Abstract

We examine concurrent sponsors’ entitativity as a driver of people’s intentions to view the sponsored property and ultimately their intentions to purchase from a concurrent sponsor. Entitativity is the degree to which audiences perceive a collective as a group. We consider moderators to the relationship between entitativity and viewing intentions within two sponsorship contexts, namely, sponsors investing financial versus nonfinancial resources in properties. We use factorial survey designs and structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the model across two studies. The results are consistent. Entitativity is positively related to the likelihood of viewing a sponsored property, and viewing intention is positively related to purchase intention. The entitativity–viewing intention relationship is moderated by sponsor sincerity in the context of sponsors investing products/services but not sponsors investing financial resources. Findings are discussed, and avenues for further research drawn.

Sponsorship has become one of the fastest-growing marketing platforms and is considered a key communication tool. Consequently, marketing managers are increasingly accountable for their sponsorship investments. Accountability is often evaluated through the number of times a property is “eyeballed” (Kourovskaia and Meenaghan Citation2013) and consumers’ purchase intentions (Ngan, Prendergast, and Tsang Citation2011). However, such outcomes are investigated within sponsor–property dyads, despite properties primarily having multiple, concurrent sponsors (Groza, Cobbs, and Schaefers Citation2012). For example, the National Basketball Association (NBA) is linked to 245 sponsors, and the English Premier League to 87 (Lee and Ross Citation2012).

Concurrent sponsorships involve at least two brands simultaneously sponsoring the same property (Carrillat, Harris, and Lafferty Citation2010). Research on concurrent sponsors is anchored in attribution (Ruth and Simonin Citation2006), categorization (Groza, Cobbs, and Schaefers Citation2012), and congruity and associative learning (Gross and Wiedmann Citation2015) theories. These are pertinent to our understanding of the outcomes of concurrent sponsorships, but more work is needed on what characterizes collectives of concurrent sponsors. With this in mind, social psychology informs us that collectives are characterized by the degree to which people perceive the aggregates that compose them as groups (Svirydzenka, Sani, and Bennett Citation2010). This is known as entitativity (Lickel et al. Citation2000). Recently, entitativity has been applied to concurrent sponsorships. Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous (Citation2015) found entitativity drives how each sponsor’s image becomes part of a group stereotype that is generalized to all other sponsors in the collective, above and beyond conceptual similarity between them.

This research builds on Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous (Citation2015) by addressing two research gaps. First, scant work has focused on the link between entitativity of concurrent sponsors and behavioral outcomes in relation to either properties or sponsors. Yet entitativity is generically linked to behavioral outcomes in marketing (Smith, Faro, and Burson Citation2013). Meanwhile, a sponsored property’s image is not only “influenced by the sponsor’s image, but also by the images of possible co-sponsors” (Henseler, Wilson, and De Vreede Citation2009, p. 249). Subsequently, image perceptions are known to affect behavior. Thus, any perception formed of a collective of sponsors likely affects behavioral intentions. Specifically, entitativity of concurrent sponsors conceivably influences people’s viewing intentions, defined as an audience’s willingness to watch or follow a sponsored event (see Yang and Smith Citation2009). A good audience-following for a property is important for both property rights holders and sponsors. For rights holders, a larger audience keeps down operational costs per person, increases event-day revenues through secondary spends, and attracts future sponsorships. For sponsors, a larger audience means increased exposure. However, we have little understanding of how audiences’ viewing intentions are affected by sponsors in general (Olson Citation2010) and entitativity of concurrent sponsors in particular. This link between entitativity and viewing intentions is underresearched yet is critical because (a) the majority of properties have concurrent sponsors and (b) viewing intentions determine the success of properties. Our first and key objective is, therefore, to examine the relationship between concurrent sponsors’ entitativity and people’s intentions to view the property.

Second, sponsors fall into two distinct categories: official financers (“financers”), who invest financial resources, and official providers (“providers”), who invest nonfinancial resources (products/services) in properties (Meenaghan Citation1991). Financers seek image improvement, while providers seek to showcase their products/services during a property’s run (Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2012). Yet despite calls for identifying potential differences in people’s responses to these different sponsorship types (e.g., Deitz, Myers, and Stafford Citation2012), our current knowledge is negligible. Hence, our second objective is to disentangle financers and providers and examine their respective impacts on viewing intentions within concurrent sponsorship contexts.

In addressing these gaps, three key theoretical contributions are made to the sponsorship literature. First, we begin to inform research into sponsored properties, which has surprisingly lagged behind research on sponsors. Yet sponsorships are put in place to benefit both sides of the sponsorship agreement. While there is evidence to show that audience attachment toward properties drives attachment toward sponsors, we demonstrate how perceptions of sponsors themselves drive audiences’ viewing intentions toward properties. Second, and relatedly, we build our research on the reality of sponsorship arrangements involving multiple cosponsors, rather than examining a sponsor–property dyad, as has tended to be the norm in sponsorship work to date. In doing so, we apply the concept of entitativity from social psychology to concurrent sponsorships. Entitativity has been found in social psychology to drive behavioral intentions. Thus, when multiple sponsors are involved with a property, and behavioral intentions of audiences underpin the sponsorship motivations of both sponsors and properties, entitativity may play a role in both sides of the sponsorship agreement reaching their objectives. In this context, we posit and find that entitativity of concurrent sponsors drives viewing intentions toward properties.

Third, we further enhance the realism of our research by distinguishing between two sponsorship types. Previous research has generally amalgamated financer and provider sponsorships into one category. Our disentanglement of the two sponsorship types results in finding differential audience responses toward properties, as concurrent sponsors’ entitativity increases. In turn, we begin to address calls for a greater understanding of audience responses to different sponsorship contexts.

In terms of managerial contributions, we show that the entitativity of both financers and providers can affect audiences’ intentions to view the property and, from there, their intentions to purchase from a concurrent sponsor. These findings identify the need for concurrent sponsors to cooperate to develop perceptions of “groupness” in the eyes of the public. At present, most sponsorship agreements are not geared toward sponsors working together; neither is it customary for them to do so. In addition, we find that properties themselves can further harness the benefits of concurrent providers’ entitativity when these sponsors are perceived as increasingly sincere. Taking the two findings together, entitativity benefits are to be had for both sponsors and properties, so both should work toward fostering perceptions of sponsors’ “groupness.” In addition, properties and providers should communicate providers’ property-serving motivations for sponsoring the property to better harness the benefits of entitativity.

The remainder of this article is as follows. First, relevant sponsorship, brand alliance, and entitativity literature are outlined. Next, the conceptual framework and hypotheses are presented. The methodology adopted to test the model then precedes the results of two studies. We conclude with theoretical and management implications, limitations, and future research.

SPONSORSHIP

Sponsorship is a contractual agreement involving a company’s financial or in-kind investment in a third-party entity in return for access to its exploitable commercial potential (Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2014; Meenaghan Citation1991). Usually, third-party entities sign contractual agreements with multiple sponsors, giving rise to concurrent sponsorships.

Concurrent Sponsorships

The concurrent sponsorship literature is fragmented and informs us of largely disparate findings. Ruth and Simonin (Citation2006) established that people’s likelihood of attending an event increased if at least two commercially oriented cosponsors were present, while Groza, Cobbs, and Schaefers (Citation2012) found that a property was evaluated more positively when an incongruent concurrent sponsor was a lower-tier rather than a title sponsor. Meanwhile, Cobbs, Groza, and Rich (Citation2015) found that a concurrent sponsor’s brand- and purchasing-related outcomes were affected by a portfolio-fit interaction, and Gross and Wiedmann (Citation2015) discovered attitude and image carryover effects from one sponsor to another. Finally, Carrillat and colleagues (Carrillat, Harris, and Lafferty Citation2010; Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous Citation2015) revealed that people were more likely to confuse concurrent sponsors’ images if the sponsors had similar brand concepts than if they had dissimilar brand concepts. Pertinent to this article, Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous (Citation2015) provided evidence that concurrent sponsors’ entitativity was a driving force behind their findings.

