ABSTRACT

As universities evolve through mission expansion and grapple with the increasing need to bridge academic work with practical relevance, researchers are finding themselves in the complex terrain of simultaneously embracing their entrepreneurial and academic identities. This study investigates the factors enabling hybrid identity centrality—a conscious recognition of being both an academic and entrepreneurial individual—among university researchers. Drawing on a sample of 312 researchers from two multifaculty universities, the findings show that researchers’ perception of a university’s entrepreneurship strategy implementation and their society—industry orientation significantly influence the likelihood of hybrid identity centrality. Notably, the society-industry orientation moderates the relationship between entrepreneurship strategy implementation and the adoption of a hybrid identity. The study contributes to the research on the complementarity of academic and entrepreneurial identities and adds novel insights to the organizational research on academic entrepreneurship by suggesting that entrepreneurship strategy alone may not suffice in promoting hybrid identity.

© 2024 The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Introduction

Universities face external pressures for strategic change because they are seen as important providers of societal and economic impact in their interactions with industry, governments, and wider society (Etzkowitz, Citation2008; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015). For example, several institutional reforms to increase the footprint of academia and researchers’ work have been introduced, such as the Bayh-Dole Act to accelerate inventions from public research (for example, Grimaldi et al., Citation2011) and the introduction of impact case studies in the UK’s research excellence framework (Terämä et al., Citation2016). In addition to knowledge creation and transmission, universities are seen as hubs for academics to engage in socially or environmentally relevant research projects, to commercialize new knowledge, to start new ventures, or to valorize research results in other novel ways (Etzkowitz, Citation2008). University funding, which is a key resource for research, teaching, and outreach, is increasingly related to performance-based outcomes or subject to competitive public grant schemes (O’Kane et al., Citation2022), with societal impact as a key indicator.

In response to these pressures, universities have aimed to become entrepreneurial and strengthen their impact by expanding their mission focus (Etzkowitz, Citation2008; Gibb, Citation2012) and fostering internal strategic changes (Klofsten et al., Citation2019). Entrepreneurial universities serve society and contribute to economic development by being sources of entrepreneurship and key drivers of knowledge-based economies (Etzkowitz, Citation2008; Klofsten et al., Citation2019). They develop new business models to diversify revenue streams and intensify partnerships with the industry (Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2018). The entrepreneurial universities formulate new development strategies and create new organizational structures to support academic entrepreneurship and motivate researchers to become entrepreneurial academics or academic entrepreneurs (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2018; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015). Such entrepreneurial transition and new strategic structures, especially in traditional research universities, are likely to challenge typical academic work routines and confront academic researchers with potentially contradicting beliefs and values (Hardy & Maguire, Citation2008; Hayter et al., Citation2021).

Academic researchers appear to prioritize and enact an academic identity (Jain et al., Citation2009) that is deeply rooted in the traditional university system (Feldmann, Citation2014). However, the new norms and expectations for universities suggest that academics should also enact other identities (Jain et al., Citation2009; O’Kane et al., Citation2020), in particular, they are expected to become more entrepreneurial. As academic researchers play a crucial role in the successful implementation of entrepreneurial initiatives (Etzkowitz, Citation1998; Gibb, Citation2012), individual-level identity tensions can hinder the evolution of entrepreneurial universities. Therefore, discovering ways to help individual researchers deal with these tensions and offering insights on how universities can support researchers in this direction is important.

So far, the literature has mostly treated these two identities, “academic identity” and “entrepreneurial identity,” separately, and individual-level studies have focused on identity change, that is, the shift from an academic identity to an entrepreneurial one (for example, Hayter et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2009). However, for those academics who wish to stay within academia, a potential avenue to resolve the tensions is to put emphasis on societally relevant research and collaboration with the industry and cultivate a strong entrepreneurial and academic identity that would enable recognition of external engagement while maintaining a commitment to core scientific values (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Lam, Citation2010; Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996; Pilegaard et al., Citation2010). Arguably, hybrid identity, the fusion of academic identity and entrepreneurial identity (Jain et al., Citation2009; Lam, Citation2010), and its centrality (proximity to the individual’s core self) (Stryker & Serpe, Citation1994) may be the optimal state that a societally impactful university hopes to stimulate among its researchers (Jain et al., Citation2009; Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021).

Academic entrepreneurship scholars have investigated the university transition from the organizational perspective, producing insights into the functions and activities of entrepreneurial universities (Etzkowitz, Citation1998; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015). However, this research stream has largely overlooked the perspective of an individual academic (Balven et al., Citation2018; Henkel, Citation2005; O’Kane et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). Therefore, there is a gap in scholars’ understanding of the organizational factors that enable hybrid identity centrality (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002). Universities have created entrepreneurial strategies that communicate the importance of entrepreneurship in the university and implemented the strategy by developing relevant training and support structures for academics. However, it remains unknown whether these entrepreneurship strategies and their implementation within universities help university researchers perceive both academic and entrepreneurial identities as simultaneously important.

This omission is significant given the increasing investments in entrepreneurial university development and the growing demand for entrepreneurial identities among academics in the ongoing transition (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Jain et al., Citation2009; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). Focusing on hybrid identity centrality is important, given the known influence of identity on entrepreneurial behavior within the university and other organizational contexts (O’Kane et al., Citation2020; Stryker & Serpe, Citation1994; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). To address this gap, our study asks the following question: What are the enablers of hybrid identity centrality in the entrepreneurial university context?

To investigate the hybrid identity centrality of academics, we have analyzed a sample of 312 university researchers from two multifaculty research-focused universities in Finland that recently established strategies to become entrepreneurial universities. In doing so, the present study combines the perception of new entrepreneurship strategy and its’ implementation with the society-industry orientation of academic researchers. Thus, the study highlights both organizational and individual enablers of hybrid identity (Feldmann, Citation2014). Our findings demonstrate that an interplay between organizational and individual enablers increases the likelihood of hybrid identity centrality. Such centrality can be supported by top-down managerial initiatives that create structures and means for enabling academics within the university to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Feola et al., Citation2019), while the individual factors stem from the academics themselves (for example, their beliefs and values) (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Lam, Citation2010).

As a result, our study contributes to the academic entrepreneurship literature by integrating the individual researcher’s identity centrality perspective with entrepreneurial university development. Our study contributes to the research on the complementarity of academic and entrepreneurial identities (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2018) by underscoring that the perceived organizational and individual factors collaboratively influence identity-related outcomes (for example Wang, Cai, et al., Citation2021; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2020). Importantly, the present study adds novel insights to the organizational research on academic entrepreneurship by suggesting that entrepreneurship strategy alone may not suffice in promoting hybrid identity centrality (Balven et al., Citation2018; Sandström et al., Citation2016). The study also offers practical implications for university management, administrators and faculty members who are interested in the possibility of developing as academic entrepreneurs.

