Abstract

Based on culture identity theory and schema theory, we investigate how model ethnicity influences the perception and effectiveness of potentially offensive nudity advertising in Asia and Western Europe. Study 1 with 5,193 ad evaluations by 1,731 subjects from two countries shows that the overall perceived offensiveness in nudity advertising was higher in Asia (China) than in Western Europe (Austria). While previous research indicates that same-ethnicity endorsers are typically favorable for advertising outcomes, our study demonstrates that same-ethnicity endorsers in nudity advertising led to a higher perceived offensiveness and more negative advertising outcomes in Asia, as compared to endorsers of other ethnicities. In Western Europe, in contrast, same-ethnicity endorsers led to a lower perceived offensiveness and more positive advertising outcomes. A follow-up experiment with 373 subjects validated the results. We suggest a model of multi-ethnic offensive nudity advertising effects that is tested with structural equation modeling. Our findings have implications for international advertising theory and international advertising practice.

Nudity ad appeals are popular and frequently used in international advertising (Burnie Citation2020). However, they are a double-edged sword: while they typically attract consumer attention (Dianoux and Zdenek Citation2010), offensive nudity appeals can also lead to adverse reactions toward the advertising and a rejection of the advertised product (Chan et al. Citation2007). Nonetheless, advertising practitioners still rely on “sex sells,” as it touches on humans’ most “basic, primal instincts” (Burnie Citation2020). Yet, the lines between sex in advertising as an artistic means and offensive innuendo are blurry (Hill Citation2017).

Over recent decades, international advertising has become increasingly diversified with regard to the ethnicity of the models depicted. While previous research has shown that advertising effectiveness typically increases with the incorporation of ethnic endorsers that match the target group (Kareklas Citation2010; Sierra, Hyman, and Heiser Citation2012), research has not investigated whether this still holds true when the endorser is presented in a potentially offensive way. Based on schema theory, cultural identity theory, and the cultural values of individualism/collectivism and indulgence/restraint, we address this research gap and analyze how the interplay of model ethnicity and audience ethnicity impacts the perceived offensiveness of nudity ads and subsequent ad and product evaluations. We (1) investigate whether same-ethnicity models in nudity advertising in Asia/Western Europe lead to more or less offensiveness than models of other ethnicities and (2) develop a model of multi-ethnic offensive nudity advertising effects that explains how model ethnicity influences perceived ad offensiveness and subsequent reactions toward the ad and the product. Two studies are conducted, each in two different cultures, one Western European (Austria) and one Asian culture (China). Our research advances international advertising theory by shedding light on the role of model ethnicity for the offensiveness in nudity advertising in different cultures. It also answers calls from advertising practitioners who continuously strive to better understand the factors that contribute to positive or negative effects of nudity advertising (Gallop Citation2015; Burnie Citation2020), with model ethnicity being one of the factors. Given the increasing diversity in model ethnicity in international advertising (Tai Citation2016, Citation2019), practitioners need to know how model ethnicity in nudity advertising affects offensiveness of the advertising and advertising outcomes in different cultures.

Offensive Nudity Appeals in Intercultural Advertising

Offensive Nudity Advertising

Nudity has been identified as one of the major reasons for respondents finding advertisements offensive (Prendergast, Cheung, and West Citation2008; Tariq and Khan Citation2017). Nudity in advertising usually depicts physically attractive models who wear few clothes, thus emphasizing their bodies (Reichert Citation2002; Liu, Cheng, and Li Citation2009). Models can be shown in different stages of undress, ranging from suggestive over partly revealing to nude (Reichert and Ramirez Citation2000). The term offensive, defined as “disgusting” or “repulsive,” is often accompanied by unpleasant feelings, “causing someone to feel resentful, upset, or annoyed” (Lexico Citation2019). Offensive advertising includes messages that transgress laws and customs (e.g., anti–human rights), breach a moral or social code (e.g., sexuality, vulgarity), or outrage the moral or physical senses (e.g., use of violence, use of disgusting images) (Chan et al. Citation2007). When perceived as offensive, nudity advertising can lead to a variety of adverse reactions (Chan et al. Citation2007).

Role of Culture in Offensive Nudity Advertising

Previous research has indicated that culture plays an important role in the perception and evaluation of potentially offensive advertising (Chan et al. Citation2007). Culture alludes to a lens through which a particular group of people perceives the world (McCracken Citation1986) and encompasses values, beliefs, thinking patterns, and behaviors that are learned and shared among a group of people.

Schema Theory and Offensive Nudity Advertising

One theory that might be fruitful in explaining reactions of consumers from different cultural backgrounds toward potentially offensive nudity advertising is schema theory. Schemas are mental structures of organized prior knowledge that guide both the processing of new information and the retrieval of stored information (Fiske and Linville Citation1980). One schema category comprises stereotypes that refer to groups (Hamilton Citation1979) and involves a set of beliefs about the personal attributes of a group of people (Ashmore and Del Boca Citation1981). National or cultural stereotypes are assumed to be relatively homogenous, complex, and more deeply anchored than other stereotypes. They are part of a culture’s social heritage which members of a culture first experience in early childhood and which are frequently portrayed and repeated in the mass media (Diehl and Jonas Citation1991). Stereotypes can be distinguished into auto-stereotypes and hetero-stereotypes. In the context of culture, an auto-stereotype is the image that a nation or culture has of itself, while a hetero-stereotype is the image held by others. Stereotypes are typically consulted in case of missing information about the respective culture itself (Diehl and Jonas Citation1991). They guide the individual’s perception about proper social conduct.

Cultural Identity Theory and Offensive Nudity Advertising

Membership in a culture determines individuals’ cultural identity (Collier and Thomas Citation1988), which is an important component of individuals’ self-identity (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986). According to cultural identity theory (Collier and Thomas Citation1988), an individual’s cultural identity is defined as his/her sense of belonging to a cultural group. Cultural identity implies that the individual internalizes the cultural stereotypes comprising beliefs, values, norms, as well as rules of conduct of that culture.

Culture is known to influence individuals’ attitudes and responses toward advertising stimuli (Lee Citation2019), including nudity appeals (Garcia and Yang Citation2006; Milner and Collins Citation2000; Paek and Nelson Citation2007; Liu, Cheng, and Li Citation2009). Only a few studies have been conducted to examine consumers’ perceptions of and attitudes toward offensive advertising with nudity/sexist appeals from a cross-cultural perspective (Chan et al. Citation2007; De Meulenaer et al. Citation2015; Dianoux and Zdenek Citation2010; Fam and Waller Citation2003; Liu, Cheng, and Li Citation2009; Waller, Fam, and Erdogan Citation2005). Asians in general and Chinese in particular appear less likely to accept sexual content in advertising (Sawang Citation2010; Paek and Nelson Citation2007). A study from Hong Kong revealed that respondents regarded advertising messages that contained sexist attitudes, indecent language, or nudity as highly offensive (Prendergast, Ho, and Phau Citation2002). The study by Chan et al. (Citation2007) also indicated that Asian (Chinese) consumers perceived higher levels of offensiveness in potentially offensive nudity advertisements and found them more disturbing than Western European (German) consumers. A possible explanation is that the portrayal of nudity in public is seen as more inconsistent with existing cultural stereotypes and cultural identity in Asia than in Western Europe. Though it is changing, the stereotype of oppressed and obedient Chinese women still prevails, both among Chinese (Yuxin, Petula, and Lu Citation2007) and Westeners (Yu-Ning Citation2015). Likewise, individuals with a European background were found to be less restrictive in their attitudes toward sexuality than people with Asian ancestry (Meston, Trapnell, and Gorzalka Citation1996, Citation1998). Our first basic hypothesis assumes that the level of perceived offensiveness in nudity appeals is higher among Asian (Chinese) than among Western European (Austrian) consumers:

H1: Overall, Asian (Chinese) consumers perceive the ads with nudity appeals to be more offensive than Western European (Austrian) consumers.

A Model of Multi-Ethnic Offensive Nudity Advertising Effects

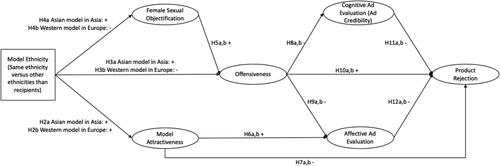

We develop a conceptual model of multi-ethnic offensive nudity advertising effects and analyze how endorser ethnicity in nudity appeals affects perceived offensiveness, affective and cognitive ad evaluations, and product-related outcomes (product rejection). The model also includes female sexual objectification and model attractiveness (see ).