Providers and Financers Alliances

Sponsorship is a natural context for cobranding, given it entails an agreement between sponsors and properties such that each can leverage its association with the other (Tsiotsou, Alexandris, and Cornwell Citation2014). Sponsorship arrangements are therefore a form of brand alliance. Brand alliances range from functional (with brands physically integrated into a product) to image based (with brands just featured in joint promotions) (Rao, Qu, and Ruekert Citation1999). Academic interest in alliances is increasing. Apposite to this article, functional alliances tend to be evaluated differently from image-based alliances (Lanseng and Olsen Citation2012). For example, if brands involved in an image-based alliance are not consistent in their image, this can result in an incongruent image of the cobranded offering, which negatively affects consumer perceptions of that offering. By contrast, consumers can more rationally perceive how the different strengths of the individual brands complement each other to improve the functional performance of the cobranded offering in functional alliances (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014).

The analogy to sponsor type is stark. Providers, by definition, invest their products and/or services in the running of properties, which appears akin to functional alliances (Mazodier and Merunka Citation2014). Conversely, financers invest funds in a property so that they can leverage the image associated with the property (Carrillat and d’Astous, Citation2012). In this sense, financers are image-focused sponsors, while providers are instrumentally related to a property’s performance (Pope, Voges, and Brown Citation2009). Thus, lessons can potentially be applied from the brand alliance literature to the sponsorship context, when sponsorship types are disentangled.

Entitativity

In marketing, entitativity has underpinned people’s responses to charitable giving (Smith, Faro, and Burson Citation2013), European Union labeling (Diamantopoulos, Herz, and Koschate-Fischer Citation2017), and concurrent sponsorships (Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous Citation2015). That said, “there are only very few studies which draw on the concept of entitativity” (Diamantopoulos, Herz, and Koschate-Fischer Citation2017, p. 185). Therefore, examining entitativity within its original social psychology domain is warranted. Here, entitativity is the extent to which a collective is perceived as a social group (Svirydzenka, Sani, and Bennett Citation2010), as opposed to whether it is actually a group. This means a collective’s entitativity varies on a continuum (e.g., Hamilton, Sherman, and Lickel Citation1998), whereas its actual groupness is fixed.

Lickel et al. (Citation2000, p. 224) argue that “entitativity is an important dimension on which groups can be compared and that … entitativity strongly influence[s] how people think about social groups.” First, studies have shown that entitativity is associated with collectives being treated as single entities (Hamilton and Sherman Citation1996). This is due to perceivers increasingly forming “coherent impressions of such groups” at the moment information is processed, in much the same way perceivers process information about individuals (McConnell, Sherman, and Hamilton Citation1997, p. 751). Second, entitativity is associated with group stereotypes, resulting in individual members’ traits being generalized to other members. “Once a perceiver has extracted the stereotype, additional exemplars are processed in terms of this group impression, not as individuals” (Crawford, Sherman, and Hamilton Citation2002, p. 1077). Third, entitativity is associated with inferences of greater intentionality in a collective’s actions (O’Laughlin and Malle Citation2002). Intentionality refers to whether actors intended an event to occur (Varela-Neira, Vázquez-Casielles, and Iglesias Citation2014) and is one of the first inferences people make about others (Malle and Holbrook Citation2012). Finally, entitativity is associated with behaviors being attributed to dispositional rather than situational factors (Yzerbyt, Rogier, and Fiske Citation1998), and “others” not directly responsible for an act of “another” being attributed collective responsibility for that act (Lickel et al. Citation2003).

While people are often the subject of entitativity studies, nonhuman animals/objects are also studied. Pertinently, as people regard brands “as social categories in much the same way that occupational groups …, ethnic groups …, and genders are regarded as social categories” (MacInnis and Folkes Citation2017, p. 357), entitativity is relevant to brand-related studies.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

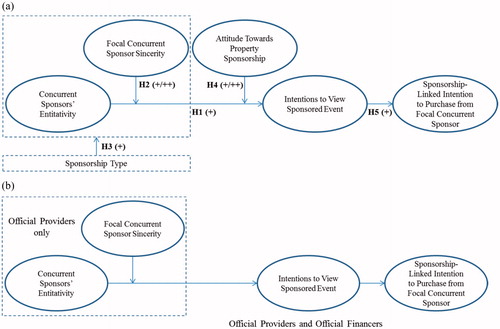

The conceptual framework () is built on the premise that concurrent sponsors’ entitativity is positively related to property viewing intentions, which is itself positively related to purchase intentions toward a focal concurrent sponsor. An indirect entitativity–purchase intention relationship is expected, because people’s attention is directed toward the sponsored property. As such, properties are linchpins of sponsors’ persuasion attempts.

Focal Concurrent Sponsor

In line with concurrent sponsorship/alliance literature, we focus on a focal concurrent sponsor (e.g., Ruth and Simonin Citation2006). That is, the model has implications for all concurrent sponsors, so we “take the perspective of a consultant” to a focal sponsor in a cobranding arrangement (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014, p. 103). Focusing on a single concurrent sponsor is an appropriate strategy because sponsors are interested in outcomes for their own brand and not those of other sponsors. Further, a property usually has a substantial number of concurrent sponsors—even into the hundreds (Lee and Ross Citation2012). Focusing on so many sponsors is burdensome for respondents. Conversely, artificially limiting the number of sponsors, at least initially, may reduce ecological validity. Hence, we focus on one sponsor within a concurrent sponsor collective.

Hypotheses Development

Sponsorship enhances viewing intentions (Olson Citation2010; Walker et al. Citation2011), not least because sponsors make properties “more exciting, entertaining and attractive” (Crompton Citation2014, p. 420). Sponsors generally increase properties’ profiles (Sleap Citation1998) and signal that properties are more professional and/or of higher quality (e.g., Roy and Cornwell Citation2003). For example, sponsorship can enhance a property’s format through structural changes (Crompton Citation2014) or by paying for the best athletes to compete. Similarly, “[s]ponsorship dollars bring revenue that buys better facilities, additional staff and a greater experience for participants” (Delpy, Grabijas, and Stefanovic Citation1998, p. 93). This “greater experience” increases the likelihood people will follow (watch) the property (e.g., Wakefield and Blodgett Citation1994), as customers “gain from purchasing goods and services that are associated with signals of high quality,” rather than low quality (Connelly et al. Citation2011, p. 45). Given the positive sponsorship–viewing intentions relationship, we now focus on the relationship between concurrent sponsors’ entitativity and viewing intentions.

First, there is evidence that entitative groups are collectively attributed responsibility for others’ actions (Lickel et al. Citation2003). Transferring this into the sponsorship arena, while properties’ rights holders have direct responsibility for the properties themselves, sponsors are also, to a degree, held accountable for properties’ successes (Messner and Reinhard Citation2012). For example, Formula One has “automobile component manufacturers, aerodynamic engineering firms, or other high tech” providers responsible for teams’ performances (Cobbs et al. Citation2017, p. 98). We see, in this context, a functional brand alliance anchored in sponsors’ tangible contribution to the property, resulting in the betterment of the overall spectacle on offer to audiences (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014). Similarly, while not instrumentally related to a property’s performance (Pope, Voges, and Brown Citation2009), the revenue provided by financers can fund better facilities, additional staff, and, by extension, a greater experience for the audience (Delpy, Grabijas, and Stefanovich Citation1998; Mazodier, Quester, and Chandon Citation2012). In addition, enhanced responsibility (as a result of increased entitativity) suggests greater sponsor investment (e.g., time, energy, products/services, and/or finance) in a property, signaling the property’s sponsors have an increasingly market-prominent position within their respective industries (see Henderson, Beck, and Palmatier Citation2011). In turn, signals pertaining to the property’s sponsors provide additional information about the property itself (Kelly et al. Citation2016). Specifically, market-prominent sponsors are associated with market-prominent properties (Wakefield and Bennett Citation2010), the latter generally regarded as being of high quality, particularly relative to smaller-sized properties. Given that people gain more from higher-quality products than lower-quality products (Connelly et al. Citation2011), people’s propensity to follow the property should increase (Wakefield and Blodgett Citation1994).

