?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Recent literature shows that radical right parties (RRPs) present moderate or blurry economic stances. However, this paper argues that this blurriness is restricted to only one of the two main conflicts of contemporary welfare politics, namely questions centring on welfare generosity. In contrast, when it comes to the goals and principles the welfare state should meet, RRPs take a clear stance favouring consumption policies such as old age pensions over social investment, in accordance with their voters’ preferences. The empirical analysis based on new, fine-grained coding of welfare stances in party manifestos and original data on voters’ perceptions of party stances in seven European countries supports this argument. RRPs de-emphasise how much welfare state they want while consistently and clearly defending the traditional welfare state’s consumptive focus against recalibration proposals. These findings have important implications for party competition and welfare politics.

Radical right parties (RRPs) have emerged as a third pole in many West European countries’ party systems (Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018). While it has been shown that they mobilise voters primarily on non-economic socio-cultural issues such as immigration (Ivarsflaten Citation2005, Citation2008), their economic positions are less clear. Some scholars have depicted their positions as inconclusive (Rathgeb Citation2021), moderate (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018; de Lange Citation2007), and with high variation across time and space (Afonso Citation2015). Moreover, in an influential article, Rovny (Citation2013) argued that RRPs deliberately blur their positions on the economic dimension of conflict. Since the radical right attracts core constituencies with diverging preferences on economic issues, they have an interest in downplaying these issues and avoiding taking clear stances that might antagonise one part or another of their electorate.

We challenge this predominant view on party competition in welfare politics that RRPs blur all their economic positions. Recent arguments from welfare state literature have shown that the prevailing conflict about the welfare state is no longer concerned only with its size but rather with its goals, operating principles and whose needs the welfare state should cater to (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Bremer and Bürgisser Citation2020; Busemeyer and Garritzmann Citation2017). Should the welfare state prioritise investing in human skills to improve peoples’ earnings capacity or should it primarily serve as a safety net? Hence, welfare politics and the economic dimension itself have become multi-dimensional (Häusermann Citation2010; Roosma et al. Citation2013; van Oorschot and Meuleman Citation2012). Previous research has found that this new conflict dimension over social investment vs. consumption (termed recalibration of the welfare state) cuts across the traditional dimension of welfare state generosity, with different social and political groups occupying the poles of these dimensions. Most importantly, preferences on the recalibration dimension are closely aligned with attitudes towards universalism vs. particularism because of their joint socio-structural determinants and the distributive effects of investment or consumption policies (Beramendi et al. Citation2015).

Thus, while the constituency of RRPs is divided when it comes to welfare state generosity, this does not hold for the newly emerged conflict over social investment vs. consumption. The culturally conservative electorate of the radical right holds particularistic preferences and prioritises consumptive policies (see Busemeyer et al. Citation2021). Note that the emphasis lies on prioritisation; undoubtedly, a majority of voters, regardless of partisanship, support social policies, whether they are of the consumptive or investing kind. However, in a realistically constrained scenario where expansion involves (opportunity) costs, we expect the conflict over social investment vs. consumption to intensify along the lines of universalistic and particularistic preferences. Therefore, ambiguity in RRPs’ economic positioning should be restricted to questions about welfare state size or social policy generosity. On the contrary, we expect RRPs to take an explicit stance in favour of consumption over social investment. Hence, we add to existing research showing RRPs to take blurry, centrist or increasingly leftist welfare positions by differentiating what kind of a welfare state they prefer.

Our paper combines quantitative data based on election manifestos from seven West European countries, namely Austria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom, with individual-level data. In contrast to previous research measuring party positioning with manifestos, we draw on our own coding of manifestos to measure stances for specific social policy fields to differentiate between investment and consumption priorities. We complement this with aggregated individual-level data from an original survey that asked respondents about their perceptions of parties’ stances on the investment–consumption priorities dimension.

In line with previous research, we find that RRPs do blur their position on the general welfare state size dimension (Rovny and Polk Citation2020) by de-emphasising social policy issues. However, they unambiguously indicate what kind of welfare state they prefer, if any; of all party families, the radical right most clearly prioritises consumptive social policies such as old age pensions or healthcare over social investment. Moreover, voters recognise this consumption stance. In line with evidence from electoral manifestos, voters perceive RRPs as favouring consumption over social investment more than any other party. The public acknowledges the radical right as the main opposition to a recalibration of the traditional welfare state, thus suggesting that RRPs’ welfare state positions are not so blurry after all.

Radical right parties and the economy

RRPs have been doing well electorally and have become a major political force in most West European countries over the last three decades. The literature agrees that these parties have mobilised their voters and chalked up election victories mainly based on particularistic positions on socio-cultural issues, most prominently their anti-immigration stances. Twenty years ago, some commentators even went as far as characterising RRPs as single-issue parties. While this notion has been decidedly rejected in the meantime (see e.g. Mudde Citation1999), RRPs’ positioning on economic issues received relatively little scholarly attention for a long time. One of the first and most influential accounts of radical right economic positioning was developed by Kitschelt and McGann (Citation1997), who famously argued that RRPs have adopted a ‘winning formula’ by combining authoritarian positions (on socio-cultural issues) with neoliberal economic stances. According to Kitschelt and McGann, this programmatic appeal has allowed RRPs to build cross-class support by the working class (on socio-cultural grounds) and neoliberal small business owners (mostly on economic grounds).

However, academic interest in RRPs’ economic and welfare stances has sparked in the last decades, leading to disputes regarding the ‘winning formula’ argument. The radical right’s increasing vote share, these parties’ concomitant ‘normalisation’, their increased relevancy for government building (de Lange Citation2012), their occasional participation in government (Afonso Citation2015), and the recent economic crisis might all be reasons behind mounting interest in the radical right’s economic stances (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018). This newer research has shown that against the expectations of the ‘winning formula’, RRPs no longer present distinctly right-wing economic positions and argued that RRPs have very good reasons to refrain from advocating staunchly welfare-critical stances. On the contrary, a range of studies have placed RRPs around the centre of the economic dimension (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018; de Lange Citation2007; Kitschelt Citation2004) or have at least observed them moving to the left (Eger and Valdez Citation2015, Citation2019; Lefkofridi and Michel Citation2014; Rovny and Polk Citation2020). Consequently, when in government, they are rather reluctant to engage in welfare retrenchment (Röth et al. Citation2018) or then target cutbacks to specific social groups (Chueri Citation2020). As an alternative to describing RRPs’ economic stances as moderate, Rovny (Citation2013) especially has argued that RRPs have an incentive to blur their economic positions, i.e. to refrain from taking and communicating a clear position.

The concept of blurring is based on the idea that in a multi-dimensional setting, ‘political competition is not merely a struggle over where a party stands’ (Rovny Citation2012: 272) but rather a competition over the issues or dimensions that shape politics (e.g. Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015). According to Rovny, parties are well-advised to take a more pronounced stance on issues that are shared unequivocally by a party’s core constituency while opting to blur their positions on issues where they face a divided electorate – as RRPs do most prominently concerning the economy and the welfare state. Clearly, RRPs attract voters on the basis of their particularistic stance on the socio-cultural axis of political competition. Their electorate is united when it comes to opposing immigration, integration, or globalisation. However, their electoral strongholds strongly disagree on the economic dimension (Ivarsflaten Citation2005; Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018). Unsurprisingly, Rovny (Citation2013) and Rovny and Polk (Citation2020) find that RRPs engage in position-blurring by deliberately avoiding precise economic placement. They either de-emphasise economic issues altogether or present ‘vague, contradictory, or ambiguous positions’ (Rovny Citation2013). Furthermore, other authors have shown plenty of evidence that RRPs hold ambiguous economic positions (Mudde Citation2007; Rathgeb Citation2021).

