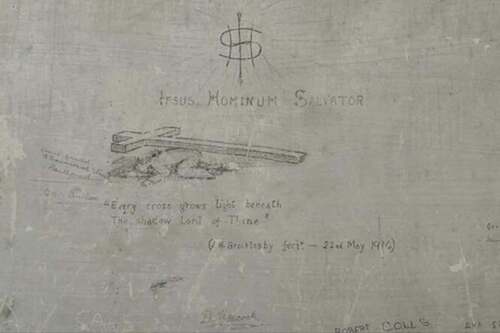

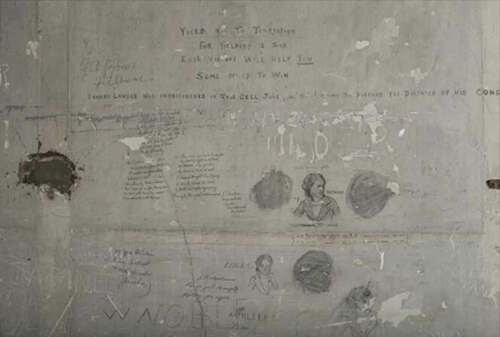

Within the cell block, The Richmond Sixteen and other conscientious objectors left a record of their presence and their resistance on the walls. This record includes ‘expressions of their beliefs and emotions: slogans, poetry, portraits of loved ones, prayers and political stances’, which survive over a century later () and are now in the care of English Heritage (McMahon Flatt Citation2018, 154). The threat of being sent to France and court-martialled was very real for The Richmond Sixteen and the graffiti may have been the last marks they thought they were leaving the world: ‘Here is where they made their stand. Here is where they were going to face the consequences. Their future was uncertain’ (Leyland, cited in Ross Citation2020, 137). This use of graffiti as an act of self-preservation or record of self has also been discussed by Ballesta and Rodríguez Gallardo, who argue that graffiti are left as a physical trace of one’s presence when death is believed to be imminent (Citation2008, 205). One of these graffiti in the cell blocks at Richmond Castle was drawn by John Hubert Brocklesby just a week before The Richmond Sixteen left on 29 May 1916 for Le Havre and Boulogne in France where they were sentenced to death (Ross Citation2020, 137). A fellow CO, Norman Gaudie, wrote in his diary that Brocklesby ‘did not waste time for he drew on his cell wall a man lying on the ground struggling under the load of a heavy cross’ before noting: ‘This day we were all expecting to be sent out to France.’ () (Gaudie Citation1916).

Although their sentence was reduced to ten years’ hard labour, The Richmond Sixteen continued to face hostility from their local communities and employers after the War (Ellsworth-Jones Citation2008, 233–48). To this day, the empty rooms of the Cell Block gain their power from, ‘a sense of mingled absence and presence; the men imprisoned here are long gone but their sacrifice – for an idea which found little sympathy at the time – is expressed in every pencil stroke’ (Ross Citation2020, 137). The willingness of The Richmond Sixteen, among other COs, to face the death sentence demonstrated the strength of their beliefs and challenged public perceptions of their stance (Boulton Citation1967, 174; English Heritage Citationn.d.a). The RCCB has used the cell block graffiti to facilitate more discussion around conscientious objection and the impact of such resistance (English Heritage Citation2020).

In reference to Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, Ireland, McAtackney (Citation2016, 493, 503) has described how the site itself has ‘long been a symbol of injustice and resistance for Irish nationalists’ who were imprisoned and executed there, such as during the period of ‘Revolutionary Ireland’ (ca. 1912–1924), whilst the graffiti created by the prisoners also evidenced these issues in material form as a ‘reference to both everyday experience and extraordinary event[s]’. In a similar manner, the cell-block graffiti at Richmond Castle were markers of presence and existence of the conscientious objectors in an institution and society often hostile to their stance and beliefs. The graffiti left behind evidence both their day-to-day experience in the cells whilst serving as a reminder of their remarkable strength and determination to live according to their conventions and beliefs. They also reflect some of the themes of general prisoner and detainee graffiti described by Palmer as ‘separation, resistance and testimony’ (Citation2016a, 559).

