?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Polarisation is often seen as mainly negative for the functioning of democracies, but one of its saving graces could be that it raises the stakes of politics and encourages participation. This study explores the relationship between affective polarisation and turnout using three longitudinal designs. It makes use of three decades of repeated cross-sectional surveys in Germany, a two-wave panel study in Spain, and an eleven-wave panel study in the Netherlands. It tests whether affective polarisation increases turnout using varying operationalizations and specifications, and studies whether any boost in participation extends beyond the most politically sophisticated citizens. The findings suggest a sizeable independent effect of affective polarisation on turnout even when accounting for reverse causality and for the confounding impact of positive partisanship and ideological polarisation. Importantly, this effect might even be somewhat more pronounced among those who are least sophisticated. The concluding section discusses the normative and theoretical implications of these findings.

Dislike for opposing parties and partisans has recently become a dominant theme in the analysis of political competition. Extensive research has shown that negative partisanship and affective polarisation are on the rise in the United States (Iyengar et al. Citation2019), but recent work has provided evidence of their importance in many other contexts too (Westwood et al. Citation2018; Helbling and Jungkunz Citation2020; Gidron et al. Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021). In this line of research, affective polarisation is generally seen as a dangerous development, with scholars highlighting potential negative consequences in terms of the erosion of democratic norms, the decline of social trust and the increase in partisan prejudice and discrimination.

In contrast, far less scholarly attention has been given to possible benevolent consequences of affective polarisation (see also Borbáth et al. Citation2022). A potential saving grace—or at least a blessing in disguise—of affective polarisation could be that it increases engagement with, and participation in, politics. Interestingly, a recent influential review article (Iyengar et al. Citation2019) makes no mention of potential mobilising effects of affective polarisation, and there has been little research on this possibility (with the partial exceptions of Ward and Tavits Citation2019 and Wagner Citation2021). Yet, the argument for why affective polarisation may increase political participation is simple: the greater the dislike of other parties, the more is at stake in political competition (Ward and Tavits Citation2019). By turning political opponents into enemies, participating in politics becomes more important simply to keep them out of power. While rational-choice research noted that it is irrational for any individual to invest time in going to the ballot box (Downs Citation1957; Riker and Ordeshook Citation1968), group politics might be a force that drives electoral participation (Edlin et al. Citation2007). By linking politics to intergroup conflict, affective polarisation may make voters care about politics more than ideological disagreements do. In this respect, affective polarisation can be seen as the oxygen of democracy: while it is needed to keep democracy breathing, an excess can make everything go up in flames.

Although the link between affective polarisation and turnout has largely been ignored in existing research, there is some, albeit limited, empirical evidence of such an effect. Using cross-national, cross-sectional data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), Ward and Tavits (Citation2019) and Wagner (Citation2021) operationalise affective polarisation based on individual-level variation in like-dislike scores for parties and document that higher levels of such polarisation are associated with higher reported turnout at elections. This correlation dovetails with the—more impressionistic—observation that turnout has gone up recently in elections that were characterised by deep partisan divisions, such as in the United States or the United Kingdom.

While important cross-sectional evidence thus exists, the insights from such studies are necessarily limited for four reasons. First, the relationship between polarisation and turnout might be reciprocal. Turning out to vote could increase people’s engagement with politics, which in turn could heighten the extent to which they loathe their opponents. Second, affective polarisation is likely to be highly correlated with other individual-level characteristics such as personality and interest. Third, given that affective polarisation varies strongly between countries (Reiljan Citation2020; Gidron et al. Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021), correlations at the aggregated level might be confounded by factors at the polity level. Fourth, assessing the impact of polarisation on turnout is difficult using postelection studies, which take place after elections; this means that levels of affective polarisation might reflect developments since the vote took place, leading to incorrect inferences about the link between turnout and polarisation. These four limitations of existing studies motivate our examination across time, both within individuals using panel studies and between individuals using time-series cross-section data.

In assessing the impact of affective polarisation on turnout, our study also accounts for two important related phenomena: positive partisanship and ideological (or programmatic) polarisation. As we discuss below, there is extensive evidence that positive partisanship and ideological polarisation both positively affect political participation. Both phenomena are strongly related to affective polarisation; in the case of positive partisanship, this relationship is even intrinsic as positive in-party feelings are usually studied as a component of affective polarisation. Yet, affective polarisation is distinct from both partisanship and ideological polarisation as it also captures outgroup dislike, and this may provide an additional mobilising motivation. Analyses that claim to uncover an independent effect of affective polarisation on turnout and participation need to account for these two confounders (Wagner Citation2021).

Finally, rather than assuming monolithic effects, it is important to consider how the effects of affective polarisation might differ between groups of citizens. Here, we build on studies of party polarisation which suggest that that effects on turnout are moderated by political sophistication (Rogowski Citation2014; Moral Citation2017) and model such interactions explicitly.

Our paper aims to contribute to our understanding of the mobilising effect of affective polarisation using a combination of three studies that, together, add substantively to the limited findings from earlier research. All three studies consist of data collected at multiple points in time, allowing us to study the relationship between affective polarisation and turnout dynamically. In Study 1, we study affective polarisation and turnout within German monthly data from 1990 to 2018, employing an aggregated time series analysis. In Study 2, we complement these findings with cross-lagged regression models using data from the two-wave E-DEM panel study in Spain (Torcal et al. Citation2020). Finally, in Study 3 we use an eleven-wave panel from the Netherlands to confirm the findings from the first two studies. Next to the inferential benefit of using longitudinal designs, the studies also provide more varied measures of affective polarisation and turnout (intention) than those hitherto employed. For example, the German data allows us to study actual turnout in addition to self-reported turnout intention, while the Spanish data includes a measure of dislike towards fellow citizens of opposing political camps rather than the dislike of political parties in the abstract assessed in most surveys. Each study thus has unique methodological strengths and weaknesses, and combining results from all three increases confidence in our findings.

Overall, we find strong support for a positive effect of affective polarisation on turnout. This effect is larger than that of ideological polarisation and also appears both stronger and more robust than the reverse effect of turnout on affective polarisation; it also largely remains even if we control for positive partisanship. In addition, we find that affective polarisation has a mobilising effect across different levels of political sophistication, with some indication that it might be most mobilising among the least sophisticated. Hence, this paper provides strong, consistent evidence of an important consequence of affective polarisation that has hitherto received surprisingly little attention. Moreover, it shows that affective polarisation can have the beneficial consequence of reducing the participation gap—although we argue that participation driven exclusively by affective polarisation is itself potentially problematic.

Polarisation, partisan affect and turnout

Citizens are more likely to go to the polls if they think the election is important, and the perception of importance is clearly related to how much people believe a country would change depending on who is elected. Thus, electoral participation is partly driven by perceptions of what is at stake. There is a lot of evidence suggesting that the more competitive and decisive an election is, the more likely voters are to participate (Blais and Dobrzynska Citation1998; Franklin Citation2004). Related to this, closer elections also tend to have higher turnout (Geys Citation2006), as do elections at which anti-political establishment parties take part (cf. Nemčok et al. Citation2022). This intuition that the stakes matter informs the hypothesised effect of affective polarisation on turnout. Before exploring that mechanism in more detail, we discuss the related mobilising effect of ideological polarisation and partisanship.

