Abstract

Research has shown that people within society experience sexual attractions to children, and a substantial number of these seek support related to this. However, professional practices around working with minor-attracted persons (MAPs) are variable. Clinicians possess low levels of knowledge about this population and are unclear about the correct treatment goals. In this work we explored the prioritization of different treatment goals by MAPs (n = 150), before investigating the demographic, sexuality-related, and psychological predictors of treatment target prioritization. Self-compassion drove many treatment targets among MAPs. We offer recommendations about how professionals might work collaboratively and effectively with this population.

Introduction

Individuals with a sexual attraction to minors are vilified by society, which is often isolating to those who need support in managing their attractions due to a fear of experiencing social stigma (Grady, Levenson, Mesias, Kavanagh, & Charles, Citation2019; Jahnke, Citation2018; Jara & Jeglic, Citation2021; Lievesley, Harper, & Elliott, Citation2020). The prevalence of minor attraction amongst the general population remains largely unknown due to sampling difficulties (Cantor & McPhail, Citation2016), with it being estimated that up to 5% of adult males may engage in sexual fantasizing involving children during masturbation (Dombert et al., Citation2016). This figure is thought to rise when considering a wider age-range of sexual interests in minors (Bergen, Antfolk, Jern, Alanko, & Santtila, Citation2013; Santtila et al., Citation2015). Seto’s (Citation2017) age-graded model of chronophilias separates sexual attractions to children into different categories, from nepiophilic attractions (i.e., attractions to young infants) to pedophilic attractions (i.e., attractions to prepubescent children) to hebephilic attractions (i.e., attractions to children and young people going through pubertal development). Most of the published literature refers to pedophilia, though this may be due to widespread public and professional conflations between this label, sexual attractions to children more generally, and the act of sexually offending against children (Feelgood & Hoyer, Citation2008; Harper & Hogue, Citation2017; Harrison, Manning & McCartan, Citation2010). In this work, we adopt the umbrella terms of ‘minor attraction’ or ‘minor attracted persons’ (MAPs). These define a sexual attraction to children irrespective of an individual’s primary or preferred age of interest (Walker, Citation2021), owing to the minimal behavioral distinctions between those attracted to pre- and early post-pubescent children (Blanchard et al., Citation2009; Cantor & McPhail, Citation2015), and the often-reported lack of exclusivity in specific chronophilic categories (Blanchard, Citation2010; Lievesley et al., Citation2020; Stephens, Cantor, Goodwill, & Seto, Citation2017; Stephens, Seto, Cantor, & Lalumière, Citation2019).

Negative public attitudes toward MAPs are amplified by the idea that all MAPs molest children, and that all people who molest children are MAPs (Feelgood & Hoyer, Citation2008; Harper & Hogue, Citation2017; Jara & Jeglic, Citation2021). Although reports suggest that a sexual interest toward minors is apparent in less than half of cases where an individual has been convicted of a child sexual offense (McPhail, Olver, Brouillette-Alarie, & Looman, Citation2018; Schmidt, Mokros, & Banse, Citation2013), there remains little separation between offending and non-offending MAPs in both media and academic discourses (Feelgood & Hoyer, Citation2008; Harper & Hogue, Citation2017; Harrison et al., Citation2010; King & Roberts, Citation2017). Despite this societal conflation, there is a growing awareness that many MAPs live crime-free lives (Cantor & McPhail, Citation2016; Seto, Citation2018).

Previous research has reported how a substantial number of MAPs are open to seeking support in the community but face numerous barriers to service access and engagement (Grady et al., Citation2019; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022). In the current work, we focus our attention on such individuals to explore what they perceive their needs to be in treatment contexts. We do this by first exploring the treatment priorities of MAPs, before comparing these data to previously published information about the priorities of professionals who are potentially working with them. We then investigate the predictors of treatment target prioritization among MAPs themselves, so as to provide some guidance about how professionals might structure their work with MAPs in a collaborative and engaging manner, and to enhance service user outcomes.

MAP help-seeking behaviors and treatment targets

To best support MAPs in the community, it is important to consider the identification of appropriate treatment targets (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). For example, the need for mental health support is something that has been identified by MAPs in informal services (B4U-ACT, Citation2011), as well as in peer-reviewed analyses of MAP experiences and desires for help (Dymond & Duff, Citation2020; Grady et al., Citation2019; Houtepen, Sijtsema, & Bogaerts, Citation2016; Jahnke, Schmidt, Geradt, & Hoyer, Citation2015; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). The importance of addressing mental health issues is best highlighted by looking at the prevalence of suicidal ideation and intention among MAPs, with around 40% admitting to experiencing chronic suicidal ideation (Cohen, Ndukwe, Yaseen, & Galynker, Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2020). Research has also shown how MAPs experience high rates of anxiety, depression, and self-hatred (e.g., Jahnke et al., Citation2015; Lievesley et al., Citation2020; Stevens & Wood, Citation2019). Thought suppression is common among MAPs, with this taking many forms, including the active avoidance of children and potential reminders of minor attraction (Lievesley et al., Citation2020) or through problematic levels of substance use (Stevens & Wood, Citation2019; Walker, Citation2021). Such behavior often leads MAPs to become socially isolated and lacking in emotional and social supports (Elchuk, McPhail, & Olver, Citation2022; Jahnke et al., Citation2015). This is concerning purely from a clinical standpoint but can become more so when considering how poor psychosocial functioning and substance misuse are theoretically associated with an individual perpetrating a sexual offense (Ward & Beech, Citation2006; Ward & Siegert, Citation2002). As such, effective early interventions for individuals struggling with issues related to their sexual attractions could prove vital in improving MAPs’ quality of life, in addition to reducing the likelihood that some may go on to commit sexual offenses (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Goodier & Lievesley, Citation2018; Parr & Pearson, Citation2019).

Although mental health targets are commonly reported as the most pressing goals for treatment when working with MAPs, the conflation and theoretical links between minor attraction and the sexual abuse of children often leads people to consider the prospect of altering or extinguishing MAPs sexual attraction patterns as an alternative treatment approach. Despite there being substantial evidence of the immutability and unchangeability of predominant or exclusive sexual attractions to children (see Cantor, Citation2018; Grundmann, Krupp, Scherner, Amelung, & Beier, Citation2016; Seto, Citation2012), some advocate for the elimination of such sexual attraction patterns through aversion or conversion therapies, or via the use of medications that reduce sex drive (for examples, see Fedoroff, Citation2018; Winder et al., Citation2019). Although some of these efforts have appeared to demonstrate success in changing arousal patterns, these have been criticized on methodological and statistical grounds, leading to questions about the reliability of such findings (for a debate, see Cantor & Fedoroff, Citation2018). Such a focus from clinicians on working to control (or, in some cases, change) sexual attractions may not be completely unsurprising owing to the theoretical link between sexual interests (especially those containing paraphilic themes) and sexual offending (e.g., Seto, Citation2019). Some MAPs also appear to recognize a need to control their levels of sexual arousal and may do this by abstaining from masturbation (Stevens & Wood, Citation2019), actively avoiding children (Lievesley et al., Citation2020), or stopping themselves being online where child sexual exploitation material can be accessed (Stevens & Wood, Citation2019).