The future of men sent to Richmond Castle and other NCC units was often uncertain. There was the ever-present threat of being sent to the front where conscientious objectors could face capital punishment for refusing orders (Boulton Citation1967). As has already been highlighted, within this context, the need to proclaim one’s presence was an important personal and political act. In the face of such an uncertain future, leaving a marker of one’s existence or recording experiences and views which would otherwise be left unknown and unheard, likely took on great significance. Alongside this desire to leave a mark for posterity, the graffiti may have provided the COs with an opportunity to reframe their detention, find renewed strength through the creation of their marks and provide a form of support for future prisoners within these cells. For example, one CO wrote: ‘All COs who enter here be of good cheer for we cannot lose in this fight for liberty, for Right ever came out on top’. Another wrote: ‘though shut in away from the world I am shut in with my Lord’. The cells therefore functioned as both collective and private spaces, the graffiti representing expressions of the beliefs of the individual wall writers and a form of communal resistance and solidarity.

Leaving a mark also offered conscientious objectors the opportunity to reassert their reasons for objection which had not previously been accepted by military service tribunals. Articulating these reasons was something conscientious objectors were repeatedly required to do, in applications for exemption, in front of military service tribunals, to the commanders of the NCC and no doubt also to their families, friends and communities. However, unlike more recent graffiti and street art in public spaces, these political writings were not accessible or necessarily intended for a wider public audience. At Richmond, their reach was limited to those with access to the cells – fellow detainees and members of the NCC – or to a future imagined audience (Booth Citation2020, 26-27). As highlighted in other carceral environments, they could also be a personal act, a form of self-affirmation for the wall writer alone (Wilson Citation2008, 70).

The prevalence, visibility and survival of wall writing within the cells also brings into question how far the act of creation – as perhaps opposed to the content of the wall writings – was an affront to military authority. From the content of graffiti and surviving dates it can be suggested that in the region of 220 examples can be attributed to conscientious objectors, though further research may change this number (English Heritage Citation2020). Many of the graffiti include identifiers such as names and addresses, so are far from anonymous, and the quantities imply a degree of tolerance, that they were perhaps not seen as important, or a lack of monitoring or enforcement of rules. Horace Eaton’s (Citation1918) account offers some insight on the latter and suggests some leniency from NCC guarding the detainees: ‘The prisoners diet for a start is usually bread & water & probably another way of trying to break their wills - & then they have food like us. We take turns on guard duty - & thus have a good opportunity to do our best for these young fellows in regard to food & to post letters for them to their loved ones. (This was against the rules of course)’.

Contemporary graffiti and street art: New York City and Bristol, UK

While the motivation for historic graffiti at Richmond can be interpreted as a form of self-affirmation or solidarity, the motivation for producing graffiti and street art is often more about friendship, rebellion, self-promotion, and self-aggrandizement (e.g. Castleman Citation1984; Halsey and Young Citation2006; Snyder Citation2009). However, a great deal of it is also about expressing marginalized ideas or opinions on spaces that are difficult to ignore or suppress (Waldner and Dobratz Citation2013). The graffiti at Richmond were located in an institutional space yet, within that space, they were conspicuous. Wall writers can repurpose conspicuous public space to present messages that would otherwise be constrained or prevented from existing. In so doing they integrate their message into the discursive structure of that space. They make it heard.

Often the message is simply one of existence, involving wall writers merely writing their name or making their mark. In and of itself, this is an important act. It proclaims one’s presence and agency in a milieu that would often prefer those without the financial resources to be represented remain quiet, passive, and anonymous. This ability to achieve public recognition is made more important when the graffiti carry a political or social message. Wall writers are able to present marginalized messages without them being subject to authoritative or editorial repression, at least until their work is buffed (cleaned) away. Further, they are able to communicate their message publicly, for free, to whoever sees that space (in person or, increasingly, digitally).

