Abstract

Political participation opportunities have been expanding for years, most recently through digital tools. Social media platforms have become well integrated into civic and political participation. Using a cross-national sample from the United States, United Kingdom and France, this article examines whether acts of participation associated with social media should be classified using a traditional, five-factor solution to the structure of participatory acts. The distinction between online and offline participation is set aside, focusing instead on acts supported and enabled by social media, and in particular on differences between the use of Twitter and Facebook. The analysis shows that acts enabled by social media do not load with traditional factors in the structure of participation. Political acts employing Twitter and Facebook are distinct in the factor structure of participation.

Social media platforms have become a critical arena for civic and political participation. They are key tools in electoral campaigns, in protest events, and the creation of voluntary groups, and may help to form and promote inclusive civic behaviour, as well as strengthen participation among younger and disengaged groups (Jungherr et al. Citation2020). They are also a means for the flow of propaganda and disinformation, as well as major suspects for the increasing levels of polarisation observed in Western societies, all of which can play a significant role in mobilising but also demobilising people (Borbáth et al. Citation2022). Offering a variety of affordances and methods for content distribution, platforms can accommodate text, images and audio-visual material which can be used to encourage people to engage in politics (Bastos et al. Citation2015; Casas and Williams Citation2019). If the quality of political life depends on the quality of political participation (Verba and Nie Citation1972), then understanding how social media platforms do and do not fit with our classical understanding of participation is important for understanding contemporary democratic engagement.

One obstacle on how to understand participation associated with social media is the problem of heterogeneity among social media platforms. Social media are not simply one new communication tool, but several. In the literature, more emphasis has been placed on studying social media platforms as a group than on differentiating among them, despite the fact that the affordances of platforms with respect to political behaviour vary considerably (Bossetta Citation2018). A key finding from previous empirical work is that internet use complements traditional forms of participation (Conroy et al. Citation2012; Gibson and Cantijoch Citation2013; Ohme et al. Citation2018; Theocharis and Van Deth Citation2018). This finding implies that political use of social media tools can be well understood in terms of the classical categories of political behaviour. We suspect that there is more to the story, in part because of differences among platforms. In a systematic review of 300 studies of ‘online political participation’, Rueß et al. (Citation2021) found that platforms are rarely considered in measures of participation. This leaves unanswered empirical questions about the robustness of results across social media platforms, and more importantly it leaves open the larger question of whether political acts undertaken online are best understood as variations of existing forms of participation, or whether they should be understood as distinct.

These questions drive this study. We start with classical categorisations of political behaviour, which typically show some variation on four or five canonical modes of behaviour (Teorell and Torcal Citation2007; Verba and Nie Citation1972). We expect that some acts of political participation associated with social media cluster with one of the canonical modes of behaviour, while some do not. In approaching this expectation, we are cognisant of the fact that social media are a global phenomenon, and we are interested in the question of the factor structure of participation across countries. There has been little comparative work that examines social media platforms and participation across countries, with most studies still focussing on the US (Rueß et al. Citation2021). This means that the robustness of findings about social media and participation across countries is not clear (Boulianne Citation2019), despite the fact that a vigorous debate exists on how social media platforms affect participation around the world (Gillespie Citation2010; Wellman et al. Citation2006). We pursue a solution to classifying modes of participation associated with social media that applies beyond one country.

Our study is intended to address these goals in two main ways. First, in our survey design, we employ a thorough set of items to capture a variety of acts of political participation. We include not only the traditional acts that have anchored the participation literature since well before the digital media era, but also social media platform-enabled participation without traditional analogues (Theocharis Citation2015). This allows us to empirically position platform-based participation in the broader political participation repertoire and reassess how the presence of such platforms complements existing modes of participation or leads to the creation of new ones. To make our project tractable, we focus on Twitter and Facebook, because of their wide use and because they exemplify key differences in affordances. Second, we deploy our survey in three countries: France, the UK, and the US. These offer a useful combination of differences and similarities in participation as well as use of Facebook and Twitter (Newman et al. Citation2019). While these three countries do not stand in for a large multi-country sample, they do give us some confidence that our findings are not specific to idiosyncrasies of the US.

Categorising political participation

Verba et al. (Citation1995: 38) described participation as any activity ‘by private citizens’ that has ‘the intent or effect of influencing government action – either directly by affecting the making or implementation of public policy or indirectly by influencing the selection of people who make those policies.’ How should these activities be classified? The first influential classification scheme was Verba and Nie’s (Citation1972) four-mode scheme: voting, campaigning, communal activities, and particularised contact. Two decades later, Verba et al. (Citation1995: 38) used a comparable scheme of four modes: voting, campaign activity, citizen-initiated contacts, and cooperative participation. Other variations have been produced from factor analysis. For example, Teorell and Torcal (Citation2007: 344) produced a five-mode solution among European respondents: contacting, party activity, civic activity, protest activity, and consumerist participation, with the last two modes largely new at the time.Footnote1 This solution or something close to it is widely used both as a conceptual tool for theorising about behaviour and an empirical solution to the problem of how acts cluster (see, for example, Bäck et al. Citation2011; Barnes et al. Citation1979; Copeland and Feezell Citation2017; Gil de Zúñiga et al. Citation2014; Parry et al. Citation1992; Teorell and Torcal Citation2007; Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018; Vráblíková Citation2016; Zukin et al. Citation2006).

The primary debate in recent decades about the structure of participatory acts has focussed on the expansion to protest (Barnes et al. Citation1979; Parry et al. Citation1992), political consumerism (Stolle et al. Citation2005), and lifestyle politics (de Moor Citation2017), as well as our interest here, online participation (Hirzalla and van Zoonen Citation2011). The rapid expansion of what it means to participate in politics was noted early on (Norris Citation2002) and was followed by concerns about conceptualising an expanded set of participatory acts (van Deth Citation2001a). In two recent studies carried out with both activists and non-activists, and in which survey participants could write down participatory acts in which they engage (Theocharis et al. 2021; Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018), respondents named activities such as planting flower seeds or personalising clothes with anti-capitalist messages as forms of participation.