When current research acknowledges RRPs as presenting clear social policy positions, this is with regard to a nativist, exclusionary stance towards immigrants. Many studies define this ‘welfare chauvinistic’ approach as the main distinctive feature of RRPs’ social policy program (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018; Otjes et al. Citation2018; Schumacher and van Kersbergen Citation2016): RRPs aim to limit welfare generosity to immigrants while maintaining principal support for a welfare state that caters to ‘deserving’ natives. We argue that welfare chauvinism is not the only distinctive characteristic of radical right welfare stances, which the current literature otherwise describes as moderate or even blurry.

The second dimension of welfare politics

Welfare state politics, which is traditionally seen as one of the main issues of the economic dimension, has fundamentally transformed over the last decades. Structural changes have had lasting effects on both citizens’ demand for social protection and elites’ leeway for providing the demanded coverage. These structural changes have come in the form of the rise of the service sector, educational expansion, demographic changes and altered family structures, which, in a highly interrelated way, have affected the demand and supply sides of social policy alike. The Great Recession further intensified and accelerated these impacts. The consequences for citizens’ demand for social policy are two-fold. First, general support for the welfare state has risen, especially among the middle classes. The literature has proposed several mechanisms that explain this shift, ranging from positive feedback (Pierson Citation2001; Svallfors Citation1997, Citation2007) and specific risks from which the middle class is not being spared (Häusermann et al. Citation2015; Jensen Citation2014) to the spread of egalitarian values among the new middle class (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Kitschelt Citation1994). Elsewhere, it has been empirically demonstrated that most voters are principally sympathetic to social policy expansion while cutbacks face tremendous opposition (Busemeyer and Garritzmann Citation2017; Garritzmann, Neimanns, et al. Citation2018; Kölln and Wlezien Citation2016).

Second, due to structural changes and the emergence of new social risks, needs for social policy have increased. As we argue, this means that voters need to prioritise different types of welfare provision or, in simpler terms, that voters prefer spending in some areas over spending in others. Moreover, increased financial constraints in times of ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson Citation2001) mean that expansions come at the cost of cutbacks elsewhere, higher taxes, or public debt. Hence, trade-offs have become crucial in policy making (Bremer and Bürgisser Citation2020; Busemeyer and Garritzmann Citation2017; Häusermann, Kurer, et al. Citation2019; Stephens et al. Citation1999), and voters are aware of these hard choices (Häusermann, Enggist, et al. Citation2019). Therefore, it is reasonable that people have different policy priorities and thus different preferences for the type of welfare state they support.

The most established way of thinking about the conflict concerning what the welfare state should do is the social investment paradigm (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Esping-Andersen et al. Citation2002; Hemerijck Citation2013; Morel et al. Citation2012). The logic of social investment policies differs from that of ‘passive’ or ‘consumptive’ social policies in that the former aims at ‘creating, mobilising, or preserving skills’ (Garritzmann et al. Citation2017: 37) in order to support citizens’ earnings capacity. The most typical examples of social investment policies are childcare, tertiary education and active labour market measures. Consumption policies, in contrast, include measures such as old age pensions or unemployment benefits that primarily aim to compensate for income losses. While variables such as ideology, income and gender may explain support for either of the two, a different set of variables hold explanatory power when investment comes at the cost of consumption (Busemeyer and Garritzmann Citation2017; Garritzmann, Busemeyer, et al. Citation2018). It follows that social investment policies not only differ in their logic but also in the way that the conflict around them is structured. While the new middle class has partly moved towards the working class when it comes to general support for social policy, such convergence is clearly absent in investment–consumption priorities where the more highly educated and more culturally liberal middle class is more favourable to social investment (Garritzmann, Busemeyer, et al. Citation2018; Häusermann et al. Citation2021).

In sum, the conflict over the recalibration of the welfare state is masked if we focus only on general support for the welfare state. Conflict over the size of the welfare state is different from conflict over social investment vs. consumption priorities.Footnote1 Therefore, when studying welfare politics, it is reasonable to capture social policy preferences also through actors’ priorities (may it be individuals, classes, or parties) rather than only through their positions.

Welfare state research has over the past 15 years increasingly acknowledged both the multidimensionality of welfare preferences (i.e. support for one social policy can easily coincide with opposition against another social policy) and the importance of constraints to understand welfare politics. We stand in the tradition of this research which has first begun to investigate support for specific policies rather than support for general welfarism and has increasingly added constraints and trade-offs to measure voters’ priorities rather than positions. While the bulk of this research is concerned with the demand side of political competition, both multidimensionality and the increasing importance of priorities are progressively acknowledged in studies of welfare party politics (Abou-Chadi and Immergut Citation2019; Green-Pedersen and Jensen Citation2019).

Radical right voters in two-dimensional welfare politics

For many decades, the working class has been the core constituency of the left while upper and middle classes have lent their support predominantly to conservative, liberal or Christian–democratic parties. However, socio-structural transformations in post-industrial societies, the emergence of new party families, and the increasing salience of issues such as immigration have led to the emergence of new ties between parties and classes. Most notably, the working class has become the backbone of support for the radical right (Oesch Citation2008; Rydgren Citation2012). In contrast, the well-educated, new middle class, especially professionals working in health, education, welfare, or the media sector – the so-called socio-cultural professionals – have become the preserve of Left parties in most West European countries (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018). However, more traditional sectors of the middle class, most prominently small business owners, are a ‘contested stronghold’ of the centre-right due to their right-wing economic preferences; however, mostly due to their scepticism of immigration and integration, they are also attracted to the radical right. Nevertheless, the proletarisation of the radical right (Bornschier Citation2010) has resulted in their largest vote potential lying within the working class.

This proletarisation has implications for RRPs’ positioning on the economic dimension. The increasing share of working-class voters has led them to move towards the centre or towards ‘blurring’ their stances on economic issues and welfare state generosity. In order to please their working-class voters’ demand for protection without jeopardising their traditional middle-class voters’ aversion to state-intervention, RRPs are expected to strategically blur their position (Rovny Citation2013; Rovny and Polk Citation2020).

We argue in this paper that the situation of RRPs is completely different for the second dimension of welfare politics. Rather than focussing on the size or generosity of the welfare state, conflict in this dimension is about how the welfare state should be recalibrated, whose needs it should cater to, and what goals it should pursue. As discussed in detail below, the literature suggests that the radical right electorate occupies a predominantly consumption-oriented position due to a) their working-class voters’ material self-interest, b) a connection between consumption support and particularistic socio-cultural attitudes, and c) trust considerations.

