?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Advergames are generally believed to be an effective advertising format due to their gamified and engaging nature. The empirical evidence for this, however, is inconclusive, with several studies reporting nonsignificant or contradicting results. The current study aimed to address this research gap by providing a meta-analysis of five advergame effects (i.e., ad attitude, memory, persuasion, choice behavior, persuasion knowledge). A systematic search procedure was used and 38 relevant data sets were identified. The results indicate that, generally, (1) consumers have a more positive attitude toward advergames than other types of advertising; (2) brand and product information seems less likely to be remembered by consumers when it is communicated via an advergame versus different types of advertising; (3) advergames seem to be persuasive and (4) drivers of choice behavior; and (5) compared to other types of advertising, advergames are less likely to be recognized as advertising; finally, a metaregression model showed that (6) consumers’ age mitigates the persuasiveness of advergames, meaning that younger consumers seem more susceptible to the persuasive effect of advergames than older consumers are.

Gamification, the use of game thinking and game mechanics to solve problems and influence real-world behaviors, is more popular than ever. In less than a decade, this practice evolved into a multibillion-dollar industry (TechSci Research Citation2019). Among the first to adopt gamification principles were advertisers and brands who use it to enhance the effectiveness of their advertising messages (Terlutter and Capella Citation2013). Today, the commercial use of gamified advertising is widespread, and forecasts indicate that its popularity is continually increasing. Technavio (Citation2020) recently projected that, despite uncertainties concerning the global economy, the gamified advertising market will continue to grow by about 20% annually over the next five years—by almost $11 billion total. In this article, we focus on one of the more popular types of gamified advertising: the advergame.

Advergames are fully gamified advertising messages and can be defined as a type of advertising that leverages game thinking and game mechanics to drive engagement with a brand—to ultimately reach a commercial goal. In their seminal publication on the gamification of advertising, Terlutter and Capella (Citation2013) laid the groundwork for the scientific exploration of advergames. They identified various important psychological and behavioral outcomes of advergaming. In the current study, we aim to expand on their work by utilizing meta-analytical methods to systematically quantify five of these advergame effects: ad attitude, memory, persuasion, choice behavior, and persuasion knowledge activation. This quantification attempt is essential because the empirical evidence for the effectiveness of advergames remains inconclusive.

For the most studied effect of advergaming, persuasion, we also examine the moderating role of age. Including age as a moderating variable offers a unique opportunity to test whether age influences people’s susceptibility to advergames—in other words, whether young consumers are potentially more susceptible to advergames than are their adult counterparts. Mizerski et al. (Citation2017) recently pointed out that the empirical evidence for the often-assumed link between this age-dependent susceptibility to persuasion and actual brand responses remains inconclusive, despite a heavy focus on children’s responses to advergames.

In sum, with our study, we expect to contribute to the overall understanding of advergaming in two distinct ways. First, building on the work of Terlutter and Capella (Citation2013), this work contributes to the advertising literature by offering meta-analytical estimates of advergame effects. Considering the inconclusive findings across studies, these estimates will be relevant both for researchers studying the effectiveness of advergames and for practitioners who use advergames to reach their commercial goals. Second, by including age as a potential moderator of advergame persuasiveness, we hope to contribute to the overall understanding of age-dependent susceptibility to persuasion and actual brand responses.

Theoretical Background

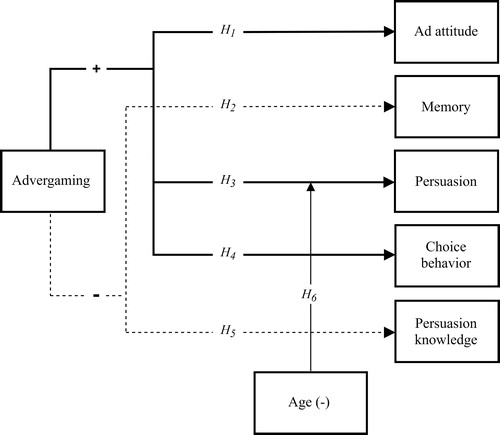

To visualize the structure of our article, we have included a conceptual model in . This figure shows that we first discuss the hypotheses for the five psychological and behavioral outcomes of advergaming: ad attitude (hypothesis 1), memory (hypothesis 2), persuasion (hypothesis 3), choice behavior (hypothesis 4), and persuasion knowledge activation (hypothesis 5). Following those discussions, we examine the potential moderating role of age in the persuasiveness of advergames (hypothesis 6).

Figure 1. Our conceptual model: The predicted positive effects are indicated with solid, bold lines and predicted negative effects with dotted lines.

Do Consumers Have Positive Attitudes toward Advergames?

Due to their gamified nature, advergames are generally believed to be more engaging than nongamified advertising. It is unclear, with empirical evidence being inconclusive, whether consumers actually like advergames more so than other types of advertising. This is most clearly exemplified by considering two recent studies (i.e., Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy Citation2019; Waiguny, Nelson, and Terlutter Citation2014) that reported opposing results. Where Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy (Citation2019) found that their participants liked the advergames they played less than the video commercials they watched, Waiguny, Nelson, and Terlutter’s (Citation2014) study showed the opposite and reported more positive attitudes toward their stimulus advergame than toward their stimulus video.

In general, most people are believed to be critical of advertising and thus express negative or ambivalent attitudes toward advertising (Obermiller and Spangenberg Citation2000). These often-negative attitudes are believed to be driven, for the most part, by consumers’ general skeptical beliefs toward advertising. However, other beliefs have also been found to play a key role in the formation of attitudes toward specific types of advertising. For gamified advertising in particular, perceived hedonic value has been identified as an important belief driving positive ad attitudes (Poels, Janssens, and Herrewijn Citation2013).

Gamified advertising differs from nongamified advertising in that it utilizes game mechanics and game thinking to engage consumers with its advertised message. Gamifying content aims to make engaging with this particular content more enjoyable (Altmeyer et al. Citation2019) and thus likely increases the content’s overall hedonic value. In the context of advergames, this means that by gamifying an advertising message, the hedonic value of the advertised message would likely increase, which subsequently would result in more positive attitudes toward this type of advertising. In sum, we therefore expect that consumers have a more positive attitude toward advergames than toward other types of advertising.

H1: Advergames have a more positive effect on ad attitude compared to nongamified advertising.

Do Advergames Improve Retrieval of Commercial Information from Memory?

Although the gamified nature of advergames is generally considered its strength, it seems likely that there are situations in which it might become its weakness. Most empirical evidence on the effects of advergaming on memory suggests that consumers are less likely to remember commercial information (e.g., brand logos) when this information is embedded in an advergame than when it is embedded in a different advertising format (e.g., Daems, De Pelsmacker, and Moons Citation2019; Huh et al. Citation2015).

These findings can largely be explained within the paradigm of the limited capacity model of motivated mediated message processing (Lang Citation2000). In short, this model suggests that people’s cognitive capacity is limited and that the number of cognitive tasks an individual can perform at the same time requires (and competes for) this finite capacity. For example, to recall a brand after being exposed to it in an advertisement, one must first have allocated cognitive capacity to the processing (i.e., encoding and storing) of this brand information while being exposed to it. If no cognitive capacity is allocated to the processing of the information, perhaps because the viewer was distracted, the information cannot be recalled afterward.

For people playing advergames, this means that to remember any embedded brand information, players will have to allocate cognitive capacity to the encoding and storing of this information while playing. Under the assumption of limited cognitive capacity, this could be problematic, because playing a game often requires a constant (and reactive) allocation of cognitive capacity (Lee and Faber Citation2007). For advergames, this means concretely that the game mechanics (which are a fundamental part of what constitutes an advergame) are expected to direct players’ attention (and allocation of cognitive capacity) away from the embedded commercial information whenever this information is not an integral part of the gameplay.

