Abstract

Sexting (exchanging sexual correspondence in the online space) is considered a practice that expresses sexuality in the online space. Between adolescents, sexting can be part of a couple relationship or outside of it, and can be voluntary or coercive. Regardless of motives, sexting has been linked to various negative outcomes. Understanding the factors that influence sexting behavior is essential for developing effective prevention and intervention programs. The present study aimed to identify and compare different profiles of sexting behavior in adolescents using latent class analysis. Participants were 487 Israeli adolescents aged 14-19 (male N = 215, 44%, female N = 272, 56%) years who completed an online survey of demographic factors, online parental mediation, family and friend cohesion, and perception of sexting norms. Two distinct classes of individuals were identified: those who engage in sexting (“sexters”) and those who do not (“non-sexters”). Sexters were more likely to be secular, and without a romantic partner. These findings may inform interventions aimed at preventing negative outcomes associated with adolescent sexting.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of cognitive and physiological changes as well as sexual development, which shape the social and romantic relationships of young people (Molla-Esparza, Nájera, López-González, & Losilla, Citation2023). Because technological media have become an integral part of our lives, expressions of sexuality that characterize adolescence are also manifested in the online space, among others, as sexting behaviors (Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, Citation2020; Lunde & Joleby, Citation2023). Sexting is defined as sending, receiving, and forwarding correspondence of a direct or implied sexual nature using text, images, or video (Dir, Coskunpinar, Steiner, & Cyders, Citation2013; Madigan, Ly, Rash, Van Ouytsel, & Temple, Citation2018). The research literature divides sexting behaviors into active and passive. Active sexting refers to sending and forwarding sexting messages, that is, the creation of the content and its distribution; passive sexting refers to receiving such messages or requesting that sexual content be created and sent to another (Molla-Esparza et al., Citation2023). Studies indicate a high prevalence of sexting by adolescents. For example, a meta-analysis shows that 1 out of 5 adolescents sent a sexting message (Mori, Park, Temple, & Madigan, Citation2022). A study conducted in Israel found that about 30% of youths in grades 7-12 sent a sexting message (Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, Citation2020). Involvement in sexting appears to increase with age from adolescence into emerging adulthood (Choi, Mori, Van Ouytsel, Madigan, & Temple, Citation2019; Klettke, Hallford, & Mellor, Citation2014).

The research literature is not consistent regarding sex and sexting. Some studies found that boys tend to send more sexting messages than girls (Foody, Kuldas, Sargioti, Mazzone, & O’Higgins Norman, Citation2023; Gregg, Somers, Pernice, Hillman, & Kernsmith, Citation2018; Klettke, Hallford, Clancy, Mellor, & Toumbourou, Citation2019) but other studies reported the opposite (Klettke et al., Citation2014; Yépez-Tito, Ferragut, & Blanca, Citation2019) and others yet found no difference between the sexes (De Graaf, Verbeek, Van den Borne, & Meijer, Citation2018; Madigan et al., Citation2018).

One of the variables that appears to influence those who use sexting as a practice of online sexuality is degree of religiosity, with religious adolescents being less likely to send sexting messages than secular ones (Strassberg, Cann, & Velarde, Citation2017). Another study found that sexting mediated the relationship between religiosity and sexual activity in female college students (Hall, Williams, Ford, Cromeans, & Bergman, Citation2020).

The debate surrounding sexting by adolescents concerns its legitimacy as a normative behavior in the digital age vs. its association with risky behaviors (Ojeda & Del Rey, Citation2022). The research literature paints a mixed picture. Some studies present sexting as a legitimate expression of sexuality in the online space (Lee & Crofts, Citation2015; Lippman & Campbell, Citation2014), while others point to a connection between sexting and risky behaviors (Benotsch, Snipes, Martin, & Bull, Citation2013; Brinkley, Ackerman, Ehrenreich, & Underwood, Citation2017; Maas, Bray, & Noll, Citation2019). Because the issue is complex and some regard voluntary and uncoerced sexting to be a modern phenomenon addressing it by legislation is a challenge, and many young people experience it as legitimate and enabling (Phippen & Bond, Citation2023).

Sexting between adolescents, as part of a romantic relationship, is considered less stigmatizing from a social point of view and less risky than sexting outside a romantic relationship (Huntington & Rhoades, Citation2021). This may be the reason why we find that sexting is carried out more within relationships than outside of them (Delevi & Weisskirch, Citation2013). The motive for sending sexting messages also affects the degree of risk involved in sexting (Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023); thus, voluntary and consensual sexting, part of a flirtation acceptable to both parties, is different from coercive sexting (Bragard & Fisher, Citation2022; Cooper, Quayle, Jonsson, & Svedin, Citation2016; Englander, Citation2019).