The aforementioned proletarisation of RRPs shifts the median partisan’s placement towards prioritising consumption over social investment because, for the working-class constituency, it may be clearer whether and to what degree these benefits pay off. First, consumption policies materialise immediately whereas investments usually only pay off in the future. Second, willingness to invest in the future may depend on the economic outlook, which might be considered grimmer among working-class voters (Häusermann et al. Citation2021). Third, it has been shown that social investment policies suffer from ‘Matthew effects’, where the lower classes seem to have less knowledge about how to utilise investing policies such as childcare and labour market reintegration measures (Bonoli and Liechti Citation2018; Pavolini and Van Lancker Citation2018).

Moreover, even beyond self-interest, there is a link between support for the radical right and a preference for consumption over investment. Beramendi et al. (Citation2015) have postulated the existence of a nexus between the second, non-economic dimension of political conflict and emphasis on investment and consumption because of an inherent logical connection between universalism and social investment, and particularism and consumption. There are good reasons why prioritising consumption over investment fits with RRPs’ and their voters’ particularistic positions. First, the stabilising character of consumption-oriented social policies (e.g. pensions and contribution-based unemployment benefits) that promote rather than challenge traditional gender roles and the male breadwinner model should find an echo in culturally conservative attitudes. In contrast, many social investment policies enhance gender equality which is connotated to universalistic values (Busemeyer et al. Citation2021).

Second, consumption policies are more easily targetable towards specific groups that are perceived as being the most deserving of welfare benefits. Pension systems, for example, can be arranged so that they reward ‘hard-working’ native men but exclude labour-market outsiders and immigrants. Meanwhile, social investment policies such as education or childcare have the explicit goal of increasing equality of opportunity. Therefore, social investment policies tend to benefit groups such as atypical workers and immigrants as well. However, these groups the radical right would like to exclude or at least reduce in terms of their presence in the pool of welfare recipients (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018; Fenger Citation2018).Footnote2

Lastly, research has highlighted the importance of trust in government and political institutions as a vital factor in predicting support for social investment. Since social investment measures can be expected to pay off only in the long-term, are fraught with considerably more uncertainties than known, existing consumption policies, and depend on effective implementation, trust in political agents is essential for supporting (social) investment measures (Garritzmann, Neimanns, et al. Citation2018; Jacobs and Matthews Citation2017). RRPs, which usually have a strong populist component, however, frequently campaign on an anti-establishment platform that subverts citizens’ trust in politics and political elites. Concomitant with that, RRPs are especially successful in mobilising and attracting voters that have a low level of trust in politics, politicians and political institutions (Bélanger and Aarts Citation2006; Söderlund and Kestilä‐Kekkonen Citation2009). It follows that RRP voters are less likely to embrace social investment.

To summarise, the literature points to several mechanisms that account for a relationship between radical right support and the prioritisation of consumption over investment. This link is largely confirmed in empirical analyses (Busemeyer et al. Citation2021; Fossati and Häusermann Citation2014; Garritzmann, Busemeyer, et al. Citation2018; Häusermann, Pinggera, et al. Citation2020). Moreover, our own attempt replicates this finding (see Figure A1 in online appendix): radical right voters constitute the clear, exclusive pole in favour of prioritising consumption such as pensions over policies such as childcare or educationFootnote3. Their preference for consumption policies is statistically distinct from the preferences of all other electorates. If RRP voters want any social policy at all, they clearly prefer traditional, insurance policies.

Implications for radical right parties’ welfare state stances

What do these electorates’ positions mean for party behaviour and positioning in particular? We expect that if their electorates have heterogeneous preferences, parties have incentives to blur their stances on this issue. As previous literature has suggested radical right electorates have a centrist position concerning welfare state size (see also online appendix Figure A1). This might well be a result of their heterogeneous electorate, where the working class pulls them to the left while traditional middle-class constituents keep them on the right. Therefore, we expect RRPs to blur their position on welfare state size. These blurry positions are expected to be the result of an avoidance strategy (Koedam Citation2020) because the level of public support for the welfare state is generally high and opposition to retrenching existing benefits is even greater (although, as we show, there are differences in terms of degree). This means that even for parties that are rather opposed to generous social policies, it is not reasonable to campaign on a welfare retrenchment platform, especially since attracting attention to cutbacks is what makes retrenchment electorally dangerous (Armingeon and Giger Citation2008). Therefore, by de-emphasising social policy issues and thereby keeping the salience of the welfare state size dimension low, they limit the risks of alienating parts of their electorate.

Hypothesis 1: Radical right parties exhibit a blurry position on the welfare state size dimension by de-emphasising social policy.

However, we contend that in light of radical right voters’ clear position on the recalibration dimension, RRPs have no incentive to conceal their recalibration priorities. While all other party families might fear alienating substantial shares of their voters by clearly prioritising consumption over investment, a pro-consumption stance might be a unique feature of the radical right and a selling point that mobilises voters who are simultaneously concerned about preserving their pensions (among other consumption policies) but reluctant to expand social investment policies. Therefore, we expect RRPs to not blur their stances on the recalibration dimension at all.

Hypothesis 2: Radical right parties take a clear pro-consumption stance on the recalibration dimension.

The radical right’s clear stance in favour of consumption over investment is only relevant for party competition if it is recognised by the public. This cannot be taken for granted, considering, first, that RRPs are much more associated with a clear-cut anti-immigration platform rather than straightforward welfare stances and second, that their strategy of de-emphasising the welfare state size dimension might negatively affect the visibility of their social policy stances overall. Nevertheless, we expect the multi-dimensionality of welfare state politics to become apparent to voters during the current times of fiscal austerity. Voters should be able to identify which social policies parties prioritise over others. Therefore, we expect the radical right to be perceived as a clear force for preserving the welfare state’s traditional, consumptive focus.

Hypothesis 3: Radical right parties’ clear consumption stance resonates with the public’s party perceptions.

Data and measurement

We use data from two sources to assess parties’ welfare stances and citizens’ perceptions of these stances. Data for parties come from the Manifesto Research on Political Representation (MARPOR) corpus, while data for citizens and electorates are provided via an original survey. We are therefore able to combine data for 42 parties in seven countries (Austria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom). Data on citizens were collected between October and December 2018, while the data for parties came out of the latest available national election manifestos. Therefore, the set of RRPs includes the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), the Alternative for Germany (AFD), the League (LN), the Party for Freedom (PVV), the Progress Party (FrP), the Sweden Democrats (SD) and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP).Footnote4 Due to this composition, the case selection consists of a diverse set of RRPs that are situated in different welfare state regimes, have economically right or centrist legacies, and differ from each other in terms of power or relevancy (Afonso Citation2015; Nordensvard and Ketola Citation2015; Otjes et al. Citation2018). Nonetheless, despite their differences, all these RRPs face similar strategic considerations and, as we will show, they come to very similar decisions in terms of position-taking and (non-)blurring.

