Abstract

This research investigates the effect of narcissism on consumers’ affective reaction to advertising. Narcissists are burdened with the duality of the overinflated self-view and the vulnerability of the unrealistic ego. They tend to be paranoid of the mere introspection of self-image, because such introspection can expose the vulnerability they have been diligent to avoid. Therefore, ads that are closely relevant to the viewer’s self-image can lead to a negative affective response. Several experiments show support for this hypothesis and illustrate implications for advertising practice. Taking into consideration reports that narcissism is on the rise within the population, promotional ads that expect to encounter narcissistic consumers should consider the appeal relevant to self-image with caution, while preventive ads, such as those based on fear appeal, can benefit from enhanced relevance to this audience.

Popular media seems to confirm that narcissism is on the rise in U.S. society in recent years (Quenqua Citation2013). Emerging studies suggest this trend is related to the proliferation of social media in terms of extent of usage, frequency of posting, and number of friends/followers (see McCain and Campbell Citation2018). The current research investigates whether the rise of narcissism in this selfie-touting age (Shane-Simpson et al. Citation2020; Sorokowski et al. Citation2015; Fox et al. Citation2018) affects how consumers respond to advertising. This study extends our understanding of this issue by focusing on narcissism’s effect on consumers’ affective reaction to ads.

A number of extant studies have explored the effect of narcissism on advertising, particularly related to the use of social media. The effort so far has largely focused on content creators on social media (i.e., selfie posters), providing insights into how social approval motivates narcissistic individuals to create postings but also leads to emotional fatigue (Fox et al. Citation2018; Nash, Johansson, and Yogeeswaran Citation2019). It is important to note that members of the “me me me” generation—not only those who create postings on social media but also the interactive audience which consumes such content that promotes self-centeredness—can potentially fall under the influence of narcissism (Andreassen, Pallesen, and Griffiths Citation2017; Davenport et al. Citation2014; Barry and McDougall Citation2018; Leung Citation2013). The current research explores how a general audience, not necessarily content generators, responds to advertising as a function of elevated narcissism. In particular, this investigation focuses on the consumer affective response to advertising. A large body of literature has addressed the central role of consumer attitudinal and emotional reactions in achieving advertising effectiveness (Batra and Ray Citation1986; Mehta Citation2000; Messmer Citation1979; Stout and Leckenby Citation1986). More recent studies have explored a wide range of sensory inputs implemented in advertisements, including imagery, music, and sense of touch, to elicit consumer affective reactions (Chowdhury, Olsen, and Pracejus Citation2008; Oakes and North Citation2006; Peck and Wiggins Citation2006). Given both the rise of narcissism in the general consumer population, especially in the online environment, and the ever-growing investment in affective advertising, it is vital that advertisers examine how these factors interact with one another.

To this end, the current research reviews the relevant literature regarding narcissism, particularly its impact on affect regulation. The extant literature shows that narcissists typically exhibit a sense of vulnerability, which leads to outbursts of negative emotions. In addition, a collection of empirical studies provides a foundation for the hypothesis that the degree to which narcissistic individuals experience negative affect depends on the relevance of the ad material to their self-images. Four experiments were carried out to confirm this hypothesis, demonstrate its application in the advertising context, and showcase the psychological process that drives this phenomenon.

Theoretical Framework

Narcissism is a system of social, cognitive, and affective processes aimed at maintaining one’s overinflated self-view, which features the duality of a grandiose self-view and a fragile ego (Morf and Rhodewalt Citation2001; McCain and Campbell Citation2018; Campbell, Rudich, and Sedikides Citation2002).

One of the better-known facets of narcissism is that narcissistic individuals tend to have an overinflated self-view, and their behaviors are primarily driven by the motivation to uphold this self-view (John et al. Citation1994; Campbell et al. Citation2000; Farwell and Wohlwend-Lloyd 1998; Campbell and Foster Citation2007). Narcissistic individuals tend to adopt this approach-driven mindset. They are motivated by the prospect of rewards rather than the avoidance of punishment in their decision making (Foster and Brennan Citation2011). This is probably because narcissists are constantly in search of evidence that can be used to prop up their grandiose self-view. This mindset manifests in social interactions in which narcissists are less likely to be shy and instead seem exceedingly charming at their first encounters with strangers (Back, Schmukle, and Egloff Citation2010; Back et al. Citation2013). Narcissists also tend to be aggressive with their investment decisions, leading them to be more successful in the bull market of stocks and fare worse in the bear market (Foster and Brennan Citation2011; Baumeister and Vohs Citation2001). In other cases, it has been reported that narcissistic chief executive officers drive greater rebound of firm performance after crises due to their aggressive approaches (Patel and Cooper Citation2014). In the context of consumer behavior, it has been documented that narcissistic consumers prefer customizable products to products of standard mass production due to the sense of uniqueness and superiority (de Bellis et al. Citation2016). Again, although varying in specific contexts, these behaviors all serve narcissists’ insatiable desire to affirm their grandiose self-views, whereas the actual manifestations such as social popularity or financial abundance are merely means to the goal of self-aggrandization and, in some cases, happy by-products (Farwell and Wohlwend-Lloyd 1998; Campbell and Foster Citation2007).

However, it is important to address the vulnerability side of the narcissistic process as part of the thesis of the current research. Despite narcissists’ seemingly inexhaustible effort to uphold the sense of grandiosity, they are also constantly threatened by vulnerability in their sense of self-worth, arguably because their overly aggrandized self-view is unrealistic and unsustainable (Morf and Rhodewalt Citation2001; Wink Citation1991). Some scholars even describe narcissism as a dynamic process akin to addiction (Baumeister and Vohs Citation2001). Doubt about their self-worth perpetually lingers within narcissists. Moments of indulgence in boasting can temporarily relieve but not permanently satiate the ever-growing need for self-reassurance.

The advertising literature has consistently emphasized the central role of affect management in the effectiveness of advertising (Chowdhury, Olsen, and Pracejus Citation2008; Poels and Dewitte Citation2006; Hartmann, Apaolaza, and Eisend Citation2016; Bülbül and Menon Citation2010). To this end, the current research focuses on the implications of inherent vulnerability associated with narcissism on affect management. It has been reported that vulnerable narcissists generally experience elevated anger, neuroticism, and overall bad mood, independent of their circumstances (Maciantowicz and Zajenkowski Citation2021). This phenomenon stems directly from the fact that narcissists struggle from a self-concept that is not clearly defined but rather constantly toggles between grandiose and vulnerable states (Stucke and Sporer Citation2002). Understandably, narcissists are sensitive to negative feedback that contradicts the grandiose self-images they strive to build. Numerous accounts have recorded that narcissists display frustration and anger in the event of failure, regardless of whether such failure can be attributed to their individual actions or are purely incidental (Besser and Priel Citation2010; Rhodewalt and Morf Citation1998). It has also been cited that narcissists resort to aggression when their romantic pursuits are met with rejection (Besser and Priel Citation2009; Bushman et al. Citation2003).

