ABSTRACT

Background: Recent meta-analytical findings indicate that affect regulation plays an important role in alcohol craving, consumption volume, and substance use. However, in view of mixed findings, the affect and drinking likelihood literature remains in need of clarification and consolidation.

Objectives: This systematic review with meta-analyses interrogated the results from peer-reviewed studies among non-clinical populations that examined the relationship between daily affective states and intraday likelihood of alcohol consumption.

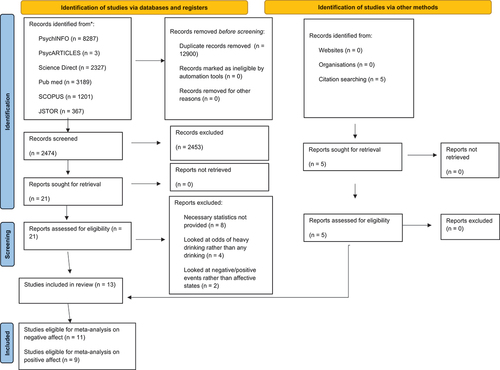

Method: A PRISMA guided search of PsychINFO, PsycARTICLES, Science Direct, Wiley Online Library, PubMed, SCOPUS, and JSTOR databases was conducted. Multilevel meta-analyses yielded 11 eligible negative affect studies (2751 participants, 23 effect sizes) and nine studies on positive affect (2244 participants, 14 effect sizes).

Results: The pooled associations between intra-day affect and alcohol consumption likelihood revealed no significant association between negative affective state and drinking likelihood (OR = .90, 95% CI [.73, 1.12]) and that positive affect was associated with increased drinking likelihood (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.09, 1.27]). Egger’s test, P-curve, fail-safe N, and selection models analyses suggested that the obtained results were unlikely to be the product of publication bias and p-hacking alone.

Conclusions: Results converge to suggest that, independent of age, affect measure used, and study design, a significant albeit modest relationship between positive affect and alcohol consumption likelihood exists, which does not appear to be the case for negative affect. In conjunction with other recent meta-analyses, current findings help map out a more nuanced understanding of the affect-alcohol/substance use relationship, with potential implications for interventions.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

These comprehensive meta-analyses on the impact of within-day affective states on alcohol consumption suggest that increased positive but not negative affect is associated with greater likelihood of alcohol consumption.

Introduction

It is commonly believed that alcohol has the ability to impact people’s mood (e.g., Citation1). The cultural association of alcohol with both celebratory (e.g., birthdays) and sad (e.g., funerals) life events in some societies also means that normative beliefs surrounding drinking (Citation2,Citation3) may help sustain the apparent link between affect and alcohol consumption. Empirical evidence, in this vein, suggests that alcohol consumption is associated with increased self-reported pleasurable moods (Citation4–8) and decreased nervousness, stress, anxiety, tension, depression, and self-consciousness (Citation4,Citation8–12). Accordingly, a sizable body of literature theorizes that, in part, via association, individuals consume alcohol to control, or to moderate, their affective states (Citation13), and that mood management is a commonly anticipated outcome of drinking (Citation14). Drinking to improve positive states, or to cope with negative affect, is also frequently found to be associated with elevated consumption (Citation15–17), and recent meta-analytical findings indicate that emotion regulation abilities and substance use are intertwined (Citation18). At first sight, it may therefore be expected that the association between affect and consumption would be a consistent and fully understood phenomenon. However, to date, research examining the relationship between mood and drinking likelihood has yielded somewhat mixed findings. This contribution therefore aimed to meta-analytically examine the relationship between mood and the likelihood of consuming alcohol on a given day, and to investigate potential moderators of this association.

According to the positive reinforcement theory of alcohol use, people drink alcohol to enhance positive emotions they are currently experiencing (Citation19). Indeed, enhancement drinking motives and positive alcohol expectancies appear to be important drivers of consumption in different age groups (Citation17,Citation20–22). However, findings with regard to the extent to which people’s current positive affective states impact drinking behavior have been varied. While some studies have found that positive mood increases within-day alcohol consumption (Citation23–27), others indicate that positive affect has no impact on daily alcohol consumption volume (Citation28–34) or on alcohol craving (Citation35). In view of this inconsistent support for the positive reinforcement model of alcohol consumption in non-clinical populations, formal interrogation of the findings is required to shed light on the relationship between positive mood and the likelihood of drinking.

In a similar vein, in accordance with the self-medication hypothesis (Citation13) and negative reinforcement models of alcohol use (Citation36), research also documents an association between poor mental health and hazardous drinking (Citation37), such that people may use alcohol as a means of trying to overcome low mood. In line with this assertion, symptoms of depression, anxiety disorder are highly comorbid with alcohol use disorders (Citation38,Citation39). Nevertheless, research in this domain has not produced findings that are as consistent as these established theories would predict. While, in non-clinical populations, there is evidence that negative moods are associated with substance use cravings and increased consumption (Citation40), it has also been found that such affective states do not impact alcohol consumption in people with and without mood disorders (Citation41,Citation42), that there is no association between negative affect and unplanned heavy drinking (Citation43), and that coping with depressive symptoms is unrelated to increased consumption (Citation44). Furthermore, other research indicates that negative affect is inversely related to drinking (Citation45). The existing literature therefore provides mixed support for the self-medication hypothesis in relation to alcohol consumption likelihood; however, to date a comprehensive meta-analytical interrogation of this relationship has not been published.

A potential reason for mixed findings concerning how affect may impact alcohol consumption relates to how outcomes are measured and conceptualized in relevant studies. Alcohol consumption can be assessed methodologically in different ways – e.g., amount consumed, rate of consumption, blood or breath alcohol concentration, alcohol cravings, or drinking likelihood. Previous meta-analytical findings in the field indicate that both negative and positive affect have a tendency to be associated with increased daily alcohol consumption volume (Citation46), that lab-induced negative affect may increase alcohol craving (Citation47), and that enhancement (i.e., to increase positive affect) drinking motives are associated with drinking problems and alcohol use, while coping (i.e., to deal with negative affect) drinking motives are associated with increased alcohol use (Citation48). However, there has been considerably less research regarding the impact of current mood on the likelihood of drinking onset.