Ideological polarisation, partisanship and turnout

Two established aspects that increase the perceived stakes of elections are partisanship and ideological polarisation. Ideological polarisation (also known as programmatic polarisation) tends to lead to higher levels of turnout (Abramowitz and Stone Citation2006; Abramowitz and Saunders Citation2008; Dalton Citation2008; Crepaz Citation1990; Hetherington Citation2008; Steiner and Martin Citation2012; Moral Citation2017; Wilford Citation2017; Béjar et al. Citation2020; Dassonneville and Çakır Citation2021). However, not all research points to a clear positive effect of ideological polarisation on turnout (Franklin Citation2004; Rogowski Citation2014), with some work arguing that polarisation may demobilise centrist voters (Fiorina et al. Citation2008; Hetherington Citation2008). In addition, research differs on the kind of ideological polarisation it examines. Most existing research examined the actual polarisation of political elites (e.g. Steiner and Martin Citation2012; Wilford Citation2017; Béjar et al. Citation2020), but recent work has also considered perceptions of this polarisation among voters: Enders and Armaly (Citation2019) thus find different effects for actual and perceived ideological polarisation (but see Moral Citation2017).

Existing work points to several mechanisms linking increased ideological polarisation to higher turnout. Thus, ideological polarisation should increase the perception that a lot is at stake: the greater the ideological range of programmes proposed, the more it matters for policy outcomes who is elected (Crepaz Citation1990; Franklin Citation2004). It should also increase the probability that citizens find a party that represents their views well (Blais et al. Citation2014), thereby reducing the impact of abstention induced by alienation or indifference (Adams and Merrill Citation2003; Adams et al. Citation2006; Callander and Wilson Citation2007; Murias Muñoz and Meguid Citation2021). Relatedly, ideological polarisation may also increase the clarity of party positional cues and thereby decrease the difficulty of choosing between competitors (Lachat Citation2008; Blais and Dobrzynska Citation1998). Finally, there are important theoretical and empirical linkages between spatial models and non-policy factors such as partisanship (Lachat Citation2015; Moral and Zhirnov Citation2018). For our purposes, it is relevant that ideological polarisation may encourage turnout in part by fostering partisanship (Crepaz Citation1990; Westfall et al. Citation2015), the distinct effects of which we will now discuss.

Positive partisanship increases turnout because it provides a motivation to vote, namely to see one’s own side do well. Partisanship has consistently been linked to political engagement, which in turn fosters turnout (Campbell et al. Citation1960; Greene Citation2004; Smets and Van Ham Citation2013). Huddy et al. (Citation2015) show that the expressive aspects of partisanship—i.e. those based on identity rather than ideology or perceived competence—are particularly strong drivers of campaign involvement. Elections also present threats to one’s in-party, so ‘electoral involvement is one way in which partisans can defend their party against such potential losses or can ensure gains’ (Huddy et al. Citation2015). Exposure to electoral threat may mean that these positive identities then generate important mobilising emotions such as enthusiasm or anger (Valentino et al. Citation2011; Valentino and Neuner Citation2017). Related work also finds that in-group trust more generally increases political participation (Crepaz et al. Citation2014).

Affective polarisation and turnout

Affective polarisation captures strong positive feelings towards one’s in-party as well as strong negative feelings towards out-parties (Iyengar et al. Citation2012). This concept therefore builds on the notion of partisanship as a social and expressive identity (Greene Citation2004; Huddy et al. Citation2015), but adds out-group bias to the previous focus on positive in-group identification. Affective polarisation may also have ideological foundations, with group identities based on and fed by ideological differences (Orr and Huber Citation2020). Hence, affective polarisation is intrinsically linked both to positive partisanship and ideological polarisation, both of which are positive predictors of affective polarisation (Rogowski and Sutherland Citation2016; Wagner Citation2021; Hernandez et al. Citation2021), although the effect may go in both directions (Diermeier and Li Citation2019).

Previous studies indeed uncovered a correlation between affective polarisation and turnout using cross-national, cross-sectional election survey data. Thus, Ward and Tavits (Citation2019) show that affective polarisation has a large effect on turnout. Wagner (Citation2021) finds similar results using the same dataset and various measures of affective polarisation while additionally controlling for ideological polarisation and positive partisanship. This research shows that the effect of affective polarisation is about one third of that of in-group partisanship, but also substantively larger than that of perceived left–right polarisation. In addition, Abramowitz and Stone (Citation2006) and Abramowitz and Saunders (Citation2008) find a link between turnout and the gap in feelings towards the two presidential candidates, which may partly reflect partisan affective polarisation. Finally, Mayer (Citation2017) finds that negative partisanship, a component of affective polarisation, increases turnout by about nine percentage points on average (see also Caruana et al. Citation2015).

Affective polarisation should have a distinct positive impact on turnout, going beyond the influence of positive in-group partisanship and ideological polarisation. We thus follow Ward and Tavits (Citation2019: 2), who argue that ‘affective polarisation results in viewing politics through the lens of group conflict and thereby raises the perceived stakes of electoral competition’. Unlike ideological polarisation, then, affective polarisation is based on social group identities, both concerning the favoured in-group and the disliked out-group. Moreover, what distinguishes the impact of affective polarisation from mere positive partisanship is the extent to which individuals have negative feelings towards out-parties and their supporters.

Hence, affective polarisation should drive turnout even when ideological polarisation and positive partisanship are accounted for. Affective polarisation provides an additional, group-based motivation to support one’s in-group and prevent the out-group from winning and obtaining power, and negative evaluations of out-group parties and partisans in particular may drive turnout for several reasons. For one, affective polarisation may increase turnout because negative out-party feelings may foster important mobilising and motivating emotions such as anger and Schadenfreude (Valentino et al. Citation2011; Huddy et al. Citation2015). The role of anger in motivating conflict-oriented intergroup behaviour has been demonstrated more generally (Claassen Citation2016). In addition, affective polarisation is likely to do more than mere positive in-group feelings to raise the perceived stakes of an election. The deeper the intergroup conflict, the more important it becomes to one’s self-image not to lose out to the ‘outgroup’. As noted by Huddy et al. (Citation2015: 3), ‘[p]artisans (…) internalised sense of partisan identity means that the party’s failures and victories become personal. The maintenance of positive distinctiveness is an active process, especially when a party’s position or status is threatened’. Outgroup bias distorts perceptions of the opposing camps’ intentions and the willingness to even consider its claims (Strickler 2017). The urge to offset this threat might offset the costs of taking the effort to go out and vote. Moreover, all of these considerations are likely to loom large in citizens’ minds due to negativity bias. In short, it might particularly be the possibility of losing to disliked groups that pushes people to participate. We therefore expect that affective polarisation has a positive impact on voter turnout.