Critics of labelling such acts political participation can argue that political participation should include only actions clearly directed at institutions or political processes, or that have some plausibly direct potential for influencing policy or the selection of policy-makers. Clearly, expanding the concept leads to conceptual and methodological challenges (Fox Citation2014; van Deth Citation2001b). But expansive definitions of participation also shed light on how people understand themselves in political systems and how they view the boundaries of the political in everyday life. It is clear that the understanding of what it means to citizens to participate in politics changes over time (Cammaerts et al. Citation2009; Pickard Citation2019).

Especially interesting in this regard is the question of how people choose to express their political identities and preferences when presented with an expanded set of opportunities to act. This is the situation with social media, which provide a variety of affordances facilitating political acts of many kinds. Some of these acts, like sharing a petition or contacting public officials, may simply be faster and easier ways to accomplish canonical acts of participation. Other acts enabled by social media, however, have no direct analogue in the era before digital media. Examples are publicly following a political figure, posting written comments for other people, commenting on others’ posts, and forwarding political news, with or without commentary and social endorsement. Standard definitions of political participation do not address these (Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018).

This means that the uptake of social media in politics presents two possibilities for disrupting the traditional classification of participation around a five-factor structure. By making some canonical acts easier or faster, social media could elicit behaviours that cluster with one another differently than in the era before social media. More importantly in our view, use of social media presents opportunities for new kinds of acts that do not obviously cluster with offline acts on theoretical grounds. We believe that the categorisation of political participation can be improved to accommodate these possibilities.

Social media affordances and participation

The literature on online political participation has not satisfactorily addressed this classification problem. It is a common practice simply to lump ‘online’ behaviour together as distinct from ‘offline’ (Rueß et al. Citation2021). One problem with that approach is that digital media tools have changed dramatically in the last 20 years, especially in the transition from the first generation of tools centred on email, the Web, and blogs to the second-generation Web 2.0 tools centred on social networking sites, microblogs and video-sharing sites which are still expanding in use (Rueß et al. Citation2021; Smith et al. Citation2019). In an important early study of this problem, Hirzalla and van Zoonen (Citation2011) found that various online and offline activities clustered together in factor analysis and they concluded that ‘online participation’ as a theoretical construct is too ‘narrow’. The most influential study of this problem is that of Gibson and Cantijoch (Citation2013), who arrive at similar conclusions. Some online political acts, such as signing online petitions, cluster with their offline counterparts. The implication of this is that petitioning is petitioning whatever medium is employed. Other acts, they found, are distinct, reflecting ‘a more active, collective, and networked’ quality they categorise as ‘e-expressive’. While not examining social media per se, both of these studies raise the expectation that because of features that can now be considered integral to the architecture of social media platforms, some uses of social media in politics should not be classified into one of the canonical categories of participation because they possibly represent an expanded factor of participation. But what does this expanded structure look like and how can we theorise it? This is an intriguing puzzle, especially given the potential of social media platforms to facilitate both existing forms of participation and generate novel political actions which would not have been possible or feasible without them.

Social media and the role of technological affordances

A promising way to approach this puzzle is through the affordances rubric. Technological affordances are ‘the actions and uses that a technology makes qualitatively easier or possible when compared to prior like technologies’ (Earl and Kimport Citation2011: 33). Affordances have been considered at the individual, behavioural level, and at the level of political organisations (Bimber et al. Citation2012). Social media affordances are broadly considered as facilitating interactivity (Jenkins Citation2006) and promoting self-expressive participation and collaboration (Östman Citation2012: 1016; Theocharis Citation2015). While any exhaustive list of the affordances of social media would be long, subject to some debate, and vulnerable to growing outdated rapidly, existing scholarship does stress that many social media platforms share certain top-level affordances relevant to politics (Bossetta Citation2018). These include public visibility of people’s thoughts or actions, anonymity as well as identification, persistence, and automation (Bimber and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2020; Kim and Ellison Citation2021). Shared affordances between platforms are the source of what similarities exist in the social and political consequences of social media use generally. But differences in affordances of platforms are at least as important as similarities. Significant scholarly work has been devoted to depict how platform architecture could lead to differences in behaviour. Here, we first summarise the main affordances of Twitter and Facebook (two of the most popular for politics social media platforms) that are relevant for political participation, and theorise how they may impact the repertoire of participation.

Twitter is designed in such a way as to facilitate the formation and maintenance of networks based on shared interests or thin ties, without the need for mutual consent to establish a connection between people. Facebook, on the other hand, is designed to facilitate communication in networks where strong-ties are relatively more important, and where there is a stronger basis in offline relationships (Vaccari and Valeriani Citation2021). The two platforms exhibit differences in how they enable engagement and political expression and with what consequences (Bode Citation2017; Koc-Michalska et al. Citation2021; Boulianne et al. Citation2020; Towner and Muñoz Citation2018; Yu Citation2016). On the contrary, Facebook’s requirement that both persons accept ‘friendship’ before they are connected enables a different network structure for news consumption and conversational dynamics. On Twitter following decisions are one-sided and networks can scale up to very large sizes (Bossetta Citation2018). Twitter users are also ‘heavily invested in news and current events’ and almost half ‘report that their networks are much more oriented towards public figures and other users that they themselves do not know’ (as opposed to just 3 per cent on Facebook) (Duggan and Smith Citation2016: 8). This means that the public composition of Twitter might be a sufficient enough reason for some to be on the platform in order to satisfy community, social or political needs. Moreover, while following political elites or sharing a comment about politics referring to a particular actor can be done on both platforms, the asymmetric architecture of Twitter and the different audiences that Facebook and Twitter encourage people to build (e.g. strong vs. weak ties, formal vs. informal – Boczkowski et al. Citation2018; Gil de Zúñiga et al. Citation2012), mean that very different considerations might be at play when one decides to act politically in a more public manner – thus the platform matters and might even be a decisive factor of how the act comes out publicly. For example, based on a recent study by the Pew Research Centre, about 40 per cent of Twitter users in the US say that they tweet about politics (Wojcik and Hughes Citation2019), while Koc-Michalska et al. (Citation2017) report that 9 per cent of French, 16 per cent of British, and 25 per cent of Americans were using Facebook to enter posts about politics around the election time.