It is worth noting that wall writing can also be used to broadcast objectionable ideologies or reinforce existing social power dynamics (Sanghera Citation2021, 73). For these reasons, to properly understand what is being expressed through wall writing, one must not only understand what is said and where it has occurred but also the historical, political, and cultural context in which it occurs. For example, Frederick (Citation2009) and Frederick and O’Connor (Citation2009, 153) have discussed an instance where there was actually an inversion of the idea of the wall writer resisting hegemonic discourse, as they considered an instance of appropriation of a Wandjina figure which was seen as an ‘unsettling occurrence’ for the Indigenous people of the Kimberley region to whom the Wandjina are the supreme spirit ancestors. In contrast, Martin (Citation2016, 124) has described how some Indigenous American graffiti has been used to educate the wider population about their marginalization in society, emerging ‘as a form of resistance to historical trauma and cultural oppression, which is traced back to the legacy of colonialism’ (Citation2016, 124). The ideas or identities that wall writing represents may be an exclamation from those enduring some forms of suppression, or they may be assertions that support the present hegemonic divides, as hateful, racist, and misogynistic wall writing does, or something else entirely. In such instances, we can consider how these relate to structures of privilege where graffiti is placed ‘into a position of power over instead of power against’ (Borck Citation2016, 3–4). Our attempt here is to examine and historically contextualize certain wall writings as well as the positionality of the writers to improve their understanding within their historical moment.

The 1981 New York City (NYC) mayoral election saw an unprecedented event occur. Ed Koch ran for, and won, both the Democratic and Republican primaries. He ran for mayor as a Democrat with Republican endorsement and was re-elected mayor in an overwhelming landslide victory, receiving 75% of the citywide vote. Koch was so popular that he beat the runner-up from the Unity party by 61%. Needless to say, Koch was a popular and beloved NYC personality.

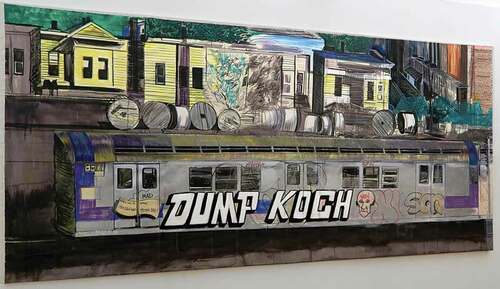

He had his detractors though. He ran on the position of cleaning up NYC, which meant reducing crime and vandalism and bringing in new investors. Some saw him as too interested in corporate money. Graffiti writers despised him for initiating the war on graffiti that sought to remove it entirely from the city, but specifically from the subway trains. In the summer after Koch won the 1981 election, graffiti writer SPIN TFS painted ‘DUMP KOCH’ in huge letters on the side of a subway train on the ‘5’ line that travels through Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx (). The train carried SPIN’s message to hundreds of thousands of subway riders and was spread even farther by Martha Cooper’s famous photograph of the work (the piece became such a touchstone of graffiti-as-political-commentary in NYC that 34 years later it inspired a ‘Dump Trump’ piece near Trump Place in Manhattan – https://blog.vandalog.com/tag/tfs-crew/). What is important is that Spin TFS, through his artistic work and force of will, was able to repurpose the side of a subway train to carry an unpopular and marginalized opinion that otherwise would not likely have found the public space to be represented.

Figure 5. Dump Koch image from New York. Image is a painting by James Jessop based on the original graffiti by SPIN TFS and reproduced with James Jessop’s permission.

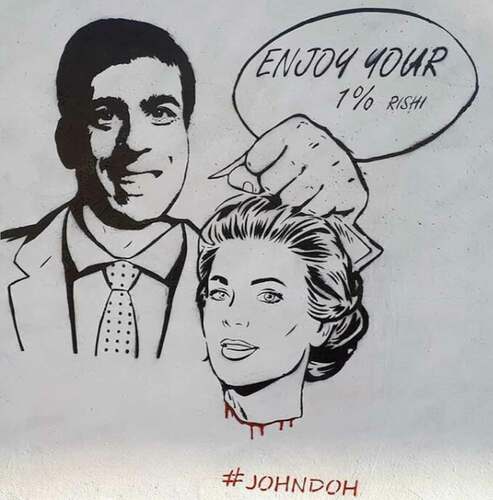

Sometimes the message being conveyed by wall writers through street art and graffiti is not a completely marginalized one. Rather, it can be one that presents an established but oppositional message in a controversial way that makes the work, and the issue it references, hard to ignore. A stencil by Bristol-based street artist John D’oh does just that (). It depicts Chancellor of the Exchequer (The UK’s chief financial minister) Rishi Sunak saying ‘Enjoy your 1%’ while holding the decapitated head of a nurse. It is a reference to the UK government offering National Health Service (NHS) staff a 1% pay raise in 2021 during the COVID Pandemic, when they had previously promised 2.1%. This offended many, and the dissatisfaction can be found in numerous op-eds deriding the 1% raise decision. The government claims it was all they could afford due to pandemic-related expenses and reductions in income. But that has not appeased NHS supporters or the Royal College of Nurses, who called the raise ‘pitiful’ (Walker, Allegretti, and Quinn Citation2021).