Moreover, evidence seems to converge on the likelihood that narcissists experience distress not only with events that explicitly contradict their grandiose self-images but also with many kinds of stimuli that merely implicate introspection or a reflection of self-worth. For example, in comparison to nonnarcissists, narcissists experience greater instability of self-esteem following social interactions. Despite narcissists’ tendency to report beliefs of being the most influential person during social interactions, they also perceive such interactions as less pleasant or satisfying (Rhodewalt, Madrian, and Cheney Citation1998) than nonnarcissists. This phenomenon has roots in the paradox that although narcissists are eager to use social interactions as a means to obtain affirmation to their positive self-views, the feedback they seek is ultimately controlled by other parties during the interaction. Consistent with this logic, more recent studies have found that narcissists are quick to fixate on words that imply evaluation or judgment (e.g., welcome, ignored) from a pool of words that also include those that are nonevaluative and nonjudgmental (e.g., floor, coat). This effect is particularly pronounced with words that project criticism or negative evaluation (Krusemark, Lee, and Newman Citation2015; Horvath and Morf Citation2009; Gu, He, and Zhao Citation2013). Another review suggests that students exhibiting higher levels of narcissism tend to prefer simplicity in information processing to address systematic complexity to preempt the chance of experiencing the frustration of failure (Hoover Citation2011). In fact, narcissists who are prone to vulnerability experience negative emotions when they expect opportunities for feedback and try to avoid actually receiving this feedback (Atlas and Them Citation2008). A summary of the studies reviewed so far suggests the likelihood that narcissists, who are burdened with the duality of the overinflated self-view and the vulnerability of the unrealistic ego, are paranoid of the mere introspection of self-image, as such introspection could result in feedback that contradicts the state of the ego that they labor so diligently to protect.

In the context of advertising, scholars and practitioners alike have seen the value of personal relevance in terms of transforming consumer attitude (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1981). Especially in the discussion of advertising in the age of social media, personal relevance has been identified as a key factor that influences the effectiveness of advertisements (Morris, Choi, and Ju Citation2016; Hayes et al. Citation2020). However, given the discussion so far, one can expect that personal relevance will lead to unintended results among a narcissistic audience. Specifically, personally relevant messages have the potential to lead to insights regarding the self that are contradictory to the ego-building effort of the narcissist. Thus, the current research hypothesizes that ads featuring personally relevant appeals will lead to negative affective reactions from narcissists. A set of experiments was carried out to test this hypothesis. Experiment 1 demonstrates that social media advertising with personally relevant messaging indeed leads to negative brand attitude in an audience primed with narcissism. Experiment 2 identifies a threat to self-image as the underlying process that causes narcissists’ negative affective reaction. Experiments 3(a) and 3(b) showcase the application of the current findings with the example of fear appeal advertising about the harms of tobacco use.

Overview of Methodology

As reviewed so far, narcissism has been construed as a stable personality trait in most extant literature. Accordingly, it is primarily operationalized as a measurement by a variant of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Gentile et al. Citation2013; Raskin and Terry Citation1988; Foster and Brennan Citation2011). However, while there is interpersonal difference in terms of narcissistic tendencies, longitudinal studies have provided compelling evidence of within-person variablity of narcissim in response to daily events and other psychological states (Giacomin and Jordan Citation2016a, Citation2016b). In particular, promoting concerns regarding one’s agentic qualities (e.g., skills, competence) enhances one’s narcissistic tendencies, whereas promoting concerns regarding communal qualities (e.g., nurturance, empathy) suppresses the narcissistic tendency as a personal state (Giacomin and Jordan Citation2014). These findings provide a novel opportunity to experimentally test the impact of narcissism on other behavioral dispositions. As a pioneer in the field of marketing and advertising to systematically investigate the effects of narcissism, de Bellis et al. (Citation2016) first presented a study in which narcissism was measured as a between-subject trait. Then, two lab experiments manipulated the narcissism factor using the agentic-versus-communal priming method, and a postmanipulation test confirmed the difference in state narcissism to be statistically significant across treatment groups. This experiment yielded results of the downstream effect that were consistent with the findings from the first study. The current research follows the empirical philosophy of de Bellis et al. (Citation2016) and adopts a hybrid method in the operationalization of the narcissism construct. Also, as the identification of a causal relationship is the key object, three lab experiments adopted the priming method as manipualtion for personal state narcissim, and the results are then validated by a replication in which narcissism is measured as an interpersonal trait.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was carried out to test the hypothesis that self-relevant messaging in advertising causes negative attitudinal reactions from individuals primed with narcissism. The design was set in the context of a social media ad for a fictitious athletic apparel brand, with female participants in an online survey panel as the test population. Over the years, numerous studies across cultures have identified that women closely associate their body images with their self-esteem (Jung and Lee Citation2006; Lowery et al. Citation2005). The proliferation of social media and the selfie-posting trends have accentuated emphasis on body images, particularly among younger women, and has likely taken a toll on this population’s emotional well-being (Veldhuis et al. Citation2020; Mills et al. Citation2018). Insights from this experiment could be helpful to guide practitioners as they navigate the field of social media advertising.

Experiment Procedure

In this experiment 193 female participants from the United States (Mage = 32.70, SD = 6.14) were recruited from the online survey panel CloudResearch (https://www.cloudresearch.com/), which maintains a pool of survey participants with demographic filters. The experiment used a 2 (narcissism priming: yes versus no) × 2 (self-image relevance: high versus low) between-subject design.

Participants were asked to examine and provide feedback to a social media ad in the form of an Instagram posting by a fictitious athletic apparel brand that produces women’s loungewear with the specific functions of correcting and enforcing one’s body postures.

The ad posting presented to the participants was in a two-page design. The narcissism factor was manipulated with the design elements embedded in the first page (see Appendix 1). Extant research has revealed that a focus on self-concerns (i.e., agentic concerns) temporarily elicits a narcissistic mentality, whereas focus on communal concerns reduces narcissistic tendencies (de Bellis et al. Citation2016; Giacomin and Jordan Citation2014). Two versions of ad design were created according to these findings, both in the theme of women’s self-betterment. The participants that were randomly assigned to the narcissism-priming condition (n = 97) were presented with an ad design that featured an image of a woman running alone, along with the slogan “I can.” The caption below the ad image described a story about a woman defying doubts and achieving athletic improvements on her own. In contrast, participants assigned to the nonnarcissism condition (n = 96) were presented with an ad design that depicted a group of women of various ages running together, with the slogan “Together, we can do this.” The caption below the image described a story of a woman achieving athletic improvement with the support and encouragement of friends and family. Participants in both conditions reviewed their assigned ads and provided feedback in terms of art design and messaging.

The self-image relevance factor was manipulated using the material presented on the second page of the ad. Both versions of the design for the second page showed a woman in business attire standing with good posture and a confident smile. The high self-image relevance version of the design featured the slogan “Showing the best of me,” and the caption below discussed how the apparel brand helps women present a better body image (n = 95). The low self-image relevance version of the design featured the slogan “Great posture brings great energy,” and the caption below suggested that the apparel brand helps customers improve their daily energy level by improving their posture (n = 98). As with the first page ad design, the experiment participants provided feedback regarding their assigned versions of the second page ad design.

Both pages of the ad posting were then presented to the participants in a side-by-side view. Participants reported their overall affective impression of the ad on a 7-point scale, with 1 being Not pleasant and 7 being Very pleasant (Homer and Yoon Citation1992; Chowdhury, Olsen, and Pracejus Citation2008). Next, all participants answered the 13-question version of the NPI (NPI-13) (Gentile et al. Citation2013) as a manipulation check for the narcissism priming procedure. Finally, all participants rated how relevant each of two factors, body image and daily energy level, was to their sense of self-image on a 7-point scale.