Twitter and Facebook, in conclusion, differ in their network structures, social capital building, methods of information consumption and proliferation, and even in the orientation of their user base towards public affairs. Research has shown that differences in such affordances can have a variety of political implications. For example, the nature of social connections between Twitter and Facebook can make a difference in the extent of bridging and bonding social capital (Shane-Simpson et al. Citation2018) and the extent of gender differences in political communication (Koc-Michalska et al. Citation2021). Compared with Facebook, Twitter users do more political posting, are exposed more frequently to counter-attitudinal political content, and are less likely to receive mobilising messages or political advertising (Vaccari and Valeriani Citation2021). To what extent these differences and similarities result in novel participatory acts or simply facilitate existing ones is an empirical question which we theorise next.

How do affordances matter in classifying behaviour?

For the present purposes of classifying behaviour, we focus on affordance differences associated with facilitating novel political behaviours. This approach has been developed by Earl and Kimport (Citation2011) who distinguish the set of affordances facilitating traditional acts (‘digitally-supported’) through greater speed, lower cost, higher precision, or greater reach, from the set of affordances that enable novel acts (‘digitally-enabled’), such as following a public figure, or posting political comments publicly. Based on both Earl and Kimport’s (Citation2011) classification and Gibson and Cantijoch’s (Citation2013) characterisation, such novel political acts facilitated by social media are distinguished by their networked and interactive character. In a more detailed conceptualisation on what makes these acts novel, Theocharis (Citation2015: 6) has described them as ‘digitally networked participation’; that is ‘networked media-based types of participation carried out with the intent to display one’s mobilisation and activate their social networks for raising awareness or exerting political pressure.’ These acts involve many affordances, for example curation of one’s own political identity and personalisation in the context of others’ networks and the properties of networked behaviour (see also Lane et al. Citation2019).

Based on this framework, there are two core sets of affordances at issue for social media and political participation. The first set is one that theoretically facilitates traditional political behaviours by making these acts faster, simpler, easier, and less costly – like, for example, the pre-Web 2.0 world wide web was able to support online petitioning or online contacting reflecting their offline versions. The second set is one that theoretically facilitates novel political actions not possible or feasible without social media technology that gives them a networked and interactive character. Existing scholarship makes clear that both Facebook and Twitter have those affordances. What is not so far theorised or empirically demonstrated is whether and how the two platforms differ in the extent to which they have those affordances, and how this might be shaping the repertoire of participation in terms of complementing existing forms or producing novel ones. Several studies have examined platform-specific political participation (Kearney Citation2017; Theocharis and Quintelier Citation2016; Vitak et al. Citation2011; Vromen et al. Citation2016), but have not explored this measure in relation to classifying modes of participation. Others that did provide classifications did not centre their enquiry around the role of affordances and only measured social media acts without platform specification, referring broadly to social media (Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018). Some studies, such as that of Vissers and Stolle (Citation2012) have distinguished online participation from political participation on specific platforms, but their study was based on youth or student samples, raising questions about whether there is a generational change in forms of participation or whether platform-specific participation is apparent across the population. Platform-specific participation was also examined as a distinct entity without considering how it relates to other online or offline forms of participation while other studies have considered platform differences, but the analysis was restricted to political expression on these platforms (Halpern et al. Citation2017; Kim et al. Citation2017; Koc-Michalska et al. Citation2021; Yu Citation2016).

Based on this theorising we conclude that, essentially, while we know that social media in general should support both novel and traditional acts, how similarly or differently the two sets of affordances work in practice to facilitate old or generate new participation remains an open question. The precise mechanism of how these sets of affordances operate to generate one or the other are likely a function of platform-specific features that are more granular, like the ability to post to more diverse Twitter networks vs. posting to more homogenous Facebook networks. How all these affordances interact with one another and with the novel/traditional behaviour distinction is not clear. We expect that use of either platform may lead to new participation modes via the novel-actions affordances.

Following this rationale, we develop a baseline hypothesis that a standard structure of participatory modes is apparent across countries in our study for traditional acts of participation. To this baseline, we add an expectation that reflects the possibility that, once social media platform-based acts are considered, these will cluster under one or more modes that are distinct not only from the traditional ones but from other, non-social media enabled online acts.

H1: Traditional acts of participation cluster together in a standard set of participatory modes consistent with the participation literature (i.e. party/campaign activity, contacting, civic engagement, protest, and political consumerism).

H2: Social media participation will cluster under one or more modes that are distinct from the traditional ones.

Data and methodology

Large-scale cross-sectional surveys with high-quality data are limited in their measures of online political participation.Footnote2 Another limitation of existing research is the absence of a comparative perspective. Few studies had been able to explore an extended repertoire of political participation using the same measures in more than one country (see, for example, Vaccari and Valeriani Citation2021), making case studies the most frequently encountered endeavours. In this study we overcome both of these limitations using a large number of offline, online and platform-enabled participatory measures within identical representative surveys run simultaneously in three countries.

Variables

The questionnaire used in the survey was specifically designed for the study. We took the idea of platform affordances especially into consideration and constructed platform-based (reduced to Facebook and Twitter) measures. We included into the analysis a wide range of political activities. Participants were asked to indicate how often in the last 12 months they had engaged in a variety of offline and online activities. Online activities included platform-specific participation as well as online acts that qualify for what Rojas and Puig-i-Abril have conceptualised as online ‘expressive participation’: forms entailing ‘the public expression of political orientations’ (2009: 906) (see online appendix ). Variables were included in the analysis as 4-item scales of frequency (never, rarely, from time to time, often).

Table 1. Internet penetration and social media usage in the US, UK, and France (percentage of users using each platform – and both – in the study sample in brackets).

Comparative scope and data collection

We test our hypotheses with data stemming from a comparative study in the US, France, and the UK. As can be seen in , the three countries have high levels of internet penetration, varying levels of Facebook and Twitter penetration as well as levels of use of these platforms for getting news (Newman et al. Citation2017). Moreover, previous literature suggests important variations in these countries’ participatory cultures when it comes to both issues and repertoires of action (Koopmans Citation1996).

Lightspeed Kantar Group administered a survey to an online panel in May (16 to 30 in France) and June (9 to 30 in UK and US) 2017. In total, 4,532 people completed the survey. Quotas were in place to ensure the online panel matched census data for each country ( in the online appendix). The sample sizes are similar across the three countries: France (n = 1521), United Kingdom (n = 1501), and the USA (n = 1510). The survey was conducted in English and French. The data was collected via an online questionnaire.

