?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The ability of Members of Parliament (MPs) to know the policy preferences of their party voters is a precondition for substantive representation. This study investigates whether MPs’ perceptions of their party voters’ opinions are more accurate with policy statements on which they are competent—namely, those that are owned by their party and in which the MPs have specialised. It combines unique data from citizen surveys and face-to-face meetings with 367 MPs in Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland. Both citizens and MPs evaluated the same statements, and MPs also estimated the support for each statement among their party voters. The comparison of party voters’ preferences and MPs’ estimations shows that MPs are more accurate on statements owned by their party, but not on issues they themselves specialise in through committee membership. Party issue ownership plays an important role in determining MPs’ perceptual accuracy and, hence, democratic representation.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1940647 .

Political representation as a delegation and accountability mechanism refers to a relationship between a representative, i.e. an elected member of parliament (MP), and those whom they represent, i.e. their party electorate (Dahl Citation1971; Pitkin Citation1967). The concepts of policy congruence (Lax and Phillips Citation2012: 148) and policy responsiveness (Stimson et al. Citation1995: 548) focus on this MP-electorate linkage and assess whether political elites act according to voters’ policy preferences (Andeweg Citation2014). Although the accuracy of MPs’ perceptions of the electorate’s preferences is key to understanding policy congruence and responsiveness (Esaiasson and Wlezien Citation2017: 702; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010) and, furthermore, to evaluating the quality of representative democracy (Miller and Stokes Citation1963), scholars have paid surprisingly little attention to MPs’ ability to assess accurately voters’ wishes.

Only a few studies inspired by the seminal article of Miller and Stokes (Citation1963) have directly asked political elites about their perceptions of voters’ preferences (Belchior Citation2014; Broockman and Skovron Citation2018; Clausen Citation1977; Converse and Pierce Citation1986; Grandberg Citation1985; Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972; Holmberg Citation1999; Kalla and Porter Citation2020). They show that MPs’ perceptions of the electorate’s opinion are generally not very accurate. This misperception might be due to ‘wishful thinking’, with MPs tending to project their own opinions onto voters (Holmberg Citation1999), to ideological orientation (Belchior Citation2014), to selective information sources such as vocal citizens and interest groups (Broockman and Skovron Citation2018; Pereira Citation2021; see also Hertel-Fernandez et al. Citation2019 for a similar finding about the biased misperceptions of US Congressional staffers), or to the MPs’ low receptivity of factual information about constituents’ preferences (Kalla and Porter Citation2020). However, MPs’ estimates become more accurate when voters have homogeneous preferences on the policy issue at stake (Clausen et al. Citation1983) and when this issue is salient or ‘politically charged’ (Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972).

This article aims to contribute to the emerging literature on MPs’ perceptual accuracy and to explain differences in accuracy level among elected MPs when they are asked to estimate the policy position of their party voters. It investigates whether ‘issue ownership’ on the party level and policy specialisation on the individual MP level enhance MPs’ knowledge of the opinion of their party voters. We expect that MPs who are dealing with a policy issue that their party owns, who are appointed in the parliamentary committees handling the issue at stake and who consider themselves specialised on the issue should be, all other things being equal, better at knowing what their party voters think about the issue.

In order to assess this question empirically, we draw on a unique comparative dataset with 367 MPs from four countries with varying political systems (Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland). In each country, we fielded two surveys: a survey among MPs conducted in face-to-face meetings and an online survey among citizens. To assess MPs’ perceptual accuracy, we ask MPs to estimate the percentage of party voters who agree with each of a large set of policy statements. These statements cover a wide range of salient issues, such as immigration, the environment, redistribution, defense or pensions. By comparing MPs’ estimations of each policy statement to the data from the citizen survey, we obtain a measure for the MPs’ ability to estimate their party voters’ preferences. We then investigate the role that party issue ownership, committee membership and self-reported specialisation play in MPs’ perceptions of their party voters’ opinion.

The results show that party issue ownership is positively associated with MPs’ perceptual accuracy. On statements their party owns, MPs are more accurate in their estimation of the opinion of their party electorate. However, individual issue specialisation through membership in the relevant legislative committee does not enhance MPs’ perceptual accuracy. Furthermore, MPs who self-report that they are specialists in a policy domain do not make more accurate estimations about the preferences of their party voters as compared to MPs who do not see themselves as specialists. These consistent findings across four different political systems suggest that party competition around issue ownership is conducive to MPs’ perceptual accuracy, which is a precondition for substantive representation.

Theoretical framework

Legislative representation can come about through different paths (Miller and Stokes Citation1963). Elections are one aspect of this relationship, with voters electing those representatives or parties they agree with and voting out of office those who take actions that contradict the voters’ own wishes (Manin et al. Citation1999). However, elections take place only every few years, which leaves ample time for new issues to emerge on the political agenda, or for a focussing event (e.g. an economic crisis or a pandemic) to suddenly change the general situation in a country. Empirical studies also show that citizens highly value MPs’ responsiveness (Bowler Citation2017; Rosset et al. Citation2017). It is therefore crucial for political representation that MPs know and respond to the party voters’ wishes in between elections (Mansbridge Citation2003). However, the precondition for this mechanism of representation to work is that MPs know what their party voters want.

Studies show that MPs’ perceptions of voters’ opinions are not very accurate. Some politicians are better equipped to know what their voters want than others, for example, depending on their understanding of their role as delegates or trustees (Erikson et al. Citation1975; Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972). Moreover, there are systematic differences between parties (Belchior Citation2014; Broockman and Skovron Citation2018). However, no study to date has investigated the role of MPs’ and parties’ issue competence on perceptual accuracy, despite its centrality in broader research on political representation, voting, and legislative organisation. Our theoretical framework elaborates on these two dimensions of issue competence.

Party level: competence issue ownership

Issue ownership is a multidimensional concept that encompasses both an associative dimension, i.e. voters believe that a party cares most about a given issue, and a competence dimension, i.e. voters believe that a party is best able to handle this issue (Walgrave et al. Citation2012, Citation2015). Studies focussing on the impact of issue ownership on voters’ electoral behaviour underline its importance in explaining why voters choose one party over another (Bellucci Citation2006; Green and Jennings Citation2012). Attributing issue competence to a party has a positive effect on voters’ evaluation of party utility and also tends to reduce voter-party distance (Lachat Citation2014). Furthermore, the probability of voting for a party that is considered as having the best solutions on a specific issue increases if voters perceive this issue as salient (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008).

