ABSTRACT

Background: Cannabis use in pregnancy is associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, yet its use among pregnant women in the United States has increased significantly.

Objectives: This cross-sectional study explored how cannabis use in pregnant women varied between different cannabis legalization frameworks, that is, permitted use of cannabidiol (CBD)-only, medical cannabis, and adult-use cannabis.

Methods: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data from 2017 to 2020 was utilized with respondents classified by their state’s policies into CBD-only, medical, and adult-use groups. Outcome measures included prevalence of use and usage characteristics (frequency, method of intake, and reason for use) among pregnant women. Logistic regression models were estimated to evaluate the association between legal status and prevalence of use.

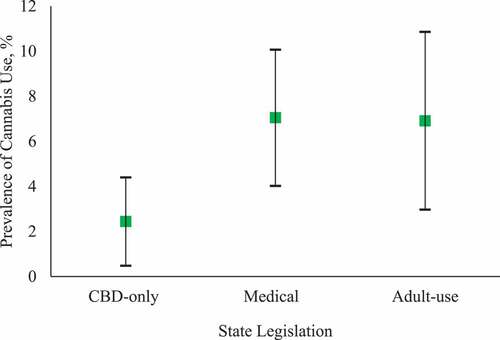

Results: The unweighted dataset included 1,992 pregnant women. Recent cannabis use was reported by (weighted proportions): 2.4% (95%CI: 0–4.4) of respondents in the CBD-only group, 7.1% (95%CI: 4.0–10.1) in the medical group and 6.9% (95%CI: 3.0–10.9) in the adult-use group. Compared to the CBD-only group, respondents in the medical and adult-use groups were 4.5-fold (adjusted; 95%CI: 1.4–14.7; p = .01) and 4.7-fold (adjusted; 95%CI: 1.3–16.2; p = .02) more likely to use cannabis. Across all groups, smoking was the most common method of intake and over 49% of users reported using partially or entirely for adult-use purposes.

Conclusions: The increased use with legalization motivates further research on the impacts of cannabis as a therapeutic agent during pregnancy and supports the need for increased screening and patient counseling regarding the potential effects of cannabis use on fetal development.

Introduction

Despite evidence suggesting that cannabis use during pregnancy is associated with adverse neonatal outcomes (Citation1), its use among pregnant women in the United States has increased significantly (Citation2,Citation3). Access to cannabis and the ability to consume it depends on a state’s legalization laws. Currently, states can be classified into three broad frameworks based on the extent of permissible use: illegal states that impose a complete ban or allow the highly restricted use of cannabidiol (CBD), medical states that permit use for wide-ranging medical conditions, and adult-use states that permit use for medical as well as adult-use purposes.

How the extent of legalization relates to cannabis use during pregnancy is not known. This is an important question in the current political environment wherein there is a push toward increasing acceptance of cannabis as a legal substance and enhancing accessibility to it at both state and federal levels. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends against using cannabis during the prenatal and postnatal periods (Citation4). Yet, insufficient screening for use, inadequate prenatal counseling about cannabis, and widespread legalization have resulted in the misperception among many pregnant users that cannabis is a safe substance (Citation5–10). More work is needed to understand the risk-benefit profile of using cannabis to treat pregnancy-related conditions, however, there is clear scientific evidence of the detrimental impact of cannabis on embryological development leading to poor obstetrical and fetal outcomes (Citation11). Understanding usage in legal versus illegal states serves as the first step towards developing cannabis-related public health policies focused on safeguarding pregnant women and newborns in states where cannabis is legalized.

Prior work on understanding cannabis use amongst pregnant woman has focused on states where cannabis is legal for adult use (Citation12–14). However, prevalence of use with respect to the extent of legalization (legal for limited medical use, legal for broad medical use, or legal for medical and adult-use) is not known yet. Our work aims to address this gap by using data gathered in recent years as part of a nation-wide survey.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of pregnant women using the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data from 2017 to 2020. The BRFSS survey is the largest national survey conducted annually and its design and analysis are overseen by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Individuals above the age of 18 are surveyed via telephone. The dataset is publicly available. Twenty-seven states and two territories that inquired about cannabis use in one or more years (Citation15,Citation16). They were categorized into one of the three exposure groups based on legalization policy: cannabidiol (CBD)-only (restricted use), medical, and adult-use. The CBD-only group consisted of Idaho, Indiana, Georgia, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wyoming. The medical group consisted of Delaware, Florida, Guam, Hawaii, Illinois (2017–2019), Maryland, Maine (January 2020), Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Puerto Rico, Utah, Vermont (2017–June 2018), and West Virginia. The adult-use group consisted of Alaska, California, Illinois (2020), Maine (February-December 2020), Vermont (July 2018–2019), and Washington. Illinois, Maine, and Vermont legalized adult-use effective January 2020 and July 2018, respectively. As such, they were categorized as medical states for the prior period and adult-use states thereafter. Respondents that were female, younger than 54 years, and pregnant at the time of the interview were included in the unweighted dataset.