Ultimately, the gamification of advertising is thus expected to negatively affect players’ processing of the advertising message, which would be reflected by limited retrieval of commercial information from memory for people playing advergames.

H2: Advergames have a less positive effect on brand memory compared to nongamified advertising.

Are Advergames Persuasive?

Advergames are considered particularly persuasive because, more than most other types of advertising, they are able to engage consumers with their commercial content. In this study, the term persuasion is used when discussing an integrated advertising effect representing both affective (e.g., brand attitude) and conative (e.g., purchase intention) responses to advertising. In meta-analyses, integrating affective and conative advertising effects is common practice and is warranted because these effects are often comparable in direction and, to a certain extent, in size (Eisend and Tarrahi Citation2016). Examples of meta-analyses that take the same approach are Eisend and Hermann (Citation2019), O’Keefe (Citation2013), and Jeong and Hwang (Citation2016). While ad attitude is sometimes also included as a component of persuasion, in the current study we decided to treat ad attitude as a separate outcome variable. This decision enabled us to account for the entertaining nature of advergames as a type of advertising.

In the literature, the persuasiveness of advergames has been explained from various theoretical angles. A widely accepted explanation of the persuasiveness of advergames is rooted in their entertaining and emotionally stimulating design. Emotional responses elicited while playing advergames are believed to transfer over to the embedded advertising cues, which in turn would explain the persuasiveness of advergames. These emotional responses are often defined on the dimensions pleasure and arousal, where pleasure indicates the valence of an emotional response and arousal indicates its intensity (Russell and Barrett Citation1999). Both dimensions have been linked to increased persuasion in studies into entertaining advertising formats (like advergames). But the effect of each dimension is explained by a conceptually similar yet unique psychological mechanism.

First, pleasure is believed to drive affective psychological responses (e.g., brand attitude) via direct affect transfer (Mitchell and Nelson Citation2018). This psychological mechanism explains how people attribute positive affect that they experience in a particular context to a stimulus that is embedded within this context. In the context of advergames, it would suggest that people attribute the positive affect experienced while playing an advergame to the brand that is embedded in the game. Second, arousal is believed to drive primarily conative psychological responses (e.g., purchase intention) via excitation transfer (Mitchell and Nelson Citation2018; Zillmann Citation1971). This psychological mechanism works similarly to affect transfer; however, in this case, not positive affect but residual excitement from playing an advergame is (mis)attributed to the brand or product that was embedded into the game, making the brand seem more exciting.

Notably, a third mechanism, evaluative conditioning, has also been considered by some researchers (e.g., Gross Citation2010; Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko Citation2013) to explain the persuasive effects of advergames. Based on priming theory, evaluative conditioning is grounded in the notion that attitudes are formed via automatic associations. Both activating and building these associations are believed to be automatic cognitive processes and require no active attention. In the context of advergames, Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko (Citation2013) showed that content valence of an advergame can become associated with the embedded brand. Furthermore, they suggest that evaluative conditioning is especially important for explaining the implicit effects of advergames. In sum, when considering the affective processes affect transfer, excitations transfer, and evaluative conditioning, we expect that, overall, advergaming has a positive effect on persuasion.

H3: Advergames have a more positive effect on persuasion compared to nongamified advertising and nonbranded messages.

Do Advergames Influence Choice Behavior?

In addition to driving affective and conative psychological responses (i.e., being persuasive), we expect advergames also to influence actual choice behavior. This expectation is grounded in social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1986), which suggests that people tend to learn new behaviors through observation and reinforcement. More specifically, people are believed to adopt behaviors that they observe to be being accepted and rewarded within a particular context. Such a context could be a group of people but also an advergame (Terlutter and Capella Citation2013).

Behavior displayed in advergames often mimics real-world commercial behavior, like picking up product packages or looking for the target brand. A comprehensive content analysis by Lee et al. (Citation2009) revealed that in about half of the advergames they examined, collecting product packages and brand logos was essential to completing the game. In 20% of the advergames, this behavior was not essential but did offer players an in-game bonus of some kind. This implies that people playing advergames are often not just observing in-game commercial behavior (i.e., collecting product packages) but also being rewarded for it. Drawing on social cognitive theory, we therefore expect that the integration of in-game commercial choice behavior, and the deliberate reinforcement thereof, enforces real-life commercial choice behavior among players of advergames.

H4: Advergames have a more positive effect on choice behavior compared to nongamified advertising and nonbranded messages.

Are Advergames Recognized As Advertising?

As an advertising technique, advergames are often criticized. For example, Skiba, Petty, and Carlson (Citation2019) argue that advergames are, in essence, deceitful and suggest that the gamified design of advergames intentionally distracts players from the commercial nature of the message. This could be problematic because when advergames are not recognized by consumers as advertising, they are not processed as such either. To recognize the persuasive intent of an advertisement, consumers need to have both access to persuasive motives of the persuasive agent as well as cognitive capacity to process these motives (Campbell and Kirmani Citation2000). This means that consumers need to both observe clear cues that suggest the message might be advertising (e.g., brand or product placements) as well as have sufficient cognitive capacity to encode and process them. Consumers are believed to have difficulty meeting either of these two requirements when playing advergames due to the often covert and interactive design of advergames.

Advergames generally contain less clear advertising cues than more traditional types of advertising. Drawing on the persuasion knowledge model (Friestad and Wright Citation1994), this suggests it is potentially not always clear to players that they are being persuaded when playing an advergame. Because recognizing advertising cues is a prerequisite for the autonomous activation of persuasion knowledge (Campbell and Kirmani Citation2000), the absence of clear advertising cues would, thus, likely compromise the processing of an advergame as a persuasive message (Evans and Park Citation2015).

Recognizing the commercial nature of advergames might be further complicated by their interactive (and cognitively demanding) design, which limits the cognitive capacity available while playing them. Lee and Faber (Citation2007) showed that, as a consequence of the limited availability of cognitive capacity, the successful encoding of embedded advertising cues (like brand logos and product placements) can be hindered while playing a game. They explain that the encoding and processing of advertising cues becomes a secondary cognitive processing task and competes for capacity with the now primary task players are performing, which is playing the advergame. This means that we expect consumers, while playing advergames, to be less likely to correctly identify advergames as advertising. Ultimately, this would be reflected in lower levels of persuasion knowledge activation for consumers playing advergames when compared to consumers exposed to more traditional types of advertising.

H5: Advergames have a less positive effect on persuasion knowledge activation compared to nongamified advertising.

Are Children More Susceptible to Advergames?

More than most other types of advertising, advergames seem to particularly appeal to younger consumers (Rathee and Rajain Citation2018). Consequently, brands are regularly criticized for using advergames targeting children to promote potentially harmful products, like high-calorie foods (Staiano and Calvert Citation2012). In the early 1980s, the American beer brand Budweiser was criticized for advertising alcohol to minors with its first advergame-like arcade game, called Tapper. In this game, players took the role of a bartender serving Budweiser beer to thirsty patrons (Nelson Citation2016). The controversy surrounding the game eventually led to Budweiser pulling the game from American arcades.

Unsurprisingly, early advergame studies focused heavily on the effects of advergames on younger consumers like children (e.g., Mallinckrodt and Mizerski Citation2007; Mcilrath Citation2007) and adolescents (e.g., Redondo Citation2012; Verhellen et al. Citation2014). Most of these studies found that children were susceptible to covert advertising messages (Wang and Mizerski Citation2019). However, in a recent overview paper on children as consumers, Mizerski et al. (Citation2017) argued that even though children are generally believed to be more susceptible to persuasive attempts than adults, the empirical evidence for the link between this age-dependent susceptibility to persuasion and actual brand responses remains inconclusive.