Another potential reason for the mixed findings in this research area may relate to the variable use of measures that conceptualize affect in different ways. For example, while some scales conceptualise negative and positive affect as distinct constructs (Citation49,Citation50), others treat affect as a continuous construct that varies in valence and hedonic tone (Citation51,Citation52). Using diverse measures could therefore potentially lead to different interpretations of people’s affective states. As such, when scales such as the PANAS are used, participants may report experiencing both positive and negative emotions at the same time. On the other hand, when scales that conceptualize positive and negative affect as a bipolar continuum are used (Citation51), participants have to choose the affective state which they consider to be stronger at the moment they complete the measure. Yet, there is evidence people can experience both positive and negative affect simultaneously (Citation53) and that difficulties regulating positive and negative affect are distinct (Citation54). It follows that each affect dimension could account for unique (non-shared) variance and, as such, measuring affect as a bipolar continuum could be a potential confound within some previous research. Given the variety of different scales utilized in affect-alcohol research, which may vary in the extent to which they are accurately able to assess people’s current mood, affect scale was examined as a possible moderator in the present study.

Study design may also be a source of variability in previous research and offer insights into possible reasons for inconsistent previous findings. It is possible to examine drinking likelihood by using one-time surveys, daily diary methods, or ecological momentary assessment methods (EMA). However, studies tend to vary in length, with shorter studies potentially missing small effects (Citation55). While some studies have a duration of 7 days (Citation28,Citation56), others can last for up to 30 days (Citation57). Similarly, studies vary with regard to the number of assessments per day, with some using fewer assessments and thereby potentially missing nuances in the ways that daily affect could be associated with consumption patterns. As such, while some studies only require participants to complete one assessment per day (Citation57–59), others ask participants to complete up to 11 assessments (Citation28). Therefore, shorter studies and those using fewer prompts may not be able to capture fully the variability of mood throughout the day (Citation55). Another important aspect of study design is whether affect was measured prior to consumption. Studies that do not assess (or control for) this may prone to false-positive results (as findings may reflect the impact of alcohol on affective states, rather than the other way round). To examine this possibility, differences in study design need to be considered as part of meta-analyses of the mood alcohol relationship.

Another factor that could be a moderator of the relationship between affect and alcohol consumption likelihood is the age of participants taking part in relevant studies. While most research in the area has been conducted on adults, adolescents may also be prone to drinking in response to particular emotions. For example, studies indicate that adolescents experience both negative and positive emotions more intensely than adults (Citation60,Citation61), and increased affect intensity, in this way, may lead to a greater likelihood of drinking for emotion regulation purposes, compared to adults who may be more likely to deal with their stress and associated emotions in alternative ways (Citation62). Similarly, rates of depression and anxiety (Citation63,Citation64), and response intensity to stress (Citation65) tend to increase during adolescence. Thus, this life stage seems to be a period that is characterized by intense emotional experiences (Citation66) which, taken together with concomitant proneness to risk-taking (Citation67), could potentially contribute to elevated alcohol consumption. Indeed, individuals in their early-to-late teens and early 20s are among the heaviest episodic drinkers (Citation68), although findings on whether increases in negative affect during adolescence could be related to alcohol consumption have been inconsistent (Citation69–74), and recent research pointing to declining alcohol consumption among younger age groups must be acknowledged (Citation75,Citation76). With regards to positive affect, to our knowledge, there is a lack of studies on how this may impact the daily likelihood of alcohol consumption in adolescents, although research that examined this in young adults has yielded varied findings, with studies showing that both high (Citation77) and low (Citation78) levels of positive affect may be associated with alcohol consumption volume. Investigating the extent to which young people’s alcohol consumption likelihood may be associated with particular affective states could therefore yield insights into factors that drive their alcohol consumption.

Finally, wider literature documents the occurrence of a decline effect (Citation79) whereby effect sizes may decrease over time for a variety of possible reasons that include false-positive results, overestimation of effect sizes, under-specification of the conditions of the study, or genuinely decreasing effect sizes (Citation80), as well as methodological and analytical advances (Citation46). As a previous meta-analysis of the relationship between affect and alcohol consumption volume demonstrated a decline effect for studies on positive affect (Citation46), it is possible that studies examining the odds of consumption may also be susceptible to this phenomenon. Therefore, year of publication was also examined as a moderator in this study.

Accordingly, the current review aimed to meta-analytically synthesize empirical findings regarding the intra-day impact of affective states on alcohol consumption likelihood. To inform prevention efforts, this study focused on non-clinical populations as there might be potentially different drivers of alcohol consumption for clinical samples. Since positive and negative affect are distinct but related constructs that both appear to be linked to alcohol consumption (although the direction is unclear due to mixed findings), the decision was made to examine these separately. Several moderators, including affect measure, study design, participants’ age, year of publication, and whether the study insured that only pre-consumption affect was measured, were examined in the analysis. In light of literature highlighting different publications practices of outlets (Citation81), journal was another variable included as a moderator. Country and gender were also included in moderator analysis (following 18,46).

Method

Operational definitions

This review focused on daily alcohol consumption likelihood, which is defined as the odds of one’s alcohol consumption on a given day. Mood and emotions are distinct but interrelated constructs in that the former tend to be more stable and “flat”, while the latter are construed as more vivid and quick (Citation82). However, studies sometimes use these terms interchangeably. Therefore, to account for differences in the terminology, the terms ‘affect’, and ‘affective state’ are used in this review as umbrella terms for the experience of mood, emotion, or feelings.