Second, as entitativity increases, concurrent sponsors’ images coalesce in people’s minds, resulting in sponsorship contexts akin to one sponsoring brand. Here, a property is associated with one sponsor’s image rather than multiple sponsors’ images, which may be different from one another. Being associated with a single sponsor image is beneficial for properties, as audiences fail to identify a consistent image with properties that have multiple sponsor images (Cobbs, Groza, and Rich Citation2015). Image consistency facilitates and reinforces people’s expectations of a brand and enhances processing fluency (Chien, Cornwell, and Pappu Citation2011). In turn, favorable evaluations develop (e.g., Lee and Labroo Citation2004), which are themselves known to positively influence behavioral intentions. Consequently, as concurrent sponsors’ entitativity increases, viewing intentions should also increase.

Third, consumers perceive intentionality behind brands (Kervyn, Fiske, and Malone Citation2012). In turn, the factors that can augment consumers’ perceptions of a brand’s intentionality affect their brand evaluations (Puzakova, Kwak, and Rocereto Citation2013). Meanwhile, social psychology informs us that entitativity augments intentionality (O’Laughlin and Malle Citation2002). Relating this to concurrent sponsorships, people perceive commercial intentions behind sponsorships, especially in elite and sporting contexts (Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2012) or if sponsors are perceived to be market-prominent (Kim et al. Citation2015). Hence, people should perceive increasing commercial intentions of sponsors as entitativity increases. The fact that a property is sponsored by sponsoring brands that have greater commercial intentions signals to audiences that the property is commercially attractive. In other words, as entitativity increases, so does the sponsored property’s perceived value. Subsequently, this image, based on a property’s attractiveness to sponsors, is likely to be associated with perceptions of quality (e.g., Whang et al. Citation2015). Again, as audiences benefit more from higher-quality products than lower-quality products (Connelly et al. Citation2011), viewing intentions increase (Wakefield and Blodgett Citation1994).

We also observe sponsors’ intentionality enhancing or maintaining a property’s commercial value. For example, a “pop festival sponsored by Pepsi-Cola gains from [Pepsi’s] desire to make sure the event is a huge success. We would all rather sponsor the team that wins rather than the team that loses” (Roy and Cornwell Citation2003, p. 393). Similarly, the joint statement from AB InBev, Adidas, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, and Visa, which “reiterated our expectations for robust reform” in FIFA (Homewood Citation2015), is an extreme example of concurrent sponsors’ collective intentionality behind a sponsorship. Thus:

H1: Concurrent sponsors’ level of entitativity is positively related to viewing intention.

People attribute one of two sets of motives for sponsor involvement with a property: sincere (property-serving) or insincere (sponsor self-serving) motives (Messner and Reinhard Citation2012). While people are generally happy for sponsors to have self-serving motives, sincere “brands engaged in sponsorship activities are perceived as seeking the interest of the sponsored entity in addition to their own” (Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2012, p. 563). Hence, when sponsors are sincere, property followers are more confident that the sanctity and integrity of the property are upheld and are thus more likely to watch it (see Meenaghan Citation2001). We therefore expect perceived sincerity to have an impact on the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention. Entitative sponsors’ traits are encoded at the group level before being disseminated to all other concurrent sponsors (Crawford, Sherman, and Hamilton Citation2002). Hence, in entitative situations, when one sponsor is perceived as (in)sincere, all sponsors are perceived as (in)sincere (see Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous Citation2015). Combining this with the knowledge that entitativity is positively associated with perceived intentionality (O’Laughlin and Malle Citation2002), people are likely to perceive entitative concurrent sponsors’ intentionality more favorably when concurrent sponsors are property serving. Indeed, “[i]ntentionally performing a moral action elicits a more positive attitude than when the moral action is unintended” (Folkes and Kamins Citation1999, p. 255). For example, to prevent National Football League (NFL) playoff games from being “television blackouts” in local areas, “sponsors stepped in and prevented a catastrophe, purchasing a combined 21,000 tickets [which were then made] available for free to military veterans and their families” (Feloni Citation2014). Hence:

H2: There is a positive relationship between the level of entitativity of a group of brands sponsoring an event and consumers’ intentions to view this event. Moreover, this positive relationship is stronger as the perceived sincerity of sponsors increases.

For both providers and financers, the sanctity and integrity of a property are upheld when sponsors are entitative and sincere. However, as providers and financers have different sponsorship roles, it is expected the interaction between entitativity and sincerity on viewing intention is stronger for providers than it is for financers. For entitative providers, sincerity manifests itself through direct property enhancement. For example, providers’ products/services free up resources for a property rights holder to enhance other aspects of its event. Further, because providers desire showcasing their products (Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2012) it is likely these resources are newer and/or of a higher quality than the products held by a rights holder as a consequence of previous sponsorships. Hence, the property’s weakness on a “functional attribute is offset by the partner [sponsor] brand’s strength on that attribute … thereby strengthening the performance of the joint offering” (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014, p. 109). Conversely, financers’ sincerity manifests itself through sponsors not detracting from the property, especially given that these sponsor types are less involved in the day-to-day running of properties. Instead, financers seek hedonic (image) consistency between the property and themselves. Meanwhile, when brands are high on hedonic consistency but low in integration, “consumers can more easily disentangle the benefits from either brand[s], and thus the leverage from hedonic consistency is less significant, though still positive,” for the property brand (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014, p. 110). In other words, consumers can more easily disentangle entitative and sincere financers’ lack of detraction from the property’s professional and/or higher-quality signals. Hence, compared to entitative and sincere providers, there are fewer (if any) additional property enhancement perceptions resulting from entitative and sincere financers. Thus:

H3: The interaction between entitativity and sincerity on viewing intention is stronger for providers than it is for financers.

Attitudes inform behaviors, and attitudes toward sponsorship are associated with viewing intention in dyadic sponsorship contexts (e.g., Olson Citation2010). While a positive sponsorship–property association generally exists (Pope, Voges, and Brown Citation2009), there are occasions when people’s attitudes toward sponsorship are negative and this attitude adversely affects viewing intention. For instance, sponsors’ involvement can invoke operational and reputational risk for a property. Operational risk occurs when, for example, sponsors apply undue influence on a property’s “content, timing, location or participants. The primary source of reputational risk is increased public sensitivity to the negative health impacts of some product categories … that may make it contentious for a sport property to partner with companies in these product classes” (Crompton Citation2014, p. 420). As operational or reputational risk increases, people question the sponsorship, and viewing intentions may drop (Olson Citation2010; Ruth and Simonin Citation2006). Similarly, we propose that people’s attitude toward a particular sponsorship affects the entitativity–viewing intention relationship. Specifically, the direction of the valence of people’s attitude toward a sponsorship should spill over to the allied brands in general, and to the property in particular (see Olson Citation2010). Subsequently, viewing intention will be affected. Hence, if people perceive entitative concurrent sponsors’ increasing intentional potential to influence a property’s running as negative, their evaluations of the property should also be affected in this direction. For example, people with “negative attitudes toward commercialization may think that sponsors associate themselves with a sponsee [property] for the wrong motives” (Woisetschläger, Haselhoff, and Backhaus Citation2014, p. 1497). Conversely, if people’s attitude toward the sponsorship is positive, the stronger the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention will be. It follows that:

H4: The relationship between the level of entitativity and viewing intentions depends on people’s attitude toward the providers’/financers’ sponsorship. When attitude toward the sponsorship is positive, the positive relationship between entitativity and viewing intentions is strengthened. When attitude toward the sponsorship is negative, the relationship becomes negative.

Property followers are generally thought to act favorably toward sponsors by, for example, being more likely to purchase from them (Speed and Thompson Citation2000). First, properties and, in particular, events are often dependent upon sponsors (Mazodier and Rezaee Citation2013), so the more audiences support a property (intend to view an event), the more grateful they will feel to the sponsors. Indeed, people believe that sponsorship, unlike advertising, is something brands do not have to engage in, and so brands’ involvement with a property through sponsorship is perceived as more altruistic than advertising (Meenaghan Citation2001). This leads to reciprocity, whereby the audience supports the sponsor because the sponsor supports the property (Pracejus Citation2004). Second, audiences who are more likely to follow a property likely have higher purchase intention toward sponsors because of their greater exposure to the sponsoring brands (Olson and Thjømøe Citation2003). Consequently:

H5: Viewing intentions are positively related to people’s intention to purchase from the focal concurrent sponsor.