Furthermore, Friestad and Wright (Citation1999) suggest that, over time, people develop their general persuasion knowledge through direct experience with particular types of advertising. This general persuasion knowledge can be described as people’s personal knowledge on advertising tactics and motives and enhances their ability to recognize and cope with persuasive tactics in advertising messages. Following this logic, we would expect people to become less susceptible to (and potentially more skeptical of) advertising over time. We thus expect age to have a negative effect on the overall persuasiveness of advergames.

H6: The persuasive effect of advergames is weakened by age.

Methodology

Search and Selection Procedure

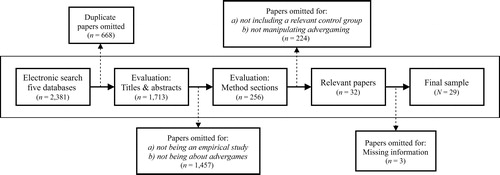

We started by identifying all relevant papers for this meta-analysis with a systematic literature search, performed in June 2020. Going forward, we use the term paper for any document with original analysis and findings (e.g., journal article, working paper, conference paper). To avoid including duplicate effect sizes, our analysis is based on data sets. Note that some papers analyze more than one distinct data set (e.g., a paper describing several experiments), while some data sets are discussed in more than one paper (e.g., an empirical study that is included as a chapter in a doctoral dissertation and as a published journal paper). A visual overview of the search process is included as .

An initial broad search string was formulated: “advergam* OR adver gam* OR brand* gam*”. This string was used to conduct a comprehensive keyword search across five electronic databases (i.e., PsycINFO, Business Source Premier, Communication & Mass Media Complete, Web of Science, and Sociological Abstracts) for which we had imposed no restrictions regarding publication dates of the papers. The corpus retrieved from this initial search consisted of 2,381 academic papers (of which 1,713 were unique) published between 1969 and June 2020.

We used a two-step identification procedure to retrieve all papers that would be included in our meta-analysis. First, we read titles and abstracts of the 1,713 papers to determine broadly whether a particular paper would be potentially relevant to include. A paper had to meet two criteria to be considered for closer inspection: (a) it had to describe an empirical study and (b) the study should examine advergame effects on one of the five outcome variables. Definitions and operationalizations of the outcome (and moderator) variables can be found in .

Table 1. Overview dependent and moderator variables.

To assure that only those papers describing advergame effects were considered, we carefully evaluated the stimulus materials (or the description thereof) of all potentially relevant studies. In practice, this meant that we validated that the stimulus games included only brand cues from a single brand or parent brand. By doing this, we excluded papers that used stimulus games which were conceptually “games containing in-game advertising” rather than “advergames.” In particular, we identified several papers that inconsistently operationalized advergames (e.g., Vashisht and Sreejesh Citation2015; Vashisht and Pillai Citation2017) and had to exclude these papers after close inspection of the stimulus materials. In most cases, the stimulus games were labeled advergames but were conceptually games containing in-game advertising. Notably, some of these papers were included in a recent review paper of advergame effects by Vashisht, Royne, and Sreejesh (Citation2019). At the end of the first step of our screening process, we were left with a short list of 256 potentially relevant papers on advergame effects.

These 256 papers were read attentively to determine whether they could be included in this meta-analysis. To assure that effects could be compared across studies, we aimed to identify all relevant experimental advergame research. For a paper to be relevant, it had to describe an experimental study with (a) at least one advergame condition as well as (b) at least one nonadvergame condition (as reference). This means that if a paper did not describe an experiment, but, for example, described a survey or a content analysis, the paper was omitted. Furthermore, if a paper did describe an experiment, but the experiment did not include a nonadvergame condition for reference, then the paper was also omitted.

Ultimately, the systematic search resulted in the identification of 32 papers that met all criteria. In addition, we considered several pieces of gray literature that were made available by their authors. These included two unpublished dissertations (Lee Citation2013; Van Berlo, Van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2020), two book chapters (Waiguny and Terlutter Citation2011; Van Berlo, Van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2020), and statistical information on variables that were left unreported in the published materials (e.g., Bellman et al. Citation2014; Jung, Kyeong, and Kellaris Citation2011; Van Berlo, Van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2017).

Final Sample and Coding

All collected materials were coded following instruction by Eisend (Citation2017). We extracted all available descriptive information on the sample, advergame, and the individual effect sizes reported in the papers. When information essential for the meta-analysis was not reported in a paper, the authors were contacted. Essential pieces of information included the group sizes of the experimental and control group(s) and the mean and standard deviation of the outcome variables for each of these groups. Unfortunately, two authors could not be reached, and one other was no longer able to retrieve the missing information. This led to the exclusion of three papers (i.e., Panic, Cauberghe, and De Pelsmacker Citation2013; Rifon et al. Citation2014; Yang and Wang Citation2008). A final set of 29 papers, covering 38 data sets, remained. Descriptive information on the data sets can be found in .

Table 2. Overview of selected studies, ordered by year of publication.

Effect-Size Computation

For each outcome variable, we estimated a meta-analytical model following suggestions by Schmidt and Hunter (Citation2015) with point-biserial correlations as common effect size. A total of 168 individual effect sizes were calculated across the five outcome variables. From the coded information we could estimate most point-biserial correlations and their corresponding variance directly.

In some cases, we had to estimate a different effect size first and then apply an algebraic transformation in order to transform the previously estimated effect size into a point-biserial correlation. More concretely, transformations were performed on the standardized mean change scores for within-subjects effects (Morris Citation2008) and on odds ratios when only percentages were reported. To facilitate the transformations from standardized mean change scores into point-biserial correlations we used the R packages “psychmeta” (Dahlke and Wiernik Citation2019) and “metafor” (Viechtbauer Citation2010). For the transformation of odds ratio estimates into point-biserial estimates, the Ulrich–Wirtz approximation (Ulrich and Wirtz Citation2004) was used. This approximation of the point-biserial correlation is recommended when only limited odds ratio information is available (Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez, and Chacón-Moscoso Citation2003). Furthermore, this approximation accounts for the artificially dichotomized nature of the outcome variables (Bonett Citation2007).

Type of Reference Group

To assure the robustness of our meta-analytical models, we included effect-size estimates from a wide range of studies. For the advergame effects on ad attitude, memory, and persuasion knowledge, these effect-size estimates were comparable in that they were all exclusively from studies that compared advergames with other types of advertising (e.g., TV commercials, banner ads). For the effect-size estimates of the advergame effects on persuasion and choice behavior, this was not the case.

When estimating the advergame effects on persuasion and choice behavior, we included effect sizes from both studies that compared advergames with other types of advertising and studies that compared advergames with nonbranded messages (e.g., pretest, control group). Including both types of comparisons allows for a more robust estimation of the integrated effect sizes. Also, effect-size estimates for advergame effects are expected to be comparable across the two types of comparison, in that they are expected to be positive irrespective of whether they are from studies comparing advergames with a branded message or a nonbranded message.

Individual Effect-Size Correction

Once all effect-size estimates were expressed as the common effect size (i.e., point-biserial correlations), we started with correcting the effect-size estimates for artifacts (i.e., study imperfections). We first corrected the effect sizes for small-sample bias because some effect-size estimates were based on samples as small as 20 observations. This correction, which is suggested by Schmidt and Hunter (Citation2015), accounts for the fact that estimates from smaller samples (compared to larger samples) less closely reflect their population estimates. We used the following formula:

(1)

(1)

Afterward, to account for systematic error in the estimates of the dependent variable (i.e., measurement error), we estimated, per study, attenuation factors for each outcome variable. The following formula was used:

(2)

(2)

where rYY represents the reliability coefficient of the outcome variable. When a study did not report the reliability of an outcome variable, we instead used the mean reliability (across data sets) for that outcome variable.