Transparency and openness

We report how eligible studies were selected, the databases that were searched, what data were extracted, and the process of data analyses. Files used for data analysis, as well as the analysis code, can be found on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/cpf86//. The study design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Eligibility criteria

The literature search and eligibility criteria were developed prior to conducting the systematic review. The relevance of each study was assessed according to the following inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed papers; focus on the general human population (non-clinical sample); looking at affective states on the day of consumption; looking at consumption likelihood or odds of drinking (rather than alcohol consumption volume, rate of consumptions, blood alcohol concentration, or alcohol craving); conducting odds ratio analysis (or having statistics from which odds ratios along with the confidence intervals could be extracted); papers in English or Russian. The exclusion criteria were as follows: reviews, books, posters, and editorials; literature examining clinical samples (individuals with alcohol use disorders or any other clinical disorder). As there were no previous meta-analyses on the topic, the year range was not specified.

Studies examining positive and/or negative affect were included, as were those that measured affect on a continuum (i.e., where positive and negative affect are at polar ends of the same assessment spectrum) or as separate entities. Furthermore, studies that examined mean levels of affect (i.e., average negative or positive affect) as well as affect facets (i.e., specific emotions, e.g., stress, anger, or happiness) were included.

Literature review

The literature search was primarily conducted by the lead author. A comprehensive search was conducted of the following databases: PsychINFO, PsycARTICLES, Science Direct, Wiley Online Library, PubMed, SCOPUS, JSTOR using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (Citation83) and American Psychological Association’s Meta‐Analysis Reporting Standards (Citation84,Citation85) methodologies. The search terms were developed by primary author based on keywords used by relevant articles and were discussed and refined with the rest of the team prior to the start of data collection. The following commands were used for searching: (“alcohol consumption likelihood” OR “drinking likelihood” OR “odds of drinking” OR “odds of alcohol consumption”) AND (“mood” OR “emotion*” OR “affective states”) NOT “disorders”. After the initial literature search, to avoid missing data, the second author conducted a comparative title search using the same search terms and eligibility criteria to ensure the incorporation of any studies that may have been overlooked in the original review. Bibliographies from relevant reviews and book chapters, as well as articles that fit the inclusion criteria, were manually searched for additional citations. Full-text papers of any titles and abstracts that were considered relevant were obtained where possible.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Study quality was assessed using standard criteria (Citation86), with papers screened by two independent reviewers (Cohen’s Kappa =.71). None of the studies were judged to be of poor quality (and hence none were excluded), while three were deemed to be of moderate quality, and eight were classified as representing good quality.

Following the quality assessment, relevant data were extracted from each study (see for a full summary). The data were extracted by one of the authors using the Excel template (extracted data summarized in the table are available on the Open Science Framework) and subsequently checked by the first author. All effect sizes pooled from the studies were on the daily level of analysis. To examine how affect may impact subsequent drinking likelihood, effects of affect at time-1 were extracted from the papers. Some data sets provided multiple odds ratios for the constructs of interest (e.g., odds of drinking following sadness and following anger, both of which relate to the negative affect). Common ways of dealing with this problem include choosing a single outcome (Citation87) or aggregating all measures by computing an average effect size (Citation88); however, such approaches may lose information, rule out critical analyses of within-study factors (e.g., informant differences), artificially reduce the variance between effect sizes, and risk inaccurate estimation of study effect sizes (Citation89–91). Therefore, we used the robust variance estimation (Citation92) method to control for dependencies between effect sizes.

Table 1. Summary of the studies.

Meta-analysis - analytical strategy

Pre-calculated odds ratios, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, were used as effect sizes for meta-analyses. Meta-analyses on positive and negative affect were performed separately.

Analysis was conducted in R studio (Citation93) using the robumeta package (Citation94). First, odds ratios and their corresponding confidence intervals were log-transformed. Then, the standard error was calculated by extracting log-transformed lower confidence interval from the upper confidence interval and dividing it by 3.92. After that, the variance was calculated by squaring standard error. The intercept-only model was fitted using the robu function. Heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using I2 statistics. Because correlations between the effect sizes reported within each study were not known, we assumed a Spearman’s rho (ρ) of .80 (Citation92). We also performed a series of sensitivity analyses by testing different values of ρ in intervals of .10. This did not affect inferences about effect sizes; therefore, these results are not reported in the paper. Using tranf.exp.int function, the results were transformed back from the logs to odds ratios. Odds ratios greater than one indicated a positive association, odds ratios below one indicated a negative association.

Multiple moderators were examined, including journal, country, sample age (adolescents, young adults, adults), affect measure, the length of the study, the number of assessments per day, and whether the study controlled for the assessment of affect prior to drinking occasion. When analyzing affect measure as moderator, due to heterogeneity between the measures (e.g., using different items from PANAS, using a combination of PANAS with other measures), studies were classified into following categories: PANAS, Circumplex Model of Affect, and MAACL.

As the robumeta package does not support the function of building forest plots for odds ratios, cluster-robust models were fitted using the metafor (Citation95) and clubSandwich (Citation96) packages. Using transf.ext.int function, the results were transformed back from the logs. The forest plots were built using back-transformed odds ratios. Power of meta-analyses was calculated using an existing formula (Citation97).

In case of significant results, publication bias was examined via Egger’s test, which was performed by imputing standard error as a moderator to the main model. Additionally, the three-parameter selection model based on step functions was used to estimate the potential publication bias using the selmodel command. As the selmodel only accepts models created by metaphor’s rma function, the model was first fitted using this function. The cut-points of .025 was chosen, and, as a sensitivity analysis, a cutoff point of .05 was tested as well. To perform a p-curve analysis and assess potential p-hacking (Citation98), single-level models were used (computed using metagen function from meta package; (Citation99)). Similarly, to find outliers, find.outliers function was used on a single-level model. We also computed a fail-safe N, the number of additional “zero-effect” studies needed to increase the p-value for the meta-analysis to above .05 (Citation100). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to account for studies that were not included in meta-analyses. To account for family-wise error, Bonferroni corrections were applied to significant results.