GENERAL METHODOLOGY FOR STUDIES 1 AND 2

We tested the hypotheses via two separate studies, in a bid to achieve external validity. As explained by Mutz (Citation2011), achieving external validity is inductive and emerges from an accumulation of studies across different settings and samples. The objective is to increase the probability that generalization can hold under alternative scenarios. Mutz (Citation2011) recommends that research questions be empirically examined by comparing results from studies in one setting with another. We applied this recommendation in designing two specifically distinct studies, across two separate populations, where Study 1 is replicated and extended in Study 2, to gauge replicability and generalizability. Specifically, our second study is a constructive replication of the first, in that it tests a similar model to the first study but varies the operationalization of constructs (see Barrick et al. Citation2007). Constructive replications are essential for establishing external validity and accumulating scientific knowledge (Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan Citation2007), because such replications seek not only to provide additional evidence for or against an existing finding but also to refine or extend findings (Hüffmeier et al. Citation2016). Study 2 refines and extends Study 1’s findings by (a) using multiple market research panels instead of students, (b) limiting the number of concurrent sponsors in each vignette to three, (c) using altered measures for constructs, and (d) measuring various fits (given that fit is the main predictor variable in most sponsorship literature and one of the few known major drivers of property-related outcomes in dyadic sponsorship contexts (e.g., Olson Citation2010). Despite these refinements and extensions, our results are consistent across both studies. This provides a good degree of confidence in our findings.

Vignette design

The context of the study is sport, given that the majority of sponsorship is directed there. We use a mixed-design fractional factorial survey design (FSD) with experimental vignette partitioning (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010), following best-practice recommendations (Aguinis and Bradley Citation2014). Specifically, the design simultaneously exposes respondents to multiple vignettes, which is typical for most FSD applications (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015). The design allowed us to ask each respondent about both providers and financers separately and to expose different respondents to different combinations of sponsors (Nike versus Adidas) and properties (the National Provincial Championship versus the European Games) in a bid to mitigate any familiarity bias. The model was then tested on people’s responses to both providers and financers vignettes (see ), because “when a group is viewed in the context of a contrast group, the distinctions between the groups in the form of stereotype formation and use become more likely” (Crawford, Sherman, and Hamilton Citation2002, p. 1091). Together, the two vignettes make a vignette pair. In the analysis, answers to providers and financers questions remained separate so that the model could be tested against both sponsorship contexts, while answers pertaining to different sponsors (Nike/Adidas) and properties (National Provincial Championship/European Games) were collated after establishing nonsignificant differences.

Specifically, “[t]he goal of vignette treatments is to evaluate what difference it makes when the actual object of study or judgment, or the context in which that object appears, is systematically changed in some way” (Mutz Citation2011, p. 54). We create different vignettes with the expectation that people’s responses to different named concurrent sponsors, events, or both, are not substantially different from one another across the respective providers/financers vignettes. If our expectations hold, we can discount the named sponsor or event as being the main causes of relationships and subsequently collapse our vignettes to produce (a) an overall providers and (b) an overall financers context where we do expect to find differential contextual effects on viewing intentions. The collapsing of vignettes is appropriate because the named focal concurrent sponsors and properties in the vignettes are of little interest in this study, given our primary objective is to examine the relationship between concurrent sponsor entitativity and viewing intentions. Thus, any potential confounding involving the named sponsor or event (or combination of both) with this article’s constructs of interest can be regarded as “higher order interaction effects of minor interest, which can be assumed to be zero or negligible” with respect to the relationships under investigation (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010, p. 132). In other words, if responses to the named sponsor and event in the different providers/financers vignettes are not substantially different, it means respondents are essentially exposed to the same two vignettes (a “providers” and a “financers” vignette) for the purposes of our study. Thus, responses to the relationships under investigation can be compared across respondents (Aguinis and Bradley Citation2014). Moreover, the same number of manipulated factors and measurements are used across all vignettes. This, coupled with our fractional vignette design, ensures that any (non)significant relationships between our constructs of interest at the analysis stage have meaningful interpretation (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010). Nevertheless, we also include responses to the named sponsor and property as controls to further mitigate against potential bias.

In addition, we examine whether (in)entitativity interacts with focal sponsor (in)sincerity. When concurrent sponsors are entitative, the focal concurrent sponsor’s (in)sincerity becomes a stereotype of the group, meaning all concurrent sponsors are associated with the trait (see Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous Citation2015). However, when concurrent sponsors are inentitative, a focal concurrent sponsor’s (in)sincerity remains an “individual trait inference” (Crawford, Sherman, and Hamilton Citation2002, p. 1077). Thus, sincerity can be perceived at the “group” or at the “individual” sponsor level, depending upon (in)entitativity. As such, we turn to prototype theory to ensure vignette responses are captured consistently while still adhering to an entitativity framework. Specifically, like Magnusson et al. (Citation2014, p. 23), “we view a prototypical exemplar as a member of a cognitive category whose attributes strongly resemble or reflect the attributes of the category.” Hence, if a prototypical focal concurrent sponsor is incorporated into a vignette, any captured responses to the focal sponsor are applicable to both entitative and inentitative contexts.

Survey Design

To examine the relationships under investigation, we capture our constructs of interest through the FSD’s survey. Capturing responses once vignettes have “set the scene,” rather than manipulating factors of interest, is commonplace outside of the sponsorship domain but is used in sponsorship research to some degree (e.g., Gross and Wiedmann Citation2015). Our constructs of interest were captured by adapting measures found in the literature (see ). Entitativity was measured as a response to the vignettes, as opposed to manipulated. Purchase intention was measured at the brand level, as opposed to a product level, to ensure vignettes could be collapsed together, if appropriate.

TABLE 1 Items, Factor Loadings, and Error Variances for Study 1 and 2.

STUDY 1

Pretest Stages

The first stage involved choosing prototypical focal concurrent sponsors. Twenty-nine students not involved in the main study were asked to write down as many sponsors as they could think of as part of a 30-second thought-listing task (Barsalou Citation1985). Nike and Adidas were the two sponsors most frequently mentioned (each listed seven times). Following this, 15 different students rated the extent to which both Nike and Adidas were a good example of a sponsor (Barsalou Citation1985), while the other previously generated sponsors acted as fillers. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests suggested Nike and Adidas were not significantly different from each other, nor were they significantly different from the highest-rated filler sponsor, Coca-Cola. The findings support the view that Nike and Adidas are comparable, prototypical sponsors, and can be incorporated into sponsorship vignette methodologies as focal sponsors (see Carrillat and d’Astous Citation2012; Pappu and Cornwell Citation2014).

The second stage involved choosing suitable properties within providers and financers contexts so that a good balance of internal and external validity is likely maintained. Here, we adapted vignettes from Carrillat and d’Astous (Citation2012), who explicitly distinguished between these two sponsorship types. We chose the National Provincial Championship (NPC) and the European Games to be the sponsored properties because, relative to fictitious events, people were expected to have some knowledge of them. This makes the vignettes more realistic and thus “offers a substantial value added in terms of external validity” (Dens and De Pelsmacker Citation2010, p. 187). That said, the two events are not as well-known as events such as the Olympic Games or the soccer World Cup. At the time of data collection, the NPC had recently been superseded by another rugby competition, but this new competition is still colloquially called the NPC; and the European Games had been discussed in the media but had yet to commence. Hence, internal validity is likely to be high.

Finally, each concurrent sponsorship context (i.e., providers/financers) was created by explaining each focal concurrent sponsor (i.e., Nike/Adidas) was one sponsor among “other” unnamed sponsors, in line with Ruth and Simonin (Citation2006). To further concretize the vignettes, respondents were asked to write down up to three “other” sponsors they imagined were involved in each sponsorship type. Finally, to amplify baseline commercial intentions behind the sponsorships, each vignette ended with the focal sponsor’s promotional campaign, following Carrillat and d’Astous (Citation2012).