To estimate our integrated effect sizes, we estimated composite effect sizes per study for each of the outcome variables and assigned weights following the Hunter–Schmidt procedure (Schmidt and Hunter Citation2015). This procedure takes into account both the sample size and attenuation factor of a study for weighting and prioritizing studies with larger sample sizes and more reliable measurements. Furthermore, this weighting procedure is found to render more accurate random-effects meta-analytical estimates than the often-used weighting procedures based on inverse variance (Marín-Martínez and Sánchez-Meca Citation2010). The following formula was used to calculate the weights:

(3)

(3)

with i = 1, 2, 3, …, I effect sizes. Afterward, we used the weights (EquationEquation 3

(3)

(3) ) and corrected effect-size estimates (EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) ) to estimate the integrated effect sizes:

(4)

(4)

For each of the integrated effect sizes heterogeneity statistics and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated.

Moderator Analysis

To examine the moderating role of age in the effect of advergaming on persuasion, we also estimated a meta-regression model. The model specifications were similar to those of the main effects models. However, following suggestions by Bijmolt and Pieters (Citation2001), we modeled the errors nested within studies to account for the dependency between effect sizes from the same studies. This hierarchical linear model (HLM) approach is considered best practice for estimating moderating effects with a metaregression model (Bijmolt and Pieters Citation2001). The following general model was used:

(5)

(5)

with j = 1, 2, 3, …, J data sets and

as the average age of participants in the jth data set.

Results

Main Effects

As shown in , significant integrated effects were found for each of the five outcome variables. The data support hypotheses 1 through 5.

Table 3. Advergame effects: Integrated effect sizes and heterogeneity estimates.

Advergame Effect on Ad Attitude

In line with our first hypothesis, we found a positive integrated effect for advergaming on ad attitude ( = .20). This means that, overall, consumers have more positive attitudes toward advergames than toward other types of advertising.

Advergame Effect on Memory

When estimating the effect of advergaming on memory, we found a negative integrated effect ( = −.16). These findings indicate that consumers seem less likely to remember brand and product cues when these are incorporated in advergames compared to when these are incorporated in other types of advertising.

Advergame Effect on Persuasion

As hypothesized, we found a significant positive integrated effect for advergaming on persuasion ( = .11). This indicates that playing advergames can have a positive effect on consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions of the advertised brand.

Advergame Effect on Choice Behavior

In addition to the positive effects of advergaming on persuasion, the meta-analysis also shows that advergaming has a significant positive integrated effect on choice behavior ( = .16). This means that consumers who play an advergame are more likely to choose the gamified brand (or its products) afterward.

Advergame Effect on Persuasion Knowledge

Similar to the effect on memory, we found a significant negative integrated effect for advergaming on the activation of persuasion knowledge ( = −.18). This finding suggests that consumers, overall, seem to activate less persuasion knowledge when playing advergames as compared to when they are exposed to other types of advertising. In other words, consumers are less likely to recognize and process advergames (when compared to other types of advertising) as commercial messages.

Publication Bias

To assess the validity of our findings, we approximated the potential influence of publication bias in our meta-analytical estimates. For each model, we performed an Egger’s correlation test (Sterne and Egger Citation2005) and a rank correlation test (Begg and Mazumdar Citation1994) to test for the association between the observed effect sizes and the precision of the corresponding studies. A significant association, in this case, could be considered an indication of publication bias. As shown in , however, none of the test statistics were significant, meaning that we did not find evidence for publication bias in our estimates. All in all, the results give no indication that publication bias might have influenced our estimations, which reflects the high validity of our findings.

Moderation Effects

Moderating Effect of Age on the Persuasiveness of Advergames

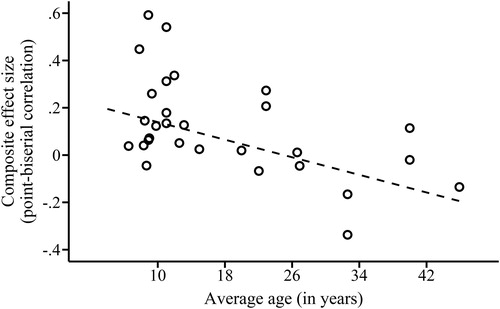

We estimated a metaregression model to examine the moderating role of age in the persuasiveness of advergames. The results, as displayed in , indicate that age is a significant negative moderator of the persuasiveness of advergames, b = −.01, SE < .01, 95% CI [−.01, < .00].Footnote1 This means, as visualized in , that consumers become less susceptible to the persuasive effect of advergames with age—in other words, that older consumers are generally less persuaded by advergames than younger consumers are. The data support hypothesis 6.

Figure 3. Scatter plot of the composite effect-size estimates for persuasion, plotted over the average age per study. The dashed line is the regression line for the effect of age on the effect-size estimate of persuasion.

Table 4. Metaregression estimates explaining variance in the integrated effect size for persuasion.

Notably, the results in also show that the effect of reference group type is nonsignificant. This finding means that when estimating the integrated persuasion effect of advergaming, the branded effect-size estimates do not differ from the nonbranded ones and are thus comparable.

Exploratory Analyses

We ran several exploratory analyses to examine the potential moderating effects of variables that have been used in prior research (e.g., Gross Citation2010; Wanick et al. Citation2018; Van Reijmersdal, Rozendaal, and Buijzen Citation2012; Yegiyan and Lang Citation2010). The moderators that we considered for our exploratory analyses were sex of the player, brand type (real versus fictitious), game-product congruity, exposure time, and advertising cue prominence. For each of these moderators, a separate metaregression model was estimated in which reference group type and age were included as control variables. Note that for the model examining the role of advertising cue prominence we considered four indicators: brand cue interactivity, brand cue centrality, product cue interactivity, and product cue centrality.

Sex of the player and average exposure time were study-related moderators, and this information was thus retrieved directly from the relevant papers. For the remaining moderators, two individual coders coded several characteristics of the stimulus advergames (whenever this information was available). The initial agreement rate was above 80%, and disagreements were resolved through consensus-based discussion. More information about the moderator variables can be found in .

Table 5. Overview moderator variables exploratory analyses.

As shown in , we found a significant effect for only one of the indicators of advertising cue prominence: brand cue interactivity. This indicates that being able to interact with a brand cue, while playing an advergame, increases the persuasiveness of the advergame. For the other exploratory moderators all coefficients were nonsignificant.

Discussion

Drawing on more than a decade of experimental advergame research, this study contributes to the overall understanding of advergaming in two distinct ways. First, by utilizing meta-analytical methods, the study provides insights into the overall effectiveness of advergames and addresses inconsistencies in the literature. More concretely, the study offers insights into the magnitude and significance of five important advergame effects: ad attitude, memory, persuasion, choice behavior, and persuasion knowledge activation. Second, by examining the role of age as a moderator of advergame persuasiveness, the study offers clear empirical evidence indicating a link between age-dependent susceptibility to persuasion and actual consumer responses. Six main conclusions can be drawn from this meta-analysis.

The Overall Effectiveness of Advergames

First, we found that consumers generally show more positive attitudes toward advergames than toward other types of advertising. These findings support our expectation that the gamification of an advertising message enhances consumers’ attitudes toward this message. In a larger advertising context, these results strengthen the notion that perceived hedonic value beliefs can play a crucial role in the formation of attitudes toward experiential advertising formats by partially mitigating the negative effect of general skeptical advertising beliefs on these ad attitudes.

Second, we found that advergaming has a negative effect on memory. The results showed that consumers are far less likely to recognize and recall brands or products when they are exposed to them in an advergame compared to when they are exposed to them in a different advertising format. These findings, which are in line with the limited capacity framework (Lang Citation2000), challenge the popular belief that advergames are effective advertising tactics for promoting brand awareness (e.g., Taylor Citation2019).

