Abstract

Artificially created characters – virtual influencers – amass millions of followers on social media and affect digital natives’ engagement and decisionmaking in remarkable ways. Guided by the Uses and Gratification (U&G) approach and the Uncanny Valley Theory, this study seeks to understand this phenomenon. By looking into followers’ engagement with virtual influencers, this study identifies and conceptualizes six primary motivations – namely, novelty, information, entertainment, surveillance, esthetics, and integration and social interaction. Furthermore, we found that most followers perceive virtual influencers as uncanny and authentically fake. However, followers also express acceptance of their staged fabrication where curated flaws and self-justification have been found to mitigate the effect of the uncanny valley. Virtual influencers are considered effective in building brand image and boosting brand awareness, but lack the persuasive ability to incite purchase intention due to a lack of authenticity, a low similarity to followers, and their weak parasocial relations with followers. These findings advance the extant literature on U&G, influencer advertising, and virtual influencers in the era of artificial intelligence; provide insights into the mitigating factors of the uncanny valley; and yield theoretical and practical implications for the efficacy of virtual influencers in advertising campaigns.

Social media’s rise has sparked a trend of influencer marketing, a marketing strategy where brands collaborate with social media influencers (SMIs) to drive brand awareness and product acquisition (Lou and Yuan Citation2019). Social media influencers are individuals who build expertise on a specific topic to affect the purchasing decisions of others (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017; Lou and Yuan Citation2019). In recent years, virtual influencers (VIs) have entered the market, creating competition for human influencers (Mediakix Citation2019). Virtual influencers are fictional, computer-generated individuals who have human traits, characteristics, and personalities (Thomas and Fowler Citation2021). They are the latest soaring genre, as global spending on artificial intelligence (AI) technology is expected to grow from $50 billion in 2020 to over $110 billion in 2024 (Jeans Citation2020). These artificially created characters amass followings of up to a few million on social media platforms. A prominent example is Lil Miquela, a virtual influencer with more than 3 million followers on Instagram, who TIME Magazine named as one of the Top 25 most influential people on the internet (TIME Citation2018).

The popularity of virtual influencers makes it critical for us to explore the reasons for following them, through the lens of uses and gratifications theory (U&G). U&G theory states that audiences use media platforms for their own benefits (Katz Citation1959). Existing studies have largely explicated users’ motivations for following social media accounts and for using social media in general (Alhabash and Ma Citation2017); however, the gratifications gained from following VIs has not been sufficiently addressed. Hence, our study aims to fill this gap in the literature by examining users’ motivations for following VIs. Moreover, existing studies have noted the importance of human-like characteristics in VIs (Molin and Nordgren Citation2019). However, Mori’s uncanny valley theory (1970) predicts negative responses from consumers when the appearance of artificial faces becomes too realistic, resulting in feelings of uncanniness and creepiness. With this, consumers’ perceptions of VIs can hit a point at which animosity and mistrust outweigh curiosity and fascination. Although existing literature has attempted to study the relationship between the uncanny valley and robots (e.g., Ho and MacDorman Citation2010; Mathur and Reichling Citation2016), how consumers react to the uncanny appearance of VIs specifically and what factors can mitigate the negative impact of this uncanniness have not been thoroughly explored.

Despite concerns about the uncanny valley, prominent VIs have already collaborated with global brands such as Balmain, Dior, IKEA, and Calvin Klein (Morency Citation2018). A recent report shows that followers engage more with VI-generated content than that of human influencers within the same follower number range (Baklanov Citation2019). While previous research has found that influencer marketing has a positive effect on advertising effectiveness (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017; Lee and Koo Citation2015; Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Scholz Citation2021), other studies also have shown that VIs’ lack of authenticity and transparency could attenuate consumers’ positive reactions to and credibility and trust in VIs’ sponsored posts (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Molin and Nordgren Citation2019; Moustakas et al. Citation2020). Therefore, because of the artificial nature of virtual influencers, it is essential to understand the extent of their marketing effectiveness; however, so far efforts to do this have been limited in the current literature (e.g., Sands et al. Citation2022).

To fill these research gaps, our study uses the U&G theory (Katz Citation1959) to discover the motivations for following VIs and explores the potential effects of the uncanny valley theory (Mori Citation1970) on consumers via a series of in-depth interviews with followers of VIs in Singapore. This study identified and theorized six follower motivations, including novelty, information, entertainment, surveillance, esthetics, and integration and social interaction. We found that most followers did indeed perceive VIs as uncanny and eerie. However, these same followers also considered VIs’ crafted fabrication and narratives authentically fake where curated flaws and self-justification were found to mitigate the effects of the uncanny valley. Furthermore, VIs are considered effective in building brand image and increasing brand awareness, but have limited influence on purchase intention due to a lack of authenticity, a low similarity to followers, and their weak parasocial relations with followers.

Theoretically, these rich findings advance the extant literature on influencer advertising and the U&G theory, and offer a comprehensive and systematic theorization of followers’ motivations for following VIs in the new era of influencer advertising. Secondly, the current findings advance the literature on the uncanny valley theory and provide insights into the mitigating factors of the uncanny valley’s effect in relation to VIs. Finally, the current findings delineate VI’s efficacy and its underlying mechanisms in advertising effectiveness. These findings offer concrete and strategic recommendations for brands in their campaigns that employ VIs.

Literature Review

Influencer Marketing, Social Media Influencers, and Virtual Influencers

Social media and online media have given everyday individuals the ability to accumulate marketable popularity and influence. This group of influential individuals, or viral content generators, who hold a huge potential for brands and advertisers, are often referred to as social media influencers (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017; Lou and Yuan Citation2019). They carry sociocultural currency, or celebrity capital, in the advertising domain through brand endorsements (Brooks, Drenten, and Piskorski Citation2021), and can be categorized as “authentic source of information – due to their perceived credibility, accessibility, similarity, and relatability – that consumers can draw on to support their identity construction endeavors” (Scholz Citation2021, 512). Influencer marketing or influencer advertising, refers to brands’ investments in hiring SMIs as brand endorsers to promote sponsored products, brands, or both (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Lou and Yuan Citation2019). It has experienced exponential growth over the past few years and continues to rise.

Nascent, but growing, literature on influencer marketing has examined factors that influence the efficacy of influencer campaigns such as the number of followers and product divergence (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017), influencer credibility and content value (Lou and Yuan Citation2019), the parasocial relations between influencers and followers (Boerman and Van Reijmersdal Citation2020; Hwang and Zhang Citation2018), sponsorship disclosure (Evans et al. Citation2017), product-endorser fit (Schouten, Janssen, and Verspaget Citation2020), and influencer types (e.g., micro- vs. mega influencers) (Park et al. Citation2021). Recent literature has ventured into exploring more nuanced issues, including virtual influencers (Thomas and Fowler Citation2021). For instance, Thomas and Fowler (Citation2021) argued that AI influencers can be equally as effective as human celebrity endorsers in driving favorable brand attitudes or purchase intention. They also stated that, when AI influencers commit transgressions, replacing an AI influencer with a celebrity endorser (vs. another AI influencer or no replacement) might be more efficient in achieving desirable advertising outcomes.

Virtual or AI influencers have gained increased traction in recent years, and most of them are “similar to human beings in terms of their physical appearance, personality, and behaviour” (Moustakas et al. Citation2020, 1). Although they are computer-fabricated identities, virtual influencers – like human influencers – are content generators and personalities on social media, where they exhibit human characteristics in their posts and interactions with followers and where they have also amassed a sizable following (Miyake Citation2022; Mrad, Ramadan, and Nasr Citation2022; Robinson Citation2020). When judged by their level of human likeness, virtual influencers can be broadly split into two categories: anime-like VIs (e.g., Noonoouri) and human-like VIs (e.g., Lil Miquela) (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021). Anime-like VIs refer to those that are not humanoid; rather, they are “anthropomorphized to fit into a human social network,” whereas human-like VIs are more like humans in terms of their appearance and interactions (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021, 4). On one hand, findings show that human-like VIs tend to engender feelings of eeriness among their followers, due to their high resemblance to humans (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021). This is also referred to as the uncanny valley effect (Mende et al. Citation2019). On the other hand, it has been argued that VIs are effective marketing tools because of their attractiveness, human-like functionality, and audiovisual features (Faddoul and Chatterjee Citation2020). Interestingly, VIs have been found to elicit higher word-of-mouth intentions, but lower trust when compared to SMIs (Sands et al. Citation2022). Although VIs and human influencers share commonality in terms of celebrity status and marketing value, VIs are essentially computer-generated personae who mimic varying degrees of humanness and behavior. In this research, we explore the underlying reasons that motivate followers’ engagement with VIs and their reactions to VIs. In the following sections, we draw on the uses and gratifications theory (U&G) and the uncanny valley theory to explicate followers’ motivations of following VIs and their perceptions and evaluations of VIs being a marketing tool.

