ABSTRACT

This paper considers the Early Neolithic phase of activity on an axehead quarry at the Eagle’s Nest, Lambay, a small island off the east coast of Ireland. The site is best known for activity in the later Neolithic and its cultural connections with the developed passage tomb tradition. One area of the site has produced evidence for quarrying from the thirty-eighth or thirty-seventh century cal BC, supplying secure evidence that axe production was integral to the Neolithic material world in Ireland from the beginnings of this period. Porphyritic andesite would seem a counter-intuitive choice to make stone axeheads, its naturally occurring internal fissuring resulting in a high likelihood of failure during working. On the other hand, when ground and polished it has a very distinctive visual appearance and texture with a lustrous quality. This paper examines the ontological significance of this transformation from source to special objects.

Introduction

The transition to the Neolithic across Europe is notable for a step change in the range of social relationships and materials that we see in the archaeological record (e.g. Boríc et al. Citation2013, 45). This is not to underplay the complexity of preceding Mesolithic material worlds. Instead, as Herva and colleagues (Citation2014, 141) put it, we see in the early phases of the Neolithic engagements with new materials and practices that changed people’s perception, experience and understanding of the world, forming broader cultural lifeways (see relevant discussion in Conneller Citation2011, 125).

One area where this can be seen is in the production of stone axeheads from particular lithic sources by quarrying or from underground flint mines (Cooney Citation2015). The beginning of the Neolithic saw important changes in the character of axes and the conditions of their production (Edmonds Citation1995, 50; Cooney Citation2008, 208–209). Recognising the long-established practice of quarrying in the Mesolithic of western Scandinavia (Nyland Citation2016), using primary sources for axehead production can more generally be considered a characteristic feature of the Neolithic of north-west Europe (see Schauer et al. Citation2021). Effort was put into the appearance and texture of these axeheads, with these qualities enhanced through grinding and polishing (Whittle, Bayliss, and Healy Citation2011, 876). As important as the stone itself was the place from which it came. Indeed, island exploitation sites along the Atlantic façade point to the perceived potency of island outcrops across this region (Cooney Citation2015, Citation2017).

One such island setting was the Eagle’s Nest, Lambay, off the east coast of Dublin, Ireland. Here, outcrops of porphyritic andesite (Lambay Porphyry), part of a suite of Ordovician volcanic rocks that dominate the geology, along with the occurrence of sedimentary lithologies, including Old Red (Devonian) Sandstone (Stillman Citation1994), were quarried episodically through the fourth millennium cal BC. In contrast to most European Neolithic axe quarries, all stages of axe production are represented, from initial quarrying and blocking out, the production of roughouts and the grinding and polishing of axeheads. As part of a range of depositional activities, axeheads were also deliberately deposited, making this an exceptional stone axe quarry (Bradley Citation2019, 8; Topping Citation2017).

The porphyritic andesite from the Eagle’s Nest is potentially of wider ontological significance in interpreting the role of axeheads in Neolithic societies, not least because from a functional perspective this stone is materially a counter-intuitive choice to make such objects. Furthermore, activity at this quarry and the production of axeheads continued over the fourth millennium cal BC. Post-excavation analysis, for example on the pottery assemblage from the site (Sheridan Citation2022), has shown its use in the later fourth millennium cal BC and strong connections with the developed megalithic passage tomb tradition (e.g. Cooney Citation2005, 26).

While Early Neolithic activity at the site has previously been noted (Cooney et al. Citation2011, 601–03), this paper specifically focuses on the quarrying and production of stone axeheads in this early phase, from the thirty eighth or thirty seventh century cal BC (). It is clear that the major Neolithic source for stone axeheads in Ireland, a metamorphic rock porcellanite, quarried at Tievebulliagh and at Brockley on Rathlin Island, both in Co. Antrim in northeast Ireland (Cooney Citation2000, 162–3; Cooney et al. Citation2012; Mallory Citation1990; Mandal et al. Citation1997; Sheridan Citation1986) was in use in the Early Neolithic, for example, in rectangular houses dating from 3720 to 3620 cal BC (Smyth Citation2014). However, the Eagle’s Nest quarry is the only location in Ireland where we have direct evidence for organised quarrying and axe production at this time. Crucially, this connects it with the broader European phenomenon of being part of an accretive material culture package associated with the transition to agriculture (see Schauer et al. Citation2021; Whittle, Bayliss, and Healy Citation2011, 876). This important production site also allows us to interrogate the tension between and challenge of explanations pitched at a European scale and those in which regional traditions are emphasised (Edmonds Citation2012, 1195). Why this particular location? What was the significance of this stone? What are the wider implications for our understanding of the ontology of the Early Neolithic world?

Early Neolithic quarrying and axehead production at the Eagle’s Nest

Lambay porphyry is a distinctive grey-green (less commonly purple) basaltic andesite with pale green platy phenocrysts of plagioclase up to 2 cm in length (Mandal Citation1996; Stillman Citation1994). The quarry () is located at 100-120 m OD, close to the highest point of the island and consists of two small valleys defined by porphyritic andesite outcrops, forming a distinctive topographical unit. The northwest-southeast orientation of the valleys coincides with the direction of ice flow during the Late Devensian/Dublin ice sheet (Hoare Citation1975, fig. 5; McCabe Citation2008, fig. 6.5), resulting in the glacial polishing and striation of the outcrop surfaces.

Figure 2. The location of the Eagle’s Nest site in relation to the geology of Lambay (after Stillman Citation1994). The major areas of excavation are shown and the location of Cutting 11 indicated.

In the larger eastern valley, there is evidence of quarrying and related depositional activity in the Middle Neolithic, after 3,400 cal BC (Cooney Citation2005; Sheridan Citation2022). Here radiocarbon dates also suggest possible Early Neolithic activity (Cooney et al. Citation2011, 601–03). Substantial evidence for the quarrying and working of porphyritic andesite from the initial phases of the Irish Neolithic only comes from the smaller valley to the west (Cutting 11, ). A key characteristic of this Early Neolithic evidence is the repetition of activity patterns within the stratigraphical sequence of archaeological deposits. This indicates a repeated, habitual approach to stone working as well as the establishment and maintenance of spatial arrangements and human engagement with the material over time.