Data Collection

Pretesting of a vignette pair, and the associated survey-based measures (for the constructs of interest), was carried out via both debriefing with marketing and sponsorship academics, and protocol analysis with university students. Slight adaptations to two entitativity items resulted (see Study 2 for more details).

After protocoling, a pilot study was undertaken using an online FSD, targeting students at a midsized European university. Thirty-seven students were randomly assigned to vignette pair 1 or vignette pair 2 (the counterbalanced version of vignette pair 1), or vignette pair 3 or vignette pair 4 (the counterbalanced version of vignette pair 3) (see ). Mann-Whitney U tests indicated no substantial differences between people’s responses to the named concurrent sponsor or named sponsored property, nor were there any differences in their responses to the survey-based questions that captured our constructs of interest. Meanwhile, all entitativity manifest variables within the (a) collapsed providers and (b) collapsed financers vignettes demonstrated appropriate levels of variance (σ2 ≥ 1.758 in providers and σ2 ≥ 1.603 in financers), as did all other variables of interest. Respondents reported that they believed at least two concurrent sponsors were present in each sponsorship type, indicating the concurrent sponsorship contexts were successfully implemented.

Main Study

Two further vignette pairs were created, and the order of each vignette within a pair was also reversed. This culminated in eight vignette pairs possibilities in total to which respondents were randomly assigned (see ). Random assignment ensured that each vignette pair was read by respondents who were, on average, equally knowledgeable and familiar with the respective properties and sponsors, equally likely to view the properties, and equally likely to purchase from a concurrent sponsor outside of the specific research context. It should be noted that a vignette fraction (i.e., a portion of the total vignette population) was deliberately exploited. Vignette fractions are advantageous in FSD applications (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010). Specifically, the fractional element allows researchers to present only meaningful and plausible vignettes without negatively impacting upon answering the research question(s) at hand. Conversely, using a full vignette population may lead to “imperfect” vignettes, which could produce suspicious, unpredictable, and/or context-specific responses. For example, we incorporated an “A1” rugby ball into some of our vignettes, following Carrillat and d’Astous (Citation2012). A rugby ball is a relevant product to supply when a sponsor is a provider of a rugby event such as the NPC, and/or is an appropriate product to promote for both providers and financers. However, from a research design perspective, a rugby ball is an inappropriate product to supply and/or promote when the event is a multisport event, such as the European Games, given that rugby is only one of many sports. Hence, any rugby-associated sponsorship and/or promotion may be considered to be lower-tiered.Footnote1 Meanwhile, evidence suggests tiered sponsorships affect subsequent sponsorship evaluations (e.g., Groza, Cobbs, and Schaefers Citation2012). Importantly, deliberately omitting such vignettes does not affect the interpretation of a study’s findings (e.g., Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010).

Data collection procedures for the main study followed an identical approach to the pilot study. Response rate enhancement techniques included the auspice of the university and a prize draw. Due to the sampling frame being a sample of university-owned electronic mailing lists, which are administered by third parties, response rate calculations were not possible. That said, 334 respondents completed the questionnaire.

Bias Testing

Only those students who were born and had lived for the majority of their lives in the European country where the university is based were considered for analysis, as literature suggests different cultures regard entitativity (Spencer-Rodgers, Williams, et al. Citation2007) and sponsorship contexts (e.g., Mazodier and Rezaee Citation2013) differently. This reduced the sample size to 272 completed responses. To ensure the remaining sample had considered a concurrent sponsorship context, respondents who indicated only one sponsor was involved in either sponsorship context were removed from the analysis. This left an adequate number of eligible responses (N = 263; 46.4% female; mean age = 21.7; mean length of time respondents had lived in the country as a percentage of age = 97.3%).

To test for potential significant differences between vignette responses, Kruskal-Wallis tests on the respective manifest variables were performed, and no causes for concern were raised. Consequently, (a) all providers scenarios and (b) all financers scenarios were collapsed together allowing the study’s constructs of interest to be analyzed across all respondents, for each sponsorship type separately. Here, appropriate levels of entitativity variance were found in the providers (σ2 = 1.175) and financers (σ2 = 1.369) vignettes, as well as the other measured items.

Data were analyzed using a two-stage, covariance structure modeling approach in Lisrel 8.71. Standard theory-trimming confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) procedures revealed the retained manifest variables’ factor loadings exceeded .70 (see ), indicating the items represented the latent variables well. The CFA model also fit the data well for both sponsorship types (see ).

TABLE 2 Fit Measures for Study 1 and Study 2.

All AVEs and construct reliabilities were within acceptable ranges. The lowest was also higher than the largest correlation between constructs for both providers and financers. Hence, discriminant validity between the FSD constructs in both sponsorship types is upheld (see Voorhees et al. Citation2016) (see ). Note that fit between the prototypical focal concurrent sponsor and event was not measured so that people’s attention was not directed toward examining dyadic sponsorship relationships. That said, prototypical sponsors like “Adidas makes perfect sense to consumers because they can easily understand why Adidas would sponsor a sporting event” (Pappu and Cornwell Citation2014, p. 490). Hence, Adidas/Nike has a uniformly high natural fit. Moreover, involvement with sporting events in general was measured, and this is positively associated with fit in previous studies. Fit is also a driver of people’s attitude toward the sponsorship (e.g., Olson Citation2010), which was measured and controlled for.

TABLE 3a Providers—Study 1.

In terms of procedural remedies for common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003), we reduced respondents’ potential evaluation apprehension by (a) protecting anonymity and confidentiality (which also enhances response rates) and (b) assuring respondents that there were no right or wrong answers. We also used established procedures to develop the measures of all constructs. In terms of statistical procedures, we performed Harman’s single-factor test. No single factor was uncovered. We next performed an unmeasured common method factor test. The highest partitioned variance accounted for by the method factor was only 3.6%, which is substantially lower than the 25% threshold value (e.g., see Chughtai, Byrne, and Flood Citation2015). The method factor also failed to alter substantive relationships. Hence, CMV is not an issue.

Study 1 Results and Discussion

To test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed, using the residual-centered multiplicative approach to calculate interaction terms. All SEM indicators are within the accepted thresholds for both providers and financers. Measures are presented alongside CFA results in .

Providers Results

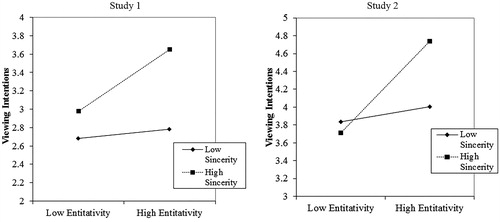

The model explains 20.7% of the variance in viewing intention and 30.5% of that in purchase intention in providers. Most relationships predicted in the conceptual model are significant, as are many controls (see ). Specifically, entitativity is positively related to viewing intention (γ = .193, p = .002), in support of hypothesis 1. A direct relationship between sponsor sincerity and viewing intention is significant (γ = .293, p < .001), as is the interaction between sponsor sincerity and entitativity on viewing intention (γ = .143, p = .022) (see ). The latter finding supports hypothesis 2.

TABLE 3b Financers—Study 1.

TABLE 4 Structural Model Results for Study 1 and 2.

TABLE 5a Providers—Study 2.

Table 5b Financers—Study 2.