The primary outcome was cannabis use in the past 30 days (binary). Individual weights were adjusted to reflect their contribution to the aggregate dataset (Citation17). Group differences were calculated using the chi-square test. Adjusted analysis was limited to the primary outcome measure using logistic regression accounting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, education level, income, alcohol use in the past 30 days, and self-reported mental health). As a descriptive, exploratory analysis we investigated frequency of use (<1 time per week or >1 time per week), method of intake (smoking or nonsmoking), and reason for use (medical, adult-use, or both) among those who reported recent cannabis use.

Statistical analysis was performed in R version 3.6.3 (R Core Team, Austria). A p-value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Of 121,648 women aged 18–54 years in the pooled dataset, 1,992 were pregnant at the time of the interview and eligible for inclusion (). Therefore, the unweighted dataset consisted of 426 CBD-only, 1,114 medical, and 394 reactional group respondents. Sociodemographic characteristics were similar between the three groups (). There was no association between state status and missing responses on cannabis use (p = .64).

Table 1. Weighted proportions for socio-demographics, health status, and substance use characteristics for the three groups.

Recent cannabis use was reported by 2.4% of respondents in the CBD-only group, 7.1% in the medical group, and 6.9% in the adult-use group (). The unadjusted odds of using cannabis in the medical group compared to the CBD-only group was 3.0 (95%CI: 1.2–7.8; p = .02), which increased to 4.5 (95%CI: 1.4–14.7; p = .01) upon adjustment. Similarly, the unadjusted and adjusted odds of using cannabis in the adult-use group compared to the CBD-only group were 3.0 (95%CI: 1.1–8.3; p = .03), and 4.7 (95%CI: 1.3–16.2; p = .02), respectively upon adjustment.

Figure 2. Weighted proportion of pregnant women reporting cannabis use in the last 30 days. The cannabidiol (CBD)-only group comprised of Idaho, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wyoming. The medical group comprised of Florida, Guam, Illinois, Maryland, Maine (January 2020), Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, Utah, Vermont (2017–June 2018), and West Virginia. The adult-use group comprised of Alaska, California, Illinois, Maine (February–December 2020), Vermont (July 2018–2019), and Washington. Using survey weights, the proportion of pregnant women reporting recent cannabis use in each of the three state groups were calculated. Error bars represent 95% CI associated with the weighted proportion of use. Recent use was reported by 2.4% of respondents in the CBD-only group, 7.1% in the medical group, and 6.9% in the adult-use group.

Secondary analyses were conducted to characterize usage among those reporting use (). Frequent use (>1 time per week) was reported by all users in the CBD-only group and two-thirds of users in both medical and adult-use groups. Smoking was the most common method of intake across all the three groups. Only a small proportion of users reported using for strictly medical reasons. A majority of users in all the groups reported the reason to be partially or entirely for adult-use purposes.

Table 2. Weighted proportions for secondary outcome measures among the subset of cannabis users.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the prevalence of cannabis use among pregnant women in the three general legalization frameworks. Self-reported use was significantly higher in pregnant women residing in states that allow medical and adult use compared to those residing in states with restricted use. Mode of intake and reason for consumption did not differ between state groups.

A few studies have assessed how use varies between states or how use has changed with legalization. Ko et al. (Citation18) evaluated cannabis use in 8 states in 2017 using the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data, albeit not in the context of legalization status. They found a wide variation in the proportion of users in legal states (2.6% in New York to 12.1% in Maine). Similar proportions for states in medical and adult-use groups were noted in our study. Young-Wolff et al. (Citation19) found a significant correlation between prenatal cannabis use and increased access following adult-use legalization in California. In contrast, Skelton et al. (Citation14) found an increase in use before and after pregnancy, but not during pregnancy, following legalization of adult-use in four states (Citation14). While these studies provide important information about the temporal change in use, no study to our knowledge has compared patterns of cannabis use across legislative frameworks.

