Abstract

With global geopolitical changes, marketers have increasingly employed advertisements featuring ethnic and religious minority endorsers. Researchers have examined the effects of this practice, where endorsers’ ethnicity and religious associations are interlinked. The present research disentangles the potential effects of these two factors and tests their underlying mechanism. Study 1 (N = 336) shows that the endorser’s belongingness to a religious minority group negatively affects attitudinal and behavioral consumer responses. Furthermore, the results indicate that sociomoral disgust mediates the effects of religion on consumer responses. Study 2 (N = 306) supports a moderated mediation model where religious and ethnic identity moderates the indirect effect of ads featuring a religious minority endorser. Additionally, weaker effects for consumers’ ethnic identity moderating the indirect effect of ads featuring ethnic minority endorsers were found. The results indicate a strong category dominance of religion for the evaluation of ethnic and religious minority endorsers. The findings theoretically contribute to our understanding of the diverse effects of featuring religious and ethnic minority endorsers in advertisements. Theoretical and managerial implications are discussed.

In 2018, an advertising campaign for a new line of vegan fruit gums launched by the German confectioner Katjes stirred a social media storm in Germany. The advertisement showed a half-Turkish, half-Serb model, Vicidca Petrovic, wearing a hijab and happily chewing on a fruit gum. Some right-wing politicians called for the brand to be banned. Others protested the use of a “fake Muslim” in the ad and labeled this act “racial capitalism” (Harper Citation2018). Those strong reactions raise many questions for advertisers. Can advertising with Muslim endorsers or ethnic minority endorsers be effective? Are consumers reacting strongly to the fact that the endorsers belong either to a religious or ethnic minority group or to both? How can these reactions be explained? The answers to these questions may be more critical than ever because despite the growing political opposition to minorities in Europe and the United States (Hameleers Citation2019), marketers and advertisers have increasingly used marketing instruments addressing minority consumers due to potential business opportunities (Franklin Citation2014). The Muslim consumer market is of special interest to practitioners due to the market’s fast growth in terms of size and purchasing power (Khan, Razzaque, and Hazrul Citation2017), and global brands such as H&M and Nike have started using Islamic endorsers (Nike Citation2017).

Scholarly research has shown that the effects of using ethnic minority endorsers in advertising on majority consumer responses are ambiguous. Some scholars have concluded that ethnic majority consumers prefer endorsers with ethnic majority origin and show negative reactions to endorsers of ethnic minority groups (Aaker, Brumbaugh, and Grier Citation2000). Other scholars found that majority consumers respond equally well to majority and minority endorsers (Appiah Citation2007) or react even more positively to minority compared to majority endorsers (Bragg et al. Citation2019). These findings refer to studies that examined ethnic minority endorsers. Very few studies on religious minority endorsers exist, and these studies did not clearly distinguish religion from ethnicity. Butt and de Run (Citation2011) and Rößner, Kämmerer, and Eisend (Citation2017) used religious cues and customs such as a hijab to manipulate the endorser’s ethnicity, thus leading to potential confounds between religion and ethnicity. The confounding effects of religious and ethnic endorser identity, coupled with the mixed research results reported above, are puzzling and raise the following questions: Which endorser characteristic—religion or ethnicity—elicits negative consumer responses, and why?

In this study, we disentangle the effects of ethnic and religious minority endorsers in advertising through experimental data collected in Israel and Germany. We use moral disgust as a mediator variable that explains the underlying mechanism leading to different consumer responses. We further examine the religious and ethnic identity of participants as a moderator variable. Consumers’ ethnic identity is a major factor influencing their responses to advertising (Sierra, Hyman, and Heiser Citation2012). However, advertising research primarily focused on ethnic identity of minority consumers, thus overlooking the majority consumers’ perspective. We propose that the ethnic identity of majority respondents plays a crucial role in influencing advertising effectiveness. Furthermore, although majority groups’ religious identity was found to negatively affect tolerance of stigmatized minorities in general (Gibson Citation2010), this construct has not been examined in the context of advertising thus far. We propose that ethnic identity and religious identity are the main moderators that help explain differing responses of majority respondents to minority endorsers.

These findings contribute to advertising research in several ways. First, this study is the first attempt to disentangle effects of ethnicity and religion in advertising. We find a strong category dominance of religion and demonstrate that negative reactions to minority endorsers in advertising are primarily due to their religion and not ethnicity. Second, we extend El Hazzouri, Main, and Sinclair’s (Citation2019) findings by demonstrating that moral disgust is a mechanism underlying consumer responses not only to sexual minorities but also to other minority groups who face public controversy. Third, we show that consumers’ religious and ethnic identities moderate the mediated effect of featuring religious minorities on consumer response. As religious and ethnic identities increase, the depiction of religious minorities in advertisements elicits higher levels of moral disgust, which, in turn, negatively affect consumer responses. Finally, the findings provide implications for society and practitioners.

Conceptual Background

Disentangling the Effects of Ethnic and Religious Minority Endorsers

Ethnicity and religion are among the most important markers of group identity (Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). These two concepts are often not clearly distinguished, with religion being frequently treated as a component of ethnicity. While in some societies religion may indeed represent a component of one’s ethnic identity, this is not necessarily the general case (Jacobson Citation1997). China serves as an illustration, with 52.2% of the population being religiously unaffiliated. Furthermore, around 38% of Germany’s population, 23% of the United States’ population, and 49% of New Zealand’s population are non-religious (CIA Citation2021). In these cases, religion is not a part of ethnicity.

Ethnicity and religion can offer different and in some ways contradictory modes of self-definition (Jacobson Citation1997). Ethnicity refers to a cluster of people who have common distinguishable cultural traits and share a common language, place of origin, sense of history, traditions, values, beliefs, and identity (Smedley and Smedley Citation2005). This attachment to traditions and customs is non-religious in nature and the focus of ethnicity is the attachment to a country or region of origin (e.g., individuals might self-define as Turkish, Polish, or Italian). While ethnicity of minority groups reflects devotion to different customs and traditions from a distant place of origin, it only has limited relevance or usefulness to its members.

Religion reflects people’s relationship with God. It is a system of beliefs, values, ideas, guidelines, and practices that involves absolute truth claims and moral principles around which believers’ lives are organized. Religion provides certainty and meaningfulness to believers. Religious guidelines and practices (such as fasting, praying five times a day, or certain dietary laws) are more formal than ethnic traditions and customs and are often of higher importance for the religion’s members. Religiously affiliated people belong to a global community, which is not bound to a particular place (e.g., members of a religion can identify as Christian, Muslim, Jewish; this does not depend on any ethnicity or nationality) (Jacobson Citation1997; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). Religion is a dominant and pervasive social categorization. Belonging to a religious group is among the more salient aspects of identity (Commins and Lockwood Citation1978; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). In certain countries, religion has the power to determine individuals’ residential area, school, work, name, accent, physiognomy, attitudes, beliefs, and even whether someone lives or dies (Commins and Lockwood Citation1978).

Religion has a strong influence on behavior of religiously affiliated consumers (Sandikci and Ger Citation2010) but also triggers strong and critical responses of consumers without or with different religious affiliations as evidenced by current media debates about Islam (Georgiou and Zaborowski Citation2017). A large body of research highlights that Western countries share negative views of religious minorities, in particular Muslims. The belief prevails that religious diversity is problematic and that Islam is incompatible with the host culture, resulting in religious differences that are too big to overcome (Masson and Verkuyten Citation1993; Zick, Küpper, and Hövermann Citation2011). Public policies and rhetoric in politics and media have been reinforcing the salience of religious markers and differences increasing social distance between majority and minority populations. Those negative associations are especially prominent for religious compared to ethnic minorities (Fleischmann, Leszczensky, and Pink Citation2019).

