ABSTRACT

Background: Sober living houses are designed for individuals in recovery to live with others in recovery, yet no guidelines exist for the time needed in a sober living house to significantly impact outcomes.

Objectives: To examine how the length of stay in sober living houses is related to substance use and related outcomes, focusing on early discontinuation (length of stay less than six months) and stable residence (length of stay six months or longer).

Methods: Baseline and 12-month data were collected from 455 sober living house residents (36% female). Longitudinal mixed models tested associations between early discontinuation vs. stable residence and abstinence, recovery capital, psychiatric, and legal outcomes. Final models were adjusted for resident demographics, treatment, 12-step attendance, use in social network, and psychiatric symptoms, with a random effect for house.

Results: Both early discontinuers (n = 284) and stable residents (n = 171) improved significantly (Ps ≤ .05) between baseline and 12 months on all outcomes. Compared to early discontinuation, stable residence was related to 7.76% points more percent days abstinent (95% CI: 4.21, 11.31); 0.88 times fewer psychiatric symptoms (95% CI: 0.81, 0.94); 0.84 times fewer depression symptoms (95% CI: 0.76, 0.92); and lower odds of any DSM-SUD (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.47, 0.89) and any legal problems (OR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.86).

Conclusion: In this study of sober living houses in California, staying in a sober living house for at least six months was related to better outcomes than leaving before six months. Residents and providers should consider this in long-term recovery planning.

Introduction

Sober living houses are a type of recovery residence, i.e., an alcohol- and drug-free living environment for individuals who want to abstain from substance use and pursue a program of recovery. While recovery residences go by different names and vary widely in structure, they have some common elements, e.g., requiring abstinence for residents. Recovery residences can be categorized into four levels (Citation1,Citation2). Level I residences are peer-managed, democratically run houses without paid staff members or on-site services located in residential neighborhoods, e.g., Oxford Houses (Citation3). Level II residences are also typically located in residential neighborhoods but are managed by someone who is either paid or receives a reduction of rent (e.g., senior resident, house manager). In Level II houses, usually no services are offered on-site, and residents are mandated or strongly encouraged to attend 12-step groups. Sober living houses in California are examples of Level II houses (Citation4,Citation5). Level III recovery residences pay staff who provide services on-site, e.g., linking to resources in the community, recovery support groups, and life skills training, while Level IV residences are basically residential treatment programs that employ licensed or credentialed professionals and provide a variety of on-site clinical services and more general structure than Level III residences (Citation6,Citation7).

Studies of sober living houses and other types of recovery residences (e.g., Oxford Houses and residential treatment programs) have documented significant, sustained improvements in multiple areas of functioning, including substance use, psychiatric severity, employment, and criminal justice involvement (Citation4,Citation8–13). Although there is no strict guideline for recovery housing, the National Institute on Drug Abuse emphasizes three months as a minimum time in residential treatment settings that is necessary to significantly impact substance use problems (Citation14).

According to research on Oxford House residents (N = 897), six months is the minimum requirement for living in an Oxford House, with stays of six months or longer related to increased self-efficacy and maintaining abstinence compared to stays less than six months (Citation15). Another Oxford House study of women who had been involved with the criminal justice system found that those who stayed six months or longer had better outcomes on substance use, employment, and self-efficacy (Citation16). The underlying theory for six months comes from the process of change theory, which describes the action stage as taking up to six months, followed by the maintenance phase; behavioral processes are important in both phases (Citation17). Generally, sober living houses offer a supportive environment to learn from other residents and implement new behaviors. With shorter length of stay, these behavioral processes may not have enough time to develop, thus putting those who leave sober living houses early at higher risk of relapse. However, studies of length of stay in recovery residences besides Oxford Houses are limited in number and interpretation, as length of stay is often included as an adjustment variable rather than a primary exposure of interest (Citation8,Citation9). For example, a study of 300 sober living house residents living in Northern California found no meaningful association with length of stay in the sober living house and psychiatric outcomes, though length of stay was included in analyses as a covariate, not a primary exposure, and measured in number of days as opposed to more than vs. less than six months (Citation9). Given that the number of sober living houses and other types of recovery residences is increasing (Mericle et al., 2016; Oxford House, 2021; Mericle et al., 2022), understanding how the length of stay in recovery residences is associated with substance use and related outcomes is becoming increasingly important.