Table 2. (Step 1) Exploring modes of offline political participation (EFA; factor loadings).

Analytical strategy

We run the analysis on both the full sample (H1) and using only those participants who have access to both Facebook and Twitter (H2). For H2, we use this approach in order to not bundle together participants who do not have access to platform-based participation by virtue of not owning a Facebook or Twitter account, and those who do. It is important to note here that previous work has also shown not only that Twitter users are not representative of the general population (Blank Citation2017) but also that only a small share of Twitter users uses the platform politically – and that small group has specific characteristics (e.g. in the US it may be biased towards Democrats – Pew 2020). As our study is interested in political uses of social media, it is from the analysis of this group of politically active users that we can draw our assumptions. This procedure reduces our sample to 1080 in the pooled dataset. As indicated in , the percentage of respondents who use both Facebook and Twitter in our subsample is rather similar to those who use Twitter in the broader populations (n = 455 US, n = 381 UK, and n = 244 for France; that is, 30, 25, and 16 per cent, respectively). Thus, cases in all three countries are sufficient for country-based dimensional analysis (for full models see Tables A3–A5 in the online appendix).

Table 3. (Step 2) Exploring modes of traditional, platform-based and expressive participation (EFA; factor loadings).

In order to explore the empirical plausibility of the hypothesised structures, our analytical strategy for the modelling of the latent variables (i.e. the modes of participation) is based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factory analysis (CFA). We begin by first exploring whether the traditional five-factor solution of acts of participation (H1) materialises in our dataset by subjecting all offline participatory acts that fit our definition to EFA (step 1). We then progressively, and according to our hypotheses, add to our EFA model online forms of participation, including those based on Facebook and Twitter (H2) (step 2). We test all hypotheses for the best fit to the data and establish a ‘core’ model based on step 2. We then turn to country-specific analysis to explore whether the optimal specification acquired through EFA in step 2 is a good fit for the data when set up as a CFA model using data from each individual country. While this last step does not allow us to disentangle whether the core model is a result of technological affordances or self-selection, the comparison of three countries in which social media use for politics differs provides a first test and allows us to better understand whether assumptions about the role of platforms in political participation are led by idiosyncrasies specific to the US.

Determining the optimal number of factors to be retained in EFA is a contested issue in the literature and it is broadly accepted that there is no approach that is optimal for all cases (Finch and French Citation2015). A popular descriptive approach is to determine the number of factors via the eigenvalue greater than 1 criterion. Another is to examine the proportion of variation in the entire set of indicators that is accounted for by each factor and by a set of factors as a whole – but there, too, there is no standard solution as to what amounts for a satisfactory variance. In this study we keep an eye on the eigenvalues but are primarily guided by two criteria: the theoretical specifications hypothesised and the conventionally used absolute and relative fit indexes (TLI, CFI, RMSEA, and BIC). Moreover, due to the large number of items included in our dataset, we aim to retain only the most solid factors. For this reason, while .32 is sometimes cited as being a good rule for retaining an item (Osborne et al. Citation2008; Tabachnick et al. Citation2001), we follow the wealth of studies concerned specifically with such thresholds and which suggest that good factors should have loadings of at least .50 and ideally .70 (see, among others, Hair et al. Citation2009; Guadagnoli and Velicer Citation1988; Comrey and Lee Citation2016). We set the threshold to .50 as the minimum loading required for an item to be retained in a factor, though as can be seen in the results in almost all factors the loadings exceed the ‘ideal’ .70 illustrating a very robust solution. In the online appendix we also offer the final model with a threshold lower than .50. All analyses were run in R, using the psych package (Revelle Citation2018) for the EFA and the lavaan package for the CFA (Rosseel Citation2012).

Findings

We begin by subjecting to EFA data for all respondents (N = 4532), using only the traditional, offline participation items used in our survey. Exploring whether the well-established five-factor specification of participation holds in our data is a test of our first hypothesis, and it provides a baseline for examining how the addition of online forms of participation changes the factor structure. The resulting five-factor solution () is an excellent fit for the data (TLI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.032). Even though some modes are represented by just one activity and participating in a protest march and contacting a politician cross-load, there is a clear differentiation between (1) protest, (2) party/campaign activity (with the addition of protest march and contacting officials which cross-load in protest and contacting officials), (3) political consumerism, (4) contacting officials, and (5) civic engagement. This is consistent with the structure of participation that has been established in a score of previous studies, even though the cross-loadings point towards a tendency for marching and contacting to become integrated with institutional forms of participation connected to parties and campaigns. The message is clear. If no online activities are included, the repertoire of political participation looks mostly as one would have expected it to look based on previous work on the topic. This supports H1.

To test H2 we add to the EFA online participatory acts, including those based on Facebook and Twitter, as well as those considered as online expressive participation. The model, depicted in , is based on pooled data of social media users from all three countries (n = 1080)Footnote3 including all acts of participation. A five-factor specification is the best solution for modelling all aspects of political participation (, TLI = 0.944; RMSEA = 0.05, BIC = 1185).

This analysis presents us with a variety of novel findings. First, beginning with traditional participation, it appears that the ‘classic’ specification of five traditional modes is all but absent from our data. Party/campaign activity, contacting, and protest activities all load into a single factor with medium to high loadings (0.50–0.76). This indicates that a number of participatory acts previously clustering under the protest and party/campaign modes are here combined into what we can identify as a ‘general’ political participation mode that combines such activities. This mode also includes the online equivalents of offline acts when they exist (shown in the Table in italics), indicating that online items that directly correspond to their offline counterparts are simply extensions of offline activities. Changing one’s profile picture is often dismissed as non-participation because of its lack of a direct connection to political processes. However, surprisingly, this activity loads with other traditional acts including protesting, contacting officials, and donating to political parties.

Second, we find a clear ‘civic engagement’ mode, which is not connected directly to political institutions or government and mixes together traditional, online (e.g. online donation to NGO), and social media-based participation (e.g. following an NGO on social media – this questionnaire items did not refer to a specific platform). Third, we find a separate mode for online petitioning which, it appears, subsumes the offline act which only exhibits low loadings and is not reported in the Table.