Scholars have also used issue ownership to explain the electoral strategies of parties competing for political mandates, showing that, during electoral campaigns, parties privilege the issues in which they have a strong reputation (e.g. Budge and Farlie Citation1983; Dolezal et al. Citation2014; Petrocik Citation1996; Petrocik et al. Citation2003). In the present study, we capitalise on this ownership-based voting literature and consider issue ownership at the party level as a determinant of MPs’ perceptual accuracy.

This expectation is embedded in the conceptualisation of parties as vote- and office-seeking actors (Fenno Citation1973; Strøm Citation1990). They aim to increase their chances of re-election by sending clear signals to their party voters, precisely on those policy issues on which they have a reputation of competence. While parties certainly also want to convince and attract new potential voters, they have strong incentives to not alienate their core voters. Thus, they must closely monitor what their party voters want on those issues, as this allows them to better calibrate and frame the policy solutions they advocate. As a consequence, parties invest in handling the core of their policy portfolio and closely monitor the opinion of their party voters through targeted polls, regional caucuses, or direct contacts with party voters. Deployment of these additional resources eventually translates into a high level of information and, consequently, perceptual accuracy among the party’s MPs.

At the same time, ‘a certain degree of positional agreement is likely to be a precondition for voters to attribute competence ownership of an issue’ (Lachat Citation2014: 729–30). Issue ownership indicates which issues the party voters consider as salient and, furthermore, suggests some homogeneity in the party leaders’ and voters’ positions. Indeed, a party strategically emphasises the policy issues on which it has an ‘outlying position’, and de-emphasises and blurs its positions on issues it doesn’t own (Rovny Citation2012: 273). Voters who choose a party are obviously likely to share its position on an issue that lies at the core of the party identity and, as a result, party voters will have rather homogeneous preferences regarding the issue at stake. The homogeneity of party voters’ preferences and the issue saliency make it easier for MPs to have high perceptual accuracy on the issues that their party owns, as suggested by previous studies investigating perceptual accuracy (Clausen et al. Citation1983; Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972). In sum, we expect that MPs have a higher perceptual accuracy on issues owned by their party than on issues not owned by their party (H1).

However, party issue ownership is just one aspect related to competence. Empirical evidence shows that parties often compete on similar issues that dominate the (multi)party system within a country (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2010; Dolezal et al. Citation2014). Such an ‘issue convergence’ blurs the lines and sometimes makes it difficult for voters to clearly identify which party is considered to have the best solution for specific issues (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008: 482; Lachat Citation2014: 734). More importantly, individual MPs are not all active on the few issues in which their party has built a strong reputation of competence. Within the party, MPs specialise in specific issues to distinguish themselves from competitors within the party and to build their own profile towards party voters (Peeters et al. Citation2019). Thus, to capture competence, there is a need to also consider issue specialisation at the level of individual MPs.

Individual MP level: issue specialisation

Issue specialisation of MPs has been an important aspect of studying MPs’ behaviour for decades. Applying a motivational approach to the parliamentary roles, Searing (Citation1987) identifies policy specialists as those MPs who select a few issues and aim to influence policy-making in these specific domains. To gather information about their topics of specialisation, ‘specialists seek current and first-hand knowledge which comes from contact with organisations and individuals outside parliament. The specialist attends many outside functions because (…) he wants to have plenty of contacts outside so he can know what they think’ (Searing Citation1987: 439). In contrast to generalist MPs who do not devote too much time to constituency work (Searing Citation1987: 437), issue specialists constantly care about the opinion and policy preferences of their party voters. They keep in touch with citizens and interest organisations active on the ground and do not rely only on information-sharing among peers (Searing Citation1987: 441). As issue specialists make use of a more diverse set of information sources on ‘their’ issue than do MPs who do not specialise in that same issue, it is likely that specialists have a higher perceptual accuracy.

In a recent study on Belgian MPs, Peeters and colleagues (2019) indeed demonstrated that issue specialists invest more time and resources than other MPs to get information about their issues of specialisation. In doing so, they signal their individual expertise to party colleagues, the media, and party voters, for instance, through targeted parliamentary interventions (e.g. questions and legislative statements) and communication activities (e.g. media articles and tweets). Becoming members of the relevant intra-party committee also allows MPs to develop a reputation within their own party (Peeters et al. Citation2019; Saalfeld and Strøm Citation2014: 376–7; Searing Citation1987).

Within parties, the position of issue specialists is also closely linked to being appointed as party representatives in the relevant parliamentary legislative committees (Andeweg and Thomassen Citation2011; Mattson and Strøm Citation1995). Access to this institutional venue is crucial to framing policy problems and designing policy solutions. Claiming credit for a new policy also increases the MP’s power within the Chamber and contributes to the MP’s re-election goal (Fenno Citation1973). Furthermore, membership in a permanent legislative committee reinforces the specialisation of MPs. According to the informational theory of legislative organisation (Gilligan and Krehbiel Citation1987; Martin and Mickler Citation2019; Searing Citation1987; Strøm Citation1998), committee members acquire technical expertise and efficiently process information about citizens preferences related to the issues handled within the committee.

In addition, issue specialists must negotiate policy compromise with committee members from other parties and, in a multiparty system, scrutinise potential drift from the government agreement by coalition partners (Martin and Vanberg Citation2011). They regularly confront divergent opinions and are probably less affected by a motivated reasoning bias (Belchior Citation2014; Broockman and Skovron Citation2018). They should thus be able to more accurately judge their party voters’ opinions related to the issues that their legislative committee addresses.

In sum, issue specialists seated in relevant committees have privileged access to insider information (e.g. preparatory reports from independent experts, hearings with policy stakeholders, contacts with lobbyists from the domain, etc.) and consult more policy actors outside the parliamentary venue, including party voters. Accordingly, we expect that MPs have a higher perceptual accuracy on issues handled in the legislative committees they are member of than on issues handled in committees of which they are not a member (H2).