Although extensive research regarding ethnic minority endorsers in advertising exists (Sierra, Hyman, and Heiser Citation2012), the effectiveness of religious minority endorsers has been neglected thus far. The two constructs are hard to distinguish and have often been mixed in previous literature (Butt and de Run Citation2011; Hirschman Citation1981). Butt and de Run (Citation2011), for example, embedded religion-specific cues in advertisements to manipulate the endorser’s ethnicity. While using Chinese cues for Chinese endorsers, the authors included Muslim architectural décor, a halal logo, and a model wearing a headscarf for the Malay ethnic group. Similarly, Rößner, Kämmerer, and Eisend (Citation2017) potentially confounded ethnicity and religion by employing ethnic (typical Turkish food) and religious (a hijab) cues. Finally, Hirschman (Citation1981) examined Jews’ consumer behavior in the United States by conceptualizing culture and religion as two dimensions of ethnicity. Overall, researchers have not distinguished the potential differential effects of minority religion from ethnicity on consumer response.

When it comes to the effectiveness of ethnic minorities in advertising, previous studies have shown inconclusive results. Numerous scholars have concluded that people prefer members of the in-group to members of out-groups, resulting in consumers favoring ads with spokespersons who share similar ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Aaker, Brumbaugh, and Grier Citation2000). Thus, majority consumers prefer endorsers of the majority ethnicity to ethnic minority endorsers. This preference, in turn, leads to more unfavorable product evaluations, attitudes toward the ad and brand, and purchase intentions for advertisements with ethnic minority endorsers (Aaker, Brumbaugh, and Grier Citation2000). Other studies could not confirm those negative effects, finding that majority group consumers respond equally well to ads that include ethnic minority and majority endorsers (Appiah Citation2007; Forehand and Deshpandé Citation2001). Some studies even showed that majority consumers react more positively to minority compared to majority spokespersons (Bragg et al. Citation2019).

Although the literature provides ambiguous results for ethnic minority endorsers in advertising when the majority group is addressed, these results might be explained by the importance of salience and category dominance, which is more likely for religious than ethnic minorities. Religion can be more easily identified through visible cues (e.g., religious head coverings or public praying) than ethnicity. As previous researchers have suggested, when category membership becomes salient, people tend to overemphasize differences in critical characteristics for distinct members of out-groups (Song Citation2020; Tajfel Citation1978). This holds especially true for religion, because it can be highly visible and triggers strong and controversial reactions of the majority group (Song Citation2020).

Studies that have tried to detangle the effects of religion and ethnicity are scarce. The few non-advertising studies that exist all point to the direction of the category dominance of religion. Hewstone, Islam, and Judd (Citation1993) examined religious majority and minority groups’ evaluation of target groups varying by religion and nationality. Although religion and nationality are important predictors in forming out-group attitudes, the authors demonstrated a strong category dominance of religion. That is, they found a strong effect of religious in-group–out-group evaluations, while differences in in-group–out-group evaluations based on country were considerably weaker. Furthermore, the authors could not find an interaction between religion and nationality, pointing to two separate in-group–out-group effects. Recent research supports this argument by demonstrating that the negative attitude held by the majority population in the United Kingdom toward Muslim immigrants (i.e., a religious ethnic minority) is chiefly a result of their response to this minority’s religion rather than their ethnicity per se (Helbling and Traunmüller Citation2020). Adida, Laitin, and Valfort (Citation2010) followed this notion and demonstrated that discrimination in the French labor market is actually driven by religion and not ethnicity. The authors confirm the results in an experimental game, which demonstrated that religious similarity is the only significant predictor of homophily, while none of the other predictors (be it gender, age, education, ethnicity, or socioeconomic similarity) had similar predictive power (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2015). Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis (Citation2019) conducted a field experiment in Germany measuring assistance provided to immigrants during daily social interactions and could not find any ethnically driven racism or discrimination. The authors confirmed that religious difference is what defines bias against immigrants, while racial and phenotypical (ethnic) differences on their own are not sufficient to cause bias. The authors reasoned that religious differences play a central role in media coverage and political debates on immigration in Western countries increasing the salience of religious markers (Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis Citation2019).

The mix of religious and ethnic cues in advertising research may explain some of the ambiguous results reported above. As demonstrated in previous research, we expect each factor to independently affect consumer response without conditional or interaction effects (Hewstone, Islam, and Judd Citation1993). Specifically, we follow the line of argumentation above and predict that featuring a religious minority endorser in advertising leads to a negative consumer response. In line with research on ethnic minorities in advertising, we expect that this effect is weaker for an ethnic minority. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

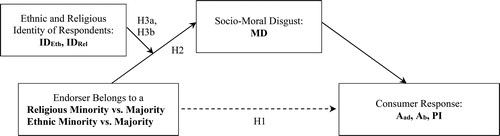

H1: Depicting a religious minority compared to a religious majority endorser in advertisements leads to negative consumer responses, while this effect is weaker or not statistically significant for an ethnic minority compared to a majority endorser.

The Mediating Effect of Sociomoral Disgust

Negative emotions dominantly affect consumer responses as these emotions surpass other consumer behavioral (Lammers, Ullmann, and Fiebelkorn Citation2019) and advertising message factors (Warren, Carter, and McGraw Citation2019). One such prominent negative emotion is disgust. Disgust is a strong emotion, which has evolved to stimulate revulsion at harmful (Rozin, Haidt, and McCauley Citation2008) and potentially contaminating objects (Rozin, Haidt, and Fincher Citation2009). Advertising and marketing cues that invoke disgust hurt consumer attitudes (Borau and Bonnefon Citation2017) and reduce product evaluation, purchase intent, and willingness to pay (Morales and Fitzsimons Citation2007).

Sociomoral disgust is one form of disgust which is primarily experienced in the social domain. It is elicited when moral offenses are associated with certain people one may come in contact with (Rozin, Haidt, et al. Citation1999), including gays, felons, and people of different religious groups (Moll et al. Citation2005). Moral disgust drives people to reject anything perceived to be spiritually contaminating of the self (Horberg et al. Citation2009). Violations of moral and religious principles are major elicitors of sociomoral disgust (Tybur, Lieberman, and Griskevicius Citation2009). Consequently, out-group religious minorities are exceptionally influential in eliciting disgust, as they pose a sense of threat to one’s spiritual purity (Ritter and Preston Citation2011). Sensing a threat may translate into disgust, which, in turn, hurts consumer response to the advertisement.

In principle, consumers may respond to those who object to others by experiencing multiple negative moral emotions, including contempt, anger, and disgust (for a recent review see Greenbaum et al. Citation2020). These emotions, however, vary by the specific types of moral violations they stem from. Contempt arises from violations of communal codes, anger from violations of individual rights, and disgust from violations of the ethics of divinity or God’s rules or one’s spiritual purity (Rozin, Lowery, et al. Citation1999). Accordingly, disgust is the most relevant negative moral emotion elicited by advertisement depicting religious and ethnic minorities.

Ethnic minorities depicted in advertisements may elicit negative responses by the ethnic majority consumers (e.g., Haidt et al. Citation1997), but in contrast with the case of religious minorities, sociomoral disgust responses are weaker. People’s ethnicity is rooted in their shared place of origin (Smedley and Smedley Citation2005). Although associated with a distinct culture, language, and traditions, people’s ethnicity may not be as influential as religion in dictating their sense of morality, spirituality, and life values. Cottrell and Neuberg (Citation2005) found that the prominent emotion that Caucasians experienced toward African Americans was fear, whereas disgust was experienced strongly toward gay men (Cottrell and Neuberg Citation2005).

Recent advertising research supports the adverse effect of depicting stigmatized minorities in advertisements. El Hazzouri, Main, and Sinclair (Citation2019) found that presenting (heterosexual) consumers with advertisements featuring homosexual minorities hurt consumers’ attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand and that this effect is mediated by disgust. Although disgust is typically directed toward the source of the threat (Galoni, Carpenter, and Rao Citation2020), disgust can transfer from the endorser to the object promoted in the ad, even with no physical contact (Russell et al. Citation2017). This effect is due to the contagion property of disgust (Morales and Fitzsimons Citation2007).