Aside from a thin deposit of material on top of the higher part of the quarried outcrop (Cutting 11 E), the main build-up of debitage was to the west of the lower rock face. This had a maximum depth of 0.60 m and extended for up to 6 m from the rock face. Despite the challenges of excavating in situ quarry debris, five discrete and widespread surfaces were recognised in the debitage, each with a depth of 0.10–0.20 m. These major surfaces had a weathered appearance and a proportion of the debitage carried glacial striae (as does unquarried bedrock below the debitage), indicating that the focus was on quarrying the surface areas of the rock face, with some removal of material behind it (). Interspersed between these were more spatially discrete contexts relating to particular working episodes and activities (). Technological analysis of these contexts was carried out during excavation and two column samples were analysed in post-excavation. Additionally, a programme of experimental reduction of porphyritic andesite blocks and production of axeheads was carried out. In combination, these analyses provide a detailed picture of the technological ensemble; from quarrying, block reduction to roughout stage and beyond.

Figure 3. Eagle’s Nest Cutting 11. Schematic north-facing section and plan of context surfaces C1109 and C1107, C1108, 1110 and 1111), with Carinated Bowl from C1109 (drawing by Marion O’Neil).

While there were repeated phases of activity showing distinct spatial patterns, we focus here on the third major layer of debitage (C1109), with the original soil/paleosol (C1107) beyond it to the west, containing pieces of porphyritic andesite, sandstone and struck flint (). On this surface, there were a number of blocks up to 0.30 m in maximum size, suggesting that quarrying took place. Over its southwestern area there was a dominance of smaller pieces of porphyritic andesite, the highest number of diagnostic removals of any context and a number of what appear to be preliminary or rejected roughouts (C1108).

Adjacent to the bedrock was an area of angular pieces of porphyritic andesite dominated by pieces up to 15 cm in maximum dimension representing the residue of broken up bedrock (C1110). About a metre out from the outcrop a distinctive large block of bedrock had been left in place since the initial phase of quarrying and remained visible up to the final debitage surface. This may have been used as an anvil on which blocks were broken. This ‘anvil’ provided a pivot and articulation for activities, as demonstrated by the line of large slabs running for up to 2 m west from it. Some of these slabs were placed on their side forming a distinct ‘spine’ to the context. Immediately west of the block and south of the ‘spine’ a deposit of porphyritic andesite (C1111) fills a hollow in C1109. Close to the southern edge of this ‘spine’ a cluster of pottery sherds represents the deposition of an Early Neolithic Carinated Bowl (Sheridan Citation2022).

A charcoal sample of Prunus sp. provided a date of 3810–3665 cal BC (SUERC-4131) for C1109. A charcoal sample of Prunus sp. from the next major surface above (C1106) provided a date of 3755–3640 cal BC (SUERC-4129). The radiocarbon dates from C1109 and C1106, allied to the deposition of Carinated Bowl pottery in these contexts and in the latest major surface (C1103), support the interpretation that Cutting 11 presents a phase of quarrying and axe production during the thirty eighth or thirty seventh centuries cal BC.

The character of Early Neolithic axehead production at the Eagle’s Nest

The most direct evidence for the production of axeheads are roughouts and the associated debitage, revealing details about the primary percussive reduction sequences as well as indications of approach(es) to grinding. Added to this are artefacts used to carry out these processes, including hammerstones, anvils, grinding stones and small polishing stones. In combination, this evidence provides an opportunity to investigate how production was enacted, as well as how actions and space defined one another.

If stone axehead production is considered as a purely mechanical act (recognising of course there was more to it than that for the axe maker) the objective is the production of a ‘thing’ that is recognisably and functionally an axe. Within the academic literature, most production sequences have been characterised as a linear chaîne opératoire, including varying amounts of knapping, pecking, grinding, and polishing (e.g. Bradley and Edmonds Citation1998; Ballin Citation2013; Nyland Citation2019, table 5.1). Less well considered perhaps are how these sequences might have been practically articulated and how various stages related to one another.

Each stage is intended to remove material, facilitating shaping and refining with varying degrees of control. Flaking removes large amounts of material in a short timespan, but in a relatively uncontrolled manner. While acknowledging pecking is not always employed, it can be used to reduce areas where flaking is not possible (e.g. the middle of roughout faces) and/or to regularise the surface of an axe to facilitate grinding (Cooney et al. Citation2019, 54; Gilhooly Citation2018; Stroulia Citation2003, 9–12). This action removes a relatively small quantity of material but with much more control than flaking.

Grinding allows the roughout shape to be refined and details added. This is where axe makers spent most of their time, honing the roughout from primary shape into a usable object. Whereas grinding uses abrasive friction to remove relatively large amounts of material over longer time frames, polishing removes very little, effectively burnishing the surface of the stone both for functional and aesthetic reasons (see Dickson Citation1981, 32; Yerkes et al. Citation2003, 1054 for the former, and Cooney Citation2002, 98; Tsoraki Citation2011 for the latter). The precise relationship between grinding and polishing in many stone axe traditions is not well understood (see Dickson Citation1981, 45–46). That said, at the Eagle’s Nest there is evidence for polishing on axes themselves and the use of small polishing stones.