Figure 6. Rishi Sunak image from Bristol, UK. Image is by John D’oh, and reproduced with kind permission of the artist.

John D’oh’s piece makes clear reference to this while also lampooning Sunak as a kind of grinning executioner who has lopped off the metaphorical head of the NHS, while also expecting to be thanked for his efforts (the 1% raise). This piece of street art is provocative and compels the viewer to respond to it. It also presents the established message that NHS workers are underpaid and underappreciated through this succinct and confrontational visual medium. John D’oh’s work is equal parts editorial and political cartoon, sprayed on the walls of Bristol without any edits or censoring.

What these two pieces represent is the ability of wall writers who make graffiti and street art to reshape public space into something more active, expressive, and compelling. The wall writers who use these spaces are able to voice their political opinions in a way that grants them total freedom of expression. This matters because as urban space becomes more authoritatively controlled and corporately possessed, the ability to express any opinions other than those that are aligned with those interests diminishes. Wall writers who work illegally to express marginalized or provocative positions circumvent this simply by not asking for permission and accepting the risks that come with that. We see something similar at Richmond Castle where the graffiti left by conscientious objectors shape institutional space in the same way. They are a forum for expression and through their creation also becomes an act of resistance and dissension against authority or the marginalisation of their views.

Discussion

While the cases examined here may seem distinct in time and place, they are unified by a fundamental condition of wall writers to express themselves and to have their identities and ideas recognized. Here, we have shown that wall writers are able to overcome (or ignore) the constraints of either the illegality of their work or of the severe limitations imprisonment places on one’s freedom of expression, and consequently the politically contentious position their opinions place them in. In the context of contemporary graffiti and street art, these wall writers display repeated behaviours, in much the same way as mobile hunter-gatherer groups return to the same location seasonally, re-using the traditional fire pit, sleeping and butchery areas. In this way, wall writers create stratigraphies or palimpsests by writing their identities and ideas often on the same physical spaces around them, seeing them removed or destroyed by authoritative forces, only to write them back again. Berlin’s East Side Gallery is a well-known (albeit officially sanctioned) example of this, where historic post Cold War-era artworks are now repainted in the name of conservation, either by the original artists or others now replicating their work.

There is a perpetual struggle for expression amongst wall writers in which they often defy either the law, the authoritatively defined urban aesthetic, or the normatively proscribed acceptable ideologies. It is a natural part of existence for these wall writers, but it also illustrates something very important about them as wall writers and about the society they interact with.

As we saw earlier, there is evidence in both the ancient and historic past of graffiti functioning as an important part of the built environment and marking where people spent their time and the values they attached to the various places they encountered (Benefiel Citation2010, 60). Within these settings, graffiti were often not considered acts of vandalism but as part of everyday life. In the eighteenth century, for example, it was not regarded as criminal, only being described as an immoral act when the content itself was deemed offensive (Cody Citation2003, 96). Through its association with illegality in the twentieth century, the act of wall writing itself became increasingly associated with rebellion and resistance.

Amongst other things, our collaborative work shows that a seemingly fundamental and persistent element of identity amongst wall writers is the refusal to accept attempts to prevent them expressing themselves and a refusal to suffer either physical or ideological erasure. It also gives a sense of where the authoritative boundaries for acceptable expression are. It shows this in two important ways. The first is that, by identifying the spaces where graffiti have been removed, we can identify where someone felt the need to control the space in appearance or ideology by returning it to a former state. The second is that by observing where graffiti are allowed to persist, we can identify the spaces that modern societies often consider less valuable. These spaces are often disused or abandoned, populated by the politically or economically unacknowledged and suppressed, or by those incarcerated. Where graffiti are allowed to persist says as much about the society they exist in, and their values, as where they are erased. Of course, spaces where all graffiti is either removed or permitted represent points near the ends of a spectrum ranging from no authoritative control to complete authoritative control. Most contemporary graffiti are produced in spaces more toward the centre of this spectrum, spaces where the graffiti persist until they are deemed a nuisance, an inconvenience, or an offence, at which point they are then removed. Furthermore, changing attitudes towards particular graffiti can show how social and political discourse shifts over time. For example, although conscientious objectors (CO) were viewed as cowards and vilified by many during the First World War, later generations have recognised the incredible bravery and courage in the CO’s resistance to immense social pressure, a defiance which caused them to experience great hardships, physical brutality and the very real threat of death. Consequently, graffiti can provide both a form of historic evidence of these marginalised perspectives whilst also showing how later recorders recognize the importance and value of these past messages.