Theoretical framework

Identities in the context of a university in transition

Drawing from both role identity (Stryker & Burke, Citation2000) and social identity theory (Stets & Burke, Citation2000), we define an individual’s identity as a unique set of self-referential meanings within a social role or as a member of a social group that defines who one is (Alsos et al., Citation2016; Wells, Citation1978). Researchers tend to prioritize and enact an academic identity (Jain et al., Citation2009), which is formed and maintained through individual and collective values, beliefs, and behaviors (Henkel, Citation2005). It comprises the roles of academic discipline and academic freedom, which are adopted by members of the academic community (Henkel, Citation2005). Commitment to scholarship, intellectual curiosity, peer accountability, and professional autonomy are crucial to academic identity (Ramsden, Citation1998; Winter, Citation2009). An entrepreneurial academic perceives entrepreneurial role as meaningful and self-defining, and identifies as part of a community of entrepreneurial people (Radu-Lefebvre et al., Citation2021). Within a university context, being entrepreneurial can entail a broad range of activities ranging from engaging in research commercialization to becoming or acting as an entrepreneur or participating in activities that amplify the value of research, such as university-industry partnerships and contract research (Abreu & Grinevich, Citation2013; Nabi et al., Citation2010; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021).

Organizational changes impact the identities of individual employees (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Dutton et al., Citation1994). In a traditional research-oriented university, transitioning toward entrepreneurial structures and policies is a fundamental organizational change that comprises entrepreneurship strategy development and its implementation. The entrepreneurship strategy can be defined as an intentional and coordinated plan of actions that outlines how an institution intends to foster and support entrepreneurial activities within its academic and operational frameworks (Etzkowitz, Citation2013; Gibb, Citation2012). However, academic researchers, who are focused on pure research and pursuing knowledge, may experience internal conflict with the new values emphasizing societal impact and entrepreneurship (Jain et al., Citation2009; Mäkinen & Esko, Citation2023; Meek & Wood, Citation2016; Zou et al., Citation2019). The organizational changes in general can make employees feel threatened and trigger inner resistance to protect themselves (Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). In a university, this conflict manifests as individual-level identity tensions between the academic and (potential) entrepreneurial self of researchers (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). Some researchers would disregard the need for external engagement, research valorization, outreach, or other entrepreneurship-related activities in response to the changes (Hayter et al., Citation2021). If left unresolved, such tensions may result in suppressing one’s entrepreneurial identity, heightened fear of ongoing organizational changes, and risk avoidance expressed as a “closing off” in one’s academic identity.

In order to resolve potential tensions, the individual may seek to align their identity with the new organizational identity (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009) by reevaluating the importance of more distant identities and reconstructing the identity structure (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989; Burke, Citation2006; Jain et al., Citation2009). When recognizing a tension between the identities, an academic researcher can adopt a hybrid identity where both academic and entrepreneurial identities are strong (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Jain et al., Citation2009; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). Adopting a hybrid identity relies on the idea that individuals carry multiple identities that interact (Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002; Stryker & Burke, Citation2000).

In contrast, organizational changes can reveal the organization’s strive toward societal impact and strengthen employees’ sense of belonging (Dutton et al., Citation1994). The new strategy broadens the array of possible identities (O’Kane et al., Citation2020), including an entrepreneurial identity. Hence, this new organizational strategy may empower entrepreneurial academics to value and claim their hybrid identity centrality (Jain et al., Citation2009; O’Kane et al., Citation2022; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002).

In summary, we argue that academic and entrepreneurial identities are the most important overarching identities in the current university landscape. However, the expectations of becoming entrepreneurial may create identity tensions among academics. Adopting a hybrid (academic and entrepreneurial identity tandem) is an optimal approach to resolving potential identity tensions and aligning with the new organizational norms and expectations that universities encounter (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2009; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). In turn, universities can assist academic researchers in overcoming this new identity challenge by communicating a clear organizational strategy that values and rewards entrepreneurship and by implementing this strategy through expanded training and support for developing entrepreneurship curriculum, research commercialization, and creating spin-offs (Gibb, Citation2012; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Schulte, Citation2004). However, the effectiveness of these strategy elements in resolving identity tensions and enabling the enactment of hybrid identities remain unknown.

Hypothesis development

Organizational strategy expresses the values and rewards within an organization, influencing how knowledge, skills, routines, and expertise are utilized (Green, Citation1988; Stead & Stead, Citation2000) and how organizations adapt to environmental change (Oliver, Citation1991). However, strategic shifts can impact employees’ affiliation with the organization and their self-identities (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Price & Whiteley, Citation2014; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). This helps them in realizing their sense of belonging to the organization and the interplay between themselves, their work, and the organization they work for (Alvesson et al., Citation2008; Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989). Prior research has suggested that successful entrepreneurial universities, such as Stanford and Cambridge, have clear entrepreneurship strategies that foster a shared vision that harmonizes both traditional academic and entrepreneurial values (Etzkowitz, Citation2008, Citation2013; Gibb, Citation2012; Klofsten et al., Citation2019).Footnote1

The entrepreneurship strategy indicates that entrepreneurship is valued, which includes creating awareness and appreciation of an entrepreneurial culture within a university, as well as introducing reward systems that stimulate entrepreneurial activity of researchers (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Eriksson et al., Citation2021; Gibb, Citation2012; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019). Hence, if there is an entrepreneurship strategy that an academic researcher is aware of and perceives as important, this can help them make sense of and see the benefits of being more entrepreneurial in their work (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Balven et al., Citation2018; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; O’Kane et al., Citation2022). Because the academic researchers’ identity represents their organizationally situated self-definitions (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989), a clear institutional strategy might help researchers claim their hybrid identity centrality (Jain et al., Citation2009; O’Kane et al., Citation2022; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002). The clear organizational strategy that indicates entrepreneurship is valued and rewarded will help researchers become more attuned with the importance of entrepreneurial activities and to realign their professional role identities with the new organizational values. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

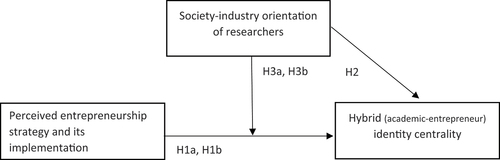

H1a:

The perceived entrepreneurship strategy is positively associated with strong hybrid identity centrality.

In addition to having a strategy, its implementation is crucial in aligning the strategy with the strategic intentions of an organization and in providing behavioral direction to employees (Boal & Hooijberg, Citation2001; Lee & Puranam, Citation2016). Through the implementation of a strategy employees derive a sense of value and purpose of their work (Barrick et al., Citation2015), and as a result, the implementation, such as through training and professional development initiatives, supports employees in understanding the nature of their work that can, in turn, shape and reinforce their professional identities (Brousseau et al., Citation1996; Hayter et al., Citation2021).

The university implements their entrepreneurship strategy by providing resources; expanding the entrepreneurship training and support provision for developing entrepreneurship activities, curriculum, research commercialization and spin-off creation (Gibb, Citation2012; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Schulte, Citation2004). This may help researchers overcome the fears associated with the entrepreneurial transition and deal with cognitive contradictions related to academic and entrepreneurial roles. Such an understanding may also enable the enactment of their hybrid identities. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H1b:

The perceived entrepreneurship strategy implementation is positively associated with strong hybrid identity centrality.