In order to identify the degree to which RRPs blur their position or take a clear stance when it comes to welfare politics, which is our dependent variable, we refine data from MARPOR (Krause et al. Citation2019). The project provides access to parties’ election manifestos, which have been split into so-called quasi-sentences. Each of these quasi-sentences, hereafter called statements, has been assigned to a broad policy category, such as, for instance, ‘Welfare State Expansion’. Horn et al. (Citation2017) have shown that this classification allows to meaningfully measure parties’ welfare positions. These data have been used extensively to identify or track party positions, also with regard to economic positioning of RRPs (e.g. Eger and Valdez Citation2015, Citation2019; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015; Lefkofridi and Michel Citation2014; Rathgeb Citation2021; Rovny and Polk Citation2020). However, today’s welfare state politics is not only about expansion, but also about recalibration. Hence, we need a more fine-grained measure of issue emphasis that allows us to disentangle statements concerning social policy into more specific statements regarding social investment and consumption. For this reason, we created the following coding scheme.

First, we ask whether a statement is about social policy. We are not interested in statements that only address revenue and not expenditures (e.g. taxation). Hence, mentioning or implying social policy and addressing the expenditure side are the two necessary conditions for a statement to receive further consideration in our coding. Second, for each statement addressing social policy, we are interested in whether a statement is a general claim for welfare expansion or whether it mentions or implies action in a clearly identifiable policy field. In the case of the latter, the third step classifies the respective statement into up to three of the following policy fields: old age pensions, unemployment benefits, social assistance, (passive) family policy, healthcare, early childhood education and care (ECEC), tertiary education, education (neither ECEC nor tertiary, including primary, secondary, vocational, or further education), and active labour market policies (ALMP). Statements that do not refer to one of these policy fields are coded as ‘other’ (e.g. housing or disability related measures). Dependent on these fields, all social policy statements are then classified as either social investment (including all claims directed to ECEC, education, tertiary education, or ALMP) or consumption (including all claims directed to pension, unemployment benefits, social assistance, (passive) family policy, or healthcareFootnote5). If a statement addresses exactly one investment and one consumption field, it is assigned to the ‘ambiguous’ category. Lastly, we code whether the sentiment of the statement is positive (i.e. expanding, increasing, spending more), negative (i.e. retrenching, decreasing, spending less), or neither. This detailed coding scheme is applied to all statements originally coded in those existing categories that potentially engage with social policy.Footnote6 The total number of coded statements adds up to 25,413, of which 9491 mention or imply social policy action and could therefore be classified as statements regarding social investment or consumption.

Using this data, we operationalise party behaviour with respect to the two dimensions of welfare politics in the following way. For the welfare state size dimension, we take a manifesto’s share of positive social policy statements as an indicator of emphasis on welfare issues.Footnote7 For the recalibration dimension, we are interested in whether RRPs take a clear consumption (as expected), a clear social investment profile, or whether they are more ambiguous, with their position remaining blurry. Ambiguity would result from a situation in which a party talks as much about investment as about consumption. More specifically, we take the number of positive statements on social investment and the number of negative statements on social consumption as a share of all statements on either of the two:Footnote8Footnote9

Different data has been used to measure parties’ recalibration profile through citizens’ perceptions. We use original data (Häusermann, Ares, et al. Citation2020) from an online survey that involved 12,500 respondents and was conducted between October and December 2018 in eight Western European countries (of which we use Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, Italy, Sweden and Denmark, see online appendix A3).

Beyond a wide range of items capturing social policy priorities, the survey includes questions that ask respondents to evaluate parties’ welfare state recalibration profile. More specifically, respondents were asked how they think a given party X would prioritise social policy spending in different policy fields. To answer this question, they were given 100 points to distribute across six social policy fields in the way they would expect party X to prioritise these expenditures.Footnote10 We then compute a recalibration score that is simply the number of points given to social investment fields as a share of the points given to all the five relevant fields that were included. For each party, we then aggregate (by taking a weightedFootnote11 mean) the answers the respondents gave.Footnote12 Parties with a higher mean are perceived as being pro-social investment, while parties with a lower mean are perceived as being pro-consumption.

Results

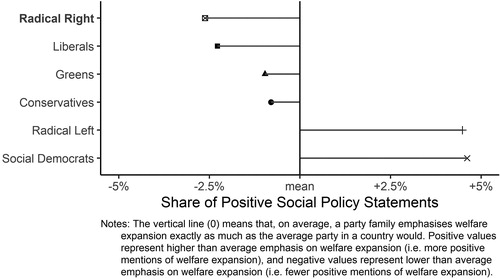

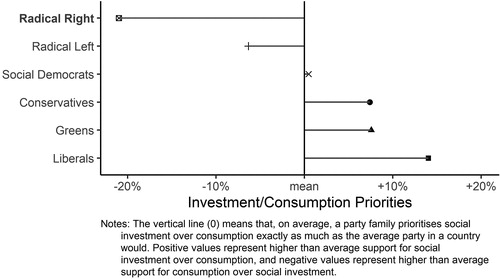

and show how the radical right positions itself relative to other party families on the welfare state size dimension (), measured as the number of positive social policy statements as a share of all manifesto statements, and on the recalibration dimension (), measured as the number of positive social investment and negative consumption statements as a share of all social policy statements. We show aggregated differences to country means rather than absolute values to prevent a bias due to the different representations of party families among countries. Therefore, in , a value of 0 means that, on average, a party family occupies a position that corresponds to the country mean on welfare state generosity. Positive values indicate that a party family puts more emphasis on a large welfare state while negative values mean that less emphasis is put on a large welfare state. In , a value of 0 indicates that a party family on average puts a relative weight on investment and consumption that corresponds to the mean. Positive values indicate that a party family prioritises investment more than other party families do, while negative values mean that a party family prioritises consumption more than other party families.

As stated in Hypothesis 1, we expect RRPs to de-emphasise social policy. confirms this expectation. Of all party families, RRPs devote the least attention to the welfare state in their election manifestos, with manifesto space that is devoted to welfare expansion amounting to around 3 percentage points less than average. Even parties with constituencies that are less dispersed and are overall more sceptical of social policy expansion, such as the liberals or the conservatives, put more emphasis on social policy. Hence, RRPs might strategically downplay the relative importance of economic issues as a reaction to their constituency’s division in terms of economic preferences. These considerations mirror existing findings on the radical right’s position blurring (Rovny Citation2013; Rovny and Polk Citation2020).

As Figure A6 in the online appendix shows, this finding holds for most countries. AFD, PVV and UKIP each devote the lowest share of their manifestos to social policy. Likewise, FrP emphasises the welfare state less than centre-right and left parties but is undercut by MDG (Greens). In Italy, LN is levelled with other parties on the right but is still considerably less prone to focus on social policy. The picture for Austria and Sweden is somewhat different. While we also find the left at the strong emphasis pole, and the centre-right at the opposite, the placements of both FPÖ and SD are located towards the centre. While the former case is somewhat surprising, the latter confirms existing evidence that contrary to some other European RRPs, the SD are rather supportive of a generous welfare state (Nordensvard and Ketola Citation2015), and that supporting a large welfare state has become a strategic policy tool in Scandinavian countries where a strong welfare state is deeply rooted in national identity (Jønsson and Petersen Citation2012; Kuisma and Nygard Citation2019), which is supported by the high shares observed for Norway as well.

