?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Radical right parties (RRPs) have gained representation in parliaments across Europe, but little is known about their impact on government policy. Even though RRPs tend to end up in opposition, they have considerable influence on policy making within coalition governments. One expectation is that coalition governments are tough on immigration to optimise voter support when being exposed to right-wing parties in parliament. Coalition negotiations temporarily reduce accountability and allow cabinets to adjust policy positions without bearing the costs associated with opportunistic behaviour. This argument is tested using novel data on pre-electoral policy positions and post-electoral immigration policies for coalition cabinets in 24 European democracies from 1980 to 2015. The findings reveal that governments shift to more restrictive immigration policies in face of RRPs. This article expands on prior research on the influence of the radical right by demonstrating its direct influence on coalition governments’ joint immigration policy plans.

Do radical right parties influence coalition government policy? Right-wing and populist challenger parties have established themselves within a range of European party systems. While mainstream parties suffer dramatic electoral losses, radical right parties such as the German Alternative für Deutschland, the Danish Folkeparti or the Austrian Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs are on the rise. More recently, scholars started to investigate how these parties – albeit mostly being in the opposition – have affected the policy positions of established parties (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Meguid Citation2005; Spoon and Klüver Citation2019) or the attitudes of voters (Bischof and Wagner Citation2019). Relatedly, prior research also shows the impact of extreme parties on immigration policy change (Abou-Chadi Citation2016b; Folke Citation2014; Howard Citation2010; Schain Citation2006; Williams Citation2006). In addition, several studies explore the direct and indirect effects of the radical right on mainstream party positions (see Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Han Citation2015; Krause and Matsunaga Citation2023; van Spanje Citation2010). We contribute to this literature by conducting a novel test of the impact of RRP representation on changes in the joint policy agenda of coalition governments.

Specifically, we show that coalition governments shift to more restrictive immigration policies in their joint agreements whenever radical right parties are represented in parliament during cabinet formation. All parties pay close attention to the distribution of voter preferences (Downs Citation1957). Once they recognise a preference shift among the electorate, parties adapt their positions in order to maintain electoral support (Adams et al. Citation2004; Ezrow et al. Citation2011). Scholars of party behaviour have examined this process of ‘policy optimisation’ and found varying strategies of adjustment. Adams et al. (Citation2006) show that mainstream parties respond to shifts in the general population while niche parties pay special attention to preference changes among their core support groups. Klüver and Spoon (Citation2016) similarly find that mainstream parties respond to issue priorities of the overall population while niche parties mostly respond to their own supporters.

But open policy shifts do come at a cost, as parties face a range of restrictions which constrain their behaviour (Meyer Citation2013; Tavits Citation2007). Voters, and especially partisan supporters, closely monitor programmatic changes (Cox and McCubbins Citation1986; Ezrow et al. Citation2011) and have a desire for credible signals of policy stability. A party that changes its positions regularly and substantially has a hard time to convincingly commit to policy adherence in the future. Accordingly, Tavits (Citation2007) shows that opportunistic shifts on salient policy issues result in electoral penalties. Political parties therefore try to strategically balance regular adaptation to preference changes in the electorate with avoiding to appear as ‘flip-floppers’.

Research also shows that established parties pay attention to new contenders (Meguid Citation2005) and there exists a growing interest in the way emerging right-wing challenger parties provoke mainstream party reactions (see Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Han Citation2015). RRPs emerged in political arenas throughout Europe and built their success on a combination of anti-elitist rhetoric and nationalist policy positions (Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997; Mudde Citation2007; Williams Citation2006). These parties have also politicised new ‘cultural’ issues (Kriesi et al. Citation2006), with a special emphasis on anti-immigration policies (Dancygier Citation2010). When facing successful radical right challengers, mainstream parties often react with an accommodative strategy (Meguid Citation2005; van Spanje Citation2010).

In this article, we focus on the influence of radical right parties during the formation of multiparty coalitions. Cabinet parties can use confidential coalition negotiations – a period of low accountability and clarity of responsibilityFootnote1 – to optimise their positions on immigration without bearing the usual costs associated with policy change on salient issues. In the face of RRPs represented in parliament, cabinet parties propose more restrictive immigration policy positions in their coalition agreements. We test our argument based on a unique dataset covering 165 coalition formations in 24 West and East European party systems between 1980 and 2015. Our analysis makes use of a novel data that combines positions derived from coalition agreements with pre-electoral positions from party manifestos (Volkens et al. Citation2018). We provide more information on the origin of the agreements in Online Appendix Section 1.2.

Our approach is unique since we combine party positions of government parties extracted from their pre-electoral manifestos with data on policy positions of coalition governments that originate from their post-electoral coalition agreements. The coalition agreements are usually negotiated shortly after the election and are published only a few weeks after voters have cast their ballot, which enables us to track policy change over an exceptionally short period of time. We can reasonably assume that position changes of government parties are barely affected by exogenous, time-varying confounders. And since the election manifestos and the coalition agreements are analysed using a similar coding procedure, we can moreover assess the magnitude and direction of policy adjustment during coalition negotiations on precisely the same ideological scale.

To test our hypothesis on immigration policy optimisation during coalition negotiations, we analyse how much the coalition agreement positions (CAPs) deviate from pre-electoral expected positions (EPs) that we generate on the basis of Gamson (Citation1961). We find that RRP presence in parliament, a symbol of support for extreme-right politics among the electorate, is a significant predictor of shifts towards more restrictive policies. A range of additional analyses show that this effect is not primarily driven by the size of radical challenger parties or their initial entry to parliament. We then explore how attributes of the incoming government moderate the effect. While the general ideological alignment of a cabinet or the duration of its formation does not appear to impact policy change, we find that minority cabinets, and cabinets which have lost electoral support, are more likely to shift towards restrictive policies. In a final series of robustness tests, we show that coalition cabinets exposed to RRPs in parliament are quite similar to those without right-wing pressures across a range of important covariates.

Overall, the empirical analysis provides evidence showing that coalition cabinets confronted with RRPs in parliament adopt significantly more restrictive immigration policy positions than those without similar exposure. Our findings have two main implications. First, we are going beyond prior research by highlighting the impact of RRPs on coalition cabinets. In particular, we provide evidence for the role of coalition negotiations as windows of opportunity for unpunished policy optimisation in face of pressures by the radical right. Rational, vote-seeking cabinet parties can accommodate to more restrictive positions while avoiding to appear opportunistic. Second, we show that the success of radical right parties does have an immediate effect on government policy. Compared to positions drafted just a few weeks or months before the elections, cabinets take on significantly harsher positions in their joint agreements when RRPs are represented in parliament. Overall, we contribute to the literature on policy positioning in contested multi-party systems and existing research on consequences of right-wing party success for immigration policy in advanced democracies.

Radical right party performance and immigration policy change

In this study, we test if the presence of radical right parties in parliament impacts the policy agendas of coalition governments. More specifically, we observe changes in immigration policy, a highly salient and contested issue area that is closely linked to radical right challengers (Dancygier Citation2010). Our argument builds on existing work that highlights the influence of the radical right on immigration policy. For example, Schain (Citation2006) traces the development of the ‘Front National’ in France and shows how its electoral success causes realignment of existing parties. In a comparative framework, Howard (Citation2010) showcases that the strength of far-right parties is the most relevant predictor of naturalisation processes across EU members. Relatedly, Abou-Chadi (Citation2016b) shows that the politicisation and electoral competition of the immigration issue is a pivotal vetopoint for more progressive immigration policies. And in a quasi-experimental study on Swedish municipal elections, Folke (Citation2014) provides a causal assessment of the influence of RRP representation on stricter immigration policy.