On a continuum from a traditional scientist to an entrepreneur, a hybrid identity is emerging as a distinct category of academics. This shift is due to the blurring boundaries between academic scholarship and entrepreneurship practice (Guo et al., Citation2019; Lam, Citation2010). Besides the perception of new organizational strategies that can enable academics to balance the two polarized identities, individual beliefs, values, goals, and orientations can either support or hinder the adoption of this hybrid role (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Jain et al., Citation2009; Lam, Citation2010). According to Ashforth et al. (Citation2008), the better these content attributes of organizationally based identities align with the individual’s core self, the stronger the hybrid identity centrality. Academics who choose to conduct societally relevant research or collaborate with industry may face external pressures. These exist regardless of the strategic actions of the university, and academics are likely to resolve identity tensions individually by adopting the hybrid identity (Lam, Citation2010; Wagenschwanz, Citation2021).

Academics might be interested in the benefits of research commercialization and to exploit market opportunities through joint ventures, licensing, or spin-offs, for example (Jain et al., Citation2009). Alternatively, they may adopt an entrepreneurial perspective and engage in wider forms of knowledge transfer, which involves collaboration with industry and societal stakeholders through collaborative research and executive education (Miller et al., Citation2018). The idea of contributing to society, especially in publicly funded universities, can rationalize engagement with society or industry, particularly for traditional scientists. This rationalization can enable the adoption of a hybrid identity (Lam, Citation2010). Collaboration with industry and society are even more fruitful when they contribute to both industrial applications and academic research, often going beyond monetary incentives (Este & Perkmann, Citation2011).

In conclusion, in the context of the ongoing entrepreneurial evolution, an academic who chooses to conduct societally relevant research and/or collaborate with industry can help address externally caused pressures irrespective of the university’s strategic actions. Hence, we hypothesize that academic researchers who are consciously oriented toward these collaborations are more likely to have a strong hybrid identity centrality:

H2:

The society-industry orientation is positively associated with strong hybrid identity centrality.

Drawing upon the organizational research, the university strategy shapes how employees identify with their organizations (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989; He & Brown, Citation2013). When a strategy focusing on entrepreneurship guides academic researchers, they are simultaneously granted the autonomy to choose ways to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Este & Perkmann, Citation2011), it can stimulate a renegotiation of their identity (Jain et al., Citation2009). Researchers would not compromise their academic freedom. Instead, they pursue a balance between free science and societal engagement. For example, they may engage in societally relevant projects that align with their research activities (Este & Perkmann, Citation2011; Jain et al., Citation2009). The personal beliefs of researchers about the importance of collaboration with industry and society can interact with their perception of strategic initiatives. This interaction can mutually support the hybrid identity (Wang, Cai, et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2020).

In addition, entrepreneurship strategy of a university in the ongoing entrepreneurial evolution can help academics in managing with external pressures by adopting a hybrid identity (for example, Jain et al., Citation2009; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). When academics choose to conduct societally relevant research or collaborate with industry in research, it can strengthen the impact of the perceived strategy. Therefore, we propose that an individual’s willingness to conduct societally relevant research and collaborate with industry is likely to interact positively with the perceived entrepreneurship strategy in fostering hybrid identity centrality.

H3a:

The society-industry orientation positively moderates the relationship between the perceived entrepreneurship strategy and strong hybrid identity centrality.

An individual’s interest in societal impact and industry orientation can lead researchers to align more strongly with the entrepreneurial support structures of the university, and foster an appreciation for the creation of entrepreneurial culture within the university (Este & Perkmann, Citation2011; Grimaldi et al., Citation2011; Perkmann et al., Citation2013). When a strategy is implemented, it provides clarity over the organization’s strategic direction and guides employees’ behavior and their sense of belonging (Barrick et al., Citation2015; Boal & Hooijberg, Citation2001; Lee & Puranam, Citation2016). If these aspects align with individuals’ engagement with industry and society, they might support the values and beliefs of academics (Lam, Citation2011) and allow them to maintain academic and other identities (Lam, Citation2010). Hence, the university’s implementation of entrepreneurship strategy, provision of entrepreneurship training, and establishing entrepreneurship support structures, coupled with individual efforts, creates a more conducive environment for the development of hybrid identity (for example, Gibb, Citation2012; Jain et al., Citation2009). Consequently, academic researchers who are oriented toward conducting research that addresses societal needs might find it easier to align with the institutional support for entrepreneurship, recognizing the potential for synergy. Therefore, we hypothesize that an individual’s willingness to conduct societally relevant research and collaborate with industry is likely to interact positively with the implementation of entrepreneurship strategy, that is, availability of entrepreneurship training and support structures, and thereby foster the hybrid identity centrality:

H3b:

The society-industry orientation positively moderates the relationship between the perceived entrepreneurship strategy implementation and strong hybrid identity centrality.

summarizes the outline of the study framework and hypotheses.

Methodology

Research setting

The present study was conducted in two multidisciplinary research-oriented Finnish universities—University A and University B—both of which had similar profiles regarding having several faculties (such as humanities, natural sciences, social sciences, economics, and business in each), having a global drive to develop as entrepreneurial and/or as impactful universities, and employing an average of active 1500–1800 staff and faculty members (). Before data collection, both universities adopted and started implementing the new entrepreneurship strategies (aiming to become “entrepreneurial universities”). Both universities implemented a broad perspective into the entrepreneurial university development, aiming for social and economic impact beyond merely focusing on academic spin-offs, for example. Thus, the selected universities are distinct from other universities in FinlandFootnote2 (in line with the purposive sampling employed, for example, Etikan et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. University profiles.

University A had three campuses, 13 fields of study, and more than 100 major subjects in four faculties: the Philosophical Faculty, the Faculty of Science and Forestry, the Faculty of Health Sciences, and the Faculty of Social Sciences and Business Studies. In 2015, University A launched a new strategy for 2015–2020, in which its interdisciplinary research areas were built around four global challenges: aging, lifestyles, and health; learning in a digital society; cultural encounters, mobilities, and borders; and environmental change and sufficiency of natural resources.

University B had three campuses and seven faculties (medicine, natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, education, economics, and law). In 2015, it launched a new entrepreneurship strategy for 2016–2020 and stated the ambition of becoming an “entrepreneurial university.” The university dedicated some resources and hired entrepreneurship managers who had the responsibility of developing and implementing activities on various fronts (entrepreneurship education for both students and staff, new business development and cooperation with business, commercialization of research and innovations).

Data collection and sample

Data were collected using an online survey at both universities around the same time in 2017 and 2018, when the implementation of their strategies was at full speed.