Results and Discussion

The composite scores from the NPI-13 were first analyzed to confirm that the first page of the Instagram ad was effective at producing a difference in terms of state narcissism across the two conditions. A statistically significant difference was confirmed (Mnarcissistic = 3.12, SD = 2.19; Mnonnarcissistic = 2.46, SD = 2.44; t (191) = 2.00, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .29). The ratings of self-image relevance regarding both body image and daily energy were also analyzed using a repeated-measures mixed model (rating of topical issue: body image versus daily energy, within-subject; actual assignment of ad design condition: body image versus daily energy, between-subject). The results showed that, overall, participants viewed body images to be more relevant than daily energy to self-image (Mbody image = 5.72, SD = 1.29; Mdaily energy = 5.28, SD = 1.42; F (1, 191) = 13.26, p < .01, partial η2 = .07). Participants’ actual assignment to the ad conditions did not introduce a confounding element in this difference (Finteraction (1, 191) = .56, n.s.).

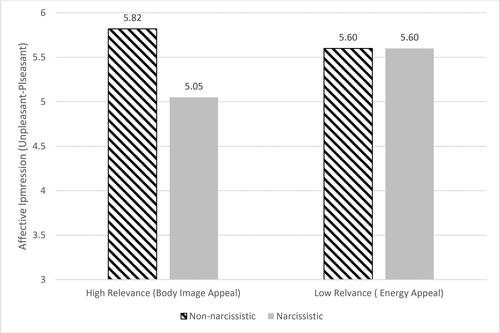

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was used to analyze the effect of various ad design elements on participants’ affective impression of the brand, and an interaction between the narcissism factor and the self-image relevance factor was revealed (F (1, 189) = 4.32, p < .05; see ). Specifically, participants primed with narcissism rated the ad with higher relevance to self-image (i.e., body image) as less pleasant than the ad with lower relevance to self-image (i.e., daily energy) (Mbody image = 5.05, SD = 1.62; Mdaily energy = 5.60, SD = 1.30; F (1, 189) = 4.40, p < .05, partial η2 = .02). This difference was not observed in participants in the nonnarcissistic condition (Mbody image = 5.82, SD = 1.01; Mdaily energy = 5.60, SD = 1.17; F (1, 189) = .71, n.s.). From another perspective, when the ad used an appeal that was more relevant to self-image, it was not as well received by participants primed with narcissism as it was by their counterparts in the control condition (Mnarcissistic = 5.05, Mnonnarcissistic = 5.82; F (1, 189) = 8.43, p < .01, partial η2 = .04). However, the ad with the appeal that was less relevant to self-image received comparable affective responses across participants in both conditions (Mnarcissistic = 5.60, Mnonnarcissistic = 5.60; F (1, 189) = .00, n.s.).

Figure 1. Brand affective impression as a function of narcissistic priming and ad relevance to self-worth.

These results showed that, contrary to popular belief, ads with high relevance to self-image were not effective at enhancing brand impression with an audience with an elevated narcissistic mindset. As discussed earlier, this phenomenon was likely driven by the fact that narcissists usually feel insecure about their self-images and thus dislike exposure to messaging that has the mere potential of yielding insights that are unfavorable to their ego-building effort. Experiment 2 was designed to provide further direct support for this account of their psychological processes. Meanwhile, from a practical perspective, advertisers should apply caution when designing ads if they expect the audience to be particularly susceptible to the influence of narcissism, as the time-tested practice of relevance appeal could backfire in this case.

Experiment 2

The focus of Experiment 2 was to demonstrate the underlying process of the phenomenon uncovered so far, which is that individuals primed with narcissism exhibit negative affective reactions when they are exposed to material relevant to their self-images.

Pretest of Manipulation Procedures

The priming procedures for the narcissism factor followed the same logic as the one used in Experiment 1: that soliciting communal thinking suppresses narcissistic tendencies, whereas eliciting agentic thinking elevates these tendencies (de Bellis et al. Citation2016; Giacomin and Jordan Citation2014). Here, 97 participants were recruited from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) panel for a pretest of the narcissism priming procedure. The data collection process here and in subsequent experiments followed guidelines for best practice at the Journal of Advertising (Ford Citation2017). Approximately half of the participants (n = 52) were randomly assigned to the narcissistic state condition and were asked to select and describe their own merits that would make them stand out from their peers. The rest of the participants (n = 45) were assigned to the nonnarcissistic condition and were asked to describe an event during which others had helped them feel welcome or accepted. All participants then completed the NPI-13. A comparison between the composite NPI scores from the two groups revealed that the priming procedures did produce a differential in the narcissistic mentality as intended (Mnarcissistic = 4.37, SD = 2.98; Mnonnarcissistic = 3.29, SD = 2.05; t (95) = 2.04, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .42).

The measure for affective reaction was to be operationalized using perceptions of taste. Prior consumer research established that the intensity of taste perception can be used as a proxy measure for affective responsiveness (Xu and Labroo Citation2014). In particular, sour taste is correlated with negative emotions (Noel and Dando Citation2015). A separate pretest was carried out to confirm the validity of using the perception of sour taste as a proxy for an affective reaction when the food was presented only as imagery but not actually consumed by the survey participants. In this pretest, 117 university students participated in the online study in exchange for course credit. Approximately half of the participants (n = 64) were randomly assigned to the negative emotions group and were asked to review a set of images that were known to elicit positive affects (pictures 1440, 1750, 2360, 2510, and 5000) from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, and Cuthbert Citation2008). The other half of the participants (n = 53) reviewed images that were known to elicit negative affect (pictures 2205, 2900, 6311, 9330, and 9927). Then, all participants were shown a picture of a jar of dill pickles and were asked to assess how salty and sour the pickles would taste on a 7-point scale, with 7 being Very intense flavor. A repeated-measures model analyzed the response and revealed an interaction between the affect conditions and the salty-versus-sour taste perceptions (F (1, 115) = 4.57, p < .05). Specifically, participants in the negative affect condition reported the sour taste to be more intense than perceived by those in the positive affect condition (Mnegative affect = 5.11, SD = 1.20; Mpositive affect = 4.53, SD = 1.46; F (1, 115) = 5.59, p < .05, partial η2 = .05). In contrast, participants in both groups reported comparable perceptions of salty taste intensity (Mnegative affect = 4.64, SD = 1.38; Mpositive affect = 4.70, SD = 1.45; F (1, 115) = .05, n.s.). Thus, it was confirmed that sour taste perception in particular was a valid proxy for negative affect.

Main Experiment Procedure

Next, 245 participants (123 females, Mage = 38.67) were recruited from MTurk panel for the main experiment. The experiment used a 2 (narcissism priming: yes versus no) × 2 (self-image relevance: yes versus no) between-subject design.

The narcissism factor was primed using the agentic-versus-communal priming procedure identical to the one used in the pretest (nnarcissistic = 133; nnonnarcissistic = 112). Then, the participants who were randomly assigned to the high self-image relevance condition (n = 116) were asked to describe an instance in their lives during which they experienced failure despite their best effort and mainly due to bad luck, as narcissists are known to construe threats to their self-worth from incidental failures (Farwell and Wohlwend-Lloyd 1998; Rhodewalt and Morf Citation1998). Participants in the control group (n = 129) answered unrelated filler questions that took a similar amount of time.