Uses and Gratifications and Engagement with Virtual Influencers

Uses and gratifications, a classic mass communication theory, adopts a user-centric approach to explain why and how media users actively use different media to satisfy their social and psychological needs (Katz Citation1959; Ruggiero Citation2000). Katz (Citation1959) argued that people on media platforms consume media for their own benefits. Current U&G research often focuses on “(1) the social and psychological origins of (2) needs, which generate (3) expectations of (4) the mass media or other sources, which lead to (5) differential patterns of media exposure (or engagement in other activities), resulting in (6) need gratifications and (7) other consequences, perhaps mostly unintended ones” (Katz, Blumler, and Gurevitch Citation1973, 510). Although it was conceptualized the era of traditional media, U&G has been used to study not only traditional media use (i.e., TV, newspapers, radio) (e.g., Abelman Citation1987), but also new media or technology use (e.g., online media, social media, mobile phones) (e.g., Alhabash and Ma Citation2017). For example, Alhabash and Ma (Citation2017) conducted a cross-sectional survey that examined the motivations for using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, and found convenience, medium appeal, passing time, and entertainment were the top four motivations across all platforms.

More importantly, U&G has been applied to explicate consumer motivations of why they engage with interactive advertising and brand communications (Sook Kwon et al. Citation2014). In relation to influencer marketing, recent literature has also adopted the U&G approach to contextualize why consumers are drawn to influencers in the first place (e.g., Croes and Bartels Citation2021; Lee et al. Citation2022; Morton Citation2020). Lee et al. (Citation2022) uncovered four primary motivations for following influencers on Instagram: authenticity, consumerism, creative inspiration, and envy. They claimed that individual differences, such as materialism, correlated significantly with these motivations, some of which subsequently predicted followers’ trust in influencer-sponsored posts and purchase behavior. Similarly, Croes and Bartels (Citation2021) revealed six motivations that young adults exhibit when following influencers: information sharing, [following] cool and new trends, relaxing entertainment, companionship, boredom/habitual pass time, and information seeking.

Although VIs resemble human influencers in terms of popularity, status, personality, and interactional behavior with their followers (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021), VIs are essentially AI-generated artifacts, based on natural language processing and machine learning (Thomas and Fowler Citation2021). Compared to human influencers, VIs have the advantage of maximizing the use of AI technology to maintain consistency in their interactions and sponsored posts (Del Rowe Citation2019). They may even be treated as social beings by their followers if they are anthropomorphized or human-like (Yam et al. Citation2021). Yet research on human-robot interactions also argues that humans treat AI/robots and humans differently (Mou, Xu, and Xia Citation2019 because humans tend to have a generalized aversion or hostility toward AI/robots due to bias against nonhumans or speciesism (Wirtz et al. Citation2018). We expect that these differences, between VIs and human influencers, will play a role in determining followers’ motivations to follow VIs. Hence, we proposed the following research question:

Research Question 1: What are the primary motivations for following virtual influencers?

The Uncanny Valley Theory and Virtual Influencers

As more brands engage VIs, consumers are raising concerns about the uncanniness of virtual influencers. The uncanny valley theory from Mori (1970) helps us to understand the reasons behind consumers’ acceptance of or aversion to VIs. The original theory by Mori was devised in 1970, where he hypothesized “a nonlinear relation between a character’s degree of human likeness and the emotional response of the human receiver” (Ho and MacDorman Citation2010, 1). He also theorized that realistic, humanoid faces are seen as more appealing and trustworthy than unrealistic, humanoid faces, but stated that consumers view a nonhuman artifact as unnatural and uncomfortable, after it reaches a high level of human realism. This point is also highlighted in recent literature, which shows that consumers have a higher acceptance of VIs that appear more human-like, but feel that the VIs are “unpleasant and unrealistic” if the resemblance to humans is too accurate (Molin and Nordgren Citation2019, 23).

Extant literature on the uncanny valley and its relation to digitally created characters or robots has mainly explored the linear or nonlinear relationship between the human likeness of artifacts and people’s negative affect (Burleigh, Schoenherr, and Lacroix Citation2013; Schwind, Wolf, and Henze Citation2018), as well as the factors that affect the perceived uncanniness of artifacts (e.g., the lack of startled response to a screaming sound, negative personality traits, or live interaction with robots) (Tinwell, Nabi, and Charlton Citation2013). In a recent review article, Kätsyri et al. (Citation2015) argued that not all types of human-likeness manipulations would lead to the uncanny valley, and that the uncanny valley phenomenon manifests itself only when a perceptual mismatch (e.g., inconsistent realism or atypical features in the stimuli) occurs, but not for categorization ambiguity (e.g., blurred boundary between nonhuman and human).

Recent studies have also explored followers’ reactions to VIs through the lens of uncanny valley theory (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Block and Lovegrove Citation2021; Molin and Nordgren Citation2019). Echoing the predictions of this theory, Arsenyan and Mirowska (Citation2021) evidenced followers’ greater negative reactions to human-like VIs, compared to anime-like or human influencers. However, Block and Lovegrove (Citation2021) had different findings, and argued that the transparent uncanniness and humanness of VIs altogether, and simultaneously, substantiated and drove the VI’s persuasiveness (e.g., Lil Miquela) among followers, making their uncanniness – to a certain extent – appealing. In other words, VIs create “fear and fascination and familiar/unfamiliar experiences through ‘uncanny valley’ storyworlds that are human but not too much” (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021, 271), and this experience cannot be fully offered by human influencers. Collectively, these inconsistent findings highlight the unique role that a VI’s uncanniness plays in followers’ reactions and engagement, which prompts this research to offer a more nuanced explication of the VI’s uncanniness.

Moreover, while the uncanny valley theory mostly predicts negative reactions toward artificial faces or human-like robots, some studies have explored ways to alleviate the negative effects. One study found that consumers’ acceptance of robots increased when the robots displayed some form of social interaction or “social presence,” referring to whether consumers believed that they were actually communicating with another social being (Wirtz et al. Citation2018). However, the reasons for consumers’ acceptance of the uncanniness that is specific to VIs have not been thoroughly explored, and VIs still boast a significant number of engaged followers, despite the presence of the uncanny valley effect (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021). Furthermore, although prior studies have often focused on followers’ perceptions of VIs’ appearances (Jang and Yoh Citation2020; MacDorman and Chattopadhyay Citation2016), there is a lack of research into other factors, which might moderate their uncanniness; for example, factors that are indigenous to VIs’ behavior, characteristics, or personality. Taken together, this study sought to fill in the aforementioned gaps by proposing a second and third research question:

Research Question 2: Whether and how do followers react to the uncanniness of VIs?

Research Question 3: Which factors could alleviate followers’ perceived uncanniness of VIs?

Virtual Influencers and Marketing Effectiveness

Current literature on virtual influencer marketing has raised concerns regarding their marketing effectiveness. Molin and Nordgren (Citation2019) noted that VIs’ lack of authenticity and transparency caused followers to distrust their sponsored messages. However, others suggest that virtual influencer marketing can be successful if the influencer’s narrative and character building are creative and well executed (Moustakas et al. Citation2020). VIs, such as Lil Miquela, work well as promotional commodities because they lack the deviancy and spontaneity that human influencers have – enabling them to be an easily manipulated and controlled tool (Drenten and Brooks Citation2020). Zhou (Citation2020) also argues that the flexibility and freedom of their virtual nature better enable the creation of intimate parasocial interactions with their followers, whereby a strong parasocial relationship can increase perceived trustworthiness (Jin, Ryu, and Muqaddam Citation2021), which translates into higher purchase intention and marketing effectiveness (Sokolova and Kefi Citation2020).