Beyond analysing the impact of RRPs on general immigration policy, prior research has also demonstrated their effect on other parties. For example, van Spanje (Citation2010), Abou-Chadi (Citation2016a) and Han (Citation2015) show accommodative behaviour and ‘contagion’ effects for mainstream parties and parliamentarians across established democracies. In a similar vein, Abou-Chadi and Krause (Citation2020) implement a RD-design to provide causal evidence on the impact of RRPs on mainstream parties’ immigration positions, also finding accommodation effects among the establishment. Going beyond the assessment of radical parties’ impact on their competitor’s positions, Krause and Matsunaga (Citation2023) show that accommodative strategies of the establishment do not pay off electorally. We contribute to this literature by shifting the attention away from individual party responses to reactions by entire coalition cabinets.

For sake of comparability, our conceptualisation of RRPs follows established standards set by scholars in the field. We identify RRPs based on their critical stance towards mainstream immigration policy (see Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Roodujin et al. Citation2019). We conceive of radical and populist right-wing parties as challengers of established mainstream parties because they threaten them electorally (Abou-Chadi Citation2016b; De Vries and Hobolt Citation2020; Howard Citation2010). While mainstream parties suffer dramatic electoral losses in recent years, radical and populist right parties such as the German Alternative für Deutschland, the Danish Folkeparti or the Austrian Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs are on the rise.

Radical right-wing parties exert pressure on mainstream parties by mobilising on the immigration issue and employing anti-establishment rhetoric to undermine mainstream party legitimacy (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2020; Mudde Citation1999; Schain Citation2006). One core claim is a demand for more restrictive migration laws (Brug & Van Spanje Citation2009). Often, these claims are combined with populist appeals and the usage of racist stereotypes (Mudde Citation2007). Thus, we argue that RRPs exert ‘ownership’ over the immigration issue by demanding to ‘go tough’ on immigration (see Abou-Chadi Citation2016b; Howard Citation2010; Schain Citation2006). Since immigration policy has become increasingly contentious and highly politicised in recent elections, radical and populist right-wing parties frequently benefitted from a mobilisation on this issue (Dancygier Citation2010; Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997). As challengers, they did so by attracting voters from established parties across the traditional left-right dimension (McGann and Kitschelt Citation2005; Rydgren Citation2008).

We therefore argue that successful radical and populist right parties pose an electoral threat to coalition governments. The presence of RRPs signals to coalition parties that a sizable part of the electorate prefers more restrictive immigration policies. In an effort to appeal to these voters, we expect that coalition governments have strong incentives to adopt harsher policies on immigration. However, one central caveat we propose is that governments are not able to freely reposition themselves on such a salient issue. Flip-flopping will result in credibility losses and penalisation, especially by dedicated core supporters (Ezrow et al. Citation2011). In the next section, we lay out how the blurred lines of responsibility during confidential coalition negotiations can provide governing parties with an opportunity to update their policy positions without having to bear the negative consequences of position adjustment. After developing our argument on why mainstream parties should make use of coalition negotiations to update their policy agenda, we conduct an empirical test. We provide evidence which shows that cabinets shift towards more restrictive positions if they have been exposed to a RRP in parliament.

Policy optimisation during coalition negotiations

We hypothesise that coalition parties will settle with more restrictive policies in their coalition agreements compared to the policy positions they proposed in pre-electoral campaign manifestos if they face RRPs in parliament. That is, because the coalition formation stage provides an ideal opportunity for government parties to adjust their policy agenda in light of recent election results without bearing electoral costs.

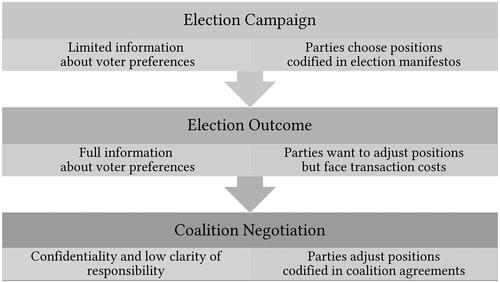

We conceive of policy optimisation during the coalition cabinet formation as a three-stage process (see ). First, we assume that parties are rational, goal-oriented and purposeful collective actors interested in maximising their own electoral support (Downs Citation1957). Following the spatial proximity model, we then assume that the main instrument to maximise electoral support is strategic position-taking along a set of salient policy dimensions (Stokes Citation1963).

The spatial proximity model also posits that political parties carefully analyse the distribution of voter preferences (Enelow and Hinich Citation1984). Voters are expected to support the party whose policy programme most closely aligns with their individual preferences on the issues they deem relevant. Since voter preferences change regularly over time (Converse Citation1964; Pedersen Citation1979), parties are incentivised to constantly monitor and respond to shifts in the electorate (Adams et al. Citation2004; Schumacher, de Vries, and Vis Citation2013). Thus, we think of party competition as a dynamic system in which parties adapt their positions to changing voter preferences (see Stimson, Mackuen, and Erikson Citation1995; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010; Adams et al. Citation2004).

At the same time, political parties are also held accountable, especially by their core supporters. Ezrow et al. (Citation2011) have contrasted the general electorate model, which focuses on vote maximisation among all voters, with the partisan constituency model, according to which parties pay special attention to the preferences of their closest followers. Political parties rely on a stable and committed group of activists for the maintenance of local party infrastructure, volunteering, and campaigning. According to the ‘core supporter model’ parties therefore are more responsive towards this small group and do not risk scaring them off (Cox and McCubbins Citation1986). Since these core supporters pay special attention to policies (Schumacher, de Vries, and Vis Citation2013), changes to the official party stances on salient matters like immigration can likely trigger attention and anger. Activists, who are typically driven by ideological motives, will abandon overly opportunistic parties (Bernhardt, Duggan, and Squintani Citation2009). Thus, open position adjustment can be a costly strategy that undermines electoral support.

Political parties need to balance popular demand and core supporter ideology when defining their policy positions before elections, as depicted in stage one of . They first draft election manifestos in which they lay out their ideological stance. These manifestos are the most encyclopaedic statements of parties’ policy programmes and set the guidelines for the ensuing campaigns, potential coalition negotiations and for future legislative activity (Budge Citation1987; Eder, Jenny, and Müller Citation2017). But parties have to create their manifestos in a context of incomplete information about actual voter preferences. Guessing how the positions found in the manifestos will resonate with the electorate is hard because the preceding election is only a poor indicator of current voter preferences (Somer-Topcu Citation2009).

Polls are used by political elites for decision making (e.g. Pickup and Hobolt Citation2015), but are at best a crude indicator of voter preferences. They deliver an estimate of voting intentions at the time of their execution that comes with sampling error, measurement error, and is influenced by subjective weighting decisions (see Hudson et al. Citation2004). Recent evidence moreover shows that increasing electoral volatility in multi-party systems and the emergence of new political actors, such as RRPs, have further elevated ambiguity over final election outcomes (Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016; Prosser and Mellon Citation2018).

It is only through election results – shown at stage two of – that parties receive complete information about voter preferences. Therefore, we conceive of election outcomes as information signals on voters’ preferred policy positions (Abou-Chadi and Orlowski Citation2016; Budge Citation1994). All political parties receive direct feedback on the popularity of their pre-electoral policy propositions. In an environment without transaction costs, we would expect all parties to immediately optimise positions based on their performance at the ballot. But parties are constrained since open change of policy positions can undermine their credibility and support.