On the contrary, an emergent body of work with community-based MAPs discusses the successful use of masturbatory fantasies as a coping mechanism, with this acting as a healthy sexual outlet that causes no direct harm to minors (e.g., Bailey, Bernhard, & Hsu, Citation2016; Dymond & Duff, Citation2020; Harper & Lievesley, Citation2022; Houtepen et al., Citation2016). Indeed, the achievement of sexual satisfaction is seen by some theorists as a primary human good, with its attainment being associated with a reduction in the likelihood that somebody will go on to commit a sexual offense (Ward & Marshall, Citation2004). As such there may be ethical and practical discussions to be had between MAPs and treatment providers in relation to the most effective ways to help service users to accept their sexual attractions as a pattern of arousal that is potentially unchangeable over time, and to work with them to develop effective ways of reducing sexual frustration and achieving sexual satisfaction in ways that do not create victims of child sexual exploitation and abuse.

Related to the issue of acceptance is the internalization of social stigma. Although this is associated with the raft of mental health concerns listed earlier (see Elchuk et al., Citation2022; Jahnke, Citation2018; Jahnke et al., Citation2015; Jahnke & Hoyer, Citation2013; Lievesley et al., Citation2020), the internalization of stigma does more than simply reduce somebody’s mood. The internalization process, by definition, has a profound effect on MAPs’ sense of self and their personal identities, leading to feelings of shame (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). In some investigations of convicted individuals, experiences of shame have stopped MAPs from coming forward for support before they committed an offense, leading them to (unsuccessfully, in these cases) try to manage their sexual attractions privately (Levenson, Willis, & Vicencio, Citation2017; Swaby & Lievesley, Citation2022). We know from the literature on desistance from sexual offending that social conditions play a vital role in people’s trajectories into and out of crime (see Göbbels, Ward, & Willis, Citation2012). Applying this principle, Lievesley and Harper (Citation2022) have suggested that social conditions—including levels of public stigma about minor attraction—can block what is referred to as a ‘normalcy’ stage of living as a MAP in the community. This stage is said to be characterized by being able to live in a relatively open manner, disclosing one’s sexual attractions to trusted confidants, and being able to seek and achieve safe and legal forms of sexual satisfaction. However, given the current levels of societal revulsion at minor attraction (see Harper, Bartels, & Hogue, Citation2018; Harper, Lievesley, Blagden, & Hocken, Citation2022; Imhoff, Citation2015; Jahnke, Citation2018; Jahnke & Hoyer, Citation2013), MAPs may benefit from working with professionals about how they can navigate their specific contexts to achieve a sense of normalcy in a safe way.

Barriers experienced when working with healthcare professionals

Although the above treatment targets have been identified in past research, the translation of such ideas into clinical practice has not kept pace. Instead, MAPs report experiencing multiple barriers when thinking about accessing support to manage both their attractions and the psychological experiences related to them. For example, MAPs express concerns about the competence of many healthcare professionals, and a fear that confidentiality may be compromised by professionals who prematurely report individuals to the child protection and law enforcement communities based solely on their attractions (Levenson et al., Citation2017; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). These concerns appear to be valid; in recent work, primary healthcare professionals have been found to exhibit a relatively high degree of willingness to report MAPs to both child protection services and the police after disclosing their sexual attractions, with this willingness increasing further when hearing about masturbation habits and access to children in professional settings (Lievesley, Swaby, Harper, & Woodward, Citation2022b; Roche & Stephens, Citation2022; Stephens, McPhail, Heasman, & Moss, Citation2021). Similarly, social work students in training for their future careers exhibit a willingness to report potential clients to law enforcement agencies because of their sexual attractions to children, even in the absence of any meaningful risk of offending (Walker, Butters, & Nichols, Citation2022).

Such findings highlight the difficulties that MAPs face when navigating health services and support programs and the insecurity that they face in light of such variable reporting practices (Beggs Christofferson, Citation2019). However, even when they are able to confidentially access services, there is another hurdle to overcome in relation to setting appropriate treatment goals (Hardeberg Bach & Demuth, Citation2018; Lawrence & Willis, Citation2021). Establishing a supportive and collaborative therapeutic alliance between MAPs and healthcare providers is crucial in ensuring that sexual attractions to children are managed in the most effective manner possible, that MAPs are supported in their striving for mental wellbeing, and that service users stay engaged with the programs that they are accessing (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022; Piché, Mathesius, Lussier, & Schweighofer, Citation2018). Research with MAPs has established that person-centered approaches to treatment are deemed to be the most successful when looking to cases of formal and informal help seeking (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). This observation is echoed by those providing services (Goodier & Lievesley, Citation2018; Hocken, Citation2018). However, we do not currently have comparative data from MAPs and health professionals to identify areas of target (mis)alignment and to explore how to bring about the kinds of collaborative therapeutic relationships that are so important for effective treatment to be offered (Elvins & Green, Citation2008; Lievesley et al., Citation2022b; Locati, Rossi, & Parolin, Citation2019; Nienhuis et al., Citation2018).

The current research

In this paper we have three key aims. The first is to identify the relative levels of treatment target prioritization among MAPs. Although past research has identified clusters of treatment targets (e.g., addressing mental health deficits) there is no current peer-reviewed evidence about how different treatment targets compare in terms of MAP prioritization. Second, we will explore the levels of (mis)alignment between MAP treatment targets and the prioritization of treatment needs reported by healthcare professionals in recently published work (Lievesley, Harper, & Swaby, Citation2022a). This aim is motivated by previous work showing a discomfort among MAPs about the levels of competence among health professionals in being responsive to their needs (see Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b), but a current lack of directly comparable data. Our final aim is to explore the drivers of MAPs’ treatment targets. That is, it is important to ensure that MAPs are obtaining person-focused care when engaging with professionals, and a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is likely to lead to unsatisfactory outcomes (Goodier & Lievesley, Citation2018). Acknowledging that some MAPs may exhibit different views about what they believe should be a core treatment target, in the second half of this paper we investigate whether sexuality-related variables (e.g., exclusivity of attractions to children) and psychological constructs (e.g., self-compassion, coping strategies, and mental wellbeing) are associated with variations in how different treatment targets are prioritized.

Methods

Participants

The sample was comprised of MAPs drawn from a project exploring help-seeking behaviors and motivations. The project has a dataset of 186 MAPs who have provided information about their histories of help-seeking. We retained those participants who completed the treatment priorities measure embedded within this project, along with relevant psychological scales that we included to explore predictors of help-seeking and treatment target prioritization (see Materials, below). As such, our MAP sample is comprised of 150 participants who were recruited from prominent online peer-support forums for people who experience sexual attractions to children (Mage = 32.8 years, SD = 12.8; 91% male). To protect participant anonymity, we did not ask about MAPs’ geographical locations, nor did we track IP addresses to establish this information.