Length of stay and recovery capital

Longer stays in sober living houses give residents time to interact with others in recovery and participate in a social model of recovery that has favorable outcomes, even when compared with clinically oriented treatment programs that are typically more expensive (Citation18). Based upon the mutual help principles of Alcoholics Anonymous, social model of recovery emphasizes the importance of peer support that involves interpersonal learning through sharing personal experiences and offering help. Since the aim of sober living is to prepare residents for life after the sober living house, these social model recovery experiences help residents build life skills in these areas and resources for a life without substances. One study found that when residents rate the social model activities in their sober living house, higher ratings were associated with greater recovery capital (Citation19). Similarly, a study of the Recovery Home Environment Scale, an 8-item scale that measures sober living house social model activities, found that the resident’s score predicts (Citation20). However, neither of these studies examined how the length of stay predicts recovery capital. Recovery capital gained through longer exposure to the social model of sober living houses might be the mechanism of action that has led to favorable outcomes in sober living houses, indicating a need to examine how length of stay is associated with recovery capital and other recovery outcomes.

Study rationale and aims

Not all studies have found that greater length of stay is significantly related to better outcomes (Citation9,Citation15). For example, in a study of 497 Oxford House residents, the length of stay was not a significant predictor of relapse in a multivariate model, though estimates were in the expected, protective direction (Jason et al., 2021). Despite research supporting six months as the minimum length of stay required for better outcomes, some residents may only need a shorter length of time to gain the recovery capital they need for long-term recovery. Furthermore, research on how the length of stay in sober living houses is related to recovery capital and related outcomes is lacking. Here, our primary aim is to examine how “early discontinuation” (i.e., leaving a sober living house within six months) vs. “stable residence” (i.e., living in a sober living house for at least six months) is related to substance use, recovery capital, and psychiatric outcomes in a sample of sober living house residents.

Materials and methods

The Public Health Institute’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Sample

We recruited 557 participants in 48 sober living houses located in 44 neighborhoods in Los Angeles County, California, from 2018 to 2021. Sober living house selection purposively maximized the diversity of the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood in which the study sober living houses are located; of the 48 houses enrolled, 27.1% were from the low socioeconomic quartile, 20.8% from the second quartile, 27.1% from the third, and 25.0% from the highest. Exclusion criteria made houses ineligible that included residents’ children, houses that had fewer than six beds, houses that had more than 25 beds, and houses that had advertised fees that were over $4,500 per month per person. Twenty-four houses were for men, 11 for women, and 13 for all genders. Nine houses were affiliated with a treatment program and 26 were part of a larger organization of sober living houses. All houses were members of the Sober Living Network, which provides member residences with support, guidance, advocacy, and certification for meeting national quality standards.

Participants were required to be ≥18 years of age, provide informed consent, have a history of drug and/or alcohol problems, provide tracking information for follow-up, and have been in the sober living house for less than one month at baseline to ensure they were new residents. All new sober living house residents (i.e., living in sober living house for <30 days) were able to participate if they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. As part of the consent process, the interviewer would explicitly clarify that participation was not required. Interviewers would contact the sober living house manager or owner on a regular basis to collect the number of new people who had entered the house. Throughout our recruitment period, approximately 987 new residents entered the 48 sober living houses enrolled; 557 (56%) residents ultimately participated in this study. Here, we focus on the 455 residents (82% of total sample) who have baseline, length of stay, and 12-month data. Bivariate tests showed no significant (P < .05) differences in baseline values of outcomes between those who did vs. did not complete the 12-month follow-up.

Interviews

Baseline interviews were conducted within 30 days of entering the sober living house; 12-month interviews were conducted 12 months after the baseline, though we allowed three extra months for participants to complete the 12-month interview. Participants were each assigned to one interviewer who stayed with them throughout the study. Interviews were conducted by field research staff trained in maintaining objectivity during data collection while also aiming to build rapport with study participants. The survey was designed to gradually ask more sensitive questions. Throughout their interactions, interviewers emphasized that they were not SLH staff and that the responses would not be shared with the house. Potential participants were informed that their decision to participate in the study was not contingent upon living at the SLH,and that their living at the SLH would not be affected by their answers. Prior to COVID restrictions that cut down on in-person data collection, we collected urine samples for drug testing, which was conducted off-site. The concordance rate for the samples and self-report of drug use on the TLFB was 98.2%.