Finally, all participants were presented with the packaging of a novelty product, Lay’s lime-flavored potato chips, and were asked to estimate “how tangy the product would taste” on a 7-point scale, with 1 being Not tangy at all. As seen in the pretest results, perception of sour flavor intensity served as a proxy for negative affect.

Results and Discussion

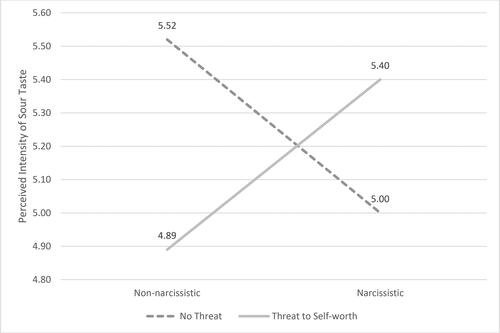

Participants’ estimation of sour flavor intensity was analyzed as a function of the narcissism priming factor and the self-worth relevance factor. An ANOVA revealed that there was an interaction between the two factors (F (1, 241) = 9.88, p < .01; see ). Specifically, in the low-relevance condition, those who were primed with narcissism perceived the product to be less tangy than those who were not primed with narcissism (Mnarcissistic = 5.00, SD = 1.37; Mnonnarcissistic = 5.52, SD = 1.16; F (1, 241) = 5.28, p < .05, partial η2 = .02). However, in the condition in which participants were asked to recall incidental failures, those who were primed with narcissism estimated the product to be tangier than their counterparts without the priming (Mnarcissistic = 5.40, SD = 1.12; Mnonnarcissistic = 4.89, SD = 1.37; F (1, 241) = 4.63, p < .05, partial η2 = .02). The drastic contrast of sour taste perception, as a proxy for negative affect, was consistent with the hypothesis that narcissism leads to negative affect when individuals are exposed to material that can imply relevance to their self-images.

Figure 2. Perception of sour taste intensity as a function of narcissistic priming and presence of threat to self-worth.

The results from Experiment 2 illustrated the psychological process underlying the phenomenon seen in the first experiment: (1) the change in attitude of the narcissist occurred in reaction to the material that posed a threat to self-image, and (2) the reaction observed so far was rooted in affect management. Building upon these findings, further empirical investigation was carried out to extend the external validity and practical implications of the current research.

Experiment 3(a)

Whereas Experiment 1 illustrated the hazard of using an advertising appeal relevant to self-image with a narcissistic audience, and Experiment 2 validated the underlying psychological process of the phenomenon, Experiment 3 was designed to expand the application of the findings so far to the context of fear appeals, where narcissists’ affective aversion to cues relevant to self-image might enhance the effectiveness of the ads.

Procedure

In Experiment 3(a), 143 participants (65 females, Mage = 37.76) from MTurk participated, which used a 2 (narcissism priming: yes versus no, between-subject) × 2 (self-image relevance: high versus low, within-subject) mixed design.

The narcissism factor was operationalized using the same procedure as in the previous experiments (nnarcissistic = 73; nnonnarcissistic = 70). Then, all participants were presented with a series of six images allegedly designed for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s anti-smoking campaign (see Appendix 2). Three images were in black and white, depicting gloomy alleyways with rain puddles, and including the following sentence: “The world loses its color when you smoke.” The other three pictures were in full color and depicted models with sad facial expressions and body language, with the following caption: “Smoking worsens sadness and depression.” According to the theorization and empirical results so far, narcissism’s affective reactions to ads depend on the perceived relevance to self-image. Therefore, it was expected that those primed with a narcissistic mindset would have more negative reactions to the images directly depicting people being vulnerable than to those images depicting depressing street scenes, whereas this contrast would not be expected of those not primed with narcissism. These images were displayed one at a time in random order, and participants were asked to rate how each image made them feel on a 7-point scale, with 1 being Very negative, 4 being Neutral, and 7 being Very positive.

Results

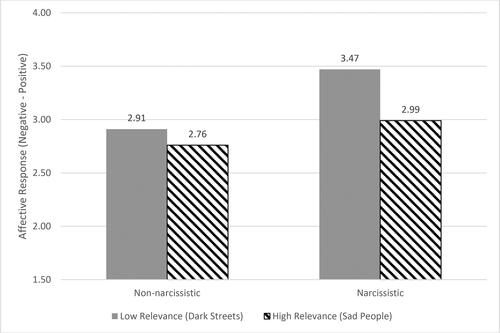

Participants’ affective reaction to the images were analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis with a 2 (narcissism priming: yes versus no, between-subject) × 2 (threat to self-worth: high versus low, within-subject) by three (image iterations: within-subject) model specification. Comparing the average ratings across three images in respective groups revealed an interaction between the narcissism factor and the self-image relevance factor (i.e., street scene versus sad people) (F (1, 141) = 4.89, p < .05; see ). Specifically, participants primed with narcissism reported that they viewed pictures of sad people with more negative feelings than they viewed pictures of depressing street scenes (Mpeople = 2.99, SD = 1.65; Mstreet = 3.47, SD = 1.52; F (1, 141) = 22.10, p < .01, partial η2 = .14). This difference was not detected in the reports by those in the control condition (Mpeople = 2.76, SD = 1.43; Mstreet = 2.91, SD = 1.45; F (1, 141) = 2.28, n.s.). From another perspective, images of sad people were similarly effective at evoking a negative affective response from participants with or without the narcissism priming (Mnarcissistic = 2.99, Mnonnarcissistic = 2.76; F (1, 141) = .78, n.s.). However, participants primed with narcissism reported fewer negative responses to images of depressing street scenes than those without the priming (Mnarcissistic = 3.47, Mnonnarcissistic = 2.91; F (1, 141) = 4.91, p < .05, partial η2 = .03).

Figure 3. Affective response to ads as a function of narcissistic priming and relevance to self-worth.

Thus, the results from Experiment 3(a) provided further evidence that relevance to self-image was a key moderator in narcissists’ reactions to advertisements. More importantly, this experiment shows that given the appropriate design the effect uncovered in the current research could be applied to enhance ad effectiveness, particularly in the context of preventive ads. Experiment 3(b) sought to replicate these results but with some adjustments to further extend the external validity and practical implications.

Experiment 3(b)

Experiment 3(b) was intended to further extend the external validity of the findings so far. Whereas in Experiment 3(a) the participants rated their affective reaction to each of the images per se, the current experiment measured the overall attitude toward the objective of the advertisement (i.e., smoking) after the participants finished viewing all of the assigned images. Also, instead of using a within-subject manipulation for the factor of self-worth relevance, Experiment 3(b) adopted a between-subject design. Specifically, a participant would see either images of depressing street scenes or images of sad people but not both types. Finally, instead of being primed as a situational factor as seen in the previous experiments, narcissism was measured as a chronic personality trait in Experiment 3(b).

Procedure

Here, 203 participants (109 females, Mage = 40.38) recruited from MTurk participated in this experiment, which used a one-factor, between-subject design (relevance to self-image: high versus low). The same cover story from Experiment 3(a) was used. The same mock ad designs were retained from Experiment 3(a) as well, but instead of rating all six images every participant viewed only three images of either sad people or depressing street scenes, depending on random assignment to the self-worth threat conditions. The images were presented one at a time in random order. Participants were not asked to rate each of the images as they were shown but rated how much they agreed with the general statement “Smoking may affect a person’s mental condition” on a 7-point scale after viewing all three images. Finally, participants answered the same questions from the NPI-13 as used in the narcissism priming pretest, which now served as the measure of chronic narcissistic tendency, as no situational priming of narcissism was used in the current experiment.