Results

Quantity of research available

Electronic and hand searches identified 15,374 articles, which, once duplicates were removed, yielded 2474 unique citations to be screened for inclusion (). Their titles and abstracts were assessed for their relevance to the review, resulting in 21 potential articles being retained. The full texts of all these studies were obtained. After applying exclusion criteria for the remaining full-text papers, 14 articles were excluded. After that, full texts of eligible articles were screened to obtain additional citations. This resulted in screening five additional articles, all of which were retrieved and considered eligible. Overall, 13 studies were eligible for systematic review, 11 were eligible for the negative affect meta-analysis, and nine were eligible for the positive affect meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram summarizes the included studies for both negative and positive affect (see ). The main reason for the exclusion of studies was that they did not look at odds of alcohol consumption as an outcome.

Included studies were published between 2012 and 2021 and were conducted in various countries: Australia (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Netherlands (n = 1), and the USA (n = 10). Two studies sampled adolescents, seven studies sampled young adults, and two studies used adult samples. All studies utilized intensive longitudinal design methods. The number of assessments per day ranged from between one and 11, and the length of the studies varied from 7 to 30 days. Study characteristics are provided in , and a summary of effect sizes is provided in .

Table 2. Effect size summary.

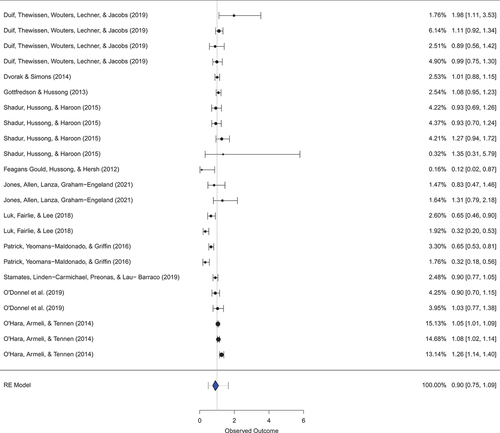

Association between daily negative affect and drinking likelihood

A total of 11 studies and 2751 participants are represented in the analysis. Odds ratio ranged from .12 to 1.98. Analysis revealed high levels of heterogeneity, I2= 82.34. The log-transformed effect size coefficient was β = −.10, CI [−.32, .12], SE =.10, t = > −1.09, p = .309. When the coefficient was transformed back into odds ratio, the result was: OR =.90, CI [.73, 1.12], indicating that there is no significant association between same-day negative affect and odds of alcohol consumption. The power of this meta-analysis was high (.88, assuming high heterogeneity). shows the sample effect size in the forest plot.

Moderation analysis

None of the moderators had a significant effect on study results. See supplementary materials for non-significant moderation findings.

Outliers

Four outliers were identified in a random-effects model (Citation28,Citation57,Citation101,Citation102). When analyzed without outliers (using single-level model), heterogeneity decreased (I2= 58.2), but the results of meta-analysis did not significantly change, OR =.96, CI [.89, 1.06], p = .485, as negative affect was still not significantly associated with consumption.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted, which included two additional samples, for which effect sizes were imputed as 0.0. This analysis yielded a weighted mean effect size of estimate = −.05, 95% CI [−.33, .24], p = .734. This indicates that the missing data likely had little effect on the estimate of the effect size and significance. The results of the sensitivity analysis did not reveal significant differences with different values of Rho. Consequently, these results are not reported in the paper.

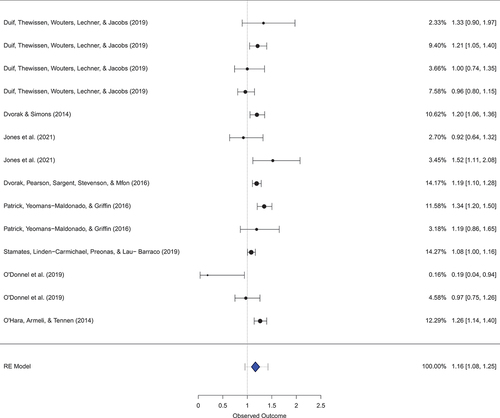

Association between daily positive affect and drinking likelihood

A total of 8 studies and 2244 participants are represented in the analysis. Odds ratio ranged from .19 to 1.52. Analysis revealed moderate levels of heterogeneity, I2= 54.97. The log-transformed effect size coefficient was β = .16, CI [.09, .24], SE =.03, t = 5.63, p = .003. When the coefficient was transformed back into odds ratio, the result was: OR = 1.17, CI [1.09, 1.27], indicating that there is a significant association between same-day positive affect and odds of alcohol consumption. When Bonferroni correction was applied (updated p value of .005), the results remained significant. The power of this meta-analysis was high (.99, assuming moderate heterogeneity). shows the sample effect size in the forest plot.

Moderation analysis

Country was the only significant moderator, but as degrees of freedom were lower than four, the estimate could not be trusted. See supplementary materials for the summary of results for non-significant moderators.

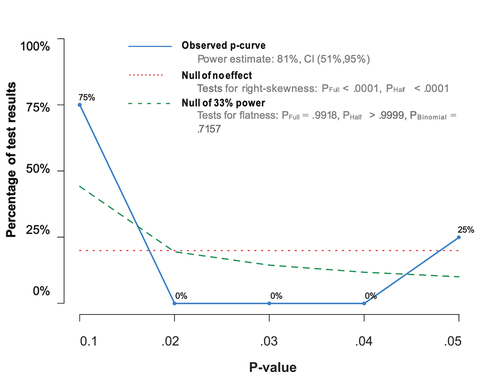

Publication bias

Egger’s test did not find significant results for publication bias (see summary of the model in the supplementary materials). P-curve analysis indicated that evidential value is present, and that evidential value is not absent or inadequate (see ). This means that P-curve estimates that there is a “true” effect size underlying finding, and that the results are unlikely to be the product of publication bias and p-hacking alone.

Figure 4. P-Curve analysis of studies examining the relationship between daily positive affect and odds of alcohol consumption. Most of the significant results were significant at p = .01 level, suggesting that the results are unlikely to be the product of publication bias or p-hacking alone. Note: the observed p−curve includes 8 statistically significant (p < .05) results, of which 6 are p < .025. There were 6 additional results entered but excluded from p−curve because they were p > .05.