Measures

Length of stay exposure variables

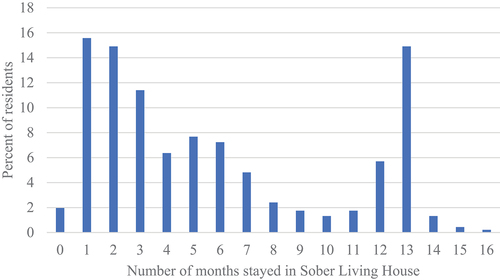

Our primary exposure was the resident’s length of stay in the sober living house, calculated as the number of days living in the sober living house at the 12-month follow-up. If a resident left the sober living house, e.g., for treatment, and later returned, their length of stay accounted for this break. illustrates the distribution of the length of stay in the analytic sample and shows a bimodal distribution, with residents generally staying either less than six months (180 days) or longer than six months. Analyses thus operationalized the length of stay in two ways: 1) as a dichotomous indicator of whether the resident had been living in the sober living house less than 180 days vs. 180 days or longer and 2) as a continuous measure of the number of days. From here on, we refer to resident who lived in the sober living house <180 days as “early discontinuers” (n = 284) and those who stayed ≥180 days as “stable residents” (n = 171).

Twelve-month outcome variables

We examined four continuous outcomes. First, since a primary goal of sober living houses is to eliminate or at least reduce substance use, our first outcome was percent days abstinent from alcohol and drugs (0–100%), measured using the Timeline Follow-Back (Sobell et al., 1996). Our second outcome was the number of psychiatric symptoms measured using the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Test, PDSQ (Zimmerman et al., 1999). The PDSQ counts symptoms related to 13 clinical disorders, including those common among persons with substance use disorders, e.g., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychotic disorders. In addition to modeling the number of depression symptoms endorsed, we calculated an overall PDSQ score (115 items across the 13 disorders) and used the natural log of PDSQ scores in regression analyses because of skewness in the distributions. The PDSQ is a self-report scale that has strong levels of internal consistency, reliability, and validity and is used for screening respondents for common psychiatric disorders, including Major Depressive Disorder (Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001). Our fourth measure, recovery capital, was measured using White’s (2009) Recovery Capital Scale of 35 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale with a possible range of 0–175. Higher scores indicate greater recovery capital. Prior studies have found this scale to have high internal consistency (Polcin et al., 2020).

We also examined two dichotomous outcomes: having a DSM-5 SUD diagnosis and having any legal problems. SUD diagnoses were determined from endorsing at least 2 of 11 symptoms on the DSM-5 Checklist for Drug and Alcohol Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and the legal problems were determined using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) legal subscale score that was dichotomized to indicate their absence (0) or presence (Citation1) (McClellan et al., 1992).

Statistical analyses

First, we used descriptive statistics to describe baseline characteristics and baseline measures of outcomes for the sample overall and within the early discontinuer and stable resident groups. Next, we used bivariate t-tests for continuous outcomes and chi-squared tests for dichotomous outcomes to test 1) changes in outcomes between baseline and 12 months within early discontinuer and stable resident groups and 2) differences in 12-month outcomes between early discontinuer and stable resident groups. Paired methods were used to test changes over time within groups. For our primary aim of examining how early discontinuation vs. stable residence is related to outcomes, we used multilevel regression to test whether dichotomous length of stay (≥180 days vs. <180 days) is related to each of the six outcomes. Sensitivity analyses operationalized the length of stay in number of days as a continuous exposure.