This collaborative work has also demonstrated how modern wall writing is ideologically or aesthetically contentious, meaning that the writers who produced it find themselves in a paradox of marginalization. Wall writers who produce work that violates the law, and/or the authoritative ideological structures, find themselves marginalized in that the agents of authority will seek to prevent them from wall writing in many ways, not the least of which are increased surveillance, fines, police harassment or assault, and imprisonment. However, being a wall writer also resists marginalization in the sense that it allows those whose views fall outside of the narrow parameters of publicly acceptable expression to express themselves anyway. These expressions demand recognition. They represent people who refuse to be ignored, forgotten, or silenced. And in so doing they resist the marginalization that ideological, political, religious (or otherwise) hegemony forces onto the population.

Conclusion

Wall writers are free to express themselves as they see fit, often refusing to comply with what is hegemonically allowable. Perhaps this freedom also existed amongst artists using caves for their artworks in the Palaeolithic? But by occupying that counter-hegemonic position they often run counter to an authority that seeks to silence, punish, and amalgamate them. Graffiti can provide crucial evidence of those who, feeling in some way marginalized, are trying to overcome that feeling by demanding recognition. Yet it is also evidence enough for some to consider these graffiti worthy of erasure, to silence the wall writers, hiding their message, both in the present and from the future. It is then only the very determined, the very dedicated, the unwavering who continually write themselves onto the walls of society and thus into its history that achieve what modern graffiti writers call ‘fame’ but what is more commonly called historical recognition.

Acknowledgments

Emma Bryning’s PhD research is funded by the AHRC through a Collaborative Doctoral Award between English Heritage and the University of York, under the supervision of Megan Leyland and John Schofield. Charlie Kendall’s PhD research is internally funded through York St John University. He is supervised by Matthew Spokes and Tyson Mitman. The Richmond Castle Cell Block project was made possible thanks to a generous grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and through the work of a dedicated team of English Heritage staff and volunteers among others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emma Bryning

Emma Bryning is a PhD student at the University of York funded through the AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership scheme and involving English Heritage. Her project explores heritage aspects of historic and contemporary graffiti. Prior to starting her PhD, she worked in a variety of heritage roles, including as Learning and Community Officer and Visitor Experience Manager for the Monastery Manchester. In addition to graffiti, her research interests include the intersection of contemporary art and heritage; the interpretation and presentation of heritage and historic sites, and performance art.

Charlie Kendall

Charlie Kendall is a PhD student at York St John University. His research examines how heritage, historical memory, and structural powers interact to form how a city thinks of itself and makes use of its space.

Megan Leyland

Megan Leyland is a Senior Properties Historian at English Heritage where she researches and creates interpretation on sites in their care,‘and in particular country house’. Since joining the organisation in 2015, Megan has worked on a range of projects including the Richmond Castle Cell Block Project (North Yorkshire), Marble Hill Revived (London), and new interpretation at Kirby Hall (Northamptonshire). Megan has a particular interest in how lesser known or underrepresented histories are told at heritage sites.

Tyson Mitman

Tyson Mitman is a senior lecturer in Sociology and Criminology and Course Lead for Criminology at York St John University. He studies subcultures, public aesthetics, and spatial politics. His interests lie in how individuals use public space to construct their subjectivities as well as how their interaction with space produces positionality and a type of political discourse. He is the author of The Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics and the Reimagined City in Philadelphia.