Materials

Demographics

We asked participants to provide information about their sex and age. We also asked about their relationship status (which we coded after data collection as either ‘not in a relationship’ [0] or ‘in a relationship’ [1]) and whether they had children (coded as either ‘no’ [0] or ‘yes’ [1]).

Treatment target prioritization

We used a 10-item treatment priorities measure adapted from B4U-ACT’s (2011) survey of MAPs. Each item was framed as a potential treatment goal and responded to using a ten-point scale, from 1 (not at all a priority) to 10 (definitely a priority). This measure was originally designed to explore treatment goals related to MAP mental health, but a factor analysis of responses from healthcare professionals reported in Lievesley et al. (Citation2022b) identified three factors: mental health needs (e.g., “To help the patient feel happier or at peace”; α = 0.78), controlling or changing sexual attractions to children (e.g., “To help the patient to extinguish or reduce an attraction to children”; α = 0.82), and living with a stigma (e.g., “To help the patient figure out how to live in society with their sexual attraction”; α = 0.67). One item (“To help the patient deal with their sexual frustration”) was found to be independent of these three factors and is therefore analyzed separately. An average score was calculated for each treatment target factor.

Sexuality-related variables

We asked MAPs about the exclusivity of their sexual attractions by asking them to rate the gendered natures of their attractions to adults and children separately. To do this, we used five-point scales modified from the Kinsey measure of sexual orientation. That is, for adults/children we asked participants if their attractions were to ‘men/boys’, ‘mostly men/boys’, ‘both sexes equally’, ‘mostly women/girls’, or ‘women/girls’. For the adult scale, however, we included a sixth option that indicated no sexual attraction to adults at all. Those who selected this option (19.3%) were coded as exclusively attracted to children.

We also asked participants about their current levels of sexual satisfaction, which they ranked using a single-item on a six-point scale anchored from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied).

Mental wellbeing

To measure MAPs’ general levels of mental wellbeing we used the 14-item Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (Tennant et al., Citation2007). This scale asks participants to rate how often they have experienced a list of states during the preceding two weeks. Each item (e.g., “I’ve been feeling good about myself”) is rated using a five-point scale anchored from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). An average score was computed (α = 0.94), where high scores equate to greater mental wellbeing.

Coping styles

We used the 28-item Brief COPE Inventory (Carver, Citation1997) to measure MAPs’ endorsement of different coping strategies when faced with distressing or stressful circumstances. To simplify the scoring, we used the four-factor version of this measure reported by Baumstarck et al. (Citation2017), which divides the scale into factors for ‘coping via social supports’ (e.g., “I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone”; α = 0.88), ‘problem-focused coping’ (e.g., “I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better”; α = 0.88), ‘coping via avoidance’ (e.g., “I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to make myself feel better”; α = 0.53), and ‘coping via positive thinking’ (e.g., “I’ve been trying to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive”; α = 0.63). Each item was rated using a four-point scale anchored from 1 (I usually don’t do this at all) to 4 (I usually do this a lot). An average score for each form of coping was calculated.

Hope

We used the 12-item Herth Hope Index (Herth, Citation1991) to measure MAPs’ feelings about the future. Each statement (e.g., “I can see possibilities in the midst of difficulties”) was rated using a four-point scale anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). An average score was calculated to produce a score for hope for each participant (α = 0.90).

Self-compassion

We measured MAPs’ levels of self-compassion using the 26-item Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, Citation2003). This scale contains a number of statements (e.g., “I’m kind to myself when I’m experiencing suffering”), against which participants were asked to provide a rating using a five-point scale anchored from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). An average score was computed across all items to provide a composite score for ‘self-compassion’ (α = 0.95).

Perceived stigma

We modified the Stigma and Punitive Attitudes Scale (Imhoff, Citation2015) to measure MAPs’ perceptions of social stigma about pedophilia. This measure is usually used to measure participant-level attitudes about sexual attractions to children, but in this study we asked participants to respond in the manner that they believed the average member of the public would (thus making their score an indicator of perceived stigma, rather than stigma itself). The scale is usually divided into subscales for perceptions of dangerousness (e.g., “Pedophiles are dangerous for children”), intentionality (e.g., “Pedophilia is something that you choose for yourself”), deviance (e.g., “Pedophiles are sick”), and punitive attitudes (e.g., “Pedophiles should be castrated”). Each item was rated using a seven-point scale anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Due to our modified use of the scale we chose to average scores across all items to produce a single composite score for perceived stigma (α = 0.97).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via prominent web forums for people with sexual attractions to children. After giving their consent to take part, all scales were randomized at the participant level to reduce the chances of order effects influencing the data. However, these questions were presented after questions about past help-seeking behavior (these data are not reported here and will be written-up alongside qualitative data about help-seeking histories among MAPs). This procedure was approved by the Nottingham Trent University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee before the start of data collection.

Results

Exploring MAPs’ treatment priorities

As stated previously, all treatment target prioritization scores ranged from 1 (not a priority) to 10 (definitely a priority). Among MAPs there was a clear pattern of treatment target prioritization, with mental health being the highest-rated treatment priority (M = 7.78, SE = 0.16). This was followed by addressing the effects of social stigma (M = 7.04, SE = 0.16), and then working on issues related to sexual frustration (M = 5.72, SE = 0.21). Finally, desiring support in relation to controlling or changing their sexual attractions was the lowest treatment priority for MAPs (M = 3.82, SE = 0.16). There were statistically significant differences in MAPs’ prioritization scores between every treatment target (all ps < .001, see ).

Table 1. Differences in MAP treatment target prioritization.

How well do MAPs’ treatment priorities align with professionals’ targets?

Although studying MAP treatment targets is an important endeavor in its own right, from a clinical perspective it is also interesting to consider the alignment of treatment targets between service users and the professionals who work with them. As such, we sought to supplement the above data with a brief comparative analysis by comparing these scores to previously published data from healthcare professionals. As such, we used data from Lievesley et al. (Citation2022a) as a comparison group to look at the levels of congruence between the treatment targets of MAPs and the professionals that may be responsible for treating them. The healthcare professional sample was originally comprised of 355 professionals, but we included only those who fully completed the same treatment priority measure as the one administered in the current study to MAPs. This led to a final sample of 320 participants, who represented primary medical professionals (e.g., family physicians; n = 88), mental health professionals (e.g., psychotherapists; n = 95), and specialists who work with MAPs in formal services (e.g., prevention or correctional employees; n = 137). Full details about the recruitment of this healthcare professional sample can be found in Lievesley et al. (Citation2022a).