It is worth noting that not all MPs who deem themselves issue specialists can be appointed as party representatives in the relevant legislative committees. Indeed, MPs might have an educational background, a (previous) professional occupation, or (in)formal contacts with interest organisations that are highly relevant for a specific issue. Due to these individual characteristics and relational ties, MPs might consider themselves issue specialists even if they do not belong to the relevant legislative committee or intra-party committee (Tresch Citation2009). For example, MPs who were educated as medical physicians will probably think that they are highly specialised and will be interested in health-care policy. They understand the policy problem to be addressed (e.g. changes to the organ donation system, as we asked about in Germany, or decriminalisation of euthanasia, as we asked about in Canada); they have frequent contacts with patients and colleagues; and they participate in debates within professional organisations (e.g. National Medical Doctors Association). To gain prestige, power, and status within the party on this specific issue (for instance, by becoming the next party representative in the relevant legislative committee) MPs who self-report as being specialised in a specific issue will also engage in the related party-internal debates. Thereby, they will acquire a clear view of party leaders’ position and voters’ opinion as well. Consequently, we expect that MPs have a higher perceptual accuracy on issues they self-reported to be specialised in than on issues they are not specialised in (H3).

Method and data

In order to investigate empirically the role of these competence dimensions on how accurately MPs perceive party voters’ opinion, we compare the MPs’ estimation of party voters’ opinion—in four different political systems and in multiple policy domains—to data on actual party voters’ opinion collected via a survey. To date, studies of MPs’ perceptual accuracy have either focussed on party voters (e.g. Belchior Citation2014 in Portugal; Clausen et al. Citation1983 in Sweden) or asked MPs to estimate the opinion in their electoral district (e.g. Broockman and Skovron Citation2018; Miller and Stokes Citation1963). Owing to the multiparty systems to which the majority of our four countries belong, we focus here on MPs’ perceptions of the opinion of the voters of their party (Online Appendix A details how ethical approval was obtained for the study).

The four countriesFootnote1 we cover—Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland—show important variations in Western political systems. They range from non-parliamentary systems with relatively weak parties, like Switzerland, to parliamentary systems with strong parties, with Belgium being an emblematic example of a ‘partitocracy’. The electoral rules vary too across countries (e.g. first-past-the-post in Canada, proportional system in Switzerland, and mixed system in the German Bundestag). Moreover, the autonomy of parliamentary committees varies considerably across the four countries, ranging from a low level of autonomy in Canada to the, in international comparison, highest autonomy scores in Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland (Mickler Citation2017). These substantial variations in institutional rules and party systems might influence the role of certain competence measures over others, i.e. committee specialisation versus party issue ownership and the MPs’ focus of representation, i.e. the groups in society that MPs claim to represent (Dudzińska et al. Citation2014). Previous studies have shown that institutional variables condition the relationships between public opinion and policy. For instance, both federalism and a proportional electoral system seem to constrain policy representativeness (Wlezien and Soroka Citation2012). In line with this scholarship, we also assume that institutional factors may have a potential impact on the attention that MPs dedicate to party voters’ preferences and, thereby, their level of perceptual accuracy. Finding consistent empirical results across different political systems will thus speak to the external validity of our study.

In addition, this study covers a diverse set of policy domains to measure perceptual accuracy. Since the pioneer study of Miller and Stokes in 1963, studies to date have focussed mostly on a very limited range of (the most salient and contested) issues such as abortion or gun control (e.g. Broockman and Skovron Citation2018). However, including a wide variety of issues for different parties and MPs is, in fact, a prerequisite for studying the role of issue competence. The policy statements selected in the present study display varying levels of saliency (Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972) and public opinion distribution (Clausen et al. Citation1983), which have also been found to play a role in predicting MPs’ perceptual accuracy. In each country, specific and timely statements on eight or nine issues were used. Overall, we include 50 statements across the four countries (listed in Online Appendix C).

Citizen and MP surveys

In order to gauge politicians’ perceptual accuracy of their party voters’ opinion, we combine information about actual voters’ opinion from a representative survey of the population with the estimations of their opinion by active MPs.Footnote2

The politician survey was conducted among elected MPs at the national level by the respective country teams. All countries used the same general approach to contact politicians for the face-to-face meetings: following personal invitation letters, a principal investigator contacted the politician via phone to schedule appointments. Meetings usually took about 45 min, with the survey taking approximately 30 min to complete (filled out on a tablet or a laptop computer by the politicians themselves).

We base our analyses on the responses of 367 MPs, although the cooperation rates and observations vary across the countries studied (see ). These differences underline the additional challenge the size of the country and parliament provide for data collection with these elite. Overall, cooperating MPs are representative of their parliament across countries (see Online Appendix A). For the present analyses, some cooperating MPs had to be excluded because of missings (n = 21, Online Appendix A for details) or because we did not have reliable estimates about their party voters’ opinion from the citizen survey, as we explain below (n = 6).

Table 1. Number of MPs who participated in the study and N for analyses per country.

In order to collect information about the opinion of party voters, in parallel or shortly before/after holding the interviews with the MPs, a survey with the exact same statements as the politician survey was conducted among the country’s population. Overall, responses from more than 10,000 citizens across the four countries were collected. The Belgian data were collected in Flanders and francophone Belgium (Wallonia and Brussels) in web-based surveys by SSI with quotas on age, gender and education during two weeks at the end of February 2018, resulting in n = 2,389 (Flanders) and n = 2,380 (Wallonia/Brussels), respectively. In Canada, Qualtrics collected the data in nine-day data collection from June 18, 2018 (n = 895) and applying quotas on age, gender, population proportion in each province, and first language with 20–25% French speaking. The German data were collected by YouGov during October 2018 (n = 1,520) installing quotas on age, gender, region, education and partisanship (i.e. vote in the 2017 federal elections). Finally, in Switzerland, a representative probability sample of 10,268 citizens was contacted by mail with an access code to the online survey between June and August 2018. The response rate, including the answers to the second reminder with a paper version of the survey, was 46 per cent (n = 4,677). Information about the representativity of the samples in Online Appendix A.

To identify party voters and estimate their support for a specific policy statement, we asked respondents to indicate the party for which they had voted in the most recent general elections. In some countries, the most recent elections had been held several years ago (e.g. 2014 in Belgium and 2015 in Canada and Switzerland). Thus, for respondents who indicated that they did not remember which party they had voted for or would not say, we took the party they indicated that they would vote for if elections were held today. We define a threshold of 40 party voters per statement per party to estimate the opinion of the party voters. The exact numbers of observations per country for each party’s voters and a replication of the results applying a threshold of 100 voters in Online Appendix B.