The present research extends El Hazzouri, Main, and Sinclair’s (Citation2019) work in several respects. First, moral opposition to homosexuality is rooted in specific religion and biblical laws (Brooke Citation1993). Thus, we argue that sociomoral disgust is an underlying mechanism of minority religion effects, but less so for ethnicity effects. Second, we propose that this effect influences not only consumer attitudes but also behavioral responses such as purchase intention. Finally, El Hazzouri, Main, and Sinclair (Citation2019) suggested that disgust may mediate consumer response to ads featuring ethnic minorities and Muslims. This proposition is tested in the present research.

Based on the literature and the line of reasoning above, we expect advertisements that depict religious minority endorsers to elicit sociomoral disgust experienced by majority consumers but that this effect is weaker for ethnic minority endorsers. Sociomoral disgust, in turn, will adversely affect consumer response to the endorser and advertisement. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H2: Sociomoral disgust mediates the negative effect of an endorser depicted as belonging to a religious minority on consumer response to the advertisement, while this effect is weaker or not statistically significant for the depiction of ethnic minorities.

The Moderating Effect of Ethnic and Religious Identity

A sense of identity is closely linked to group membership, which, in turn, influences intergroup behavior. Individuals identify with a group who is relevant or important to them and make distinctions between people who belong to this group (the in-group) and people who do not belong to the group (the out-group; Brewer Citation1979; social identity theory, Tajfel et al. Citation1979). The process of identification, and the degree to which an individual identifies with the in-group, depends on personal characteristics, preferences, needs, experiences, and circumstances and is powerful in shaping how people think, feel, and act toward others. The resulting responses to out-group members can be positive, neutral, or negative (Jackson Citation2002). High levels of identification lead to positive in-group bias resulting in people favoring members of the in-group over members of out-groups and fostering negative out-group attitudes, prejudice, and discrimination (Jackson Citation2002; Verkuyten Citation2007).

Ethnic identity is a central element of identity, and individuals derive positive self-attitudes from belonging to an ethnic group (Phinney Citation1992). As ethnic identity develops in early childhood, it is formative and has a strong influence on the development of values, norms, and behaviors (Bar-Tal Citation1996). As ethnic diversity increases in a country, the issue of ethnic identity becomes more salient for members of the ethnic minority and majority, which can lead to people placing more importance on ethnic identity (Phinney Citation1992). As a result, high levels of ethnic identity of the majority group in a country can lead to in-group bias and prejudice against out-group members (Masson and Verkuyten Citation1993). Especially highly visible minority groups are more likely to stand out as potential competitor out-groups, and the correlation between ethnic identity and prejudice is particularly strong for members of the majority ethnicity compared to minority ethnicities (Jackson Citation2002).

From the majority consumers’ perspective, ethnic- and religious minority endorsers who are featured in advertisements represent ethnic and religious out-groups, respectively. In line with the literature above, majority consumers’ identity strengthens their reactions to endorsers in a similar way it affects their response to ethnic and religious out-groups in general. This adverse reaction can have an emotional dimension (Jackson Citation2002; Verkuyten Citation2007), in this case sociomoral disgust.

We assume that ethnic minorities pose a threat to the identity of ethnic majority consumers leading to negative emotional responses and, thus, to heightened levels of moral disgust. This response, in turn, negatively influences responses to advertising. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3a: Consumers’ ethnic identity moderates the effect of an endorser depicted as belonging to an ethnic minority on sociomoral disgust. That is, with increasing levels of ethnic identity, sociomoral disgust increases, which, in turn, decreases advertising effectiveness.

Unlike ethnicity, religion is often a part of identity that is selective and, therefore, a strong source of identification. This is emphasized by the notion that religiously affiliated individuals often identity themselves as a member of a religious group when asked about their ethnic background (Thomas and Sanderson Citation2011).

Individuals who derive explicit moral truths from religion often hold negative out-group bias toward members of other religions or nonbelievers and groups such as sexual minorities or criminals who violate religiously held world views or values (Verkuyten Citation2007; Zick, Küpper, and Hövermann Citation2011).

Researchers have shown that the level of identification with one’s religious group is often positively related to prejudice against out-groups and, therefore, an important predictor of political tolerance for unpopular social groups (Gibson Citation2010). Studies investigating the relationship between church attendance and racial, ethnic, and religious prejudice found higher levels of prejudice in churchgoers compared to non-churchgoers (Beatty and Walter Citation1984).

Scholars often found a positive correlation between the level of religiosity and prejudice against out-groups and showed that religiosity can increase intolerance for an out-group (Merino Citation2010). Many studies identified that religious orthodoxy and theological exclusivism—that is, the belief that the majority religion is the absolute truth and the only way to understand God—decreases attitudes toward religious diversity and willingness to integrate religious minorities such as Muslims and Jews in Western societies (Merino Citation2010).

We assume that religious identifiers perceive religious minority out-groups as violating values and world views held by the majority group. Furthermore, other religious groups are perceived as competitors for resources increasing negative emotional responses. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3b: Consumers’ religious identity moderates the effect of an endorser depicted as belonging to a religious minority on sociomoral disgust. That is, with increasing levels of religious identity, sociomoral disgust increases, which, in turn, decreases advertising effectiveness.

presents the conceptual framework and hypotheses that guide our research.

The Experimental Context of This Research: Germany and Israel

The present research includes two experimental studies that were conducted in Israel and Germany. This allows us to eliminate some location-specific explanations for the results, extending the generalizability of our findings. We selected Germany and Israel as sampling frameworks because they differ in several aspects of importance for the topic of this research. Yet, they are comparable in respect to people’s attitudes and responses to ethnic and religious minorities (Witte Citation2018).

In particular, sampling participants from two countries that differ in their general level of religious and ethnic identity generated sufficient variation in participants’ religious and ethnic identities. We included Israel as a country where religion is of central importance. In Israel, less than 5 percent (4.3%) of the population has no religious affiliation. We included Germany as a country where religion plays a moderately important role. In Germany, more than one-third of the population (38%) has no religious affiliation (CIA Citation2021). In terms of ethnic background, as ethnic diversity increases in a country, minority and majority members place more importance on ethnic identity (Phinney Citation1992). Israel and Germany also substantially differ in the ethnic composition of their population. Israel is ethnically diverse, with the majority (52.28%) of the Jewish population having origins from foreign countries (CBS Citation2020). Furthermore, Israel’s ethnic identity is highly visible and resistant to change (Lewin-Epstein and Cohen Citation2019). In contrast, Germany is considerably more ethnically homogenous, with 75.40% of its population having origins in Germany (StBA Citation2021). Due to this and Germany’s long-standing active role within the process of European integration, the ethnic identity of the German majority is less pronounced (Bedrik et al. Citation2015). In the next sections, we describe the two studies and explain how the endorsers’ ethnic/religious affiliation was manipulated in each country such that confounding effects were minimized.

Study 1

The objective of this study was to test the differential effects of an endorser’s ethnicity and religion on consumer response and the mediating effect of moral disgust as suggested in hypotheses 1 and 2. To avoid potential confounding effects, such as self-referencing caused by ethnic minority celebrity endorsers or other public figures who belong to minority groups (e.g., Ibtihaj Muhammad, Nadiya Hussain, and Paul Pogba), we focused on layperson endorsers.

Procedure and Design

The study was conducted in Israel. We applied a 2 (religion: minority vs. majority endorser) by 2 (ethnicity: minority vs. majority endorser) between-subjects design. Four versions of advertisements were created for a fictitious cereal brand “BestCorn.” To avoid confounding factors related to the endorser’s appearance, we used the same female endorser in all four conditions and manipulated religion and ethnicity with visual cues. The endorser’s religion was manipulated by depicting the endorser wearing a hijab or unveiled. A hijab is a head covering worn by some Muslim women that has become a highly salient symbol of Muslim women’s identity (El Guindi Citation1999). Recent research suggests that the hijab visibly differentiates Muslim women from non-Muslim women although its specific design, color, and style may be associated, to some extent, with a particular region (Hassan and Harun Citation2016). In line with past research, to avoid confounding factors related to the endorser’s religious affiliation, religion was manipulated by depicting her wearing a simple black and commonly used hijab (King and Ahmad Citation2010). The endorser’s ethnicity was manipulated by presenting the endorser as a Black or White person. Black immigrants constitute a major ethnic group possessing high prominence and visibility in Israel (Kimmerling Citation2004). The endorser’s facial skin color was modified using Adobe Photoshop. All other visual elements were identical across conditions (see supplemental online Appendix 1).