Third, we found that advergaming promotes both persuasion and choice behavior. As expected, the gamified nature of advergames drove affective, conative, and behavioral brand outcomes. These findings are in line with those of three recently published meta-analyses on advergames (and other digital advertising tactics) that promote unhealthy eating behaviors among children (Folkvord and Van 't Riet Citation2018; Qutteina, De Backer, and Smits Citation2019; Russell, Croker, and Viner Citation2019). All three studies underline the effectiveness of advergames for driving unhealthy dietary-related choices among children. In addition, Folkvord and Van 't Riet (Citation2018) also found a positive effect of advergaming on attitudes toward (and intention to purchase) unhealthy food products. Our results extend these findings and contribute to the advergaming literature by offering meta-analytical evidence for the overall effectiveness of advergames in a commercial context and for the promotion of non-food-related products across a broader age range.

Fourth, we examined the effect of advergaming on the activation of persuasion knowledge and found that, when compared to other types of advertising, consumers were generally less likely to recognize advergames as advertising. These findings are in line with our expectations. However, from the results it remains unclear whether the observed decrease in persuasion knowledge activation can be attributed to the lack of clear persuasive cues in advergames or to the limited cognitive capacity consumers have available to process advertising cues while playing advergames.

Age As Key Moderator of Advergame Persuasiveness

Fifth, we found that age mitigates the persuasive effects of advergames. Younger consumers seem more susceptible to advergames than older consumers—which is reflected by more positive affective and conative brand responses to advergames for younger consumers. This result contributes to the understanding of young consumers and offers clear evidence in support of a positive relationship between age-dependent susceptibility to persuasion and positive affective and conative brand responses. Moreover, these findings are in line with the persuasion knowledge model (Friestad and Wright Citation1994, Citation1999) and support the notion that people’s understanding of and abilities to cope with particular types of advertising develop over time.

Additional Moderators of Advergame Persuasiveness

In addition to the effect of age on the persuasiveness of advergames, we also tested the effects of several moderators that were included in prior research. The results of these exploratory analyses indicate that brand cue interactivity increases the persuasiveness of advergames. No significant effects were found for the remaining exploratory moderating variables. One should take into consideration, however, that not all studies reported sufficient information on the moderating variables for their data to be included when estimating the exploratory moderation models. These models, therefore, could have been potentially underpowered. With this in mind, examining the confidence intervals of the nonsignificant coefficients could offer additional insight.

Four of the effects (i.e., sex, exposure time, product cue interactivity, and product cue centrality) show confidence intervals that center around the null, which suggests that even if there would be a true effect for these variables, the effect is likely not meaningful. For these variables we can thus conclude with a high degree of confidence that they do not seem to affect the general persuasiveness of advergames. The remaining three effects (i.e., the type of brand, game-product congruity, and brand cue centrality) show confidence intervals that are not evenly centered around the null but instead include either predominantly positive values (in the case of type of brand and game-product congruity) or predominantly negative values (in the case of brand cue centrality). Although this should not be interpreted as evidence for the moderating roles of these variables, it does prevent us from concluding that these variables have no meaningful true effect on the persuasiveness of advergames and could be considered an invitation for further investigation in the future.

Implications

Implications for Researchers

This meta-analysis contributes in various ways to the overall understanding of advergames as gamified advertising, and several important implications for theory and practice can be identified. For researchers, the most important implication concerns the underlying mechanisms of advergame effects. Where the gamified nature of advergames has long been considered primarily its strength, this study shows that it seems more appropriate to consider it a double-edged sword.

When looking at the overall effects of advergames, the outcomes of affective processes (e.g., brand attitude, emotional response) seem predominantly positive, where the outcomes of cognitive processes (e.g., memory retrieval, persuasion knowledge activation) seem predominantly negative. This means that, despite being evidently effective for driving affective (and subsequently behavioral) responses, advergames, more than other types of advertising, seem to be cognitively demanding. This suggests that the actual playing of the advergame distracts from the embedded branded information. Gamifying content thus comes at a (cognitive) cost and hinders the allocation of cognitive resources required for the (critical) processing of the actual gamified message. More concretely, these findings suggest that the gamification of advertising seems to stimulate the affective processing of the advertised message while at the same time hindering its cognitive processing, and thus limits the encoding and storage of the embedded brand information.

Furthermore, during our systematic review of the advergame literature we found that in several papers the advergames that were used did not match the conceptual definition of an advergame as outlined by Terlutter and Capella (Citation2013). More concretely, we found stimulus games labeled as an advergame which were conceptually games containing in-game advertising. This inconsistent conceptualization of advergaming is problematic because advergames and in-game advertising clearly differ. Nelson and Waiguny (Citation2012) state that it is imperative to make a clear distinction between advergames and games containing in-game advertising, because the intentions for the games are clearly different: Advergames are primarily developed with commercial intent, where games containing in-game advertising generally are not. In light of our findings, we therefore reiterate the importance of making a clear conceptual and operational distinction between different types of gamified advertising when studying the effects of gamification in an advertising context.

Implications for Practitioners

For advertising practitioners, our meta-analysis offers several important implications. Overall, as advertising, advergames seem to be liked better by consumers than other types of advertising. This could be considered positive for practitioners, when taking into account that consumers often express negative or ambivalent attitudes toward advertising, which could potentially lead to increased ad avoidance behavior (Jung Citation2018). Furthermore, in terms of advertising effectiveness, the results of the meta-analysis also demonstrate that advergames are especially useful for driving affective and behavioral commercial outcomes. Practitioners are therefore advised to consider using advergames in particular when they have advertising goals like driving brand attitudes, purchase intention, or choice behavior. Moreover, to improve the persuasiveness of the advergame, practitioners are advised to require players to interact with brand cues (e.g., logos) while playing—for example, by including a brand logo as a collectible item in an advergame.

Notably, practitioners who are primarily interested in promoting brand awareness should take into account that the gamified nature of advergames could pose a clear limitation in this respect. When compared to other types of advertising, brand information in advergames seems less likely to be remembered by consumers. While this does not mean that consumers never remember the brands they encounter in advergames, practitioners should take into account that the gamified nature of advergames likely directs consumers’ attention away from the embedded brand information and potentially disrupts the processing of the commercial message.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

All in all, this study offers important implications for theory and practice. However, several limitations should be addressed. First, as with many meta-analyses, not all relevant papers could ultimately be included, primarily due to missing statistical information. Initially, we observed that about one-third of the papers we wanted to include did not report the minimal amount of information needed to be included in our meta-analysis—information such as the sample sizes of the experimental groups and descriptive information (i.e., means and standard deviations) of the dependent variables per experimental group. Another one-third of the papers did contain the information that was minimally required to be included but lacked other important information that could be used to improve our estimations or to test for moderations—information like a clear description of the stimulus material and the sample (e.g., age or sex) and reliability estimates of the measurement scales that were used. Considering these observations, it seems important to stress that when conducting research, the reporting of accurate and complete statistical information is paramount for the facilitation of future meta-analytical research.

Second, the number of currently available data sets could also be considered a limitation. Even though the data allow for a robust estimation of the five integrated advergame effects (and the moderating role of age in the persuasiveness of advergames), they unfortunately do not allow for further differentiation within these integrated effects. This means that even with this being potentially relevant to consider in the context of advergaming, we currently cannot robustly differentiate the persuasive effect of advergaming in terms of affective and cognitive attitude dimensions; nor can we robustly compare the effects of advergaming with that of other specific advertising formats. Fortunately, the study of advergaming and gamified advertising is ongoing, and future (meta-analytical) studies are encouraged to further differentiate the effects of advergames whenever the data allow for this.