In addition, the fail-safe N showed that 192 studies with OR =.00 would need to be incorporated into the meta-analysis to yield a non-significant effect. This markedly exceeded the benchmark of 115 (5n + 10) (Citation100), suggesting that our findings are robust to the threat that excluded studies might have yielded a non-significant effect.

The .025 selection model’s estimate of the true average effect size was .105, CI (95% CI [−.02 − .23]). When converted back to OR, OR = 1.110, 95% CI [.98, 1.26]. As the test of selection parameters were non-significant (χ2 = 1.40, p = .236), this indicates that the meta-analysis was not substantially biased by a lower selection probability of non-significant results. The analysis on .05 level also indicated that there was no substantial publication bias in the studies (logOR = .15, CI [.05, .24], when converted back OR = 1.16 [1.05, 1.28]).

Outliers

One outlier was identified in a random-effects model: O’Donnell et al. (2019). When analyzed without outlier (using single-level model), the results of meta-analysis did not significantly change, OR = 1.17, CI [1.09; 1.25], p < .001, as increased positive affect was still significantly associated with increased drinking likelihood.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted, which included four additional samples, for which effect sizes were imputed as 0.0. This analysis yielded a weighted mean effect size of estimate = .15, 95% CI [.08, .22], p < .001 ; OR = 1.16, CI [1.08, 1.25]. This indicates that the missing data likely had little effect on the estimate of the effect size and significance. The results of the sensitivity analysis did not reveal significant differences with different values of Rho; therefore, these results are not reported in the paper.

Discussion

Building on previous theoretical and empirical work (Citation13,Citation46–48,Citation103), the aim of this study was to clarify and consolidate the literature on the impact of intra-day affective states on alcohol consumption likelihood in non-clinical samples. Since there is evidence that positive and negative affect are distinct processes, two separate meta-analytic reviews were conducted on the impact of negative (review one) and positive (review two) affective states on daily alcohol consumption likelihood. Contrary to the self-medication hypothesis (Citation13), results indicate that negative affect was not associated with alcohol consumption likelihood, while a significant but weak association between increased positive affect and alcohol consumption likelihood was found. Present results were consistent across different age groups (adolescents, adults, and young adults), study design (number of days/assessments per day) and independent of affect conceptualization (i.e., scales used).

A reason for the association between positive (and not negative) affect and alcohol consumption likelihood may lie in the fact that alcohol is often used for celebratory occasions (Citation3), while, depending on personal characteristics, alternative strategies of coping with distress may be more prevalent in non-clinical samples (Citation104). In conjunction with the consolidated evidence base regarding daily affective states and alcohol consumption volume (Citation46), the current findings shed further light on what appears to be a complex relationship between affect and alcohol use. Specifically, recent meta-analyses suggest that experimentally induced negative affect is related to increased alcohol consumption volume and craving (Citation47), while elevated affect intensity (in both lab and field contexts) seems to be associated with increased alcohol consumption volume (Citation46). From the results of the current study, it appears that positive but not negative affect is associated with drinking likelihood on a given day. Seen in relation to the findings of previous meta-analyses in this field of research, this may therefore suggest that when drinking has already started, or if a drinking occasion is planned on a day characterized by increased negative affect, then it may be that affect intensity regulation, as opposed to valence, contributes to increased drinking volume (Citation46). That could explain the discrepancy between the findings of the current analyses and previous ones (Citation46,Citation47). From this perspective, people may not necessarily initiate alcohol consumption to deal with negative affect but such moods may contribute to elevated consumption volume if alcohol is readily available, or consumption has already commenced. On the other hand, people appear more likely to consume alcohol and drink more when they experience elevated positive mood (i.e., for enhancement drinking motives). As drinking alcohol is a normative way of celebrating in many Western societies (Citation105), individuals who are in a good mood, and want to celebrate, may be more likely to start drinking and to drink increased amounts. Further studies on whether the same holds true for clinical populations appear necessary, as a previous meta-analysis on emotion regulation and substance use points to larger effect sizes in clinical samples (Citation18), although a recent pre-print (Citation106) indicates that the same relationship between daily affect and alcohol consumption likelihood, observed in the current study, also holds in such samples.

Combined with results of previous studies, our findings could help to inform prevention efforts. As such, interventions for people who wish to reduce their alcohol consumption may focus on days characterized by increased positive affect (and/or planned celebratory occasions) and encourage individuals to engage in ways of elevating further their mood that do not involve alcohol consumption. On the other hand, for days characterized by increased levels of negative affect, such efforts may only be necessary if individuals plan drinking occasions, or when alcohol is readily available to them.

Considering study limitations, it is important to note that, while the power of our overall meta-analyses was high, it may still have been insufficiently powered to examine the effects of various moderators due to the number of available studies and their heterogeneity. It must also be noted that, owing to the inconsistent way data on socioeconomic status were (not) collected within the extant literature, it was not possible to conduct moderation analyses on this factor. Additionally, while the search terms were carefully selected and based on keywords utilized in the extant literature, no consultation with field experts or journal indexers was conducted, raising a potential concern of selection bias. Furthermore, this study was only concerned with drinking likelihood. That is, we looked at the odds of alcohol consumption on a given day. While there are meta-analytical studies that are concerned with drinking volume (Citation46) and alcohol cravings (Citation47), in order to fully understand the nature of the relationship between affect and alcohol consumption, future research is advised to examine other variables of interest such as blood alcohol concentration or rate of consumption. Furthermore, this review only focused on intra-day consumption. While this allowed us to examine the association between state affect, further examination of trait affect (i.e., tendency to experience particular affective states) could help answer the question of how longer-term affective states may be associated with alcohol consumption (Citation107). Similarly, not all studies made it clear whether they controlled for the temporal order of affect and alcohol consumption, and, although moderator analysis revealed no difference between the studies with regard to this, the results of some studies may have been biased by not controlling for the temporal proceedings of affect. More generally, there is also a need for studies to be adequately powered and to conduct longitudinal investigations given the dominance of cross-sectional work in this area.