At the same time, turnout (and the intention to do so) may in turn influence affective polarisation. First, the act of voting itself may have downstream effects on political involvement and engagement. Turning out may therefore increase political interest and partisanship (Meredith Citation2009; Dinas Citation2014; Braconnier et al. Citation2017). Mullainathan and Washington (Citation2009) find that turnout increases ideological polarisation, so a link to affective polarisation is also plausible. However, for evidence against long-term transformative effects of turning out, see Holbein and Rangel (Citation2020) and Holbein et al. (Citation2021). Nevertheless, even a short-term boost in political involvement and partisanship may foster affective polarisation. Second, most previous studies (as well as most of the analyses presented in the current study) measure the intention to turn out to vote rather than turnout itself, and this intention may be a strong proxy for political involvement and engagement. To the extent that these characteristics predict rather than result from affective polarisation, cross-sectional analyses could result in faulty inferences. In our empirical analysis, we therefore also account for whether turnout (and the intention to do so) has a positive effect on affective polarisation.

Does political sophistication moderate the impact of polarisation on turnout?

Political sophistication is an important potential moderator of the impact of polarisation on turnout. The term ‘political sophistication’ captures a range of characteristics, including political knowledge, attention to politics, and cognitive ability, and is usually measured using a mixture of questions assessing knowledge, interest, and/or educational attainment (Lachat Citation2008; Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Citation2017; Dalton Citation2021). While there is evidence that polarisation is higher among engaged voters (e.g. Abramowitz and Saunders Citation2008; Abramowitz Citation2010), we do not know whether sophistication influences the polarisation-turnout connection, provided it exists. Understanding how sophistication moderates the impact of polarisation is crucial for our normative understanding of its appeal. After all, if polarisation further increases participatory inequalities by making politics appealing to the most sophisticated only, this would diminish its side effects. However, if polarisation draws new groups into politics, its silver lining is more pronounced.

The literature on party ideological polarisation suggests participation boosts due to ideological polarisation might actually reinforce engagement inequalities as they are confined mainly to more sophisticated voters, as only these engage with politics and electoral decisions at a more detailed ideological or policy level. Rogowski (Citation2014) thus finds that increased ideological polarisation actually reduces turnout among less-sophisticated voters. In a related account, Moral (Citation2017) suggests ideological polarisation more consistently fosters turnout among sophisticated voters than among unsophisticated voters. He finds that increases in ideological polarisation do not increase the propensity to vote among less sophisticated voters, unlike among more sophisticated voters.

On the other hand, the effect of affective polarisation on turnout might be moderated less by political sophistication than that of ideological polarisation. Mobilisation based on identity is less based on detailed engagement with policy or ideological differences. Indeed, Huddy et al. (Citation2015) stress that expressive aspects of partisanship drive involvement even among sophisticated citizens, rather than particularly among such citizens. There is also evidence that emotional appeals have a stronger impact among more knowledgeable than among less knowledgeable citizens (Jones et al. Citation2013). For these reasons, we expect that the effect of affective polarisation on turnout does not differ between more sophisticated and less sophisticated voters.

Research design

We use three data sources that contain measures of affective polarisation and of turnout: the Politbarometer dataset for Germany, the E-DEM panel for Spain, and the LISS panel for the Netherlands. These three datasets are all longitudinal within countries and (in Spain and the Netherlands) within individuals. We make use of three different longitudinal designs to account for reverse causality; while each study has limitations, the cumulative findings should lead to confidence in our results. The first study on Germany uses monthly survey data, which we use for an aggregated time-series analysis and for an analysis of predictors of turnout at regional elections. The second and third studies make use of two-wave and eleven-wave panel surveys from Spain and the Netherlands, respectively. Here, we run panel data models that control for lagged values of both variables. Thus, all studies study the interrelationship between our two key variables over time, but use different modelling and measurement approaches.

In all three studies, we measure affective polarisation using feeling thermometers, a common approach (Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Ward and Tavits Citation2019; Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021; Gidron et al. Citation2020). The questions we use are very similar to the standard thermometer scales used in US research (Iyengar et al. Citation2019) and the like-dislike scales used in comparative research (Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021). However, thermometer questions addressing political parties in the abstract (such as ‘the CDU’) measure affect towards party elites rather than partisans (Druckman and Levendusky Citation2019), even if these thermometer scales correlate to a convincing degree with more detailed measures of affective evaluations of parties and their members (Iyengar et al. Citation2019). To address this shortcoming, Study 2 uses a different measure of affective polarisation based on feeling thermometers towards party supporters rather than abstract parties. In all three studies, we use the unweighted spread-of-scores measure of affective polarisation proposed by Wagner (Citation2021),

where p is the party, i the individual respondent, and likeipthe like–dislike score assigned to each party p by individual i. We replicate each analysis using the weighted measure proposed by Wagner (Citation2021), which weights each party by its size, and report those in the text and in the Online appendices.

All studies contain measures of turnout using self-reports, either of turnout itself or of turnout intentions. This, too, is a standard operationalisation choice. While survey measures of turnout are strongly prone to overreporting and nonresponse bias (Sciarini and Goldberg Citation2016), this holds for both more and less affective polarised individuals. Hence, it allows us to study whether affective polarisation increases the extent to which people want to vote. In addition, in Study 1 we also model actual turnout at the regional level in Germany to see whether our findings also hold beyond survey-based turnout measures.

Finally, we measure our key moderating variable, political sophistication, using political interest. While there are various aspects to the concept of political sophistication, we are mainly interested in how affective polarisation matters across different levels of self-assessed engagement with the political system. We replicate our main analysis of Study 2 using a measure of political knowledge.

summarises the key features of the three studies that allow us to cross-validate our results using different approaches and measures.

Table 1. Key features of studies 1 to 3.

In all studies, our models include two important control variables: ideological polarisation on the aggregate level (understood as divergence of views among citizens) or individual level (an individual’s divergence from the population mean); and sympathy towards the in-party. The latter is part, mechanically, of affective polarisation. Affective polarisation should stimulate turnout beyond mere in-party identification, so we control for in-party sympathy throughout. Note that Studies 1 and 2 include party-level ideological polarisation in some of the analyses, in line with most existing research on the effect of ideological polarisation on turnout. Part of Study 1 controls for actual party-level ideological polarisation, while Study 2 controls for perceived party-level polarisation on one issue (decentralisation). In the other cases, no measure of perceived party polarisation was available in the survey data, while actual party polarisation could not be measured with sufficient temporal variation to be a useful predictor. All our other analyses focus on voter-level divergence among all voters (on the aggregate level) or from the population mean (on the individual level) to capture mass ideological polarisation.

Our three studies cover three country contexts. This introduces useful temporal and geographic variation to our findings. Studies using cross-country data show that Germany and Spain are moderately affectively polarised, but the Netherlands less so (Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021). In terms of party systems, the Netherlands has many parties with a broad variety of ideological orientations, while the party systems of Germany and (with regional variation) Spain are more compact. All three countries are parliamentary systems with proportional representation, so our findings may travel less well to highly personalised systems.

Study 1: aggregate-level evidence from Germany

For Study 1, we use monthly public opinion data (known as ‘Politbarometer’) collected by the Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, a German polling organisation. Since 1988, the Politbarometer polls have been conducted by telephone (landlines only). The sample size varies by month, ranging from 908 to 7198. Here, we use monthly average values of affective polarisation, ideological polarisation, and turnout intentions for an aggregate-level analysis. We have observations of all variables since 1997.