Guided by prior research on entrepreneurial universities and academic entrepreneurship (for example, Etzkowitz, Citation2008; Gibb, Citation2012; Lam, Citation2010, Citation2011) as well as on entrepreneurial identity (for example, Murnieks et al., Citation2014), two researchers developed the survey questionnaire. All key constructs were measured using multiple items. The measurements relied both on existing scales (for example, entrepreneurial identity centrality) and those created for the purposes of the study (entrepreneurship strategy perception and society-industry orientation). The questionnaire content was further discussed in a focus group of six entrepreneurship and management scholars who reviewed the content and order of the questions, specifically revising the scale items (Haynes et al., Citation1995). Before launching the survey, we piloted the questionnaire among 23 researchers to check whether the wording of the questions was clear and understandable (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). After the pilot, some questionnaire items were revised to increase clarity and better align the Finnish and English language versions of the survey.

In conducting the study, the research team followed the guidelines on research ethics set out by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and there was no possibility of identifying respondents from the findings. The survey respondents were informed what the study was about (“This survey explores opinions of university faculty and staff related to entrepreneurship and research process”) and of the study funder (Research Council of Finland). The respondents did not receive any incentives for participating and could discontinue their participation at any time; the survey did not employ the “Force response” function.

The sample comprised 312 researchers working at University A (n1 = 199) and University B (n2 = 113) (see ). The sample included junior and senior researchers from different disciplines (humanities, technology, business, and so on). Of the respondents, 18 percent were professors or research directors; 19 percent were assistant professors, senior research fellows, or university lecturers; 24 percent were postdoctoral researchers, research fellows, or university teachers; and 39 percent were PhD students, project researchers, or the like. The share of men and women in the sample was almost equal, and the age distribution was relatively balanced among the respondents. The average age of the respondents was 43 years, and on average, they had worked 13 years in academia. Twenty-seven percent of the respondents had prior experience as business owners or founders.

Table 2. Sample composition by disciplinary areas and university (frequencies).

The response rate from the first university was 11 percent (out of 3200 invitees to the survey, 365 responded). The response rate from the second university was 9 percent (out of 2612 invitees, 243 responded). This response activity is similar to other studies conducted among academics, for example, in Wang, Soetanto, et al. (Citation2021) and Wang, Cai, et al. (Citation2021).

The universities’ communication offices sent out the invites to the “all staff” lists, which included all active employees (in the case of University A, some retired individuals did not respond to the survey request). The original sample covered a variety of university staff, including administration, services, and management, along with the staff involved only in teaching or only in management. In light of the present study’s focus on academic researchers, the sample was first reduced to n = 390. Following the exclusion of missing observations in several variables, the resulting sample comprised 312 respondents.

To test the potential nonresponse bias, we analyzed the differences between respondents who completed the questionnaire and those who started but did not complete it or provided invalid responses (n = 922). The results of the means difference tests (T test) show no statistically significant differences related to age, field of study/major, or between the universities. Moreover, no significant differences concerning gender, age, entrepreneurship experience, and academic research experience were found between the two university samples. Accordingly, these results imply that nonresponse bias or potential sample biases across the studied universities did not influence the results.

Variables and measurement

The dependent variable, hybrid identity centrality, is based on measures of entrepreneurial and academic identity centrality. Both measures relied on Sellers et al. (Citation1997) identity centrality scales modified to apply to the entrepreneurship context,Footnote3 which is similar to Wang, Soetanto, et al. (Citation2021) approach. Sellers et al. (Citation1997, p. 815) original scale addressed the centrality of racial identity, but the scale was adjusted to account for the respondents’ entrepreneurial or academic identities. The phrase “being Black” was replaced with “being entrepreneurial” and “being an academic” and was used in items such as “Being an academic/entrepreneurial is an important part of my self-image.” Accordingly, these variables reflect conscious choice, thought, and reflection (Murnieks et al., Citation2014) about the sense of self, self-image, and sense of belonging among other entrepreneurial or academic individuals. Both identity scales employed a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 and consisted of eight items. Appendix 1 (question 3) outlines all the variable items.

The statistical structure of the data indicated that these eight items formed two factors in the case of both identity centrality variables: five positively formulated items loading onto one factor and three negatively formulated items loading onto another factor with acceptable reliability indicators of Cronbach’s alpha: αacademic1 = 0.893, αacademic2 = 0.777, αentrepreneurial1 = 0.911, and αentrepreneurial2 = 0.870.Footnote4 Exploratory factor analysis (KMOacademic = 0.854, p < .001; KMOentrepreneurial = 0.890, p < .001) suggested the creation of two composite variables denoting academic identity centrality and entrepreneurial identity centrality was the most optimal (Nardo et al., Citation2005). This ensured that both factors were included to understand each identity variable in full, instead of investigating the subfactors of one construct separately or excluding one of the factors completely (Greco et al., Citation2019). A similar approach was utilized in the original version of the scale (Sellers et al., Citation1997). The reliability indicators for the entire set of eight items in the case of both variables were well above the acceptable threshold of 0.70 (αacademic = 0.883, αentrepreneurial = 0.916) (Nunnally, Citation1978).

Based on these scales, the main dependent variable, hybrid identity centrality, was calculated by taking all observations above the means of entrepreneurial identity centrality (M = 2.68) and academic identity centrality (M = 3.56) variables and by assigning to the simultaneous occurrences, when the identity centrality scores were higher than the means, a value of “1,” meaning “strong hybrid identity centrality.” All other observations representing the cases where a researcher had either a low score on entrepreneurial identity centrality and high score on academic identity centrality or vice versa or low scores on both identity centralities were given a value of “0,” meaning “weak hybrid identity centrality.” Thus, hybrid identity centrality was a binary dependent variable, hence prompting the use of binary logistic regressions in the analysis.

Two independent variables, perceived entrepreneurship strategy and society-industry orientation, were created based on Gibb (Citation2012) and Lam (Citation2010, Citation2011), respectively. Both variables relied on a 5-pointFootnote5 Likert scale. The perceived strategy comprised 12 items to which the respondents were asked to reply, for instance, whether innovation was a key focus of the university strategy, whether the university rewarded work on promoting entrepreneurship, whether it made entrepreneurship training available to all staff, and so forth (Gibb, Citation2012).

Based on the statistical structure of the data, perceived entrepreneurship strategy was a two-factor variable, where the first and second factors accounted for about 50 percent and 12 percent, respectively, of the explainable variance.Footnote6 Thematically, one factor was focused on the availability of entrepreneurship training and support at a university (which we labeled “entrepreneurship strategy implementation”), and another factor was focused on general strategic aspects, such as the commitment of the faculty leadership to supporting entrepreneurship, university rewarding work on promoting entrepreneurship, and so forth (labeled “entrepreneurship strategy”) (see Appendix 1, question 4). The dimensions are derived from the entrepreneurial strategy definitions provided by Etzkowitz (Citation2013) and Gibb (Citation2012). They highlight the theoretical distinction between two aspects. First, the presence of entrepreneurial strategy that indicates the value placed on entrepreneurship within a university is demonstrated through the creation of appreciation of entrepreneurial culture (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Eriksson et al., Citation2021; Gibb, Citation2012; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019). Second, the implementation of entrepreneurial strategy involves expansion of the training and support provision for developing entrepreneurship curriculum, commercialization of research and creation of spin-offs (Gibb, Citation2012; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Schulte, Citation2004). Each factor comprised six items and showed scale reliability above the threshold of 0.70 (α1 = 0.846, α2 = 0.906) (Hair et al., Citation2010). Both factors were used as separate variables to identify the most influential factors, given their statistical and thematic distinctiveness.