Dependent variable: MPs’ perceptual accuracy at the statement level

Perceptual accuracy is conceptualised as the difference between the estimated percentage of the party voters at the national level whom an MP thinks agree with a specific statement and the actual percentage of the party voters agreeing, as measured through our population survey. To measure the position of party voters, we simply asked citizens to indicate their position on a 5-point scale for each of the policy statements: absolutely disagree, rather disagree, rather agree, fully agree, and one option labelled as ‘undecided (neutral or no opinion)’. For each policy statement, we then aggregated those absolutely or rather agreeing per party to obtain a score for the percentage of party voters who absolutely or rather agree with the statement.

In the MP survey, we asked politicians to estimate, for each of the policy statements, (a) the percentage of their party voters who are undecided (neutral or no opinion) on the policy statement and (b) the percentage who fully or rather agree. We use the answers to the latter question to construct our measure of perceptual accuracy (PA) per policy statement per MP as follows:

where agree_elect is the percentage of respondents among the MPs’ party voters who rather and absolutely agree with the policy statement and agree_est is the percentage of party voters whom the MP estimates agree with the statement.

The majority of studies in the field have used this approach to operationalise perceptual accuracy (e.g. Belchior Citation2014; Broockman and Skovron Citation2018; Converse and Pierce Citation1986; Kalla and Porter Citation2020; Sigel and Friesema Citation1965). The mean perceptual accuracy is 80.0 per cent (SD = 16.54) with remarkable similarities across the four countries we studied, ranging from 77.6 per cent in Germany to 82.3 per cent in Canada.

When looking at these (apparently) high levels of perceptual accuracy, we should not forget the effect of chance and, thus, ask whether MPs are able to make estimations that are better than random. Indeed, if party voters’ opinion is perfectly divided on each of the policy statement MPs had to estimate (50% of voters agreeing vs. 50% disagreeing), then the maximum mean absolute error a MP can make is 50 and random answers will generate a 25 mean error. When party voters’ opinion leans to one side, the maximum error on the minority side becomes bigger than 50%, but this is compensated by a smaller maximum error on the majority side. Even then, randomly estimating voters’ opinion produces a mean error of 25. Turned upside down, a random rater would have a perceptual accuracy score of 75 (Sevenans et al. Citation2021, Walgrave et al. Citation2021). This benchmark should be kept in mind when judging the MPs’ accuracy scores and, furthermore, when discussing the impact of party issues ownership and MPs’ specialisation on perceptual accuracy.

Because each responding MP estimated their party voters’ opinion on eight or nine policy statements, our data are nested; statements in MPs and MPs in parties. To account for the relationships in the data, we use multilevel linear regression models with random intercepts at the MP and party levels. In comparative models, country-level variation is taken into account with a country dummy. In sum, we base our estimations on 3,019 policy statements from 367 politicians from 28 different parties (see for observations per country).

Issue competence measures: party issue ownership and MPs’ specialisation

We operationalise our main independent variable, issue competence, in three dimensions. This first one is via party issue ownership, the party MPs in a parliament consider the most competent on a specific statement. Two country experts independently coded each statement. If the expert coders could not identify a clear issue owner, we asked them to not mention a party and proceeded alike if they could not agree on a clear issue owner. For each MP-statement dyad, we identify whether the MP’s party holds issue ownership (1) or not (0). Across the MP-statement dyads, for 20.4 per cent (n = 616), there is party issue ownership, illustrating the variation in our data. As a robustness check, we also operationalised party issue ownership as a continuous variable on a sub-set of statements in the Swiss elite survey. MPs’ evaluations of party issue ownership are in line with those from the country experts (see Online Appendix D for detailed results).

Our second measure is committee specialisation. The same experts were asked to indicate the permanent parliamentary committees that are responsible for the specific policy statement. Where available, we also relied on descriptions of committees’ activities or meeting protocols. We then matched this information with data on the committee assignments for each MP, at the time of the survey. For each MP-statement dyad, we identify whether the MP is seated in the committee relevant for that statement and attribute the value 1 (committee specialisation) or 0 (no committee specialisation). For example, questions concerning the retirement age (‘The retirement age should be raised step by step’) are debated in the Labour and Social Affairs Committee in Germany, while the Swiss Security Policy Committee is responsible for debating whether ‘Switzerland needs to buy new fighter jets’. Overall, in 11.1 per cent (n = 336) of the MP-statement dyads in our data, the MP is seated in the committee relevant to that specific statement (from 4.4 per cent in data from Canada to 14.4 per cent in Switzerland).

Finally, we measured self-reported issue specialisation via a separate survey question. At the beginning of the survey, we showed MPs a list of approximately 20 general issue areas and asked them to indicate those that fell into their area of specialisation. We had made sure to include the issue areas of our policy statements. Thus, if MPs indicated that they were specialists in an issue area that matched the statement, we coded the politician as specialised in the statement. Across all 3,019 MP-statement dyads, 27.5 per cent (n = 829) have an MP who specialises in the issue at hand (from 22.9 per cent in Belgium to 32.4 per cent in Switzerland).

Taken together, for each statement on which an MP estimated the party voters’ opinion, we have three indicators for the specific MPs’ competence on that very policy statement. For example, for the statement on immigration in Canada (‘Canada should increase the number of immigrants it admits each year’), the Liberal Party was coded as the issue owner and the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration as the one responsible. Finally, if an MP listed ‘immigration and integration’ as an area of specialty in the survey, this was coded as a hit. Statements and the corresponding competence operationalisations can be found in Online Appendix C. gives an overview of all the variables and their descriptives.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation for the dependent, independent, and control variables.

Control variables

In order to gauge the influence of issue competence on perceptual accuracy, we control for several factors (see ). Because MPs might devote more attention to issues they deem salient, we control for the importance an MP attributes to a specific statement (Hedlund and Friesema Citation1972). Following the estimation of voters’ opinion in our survey, in a matrix question, we asked MPs to indicate, for each statement, how important it was for them personally at that moment, from 0 (very unimportant) to 10 (very important).