Percussion

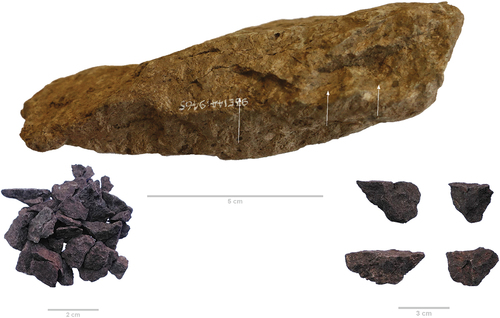

Once a suitably sized and shaped piece of porphyritic andesite had been obtained after extraction and initial blocking out the first major action used to remove material quickly was percussion, which was either (or interchangeably) flaking or pecking. Due to its large-grained phenocrysts, porphyritic andesite does not flake well or consistently. Consequently, flake removal sequences or building new platforms are not possible in any meaningful way, limiting detailed shaping of roughouts. Instead, only opportunistic removals are possible as the roughout morphology allows. This strategy is clearly identifiable along the edges of some roughouts where isolated or small numbers of flake detachment scars are evident ().

Figure 4. Porphyritic andesite roughout (93E144:9465, C1103) from Cutting 11 with white arrows indicating flake removal scares. Note the rough texture and step fracturing, which is characteristic for this lithology. Lower left shows chips produced during percussion (either flaking or pecking) and lower right shows characteristic D-shaped flakes produced from this lithology.

Porphyritic andesite flakes are much less regular than those struck from finer-grained lithologies, but in many cases they still preserve some diagnostic features. They are usually small, D-shaped (or variants of) and in many cases have identifiable platforms (). Although dorsal and ventral faces are distinguishable, their rough textures tend to obscure other more subtle diagnostic features. As might be expected, these flakes are present in most contexts in column samples from Cutting 11.

Experimental work demonstrated that it is possible to produce morphologically identical flakes while pecking, particularly along thinner edges where the angles allow for conchoidal-like detachment. Correspondingly, it seems likely these flakes represent both these actions, although most derive from formal flaking as this action produces them in higher frequencies. This is corroborated by the presence of roughouts with flake detachment scars and no pecking as well as large amounts of diagnostic chips consistent with platform preparation ().

There is abundant evidence for pecking from roughouts, hammerstones and small stone anvils. Roughouts have been identified with pecking damage primarily along their sides. Limiting pecking to these specific areas suggests the intention of the axe makers was to strategically remove material before grinding, rather than creating an all-over regular surface, as seen in some other traditions (e.g. Stroulia Citation2003, 9). It also implies a desire to minimise percussion as, even in the pecking phase, previously formed cracks can develop and new ones form. Two hammerstones from Cutting 11 made from quarried porphyritic andesite could have been used for either pecking or knapping. They are sized to fit well into the hand and can be distinguished from other quarried material by slightly round or oval morphologies, pocked markings on specific areas from repeated striking and relative heaviness compared to other porphyritic andesite pieces.

Three roughly palm-sized sandstone cobbles and one potential gabbro example with distinct use damage were also identified. Concave dishing in the middle of at least one face is characteristic of this group, seemingly caused by numerous deep gouges and scrapes. These objects appear to be stone anvils, placed under the roughout during pecking (). When this system is replicated experimentally, similar damage forms on the stone anvils as they are indirectly percussed through the roughout, particularly while pecking the sides. This type of pecking can also produce bi-polar flake removal, either from the hammerstone in contact with the upper side or the anvil in contact with the lower. Additionally, this highlights that pecking could be employed early in the reduction sequence, even before or in place of flaking.

Figure 5. Upper images show stone anvils excavated from Cutting 11 (left to right − 93E144:9663, 93E144:9661, 93E144:15412, C1107) with an experimentally produced version upper right. Lower image depicts how this sequence is proposed to have operated using a quarried porphyritic andesite hammer stone (93E144:8633, C1103), roughout (93E144:10961, C1108) and anvil stone (93E144:15412).

Abrading

Flexibility in the use of flaking and pecking can also be extended to grinding, to which materially porphyritic andesite is well suited. Most production time was spent on this phase when the largest amount of material was removed. Experiments replicating this reduction sequence demonstrate that grinding removes c. 80% of the weight of roughouts, taking approximately 6 hours to complete (). This compares with the time Bradley and Edmonds (Citation1998, 89) provide for the results of experimental production of tuff axeheads from the Great Langdale, Cumbria source, although they do not distinguish between grinding and polishing.

Figure 6. 100% stacked column graph showing results from the experimental reproduction of 3 porphyritic andesite axes following evidence from Cutting 11.

Numerous intact and fragmentary grindstones as well as an axe roughout with a partially ground blade and another with a ground face provide the best evidence for grinding. Importantly and somewhat counter-intuitively given how easily it is ground, all the larger grinding stones (including fragments) are themselves made of porphyritic andesite. Correspondingly, to understand their place within the production sequence on the site, a detailed experimental study was carried out by Knutson (Citation2023).

This research characterised the specific use-wear on porphyritic andesite grindstones after grinding roughouts using three different ‘actions’; dry, with water only, and with water and beach sand as an abrasive. In this experiment, only those actions involving water and water/sand were macroscopically and microscopically analogous to archaeological examples from the Eagle’s Nest (Knutson Citation2023, 37–38, 42). That this action, in some cases at least, was specifically grinding, as opposed to polishing, can be seen in linear axe-grinding grooves running the length of grindstones made when shaping sides or blades (). This interpretation is supported by the fact that much less material was removed from experimental roughouts over time where water alone was used, potentially indicating polishing (, see below).

Figure 7. Lower image shows experimentally produced grindstone (Knutson Citation2023) with characteristic damage following grinding with water and sand as an abrasive. Here, linear grooves can be seen running in the direction of the grinding action. Upper right is a fragment of an artefact from C1107, Cutting 11 (93E144:9709) showing the same macro damage. The white lines indicate two grinding grooves flanking a corresponding ridge.

Figure 8. Line graph comparing the amount of material removed from porphyritic andesite roughouts using sand/water and water only grinding techniques over 5 hours each. In the early stages grinding using water alone removes slightly more material but this is temporary.