In the current research, we use the construct of ethnicity. There is agreement that both race and ethnicity are social constructs (Gunaratnam Citation2003; Schaefer Citation2008; Yudell et al. Citation2016; Blakemore Citation2019). While the two concepts are related and are often used interchangeably (Schaefer Citation2008), ethnicity is the broader of the two concepts and commonly linked to an individual’s culture and identity. Ethnicity itself is usually based on a person’s culture and nation but also encompasses race (Blakemore Citation2019). The term race can lead to a lot of controversy in many cultures, in particular Western European cultures (deMooij Citation2019). deMooij (Citation2019, 117) explicitly states that “the word race is not used, as scientifically it is viewed as an invalid genetic or biological designation when applied to human beings.”

Model Ethnicity in Advertising

In response to the growing globalization of markets, products, and more culturally diverse societies, advertisers increasingly employ models of different ethnicities. Studies reveal that ethnic diversity on fashion magazine covers (such as Vogue, Cosmopolitan, and Elle) has risen noticeably over the last few years (Tai Citation2016, Citation2019). Previous research has shown that product endorsement by ethnic models tends to have positive advertising effects if the model is of the same ethnicity as the target group (Yin et al. Citation2019; Rößner, Kämmerer, and Eisend Citation2017; Sierra, Hyman, and Torres Citation2009; Brumbaugh and Grier Citation2006). While this effect is particularly pronounced if the model represents a minority group in society, it is also present in many studies that investigated advertising to majority groups. The meta-analysis by Kareklas (Citation2010) showed that both African American (the minority groups) and White consumers (the majority groups) prefer advertising with same-race models. Similar results were found for Asian and Hispanic consumers (Kareklas and Polonsky Citation2010). Another meta-analysis by Sierra, Hyman, and Heiser (Citation2012) revealed that a match of endorser and audience ethnicity generally enhances attitude toward the brand, the ad, the model, and purchase intention.

The more favorable advertising effects of same-ethnicity endorsers are mainly explained by similarity and identification effects. As regards similarity effects, people tend to like other people who have similar attitudes or traits, such as ethnicity (Byrne Citation1971). They feel that future behaviors of others are easier to predict and assume that others who are similar offer a greater chance of being attracted to them (i.e., likeness begets liking) (Byrne Citation1971). As regards identification effects, social identity theory (Tajfel Citation1979) as well as cultural identity theory assume that individuals divide others into ingroups (“we,” groups with whom the individual identifies) and outgroups (“them,” groups with whom the individual does not identify) based on social categorization processes (i.e., based on schemas and stereotypes). Individuals typically favor cultural ingroups over cultural outgroups, increasing the value of the ingroup while decreasing that of the outgroup (Peabody Citation1985). Ingroup favoritism occurs because it helps the individual to improve his/her self-image and satisfaction (Tajfel and Turner Citation1985). If deviant behavior by ingroup members is perceived that may threaten the ingroup, individuals tend to derogate or devalue the deviant individual to avoid harm to their self-identity (Marques, Yzerbyt, and Leyens Citation1988). The devaluation of divergent, disliked ingroup members helps to maintain the overall positive evaluation of the ingroup. Because a same-ethnicity model is perceived as a member of the cultural ingroup, while other-ethnicity models are perceived as members of the outgroup, individuals tend to favor same-ethnicity models to enhance the status of the ingroup.

Model Ethnicity and Model Attractiveness

Attractiveness is often a characteristic of a successful communicator (Ohanian Citation1990) and refers to the physical appearance of the source (Erdogan Citation1999). In nudity advertising, attractiveness is particularly relevant. The sexual appeal of the endorser is in the foreground, and advertising with nudity appeals usually uses attractive endorsers (Lin Citation1998).

As outlined above, there is a tendency to evaluate the own cultural group in a more favorable manner than other cultural groups based on similarity and identification effects (Peabody Citation1985). Respondents of a particular cultural ethnicity are likely to find members of the same ethnicity more attractive than members of other ethnicities. For celebrity endorsers and two ethnicities (African American and Caucasian), Lord, Putrevu, and Collins (Citation2019) showed that consumers find celebrity endorsers of the same ethnicity to be more attractive than those of the other ethnic group. We hypothesize that same-ethnicity models lead to higher perceived attractiveness of the models in their respective culture:

H2a: The use of Asian models as compared to non-Asian models in nudity ads leads to a higher perceived attractiveness of the model in Asia (China).

H2b: The use of Western models as compared to non-Western models in nudity ads leads to a higher perceived attractiveness of the model in Western Europe (Austria).

Model Ethnicity and Perceived Offensiveness

While higher similarity typically reassures the individual because of expectations of mutual understanding and shared norms (Byrne Citation1971), the question arises whether this still holds true if the same-ethnicity endorser violates the norm, for example, through offensive nudity. In this case, the same-ethnicity endorser may threaten to harm the ingroup with negative consequences for individuals’ cultural identity (Collier and Thomas Citation1988). A match of audience and endorser ethnicity might lead to higher perceived offensiveness and more negative ad reactions, if the endorser is perceived to violate the ingroup’s cultural norms by displaying inappropriate behavior.

However, what is perceived as inappropriate behavior of models as regards nudity in intercultural advertising? We draw from two established cultural dimensions that may help to explain reactions to potentially offensive nudity advertising in an intercultural context, (1) individualism versus collectivism and (2) indulgence versus restraint. Both cultural dimensions are described by Hofstede (Citation2011). Collectivistic cultures emphasize the collective good over individual wishes. Individuals are expected to minimize their impact on the community while trying to infuse themselves into the collective level (Hecht et al. Citation2005). Deviance or norm violation are not tolerated and may even be punished by other group members (Dahl, Frankenberger, and Manchandra Citation2003; Fam, Waller, and Yang Citation2009). Individualistic countries, in contrast, strive for independence and personal liberty (Kim and Markus Citation1999). They emphasize self-fulfillment and individualization (Spindler and Spindler Citation1990). Indulgence describes a society that allows for a relatively unrestricted gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun (Hofstede Citation2011). In indulgent countries, people value giving in to their impulses and desires and tend to have more lenient sexual norms. Restraint describes a society that controls for a gratification of needs and regulates it through strict social norms (Hofstede Citation2011). Restrained countries expect the individual to be modest, disciplined, and harmony-seeking (Hecht et al. Citation2005), while impulses and desires are relatively strongly controlled. Restrained countries tend toward stricter sexual norms.

As regards the two countries in our study, China is a representative of a highly collectivistic and restrained country (individualism 20, indulgence 24), whereas Austria represents an individualistic and indulgent country (individualism 55, indulgence 63) (Hofstede Insights Citation2021).

As outlined above, members of a collectivist group are more likely to disapprove of the inappropriate and deviant behavior of other group members, as such behavior threatens the group. In addition, the high level of restraint in China might lead to less tolerance toward transgressions from the norm as compared to indulgent countries. Thus, it can be assumed that exposure to nudity in advertising is likely to offend Asian respondents particularly strongly if an Asian model (cultural ingroup) is depicted in the ad, as compared to models from other cultures (cultural outgroup).

H3a: The use of Asian models as compared to non-Asian models increases the perceived offensiveness of the nudity ads among Asian (Chinese) consumers.

In many Western European countries, nudity is something quite normal and it can be frequently encountered in both the real world (e.g., on beaches or in parks) and in the media (Nelson and Paek Citation2008). Nudity is less frequently perceived as sexual exploitation or an affront (deMooij Citation2019), rendering it a popular tool in European advertising. Consequently, the level of acceptance of nudity in advertising in Western Europe is relatively high (deMooij Citation2019; Nelson and Paek Citation2005). Other than in most Asian cultures, it is not something that clashes with cultural norms or is deemed inappropriate. This should be particularly true if Western models are portrayed, but less so if models of other ethnicities are shown. The rationale is that individuals have stereotypical views of other cultures (Diehl and Jonas Citation1991), which also relates to nudity. Therefore, ads featuring models of other ethnicities (e.g., Asian, Arabic) might be regarded as less conforming and less compatible with the views Europeans hold of other cultures (Yu-Ning Citation2015; Al-Malki et al. Citation2012). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H3b: The use of Western models as compared to non-Western models decreases the perceived offensiveness of the nudity ads among Western European (Austrian) consumers.