To measure affective polarisation, we use a question that asks respondents to indicate their feelings towards each party on a thermometer ranging from −5 to +5, with −5 as ‘I strongly dislike this party’ and +5 as ‘I like this party a lot’. Measures of sympathy towards the CDU, CSU, SPD, FDP, Greens, and the PDS/Left party are included in every wave, and the AfD is included from 2013 onwards. Since the CSU and CDU compete in different parts of the country, we use whichever of the two scores is higher.

Turnout intention is asked every month in the survey using a separate question. In most months, the question asks (yes/no) whether someone would vote if an election would be held this Sunday. The format of the question and the answer are modified slightly when an election is imminent or just occurred. Answers are recoded so that those who say they would (definitely) vote are coded as 1. We then use the monthly average vote intention in our models.

We measure ideological polarisation as the standard deviation of left–right positions each month. This is asked using a standard 1–11 scale in most months; for some months, branching questions were used instead, and we remove these months from our analysis as they lead to substantially lower estimates of ideological polarisation. This reduces the period of observations for analyses including this variable to 1997–2019. To account for cycles in polarisation and turnout intentions, we include the proportional amount of time elapsed since the last election as a predictor; a squared term accounts for cyclical aspects of turnout intention.Footnote1

For the main analysis, the data were aggregated to the monthly level to create a time series trend with T = 253, which we analyse using an ARIMA model (which models both lagged and contemporaneous effects) and a VAR model (which excludes contemporaneous effects but allows for an inspection of the temporal order of affective polarisation and turnout). To replicate the findings using actual turnout in state-level elections, we re-aggregate the data to the state-election level and apply a repeated cross-sectional model with fixed effects for states. We supplement this with data about turnout and party positions on the federal level (Benoit et al. Citation2009; Gross and Debus Citation2018).Footnote2

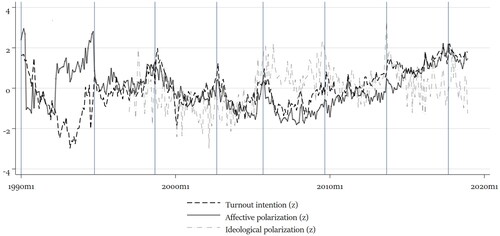

below shows the development of affective polarisation (AP), ideological polarisation (IP), and turnout since 1997. It shows, in line with Boxell et al. (Citationforthcoming), that affective polarisation has waxed and waned over time and tends to peak around elections (Hernandez et al. Citation2021). Turnout intention follows a similar election cycle. The last two decades witnessed a steady increase in affective polarisation to a level that is high (but not unique) in a historical perspective. Perhaps tellingly, turnout intention has risen with this in tandem too, even net of election cycle effects. Ideological polarisation shows no clear trend over the same recent period.

Results: country-level aggregated time series

We first model the dependent variable, turnout. A Portmanteau test of the residuals of turnout shows white noise to be obtained at 2 lags. The main independent variable, affective polarisation, is modelled with a contemporaneous effect and two lags, given that its effects are likely to play out within a couple of months. To optimise comparisons, ideological polarisation is modelled with the same lag structure. Control variables are ideological polarisation (lagged), salience of economic issues (lagged), salience of cultural issues (lagged), proportion of time elapsed since last election, and the square term of the latter (capturing increased engagement in the period before and after elections). below provides a summary ( in the Online appendices).

Table 2. ARIMA model predicting turnout.

confirms that contemporaneous affective polarisation positively predicts turnout (b = 0.022, p < 0.01), even controlling for in-party sympathy. No substantial or significant lagged effects of the same variable appear. (Increasing or decreasing the number of lags of this variable does not change this.) A replication using the weighted affective polarisation measure provides an effect of comparable size (b = 0.017), albeit significant only at the 0.10 level. Interestingly, in the Online appendices reveals no significant effect of ideological polarisation on turnout.

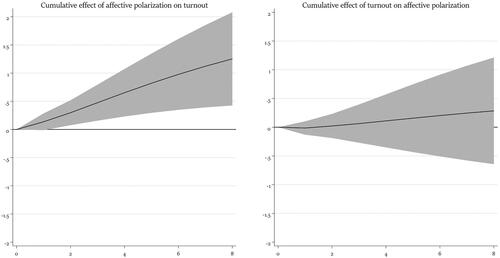

In order to explore the reciprocal interplay between affective polarisation and turnout, we turn to a VAR model. This allows estimation of the reciprocal impact through multiple equations, excluding contemporaneous effects. AIC optimisation again suggests 2 lags for the VAR model. This VAR model, which includes the same lagged control variables (including again a second for ideological polarisation), is presented in in the Online appendices. below shows its cumulative impulse response functions (CIRFs). The IRFs suggest a positive impact on affective polarisation on the subsequent development of turnout, but not the reverse. In short, the two analyses confirm a correlation between AP and turnout and suggest it is brought about particularly by the latter impacting the former.

Figure 2. Cumulative impulse response functions.

Note: Cumulative impact of unit change of X on Y, with 95% confidence intervals. Based on VAR-model presented in in the Online appendices.

Source: Politbarometer.

How are these patterns moderated by political sophistication? in the Online appendices provides the results of separate VAR models for individuals with low and high political interest (same specification otherwise). It suggests that, if anything, the clearest effects are visible among the least interested. Effects among the most interested have a somewhat smaller effect size and robustness. Affective polarisation might be especially mobilising along those who are least rather than most politically sophisticated. Neither group shows much evidence of an effect in the other direction, from turnout to affective polarisation.

Results: state-level turnout

We now turn to an analysis of the Politbarometer data to predict actual official turnout at elections at the federal state (Bundesland) level. As these do not take place simultaneously, we aggregated the original data to state-election dyads, yielding 103 observations of elections in 15 federal states. This set-up provides an opportunity to also include a measure of party (as opposed to mass) ideological polarisation—that is, the divergence in views of parties, operationalised as the standard deviation in left–right position in regional party manifestos (Benoit et al. Citation2009; Gross and Debus Citation2018). We no longer control for the left–right position as reported by respondents (as this is not clearly related to the regional level), and this increases the time span to 1990–2019.

In a regression, we predict turnout at a state-level election by the level of affective polarisation in that state in the preceding month. To explore the extent of reverse causality, we also include the lead of affective polarisation (i.e. the score in the subsequent month). If affective polarisation indeed fosters rather than reflects increased engagement, we should find the lag to have a larger effect than the lead. Because lead and lag correlate strongly within states, we model them both separately and combined. We include fixed effects for each federal state, restricting the analysis to within-state variation in turnout. We control for the closeness of the election (measured as the difference in vote share between the top-2 parties), ideological polarisation of the parties competing in the election based on their election manifesto’s (measured as the standard deviation of their left-right position), sympathy towards in-parties in the federal state (in the same wave as affective polarisation, so also either the lag or lead), and a time variable (linearly). presents the main coefficients.

Table 3. Predicting actual turnout at bundesland elections (key coefficients).

An inspection of the effect in two separate models suggests that federal states with higher levels of affective polarisation in the month preceding to the election had higher levels of turnout (at p < 0.10). Reversely, the coefficient of the lead of affective polarisation is much smaller and not significant (p = 0.74). When modelled simultaneously, the coefficients are no longer directly comparable, but it is nevertheless relevant to note that the effect size of lagged affective polarisation remains of a similar magnitude (even if it drops below conventional levels of significance) while the reverse effect disappears almost completely.