Our third limitation is related to the larger field of advertising research and, in particular, the comparative nature of many advergame studies. From a methodological position, we should critically reflect on what it actually means to compare consumer responses to advergames with consumer responses to other advertising formats in experimental studies. When contrasting the effectiveness of an advergame with, for example, a TV commercial from the same brand in a single experimental study, it seems impossible to isolate (and thus manipulate) only a single differentiating factor between the two brand expressions. Manipulating only a single factor is a crucial part of experimental methodology and is essential for being able to draw inferences about the causality of a finding.

This problem could partially be mitigated by adopting multiple message designs. By exposing participants to multiple stimuli within one study for a particular type of message (e.g., advergame, TV commercial), broader theoretical inferences can be drawn (Reeves, Yeykelis, and Cummings Citation2016). A recent example of a study using this particular design is Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy (Citation2019), who used eight different advergames and eight different web advertisements as stimulus material. Going forward, it thus seems advisable to consider multiple message designs when comparing different types of advertisements.

The Future of Advergame Research

Traditionally, advergames were developed as arcade games (Nelson Citation2016) and later gained popularity as desktop-based games. Today, however, advergames are developed for most platforms (e.g., mobile, desktop, virtual reality) and in different formats (e.g., casual games, interactive advertisements, simulation games). With desktop-based (adver)gaming being in decline (Entertainment Software Association Citation2019), other platforms have gained (or are gaining) popularity. In the United States, for example, smartphones are currently the most used devices for gaming, implying that mobile advergames are a likely type of advergame that consumers will come across. However, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are also increasingly becoming more relevant platforms for advertisers to reach their consumer base (Alcañiz, Bigné, and Guixeres Citation2019). Here lies an opportunity for future advergame research, because this plethora of novel advergame types is currently not reflected in the literature. Our systematic review revealed that there is a clear focus on desktop-based advergames and that other platforms, like mobile and VR, have received only limited academic attention (for exceptions, see Catalán, Martínez, and Wallace Citation2019; Okazaki and Yagüe Citation2012; Van Berlo, Van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2020; Van Berlo et al. Citation2021; Van Berlo, Van Reijmersdal, and Rozendaal Citation2020). This is unfortunate, because when compared to more traditional desktop-based advergames these novel types of advergames show a variety of new affordances that could be used to enhance people’s overall consumer experiences while playing them (Flavián, Ibáñez-Sánchez, and Orús Citation2019), for example, location-based reward systems in mobile advergames or consumer–product interactions with virtual products in VR advergames.

All in all, these affordances offer a range of new opportunities for the study of gamified advertising. This future research will help us better understand the workings of gamification in a commercial context and increase our understanding of the potential of gamified advertising in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and the four anonymous reviewers for their insights and constructive remarks on previous versions of this article. Also, we thank Courtney Tabor and Lieke Bos for their assistance with the preparation of the data sets and with the coding of relevant (stimulus) materials.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zeph M. C. van Berlo

Zeph M.C. van Berlo (PhD, University of Amsterdam) is an assistant professor of persuasive communication, Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Eva A. van Reijmersdal

Eva A. van Reijmersdal (PhD, University of Amsterdam) is an associate professor of persuasive communication, Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Martin Eisend

Martin Eisend (PhD, Free University Berlin) is a professor of marketing, European University Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder), Germany.

Notes

1 A second metaregression model was estimated as a robustness test. For this model, only effect-size estimates were considered from branded comparisons. The results were comparable to those displayed in , indicating that the moderating effect of age is robust: ES = 39, b = −.01, SE < .01, 95% CI [−.02, < .00].

References Studies with an asterisk (*) were included in the meta-analysis

- *Agante, L., and A. Pascoal. 2019. How much is “too much” for a brand to use an advergame with children? Journal of Product & Brand Management 28 (2):287–99. doi:10.1108/JPBM-08-2017-1554

- *Ahn, D. 2008. The interpretation of the messages in an advergame: The effects on brand personality perception. Paper presented at the annual meeting for the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC), Chicago, August 6–9.

- Alcañiz, M., E. Bigné, and J. Guixeres. 2019. Virtual reality in marketing: A framework, review, and research agenda. Frontiers in Psychology 10:1530. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01530

- Altmeyer, M., K. Dernbecher, V. Hnatovskiy, M. Schubhan, P. Lessel, and A. Krüger. 2019. Gamified ads: Bridging the gap between user enjoyment and the effectiveness of online ads. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, edited by S. Brewster and G. Fitzpatrick, 1–12. New York: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Begg, C. B., and M. Mazumdar. 1994. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50 (4):1088–101. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2533446.pdf. doi:10.2307/2533446

- *Bellman, S., A. Kemp, H. Haddad, and D. Varan. 2014. The effectiveness of advergames compared to television commercials and interactive commercials featuring advergames. Computers in Human Behavior 32:276–83. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.013

- Bijmolt, T. H. A., and R. G. M. Pieters. 2001. Meta-analysis in marketing when studies contain multiple measurements. Marketing Letters 12 (2):157–69. doi:10.1023/A:1011117103381

- Bonett, D. G. 2007. Transforming odds ratios into correlations for meta-analytic research. American Psychologist 62 (3):254–7. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.254

- Campbell, M. C., and A. Kirmani. 2000. Consumers' use of persuasion knowledge: The effects of accessibility and cognitive capacity on perceptions of an influence agent. Journal of Consumer Research 27 (1):69–83. doi:10.1086/314309

- Catalán, S., E. Martínez, and E. Wallace. 2019. Analysing mobile advergaming effectiveness: The role of flow, game repetition and brand familiarity. Journal of Product & Brand Management 28 (4):502–14. doi:10.1108/JPBM-07-2018-1929

- *Daems, K., P. De Pelsmacker, and I. Moons. 2019. The effect of ad integration and interactivity on young teenagers’ memory, brand attitude and personal data sharing. Computers in Human Behavior 99:245–59. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.031

- Dahlke, J. A., and B. M. Wiernik. 2019. Psychmeta: An R package for psychometric meta-analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement 43 (5):415–6. doi:10.1177/0146621618795933

- *Deal, D. 2005. The ability of branded online games to build brand equity: An exploratory study. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting for the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA), Vancouver, June 16–20.

- Eisend, M. 2017. Meta-analysis in advertising research. Journal of Advertising 46 (1):21–35. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1210064

- Eisend, M., and E. Hermann. 2019. Consumer responses to homosexual imagery in advertising: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advertising 48 (4):380–400. doi:10.1080/00913367.2019.1628676

- Eisend, M., and F. Tarrahi. 2016. The effectiveness of advertising: A meta-meta-analysis of advertising inputs and outcomes. Journal of Advertising 45 (4):519–31. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1185981

- Entertainment Software Association. 2019. Essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association. Accessed October 3, 2019. www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019-essential-facts-about-the-computer-and-video-game-industry.pdf.