Additional to the larger grindstones, a small number of coarser-grained pebbles with distinctive grind patterns were noted, the best example being a water-rolled sandstone pebble from C1103. Unidirectional striations indicating use in grinding are evident on at least two of its surfaces, with one ground to a distinct concavity (). Due to their relatively small number, it appears these were used less frequently and perhaps represent only detailed work, such as the removal of facet ridges or detailing the butt profile. Interestingly, both the larger porphyritic andesite grindstones and these smaller grinding pebbles are distinct from other ‘polishing stones’/grindstones identified at sites in the Bann valley, Northern Ireland, Ferriter’s Cove, Co. Kerry (see discussion in Woodman Citation2015, 158) and on Dalkey Island, Co. Dublin (Leon Citation2005).

Figure 9. Comparison of porphyritic andesite ground (left) and polished (right) surfaces, showing the contrast between the decidedly matt finish on the former and the glossy finish to the latter. Accompanying the roughout fragment (93E144:7091, Test Pit 7) with the ground surface is a small sandstone pebble (E93144:9469, C1103) with at least two surfaces used in grinding, one of which is concave. Accompanying the polished flake (93E144:8688, C1101) is a small quartz polishing stone (92E144:9859, C1107) with clear glossing on one side.

There is relatively little direct evidence for polishing, the final step in the production of these stone axeheads. This stage, however, is implied by a polished axehead fragment from the cultivation soil level in Cutting 11 which is likely to originate from the archaeological deposits beneath (). After grinding, this lithology has a matt finish and texture, which appears very different to polished porphyritic axeheads in the archaeological record.

Polishing is best achieved using stones of a similar hardness and texture, allowing both to develop burnished surfaces. The finish can be enhanced using water and micro abrasives, such as charcoal dust or ash (Cooney and Mandal Citation1998, 13). In Cutting 11, some porphyritic andesite ‘grindstones’ appear to have been used with water but without sand (Knutson Citation2023, 43). These have generally smooth surfaces and much less use-wear than others. As such, it seems reasonable to interpret them as forming part of the polishing process, perhaps the initial stages where large parts of the body of the object are finished.

Additionally, detailed polishing was carried out using smaller pebbles, which have also been identified. An excellent example of this is a small quartz pebble with distinct patches of glossy polish across its surface (). On Mainland Shetland, Scotland, comparable objects are also known, used to polish riebeckite felsite axeheads from the quarry complex at North Roe (Cooney et al. Citation2019; Megarry et al. Citation2021, 5–6).

Discussion

Nyland (Citation2019, 68) emphasised that the fundamental interpretative premise of the chaîne opératoire approach should be to recognise expressions of cultural or social identity intertwined in technology and the production of artefacts. The excavation of the porphyritic andesite quarry at the Eagle’s Nest and the making practice developed through our experimental work have provided a sophisticated understanding of the approach to quarrying and axehead production that could resonate with the experience of Early Neolithic people who used this site (Elliott Citation2019, 166, 164).

As a result of the detailed excavation of this quarry we are able to reveal this high-resolution picture of production. It has not only provided evidence for a compelling sequential understanding of activities, but through the identified stratigraphic horizons, it is clear that this approach was repeated multiple times while the quarry was in use during the Early Neolithic. As they carried out activities stone workers would have talked, co-operated and compared tasks (Murphy Citation1997, viii), remembering and materialising how things had been done since quarrying commenced.

Recognising the aesthetic qualities of the stone and its potential to be polished from the glacially striated outcrop surface, the first action in quarrying porphyritic andesite was to remove this exterior surface. The resulting blocks were then reduced down and tested for flaws. Moving slightly away from the quarry face, suitable axehead material was sorted into clusters of morphologically similar pieces.

In the initial stages of axehead reduction that followed, hammerstones made of quarried porphyritic andesite were interchangeably used to flake and peck roughouts, further testing them in the process. Where porphyritic andesite’s inability to withstand successive striking was an issue, for example in the use of small anvils, other lithologies were used. From the distribution of debitage it seems that percussion happened at various locations within the quarry, but perhaps more so towards the outcrop.

Further back from the quarry face, from the evidence of grindstone fragments and partly ground roughouts, appears to have been a focal point for abrasion. This action was the primary articulation of skill in the making of these axeheads, also requiring the greatest amount of time and effort. Importantly, while porphyritic andesite might not seem naturally suited to the task of abrasion, it held a major role as both grinding and polishing stones, themselves interchangeable to a degree. Our experimental work shows these were made more versatile through the use of lubricants (water) and abrasives (sand, possibly ash and charcoal), providing a sense of the role of more intangible but still necessary elements in this process. The only evidence for the use of non-porphyritic andesite in grinding comes from a small number of sandstone pebbles, again only used where porphyritic andesite was not suitable.

General polishing could also have taken place on some of these grindstones, with smaller polishing stones used for more refined work. Here is the only instance where the apparent repeated emphasis on using and augmenting porphyritic andesite is broken by the use of small polishing stones of other lithologies. It is important that there is no evidence for the use of porphyritic andesite water-rolled pebbles, which are widely available in different sizes from beaches on the coasts of Lambay. A range of reasons might explain this, but one key point is that, unlike all the utilised porphyritic andesite tools from Cutting 11, these pebbles would not have been made from quarried stone. This drives home the importance of place as well as people’s interactions with the quarry and quarried porphyritic andesite.

What is interesting in this particular method of axe production is that earlier phases of production can be obscured (see Elliott Citation2019, 171) but crucially a key aim, achieved through the use of porphyritic andesite grind stones, appears to be the recovery of the original glacially striaed outcrop surface as a material property of axes. Other tools made from quarried porphyritic andesite used in the production of axeheads here reinforce the strong sense that the makers felt a need to engage with this specific stone source wherever they could. This was clearly not an expedient use of a local material for axehead production, but an approach that involved knowledge, care and respect both for the source and the objects made (Olsen Citation2013, 153).