Model Ethnicity and Female Sexual Objectification

The depiction of nudity often leads to sexual objectification in advertising (Nelson and Paek Citation2005). Rooted in objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts Citation1997), perceptions of sexual objectification of others occur when an individual’s body or parts of the body are singled out and separated from the individual as a person (Moradi and Huang Citation2008) and the individual is perceived primarily as a physical object of sexual desire (Szymanski, Moffitt, and Carr Citation2011). The objectification of another person can have dehumanizing consequences; for instance, sexualized women are regarded as objects rather than people (Heflick et al. Citation2011; Bernard et al. Citation2012) and are attributed fewer competencies and lower moral standing (Gray et al. Citation2011; Loughnan et al. Citation2010). As objectification in advertising primarily affects women (Ward Citation2016), our study focuses on female sexual objectification, defined as the degradation of women to objects of sexual desire.

Whether and how objectification occurs also depends on respondents’ cultural backgrounds (Loughnan et al. Citation2015). It can be assumed that Asian consumers perceive a higher degree of female sexual objectification when the model is Asian, as compared to a non-Asian model. Chinese tradition values modesty and non-revealing clothing (Croll Citation1995; Yang Citation2004; Zhang Citation2006). In Chinese advertising, Western models are also more likely to display higher levels of nudity than Chinese models (Huang and Lowry Citation2012). If nude Asian models are shown to an Asian audience, it would oppose both Chinese values and Chinese advertising practice, so that a higher level of perceived female sexual objectification is likely to occur as compared to the depiction of models from other ethnicities, in particular Western models. Because Western European consumers are used to seeing Western models in ads as an object of sexual desire when compared to non-Western models, they are likely to perceive less female sexual objectification if Western models are depicted. We hypothesize the following:

H4a: The use of Asian models as compared to non-Asian models in nudity ads increases the perceived female sexual objectification of the model in Asia (China).

H4b: The use of Western models as compared to non-Western models in nudity ads decreases the perceived female sexual objectification of the model in Western Europe (Austria).

Perceived female sexual objectification in advertising has been linked to a variety of negative consequences (Ford, LaTour, and Lundstrom Citation1991; Mittal and Lassar Citation2000). Though acceptance of sexual objectification in advertising has increased over time (e.g., Zimmerman and Dahlberg Citation2008; Choi et al. Citation2016), ads with higher levels of sexual objectification are still perceived as unethical and offensive, which translates into negative responses toward the ad. We summarize that higher perceived female sexual objectification leads to higher perceived offensiveness of the ads and hypothesize the following:

H5: Higher perceived female objectification leads to higher perceived offensiveness in nudity ads in Asia (China) (H5a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H5b).

Effects of Model Attractiveness

Even though some studies also report negative effects of highly attractive models on advertising outcomes (Bower Citation2001; Putrevu Citation2008), the studies reporting positive effects of attractive endorsers in advertising are numerous. They are often explained by the halo effect (e.g., Nisbett and Wilson Citation1977), a cognitive bias that describes the human tendency by which positive impressions of an object/person in one area (e.g., the physical attractiveness of a person) positively influence one’s opinion or feelings about this object/person in other areas (e.g., good nature, social status, competence). Physical attractiveness can increase the perceived credibility of the communicator and his/her persuasiveness (Baker and Churchill Citation1977). Ads with attractive models have been found to enhance ad evaluation (Reichert, LaTour, and Ford Citation2011; Black and Morton Citation2017; Wan, Luk, and Chow Citation2014), message recall (Shimp Citation2007), product evaluation (Kahle and Homer Citation1985), and purchase intention (Caballero and Solomon Citation1984). This suggests that a model’s attractiveness likely increases promotional effectiveness:

H6: Higher perceived attractiveness of the model in nudity ads increases consumers’ affective ad evaluation in Asia (China) (H6a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H6b).

H7: Higher perceived attractiveness of the model in nudity ads reduces product rejection in Asia (China) (H7a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H7b).

Effects of Offensive Nudity Advertising

Ad evaluations typically consist of affective and cognitive evaluations of advertising stimuli (e.g., Shimp Citation1981; MacKenzie and Lutz Citation1989). While cognitive evaluations are based on rational appraisal of the advertising, affective evaluations relate to the emotional appraisal of the advertising stimuli (Hill and Mazis Citation1986). In the current study, we analyze cognitive ad evaluation based on ad credibility, which has often been used in advertising research (Eisend and Tarrahi Citation2016). Ad credibility can be defined as “the extent to which the consumer perceives claims made about the brand in the ad to be truthful and believable” (MacKenzie and Lutz Citation1989, 51). In addition, advertising typically aims at evoking favorable behavioral intentions toward the advertised product. In the context of offensive advertising, however, intentions to reject and not buy the advertised product have been successfully used as a measure for behavioral intentions (e.g., Prendergast and Hwa Citation2003; Chan et al. Citation2007). Thus, in the current study, behavioral intentions are understood as intentions to refuse to purchase the advertised or other products of the same company because of the ad.

Previous studies suggest negative effects of perceived offensiveness on both emotional and cognitive ad evaluations. Nudity perceived as offensive was found to reduce the relevance of ad content (Dianoux and Zdenek Citation2010), leading consumers to dedicate fewer cognitive resources to studying the ad (Reichert, Heckler, and Jackson Citation2001). Consumers’ perceptions of an advertisement regarded as offensive were also found to be strong predictors of their intentions to like and accept respectively reject the advertising content, the advertised product, as well as the brand itself (LaTour and Henthorne Citation1994; Chan et al. Citation2007; Putrevu Citation2008; Capella et al. Citation2010; Ghani and Ahmad Citation2015; Huhmann and Limbu Citation2016). In the same vein, the cross-cultural study by Ford et al. (Citation1994) revealed that respondents who did not like the female endorsers’ role portrayal in an ad were less likely to purchase the advertised product. We hypothesize the following:

H8: Higher perceived offensiveness in nudity ads reduces cognitive ad evaluations in Asia (China) (H8a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H8b).

H9: Higher perceived offensiveness in nudity ads reduces affective ad evaluations in Asia (China) (H9a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H9b).

H10: Higher perceived offensiveness in nudity ads increases product rejection in Asia (China) (H10a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H10b).

Finally, following Chan et al. (Citation2007), who demonstrated that lower affective and cognitive ad evaluations of offensive advertising lead to increased intentions to reject the product, we deduce the final hypotheses:

H11: Lower cognitive ad evaluation of nudity ads increases product rejection in Asia (China) (H11a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H11b).

H12: Lower affective ad evaluation of nudity ads increases product rejection in Asia (China) (H12a) and Western Europe (Austria) (H12b).

Study 1

Study 1 is based on 5,193 ad evaluations by 1,731 subjects from Asia (China) and Western Europe (Austria). The sample was generated using an online survey. As countries in Asia and the Middle East tend to be more conservative than the US and Europe with respect to nudity (Frith and Mueller Citation2004), we wanted to include both an Asian and a European country. China and Austria were selected for several reasons. (1) They are characterized by major cultural differences in relation to the two cultural dimensions relevant to the object of study: (a) individualism versus collectivism and (b) indulgence versus restraint (see above). (2) Austria is a representative of the Germanic Europe cluster that also includes Germany and Switzerland (House et al. Citation2004). (3) Chinese ads present very low degrees of nudity in TV ads and women’s magazine ads, while German ads, which are in most instances aired in an identical way in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (also called the D-A-CH-region), show very high levels of nudity in TV ads (Nelson and Paek Citation2005; Paek and Nelson Citation2007; Nelson and Paek Citation2008). (4) Finally, the D-A-CH region and China have close relationships in trade and also marketing (see, e.g., the DACHINA brand building platform, http://dachinainterchange.org). For all three countries, China is the most important trade partner in Asia (e.g., www.bmwi.de; www.wko.at; www.bmeia.gv.at; www.bfs.admin.ch).