Irrespective of its motives, sexting can also have dangerous consequences because it is carried out on the Internet, where it can be easily distributed, leading to harms such as bullying, sexual extortion, and non-consensual dissemination of intimate images (Bragard & Fisher, Citation2022; Dolev-Cohen, Nezer, & Zumt, Citation2022; Henry & Flynn, Citation2019; McGlynn, Rackley, & Houghton, Citation2017; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2020). Together with individual predictors such as age, sex, and degree of religiosity that have been examined in the research literature (Baumgartner, Sumter, Peter, Valkenburg, & Livingstone, Citation2014; Reed, Boyer, Meskunas, Tolman, & Ward, Citation2020; Walrave, Heirman, & Hallam, Citation2014), an attempt has been made to identify environmental predictors for sexting such as friendship quality and norms of the peer group (Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023; Foody et al., Citation2023; Maheux et al., Citation2020).

The psychological theory of planned behavior serves as a framework for predicting human behavior based on components: the attitudes of the individual, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, Citation1991). The theory can serve as a suitable infrastructure for predicting the use of sexting practices (Dodaj et al., 2023). Indeed, it was found that adolescents who reported a more favorable attitude toward sexting were more likely to engage in it (Cuccì, Olivari, Colombo, & Confalonieri, Citation2024). Studies also found subjective norms to be a strong predictor of intention to engage in sexting (Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023; Walrave et al., Citation2015), with adolescents who believed that the popular members in their peer group were sexting being ten times more likely to do it themselves (Maheux et al., Citation2020). Studies also found that a greater need for popularity could lead adolescents to sexting behaviors (vanden Abeele, Campbell, Eggermont, & Roe, Citation2014). This aligns with the social norm framework, as presented by Cialdini and Trost (Citation1998), which posits that individuals’ behaviors are swayed by their perceptions of prevailing social norms. It indicates that individuals tend to adhere to behaviors they view as customary or socially acceptable within a particular social setting. This observation underscores the pivotal role of peer relationships in molding the conduct of adolescents, as well as the importance of factoring in peer dynamics when formulating prevention and intervention approaches.

Together with the peer group, parents, who are important socialization agents for their children (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979), also played an important role in mediating sexting and preventing its risks (Cuccì et al., Citation2024; Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, Citation2022a). Although it is possible that as adolescents grow and develop their individual identities, parental influence on their sexting behaviors appears to diminish (Barrense-Dias et al., Citation2022). A study conducted on adolescents in Croatia found that parental monitoring reduced the use of sexting in adolescents aged 16 (Tomić, Burić, & Štulhofer, Citation2018). Yet another study, conducted in Ecuador, found that parental monitoring did not contribute to a decrease in the use of sexting in adolescents aged 12-18. Other studies investigated in-depth parental mediation and found that restrictive parenting showed a negative correlation with the sending and receiving of sexts and active mediation showed a negative correlation with only sending sexts (Corcoran, Doty, Wisniewski, & Gabrielli, Citation2022). Thus, research in the field appears insufficient, and the findings are inconclusive. In any case, family support was found to be associated with a lower likelihood of sexting behaviors (Baumgartner, Sumter, Peter, & Valkenburg, Citation2012; Burén & Lunde, Citation2018; Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023).

The current study

The present study aimed to identify and examine distinct profiles of adolescents’ sexting behaviors, using latent class analysis (LCA). The research literature refers to different types of motives for sexting (for example, Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023; Van Ouysel et al., Citation2017) and different sexting behaviors, such as sending and receiving (for example, Lippman & Campbell, Citation2014), consensual and non-consensual (for example, Barroso, Marinho, Figueiredo, Ramião, & Silva, Citation2023, Lebedíková, Olveira-Araujo, Mýlek, Smahel, & Dedkova, Citation2024) that are often reported in the research literature as one type of sexting involvement (for example, Del Rey, Ojeda, Casas, Mora-Merchán, & Elipe, Citation2019; Drouin, Coupe, & Temple, Citation2017; Hollá, Citation2020). The uniqueness of the present study lies in that it focuses not on the personality characteristics of the participants but mainly on family and social norms. Identification of the profiles allows adapting educational and preventive interventions for adolescents.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A group of 487 adolescents between the ages of 14-19 from all regions of Israel completed a set of 7 online questionnaires in Hebrew during 2021-2022. Recruitment was done through an online ad on Instagram and WhatsApp groups (N = 152), and to increase the number of participants, an internal panel was also used (N = 335). Prior to completing the questionnaire, all participants were required to provide parental consent ().

Table 1. Background characteristics of the participants (N = 487)

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

The demographics questionnaire in the current study included pertinent factors, such as age, sex (male, female, other, although in practice participants identified only as male and female), relationship status, and level of religiosity (non-religious, traditional, and religious), as self-defined by the youths (as used by Zilberman, Yadid, Efrati, Neumark, & Rassovsky, Citation2018).

Sexting behaviors

The questionnaire was created for the present study. It examined the sending, receiving, and forwarding habits of individuals engaging in sexting text and visual messages. It comprised 16 items, 13 of which were derived from Dolev-Cohen and Ricon (Citation2020) questionnaire, and the remaining three items focused on the number of sexting partners and sexting under pressure, sourced from Morelli et al. (2016).