We conclude that meta-analytic findings converge to suggest that increased positive affect is weakly associated with greater consumption likelihood in non-clinical populations, supporting the positive reinforcement model of alcohol use. The self-medication hypothesis was not supported as far as drinking likelihood as the dependent variable of interest is concerned. Combined with the contributions of previous consolidatory studies, the results of the present meta-analyses suggest that affective states and their regulation have a notable and nuanced influence on alcohol consumption behaviors.

Authors contribution

Anna Tovmasyan, Rebecca L. Monk, Ilona Sawicka, Derek Heim.

Supplementary_materials.docx

Download MS Word (26.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2022.2082300.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Babor TF, Berglas S, Mendelson JH, Ellingboe J, Miller K. Alcohol, affect, and the disinhibition of verbal behavior. Psychopharmacology. 1983;80:53–60. doi:10.1007/BF00427496.

- Gordon R, Heim D, MacAskill S. Rethinking drinking cultures: a review of drinking cultures and a reconstructed dimensional approach. Public Health. 2012;126:3–11. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.09.014.

- Heath DB. Drinking occasions: comparative perspectives on alcohol and culture. New York: Routledge; 2000. 208 p.

- Baum-Baicker C. The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;15:305–22. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(85)90008-0.

- Levenson RW. Alcohol, affect, and physiology: positive effects in the early stages of drinking. In: E., Gottheil, K. A., Druley, S., Pashko, S. P., Weinstein, editors. Stress and addiction. Philadelphia, PA, US: Brunner/Mazel; 1987. p. 173–96. ( Brunner/Mazel psychosocial stress series, No. 9)

- Miller MA, Bershad AK, de Wit H. Drug effects on responses to emotional facial expressions: recent findings. Behav Pharmacol. 2015;26:571–79. doi:10.1097/FBP.0000000000000164.

- Rot MAH, Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Young SN. Alcohol in a social context: findings from event-contingent recording studies of everyday social interactions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:459–71. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00590.x.

- Smith RC, Parker ES, Noble EP. Alcohol and affect in dyadic social interaction. Psychosom Med. 1975;37:25–40. doi:10.1097/00006842-197501000-00004.

- Hendler RA, Ramchandani VA, Gilman J, Hommer DW. Stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol. In: Sommer W R Spanagel, editors. Behavioral neurobiology of alcohol addiction [Internet]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. [accessed 2020 Dec 4]. p. 489–509. (Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28720-6_135.

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol’s effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:459–76. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459.

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–33. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921.

- Swendsen JD, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Willard A, Hromi A. Mood and alcohol consumption. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:198–204. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.198.

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997 Feb;4(5): 231–44.

- Demmel R, Hagen J. The structure of positive alcohol expectancies in alcohol-dependent inpatients. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:125–40. doi:10.1080/1606635310001634519.

- Cooper M.L, Russell M, Skinner J.B, Frone M.R, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1992;101(1), pp. 139.

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? a review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:841–61. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002.

- Stevenson BL, Dvorak RD, Kramer MP, Peterson RS, Dunn ME, Leary AV, Pinto D. Within- and between-person associations from mood to alcohol consequences: the mediating role of enhancement and coping drinking motives. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:813–22. doi:10.1037/abn0000472.

- Weiss NH, Kiefer R, Goncharenko S, Raudales AM, Forkus SR, Schick MR, Contractor AA. Emotion regulation and substance use: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230:109131. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109131.

- de Wit H, Phan L. Positive reinforcement theories of drug use. In: Kassel, JD, editor. Substance abuse and emotion. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2010. p. 43–60.

- Bot SDM, van der Waal JM, Terwee CB, van der Windt DAW, Schellevis FG, Bouter LM, Dekker, J. Incidence and prevalence of complaints of the neck and upper extremity in general practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:118–23. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.019349.

- Heim D, Monk RL, Qureshi AW. An examination of the extent to which drinking motives and problem alcohol consumption vary as a function of deprivation, gender and age. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021;40:817–25. doi:10.1111/dar.13221.

- Lee NK, Greely J, Oei TPS. The relationship of positive and negative alcohol expectancies to patterns of consumption of alcohol in social drinkers. Addict Behav. 1999;24:359–69. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00091-4.

- Cyders MA, Zapolski TCB, Combs JL, Settles RF, Fillmore MT, Smith GT. Experimental effect of positive urgency on negative outcomes from risk taking and on increased alcohol consumption. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:367–75. doi:10.1037/a0019494.

- de Castro JM. Social, circadian, nutritional, and subjective correlates of the spontaneous pattern of moderate alcohol intake of normal humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;35:923–31. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(90)90380-Z.

- Dinc L, Cooper AJ. Positive affective states and alcohol consumption: the moderating role of trait positive urgency. Addict Behav. 2015;47:17–21. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.03.014.

- Gautreau C, Sherry S, Battista S, Goldstein A, Stewart S. Enhancement motives moderate the relationship between high‐arousal positive moods and drinking quantity: evidence from a 22‐day experience sampling study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34:595–602. doi:10.1111/dar.12235.

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-Level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addict Behav. 2010;35:1045–53. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001.

- Duif M, Thewissen V, Wouters S, Lechner L, Jacobs N. Affective instability and alcohol consumption: ecological momentary assessment in an adult sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:441–47. doi:10.15288/jsad.2019.80.441.

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Day AM. Ecological momentary assessment of acute alcohol use disorder symptoms: associations with mood, motives, and use on planned drinking days. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22:285–97. doi:10.1037/a0037157.

- O’-Donnell R, Richardson B, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Liknaitzky P, Arulkadacham L, Dvorak R, Staiger PK. Ecological momentary assessment of drinking in young adults: an investigation into social context, affect and motives. Addict Behav. 2019;98:106019. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.06.008.

- Todd M, Armeli S, Tennen H. Interpersonal problems and negative mood as predictors of within-day time to drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:205–15. doi:10.1037/a0014792.