We argue that participation in coalition negotiations, the third stage highlighted in , constitute an exception from this rule. In multiparty systems, more than one party typically forms a coalition government since no single party gains a legislative majority. Coalition governments are composed of at least two political parties that share executive offices (Strøm, Müller, and Bergman Citation2008: 6). Governing in coalitions can be intricate. Even though coalition parties join forces to gain control over executive offices, they typically pursue different policy objectives. Before entering government, coalition parties therefore engage in lengthy coalition negotiations that typically last a few weeks to bargain over the allocation of ministerial portfolios as well as over their joint policy agenda that is then written down in a public coalition agreement (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Strøm, Müller, and Bergman Citation2008). These negotiations are often labelled as a ‘black box’ since the bargaining process is highly confidential.

We argue that these coalition negotiations provide an excellent opportunity for cabinet parties to optimise their positions in face of RRPs. Cabinet parties can profit from being responsive by aligning their propositions to preferences of the general electorate and accommodate to RRP positions without bearing the costs associated with open position switching. This is because coalition negotiations create a context of low accountability during which position switching cannot be traced back to individual actors.

Position switching during negotiations is also appealing as it allows parties to enshrine their compromise in their joint coalition agreement. The agreements have implications for actual policy making throughout the government’s term in office. Even though coalition agreements are not legally binding, they define policy priorities of a cabinet and constrain the behaviour of each coalition party. While coalition negotiations are secret, the coalition agreements are publicly released, which enhances the compliance as shirking will lead to public blaming and shaming. Accordingly, Thomson (Citation2001), Moury (Citation2011) and Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik (Citation2014) show that election pledges to which coalition governments commit themselves in their joint agreements are significantly more likely to be fulfilled throughout the legislative term than pledges that are not mentioned.

Why are coalition agreements effectively constraining coalition parties? In line with prior research, we argue that there are essentially two reasons why coalition parties stick to the positions of the coalition agreements: office costs and electoral costs. Not complying with the policy commitments negotiated in the agreement typically results in intra-cabinet conflict and may ultimately lead to early cabinet breakdown so that coalition parties would lose control over executive offices earlier than necessary (Saalfeld Citation2008; Krauss Citation2018). In addition, potential future coalition partners will not risk cabinet stability by forming a coalition with unreliable parties. Hence, defecting from the coalition agreement can also result in significant future office costs as coalition partners lose their credibility (Saalfeld Citation2008; Tavits Citation2008). Finally, shirking from the negotiated coalition agreement can inflict significant electoral costs as parties can be publicly blamed as an unreliable coalition partner that jeopardises cabinet stability and as a party that does not keep its promises (Saalfeld Citation2008). Inducing instability to the political system is typically punished by constituents.

In total, blurring policy shifts during coalition negotiations allows cabinet parties to appease both of their reference groups. They manage to adjust their policy positions to the general population – which is pivotal to maintain electoral support at upcoming elections – without alienating their core supporters (Ezrow et al. Citation2011). Coalition parties can sell shifts as a necessary compromise to the latter group while ensuring that their policy propositions find broader support among all voters. In addition, the coalition agreement allows parties to codify their new consensus in a publicly recognised and quasi-binding joint coalition agreement.

RRPs and cabinet immigration policy shifts

Our research speaks to the literature on the policy influence of radical right parties and the more general literature on the dynamics of coalition formation in multiparty systems. We assess the influence of RRPs on immigration policy during a pivotal stage of government formation: The coalition negotiation period. Prior research shows that the presence of radical challenger parties in parliament constitute a signal of discontent with the immigration policies of established mainstream parties. Scholars in the field show that establishment parties react to these challengers, even after their initial entry to parliament (e.g. Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020). Simultaneously, we know from the party competition literature that open repositioning – especially on such a salient issue like immigration – can be a costly strategy that undermines trust and potentially scrutinises valuable core supporters of establishment parties. We argue that coalition negotiations provide an ideal space to circumvent this dilemma. The confidentiality of negotiations allows cabinet parties to deviate from their pre-electoral propositions without taking on personal blame. However, their unified cabinet position is codified in the coalition agreement. These agreements are a common, quasi-binding contract that lays out the government’s agenda over the legislative period and ensures mutual control.

We argue that coalitions should make use of this opportunity for policy shifts during negotiations. In particular, we expect that cabinets exposed to radical right parties utilise the period of reduced accountability to shift towards more restrictive immigration policies in their joint agreement compared to cabinets that form without exposure to RRPs in parliament. That is because the presence of RRPs is understood as a credible challenge to the establishment parties, especially on the issue of immigration. Our main hypothesis captures this intuition:

Hypothesis:When radical right parties are represented in parliament during the coalition formation period, coalition governments shift to more restrictive immigration policies in their coalition agreement relative to their pre-electoral propositions.

Research design and data

In order to test our theoretical argument, we rely on a newly compiled dataset on pre- and post-electoral positions of coalition governments on immigration policy that we derive from political texts. We combine pre-electoral positions of government parties extracted from their election manifestos with post-electoral policy positions obtained from their coalition agreements. Since coalition agreements usually are published only a few weeks after voters have cast a ballot, we are able to investigate policy shifts in a unique setting where we can keep most time-varying confounders constant. To test our argument about policy changes during coalition negotiations, we are assessing how actual government positions derived from the joint agreements deviate from expected pre-electoral positions that we generate on the basis of Gamson (Citation1961).

In the following section, we first discuss the measurement of pre- and post-electoral cabinet positions on immigration. Afterwards, we discuss how we operationalise our independent variable, RRP presence in parliament, before concluding with a summary of our data and empirical strategy.

Measuring government policy change around elections

We rely on quantitative text analysis to measure government policies on immigration. To do so, we exploit the fact that coalition governments negotiate and publish a coalition agreement which lays out the policy programme of the cabinet in detail (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Klüver, Bäck, and Krauss Citation2023; Müller and Strom Citation2003). Even though coalition agreements are not legally binding, they constrain the behaviour of cabinet members because non-compliance is publicly scrutinised. For example, Moury and Timmermans (Citation2013) demonstrate that coalition agreements severely confine ministers since the agreements codify their policy agenda for the upcoming legislature. Similarly, Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik (Citation2014) show that pledges included in coalition agreements are significantly more likely to be fulfilled throughout the legislative term. Accordingly, Strøm, Müller, and Bergman (Citation2008: 170, emphasis in original) argue that coalition agreements are ‘the most binding, written statements to which the parties of a coalition commit themselves, that is, the most authoritative document that constrains party behaviour’. Klüver and Bäck (Citation2019) and Klüver, Bäck, and Krauss (Citation2023) have shown that coalition agreements are comprehensive policy documents which cover a wide variety of issues and particularly settle policies that are divisive and salient to coalition parties. The agreements are publicly presented by the entire cabinet which takes collective responsibility for the negotiated policy compromise.

In order to measure a government’s immigration policy based on coalition agreements, we rely on the immigration-related policy content identified by human expert coding (see Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Klüver, Bäck, and Krauss Citation2023). Trained country experts divided the agreements into quasi-sentences and assigned each quasi-sentence to a specific policy category. The authors have designed their coding scheme in accordance with the established Manifesto Project codebook (Volkens et al. Citation2018) and conducted various reliability and validity checks (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Klüver, Bäck, and Krauss Citation2023).