Online parental mediation (Sasson & Mesch, Citation2014), based on: EU

The questionnaire assessed four types of online parental mediation: six items concerning parental involvement in the children’s activities on the Internet or the lack thereof (for example: “Do your parents allow you to use instant messaging software whenever you want, without permission or supervision?”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.76; six items addressing facilitating mediation (for example: “Did one or both of your parents help you when you had trouble doing or finding something on the Internet?”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.76; three items assessing restrictive mediation by humans (for example: “When you use the Internet, do one or both of your parents sometimes check your profile on a social network or online community?”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.84; and three items assessing restrictive mediation by technological means (for example: “To the best of your knowledge, did one or both of your parents perform one of the following actions on the computer or smartphone you are generally using: parental control or other means of blocking or filtering certain types of sites, that is, something that prevents you from visiting certain sites or stop various types of activities on the Internet?”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.67.

Family cohesion (Sason & Mesch, Citation2014)

The family cohesion questionnaire assessed the degree to which participants’ relationship with their parents, as they see it, is attentive, loving, close, supportive, and cohesive. Respondents ranked family cohesion on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Agree to a large extent. Internal consistency was α = 0.92.

Cohesion with friends (Sason & Mesch, Citation2014)

The cohesion with friends questionnaire assesses the degree to which participants’ relationships with their friends, as they perceive these relationships, are attentive, loving, close, supportive, and cohesive. Respondents ranked cohesion with friends on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Agree to a large extent. Internal consistency was α = 0.93.

Perception of friends’ vs. parents’ sexting norms

This questionnaire was created for the present research based on a subjective norm questionnaire concerning the sending of naked images (Liong & Cheng, 2017). It is intended to assess the degree to which participants believe that sending, receiving, or distributing sexting is acceptable to their friends and parents. The questionnaire consists of six items, three assessing friends’ perceptions (questions about the perception of friends’ norms: “I think that most of my friends send/receive/forward provocative or sexual messages to others”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.80, and three assessing parents’ perceptions (questions about the parents’ perception of norms: “I think it would upset my parents if I were to send/receive/transmit provocative or sexual messages to others”), showing an internal consistency of α = 0.88). Respondents ranked their answers on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Strongly agree.

Analyses

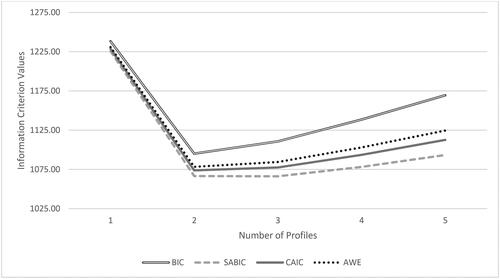

Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to estimate distinct profiles in text sexting (yes, no), image sexting (yes, no), forwarding sexting (yes, no), and coerced sexting (yes, no). To do so, the guidelines of Nylund-Gibson and Choi (Citation2018) were used, and the LPA was estimated in MPlus 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017) structural equation modeling (SEM) software. The LPA was estimated in three steps. In Step 1, one to five possible profiles were examined using unconditional LPA. To decide on the number of profiles, the following information was used, which is summarized in : (a) information criteria (IC), including the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC), consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC), and approximate weight of evidence criterion (AWE), which are approximate fit indices, with lower values indicating superior fit. The ICs were also plotted () to inspect for an “elbow” of point of “diminishing returns” in model fit; (b) likelihood-based tests—the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT) and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT)—which provide p-values assessing whether adding a class leads to a statistically significant improvement in model fit. The BLRT is one of the most robust methods across various modeling conditions (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, Citation2007); and (c) Bayes factor (BF) indices, as a pairwise comparison of fit between two neighboring class models with values > 10 suggesting “strong” support for the more complex model, and the correct model probability (cmP) that provides an estimate of each model being “correct” out of all the models considered. The overlap between different profiles was also considered as well as the relative sizes of the emergent profiles. A minimum class size of 5% of the sample was chosen based on prior recommendations (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018). Overall, 486 participants were profiled in this phase. Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood (FIML).

Figure 1. Plot of information criterion values: sexting behavior – latent class analysis models.

Table 2. Fit statistics and classification coefficients: sexting behavior

Upon deciding on the ideal number of profiles, the antecedents and consequences of latent class membership were examined using auxiliary variables: covariates and distal outcomes. To do so, Bolck, Croons, and Hagenaars’s (BCH) method (Bakk & Kuha, Citation2021; Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars, Citation2004; Vermunt, Citation2010) was employed. The profile enumeration step was separated from subsequent structural analyses, so that profiles were enumerated only with the chosen latent class indicators measuring the substantive domain of interest—text, image, forwarding, and coerced sexting. In other words, using the selected profile solution from Step 1, BCH weights were saved alongside covariates (age, sex, religiosity, having a romantic partner), and distal outcomes (sexting norms of friends and family, family and peer cohesion, and parental mediation strategies) in Step 2 of the LCA. Then, in the third and final step of the LCA, the measurement parameters of the latent classes were fixed, accounting for classification error, auxiliary variables were included, and their relation to the latent class variable was estimated. By doing so, Step 3 allows the examination of differences between profiles in the covariates and distal outcomes. The differences in the distal outcomes are examined while controlling for the possible contribution of the covariates to the effects.