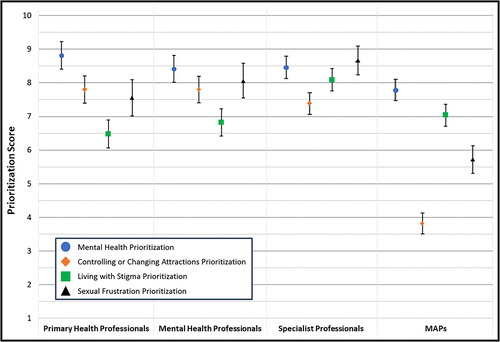

We ran a 4 (Group: MAPs, Primary Care Professionals, Mental Health Professionals, Specialist Professionals; between-subjects) × 4 (Treatment Target: Mental Health Concerns, Control or Change of Attractions, Living with Stigma, Sexual Frustration; within-subjects) analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the free statistical analysis software jamovi. Estimated marginal means for each cell in the analysis are presented in . To preserve clarity in our writing, we present a prose of the between-cell comparisons below, and supplement this with inferential statistics in . All p-values are corrected using the Tukey method to account for multiple comparisons. For additional clarity, we present a plot of these data in .

Figure 1. Treatment prioritization scores, by group. Data represent estimated marginal means surrounded by 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2. Estimated marginal means for treatment prioritization, by group.

Table 3. Differences in treatment target prioritization between MAPs and the professional groups (for initial reporting of the professional data, see Lievesley et al., Citation2022, Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

This first result emerging from the analysis revealed a significant main effect of Group, F(3, 466) = 50.80, p < .001, η2g = 0.14. Here, a comparison of estimated marginal means is not revealing of anything specific, as the outcome variable reflects an average treatment prioritization score across all treatment priorities. Nonetheless, MAPs had a lower composite treatment priority score than all three groups of professionals, while the three professional groups did not significantly differ from each other.

There was also a significant main effect of Treatment Target, F(3, 1398) = 77.50, p < .001, η2g = 0.08. Examining the estimated marginal means, participants were most likely to prioritize MAPs’ mental health concerns, followed by sexual frustration and learning how to live with stigma, with attempts to control or change sexual attractions to children being the lowest priority. Significant differences were observed between all levels of this variable.

Finally, there was a statistically significant interaction, suggesting that treatment target prioritization differed between the groups, F(4, 1398) = 38.40, p < .001, η2g = 0.11. To avoid duplicating results from earlier analyses (see Lievesley et al., Citation2022a), only comparisons between the treatment priorities of MAPs and each professional group are presented here. For comparisons of healthcare professionals’ scores, please see Lievesley et al. (Citation2022a).

In relation to mental health concerns, MAPs scored lower on the treatment prioritization measure than primary care professionals, though all other comparisons were not statistically significant. Mean scores for this treatment target were consistently high. MAPs scored significantly lower than all of the professional groups in relation to the prioritization of controlling or changing their sexual attractions. Those with specialist experience of working with MAPs were more likely than all other groups—including MAPs themselves—to prioritize treatment targets designed to help MAPs to live with a stigmatized sexual attraction pattern. However, MAPs, primary care professionals, and those working in mental health contexts did not differ in their prioritization of these targets. MAPs prioritized working on issues related to sexual frustration to a lesser degree than all professional groups.

Predictors of MAPs’ treatment targets

We conducted a series of linear regression analyses designed to explore variables that predict the prioritization scores for each treatment target among MAPs. This is important as it may not be immediately clear what MAPs would like to target in treatment upon first working with them, but other areas of their lives or clinical profiles might give some indication as to the most appropriate treatment aims to begin to alleviate their distress.

In constructing our regression models, we selected demographic and sexuality-related variables as predictors on the basis of their empirical and theoretical links to treatment needs, alongside all measured psychological variables. As such, we used age, exclusivity of sexual attractions to children, parental status, and relationship status as demographic variables that may be associated with treatment prioritization. There was no formal theoretical reasoning for the inclusion of these variables. However, it was plausible that treatment targets might change over time (e.g., if people go through a process of self-acceptance related to their attractions). Similarly, it is possible that parents (based on their physical proximity to children) and those who are non-exclusively attracted to children (due to their ability to engage in legal sexual relationships) may differ in their treatment targets to non-parents, or those who are exclusively attracted to children. Exclusivity, parental status, and relationship status were entered as categorical (i.e., ‘no/yes’) predictors. We also included sexual satisfaction, mental wellbeing, the four facets of the COPE scale, self-compassion, and perceived social stigma as predictors. We excluded the hope variable from the regression models due to its collinearity with mental wellbeing (see for the correlation matrix), with our selection of wellbeing being driven by a desire to include a variable with broader clinical relevance. With regard to statistical power, we relied on rules-of-thumb to determine whether our sample size was sufficient. This is due to: (1) the exploratory nature of our analysis, and (2) the lack of existing data on the correlations between psychological variables and treatment target prioritization, which made formal power analyses difficult to run. Our sample size exceeds the minimum required under Green’s (Citation1991) ‘N > 50 + 8m’ rule, where N is the minimum viable sample size, and m represents the number of predictors in the model. The minimum viable sample, according to this rule, was 146. Our sample was 150. No p-value adjustments were made within the model owing to the exploratory nature of these analyses (see Rubin, Citation2017). All model coefficients are presented in .

Table 4. Between-variable correlations between treatment target prioritization and relevant demographic, sexuality, and psychological factors.

Table 5. Predictors of mental health related treatment prioritization among MAPs.

Table 6. Predictors of MAPs’ prioritization of treatment targeting controlling or changing their sexual attractions to children.

Table 7. Predictors of prioritizing living with stigma as a treatment goal for MAPs.

Table 8. Predictors of MAPs’ prioritization of sexual frustration concerns as a treatment goal.

The model predicting scores for the prioritization of mental health concerns was statistically significant, adj. R2 = .346, F(12, 105) = 6.16, p < .001. Looking at the model coefficients, prioritizing mental health concerns was higher among MAPs who exhibited a problem-directed approach to coping, and those with reduced levels of mental wellbeing and self-compassion. No other predictors were associated with the targeting of mental health concerns in treatment.

The model predicting scores for the prioritization of controlling or changing sexual attractions was statistically significant, adj. R2 = .119, F(12, 105) = 2.32, p = .011. The targeting of controlling or changing attractions was significantly lower among those who were exclusively sexually attracted to children, as well as those with higher levels of both sexual satisfaction and self-compassion. No other predictors were associated with a desire to control or change sexual attractions among MAPs.

The model predicting scores for the prioritization of treatment that targets how to live with stigma was statistically significant, adj. R2 = .177, F(12, 105) = 3.10, p < .001. Wanting to target how to live with stigma was reduced among those with higher levels of mental wellbeing and self-compassion. However, those who used social supports and problem-based approaches as a means of coping were more likely to want to endorse these more socially oriented treatment targets. No other variables predicted wanting to target living with stigma in treatment.

The model predicting scores for the prioritization of treatment targeting sexual frustration was statistically significant, adj. R2 = .214, F(12, 105) = 3.65, p < .001. This treatment target was prioritized more by those with higher levels of mental wellbeing, but less by those who experienced higher levels of sexual satisfaction and self-compassion. No other variables were associated with wanting to address sexual frustration.