Moreover, not all politicians want to specialise in a limited number of issues, which leads to a systematic difference in the amount of cognitive resources they can invest in an issue. Thus, we control for the degree to which politicians see themselves as specialists versus generalists on a scale from 0 (small number of policy issues) to 10 (large number of policy issues) to the following question: ‘Some politicians specialise in one or two policy issues, while others prefer to act upon a wide range of policy issues. Where would you place yourself on the following scale?’ In addition, we control for MPs’ degree of congruence with their party. We use the answers to another survey question from 0 (high degree of congruence with party) to 10 (small degree of congruence with party).

Finally, we control for the MPs political experience and the party size (i.e. share of seats in Parliament) since MPs in smaller parties must often cover a wider range of issues than in bigger parties where there is a clear division of labour (Damgaard Citation1995: 323).

Analyses and discussion

MPs’ competence on issues can come from three primary sources: from the party, from being a member of a parliamentary committee, and from personal background or experiences (i.e. self-reported specialisation) which do not necessarily have to be mutually exclusive. Studies have shown that while, MPs often have extra-parliamentary experience (Eichenberger and Mach Citation2017; Mickler Citation2017: 135), the allocation of committee seats often depends on more than an MP’s expertise in the area (Andeweg and Thomassen Citation2011). Consequently, MPs can sometimes have a seat in a committee covering an area in which they would not consider themselves specialised.

Our data illustrate this point (). We have some observations of MP-statement dyads in which the MPs are seated on the committee responsible for a policy statement but in which they indicated, in the survey, that they did not consider themselves a specialist in the policy domain. Moreover, in only 11 per cent of the MP-statement dyads were MPs specialised via committee membership; this share is much higher for self-reported specialisation (27 per cent). This means we have the necessary variation in our data to tap into the effects of different aspects of an MP’s competence on their perceptual accuracy.

Table 3. Comparison of MPs’ committee and self-reported specialisations.

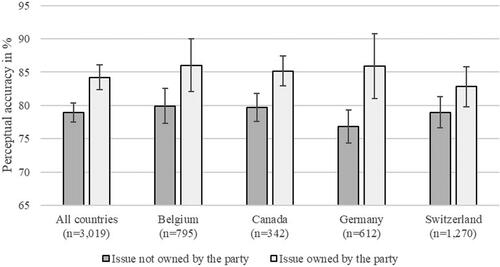

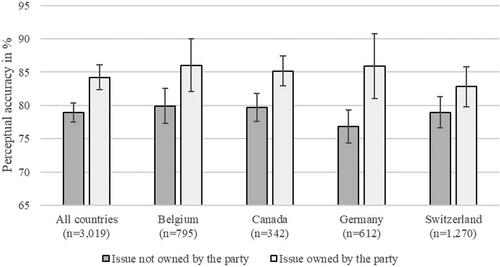

Our first hypothesis, however, looks at the party level. It states that MPs have more accurate perceptions of the opinion of their party voters when their party owns an issue. Our results show a clear pattern: MPs are significantly more accurate on policy statements that their party owns than on statements that their party does not own. Perceptual accuracy is 7 points higher for policy statements that a party owns than for those that a party does not own (from 78.6 per cent to 85.4 per cent, Welch’s t-Test t(1141.4)=10.40, p < 0.001 two-sided). This 7 points’ increase is an important effect since we have to keep in mind that a random rater would display an accuracy score of 75 (see methods section above).

For a randomly selected pair of statements (one owned and one not owned by the party), the politician is 62 per cent more likely to have higher accuracy on a statement that the party owns (Lakens Citation2013). This difference is stable in a regression model (b = 5.29, p < 0.001, Model 3 in ) and is consistent across countries (see ; for country-specific coefficients, see Online Appendices F and G). On issues for which their party can be considered an issue owner, MPs are thus significantly more accurate in their perceptions of party voters’ opinion.

Figure 2. Note. Predicted values based on Model 3 in (all countries) and Appendix G (country models). 95% confidence intervals reported.

Table 4. Multi-level linear regression models predicting the effects of competence on perceptions of party voters’ opinion among MPs.

We also expect that MPs who are members of a relevant committee are more accurate with the policy statement falling under the jurisdiction of this committee (H2). However, we cannot find any differences between MPs who are in a relevant parliamentary committee and those who are not (80.2 per cent for those in a committee and 79.9 per cent for those who are not, Welch’s t-Test t(430.1)=0.33, p = 0.372 one-sided). This finding is consistent once we control for other potential influential factors (b = 0.58, p = 0.539, Model 3 in ). Simply put, there is no indication that MPs are more accurate on policy statements covering their committee area than those which come from another issue area. This finding is consistent across countries if we run individual country models (Online Appendix G). Thus, despite the different levels of autonomy that parliamentary committees have (Mickler Citation2017), membership in a relevant committee does not make an MP more accurate.

The third indicator of competence is the self-reported specialisation. We expect that MPs are better on statements in which they consider themselves specialists (H3). Results in the full regression model show that this effect is significant in the overall model (b = –1.42, p = 0.035). MPs who consider themselves specialists in certain issue areas are slightly worse when it comes to knowing the opinion of their party voters. However, when we look at the individual country models, we see that there is more to it. Canadian MPs who consider themselves specialised in an issue show higher perceptual accuracy, as expected by our hypothesis (b = 3.93, p = 0.023). However, in Switzerland, MPs’ self-reported specialisation is related to 2.89 points less accuracy compared to those who do not consider themselves specialists (p = 0.004), which contradicts our hypothesis (see Online Appendix G).

This latter finding can be explained by more general psychological and cognitive mechanisms: politicians believe that they have more expertise in an area than they actually do (Fisher and Keil Citation2016; Dunning Citation2011) and project their own opinion onto others (Holmberg Citation1999). A recent experimental study underlines this point: In areas of expertise, Swedish MPs tend to be more close-minded and dogmatic and, thus, disregard information from voters who have diverging opinions (Pereira and Öhberg, Citation2021; Pereira Citation2021) illustrating the prevalence of the ‘curse of expertise’ (Fisher and Keil Citation2016). Another explanation can be that MPs who specialise in specific policy domains are strongly influenced by the positions voiced within a closed community. Indeed, if the actors belonging to the so-called ‘policy monopoly’ (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1993) control for the framing of the issue at stake and, furthermore, are more vocal (e.g. interest groups actively lobbying MPs; see Eichenberger et al. Citation2021) than apathetic citizens, then politicians have a biased information source and, thus, misperceive voters’ opinion. In addition, MPs’ who are exposed to the narratives of like-minded social media users (i.e. echo chambers) can be affected by a confirmation bias.