To pretest the manipulations, 120 undergraduate students were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions and presented with the stimulus. Participants then indicated on a three-item seven-point scale (1 = very unlikely, 7 = very likely) the extent to which they thought the person in the ad belonged to an ethnic minority (e.g., “the person belongs to an ethnic minority,” “the parents or grandparents were born outside Israel”; α = .74) and to a religious minority in Israel (e.g., “the person belongs to a religious minority,” “the person practices a religion different from the mainstream religion”; α = .98). To control for possible confounds, attractiveness was measured on a five-item seven-point scale (unattractive/attractive, not classy/classy, ugly/beautiful, plain/elegant, not sexy/sexy; α = .88; Bower and Landreth Citation2001; Ohanian Citation1990).

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the ethnic minority endorser was more likely to be perceived as such in the ethnic minority compared to the ethnic majority condition (M = 5.34 vs. 2.96; F(1, 116) = 77.96, p < .01). The religious minority endorser was more likely to be perceived as such in the religious minority compared to the religious majority condition (M = 6.75 vs. 1.79; F(1, 116) = 702.34, p < .01). No statistically significant main or interaction effects were found for the ethnic and religious condition on attractiveness (p > .05). Therefore, the pretest indicated successful manipulations.

Participants

Because we were interested in majority consumers’ responses (74% of the population in Israel is Jewish, 17.8% is Muslim, and only less than 8% has a different or no religious affiliation), a national sample of 336 adult participants who represent the Israeli population (Jewish with no migration background) (Mage = 44.27, 55.36% female) completed the study in exchange for payment. Participants were recruited via a leading Israeli online research panel.

Measurements

Participants completed a questionnaire that measured the dependent and mediating variables, assessed the manipulation, and provided participant demographics. Demographics included age, gender, level of education, residence, average income, and religious affiliation. Endorser's perceived belongingness to an ethnic and religious minority as well as attractiveness were measured as described in the pretest section above. Attitudes toward the ad (Aad), attitudes toward the brand (Ab), and purchase intention (PI) were measured with scales commonly used to assess advertising effectiveness (Mitchell and Olson Citation1981). Participants reported their attitudes toward the ad on a six-item seven-point scale (bad/good, unlikeable/likeable, unpleasant/pleasant, unfavorable/favorable, boring/interesting, unconvincing/convincing; α = .83). To assess attitudes toward the brand, a four-item seven-point scale was used (bad/good, negative/positive, unpleasant/pleasant, unattractive/attractive; α = .78). Purchase intention was measured with a single-item scale asking what the probability was that participants would purchase the “advertised” brand if available in their area (1 = very unlikely, 7 = very likely). Sociomoral disgust (MD) was measured based on Schnall et al. (Citation2008) and Tal et al. (Citation2017) on a four-item scale (“I morally object to the person who is shown in the ad,” “I morally oppose the person who is shown in the ad,” “I am disgusted by the person who is shown in the ad,” “I am disgusted by the ad”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .87).

Results

We ran an ANOVA with two factors (religion and ethnicity) on the manipulation assessments and dependent variables (see supplemental online Appendix 2 for descriptive statistics). The manipulation assessments showed a main effect of ethnicity; the endorser in the ethnic minority (compared to the ethnic majority) condition was more likely to be perceived as belonging to an ethnic minority (M = 4.78 vs. 4.22; F(1, 332) = 10.54; p < .01). We found a main effect of religion; the endorser in the religious minority (compared to the religious majority) condition was more likely to be perceived as belonging to a religious minority (M = 6.65 vs. 3.56; F(1, 332) = 344.48; p < .01). No interaction or main effects were found for attractiveness (p > .05). The results confirmed successful manipulations.

In line with hypothesis 1, we found a negative main effect of religion on attitudes toward the ad (Mrel.minority = 3.53 vs. Mrel.majority = 4.46; F(1, 332) = 58.31; p < .01), attitudes toward the brand (Mrel.minority = 3.04 vs. Mrel.majority = 3.98; F(1, 332) = 50.66, p < .01), and purchase intention (Mrel.minority = 2.73 vs. Mrel.majority = 3.77; F(1, 332) = 33.01; p < .01). No effects of ethnicity or interaction effects were found (p > .10). Hypothesis 1 was supported for all dependent variables.

Mediation analysis (Hayes Citation2013, model 4) was conducted separately for each dependent variable with the bootstrapping method (5,000 resamples). We included the endorser’s religion (minority vs. majority) as the independent variable, sociomoral disgust as the mediator variable, and consumer response (attitudes toward the ad, attitudes toward the brand, purchase intention) as the dependent variables.

The results revealed a positive effect of religion on sociomoral disgust (β = .95, SE = .14, t(334) = 6.54, p < .01). Sociomoral disgust, in turn, was negatively related to attitudes toward the ad (β = −.14, SE = .05, t(333) = −3.06, p < .01). The indirect effect of the endorser’s religion on attitudes toward the ad via sociomoral disgust was statistically significant (β = −.13, SE = .05; 95% confidence interval [CI], −.24 to −.04). The same pattern of mediation analysis results was found for the additional aspects of consumer response (see ). No statistically significant mediation could be found for ethnicity (CIs included zero; see supplemental online Appendix 3). Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Table 1. Indirect and direct effects of endorser's religion via sociomoral disgust (study 1).

Study 2

The objective of this study was to test hypothesis 3, that is, the moderating effect of ethnic and religious identity on the indirect effects demonstrated in study 1. Because the hijab is a politically stigmatized symbol (Sandikci and Ger Citation2010), which has the potential to influence majority consumers’ responses, we eliminated this possible bias in study 2 and tested whether the findings of study 1 could be replicated and generalized by depicting a male endorser (rather than female) who promoted a service (rather than a good), with a different product category (fast food rather than cereals), and by communicating the endorser’s belongingness to a minority group verbally (rather than by visual cues).

Procedure and Design

We applied a three-factorial between-subjects design, manipulating religion (minority vs. majority endorser) and ethnicity (minority vs. majority endorser) and measuring participants’ ethnic and religious identity. Four print advertisements were created for a fictitious fast food restaurant “Best Grill” (see supplemental online Appendix 4). We used the same endorser across all four conditions. The endorser had fairly light skin, brown hair, and a short beard and could pass as either ethnic minority or majority in Germany and Israel where the study was conducted. The endorser’s religion and ethnicity were manipulated with verbal descriptions.

For the German sample, the ethnic minority endorser was presented as having Bosnian ethnic background. We chose this particular minority group because in Bosnia and Herzegovina, around 51% of the population is Islamic and around 46% of the population is Christian. Thus, Bosnians are not automatically associated with Islam. Other ethnic minorities such as Turks (99.8% Muslim), Syrians (87% Muslim), or Afghans (99.7% Muslim) are very likely to be associated with Islam (CIA Citation2021). While history and geopolitical events certainly may influence the responses to the endorser, the percentage of Bosnians applying for asylum is relatively low compared to other minorities (0.3% of all applications in 2018 and 0.4% in 2017) (BMI Citation2018). Therefore, this particular minority group is not the center of public discussions and is assumed to be less known than minorities such as Syrians or Turks, who are controversially discussed in public. For the Israeli sample, the endorser in the ad was also verbally described as affiliated with an ethnic minority.