Comparable to prior studies (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Klüver and Bäck Citation2019), we obtain the immigration-specific policy positions by subtracting the relative number of ‘liberal’ from ‘restrictive’ statements included in the coalition agreement. Unlike election manifestos, coalition agreements do not solely talk about policies, but also about the allocation of ministerial offices and about procedural rules (see Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Strøm and Müller Citation1999). We therefore rely on scaling processes that are able to derive at positions solely based on policy-related information in the text. We first adopt the relative proportional difference scale (or Kim/Fording scale) developed by Kim and Fording (Citation1998):

(1)

(1)

CAP(Kim/Fording)i refers to the coalition agreement position of coalition government i. For the Kim/Fording scale, coalition agreement positions are calculated by subtracting the absolute number of liberal statements (L) from the number of restrictive statements (R) on immigration policy and then dividing the number by the total number of statements related to immigration. We consider ‘National Way of Life: Negative’ (qs602) and ‘Multiculturalism: Positive’ (qs607) as liberal categories, whereas ‘National Way of Life: Positive’ (qs601) and ‘Multiculturalism: Negative’ (qs608) are restrictive (see Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020). In case an agreement does not contain statements about immigration we are assigning a central position in the full sample. Importantly, we also present results of regression analyses run on a restricted sample, where cabinets that did not talk about immigration policy are left out, instead of retrieving a centre position.

The scale ranges from −1 to 1, where negative values denote liberal positions and positive values indicate restrictive immigration policy positions. This measure only takes policy-related quasi-sentences into account. It is therefore suitable for comparisons between different types of political documents that deviate in terms of length or structure, as long as they contain substantive content on policy. Thus, the Kim/Fording scale allows us to directly compare immigration policy positions from coalition agreements with those adopted in election manifestos.

In addition to the Kim/Fording scale, we also estimate positions based on the Logscale, as described by Lowe et al. (Citation2011). Their scaling method also relies on the relative balance of restrictive (R) versus liberal (L) statements within each document. The exact equation is as follows:

(2)

(2)

CAP(log)i again refers to the coalition agreement position of coalition government i. The log scale is calculated by dividing the log-value of all restrictive statements R by the log-value of all liberal statements L. 0.5 is added in the nominator and denominator to enable a calculation of the natural logarithm in the absence of policy statements. Just as before, we consider ‘National Way of Life: Negative’ (qs602) and ‘Multiculturalism: Positive’ (qs607) as liberal categories, whereas ‘National Way of Life: Positive’ (qs601) and ‘Multiculturalism: Negative’(qs608) count as restrictive. This method produces a symmetrical interval scale that is not bound by predefined minimum and maximum values.

In order to check the validity of our CAPs as proxies of actual government action, we investigate how they correspond with migration policies adopted during the legislative term. We merged our data with an extensive dataset on migration policy changes that we obtain from DEMIG (Citation2018) (more details can be found in the Online Appendix). Appendix Section 5.2 shows that more restrictive expected positions and coalition agreement positions on immigration indeed result in higher legislative activity on immigration and substantial changes towards more restrictive immigration policy.

Measuring expected positions on immigration policy

In order to identify policy changes, we also require a pre-electoral measure of government positions on immigration policy. We construct a measure of expected positions on immigration policy following the logic of Gamson (Citation1961). The expected positions are estimated on the basis of election manifestos. Political parties draft manifestos in which they lay out their policy programme in various policy fields. The party programmes are published shortly before an election in the context of limited knowledge about current voter preferences. Since manifestos entail detailed information on future policy plans, these documents constitute a perfect reference point against which to compare post-electoral positions stated in coalition agreements (Budge and Klingemann Citation2001).

As already noted, the content analysis of the coalition agreements closely followed the coding protocol of the Manifesto Project. The substantive policy content of coalition agreements can be directly compared to content found in election manifestos (Volkens et al. Citation2018). The Manifesto Project itself is one of the most comprehensive and widely used data sources to analyse policy positions of parties over time. Election programmes are coded by trained country experts which divide the platforms into quasi-sentences before classifying those statements according to a predefined coding scheme (Budge and Klingemann Citation2001; Volkens et al. Citation2018).

To extract parties’ pre-electoral positions on immigration policy from their manifestos, we calculate individual positions for each cabinet party according to the same scaling procedures that have been described before based on the number of quasi-sentences promoting liberal immigration policies (qs602 and qs607) and the statements that propose more restrictive policies (qs601 and qs608). Pre-electoral positions are therefore measured on the same scales (Kim/Fording and Log-scale) as post-electoral coalition agreement positions, where positive values denote restrictive positions and negative values constitute liberal positions. We again assign centrist positions to those coalitions that do not mention immigration policy in their party manifestos in the full sample. For the restricted sample, cabinets without mentions of immigration policy are omitted.

Our estimation strategy relies on the difference between the actual immigration position adopted by coalition governments in their coalition contract with their pre-electoral expected immigration position. To arrive at a unified expected government position, we build on perhaps the strongest empirical regularity in political science, the famously denoted ‘Gamson’s Law’. Gamson (Citation1961: 376) argued that parties forming a coalition government would each get a share of ministerial portfolios that is proportional to the legislative seats that each party contributes to the coalition. Numerous empirical studies have found overwhelming empirical support by showing that there is a nearly perfect relationship between a coalition party’s seat contribution to the government and its quantitative allocation of cabinet portfolios (see e.g. Browne and Franklin Citation1973; Browne and Frendreis Citation1980; Schofield and Laver Citation1985; Warwick and Druckman Citation2006). As Laver (Citation1998, p. 7) notes, Gamson’s proposition has produced ‘one of the highest non-trivial R squared figures in political science (0.93)’.

Gamson’s law can however not only reliably predict the portfolio allocation, but also the policy position that coalition governments negotiate in coalition talks (Warwick and Druckman Citation2001). It is therefore standard procedure that scholars measure the policy positions of coalition governments following the prediction of Gamson’s law by weighting the positions of individual coalition parties by the share of seats that they contribute to the government (see Martin and Vanberg Citation2014). This weighted average, or ‘coalition compromise’ (Martin and Vanberg Citation2014), is a simple yet powerful proxy commonly used to operationalise government positions in multiparty cabinets (Grofman Citation1982; Powell Citation2000). Expected coalition positions on immigration policy are calculated as follows:

(3)

(3)

The expected position on immigration policy (EP) for coalition government i is constructed by summing the positions of all cabinet parties j weighted by their respective cabinet seat share sij. Again, we also calculate the expected position on immigration policy based on the log-scale according to the following formula:

(4)

(4)

In Online Appendix Section 6.3, we confirm that these expected positions are highly correlated with positions weighted by a cabinet’s portfolio allocation (Correlation = 0.91; p < 0.001). In an additional robustness check in Online Appendix Section 6.3, we also replicate our main analysis using these portfolio-weighted positions. There, we show that utilising seat shares instead of the portfolio distribution does not change our results.

Following Gamson’s law (Gamson Citation1961), we assume that the expected position (EPs) derived from manifestos are strong predictors of the coalition agreement positions (CAPs). Both measure the same phenomenon, immigration policy, on exactly the same scale based on a comparable content analysis of political texts which are usually drafted just a few months apart. Given the short time span we are also confident to rule out a multitude of exogenous confounders. Bivariate regressions presented in Online Appendix Section 5.1 provide strong empirical support for our assumption. The expected position on immigration policy that we scale based on the pre-electoral manifestos is a major predictor of the actual immigration position that coalitions adopt in their coalition agreement.