However, attitude toward the providers sponsorship is not significantly related to viewing intention (γ = −.040, p > .10), nor does it affect the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention (γ = .035, p > .10). Hence hypothesis 4 is not supported. Viewing intention is positively associated with purchase intention (β = .205, p < .001), in support of hypothesis 5. Post hoc examination of the modification indices also indicates a significant and positive relationship between attitude toward the providers sponsorship and purchase intention (γ = .244, p < .001). Finally, to investigate whether viewing intention mediates the relationship between entitativity and purchase intention, a direct path from entitativity to purchase intention was included. The direct path was nonsignificant, whereas the two mediating paths remained significant. Thus, a Sobel test was undertaken on the unstandardized a and b parameters. The test statistic was significant (z = 2.32, SE = .03, p = .010, one-tailed), suggesting indirect-only mediation (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

Financers Results

The model explains 22.2% of the variance of viewing intention and 29.4% of that in purchase intention in financers. Entitativity is positively related to viewing intention (γ = .329, p < .001), supporting hypothesis 1. However, neither concurrent sponsor sincerity (γ = .074, p > .10) nor attitude toward the financers sponsorship (γ = −.004, p > .10) significantly affects the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention. Thus, hypotheses 2 and 4 are not supported. Moreover, the direct effects of sincerity (p = .059) and attitude toward the financers sponsorship (p > .10) do not reach significance. Meanwhile, viewing intention is positively related to purchase intention (β = .125, p = .016), supporting hypothesis 5. Many of the controls are also statistically nonsignificant. A post hoc examination of the modification indices suggests people’s attitude toward the financers’ sponsorship and their purchase intention is linked. Finally, when a direct path between entitativity and purchase intention is included, the two mediating paths remain significant, while the direct path is nonsignificant. The significant Sobel test statistic (z = 1.87, SE = .03, p = .03, one-tailed) suggests indirect-only mediation (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

Comparison

Hypothesis 3 was tested following Banerjee, Iyer, and Kashyap (Citation2003) and Lent et al. (Citation2008). First, we accounted for measurement error by creating single items for all constructs and fixing each construct’s respective error variance using Jöreskog and Sörbom’s (Citation1993) formula. We then estimated a multigroup path model where all paths into viewing intention from (a) entitativity, (b) sincerity, and (c) entitativity × sincerity in the providers model were restricted to equal their equivalent path in the financers model. Next, we allowed the three paths involved in the interaction between entitativity and sincerity on viewing intention to vary freely across models and examined the ΔCFI. Path invariance is accepted if ΔCFI ≤ .01 (Lent et al. Citation2008). The CFI indicator increased by .001, suggesting the ΔCFI is in the hypothesized direction, but not significantly. Hence, hypothesis 3 is not supported statistically.

STUDY 2

Methodology

Study 1 provided preliminary support for the conceptual model. For the purposes of robustness testing, a second quantitative study was undertaken. Again, people from the same European country completed the study. This time, respondents were presented with a specific number of concurrent sponsors, which allowed for different sponsor–property congruences (fits) to be controlled for. Also, we adjusted the entitativity items: The two items removed during CFA theory-trimming procedures in study 1 were reintroduced, because testing for “the same relationships among the same constructs as an earlier study but varying the operationalization of those constructs” (Barrick et al. Citation2007, p. 545) is a constructive replication. Hence, a second study, which finds similar relationships with somewhat differing manifest variables and utilizes a dissimilar sample, advances theory.

Specifically, respondents were informed that three concurrent sponsors were involved. Hence, alongside the named prototypical concurrent sponsor, respondents were also required to provide two other concurrent sponsors they imagined were involved in each sponsorship type. Respondents chose their own “other” sponsors to make each sponsorship context individually relevant. In addition, respondents’ answers to the two “other” concurrent sponsors were incorporated (“piped”) into the FSD to capture different sponsor–property fits, using Speed and Thompson’s (Citation2000) fit scale.

A total of 277 consumers were randomly recruited from multiple market research panels through Qualtrics. After removing those who were not born in or had not lived in the European country for the majority of their lives, as well as responses that indicated a focal concurrent sponsor of one vignette could be an “other” concurrent sponsor in the second vignette, usable responses from 255 consumers were retained (49.4% female; mean age = 40.5; mean length of time respondents had lived in the country as a percentage of age = 91.5%).

Study 2 Results and Discussion

Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to assess bias, and no causes for concern were found. Hence, (a) all providers and (b) all financers vignettes were collapsed together. Again, appropriate levels of entitativity variance were found in the providers (σ2 = 1.549) and financers (σ2 = 1.618) vignettes, as well as the other measured constructs. Meanwhile, CFA and SEM results for both sponsorship types indicate the model fits the data well (see ). Construct reliabilities and discriminant validity also exceeded minimum thresholds (Voorhees et al. Citation2016) (see ). Finally, a social desirability common method factor test found nonsignificant Δχ2 statistics, suggesting CMV is of little concern.

Providers Results

The model explains 68.5% of the variance of viewing intention and 60.0% of that in purchase intention in providers. Entitativity is positively associated with viewing intention (γ = .299, p < .001), supporting hypothesis 1. This relationship is strengthened when sponsor sincerity increases (γ = .215, p = .048), supporting hypothesis 2. Once more, people’s attitude toward providers sponsorship does not affect the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention (γ = −.166, p = .100), although it does have a direct effect on viewing intention (γ = .344, p < .001). Therefore, as in Study 1, hypothesis 4 is not supported. Finally, viewing intention is positively associated with purchase intention (β = .360, p < .001), supporting hypothesis 5. A post hoc examination of the modification indices indicates no additional paths should be created/removed. Finally, the inclusion of a direct path from entitativity to purchase intention is nonsignificant, while the two mediating paths remain significant and positive. The Sobel test statistic is significant (z = 3.72, SE = .04, p < .001, one-tailed), indicating indirect-only mediation (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

Financers Results

The model explains 65.0% of the variance in viewing intention and 59.4% of that in purchase intention. Entitativity is positively associated with viewing intention (γ = .137, p = .043), supporting hypothesis 1. Sincerity’s direct effect (p = .055) on viewing intention does not reach significance, while the direct effect of attitude toward the financers sponsorship does (p < .001). However, and as found in Study 1, the relationship between entitativity and viewing intention is affected neither by sincerity (γ = −.007, p > .10) nor by people’s attitude toward financers sponsorship (γ = .010, p > .10). Hence, neither hypothesis 2 nor hypothesis 4 is supported. Viewing intention is positively associated with purchase intention (β = .288, p < .001), supporting hypothesis 5. A post hoc examination of the modification indices also suggests no additional paths should be created/removed. When a direct path from entitativity to purchase intention is created, the two mediating paths remain significant, whereas the direct path is nonsignificant. The Sobel test statistic is marginally significant (z = 1.576, SE = .03, p < .06, one-tailed), indicating indirect-only mediation (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

Comparison

Multigroup path analysis resulted in ΔCFI < .001, suggesting the interaction between entitativity and sincerity on viewing intention is not significantly stronger for providers than it is for financers. Hence, hypothesis 3 is not supported statistically. Individual path results for both sponsorship contexts are seen in and , while the entitativity–sincerity interaction graphs for providers are found in .

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Overall, the main effects examined are replicated across both studies, appearing robust, replicable, and generalizable to different audiences in the country studied. We therefore conclude with some confidence that entitativity is significantly and positively related to intentions to view the property (hypothesis 1), and the latter with intentions to purchase from the sponsor (hypothesis 5). With regard to the first moderator path (sincerity), it was found to differ across sponsorship types. Specifically, while we expected concurrent sponsor sincerity to strengthen the relationship between entitativity and viewing intentions for both providers and financers (hypothesis 2), this was supported only in providers contexts. It therefore appears that consumers perceive providers’ products/services as further enhancing the property quality when entitative providers are property-serving, owing to these sponsors’ instrumental and complementary relationships with properties’ performances (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014; Pope, Voges, and Brown Citation2009). By contrast, the perceived benefits properties accrue from having entitative financers may primarily arise from increased intentionality, responsibility, and image-based inferences. One explanation for the nonsignificant interaction between entitativity and sincerity in financers contexts could be due to increased commercial intentionality (as entitativity increases) being associated with increased financial investment. That is, audiences may assume that a greater pot of sponsorship money is directed toward properties as entitativity increases, which, in turn, may lead them to believe properties are worthier of following (i.e., they are bigger, better, and more exciting events). Subsequently, properties benefit substantially more from perceptions of increased financial investment than from perceptions of a lack of property detraction (i.e., entitative financers’ sincerity).