John Schofield

John Schofield is Professor of Archaeology at the University of York, UK where he is also Director of Studies in Cultural Heritage Management. Prior to joining the University of York in 2010, John spent 21 years with English Heritage working in policy and heritage protection. John has adjunct status at Griffith and Flinders universities in Australia, and is Docent in Archaeology and Museology at the University of Turku, Finland. John’s current research focuses on the contributions archaeology can make to contemporary real world problems such as environmental pollution, social injustice and crime.

References

- Abaza, M. 2016. “The Field of Graffiti and Street Art in post-January 2011 Egypt.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 318–333. London and New York: Routledge.

- Anderson, S., and W. Verplanck. 1983. “When Walls Speak, What Do They Say?” The Psychological Record 33 (3): 341–359.

- Baird, J.A., and C. Taylor. 2016. “Ancient Graffiti.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 17–26. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ballesta, J., and Á. Rodríguez Gallardo. 2008. “Camposancos: una ‘imprenta’de los presos del franquismo.” Complutum 19 (2): 197–211.

- Benefiel, R. 2010. “Dialogues of Ancient Graffiti in the House of Maius Castricius in Pompeii.” American Journal of Archaeology 114 (1): 59–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.1.59.

- Booth, K. 2020. “The Only Thing I Can Draw.” Traditional Paint News 4 (2): 21–28.

- Bopearachchi, O., and K. Rajan. 2002. “Graffiti Marks of Kodumanal (India) and Ridiyagama (Sri Lanka)—a Comparative Study.” Man and Environment XXVII 27 (2): 97–106.

- Borck, L. 2016. “Graffiti bombing in U.S. National Parks: Or Vandalism, Rock Art, and Banksy.“ Access date February 7 2022. https://www.sapiens.org/culture/graffiti-bombing-in-u-s-national-parks Sapiens.

- Boulton, D. 1967. Objection Overruled. London: Dales Historical Monographs. 2nd. Republished in revised edition in 2014 by Dales Historical Monographs and the Friends’ Historical Society.

- Breuil, H., and L. Capitan. 1901. “Une nouvelle grotte avec figures peintes sur les parois à l’époque paléolithique.” Académie des Sciences Compte rendu 133: 478–480.

- Burnham, K. 2014. The Courage of Cowards: The Untold Stories of the First World War Conscientious Objectors. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

- Burton, J., and M. Farrell. 2013. ““Life in Manzanar Where There Is a Spring Breeze”: Graffiti at a World War II Japanese American Internment Camp.” In Prisoners of War: Archaeology, Memory and Heritage of 19th and 20th Century Mass Internment, edited by H. Mytum and G. Carr, 239–269. New York: Springer.

- Casella, E. 2001. “To Watch or Restrain: Female Convict Prisons in Nineteenth-Century Tasmania.” International Journal of Historic Archaeology 5: 45–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009545209653.

- Castleman, C. 1984. Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York. Mass.: MIT Press.

- Champion, M. 2015. Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England’s Churches. London: Random House.

- Chippindale, C., and P.S.C. Taçon. 1998. The Archaeology of Rock-Art. Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Clarke, A., U. Frederick, and P. Hobbins. 2017. “‘No Complaints’: Counter-Narratives of Immigration and Detention in Graffiti at North Head Immigration Detention Centre, Australia 1973–76.” World Archaeology 49 (3): 404–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1334582.

- Cocroft, W., D. Devlin, J. Schofield, and R.J.C. Thomas. 2006. War Art: Murals and Graffiti–Military Life, Power and Subversion. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Cody, L. 2003. “‘Every Lane Teems with Instruction, and Every Alley Is Big with Erudition’: Graffiti in Eighteenth-Century London.” In The Streets of London, edited by T. Hitchcock and H. Shore, 92–111. London: Rivers Oram Press.

- Eaton, H. 1918. “Thoughts & Experiences during the Great War.” Photocopy of unpublished MS, held at Peace Pledge Union Archive.

- Ellsworth-Jones, W. 2008. We Will Not Fight, the Untold Story of the First World War’s Conscientious Objectors. London: Aurum.

- English Heritage. 2020. Cell Block. English Heritage Booklet.