This was a specific type and time of engagement with this lithic source, as demonstrated by an apparently different mode of axehead production during the Middle Neolithic, from 3500 to 3400 cal BC on. Kelly’s (Citation2021) analysis of coarse stone tools shows this involved the widespread use of other lithologies, most notably the local Old Red Sandstone, for hammerstones, grinding stones and rubbers. At this time, there was also a focus on the production of miniature axe heads (O’Toole Citation2018). All of this appears to be related to the cultural world of the developed megalithic Irish passage tomb tradition which brought the activities at the Eagle’s Nest quarry into a wider Irish Sea world (Cooney Citation2005, 26).

That this focus on quarried porphyritic andesite to produce stone axeheads, and other tools used in their production, is specific to the Early Neolithic is also demonstrated by the presence of Carinated Bowl pottery, which is seen alongside extraction and organised axe production as one of the indicators of changed material relationships between people and things from the start of the Neolithic in Britain and Ireland (Edinborough et al. Citation2020; Pioffet Citation2014; Sheridan Citation2007). There are several vessels in Cutting 11 and petrological analysis suggests the possibility that the pottery was made off the island and brought to the site (Quinn Citation2022; Sheridan Citation2022). Comparanda for the Eagle’s Nest pottery can be found in Early Neolithic assemblages in eastern Ireland and elsewhere around the Irish Sea, for example southern Scotland (Pioffet, pers comm). Lipid analysis of sherds from the Carinated Bowls indicates vessel use that is strongly linked to dairy products, a pattern seen more widely in Ireland and Britain (Olet, Evershed, and Smyth Citation2022; see discussion in Smyth and Evershed Citation2015) and a way of life centred on agriculture. Taken together, the evidence indicates how these various materials were integral components of this Early Neolithic world, shaped by and in turn assisting the shaping of human behaviour (Fahlander Citation2017, 77; Jones Citation2004, 330).

As elsewhere in Europe, the context of these new material relationships in Ireland and Britain is an important subject of debate. The evidence provided by aDNA (e.g. Cassidy Citation2023) provides a context for arguing that we should see these materials and the activities associated with them as the result of incoming people engaging with new landscapes and changing them; through agriculture, by the creation of monuments, the extraction and working of stone, and the production of pottery (e.g. Cummings and Richards Citation2021, 242–46). On the other hand, detail on the ground points to a more nuanced world of continuity of knowledge as well as change (Elliott et al. Citation2020; Smyth, McClatchie, and Warren Citation2020) across the Mesolithic/Neolithic transition. Lambay was certainly visited and settled at least on a seasonal basis during the Mesolithic (Dolan and Cooney Citation2010) and there seems to be some continuity in the use of ‘persistent places’ on the island. Given the overwhelming strength of the association with a Neolithic way of life for the earliest phase of quarrying at the Eagle’s Nest, contra Topping (Citation2017, 20) it cannot be seen as representing any evidence of Mesolithic outcrop quarrying. While there is some evidence for organised lithic production from primary sources during the Mesolithic period in Ireland (e.g. Little Citation2009), including a possibility that the use of the multi-period, Monvoy, Co. Waterford rhyolite quarry might have included axehead production (Kador Citation2007, Citation2009), the widespread use of stone axeheads of shale and schist appears to be based predominantly on secondary sources (e.g. Cooney and Mandal Citation1998, 85–86; Warren Citation2022, 116; Woodman Citation2015, 146–48; see comment in Little et al. Citation2017, 8).

Coming back to the questions of why the choice of porphyritic andesite, and why at the Eagle’s Nest, it is widely recognised that major axehead sources in different regions (Cooney Citation2002, Citation2015) tend to be visually distinctive. The classic examples are the green jadeitite, eclogite and omphacitite axeheads from Alpine sources that are widespread across Europe (Pétrequin et al. Citation2012). It has been suggested that these prompted the identification of alternative ‘greenstone’ sources in Britain and Ireland (Edmonds Citation2012; Miles Citation2016, 258–261; Sheridan and Pailler Citation2012). On reflection, is this view somewhat ontologically reductionist? Does it downplay the potential of local innovation and the recognition that stone was a focal resource in the Atlantic cultural sphere of the European Neolithic, involving the use of a wide range of rock types at a variety of scales (see discussion in Cooney Citation2008)? What did the green stone from the Eagle’s Nest quarry site mean to the local people who used it?

Gaydarska and Chapman (Citation2008) argue that in the Neolithic shining, brilliant objects of different colours, such as green, enabled the establishment of new links between things and phenomena, binding the world together in a new way. Porphyritic andesite also fits with a preference for axehead sources that include distinctive white/yellow speckles (Cooney Citation2015, 519), which could have different meanings, including an ancestral presence (Cooney Citation1998). The special character of axeheads made from this source was accentuated by grinding and polishing, connecting them, and many of the tools used to grind them, back to the striated outcrops at their place of origin at the Eagle’s Nest. In this deliberate focus on the surface and texture of both the outcrop and objects, there is a reminder of the argument of Herva et al. (Citation2014, 152) that the character of the surface of rock may have been perceived as having a latent potency, here realised through the production of axeheads.

Conclusion

Forty years ago, Ericson (Citation1984, 2) identified the challenges of working at stone mine and quarry sites where the material record is ‘shattered, overlapping, sometimes shallow, nondiagnostic, undatable, unattractive, redundant and at times voluminous’. Since then, our understanding of the significance of such sites has been enhanced by the application of new analytical techniques and the recognition that in many past societies stone was viewed as animate, alive with rich symbolic potential (Boivin Citation2004, 2). The approach taken here illustrates the value of a detailed analysis of a specific quarry site and its cultural context. In reflecting wider practices, the evidence from the Early Neolithic phase at the Eagle’s Nest demonstrates the importance and scale of cultural and social changes at this time and how these are implanted in and generated through everyday activities and detailed local knowledge as people realise the potential of materials, in this case porphyritic andesite, to achieve a new understanding of the world. People used this understanding to engage with and transform this specific stone into culturally charged and symbolically rich objects, helping us to understand how the grand narrative of the European Neolithic articulates with local and particular materials and contexts.