Conclusion

This study aimed to assess whether different dimensions of issue competence matter in terms of MPs’ ability to accurately estimate the policy preferences of their party voters. This question is highly relevant as MPs’ ability to estimate what their party voters want is, together with the MPs’ willingness to represent their party voters, a precondition for policy responsiveness and democratic representation. Even when MPs deliberately decide not to be responsive to their party voters, they must, at least, have an accurate perception of their policy preferences, in order to explain why they have a diverging policy position and be accountable (Esaiasson and Wlezien Citation2017; Pitkin Citation1967: 209).

Our findings are consistent across diverse political systems and policy domains. In policy issues in which their party holds a strong reputation for competence, MPs are definitively more accurate. MPs might learn from information about voters’ opinion not only on new issues (Butler and Nickerson Citation2011) but also on issues that are at the core of their party’s programme. The patterns we find suggest that issue ownership not only helps to connect voters with parties in elections (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008; Lachat Citation2014) but also translates into higher perceptual accuracy and, thus, affects the core of the representation mechanism. The results also signal that MPs might be more receptive to partisan information about voters’ preferences than to non-partisan information, such as public opinion polling data (Kalla and Porter Citation2020). While this finding is expected for a partitocratic system like Belgium, the consistency of this pattern in less party-centric systems like Switzerland speaks to its relevance across institutional contexts.

In contrast, legislative specialisation through membership in the policy-relevant committee does not make MPs more accurate. Although such legislative organisation probably allows MPs to acquire technical expertise and ‘hear out’ policy stakeholders, it might put MPs under the constraint of anticipating their colleagues’ opinion to avoid a strong divergence between the policy solution elaborated by the committee and the law eventually adopted by the plenary. Thus, the incentives for committee members to figure out what party voters want does not differ that much from non-specialised MPs.

There is evidence that MPs are even more distorted in their perception of party voters’ opinion when they self-report as being particularly competent on a certain issue. However, the findings here are mixed and potential explanations rooted in cognitive psychology do not explain the differences we find across the countries, nor the fact that we find a consistently positive effect of the importance of a statement for perceptual accuracy. Whether these diverging findings are rooted in the country’s political system, for example, the electoral system (Sieberer Citation2010), other studies will have to investigate in more detail.

Another aspect that our study did not cover is whether the findings hold if we look at MPs’ perceptions of a broader public beyond their party electorate. One could argue that MPs and parties not only compete to convince their core voters but must also attract new voters (Seeberg Citation2020). Consequently, MPs should be incentivised to assess the policy preferences of all constituents from different political parties within their respective electoral districts. This should be particularly the case in majoritarian electoral systems like Canada, in which, to get elected, an MP might need electoral support beyond their party’s boundary. However, considering an MP’s perception of what the general population wants is also relevant in proportional systems where MPs do take their potential voters into account too. Indeed, as demonstrated by Esaiasson and Holmberg (Citation1996) for the case of Sweden, representative democracy is not only about party politics (see also Pereira Citation2021).

Furthermore, the distributive theory of committee assignments (Bowler and Farrell Citation1995: 222; Shepsle and Weingast Citation1982) postulates that specialists should be motivated to join legislative committees that address issues relevant to their own constituency. Committee members thus have a strong motivation to be very accurate in estimating their constituents’ preferences. While the mechanism through which competence translates into perceptual accuracy might be similar if one looks at the constituency, the lower homogeneity of the opinions might make it more difficult for MPs more generally. Our study provides a starting point for such investigations.

We see two main implications from our results. First, the literature on perceptual accuracy has recurrently shown that stark party differences in MPs’ perceptual accuracy exist, e.g. between Republicans and Democrats in U.S. states (Broockman and Skovron Citation2018), or between Left and Right parties in Portugal (Belchior Citation2014) and Sweden (Esaiasson and Holmberg Citation1996). However, none of these studies empirically addressed which party features explain differences in MPs’ ability to gauge voters’ opinion. Based on our findings, we argue that competence issue ownership plays an important role and can help understand variation in perceptual accuracy across parties and MPs. Upcoming studies should thus include a variety of policy issues and focus on MP-issue dyads as a unit of analysis.

Second, this study also contributes to the rich literature on legislative committees, which has mostly scrutinised which MPs sit on which committees and why. Measuring the impact of committee specialisation on MPs’ perceptual accuracy directly taps into the informational theory of legislative organisations and committee assignments. However, we do not find any indication that MPs sitting in the policy-relevant committee can exploit their privileged sources of information or higher information processing capacity to better estimate what their party voters want. This goes against the informational theory and requires further empirical investigation.

In sum, our study shows that while MPs might not exploit informational advantages in their committees or due to their specialisations, they are better at knowing the opinions of their party voters on issues that their party owns. This finding underlines the centrality of party issue ownership in the many studies on representation and, more specifically, voters’ choice. Previous studies applying the issue ownership or saliency approach have either scrutinised the selective emphasis of issues during electoral campaigns or investigated how voters evaluate a party based on their perceptions of party competence on specific issues. Our finding that elected representatives are much more accurate in their perceptions of their electorate on party-owned issues provides an empirical basis for the crucial link between the role of party issue ownership for voting and substantive democratic representation.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (940.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Steven Eichenberger, Anina Hanimann, Tim Mickler, Miguel Pereira, Adrien ‘Babysteps’ Petitpas, Jan Rosset and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

A replication package with the data and syntax (Stata 14.0) used for this publication is available at the Yareta depository under the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta:ng5czaxdvreepoay6qw3mwpapa

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Frédéric Varone

Frédéric Varone is Professor of Political Science at the University of Geneva. His research interests include comparative public policy, political representation, and interest groups. His most recent book is co-authored with Michael Hill: The Public Policy Process, 8th edition (Routledge 2021). [frédé[email protected]]

Luzia Helfer

Luzia Helfer is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Geneva. Her research interests include perceptions by legislators and their relationships with the public and media/journalists, mainly from a comparative perspective. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The initial study included data from The Netherlands. Due to limited quality of the public opinion data we report the results from 30 MPs who evaluated 237 policy statements separately in Online Appendix H. Findings are in line with the overall conclusions of the main paper: party issue ownership is positively associated with perceptual accuracy but the coefficient does not reach significance (b = 4.98, p = .104, see Online Appendix H for full results).