The second independent variable, the researchers’ society-industry orientation, captured the respondents’ willingness to alter their research plans to accommodate industrial or societal demands and pursue industrial collaboration for scientific advancement (Lam, Citation2010, Citation2011). The respondents assessed their attitudes toward cooperation with industry and society on an agreement scale from 1=“Totally disagree” to 5=“Totally agree.” Society-industry orientation was a 10-item variable (α = 0.893). In the research model, this variable also acted as a moderator of the relationship between entrepreneurship strategy implementation and hybrid identity.

The analyses were adjusted for a set of control variables, including discipline and position held by the respondents, their gender, age, academic research experience, entrepreneurship experience, and the home university, all of which previous research has shown to be relevant aspects when assessing individuals’ engagement in academic entrepreneurship (Perkmann et al., Citation2013; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). Appendix 1 outlines the main questions included in the survey, as well as some measurement details.

Measurement validity

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed using AMOS 27 statistical software to assess the reliability and demonstrate convergent and discriminant validity of all the multi-item constructs. shows the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients and standardized factor loadings. All the alpha values are above 0.80, indicating excellent reliability (Nunnally, Citation1978). The item-total correlations of all variables demonstrate reliability as well (Bland & Altman, Citation1997).

Table 3. Results of CFA, reliability and validity analysis of variables.

Several commonly tested fit indices (for example, χ2, TLI, CFI, RMSEA) demonstrate that the measurement models of the multi-item constructs fit the data sufficiently well. The results also show acceptable convergent validity because the standardized loadings of the majority of items are over 0.50 and composite reliability (CR) above 0.80 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

The average variance extracted (AVE) from each construct tends to be greater than or at least (if rounded up) equal to the variance shared between that construct and the other constructs (Farrell, Citation2010), indicating sufficient discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The AVE values of three constructs, academic identity centrality (0.499), entrepreneurship strategy implementation (0.480), and society-industry orientation (0.451), were below the cutoff value of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Still, the assessment of AVE values and construct correlations indicate that all constructs, despite the low AVE values, explain more of their own variance than sharing common variance with each other. Hence, we consider that the studied constructs are valid for the analyses (see for example, West & Gemmell, Citation2021).

Finally, considering that the data were collected through self-reports, the results could be subject to common method bias (CMB). To address this, Harman’s single factor test was conducted using principal component analysis (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The results show that the largest component in the current dataset represents only 16.5 percent of all the items, which is well below the critical threshold of 50 percent, suggesting that CMB does not have an effect on our results.

Analysis and results

In testing the hypotheses, binary logistic regression analysis was employed. shows the descriptive statistics of each variable, and summarizes the correlation matrix. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is <4 for all the variables, which is below the commonly used critical thresholds (Hair et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, the multicollinearity between the analyzed variables did not influence the results.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics.

Table 5. Correlation matrix.

outlines the binary logistic regression results for testing the study hypotheses. The results are presented in four models. Model 1 contains the control variable effects only, and Models 2 and 3 add the main effects by testing H1a, H1b, and H2 of the conceptual model. Finally, Model 4 adds the moderation effects, testing H3a and H3b.

Table 6. Binary logistic regression results.

Model 2 shows that the influence of perceived entrepreneurship strategy or its implementation are not significant for hybrid identity centrality; hence, hypotheses H1a and H1b are not supported. In Model 3, society-industry orientation clearly serves as a strong enabler supporting hypothesis H2 (OR = 1.448, P < .05). Furthermore, the odds of having strong hybrid identity centrality increase significantly when society-industry orientation interacts with the entrepreneurship strategy implementation, as Model 4 shows (OR = 1.411, P < .05). This brings support to H3b, while H3a is not supported.

Even though there is no direct effect from the perceived entrepreneurship strategy, this effect is entirely dependent on individuals’ society-industry orientation. As illustrated in that plots the interaction effect, the entrepreneurship strategy implementation only increases the likelihood of having strong hybrid identity centrality when the level of society-industry orientation is higher. If the society-industry orientation remains low, the potential of strong hybrid identity centrality reduces. In addition, when the perceived entrepreneurship strategy implementation is low, the society-industry orientation alone is insufficient to alter the likelihood of hybrid identity centrality. This implies that if both entrepreneurial strategy implementation and society-industry orientation are perceived as low, academics may choose to focus on a certain identity instead of pursuing different identities simultaneously. Thus, this interaction also suggests that the strategy implementation may impact more academics who believe that research should benefit society, and that the implementation might be less effective for academics who are less inclined to a society-industry interaction.

Figure 2. Moderation effect of society-industry orientation on the relationship between perceived entrepreneurship strategy implementation and strength of hybrid identity centrality.

Zooming into the control variables, the results show that, for hybrid identity centrality, the age and gender of an academic are not influential factors, unlike prior entrepreneurship experience (P < .05 in Model 4Footnote7). Thus, academics who are more experienced in entrepreneurship tend to have stronger hybrid identity centrality. This result is aligned with existing theoretical insights on the important role of prior entrepreneurial experience for having a strong entrepreneurial identity centrality (Jain et al., Citation2009; Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996) and with the robustness checks reported in the following section. Regarding the differences among disciplines, they are not as pronounced, despite the varying goals of fundamental research and applied research being more prevalent in economics, business, and social sciences versus the humanities. Even though entrepreneurship is generally associated with applied research and, hence, the fact that researchers in this field could be more responsive to the strategic actions of promoting entrepreneurship, we do not observe the systematic effects of discipline on hybrid identity centrality.

Robustness checks

To test the robustness of the obtained results, we first used alternative versions of coding the dependent variable. In these tests, we considered that hybrid identity centrality can have different forms. Having focused on a strong hybrid in the main analyses, when both entrepreneurial and academic identities scored above the means, we also analyzed other possible hybrids: academic identity is weak and entrepreneurial identity is strong (n = 85), academic identity is strong and entrepreneurial identity is weak (n = 87), and both identities are weak (score below the means) (n = 59). These analyses have indicated that the society-industry orientation plays a significant role in all the coding versions, except for the latter (the effect being positive when entrepreneurial identity centrality is strong and negative when academic identity centrality is strong). None of the alternative regression models revealed the moderation effect, highlighting it as a unique effect pertinent to cases in which both academic and entrepreneurial identities are strong.

In addition, we then conducted a complementary set of linear regression analyses for entrepreneurial and academic identity centralities separately. These tests have revealed different patterns of enablers from those associated with the state of strong hybrid identity centrality, yet have confirmed the divergent effect of society-industry orientation (Appendix 2).