Results

Latent class analysis

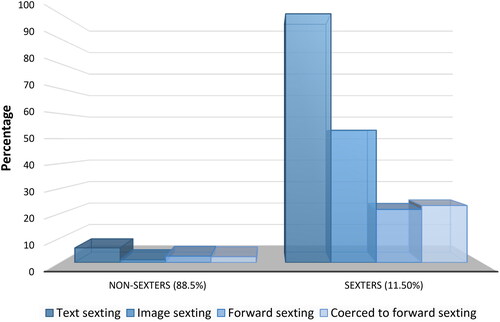

Results are summarized in . Fit indices did not converge on a single solution, which is generally the rule rather than the exception in applied practice (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018). The ICs, BF, and cmP suggested a 2-class solution, whereas the likelihood tests supported a 3-class solution. In addition, as plotted in , an elbow in the ICs was observed already at the 2-class solution. The 3-class solution comprised one group of exceptionally small size (2%; n = 11). Given that simulation studies showed in a variety of different types of mixture models that small classes are generally challenging to recover (e.g. Morgan, Citation2015), and that most of the fit indices agreed on a 2-class solution (Nylund et al., Citation2007), I selected the 2-class solution in Step 1. Classification probabilities are presented in . The entropy score of 0.89 and the average posterior probabilities (AvePP) scores > 0.95 reflect exceptionally well-separated profiles (Nagin & Nagin, Citation2005). The classes are presented in and comprise non-sexters (n = 430) and sexters (n = 56).

Figure 2. Scores plot: sexting behavior—2-class model. Note. class prevalence is in parentheses.

Table 3. Classification probabilities: sexting behavior – 2-class solution

Differences between classes in the study covariates

In the third step of the model, significant differences between the classes were found in the covariates of religiosity and having a romantic partner. Specifically, sexters were significantly more likely to be more secular in their religious views (odds ratio [OR] = 0.49, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.28, 0.84 than non-sexters; p = .01), and without a romantic partner (OR = 0.17, 95% CI 0.09, 0.35; p < .0001). No differences were found in age (p = .183) or sex (p = .067).

Differences between classes in distal outcomes

In the third step of the model, significant differences between the classes were found in family and peer cohesion and sexting norms of friends after controlling for the contribution of age, sex, religiosity, and having a partner. Intercepts and residual standard errors are presented in . Specifically, the model revealed that sexters were lower in family, t = 3.14, p = .002, and peer cohesion, t = 2.11, p = .035 than were non-sexters. Sexters were also higher on sexting norms of friends than were non-sexters, t = −5.32, p < .0001. Other differences were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Intercepts and residuals standard errors of distal outcomes as a function of class

Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that based on their sexting behavior, adolescents can be grouped into non-sexters and sexters, the latter being characterized by lower levels of family and peer cohesion and higher levels of sexting norms of friends than non-sexters. Furthermore, sexters were more likely to be secular as far as degree of religiosity was concerned, and not to have a romantic partner.

Although boys tend to sext more than girls in traditional societies (Baumgartner et al., Citation2014; Ybarra & Mitchell, Citation2014), and Israeli society is considered traditional (Lavee & Katz, Citation2003), no significant difference was found between boys and girls in sexting behavior. This may be attributed to the different motives driving girls and boys to sext. Boys are perceived as less likely to be harmed by sexting (Setty, Citation2020), whereas girls feel pressure from boys to sext (Lippman & Campbell, Citation2014). Additionally, it is important for adolescent girls to be perceived as attractive in their sexual representation on the Internet (van Oosten & Vandenbosch, 2017). Therefore, even though there is no difference in the prevalence of sexting between boys and girls, their underlying motives may differ. Furthermore, sexters were found to have higher levels of sexting norms of friends, suggesting that social norms in the age of social networks have evolved to allow women to express their sexuality more freely (Suler, 2004). Adolescents use sexting to explore their sexuality (Cooper et al., Citation2016; Mori et al., Citation2019), and this exploration is seen as legitimate for both genders. Indeed, many studies find no difference in sexting behavior between boys and girls (Madigan et al., Citation2018).

Another characteristic of the group of sexters according to the findings of the present study was that they were less likely to have a romantic partner. The fact that sexting is often used as flirting (Soriano-Ayala, C. Cala, & Dalouh, Citation2020), that is, as part of courtship, before establishing a relationship (Lenhart, Citation2009) may explain this finding. It is possible that after establishing the relationship, the couple can legitimately express sexuality through physical contact and resort less to sexting.