- Evans, N. J., and D. Park. 2015. Rethinking the persuasion knowledge model: Schematic antecedents and associative outcomes of persuasion knowledge activation for covert advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 36 (2):157–76. doi:10.1080/10641734.2015.1023873

- *Evans, N. J., B. W. Wojdynski, and M. G. Hoy. 2019. How sponsorship transparency mitigates negative effects of advertising recognition. International Journal of Advertising 38 (3):364–19. doi:10.1080/02650487.2018.1474998

- *Farías, P. 2018. The effect of advergames, banners and user type on the attitude to brand and intention to purchase. Review of Business Management 20 (2):194–209. doi:10.7819/rbgn.v20i2.3784

- Flavián, C., S. Ibáñez-Sánchez, and C. Orús. 2019. The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. Journal of Business Research 100:547–60. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.050

- Folkvord, F., and J. Van ’t Riet. 2018. The persuasive effect of advergames promoting unhealthy foods among children: A meta-analysis. Appetite 129:245–51. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.020

- *Folkvord, F., D. J. Anschütz, and M. Buijzen. 2020. Attentional bias for food cues in advertising among overweight and hungry children: An explorative experimental study. Food Quality and Preference 79:103792. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2019

- *Folkvord, F., F. Lupianez-Villanueva, C. Codagnone, F. Bogliacino, G. Veltri, and G. Gaskell. 2017. Does a 'protective' message reduce the impact of an advergame promoting unhealthy foods to children? An experimental study in Spain and the Netherlands. Appetite 112:117–23. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.026

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1):1–31. doi:10.1086/209380

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1999. Everyday persuasion knowledge. Psychology and Marketing 16 (2):185–94. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199903)16:2%3C185::AID-MAR7%3E3.0.CO;2-N

- Gross, M. L. 2010. Advergames and the effects of game-product congruity. Computers in Human Behavior 26 (6):1259–65. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.034

- *Gurău, C. 2008. The influence of advergames on players' behaviour: An experimental study. Electronic Markets 18 (2):106–16. doi:10.1080/10196780802044859

- *Hudders, L., V. Cauberghe, and K. Panic. 2016. How advertising literacy training affect children's responses to television commercials versus advergames. International Journal of Advertising 35 (6):909–31. doi:10.1080/02650487.2015.1090045

- *Huh, J., Y. Suzuki-Lambrecht, J. Lueck, and M. L. Gross. 2015. Presentation matters: Comparison of cognitive effects of DTC prescription drug advergames, websites, and print ads. Journal of Advertising 44 (4):360–74. doi:10.1080/00913367.2014.1003666

- Jeong, S.-H., and Y. Hwang. 2016. Media multitasking effects on cognitive vs. attitudinal outcomes: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research 42 (4):599–618. doi:10.1111/hcre.12089

- Jung, A.-R. 2018. How do new media environments influence consumer responses to advertising? A meta-analytic approach to ad avoidance. PhD diss., Louisiana State University.

- *Jung, J. M., S. M. Kyeong, and J. J. Kellaris. 2011. The games people play: How the entertainment value of online ads helps or harms persuasion. Psychology and Marketing 28 (7):661–81. doi:10.1002/mar.20406

- Lang, A. 2000. The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication 50 (1):46–70. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x

- *Lee, C.-W. 2013. The effects of flow, self-construal, product involvement, and game-product congruity on brand personality in advergames among college students. PhD diss., Argosy University.

- Lee, M., and R. J. Faber. 2007. Effects of product placement in on-line games on brand memory: A perspective of the limited-capacity model of attention. Journal of Advertising 36 (4):75–90. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367360406

- Lee, M., Y. Choi, E. T. Quilliam, and R. T. Cole. 2009. Playing with food: Content analysis of food advergames. Journal of Consumer Affairs 43 (1):129–54. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2008.01130.x

- *Mallinckrodt, V., and D. Mizerski. 2007. The effects of playing an advergame on young children's perceptions, preferences, and requests. Journal of Advertising 36 (2):87–100. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367360206

- Marín-Martínez, F., and J. Sánchez-Meca. 2010. Weighting by inverse variance or by sample size in random-effects meta-analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement 70 (1):56–73. doi:10.1177/0013164409344534

- *Mcilrath, M. 2007. Children’s cognitive processing of internet advertising. PhD diss., University of California.

- Mitchell, T. A., and M. R. Nelson. 2018. Brand placement in emotional scenes: Excitation transfer or direct affect transfer? Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 39 (2):206–19. doi:10.1080/10641734.2018.1428252

- Mizerski, D., S. Wang, A. Lee, and C. Lambert. 2017. Young children as consumers: Their vulnerability to persuasion and its effect on their choices. In Routledge international handbook of consumer psychology, edited by Cathrine V. Jansson-Boyd and Magdalena J. Zawisza, 327–46. New York: Routledge.

- Morris, S. B. 2008. Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Research Methods 11 (2):364–86. doi:10.1177%2F1094428106291059

- Nelson, M. J. 2016. The tapper videogame patent as a series of close readings. In Proceedings of the First International Joint Conference of DiGRA and FDG, edited by S. Björk, C. O'Donnell, and R. Bidarra, 1–13. Dundee: DiGRA. http://www.kmjn.org/publications/TapperPatent_DiGRA-FDG16.pdf.

- Nelson, M. R., and M. K. J. Waiguny. 2012. Psychological processing of in-game advertising and advergaming: Branded entertainment or entertaining persuasion. In Psychology of entertainment media: blurring the lines between entertainment and persuasion, edited by L. J. Shrum, 93–146. New York: Routledge.

- *Neyens, E., T. Smits, and E. Boyland. 2017. Transferring game attitudes to the brand: Persuasion from age 6 to 14. International Journal of Advertising 36 (5):724–42. doi:10.1080/02650487.2017.1349029

- Obermiller, C., and E. R. Spangenberg. 2000. On the origin and distinctiveness of skepticism toward advertising. Marketing Letters 11 (4):311–22. doi:10.1023/A:1008181028040

- Okazaki, S., and M. J. Yagüe. 2012. Responses to an advergaming campaign on a mobile social networking site: An initial research report. Computers in Human Behavior 28 (1):78–86. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.013

- O’Keefe, D. J. 2013. The relative persuasiveness of different message types does not vary as a function of the persuasive outcome assessed: Evidence from 29 meta-analyses of 2,062 effect sizes for 13 message variations. Annals of the International Communication Association 37 (1):221–49. doi:10.1080/23808985.2013.11679151

- *Ortega-Ruiz, C. A., and A. Velandia-Morales. 2011. Influence of advergaming and advertising on grand recall and recognition. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia 43 (3):511–20.

- Panic, K., V. Cauberghe, and P. De Pelsmacker. 2013. Comparing TV ads and advergames targeting children: the impact of persuasion knowledge on behavioral responses. Journal of Advertising 42 (2–3):264–73. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.774605

- *Pempek, T. A., and S. L. Calvert. 2009. Tipping the balance: use of advergames to promote consumption of nutritious foods and beverages by low-income African American children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 163 (7):633–7. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.71

- Poels, K., W. Janssens, and L. Herrewijn. 2013. Play buddies or space invaders? Players’ attitudes toward in-game advertising. Journal of Advertising 42 (2-3):204–18. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.774600

- Qutteina, Y., C. De Backer, and T. Smits. 2019. Media food marketing and eating outcomes among pre‐adolescents and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews 20 (12):1708–19. doi:10.1111/obr.12929

- Rathee, R., and P. Rajain. 2018. Persuasive advergames: Boon or bane for children. In Application of gaming in new media marketing, edited by Pratika Mishra and Swati O. Dham, 77–95. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Reeves, B., L. Yeykelis, and J. J. Cummings. 2016. The use of media in media psychology. Media Psychology 19 (1):49–71. doi:10.1080/15213269.2015.1030083

- *Redondo, I. 2012. The effectiveness of casual advergames on adolescents' brand attitudes. European Journal of Marketing 46 (11/12):1671–88. doi:10.1108/03090561211260031

- Rifon, N. J., E. T. Quilliam, H.-J. Paek, L. J. Weatherspoon, S.-K. Kim, and K. C. Smreker. 2014. Age-dependent effects of food advergame brand integration and interactivity. International Journal of Advertising 33 (3):475–508. doi:10.2501/IJA-33-3-475-508

- *Rosado, R., and L. Agante. 2011. The effectiveness of advergames in enhancing children's brand recall, image, and preference. Portuguese Journal of Marketing 14 (27):34–46.