Operationalisation of independent variables

We rely on two independent variables in order to test our theoretical argument that coalition governments adopt more restrictive immigration policies when RRPs are present in parliament.

First, the main analysis utilises the dummy variable RRP Parliament, which captures if a radical right party has gained representation at a given election. Obtaining parliamentary representation constitutes a strong signal aimed at more established parties (Bischof and Wagner Citation2019). As a consequence, mainstream parties are facing RRPs in their daily parliamentary work. Once elected into the legislature, right-wing challengers also receive additional resources and media attention which increases the threat that they constitute for established parties (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020). Therefore, we expect coalition governments to respond by adopting more restrictive immigration policies. Empirically, we find that right-wing challengers gain representation in 61% of all coalition formation instances observed in our sample. This ensures that there is sufficient variation within the sample, suggesting that not every cabinet formation we observe occurs with exposure to a radical party in parliament. We consider parties that display strong nationalist and anti-immigration positions as right-wing challengers. The classification is based on prevalent work in the field, most importantly by Mudde (Citation2007) and Roodujin et al. (Citation2019). For Eastern Europe and recent elections, we also consulted election reports and related studies (e.g. Bustikova Citation2014). Online Appendix Section 1.1 lists all RRPs covered in our analysis.

Additionally, we add the second independent variable RRP Vote Share to some models. It is a continuous measure of the combined vote share of all radical right parties. We utilise the continuous measure of RRP prevalence to assess if exposure to larger right-wing challengers has a more pronounced effect on immigration position change. This would imply that it is not the mere presence of challengers, but their electoral dominance that should trigger policy optimisation during negotiations. We do not have strong ideological priors on the expected results. That is because Abou-Chadi and Krause (Citation2020) have already produced convincing causal evidence that small RRPs, just above the electoral threshold, can influence positions of mainstream parties. Certainly, a larger RRP should signal more support for anti-immigration propositions and thus could induce larger changes during the negotiations. On the other hand, a large RRP might reduce the uncertainty about the appeal of anti-immigration propositions among the general electorate prior to the election day. That is because a right-wing challenger polling at around 15% or more of the popular vote is very likely to be represented in parliament after the elections. If uncertainty about the appeal of tough positions on immigration is low prior to the election, establishment parties could already account for them in their pre-electoral party programmes. This could reduce their potential for adaptation during the cabinet formation period.

Data and estimation

Our analysis investigates the effect of radical right parties on coalition government’s immigration policy change during their formation. We aim to observe if cabinets that form while being exposed to RRPs in parliament shift to more restrictive immigration positions than other coalition cabinets.

We therefore compiled a novel dataset based on pre- and post-electoral positions for 165 coalition cabinets across 24 Western and Eastern European democracies between 1980 and 2015. For the selection of countries, we followed the established standard in coalition research (see Andersson, Bergman, and Ersson Citation2014). The countries in our sample include Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. This country sample is characterised by variation in several institutional features, which strengthens the external validity of our findings.

With regard to the collection of coalition agreements, we build on the work by Klüver, Bäck, and Krauss (Citation2023). The authors have compiled an extensive dataset on the policy content of coalition agreements across Europe. Crucially, they have assessed the documents for coherence and comparability. For example, the authors ensured that each agreement fulfils certain criteria (i.e. the discussion of specific policy plans for the legislature or the public backing by all cabinet parties) and their country experts were trained to ensure validity and reliability. To this data, we add the information on election results and the representation of RRPs from ParlGov (Döring and Manow Citation2018), as well as pre-electoral manifesto positions based on the Manifesto Project (Budge and Klingemann Citation2001; Volkens et al. Citation2018).

To test our hypothesis on immigration policy optimisation during coalition negotiations, we then assess how the post-electoral coalition agreement positions deviate from the pre-electoral expected positions that we generate on the basis of Gamson (Citation1961). By studying the difference between expected positions based on pre-electoral election manifestos with actual government positions adopted in coalition agreements, we measure policy change within an extremely short time span. This not only makes it possible to restrict the influence of time-varying confounders. The following equation represents our main specification with a differenced outcome variable:

(5)

(5)

We are interested in the change in immigration policy position of government i in country c at year t as the dependent variable. This is represented by ΔPositioni,c,t, which is the difference between a government’s pre-electoral expected position (EP) and the post-electoral coalition agreement position (CAP). Note that positive values indicate a change towards more restrictive, and negative values indicate a move towards less restrictive policy positions during cabinet formation. The dependent variable thus captures the dynamics of the position change rather than the absolute position at any given time point.

The key explanatory variable of interest is RRP Parliament, a dummy variable that indicates the presence of RRPs in parliament. The coefficient β1 on this variable captures the average difference in immigration policy position change associated with the presence of an RRP in parliament, relative to when an RRP is not present, holding other variables constant.

To account for invariant confounding across countries and time trends, we add ac,t, representing country (c) and cabinet formation year (t) fixed effects, respectively, in our specification. These fixed effects control for unobserved heterogeneity that may affect immigration policy positions, holding constant cross-country differences and time trends such as the general political climate, institutional factors, or macroeconomic conditions. By doing so, we ensure that our coefficient of interest, β1, captures the within-country, within-year variation attributable to the presence of radical right parties (RRPs), thereby making our estimates more robust to omitted variable bias.

In addition to the state and year fixed effects, we also include Xi,c,t, a vector of cabinet-specific control variables. This includes the absolute number of cabinet parties (as a measure of the complexity of negotiations), a dummy that denotes minimum-winning coalitions (which are the most common form of coalitions, instead of minority or super-majoritarian cabinets) and the national unemployment rate during the year of cabinet formation as a measure of general economic conditions. Even though our estimation strategy relies on the analysis of a broad set of available data on coalition formation in Europe, the time series cross section analysis is demanding due to the limited number of country-cases and time points. The results therefore can come with a degree of statistical uncertainty. Finally, all standard errors are clustered by country and descriptive statistics are presented in Online Appendix Section 2.

Empirical analysis

In , we present the first empirical test of our argument. We run a series of regression models that rely on a differenced outcome measure and include country and year fixed effects and clustered standard errors by country. The dichotomous RRP Parliament dummy acts as the independent variable. For the differenced outcome variable, positive values denote a change towards more restrictive policy positions, while negative values indicate a change towards more progressive positions on immigration. Again, these changes typically occur over a few weeks around election day. We run separate regressions for the full sample of cabinets (n = 165) and a restrictive sample (n = 132) that excludes cabinets which did not explicitly state policy positions in either party manifestos or the coalition agreement.

Table 1. Policy change for RRPs in parliament.

For all models of , we observe that the entry of radical right parties into government is associated with a move to more restrictive policy positions during the coalition negotiation phase. In three of four models, this association is significant above conventional levels of statistical uncertainty. Importantly, the effect of radical right party presence in parliament on shifts to more restrictive immigration policy is highly robust once we restrict the sample to those 132 cabinets that did cover migration policy in both their election programmes and joint agreements. The coverage of immigration by establishment parties in their policy platforms indicates a heightened salience of this issue. In terms of effect magnitude, we find policy shifts of 0.4 to 0.7 points on the Kim/Fording scale – with a theoretical maximum of 2 points – to be quite substantial. A maximum change of 2 points would constitute a change from the most extreme permissive pre-electoral position to the most extreme restrictive post-electoral agreement position. Again, we observe this change over the short time span between drafting electoral programmes and negotiating the joint coalition agreement.