In the present study, sexters were found to be more secular in their religious views, which reinforces findings from other studies (Bianchi et al., Citation2021; Strassberg et al., Citation2017). The opposition of religion to sexual behavior outside the institutional relationship of marriage may account for the fact that sexual behavior in the online space, such as sexting, is also considered unacceptable behavior (Bianchi et al., Citation2021). Evidence of this can also be found in a study that examined communication between parents and children about sexting, which reported that more positive attitudes about sexuality and sex education led to a more effective discussion about sexting with adolescents, compared to more conservative perceptions regarding sexuality, which led to a discussion of lower quality about sexting (Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, Citation2021).

The present study found that sexters were found to have lower levels of family and peer cohesion and higher levels of sexting norms of friends than non-sexters. During adolescence, the importance of the peer group increases alongside that of the family. Studies have found that friends are an important source of information about sexuality in general and sexting in particular, especially given that they are the main source of discourse about sexuality in the online space (Widman et al., Citation2021). Parents also play an important role in mediating sexting and preventing its risks (Corcoran et al., Citation2022; Dolev-Cohen & Ricon, Citation2022b; Vanwesenbeeck, Ponnet, Walrave, & Van Ouytsel, Citation2018), therefore the absence of family cohesion may result in less guidance to adolescents than in more cohesive families. Adolescents who experience less cohesion within their circle of friends may seek alternative means of connection. Sexting could be a way for them to establish intimate connections with others, compensating for perceived deficiencies in their offline relationships. Given that the sexters in the present study sent, received, and forwarded sexting messages, it may be that their motives were not only sexual, which is perceived by adolescents as normative (York & Purdy, 2021), but also instrumental, which is a deviation from the social norm and appears to lead to risk behaviors (Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023). Therefore, it appears that high levels of family and peer cohesion can create an atmosphere that prevents and reduces sexting.

Nevertheless, in adolescence, social status is highly important and social norms may control the behavior of adolescents. The present study found that the profile of sexting adolescents tended to be influenced by social norms. This finding reinforces those of previous studies reporting that adolescents tended to believe that popular students in their class sent sexting messages, which led them to send such messages as well (Maheux et al., Citation2020). This finding aligns with the social norms approach proposed by Cialdini and Trost (Citation1998), which posits that individual behavior is influenced by perceived social norms. It indicates that individuals tend to conform to what they perceive as typical or socially accepted behavior within their social environment. This result highlights the crucial role of peer relationships in shaping adolescent behavior and emphasizes the importance of accounting for peer dynamics when devising prevention and intervention strategies.

Although it appears to be possible to identify additional subgroups based on sexting behavior (such as separate profiles for those who initiate and those who forward sexting), the present study identified only two profiles. This finding may be explained based on the premise that the adoption of conservative family and social norms and of strict boundaries may prevent various sexting behaviors, such as sending and forwarding messages (Burén, Holmqvist Gattario, & Lunde, Citation2022; Dolev-Cohen, Citation2023). In addition, the absence of discourse and mediation may cause adolescents who engage in sexting to regard sending and forwarding messages to be part of a collection of acceptable online sexual behaviors (Lippman & Campbell, Citation2014; Van Ouytsel, Van Gool, Walrave, Ponnet, & Peeters, Citation2017).

This study has potential significance for counselors and other professionals who work with adolescents. The findings point to the characteristics of sexters in Israel, a Western but conservative country. It appears that in Israel there is a need to initiate a dialogue with teenagers about different types of sexting behavior and to create ethical and respectful social norms through education. It is also necessary to convey educational messages to boys as well as girls, beyond those of deterrence and victim blaming. The research findings also shed light on the role of family and social cohesion and inform us about the relationship between these variables and showing potentially risky sexting behaviors.

Limitations of the study

The following limitations should be considered. First, the study was based on self-report questionnaires, and it is possible that the questions, which in part concerned sexting behaviors, led to inaccurate reporting. At the same time, given that the questionnaires were anonymous and completed online, participants were given the opportunity to present themselves authentically. Because the subject of the questionnaires was a sensitive one, those who completed it were likely young people who found it easier to relate to sexuality than did the more religious and conservative youths. Furthermore, respondents were all Hebrew speakers, and as such, did not represent the different populations speaking other languages in Israel. Follow-up studies should address these points. Finally, a larger number of sexting participants could have allowed the testing of additional profiles as well as the accuracy of the two profiles identified in this study.