Collectively, marketing effectiveness in influencer marketing has often been measured using the three outcomes: brand awareness, brand image, and purchase intention (Lou and Yuan Citation2019; CitationTabellion and Esch 2019). We focused on brand awareness and purchase intention as key marketing indicators because these two align with brands’ leading goals in influencer marketing: boosting brand mentions, and brand awareness and sales (Esseveld Citation2017). This selection is echoed by recent research that also focused on brand awareness and purchase intention when examining the efficacy of influencer marketing (Lou and Yuan Citation2019). Specific to virtual influencer marketing, one of the major benefits of VIs – as a novel technology – is to help brands modernize or change brand image while remaining completely controllable, when compared to human influencers (Vale Citation2021). Therefore, we also include brand image as a key marketing outcome and elaborate on the potential impact of VIs on each outcome below.

Brand Awareness

Sasmita and Suki (Citation2015, 78) defined brand awareness as “how consumers associate the brand with the particular product they aim to own.” It has an essential role in the consumer’s purchase decisionmaking process (Barreda et al. Citation2015). Recent findings argue that brands can increase brand awareness in a more cost-effective way by engaging macroinfluencers as opposed to high-profile celebrities (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). Influencers’ visibility and recognizability also play an important role in increasing brand awareness (Bakker Citation2018). Thus, we intended to study how VIs affect brand awareness. Influencer marketing studies have documented a positive impact on brand awareness, especially if the influencer’s presentation and expertise align with the sponsor brand’s offerings. Lou and Yuan (Citation2019) found that the level of trust that followers and consumers have in their influencer is a significant factor in increasing brand awareness and purchase intention. Nevertheless, we were unsure whether these findings still applied to VIs, where doubts have been raised about their ability to create trusting and ethical relationships (e.g., Molin and Nordgren Citation2019; Robinson Citation2020).

Brand Image

Brand image is defined as a “set of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that a person holds regarding an object” (Kotler Citation2001, 273). It also refers to the unconscious brand associations that appear in consumers’ minds (Biel Citation1992). Studies have shown that employing SMIs in advertising campaigns positively shapes brand image (Hermanda, Sumarwan, and Tinaprillia Citation2019). Communicative influencers can also shape a brand or product image, which eventually contributes to increasing purchase intention (Nurhandayani, Syarief, and Najib Citation2019). However, the negative connotations or publicity that come with a hired influencer can also be transferred to the sponsored brand (Neff Citation2019). VIs differ from regular influencers, as their personalities can be tailored to match the values of the sponsored brand. Conversely, VIs’ fabricated nature has raised ethical concerns in the industry regarding the possibility of deepfakes, and of their advancement of stereotypes and promotion of unrealistic body images. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the effect of VIs on brand image to better determine their marketing effectiveness.

Purchase Intention

Purchase intention is defined as “an individual’s conscious plan to make an effort to purchase a brand” (Spears and Singh Citation2004, 56). The existing body of literature predicts that consumers’ attitudes toward influencers (Spears and Singh Citation2004), and their attitudes toward the brand (Pradhan, Duraipandian, and Sethi Citation2016), as well as electronic word of mouth (Erkan and Evans Citation2018) have a significant influence on purchase intention. Furthermore, Fisherman’s influence model argues that hiring influencers with the largest following and market reach is most beneficial in driving brand awareness and, ultimately, purchase intention (Brown and Fiorella Citation2013). Previous studies have found that influencer marketing has positive effects on purchase intention (Lee and Koo Citation2015), especially when the influencers are able to convey trustworthiness and domain knowledge in their sponsored posts (Lou and Yuan Citation2019). However, because of the artificial nature of virtual influencers, we aimed to discover whether this effect applies to them in the same way.

Overall, and to obtain a better understanding of the extent of VIs’ advertising effectiveness and the underlying factors, we asked:

Research Question 4: How do VIs drive marketing effectiveness (i.e., brand awareness, brand image, and purchase intention) and why?

Method

We used a qualitative, semistructured interview method to address the research questions. Echoing the qualitative in-depth interview approach adopted by recent researchers who examined exploratory, yet nuanced, theoretical questions in influencer marketing (e.g., Brooks, Drenten, and Piskorski Citation2021; Lou Citation2022), we also chose to use qualitative, in-depth interviews. Semistructured, in-depth interviews not only enabled us to deductively examine questions that were guided by predetermined theories (U&G and the uncanny valley theory; Research Questions 1 and 2), but also granted us the leeway to capture any uncharted new theoretical forefronts that could later be inductively analyzed (Research Questions 3 and 4). After securing ethical approval, we conducted online interviews with 26 Singaporeans who currently follow VIs on social media. We stopped the data collection after no new insights emerged from the interviews. The majority of the interviewees were women (N = 17), with most of them being Chinese (N = 21) (age range: 20 to 28 years old, M = 22.54, SD = 1.88). The interviewees were a mixture of students and professionals (see demographics in ).

Table 1. Demographics of interviewees.

Participants and Procedure

Interviewees were recruited through snowball sampling and were given 20 Singapore dollars as remuneration. Participants were considered eligible if they had been following at least one VI prior to their knowledge of this study. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes to an hour. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted via Zoom. Recent findings have shown that moving field research online, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, does not necessarily compromise the rigor of the findings (Dodds and Hess Citation2021). All the interviewees gave their signed consent prior to the interviews, where they were informed that the session would be audio recorded but that no identifying information would be published or used. Any two, out of four, trained research assistants conducted each session, with one being the interviewer and the other a scribe. They conducted all the interviews in English and followed a list of questions, asking follow-up questions when necessary (see supplemental online Appendix A). Each interviewee was asked about their social media use, motivations, and perceptions of their followed VIs and their marketing effectiveness.

Data Analysis

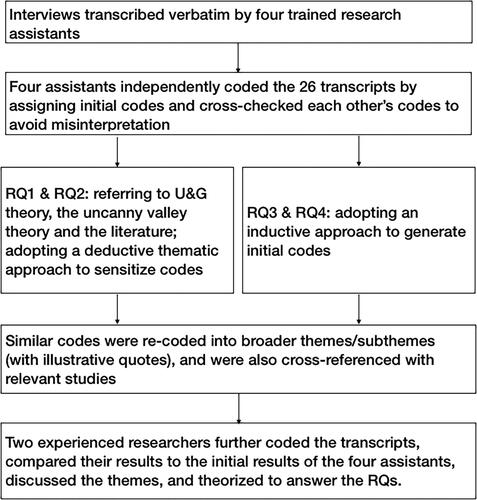

First, each interviewee’s transcript was transcribed verbatim and coded line by line. We adopted a combined approach of deductive thematic analysis and inductive analysis (Boyatzis Citation1998). Concerning the followers’ motivations and potential reactions to the uncanniness of VIs (Research Questions 1 and 2), we followed Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) deductive approach and drew on the predetermined framework – U&G and the uncanny valley theory – to sensitize initial codes, summarizing the data and comparing any emerging codes to existing findings relevant to the two theories. When it came to the exploratory inquiries, which asked about factors that could alleviate the followers’ perceived uncanniness of VIs and the variables affecting a VI’s marketing effectiveness (Research Questions 3 and 4), we adopted the data-driven, inductive analysis approach used by Boyatzis (Citation1998). In particular, we read and reread the data carefully to assign codes that captured and interpreted the richness of the observations. The four assistants coded a total of 314 pages of transcripts (single-spaced, size 12 font) independently and cross-checked each other’s codes to avoid any possible misinterpretation of the data.

Second, the four assistants carried out an axial-coding stage where they recoded similar concepts or codes into broader categorical themes (e.g., information motivation) (Charmaz Citation2006). The coded themes that arose from the collated results were also cross-referenced with relevant studies to check for similar conceptual categories. Finally, two experienced researchers, who had the relevant theoretical knowledge, further coded the transcripts and compared their results to the initial results of the four assistants. These two researchers compared their quotes to those generated by the four assistants, discussed them, and resolved inconsistencies in the selected quotes. They then theorized the findings (see coding flowchart in ). To ensure the confidentiality of the data, we assigned pseudonyms when quoting interviewees’ responses (see ).