In a second step, we add RRP Vote Share, the vote share of all radical right parties, as an additional independent variable to test if position change becomes more pronounced once radical challengers gain larger vote shares. According to the results presented in , we find that the size of RRPs does yield larger policy shifts. If anything, bigger challengers appear to lead to marginally less restrictive change. However, most estimates are not significantly discernible from zero.

Table 2. RRP size and policy change.

Why would mere exposure to RRPs, but not their size influence a cabinet’s immigration plans? Providing conclusive evidence on this finding is beyond the scope of our article. However, one plausible explanation could be that establishment parties try to cater towards RRP supporters as long as they remain marginal competitors. The accommodative behaviour of mainstream cabinets might be a viable strategy as long as the radical competitors are small (Meguid Citation2005). Once RRPs have established themselves in the party system and become major competitors for offices, mainstream parties could opt for differentiation in order to sharpen their own policy profiles. In line with this proposition, Abou-Chadi and Krause (Citation2020) have presented convincing causal evidence on the accommodative behaviour of mainstream parties in response to small RRPs that barely entered parliament around the electoral threshold.

Cabinet characteristics and the influence of RRPs

After showing that coalition governments change their position on immigration policies when facing radical challengers in parliament, we now explore what cabinet characteristics could influence the effect. In particular, we focus on four coalition attributes that could shape the degree of policy influence by RRPs.

First, we assess whether the electoral performance of a cabinet moderates the influence of RRPs on policy change. One could expect that cabinets which have lost votes are prone to pressures from the radical right. We thus create the binary variable Electoral Loss to indicate if cabinet parties have on average lost votes compared to the previous election. A value of one shows that the cabinet has experienced an electoral loss. Next, we focus on the general ideology of a cabinet as a potential moderator. Here, one could assume that especially centre-right governments are prone to pressures from radical parties because they are more likely to lose supporters to the far right. To differentiate between left and right-leaning governments, we create the binary variable Left Cabinet. We measure cabinet ideology based on the weighted average position on the general left-right scale (or ‘rile’-scale) of each cabinet parties’ manifesto. Cabinets with an average ideology score lower than 0 are coded as being left cabinets. Third, we suggest that the length of the coalition negotiations themselves could impact the influence of RRPs on policy changes. We thus have researched the length between the election date and government formation, measured in days. We have been able to retrieve information on the formation duration for 161 out of 165 cabinets in the full sample and 128 of 132 cabinets in the restricted sample. In the next step, we conduct a median split to create the binary indicator Long Negotiation. Longer negotiation periods should exert cabinet parties with a longer time period of implicit pressure from the radical right while providing them with more opportunities to shift their policies. Finally, we focus on the coalition type itself. Minority cabinets do not possess the parliamentary strength to implement legislation alone, thus making them rely on parts of the opposition for policy making. This could make them more prone to shift towards restrictive policies in order to establish support along the line of immigration policy.

We replicate the prior OLS regression models, but interact each of the binary cabinet characteristics with the RRP Parliament dummy variable. We measure policy shifts on the Kim/Fording-scale and again include cabinet control variables, country and year fixed effects in the models. The standard errors are clustered by country. The results are presented in .

Table 3. RRP influence by cabinet characteristics.

The first two models paint an inconclusive picture of the moderating effect of cabinet’s electoral performance. In the full sample, the significant interaction terms suggest that losing cabinets are more likely to adjust their position. However, in the restricted sample, the coefficient of the interaction is smaller and lacks statistical significance. We interpret this as suggestive, but not conclusive evidence for the proposition that cabinets that did lose electorally are more prone to accommodative strategies in light of the radical right. For the remaining three cabinet-specific moderating variables, the analyses provide more consistent results. Looking at cabinet ideology, the insignificant interaction terms showcase that left-leaning cabinets are neither more nor less likely to amend their position in the face of RRPs. The direction of the effect is negative, suggesting that left-leaning cabinets shift towards more progressive positions compared to right-leaning coalitions. While the direction of the interaction effect aligns with our theoretical intuition, the estimates are not statistically significant.

The same is true for the findings regarding government formation duration. Lengthy negotiations in face of RRPs are not associated with more or less intense policy position changes. The coefficients in models five and six are close to zero and lack statistical precision. Finally, we observe positive estimates for the interaction between RRP presence and the minority cabinet dummy. Minority cabinets, which are more reliant on opposition party support, do shift to significantly more restrictive positions whenever RRPs are represented in parliament. This suggests that RRPs are especially influential of government policies when the coalition cabinet itself has no strong electoral mandate.

Overall, the empirical analyses provide ample support for our theoretical argument. Coalitions perceive the presence of right-wing challengers as a signal of refusal for their prior positions on immigration policy. They immediately react by adopting a tougher stance on immigration in comparison to those governments without similar exposure. In addition, we present complementing evidence on the role of RRP size and their influence conditional on cabinet characteristics. In the auxiliary analyses, we find that larger RRPs do not have stronger influence on the degree of policy change than smaller RRPs in parliament. This aligns with prior research showing that even small radical right challenger parties can influence their competitors once they gain representation. With regard to the cabinet characteristics, we find some evidence that those coalitions under electoral are switching towards more restrictive policies. In particular, minority coalition cabinets and cabinets that lost votes show accommodative behaviour in face of RRPs.

Further robustness and validity checks

In the last empirical section, we summarise supporting evidence on the relationship between radical challengers and coalition governments’ policy change on immigration during negotiations. We probe if cabinets with and without exposure to RRPs are comparable within our sample. We conduct two tests showing that both groups do not differ along relevant characteristics.

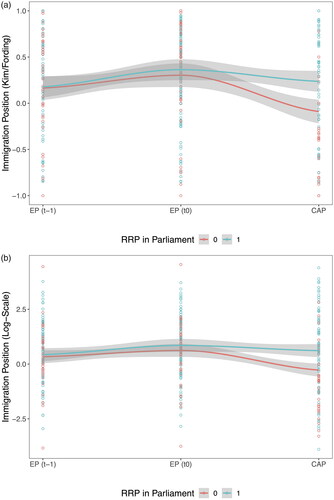

First, visualises the similarities of their pre-electoral positions. The plots depict a coalition cabinet’s immigration position across three time points: The post-electoral coalition agreement position CAP, the pre-electoral expected position EP(t0), and the expected position at the prior election EP(t-1). Crucially, we observe no differences across both groups when moving from EP(t-1) to EP(t0). Only in the coalition agreement positions that are drafted after the elections, significant differences between positions taken on by cabinets with and without RRP exposure occur. This pattern holds for the Kim-Fording scale on the upper pane, as well as the log scale on the lower pane of the figure.

Figure 2. Immigration policy positions across cabinets.

Note: The figure shows trends in immigration positions for cabinets with RRPs in parliament in green and cabinets without exposure to RRPs in red. We observe that there are no significant differences across both groups for the pre-electoral EPs at the current election (t0) or at the preceding election (t-1). Significant differences only emerge for post-electoral coalition agreement positions.

Second, we explore if the cabinets diverge along a set of other relevant dimensions. We therefore conducted a range of t-tests to check their balance on potentially relevant covariates. summarises the results. For each variable, we showcase the average value for cabinets with and without RRP presence in parliament. The balance column then indicates if significant differences across both groups exist according to a two-tailed t-test (cutoff at p < 0.05).