The perceived entrepreneurship strategy has a positive and significant association with academic identity centrality. This suggests that the more a university strategically promotes entrepreneurship among researchers, the more likely researchers are to reinforce their academic identity centrality. In other words, the academic identity may become central for the researchers. At the same time, society-industry orientation is negatively associated with academic identity centrality. This confirms previous studies that found a potential conflict between a strong academic identity centrality and an orientation to industrial/societal ties and adapting one’s research to the needs of industry or society (for example, de Silva, Citation2016; Jain et al., Citation2009). In the case of entrepreneurial identity centrality, society-industry orientation remains a significant enabler. Among the control variables, academic research and entrepreneurship experience (measured in years), as well as discipline, deserve closer attention due to their logical alignment with the main hypotheses testing results. Academics who are more experienced in entrepreneurship expectedly tend to have stronger entrepreneurial identity centrality (P < .001), while those with more research experience tend to have stronger academic identity centrality (P < .01). Furthermore, academics from an economics and business background are associated with stronger entrepreneurial identity centrality compared to those from the humanities (P < .05).

Discussion

The present study sought to contribute to the scholarly understanding of academic entrepreneurship by investigating how perceived organizational strategy, its implementation and individual factors (personal beliefs, values, and views) shape the identity of academics. More specifically, to complement previous studies on hybrid identity and complementarity between academic and entrepreneurial activities (Jain et al., Citation2009; Meek & Wood, Citation2016; Sieger & Monsen, Citation2015; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021), the current study identified factors that can support the development of strong academic and entrepreneurial identities simultaneously, indicating hybrid identity centrality among university researchers. The results show that hybrid identity centrality is not directly shaped by organizational factors, such as perceived entrepreneurship strategy and its implementation, but by individual factors, specifically the society-industry orientation of researchers. The effect of perceived strategy implementation on hybrid identity centrality is dependent on the society-industry orientation of the researchers. This finding extends prior research by demonstrating how mutually aligned factors at different levels, organizational and individual, can shape the hybrid identity (Balven et al., Citation2018; Sandström et al., Citation2016). This highlights the complex interplay between individual orientations and organizational strategies in the formation of hybrid identities.

Theoretical contributions

The present study has been motivated by the psycho-sociological perspective on entrepreneurship, specifically the application of identity theories (Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002; Stryker & Burke, Citation2000), to understand how university researchers can combine their academic identity with an entrepreneurial one (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2009; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the present study makes important theoretical contributions.

First, this study enriches the academic entrepreneurship literature by adding to the conversation on the complementarity of the multiple role identities of academics (O’Kane et al., Citation2020), particularly the complementarity of academic and entrepreneur identities (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2009; Miller et al., Citation2018; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). While most individual-level studies have focused on identity change, indicating a shift from an academic to entrepreneurial identity (Hayter et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2009), this study is among the first to provide empirical evidence on the hybrid identity centrality of researchers in the context of a university undergoing an entrepreneurial transition (Feldmann, Citation2014; Wang, Cai, et al., Citation2021; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2020). By combining insights from role and social identity theories (Brewer & Pierce, Citation2005; Burke, Citation2006; Stets & Burke, Citation2000; Stryker & Burke, Citation2000) with research on entrepreneurial identity (Sieger & Monsen, Citation2015; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021), this study has investigated the enablers of hybrid identity centrality. This adds to the previous research, which has primarily focused on it as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions (for example, Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021). This study also frames hybrid identity centrality as a potential way of resolving the possible inconsistencies between maintaining academic and entrepreneurial identities.

Our main contribution is to the organizational research on academic entrepreneurship (Balven et al., Citation2018; Feldmann, Citation2014; Sandström et al., Citation2016). Universities, under pressure to create greater societal and economic impact (Etzkowitz, Citation2008; Klofsten et al., Citation2019; Siegel & Wright, Citation2015), have adopted new entrepreneurship and impact strategies. The findings of this study suggest that these strategies do matter, specifically in how university researchers perceive them (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Balven et al., Citation2018; Klofsten et al., Citation2019) and how they perceive their different identities. Rewarding researchers’ work on promoting entrepreneurship, enabling entrepreneurship training among other strategic actions at the university coupled with the researchers’ (high) society-industry orientation can increase the odds of having strong hybrid identity centrality. Our contribution lies in demonstrating that the university strategy alone might not be sufficient to enhance strong hybrid identity centrality. Instead, the findings suggest that the society-industry impact orientation of researchers, covering their personal beliefs, values, and views on the university-industry collaboration, moderates the implementation of entrepreneurial strategy (Jain et al., Citation2009; Wagenschwanz, Citation2021) in enabling academics’ hybrid identity centrality. As a result, an individual researcher has the potential to enhance the influence of entrepreneurial strategy implementation on their identity centrality and, hence, exert an effect on subsequent academic entrepreneurial activities (Hardy & Maguire, Citation2008; Rasmussen & Wright, Citation2015). Hence, it appears that the strategy implementation may support only the academics who already are inclined toward society-industry interaction but not those who do not value such engagement. Furthermore, entrepreneurship strategy may even reinforce the academic identity centrality. Emphasizing entrepreneurship at the university may thus evoke resistance among the academics and lead to the enactment of a strong academic identity.

In contrast, the findings show that ascribing simultaneous importance to being entrepreneurial and being an academic is not only an individual process, but it can also be related to perceived organizational factors (for example, Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Van Dijk & Van Dick, Citation2009). Accordingly, the present study shows that the questions of academic entrepreneurship should not be approached only through the individual—whether they are interested or willing to engage in entrepreneurship or societal interaction—but more emphasis could be placed on understanding contextual factors (Eriksson et al., Citation2021; Gibb, Citation2012; Jain et al., Citation2009) and the extent to which the university provides quality training and support to promote entrepreneurship among researchers (Gibb, Citation2012; Lam, Citation2010). Combining the perspective of an individual researcher with the organizational context of an entrepreneurial university (Siegel & Wright, Citation2015) contributes to a better understanding of hybrid identity centrality (Ashforth et al., Citation2008; Jain et al., Citation2009; Roccas & Brewer, Citation2002). The interplay of perceived strategy implementation and individual factors may lead to renegotiating identity and eventual arrival at hybrid identity centrality. Although prior studies have primarily focused on either perceived organizational (for example, Wang, Cai, et al., Citation2021) or individual factors (for example, Sieger & Monsen, Citation2015) to explain the entrepreneurial behavior of academics, the present study has examined both types of factors.

Practical implications

The findings provide practical implications for management and administrators of universities that have recently transitioned into entrepreneurial universities, faculty members interested in developing as academic entrepreneurs, and policymakers working on research support programs. These implications relate to stimulating society-industry orientation among researchers, helping resolve the academic-entrepreneur dilemma, and making respective human resources decisions.