In line with recent findings, RRPs seem to blur their position regarding typical economic issues such as welfare state generosity. However, we claim that even though they avoid putting too much emphasis on social policy, RRPs do take a very clear stance on what type of social policies they prefer, namely consumption policies. provides evidence in favour of this expectation. By far, RRPs reveal the highest share of statements in favour of consumption (relative to social investment). In fact, this share is more than 20 percentage points higher than the average. Hence, even though the salience of social policy issues is (strategically) kept low, RRPs present themselves as the strongest preservers of a traditional, consumptive welfare state and the fiercest opponents of welfare state recalibration. This result is not driven by specific policy fields as Figure A7 in the online appendix shows. For four out of five investment policies we find that RRPs put least emphasis on them while in contrast they emphasise consumption policies more than any other party family in five out of six fields, including unemployment benefits. While previous research has convincingly shown that the economic position of RRPs is ambiguous and that they blur their stances, our findings support these assertions with regard to how much welfare state they press for but not concerning what kind of a welfare state they prefer. Overall, this finding mitigates the ‘blurriness’ of RRPs’ economic position.

The opposite pro-investment pole is occupied by the parties that first and foremost cater to middle-class voters who are much more positive about social investment, namely the liberals, the conservatives and the greens. Faced with vertical cross-class coalitions, the social democrats and the radical left parties must cater to groups in their constituency that have quite distinct preferences when it comes to social investment and consumption priorities.

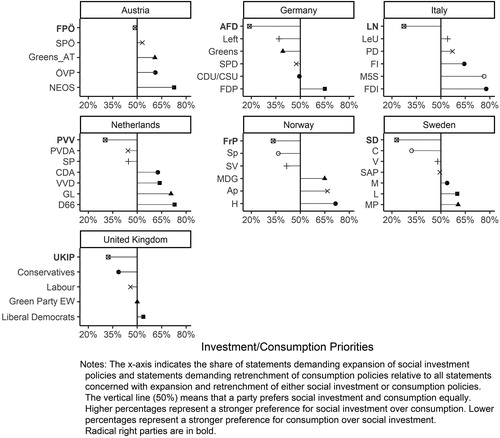

In order to delve deeper into the findings, disaggregates the evidence from by country. Here, we see that in all countries there are both parties that prioritise investment and parties that prioritise consumption. Moreover, the findings are replicated in all countries; in every country, it is the RRP that constitutes the consumptive pole. Only around a third or less of their positive statements are directed towards social investment. The only exceptional case is Austria, where we find a general trend towards social investment that does not leave the FPÖ unaffected, resulting from a comparatively strong national focus on both vocational and tertiary education. Likewise, the opposite pole is occupied by either green or liberal parties in all countries except ItalyFootnote13 (where there are no relevant green or liberal parties) and Norway (where it is the conservative party).

Figure 3. Positioning of individual parties on the recalibration dimension based on their election manifestos.

In electoral manifestos we have observed that the radical right indeed presents a clear preference for consumption over social investment. However, we have also discovered that to de-emphasise the first dimension of welfare politics, RRPs are rather reserved when it comes to talking about welfare in the first place. This begs the question whether their pronounced sympathy for consumption over investment is heard by voters and conveyed to the public. Looking at voters’ perceptions helps assess this question.

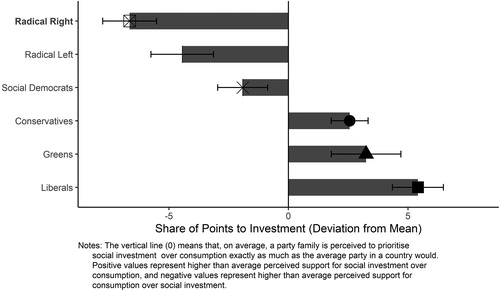

shows how party families are perceived by all voters, and it appears that public perceptions of party positions conform surprisingly well to parties’ communication in their respective manifestos.Footnote14 It aggregates the positions on the recalibration dimension by party family, reinforcing our manifesto-based findings. Again, the liberal, green and more moderately conservative party families occupy the investment pole, social democratic parties lean towards consumption, but voters are less sure whether they would advance recalibration or preserve income-replacing schemes, and radical left parties are perceived even more strongly to prioritise consumptive policies than they present themselves in manifestos. Most importantly for our purposes, however, voters ascribe the consumption pole on the recalibration dimension to the RRP family.

Figure 4. Party positioning on recalibration dimension based on voters’ perception, aggregated by party family.

Figure A8 in the online appendix shows how party positions on the investment–consumption recalibration dimension are assessed on average in each of the six countries.Footnote15

Having compared the order of parties on the investment–consumption dimension, we find similarities between manifestos and perceptions of parties in at least some countries, such as the Netherlands and Germany; however, in other countries, such as Italy, they differ quite strongly. RRPs’ perceived prioritisation of consumptive over investing social policies remain remarkably consistent across countries. The German AFD, the Sweden Democrats, the Danish DPP and the Dutch PVV all occupy the most extreme position on the recalibration dimension in terms of their countries’ voters’ perspectives. Only the Italian Lega is placed merely second by voters with respect to their consumption profile, behind the Five Star Movement, which, strangely enough, has put a lot emphasis on education in particular in its manifesto but is, together with its former coalition-partner, apprehended as a force to defend the consumption-oriented focus of the Italian welfare state. The analysis of perceptions shows that despite differences in the size, historical origin, and institutional embeddedness of the party system, all RRPs under scrutiny are clearly seen as opposing the modernisation of the welfare state from consumption to social investment policies. This finding also holds if we exclude parties’ own voters’ evaluations (online appendix Figures A9 and A10) or only consider radical right voters (online appendix Figures A11 and A12). Thus, RRPs are perceived to occupy the consumption pole by both their own supporters and other parties’ voters.Footnote16

If we disaggregate the investment-consumption dimension into specific policy fields (see Figure A13 in the online appendix), we see that the perception of RRPs as supporters of consumption is strongly driven by them being perceived as fervent defenders of pensions. Moreover, an extraordinarily strong dislike of active labour market policies is attributed to the radical right. The other policies behave largely in line with our expectations except for unemployment benefits. Notwithstanding RRPs’ surprisingly strong emphasis on the expansion of unemployment benefits in their manifestos, the radical right is not perceived to be a particularly strong backer of passive labour market policies.Footnote17

Summarising, our result challenges the view that RRPs’ stances on economic and welfare issues are difficult for voters to grasp. This established view seems true concerning positioning on the preferred size of the welfare state. However, when it comes to the welfare state’s goals and operating principles, RRPs do not only communicate the most clearly, they are even perceived by the public as communicating, most unmistakeably, what kind of welfare state they do and do not want.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have argued that RRPs’ welfare state stances are more multi-faceted and clearer than previous research would assume. Our point ensues from the argument that the main conflict about welfare politics is no longer only about the size of the welfare state but also about what the welfare state should do (invest in human skills or substitute income). We propose, based on recent arguments from welfare state literature, that preferences on this second dimension of welfare politics (what we call recalibration) are structured differently than preferences about welfare state size and redistribution. As a result of that, parties have very different incentives for how to behave and position themselves within this recalibration dimension, leading to an entirely different conflict structure than one might expect on economic issues.