- Todd M, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Ball SA, Kranzler HR, Affleck G. Drinking to cope: a comparison of questionnaire and electronic diary reports. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:121–29. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.121.

- Tovmasyan A, Monk RL, Qureshi A, Bunting B, Heim D. Affect and alcohol consumption: an ecological momentary assessment study during national lockdown. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022; No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi:10.1037/pha0000555.

- Wardell JD, Read JP, Curtin JJ, Merrill JE. Mood and implicit alcohol expectancy processes: predicting alcohol consumption in the laboratory. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:119–29.

- VanderVeen JD, Plawecki MH, Millward JB, Hays J, Kareken DA, O’-Connor S, Cyders MA. Negative urgency, mood induction, and alcohol seeking behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:151–58. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.026.

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:33–51. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33.

- Appleton A, James R, Larsen J. The association between mental wellbeing, levels of harmful drinking, and drinking motivations: a cross-sectional study of the UK adult population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1333. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071333.

- Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, Lewinsohn PM. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:526–33. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

- Burns L, Teesson M. Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders: findings from the Australian National Survey of mental health and well Being. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:299–307. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00220-X.

- Cleveland HH, Harris KS. The role of coping in moderating within-day associations between negative triggers and substance use cravings: a daily diary investigation. Addict Behav. 2010;35:60–63. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.010.

- Stevenson BL, Blevins CE, Marsh E, Feltus S, Stein M, Abrantes AM. An ecological momentary assessment of mood, coping and alcohol use among emerging adults in psychiatric treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46:651–58. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1783672.

- Sutker PB, Libet JM, Allain AN, Randall CL. Alcohol use, negative mood states, and menstrual cycle phases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7:327–31. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05472.x.

- Fairlie AM, Cadigan JM, Patrick ME, Larimer ME, Lee CM. Unplanned heavy episodic and high-intensity drinking: daily-level associations with mood, context, and negative consequences. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:331–39. doi:10.15288/jsad.2019.80.331.

- Skule C, Ulleberg P, Lending HD, Berge T, Egeland J, Brennen T, Landrø NI. Depressive Symptoms in People with and without alcohol abuse: factor structure and measurement invariance of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) across groups. Plos One. 2014;9:e88321. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088321.

- Breslin FC, O’-Keeffe MK, Burrell L, Ratliff-Crain J, Baum A. The effects of stress and coping on daily alcohol use in women. Addict Behav. 1995;20:141–47. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(94)00055-7.

- Tovmasyan A, Monk RL, Heim D. Towards an affect intensity regulation hypothesis: Systematic review and meta-analyses of the relationship between affective states and alcohol consumption. Plos One. 2022;17:e0262670. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262670.

- Bresin K, Mekawi Y, Verona E. The effect of laboratory manipulations of negative affect on alcohol craving and use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Addict Behav. 2018;32:617–27. doi:10.1037/adb0000383.

- Bresin K, Mekawi Y. The “Why” of drinking matters: a meta-analysis of the association between drinking motives and drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:38–50. doi:10.1111/acer.14518.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

- Stern RA, Arruda JE, Hooper CR, Wolfner GD, Morey CE. Visual analogue mood scales to measure internal mood state in neurologically impaired patients: description and initial validity evidence. Aphasiology. 1997;11:59–71. doi:10.1080/02687039708248455.

- Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:1161–78. doi:10.1037/h0077714.

- Matthews G, Jones DM, Chamberlain AG. Refining the measurement of mood: the UWIST mood adjective checklist. Br J Psychol. 1990;81:17–42. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1990.tb02343.x.

- Larsen J, McGraw A, Cacioppo J. Can people feel happy and sad at the same time? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:684–96. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.684.

- Paulus DJ, Heggeness LF, Raines AM, Zvolensky MJ. Difficulties regulating positive and negative emotions in relation to coping motives for alcohol use and alcohol problems among hazardous drinkers. Addict Behav. 2021;115:106781. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106781.

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: a meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:660–81. doi:10.1037/a0023660.

- Jones DR, Allen HK, Lanza ST, Graham-Engeland JE. Daily associations between affect and alcohol use among adults: the importance of affective arousal. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106623. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106623.

- O’-Hara RE, Armeli S, Tennen H. College students’ daily-level reasons for not drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33:412–19. doi:10.1111/dar.12162.

- Howard AL, Patrick ME, Maggs JL. College student affect and heavy drinking: variable associations across days, semesters, and people. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29:430–43. doi:10.1037/adb0000023.

- Stamates AL, Linden-Carmichael AN, Preonas PD, Lau-Barraco C. Testing daily associations between impulsivity, affect, and alcohol outcomes: a pilot study. Addict Res Theory. 2019;27:242–48. doi:10.1080/16066359.2018.1498846.

- Diener E, Larsen RJ, Levine S, Emmons RA. Intensity and frequency: dimensions underlying positive and negative affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48:1253–65. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.5.1253.

- Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M, Graef R. Mood variability and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 1980;9:469–90. doi:10.1007/BF02089885.

- Amirkhan J, Auyeung B. Coping with stress across the lifespan: absolute vs. relative changes in strategy. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2007;28:298–317. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2007.04.002.

- Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Becker JB. Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones: evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior at adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:62–107. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62.

- Petersen AC, Compas BE, Brooks-Gunn J, Stemmler M, Ey S, Grant KE. Depression in adolescence. Am Psychol. 1993;48:155–68. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.155.

- Larson R, Ham M. Stress and ‘storm and stress’ in early adolescence: the relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:130–40. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.130.

- Silk J, Steinberg L, Morris A. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Dev. 2003;74:1869–80. doi:10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x.

- Mitchell IJ, Beck SR, Boyal A, Edwards VR. Theory of mind deficits following acute alcohol intoxication. Ear. 2011;17:164–68.

- Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:189–99. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001.