Chang et al. (Citation5) and Kaarid et al. (Citation20) recently published their work on understanding why pregnant women consume cannabis. Using a qualitative approach, they collectively reported emesis, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and pain as the most common reasons (Citation5,Citation20). Similar reporting of “medical” reasons was noted in our study, but a large proportion of users also opted “recreational” (adult-use) as their purpose of use. With this insight, counseling patients around the risks of use (especially adult-use) and offering safer alternative treatments for pregnancy-related symptoms should be considered by those involved in prenatal care.

With respect to medical usage during pregnancy, cannabis has been reported to be effective for nausea and vomiting (Citation21). Medical cannabis may be suitable to treat pregnancy-specific conditions which, if untreated, could be more harmful to the fetus than cannabis (Citation22). Safe usage depends on having a comprehensive understanding of the benefits and risks of cannabis when weighed against the risks of untreated or refractory conditions such as hyperemesis gravidarum. Cannabis is a complex substance and its use is further complicated by factors such as the form of intake and frequency of use. From the maternal health standpoint, our current understanding is rudimentary regarding the complex interplay between use (whether CBD or THC-based) and long-term health outcomes for the mother. There is a growing body of evidence that cannabis is being used as a substitute for medical drugs among the public where use is legal (Citation23,Citation24). Therefore, it is increasingly important to evaluate the risk-benefit profile of cannabis as compared to other medical treatments to understand any potential therapeutic indications for cannabis use in pregnancy.

There is currently no accepted therapeutic indication or safe amount of cannabis that may be consumed during pregnancy. Although further studies may lead to an accepted therapeutic indication, based on the current consensus the positive association between cannabis use and legalization found in our study warrants further inquiry. A previous study exploring perceptions toward cannabis had found that women were more likely to use cannabis during pregnancy if it were legal (Citation25). This was reflected in this study as a high proportion of users reported adult-use consumption, even in medically legal states. This trend should be further investigated in order to implement meaningful public health measures and clinical strategies to address cannabis use.

Analysis was limited by relatively small sample size, lack of information regarding timing of use in pregnancy, lack of information about the chemical composition of cannabis consumed, and response and self-reporting biases (mitigated by the robust design and anonymous nature of the survey). State-level variations within legalization groups could not be studied due to the sample size. Information on use of other adult-use drugs and indication for use among medical users was not collected in this survey and could not be included in the analyses. Also, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot establish a causal relationship between legalization and cannabis use. However, the associations discovered herein identify aspects of cannabis usage that require further inquiry and monitoring.

Our findings suggest a need for prenatal and primary care providers to screen and counsel patients regarding cannabis use in pregnancy, particularly in states where it is legal. Increasing public messaging around the risks of cannabis in pregnancy is particularly relevant now as many states have recently implemented cannabis laws and established cannabis markets. Large-scale studies are needed to do an in-depth assessment of use related metrics. There is also an urgent need for a risk-benefit analysis of cannabis versus no treatment or current treatment options for pregnancy-related conditions. Ultimately, it is such granular information that will help identify opportunities for interventions to ensure safer use, if possible, during pregnancy.

Disclosure statement

Hance Clarke and Karim S. Ladha are co-principal investigators of an observational study on medical cannabis funded by Shoppers Drug Mart.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center KE, Nuñez A, Gibson SJ, Christ C, Ehiri JE. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016 Apr 1;6:e009986. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986.

- Alshaarawy O, Anthony JC. Cannabis use among women of reproductive age in the United States: 2002–2017. Addict Behav. 2019 Dec 1;99:106082. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106082.

- Volkow ND, Han B, Compton WM, McCance-Katz EF. Self-reported medical and nonmedical cannabis use among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2019 Jul 9;322:167–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.7982.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 722: marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130:e205–9. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002354.

- Chang JC, Tarr JA, Holland CL, De Genna NM, Richardson GA, Rodriguez KL, Sheeder J, Kraemer KL, Day NL, Rubio D, et al. Beliefs and attitudes regarding prenatal marijuana use: perspectives of pregnant women who report use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Mar 1;196:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.028.

- Holland CL, Rubio D, Rodriguez KL, Kraemer KL, Day N, Arnold RM, Chang JC. Obstetric health care providers’ counseling responses to pregnant patient disclosures of marijuana use. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Apr;127:681. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001343.