Results

A linear regression analysis was carried out, with the composite score of the NPI-13 (see for distribution), a binary variable representing the relevance to self-worth (0 = low relevance, 1 = high relevance) and the interaction between these two factors as independent variables (see ). The results showed that for those who viewed the images of a depressing street scene (i.e., low relevance to self-image), the ads’ aggregate effectiveness was negatively related to chronic narcissistic tendency (βNPI = − .13, t (199) = −2.29, p < .05). A person who scored higher on the NPI-13 would likely show a weaker response to this type of picture than those who scored lower on the NPI. However, for those who viewed the images of sad people (i.e., higher relevance to self-image), there was evidence that this trend was mitigated (βinteraction = .19, t (199) = 2.56, p < .05).

Table 1. Distribution of composite Narcissistic Personality Inventory score in Experiment 3(b).

Table 2. Linear regression output from Experiment 3(b).

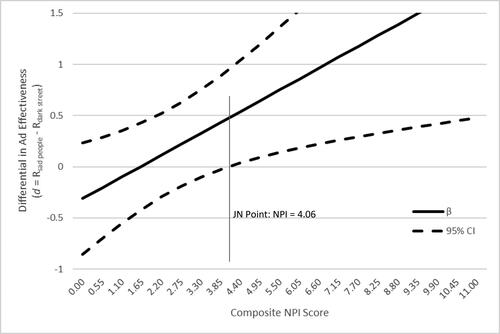

To better illustrate the practical implications of these findings, a Johnson–Neyman analysis (Spiller et al. Citation2013; Krishna Citation2016) was also carried out with image type as the focal predictor (see ). As seen from the results, participants with higher narcissistic tendencies (Johnson–Neyman point: composite NPI ≥ 4.06) differed in their overall attitude toward smoking, depending on the type of ad images they viewed. For them (n = 45), images of sad people elicited stronger responses than images of street scenes. However, this contrast was not observed in participants with narcissistic tendencies below the threshold.

Figure 4. Differential in effectiveness of ads using different fear appeals as a function of measured trait narcissism.

Overall, in contrast to the implications from Experiment 1, narcissistic individuals showed a bias in their response to ads featuring fear appeals, qualified by the perceived relevance of the ads to self-image. This is because, unlike promotional ads, fear-appeal ads’ effectiveness relies on the intensity of negative affect. More negative affect elicited by a fear-appeal ad implies higher effectiveness. In the case of the current experiment, material with higher self-relevance could yield better results if certain levels of consumer narcissism are expected.

General Discussion

Narcissism plays an increasingly important role in modern society (Twenge and Campbell Citation2009; Quenqua Citation2013), possibly due at least in part to the proliferation of social media platforms (Shane-Simpson et al. Citation2020; Sorokowski et al. Citation2015). Whereas recent studies have started to address how narcissism drives behaviors of content creators (e.g., posting on social media) (Fox et al. Citation2018), relatively fewer studies have empirically addressed narcissism’s impact on response to advertising from consumers who implicitly assume a more passive role of mere recipients of information. The current research attempts to fill this knowledge gap. To this end, the current research identifies the relevance of ads to one’s self-image as a key moderator of how narcissism impacts consumers’ affective reaction. The counterintuitive results have particularly important implications for advertising practice, considering the intersection of renewed emphasis on ad relevance in the social media age (Hayes et al. Citation2020; Baker and Lutz Citation2000) and growing interest in achieving ad effectiveness via affective enhancement (Peck and Wiggins Citation2006; Oakes and North Citation2006; Chowdhury, Olsen, and Pracejus Citation2008).

Results from a series of experiments support the hypothesis that narcissism is associated with individuals’ negative affective reactions when they are exposed to ad materials that call for introspection of self-image. This finding calls for reevaluation of time-tested relevance-appeal approaches on the new frontier of social media advertising but also promises new opportunities for innovation of practice.

Implications to Practice

Social media advertising has seen rapid growth in the past decade and has demonstrated its advantages in consumer engagement and word of mouth (Errmann et al. Citation2019; Voorveld et al. Citation2018). The rise of narcissism is often cited as a by-product of the popularization of social media (Andreassen, Pallesen, and Griffiths Citation2017; Leung Citation2013). On this issue, the extant literature has primarily focused on how narcissism drives users’ online posting and sharing behaviors (Davenport et al. Citation2014; Fox et al. Citation2018). The use of brand ambassadors has been a popular tactic on social media. In contrast, the current research investigates how narcissism affects consumers on the receiving end of social media advertising, and the results call for caution when applying conventional knowledge about the relevance appeal. While users of social media might enjoy receiving praise for their selfies, how they react to advertising of close relevance to their self-images is a more nuanced question. Whereas narcissists use social media to project the grandiosity of themselves, they also seem to shun messages that have the potential to expose the vulnerability of their self-images, as seen in the results from Experiment 1. Therefore, in the case of promotional ads (as opposed to preventive or comparative ads), brands should consider refraining from using appeals that are too close to the ego, such as body images and other socially conspicuous props. On the other hand, Experiments 3(a) and 3(b) show that with appropriate designs personal relevance may be particularly critical to the success of preventive ads with narcissistic consumers. As narcissists naturally dislike exposure to threats to their self-images, they are bound to show stronger reactions to ads that depict disadvantages of undesirable consumptions or behaviors, given that the depicted cases are sufficiently relevant to their ideal self-images. For example, as addiction to electronic cigarettes has posed a challenge to the well-being of teenagers, public health promotors could continue the combat against the “coolness” of tobacco usage as a key tactic (Strombotne, Sindelar, and Buckell Citation2021; Measham, O’Brien, and Turnbull Citation2016).

Implications to Theory and Research

On the theoretical front, despite its increasing relevance to advertising practitioners, the topic of narcissism has attracted limited enthusiasm from marketing and advertising scholars. A possible explanation is that narcissism, as a construct mainly originating from the discipline of developmental and clinical psychology, has often been conceptualized as a chronic and relatively stable trait that individuals develop over a long period of time (Morf and Rhodewalt Citation2001; Wink Citation1991). This conceptualization implies challenges in both operationalization using the experimental methods in lab studies and the limited practical value of research findings in advertising contexts, because advertisers often look for drivers of behavior that can be temporarily manipulated at the time of ad exposure. However, while recognizing the difference across individuals, the emerging research has also shown that narcissistic tendencies in one person can also vary at different points in time and are subject to manipulation by external stimuli (Giacomin and Jordan Citation2016a, Citation2016b; de Bellis et al. Citation2016; Chen et al. Citation2021). Also, the recent methodological special issue of the Journal of Advertising confirmed that the experimental method is appropriate and effective at establishing causality (Chang Citation2017; Vargas, Duff, and Faber Citation2017; Geuens and De Pelsmacker Citation2017). Following these findings, coupled with the goal of the current research to delineate narcissism as the causal factor from an otherwise complex context of social media advertising, the empirical work has mainly construed narcissism as a situational factor and operationalized it using priming methods. It was confirmed that soliciting agentic thinking (as opposed to communal thinking) indeed elicited higher levels of narcissistic tendencies and led to a change in overall attitudes as the ad intended. The findings from the experiments were confirmed to be consistent with the results from the replication of Experiment 3(b) , which operationalized narcissism as a stable personality trait by directly measuring it using the NPI-13 without applying priming manipulation. Overall, the current research complements the growing body of research that conceptualizes narcissism as a situational factor and reaffirms the construct’s operational viability and practical relevance to the advertising literature.