That said, the interaction between entitativity and sincerity is not significantly stronger for providers than for financers (with hypothesis 3 unsupported in both studies). Thus, while there is replicated evidence (across the two studies) that the entitativity–sincerity interaction affects viewing intentions in providers but not in financers contexts, the lack of support for hypothesis 3 may signal that the differences between contexts are, in fact, rather nuanced.

Finally, people’s attitude toward the sponsorship does not appear to strengthen the entitativity–viewing intentions relationship (with hypothesis 4 unsupported in both studies). This suggests that when audiences perceive sponsors as increasingly entitative, they become keener to follow the property, irrespective of whether their attitude toward the sponsorship arrangement is positive or negative. In some ways, this strengthens our arguments pertaining to the entitativity–viewing intentions relationship. Specifically, as entitativity increases, the enhanced commercial intentions and responsibilities sponsors are perceived to have signal a higher-quality property. Audiences enjoy attending a more exciting event even if they are not so keen on sponsors exploiting it. This is not to say that attitude toward the sponsorship is not important. Indeed, the results of Study 2 show statistically significant direct paths into viewing intentions for both providers and financers. Consequently, it may be that other event-related factors must be more salient before a statistically significant interaction between entitativity and attitude toward sponsorship can be found. For example, if ambush marketers are involved in leveraging a property they do not officially sponsor, audience goodwill may fall on the side of sponsors they may otherwise be more suspicious of (see Mazodier, Quester, and Chandon Citation2012). Meanwhile, ambush marketing is only commercially viable when properties are popular, so people should also perceive a property to be of higher quality when ambush marketers leverage it. In this context, we may see a significant impact of attitude toward sponsorship on the entitativity–viewing intentions relationship, due to attitudes being heightened by ambush marketers.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time a relationship between concurrent sponsors’ entitativity and viewing intention has been identified. The evidence suggests this relationship exists, at least in part, because of people’s perceptions of a property that is sponsored. Thus, when sponsors’ finances or products/services are utilized by properties, intentionality and collective responsibility are likely ascribed to the sponsors (although collective responsibility is likely to be at a lower degree for financers than providers, given their lesser degree of direct involvement). The intentionality and collective responsibility people attribute to entitative sponsors signals greater professionalism and/or a higher-quality property, and subsequently viewing intentions increase.

Theoretical and Management Implications

This article has a number of significant theoretical implications. First, it adds to the scant literature on entitativity in the sponsorship domain. In particular, we link entitativity to viewing intentions toward properties and ultimately toward concurrent sponsors. Specifically, we find entitativity drives viewing intention toward the property and, ultimately, purchase intention toward a concurrent sponsor. So, our focus on the behavioral aspects of entitativity contributes to a literature stream that typically examines relationships with image transfer (Carrillat, Solomon, and d’Astous Citation2015). We also tease out providers from financers through a research design that is rarely, if ever, utilized in sponsorship research.

In terms of management implications, the results suggest both property rights holders and sponsors should encourage audiences to perceive concurrent sponsors as being grouplike, as this will lead to an increased following and greater purchase intention. Entitativity is a perception. Hence, concurrent sponsors may be able to manipulate situations so as to appear grouplike. For example, Nike/Adidas and the other concurrent sponsors could highlight their groupness by utilizing signage with similar colors or by copromoting the property. Executing such strategies not only would be a rather distinctive approach—at least in the near future—but also should lead to increased perceptions of intentionality (see O’Laughlin and Malle Citation2002). Providers could also cross-promote what each concurrent sponsor brings to the table to make the property what it is on the day of the event and how each sponsor’s complementary resources improve the overall functional performance of the sponsored property (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014). To some extent, this approach is already adopted on an individual sponsor basis. For example, consider the advertising promotions that state “Mac Tools has the products to help” Kalitta Motorsports win (CitationMac Tools n.d.), and that DHL supports Kalitta Motorsports’ “race behind the race” (CitationDHL n.d.). Yet beyond the two sponsors’ logos adjacently appearing on Kalitta Motorsports’ website, no communication is found pertaining to how both providers together contribute to Kalitta Motorsports’ overall performance. Similarly, financers could cross-promote their similar images (with both the property and each other), alongside how their financing enables a sponsored property to exist or flourish. For example, Cathay Pacific Airways copromoted HSBC when it announced the cotitle sponsorship of the Hong Kong Sevens. As John Slosar, chief executive of Cathay Pacific, commented at the time: “Backed by the power of Hong Kong’s two biggest international brands I believe we’ll see the Hong Kong Sevens soar to new heights” (Cathay Pacific Citation2011). In many ways, financers’ cocommunications, such as those by Cathay Pacific, are much easier to coordinate than providers’ cocommunications. That said, communicating concurrent sponsor entitativity messages in general should be cheaper than committing resources to becoming an actual sponsorship group.

It is also important that opportunities are created to communicate entitative concurrent sponsors’ sincerity for providers if viewing intentions are to be further enhanced, and subsequently purchase intention increased. This requires people perceiving entitative concurrent sponsors as genuinely serving the property, rather than being wholly self-serving. On one hand, this may discourage brands from sponsoring. For example, people often associate “big brands” with “big properties” (Wakefield and Bennett Citation2010), and so the creation of sincere communications may lead to perceptions that a sponsor is not as “big” as it actually is, if it is sponsoring a property which needs support. Perceptions of market leadership and market prominence can be important heuristics for people when they judge sponsors’ products and services. Therefore, a potential perceived inability, arising from attempts to appear sincere, to sponsor the biggest and best properties—those which do not need sponsorship but can attract it—may reduce companies’ abilities to leverage these heuristic effects. On the other hand, sponsorship is strategically returning to its original philanthropic-based values. In particular, companies are using sponsorship in a more strategic manner, going beyond simple short-term transactional and commercial use. The current environment should therefore allow entitative sponsors to be perceived as having the intentionality to act in properties’ best interests, in the case of providers in particular.

Limitations and Further Research

Our vignettes used high-fitting, prototypical focal concurrent sponsors. Future research should consider investigating less prototypical sponsors, as well as giving greater emphasis to other sponsors. Our vignettes were also text based. While this controls for audio- or color-induced effects, future research may consider audio and/or visual vignettes to enhance ecological validity. Similarly, our vignettes informed consumers that providers do not invest money when sponsoring. Consumers invariantly perceive this, but from an organizational perspective providers likely supplement their product/services with cash. Hence, future research should adapt the vignettes if respondents come from organizations.

We also focused on the relationship between entitativity and behavioral intentions, and built our hypotheses accordingly. Future research may wish to consider the hypothesized mediating relationships in a more fine-grained fashion. Likewise, the extent to which properties’ and sponsors’ brand images are affected by different concurrent sponsorship contexts, and by (in)entitativity within these contexts, is worthy of further investigation. For example, financers may not be intertwined with a property in form and function (Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014), but their images may be. Thus, image spillovers to/from a property may increase as entitativity rises. Conversely, image spillovers may be less prevalent for providers due to the functional nature of these relationships (see Newmeyer, Venkatesh, and Chatterjee Citation2014; Spencer-Rodgers, Hamilton, and Sherman Citation2007). Finally, regarding entitativity’s operationalization, a note of caution should be placed on the lead-in phrase to introduce items. We asked respondents to describe “this group of event sponsors.” Our preliminary tests revealed that, in everyday language, the word group is attributed to aggregates of varying entitativity levels, and therefore is appropriate to describe concurrent sponsors across entitativity’s continuum. In addition, entitativity’s constructs’ means and variances were within the norm for both studies (3.690 ≤ ≤ 4.472, 1.175 ≤ σ2 ≤ 1.618). Nevertheless, it is possible that the word group may bias future respondents.

This article leads to a number of research directions. For example, when concurrent sponsors finance a property, it appears sincerity is less important. Hence, future studies should explore why the interaction between entitativity and sincerity in financers does not significantly affect viewing intention. Perhaps consumers perceive that financers have less-altruistic intentions, given altruism and sincerity are closely linked (see Olson Citation2010). Relatedly, people may infer financers have more commercial intent behind their sponsorships. Conversely, future research may investigate other subtle differences between the two sponsorship types, such as perceptions that entitative providers invest more managerial cognition, human capital, and time than do entitative financers.