As noted, this analysis provides an opportunity to include a measure of party polarisation. As the full regression table ( in the Online appendices) shows, the divergence in positions in parties’ regional manifestos indeed has a significantly positive effect on turnout in all models. This is in line with Moral (Citation2017).

Because affective polarisation is mechanically related to in-party sympathy (straining residual variation among a mere 100 observations), we replicated the analysis without the latter variable, and this yielded a significant effect of affective polarisation on turnout (b = 0.042; p = 0.038) but not the other way around (b = 0.026; p = 0.349). Even when lag and lead are modelled simultaneously, an effect of lagged affective polarisation on turnout remains (b = 0.041, p = 0.07). In short, actual (as opposed to self-reported) turnout is, if anything, more clearly correlated with preceding than with subsequent levels of polarisation.

Are these effects again moderated by political interest? This analysis is tentative, because the number of waves around elections that includes a measure of political interest is low (42) compared to the total number of waves (101), straining a within-state analysis among 16 federal states. This replication yields no substantial or significant effects in either direction among either the lower or higher educated, and thus provides no evidence that either of the two groups would be particularly affected.

Study 2: panel data in Spain

Study 2 employs the E-DEM dataset, which is a four-wave online panel survey of the Spanish voting age population (Torcal et al. Citation2020). Its four waves were carried out over a six-month period between late October 2018 and May 2019. We restrict our analysis to the latter two waves (April and May 2019), which contain all items needed for the present analysis. The panel setup provides repeated observations at the level of individuals rather than (as in Study 1) at the level of states or Germany as a whole. Improving on Study 1, affective polarisation is measured using sympathy towards partisans (asking respondents to evaluate ‘voters of…’ various parties on a feeling thermometer from unfavourable [0] to favourable [100]) rather than parties in the abstract. As in Study 1, we calculated Wagner’s (Citation2021) unweighted affective polarisation score. Self-reported turnout intention was measured on a continuous scale from 0 (‘definitely not going to vote) to 10 (‘definitely going to vote’) (M = 8.6, SD = 2.84). In wave 3, this item referred to the national elections of April 28; in wave 4, to the European elections of May 26. As expected when comparing a first and second order election, turnout intention is slightly lower for the latter (M = 8.57) than for the former (M = 8.72). Still, both will reflect an individual’s participation intention, and hence it remains relevant to compare whether affective polarisation in wave 3 is a stronger predictor of turnout in wave 4 than vice versa.

E-DEM measures political interest on a four-point scale, of which we collapsed the lowest two categories because very few respondents (6%) indicated that they were ‘not at all interested’. We replicate the analysis using political knowledge, measured as correct relative placement of parties on a left–right scale.Footnote3 Ingroup sympathy refers to like-dislike towards supporters of the party the respondent would vote for at the upcoming election.Footnote4

Our regression models include both lagged dependent and independent variables. We predict both turnout and affective polarisation by their own lags, as well as the lagged value of the other variable. The former acts as a control and explores a temporal order. The two main variables were standardised to facilitate the comparison of effects. The models contain random intercepts for respondents.Footnote5 We control for respondents’ ideological divergence from the population mean on immigration, economy, and the Catalan issue (all lagged), as well as perceived party polarisation on the issue of decentralisation (the only such issue consistently available).

below shows the results of a panel regression, for which the full model is presented in in the Online appendices. It confirms that turnout is indeed predicted by the lag in affective polarisation. Conversely, and in line with Study 1, affective polarisation is also correlated with the lag of turnout, but to a much weaker extent and not significantly so. This conclusion holds when using the weighted measure ( in the Online appendices). Again, we find evidence that stronger affective polarisation is associated with a subsequent increase in the intention to participate in elections.

Table 4. Lagged DV panel regression predicting (1) turnout and (2) affective polarisation.

Interestingly, the effect of affective polarisation on turnout intention is more substantial than that of perceived ideological polarisation of party elites (on the issue of decentralisation), or of respondents’ own ideological divergence on immigration, the economy or the Catalan issue. None of these other variables have a significant effect on turnout intention (all p > 0.40). In short, affective polarisation appears to be more mobilising than ideological polarisation.

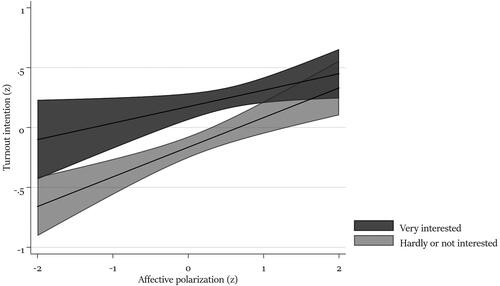

How does the effect on turnout differ by political sophistication? We interacted affective polarisation with political interest dummies ( in the Online appendices). This yielded no statistically significant interactions at conventional levels (although the model with interactions does constitute an improvement according to an F test at p < 0.01). To fully interpret this interaction effect, presents the predicted lines for the lowest (1) and highest (3) categories, with the middle category omitted for readability purposes. While the interaction is not statistically significant, it is relevant to note that an analysis of the marginal effect of political interest (visualized in in the Online appendices) suggests that the participation gap between those with low and high political interest exists only at lower levels of affective polarisation. However, a replication using political knowledge rather than interest () shows no difference between those with low and high knowledge. These models suggest, again, that the mobilising effects of affective polarisation are not restricted to the most politically sophisticated, and—if anything—are more clearly visible among those who are less interested.Footnote6

Study 3: panel data in The Netherlands

The third and final study relies on the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social sciences (LISS) panel, which is based on a true probability sample of households drawn from the population register and has been running since 2007.Footnote7 Its respondents regularly answer questions on a range of topics, including a yearly ‘Politics and Values’ battery. In total, 8205 unique individuals with non-missing observations took part during a part or the whole of the period 2008–2018.Footnote8 Compared to the Spanish E-DEM data, the LISS panel includes more waves, spanning a larger period of time, but at greater intervals (yearly). 50% of the respondents took part (with non-missing values on the key variables) at least 3 waves, and 75% took part in six waves or more (Taverage = 3.7). We employ the same lagged dependent variable model as in Study 2. LISS lacks the alternative direct measure of sympathy towards fellow citizens, instead relying (like Study 1 on Germany) on party sympathy measures, and again based on Wagner’s (Citation2021) unweighted affective polarisation score. Turnout is measured on the basis of a vote choice question (‘if elections were held today’), which includes the option ‘would not vote’. In-party sympathy refers to the like-dislike score towards the party the respondent intends to vote for (or, if none was recorded, the maximum score handed out to any party). Political interest is measured in three categories, from ‘not at all’ to ‘very’.

in the Online appendices presents the trends in affective polarisation and turnout in the Netherlands since 2007. As in Germany, affective polarisation waxes and wanes, but appears to be relatively high in recent years. Turnout has been on the rise in recent years, too. However, with the limited number of time points the aggregated data cannot provide conclusive evidence. For a more stringent test we therefore now turn to the individual level.

How does the relationship between turnout and affective polarisation play out at the individual level? below shows the results of two regressions predicting turnout and affective polarisation (in turn) by both their own and the other’s lagged value. Control variables are always included as lags.