Disclosure statement

The author has no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest. The study complied with ethical standards. No funding was provided for the study. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Bakk, Z., & Kuha, J. (2021). Relating latent class membership to external variables: An overview. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 74(2), 340–362. doi:10.1111/bmsp.12227

- Barrense-Dias, Y., Chok, L., Stadelmann, S., Berchtold, A., & Suris, J. C. (2022). Sending one’s own intimate image: Sexting among middle-school teens. Journal of School Health, 92(4), 353–360. doi:10.1111/josh.13137

- Barroso, R., Marinho, A. R., Figueiredo, P., Ramião, E., & Silva, A. S. (2023). Consensual and non-consensual sexting behaviors in adolescence: A systematic review. Adolescent research review, 8(1), 1–20. doi:10.1007/s40894-022-00199-0

- Baumgartner, S. E., Sumter, S. R., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2012). Identifying teens at risk: Developmental pathways of online and offline sexual risk behavior. Pediatrics, 130(6), e1489–e1496. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0842

- Baumgartner, S. E., Sumter, S. R., Peter, J., Valkenburg, P. M., & Livingstone, S. (2014). Does country context matter? Investigating the predictors of teen sexting across Europe. Computers in Human Behavior, 34, 157–164. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.041

- Benotsch, E. G., Snipes, D. J., Martin, A. M., & Bull, S. S. (2013). Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(3), 307–313. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.011

- Bianchi, D., Baiocco, R., Lonigro, A., Pompili, S., Zammuto, M., Di Tata, D., Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Di Norcia, A., Cannoni, E., Longobardi, E., & Laghi, F. (2023). Love in quarantine: Sexting, stress, and coping during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 20, 465–478. doi:10.1007/s13178-021-00645-z

- Bolck, A., Croon, M., & Hagenaars, J. (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political analysis, 12(1), 3–27. doi:10.1093/pan/mph001

- Bragard, E., & Fisher, C. B. (2022). Associations between sexting motivations and consequences among adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 94(1), 5–18. doi:10.1002/jad.12000

- Brinkley, D. Y., Ackerman, R. A., Ehrenreich, S. E., & Underwood, M. K. (2017). Sending and receiving text messages with sexual content: Relations with early sexual activity and borderline personality features in late adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 119–130. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.082

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. USA: Harvard University Press.

- Burén, J., Holmqvist Gattario, K., & Lunde, C. (2022). What do peers think about sexting? Adolescents’ views of the norms guiding sexting behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(2), 221–249. doi:10.1177/07435584211014837

- Burén, J., & Lunde, C. (2018). Sexting among adolescents: A nuanced and gendered online challenge for young people. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 210–217. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.003

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Choi, H. J., Mori, C., Van Ouytsel, J., Madigan, S., & Temple, J. R. (2019). Adolescent sexting involvement over 4 years and associations with sexual activity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(6), 738–744. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.026

- Cooper, K., Quayle, E., Jonsson, L., & Svedin, C. G. (2016). Adolescents and self-taken sexual images: A review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 706–716. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.003

- Corcoran, E., Doty, J., Wisniewski, P., & Gabrielli, J. (2022). Youth sexting and associations with parental media mediation. Computers in Human Behavior, 132, 107263. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107263

- Cuccì, G., Olivari, M. G., Colombo, C. C., & Confalonieri, E. (2024). Risk or fun? Adolescent attitude towards sexting and parental practices. Journal of Family Studies, 30(1), 22–43. doi:10.1080/13229400.2023.2189151

- De Graaf, H., Verbeek, M., Van den Borne, M., & Meijer, S. (2018). Offline and online sexual risk behavior among youth in the Netherlands: Findings from “sex under the age of 25.” Frontiers in Public Health, 6. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00072

- Delevi, R., & Weisskirch, R. S. (2013). Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2589–2594. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.003

- Del Rey, R., Ojeda, M., Casas, J. A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Elipe, P. (2019). Sexting among adolescents: The emotional impact and influence of the need for popularity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1828. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01828

- Dir, A. L., Coskunpinar, A., Steiner, J. L., & Cyders, M. A. (2013). Understanding differences in sexting behaviors across gender, relationship status, and sexual identity, and the role of expectancies in sexting. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(8), 568–574. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0545

- Dodaj, A., Sesar, K., Pérez, M. O., Del Rey, R., Howard, D., & Gerding Speno, A. (2023). Using vignettes in qualitative research to assess young adults’ perspectives of sexting behaviours. Human Technology, 19(1), 103–120. doi:10.14254/1795-6889.2023.19-1.7

- Dolev-Cohen, M. (2023). The association between sexting motives and behavior as a function of parental and peers’ role. Computers in Human Behavior, 147, 107861. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.107861

- Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2020). Demystifying sexting: Adolescent sexting and its associations with parenting styles and sense of parental social control in Israel. Cyberpsychology, 14(1), Article 6. doi:10.5817/CP2020-1-6

- Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2022). Talking about sexting: Association between parental factors and quality of communication about sexting with adolescent children in Jewish and Arab Society in Israel. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 48(5), 429–443. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2021.2002489

- Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2022a). Dysfunctional parent-child communication about sexting during adolescence. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 1689–1702. doi:10.1007/s10508-022-02286-8

- Dolev-Cohen, M., & Ricon, T. (2022b). The associations between parents’ technoference, their problematic use of digital technology, and the psychological state of their children. Psychology of Popular Media, 13(2), 171–179. doi:10.1037/ppm0000444