Alberti (Citation2016, 174) observed that an ontological approach implies that the entirety of the analytical apparatus and what is being studied should be included in the analysis. That perspective underpins the approach taken here in discussing the importance of the excavation of a stone axe quarry at the Eagle’s Nest, Lambay, Ireland, the significance of the use and transformation of particular outcrops of porphyritic andesite as a material for axeheads and its wider implications for our understanding of the ontology of the Early Neolithic world.

Author contributions

Gabriel Cooney is the project leader of the Eagle’s Nest post-excavation project. Brendan O’Neill and Bernard Gilhooly designed the experimental programme of axe production. Cooney and O’Neill developed the research perspective and wrote the bulk of the paper. Martha Revell conducted the technological analysis of the contexts in Cutting 11. Rachael Knutson carried out an experimental study of porphyritic andesite grindstones as an MSc thesis. All the authors contributed to the discussion and editorial process.

Acknowledgments

We are pleased to acknowledge grant support from the National Monuments Service, Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage and the Royal Irish Academy for the Eagle’s Nest post-excavation project. Our thanks to colleagues providing their expertise to the paper; Conor McHale, Niamh Kelly, Lily Olet, Stephen Mandal, Karen O’Toole, Hélène Pioffet, Alison Sheridan, Jessica Smyth, Patrick Quinn and Graeme Warren. The paper benefited from the detailed comments of three referees and we are grateful to the editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gabriel Cooney

Gabriel Cooney is emeritus professor of Celtic Archaeology, School of Archaeology, University College Dublin. His research interests focus on the Neolithic period, particularly the use of stone, stone axehead quarries and on mortuary practices in prehistory and he has authored, co-authored and co-edited a number of books, and published widely in academic journals and book chapters.

Brendan O’Neill

Brendan O’Neill is a lecturer in the School of Archaeology at University College Dublin and co-Director of the Centre for ExperimentalArchaeology and Material Culture. His research interests focus on material culture and the production/use of objects in the past as well as the relationship between people, objects and place.

Martha Revell

Martha Revell is a Research Assistant on the Lambay Project, based in University College Dublin and is also an independent stone tools specialist writing technical reports of recently excavated material. Her research interests include stone tool technologies and her MSc thesis examined Mesolithic bone artefacts from Ireland.

Bernard Gilhooly

Bernard Gilhooly is an Assistant Keeper, Irish Antiquities Division, National Museum of Ireland. His PhD examined the manufacture and range of uses of Irish porcellanite and shale axes/adzes from the Mesolithic to the Early Bronze age. His main research interests are in the Mesolithic period, the Mesolithic/Neolithic transition as well as the uses of experimental archaeology within archaeological research.

Rachael Knutson

Rachael Knutson completed an MSc thesis in ExperimentalArchaeology and Material Culture in the School of Archaeology, University College Dublin. Her MSc thesis examined grindstone use-wear in the production of porphyritic andesite stone axeheads.

References

- Alberti, B. 2016. “Archaeologies of Ontology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45 (1): 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095858.

- Ballin, T. B. 2013. “Felsite Axehead Reduction—The Flow from Quarry Pit to Discard/Deposition.” In Farming on the Edge: Cultural Landscapes of the North, edited by D. Mahler, 73–91. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Boivin, N. 2004. “From Veneration to Exploitation: Human Engagement with the Mineral World.” In Soils, Stone and Symbols: Cultural Perceptions of the Mineral World, edited by N. Boivin and A.M. Owoc, 1–29. London: UCL Press.

- Boríc, D., O. J. T. Harris, P. Miracle, and J. Robb. 2013. “The Limits of the Body.” In The Body in History: Europe from the Palaeolithic to the Future, edited by J. Robb and O.J. T. Harris, 32–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bradley, R. 2019. The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bradley, R., and M. Edmonds. 1998. Interpreting the Axe Trade: Production and Exchange in Neolithic Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cassidy, L. M. 2023. “Islands Apart? Genomic Perspectives on the Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in Ireland.” In Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent, edited by A. Whittle, J. Pollard, and S. Greaney, 147–167. Neolithic Studies Group Papers 19. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Conneller, C. 2011. An Archaeology of Materials: Substantial Transformations in Early Prehistoric Europe. London: Routledge.

- Cooney, G. 1998. “Breaking Stones, Making Places.” In Prehistoric Ritual and Religion, edited by A. Gibson and D.D.A. Simpson, 108–118. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Cooney, G. 2000. Landscapes of Neolithic Ireland. London: Routledge.

- Cooney, G. 2002. “So Many Shades of Rock: Colour Symbolism in Irish Stone Axeheads.” In Colouring the Past, edited by A. Jones, and G. MacGregor, 93–107. Oxford: Berg.

- Cooney, G. 2005. “Stereo Porphyry: Quarrying and Deposition on Lambay Island, Ireland.” In The Cultural Landscape of Prehistoric Mines, edited by P. Topping and M. Lynott, 14–29. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Cooney, G. 2008. “Engaging with Stone: Making the Neolithic in Ireland and Britain.” Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 40:203–214.

- Cooney, G. 2015. “Stone and Flint Axes in Europe.” In The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe, edited by C. Fowler, J. Harding and D. Hofmann, 515–534. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cooney, G. 2017. “The Role of Stone in Island Societies in Neolithic Atlantic Europe: Creating Places and Cultural Landscapes.” Arctic 69 (Suppl 1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4666.

- Cooney, G., and S. Mandal. 1998. The Irish Stone Axe Project. Monograph 1. Bray: Wordwell.

- Cooney, G., A. Bayliss, F. Healy, A. Whittle, E. Danaher, L. Cagney, J. Mallory, J. Smyth, T. Kador, and M. O’Sullivan. 2011. “Chapter 12, Ireland.” In Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland, edited by A. Whittle, A. Bayliss, and F. Healy, 562–669. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Cooney, G., S. Mandal, E. O’Keeffe, and G. Warren. 2012. “Porcellanite Axe Production on Rathlin Island.” In Rathlin Island an Archaeological Survey of a Maritime Landscape, edited by W. Forsythe and R. McConkey, 62–74. Norwich: The Stationery Office/Northern Ireland Environment Agency.