Manipulations were pretested with 120 majority participants in Israel and 120 participants in Germany. We used the same questions as in study 1. A two-way ANOVA revealed that the ethnic minority endorser was more likely to be perceived as belonging to an ethnic minority in the ethnic minority compared to the ethnic majority condition (Germany: Methn.minority = 5.27 vs. Methn.majority = 4.05, F(1, 118) = 21.95, p < .01, α = .81; Israel: Methn.minority = 5.82 vs. Methn.majority = 2.60, F(1, 116) = 607.61, p < .01, α = .93). The religious minority endorser was more likely to be perceived as belonging to a religious minority in the religious minority compared to the religious majority condition (Germany: Mrel.minority = 5.31 vs. Mrel.majority = 2.15, F(1, 118) = 131.42, p < .01, α = .94; Israel: Mrel.minority = 5.45 vs. Mrel.majority = 1.98, F(1, 116) = 773.73, p < .01, α = .96). No statistically significant effects were found for attractiveness (for both countries, p > .10; α > .84). The pretest results indicated the manipulations were successful. Furthermore, ethnic identity (IDEth) and religious identity (IDRel) are statistically significantly higher in Israel than in Germany (IDEth: MIsrael = 4.63 vs. MGermany = 3.68, F(1, 286) = 35.31, p < .01; IDRel: MIsrael = 5.55 vs. MGermany = 3.26, F(1, 214) = 60.75, p < .01).

Participants

Participants were recruited via online research panels (Clickworker in Germany and iPanels in Israel). The total sample included 306 majority group participants (104 German, 202 Israeli). Participants were preselected as belonging to the ethnic majority group based on the definition by the German Federal Statistical Office by asking participants: “Do you have a migrant background? This means that you, your parents, or grandparents migrated from another country” (StBA Citation2021). This is in line with the operationalization of majority and minority status in previous studies (Van der Meer and Tolsma Citation2014). Israeli participants were all Jewish with no migration background. For the German sample, Christian participants and participants without a religious affiliation were included in the analysis, because they represent the German population (56% Christian, 39% no religious affiliation). Two people had to be excluded because they indicated Islam as their religion. In the Israeli sample, thirteen people had to be excluded because they did not pass the attention test, leaving a sample of 291 participants. The sample included 189 Israeli (Mage = 44.38, 46.56% female) and 102 Germans (Mage = 38.21, 45.10% female).

Measurements

The same dependent and mediator variables, manipulation assessment measurements, and demographic variables as in study 1 were used. In addition, we measured ethnic identity on a fourteen-item scale (e.g., “I am active in organizations or social groups that include mostly members of my own ethnic group,” “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .93) (Phinney Citation1992) and religious identity on a nine-item scale (e.g., “My Christian/Jewish identity is an important part of my self,” “I identify strongly with Christians/Jews”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .96) (Verkuyten Citation2007; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). As we created variation in ethnic and religious identities by sampling participants from two different countries, we included culture (0 = Israel, 1 = Germany) as a control variable.

Results

We ran an ANOVA with two factors (religion, ethnicity) controlling for culture (Israel vs. Germany) on the manipulation assessments and dependent variables (see supplemental online Appendix 5 for descriptive statistics). The endorser in the ethnic minority (compared to the ethnic majority) condition was more likely to be perceived as belonging to an ethnic minority (Methn.minority = 4.66 vs. Methn.majority = 4.01; F(1, 283) = 12.07; p < .01). The endorser in the religious minority (compared to the religious majority) condition was more likely to be perceived as belonging to a religious minority (Mrel.minority = 6.04 vs. Mrel.majority = 1.93; F(1, 283) = 567.79; p < .01). No other interaction or main effects were statistically significant. The results confirmed successful manipulations.

We found effects that replicated the results of study 1 and support hypothesis 1. Attitudes toward the ad (Mrel.minority = 3.84 vs. Mrel.majority = 4.63; F(1, 283) = 21.54; p < .01), attitudes toward the brand (Mrel.minority = 3.99 vs. Mrel.majority = 4.67; F(1, 283) = 15.41; p < .01; F(1, 283) = 15.41; p < .01), and purchase intention (Mrel.minority = 3.35 vs. Mrel.majority = 4.86; F(1, 883) = 46.79; p < .01) were higher for the ad that included the religious majority compared to the religious minority endorser. No other main or interaction effects were statistically significant (all p’s > .10).

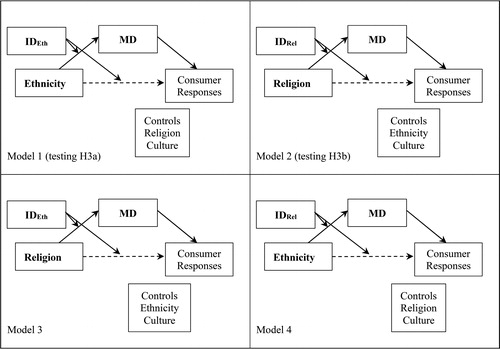

To test hypotheses 3a and 3b, moderated mediation analysis was conducted following the procedure outlined by Hayes (Citation2013, model 7). In total, we ran four models (see ) separately for each of the dependent variables. To test hypothesis 3a, we included ethnicity (minority vs. majority endorser) as the independent variable, ethnic identity as the moderator variable, and sociomoral disgust as the mediator variable, while holding religion (minority vs. majority) and culture constant (model 1). To test hypothesis 3b, we included religion as the independent variable, religious identity as the moderator variable, and sociomoral disgust as the mediator variable, while holding ethnicity and culture constant. Models 3 and 4, further explored whether the ethnic identities (or religious identities, respectively) of the participants also influenced their evaluation of religious (or ethnic, respectively) minorities while holding ethnicity (or religion, respectively) and culture constant. We ran additional analyses for models 3 and 4, including ethnic identity (model 3) and religious identity (model 4) as covariates. The results still hold true (see supplemental online Appendices 6–8).

The results (see ) revealed a statistically significant two-way interaction between ethnicity and ethnic identity, religion and religious identity, and religion and ethnic identity (models 1 to 3) on sociomoral disgust. No statistically significant interaction could be found for ethnicity and religious identity (model 4). Sociomoral disgust, in turn, negatively influenced consumer responses to the advertisement. That is, increasing levels of moral disgust led to lower attitudes toward the ad, attitudes toward the brand, and purchase intention.

Table 2. Results of moderated mediation analysis (study 2).

The index of moderated mediation for each of the models revealed a statistically significant moderated mediation for models 1 to 3 for all outcome variables (see ). No statistically significant moderated mediation could be found for model 4 (see ).

Table 3. Model 1: Conditional indirect effects of ethnicity on consumer response at different levels of ethnic identity (study 2).

Table 4. Model 2: Conditional indirect effects of religion on consumer response at different levels of religious identity (study 2).

Table 5. Model 3: Conditional indirect effects of religion on consumer response at different levels of ethnic identity (study 2).

Table 6. Model 4: Indices of partial moderated mediation: Indirect effects of ethnicity on consumer response at different levels of religious identity (study 2).

Model 1

When looking at the conditional indirect effect of ethnicity via sociomoral disgust at different levels of the moderator, results showed a positive conditional indirect effect for all response variables for low ethnic identifiers. That is, depicting an ethnic minority endorser decreased sociomoral disgust, which, in turn, decreased consumer responses when presented with an ethnic minority endorser. For medium ethnic identifiers, no statistically significant effects could be found (CIs included zero). For high ethnic identifiers, there was a statistically significant negative indirect effect on attitudes toward the ad and purchase intention. That is, depicting an ethnic minority endorser increased sociomoral disgust. Sociomoral disgust, in turn, negatively influenced attitudes toward the ad and purchase intention. No effects could be found for attitudes toward the brand (see ). Therefore, hypothesis 3a was only partially supported.

Model 2 and 3

When looking at the conditional indirect effect of religion via sociomoral disgust at different levels of religious identity (ethnic identity for model 3), results revealed statistically significant conditional indirect effects of religion via moral disgust for medium and high religious (ethnic) identifiers (see and ). That is, for participants with medium and high religious (ethnic) identity, depicting religious minority endorsers increased sociomoral disgust, which, in turn, negatively influenced all consumer response variables. No statistically significant effects could be found for low identifiers (CIs included zero). Thus, hypothesis 3b was supported.