Finally, examining how the three broad categories of entitativity’s antecedents—chronic perceiver differences, (perceived) contextual factors, and (perceived) group properties (see Lickel et al. Citation2000)—specifically affect entitativity in concurrent sponsorships is important. Understanding which antecedents are key to high/low entitativity for providers and for financers is valuable to both researchers and practitioners. Similarly, understanding how specific entitativity antecedents interact with entitativity itself should be investigated. For instance, concurrent sponsors are unlikely to be homogenous, due to product category exclusive clauses. Homogeneity is one of entitativity’s antecedents (e.g., Spencer-Rodgers, Hamilton, and Sherman Citation2007) and purported to affect consumers (e.g., Pappu and Cornwell Citation2014). Given that this article’s findings suggest that entitativity also affects consumers, an examination of how homogeneity drives entitativity, as well as how it affects entitativity’s outcomes, is warranted.

NOTE

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The sports included in the European Games were still being discussed at the time of data collection. When the Games commenced, rugby did not feature. This situation further illustrates how an implausible and suspicious vignette would be created if a rugby product was associated with the European Games.

REFERENCES

- Aguinis, Herman, and Kyle J. Bradley (2014), “Best Practice Recommendations for Designing and Implementing Experimental Vignette Methodology Studies,” Organizational Research Methods, 17 (4), 351–71.

- Atzmüller, Christiane, and Peter M. Steiner (2010), “Experimental Vignette Studies in Survey Research,” Methodology, 6 (3), 128–38.

- Auspurg, Katrin, and Thomas Hinz (2015), Factorial Survey Experiments, Los Angeles: Sage.

- Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby, Easwar S. Iyer, and Rajiv K. Kashyap (2003), “Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type,” Journal of Marketing, 67 (2), 106–22.

- Barrick, Murray R., Bret H. Bradley, Amy L. Kristof-Brown, and Amy E. Colbert (2007), “The Moderating Role of Top Management Team Interdependence: Implications for Real Teams and Working Groups,” Academy of Management Journal, 50 (3), 544–57.

- Barsalou, Lawrence W. (1985), “Ideals, Central Tendency, and Frequency of Instantiation As Determinants of Graded Structure in Categories,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11 (4), 629–54.

- Carrillat, François A., and Alain d’Astous (2012), “The Sponsorship-Advertising Interface: Is Less Better for Sponsors?,” European Journal of Marketing, 46 (3/4), 562–74.

- Carrillat, François A., and Alain d’Astous (2014), “Sponsorship,” Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, Vol. 9, C. L. Cooper, ed., Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley, 1–7.

- Carrillat, François A., Eric G. Harris, and Barbara A. Lafferty (2010), “Fortuitous Brand Image Transfer,” Journal of Advertising, 39 (2), 109–23.

- Carrillat, François A., Paul J. Solomon, and Alain d’Astous (2015), “Brand Stereotyping and Image Transfer in Concurrent Sponsorships,” Journal of Advertising, 44 (4), 1–15.

- Cathay Pacific (2011), “Cathay Pacific and HSBC resume co-title sponsorship of the Hong Kong Sevens for first time since 1997,” May 18, https://www.cathaypacific.com/cx/en_VN/about-us/press-room/press-release/2011/cathay-pacific-and-hsbc-resume-co-title-sponsorship-of-the-hong-kong-sevens-for-first-time-since-1997.html.

- Chien, P. Monica, T. Bettina Cornwell, and Ravi Pappu (2011), “Sponsorship Portfolio as a Brand-Image Creation Strategy,” Journal of Business Research, 64 (2), 142–49.

- Chughtai, Aamir, Marann Byrne, and Barbara Flood (2015), “Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Well-Being: The Role of Trust in Supervisor,” Journal of Business Ethics, 128 (3), 653–63.

- Cobbs, Joe, David Tyler, Jonathan A. Jensen, and Kwong Chan (2017), “Prioritizing Sponsorship Resources in Formula One Racing: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Journal of Sport Management, 31 (1), 96–110.

- Cobbs, Joe, Mark D. Groza, and Gregg Rich (2015), “Brand Spillover Effects within a Sponsor Portfolio: The Interaction of Image Congruence and Portfolio Size,” Marketing Management Journal, 25 (2), 107–22.

- Colquitt, Jason A., and Cindy P. Zapata-Phelan (2007), “Trends in Theory Building and Theory Testing: A Five-Decade Study of the Academy of Management Journal” Academy of Management Journal, 50 (6), 1281–1303.

- Connelly, Brian L., S. Trevis Certo, R. Duane Ireland, and Christopher R. Reutzel (2011), “Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment,” Journal of Management, 37 (1), 39–67.

- Crawford, Matthew T., Steven J. Sherman, and David L. Hamilton (2002), “Perceived Entitativity, Stereotype Formation, and the Interchangeability of Group Members,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (5), 1076–94.

- Crompton, John L. (2014), “Potential Negative Outcomes from Sponsorship for a Sport Property,” Managing Leisure, 19 (6), 420–41.

- Deitz, George D., Susan W. Myers, and Marla R. Stafford (2012), “Understanding Consumer Response to Sponsorship Information: A Resource‐Matching Approach,” Psychology and Marketing, 29 (4), 226–39.

- Delpy, Lisa, Marty Grabijas, and Andrew Stefanovich (1998), “Sport Tourism and Corporate Sponsorship: A Winning Combination,” Journal of Vacation Marketing, 4 (1), 91–102.

- Dens, Nathalie, and Patrick De Pelsmacker (2010), “Advertising for Extensions: Moderating Effects of Extension Type, Advertising Strategy, and Product Category Involvement on Extension Evaluation,” Marketing Letters, 21 (2), 175–89.

- DHL (n.d.), DHL Motorsports, http://www.dhl.com/en/about_us/partnerships/motorsports.html.

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, Marc Herz, Nicole Koschate-Fischer (2017), “The EU As Superordinate Brand Origin: An Entitativity Perspective,” International Marketing Review, 34 (2), 183–205.

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa (1986), “Perceived organizational support,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (3), 500–07.

- Feloni, Richard (2014), “How Sponsors Saved Three of This Weekend’s Four NFL Playoff Games from Not Being Locally Televised,” SFGATE, January 3, http://www.sfgate.com/technology/businessinsider/article/How-Sponsors-Saved-Three-Of-This-Weekend-s-Four-5112358.php.

- Folkes, Valerie S., and Michael A. Kamins (1999), “Effects of Information about Firms’ Ethical and Unethical Actions on Consumers’ Attitudes,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 8 (3), 243–59.

- Gross, Philip, and Klaus‐Peter Wiedmann (2015), “The Vigor of a Disregarded Ally in Sponsorship: Brand Image Transfer Effects Arising from a Cosponsor,” Psychology and Marketing, 32 (11), 1079–97.

- Groza, Mark D., Joe Cobbs, and Tobias Schaefers (2012), “Managing a Sponsored Brand: The Importance of Sponsorship Portfolio Congruence,” International Journal of Advertising, 31 (1), 63–84.

- Gwinner, Kevin, and Gregg Bennett (2008), “The Impact of Brand Cohesiveness and Sport Identification on Brand Fit in a Sponsorship Context,” Journal of Sport Management, 22 (4), 410–26.

- Hamilton, David L., and Sherman Steven J. (1996), “Perceiving Persons and Groups,” Psychological Review, 103 (2), 336–55.

- Hamilton, David L., Steven J. Sherman and Brian Lickel (1998), “Perceiving Social Groups: The Importance of the Entitativity Continuum,” in Intergroup Cognition and Intergroup Behavior, C. Sedikide, J. Schopler, and C.A. Insko, eds., Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 47–74.

- Henderson, Conor M., Joshua T. Beck, and Robert W. Palmatier (2011), “Review of the Theoretical Underpinnings of Loyalty Programs,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21 (3), 256–76.

- Henseler, Jöxrg, Bradley Wilson, and Dorien De Vreede (2009), “Can Sponsorships Be Harmful for Events? Investigating the Transfer of Associations from Sponsors to Events,” International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 10 (3), 244–51.