Academic entrepreneurship research has been under criticism for representing academic entrepreneurs as “lonely heroes,” while, in reality, these actors are collaborative beings embedded in their university environment (Eriksson et al., Citation2021). Instead of putting strategic pressure on academics and increasing the identity tensions, the university can systematically help them increase their interest in research valorization activities (for example, conducting socially relevant research, contract research, knowledge transfer, and patenting). Researchers who engage in such activities can inspire others and act as role models (Etzkowitz, Citation1998; Feldmann, Citation2014). Academic entrepreneurs can support fellow researchers, students, or potential beneficiaries of their entrepreneurial actions, highlighting the importance of collaborating with industry (Wang, Cai, et al., Citation2021).

This study emphasizes the uniqueness of hybrid identity centrality when researchers view themselves as academic and entrepreneurial individuals simultaneously and when both identities are important to their personality. Hybrid identity centrality can become a “safe harbor” for researchers who struggle to find their place in the entrepreneurial university transition (Hayter et al., Citation2021). Consciously acknowledging hybrid identity centrality can help researchers in resolving tensions. By enacting their primary academic identity and finding inspiration in societal and/or industrial engagement, researchers can work toward cultivating a new identity—if this process is supported by an organizational strategy implementation that is positively perceived by the researchers (Lam, Citation2010).

The hybrid identity perspective also offers some considerations for employment practices at universities. In the university context, researchers who exclusively identify as entrepreneurs should probably not stay with academia but rather exit to accomplish their entrepreneurial endeavors (for example, through university spin-offs). Hybrid academic and entrepreneurial identity is not necessarily the only identity that an entrepreneurial university should focus on employing, stimulating, and supporting. As a socially embedded institution, the university reflects the diversity of identities and their interplay (O’Kane et al., Citation2020).

For policymakers, the findings suggest that research support programs should be purposefully directed to help academic researchers create an impact beyond citations and theoretical contributions. For example, funding programs can emphasize the need for external engagement and the creation of measurable effects of research projects across different disciplines (for example, social sciences, humanities, law, business, and management, and so on).

Conclusion

Drawing on a sample of 312 researchers from two multifaculty universities, this study investigated the factors that enable hybrid identity centrality—a conscious recognition of being both an academic and entrepreneurial individual—among university researchers. Our findings unveil that researchers’ perceptions of a university’s implementation of an entrepreneurship strategy together with their society-industry orientation significantly influence the likelihood of hybrid identity centrality. Importantly, society-industry orientation moderates the relationship between the perceived strategy implementation and the adoption of a hybrid identity.

The findings of this study extend previous research on entrepreneurial academic identity by offering new insights into the interplay between individual and organizational factors. The study investigated the antecedents of hybrid identity centrality within a university context, framing hybrid identity centrality as a potential solution to the challenges arising from ongoing university transition. This study contributes to the organizational research on academic research by suggesting that the organizational factors, such as the implementation of entrepreneurial strategy, are not sufficient for supporting researchers to adopt a strong hybrid identity centrality, but it is the society-industry orientation of the individual academics that enables these strategy implementations to succeed.

Although this study contributes to the development of knowledge on what enables researchers to excel as academics and entrepreneurs in a university setting, some limitations remain. Similar to the studies of Wang, Soetanto, et al. (Citation2021) and Zhao et al. (Citation2020), which focused on the Chinese context, this study is solely based on the Finnish university context. To further generalize the findings, it would be beneficial to replicate and enrich the current design in a wider context, for example, in European universities that have recently transitioned toward more entrepreneurial academic institutions.

From a study design perspective, the data collected are cross-sectional, and the findings rely on self-reported data. Although other studies motivating the current study face a similar limitation (for example, Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021), this highlights the need for future research that combine individual and organizational factors, and employ more objective measures. To extend the underlying inquiry of “What enables hybrid identity?” in the next step of “How do researchers arrive at hybrid identity?” (Hayter et al., Citation2021), we encourage the use of a longitudinal research design and/or qualitative research methods to deepen the understanding of the enablers of hybrid identity centrality.

We intend to inspire entrepreneurship scholars to analyze ways of encouraging and stimulating entrepreneurially oriented academics, what kind of support works for them to help implement their endeavors, and what hinders their hybrid identity development. Our study provides some preliminary ideas that entrepreneurial strategies at universities may also impact individual identities in unexpected ways. Implementing an entrepreneurship strategy may strengthen academic identity centrality. A more nuanced approach to understanding university-situated identity conflicts and tensions, along with how academics resolve them, can also support moving the identity discourse in academic entrepreneurship forward. Finally, what drives the societal and industrial impact orientation of researchers at the individual level remains an open question for further research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Research Council of Finland (grant number 295960) for funding this research project. We are also very grateful to anonymous reviewers who helped us improve the manuscript in the revision process as well as to Michael Wyrwich for a valuable friendly review of the earlier version of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 An entrepreneurial university can exhibit several characteristics ranging from a primary focusing on the commercialization of research and the creation of research-based spin-offs to a broader emphasis on enhancing the societal and regional impact of the university (Etzkowitz, Citation2013; Hytti, Citation2021; Klofsten et al., Citation2019). Therefore, entrepreneurial activities within the context of entrepreneurial strategies refer to a broad range of activities. These extend beyond the traditional academic roles of teaching and research, and are innovative, carry an element of risk, and lead to (financial) rewards for the individual academic or their institution (Abreu & Grinevich, Citation2013).

2 At the time of the study, the Finnish higher education scene comprised of 14 universities with different profiles: 1 large multidisciplinary university, 1 mid-sized specialized university and 5 multidisciplinary universities, 5 small specialized universities (for example, technology, economics or arts), and two small multidisciplinary universities.

3 The scale has been applied extensively in different research domains (for example, Hashem & Awad, Citation2021; Settles, Citation2004; Wang, Soetanto, et al., Citation2021).

4 The Promax and Varimax rotation confirmed this two-factorial structure of data.

5 The respective survey question (as well as the other questions in the survey) offered a “Do not know” option as one possible answer. The methodological literature offers three main ways of dealing with such a response option coding: exclude them as missing data; recode them to the neutral point of the response scale; or recode them with the mean (Denman et al., Citation2008). The analysis followed the first way because it is the most common in the literature and used the other two recoding options for the comparative analysis.