- Russell, J. A., and L. F. Barrett. 1999. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (5):805–19. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.805

- Russell, S. J., H. Croker, and R. M. Viner. 2019. The effect of screen advertising on children's dietary intake: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews 20 (4):554–68. doi:10.1111/obr.12812

- Sánchez-Meca, J., F. Marín-Martínez, and S. Chacón-Moscoso. 2003. Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods 8 (4):448–67. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448

- Schmidt, F. L., and J. E. Hunter. 2015. Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Skiba, J., R. D. Petty, and L. Carlson. 2019. Beyond deception: Potential unfair consumer injury from various types of covert marketing. Journal of Consumer Affairs 53 (4):1573–601. doi:10.1111/joca.12284

- *Smith, R., B. Kelly, H. Yeatman, C. Moore, L. Baur, L. King, E. Boyland, K. Chapman, C. Hughes, and A. Bauman. 2020. Advertising placement in digital game design influences children’s choices of advertised snacks: A randomized trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 120 (3):404–13. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2019.07.017

- Staiano, A. E., and S. L. Calvert. 2012. Digital gaming and pediatric obesity: At the intersection of science and social policy. Social Issues and Policy Review 6 (1):54–81. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01035.x

- Sterne, J. A. C., and M. Egger. 2005. Regression methods to detect publication and other bias in meta-analysis. In Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment, and adjustments, edited by H. R. Rothstein, A. J. Sutton, and M. Borenstein, 99–110. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Taylor, C. R. 2019. Why advergames can be dominant on social media: Lessons from popsockets. Forbes, May 14. www.forbes.com/sites/charlesrtaylor/2019/05/14/why-advergames-can-be-dominant-on-social-media-lessons-from-popsockets/#253aca232a31.

- Technavio. 2020. In-game advertising market by platform and geography - Forecast and analysis 2020–2024. Technavio, April. https://www.technavio.com/report/in-game-advertising-market-industry-analysis?utm_source=off_page&utm_medium=web2.0&utm_campaign=2020-ch-w15.

- TechSci Research. 2019. Global gamification market by solution, by deployment, by organization size, by application, by end-user vertical, by region, competition, forecast & opportunities, 2024. TechSci Research, March. www.reportlinker.com/p05762137/global-gamification-market-by-solution-by-deployment-by-organization-size-by-application-by-end-user-vertical-by-region-competition-forecast-opportunities.html?utm_source=prn.

- Terlutter, R., and M. L. Capella. 2013. The gamification of advertising: Analysis and research directions of in-game advertising, advergames, and advertising in social network games. Journal of Advertising 42 (2–3):95–112. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.774610

- Ulrich, R., and M. A. Wirtz. 2004. On the correlation of a naturally and an artificially dichotomized variable. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 57 (Pt 2):235–51. doi:10.1348/0007110042307203

- *Van Berlo, Z. M. C. 2020. Playful persuasion: Advergames as gamified advertising. PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

- *Van Berlo, Z. M. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, and E. Rozendaal. 2017. Weet Wat Er Speelt: De Rol van Merkbekendheid in Effecten van Mobiele Advergames op Tieners. Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap 45 (3):216–36. https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/aac55dba-ce62-4b69-86f7-e776e0a6e101.

- *Van Berlo, Z. M. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, and E. Rozendaal. 2020. Adolescents and handheld advertising: The roles of brand familiarity and smartphone attachment in the processing of mobile advergames. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 19 (5):438–49. doi:10.1002/cb.1822

- *Van Berlo, Z. M. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, E. G. Smit, and L. N. van der Laan. 2020. Inside advertising: The role of presence in the processing of branded VR content. In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Changing Realities in a Dynamic World, edited by T. H. Jung, M. Claudia tom Dieck, and P. A. Rauschnabel, 11–22. Cham: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37869-1_2

- *Van Berlo, Z. M. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, E. G. Smit, and L. N. van der Laan. 2021. Brands in virtual reality games: Affective processes within computer-mediated consumer experiences. Journal of Business Research 122:458–65. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.006

- Van Reijmersdal, E. A., E. Rozendaal, and M. Buijzen. 2012. Brand prominence in advergames: Effects on children’s explicit and implicit memory. In Volume 3 of advances in advertising research, edited by M. Eisend, T. Langner, and S. Okazaki, 321–9. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- *Vanwesenbeeck, I., M. Walrave, and K. Ponnet. 2017. Children and advergames: The role of product involvement, prior brand attitude, persuasion knowledge and game attitude in purchase intentions and changing attitudes. International Journal of Advertising 36 (4):520–41. doi:10.1080/02650487.2016.1176637

- *Verhellen, Y., C. Oates, P. De Pelsmacker, and N. Dens. 2014. Children's responses to traditional versus hybrid advertising formats: The moderating role of persuasion knowledge. Journal of Consumer Policy 37 (2):235–55. doi:10.1007/s10603-014-9257-1

- Vashisht, D., M. B. Royne, and S. Sreejesh. 2019. What we know and need to know about the gamification of advertising: A review and synthesis of the advergame studies. European Journal of Marketing 53 (4):607–34. doi:10.1108/JPBM-02-2015-0811

- Vashisht, D., and S. Pillai. 2017. Are you able to recall the brand? The impact of brand prominence, game involvement and persuasion knowledge in online – advergames. Journal of Product & Brand Management 26 (4):402–14. doi:10.1108/EJM-01-2017-0070

- Vashisht, D., and S. Sreejesh. 2015. Impact of nature of advergames on brand recall and brand attitude among young indian gamers: Moderating roles of game-product congruence and persuasion knowledge. Young Consumers 16 (4):454–67. doi:10.1108/YC-03-2015-00512

- Viechtbauer, W. 2010. Conducting meta-analyses in r with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software 36 (3):1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v036.i03

- *Waiguny, M. K. J., and R. Terlutter. 2011. Differences in children’s processing of advergames and TV commercials. In Volume 2 of advances in advertising research, edited by S. Okazaki, 35–51. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Waiguny, M. K. J., M. R. Nelson, and B. Marko. 2013. How advergame content influences explicit and implicit brand attitudes: When violence spills over. Journal of Advertising 42 (2–3):155–69. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.774590

- *Waiguny, M. K. J., M. R. Nelson, and R. Terlutter. 2014. The relationship of persuasion knowledge, identification of commercial intent and persuasion outcomes in advergames: The role of media context and presence. Journal of Consumer Policy 37 (2):257–77. doi:10.1007/s10603-013-9227-z

- *Wang, L., C.-W. Lee, T. Mantz, and H.-C. Hung. 2015. Effects of flow and self-construal on player perception of brand personality in advergames. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 43 (7):1181–92. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.7.1181

- Wang, S., and D. Mizerski. 2019. Comparing measures of persuasion knowledge adapted for young children. Psychology & Marketing 36 (12):1196–214. doi:10.1002/mar.21266

- *Wanick, V., J. Stallwood, A. Ranchhod, and G. Wills. 2018. Can visual familiarity influence attitudes towards brands? An exploratory study of advergame design and cross-cultural consumer behaviour. Entertainment Computing 27:194–208. doi:10.1016/j.entcom.2018.07.002

- *Wise, K., P. D. Bolls, H. Kim, A. Venkataraman, and R. Meyer. 2008. Enjoyment of advergames and brand attitudes: The impact of thematic relevance. Journal of Interactive Advertising 9 (1):27–9. doi:10.1080/15252019.2008.10722145

- Yang, H.-L., and C.-S. Wang. 2008. Product placement of computer games in cyberspace. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society 11 (4):399–404. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0099

- Yegiyan, N. S., and A. Lang. 2010. Processing central and peripheral detail: How content arousal and emotional tone influence encoding. Media Psychology 13 (1):77–99. doi:10.1080/15213260903563014

- Zillmann, D. 1971. Excitation transfer in communication-mediated aggressive behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 7 (4):419–34. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(71)90075-8