Our findings for seven West European countries show intriguing results for RRPs. While among all parties, RRPs speak the least about the welfare state in their electoral manifestos in a possible attempt to de-emphasise the issue, they state clearly which social policies they like the most or dislike the least, namely consumptive policies such as pensions. Not only do RRPs clearly state this priority, but despite remaining the most silent on welfare issues, voters seem to be aware of RRPs’ priorities and assess them correctly. This clear RRP positioning within the recalibration dimension does not come out of nowhere and is less surprising in light of voters’ attitudes. On the demand side, radical right voters constitute the clear pole that prioritises consumption over investment. Overall, we affirm the previous research findings that RRPs present blurry or moderate stances on the issue of the optimal welfare state size, presumably to neither alienate their more welfare-enthusiastic, working-class voters nor their more welfare-sceptical, middle-class constituencies. However, this current appreciation for RRPs as presenting centrist or even blurry welfare positions in the literature is only half the story.

The finding that radical right voters and RRPs have clear preferences and provide unambiguous, clearly discernible stances on whose needs the welfare state should cater to and how it should do so portends several implications. First, our finding contributes to party competition literature by implying that welfare issues’ salience in the political debate is not inevitably problematic for RRPs. Their strategic situation is less uncomfortable than previously assumed since their electorate has unclear preferences only regarding one welfare dimension but not the other. This becomes even more important in times of fiscal austerity. If the predominant conflict is not (only) about the generosity and size of the welfare state but also about which policies should be financed and which should not, then a high salience of welfare issues might harm social democratic parties that are bound to disappoint one part of their electorate after promising both investment to their new middle-class and consumption to their working-class constituency in electoral manifestos. In contrast, RRPs might capitalise on such a discourse by rallying consumption-oriented voters. This might also help to explain why the increased salience of welfare issues that has recently been observed during times of economic crises (Traber et al. Citation2018) has not harmed RRPs electorally as much as one could have expected.

Second, our findings call into question the prevalent opinion among researchers, that the (working-class) vote for the radical right is based exclusively on socio-cultural rather than economic motivations. Future research on determinants of radical right voting should not limit itself to conventional redistribution or welfare support questions when assessing the impact of economic preferences; rather, it should explore whether the clear positioning of RRPs on the recalibration dimension matters for the vote. The first commendable steps in this direction have recently been made, e.g. by Attewell (Citation2021).

Third, the clear positioning of RRPs on what kind of a welfare state they will pursue casts a different light on their role in welfare policy making, especially considering their government participation or their role of kingmaker in some countries. RRPs might therefore help the left expand or at least stabilise consumption policies such as pensions. At the same time, they can be expected to be the most formidable opposition to expanding social investment policies such as childcare or tertiary education. This points to an important role of the radical right in coalition formation that the welfare state literature should not neglect. Lastly, our paper corroborates and extends the expectation that Beramendi et al. (Citation2015) expressed with regard to the remarkable similarity between the conflict over social investment vs. consumption and what is often termed the second, non-economic dimension. There seems to be an overlap between not only demand side preferences but also the supply side conflict structure, with green and socially liberal parties at the universalist/social investment pole being opposed to RRPs at the particularistic/consumption pole and social democratic parties getting trapped in the middle.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.6 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the APSA Annual Meeting in August 2019 in Washington D.C., at the SPSA Annual Congress in February 2020 in Lucerne, at the ECPR General Conference in August 2020, as well as at the University of Zurich and at the European University Institute in Florence. We wish to thank the participants at these occasions for helpful comments. We are especially grateful for valuable input from Tarik Abou-Chadi, Macarena Ares, Robin Best, Paul Blokker, Reto Bürgisser, Marius Busemeyer, Silja Häusermann, Alexander Horn, Elif Kayran, Jelle Koedam, Sebastian Köhler, Jonathan Polk, Philip Rathgeb, Zeynep Somer-Topcu and the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthias Enggist

Matthias Enggist is a PhD researcher at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich. His research focuses on welfare state politics, public opinion, party competition and immigration. He has published in the European Journal of Political Research. [[email protected]]

Michael Pinggera

Michael Pinggera is a PhD researcher at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich. His research interests include welfare state politics, party competition and public opinion. He has published articles in the Journal of European Public Policy and Swiss Political Science Review. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The two dimensions we use to depict the welfare politics space strongly resemble previous conceptualisations of welfare state multidimensionality. For example, our welfare state size dimension relates to the ‘range’ and ‘degree’ dimensions postulated in Roosma et al. (Citation2013) while our recalibration dimension resembles their ‘goals of the state’ dimension which identifies social security, equality and social inclusion as potentially conflicting goals of the welfare state (see also Laenen et al. Citation2020 for a recent application).

2 We argue here that the possibility to target benefits to specific, more deserving groups makes the logic of consumption more appealing to radical right voters than the logic of social investment which usually combines procedural equality with the goal to increase recipients’ autonomy – irrespective of their deservingness. However, we acknowledge that, of course, recipient groups of different consumption and social investment policies also differ with regard to their attributed deservingness. For example, the elderly are perceived substantially more deserving than the unemployed (van Oorschot Citation2006) and policies directed at supporting elderly people should generally attract more support among radical right voters than policies supporting the unemployed (Busemeyer et al. Citation2021; Chueri Citation2020). Despite this not being the main epistemological interest of the paper, this leads us not only to expect the radical right to prioritise consumption over social investment but also to support some consumption policies more than others and some social investment policies more than others.

3 Figure A2 in the online appendix disaggregates the recalibration dimension by policy fields. It shows radical right voters to represent the clear pole of opposition in all three investment policies and to be the strongest supporters of pensions. Concerning unemployment benefits, radical right voters are located in the middle, prioritising them less strongly than radical left voters but significantly more than voters of centre-right parties. This exception might reflect the lower deservingness of the unemployed. However, the fact that radical right voters clearly prefer unemployment benefits over active labour market policies (which are also directed at the unemployed) supports our expectation that the logic of consumption is more appealing to radical right voters than the logic of investment.

4 See online appendix A3 for a substantive overview of parties and manifestos included and online appendix A4 for detailed information on the country selection.

5 We acknowledge that healthcare may also be classified as a social investment policy (Schwander Citation2019), depending on both the definition of social investment and the design of specific health policies (Garritzmann et al. Citation2017: 21–2). But it is also considered a traditional element of the welfare state (Bonoli Citation2005: 445) for which the politics differ (Garritzmann, Busemeyer et al. Citation2018). However, the overall pattern of our results does not change once we exclude healthcare.

6 This includes Welfare State Expansion (per504), Welfare State Limitation (per505), Education Expansion (per506), Education Limitation (per507), Centralisation: Positive (per302), Corporatism/Mixed Economy (per405), Technology and Infrastructure (per411), Equality: Positive (per503), Traditional Morality: Positive (per603), Traditional Morality: Negative (per 604), and Labour Groups: Positive (per701).

7 We limit ourselves to positive sentiments, i.e. statements implying or demanding welfare state expansion, since claims to retrench the welfare state feature only very rarely in election manifestos. On average, less than 6% of all social policy statements refer to retrenchment.

8 The findings do not change when calculating the recalibration profile with positive statements only, as reported in online appendix A5.

9 Note that the number of social policy statements is only marginally correlated (r = −0.14) with the recalibration score’s absolute difference from 50%, meaning that the measure is not affected by how much a party says.