Stimulus Material

Twelve full-page ad stimuli (four ethnic groups x three product categories) were developed for the purpose of this study, resulting in twelve different model/product combinations. The ads incorporated models that represent four ethnic groups: Asian, Western, African, and Arabic. African and Arabic models were included to make sure that possible effects of a match (congruity) between model/subject ethnicity would hold not only for a Western versus Asian comparison but also for other ethnic groups. Each ethnic group was represented by three different models to avoid that subject evaluations were based on one model per ethnic group only. The ads featured products from three different product categories widely used by many consumers in China and Austria: mobile phones, mineral water, and ice cream. All three product categories are regularly promoted in ads with nudity appeals. We used three product categories to prevent responses based on one product category only. While altering model ethnicity, all other ad elements remained practically the same for each product category, that is, the models’ appearances in the ads were comparable, as they were shown in similar postures and wore nearly identical bikinis. As such, each model’s level of nudity can be classified as “scantily clad” (Wirtz, Sparks, and Zimbres Citation2018). The models who presented the products were all either Victoria’s Secret or Otto models (Otto is a large European fashion retailer), but the bikini brand labels were not visible in the ad stimuli and there was no reference to Victoria’s Secret or Otto (see Appendix 1 for sample stimuli). In line with the results of Döring and Pöschl (Citation2006), who analyzed print advertisements in German magazines, and Huang and Lowry (Citation2012), who scrutinized print ads in Chinese magazines, female product endorsers were chosen for the present analysis because women are more often portrayed in nudity appeals and, when compared to men, were found to “present more naked skin in advertisements” (Döring and Pöschl Citation2006, 178). Similar results are reported by Matthes and Prieler (Citation2020) for nudity in television advertising in multiple countries, including Austria and China.

Pretests

The main study was preceded by two pretests. The first pretest (N = 29 students) was conducted to (1) ensure the correct identification of the models’ ethnicities, (2) select suitable brand names, and (3) select suitable slogans for the ads. The second pretest (N = 28 different students) ensured (1) comprehensibility, (2) suitable length of the questionnaire, and (3) perceived realism, high quality of the ads, and their suitability for a typical (online) magazine or newspaper. Pretest details can be found in supplemental online appendix A1.

The questionnaire was administered in Chinese language to the Chinese respondents and in German to the Austrian respondents.

In both countries, a translation–back translation procedure commonly used in cross-cultural surveys was applied (Douglas and Craig Citation2007). The source language of the scales used in the questionnaire was English. Two bilingual native speakers (Chinese and German) translated the English questionnaire into the target languages. Two different bilingual speakers translated the questionnaires back into English. An expert committee consisting of five researchers of the two countries familiar with the study compared the back translations for differences and comparability. Inconsistent translations were discussed and resolved carefully. After the final version of the translation had been approved, the questionnaire was pretested for comprehension and clarity in both countries as described above.

Sample and Procedure

In both countries, subjects were recruited using snowball sampling. An online questionnaire was distributed by students taking research method classes at a university in Austria and China, respectively. Students were instructed to recruit an equal number of men and women older than 18 years to fill in the online questionnaire. They were asked to share an online link with their social media contacts and motivate their contacts to further distribute the link to the questionnaire. Each subject was exposed to one questionnaire with three of the twelve ad versions, that is, each respondent saw three of the four different model ethnicities and all three products. The order of presentation of the model/product combination in each questionnaire was randomized. After having been exposed to one of the ads, subjects were asked to answer questions related to the respective ad. After displaying the three ads, demographic data were collected. In total, 1,131 subjects in China and 600 subjects in Austria participated in the study. Since each subject evaluated three different ad versions, the analyses in the current study are based on 3,393 individual ad evaluations for China and 1,800 individual ad evaluations for Austria. Supplemental online appendix A2 provides an overview of the sample characteristics for both countries.

Measurement of Variables

Supplemental online appendix A3 reports the exact wording of all items, their means (M) and standard deviations (SD).

Offensiveness was measured via three questions based on Chan et al. (Citation2007). Since testing hypothesis H1 included mean comparisons across the Asian (Chinese) and Western European (Austrian) samples, measurement invariance testing of the scale across the two countries following the recommendations by Putnick and Bornstein (Citation2016) and Meade, Johnson, and Braddy (Citation2008) indicated that full measurement invariance across countries was supported (configural invariance supported; full metric invariance supported: Δ CFI [comparative fit index] = 0.000; Δ RMSEA [root mean square error of approximation] = 0.000; full scalar invariance supported: ΔCFI = 0.001; ΔRMSEA = 0.001). This suggests that mean comparisons yielded meaningful results. Affective ad evaluation was measured with four items based on MacKenzie and Lutz (Citation1989) and Diehl, Terlutter, and Mueller (Citation2016). Cognitive ad evaluation (ad credibility) was measured with two items based on MacKenzie and Lutz (Citation1989) and Chan et al. (Citation2007). Female sexual objectification and model attractiveness were both single-item measures adapted from Zimmerman and Dahlberg (Citation2008) and Kahle and Homer (Citation1985). Product rejection was measured with two items based on Prendergast and Hwa (Citation2003) and Chan et al. (Citation2007). Model ethnicity/recipient ethnicity congruity: In the Asian (Chinese) data set, the Asian model was coded 1 and all non-Asian models were coded 0. In the Western European (Austrian) data set, the Western model was coded 1 and all non-Western models were coded 0. Hence, in both data sets, 1 indicates a match between subjects’ cultural background and model ethnicity.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to assess the unidimensionality of all multi-item scales, which was confirmed for each scale. Chinese data set: CFI = .977, RMSEA = .070; Austrian data set: CFI = .970, RMSEA = .083), and discriminant validity following Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) was supported. Supplemental online appendix A4 reports local fit measures (indicator reliability, composite reliability, average variance extracted, and each construct’s highest squared correlation with another construct) and Cronbach’s alpha values.

Results

Level of Offensiveness as Perceived in the Ads

Hypothesis H1 presumed that Chinese consumers perceived higher levels of offensiveness in the ads than Austrian consumers. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out with offensiveness as dependent variable and country as factor. As expected, Chinese consumers perceive the ads overall as significantly more offensive than Austrian consumers (MChina = 3.570, MAustria = 3.305, F = 31.426, p < .01), confirming H1. Mean values among Chinese and Austrian consumers are below the scale’s midpoint, suggesting that the ads are not perceived as overly offensive.

Model Testing

The next set of hypotheses (H2–H12) was explored by use of structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 25. The analyses were carried out separately for the Chinese and the Austrian data sets. As outlined above, in the SEM for China, model type was included as a binary variable with the Asian model coded as 1 and all other models (non-Asian models) as 0. In the SEM for Austria, the Western model was coded as 1, while all other models (non-Western models) were coded as 0. Subjects’ sex and age were included as control variables in both data sets.

Results of the Structural Model

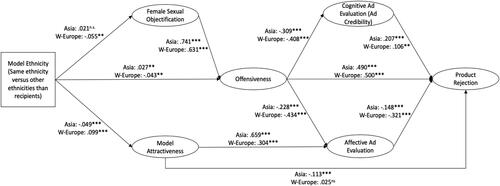

reports the results of the SEM for the Chinese and the Austrian data sets. Overall model fit in both data sets is satisfactory (Chinese data set: CFI = .984, RMSEA = .047; Austrian data set: CFI = .963, RMSEA = .073).

Table 1. Results of structural equation model testing, Study 1.

Chinese data set: With regard to the impact of model ethnicity, results show that the utilization of an Asian model as compared to a non-Asian model tends to increase perceived ad offensiveness (H3a, γ = .027, p < .05), confirming H3a. Contrary to our expectations, the utilization of an Asian model reduces model attractiveness (H2a, γ = −.049, p < .01), while the influence on perceived female sexual objectification (H4a, γ = .021n.s.) is not significant. H2a and H4a are not supported.

Confirming H5a, higher levels of perceived female sexual objectification in the ads lead to higher perceived ad offensiveness (H5a, β = .741, p < .01). Model attractiveness has a strong influence on affective ad evaluation (H6a, β = .659, p < .01) and reduces product rejection (H7a, β = −.113, p < .01). H6a and H7a are supported. Ad offensiveness reduces both affective ad evaluation (H9a, β = −.228, p < .01) and cognitive ad evaluation (H8a, β = −.309, p < .01) and also has a direct and relatively strong influence on product rejection (H10a, β = .490, p < .01), thus lending support to H8a through H10a. Affective ad evaluation decreases product rejection (H12a, β = −.148, p < .01), whereas cognitive ad evaluation increases product rejection (H11a, β = .207, p < .01). Thus, H12a is confirmed, but H11a is rejected.