We used linear regression for the percent days abstinent and recovery capital scale outcomes, negative binomial regression for PDSQ and number of depression symptoms to account for their skewed distributions, and logistic regression for the two dichotomous outcomes. Final regression models adjusted for resident age, sex, race/ethnicity, whether they had attended inpatient treatment in the past 30 days before baseline, whether they had attended 12-step groups in the past six months before baseline, the percent of their social network that uses drugs and/or alcohol heavily at baseline, and baseline number of psychiatric symptoms as measured by the PDSQ. All regression models included a random effect and standard error adjustment for house with all covariates measured at baseline. All analyses were performed using Stata v17.

Results

Demographic characteristics and changes in outcomes over time

illustrates the distribution of the length of stay in our sample, showing peaks at around 1–2 months and 13 months. At the end of the study, average length of stay in the sober living house was 169 days and median length of stay was 128 days. describes baseline characteristics for the sample overall and by length of stay groups. In this sample, the average age was 40.4 years, 36% were female, and 47.4% were non-White. Most (91.7%) had gone to 12-step groups in the past six months, and most (72.6%) had a DSM-5 SUD diagnoses at baseline. Bivariate tests (not shown) yielded no significant (P < .05) differences in baseline characteristics between early discontinuers and stable residents.

Table 1. Baseline descriptives for sober living house residents followed at 12 months, sample overall (N = 455) and by length of stay groups.

shows 12-month outcomes among early discontinuers and stable residents and compares the two groups using bivariate t-tests for continuous outcomes and chi-squared test for proportions (%s). Across all outcomes, stable residents were significantly (P < .05) better off at the 12-month follow-up than early discontinuers, e.g., 45.8% of early discontinuers vs. only 23.3% of stable residents still have a DSM-5 SUD diagnosis. In bivariate tests examining changes between baseline and 12 months (not shown), both early discontinuers and stable residents improved significantly on all outcomes except for recovery capital, which significantly declined among early discontinuers but did not change significantly among stable residents.

Table 2. Twelve-month outcomes among early discontinuers and stable residents.

Results for primary aim

shows results from longitudinal mixed models regressing 12-month outcomes on a dichotomous indicator of stable residence vs. early discontinuation, adjusted for covariates. Length of stay was significantly (P < .05) related to every outcome except recovery capital, with stable residence having better outcomes vs. early discontinuation across the board: for example, stable residence was related to 7.76% points more percent days abstinent (95% CI: 4.21, 11.31), 0.88 times fewer psychiatric symptoms (95% CI: 0.81, 0.94), and 0.84 times fewer depression symptoms (95% CI: 0.76, 0.92). Stable residence was also related to significantly (P < .05) fewer depression symptoms, significantly lower odds of any DSM-SUD, and significantly lower odds of any ASI legal problems compared to early discontinuation.

Table 3. Results from multivariable multilevel modelsa regressing outcomes on stable residence (length of stay ≥180 days) vs. early discontinuation (length of stay <180 days) (N = 455).

Sensitivity analyses

Models operationalizing length of stay as a continuous exposure (Supplemental Table) showed small but significant associations between length of stay and outcomes. For example, each additional day in the sober living house was related to 0.035 additional percent days abstinent (95% CI: 0.02, 0.05) and 0.01 additional points on the recovery capital scale (95% CI: 0.00, 0.02). The effect sizes for other outcomes were too small to be meaningful, although they are significant at P < .05 (e.g., odds ratios of 1.00; Supplemental Table).

Discussion

Our primary aim was to examine how early discontinuation vs. stable residence in sober living houses is related to substance use, recovery capital, psychiatric, and legal outcomes. Stable residence, or living in a sober living house for six months or longer, is associated with more percent days abstinent, fewer psychiatric symptoms, fewer depression symptoms, lower odds of ongoing SUD, and lower odds of legal problems compared to early discontinuation or leaving a sober living house before six months. These results corroborate Oxford House research recommending six months as the minimum dose in a recovery residence (e.g., Jason et al., 2021). While many factors may impact how long a person needs to stay to get the full benefit of the sober living house experience, staying in a sober living house for at least six months appears to confer a wide range of benefits compared to leaving before six months. Sensitivity analyses confirm that each additional day in the sober living house is associated with modest but significant benefits. These findings have obvious implications for both sober living house residents and operators, e.g., residents should plan to stay in sober living houses for at least six months and sober living house operators should encourage residents to stay as long as possible. Recovery house scholarship programs and other funding sources (e.g., insurance companies) should also plan to cover length of stays for at least six months.