It is important to highlight the similarities and differences between the priming methods used in the current research to produce between-subject differentials of narcissism and the methods conventionally used to prime self-construal (Cross, Hardin, and Gercek-Swing Citation2011). On one hand, self-construal is highly related to narcissism, and this empirical finding was the inspiration for the priming methods for narcissism (Giacomin and Jordan Citation2014). On the other hand, to ensure that the construct under investigation is indeed narcissism rather than general self-construal, previous research has emphasized the aspect of grandiosity, which is unique to narcissism, in its priming messages (de Bellis et al. Citation2016; Sakellaropoulo and Baldwin Citation2007). Following this tradition, in the current research the between-subject priming of narcissism embedded grandiose cues such as hostility (i.e., defying others’ doubts) and superiority (i.e., standout merits) in the priming material. However, despite these preemptive designs, it could still present the hazard of cross-loading between narcissism and self-construal. Therefore, until improved priming methods for state narcissism are developed, research on this topic should cross-validate its findings. In the case of the current research, Experiment 3(b) directly measured participants’ trait narcissism, independent of the confound with self-construal. Its findings confirmed those from the other experiments reported here. In future research, structural model analysis could also prove to be an effective approach to clarify the confound between narcissism and self-construal.

Limitations and Future Research

The current research uncovers that the interaction between narcissism and ads’ relevance to self-image leads to changes in the consumers’ affective responses. Because the primary goal is to explicate the causal relationship among the variables involved, the research exclusively uses online experiment methodology. As a result, the direct evidence is supportive of implications at the level of general impressions regarding the brand only, as seen in Experiment 1; and product use, as seen in Experiments 3(a) and 3(b). While one may expect the effects to extend further downstream, such as in changing actual purchase intentions or consumption patterns, future studies, particularly those using field studies or archival data, can be exceedingly advantageous at expanding the practical implications. Also, more field experiments may further validate the practical values of some procedures used in the experiments so far. For example, social media advertisers may benefit from confirmation regarding the extent to which the “me” versus “us” persona used in ads may lead to a differential in terms of the audience’s narcissistic tendency.

From a methodological perspective, the data for the current research were collected exclusively from online panels. Although due diligence was applied in the data collection process, online panels inherently harbor deficits, such as participant fatigue, hypothesis guessing, and potential biases that stem from regional or cultural characteristics (Ford Citation2017). Future research should examine the current findings through a wider lens that covers a more diverse population.

As a precaution against online panel participants’ fatigue during surveys (Ford Citation2017), experiments reported in the current research predominantly adopted single-item outcome measures. However, this approach could raise concerns regarding the reliability of each measure used. The reader may find reassurance that the results from multiple experiments, each using different scenarios and a variant outcome measure, converged on the same conclusion. However, future research should address this issue with more rigorous designs of the outcome measure.

Experiment 2 was designed with the focus of highlighting the psychological process that underlies the phenomenon reported in other experiments. To this end, sour flavor perception was adopted as a proxy for negative emotions, following the precedents set by prior research (Xu and Labroo Citation2014; Noel and Dando Citation2015). However, the projected flavor perception test conducted by online survey, instead of an actual taste test as in prior research, could have affected the reliability of this procedure. This defect can be remedied with future replication directly measuring negative emotions.

Information regarding the participants’ status of smoking habit was not collected for Experiments 3(a) and 3(b). Although random assignments to experimental conditions could have preempted the omitted-variable bias, future replication using fear appeal in ads in other contexts can enhance the reliability of the current findings.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yang He

Yang He (PhD, University of Georgia) is an assistant professor of marketing, Jack C. Massey College of Business, Belmont University.

References

- Andreassen, Cecilie Schou, Ståle Pallesen, and Mark D. Griffiths. 2017. “The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media, Narcissism, and Self-Esteem: Findings from a Large National Survey.” Addictive Behaviors 64:287–93. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

- Atlas, Gordon D., and Melissa A. Them. 2008. “Narcissism and Sensitivity to Criticism: A Preliminary Investigation.” Current Psychology 27 (1):62–76. doi:10.1007/s12144-008-9023-0

- Back, Mitja D., Albrecht C. P. Küfner, Michael Dufner, Tanja M. Gerlach, John F. Rauthmann, and Jaap J. A. Denissen. 2013. “Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry: Disentangling the Bright and Dark Sides of Narcissism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 105 (6):1013–37. doi:10.1037/a0034431

- Back, Mitja D., Stefan C. Schmukle, and Boris Egloff. 2010. “Why Are Narcissists so Charming at First Sight? Decoding the Narcissism-Popularity Link at Zero Acquaintance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (1):132–45. doi:10.1037/a0016338

- Baker, William E., and Richard J. Lutz. 2000. “An Empirical Test of an Updated Relevance-Accessibility Model of Advertising Effectiveness.” Journal of Advertising 29 (1):1–14. doi:10.1080/00913367.2000.10673599

- Barry, Christopher T., and Katrina H. McDougall. 2018. “Social Media: Platform or Catalyst for Narcissism?” In Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies, edited by Anthony D. Hermann, Amy B. Brunell, and Joshua D. Foster, 435–41. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_47.

- Batra, Rajeev, and Michael L. Ray. 1986. “Affective Responses Mediating Acceptance of Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Research 13 (2):234. doi:10.1086/209063

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2001. “Narcissism as Addiction to Esteem.” Psychological Inquiry 12 (4):206–10.

- Besser, Avi, and Beatriz Priel. 2009. “Emotional Responses to a Romantic Partner's Imaginary Rejection: The Roles of Attachment Anxiety, Covert Narcissism, and Self-Evaluation.” Journal of Personality 77 (1):287–325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00546.x

- Besser, Avi, and Beatriz Priel. 2010. “Grandiose Narcissism versus Vulnerable Narcissism in Threatening Situations: Emotional Reactions to Achievement Failure and Interpersonal Rejection.” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 29 (8):874–902. 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.8.874.

- Bülbül, Cenk, and Geeta Menon. 2010. “The Power of Emotional Appeals in Advertising the Influence of Concrete versus Abstract Affect on Time-Dependent Decisions.” Journal of Advertising Research 50 (2):169–80. doi:10.2501/S0021849910091336

- Bushman, Brad J., Angelica M. Bonacci, Mirjam Van Dijk, and Roy F. Baumeister. 2003. “Narcissism, Sexual Refusal, and Aggression: Testing a Narcissistic Reactance Model of Sexual Coercion.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84 (5):1027–40. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1027

- Campbell, W. Keith, and Joshua D. Foster. 2007. “The Narcissistic Self: Background, an Extended Agency Model, and Ongoing Controversies.” In Frontiers in Social Psychology: The Self, edited by Constantine Sedikides and Steven J. Spencer, 115–38. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. 10.4324/9780203818572.