Table 4. t-Tests showing similarities across coalition cabinets.

Generally speaking, both groups of cabinets are very comparable. We do not observe significant differences with regard to national levels of migrant inflow during the year of their formation, coalition type (i.e. minority or super-majoritarian coalitions instead of the common minimum-winning coalition), their electoral performance measured as changes in the vote share across two consecutive elections, their ideological stance along the general left-right ‘rile’ scale, their duration in power, or their location in Eastern Europe.

We only find one dimension in which treatment and control group differ: Parliaments in which RRPs gain presence house approximately one more party, as measured by the effective numbers of parties measure (Laakso and Taagepera Citation1979). We think that this imbalance poses no severe concern regarding systematic differences. When RRPs enter parliament, they typically extend the political landscape and thus drive up the measure of parliamentary parties.

Besides highlighting the similarities across cabinets with and without RRP exposure to probe for potential confounders, we conducted a series of further robustness and validity checks. In Section 5.2 of the Online Appendix, we validate that the coalition agreement positions relate to actual policy changes by using the DEMIG dataset which tracks immigration policy change. We confirm the relevance of the policy contents in the agreements and find that restrictive coalition agreement positions translate into policy changes during the government’s term in office. Next, in Online Appendix Section 6.1, we show that the positive effect of RRP presence in parliament persists even when we control for their first entries. The first entries of RRPs appear to have a slight ancillary effect on policy shifts, but the coefficients are small and statistically insignificant. The general presence of RRPs in parliament during cabinet formation on the other hand remains a robust substantial and significant determinant of immigration policy change. Next, we provide additional evidence in Online Appendix Section 6.2 that our results hold if we allow for cross-country variation in our models. We do so by removing the country fixed effects and find that our results remain largely unchanged. Finally, Online Appendix Section 6.3 shows the robustness of our results if we adjust the weighting procedure and rely on portfolio allocation shares instead of seat shares to calculate the pre-electoral expected positions. In total, the contributing evidence provides further support of coalition cabinets’ shifts towards restrictive immigration positions in light of radical right challenger parties.

Conclusion

Radical right parties are increasingly successful contenders in elections across Europe, but little is known about their influence on policy making in coalition governments. Given that a majority of European countries are governed by multiparty coalitions, we make use of coalition agreements as a novel data source to track policy shifts around elections by comparing pre-electoral to post-electoral government positions in 24 Western and Eastern European democracies from 1981 until 2015. We find that coalition cabinets systematically adopt more restrictive immigration policies when they form in the face of a radical right party represented in parliament. In additional analyses, we present evidence that in particular coalitions under some electoral pressure are prone to larger immigration policy shifts. We find that minority governments, and to a lesser degree, governments that have lost electoral support are more responsive to RRP exposure in parliament. Conversely, the vote share of RRPs or their initial entry do not seem to have an additional significant effect.

We explain our finding with a theoretical argument of strategic policy optimisation during coalition negotiations. We have argued that coalition governments go tough on immigration in order to optimise voter support in light of the electoral threat imposed by right-wing challenger parties. This is part of the ‘accommodative’ strategy highlighted by prior research in the field (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2020; Meguid Citation2005). In order to maximise their appeal to the electorate and safeguard their future vote share, coalition cabinets that face successful right-wing contenders adopt more restrictive immigration positions than governments that form without an RRP presence in parliament. Coalition negotiations, as low-information environments, allow cabinet parties to adjust positions on immigration policy without bearing the costs typically associated with opportunistic policy shifts.

Our findings have important implications for understanding the influence of radical right parties on policy making by coalitions across various European democracies. The analysis presented in this study shows that governments adopt more restrictive immigration policies when faced with electorally successful radical and populist right parties. Even though radical right parties usually end up in the opposition, they have considerable influence on policy making. Thus, RRPs do not have to formally enter the government, but they can shape immigration policies merely due to the electoral pressure which they impose on established parties.

Our analysis also sheds light on the role of coalition negotiations as windows of opportunity for policy adjustment more generally. We argue that strategic, rational cabinet parties which seek to maximise electoral support for their policy propositions should be inclined to make adjustments in response to changing voter preferences. Coalition negotiations happen confidentially and behind closed doors, creating an environment of low accountability for each individual party. We show that cabinet parties use this context by adopting a position in the coalition agreement that is different from those stated in their campaign manifestos. Cabinet parties can appeal to popular positions in the general electorate while avoiding punishment by their own core supporters. Thus, our study shows that coalition negotiations allow parties to update their policy positions in response to changes of general voter preferences and that they actually shift their position when the costs of ‘flip-flopping’ are low.

While this study has contributed to our understanding of the effect of radical right parties on governments and for responsiveness in coalition government policy more generally, there are a number of open questions. Most importantly, we see that policy adjustment takes place during coalition negotiations but we still lack evidence for the success of this strategy. For many established parties, switching preferences has not prevented electoral decline in the long run (Spoon and Klüver Citation2019). And even in the short-run, ad hoc adjustments to challenger positions might be questionable advice. We ask ourselves whether the accommodative strategy of multiparty governments does suspend their electoral decline. Accommodation to RRPs in parliament could also help the radical right parties to profit further from heavily campaigning on the immigration issue. Future research should therefore investigate if shifts to harsher government policy do pay off. Second, even though we have focused on radical right parties and their effect on immigration policies in this article, the strategy of position shifting should apply more generally. It would therefore be desirable to investigate whether other challenger parties that can pressure establishment governments on specific salient issues, such as green parties, have similar immediate influence on coalition governments.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.5 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank Cornelius Erfort, Leonie Fuchs, Violeta Haas, Christina Hecht and Clara Heinrich for excellent research assistance. We also thank Albert Falcó-Gimeno, Michael Laver and Lukas Stoetzer for valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Replication material for the main analyses is available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SW0WEG.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fabio Ellger

Fabio Ellger is a postdoctoral researcher in the Transformations of Democracy Unit at the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. His research centres on challenges to established democracies, with a focus on polarisation and representation. He serves as corresponding author. [[email protected]]

Heike Klüver

Heike Klüver is professor of comparative political behaviour at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her most recent book Coalition agreements as control devices: Coalition governance in Western and Eastern Europe (2023) has appeared in Oxford University Press. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Note that we utilize the term ‘clarity of responsibility’ to describe the period of confidential negotiations during which policy changes cannot be traced back to individual parties by the public. This conceptualization is different from Powell and Whitten (Citation1993) who coined the term to describe institutional party system features that hinder clear attribution of responsibility.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik (2016a). ‘Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts – How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:2, 417–36.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik (2016b). ‘Political and Institutional Determinants of Immigration Policies’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42:13, 2087–110.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Werner Krause (2020). ‘The Causal Effect of Radical Right Success on Mainstream Parties’ Policy Positions: A Regression Discontinuity Approach’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 829–47.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Matthias Orlowski (2016). ‘Moderate as Necessary: The Role of Electoral Competitiveness and Party Size in Explaining Parties’ Policy Shifts’, Journal of Politics, 78:3, 868–81.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow (2004). ‘Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or to past Election Results?’, British Journal of Political Science, 34:4, 589–610.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow (2006). ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976-1998’, American Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 513–29.