Interestingly, bivariate tests showed no differences in baseline characteristics between early discontinuers and stable residents. On the one hand, our analyses fail to suggest ways to a priori identify residents who might be at greatest risk for discontinuation; this is somewhat frustrating. On the other hand, it is very encouraging to imagine that all residents regardless of demographic characteristics, treatment and mutual help involvement, and clinical characteristics have equal likelihood of staying at least six months in a sober living house. Additionally, final models adjusted for several potential confounders known to be related to substance use and related outcomes, e.g., recent treatment and percentage of heavy users in social network. Thus, the baseline characteristics we studied likely do not explain why stable residents have better outcomes than early discontinuers. Future studies should examine a broader range of baseline characteristics, such as sexual/gender minority status or history of more complex and/or chronic services needs to investigate whether and how these residents may also benefit from sober living houses.

Further research should also more closely examine residents who stay less than six months because sober living house operators and residents need to understand why residents leave and what is associated with residents having a shorter length of stay. While many may leave prior to six months due to a relapse, what reasons are associated with early discontinuation? Are reasons for entering the house related to the length of stay? This line of research could examine possible interventions for re-engagement, methods to support, and ways to build recovery capital to maintain residency at the sober living house for those typically at risk to leave prior to six months. Though the early discontinuers still showed significant improvement here, further research is needed on how long these improvements last. Future research should also examine what happens to residents after they leave the sober living house, e.g., What type of housing do they move into for their next living situation and how is that associated with their long-term outcomes? Though some people may only need to stay at the sober living house for a shorter period of time to get the benefits they need, future studies should focus on defining characteristics of this group. Identifying factors that distinguish stable residence from early discontinuation could help inform sober living house operators and residents regarding risk and protective factors for the length of stay.

Limitations

Interviews for this study were conducted 12 months after their baseline interview, and for those still living at the sober living house, the length of stay was calculated from the time of entry until that interview date. Thus, the length of stay for those who were still at the sober living house could ultimately end up being longer; we expected any bias from underestimating the length of stay to be toward the null, i.e., relationships between length of stay and outcomes are likely stronger than reported here. Further research should examine how long these outcomes are maintained beyond 12 months. This study was also conducted when the COVID pandemic began, which likely impacted many people’s length of stay, from causing them to leave early to move in with family or to stay longer at the length of stay due to more limited housing options; ongoing analyses are examining reasons for leaving the sober living house and how various reasons for leaving relate to outcomes. Still, the current dataset is too small for examining a cutoff of 90 days (three months) per NIDA’s recommendations for residential treatment. Though sober living houses are distinct from residential treatment, future analyses will examine three months as an alternative minimum length of stay in sober living houses.

Eighteen percent of the study participants did not complete the 12-month interview and were therefore missing data on both length of stay and all 12-month outcomes. We tested differences in baseline values of outcomes between those who did vs. did not complete the 12-month follow-up interview: only number of depression symptoms differed at the P < .05 level, with those lost to follow-up reporting significantly more depression symptoms at baseline than those who completed the 12-month interview (average of 6.9 vs. 5.8, respectively). Thus, results might not generalize to sober living house residents with more depression symptoms.

Findings should not be viewed as indications of sober living house effectiveness per se because we do not have a comparison group of individuals not living in sober living houses. We are also unable to calculate sampling proportions or meaningfully assess generalizability. Sober living houses are not licensed or required to report their existence to any government agency, so it is impossible to know the exact number of residences in any particular area, but residences in this study were members of the Sober Living Network (SLN), the state-level affiliate of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR) implementing the NARR National Standard (NARR, 2018). However, this study was conducted in one type of recovery housing in one region of California, where the sober living houses were allowed to decide on participation and were all part of the SLN. This self-selection bias may mean that the houses that chose to participate may not represent the broad diversity of sober living houses in California or across the country.

While organizations like SLN and NARR offer many resources, including published standards and training workshops for running recovery houses, houses vary in many aspects, including sources of referral (e.g., treatment), staffing (e.g., counselor training, staff/patient ratio), architectural features, and others. As these house-level nuances are beyond the scope of this paper, we encourage future studies to examine how house-level factors impact tthe length of stay and whether meeting certain standards affects resident outcomes.