10 In which of the following areas do you think the [party X] would prioritise improvements of social benefits? You can allocate 100 points. Give more points to those areas in which you think the [party X] would prioritise improvements and fewer points to those areas where you think the [party X] would deem improvements less important: A) Old age pensions, B) Childcare, C) University education, D) Unemployment benefits, E) Labour market reintegration services, F) Services for the social and labour market integration of immigrants. F) Was omitted for the analyses. Voters evaluated their own party as well as another randomly selected party.

11 Weighted by age, gender, education, and vote choice in the last election. To exclude the politically unsophisticated, we restrict ourselves to voters’ evaluations. Doing so does not change the findings.

12 The number of perceptions by party varies substantially between countries (from an average of 373 per party in the Netherlands to 790 in the United Kingdom, depending on the number of relevant parties) but to a lesser degree within countries.

13 Note that FDI have been classified as a conservative party, following both the Comparative Manifesto Project and the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. However, there are valid arguments for a classification of FDI as a RRP (the 2017 Chapel Hill Survey newly considers them 'radical'). Our findings are however robust, irrespective of what family we assign them. Nonetheless, finding them at the social investment pole of the recalibration dimension is surprising. It is a result of their particularly strong emphasis on educational matters in the analysed 2013 manifesto. This result however is not replicated in the 2018 manifesto (see A3 for more information on why we included the 2013 manifesto).

14 This analysis includes Denmark but lacks observations for Austria and Norway since individual-level data are not available.

15 Note that not all parties whose manifestos we have coded were presented to voters for evaluation. Most notably, we lack UKIP evaluations because the party sank into near insignificance before we conducted our survey in the autumn of 2018.

16 This alleviates potential concerns that our findings are solely driven by radical right voters who evaluate their party’s position in accordance with their own consumption-oriented preferences.

17 Although significantly more than both conservative and liberal parties.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Ellen M. Immergut (2019). ‘Recalibrating Social Protection: Electoral Competition and the New Partisan Politics of the Welfare State’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:2, 697–719.

- Afonso, Alexandre (2015). ‘Choosing Whom to Betray: Populist Right-Wing Parties, Welfare State Reforms and the Trade-off between Office and Votes’, European Political Science Review, 7:2, 271–92.

- Afonso, Alexandre, and Line Rennwald (2018). ‘Social Class and the Changing Welfare State Agenda of Radical Right Parties in Europe’, in Philip Manow, Bruno Palier, and Hanna Schwander (eds.), Welfare Democracies and Party Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 171–96.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Nathalie Giger (2008). ‘Conditional Punishment: A Comparative Analysis of the Electoral Consequences of Welfare State Retrenchment in OECD Nations, 1980–2003’, West European Politics, 31:3, 558–80.

- Attewell, David (2021). ‘Deservingness Perceptions, Welfare State Support and Vote Choice in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 44:3, 611–34.

- Bélanger, Eric, and Kees Aarts (2006). ‘Explaining the Rise of the LPF: Issues, Discontent, and the 2002 Dutch Election’, Acta Politica, 41:1, 4–20.

- Beramendi, Pablo, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2015). The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bonoli, Giuliano (2005). ‘The Politics of the New Social Policies: Providing Coverage against New Social Risks in Mature Welfare States’, Policy & Politics, 33:3, 431–49.

- Bonoli, Giuliano, and Fabienne Liechti (2018). ‘Good Intentions and Matthew Effects: Access Biases in Participation in Active Labour Market Policies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:6, 894–911.

- Bornschier, Simon (2010). Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bremer, Björn, and Reto Bürgisser (2020). ‘Public Opinion on Welfare State Recalibration in Times of Austerity: Evidence from Survey Experiments’, SocArXiv. doi:https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/uj6eq.

- Busemeyer, Marius R., and Julian L. Garritzmann (2017). ‘Public Opinion on Policy and Budgetary Trade-Offs in European Welfare States: Evidence from a New Comparative Survey’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:6, 871–89.

- Busemeyer, Marius R., Philip Rathgeb, and Alexander H. J. Sahm (2021). ‘Authoritarian Values and the Welfare State: The Social Policy Preferences of Radical Right Voters’, West European Politics, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1886497.

- Chueri, Juliana (2020). ‘Social Policy Outcomes of Government Participation by Radical Right Parties’, Party Politics.

- de Lange, Sarah L. (2007). ‘A New Winning Formula?: The Programmatic Appeal of the Radical Right’, Party Politics, 13:4, 411–35.

- de Lange, Sarah L. (2012). ‘New Alliances: Why Mainstream Parties Govern with Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties’, Political Studies, 60:4, 899–918.

- Eger, Maureen A., and Sarah Valdez (2015). ‘Neo-Nationalism in Western Europe’, European Sociological Review, 31:1, 115–30.

- Eger, Maureen A., and Sarah Valdez (2019). ‘From Radical Right to Neo-Nationalist’, European Political Science, 18:3, 379–99.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2018). ‘Welfare Chauvinism in Populist Radical Right Platforms: The Role of Redistributive Justice Principles’, Social Policy & Administration, 52:1, 293–314.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta, Duncan Gallie, Anton Hemerijck, and John Myles (2002). Why We Need a New Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fenger, Menno (2018). ‘The Social Policy Agendas of Populist Radical Right Parties in Comparative Perspective’, Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 34:3, 188–209.

- Fossati, Flavia, and Silja Häusermann (2014). ‘Social Policy Preferences and Party Choice in the 2011 Swiss Elections’, Swiss Political Science Review, 20:4, 590–611.

- Garritzmann, Julian L., Marius R. Busemeyer, and Erik Neimanns (2018). ‘Public Demand for Social Investment: New Supporting Coalitions for Welfare State Reform in Western Europe?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:6, 844–61.

- Garritzmann, Julian L., Silja Häusermann, Bruno Palier, and Christine Zollinger (2017, March). ‘WoPSI – The World Politics of Social Investment: An International Research Project to Explain Variance in Social Investment Agendas and Social Investment Reforms across Countries and World Regions’, LIEPP Working Paper, n° 64.

- Garritzmann, Julian L., Erik Neimanns, and Marius R. Busemeyer (2018). ‘Trust, Public Opinion, and Welfare State Reform’, Manuscript.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Carsten Jensen (2019). ‘Electoral Competition and the Welfare State’, West European Politics, 42:4, 803–23.

- Gingrich, Jane, and Silja Häusermann (2015). ‘The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State’, Journal of European Social Policy, 25:1, 50–75.

- Häusermann, Silja (2010). The Politics of Welfare State Reform in Continental Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Häusermann, Silja, Matthias Enggist, Macarena Ares, and Michael Pinggera (2019). ‘Fiscal Austerity Perceptions and How They Depress Solidarity’, Manuscript.

- Häusermann, Silja, Thomas Kurer, and Hanna Schwander (2015). ‘High-Skilled Outsiders? Labor Market Vulnerability, Education and Welfare State Preferences’, Socio-Economic Review, 13:2, 235–58.

- Häusermann, Silja, Thomas Kurer, and Denise Traber (2019). ‘The Politics of Trade-Offs: Studying the Dynamics of Welfare State Reforms with Conjoint Experiments’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:7, 1059–95.