- Cooney, G., W. Megarry, M. Markham, B. Gilhooly, B. O’Neill, J. Gaffrey, R. Sands, et al. 2019. “Tangled Up in Blue: The Role of Riebeckite Felsite in Neolithic Shetland.” In Mining and Quarrying in Neolithic Europe: A Social Perspective, edited by A. Teather, P. Topping, and J. Baczkowski, 49–65. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 16. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Cummings, V., and C. Richards. 2021. Monuments in the Making: Raising the Great Dolmens in Early Neolithic Northern Europe. Oxford: Windgather Press.

- Dickson, F. P. 1981. Australian Stone Hatchets: A Study in Design and Dynamics. London: Academic Press.

- Dolan, B., and G. Cooney. 2010. “Lambay Lithics: The Analysis of Two Surface Collections from Lambay, Co. Dublin.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 110:1–33.

- Edinborough, K., S. Shennan, A. Teather, J. Baczkowski, A. Bevan, R. Bradley, G. Cook, et al. 2020. “New Radiocarbon Dates Show Early Neolithic Date of Flint-Mining and Stone Quarrying in Britain.” Radiocarbon 62 (1): 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2019.85.

- Edmonds, M. 1995. Stone Tools and Society. London: Batsford.

- Edmonds, M. 2012. “Axes and Mountains: A View from the West.” In JADE: Grande haches alpines du Néolithique européen, Ve au IVe millénaires av. J-C, edited by P. Pétrequin, S. Cassen, M. Errera, L. Klassen, A. Sheridan, and A-M. Pétrequin, 1194–1207. Besancon: Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté et Centre de Recherche Archéologique de la Vallée de l’Ain.

- Elliott, B.2019. “Craft Theory in Prehistory: Case Studies from the Mesolithic of Britain and Ireland.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 85:161–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2019.9.

- Elliott, B., A. Little, G. Warren, A. Lucquin, E. Blinkhorn, and O. E. Craig. 2020. “No Pottery at the Western Periphery of Europe: Why Was the Final Mesolithic of Britain and Ireland Aceramic?” Antiquity 94 (377): 1152–1167. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.174.

- Ericson, J. E. 1984. “Towards the Analysis of Lithic Production Systems.” In Prehistoric Quarries and Lithic Production, edited by J.E. Ericson and B.A. Purdy, 1–9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fahlander, F. 2017. “Ontology Matters in Archaeology and Anthropology.” In These “Thin Partitions”: Bridging the Growing Divide Between Cultural Anthropology and Archaeology, edited by J.D. Englehardt and I.A. Rieger, 69–86. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

- Gaydarska, B., and J. Chapman. 2008. “The Aesthetics of Colour and Brilliance- or Why Were Prehistoric Persons Interested in Rocks, Minerals, Clays and Pigments?” In Geoarchaeology and Archaeomineralogy, edited by R. Kostov, B. Gaydarska, and M. Gurova, 63–66. Sofia: St Ivan Rilski.

- Gilhooly, B. 2018. “An Axe for All Seasons: An Investigation into Mechanical Properties and Uses of Irish Shale and Porcellanite Axes from the Mesolithic to the Bronze Age. Experimental, Quantitative and Comparative Studies.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University College Dublin.

- Herva, V.-P., K. Nordqvist, A. Lahelma, and L. Ikaheimo. 2014. “Cultivation of Perception and the Emergence of the Neolithic World.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 47 (2): 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2014.950600.

- Hoare, P. G. 1975. “The Pattern of Glaciation of County Dublin.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 75 (B): 207–224.

- Jones, A. 2004. “Archaeometry and Materiality: Materials-Based Analysis in Theory and Practice.” Archaeometry 46 (3): 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00161.x.

- Kador, T. 2007. “Stone Age Motion Pictures: an objects’ perspective from early prehistoric Ireland.” In Prehistoric Journeys, edited by V. Cummings and R. Johnston, 33–44. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Kador, T. 2009. “Prehistoric Chain Reactions- Stories That Help Us Understand the Distant Past.” In From Bann Flakes to Bushmills: Papers in Honour of Professor Peter Woodman, edited by N. Finlay, S. McCartan, N. Milner, and C. Wickham-Jones, 31–41. Prehistoric Society Research Paper 1. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Kelly, N. 2021. Eagles’s Nest, Lambay (93E144): Coarse Stone Tool Report. Unpublished.

- Knutson, R. 2023. “On the Grind: A Study of Neolithic Grindstones from Lambay Island.” Unpublished MSc thesis, University College Dublin.

- Leon, B. C. 2005. “Mesolithic and Neolithic Activity on Dalkey Island – a Reassessment.” Journal of Irish Archaeology 14:1–21.

- Little, A. 2009. “The Island and the Hill. Extracting Scales of Sociability from a Mesolithic Chert Quarry.” In From Bann Flakes to Bushmills: Papers in Honour of Professor Peter Woodman, edited by N. Finlay, S. McCartan, N. Milner, and C. Wickham-Jones, 133–142. Prehistoric Society Research Paper 1. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Little, A., A. van Gijn, T. Collins, G. Cooney, B. Elliott, B. Gilhooly, S. Charlton, and G. Warren. 2017. “Stone Dead: Uncovering Early Mesolithic Mortuary Rites, Hermitage, Ireland.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27 (2): 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000536.

- Mallory, J. 1990. “Trial Excavations at Tievebulliagh, Co. Antrim.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 52:15–28.

- Mandal, S. 1996. The petrology of the Irish stone axe. Unpublished PhD thesis, Trinity College Dublin.

- Mandal, S., G. Cooney, I. Meighan, and D. Jamison. 1997. “Using Geochemistry to Interpret Porcellanite Stone Axe Production in Ireland.” Journal of Archaeological Science 24 (8): 757–763. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1996.0157.