- Andersson, Staffan, Torbjorn Bergman, and Svante Ersson (2014). The European Representative Democracy Data Archive, Release 3. Main Sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

- Bernhardt, Dan, John Duggan, and Francesco Squintani (2009). ‘The Case for Responsible Parties’, American Political Science Review, 103:4, 570–87.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Markus Wagner (2019). ‘Do Voters Polarize When Radical Parties Enter Parliament?’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:4, 888–904.

- Browne, Eric C., and Mark N. Franklin (1973). ‘Aspects of Coalition Payoffs in European Parliamentary Democracies’, American Political Science Review, 67:2, 453–69.

- Browne, Eric C., and John P. Frendreis (1980). ‘Allocating Coalition Payoffs by Conventional Norm: An Assessment of the Evidence from Cabinet Coalition Situations’, American Journal of Political Science, 24:4, 753.

- Brug, Wouter van der, and Joost Van Spanje (2009). ‘Immigration, Europe and the ‘New’ Cultural Dimension’, European Journal of Political Research, 48:3, 309–34.

- Budge, Ian (1987). ‘The Internal Analysis of Election Programmes’, in David Robertson, Derek Hearl, and Ian Budge (eds.), Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-War Election Programmes in 19 Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 15–38.

- Budge, Ian (1994). ‘A New Spatial Theory of Party Competition: Uncertainty, Ideology and Policy Equilibria Viewed Comparatively and Temporally’, British Journal of Political Science, 24:4, 443–67.

- Budge, Ian, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (2001). Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments, 1945–98. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bustikova, Lenka (2014). ‘Revenge of the Radical Right’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:12, 1738–65.

- Converse, Philip E. (1964). ‘The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics’, in David E. Apter (ed.) Ideology and Its Discontents. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Cox, Gary W., and Mathew D. McCubbins (1986). ‘Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game’, Journal of Politics, 48:2, 370–89.

- Dancygier, Rafaela M. (2010). Immigration and Conflict in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DEMIG (2018). DEMIG POLICY, Version 1.3, Online Edition. www.migrationdeterminants. eu.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Sara Hobolt (2020). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Döring, Holger, and Philip Manow (2018). Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Modern Democracies. Version Stable 2018.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Eder, Nikolaus, Marcelo Jenny, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2017). ‘Manifesto Functions: How Party Candidates View and Use Their Party’s Central Policy Document’, Electoral Studies, 45, 75–87.

- Enelow, James M., and Melvin J. Hinich (1984). The Spatial Theory of Voting: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, Catherine De Vries, Marco Steenbergen, and Erica Edwards (2011). ‘Mean Voter Representation and Partisan Constituency Representation: Do Parties Respond to the Mean Voter Position or to Their Supporters?’, Party Politics, 17:3, 275–301.

- Folke, Olle (2014). ‘Shades of Brown and Green: Party Effects in Proportional Election Systems’, Journal of the European Economic Association, 12:5, 1361–95.

- Gamson, William A. (1961). ‘A Theory of Coalition Formation’, American Sociological Review, 26:3, 373.

- Grofman, Bernard (1982). ‘A Dynamic Model of Protocoalition Formation in Ideological N-Space’, Behavioral Science, 27:1, 77–90.

- Han, Kyung Joon (2015). ‘The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties on the Positions of Mainstream Parties regarding Multiculturalism’, West European Politics, 38:3, 557–76.

- Hobolt, Sara, and James Tilley (2016). ‘Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis’, West European Politics, 39:5, 971–91.

- Howard, Marc Morje (2010). ‘The Impact of the Far Right on Citizenship Policy in Europe: Explaining Continuity and Change’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36:5, 735–51.

- Hudson, Darren, Lee-Hong Seah, Diane Hite, and Tim Haab (2004). ‘Telephone Presurveys, Self-Selection, and Non-Response Bias to Mail and Internet Surveys in Economic Research’, Applied Economics Letters, 11:4, 237–40.

- Kim, Heemin, and Richard C. Fording (1998). ‘Voter Ideology in Western Democracies, 1946-1989’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:1, 73–97.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Anthony J. McGann (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Hanna Bäck (2019). ‘Coalition Agreements, Issue Attention, and Cabinet Governance’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:13–14, 1995–2031.

- Klüver, Heike, Hanna Bäck, and Svenja Krauss (2023). Coalition Agreements as Control Devices: Coalition Governance in Western and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2016). ‘Who Responds? Voters, Parties and Issue Attention’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:3, 633–54.

- Krause, Werner, and Miku Matsunaga (2023). ‘Does Right-Wing Violence Affect Public Support for Radical Right Parties? Evidence from Germany’, Comparative Political Studies, 56:14, 2269–305.

- Krauss, Svenja (2018). ‘Stability through Control? The Influence of Coalition Agreements on the Stability of Coalition Cabinets’, West European Politics, 41:6, 1282–304.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2006). ‘Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared’, European Journal of Political Research, 45:6, 921–56.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera (1979). ‘Effective Number of Parties a Measure with Application to West Europe’, Comparative Political Studies, 12:1, 3–27.

- Laver, Michael (1998). ‘Models of Government Formation’, Annual Review of Political Science, 1:1, 1–25.

- Lowe, Will, Kenneth Benoit, Slava Mikhaylov, and Michael Laver (2011). ‘Scaling Policy Preferences from Coded Political Texts’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36:1, 123–55.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2014). ‘Parties and Policymaking in Multiparty Governments: The Legislative Median, Ministerial Autonomy, and the Coalition Compromise’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 979–96.

- McGann, Anthony J., and Herbert Kitschelt (2005). ‘The Radical Right in the Alps: Evolution of Support for the Swiss SVP and Austrian FPÖ’, Party Politics, 11:2, 147–71.

- Meguid, Bonnie (2005). ‘Competition between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success’, American Political Science Review, 99:3, 347–59.

- Meyer, Thomas M. (2013). Constraints on Party Politics. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Moury, Catherine (2011). ‘Coalition Agreement and Party Mandate: How Coalition Agreements Constrain the Ministers’, Party Politics, 17:3, 385–404.

- Moury, Catherine, and Arco Timmermans (2013). ‘Inter-Party Conflict Management in Coalition Governments: Analyzing the Role of Coalition Agreements in Belgium, Germany, Italy and The Netherlands’, Politics and Governance, 1:2, 117–31.

- Mudde, Cas (1999). ‘The Single-Issue Party Thesis: Extreme Right Parties and the Immigration Issue’, West European Politics, 22:3, 182–97.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strom (2003). Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pedersen, Mogens N. (1979). ‘The Dynamics of European Party Systems: Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility’, European Journal of Political Research, 7:1, 1–26.

- Pickup, Mark, and Sara B. Hobolt (2015). ‘The Conditionality of the Trade-off between Government Responsiveness and Effectiveness: The Impact of Minority Status and Polls in the Canadian House of Commons’, Electoral Studies, 40, 517–30.

- Powell, G. Bingham (2000). Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Powell, G. Bingham, and Guy D. Whitten (1993). ‘A Cross-National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking account of the Political Context’, American Journal of Political Science, 37:2, 391.

- Prosser, Christopher, and Jonathan Mellon (2018). ‘The Twilight of the Polls? A Review of Trends in Polling Accuracy and the Causes of Polling Misses’, Government and Opposition, 53:4, 757–90.

- Roodujin, Matthijs, Stijn van Kessel, Caterina Froio, Andrea Pirro, Sarah de Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2019). ‘The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe.’ http://www.popu-list.org.

- Rydgren, Jens (2008). ‘Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in Six West European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 47:6, 737–65.