6 The solution converged in three iterations with a simple structure: KMO = 0.874, P < .001.

7 Running the regressions without this control repeated the results of the study.

8 Information on the type of variable and/or its literature source(s) provided in square brackets next to each question.

9 Item numbering accounts for the statistical data structure.

References

- Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42(2), 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.10.005

- Alsos, G., Høyvarde, T., Hytti, U., & Solvoll, S. (2016). Entrepreneurs’ social identity and the preference of causal and effectual behaviours in start-up processes. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 28(3/4), 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1155742

- Alvesson, M., Lee Ashcraft, K., & Thomas, R. (2008). Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization, 15(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508407084426

- Ashforth, B., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

- Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

- Balven, R., Fenters, F., Siegel, D., & Waldman, D. (2018). Academic entrepreneurship: The roles of identity, motivation, championing, education, work-life balance, and organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0127

- Barrick, M. R., Thurgood, G. R., Smith, T. A., & Courtright, S. H. (2015). Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0227

- Bland, J., & Altman, D. (1997). Cronbach’s alpha. British Medical Journal, 314(7), 572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

- Boal, K. B., & Hooijberg, R. (2001). Strategic leadership research: Moving on. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 515–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00057-6

- Brewer, M., & Pierce, K. (2005). Social identity complexity and outgroup tolerance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271710

- Brousseau, K. R., Driver, M. J., Eneroth, K., & Larson, R. (1996). Career pandemonium: Realigning organizations and individuals. Academy of Management Perspectives, 10(4), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1996.3145319

- Burke, P. J. (2006). Identity change. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900106

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Cunningham, J. A., Lehmann, E. E., & Menter, M. (2022). The organizational architecture of entrepreneurial universities across the stages of entrepreneurship: A conceptual framework. Small Business Economics, 59(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00513-5

- de Silva, M. (2016). Academic entrepreneurship and traditional academic duties: Synergy or rivalry? Studies in Higher Education, 41(12), 2169–2183. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1029901

- Denman, D. C., Baldwin, A. S., Betts, A. C., McQueen, A., & Tiro, J. A. (2018). Reducing “I don’t know” responses and missing survey data: Implications for measurement. Medical Decision Making, 38(6), 673–682.

- Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235

- Eriksson, P., Hytti, U., Komulainen, K., Montonen, T., & Siivonen, P. (Eds.). (2021). New movements in academic entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Este, P., & Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9153-z

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The norms of entrepreneurial science: Cognitive effects of the new university–industry linkages. Research Policy, 27(8), 823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00093-6

- Etzkowitz, H. (2008). The triple helix. University-industry-government innovation in action. Routledge.

- Etzkowitz, H. (2013). Anatomy of the entrepreneurial university. Social Science Information, 52(3), 486–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018413485832

- Farrell, A. (2010). Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty, and Shiu (2009). Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.05.003

- Feldmann, B. D. (2014). Dissonance in the academy: The formation of the faculty entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 20(5), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-08-2013-0124

- Feola, F., Vesci, M., Botti, A., & Parente, R. (2019). The determinants of entrepreneurial intention of young researchers: Combining the theory of planned behavior with the triple helix model. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(4), 1424–1443. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12361

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gibb, A. (2012). Exploring the synergistic potential in entrepreneurial university development: Towards the building of a strategic framework. Annals of Innovation & Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 16742. https://doi.org/10.3402/aie.v3i0.17211

- Greco, S., Ishizaka, A., Tasiou, M., & Torrisi, G. (2019). On the methodological framework of composite indices: A review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Social Indicators Research, 141(1), 61–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1832-9

- Green, S. (1988). Strategy, organizational culture and symbolism. Long Range Planning, 21(4), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(88)90016-7

- Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after Bayh–Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1045–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.04.005

- Guo, F., Restubog, S. L. D., Cui, L., Zou, B., & Choi, Y. (2019). What determines the entrepreneurial success of academics? Navigating multiple social identities in the hybrid career of academic entrepreneurs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.03.003

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Andersson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson.

- Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2008). InstitutionaL entrepreneurship and change in fields. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 261–280). Sage Publications.

- Hashem, H. M., & Awad, G. H. (2021). Religious identity, discrimination, and psychological distress among Muslim and Christian Arab Americans. Journal of Religion & Health, 60(2), 961–973.

- Haynes, S. N., Richard, D., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.238

- Hayter, C. S., Fischer, B., & Rasmussen, E. (2021). Becoming an academic entrepreneur: How scientists develop an entrepreneurial identity. Small Business Economics, 59, 1469–1487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00585-3

- He, H., & Brown, A. D. (2013). Organizational identity and organizational identification: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Group & Organization Management, 38(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112473815

- Henkel, M. (2005). Academic identity and autonomy in a changing policy environment. Higher Education, 49(1–2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2919-1

- Hytti, U. (2021). Introduction: Navigating the frontiers of entrepreneurial university research. In U. Hytti (Ed.), A research agenda for the entrepreneurial university (pp. 1–6). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. (2009). Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy, 38(6), 922–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.02.007

- Klofsten, M., Fayolle, A., Guerrero, M., Mian, S., Urbano, D., & Wright, M. (2019). The entrepreneurial university as driver for economic growth and social change-key strategic challenges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.004

- Lam, A. (2010). From “ivory tower traditionalists” to “entrepreneurial scientists”? Academic scientists in fuzzy university-industry boundaries. Social Studies of Science, 40(2), 307–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709349963

- Lam, A. (2011). What motivates academic scientists to engage in research commercialization: ‘gold’, ‘ribbon’ or ‘puzzle’? Research Policy, 40(10), 1354–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.002

- Lee, E., & Puranam, P. (2016). The implementation imperative: Why one should implement even imperfect strategies perfectly. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1529–1546. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2414

- Mäkinen, E. I., & Esko, T. (2023). Nascent academic entrepreneurs and identity work at the boundaries of professional domains. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 24(3), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/14657503211063896

- Marks, S., & MacDermid, S. (1996). Multiple roles and the self: A theory of role balance. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(2), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/353506

- Meek, W., & Wood, M. (2016). Navigating a sea of change: Identity misalignment and adaptation in academic entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(5), 1093–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12163

- Miller, K., Alexander, A., Cunningham, J. A., & Albats, E. (2018). Entrepreneurial academics and academic entrepreneurs: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Technology Management, 77(1–3), 9–37. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2018.091710

- Murnieks, C., Mosakowski, E., & Cardon, M. (2014). Pathways of passion: Identity centrality, passion, and behavior among entrepreneurs. Journal of Management, 40(6), 583–1606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311433855

- Nabi, G., Holden, R., & Walmsley, A. (2010). From student to entrepreneur: Towards a model of graduate entrepreneurial career‐making. Journal of Education & Work, 23(5), 89–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.515968

- Nardo, M., Saisana, M., Saltelli, S., Tarantola, S., Hoffman, A., & Giovannini, E. (2005). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Methodology and user guide. OECD.

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- O’Kane, C., Haar, J., & Zhang, J. A. (2022). Examining the micro‐level challenges experienced by publicly funded university principal investigators. R&D Management, 52(4), 650–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12511

- O’Kane, C., Mangematin, V., Zhang, J., & Cunningham, J. (2020). How university-based principal investigators shape a hybrid role identity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120179

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. The Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., Mckelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., Fini, R., Geuna, A., Grimaldi, R., Hughes, A., Krabel, S., Kitson, M., Llerena, P., Lissoni, F., Salter, A., & Sobrero, M. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.09.007

- Pilegaard, M., Moroz, P., & Neergaard, H. (2010). An auto-ethnographic perspective on academic entrepreneurship: Implications for research in the social sciences and humanities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2010.50304416

- Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879