- Campbell, W. Keith, Glenn D. Reeder, Constantine Sedikides, and Andrew T. Elliot. 2000. “Narcissism and Comparative Self-Enhancement Strategies.” Journal of Research in Personality 34 (3):329–47. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2282

- Campbell, W. Keith, Eric A. Rudich, and Constantine Sedikides. 2002. “Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and the Positivity of Self-Views: Two Portraits of Self-Love.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28 (3):358–68. doi:10.1177/0146167202286007

- Chang, Chingching. 2017. “Methodological Issues in Advertising Research: Current Status, Shifts, and Trends.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1):2–20. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1274924

- Chen, Siyin, Rebecca Friesdorf, Christian H. Jordan, and Siyin Chen. 2021. “Self and Identity State and Trait Narcissism Predict Everyday Helping State and Trait Narcissism Predict Everyday Helping.” Self and Identity 20 (2):182–98. doi:10.1080/15298868.2019.1598892

- Chowdhury, Rafi M. M. I., G. Douglas Olsen, and John W. Pracejus. 2008. “Affective Responses to Images in Print Advertising. Affect Integration in a Simultaneous Presentation Context.” Journal of Advertising 37 (3):7–18. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367370301

- Cross, Susan E., Erin E. Hardin, and Berna Gercek-Swing. 2011. “The What, How, Why, and Where of Self-Construal.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (2):142–79. doi:10.1177/1088868310373752

- de Bellis, Emanuel, David E. Sprott, Andreas Herrmann, Hans-Werner Bierhoff, and Elke Rohmann. 2016. “The Influence of Trait and State Narcissism on the Uniqueness of Mass-Customized Products.” Journal of Retailing 92 (2):162–72. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.11.003

- Davenport, Shaun W., Shawn M. Bergman, Jacqueline Z. Bergman, and Matthew E. Fearrington. 2014. “Twitter versus Facebook: Exploring the Role of Narcissism in the Motives and Usage of Different Social Media Platforms.” Computers in Human Behavior 32:212–20. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.011

- Errmann, Amy, Yuri Seo, Yung Kyun Choi, and Sukki Yoon. 2019. “Divergent Effects of Friend Recommendations on Disclosed Social Media Advertising in the United States and Korea.” Journal of Advertising 48 (5):495–511. doi:10.1080/00913367.2019.1663320

- Farwell, Lisa, and Ruth Wohlwend-Lloyd, and 1998. “Narcissistic Processes: Optimistic Expectations, Favorable Self-Evaluations, and Self-Enhancing Attributions.” Journal of Personality 66 (1):65–83. 10.1111/1467-6494.t01-2-00003.

- Ford, John B. 2017. “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A Comment.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1):156–8. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1277380

- Foster, Joshua D., and James C. Brennan. 2011. “Narcissism, the Agency Model, and Approach-Avoidance Motivation.” In The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments, edited by W. Keith Campbell and Joshua D. Miller, 89–100. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9781118093108.ch8

- Fox, Alexa K., Todd J. Bacile, Chinintorn Nakhata, and Aleshia Weible. 2018. “Selfie-Marketing: Exploring Narcissism and Self-Concept in Visual User-Generated Content on Social Media.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 35 (1):11–21. doi:10.1108/JCM-03-2016-1752

- Gentile, Brittany, Joshua D. Miller, Brian J. Hoffman, Dennis E. Reidy, Amos Zeichner, and W. Keith Campbell. 2013. “A Test of Two Brief Measures of Grandiose Narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality inventory-13 and the narcissistic personality inventory-16.” Psychological Assessment 25 (4):1120–36. . doi:10.1037/a0033192

- Geuens, Maggie, and Patrick De Pelsmacker. 2017. “Planning and Conducting Experimental Advertising Research and Questionnaire Design.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1):83–100. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1225233

- Giacomin, Miranda, and Christian H. Jordan. 2014. “Down-Regulating Narcissistic Tendencies: Communal Focus Reduces State Narcissism.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (4):488–500. doi:10.1177/0146167213516635

- Giacomin, Miranda, and Christian H. Jordan. 2016a. “Self-Focused and Feeling Fine: Assessing State Narcissism and Its Relation to Well-Being.” Journal of Research in Personality 63:12–21. . doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.009

- Giacomin, Miranda, and Christian H. Jordan. 2016b. “The Wax and Wane of Narcissism: Grandiose Narcissism as a Process or State.” Journal of Personality 84 (2):154–64. 10.1111/jopy.12148.

- Gu, Yuanbo, Ning He, and Guoqin Zhao. 2013. “Attentional Bias for Performance-Related Words in Individuals with Narcissism.” Personality and Individual Differences 55 (6):671–5. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.009

- Hayes, Jameson L., Guy Golan, Brian Britt, and Janelle Applequist. 2020. “How Advertising Relevance and Consumer–Brand Relationship Strength Limit Disclosure Effects of Native Ads on Twitter.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (1):131–65. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1596446

- Hartmann, Patrick, Vanessa Apaolaza, and Martin Eisend. 2016. “Nature Imagery in Non-Green Advertising: The Effects of Emotion, Autobiographical Memory, and Consumer’s Green Traits.” Journal of Advertising 45 (4):427–40. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1190259

- Hoover, J. Duane. 2011. “Complexity Avoidance, Narcissism and Experiential Learning.” Developments in Business Simulation and Experimental Learning 38 (2008):255–60.

- Homer, Pamela M., and Sun-gil Yoon. 1992. “Message Framing and the Interrelationships among Ad-Based Feelings, Affect, and Cognition.” Journal of Advertising 21 (1):19–33. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673357

- Horvath, Stephan, and Carolyn C. Morf. 2009. “Narcissistic Defensiveness: Hypervigilance and Avoidance of Worthlessness.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45 (6):1252–8. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.07.011

- John, Oliver P., Robins, Richard W. Kenneth H. Craik, Robyn M. Dawes, David C. Funder, Mike Kemis Adam Kremen, and Joachim Krueger. 1994. “Accuracy and Bias in Self-Perception: Individual Differences in Self-Enhancement and the Role of Narcissism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 66 (1):206–19. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.206

- Jung, Jaehee, and Seung Hee Lee. 2006. “Cross-Cultural Comparisons of Appearance Self-Schema, Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Dieting Behavior between Korean and U.S. Women.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 34 (4):350–65. doi:10.1177/1077727X06286419

- Krishna, Aradhna. 2016. “A Clearer Spotlight on Spotlight: Understanding, Conducting and Reporting.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 26 (3):315–24. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2016.04.001

- Krusemark, Elizabeth A., Christopher Lee, and Joseph P. Newman. 2015. “Narcissism Dimensions Differentially Moderate Selective Attention to Evaluative Stimuli in Incarcerated Offenders.” Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 6 (1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.003. doi:10.1037/per0000087

- Lang, Peter J., Margaret M. Bradley, and Bruce N. Cuthbert. 2008. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

- Leung, Louis. 2013. “Generational Differences in Content Generation in Social Media: The Roles of the Gratifications Sought and of Narcissism.” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (3):997–1006. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.028

- Lowery, Sarah E., Sharon E. Robinson Kurpius, Christie Befort, Elva Hull Blanks, Sonja Sollenberger, Megan Foley Nicpon, and Laura Huser. 2005. “Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Health-Related Behaviors among Male and Female First Year College Students.” Journal of College Student Development 46 (6):612–23. doi:10.1353/csd.2005.0062

- Maciantowicz, Oliwia, and Marcin Zajenkowski. 2021. “Emotional Experiences in Vulnerable and Grandiose Narcissism: Anger and Mood in Neutral and Anger Evoking Situations.” Self and Identity 20 (5):688–713. doi:10.1080/15298868.2020.1751694

- Measham, Fiona, Kate O’Brien, and Gavin Turnbull. 2016. “‘Skittles & Red Bull Is My Favourite Flavour’: E-Cigarettes, Smoking, Vaping and the Changing Landscape of Nicotine Consumption Amongst British Teenagers – Implications for the Normalisation Debate.” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 23 (3):224–37. 10.1080/09687637.2016.1178708.