H2 stated that social media participation will cluster under one or more modes that are distinct from the traditional ones. We do, indeed, find two separate modes: one for Twitter- and one for Facebook-based participation. Our analysis is very clear on this expectation. Participatory acts enabled by social media platforms are not only distinct from traditional modes of participation, but they are independent from one another too, loading into separate modes for Twitter and Facebook. These results hold both when we run the EFA only with those who have Facebook and Twitter accounts and when we run it with the full sample (see Table A6 in the online appendix). These findings support H2.

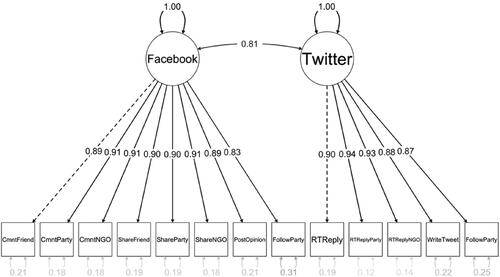

We run a separate CFA () to further depict the platform-related activities. It confirms that subjecting the Facebook- and Twitter-based items to a two-mode specification is an excellent fit to the data (CFI = 0.985; TLI = 0.982; RMSEA = 0.051).Footnote4

Figure 1. CFA of Facebook- and Twitter-based forms of participation.

Notes: Path Diagram of Facebook- and Twitter-enabled participation (CFA; Standardised Estimates). Dashed lines are fixed parameters. Darker/thicker lines indicate high correlations. N = 1.080. Model fit indexes: CFI = 0.985; TLI = 0.982; RMSEA = 0.051.

This platform-based distinction in political acts has not been previously reported, and it highlights an interesting feature of the affordances rubric that might be called the ‘affordances-users problem’. The affordances of Facebook and Twitter are different, as a matter of their design. By making different sets of actions easier, less costly, or more accessible, these platforms facilitate political behaviours that are distinct. Of particular note in this respect, for example, is that while some acts are, in principle, similar on both platforms (e.g. ‘following’ a politician or sharing political posts can be done on both Facebook and Twitter), they do not load together but rather load with other, dissimilar acts which are however carried out with the same platform. This may reflect either how a homogenous group of citizens chooses to do different things with these tools, or how different kinds of citizens adopt the tools, or both. As we discuss in the conclusion, disentangling the affordances-users problem opens up an interesting problem that is beyond the scope of the current project.

Country-based analysis

Our analysis so far employs aggregate data for all three countries. As a test of robustness of the core specification, we apply it in a CFA to the three countries individually. The fit indexes are reported in .

Table 4. Country-based CFA fit statistics table.

All fit indicators for the core model are above the conventional cut-off points when it comes to CFI and TLI, but fail in the case of RMSEA in all three cases. We interpret this as an indication of a broadly good fit for the data in all three countries.Footnote5 It is especially noteworthy that the distinction between Facebook- and Twitter-based participation is robust across countries, as is the ‘general participation’ mode.

Conclusion

Over the last two decades, digitalisation has significantly affected how people participate in civic and political activities. Social media use supports some traditional acts of participation just as it also offers entirely new forms of participation. In this study, we offer the first systematic comparative exploration of how use of two social media platforms, Twitter and Facebook, shapes the measurable factor structure of participation. While empirical political participation research has, for years, revealed that political participation is organised around five modes, our analysis suggests that there is more to the modern participatory repertoire. Activities related to political protest and political parties, formerly clustering under independent modes sharing common features of party-related and protest-related activities, in our data cluster in a mixed mode of general participation. This finding is consistent across the US, UK, and France. While this ‘mixed’ general participation mode is not in line with any of our expectations, it is not entirely surprising. Norris and colleagues (Citation2005), for example, have long noted that political protest has become ‘normalised’, and Van Aelst and Walgrave (Citation2001) have presented evidence that the socio-demographic diversity of those taking part in demonstrations is broadening, making protest a supplement to conventional forms of participation. Furthermore, the US and the UK political context in 2016–2017, characterised by polarisation, intense political antagonism and the widespread diffusion of divisive political rhetoric from platforms such as Twitter and into the public agenda, may explain the close ties between political participation and protest, but also contacting. Our data was collected in 2017, during a cycle of protest ignited by former US President Trump’s election. Those who donated to and volunteered for political parties in the November 2016 election may have continued their engagement into 2017, participating in events such as the Women’s March (January 2017; Boulianne et al. Citation2020) or inversely, participating in ‘Unite the Right’ rallies (August 2017). In the UK, we see similar patterns with protests related to Trump as well as labour strikes and environmental protests.

This mode of participation does not capture petitioning. In past studies, signing petitions was grouped with protest participation (e.g. Holt et al. Citation2013; Shah et al. Citation2007) or with marches and demonstrations (Theocharis and Van Deth Citation2018). Our findings suggest that this activity stands alone and, indeed, only in its online incarnation. Sorting out petitioning is important, as it is one of the most popular online supported political acts (Rueß et al. Citation2021). Our findings indicate that, as some previous studies have suggested (Lindner and Riehm Citation2011), petitioning – a very common and low-threshold way to engage in politics both offline and online – may have become such a specialised activity, that it has become a mode of its own. We speculate that the vast number of petitions signed today via ‘petition warehouse websites’ (Earl and Kimport Citation2011) like Avaaz or 38 Degrees and which are circulating on social media, have also opened up the kinds of topics about which people petition today, making this participatory mode a distinctive one.