- Dolev-Cohen, M., Nezer, I., & Zumt, A. A. (2022). A qualitative examination of school counselors’ experiences of sextortion cases of female students in Israel. Sexual Abuse, 35(8), 903–926. doi:10.1177/10790632221145925

- Drouin, M., Coupe, M., & Temple, J. R. (2017). Is sexting good for your relationship? It depends Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 749–756. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.018

- Englander, E. (2019). What Do We Know About Sexting, and When Did We Know It? Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(5), 577–578. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.004

- Foody, M., Kuldas, S., Sargioti, A., Mazzone, A., & O’Higgins Norman, J. (2023). Sexting behaviour among adolescents: Do friendship quality and social competence matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 142, 107651. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.107651

- Gregg, D., Somers, C. L., Pernice, F. M., Hillman, S. B., & Kernsmith, P. (2018). Sexting Rates and Predictors From an Urban Midwest High School. Journal of School Health, 88(6), 423–433. doi:10.1111/josh.12628

- Hall, M., Williams, R. D., Ford, M. A., Cromeans, E. M., & Bergman, R. J. (2020). Hooking-up, religiosity, and sexting among college students. Journal of Religion and Health, 59(1), 484–496. doi:10.1007/s10943-016-0291-y

- Henry, N., & Flynn, A. (2019). Image-based sexual abuse: Online distribution channels and illicit communities of support. Violence Against Women, 25(16), 1932–1955. doi:10.1177/1077801219863881

- Hollá, K. (2020). Sexting types and motives detected among Slovak adolescents. European Journal of Mental Health, 15(2), 75–92. doi:10.5708/EJMH.15.2020.2.1

- Huntington, C., & Rhoades, G. (2021). Associations of sexting with dating partners with adolescents’ romantic relationship behaviors and attitudes. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 38(4), 780–795. doi:10.1080/14681994.2021.1931096

- Klettke, B., Hallford, D. J., & Mellor, D. J. (2014). Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(1), 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.007

- Klettke, B., Hallford, D. J., Clancy, E., Mellor, D. J., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2019). Sexting and psychological distress: The role of unwanted and coerced sexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(4), 237–242. doi:10.1089/cyber.2018.0291

- Lavee, Y., & Katz, R. (2003). The family in Israel. Marriage & Family Review, 35(1–2), 193–217. doi:10.1300/J002v35n01_11

- Lebedíková, M., Olveira-Araujo, R., Mýlek, V., Smahel, D., & Dedkova, L. (2024). The reciprocal relationship between consensual sexting and peer support among adolescents: A three-wave longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 152, 108048. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.108048

- Lee, M., & Crofts, T. (2015). Gender, pressure, coercion and pleasure: Untangling motivations for sexting between young people. British Journal of Criminology, 55(3), 454–473. doi:10.1093/bjc/azu075

- Lenhart, A. (2009). Teens and sexting. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Teens_and_Sexting.pdf

- Lippman, J. R., & Campbell, S. W. (2014). Damned if you do, damned if you don’t…if you’re a girl: Relational and normative contexts of adolescent sexting in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 371–386. doi:10.1080/17482798.2014.923009

- Liong, M., & Cheng, G. H. L. (2017). Sext and gender: Examining gender effects on sexting based on the theory of planned behaviour. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(7), 726–736. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2016.1276965

- Lunde, C., & Joleby, M. (2023). Being under pressure to sext: Adolescents’ experiences, reactions, and counter-strategies. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(1), 188–201. doi:10.1111/jora.12797

- Maas, M. K., Bray, B. C., & Noll, J. G. (2019). Online sexual experiences predict subsequent sexual health and victimization outcomes among female adolescents: A latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(5), 837–849. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-00995-3

- Madigan, S., Ly, A., Rash, C. L., Van Ouytsel, J., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(4), 327. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5314

- Maheux, A. J., Evans, R., Widman, L., Nesi, J., Prinstein, M. J., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2020). Popular peer norms and adolescent sexting behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 78(1), 62–66. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.002

- Masyn, K. E. (2017). Measurement invariance and differential item functioning in latent class analysis with stepwise multiple indicator multiple cause modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 24(2), 180–197.

- McGlynn, C., Rackley, E., & Houghton, R. (2017). Beyond ‘revenge porn’: The continuum of image-based sexual abuse. Feminist Legal Studies, 25(1), 25–46. doi:10.1007/s10691-017-9343-2

- Molla-Esparza, C., Nájera, P., López-González, E., & Losilla, J.-M. (2023). Sexting behavior predictors vary with addressee and the explicitness of the sexts. Youth & Society, 55(4), 749–771. doi:10.1177/0044118X231158138

- Morelli, M., Bianchi, D., Baiocco, R., Pezzuti, L., & Chirumbolo, A. (2016). Sexting, psychological distress and dating violence among adolescents and young adults. Psicothema, 28(2), 137–142. doi:10.7334/psicothema2015.193

- Morgan, G. B. (2015). Mixed mode latent class analysis: An examination of fit index performance for classification. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(1), 76–86. doi:10.1080/10705511.2014.935751

- Mori, C., Temple, J. R., Browne, D., & Madigan, S. (2019). Association of sexting with sexual behaviors and mental health among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(8), 770–779. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1658

- Mori, C., Park, J., Temple, J. R., & Madigan, S. (2022). Are youth sexting rates still on the rise? A meta-analytic update. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(4), 531–539. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.026

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nagin, D. S., & Nagin, D. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. London, England: Harvard University Press.