- Jarlenski M, Tarr JA, Holland CL, Farrell D, Chang JC. Pregnant women’s access to information about perinatal marijuana use: a qualitative study. Women’s Health Issues. 2016 Jul 1;26:452–59. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.03.010.

- Weisbeck SJ, Bright KS, Ginn CS, Smith JM, Hayden KA, Ringham C. Perceptions about cannabis use during pregnancy: a rapid best-framework qualitative synthesis. Can J Public Health. 2021 Feb;112:49–59. doi:10.17269/s41997-020-00346-x.

- Woodruff K, Scott KA, Roberts SC. Pregnant people’s experiences discussing their cannabis use with prenatal care providers in a state with legalized cannabis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Oct 1;227:108998. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108998.

- Young-Wolff KC, Gali K, Sarovar V, Rutledge GW, Prochaska JJ. Women’s questions about perinatal cannabis use and health care providers’ responses. J Women’s Health. 2020 Jul 1;29:919–26. doi:10.1089/jwh.2019.8112.

- Friedrich J, Khatib D, Parsa K, Santopietro A, Gallicano GI. The grass isn’t always greener: the effects of cannabis on embryological development. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016 Dec;17:1–3. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0085-6.

- Allshouse A, Metz T. Trends in self reported and urine toxicology (UTOX) detected maternal marijuana use before and after legalization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;214:S444–45. abstract only. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.904.

- Lee E, Pluym ID, Wong D, Kwan L, Varma V, Rao R. The impact of state legalization on rates of marijuana use in pregnancy in a universal drug screening population. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022 May 3;35:1660–7.

- Skelton KR, Hecht AA, Benjamin-Neelon SE. Association of recreational cannabis legalization with maternal cannabis use in the preconception, prenatal, and postpartum periods. JAMA Network Open. 2021 Feb 1;4:e210138. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0138.

- Vermont Department of Health. VA BRFSS [ dataset]. 2017–2019. Available upon request.

- Washington State Department of Health, Center for Health Statistics, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. WA BRFSS [ dataset]. 2017–2019. Available upon request.

- BRFSS. BRFSS complex sampling weights and preparing 2017 BRFSS module data for analysis [ ebook]. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2017/pdf/Complex-Smple-Weights-Prep-Module-Data-Analysis-2017-508.pdf.

- Ko JY, Coy KC, Haight SC, Haegerich TM, Williams L, Cox S, Njai R, Grant AM. Characteristics of marijuana use during pregnancy—eight states, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Aug 14;69:1058. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a2.

- Young-Wolff KC, Tucker LY, Alexeeff S, Armstrong MA, Conway A, Weisner C, Goler N. Trends in self-reported and biochemically tested marijuana use among pregnant females in California from 2009-2016. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318:2490–91. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.17225.

- Kaarid KP, Vu N, Bartlett K, Patel T, Sharma S, Honor RD, Shea AK. Assessing the prevalence and correlates of prenatal cannabis consumption in an urban Canadian population: a cross-sectional survey. Can Med Assoc Open Access J. 2021 Apr 1;9:E703–10. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200181.

- First OK, MacGibbon KW, Cahill CM, Cooper ZD, Gelberg L, Cortessis VK, Mullin PM, Fejzo MS. Patterns of use and self-reported effectiveness of cannabis for hyperemesis gravidarum. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2022 May;82:517–27. doi:10.1055/a-1749-5391.

- Sasso EB, Bolshakova M, Bogumil D, Johnson B, Komatsu E, Sternberg J, Cortessis V, Mullin P. Marijuana use and perinatal outcomes in obstetric patients at a safety net hospital. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Nov 1;266:36–41. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.09.015.

- Badowski S, Smith G. Cannabis use during pregnancy and postpartum. Can Fam Phys. 2020 Feb 1;66:98–103.

- Raman S, Bradford A. Recreational cannabis legalizations associated with reductions in prescription drug utilization among Medicaid enrollees. Health Econ. 2022;31:1513–21. doi:10.1002/hec.4519.

- Mark K, Gryczynski J, Axenfeld E, Schwartz RP, Terplan M. Pregnant women’s current and intended cannabis use in relation to their views toward legalization and knowledge of potential harm. J Addict Med. 2017 May 1;11:211–16. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000299.