Results

We found that almost all of the interviewees interacted with VIs in the same way as they interacted with SMIs – passively browsing the posts that appear in the newsfeed. The interviewees also indicated that they tended to like the posts generated by SMIs or VIs, but rarely commented on those posts. However, in terms of marketing effectiveness, almost all the interviewees indicated that they trusted VIs less than they did SMIs and had never purchased anything recommended by VIs because of their lack of similarity, weak parasocial relations, and lack of authenticity (Research Question 4). However, many of the interviewees reported that they trusted SMIs and had followed their product recommendations because of their expertise, trustworthiness, and the bond between them. In particular, all of the interviewees had followed at least one human-like VI (e.g., Lil Miquela, Bermuda, or Shudu), and a few had followed an anime-like VI (e.g., Kizuna AI). Thus, the findings below are predominantly focused on human-like VIs, especially where they relate to the uncanny valley effect.

Motivations for Following VIs

In answering Research Question 1, six primary motivations emerged from our analysis: novelty, information, entertainment, surveillance, esthetics, and integration and social interaction.

Novelty

Herein, novelty relates to followers’ curiosity in exploring VIs – a new technological application – and the limits of its functions (Brandtzaeg and Følstad Citation2017). Since a virtual influencer is a fairly new idea, most of the interviewees mentioned that they were intrigued by this new technology and its mechanism and reported that they followed VIs because of their novelty. Farhan, a 22-year-old man who has followed Lil Miquela said, “I think what most people are hooked in with is just the novelty of it.” Similarly, Xin Yi (a 20-year-old woman) who has followed Lil Miquela said, “I think if she is not an AI influencer, I don’t think I’d follow her.” Most of the interviewees explained that they found the concept of a VI to be novel and intriguing. As Joe (a 24-year-old woman) who has followed several VIs (i.e., Lil Miquela, K/DA, and seradotway) put it:

Lil Miquela is like one of the first few virtual influencers … you can create every single aspect that you want, so you know, backdrop, pose or whatever location.

Information

Information motivation refers to followers’ need to seek out new knowledge or information related to AI or VI technology, a certain topic, or related marketing strategies (e.g., Vale and Fernandes Citation2018). We found that interviewees followed VIs because they wanted to learn about the related technology/topic or marketing tactics. For instance, Eric (a 23-year-old man) followed Lil Miquela because he is “interested in the whole development of CGI influencers.” Jia Hao (a 25-year-old man) followed Imma.gram because she represents a part of Japanese culture that he likes. More specifically, Jasmine (a 23-year-old woman) said she is interested to “see how this way of advertising, or like way of marketing goes.”

Entertainment

Most interviewees also mentioned that they followed VIs to amuse themselves with appealing content or as a distraction (Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Morton Citation2020). Farhan (a 22-year-old man) who works in the media industry stated that he enjoys content from virtual YouTubers very much and realized that he wanted more of it after watching various content. This motivation results in a sustained following of these virtual influencers, as they are able to provide the enjoyment factor that their audience is looking for. Sarah (a 23-year-old woman) echoed this sentiment, describing Lil Miquela’s feed as “visually appealing” and fun to follow. Interviewees also described following a virtual influencer as being like enjoying a storyline and said they wanted to see surprises and fun elements. As Mark (a 21-year-old man) said: “I think it’s quite interesting to see how a robot can have so many followers. Like I would not have imagined that a robot would be more popular than a real human being.”

Surveillance

We also uncovered surveillance as one of the primary motivations for following VIs. This refers to the drive to be updated and to stay “in the know” about the VIs’ daily lives (Morton Citation2020). Victoria (2a 20-year-old woman) said that she followed Lil Miquela and Bermuda to “keep up with what she posts and likes.” Similarly, Ashley (a 23-year-old woman) wanted to see “where this [VI] is going, or if there is going to be a reveal about who’s behind it and stuff like that.” Sarah (a 23-year-old woman) also echoed this sentiment: “I just ‘Kaypo’ [being nosy]. I want to see what she [Lil Miquela] gets to like … I want to see how it can blur the lines between like a human and a humanoid.”

Esthetics

Esthetics also emerged as one of the major motivations, and included liking the visual or esthetic aspect of influencer-generated contents (Ki et al. Citation2020). Jia Yi (2a 20-year-old woman) mentioned that visual esthetics was a key factor for her following VIs on Instagram, as she used them as inspiration. Similarly, many of our interviewees chose to follow VIs for this esthetic motivation. Paul (a 28-year-old man) stated that Imma.gram’s post esthetics were the main reason why he followed and is still currently following her. Additionally, several interviewees chose to follow VIs as they appreciated the esthetics and style. Jasmine (a 23-year-old woman) who followed Lil Miquela said, “I only follow her because I feel like her aesthetics/her face, resonates with me most.”

Integration and Social Interaction

Finally, we identified integration and social interaction as another major motivation for following VIs. Herein, integration and social interaction describes “the need of bonding with people with a common passion, gaining a sense of belonging to a community and meeting like-minded others” (Vale and Fernandes Citation2018, 42). A handful of interviewees mentioned that they resonated with the values that the VIs advocated (e.g., racial justice, or gender equality) or the personalities that they presented. Farhan (a 22-year-old man) mentioned that Lil Miquela has been vocal about political and social issues, which also aligned with his perspective. Similarly, Hafiz (a 25-year-old man) explained that he will follow VIs when “they coincide with my values.” Other interviewees also expressed that they followed VIs because of the curated personalities, feeling they were like-minded, such as being forward thinking and open. Natalia (a 23-year-old woman) who followed several VIs (e.g., Lil Miquela, Shudu, or Bermuda), put it this way: “I believe … the followers feel resonated, like they resonate with the personalities of the influencers, that is how I/they will continue to follow them.”

Perceptions of Virtual Influencers and Mitigating Factors of the Uncanny Valley Effect

In answering Research Questions 2 and 3, two major groups of perceptions emerged from our analysis. The first group contained most of the participants, who perceived VIs as uncanny and eerie when they appeared human-like and artificial at the same time. However, our results also showed a second theme, with most of the participants acknowledging and recognizing VIs’ staged fabrication as frankly fake. Furthermore, we identified two potential moderating factors that eased the negative perceptions of VIs, including curated flaws and self-justification.

Uncanny and Eerie

A majority of the participants described VIs as being uncanny and creepy, and attributed the perceived uncanniness to their high resemblance to human beings. For instance, Jay (a 23-year-old man) who followed Lil Miquela and Maya described these uncanny and eerie feelings: “There’s a bit of that uncanny valley feeling. … But you just can’t put your finger on it, like how her skin is so high resolution like human skin. … A bit creepy.”

Other interviewees expressed similar sentiments, attributing the perceived eeriness to the VIs’ humanness that makes them seem too close to humans. Eric (a 23-year-old man) who followed Lil Miquela mentioned that every time he checked her posts, he felt “it’s kind of creepy that it’s done so well.” Furthermore, some interviewees indicated that the way the VIs interacted with followers closely resembled that of SMIs and their followers, which also made them creepy. For instance, Emily (a 23-year-old woman) who followed Lil Miquela and Shudu described it as: “I think it is very uncanny when I see them, how she talks. … I honestly don’t think there’s a huge difference between virtual and humans. And that’s what kind of scares me.”

Authentically Fake

Although most of the interviewees considered VIs uncanny and eerie when they attempted to “pass” as humans, the majority of the interviewees also easily recognized that VIs were ostensibly staged and fabricated and didn’t mind the VIs trespassing on humanness. This echoes earlier findings, which argued that VIs are “authentically fake” (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Wills Citation2019), and that followers know they are consuming staged content and narratives. As Paul (a 28-year-old man) who followed Lil Miquela and Imma.gram described it:

You can roughly tell that they are fake. … I don’t know whether it is some law out there that says you cannot make the virtual influence as a human. But I thought that part was interesting, cuz I believe with the technology in CGI nowadays you can technically create people that look 100% like a real human. …

Most interviewees mentioned that they went back and forth between feeling uncanny toward VIs and reminding themselves of the VIs’ fabricated and robotic nature. As Natalie (a 23-year-old woman) who followed multiple VIs (Lil Miquela, Shudu, Imma.gram, and Bermuda) mentioned, she always realized that VIs were fake and staged, but at times she needed to remind herself of this fact when VIs looked too human-like.