Discussion

In this paper we set out to achieve two goals. The first related to an investigation of the (mis)alignment of treatment target prioritization between MAPs and those from whom they may be seeking support. We identified important differences in how treatment targets were prioritized by these groups. Our second aim related to the identification of patterns in MAPs’ prioritization of treatment goals. That is, to promote person-focused approaches to service provision, we wanted to explore whether particular person-level variables (e.g., exclusivity of attractions, mental wellbeing, coping strategies) might be associated with variations in treatment target prioritization. We found that the prioritization of different treatment targets did differ in conceptually and practically meaningful ways. In the sections that follow, we discuss how our data fit with the existing evidence base, and how they might be used to inform the development of more effective and evidence-informed practices when working with MAPs in the community.

Overview of findings

Overall, we found that MAPs themselves had a lower composite score (observed in the main effect of ‘Group’ in the first ANOVA) in relation to treatment target prioritization than all of the professional subsamples. Although this does not appear to be particularly illuminating at face value, a visual inspection of the graph in shows how this effect is driven by all professional groups reporting that they would prioritize every potential treatment target to a large degree. That is, all average scores on each treatment target were above 6.5 on the 1–10 prioritization scale. As such, this result is deserving of some elaboration. We believe that this indicates a fundamental confusion about the best ways to work with MAPs, and therefore everything is rated as potentially important. However, an alternative explanation is that, in the absence of any case-specific information, everything could be important when planning treatment. Although this may be true in a strictly logical sense, the response scale accompanying each treatment priority item asks about prioritization rather than importance. As such, this lack of specificity in baseline levels of perceived treatment priorities could contribute to a lack of alignment between MAP and professional treatment goals at the beginning of a therapeutic relationship, especially within the context of relatively high clinician stigma, exaggerated risk perceptions, and unclear reporting guidelines (Beggs Christofferson, Citation2019; Lievesley et al., Citation2022b; Stephens et al., Citation2021; Stiels-Glenn, Citation2010).

MAPs were typically focused on addressing mental health needs and treatment targets related to how they can best live within a society that is heavily stigmatizing of their sexual attractions. These data support previously unreviewed informal reports (B4U-ACT, Citation2011) and concur with qualitative and theoretical accounts of MAP experiences and perceived barriers to help-seeking behaviors (Goodier & Lievesley, Citation2018; Grady et al., Citation2019; Houtepen et al., Citation2016; Levenson et al., Citation2017; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022). The prioritization of these treatment targets was predicted by lower levels of wellbeing and self-compassion, as well as more problem-focused approaches to coping. In practice, this indicates that those with lower levels of wellbeing and self-acceptance felt that they needed the most support in relation to mental health concerns and the ability to live with a stigmatized sexual attraction pattern. The observation that problem-focused coping was associated with the prioritization of these two treatment targets, but not with sexuality-related treatment targets, is particularly illuminating. That is, this finding suggests that the most pressing problems that MAPs believe are present in their lives relate to the emotional responses that they experience in relation to their sexual attractions, and not in relation to their (lack of) potential propensities to act on these (see also Dymond & Duff, Citation2020).

There was a rejection of treatment targets related to the controlling or changing of sexual attractions. This concords with prior work that suggests MAPs’ control over sexual thoughts and feelings are not a key concern when compared to their emotional processing of having sexual attractions to children (B4U-ACT, Citation2011; Dymond & Duff, Citation2020). There may also be evidence here of an acknowledgement that sexual attractions to children—particularly when they are the individual’s primary or exclusive attraction—are generally stable across time and resistant to change (Cantor, Citation2018; Seto, Citation2012). This is also captured in the regression analysis, where those with an exclusive attraction to children (and thus no attractions to adults) were less likely to prioritize changing their attractions. The contrast to this is that those who are not exclusively attracted to children might be more amenable to such treatment targets, though, with increasing their levels of sexual attraction to adults comparative to children being a more achievable aim. When MAPs were experiencing greater levels of sexual satisfaction, they were less likely to target controlling or changing their attractions through treatment, which means that their focus can be on living healthier and more broadly fulfilling lives. The observation that lower levels of self-compassion were associated with an increased desire to control or change one’s attractions to children is perhaps indicative of the internalization of stigma (see Jahnke et al., Citation2015; Lievesley et al., Citation2020). Depending upon the exclusivity of somebody’s attractions, it is therefore possible that low levels of self-compassion might lead to unattainable treatment targets, and thus self-compassion and self-acceptance may be an important treatment aim when working with MAPs from the outset of their engagement with support services.

To a lesser degree, MAPs expressed a slight desire to prioritize dealing with sexual frustration. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that the achievement of sexual satisfaction is considered a primary human good that all people strive for to some degree (Ward & Marshall, Citation2004). Predictably, MAPs experiencing lower levels of sexual satisfaction were more likely to prioritize sexual frustration as a treatment target. What is more interesting though are the differing associations between the prioritization of sexual frustration targets with both mental wellbeing and self-compassion. Those with higher levels of wellbeing were more likely to prioritize sexual frustration, possibly because addressing mental health issues are seen as a more fundamental concern. That is, because those wellbeing-related issues feel under some sort of control in these individuals, looking at broader areas of their life (e.g., achieving some degree of sexual satisfaction) becomes more important. However, prioritizing sexual frustration in treatment was less likely among those who scored lower on self-compassion, possibly because when self-compassion is low there are other parts of one’s life (e.g., identity construction and security, mental wellbeing) that are a higher immediate priority than addressing some degree of sexual frustration.

Implications and recommendations for practice

Although these data are interesting from a purely theoretical perspective, there are also significant practice-related points within the arguments that we have made above. As such, in this section we highlight some recommendations for practice that appear to be important when service providers are designing their treatment approaches for MAPs.

When first meeting service users with sexual attractions to children, it is important to keep an open mind about what they might wish to achieve in treatment. For some they will require support with managing their sexual attractions or increasing any attractions to adults that they might already experience. For others the goal might be to develop ways to reach a sense of sexual satisfaction in legal ways. But for most service users, their primary treatment target will be related to improving their sense of self and their mental health. A comprehensive evaluation of their life goals, including their achievement of various primary human goods (Ward, Mann, & Gannon, Citation2007), should act as a guide for determining the kinds of targets that MAPs may wish to set. Tools such as the Good Lives Questionnaire (Harper et al., Citation2021) have recently emerged as one way of quantifying existing levels of such goods. It would also be sensible to explore the exclusivity of MAPs’ sexual attractions to children and having open and compassionate discussions about what is (and, importantly, is not) likely to be achievable. This is particularly the case with service users whose sexual attractions to children are exclusive, as research appears to indicate that changing or eliminating such attractions is difficult (Cantor, Citation2018; Seto, Citation2012).

It may be important to consider the types of coping styles that individual service users tend to enact. From our data we can see how those with problem-focused approaches to coping tend to prioritize issues related to mental health, which may strengthen the argument that mental health concerns are the most pressing problems for MAPs in a general sense. However, professionals might wish to explore problem-focused coping strategies among their service users within their individual context. That is, if working with somebody who takes a problem-focused approach, a logical next step is to explore what that service user sees as the main problems they are experiencing, and then focusing treatment on those issues. For other service users, their coping strategies are more dependent upon social supports. For these individuals it may be more prudent to explore how they can live with societal stigma and negotiate social relationships in ways that lead them to achieve their treatment goals. Encouraging them to think about safe ways of disclosing their attractions and obtaining peer support (e.g., through the selective disclosure to family or friends, or via online peer support forums) might be beneficial with this group. In short, there should be alignment between treatment goals, methods used to achieve these goals, and the preferred coping styles of service users.