2 Data for the citizen and MP surveys were collected in the framework of the POLPOP project. POLPOP is a transnational collaboration examining the perceptual accuracy of politicians in five countries, initiated by Stefaan Walgrave. The Principal Investigators per country responsible for data collection and funding agencies were, for Flanders-Belgium: Stefaan Walgrave [FWO G012517N]; Wallonia and Brussels-Belgium: Jean-Benoit Pilet and Nathalie Brack [FNRS, T.0182.18]; Canada: Peter Loewen and Lior Sheffer [SSHRC Insight Grant for ‘The local parliament: voter preferences, local campaigns, and the parliamentary representation of voters’]; Germany: Christian Breunig and Stefanie Walter [partial funding by the Committee on Research at the University of Konstanz]; Netherlands: Rens Vliegenthart and Toni van der Meer; and Switzerland: Frédéric Varone and Luzia Helfer [SNSF #100017_172559].

References

- Andeweg, Rudy B. (2014). ‘Roles in Legislatures’, in Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld, and Kaare W. Strøm (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 267–85.

- Andeweg, Rudy B., and Jacques Thomassen (2011). ‘Pathways to Party Unity: Sanctions, Loyalty, Homogeneity and Division of Labour in the Dutch Parliament’, Party Politics, 17:5, 655–72.

- Baumgartner, Frank, and Brian Jones (1993). Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Bélanger, Éric, and Bonnie M. Meguid (2008). ‘Issue Salience, Issue Ownership and Issue-Based Vote Choice’, Electoral Studies, 27:3, 477–91.

- Belchior, Ana Maria (2014). ‘Explaining MPs’ Perceptions of Voters’ Positions in a Party-Mediated Representation System: Evidence from the Portuguese Case’, Party Politics, 20:3, 403–15.

- Bellucci, Paolo (2006). ‘Tracing the Cognitive and Affective Roots of “Party Competence”: Italy and Britain, 2001’, Electoral Studies, 25:3, 548–69.

- Bowler, Shaun (2017). ‘Trustees, Delegates, and Responsiveness in Comparative Perspective’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 766–93.

- Bowler, Shaun, and David M. Farrell (1995). ‘The Organizing of the European Parliament: Committees, Specialization and Co-ordination’, British Journal of Political Science, 25:2, 219–43.

- Broockman, David E., and Christopher Skovron (2018). ‘Bias in Perceptions of Public Opinion among Political Elites’, American Political Science Review, 112:3, 542–63.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis Farlie (1983). ‘Party Competition – Selective Emphasis or Direct Confrontation? An Alternative View with Data’, in Daalder Hans and Peter Mair (eds.), West European Party Systems. Continuity and Change. London: Sage, 267–305.

- Butler, Daniel M., and David W. Nickerson (2011). ‘Can Learning Constituency Opinion Affect How Legislators Vote? Results from a Field Experiment’, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 6:1, 55–83.

- Clausen, Aage R. (1977). ‘The Accuracy of Leader Perceptions of Constituency Views’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 2:4, 361–84.

- Clausen, Aage R., Soren Holmberg, and Lance deHaven-Smith (1983). ‘Contextual Factors in the Accuracy of Leader Perceptions of Constituents’ Views’, The Journal of Politics, 45:2, 449–72.

- Converse, Philip E., and Roy Pierce (1986). Political Representation in France. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Dahl, Robert A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Damgaard, Erik (1995). ‘How Parties Control Committee Members’, in Herbert Döring (ed.), Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 308–25.

- Dolezal, Martin, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Anna Katharina Winkler (2014). ‘How Parties Compete for Votes: A Test of Saliency Theory’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:1, 57–76.

- Dudzińska, Agnieszka, Corentin Poyet, Olivier Costa, and Bernhard Wessels (2014). ‘Representational Roles’, in Kris Deschouwer and Sam Depauw (eds.), Representing the People. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 19–38.

- Dunning, David (2011). ‘The Dunning-Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One’s Own Ignorance’, in James M. Olson and Mark P. Zanna (eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York, NY: Elsevier, 247–96.

- Eichenberger, Steven, and André Mach (2017). ‘Formal Ties between Interest Groups and Members of Parliament: Gaining Allies in Legislative Committees’, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 6:1, 1–21.

- Eichenberger, Steven, Frédéric Varone, and Luzia Helfer (2021). ‘Do Interest Groups Bias MPs’ Perception of Party Voters’ Preferences?’, Party Politics. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068821997079

- Erikson, Robert S., Norman S. Luttbeg, and William V. Holloway (1975). ‘Knowing One’s District: How Legislators Predict Referendum Voting’, American Journal of Political Science, 19:2, 231–46.

- Esaiasson, Peter, and Sören Holmberg (1996). Representation from Above: Members of Parliament and Representative Democracy in Sweden. London: Routledge.

- Esaiasson, Peter, and Christopher Wlezien (2017). ‘Advances in the Study of Democratic Responsiveness: An Introduction’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 699–710.

- Fenno, Richard F. (1973). Congressmen and Committees. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

- Fisher, Matthew, and Frank C. Keil (2016). ‘The Curse of Expertise: When More Knowledge Leads to Miscalibrated Explanatory Insight’, Cognitive Science, 40:5, 1251–69.

- Gilligan, Thomas W., and Keith Krehbiel (1987). ‘Collective Decisionmaking and Standing Committees: An Informational Rationale for Restrictive Amendment Procedures’, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 3, 287–335.

- Grandberg, Donald (1985). ‘An Anomaly in Political Perception’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 49, 504–16.

- Green, Jane, and Will Jennings (2012). ‘The Dynamics of Issue Competence and Vote for Parties in and out of Power: An Analysis of Valence in Britain, 1979–1997’, European Journal of Political Research, 51:4, 469–503.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen (2010). Issue Competition and Election Campaigns: Avoidance and Engagement. Aarhus: Aarhus University.

- Hedlund, Ronald D., and H. Paul Friesema (1972). ‘Representatives’ Perceptions of Constituency Opinion’, The Journal of Politics, 34:3, 730–52.

- Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander, Matteo Mildenberger, and Leah C. Stokes (2019). ‘Legislative Staff and Representation in Congress’, American Political Science Review, 113:1, 1–18.

- Holmberg, Sören (1999). ‘Wishful Thinking among European Parliamentarians’, in Hermann Schmitt and Jacques Thomassen (eds.), Political Representation and Legitimacy in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 235–50.

- Kalla, Joshua L., and Ethan Porter (2020). ‘Correcting Bias in Perceptions of Public Opinion among American Elected Officials: Results from Two Field Experiments’, British Journal of Political Science. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712341900071

- Lachat, Romain (2014). ‘Issue Ownership and the Vote: The Effects of Associative and Competence Ownership on Issue Voting’, Swiss Political Science Review, 20:4, 727–40.

- Lakens, Daniel (2013). ‘Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for t-Tests and ANOVAs’, Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

- Lax, Jeffrey R., and Justin H. Phillips (2012). ‘The Democratic Deficit in the States’, American Journal of Political Science, 56:1, 148–66.

- Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski, and Susan C. Stokes (1999). ‘Elections and Representation’, in Przeworski Adam (ed.), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 29–54.

- Mansbridge, Jane (2003). ‘Rethinking Representation’, American Political Science Review, 97:4, 515–28.

- Martin, Lanny V., and Georg Vanberg (2011). Parliaments and Coalitions: The Role of Legislative Institutions in Multiparty Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Shane, and Tim A. Mickler (2019). ‘Committee Assignments: Theories. Causes and Consequences’, Parliamentary Affairs, 72:1, 77–98.

- Mattson, Ingvar, and Kaare W. Strøm (1995). ‘Parliamentary Committees’, in Herbert Döring (ed.), Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 249–307.

- Mickler, Tim A. (2017). ‘Committee Autonomy in Parliamentary Systems - Coalition Logic or Congressional Rationales?’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23:3, 367–91.

- Miller, Warren E., and Donald E. Stokes (1963). ‘Constituency Influence in Congress’, American Political Science Review, 57:1, 45–177.

- Peeters, Jeroen, Peter Van Aelst, and Stiene Praet (2019). ‘Party Ownership or Individual Specialization? A Comparison of Politicians’ Individual Issue Attention across Three Different Agendas’, Party Politics, 27:4, 692–703.

- Pereira, Miguel M. (2021). ‘Understanding and Reducing Biases in Elite Beliefs About the Electorate’, American Political Science Review. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100037X

- Pereira, Miguel M., and Patrik Öhberg (2021). ‘The Expertise Curse: How Policy Expertise Can Hinder Responsiveness’. Working paper, available at https://www.dropbox.com/s/a5g4be4t892pmp7/PereiraOhberg_Expertise_v7.pdf?dl=0 (accessed 27 May 2021).

- Petrocik, John R. (1996). ‘Issue Ownership and Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study’, American Journal of Political Science, 40:3, 825–50.

- Petrocik, John R., William L. Benoit, and Glenn J. Hansen (2003). ‘Issue Ownership and Presidential Campaigning, 1952–2000’, Political Science Quarterly, 118:4, 599–626.

- Pitkin, Hanna (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rosset, Jan, Nathalie Giger, and Julian Bernauer (2017). ‘I the People? Self-Interest and Demand for Government Responsiveness’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 794–821.

- Rovny, Jan (2012). ‘Who Emphasizes and Who Blurs? Party Strategies in Multidimensional Competition’, European Union Politics, 13:2, 269–92.

- Saalfeld, Thomas, and Kaare W. Strøm (2014). ‘Political Parties and Legislators’, in Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld, and Kaare W. Strøm (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 371–98.

- Searing, Donald D. (1987). ‘New Roles for Postwar British Politics: Ideologues, Generalists. Specialists, and the Progress of Professionalization in Parliament’, Comparative Politics, 19:4, 431–52.

- Seeberg, Henrik Bech (2020). ‘How Political Parties’ Issue Ownerships Reduce to Spatial Proximity’, West European Politics, 43:6, 1238–61.

- Sevenans, Julie, Stefaan Walgrave, Arno Jansen, Karolin Soontjens, Stefanie Bailer, Nathalie Brack, Christian Breunig, et al. (2021). ‘Projection in Politicians’ Perceptions of Public Opinion’, unpublished manuscript.

- Sieberer, Ulrich (2010). ‘Behavioral Consequences of Mixed Electoral Systems: Deviating Voting Behavior of District and List MPs in the German Bundestag’, Electoral Studies, 29:3, 484–96.

- Sigel, Roberta S., and H. Paul Friesema (1965). ‘Urban Community Leaders’ Knowledge of Public Opinion’, The Western Political Quarterly, 18:4, 881–95.

- Shepsle, Kenneth A., and Barry R. Weingast (1982). ‘Institutionalizing Majority Rule: A Social Choice Theory with Policy Implications’, The American Economic Review, 72, 367–71.

- Soroka, Stuart N., and Christopher Wlezien (2010). Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stimson, James A., Michael B. Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson (1995). ‘Dynamic Representation’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 543–65.

- Strøm, Kaare W. (1990). ‘A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties’, American Journal of Political Science, 34:2, 565–98.

- Strøm, Kaare W. (1998). ‘Parliamentary Committees in European Democracies’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 4:1, 21–59.

- Tresch, Anke (2009). ‘Politicians in the Media: Determinants of Legislators’ Presence and Prominence in Swiss Newspapers’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 14:1, 67–90.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevere, and Anke Tresch (2012). ‘The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:4, 771–82.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Anke Tresch, and Jonas Lefevere (2015). ‘The Conceptualisation and Measurement of Issue Ownership’, West European Politics, 38:4, 778–96.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Arno Jansen, Julie Sevenans, Karolin Soontjens, Stefanie Bailer, Nathalie Brack, Christian Breunig, Luzia Helfer, Peter Loewen, Toni van der Meer, Jean-Benoit Pilet, Lior Sheffer, Frédéric Varone and Rens Vliegenthart (2021). ‘Inaccurate Politicians. Elected Representatives’ Estimations of Public Opinion in Four Countries’, unpublished manuscript.

- Wlezien, Christopher, and Stuart N. Soroka (2012). ‘Political Institutions and the Opinion-Policy Link’, West European Politics, 35:6, 1407–32.