Mitigating Factors (Moderators) of the Uncanny Valley Effect

Our analysis also found two potential moderating factors, curated flaws and self-justification, which could decrease the negative effect of the uncanny valley that was caused by VIs reaching a threshold of similarity to humans.

Curated Flaws

VIs’ possessing physical human flaws contributed to a high level of acceptance of their appearance, despite the eeriness, with some interviewees noting the importance of the VIs not looking too perfect or doll-like. The presence of human-like flaws is shown to alleviate the eeriness created by the uncanny valley effect. Both Farhan (a 22-year-old man) and Jia Hao (a 25-year-old man) concurred that adding a few “flaws” here and there (e.g., hair, gap between front teeth, armpit hair, or a flat chest) made VIs less creepy and more relatable. Similarly, Jasmine (a 23-year-ild woman) agreed with this sentiment and mentioned: “I think why Lil Miquela’s appearance resonated the most with me is because she doesn’t look perfect. … So I think the key to having a successful CGI influencer is when they have flaws, like human flaws.”

Self-Justification

All participants still follow VIs despite most recognizing the presence of uncanniness and eeriness in the VIs. The interviewees attributed this to self-justification in believing that there is a person or a team managing the VI’s account. This self-justification validates their actions and behaviors in their acceptance of VIs (Goethals Citation1992). Some participants, such as Chole (a 21-year-old woman) felt that certain of Lil Miquela’s body parts belonged to real people. She supported this with her decreased aversion toward VIs, despite the fact that she still perceived Lil Miquela to be eerie: “Her Instagram photos are quite obvious that there’s a human model and like somebody just like, put a lot of effort to touch up her face to make it look like 3D.”

Other interviewees, such as Eric (a 23-year-old man) and Angeline (a 21-year-old woman) who both followed Lil Miquela firmly believed that there was a real person or a team behind the VI, controlling her staged content and narrative on a daily basis, which made them feel as if they were dealing with a human-like influencer and not an eerie robot.

The Marketing Effectiveness of VIs

To answer Research Question 4, our analysis found significant outcomes concerning VIs’ marketing effectiveness on brand awareness, brand image, and purchase intention.

Brand Awareness

Almost all interviewees expressed that using VIs as a marketing tool had a positive impact on brand awareness, as they often recognized new brands or recalled familiar brands that engaged in sponsored campaigns involving VIs. For instance, one interviewee, Joey (a 24-year-old woman) revealed that she may not purchase the VI-promoted products, but “it’s just the initial awareness of the brand/product or something like that.” Others mentioned that the concept of VIs’ using a certain product/brand will boost brand visibility and recognition among consumers (Kelly, a 24-year-old woman). Indeed, taking into account the large following that top VIs have, interviewees also believed that using VIs could help to raise brand awareness. Hafiz (a 25-year-old man) who followed Kizuna AI shared: “The following [of VIs] is usually quite large … having a VI to showcase or promote their brand can result in a very good turnout for the brand itself.”

Brand Image

Interviewees commonly believed VIs could boost brand image and help the brand to project a forward-thinking and trendy image. For instance, Sarah (a 23-year-old woman) believed that employing VIs in campaigns was “quite dare devil” for brands, and it distinguished one brand from competing others. Similarly, Eric (a 23-year-old man) mentioned that VIs could help brands to build image, as VIs “represent invisibly a kind of advancement in technology” and that brands can associate themselves with the high-tech image that VIs provide. Furthermore, Leonard (a 23-year-old man) also pointed out that VIs could help with brand image and said: “CGI influencers seem pretty like futuristic, so maybe hiring VIs would help with their brand image in some way.”

Purchase Intentions

Almost all of the interviewees indicated that VIs have barely any influence on their own intention to purchase VI-sponsored products. None of them reported ever having purchased anything as a result of the VIs’ recommendations or sponsored posts. This indicates that VIs have a limited effect on their followers’ purchase intentions or past purchases. We narrowed the reasons for this result down to lack of authenticity, low similarity, and weak parasocial relationship.

Authenticity

Almost all interviewees highlighted VIs’ lack of authenticity (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Robinson Citation2020), which greatly contributed to their low intention to purchase VI-promoted products. Authenticity refers to being real or original; that is, “not to be a copy or an imitation” (Grayson and Martinec Citation2004, 297). Many interviewees mentioned their hesitancy in trusting VIs, as they were unable to use the promoted products themselves and did not have real experiences to share. Stephanie (a 23-year-old woman) said, regarding skincare products, “she [Lil Miquela] doesn’t actually have skin and how does she try it?” Similarly, Christine (a 23-year-old woman) mentioned she wouldn’t trust what VIs had to say about products, as “they are not even real” and “can’t even test the product.” Moreover, Joey (a 24-year-old woman) clarified that if the promoted product was congruent with the VIs’ expertise (e.g., music), it might be appealing to her, but any physical products (e.g., a car or beauty products) that were not congruent with the VIs’ fabricated nature would not drive her to purchase.

Similarity

A majority of the interviewees felt that the VIs who they followed did not have relatable traits or likes. They mentioned that the most popular VIs were based in the U.S. market, which has weather, dressing styles, consumption habits, and trends that are different from the Singaporean market. For instance, Emily (s 23-year-old woman) who followed Lil Miquela and Shudu said, “Lil Miquela is mostly meant for winter wear” and doesn’t fit with the local tropical weather (in Singapore). Jia Yi (a 20-year-old woman) felt that VIs’ “consumption habits are very different” and so were the used products. Furthermore, David (a 21-yeat-old man) mentioned that if the VI (Lil Miquela) was “promoting something local, then probably it would have a greater influence” on him.

Parasocial Relations

Our findings show that most interviewees found it difficult to build close or intimate relations with VIs. We refer to this as a parasocial relation – an illusory and lasting relation between influencers and followers (Escalas and Bettman Citation2017; Lou Citation2022). Most interviewees said that there was a natural barrier to building strong parasocial relations with VIs, as they were fake and staged, which contributed to their low likelihood to purchase products recommended by VIs.

Ashley (a 24-year-old woman) said she did not connect with Lil Miquela on a deeper emotional level, compared to human influencers, as she felt disconnected from VIs. Similarly, Xin Yi (a 20-year-old woman) explained that she felt part of a human influencer’s narrative, but not knowing who was actually controlling the VIs made it difficult for her to bond with them. Sarah (a 23-year-old woman), shared a similar view:

Interacting with a human social media influencer, sometimes they can start to feel like your friend, like it’s a parasocial relationship where you feel very close to them even though they don’t know you. But I guess for virtual influencer, I don’t think you ever established that kind of closeness because, you know, it’s like being catfished.

Table 2. Summary of the primary codes, themes, and short quotes.

General Discussion

With the increasing influence and popularity of VIs, we thought it critical to understand the fundamental issues related to consumer behavior and advertising effectiveness. The current literature on VIs is quite limited and nascent. It focuses mostly on comparing the efficacy of VIs to human influencers (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Thomas and Fowler Citation2021), offering a qualitative analysis of VIs’ marketing effectiveness (Moustakas et al. Citation2020), explicating the influence of VIs on public relations practices (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021), examining the parasocial interactions between VIs and followers (Molin and Nordgren Citation2019), and providing a discussion of the ontology and ethics related to VIs (Robinson Citation2020).

Our findings advance the extant literature on influencer advertising in general and on VIs in particular. This study’s theorization of the six primary motivations for following VIs serves as a foundation for future research to explore the potential theoretical connections between U&G components and VIs’ advertising effectiveness. More importantly, the current findings offer validated evidence of the uncanny valley theory. However, they also provide a much more nuanced explication of the complex human reactions to human-like robots (VIs), which entails a combination of perceived uncanniness and fascination, as well as fear and intrigue. Future research may extend the scope of the uncanny valley theory and explore new directions delineating human reactions and behaviors. Finally, we elucidated the varying degrees of influence of VIs on varied advertising outcomes and the underlying mechanisms that account for purchase intention, which serve as a road map for future empirical research. More broadly, the findings add to the growing literature on influencer advertising and social media marketing, by offering more nuanced differences. On one hand, this study echoes most of the existing findings regarding the factors that affect the efficacy of SMIs: authenticity, similarity, and parasocial relations (e.g., Boerman and Van Reijmersdal Citation2020; Lee et al. Citation2022; Lou Citation2022; Lou and Yuan Citation2019). On the other hand, it also provides a more nuanced explication of the unique role that VIs play in the effectiveness of social media advertising.