- English Heritage. (n.d.a). “First World War conscientious objectors at Richmond Castle.” Accessed 10 March 21. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/richmond-castle/history-and-stories/richmond-sixteen/

- English Heritage. (n.d.b). “The Richmond Castle Cell block project.” Accessed 10 March 21. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/richmond-castle/richmond-graffiti/cell-block-project/

- Frederick, U. 2009. “Revolution Is the New Black: Graffiti/Art and Mark-making Practices.” Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress 5: 210–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-009-9107-y.

- Frederick, U., and S. O’Connor. 2009. “Wandjina, Graffiti and Heritage: The Power and Politics of Enduring Imagery.” Humanities Research XV (2). doi:https://doi.org/10.22459/HR.XV.02.2009.10.

- Gaudie, N., 1916. “Diaries of Norman Gaudie.” [Diary] Held at: University of Leeds. Liddle/ WW1/ CO/ 038

- Goodall, J. 2016. Richmond Castle and Easby Abbey. English Heritage Guidebooks. Printed in England by Geoff Neal Group.

- Halsey, M., and A. Young. 2006. “Our Desires are Ungovernable: Writing Graffiti in Urban Space.” Theoretical Criminology 10 (3): 275–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480606065908.

- Houlbrook, C. 2021. Unlocking the Love-Lock: The History and Heritage of a Contemporary Custom. New York and Oxford: Berghahn.

- Kramer, A. 2014. Conscientious Objectors of the First World War: A Determined Resistance. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. 1967. “Treasures of Prehistoric Art.” Translated from the French by N Guterman. New York: Abrams.

- Martin, F. 2016. “American Indian Graffiti.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 124–136. London and New York: Routledge.

- McAtackney, L. 2016. “Graffiti Revelations and the Changing Meanings of Kilmainham Gaol in (Post) Colonial Ireland.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20 (3): 492–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0355-4.

- McMahon Flatt, J.M. 2018. The Ghosts of the Great War: Reflections on Belgium. iUniverse.

- Mitman, T. 2018. The Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics and the Reimagined City in Philadelphia. Chicago: Intellect Books.

- Obłuski, A., and J. Maczuga. 2021. “Pictorial Graffiti from the Ghazali Northern Church, Sudan: An Overview.” Journal of African Archaeology 19:187–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/21915784-20210014. published online ahead of print 2021.

- Palmer, R. 2016a. “Religious Colonialism in Early Modern Malta: Inquisitorial Imprisonment and Inmate Graffiti.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20 (3): 548–561. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0359-0.

- Palmer, R. 2016b. “The Battle for Public Space along the Mapocho River, Santiago de Chile, 1964-2014.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 258–271. London and New York: Routledge.

- Peteet, J. 2016. “Wall Talk: Palestinian Graffiti.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 334–344. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ralph, J. 2014. “Graffiti Archaeology.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith. 3102–3107. New York, NY: Springer . doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_551.

- Ross, P. 2020. A Tomb with A View: The Stories and Glories of Graveyards. London: Headline.

- Rukwaro, I.W., and S.M. Maina. 2020. “Graffiti Artists in East Africa.” Africa Habitat Review Journal 14 (2): 1869–1885. http://uonjournals.uonbi.ac.ke/ojs/index.php/ahr/article/view/534/553

- Samson, A., L. Wrapson, C. Cartwright, D. Sahy, R. Stacey, and J. Cooper. 2017. “Artists before Columbus: A Multi-method Characterization of the Materials and Practices of Caribbean Cave Art.” Journal of Archaeological Science 88: 24–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2017.09.012.

- Sanghera, S. 2021. Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain. London: Viking Press.

- Snyder, G. 2009. Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. New York and London: New York University Press.

- Waldner, L., and B. Dobratz. 2013. “Graffiti as a Form of Contentious Political Participation.” Sociology Compass 7 (5): 377–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12036.

- Walker, P., A. Allegretti, and B. Quinn. 2021. “Anger Grows at Offer of 1% Pay Rise for NHS Staff.” The Guardian, 6 March 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/mar/05/anger-grows-at-offer-of-1-pay-rise-for-nhs-staff

- Wilson, J. 2008. Prison: Cultural Memory and Dark Tourism. New York: Peter Lang.

- Yamakoshi, H., and Y. Sekine. 2016. “Graffiti/street Art in Tokyo and Surrounding Cities.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J.I. Ross, 345–356. London and New York: Routledge.