Austrian data set: As hypothesized, the incorporation of a Western model as compared to a non-Western model reduces female sexual objectification (H4b, γ = −.055, p < .05) as well as perceived ad offensiveness (H3b, γ = −.043, p < .05). In terms of model attractiveness, model ethnicity also has a significant impact in the Austrian data set (H2b, γ = .099, p < .01), with a Western model elevating perceived model attractiveness. H2b to H4b are supported in the Austrian data set.

Similar to the Chinese data set, perceived female sexual objectification in the ads has a relatively strong impact on perceived ad offensiveness (H5b, β = .631, p < .01), supporting H5b. Model attractiveness has a positive influence on affective ad evaluation (H6b, β = .304, p < .01), supporting H6b, but other than in China, it does not mitigate product rejection significantly (H7b, β = .025n.s.). Therefore, H7b is rejected. Perceived offensiveness reduces both affective ad evaluation (H9b, β = −.434, p < .01) and cognitive ad evaluation (H8b, β = −.408, p < .01), validating H8b and H9b. Perceived offensiveness again increases product rejection directly, with the impact being relatively strong (H10b, β = .500, p < .01). H10b is confirmed. Just like in the Chinese data set, affective ad evaluation (H12b, β = −.321, p < .01) decreases product rejection, while cognitive ad evaluation (H11b, β = .106, p < .05) increases product rejection significantly. Thus, H12a is confirmed and H11a is rejected. illustrates the path coefficients in both data sets.

Additional Analysis of Perceived Offensiveness and Model Ethnicity

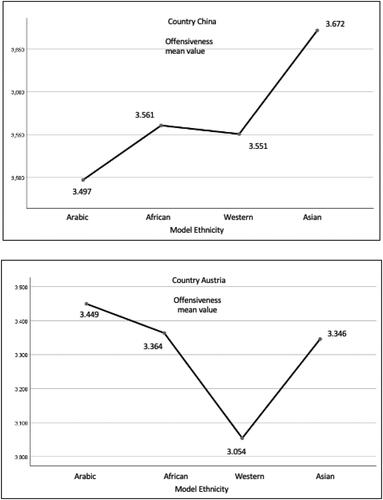

We carried out additional analyses around hypotheses H3a and H3b by looking at the four model ethnicities separately. H3a confirmed that the use of an Asian model leads to higher perceived offensiveness of the nudity ads than non-Asian models in the Asian data set (see above). An ANOVA and contrast tests show that Chinese consumers evaluate the ads featuring the Asian model (MChina, Asian = 3.672) as significantly more offensive than the ads depicting the Western (MChina, Western = 3.551, t = 1.704, p < .10) and the Arabic model (MChina, Arabic = 3.497, t = 2.452, p < .05). The mean difference to the African model points in the expected direction but is not significant (MChina, African = 3.561, t = 1.566, n.s.) ().

H3b confirmed that Austrian consumers evaluate ads featuring Western models as less offensive than ads with non-Western models (see above). An ANOVA and contrast tests show that Austrian consumers perceive the ads depicting the Western model (MAustria, Western = 3.054) as significantly less offensive than ads featuring the Asian (MAustria, Asian = 3.346, t = 2.301, p < .05), Arabic (MAustria, Arabic = 3.449, t = 3.109, p < .01), or African model (MAustria, African = 3.364, t = 2.458, p < .05) ().

Study 2

The aim of study 2 was threefold: (1) First, we wanted to validate our results from study 1, which showed that in China, same-ethnicity endorsers in nudity advertising increase perceived offensiveness and lead to more negative advertising outcomes. In Austria, however, same-ethnicity endorsers reduce perceived offensiveness and lead to more positive advertising outcomes. (2) Second, to further substantiate our arguments that the ethnicity of the model shown in the nudity ad leads to different levels of cultural acceptance, we included a measure of cultural nonacceptance. Cultural (non-)acceptance comprises one’s personal evaluation of whether a stimulus is morally right or wrong as well as one’s perception of whether or not the society in which one lives finds the stimulus acceptable (Reidenbach and Robin Citation1990; Mittal and Lassar Citation2000). Based on cultural identity theory, Chinese respondents are expected to express higher levels of cultural nonacceptance if they see an Asian as compared to a Western model in the nudity ad, because they perceive the scantily clad Asian model as less compatible with their cultural background. (3) Finally, we controlled for product involvement, correct identification of the model’s ethnicity, and model familiarity.

Sample and Procedure

A 2 × 2 × 2 experiment (country: China/Austria × model ethnicity: Asian/Western × product: mobile phone/ice cream) with 373 (China: 177, Austria: 196) students from two midsized universities in China and Austria was carried out. We used models and products that were also used in study 1. The stimuli showed an Asian and a Western model, both either endorsing a mobile phone or an ice cream. Subjects were randomly assigned to one ad and then filled in an online questionnaire. Supplemental online appendix A5 reports the sample distribution in China and Austria.

Measurement of Variables

Measurement of offensiveness was identical to study 1. Partial measurement invariance across countries was supported (configural invariance supported; partial metric invariance supported: ΔCFI = 0.002, ΔRMSEA = 0.000; partial scalar invariance supported: ΔCFI = 0.002, ΔRMSEA = 0.007). Model ethnicity was coded 1 for same-ethnicity endorsers and 0 if model ethnicity and audience ethnicity were different. Cultural nonacceptance was measured with three items adapted from Mittal and Lassar’s (Citation2000) scale of ethical justness/objectionability: “The ad is … (1) morally wrong; (2) unacceptable to me and my family; (3) culturally not acceptable.” Product involvement was measured with one item adapted from Zaichkowsky (Citation1985): “The product shown in the ad is important to me.” Responses were measured from (1) “not at all applicable” to (7) “fully applicable.” Identification of model ethnicity was measured by “The model in the advertisement appears to have the following cultural background (tick one) … Asian/Western.” This question was asked after subjects had evaluated the ad. Model familiarity was measured at the beginning of the questionnaire with the question “Do you know the model?” (yes/no). Subjects who indicated that they knew the model were screened out and the experiment was terminated.

Results

Manipulation check model ethnicity: The manipulation check revealed that all Austrian subjects perceived model ethnicity as expected (100%). In China, 177 of 188 subjects (94.1%) perceived model ethnicity as expected. Ten respondents selected the wrong ethnicity and one value was missing. Thus, manipulations for model ethnicity were successful. The 11 subjects who did not specify ethnicity correctly were excluded from further analyses.

Overall offensiveness in China versus Austria: An ANCOVA with country as factor, offensiveness of the ad as dependent variable, and product involvement as covariate reveals that, across all ad versions, offensiveness is higher in China (estimated marginal mean [EMM]: 4.275) than in Austria (EMM: 3.901; F = 4.275, p < .05), while controlling for product involvement (F = .293, n.s.), sex (F = 2.669, n.s.), and age (F = .467, n.s.). Results from study 2 confirm findings from study 1.

Model ethnicity, offensiveness, and product rejection: To analyze how model ethnicity impacts offensiveness and how offensiveness further impacts product rejection (as outlined in our conceptual model in ), we carried out mediation analyses (e.g., Baron and Kenny Citation1986). In mediation analysis, a indicates the impact of the independent variable (model ethnicity) on the mediator (offensiveness), b indicates the impact of the mediator on the dependent variable (product rejection). Finally, c’ indicates the direct influence of the independent on the dependent variable when the mediator is included. We ran mediation analyses based on Hayes (Citation2009, Citation2017) with 5,000 bootstrap samples, controlling for product involvement, sex, and age.

China: Results indicate that the same-ethnicity model (Asian model) leads to higher offensiveness (a = .597, CI [.113; 1.081]) in China. Higher offensiveness increases product rejection (b = .669, CI [.530; .806]). While the direct effect of model ethnicity on product rejection is not significant (c’ = .402, CI [−.050; .855]), the indirect effect via offensiveness is (.400, CI [.075; .751]).

Austria: Results indicate that the same-ethnicity Western model leads to lower offensiveness in Austria (a = −.505, CI [−.951; −.058]). As in China, higher offensiveness increases product rejection (b = .653, CI [.444; .862]). Similar to the Chinese results, the direct effect of model ethnicity on product rejection is not significant (c’ = −.189, CI [−.780; .402]), whereas the indirect effect via offensiveness is significant (−.330, CI [−.694; −.028]).