The one consistent finding in our data was related to the role of self-compassion in predicting treatment targets. Those with lower levels of self-compassion were less likely to have good mental wellbeing, were more likely to target mental health and stigma-related treatment goals, were more likely to want to control or change their sexual attractions, and were more likely to express a need for help in dealing with sexual frustration. This consistent result suggests that low self-compassion appears to exacerbate all treatment needs in MAPs. For this reason, it is important to consider the cultivation of self-compassion in treatment services with this population. This idea is not new (see Hocken, Citation2018; Lievesley, Elliott, & Hocken, Citation2018), but to our knowledge this is the first dataset that has identified this empirically. One method of achieving self-compassion is via acceptance-based treatment philosophies. This approach encourages service users to adopt a flexible mindset that allows them to be open to the integration of undesired aspects of their identities, and to work on the elimination of feelings of shame and guilt (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masunda, & Lillis, Citation2006). Based on the data presented here, we believe that adopting acceptance-based methods in MAP-directed support services is likely to be the most suitable treatment approach, irrespective of the specific treatment goals being pursued.

As has been identified elsewhere (e.g., Lievesley et al., Citation2022b; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022; Stephens et al., Citation2021), there is an urgent need to develop professionals’ levels of competence and comfort in working with MAPs. In addition to low levels of basic knowledge about minor attraction (Lievesley et al., Citation2022b), we found that professionals—even those with specialist experience in working with this population—appear to highly prioritize all potential treatment targets with this group. This is clearly unattainable and leads to an increased risk of misaligning treatment goals with service users, and subsequently to a higher chance of their disengagement with services (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022; Parr & Pearson, Citation2019). Working with academics and service users to develop training packages for both primary and secondary service professionals is a vital step in providing clinicians with the opportunity to enhance their knowledge and to improve their practice with this underserved service user population. This, of course, should be rooted in a rounded view of minor attraction and the acknowledgement that sexual attractions to children are, theoretically, associated with sexual abuse in many models of sexual offending (for the most recent of these frameworks, see Seto, Citation2019), and is cited as a key risk factor for recidivism among people who have committed sexual offenses in the past (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005). This link should not be discounted in its entirety, though it is questionable as to how prevalent such a link is in samples of non-offending MAPs (as is the current sample). Instead, all work with such non-offending groups in the community should be conducted in responsive and collaborative ways to ensure the effectiveness of treatment, and to maintain engagement from service users.

Limitations and future directions

Survey-based work such as this does not come without limitation. First, we made use of self-report methods that are susceptible to self-presentation biases. This is particularly problematic in this context, where there are high levels of social stigma surrounding minor attraction. In this case, the MAPs in our sample may have over-prioritized mental health and stigma-related treatment targets and downplayed the extent to which they require support with managing their sexual attractions. However, our findings are concordant with prior unpublished informal surveys of the MAP community (e.g., B4U-ACT, Citation2011), theoretical accounts of appropriate MAP treatment approaches (Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022), qualitative analyses of barriers to MAPs seeking help (Dymond & Duff, Citation2020; Goodier & Lievesley, Citation2018; Grady et al., Citation2019; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b), and research into MAP wellbeing (Elchuk et al., Citation2022; Jahnke et al., Citation2015; Lievesley et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, these earlier studies also rely on self-reported responses, and as such future research might wish to focus more on MAPs’ actual interactions with health professionals to determine whether the results presented here concur with requests for support that are made in practice. It is also important to note that such conclusions are only as accurate as the representativeness of the samples from which these data emerge. Most of these prior studies, as well as our own work presented here, use samples recruited from a relatively small number of online forums and peer support groups. As such, the generalizability of these conclusions could be questioned. Future work might look to explore the prevalence of minor attraction among the general population and, where this is found, for probing questions to be asked about: (1) the desire for support, and (2) treatment priorities (where desired).

Our treatment prioritization measure was modeled on the questionnaire used by B4U-ACT (Citation2011) in their earlier survey into MAP wellbeing and treatment desires. This measure was limited in scope, in that a small number of potential treatment targets are listed. However, recently published analyses have found it to be comprised of the treatment target clusters that we discuss in this paper (see Lievesley et al., Citation2022b). Future work may wish to explore MAPs’ treatment targets in more exploratory ways, perhaps with qualitative study designs to enable researchers to probe about the functions of different targets, and the most appropriate ways to engage MAPs in support services.

Conclusions

This work has, for the first time, highlighted an empirical difference in the alignment of treatment targets between MAPs and those who may be in a position to support them in healthcare settings. Specifically, professionals’ lack of knowledge or confidence in treating MAPs leads them to see all potential treatment targets as a priority. Instead, MAPs appear to prioritize mental health concerns and targets related to how they can live within a society that stigmatizes their unchosen sexual attractions. In conducting this work, we have also identified one potential treatment-related construct—self-compassion—which appears to be associated with a greater endorsement of all potential treatment targets by MAPs themselves, with decreased self-compassion being associated with a greater need to address mental health and stigma-related concerns, increased sexual frustration, and a desire to change one’s sexual attraction patterns. Although this is cited as being conceptually important in several places (e.g., Lievesley et al., Citation2018; Lievesley & Harper, Citation2022; Tenbergen, Martinez-Dettamanti, & Christiansen, Citation2021), this is the first time that self-compassion has empirically been found to relate to tangible treatment targets among MAPs. As such, it may be prudent to encourage health professionals to work collaboratively and compassionately with MAPs to identify suitable treatment targets within an acceptance-based framework, which has self-compassion at its core. It is possible that such as approach has the potential to improve life outcomes for MAPs, work on dynamic treatment targets that are amenable to change, and to indirectly reduce known risk factors for sexual offending.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- B4U-ACT. (2011). Mental health care & professional literature. https://www.b4uact.org/research/survey-results/spring-2011-survey/

- Bailey, J. M., Bernhard, P. A., & Hsu, K. J. (2016). An internet study of men sexually attracted to children: Correlates of sexual offending against children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000213

- Baumstarck, K., Alessandrini, M., Hamidou, Z., Auquier, P., Leroy, T., & Boyer, L. (2017). Assessment of coping: A new French four-factor structure of the Brief COPE inventory. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15, e8. 10.1186/s12955-016-0581-9

- Beggs Christofferson, S. M. (2019). Is preventive treatment for individuals with sexual interest in children viable in a discretionary reporting context? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(20), 4254–4280. doi:10.1177/0886260519869236

- Bergen, E., Antfolk, J., Jern, P., Alanko, K., & Santtila, P. (2013). Adults’ sexual interest in children and adolescents online: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 7(2), 94–111.