We find that acts supported by the Internet and which have traditional equivalents load together with those equivalents. At the same time, acts enabled by social media platforms and which have no direct traditional equivalent do not load together, constituting distinct modes of participation. We find support for the argument that forms of participation based on social media are independent from traditional modes of participation. These activities, however, do not consist of a uniform block along the lines of a broader, ‘social media participation’. They are rather distinguished by the platform that enables them. Our findings reveal that Facebook- and Twitter-based activities are independent from one another and from the rest of the participatory forms in the measurement models. This finding holds for all three countries. As these findings are not an artefact of our data analysis (the results hold when we run the analysis with both the platform users’ sample and the full sample), they serve to stress the importance of platform affordances for political participation today, and open up a new research puzzle concerning the affordances-users problem. Indeed, we think it is important for future work to provide stronger evidence as to whether platform architecture drives these new modes of participation or whether users self-select into them to satisfy their social, community, and political needs. Existing studies point the way on how this could be done in the future. There is, for example, an existing scholarship about platform choices and how these choices reflect upon affordances (e.g. Boczkowski et al. Citation2018; Shane-Simpson et al. Citation2018) – though this scholarship is based on youth, leaving many unanswered questions about how adults compose their social media repertoires. In-depth interviews could help identify why people reason for using different platforms for political participation. Finally – and most crucially – longitudinal panel data can help tackle selection bias which tightly associated with the affordances-users problem.

As discussed in this article, the affordances literature offers strong theoretical arguments that platform architecture may be altering the underlying structure of behaviour because of each platform’s network structure, the ways in which content is mediated, its algorithmic filtering, moderation practices and the way in which each social media company quantifies user’s activities in general (Bossetta Citation2018; Theocharis et al. 2021). At the same time, a number of Pew studies have also shown that, for example, Twitter’s audience is keenly news-seeking with a tendency to pursue connection with knowledge networks. These are behaviours that are not the primary goal of Facebook users – though whether there is convergence among those politically interested using the platform remains to be empirically answered. An additional hint in this direction is that similar activities across the two platforms (such as following political elites) do not lead into having one, general social media platform-based mode of participation, indicating that perhaps platform affordances determine the ways in which citizens put these modes into political use.

These aspects of our study are important for future theory-building and for thinking about the role of social media in the field of political participation more generally. Importantly, while we are of course unable to assess the role of context with just three cases, the fact that our results are consistent across three advanced Western democracies with different political cultures but rather similar internet and social media penetration rates makes our findings potentially relevant for other European societies. Indeed, given the constantly increasing number of Facebook and Twitter users – and their usage for politics, it would be quite surprising if platform-based modes of participation were not a feature of European countries outside the set explored here.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (629.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shota Gelovani, Soyeon Jin, Andreas Jungherr, Spyros Kosmidis, Sebastian Adrian Popa, Jan W. van Deth, and Federico Veggeti for providing valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This study was funded with a grant from the Audencia Foundation, France.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yannis Theocharis

Yannis Theocharis is Professor and Chair of Digital Governance at the Department of Governance, Technical University of Munich, where he is also a member of the Munich Data Science Institute. His work focuses on political behaviour, political communication, and computational social science. [[email protected]]

Shelley Boulianne

Shelley Boulianne is an Associate Professor in Sociology at MacEwan University, Canada. She conducts research on media use and public opinion, as well as civic and political engagement, using meta-analysis techniques, experiments, and surveys. [[email protected]]

Karolina Koc-Michalska

Karolina Koc-Michalska is a Full Professor at Audencia Business School and has affiliations with CEVIPOF Sciences Po Paris, France, and University of Silesia, Faculty of Social Sciences, Poland. Her research focuses on the strategies of political actors in the online environment and citizens’ political engagement. She employs a comparative approach focussing on the United States and European countries. [[email protected]]

Bruce Bimber

Bruce Bimber is Professor in the Department of Political Science and Centre for Information Technology and Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research focuses on how the digital media context shapes collective action and public opinion. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The study did not include online forms of participation.

2 As an example, the European Social Survey includes eight items measuring political participation, with only one connected to digital technologies – added in the last round.

3 A full-sample analysis yields no substantive differences (Table A6 in the online appendix).

4 Setting the CFA model with these activities as unidimensional yields a very poor fit for the data.

5 Our findings clearly show that the core specification travels consistently across countries. Separate EFAs run for each country individually provide the exact same substantive message when it comes to modes of participation, with very minor differences across models (e.g., in the US sending political information or posting on blogs no longer load on Facebook, leaving a clear ‘Facebook mode’, while in the France boycotting loads with petition signing). These country-specific EFAs can be found in the online appendix, Tables A3–A5.

References

- Aelst, Peter, and Stefaan Walgrave (2001). ‘Who is That (Wo)Man in the Street? From the Normalisation of Protest to the Normalisation of the Protester’, European Journal of Political Research, 39:4, 461–86.

- Bäck, Hanna, Jan Teorell, and Anders Westholm (2011). ‘Explaining Modes of Participation: A Dynamic Test of Alternative Rational Choice Models’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 34:1, 74–97.

- Barnes, Samuel H., Klaus R. Allerbeck, Barbara G. Farah, Felix J. Heunks, Ronald F. Inglehart, M. Kent Jennings, Hans Dieter Klingemann, Alan Marsh, and Leopold Rosenmayr (1979). Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Bastos, Marco T., Dan Mercea, and Arthur Charpentier (2015). ‘Tents, Tweets, and Events: The Interplay between Ongoing Protests and Social Media’, Journal of Communication, 65:2, 320–50.

- Bimber, Bruce, Andrew Flanagin, and Cynthia Stohl (2012). Collective Action in Organizations: Interaction and Engagement in an Era of Technological Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bimber, Bruce, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga (2020). ‘The Unedited Public Sphere’, New Media and Society, 22:4, 700–15.

- Blank, Grant (2017). ‘The Digital Divide among Twitter Users and Its Implications for Social Research’, Social Science Computer Review, 35:6, 679–97.

- Boczkowski, Pablo J., Mora Matassi, and Eugenia Mitchelstein (2018). ‘How Young Users Deal with Multiple Platforms: The Role of Meaning-Making in Social Media Repertoires’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23:5, 245–59.

- Bode, Leticia (2017). ‘Closing the Gap: Gender Parity in Political Engagement on Social Media’, Information, Communication and Society, 20:4, 587–603.

- Borbath, Endre, Swen Hutter, and Arndt Leininger (2022). ‘Introduction: Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe’, unpublished manuscript.

- Bossetta, Michael (2018). ‘The Digital Architectures of Social Media: Comparing Political Campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S’, Election’, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 95:2, 471–96.

- Boulianne, Shelley (2019). ‘Revolution in the Making? Social Media Effects across the Globe’, Information, Communication and Society, 22:1, 39–54.