Model ethnicity and cultural nonacceptance: We conducted two ANCOVAs with model ethnicity as factor, cultural nonacceptance as dependent variable, and product involvement, sex, and age as covariates.

China: Cultural nonacceptance is perceived significantly higher if an Asian model is shown in Asia as compared to a Western model (EMM Asian model: 4.088; EMM Western model: 3.373, F = 8.849, p < .01), while controlling for product involvement (F = 5.128, p < .05), sex (F = 3.720, p < .1), and age (F = .242, n.s.).

Austria: In Austria, the Western model is perceived as significantly less inacceptable, as compared to the Asian model (EMM Western model: 2.828; EMM Asian model: 3.526, F = 8.055, p < .01), while again controlling for product involvement (F = 0.123, n.s.), sex (F = 1.844, n.s.), and age (F = 0.565, n.s.).

In summary, the results from study 2 lend substantial support to the findings from study 1. First, study 2 confirms that the Chinese audience perceives higher levels of offensiveness in all ad versions than the Austrian audience. More importantly, it also corroborates that offensiveness is significantly higher in China when a same-ethnicity model (Asian model) endorses the products as compared to a Western model. In Austria, the same-ethnicity Western model reduces offensiveness significantly, as compared to an Asian model. In both countries, offensiveness leads to higher levels of product rejection. Finally, study 2 shows that Chinese consumers regard nudity ads as more inappropriate for their culture when the model in the ad is Asian. On the other hand, in Austria, the same-ethnicity (Western) model is perceived as more acceptable than the Asian model.

Discussion and Implications

Our research advances international advertising theory in several ways. In both studies, we found support for previous findings according to which Asian (Chinese) recipients are less accepting of sexual advertising content than Western European (Austrian) recipients (Chan et al. Citation2007; Paek and Nelson Citation2007; Cheung et al. Citation2013). Extending current knowledge, our research shows not only that it is model nudity per se that affects perceived offensiveness but that model ethnicity plays an important role for the perceived level of offensiveness in nudity advertising. We demonstrate that audience reactions to models that are of the same ethnicity as the recipients differ substantially in Asia and Western Europe. While in Asia, an Asian model leads to higher perceived offensiveness as compared to Arabic, Western, or African models, in Western Europe, a Western model leads to lower perceived offensiveness as compared to models of another ethnicity. Previous research has demonstrated that advertising effectiveness typically increases when incorporating ethnic endorsers that match the target group, as shown in two large meta-analyses (Kareklas Citation2010; Sierra, Hyman, and Heiser Citation2012). Our research challenges this notion and demonstrates that this is not necessarily the case in potentially offensive nudity advertising. In an Asian context, a same-ethnicity endorser with a nudity appeal increases the perceived offensiveness of the ad which, in turn, leads to adverse advertising effects.

The less favorable results for Asian models in Asia can be explained by culture identity and schema theory. Asian respondents did not approve of the sexually explicit portrayal of the Asian model (ingroup), as it presumably does not fit with their existing schemes (auto-stereotypes). Schema theory posits that if newly received information does not match existing schemas, it likely triggers negative reactions (Alden, Mukherjee, and Hoyer Citation2000; Orth and Holancova Citation2003). In addition, for Asian respondents, stemming from a collective and more restrained culture, the Asian models’ sexual presentation was probably perceived as indecent and as a potential threat to the cultural ingroup. This lack of congruity led them to perceive the Asian models in a less favorable way, indicating a preference for the non-Asian models (outgroup). Collectivistic countries seem to take particular offense at members of their own ethnic group (ingroup) posing in a way that violates established cultural norms and threatens cultural identity. Study 2 explicitly confirmed a higher level of cultural nonacceptance of an Asian model in nudity advertising in China.

In Austria, which is an individualistic and more indulgent country, where individual fulfillment and self-realization are more important than in collectivistic countries (Hecht et al. Citation2005), the use of partially nude Western models is not unusual and is congruent with existing auto-stereotypes of their ingroup. The depictions of other ethnicities in a sexual way seem to be more incongruent with existing hetero-stereotypes of Chinese women (Yu-Ning Citation2015) or Arab women (Al-Malki et al. Citation2012).

Our study suggests a comprehensive theory-based model of multi-ethnic offensive nudity advertising effects that describes the perception and evaluation of offensive nudity appeals in advertising, taking into account models’ ethnicity. This model can serve as a conceptual framework for further research regarding offensive appeals in advertising, particularly when conducting studies in a cross-cultural context. The conceptual model incorporates models’ ethnicity as a crucial factor, not only for perceived offensiveness but also for other variables. In the Austrian data set, the culturally congruent Western models increased model attractiveness and mitigated both perceived female sexual objectification and offensiveness when compared to the non-Western models. In the Chinese data set, the culturally congruent Asian model produced opposite effects: when compared to the non-Asian models, Asian models decreased model attractiveness while increasing offensiveness.

As expected, perceived female sexual objectification was found to increase the perceived level of offensiveness in both countries, and the impact was rather strong. Model attractiveness positively influenced ad evaluation in both countries; however, it only significantly reduced respondents’ intentions to reject the products in the Chinese data set, but not in the Austrian data set. This sheds additional light on the role of model attractiveness for advertising effectiveness, for which previous literature has produced somewhat mixed findings (e.g., Bower Citation2001). The fact that attractive models reduced product rejection in the Asian data set suggests that the use of attractive models in nudity appeals might be even more important in Asian countries. The role of culture in the relationship between model attractiveness and advertising effects certainly warrants additional research.

Further advancing research on intercultural offensive nudity advertising, our model shows that higher perceived offensiveness negatively impacts both affective and cognitive ad evaluations and increases the intention to reject the products in both cultures. The incorporation of a potentially offensive nudity appeal needs to be carefully considered, and advertisers should control for the potential offensiveness of their ads. Especially perceived female sexual objectification increases the degree of perceived offensiveness. When using nudity stimuli in advertising, advertisers in both countries should avoid the impression that the female body solely serves selling purposes. Overall, our findings indicate that the use of attractive models is advantageous for marketers as they are able to elevate affective ad evaluation and partly mitigate product rejection.

In the Chinese and the Austrian data sets, other than expected, a more positive cognitive ad evaluation, that is, higher credibility of the ad, increases rather than decreases consumers’ intentions to reject the products. The heightened credibility of the ad probably means that the ad is more critically reflected upon, which might then increase the rejection of the products. A more favorable affective ad evaluation can mitigate product rejection.

Responding to practitioners’ calls for a better understanding of the factors that determine the success or failure of nudity advertising (Gallop Citation2015; Burnie Citation2020), model ethnicity, and its cultural acceptance proved to be important factors. While advertisers might attempt to reach a broader and more diverse audience through the inclusion of models from different ethnical backgrounds (Johnson, Elliott, and Grier Citation2010), the results of our study indicate that model ethnicity matters and that culture-congruent models displayed in a potentially offensive way might yield unfavorable effects in some cultures. Our results indicate a clear preference for non-Asian models in China and for Western models in Austria when the models are displayed in a potentially offensive way.

Advertisers must control for the cultural acceptance of model ethnicity and perceived offensiveness of the nudity ad. When consumers get the impression that the female body is sexually objectified to promote a product, the ad’s perceived offensiveness is heightened, which in turn triggers and increases negative cognitive as well as affective ad evaluations. Moreover, it strongly increases consumers’ likelihood to reject the advertised product as well as other products of the company. Clearly, practitioners should attempt to avoid female sexual objectification. When using nudity stimuli in China and Western Europe, model attractiveness has the potential to mitigate some of the negative effects of ad offensiveness. While previous research suggests that the use of same-ethnicity endorsers is favorable for advertising outcomes, our research suggests that the use of same-ethnicity endorsers in nudity advertising in Asia might harm advertising outcomes.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Moving beyond our contribution, we would like to point out some limitations of our study. Our model of multi-ethnic offensive nudity advertising effects was tested in two countries that clearly differ with regard to their cultural particularities. Future studies might benefit from including additional countries, for example, further Asian, European, as well as African and (South and North) American countries. We focused on one form of offensive advertising, that is, nudity appeals. Future research might want to explore different forms of offensive advertising. We included three different product categories, but nevertheless future studies might include additional product categories and well-known brands. Often, nonprofit organizations use offensive advertisements to create more attention for their issues (e.g., in health campaigns for HIV prevention); thus, it would be interesting to compare the results for nonprofit and for-profit organizations. We did not measure product involvement in study 1, but we controlled for it in study 2, where it did not play a major role in the results.