- Blanchard, R. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 304–316. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9536-0

- Blanchard, R., Lykins, A. D., Wherrett, D., Kuban, M. E., Cantor, J. M., Blak, T., Dickey, R., & Klassen, P. E. (2009). Pedophilia, hebephilia, and the DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(3), 335–350. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9399-9

- Cantor, J. M. (2018). Can pedophiles change? Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(4), 203–206. doi:10.1007/s11930-018-0165-2

- Cantor, J. M., & Fedoroff, J. P. (2018). Can pedophiles change? Response to opening arguments and conclusions. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(4), 213–220. doi:10.1007/s11930-018-0167-0

- Cantor, J. M., & McPhail, I. V. (2015). Sensitivity and specificity of the phallometric test for hebephilia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(9), 1940–1950. doi:10.1111/jsm.12970

- Cantor, J. M., & McPhail, I. V. (2016). Non-offending pedophiles. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8(3), 121–128. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0076-z

- Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, e92. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

- Cohen, L., Ndukwe, N., Yaseen, Z., & Galynker, I. (2018). Comparison of self-identified minor-attracted persons who have and have not successfully refrained from sexual activity with children. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(3), 217–230. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1377129

- Cohen, L. J., Wilman-Depena, S., Barzilay, S., Hawes, M., Yaseen, Z., & Galynker, I. (2020). Correlates of chronic suicidal ideation among community-based minor-attracted persons. Sexual Abuse, 32(3), 273–300. doi:10.1177/1079063219825868

- Dombert, B., Schmidt, A. F., Banse, R., Briken, P., Hoyer, J., Neutze, J., & Osterheider, M. (2016). How common is men’s self-reported sexual interest in prepubescent children? The Journal of Sex Research, 53(2), 214–223. doi:10.1080/00224499.2015.1020108

- Dymond, H., & Duff, S. (2020). Understanding the lived experience of British non-offending paedophiles. Journal of Forensic Practice, 22(2), 71–81. doi:10.1108/JFP-10-2019-0046

- Elchuk, D. L., McPhail, I. V., & Olver, M. E. (2022). Stigma-related stress, complex correlates of disclosure, mental health, and loneliness in minor-attracted people. Stigma and Health, 7(1), 100–112. doi:10.1037/sah0000317

- Elvins, R., & Green, J. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: An empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1167–1187. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002

- Fedoroff, J. P. (2018). Can people with pedophilia change?: Yes they can! Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(4), 207–212. doi:10.1007/s11930-018-0166-1

- Feelgood, S., & Hoyer, J. (2008). Child molester or paedophile? Sociolegal versus psychopathological classification of sexual offenders against children. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 14(1), 33–43. doi:10.1080/13552600802133860

- Göbbels, S., Ward, T., & Willis, G. M. (2012). An integrative theory of desistance from sex offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 453–462. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.003

- Goodier, S., & Lievesley, R. (2018). Understanding the needs of individuals at risk of perpetrating child sexual abuse: A practitioner perspective. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 18(1), 77–98. doi:10.1080/24732850.2018.1432185

- Grady, M. D., Levenson, J. S., Mesias, G., Kavanagh, S., & Charles, J. (2019). “I can’t talk about that”: Stigma and fear as barriers to preventive services for minor-attracted persons. Stigma and Health, 4(4), 400–410. doi:10.1037/sah0000154

- Green, S. B. (1991). How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivariate Behavioral Research, 26(3), 499–510. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7

- Grundmann, D., Krupp, J., Scherner, G., Amelung, T., & Beier, K. M. (2016). Stability of self-reported arousal to sexual fantasies involving children in a clinical sample of pedophiles and hebephiles. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1153–1162. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0729-z

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154–1163. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154

- Hardeberg Bach, M., & Demuth, C. (2018). Therapists’ experiences in their work with sex offenders and people with pedophilia: A literature review. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 14(2), 498–514. doi:10.5964/ejop.v14i2.1493

- Harper, C. A., & Bartels, R. M., & Hogue, T. E. (2018). Reducing stigmatization and punitive attitudes about pedophiles through narrative humanization. Sexual Abuse, 30(5), 533–555. doi:10.1177/1079063216681561

- Harper, C. A., & Hogue, T. E. (2017). Press coverage as a heuristic guide for social decision-making about sexual offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(2), 118–134. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2016.1227816

- Harper, C. A., & Lievesley, R. (2022). Exploring the ownership of child-like sex dolls. Archives of Sexual Behavior. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10508-022-02422-4

- Harper, C. A., Lievesley, R., Blagden, N. J., & Hocken, K. (2022). Humanizing pedophilia as stigma reduction: A large-scale intervention study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(2), 945–960. doi:10.1007/s10508-021-02057-x

- Harper, C. A., Lievesley, R., Blagden, N., Akerman, G., Winder, B., & Baumgartner, E. (2021). Development and validation of the Good Lives Questionnaire. Psychology, Crime & Law, 27(7), 678–703. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2020.1849695

- Harrison, K., Manning, R., & McCartan, K. (2010). Multi-disciplinary definitions and understandings of ‘paedophilia’. Social and Legal Studies, 19(4), 481–496. doi:10.1177/0964663910369054

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masunda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

- Herth, K. (1991). Development and refinement of an instrument to measure hope. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 5(1), 39–51.

- Hocken, K (2018). Safer Living Foundation: The aurora project. In R. Lievesley, K. Hocken, H. Elliott, B. Winder, N. Blagden, & P. Banyard (Eds.), Sexual crime and prevention (pp. 83–109). Cham: Springer Nature.

- Houtepen, J. A. B. M., Sijtsema, J. J., & Bogaerts, S. (2016). Being sexually attracted to minors: Sexual development, coping with forbidden feelings, and relieving sexual arousal in self-identified pedophiles. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42(1), 48–69. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2015.1061077

- Imhoff, R. (2015). Punitive attitudes against pedophiles or persons with sexual interest in children: Does the label matter? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 35–44. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0439-3

- Jahnke, S. (2018). The stigma of pedophilia. European Psychologist, 23(2), 144–153. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000325

- Jahnke, S., & Hoyer, J. (2013). Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: A blind spot in stigma research. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25(3), 169–184. doi:10.1080/19317611.2013.795921

- Jahnke, S., Schmidt, A. F., Geradt, M., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Stigma-related stress and its correlates among men with pedophilic sexual interests. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2173–2187. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0503-7

- Jara, G. A., & Jeglic, E. (2021). Changing public attitudes toward minor attracted persons: An evaluation of an anti-stigma intervention. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 27(3), 299–312. doi:10.1080/13552600.2020.1863486

- King, L. L., & Roberts, J. J. (2017). The complexity of public attitudes toward sex crimes. Victims & Offenders, 12(1), 71–89. doi:10.1080/15564886.2015.1005266

- Lawrence, A. L., & Willis, G. M. (2021). Understanding and challenging stigma associated with sexual interest in children: A systematic review. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(2), 144–162. doi:10.1080/19317611.2020.1865498

- Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2019a). “I could never work with those people…”: Secondary prevention of child sexual abuse via a brief training for therapists about pedophilia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(20), 4281–4302. doi:10.1177/0886260519869238

- Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2019b). Preventing sexual abuse: Perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sexual Abuse, 31(8), 991–1013. doi:10.1177/1079063218797713

- Levenson, J. S., Willis, G. M., & Vicencio, C. P. (2017). Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: Implications for prevention of sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 99–120. doi:10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116

- Lievesley, R., & Harper, C. A. (2022). Applying desistance principles to improve wellbeing and prevent child sexual abuse among minor-attracted persons. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 28(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/13552600.2021.1883754

- Lievesley, R., Elliott, H., & Hocken, K. (2018). Future directions: Moving forward with sexual crime prevention. In R. Lievesley, K. Hocken, H. Elliott, B. Winder, N. Blagden, & P. Banyard (Eds.), Sexual crime and prevention (pp. 181–200). Cham: Springer Nature.