Theoretical Contributions

Viewed holistically, we (1) uncovered the primary motivations for following VIs via the lens of U&G, (2) categorized followers’ reactions to VIs using assumptions from the uncanny valley theory, and (3) explicated the efficacy of VIs and the possible mechanisms that account for VIs’ influence on purchase intention. In particular, we argued that the six motivations – novelty, information, entertainment, surveillance, esthetics, and integration and social interaction – served as precursors to followers’ engaging with VIs. During this process, followers responded to the VIs’ narrative and curated contents, and drew conclusions that were primarily shaped by its prevailing uncanniness and eeriness, as well as the novelty factor (Robinson Citation2020). Given that the overall sentiment toward VIs included perceived uncanniness and recognizing them as a transparent fabrication, we further mapped out the possible moderators – curated flaws and self-justification – that can alleviate the uncanniness and help with acceptance of VIs. We then drew theoretical links between consumers’ reactions and advertising effectiveness by focusing on three particular marketing outcomes – brand awareness, brand image, and purchase intention. Following that, we explicated the varying roles of VIs in each of the outcomes while providing possible explanatory mechanisms for purchase intention – authenticity, similarity, and parasocial relations. We elaborate on these findings below.

Our findings advance the literature on U&G and offer more granular categories in the VI context. First, Chia (Citation2020) mentioned novelty as a reason for VIs’ popularity, which was supported by our results. Echoing earlier literature on the motivations for following SMIs (Morton Citation2020), we found that information seeking emerged as one of the major motivations of following VIs. Interviewees, who had prior interests, such as CGI technology, robotics, and/or Japanese culture, were motivated to follow VIs. Second, our findings regarding entertainment as motivation were in line with previous literature on social media use and the following of SMIs (e.g., Morton Citation2020). It is not surprising that VIs can provide similar entertainment gratification as human influencers do. Third, Morton (Citation2020) described “surveillance” as a motivation for following SMIs, to monitor their lives. Our findings further support this, as we found that participants followed VIs to see their development and to get updates on the latest trends. Furthermore, in the same way as SMIs often serve as inspiration to their followers (Morton Citation2020), we found it understandable that esthetics is a motivation that was mentioned by our interviewees. Many of them stated that the VIs’ attractive visuals were a factor, which echoes the findings of Jang and Yoh (Citation2020), who found that the majority of their respondents preferred VIs with visuals that appealed to them or that fit society’s ideals.

Finally, we uncovered integration and social interaction as another primary motivation. Integration and social interaction motivation describes media gratifications involving other people, including gaining a sense of belonging, connecting with like-minded others, and seeking (emotional) support and companionship (Muntinga, Moorman, and Smit Citation2011). Our findings revealed that most of the interviewees followed VIs because they either resonated with the social values that the VIs advocated (e.g., racial justice and gender equality), or they liked the narrative or personalities that the VIs presented. This is in line with earlier findings concerning how integration and social interaction motivation drives social media users to engage with fan clubs on social media (Vale and Fernandes Citation2018). It is understandable that followers like to connect with VIs because of shared values and perspectives, as well as the feeling that they are alike.

Our second major finding relates to how we provided evidence to the uncanny valley theory and how we identified two potential moderators that can ease the uncanny valley’s negative impact (e.g., Ho and MacDorman Citation2010; Mathur and Reichling Citation2016; Mori Citation1970). Based on our findings, the majority of our interviewees perceived VIs to be uncanny and creepy when their appearance resembled humans too closely. Thus, our findings contribute to the literature on the uncanny valley theory and VIs (Arsenyan and Mirowska Citation2021; Block and Lovegrove Citation2021; Molin and Nordgren Citation2019). Previous literature found that consumers have a greater acceptance of VIs that look human-like, but react negatively when the physical resemblance is too accurate (Molin and Nordgren Citation2019). Our findings further showed that participants had adverse reactions to VIs whose behaviors (e.g., interactions) closely resembled that of human influencers.

However, despite the generally negative reactions toward the uncanniness of virtual influencers, our interviewees showed a certain level of acceptance toward them by acknowledging them to be authentically fake. This echoes what Block and Lovegrove (Citation2021) argued that VIs’ transparent uncanniness and humanness together makes them both eerie and appealing. This mixed “fear and fascination” experience through the uncanny valley storyline may have contributed to followers’ acceptance of VIs (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021, 271). Previous studies have attempted to explore the reasons for the acceptance of robots in general (Wirtz et al. Citation2018), and our research further advances the current literature by exploring the moderators that contribute to consumers’ decreased uncanniness and creepiness specific to VIs (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021). Our findings show two main mitigating factors: curated flaws and self-justification. The interviewees mentioned that the uncanniness was lessened when the influencers portrayed human flaws and nonideal beauty norms, such as VIs’ freckles, armpit hair, not-so-perfect hair, or the gap between their front teeth, all of which contributed to an increased liking of VIs. We also found that many participants perceived VIs to be less uncanny when they held on to the thought that a real human being or a team was behind the VI and was controlling it. Followers constantly engage in this self-justifying process to make conflicting cognitions (Goethals Citation1992) fit – VIs being uncanny and VIs being controlled by real humans – which allows them to follow VIs continually and, thus, to accept their fabricated existence. Given followers’ overall sentiment toward VIs, we moved on to investigate their influence on advertising effectiveness and the underlying mechanisms that might account for purchase intention below.

Indeed, we found that VIs are beneficial to boosting brand awareness and building brand image, but lack the persuasive ability to influence purchase intention. Furthermore, we identified three mechanisms – authenticity, similarity, and parasocial relations – that explicate this latter finding. The interviewees mentioned that VIs were effective marketing tools for building brand awareness for new brands or established brands, and that VIs could also help brands to project a futuristic or trendy image because of the novelty of this concept (e.g., Moustakas et al. Citation2020; Robinson Citation2020). It is not surprising to learn that VIs can draw attention to sponsored brands and increase brand visibility because of their novelty factor or shock value (Robinson Citation2020), which also helps a given brand to associate their image with the high-tech or forward-thinking perception that is intrinsic to CGI/AI technology. These findings are largely aligned with Thomas and Fowler’s (Citation2021) arguments regarding the positive effect of VIs on brand attitudes. However, our interviewees revealed the limited effect VIs had had on their past purchases and purchase intention toward VI-sponsored products. The reasons for this included a lack of authenticity and similarity – which supports the findings of Molin and Nordgren (Citation2019) and Moustakas et al. (Citation2020). In the past, VIs have been criticized for lacking authenticity and reliability, as their narrative and personalities are fabricated and staged (e.g., Block and Lovegrove Citation2021; Molin and Nordgren Citation2019; Moustakas et al. Citation2020). Although Block and Lovegrove (Citation2021) argued that consumers have been treating the concept of authenticity differently, and that Lil Miquela is “authentic in her own digital context and more” by creating consistent and ongoing narrative (283), our interviewees revealed that authenticity – authentic views and experiences – remains a key factor in affecting their purchase intentions. The fact that similarity emerged as a key mechanism influencing purchase intention also concurred with Lou and Yuan’s (Citation2019) findings, which argued that perceived similarity to SMIs positively shaped follower trust and subsequent purchase intentions.

Furthermore, although VIs have been found to engage in parasocial interactions with followers spontaneously (Block and Lovegrove Citation2021), our results echoed prior findings by showing that our interviewees found it either difficult to build profound emotional bonds with VIs (Moustakas et al. Citation2020) or view VIs as “more social-psychologically distant than a human influencer” (Sands et al. Citation2022, 1733). This deviates from the current findings on the intimate, interactive, and co-created trans-parasocial relations found between SMIs and their followers (Lou Citation2022). However, it is not surprising that followers are not able to engage with VIs in the same way as they do with human influencers. For example, they won’t be able to meet up with VIs offline or seamlessly engage in their daily life narrative (since it is all manufactured and supplied by the agencies/controllers behind the VIs). Given the important role of parasocial relations in followers’ purchase intentions (Lou and Kim Citation2019), this can partially explain the limited influence that VIs have on followers’ purchase intentions.