Table 5. Lagged DV panel regression predicting (1) turnout and (2) affective polarisation.

Similar to Study 1 and 2, the coefficients provide evidence for an effect in both directions. However, replicating the same model using the weighted measure of affective polarisation ( in the Online appendices) turns its effect on turnout insignificant. This suggests that part of the mobilising effect of affective polarisation reported in is attributable to parties that are relatively small. Possibly, this reflects the highly fragmented Dutch party system, which features a plethora of small parties—some of which nevertheless appear to mobilise their opponents despite gaining only a small percentage of the vote. In that respect, a weighted measure might overlook that small parties can have a disproportionally big impact on citizens’ perceptions.

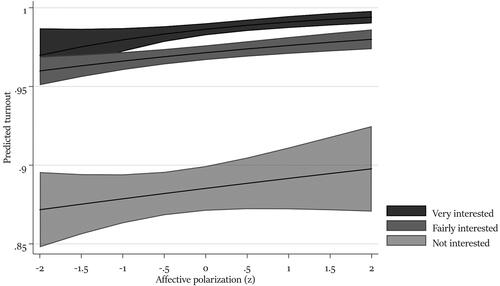

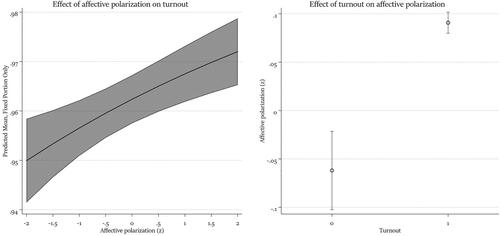

Returning to , while the coefficients present evidence for an effect in both directions, the different specifications (logistic and continuous) preclude any direct comparison of effect size based on the coefficients. To ease the interpretation of the logistic regression, visualises the effect sizes. An increase of 2 standard deviations in affective polarisation is associated with a subsequent increase in turnout of around a percentage point (which is sizeable given likely ceiling effects). Conversely, aiming to turn out to vote (rather than not) is associated with an increase of 0.15 standard deviations of affective polarisation. Again, turnout and affective polarisation influence each other, and the effect of the latter on the former appears substantially strongest.

Figure 4. Effect of AP on turnout (left) and vice versa (right).

Note: Based on standardised values of affective polarisation. Based on in the Online appendices.

How does the effect of affective polarisation compare to ideological polarisation? If we replace the ideology dummies by standardised distance towards the mean left–right position (lagged), its effect is comparable (b = 0.17) with that of affective polarisation (b = 0.18).

Finally, we analyse whether these effects differ between the more and less politically sophisticated by interacting affective polarisation with the political interest dummies (see in the Online appendices). Compared to the effect among those ‘very interested’, the effect among those ‘not interested’ is significantly smaller. However, the difference is not very substantial, as the predicted turnout for the three levels of interest (visualized in ) shows.Footnote9 Hence, taken together, our studies do not support the notion that the mobilising effect of affective polarisation is universally restricted to the highly sophisticated, but instead paint a more diverse picture.

Conclusions

While previous studied have established a positive correlation between affective polarisation and turnout using cross-sectional data on the individual level (Ward and Tavits Citation2019; Wagner Citation2021), these studies were unable to address the potentially substantial reciprocal effects, among other methodological limitations. In this paper, we therefore analysed three different sources of longitudinal data at the aggregate and individual level, spanning three countries (and up to three decades). Across these sources and specifications—each of them with their own advantages and drawbacks—a coherent picture emerges.

First, the positive correlation between affective polarisation and turnout is confirmed in each of our data sources. Importantly, this is also the case in Study 2 on Spain, where we use a more direct operationalisation of affective polarisation between citizens rather than towards parties. The finding also holds when we measure actual turnout at regional elections in Study 1 in Germany instead of relying on survey self-reports. Descriptively, elections that involve more antipathy towards political opponents also draw bigger crowds to the ballot box.

Second, our exploration of the causal direction behind this correlation suggests that the effects are indeed reciprocal. So, increases in affective polarisation are associated with a subsequent increase in turnout, and vice versa. This means that cross-sectional correlations pick up more than just a causal effect of polarisation even when controlling for confounders. At the same time, across our studies, the effects of affective polarisation on turnout were usually stronger and more robust than the reverse effects, establishing that affective polarisation does have a sizeable mobilising effect. Moreover, the effect of affective polarisation holds even when controlling for two strong potential confounders, namely (elite- and individual-level) ideological polarisation and positive partisanship.

Third, we found little evidence that the mobilising effect of affective polarisation was restricted to the most politically sophisticated. In fact, two of the three studies even suggested the opposite: that especially those who are least interested in political affairs are mobilised by affective polarisation. Possibly, affective responses to political objects draw in low-information voters more easily than do ideological differences between parties, which require more motivation, attention, and information to observe and process. It is relevant to note that we found these patterns in the aggregate-level time series in Study 1 and a continuous turnout intention scale in Study 2, which are less vulnerable to ceiling effects. In short, it appears that affective polarisation has the potential to mobilise broad swaths of society, but the exact nature of moderation by sophistication differs between contexts.

Our findings have several implications. First, affective polarisation, while widely associated with nefarious outcomes such as the erosion of democratic norms and the decline of social trust, also has a saving grace in the shape of increased participation. The increased turnout in recent elections in the US and the UK plausibly testifies that heated political debates draw citizens to the ballot box. This finding implies that group loyalties and intergroup conflict play an important role in getting people to vote.

However, the question remains whether this is categorically good news for the health of democracies. Affective polarisation’s boost to turnout appears to reflect negative partisanship (Medeiros and Noël Citation2014), as voters focus on keeping the enemies out rather than on having their vision of society represented. The resulting incumbent is then perhaps chosen less for their programme but rather for who they are not. This has unwelcome implications for accountability and representation, as electoral support becomes a negative rather than a positive endorsement of parties.

Second, the fact that mobilisation due to affective polarisation is equal across the board, and perhaps even amplified among the least politically interested, contains the opportunity to bridge participation gaps. Politics as an intergroup conflict is likely less cognitively demanding. In that sense, it is more inclusive than ideological or issue-based political competition. Past declines in turnout have usually been driven particularly by a drop among the least educated and least interested (Gallego 2009). A stabilisation or reverse in this trend due to ongoing affective polarisation might be seen as welcome, although—as noted above—it is an open question whether participation driven (mostly) by affective polarisation alone is meaningful from a normative standpoint. To the extent that affective polarisation leads to differential mobilisation between groups, this also means, very concretely, that elections held under high levels of affective polarisation will yield substantively different outcomes than those held under low levels. Future research could shed light on other groups that are especially drawn to the ballot box through affective polarisation.

Third, the reciprocal relationship between turnout and affective polarisation suggests the possibility of a spiralling effect. As societies get polarised, they draw more citizens into participating into politics, which in turn polarises them further against political opponents, and so on. In that case both affective polarisation and turnout might increase, even if remedies for some of the exogenous causes of affective polarisation (such as the high-choice media environment or negative campaigning) were to be found. This naturally raises the question of how a spiral of polarisation and participation can be broken. Perhaps periods of reduced salience of political competition are important in lowering the temperature of political debates (Hernandez et al. Citation2021).