The constructs used in the current study were self-reported measures that bear the risk of common method bias. To avoid common method bias, we assured participants of confidentiality and underlined that there were no right or wrong answers to the individual questions. In addition, we conducted several pretests and avoided items that were ambiguous or vague, also ensuring that the questionnaire and the individual items were as concise as possible (Chang, van Witteloostuijn, and Eden Citation2010; Podsakoff et al. Citation2003).

We did not include a manipulation check for model ethnicity in study 1. The reasoning here is that correct matchings in the pretests were between 93% and 100% for the models that were featured in the main study. In study 2, we included a manipulation check that was successful (Austria 100%; China 94.1%). Future studies might want to focus on consumer demographics, including age, sex, and education related to offensive nudity ads. Males and females might react differently to sexual appeals in advertising (Wirtz, Sparks, and Zimbres Citation2018). If research on gender differences presents the scholars’ focus, future studies might also benefit from including additional cultural dimensions such as masculinity/femininity (Hofstede Citation2011), which have been found to be especially promising when examining similarities and differences in gender perceptions across culture (deMooij Citation2018). Finally, future research might want to thematize regulations regarding nudity advertising in different countries and how these regulations impact perceptions of ad offensiveness.

Supplemental Online Appendix

Download MS Word (55.9 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ralf Terlutter

Ralf Terlutter (PhD, Saarland University) is Professor of Marketing and International Management, University of Klagenfurt.

Sandra Diehl

Sandra Diehl (PhD, Saarland University) is Associate Professor of Media and Communication, University of Klagenfurt.

Isabell Koinig

Isabell Koinig (PhD, University of Klagenfurt) is Assistant Professor of Media and Communication, University of Klagenfurt.

Kara Chan

Kara Chan (PhD, City University of Hong Kong) is Professor of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University.

Lennon Tsang

Lennon Tsang (EdD, University of Hong Kong) is Lecturer of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University.

References

- Al-Malki, Amal, David Kaufer, Suguru Ishizaki, and Kira Dreher. 2012. Arab Women in Arab News: Old Stereotypes and New Media. Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing.

- Alden, Dana L., Ashesh Mukherjee, and Wayne D. Hoyer. 2000. “The Effects of Incongruity, Surprise and Positive Moderators on Perceived Humor in Television Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 29 (2):1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673605

- Ashmore, Richard D., and Frances K. Del Boca. 1981. “Conceptual Approaches to Stereotypes and Stereotyping.” In Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior, editd by David L. Hamilton, 1–36. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

- Baker, Michael J., and Gilbert A. Churchill. Jr. 1977. “The Impact of Physically Attractive Models on Advertising Evaluations.” Journal of Marketing Research 14 (4):538–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400411

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. “The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (6):1173–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bernard, Philippe, Sarah J. Gervais, Jill Allen, Sophie Campomizzi, and Olivier Klein. 2012. “Integrating Sexual Objectification with Object versus Person Recognition.” Psychological Science 23 (5):469–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434748

- Black, Iain R., and Peta Morton. 2017. “Appealing to Men and Women Using Sexual Appeals in Advertising: In the Battle of Sexes, is a Truce Possible?” Journal of Marketing Communications 23 (4):331–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2015.1015108

- Blakemore, E. 2019. “Race and Ethnicity, Explained.” Accessed August 12, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history/2019/02/race-and-ethnicity-explained.

- Bower, Amanda B. 2001. “Highly Attractive Models in Advertising and the Women Who Loathe Them.” Journal of Advertising 30 (3):51–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673645

- Brumbaugh, Anne M., and Sonya A. Grier. 2006. “Insights from a ‘Failed’ Experiment: Directions for Pluralistic, Multiethnic Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 35 (3):35–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367350303

- Burnie, Ally. 2020. “Does Sex Still Sell in 2020?” SmallBusinessConnections, June 24. https://smallbusinessconnections.com.au/does-sex-still-sell-in-2020/

- Byrne, Donn E. 1971. The Attraction Paradigm. New York: Academic-Press.

- Caballero, Marjorie J., and Paul J. Solomon. 1984. “Effects of Model Attractiveness on Sales Response.” Journal of Advertising 13 (1):17–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1984.10672870

- Capella, Michael L., Ronald P. Hill, Justine M. Rapp, and J. Jeremy Kees. 2010. “The Impact of Violence against Women in Advertisements.” Journal of Advertising 39 (4):37–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367390403

- Chan, Kara, Lyann Li, Sandra Diehl, and Ralf Terlutter. 2007. “Consumers' Response to Offensive Advertising: A Cross Cultural Study.” International Marketing Review 24 (5):606–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330710828013

- Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. 2010. “From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (2):178–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

- Cheung, Mei-Chun, Agnes S. Chan, Yvonne M. Han, Sophia L. Sze, and Nicole H. Fan. 2013. “Differential Effects of Chinese Women’s Sexual Self-Schema on Responses to Sex Appeal in Advertising.” Journal of Promotion Management 19 (3):373–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2013.787382

- Choi, Hojoon, Kyunga Yoo, Tom Reichert, and Michael S. LaTour. 2016. “Do Feminists Still Respond Negatively to Female Nudity in Advertising?” International Journal of Advertising 35 (5):823–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1151851

- Collier, Mary J., and Milt Thomas. 1988. “Identity in Intercultural Communication.” International and Intercultural Communication Annual 12:99–120.

- Croll, Elisabeth. 1995. Changing Identities of Chinese Women: Rhetoric, Experience, and Self-Perception in Twentieth-Century China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University-Press.

- Dahl, Darren W., Kristina D. Frankenberger, and Rajesh V. Manchandra. 2003. “Does It Pay to Shock?” Journal of Advertising Research 43 (3):268–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-43-3-268-280

- De Meulenaer, Sarah, Nathali Dens, Patrick De Pelsmacker, and Martin Eisend. 2015. “A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Consumer Responses to Male and Female Gender Role Stereotyping in Advertising.” Paper Presented at ICORIA, London, July 2–4.

- deMooij, Marieke K. 2018. Global Marketing and Advertising: Understanding Cultural Paradoxes. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- deMooij, Marieke K. 2019. Consumer Behavior and Culture: Consequences for Global Marketing and Advertising. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: SAGE.

- Dianoux, Christian, and Linhart Zdenek. 2010. “The Effectiveness of Female Nudity in Advertising in Three European Countries.” International Marketing Review 27 (5):562–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331011076590

- Diehl, Michael, and Klaus Jonas. 1991. “Measures of National Stereotypes as Predictors of the Latencies of Inductive versus Deductive Stereotypic Judgements.” European Journal of Social Psychology 21 (4):317–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420210405

- Diehl, Sandra, Ralf Terlutter, and Barbara Mueller. 2016. “Doing Good Matters to Consumers.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (4):730–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1077606

- Döring, Nicola, and Sandra Pöschl. 2006. “Images of Men and Women in Mobile Phone Advertisements: A Content Analysis of Advertisements for Mobile Communication Systems in Selected Popular Magazines.” Sex Roles 55 (3-4):173–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9071-6

- Douglas, Susan P., and C. Samuel Craig. 2007. “Collaborative and Iterative Translation.” Journal of International Marketing 15 (1):30–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.1.030

- Eisend, Martin, and Farid Tarrahi. 2016. “The Effectiveness of Advertising: A Meta- Meta-Analysis of Advertising Inputs and Outcomes.” Journal of Advertising 45 (4):519–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1185981

- Erdogan, B. Zafer. 1999. “Celebrity Endorsement: A Literature Review.” Journal of Marketing Management 15 (4):291–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379

- Fam, Kim S., and David S. Waller. 2003. “Advertising Controversial Products in the Asia Pacific: What Makes Them Offensive?” Journal of Business Ethics 48 (3):237–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000005785.29778.83

- Fam, Kim S., David S. Waller, and Zhilin Yang. 2009. “Addressing the Advertising of Controversial Products in China.” Journal of Business Ethics 88 (S1):43–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9832-y

- Fiske, Susan T., and Patricia W. Linville. 1980. “What Does the Schema Concept Buy us?” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 6 (4):543–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014616728064006

- Ford, John B., Michael S. LaTour, Earl D. Honeycutt, Jr. and Matthew Joseph. 1994. “Female Role Portrayals in International Advertising.” American Business Review 12 (2):1–10.