Practical and Managerial Implications

The rich findings of this research can help the creators of VIs to engage better with followers, assist brands in strategizing their campaigns involving VIs, and point toward regulation directions for legislators in the following ways. First, on one hand, the creators of VIs can gain more followers by leveraging followers’ motivations, including by crafting informative, entertaining, or esthetic posts, by regularly updating followers regarding VIs’ statuses, and by curating unique personalities or advocating social issues to attract like-minded followers. On the other hand, the creators of VIs can alleviate the perceived eeriness of VIs by installing clear physical flaws that make the VIs appear less idealistic. Creators can also be transparent about their operation of VIs – namely, by showing that they are staged and controlled by humans.

The brands or advertisers that employ VIs in campaigns should be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of VIs. While our interviewees all mentioned that VIs’ narrative and content were easier to control, brands should also acknowledge the limited effect that VIs have on advertising outcomes. Brands can employ VIs to attract attention to their brands or products to a certain extent, but they should try to stay away from hiring VIs for physical products that require authentic human experiences. Brands should also hire VIs that resemble the demographics or consumption habits of their target consumers and use activities that facilitate and foster a deeper VI-consumer bond to achieve better advertising outcomes. Finally, legislators could attend to the trust issues or moral ethics involving VIs to protect consumers. For example, upfront disclosure regarding the robotic nature of VIs should be required on social media. Clear regulations regarding the blurring of the line between VIs’ curated narratives/content and deception should be drawn, especially when it comes to sponsored products (e.g., VIs should not forge fake experiences regarding product use or functions and peddle them).

Limitations and Future Research

The current study is not without its limitations. First, we recognize that we used snowball sampling, which may bring in an overrepresentation of a single, networked group (young adults), so the findings may not be generalizable to a large population. Future research should employ more diverse samples to further validate the findings. Second, our interviewees indicated that they followed VIs across different social media platforms. The varying affordances and characteristics of each platform can shape users’ usages and gratifications differently. Future research should take platform-related factors into consideration. Third, our study focused on the perceptions of followers. Future research could consider tapping into industry perspectives and also the VIs themselves (or those who create and control them) to gain more insight. Moreover, most of our participants knew or followed only the well-known VIs such as Lil Miquela, Shudu, and Imma.gram. Future research might recruit a more diverse sample to provide more in-depth insight into VIs, ranging across a continuum of humanness (from anime-like to human-like). Although our current qualitative results show followers found it difficult to build profound relations with VIs, future research could delve deeper to explore the potential contributing factors, including VIs’ interaction styles (varying from personable to robotic) (Thomas and Fowler Citation2021), source credibility (Molin and Nordgren Citation2019), and disclosure (Robinson Citation2020). The current findings suggest that the novelty factor of VIs can be efficient in raising brand awareness. Future research should conduct a longitudinal analysis to see whether and how long this effect is sustained. Future research could also offer more insight into how VI marketing works for brands at the cognitive level (e.g., brand attitude, brand awareness, and brand image) and provide more a nuanced understanding of the psychological mechanisms underlying these cognitive outcomes. Finally, future research could also explore how followers attribute responsibility to VIs (vs. human influencers), given that they are staged and crafted, without having full agency. In a similar vein, how consumers formulate trust or how trust is preserved for VIs in this new era is also worth investigating.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The funders did not play any role in the entire research process. We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (42.5 KB)Acknowledgment

We thank the editors and reviewers whose comments have greatly helped us in revising this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chen Lou

Chen Lou (Ph.D., Michigan State University) is Assistant Professor of Integrated Marketing Communication, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

Siu Ting Josie Kiew

Siu Ting Josie Kiew (B.A., Nanyang Technological University) is a student, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

Tao Chen

Tao Chen (Ph.D., Chinese University of Hong Kong) is Associate Professor, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University.

Tze Yen Michelle Lee

Tze Yen Michelle Lee (B.A., Nanyang Technological University) is a student, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

Jia En Celine Ong

Jia En Celine Ong (B.A., Nanyang Technological University is a student, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

ZhaoXi Phua

ZhaoXi Phua (B.A., Nanyang Technological University) is a student, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University.

References

- Abelman, R. 1987. “Religious Television Uses and Gratifications.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 31 (3):293–307.

- Alhabash, S., and M. Ma. 2017. “A Tale of Four Platforms: Motivations and Uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among College Students?” Social Media + Society 3 (1). 10.1177/2056305117691544.

- Arsenyan, J., and A. Mirowska. 2021. “Almost Human? A Comparative Case Study on the Social Media Presence of Virtual Influencers.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 155:102694.

- Bakker, D. 2018. “Conceptualising Influencer Marketing.” Journal of Emerging Trends in Marketing and Management 1 (1):79–87.

- Baklanov, N. 2019. “The Top Instagram Virtual Influencers in 2019.” Hype Auditor. https://hypeauditor.com/blog/the-top-instagram-virtual-influencers-in-2019/

- Barreda, A. A., A. Bilgihan, K. Nusair, and F. Okumus. 2015. “Generating Brand Awareness in Online Social Networks.” Computers in Human Behavior 50:600–09.

- Block, E., and R. Lovegrove. 2021. “Discordant Storytelling, ‘Honest Fakery’, Identity Peddling: How Uncanny CGI Characters Are Jamming Public Relations and Influencer Practices.” Public Relations Inquiry 10 (3):265–93.

- Boerman, S. C., and E. A. Van Reijmersdal. 2020. “Disclosing Influencer Marketing on YouTube to Children: The Moderating Role of Para-Social Relationship.” Frontiers in Psychology 10:3042.

- Biel, A. L. 1992. “How Brand Image Drives Brand Equity.” Journal of Advertising Research 32 (6):6–12.

- Boyatzis, R. E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., and A. Følstad. 2017. “Why People Use Chatbots.” In International Conference on Internet Science, 377–92. Cham: Springer.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101.

- Brooks, G., J. Drenten, and M. J. Piskorski. 2021. “Influencer Celebrification: How Social Media Influencers Acquire Celebrity Capital.” Journal of Advertising 50 (5):528–47.

- Brown, D., and S. Fiorella. 2013. Influence Marketing – How to Create, Manage, and Measure Brand Influencers in Social Media Marketing. Indianapolis: Que Publishing.

- Burleigh, T. J., J. R. Schoenherr, and G. L. Lacroix. 2013. “Does the Uncanny Valley Exist? An Empirical Test of the Relationship between Eeriness and the Human Likeness of Digitally Created Faces.” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (3):759–71.

- Campbell, C., and J. R. Farrell. 2020. “More than Meets the Eye: The Functional Components Underlying Influencer Marketing.” Business Horizons 63 (4):469–79.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage.

- Chia, J. 2020. “Human-Like but Not Real: Virtual Influencers Are Changing Social Media.” Vulcan Post. https://vulcanpost.com/714814/virtual-influencers-social-media-singapore/

- Croes, E., and J. Bartels. 2021. “Young Adults’ Motivations for following Social Influencers and Their Relationship to Identification and Buying Behavior.” Computers in Human Behavior 124:106910.

- De Veirman, M., V. Cauberghe, and L. Hudders. 2017. “Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (5):798–828.

- Del Rowe, S. 2019. “Get Started with Natural Language Content Generation.” EContent 42 (3):17–21.

- Djafarova, E., and C. Rushworth. 2017. “Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users.” Computers in Human Behavior 68:1–7.

- Dodds, S., and A. C. Hess. 2021. “Adapting Research Methodology during COVID-19: Lessons for Transformative Service Research.” Journal of Service Management 32 (2):203–17.

- Drenten, J., and G. Brooks. 2020. “Celebrity 2.0: Lil Miquela and the Rise of a Virtual Star System.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (8):1319–23.