Model 4

No statistically significant moderated mediation could be found for all dependent variables (see ).

To summarize, ethnic identity moderated the effects of ethnicity via sociomoral disgust on consumer responses. That is, for low ethnic identifiers, depicting an ethnic minority endorser led to lower sociomoral disgust, which, in turn, decreased consumer responses. For high ethnic identifiers, depicting an ethnic minority endorser increased sociomoral disgust, which, in turn, decreased attitudes toward the ad and purchase intention. No statistically significant effects could be found for medium ethnic identifiers.

Religious identity and ethnic identity moderated the effects of religion via sociomoral disgust on all consumer responses. In particular, when depicting a religious minority, for medium and high religious and ethnic identifiers, the endorser’s ethnicity increased sociomoral disgust, which, in turn, decreased advertising responses.

General Discussion

The results of study 1 and 2 reveal that depicting a religious minority endorser in advertising elicits moral disgust for majority consumers, which, in turn, mediates their response to advertising. The observed effects were moderated by ethnic and religious identity. Although the results for religious identity are in line with previous research, surprisingly, the effects were also moderated by ethnic identity. The salience of the Islamic endorsers might be an explanation. Although ethnicity is not necessarily salient, religious minorities are often highly visible. As previous research showed, ethnic identity and prejudice are correlated, especially against highly visible out-groups who are perceived as potential competitors and, therefore, pose a threat to the majority’s identity (Jackson Citation2002). In addition, religious minorities might be perceived as being incompatible with the majority culture (Zick, Küpper, and Hövermann Citation2011).

The absent main and interaction, as well as mediating, effects of ethnicity of the endorsers indicate the strong category dominance of religion. Furthermore, although we found moderated mediation when depicting an ethnic minority endorser in advertising, results revealed an opposite effect for low ethnic identifiers. Moreover, although we found a negative effect of ethnicity of the endorsers via sociomoral disgust, the effects could be observed only for a small number of respondents (high ethnic identifiers) and for two of the three consumer response variables.

Theoretical Implications

These findings contribute to theory in several ways. Theoretically, conceptualizing and empirically testing the differential effects of religion and ethnicity contribute to our understanding of the underlying psychological processes of consumer responses. The present research is the first attempt to test the differential effects of a minority endorser’s ethnicity and religion in advertising by isolating each individual effect. The results show that depicting ethnic and religious minorities generates different consumer responses to advertising. Although previous marketing research entangled religion and ethnicity (Butt and de Run Citation2011; Hirschman Citation1981; Rößner, Kämmerer, and Eisend Citation2017), the present research demonstrates that they vary by the resulting response. In particular, we found the strong category dominance of religion. That is, negative advertising responses to minority endorsers are more likely based on religious and not ethnic in-group–out-group evaluations. We also did not find an interaction between religion and ethnicity. This result is in line with previous research that found a category dominance of religion and pointed to two independent effects (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2010; Hewstone, Islam, and Judd Citation1993).

The present results extend the findings of El Hazzouri, Main, and Sinclair (Citation2019) by demonstrating that disgust as an underlying mechanism not only influences advertising responses to sexual minority endorsers but also can be extended to other minority groups who face public stigmatization. It seems that minority groups who violate majority consumers’ world views and moral truths activate negative emotions, which, in turn, influence advertising effectiveness. Social out-groups such as ethnic minorities who do not pose a threat to the majority consumers’ world views do not activate negative emotions and are equally effective in advertising.

This finding has implications for the depiction of minorities in advertising. Identity categories that are highly polarizing in public discussions are especially strong in generating negative responses. Contrary to the prevailing opinion, for other categories such as ethnicity, minority and majority endorsers are equally effective. This finding is also in line with recent studies that found ethnic minority endorsers generate similar or even more positive responses (Appiah Citation2007; Bragg et al. Citation2019).

Although Muslims serve as an example of a religious minority group who faces strong public controversy in Western countries, history shows that there have always been certain groups (e.g., Catholics, Jews, and Jehovah’s Witnesses) who have suffered discrimination because they were perceived as new and posed a threat to the majority’s religion or culture (Penning Citation2009). Thus, the present findings, though context-specific, can be generalized to similar contexts.

Furthermore, we showed that for the depiction of religious minority endorsers, religious identity and ethnic identity moderate the effects. In particular, the depiction of religious minorities in advertising does not automatically lead to moral disgust; it depends on the ethnic and religious identity of the majority. We showed that the majority of consumers—those with average and high ethnic identity and religious identity—have negative responses to the depiction of religious minorities, while negative reactions could be found only for a few response variables and for a small number of consumers—those with high ethnic identity—when depicting an ethnic minority endorser.

Although previous researchers found that religiosity is an important predictor of political tolerance for unpopular social groups (Gibson Citation2010), we showed that ethnic identity also plays a crucial role and should not be neglected in intergroup conflicts. Moreover, we introduced sociomoral disgust as the underlying mechanism leading to those negative evaluations of minorities. The results help us to gain a better understanding of how consumers respond to advertising featuring stigmatized (religious) minorities.

Practical Implications

These findings have practical implications for depicting minorities in advertising. The majority population seems to have become more accepting of different ethnicities, even with different levels of ethnic and religious identity. Thus, the risk of alienating majority consumers by including ethnic minorities in advertising no longer poses a risk. This has also a societal impact, as a more realistic depiction of the social environment in advertising can help to reduce prejudice and create more acceptance. Religion, on the contrary, is still a highly sensitive topic, and advertisers cautiously need to take the level of ethnic and religious identity in a country into account. The depiction of a religious minority endorser might not pose a risk for a secular country such as Germany, but practitioners should be cautious in countries with high levels of ethnic and religious identity. In those countries, the depiction of religious minorities can elicit moral disgust that transfers to the advertisement and brand. In this case, the safer choice for addressing minority consumers might be including endorsers who identify as part of an ethnic, but not religious, minority.

Limitations and Future Research

The present research has several limitations. It is a first attempt at distinguishing the effects of religion and ethnicity. To the best of our knowledge, this has never been done before in advertising research. This attempt is challenging because Islam, the religion that has been investigated in our study, is often linked to particular nationalities (e.g., Turkish, Syrian, Afghan) (Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). Selecting ethnic affiliations for our studies (a Black ethnic minority in Israel, a Bosnian ethnic minority in Germany), which are not immediately associated with Islam, might at least minimize the association between Islam and the minority endorser depicted in the ad.

Our research was conducted in European and Middle Eastern contexts. The reasons for and benefits that arise from this experimental approach have been explained above. Nevertheless, participant responses to certain religious and ethnic minority endorsers in advertising may vary depending on the specific cultural context. In particular, study 1 and 2 were conducted in a small Middle Eastern country, where the majority is Jewish second- or third-generation Israeli-born individuals (CBS Citation2020). Study 2 was conducted in a major Central European country with a Christian majority that originated in Germany (StBA Citation2021). Thus, the results might not be completely generalizable, and the strength of the effects might vary across contexts. Yet, as supported by the results, the general model and the direction of effects can be transferred to other social and advertising contexts.

Nonetheless, one may wonder to what extent the effects found in these studies hold true in other countries with different minority and majority religions, in less or more conservative cultures, and in different sociopolitical atmospheres and whether the focal objection-eliciting entity consists of a particular religious minority (e.g., Muslims in Germany), a particular religion (e.g., Islam), or religion in general. Further research can replicate our studies and test how the findings apply to other minority groups who face public stigmatization.

Another potential limitation of this research may stem from merely depicting the endorser in the advertisement as a religious minority. One may argue that participants may have interpreted the endorsers’ religious affiliations in additional manners that were not accounted for in our research, such as the endorsers’ national identities (e.g., Nigerian vs. Israeli), group identities (out-group vs. in-group), or level of conservatism (conservative vs. liberal). Future research can eliminate these potential confounding effects by measuring these variables and controlling for them.