- Mehta, Abhilasha. 2000. “Advertising Attitudes and Ads Effectiveness.” Journal of Advertising Research 40 (3):67–72. doi:10.2501/JAR-40-3-67-72

- Messmer, Donald J. 1979. “Repetition and Attitudinal Discrepancy Effects on the Affective Response to Television Advertising.” Journal of Business Research 7 (1):75–93. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(79)90027-4

- McCain, Jessica L., and W. Keith Campbell. 2018. “Narcissism and Social Media Use: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 7 (3):308–27. doi:10.1037/ppm0000137

- Mills, Jennifer S., Sarah Musto, Lindsay Williams, and Marika Tiggemann. 2018. “"Selfie" Harm: Effects on Mood and Body Image in Young Women.” Body Image 27:86–92. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.007

- Morf, Carolyn C., and Frederick Rhodewalt. 2001. “Unraveling the Paradoxes of Narcissism: A Dynamic Self-Regulatory Processing Model.” Psychological Inquiry 12 (4):177–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1

- Morris, Jon D., Yunmi Choi, and Ilyoung Ju. 2016. “Are Social Marketing and Advertising Communications (SMACs) Meaningful?: A Survey of Facebook User Emotional Responses, Source Credibility, Personal Relevance, and Perceived Intrusiveness.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 37 (2):165–82. doi:10.1080/10641734.2016.1171182

- Nash, Kyle, Andre Johansson, and Kumar Yogeeswaran. 2019. “Social Media Approval Reduces Emotional Arousal for People High in Narcissism: Electrophysiological Evidence.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 13 (September):292. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00292

- Noel, Corinna, and Robin Dando. 2015. “The Effect of Emotional State on Taste Perception.” Appetite 95:89–95. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.003

- Oakes, Steve, and Adrian C. North. 2006. “The Impact of Background Musical Tempo and Timbre Congruity upon Ad Content Recall and Affective Response.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (4):505–20. doi:10.1002/acp.1199

- Patel, Pankaj C., and Danielle Cooper. 2014. “The Harder They Fall, the Faster They Rise: Approach and Avoidance Focus in Narcissistic Ceos.” Strategic Management Journal 35 (10):1528–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj. doi:10.1002/smj.2162

- Peck, Joann, and Jennifer Wiggins. 2006. “It Just Feels Good: Customers’ Affective Response to Touch and Its Influence on Persuasion.” Journal of Marketing 70 (4):56–69. doi:10.1509/jmkg.70.4.56

- Petty, Richard E., and John T. Cacioppo. 1981. “Issue Involvement as a Moderator of the Effects on Attitude of Advertising Content and Context.” Advances in Consumer Research 8 (January):20–24. http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/9252/volumes/v08/NA-08.

- Poels, Karolien, and Siegfried Dewitte. 2006. “How to Capture the Heart? Reviewing 20 Years of Emotion Measurement in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising Research 46 (1):18–37. doi:10.2501/S0021849906060041

- Quenqua, Douglas. 2013. “Seeing Narcissists Everywhere.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/06/science/seeing-narcissists-everywhere.html.

- Raskin, Robert, and Howard Terry. 1988. “A Principal-Components Analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and Further Evidence of Its Construct Validity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (5):890–902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

- Rhodewalt, Frederick, Jennifer Madrian, and Sharon Cheney. 1998. “Narcissism, Self-Knowledge Organization, and Emotional Reactivity: The Effect of Daily Experiences on Self-Esteem and Affect.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 24 (1):75–87. doi:10.1177/0146167298241006

- Rhodewalt, Frederick, and Carolyn C. Morf. 1998. “On Self-Aggrandizement and Anger: A Temporal Analysis of Narcissism and Affective Reactions to Success and Failure.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (3):672–85. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.672

- Sakellaropoulo, Maya, and Mark W. Baldwin. 2007. “The Hidden Sides of Self-Esteem : Two Dimensions of Implicit Self-Esteem and Their Relation to Narcissistic Reactions.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (6):995–1001. . doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.009

- Shane-Simpson, Christina, Anna M. Schwartz, Rudy Abi-Habib, Pia Tohme, and Rita Obeid. 2020. “I Love My Selfie! An Investigation of Overt and Covert Narcissism to Understand Selfie-Posting Behaviors within Three Geographic Communities.” Computers in Human Behavior 104 (May 2019):106158. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.106158

- Sorokowski, P., A. Sorokowska, A. Oleszkiewicz, T. Frackowiak, A. Huk, and K. Pisanski. 2015. “Selfie Posting Behaviors Are Associated with Narcissism among Men.” Personality and Individual Differences 85:123–7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.004

- Spiller, Stephen A., Gavan J. Fitzsimons, John G. Lynch, Jr., and Gary H. Mcclelland. 2013. “Spotlights, Floodlights, and the Magic Number Zero : Simple Effeots Tests in Moderated Regression.” Journal of Marketing Research 50 (2):277–88. doi:10.1509/jmr.12.0420

- Stout, Patricia A., and John D. Leckenby. 1986. “Measuring Emotional Response to Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 15 (4):35–42. doi:10.1080/00913367.1986.10673036

- Strombotne, Kiersten, Jody Sindelar, and John Buckell. 2021. “Who, Me? Optimism Bias about US Teenagers’ Ability to Quit Vaping.” Addiction 116 (11):3180–8. doi:10.1111/add.15525

- Stucke, Tanja S., and Siegfried L. Sporer. 2002. “When a Grandiose Self-Image Is Threatened: Narcissism and Self-Concept Clarity as Predictors of Negative Emotions and Aggression following Ego-Threat.” Journal of Personality 70 (4):509–32. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.05015

- Twenge, Jean M., and W. Keith Campbell. 2009. The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. New York, NY: Free Press

- Vargas, Patrick T., Brittany R. L. Duff, and Ronald J. Faber. 2017. “A Practical Guide to Experimental Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1):101–14. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1281779

- Veldhuis, Jolanda, Jessica M. Alleva, Anna J. D. Bij de Vaate, Micha Keijer, and Elly A. Konijn. 2020. “Me, My Selfie, and I: The Relations between Selfie Behaviors, Body Image, Self-Objectification, and Self- Esteem in Young Women.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 9 (1):3–13. doi:10.1037/ppm0000206

- Voorveld, Hilde A. M., Guda van Noort, Daniël G. Muntinga, and Fred Bronner. 2018. “Engagement with Social Media and Social Media Advertising: The Differentiating Role of Platform Type.” Journal of Advertising 47 (1):38–54. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754

- Wink, Paul. 1991. “Two Faces of Narcissism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (4):590–7. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590

- Xu, Alison Jing, and Aparna a Labroo. 2014. “Incandescent Affect: Turning on the Hot Emotional System with Bright Light.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24 (2):207–16. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2013.12.007