Conclusions

Results support that staying in a sober living house for longer than six months is related to better abstinence, psychiatric, SUD, and legal outcomes than staying less than six months. Future research should examine factors that distinguish stable residence and early discontinuation to better inform sober living house operators and residents regarding risk and protective factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the sober living house residents, managers, and operators who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Association of Recovery Residences. A primer on recovery residences: FAQ [Internet]. 2012 [accessed 2022 Sept 14]. https://narronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Primer-on-Recovery-Residences-09-20-2012a.pdf.

- Polcin D, Mericle A, Howell J, Sheridan D, Christensen J. Maximizing social model principles in residential recovery settings. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46:436–43. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.960112.

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Foli KJ. Rescued lives: the Oxford house approach to substance abuse. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2008. 268 p.

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Bond J, Galloway G. What did we learn from our study on sober living houses and where do we go from here? J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:425–33. doi:10.1080/02791072.2010.10400705.

- Mericle AA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Gupta S, Sheridan DM, Polcin DL. Distribution and neighborhood correlates of sober living house locations in Los Angeles. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58:89–99. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12084.

- Mericle AA, Miles J, Cacciola J. A critical component of the continuum of care for substance use disorders: recovery homes in Philadelphia. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47:80–90. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.976726.

- Mericle AA, Polcin DL, Hemberg J, Miles J. Recovery housing: evolving models to address resident needs. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49:352–61. doi:10.1080/02791072.2017.1342154.

- Mericle AA, Mahoney E, Korcha R, Delucchi K, Polcin DL. Sober living house characteristics: a multilevel analyses of factors associated with improved outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;98:28–38. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.12.004.

- Polcin D, Korcha R, Gupta S, Subbaraman MS, Mericle AA. Prevalence and trajectories of psychiatric symptoms among sober living house residents. J Dual Diagn. 2016;12:175–84. doi:10.1080/15504263.2016.1172910.

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Bond J, Galloway G, Lapp W. Recovery from addiction in two types of sober living houses: 12-month outcomes. Addict Res Theory. 2010;18:442–55. doi:10.3109/16066350903398460.

- Polcin DL, Korcha RA, Bond J, Galloway G. Sober living houses for alcohol and drug dependence: 18-month outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:356–65. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2010.02.003.

- Polcin DL, Korcha R. Social support influences on substance abuse outcomes among sober living house residents with low and moderate psychiatric severity. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2017;61:51–70.

- Witbrodt J, Polcin D, Korcha R, Li L. Beneficial effects of motivational interviewing case management: a latent class analysis of recovery capital among sober living residents with criminal justice involvement. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2019;200:124–32. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.017.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: a research-based guide. 2014 [accessed 2022 Sept 13]; NIH Publication No. 11-5316. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/principles-effective-treatment.

- Jason LA, Guerrero M, Salomon-Amend M, Light JM, Stoolmiller M. Personal and environmental social capital predictors of relapse following departure from recovery homes. Drugs. 2021;28:504–10. doi:10.1080/09687637.2020.1856787.

- Jason LA, Salina D, Ram D. Oxford recovery housing: length of stay correlated with improved outcomes for women previously involved with the criminal justice system. Subst Abus. 2016;37:248–54. doi:10.1080/08897077.2015.1037946.

- DiClemente CC, Scott CW. Stages of change: interactions with treatment compliance and involvement. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;165:131–56.

- Kaskutas LA, Zavala SK, Parthasarathy S, Witbrodt J. Costs of day hospital and community residential chemical dependency treatment. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2008;11:27–32.

- Polcin DL, Mahoney E, Witbrodt J, Mericle AA. Recovery home environment characteristics associated with recovery capital. J Drug Issues. 2020;51:253–67. doi:10.1177/0022042620978393.

- Mahoney E, Witbrodt J, Mericle AA, Polcin DL. Resident and house manager perceptions of social environments in sober living houses: associations with length of stay. J Community Psychol. 2021;49:2959–71. doi:10.1002/jcop.22620.