Additionally, in study 1, we used a Black minority character. As racism against Black people can be observed worldwide, this is a factor that may have influenced our results. However, the results of study 2 indicate that the observed effects are due to religion and not ethnicity. Future research may test whether different racial minorities (i.e., Black vs. White Muslim) generate different consumer responses.

Finally, we included well-known symbols in our manipulations (i.e., the hijab and halal food) to indicate the religious affiliation of the endorsers. However, those symbols have sociopolitical connotations (Johnson, Thomas, and Grier Citation2017; Sandikci and Ger Citation2010), which in turn might have further affected responses. Thus, future research may include less stigmatized symbols such as prayer beads or prayer rugs, to test whether the results still hold true.

Supplemental Online Appendices

Download MS Word (593.1 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Rößner

Anna Rößner (MSc, European University Viadrina) is a PhD Candidate at European University Viadrina.

Yaniv Gvili

Yaniv Gvili (PhD, Temple University) is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Business Administration, Ono Academic College.

Martin Eisend

Martin Eisend (PhD, Free University Berlin) is a Professor of Marketing in the Faculty of Business Administration at European University Viadrina.

References

- Aaker, J. L., A. M. Brumbaugh, and S. A. Grier. 2000. “Nontarget Markets and Viewer Distinctiveness: The Impact of Target Marketing on Advertising Attitudes.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 9 (3):127–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP0903_1

- Adida, C., D. Laitin, and M. Valfort. 2010. “Identifying Barriers to Muslim Integration in France.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (52):22384–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015550107

- Adida, C., D. Laitin, and M. Valfort. 2015. “Religious Homophily in a Secular Country: Evidence from a Voting Game in France.” Economic Inquiry 53 (2):1187–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12192

- Appiah, O. 2007. “The Effectiveness of “Typical-User” Testimonial Advertisements on Black and White Browsers' Evaluations of Products on Commercial Websites: Do They Really Work?” Journal of Advertising Research 47 (1):14–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849907070031

- Bar-Tal, D. 1996. “Development of Social Categories and Stereotypes in Early Childhood: The Case of “the Arab” Concept Formation, Stereotype and Attitudes by Jewish Children in Israel.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 20 (3-4):341–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00023-5

- Beatty, K. M., and O. Walter. 1984. “Religious Preference and Practice: Reevaluating Their Impact on Political Tolerance.” Public Opinion Quarterly 48 (1B):318–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/48.1B.318

- Bedrik, A. V., I. P. Chernobrovkin, A. K. Degtyarev, A. V. Serikov, and N. A. Vyalykh. 2015. “The Management of Inter-Ethnic Relations in Germany and the United States: The Experience of the Theoretical Comprehension.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6 (4):87–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n4s4p87

- BMI (The Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community of Germany). 2018. “Migration Report 2018 (Migrationsbericht der Bundesregierung, Migrationsbericht 2018).” Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Forschung/Migrationsberichte/migrationsbericht-2018.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

- Borau, S., and J. Bonnefon. 2017. “The Advertising Performance of Non-Ideal Female Models as a Function of Viewers' Body Mass Index: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Two Competing Affective Pathways.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (3):457–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1135773

- Bower, A. B., and S. Landreth. 2001. “Is Beauty Best? Highly versus Normally Attractive Models in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 30 (1):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673627

- Bragg, M. A., A. N. Miller, D. A. Kalkstein, B. Elbel, and C. A. Roberto. 2019. “Evaluating the Influence of Racially Targeted Food and Beverage Advertisements on Black and White Adolescents' Perceptions and Preferences.” Appetite 140:41–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.05.001

- Brewer, M. B. 1979. “In-Group Bias in the Minimal Intergroup Situation: A Cognitive-Motivational Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 86 (2):307–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.307

- Brooke, S. L. 1993. “The Morality of Homosexuality.” Journal of Homosexuality 25 (4):77–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v25n04_06

- Butt, M. M., and E. C. de Run. 2011. “Do Target and Non-Target Ethnic Group Adolescents Process Advertisements Differently?” Australasian Marketing Journal 19 (2):77–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2010.12.001

- CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel). 2020. Population - Statistical Abstract of Israel 2020 - No.71. Jerusalem, Israel: Central Bureau of Statistics Israel.

- Choi, D. D., M. Poertner, and N. Sambanis. 2019. “Parochialism, Social Norms, and Discrimination against Immigrants.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (33):16274–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820146116

- CIA (Central Intelligence Agency USA). 2021. “The CIA World Fact Book: Field Listing.” Religions. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/religions.

- Commins, B., and J. Lockwood. 1978. “The Effects on Intergroup Relations of Mixing Roman Catholics and Protestants: An Experimental Investigation.” European Journal of Social Psychology 8 (3):383–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420080310

- Cottrell, C. A., and S. L. Neuberg. 2005. “Different Emotional Reactions to Different Groups: A Sociofunctional Threat-Based Approach to "prejudice".” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (5):770–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.770

- El Guindi, F. 1999. Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/9781847888969

- El Hazzouri, M., K. J. Main, and L. Sinclair. 2019. “Out of the Closet: When Moral Identity and Protestant Work Ethic Improve Attitudes toward Advertising Featuring Same-Sex Couples.” Journal of Advertising 48 (2):181–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1518736

- Fleischmann, F., L. Leszczensky, and S. Pink. 2019. “Identity Threat and Identity Multiplicity among Minority Youth: Longitudinal Relations of Perceived Discrimination with Ethnic, Religious, and National Identification in Germany.” The British Journal of Social Psychology 58 (4):971–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12324

- Forehand, M. R., and R. Deshpandé. 2001. “What we See Makes Us Who We Are: Priming Ethnic Self-Awareness and Advertising Response.” Journal of Marketing Research 38 (3):336–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.3.336.18871

- Franklin, E. 2014. “Are You Reaching the Black-American Consumer? How the Rise of US Multiculturalism Ended up Sending Mixed Marketing Messages.” Journal of Advertising Research 54 (3):259–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-54-3-259-262

- Galoni, C., G. S. Carpenter, and H. Rao. 2020. “Disgusted and Afraid: Consumer Choices under the Threat of Contagious Disease.” Journal of Consumer Research 47 (3):373–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa025

- Georgiou, M., and R. Zaborowski. 2017. “Media Coverage of the ‘Refugee Crisis’: A Cross-European Perspective.” Council of Europe report. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://edoc.coe.int/.

- Gibson, J. L. 2010. “The Political Consequences of Religiosity: Does Religion Always Cause Political Intolerance?” In Religion and Democracy in the United States: Danger or Opportunity, edited by A. Wolfe, and I. Katznelson, 147–75. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Greenbaum, R., J. Bonner, T. Gray, and M. Mawritz. 2020. “Moral Emotions: A Review and Research Agenda for Management Scholarship.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 41 (2):95–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2367

- Haidt, J., P. Rozin, C. McCauley, and S. Imada. 1997. “Body, Psyche, and Culture: The Relationship between Disgust and Morality.” Psychology and Developing Societies 9 (1):107–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2367

- Hameleers, M. 2019. “Putting Our Own People First: The Content and Effects of Online Right-Wing Populist Discourse Surrounding the European Refugee Crisis.” Mass Communication and Society 22 (6):804–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1655768

- Harper, J. 2018. “Katjes' Muslim Ads: Where's the Beef?” Accessed September 19, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/katjes-muslim-ads-wheres-the-beef/a-42643650.

- Hassan, S. H., and H. Harun. 2016. “Factors Influencing Fashion Consciousness in Hijab Fashion Consumption among Hijabistas.” Journal of Islamic Marketing 7 (4):476–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-10-2014-0064

- Hayes, A. F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Methodology in the Social Sciences. New York: Guilford Press.