- Ford, John B., Michael S. LaTour, and William J. Lundstrom. 1991. “Contemporary Women′s Evaluation of Female Role Portrayals in Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 8 (1):15–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769110034901

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1):39–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., and Tomi-Ann Roberts. 1997. “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21 (2):173–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- Frith, Katherine F, and Barbara Mueller. 2004. Advertising and Societies: Global Issues. New York: Peter Lang.

- Gallop, Cindy. 2015. “Why Social Media Will Make the Future of Sex Social, Unvarnished, and Human,” PR Week, August 24. https://www.prweek.com/article/1361115/future-sex-social-unvarnished-human.

- Garcia, Eli, and Kenneth C. C. Yang. 2006. “Consumer Responses to Sexual Appeals in Cross-Cultural Advertisements.” Journal of International Consumer Marketing 19 (2):29–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v19n02_03

- Ghani, Eesha, and Basheer Ahmad. 2015. “Islamic Advertising Ethics Violation and Purchase Intention.” International Journal of Islamic Marketing and Branding 1 (2):173–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMB.2015.071783

- Gray, Kurt, Joshua Knobe, Mark Sheskin, Paul Bloom, and Lisa Feldman Barrett. 2011. “More than a Body: Mind Perception and the Nature of Objectification.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101 (6):1207–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025883

- Gunaratnam, Y. 2003. Researching Race and Ethnicity. Methods, Knowledge and Power. London: Sage.

- Hamilton, David L. 1979. “A Cognitive-Attributional Analysis of Stereotyping.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by Leonard Berkowitz, Vol. 12, 53–84. New York: AcademicPress.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2009. “Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium.” Communication Monographs 76 (4):408–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hecht, Michael L, Jennifer R. Warren, Eura Jung, and JaniceL. Krieger. 2005. “The Communication Theory of Identity.” In Theorizing about Intercultural Communication, edited by William Gudykunst, 257–78. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Heflick, Nathan A., Jamie L. Goldenberg, Douglas P. Cooper, and Elisa Puvia. 2011. “From Women to Objects: Appearance Focus, Target Gender, and Perceptions of Warmth, Morality and Competence.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (3):572–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.12.020

- Hill, Erin. 2017. “The Blurry Line between Artistic and Offensive Advertising.” The Diamondblock, April 3. https://dbknews.com/2017/04/03/eckhaus-latta-advertising-art-sexualize-objectify/

- Hill, Ronald P., and Michael B. Mazis. 1986. “Measuring Emotional Responses to Advertising.” Advances in Consumer Research 13:164–9.

- Hofstede, Geert. 2011. “Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Hofstede Insights. 2021. “National Culture.” https://hi.hofstede-insights.com/national-culture

- House, Robert J, Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta. 2004. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Huang, Ying, and Dennis T. Lowry. 2012. “An Analysis of Nudity in Chinese Magazine Advertising: Examining Gender, Racial, and Brand Differences.” Sex Roles 66 (7-8):440–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0101-7

- Huhmann, Bruce A., and Yam B. Limbu. 2016. “Influence of Gender Stereotypes on Advertising Offensiveness and Attitude toward Advertising in General.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (5):846–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1157912

- Johnson, Guillaume D., M. Roger Elliott, and Sonya A. Grier. 2010. “Conceptualizing Multicultural Advertising Effects in the ‘New’ South Africa.” Journal of Global Marketing 23 (3):189–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2010.487420

- Kahle, Lynn R., and Pamela M. Homer. 1985. “Physical Attractiveness of the Celebrity Endorser: A Social Adaptation Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (4):954–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209029

- Kareklas, Ioannis. 2010. “A Quantitative Review and Extension of Racial Similarity Effects in Advertising.” Doctoral diss., AAI3415548. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/AAI3415548.

- Kareklas, Ioannis, and Maxim Polonsky. 2010. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Racial Similarity Effects in Advertising.” Advances in Consumer Research 37:829–32.

- Kim, Heejung, and Hazel Rose Markus. 1999. “Deviance or Uniqueness, Harmony or Conformity?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (4):785–800. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.785

- LaTour, Michael S., and Tony L. Henthorne. 1994. “Ethical Judgments of Sexual Appeals in Print Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 23 (3):81–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1994.10673453

- Lee, Wei-Na. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Culture in Advertising: Resolving Persistent Issues and Responding to Changes.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):115–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579686

- Lexico. 2019. Offensive. Oxford University Press. https://www.lexico.com/definition/offensive.

- Lin, Carolyn A. 1998. “Use of Sex Appeals in Prime-Time Television Commercials.” Sex Roles 38 (5/6):461–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018714006829

- Liu, Fang, Hong Cheng, and Jianyao Li. 2009. “Consumer Responses to Sex Appeal Advertising: A Cross-Cultural Study.” International Marketing Review 26 (4/5):501–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330910972002

- Lord, Kenneth R., Sanjay Putrevu, and Alice F. Collins. 2019. “Ethnic Influences on Attractiveness and Trustworthiness Perceptions of Celebrity Endorsers.” International Journal of Advertising 38 (3):489–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1548196

- Loughnan, Steve, Silvia Fernandez-Campos, Jeroen Vaes, Gulnaz Anjum, Mudassar Aziz, Chika Harada, Elise Holland, Indramani Singh, Elisa Puvia, and Koji Tuchija. 2015. “Exploring the Role of Culture in Sexual Objectification: A Seven Nations Study.” International Review of Social Psychology 28:125–52.

- Loughnan, Steve, Nick Haslam, Tess Murnane, Jeroen Vaes, Catherine Reynolds, and Caterina Suitner. 2010. “Objectification Leads to Depersonalization.” European Journal of Social Psychology 40:709–17.

- MacKenzie, Scott B., and Richard J. Lutz. 1989. “An Empirical Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad in an Advertising Pretesting Context.” Journal of Marketing 53 (2):48–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1251413

- Marques, Jose M., Vincent Y. Yzerbyt, and Jacques-Philippe Leyens. 1988. “The "Black Sheep Effect": Extremity of Judgments towards Ingroup Members as a Function of Group Identification.” European Journal of Social Psychology 18 (1):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180102

- Matthes, Jörg, and Michael Prieler. 2020. “Nudity of Male and Female Characters in Television Advertising across 13 Countries.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 97(1):1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020925450

- McCracken, Grant. 1986. “Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of the Structure and Movement in the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods.” Journal of Consumer Research 13 (1):71–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209048

- Meade, Adam W., Emily C. Johnson, and Phillip W. Braddy. 2008. “Power and Sensitivity of Alternative Fit Indices in Tests of Measurement Invariance.” Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (3):568–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568

- Meston, Cindy M., Paul D. Trapnell, and Boris B. Gorzalka. 1996. “Ethnic and Gender Differences in Sexuality: Variations in Sexual Behavior between Asian and Non-Asian University Students.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 25 (1):33–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02437906

- Meston, Cindy M., Paul D. Trapnell, and Boris B. Gorzalka. 1998. “Ethnic, Gender, and Length-of-Residency Influences on Sexual Knowledge and Attitudes.” Journal of Sex Research 35 (2):176–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499809551931

- Milner, Laura M., and James M. Collins. 2000. “Sex Role Portrayals and the Gender of Nations.” Journal of Advertising 29 (1):67–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673604

- Mittal, Banwari, and Walfried M. Lassar. 2000. “Sexual Liberalism as a Determinant of Consumer Responses to Sex in Advertising.” Journal of Business and Psychology 15 (1):111–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007723003376

- Moradi, Bonnie, and Yu-Ping Huang. 2008. “Objectification Theory and Psychology of Women: A Decade of Advances and Future Directions.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 32 (4):377–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x

- Nelson, Michelle R., and Hye-Jin Paek. 2005. “Cross-Cultural Differences in Sexual Advertising Content in a Transnational Women’s Magazine.” Sex Roles 53 (5-6):371–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-6760-5

- Nelson, Michelle R., and Hye-Jin Paek. 2008. “Nudity of Female and Male Models in Primetime TV Advertising across Seven Countries.” International Journal of Advertising 27 (5):715–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048708080281