- Boulianne, Shelley, Karolina Koc-Michalska, and Bruce Bimber (2020). ‘Mobilizing Media: Comparing TV and Social Media Effects on Protest Mobilization’, Information, Communication and Society, 23:5, 642–64.

- Cammaerts, Bart, Michael Bruter, and Shakuntala Banaji et al. (2009). ‘The Myth of Youth Apathy: Young Europeans’ Critical Attitudes Toward Democratic Life’, American Behavioral Scientist, 58:5, 645–664.

- Casas, Andreu, and Nora Webb Williams (2019). ‘Images That Matter: Online Protests and the Mobilizing Role of Pictures’, Political Research Quarterly, 72:2, 360–75.

- Comrey, Andrew L., and Howard B. Lee (2016). A First Course in Factor Analysis (2nd edition). London: Routledge/Psychology Press.

- Conroy, Meredith, Jessica T. Feezell, and Mario Guerrero (2012). ‘Facebook and Political Engagement: A Study of Online Political Group Membership and Offline Political Engagement’, Computers in Human Behavior, 28:5, 1535–46.

- Copeland, Lauren, and Jessica T. Feezell (2017). ‘The Influence of Citizenship Norms and Media Use on Different Modes of Political Participation in the US’, Political Studies, 65:4, 805–23.

- De Moor, Joost (2017). ‘Lifestyle Politics and the Concept of Political Participation’, Acta Politica, 52:2, 179–97.

- Duggan, Maeve, and Aaron Smith (2016). The Political Environment on Social Media. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre.

- Earl, Jennifer, and Katrina Kimport (2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Finch, W. Holmes, and Brian F. French (2015). Latent Variable Modeling with R. New York: Routledge.

- Fox, Stuart (2014). ‘Is It Time to Update the Definition of Political Participation? Political Participation in Britain: The Decline and Revival of Civic Culture’, Parliamentary Affairs, 67:2, 495–505.

- Gibson, Rachel, and Marta Cantijoch (2013). ‘Conceptualizing and Measuring Participation in the Age of the Internet: Is Online Political Engagement Really Different to Offline?’, The Journal of Politics, 75:3, 701–16.

- Gil De Zúñiga, Homero, Lauren Copeland, and Bruce Bimber (2014). ‘Political Consumerism: Civic Engagement and the Social Media Connection’, New Media & Society, 16:3, 488–506.

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Nakwon Jung, and Sebastián Valenzuela (2012). ‘Social Media Use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17:3, 319–36.

- Gillespie, Tarleton (2010). ‘The Politics of ‘Platforms’, New Media & Society, 12:3, 347–64.

- Guadagnoli, Edward, and Wayne F. Velicer (1988). ‘Relation of Sample Size to the Stability of Component Patterns’, Psychological Bulletin, 103:2, 265–75.

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Bill Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis. Seventh Ed. London: Pearson.

- Halpern, Daniel, Sebastián Valenzuela, and James E. Katz (2017). ‘We Face, I Tweet: How Different Social Media Influence Political Participation through Collective and Internal Efficacy’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22:6, 320–36.

- Hirzalla, Fadi, and Liesbet van Zoonen (2011). ‘Beyond the Online/Offline Divide: How Youth’s Online and Offline Civic Activities Converge’, Social Science Computer Review, 29:4, 481–98.

- Holt, Kristoffer, Adam Shehata, Jesper Strömbäck, and Elisabet Ljungberg (2013). ‘Age and the Effects of News Media Attention and Social Media Use on Political Interest and Participation: Do Social Media Function as Leveller?’, European Journal of Communication, 28:1, 19–34.

- Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

- Jungherr, Andreas, Gonzalo Rivero, and Daniel Gayo-Avello (2020). Retooling Politics: How Digital Media Are Shaping Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kearney, Michael W. (2017). ‘Interpersonal Goals and Political Uses of Facebook’, Communication Research Reports, 34:2, 106–14.

- Kim, Dam Hee, and Nicole Ellison (2021). ‘From Observation on Social Media to Offline Political Participation: The Social Media Affordances Approach’, New Media and Society. Available Online at, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444821998346

- Kim, Yunhwan, Silvia Russo, and Erik Amnå (2017). ‘The Longitudinal Relation between Online and Offline Political Participation among Youth at Two Different Developmental Stages’, New Media & Society, 19:6, 899–917.

- Koc-Michalska, Karolina, Gibson Rachel, and Thierry Vedel (2017). Social Media and French Society. Internet and Social Media during the 2017 French Presidential Election: A Comparative Perspective (No. 44). Paris: CEVIPOF Sciences-Po.

- Koc-Michalska, Karolina, Anya Schiffrin, Anamaria Lopez, Shelley Boulianne, and Bruce Bimber (2021). ‘From Online Political Posting to Mansplaining: The Gender Gap and Social Media in Political Discussion’, Social Science Computer Review, 39:2, 197–210.

- Koopmans, Ruud (1996). ‘New Social Movements and Changes in Political Participation in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 19:1, 28–50.

- Lane, Daniel S., Slgi S. Lee, Fan Liang, Dam Hee Kim, Liwei Shen, Brian E. Weeks, and Nojin Kwak (2019). ‘Social Media Expression and the Political Self’, Journal of Communication, 69:1, 49–72.

- Lindner, Ralf, and Ulrich Riehm (2011). ‘Broadening Participation through E-Petitions? An Empirical Study of Petitions to the German Parliament’, Policy & Internet, 3:1, 63–85.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (2019). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (2017). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford. Retrieved from: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital News Report 2017 web_0.pdf?utm_source=digitalnewsreport.organdutm_medium=referral.

- Norris, Pippa (2002). Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, Stefaan Walgrave, and Peter Van Aelst (2005). ‘Who Demonstrates? Antistate Rebels, Conventional Participants, or Everyone?’, Comparative Politics, 37:2, 189–205.

- Ohme, Jakob, Claes H. de Vreese, and Erik Albaek (2018). ‘From Theory to Practice: How to Apply Van Deth’s Conceptual Map in Empirical Political Participation Research’, Acta Politica, 53:3, 367–90.

- Osborne, Jason W., Anna B. Costello, and J. Thomas Kellow (2008). ‘Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis’, in Jason Osborne (ed.), Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. New York: Sage, 86––102.