- Helbling, M., and R. Traunmüller. 2020. “What is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ Feelings toward Ethnicity, Religion and Religiosity Using a Survey Experiment.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (3):811–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000054

- Hewstone, M., M. R. Islam, and C. M. Judd. 1993. “Models of Crossed Categorization and Intergroup Relations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64 (5):779–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.779

- Hirschman, E. C. 1981. “American Jewish Ethnicity: Its Relationship to Some Selected Aspects of Consumer Behavior.” Journal of Marketing 45 (3):102–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1251545

- Horberg, E. J., C. Oveis, D. Keltner, and A. B. Cohen. 2009. “Disgust and the Moralization of Purity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97 (6):963–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017423

- Jackson, J. W. 2002. “The Relationship between Group Identity and Intergroup Prejudice is Moderated by Sociostructural Variation.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32 (5):908–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00248.x

- Jacobson, J. 1997. “Religion and Ethnicity: Dual and Alternative Sources of Identity among Young British Pakistanis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 20 (2):238–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1997.9993960

- Johnson, G. D., K. D. Thomas, and S. A. Grier. 2017. “When the Burger Becomes Halal: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Privilege and Marketplace Inclusion.” Consumption Markets & Culture 20 (6):497–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2017.1323741

- Khan, N. J., M. A. Razzaque, and N. M. Hazrul. 2017. “Intention of and Commitment towards Purchasing Luxury Products: A Study of Muslim Consumers in Malaysia.” Journal of Islamic Marketing 8 (3):476–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-12-2015-0091

- Kimmerling, B. 2004. Migrants, Settlers, Natives, State and Society in Israel: Between Multiplicity of Cultures and Culture War. TelAviv, Israel: AmOved (in Hebrew).

- King, E. B., and A. S. Ahmad. 2010. “An Experimental Field Study of Interpersonal Discrimination toward Muslim Job Applicants.” Personnel Psychology 63 (4):881–906. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01199.x

- Lammers, P., L. M. Ullmann, and F. Fiebelkorn. 2019. “Acceptance of Insects as Food in Germany: Is It about Sensation Seeking, Sustainability Consciousness, or Food Disgust?” Food Quality and Preference 77:78–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.05.010

- Lewin-Epstein, N., and Y. Cohen. 2019. “Ethnic Origin and Identity in the Jewish Population of Israel.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (11):2118–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1492370

- Masson, C. N., and M. Verkuyten. 1993. “Prejudice, Ethnic Identity, Contact and Ethnic Group Preferences among Dutch Young Adolescents.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 23 (2):156–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01058.x

- Merino, S. M. 2010. “Religious Diversity in a “Christian Nation”: The Effects of Theological Exclusivity and Interreligious Contact on the Acceptance of Religious Diversity.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49 (2):231–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01506.x

- Mitchell, A. A., and J. C. Olson. 1981. “Are Product Attribute Beliefs the Only Mediator of Advertising Effects on Brand Attitude?” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (3):318–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3150973

- Moll, J., R. de Oliveira-Souza, F. T. Moll, F. A. Ignácio, I. E. Bramati, E. M. Caparelli-Dáquer, and P. J. Eslinger. 2005. “The Moral Affiliations of Disgust: A Functional MRI Study.” Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology: Official Journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology 18 (1):68–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnn.0000152236.46475.a7

- Morales, A. C., and G. J. Fitzsimons. 2007. “Product Contagion: Changing Consumer Evaluations through Physical Contact with “Disgusting” Products.” Journal of Marketing Research 44 (2):272–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.272

- Nike. 2017. “The Nike Pro Hijab Goes Global.” Nike, December 01. https://news.nike.com/news/nike-pro-hijab.

- Ohanian, R. 1990. “Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers' Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness.” Journal of Advertising 19 (3):39–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

- Penning, J. M. 2009. “Americans' Views of Muslims and Mormons: A Social Identity Theory Approach.” Politics and Religion 2 (2):277–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048309000236

- Phinney, J. S. 1992. “The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Diverse Groups.” Journal of Adolescent Research 7 (2):156–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/074355489272003

- Ritter, R. S., and J. L. Preston. 2011. “Gross Gods and Icky Atheism: Disgust Responses to Rejected Religious Beliefs.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (6):1225–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.006

- Rößner, A., M. Kämmerer, and M. Eisend. 2017. “Effects of Ethnic Advertising on Consumers of Minority and Majority Groups: The Moderating Effect of Humor.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (1):190–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1168907

- Rozin, P., J. Haidt, and K. Fincher. 2009. “Psychology. From Oral to Moral.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 323 (5918):1179–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170492

- Rozin, P., J. Haidt, and C. R. McCauley. 2008. “Disgust.” In Handbook of Emotions, edited by M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, and L. F. Barrett, 3rd ed., 757–76. New York: Guilford Press.

- Rozin, P., J. Haidt, C. McCauley, L. Dunlop, and M. Ashmore. 1999. “Individual Differences in Disgust Sensitivity: Comparisons and Evaluations of Paper-and-Pencil versus Behavioral Measures.” Journal of Research in Personality 33 (3):330–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1999.2251

- Rozin, P., L. Lowery, S. Imada, and J. Haidt. 1999. “The CAD Triad Hypothesis: A Mapping between Three Moral Emotions (Contempt, Anger, Disgust) and Three Moral Codes (Community, Autonomy, Divinity).” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (4):574–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.574

- Russell, C. A., D. Russell, A. Morales, and J. Lehu. 2017. “Hedonic Contamination of Entertainment: How Exposure to Advertising in Movies and Television Taints Subsequent Entertainment Experiences.” Journal of Advertising Research 57 (1):38–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2017-012

- Sandikci, Ö., and G. Ger. 2010. “Veiling in Style: How Does a Stigmatized Practice Become Fashionable?” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (1):15–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/649910

- Schnall, S., J. Haidt, G. L. Clore, and A. H. Jordan. 2008. “Disgust as Embodied Moral Judgment.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (8):1096–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208317771

- Sierra, J. J., M. R. Hyman, and R. S. Heiser. 2012. “Ethnic Identity in Advertising: A Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Promotion Management 18 (4):489–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2012.715123

- Smedley, A., and B. D. Smedley. 2005. “Race as Biology is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race.” The American Psychologist 60 (1):16–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16

- Song, M. 2020. “Rethinking Minority Status and ‘Visibility.” Comparative Migration Studies 8 (1):5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0162-2

- StBA (The Federal Statistical Office of Germany). 2021. “Population: Migration and Integration.” Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/Migration-Integration/_node.html

- Tajfel, H. 1978. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. London, UK: Academic Press.

- Tajfel, H., J. C. Turner, W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin and S. Worchel, Vol. 56, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Tal, A., Y. Gvili, M. Amar, and B. Wansink. 2017. “Can Political Cookies Leave a Bad Taste in One’s Mouth? Political Ideology Influences Taste.” European Journal of Marketing 51 (11/12):2175–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2015-0237

- Thomas, P., and P. Sanderson. 2011. “Unwilling Citizens? Muslim Young People and National Identity.” Sociology 45 (6):1028–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416161

- Tybur, J. M., D. Lieberman, and V. Griskevicius. 2009. “Microbes, Mating, and Morality: Individual Differences in Three Functional Domains of Disgust.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97 (1):103–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015474

- Van der Meer, T., and J. Tolsma. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity and Its Effects on Social Cohesion.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (1):459–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043309

- Verkuyten, M. 2007. “Religious Group Identification and Inter-Religious Relations: A Study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 10 (3):341–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207078695

- Verkuyten, M., and A. A. Yildiz. 2007. “National (Dis)identification and Ethnic and Religious Identity: A Study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 33 (10):1448–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207304276

- Warren, C., E. P. Carter, and A. P. McGraw. 2019. “Being Funny Is Not Enough: The Influence of Perceived Humor and Negative Emotional Reactions on Brand Attitudes.” International Journal of Advertising 38 (7):1025–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1620090

- Witte, N. 2018. “Responses to Stigmatisation and Boundary Making: Destigmatisation Strategies of Turks in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (9):1425–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1398077

- Zick, A., B. Küpper, and A. Hövermann. 2011. Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination - A European Report. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.