- Erkan, I., and C. Evans. 2018. “Social Media or Shopping Websites? The Influence of eWOM on Consumers’ Online Purchase Intentions.” Journal of Marketing Communications 24 (6):617–32.

- Escalas, J. E., and J. R. Bettman. 2017. “Connecting with Celebrities: How Consumers Appropriate Celebrity Meanings for a Sense of Belonging.” Journal of Advertising 46 (2):297–308.

- Esseveld, N. 2017. “Why Goals Matter to Influencer Marketing Success: Twitter Business.” Twitter. https://business.twitter.com/en/blog/Why-goals-matter-to-influencer-marketing-success.html

- Evans, N. J., J. Phua, J. Lim, and H. Jun. 2017. “Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 17 (2):138–49.

- Faddoul, G., and S. Chatterjee. 2020. “A Quantitative Measurement Model for Persuasive Technologies Using Storytelling via a Virtual Narrator.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 36 (17):1585–604.

- Goethals, G. 1992. “Dissonance and Self-Justification.” Psychological Inquiry 3 (4):327–9.

- Grayson, K., and M. Martinec. 2004. “Consumer Perceptions of Iconicity and Indexicality and Their Influence on Assessments of Authentic Market Offerings.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (2):296–312.

- Hermanda, A., U. Sumarwan, and D. N. Tinaprillia. 2019. “The Effect of Social Media Influencer on Brand Image, Self-Concept, and Purchase Intention.” Journal of Consumer Sciences 4 (2):76–89.

- Ho, C. C., and K. F. MacDorman. 2010. “Revisiting the Uncanny Valley Theory: Developing and Validating an Alternative to the Godspeed Indices.” Computers in Human Behavior 26 (6):1508–18.

- Hwang, K., and Q. Zhang. 2018. “Influence of Parasocial Relationship between Digital Celebrities and Their Followers on Followers’ Purchase and Electronic Word-of-Mouth Intentions, and Persuasion Knowledge.” Computers in Human Behavior 87:155–73.

- Jang, H. S., and E. Yoh. 2020. “Perceptions of Male and Female Consumers in Their 20s and 30s on the 3D Virtual Influencer.” The Research Journal of the Costume Culture 28 (4):446–62.

- Jeans, D. 2020. “Companies Will Spend $50 Million on Artificial Intelligence This Year with Little to Show for It.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidjeans/2020/10/20/bcg-mit-report-shows-companies-will-spend-50-billion-on-artificial-intelligence-with-few-results/?sh=26738ff47c87

- Jin, S. V., E. Ryu, and A. Muqaddam. 2021. “I Trust What She’s #Endorsing on Instagram: Moderating Effects of Parasocial Interaction and Social Presence in Fashion Influencer Marketing.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 25 (4):665–81.

- Kätsyri, J., K. Förger, M. Mäkäräinen, and T. Takala. 2015. “A Review of Empirical Evidence on Different Uncanny Valley Hypotheses: Support for Perceptual Mismatch as One Road to The Valley of Eeriness.” Frontiers in Psychology 6:390.

- Katz, E. 1959. “Mass Communication Research and the Study of Culture: An Editorial Note on a Possible Future for This Journal.” Studies in Public Communication 2:1–6.

- Katz, E., J. G. Blumler, and M. Gurevitch. 1973. “Uses and Gratifications Research.” Public Opinion Quarterly 37 (4):509–23.

- Ki, C. W. C., L. M. Cuevas, S. M. Chong, and H. Lim. 2020. “Influencer Marketing: Social Media Influencers as Human Brands Attaching to Followers and Yielding Positive Marketing Results by Fulfilling Needs.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 55:102133.

- Kotler, P. 2001. A Framework for Marketing Management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lee, J. A., S. Sudarshan, K. L. Sussman, L. F. Bright, and M. S. Eastin. 2022. “Why Are Consumers following Social Media Influencers on Instagram? Exploration of Consumers’ Motives for following Influencers and the Role of Materialism.” International Journal of Advertising 41 (1):78–100.

- Lee, Y., and J. Koo. 2015. “Athlete Endorsement, Attitudes, and Purchase Intention: The Interaction Effect between Athlete Endorser-Product Congruence and Endorser Credibility.” Journal of Sport Management 29 (5):523–38.

- Lou, C. 2022. “Social Media Influencers and Followers: Theorization of a Trans-Parasocial Relation and Explication of Its Implications for Influencer Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 51 (1):4–21.

- Lou, C., and H. K. Kim. 2019. “Fancying the New Rich and Famous? Explicating the roles of Influencer Content, Credibility, and Parental Mediation in Adolescents' Parasocial Relationship, Materialism, and Purchase Intentions.” Frontiers in Psychology, 10:2567. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02567

- Lou, C., and S. Yuan. 2019. “Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 19 (1):58–73.

- MacDorman, K., and D. Chattopadhyay. 2016. “Reducing Consistency in Human Realism Increases the Uncanny Valley Effect; Increasing Category Uncertainty Does Not.” Cognition 146:190–205.

- Mathur, M., and D. Reichling. 2016. “Navigating a Social World with Robot Partners: A Quantitative Cartography of the Uncanny Valley.” Cognition 146:22–32.

- Mediakix. 2019. “What Are CGI Influencers?” Meet Instagram’s Virtual Models. https://mediakix.com/blog/cgi-influencers-instagram-models/

- Mende, M., M. L. Scott, J. V. Doorn, D. Grewal, and I. Shanks. 2019. “Service Robots Rising: How Humanoid Robots Influence Service Experiences and Elicit Compensatory Consumer Responses.” Journal of Marketing Research 56 (4):535–56.

- Miyake, E. 2022. “I Am a Virtual Girl from Tokyo: Virtual Influencers, Digital-Orientalism and the (Im)Materiality of Race and Gender.” Journal of Consumer Culture, 146954052211171.

- Molin, V., and S. Nordgren. 2019. “Robot or Human? – The Marketing Phenomenon of Virtual Influencers – A Case Study about Virtual Influencers’ Parasocial Interaction on Instagram.” Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University.

- Morency, C. 2018. “Meet Fashion’s First Computer-Generated Influencer.” Business of Fashion. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/intelligence/meeting-fashions-first-computer-generated-influencer-lil-miquela-sousa

- Mori, M. 1970. “Bukimi No Tani the Uncanny Valley.” Energy 7:33–5.

- Morton, F. 2020. “Influencer Marketing: An Exploratory Study on the Motivations of Young Adults to Follow Social Media Influencers.” Journal of Digital & Social Media Marketing 8 (2):156–65.

- Mou, Y., K. Xu, and K. Xia. 2019. “Unpacking the Black Box: Examining the (de) Gender Categorization Effect in Human-Machine Communication.” Computers in Human Behavior 90:380–7.

- Moustakas, E., N. Lamba, D. Mahmoud, and C. Ranganathan. 2020. “Blurring Lines between Fiction and Reality: Perspectives of Experts on Marketing Effectiveness of Virtual Influencers.” In 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Mrad, M., Z. Ramadan, and L. I. Nasr. 2022. “Computer-Generated Influencers: The Rise of Digital Personalities.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 40 (5):589–603.

- Muntinga, D. G., M. Moorman, and E. G. Smit. 2011. “Introducing COBRAs: Exploring Motivations for Brand-Related Social Media Use.” International Journal of Advertising 30 (1):13–46.

- Neff, J. 2019. “From Racism to Vegan Cheating, This List Of 10 Influencer Scandals Has It All.” AdAge. https://adage.com/article/year-end-lists-2019/racism-vegan-cheating-list-10-influencer-scandals-has-it-all/2221821

- Nurhandayani, A., R. Syarief, and M. Najib. 2019. “The Impact of Social Media Influencer and Brand Images to Purchase Intention.” Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen 17 (4):650–61.

- Park, J., J. M. Lee, V. Y. Xiong, F. Septianto, and Y. Seo. 2021. “David and Goliath: When and Why Micro-Influencers Are More Persuasive than Mega-Influencers.” Journal of Advertising 50 (5):584–602.

- Pradhan, D., I. Duraipandian, and D. Sethi. 2016. “Celebrity Endorsement: How Celebrity–Brand–User Personality Congruence Affects Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention.” Journal of Marketing Communications 22 (5):456–73.