- Östman, Johan (2012). ‘Information, Expression, Participation: How Involvement in User- Generated Content Relates to Democratic Engagement among Young People’, New Media & Society, 14:6, 1004–21.

- Parry, Geraint, George Moyser, and Neil Day (1992). Political Participation and Democracy in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pew Research Center (2020). ‘Differences in How Democrats and Republicans Behave on Twitter’. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/10/15/differences-in-how-democrats-and-republicans-behave-on-twitter/.

- Pickard, Sarah (2019). Politics, Protest and Young People: Political Participation and Dissent in 21st Century Britain. London: Springer.

- Revelle, William R. (2018). Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA.

- Rosseel, Yves (2012). ‘Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modelinge Human Forearm during Rythmic Exercise’, Journal of Statistical Software, 48:2, 1–36.

- Rueß, Christina, Christian Pieter Hoffmann, Shelley Boulianne, and Katharina Heger (2021). ‘Online Political Participation – the Evolution of a Concept’, Information Communication and Society, 1–18.

- Shah, Dhavan V., Jaeho Cho, Seungahn Nah, Melissa R. Gotlieb, Hyunseo Hwang, Nam-Jin Lee, Rosanne M. Scholl, and Douglas M. McLeod (2007). ‘Campaign Ads, Online Messaging, and Participation: Extending the Communication Mediation Model’, Journal of Communication, 57:4, 676–703.

- Shane-Simpson, Christina, Adriana Manago, Naomi Gaggi, and Kristen Gillespie-Lynch (2018). ‘Why Do College Students Prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site Affordances, Tensions between Privacy and Self-Expression, and Implications for Social Capital’, Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 276–88.

- Smith, Aaron W., Laura Silver, Courtney Johnson, Kyle Taylor, and Jingjing Jiang (2019). Publics in Emerging Economies Worry Social Media Sow Division, Even as They Offer New Chances for Political Engagement. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre.

- Stolle, Dietlind., Marc Hooghe, and Michele Micheletti (2005). ‘Politics in the Supermarket: Political Consumerism as a Form of Political Participation’, International Political Science Review, 26:3, 245–69.

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., Linda S. Fidell, and Jodie B. Ullman (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Teorell, Jan, and Mariano Torcal (2007). ‘Political Participation: Mapping the Terrain’, in Jan W. Van Deth, José Ramón Montero, and Anders Westholm (eds.), Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge, 334–57.

- Theocharis, Yannis (2015). ‘The Conceptualization of Digitally Networked Participation’, Social Media and Society, 1:2, 1–14.

- Theocharis, Yannis, Ana Cardenal, Soyeon Jin, Toril Aalberg, David Nicolas Hopmann, Jesper Strömbäck, Laia Castro, Frank Esser, Peter Van Aelst, Claes de Vreese, Nicoleta Corbu, Karolina Koc-Michalska, Joerg Matthes, Christian Schemer, Tamir Sheafer, Sergio Splendore, James Stanyer, Agnieszka Stępińska, and Václav Štětka (2021). ‘Does the Platform Matter? Social Media and COVID-19 Conspiracy Theory Beliefs in 17 Countries’, New Media and Society, 1–26. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14614448211045666

- Theocharis, Yannis, Joost Moor, and Jan W. Deth (2021). ‘Digitally Networked Participation and Lifestyle Politics as New Modes of Political Participation’, Policy & Internet, 13:1, 30–53.

- Theocharis, Yannis, and Ellen Quintelier (2016). ‘Stimulating Citizenship or Expanding Entertainment? The Effect of Facebook on Adolescent Participation’, New Media & Society, 18:5, 817–36.

- Theocharis, Yannis, and Jan W. van Deth (2018). ‘The Continuous Expansion of Citizen Participation: A New Taxonomy’, European Political Science Review, 10:1, 139–63.

- Theocharis, Yannis, and Jan W. van Deth (2018). Political Participation in a Changing World: Conceptual and Empirical Challenges in the Study of Citizen Engagement. New York: Routledge.

- Towner, Terri L., and Caroline Lego Muñoz (2018). ‘Baby Boom or Bust? The New Media Effect on Political Participation’, Journal of Political Marketing, 17:1, 32–61.

- Vaccari, Cristian, and Augusto Valeriani (2021). Outside the Bubble: Social Media and Political Participation in Western Democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Van Deth, Jan W. (2001a). Studying Political Participation: Towards a Theory of Everything?. ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Grenoble.

- Van Deth, Jan W. (2001b). Studying Political Participation: Towards a Theory of Everything? Joint Sessions of Workshops of the European Consortium for Political Research, Grenoble.

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Verba, Sidney, and Normon H. Nie (1972). Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Vissers, Sara, and Dietlind Stolle (2012). ‘Spill-over Effects between Facebook and on/Offline Political Participation? Evidence from a Two-Wave Panel Study’, Canadian Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Panel: New Media Use among Citizens and Parties, Edmonton.

- Vitak, Jessica, Paul Zube, Andrew Smock, Caleb T. Carr, Nicole Ellison, and Cliff Lampe (2011). ‘It’s Complicated: Facebook Users’ Political Participation in the 2008 Election’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14:3, 107–14.

- Vráblíková, Kateřina (2016). What Kind of Democracy? Participation, Inclusiveness and Contestation. London: Routledge.

- Vromen, Ariadne, Brian D. Loader, Michael A. Xenos, and Francesco Bailo (2016). ‘Everyday Making through Facebook Engagement: Young Citizens Political Interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States’, Political Studies, 64:3, 513–33.

- Wellman, Barry, Anabel Quan-Haase, Jeffrey Boase, Wenhong Chen, Keith Hampton, Isabel Díaz, and Kakuko Miyata (2006). ‘The Social Affordances of the Internet for Networked Individualism’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8:3, 0

- Wojcik, Stefan, and Adam Hughes (2019). Sizing up Twitter Users. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre.

- Yu, Rebecca Ping (2016). ‘The Relationship between Passive and Active Non-Political Social Media Use and Political Expression on Facebook and Twitter’, Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 413–20.

- Zukin, Cliff, Scott Keeter, Molly Andolina, Krista Jenkins, and Michael X. Delli Carpini (2006). A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.