- Häusermann, Silja, Michael Pinggera, Macarena Ares, and Matthias Enggist (2020). ‘The Limits of Solidarity. Changing Welfare Coalitions in a Transforming European Party System’, Manuscript.

- Häusermann, Silja, Macarena Ares, Matthias Enggist, and Michael Pinggera (2020). ‘Mass Public Attitudes on Social Policy Priorities and Reforms in Western Europe. WELFAREPRIORITIES Dataset 2020’, Welfarepriorities Working Paper Series, n°1/20.

- Häusermann, Silja, Michael Pinggera, Macarena Ares, and Matthias Enggist (2021). ‘Class and Social Policy in the Knowledge Economy’, Manuscript.

- Hemerijck, Anton (2013). Changing Welfare States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine E. de Vries (2015). ‘Issue Entrepreneurship and Multiparty Competition’, Comparative Political Studies, 48:9, 1159–85.

- Horn, Alexander, Anthony Kevins, Carsten Jensen, and Kees van Kersbergen (2017). ‘Peeping at the Corpus – What Is Really Going on behind the Equality and Welfare Items of the Manifesto Project’, Journal of European Social Policy, 27:5, 403–16.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2005). ‘The Vulnerable Populist Right Parties: No Economic Realignment Fuelling Their Electoral Success’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:3, 465–92.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2008). ‘What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:1, 3–23.

- Jacobs, Alan M., and J. Scott Matthews (2017). ‘Policy Attitudes in Institutional Context: Rules, Uncertainty, and the Mass Politics of Public Investment’, American Journal of Political Science, 61:1, 194–207.

- Jensen, Carsten (2014). The Right and the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jønsson, Heidi Vad, and Klaus Petersen (2012). ‘Denmark: A National Welfare State Meets the World’, in Grete Brochmann and Anniken Hagelund (eds.), Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945 − 2010. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 123–42.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (1994). The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (2004). ‘Diversification and Reconfiguration of Party Systems in Postindustrial Democracies’, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Europäische Politik, 03, 1–23.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Anthony J. McGann (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Koedam, Jelle (2020). ‘Avoidance, Ambiguity, Alternation Position Blurring Strategies in Multidimensional Party Competition’, Manuscript.

- Kölln, Ann-Kristin, and Christopher Wlezien (2016). ‘Conjoint Experiments on Political Support for Governmental Spending Profiles’, Working Paper presented at EPOP in Kent.

- Krause, Werner, Pola Lehmann, Jirka Lewandowski, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Annika Werner (2019). Manifesto Corpus. Version: 2019-2. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, et al. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuisma, Mikko, and Mikael Nygard (2019). ‘The Nordic Model of Welfare Chauvinism? Populist Welfare Discourses in Finland and Sweden’, Manuscript.

- Laenen, Tijs, Bart Meuleman, and Wim van Oorschot (2020). Welfare State Legitimacy in Times of Crisis and Austerity. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lefkofridi, Zoe, and Elie Michel (2014). Exclusive Solidarity? Radical Right Parties and the Welfare State. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- Morel, Nathalie, Bruno Palier, and Joakim Palme (2012). Towards a Social Investment Welfare State? Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Mudde, Cas (1999). ‘The Single-Issue Party Thesis: Extreme Right Parties and the Immigration Issue’, West European Politics, 22:3, 182–97.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nordensvard, Johan, and Markus Ketola (2015). ‘Nationalist Reframing of the Finnish and Swedish Welfare States – the Nexus of Nationalism and Social Policy in Far-Right Populist Parties’, Social Policy & Administration, 49:3, 356–75.

- Oesch, Daniel (2008). ‘The Changing Shape of Class Voting’, European Societies, 10:3, 329–55.

- Oesch, Daniel, and Line Rennwald (2018). ‘Electoral Competition in Europe‘s New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre-Right and Radical Right’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 783–807.

- Otjes, Simon, Gilles Ivaldi, Anders Ravik Jupskås, and Oscar Mazzoleni (2018). ‘It’s Not Economic Interventionism, Stupid! Reassessing the Political Economy of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties’, Swiss Political Science Review, 24:3, 270–90.

- Pavolini, Emmanuele, and Wim Van Lancker (2018). ‘The Matthew Effect in Childcare Use: A Matter of Policies or Preferences?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:6, 878–93.

- Pierson, Paul (2001). The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rathgeb, Philip (2021). ‘Makers against Takers: The Socio-Economic Ideology and Policy of the Austrian Freedom Party’, West European Politics, 44:3, 635–60.

- Roosma, Femke, John Gelissen, and Wim van Oorschot (2013). ‘The Multidimensionality of Welfare State Attitudes: A European Cross-National Study’, Social Indicators Research, 113:1, 235–55.

- Röth, Leonce, Alexandre Afonso, and Dennis C. Spies (2018). ‘The Impact of Populist Radical Right Parties on Socio-Economic Policies’, European Political Science Review, 10:3, 325–50.

- Rovny, Jan (2012). ‘Who Emphasizes and Who Blurs? Party Strategies in Multidimensional Competition’, European Union Politics, 13:2, 269–92.

- Rovny, Jan (2013). ‘Where Do Radical Right Parties Stand? Position Blurring in Multidimensional Competition’, European Political Science Review, 5:1, 1–26.

- Rovny, Jan, and Jonathan Polk (2020). ‘Still Blurry? Economic Salience, Position and Voting for Radical Right Parties in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 248–68.

- Rydgren, Jens (2012). Class Politics and the Radical Right. London: Routledge.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Kees van Kersbergen (2016). ‘Do Mainstream Parties Adapt to the Welfare Chauvinism of Populist Parties?’, Party Politics, 22:3, 300–12.

- Schwander, Hanna (2019). ‘VII. Healthcare as Social Investment’, in The Hertie School of Governance, The Governance Report 2019. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 121–34.

- Söderlund, Peter, and Elina Kestilä‐Kekkonen (2009). ‘Dark Side of Party Identification? An Empirical Study of Political Trust among Radical Right‐Wing Voters’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 19:2, 159–81.

- Stephens, John D., Evelyne Huber, and Leonard Ray (1999). ‘The Welfare State in Hard Times’, in Herbert Kitschelt, Peter Lange, Gary Marks, and John D. Stephens (eds.), Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 164–93.

- Svallfors, Stefan (1997). ‘Worlds of Welfare and Attitudes to Redistribution: A Comparison of Eight Western Nations’, European Sociological Review, 13:3, 283–304.

- Svallfors, Stefan (2007). The Political Sociology of the Welfare State: Institutions, Social Cleavages, and Orientations. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Traber, Denise, Nathalie Giger, and Silja Häusermann (2018). ‘How Economic Crises Affect Political Representation: Declining Party‒Voter Congruence in Times of Constrained Government’, West European Politics, 41:5, 1100–24.

- van Oorschot, Wim (2006). ‘Making the difference in social Europe: deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states’, Journal of European Social Policy, 16:1, 23–42.

- van Oorschot, Wim, and Bart Meuleman (2012). ‘Welfarism and the Multidimensionality of Welfare State Legitimacy: Evidence from The Netherlands, 2006’, International Journal of Social Welfare, 21:1, 79–93.