Our findings also call for follow-up research. First, research should examine the effect of affective polarisation on other types of participation such as joining a protest or contacting politicians. For instance, affective polarisation may increase citizens’ willingness to engage in public forms of participation. Studying participation more broadly may also lend itself better to experimental research than turnout. Second, our studies could not provide evidence on the mechanisms that link affective polarisation to increased turnout. Affective polarisation may strengthen relevant negative emotions such as anger and fear (Valentino et al. Citation2011), provide expressive motivations (Huddy et al. Citation2015) and increase the perceived stakes of elections (Franklin Citation2004). Third, only parts of our three studies controlled for party-level ideological polarisation, so future work should examine in more detail the comparative impact of affective and (actual or perceived) ideological polarisation. Finally, there is a need for additional research on the ways in which less and more sophisticated citizens relate to affective polarisation. The reasons why affective polarisation mobilises may differ for those with less and greater sophistication. Here, we should study how affective polarisation in turn shapes satisfaction with the functioning of democracy and its institutions, perhaps via participation in elections that shape political outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (752.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We want to thank the anonymous reviewers of West European Politics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eelco Harteveld

Eelco Harteveld is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. His research focuses on polarisation and populism. [[email protected]]

Markus Wagner

Markus Wagner is Professor for Quantitative Party and Election Research at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. His research mainly focuses on the role of affect, issues and ideologies in party competition and vote choice. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 We also ran additional models that included a cubic term for time elapsed; including this variable did not affect our conclusions in any substantive way.

2 Around a third of the waves do not include a measure of political interest. This means that the models including that variable are restricted to a smaller sample. To assess whether this matters, we replicated the main models on this subset of waves, but this yielded virtually the same results.

3 The test was if respondents placed PSOE to the left of PP, PSOE to the left of Cs, and Podemos to the left of PSOE. The 53% of respondents who did were coded as ‘high knowledge’, the others as ‘low knowledge’.

4 Or, if no vote choice is recorded, the maximum score handed out to any of the partisan groups.

5 Respondent fixed effects are not feasible in combination with lagged dependent variables given the low T.

6 Table B2 in the Online appendices shows that no significant interaction exists between ideological polarisation (measured as divergence on the issue of immigration, given the lack of a more general measure of ideology) and political knowledge.

7 The LISS panel data were collected by CentERdata (Tilburg University, The Netherlands) through its MESS project funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. See www.lissdata.nl.

8 69% of the respondents has non-missing responses to the relevant questions for at least 3 waves; 59% for at least 4 waves; and 48% for 5 waves or more (on average 3.4 waves).

9 Table C2 in the Online appendices (model 2) again presents no evidence of an interaction between ideological polarisation and political interest.

References

- Abramowitz, Alan I. (2010). The Disappearing Center. New Heaven: Yale University Press.

- Abramowitz, Alan I., and Kyle L. Saunders (2008). ‘Is Polarization a Myth?’, The Journal of Politics, 70:2, 542–55.

- Abramowitz, Alan I., and Walter J. Stone (2006). ‘The Bush Effect: Polarization, Turnout, and Activism in the 2004 Presidential Election’, Presidential Studies Quarterly, 36:2, 141–54.

- Adams, James, and Samuel Merrill III (2003). ‘Voter Turnout and Candidate Strategies in American Elections’, The Journal of Politics, 65:1, 161–89.

- Adams, James, Jay Dow, and Samuel Merrill III (2006). ‘The Political Consequences of Alienation-Based and Indifference-Based Voter Abstention: Applications to Presidential Elections’, Political Behavior, 28:1, 65–86.

- Béjar, Sergio, Juan A. Moraes, and Santiago López-Cariboni (2020). ‘Elite Polarisation and Voting Turnout in Latin America, 1993–2010’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30:1, 1–21.

- Benoit, Kenneth, Thomas Bräuninger, and Marc Debus (2009). ‘Challenges for Estimating Policy Preferences: Announcing an Open Access Archive of Political Documents’, German Politics, 18:3, 441–53.

- Blais, André, and Agnieszka Dobrzynska (1998). ‘Turnout in Electoral Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:2, 239–61.

- Blais, André, Shane Singh, and Delia Dumitrescu (2014). ‘Political Institutions, Perceptions of Representation, and the Turnout Decision’, in Jacques Thomassen (ed.), Elections and Democracy: Representation and Accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 99–112.

- Borbáth, Enre, Swen Hutter, and Arndt Leininger (2022). ‘Cleavage Politics, Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe’, West European Politics.

- Boxell, L., M. Gentzkow, and J. M. Shapiro (forthcoming). ‘Cross-country Trends in Affective Polarization’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01160.

- Braconnier, Céline, Jean-Yves Dormagen, and Vincent Pons (2017). ‘Voter Registration Costs and Disenfranchisement: Experimental Evidence from France’, American Political Science Review, 111:3, 584–604.

- Callander, Steven, and Catherine H. Wilson (2007). ‘Turnout, Polarisation, and Duverger’s Law’, The Journal of Politics, 69:4, 1047–56.

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Caruana, N. J., R. M. McGregor, and L. B. Stephenson (2015). ‘The Power of the Dark Side: Negative Partisanship and Political Behaviour in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, 48:4, 771–89.

- Claassen, Christopher (2016). ‘Group Entitlement, Anger and Participation in Intergroup Violence’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:1, 127–48.

- Crepaz, Markus M. L. (1990). ‘The Impact of Party Polarisation and Postmaterialism on Voter Turnout: A Comparative Study of 16 Industrial Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 18:2, 183–205.

- Crepaz, Markus M. L., Jonathan Polk, Ryan Bakker, and Shane P. Singh (2014). ‘Trust Matters: The Impact of Ingroup and Outgroup Trust on Nativism and Civicness’, Social Science Quarterly, 95:4, 938–959.

- Dalton, Russell (2008). ‘The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarisation, Its Measurement, and Its Consequences’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:7, 899–920.

- Dalton, Russell (2021). ‘The Representation Gap and Political Sophistication: A Contrarian Perspective’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:5, 889–917.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Samih Çakır (2021). ‘Party System Polarisation and Electoral Behavior’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.93/Acrefore/9780190228637.013.1979.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Christoper Li (2019). ‘Partisan Affect and Elite Polarisation’, American Political Science Review, 113:1, 277–81.

- Dinas, Elias (2014). ‘Does Choice Bring Loyalty? Electoral Participation and the Development of Party Identification’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:2, 449–65.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

- Druckman, James, and Matthew Levendusky (2019). ‘What Do We Measure When We Measure Affective Polarisation?’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 83:1, 114–22.

- Edlin, Aaron, Andrew Gelman, and Noah Kaplan (2007). ‘Voting as a Rational Choice: Why and How People Vote to Improve the Well-Being of Others’, Rationality and Society, 19:3, 293–314.

- Enders, Adam M., and Miles T. Armaly (2019). ‘The Differential Effects of Actual and Perceived Polarisation’, Political Behavior, 41:3, 815–39.

- Fiorina, Morris P., Samuel A. Abrams, and Jeremy C. Pope (2008). ‘Polarisation in the American Public: Misconceptions and Misreadings’, The Journal of Politics, 70:2, 556–60.