- Crooke AHD, Reid SC, Kauer SD, McKenzie DP, Hearps SJC, Khor AS, Forbes AB. Temporal mood changes associated with different levels of adolescent drinking: using mobile phones and experience sampling methods to explore motivations for adolescent alcohol use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:262–68. doi:10.1111/dar.12034.

- Gottfredson NC, Hussong AM. Parental involvement protects against self-medication behaviors during the high school transition. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1246–52. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.035.

- Gould LF, Hussong AM, Hersh MA. Emotional distress may increase risk for self-medication and lower risk for mood-related drinking consequences in adolescents. Int J Emot Educ. 2012;4:6–24.

- Hussong AM, Gould LF, Hersh MA. Conduct problems moderate self-medication and mood-related drinking consequences in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:296–307. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.296.

- Reimuller A, Shadur J, Hussong AM. Parental social support as a moderator of self-medication in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011;36:203–08. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.006.

- Colder CR, Chassin L. Affectivity and impulsivity. Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11:83–97. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.11.2.83.

- Kraus L, Room R, Livingston M, Pennay A, Holmes J, Törrönen J. Long waves of consumption or a unique social generation? Exploring recent declines in youth drinking. Addict Res Theory. 2020;28:183–93. doi:10.1080/16066359.2019.1629426.

- Vashishtha R, Livingston M, Pennay A, Dietze P, MacLean S, Holmes J, Herring R, Caluzzi G, Lubman DI. Why is adolescent drinking declining? a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Addict Res Theory. 2020;28:275–88. doi:10.1080/16066359.2019.1663831.

- Rankin L, Maggs J. First-Year college student affect and alcohol use: paradoxical within- and between-person associations. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:925–37. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9073-2.

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O, Yaeger A. Contributions of positive and negative affect to adolescent substance use: test of a bidimensional model in a longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav. 1999;13:327–38. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.13.4.327.

- Schooler JW. Metascience could rescue the ‘replication crisis’. Nat News. 2014;515:9. doi:10.1038/515009a.

- Protzko J, Schooler JW. Decline effects: types, mechanisms, and personal reflections. In: Lilienfeld, SO, Waldman, ID, editors. Psychological science under scrutiny: Recent challenges and proposed solutions. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 85–107.

- Niles MT, Schimanski LA, McKiernan EC, Alperin JP. Why we publish where we do: faculty publishing values and their relationship to review, promotion and tenure expectations. Plos One. 2020;15:e0228914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228914.

- Ekkekakis P. Affect, mood, and emotion. In: Tenenbaum, GE, Eklund, RC, Kamata, AE, editors. Measurement in sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL, US: Human Kinetics; 2012. p. 321–32.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

- APA. Reporting standards for research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2008;63:839–51. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.9.839.

- APA. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association. 6th ed. [Internet]. 2010 [accessed 2021 May 20]. https://apastyle.apa.org/products/4200066.

- Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields [Internet]. ERA; 2004 [accessed 2021 May 19]. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/48b9b989-c221-4df6-9e35-af782082280e.

- Card NA. Applied meta-analysis for social science research. Vol. xvi. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2012. 377 p.

- Cooper HM. Synthesizing research: a guide for literature reviews. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 1998. 218 p.

- Becker BJ. Multivariate meta-analysis. In: Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 2000. p. 499–525.

- Cheung SF, Chan DKS. Dependent effect sizes in meta-analysis: Incorporating the degree of interdependence. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004 Oct;89(5): 780–791.

- Cheung SF, Chan D-S. Dependent correlations in meta-analysis: the case of heterogeneous dependence. Educ Psychol Meas. 2008;68:760–77. doi:10.1177/0013164408315263.

- Hedges LV, Tipton E, Johnson MC. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:39–65.

- Rstudio | Open source & professional software for data science teams [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Jan 29]. https://rstudio.com/.

- Fisher Z, Tipton E. Robumeta: an R-package for robust variance estimation in meta-analysis [Internet]. arXiv [Preprint]. 2015 [accessed 2020 Sept 20]. p. 16. http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02220.

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v036.i03.

- Pustejovsky J. clubSandwich: cluster-robust (Sandwich) variance estimators with small-sample corrections [Internet]. 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 30]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=clubSandwich.

- Valentine J, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need?: a primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat [Internet]. 2010 [accessed 2022 Mar 30];35:215–47. doi:10.3102/1076998609346961.

- Simonsohn U, Nelson LD, Simmons JP. P-Curve: a key to the file-drawer. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143:534–47. doi:10.1037/a0033242.

- Schwarzer G. Meta: general package for meta-analysis [Internet]. 2021 [accessed 2021 Oct 18]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=meta.

- Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:638–41. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638.

- Luk JW, Fairlie AM, Lee CM. Daily-level associations between negative mood, perceived stress, and college drinking: do associations differ by sex and fraternity/sorority affiliation? Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53:989–97. doi:10.1080/10826084.2017.1392980.

- Patrick ME, Yeomans-Maldonado G, Griffin J. Daily reports of positive and negative affect and alcohol and Marijuana use among college student and nonstudent young adults. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:54–61. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1074694.

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990.

- Cooper H, Okamura L, Gurka V. Social activity and subjective well-being. Pers Individ Dif. 1992;13:573–83. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90198-X.

- Kuntsche S, Room R, Kuntsche E. Chapter 13 - I can keep up with the best: the role of social norms in alcohol consumption and their use in interventions. In: Frings D, and I Albery, editors. The handbook of alcohol use [Internet]. London: Academic Press; 2021 [accessed 2022 Feb 8]. p. 285–302. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128167205000244.

- Dora J, Piccirillo M, Foster KT, Arbeau K, Armeli S, Auriacombe M, Bartholow, BD, Beltz, A, Blumenstock, S, Bold, K, et al. The daily association between affect and alcohol use: a meta-analysis of individual participant data [Internet]. PsyArXiv; 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 30]. https://psyarxiv.com/xevct/.

- Treeby M, Bruno R. Shame and guilt-proneness: divergent implications for problematic alcohol use and drinking to cope with anxiety and depression symptomatology. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;53:613–17. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.011.