- McCabe, M. 2008. Glacial Geology and Geomorphology: The Landscapes of Ireland. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

- Megarry, W. P., M. Markham, B. Gilhooly, B. O’Neill, and G. Cooney. 2021. “Insular Networks: An Exploration of Material Distribution, Insularity and Island Identity on the Edge of Europe in the Shetland Neolithic.” The Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology 18 (4): 612–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2021.1880506.

- Miles, D. 2016. The Tale of the Axe: How the Neolithic Revolution Transformed Britain. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Murphy, S. 1997. Stone Mad. Belfast: Blackstaff Press.

- Nyland, A. J. 2016. Variations in rock procurement practices in the Stone, Bronze and Early Iron Ages, in southern Norway. Published PhD thesis, University of Oslo.

- Nyland, A. J. 2019. “Being ‘Mesolithic’ in the Neolithic: Practices, Places and Rock in Contrasting Regions in South Norway.” In Mining and Quarrying in Neolithic Europe: A Social Perspective, edited by A. Teather, P. Topping, and J. Baczkowski, 67–81. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 16. Oxford: Oxbow.

- O’Toole, K. 2018. The world in miniature: Understanding the production of Neolithic miniature stone axes from Lambay Island using experimental archaeology. Unpublished MSc thesis, University College Dublin.

- Olet, L., R. P. Evershed, and J. Smyth. 2022. Organic Residue Analysis of Early and Middle Neolithic Pottery from Lambay Island. Unpublished report.

- Olsen, B. 2013. In Defense of Things: Archaeology and the Ontology of Objects. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira.

- Pétrequin, P. S. Cassen, M. Errera, L. Klassen, A. Sheridan, and A.-M. Pétrequin. 2012. Jade. Grandes haches alpines due Néolithique européen V et IV millénaires av. J. C. Besancon: Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté.

- Pioffet, H. 2014. Sociétés et Identités du Premier Néolithique de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande dans leur context oueste européen: caractérisation et analyses comparatives des productions céramiques entre Marche, Mer d’Irlande et Mer du Nord. Unpublished PhD thesis, Université de Rennes 1 and Durham University.

- Quinn, P. S. 2022. Petrographic Analysis of Neolithic Sherds from Lambay Island, Ireland. Unpublished report.

- Schauer, P., S. Shennan, A. Bevan, S. Colledge, K. Edinborough, T. Kerig, and M. Parker Pearson. 2021. “Cycles in Stone Mining and Copper Circulation in Europe 5500-2000 BC: A View from Space.” European Journal of Archaeology 24 (2): 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2020.56.

- Sheridan, J. A. 1986. “Porcellanite Artifacts: A New Survey.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 49:19–32.

- Sheridan, J. A. 2007. “From Picardie to Pickering and Pencraig Hill? New Information on the ‘Carinated Bowl Neolithic’ in Northern Britain.” In Going Over: The Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in North-West Europe, edited by A. Whittle and V. Cummings, 441–492. London: British Academy.

- Sheridan, J. A. 2022. Report on the Pottery Found at Eagle’s Nest, Lambay Island. Unpublished report.

- Sheridan, J. A., and Y. Pailler. 2012. “Les haches alpines et leurs imitations en Grande-Bretagne, dans l’ile de Man, en Irelande et dans les iles Anglo_Normandes.” In JADE: Grande haches alpines du Néolithique européen, Ve au IVe millénaires av. J-C, edited by P. Pétrequin, S. Cassen, M. Errera, L. Klassen, A. Sheridan, and A-M. Pétrequin, 1046–1087. Besancon: Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté et Centre de Recherche Archéologique de la Vallée de l’Ain.

- Smyth, J. 2014. “Settlement in the Irish Neolithic: New Discoveries at the Edge of Europe.” Prehistoric Society Research Paper, Vol. 6. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Smyth, J., and R. P. Evershed. 2015. “The Molecules of Meals: New Insight into Neolithic Foodways.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 115C (1): 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1353/ria.2015.0011.

- Smyth, J., M. McClatchie, and G. M. Warren. 2020. “Exploring the ‘Somewhere’ and ‘Someone’ Else: An Integrated Approach to Ireland’s Earliest Farming Practice.” In Farmers at the Frontier: A Pan-European Perspective on Neolithisation, edited by K.J. Gron, L. Sorensen, and P. Rowley-Conwy, 425–41. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Stillman, C. 1994. “Lambay, an Ancient Volcanic Island in Ireland.” Geology Today, March-April 1994, 10 (2): 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2451.1994.tb00869.x.

- Stroulia, A. 2003. “Ground Stone Celts from Franchthi Cave: A Close Look.” Hesperia 72 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2972/hesp.2003.72.1.1.

- Topping, P. 2017. “Neolithic Stone Extraction in Britain and Europe: An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective.” Prehistoric Society Research Paper, Vol. 12. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Tsoraki, C. 2011. “Stone-Working Traditions in the Prehistoric Aegean: The Production and Consumption of Edge Tools at Late Neolithic Makriyalos.” In Stone Axe Studies III, edited by V. Davis and M. Edmonds, 231–244. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Warren, G. 2022. Hunter-Gatherer Ireland: Making Connections in an Island World. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Whittle, A., A. Bayliss, and F. Healy. 2011. “Gathering Time: The Social Dynamics of Changes.” In Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland, edited by, edited by A. Whittle, A. Bayliss, F. Healy, A. Whittle, A. Bayliss, and F. Healy, 848–914. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Woodman, P. C. 2015. Ireland’s First Settlers: Time and the Mesolithic. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Yerkes, R. W., R. Barkai, A. Gopher, and O. Bar-Yosef. 2003. “Microwear Analysis of Early Neolithic (PPNA) Axes and Bifacial Tools from Netiv Hagdud in the Jordan Valley, Israel.” Journal of Archaeological Science 30 (8): 1051–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00007-4.