- Franklin, Mark N. (2004). Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geys, Benny (2006). ‘Explaining Voter Turnout: A Review of Aggregate-Level Research’, Electoral Studies, 25:4, 637–63.

- Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne (2020). American Affective Polarisation in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Greene, Steven (2004). ‘Social Identity Theory and Party Identification’, Social Science Quarterly, 85:1, 136–53.

- Gross, Martin, and Marc Debus (2018). ‘Does EU Regional Policy Increase Parties’ Support for European Integration?’, West European Politics, 41:3, 594–614.

- Helbling, Marc, and Sebastian Jungkunz (2020). ‘Social Divides in the Age of Globalization’, West European Politics, 43:6, 1187–210.

- Hernandez, Enrique, Eva Anduiza, and Guillem Rico (2021). ‘Affective Polarisation and the Salience of Elections’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102203.

- Hetherington, Marc J. (2008). ‘Turned off or Turned on? How Polarisation Affects Political Engagement’, Red and Blue Nation, 2, 1–33.

- Holbein, John B., and Marcos A. Rangel (2020). ‘Does Voting Have Upstream and Downstream Consequences? Regression Discontinuity Tests of the Transformative Voting Hypothesis’, The Journal of Politics, 82:4, 1196–216.

- Holbein, John B., Marcos A. Rangel, Raeal Moore, and Michelle Croft (2021). ‘Is Voting Transformative? Expanding and Meta-Analyzing the Evidence’, Political Behavior.

- Huddy, Leonie, Lilliana Mason, and Lene Aarøe (2015). ‘Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotion, and Partisan Identity’, American Political Science Review, 109:1, 1–17.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood (2019). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarisation in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science, 22:1, 129–46.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes (2012). ‘Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarisation’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:3, 405–31.

- Jones, Philip Edward, Lindsay H. Hoffman, and Dannagal G. Young (2013). ‘Online Emotional Appeals and Political Participation: The Effect of Candidate Affect on Mass Behavior’, New Media & Society, 15:7, 1132–50.

- Lachat, Romain (2008). ‘The Impact of Party Polarisation on Ideological Voting’, Electoral Studies, 27:4, 687–98.

- Lachat, Romain (2015). ‘The Role of Party Identification in Spatial Models of Voting Choice’, Political Science Research and Methods, 3:3, 641–58.

- Mayer, S. J. (2017). ‘How Negative Partisanship Affects Voting Behavior in Europe: Evidence from an Analysis of 17 European Multi-Party Systems with Proportional Voting’, Research & Politics, 4:1, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686636.

- Medeiros, Mike, and Alain Noël (2014). ‘The Forgotten Side of Partisanship: Negative Party Identification in Four Anglo-American Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:7, 1022–46.

- Meredith, Marc (2009). ‘Persistence in Political Participation’, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 4:3, 187–209.

- Moral, Mert (2017). ‘The Bipolar Voter: On the Effects of Actual and Perceived Party Polarisation on Voter Turnout in European Multiparty Democracies’, Political Behavior, 39:4, 935–65.

- Moral, Mert, and Andrei Zhirnov (2018). ‘Issue Voting as a Constrained Choice Problem’, American Journal of Political Science, 62:2, 280–95.

- Mullainathan, Sendhil, and Ebonya Washington (2009). ‘Sticking with Your Vote: Cognitive Dissonance and Political Attitudes’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1:1, 86–111.

- Murias Muñoz, Maria, and Bonnie M. Meguid (2021). ‘Does Party Polarisation Mobilize or De-Mobilize Voters? The Answer Depends on Where Voters Stand’, Electoral Studies, 70, 102–279.

- Nemčok, Miroslav, Constantin Manuel Bosancianu, Olga Leshchenko, and Alena Kluknavská (2022). ‘Softening the Corrective Effect of Populism: Populist Parties’ Impact on Political Interest, Not Turnout, among Individuals’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2022.2089963

- Orr, Lilla V., and Gregory A. Huber (2020). ‘The Policy Basis of Measured Partisan Animosity in the United States’, American Journal of Political Science, 64:3, 569–86.

- Reiljan, Andres (2020). ‘Fear and Loathing across Party Lines’ (also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 376–96.

- Riker, William H., and Peter C. Ordeshook (1968). ‘A Theory of the Calculus of Voting’, American Political Science Review, 62:1, 25–42.

- Rogowski, Jon C. (2014). ‘Electoral Choice, Ideological Conflict, and Political Participation’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:2, 479–94.

- Rogowski, Jon C., and Joseph L. Sutherland (2016). ‘How Ideology Fuels Affective Polarisation’, Political Behavior, 38:2, 485–508.

- Sciarini, Pascal, and Andreas C. Goldberg (2016). ‘Turnout Bias in Postelection Surveys: Political Involvement, Survey Participation, and Vote Overreporting’, Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 4:1, 110–37.

- Smets, Kaat, and Carolien Van Ham (2013). ‘The Embarrassment of Riches? A Meta-Analysis of Individual-Level Research on Voter Turnout’, Electoral Studies, 32:2, 344–59.

- Steiner, Nils D., and Christian W. Martin (2012). ‘Economic Integration, Party Polarisation and Electoral Turnout’, West European Politics, 35:2, 238–65.

- Torcal, Mariano, Andrés Santana, Emily Carty, and Josep Maria Comellas (2020). ‘Political and Affective Polarisation in a Democracy in Crisis: The E-Dem Panel Survey Dataset (Spain, 2018–2019)’, Data in Brief, 32, 106059.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., and Fabian G. Neuner (2017). ‘Why the Sky Didn’t Fall: Mobilizing Anger in Reaction to Voter ID Laws’, Political Psychology, 38:2, 331–50.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Ted Brader, Eric W. Groenendyk, Krysha Gregorowicz, and Vincent L. Hutchings (2011). ‘Election Night’s Alright for Fighting: The Role of Emotions in Political Participation’, The Journal of Politics, 73:1, 156–70.

- Wagner, Markus (2021). ‘Affective Polarisation in Multiparty Systems’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102–199.

- Ward, Dalton G., and Margit Tavits (2019). ‘How Partisan Affect Shapes Citizens’ Perception of the Political World’, Electoral Studies, 60, 102045.

- Weitz-Shapiro, Rebecca, and Matthew S. Winters (2017). ‘Can Citizens Discern? Information Credibility, Political Sophistication, and the Punishment of Corruption in Brazil’, The Journal of Politics, 79:1, 60–74.

- Westfall, Jacob, John R. Leaf Van Boven, John R. Chambers, and Charles M. Judd (2015). ‘Perceiving Political Polarization in the United States: Party Identity Strength and Attitude Extremity Exacerbate the Perceived Partisan Divide’, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10:2, 145–58.

- Westwood, Sean J., Shanto Iyengar, Stefaan Walgrave, Rafael Leonisio, Luis Miller, and Oliver Strijbis (2018). ‘The Tie That Divides: Cross-National Evidence of the Primacy of Partyism’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:2, 333–54.

- Wilford, Allan M. (2017). ‘Polarisation, Number of Parties, and Voter Turnout: Explaining Turnout in 26 OECD Countries’, Social Science Quarterly, 98:5, 1391–405.