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. doi:10.1080/10705510701575396

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440. doi:10.1037/tps0000176

- Ojeda, M., & Del Rey, R. (2022). Lines of action for sexting prevention and intervention: A systematic review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1659–1687. doi:10.1007/s10508-021-02089-3

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2020). Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a National Survey of U.S. youth. Sexual Abuse, 32(1), 30–54. doi:10.1177/1079063218800469

- Phippen, A., & Bond, E. (2023). Policing teen sexting: Supporting children’s rights while applying the law. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Reed, L. A., Boyer, M. P., Meskunas, H., Tolman, R. M., & Ward, L. M. (2020). How do adolescents experience sexting in dating relationships? Motivations to sext and responses to sexting requests from dating partners. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104696. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104696

- Sasson, H., & Mesch, G. (2014). Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 32–38. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.025

- Setty, E. (2020). ‘Confident’ and ‘hot’ or ‘desperate’ and ‘cowardly’? Meanings of young men’s sexting practices in youth sexting culture. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(5), 561–577. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1635681

- Soriano-Ayala, E., C. Cala, V., & Dalouh, R. (2020). Adolescent profiles according to their beliefs and affinity to sexting. A cluster study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1087. doi:10.3390/ijerph17031087

- Strassberg, D. S., Cann, D., & Velarde, V. (2017). Sexting by high school students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1667–1672. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0926-9

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. doi:10.1089/1094931041291295

- Tomić, I., Burić, J., & Štulhofer, A. (2018). Associations between croatian adolescents’ use of sexually explicit material and sexual behavior: Does parental monitoring play a role? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1881–1893. doi:10.1007/s10508-017-1097-z

- vanden Abeele, M., Campbell, S. W., Eggermont, S., & Roe, K. (2014). Sexting, mobile porn use, and peer group dynamics: boys’ and girls’ self-perceived popularity, need for popularity, and perceived peer pressure. Media Psychology, 17(1), 6–33. doi:10.1080/15213269.2013.801725

- Vanwesenbeeck, I., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Van Ouytsel, J. (2018). Parents’ Role in Adolescents’ Sexting Behaviour. In Sexting (pp. 63–80). Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71882-8_5

- Van Oosten, J. M., & Vandenbosch, L. (2017). Sexy online self-presentation on social network sites and the willingness to engage in sexting: A comparison of gender and age. Journal of Adolescence, 54, 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.11.006

- Van Ouytsel, J., Van Gool, E., Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., & Peeters, E. (2017). Sexting: Adolescents’ perceptions of the applications used for, motives for, and consequences of sexting. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(4), 446–470. doi:10.1080/13676261.2016.1241865

- Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political analysis, 18(4), 450–469. doi:10.1093/pan/mpq025

- Walrave, M., Heirman, W., & Hallam, L. (2014). Under pressure to sext? Applying the theory of planned behaviour to adolescent sexting. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(1), 86–98. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2013.837099

- Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., van Ouytsel, J., van Gool, E., Heirman, W., & Verbeek, A. (2015). Whether or not to engage in sexting: Explaining adolescent sexting behaviour by applying the prototype willingness model. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 796–808. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.008

- Widman, L., Javidi, H., Maheux, A. J., Evans, R., Nesi, J., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2021). Sexual communication in the digital age: Adolescent sexual communication with parents and friends about sexting, pornography, and starting relationships online. Sexuality & Culture, 25(6), 2092–2109. doi:10.1007/s12119-021-09866-1

- Xiao, C., & McCright, A. M. (2017). Gender differences in environmental concern: Sociological explanations. In Routledge handbook of gender and environment (pp. 169–185). London, England: Routledge.

- Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2014). “Sexting” and its relation to sexual activity and sexual risk behavior in a national survey of adolescents. Journal of adolescent health, 55(6), 757–764. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.012

- Yépez-Tito, P., Ferragut, M., & Blanca, M. J. (2019). Prevalence and profile of sexting among adolescents in Ecuador. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(4), 505–519. doi:10.1080/13676261.2018.1515475

- York, L., MacKenzie, A., & Purdy, N. (2021). Attitudes to sexting amongst post-primary pupils in northern Ireland: A liberal feminist approach. Gender and Education, 33(8), 999–1016. doi:10.1080/09540253.2021.1884196

- Zilberman, N., Yadid, G., Efrati, Y., Neumark, Y., & Rassovsky, Y. (2018). Personality profiles of substance and behavioral addictions. Addictive behaviors, 82, 174–181. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.007