- Lievesley, R., Harper, C. A., & Elliott, H. (2020). The internalization of social stigma among minor-attracted persons: Implications for treatment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1291–1304. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01569-x

- Lievesley, R., Harper, C. A., & Swaby, H. (2022a). Exploring the effect of specialist training on professional practices when working with minor-attracted persons. Journal of Sexual Aggression. [Revised manuscript submitted]

- Lievesley, R., Swaby, H., Harper, C. A., & Woodward, E. (2022b). Primary health professionals’ beliefs, experiences, and willingness to treat minor attracted persons. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(2), 923–943. doi:10.1007/s10508-021-02271-7

- Locati, F., Rossi, G., & Parolin, L. (2019). Interactive dynamics among therapist interventions, therapeutic alliance and metacognition in the early stages of the psychotherapeutic process. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 112–122. doi:10.1080/10503307.2017.1314041

- McPhail, I., Olver, M., Brouillette-Alarie, S., & Looman, J. (2018). Taxometric analysis of the latent structure of pedophilic interest. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 2223–2240. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1225-4

- Neff, K. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. doi:10.1080/15298860309027

- Nienhuis, J. B., Owen, J., Valentine, J. C., Black, S. W., Halford, T. C., Parazak, S. E., Budge, S., & Hilsenroth, M. (2018). Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 593–605. doi:10.1080/10503307.2016.1204023

- Parr, J., & Pearson, D. (2019). Non-offending minor-attracted persons: Professional practitioners’ views on the barriers to seeking and receiving their help. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 28(8), 945–967. doi:10.1080/10538712.2019.1663970

- Piché, L., Mathesius, J., Lussier, P., & Schweighofer, A. (2018). Preventative services for sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse, 30(1), 63–81. doi:10.1177/1079063216630749

- Roche, K., & Stephens, S. (2022). Clinician stigma and willingness to treat those with sexual interest in children. Sexual Offending: Theory, Research, and Prevention, 17, 1–13. doi:10.5964/sotrap.5463

- Rubin, M. (2017). Do p values lose their meaning in exploratory analyses? It depends how you define the familywise error rate. General Review of Psychology, 21(3), 269–275. doi:10.1037/gpr0000123

- Santtila, P., Antfolk, J., Räfså, A., Hartwig, M., Sariola, H., Sandnabba, N. K., & Mokros, A. (2015). Men’s sexual interest in children: One-year incidence and correlates in a population-based sample of Finnish male twins. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(2), 115–134. doi:10.1080/10538712.2015.997410

- Schmidt, A. F., Mokros, A., & Banse, R. (2013). Is pedophilic sexual preference continuous? A taxometric analysis based on direct and indirect measures. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1146–1153. doi:10.1037/a0033326

- Seto, M. C. (2012). Is pedophilia a sexual orientation? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 231–236. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9882-6

- Seto, M. C. (2017). The puzzle of male chronophilias. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(1), 3–22. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0799-y

- Seto, M. C. (2018). Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: Theory, assessment, and intervention (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Seto, M. C. (2019). The motivation-facilitation model of sexual offending. Sexual Abuse, 31(1), 3–24. doi:10.1177/1079063217720919

- Stephens, S., Cantor, J. M., Goodwill, A. M., & Seto, M. C. (2017). Multiple indicators of sexual interest in prepubescent or pubescent children as predictors of sexual recidivism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(6), 585–595. doi:10.1037/ccp0000194

- Stephens, S., McPhail, I., Heasman, A., & Moss, S. (2021). Mandatory reporting and clinician decision-making when a client discloses sexual interest in children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 53(3), 263–273. doi:10.1037/cbs0000247

- Stephens, S., Seto, M. C., Cantor, J. M., & Lalumière, M. L. (2019). The revised screening scale for pedophilic interests (SSPI-2) may be a measure of pedohebephilia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(10), 1655–1663. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.015

- Stevens, E., & Wood, J. (2019). “I despise myself for thinking about them”: A thematic analysis of the mental health implications and employed coping mechanisms of self-reported non-offending minor attracted persons. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 28(8), 968–989. doi:10.1080/10538712.2019.1657539

- Stiels-Glenn, M. (2010). The availability of outpatient psychotherapy for pedophiles in Germany. Recht & Psychiatrie, 28(2), 74–80.

- Swaby, H. & Lievesley, R. (2022). “Falling through the cracks”: A retrospective exploration of the barriers to help-seeking among men convicted of sexual crimes. Sexual Abuse (Forthcoming).

- Tenbergen, G., Martinez-Dettamanti, M., Christiansen, C. (2021). Can nonoffending pedophiles be reached for the primary prevention of child sexual abuse by addressing nonoffending individuals who are attracted to minors in the United States? New strategies with The Global Prevention Project. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 27(4), 265–277. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000561

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, e63. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

- Walker, A. (2021). A long, dark shadow: Minor-attracted people and their pursuit of dignity. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Walker, A., Butters, R. P., & Nichols, E. (2022). “I would report it even if they have not committed anything”: Social service students’ attitudes toward minor-attracted people. Sexual Abuse, 34(1), 52–77. doi:10.1177/1079063221993480

- Ward, T., & Beech, A. (2006). An integrated theory of sexual offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(1), 44–63. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2005.05.002

- Ward, T., & Marshall, W. L. (2004). Good lives, aetiology and the rehabilitation of sex offenders: A bridging theory. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 10(2), 153–169. doi:10.1080/13552600412331290102

- Ward, T., & Siegert, R. J. (2002). Toward a comprehensive theory of child sexual abuse: A theory knitting perspective. Psychology, Crime & Law, 8(4), 319–351. doi:10.1080/10683160208401823

- Ward, T., Mann, R. E., & Gannon, T. A. (2007). The good lives model of offender rehabilitation: Clinical implications. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12(1), 87–107. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.004

- Winder, B, Fedoroff, J. P., Grubin, D., Klapilová, K., Kamenskov, M., Tucker, D., Basinskaya, I. A., & Vvedensky, G. E. (2019). The pharmacologic treatment of problematic sexual interests, paraphilic disorders, and sexual preoccupation in adult men who have committed a sexual offence. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(2), 159–168. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1577223