Abstract

The parliamentary oversight of the European Central Bank (ECB) is frequently criticised for its lack of focus in both monetary policy and banking supervision. While Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) can publicly question ECB decisions in these fields, they often use committee hearings for other purposes, such as expressing political positions on issues that may or may not be related to ECB activities. This article aims to conceptualise such variation by expanding the seminal distinction between ‘police patrols’ and ‘fire alarms’ to include two novel categories – ‘planning bureaus’ and ‘ambulance chasers’. To illustrate the applicability of our typology, the article provides the first systematic comparison of the Monetary and the Banking Dialogues (2014–2021), combining a qualitative content analysis of 1,504 parliamentary questions with insights from interviews with MEPs. The findings highlight the pervasiveness of fire alarms and ambulance chasing in the parliamentary practice of overseeing the ECB.

I would have expected a lot of questions on our monetary policy, on the level of inflation, on what inflation will be in two years’ time, on whether our projections are right or wrong, and on whether we are right or wrong to have the present level of interest rates, taking into account other decisions taken elsewhere in the world. However, I see that you have such a confidence in my institution that these are not a problem or an issue at all! I have also had a lot of questions on issues for which we are not responsible. (Trichet Citation2011)

Towards the end of his term as President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Jean-Claude Trichet shared his candid views about the content and quality of the Monetary Dialogues with the European Parliament (EP). From Trichet’s perspective, it was surprising that Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) had rarely challenged ECB decisions during his tenure, despite the opportunity to raise any sort of parliamentary question in the quarterly meetings between the two institutions. Trichet’s view resonates with many ECB scholars and practitioners: in fact, both the Monetary Dialogues and the hearings in banking supervision (henceforth the ‘Banking Dialogues’) have been strongly criticised over the years for their lack of focus on the mandate or performance of the ECB in either policy field (Amtenbrink and van Duin Citation2009; Claeys and Domínguez-Jiménez Citation2020; Lastra Citation2020; Maricut-Akbik Citation2020; Wyplosz et al. Citation2006). Moreover, the (ir-)relevance of parliamentary questions has been linked to the quality of democratic checks and balances in the European Union (EU) more broadly, as EP oversight is the main instrument to ensure the political accountability of the independent ECB (Braun Citation2017; Dawson et al. Citation2019; Diessner Citation2022; Elgie Citation1998).

In this article, we aim to understand the variation in the parliamentary practice of overseeing the ECB. While the EP has several mechanisms to monitor and investigate ECB activities (cf. Akbik Citation2022a), the central instrument remains the right to ask questions in specialised committee hearings, organised separately for monetary policy and banking supervision. How do MEPs use parliamentary questions to oversee the ECB in practice? Our contribution is twofold. Theoretically, we expand the seminal distinction between ‘police patrols’ and ‘fire alarms’ developed by McCubbins and Schwartz (Citation1984) to describe oversight behaviour in the US Congress. We argue that the distinction is relevant for our purposes but cannot fully capture oversight dynamics in the EP, where members raise parliamentary questions for a variety of reasons unrelated to the scrutiny of the executive – a trend which has also been observed in national parliaments (Martin Citation2011; Wiberg and Koura Citation1994). Borrowing from the literature on the function of parliaments, we argue that MEPs seek to fulfil ‘expressive’ functions as much as ‘control’ functions (Bagehot Citation1873; von Beyme Citation2000: 4) in their oversight of the ECB. In particular, we put forward the novel notions of ‘planning bureaus’ and ‘ambulance chasers’ to capture political positioning by MEPs on issues unrelated to the ECB’s performance in a given policy area.

Empirically, we provide the first systematic comparison of questions raised in the Monetary and Banking Dialogues, which so far have been analysed in isolation from each other – in line with the separation principle between monetary policy and banking supervision within the ECB (Amtenbrink and Markakis Citation2019; Diessner Citation2022; Ferrara et al. Citation2022; Maricut-Akbik Citation2020; Zeitlin and Bastos Citation2020). To this end, we conduct a qualitative content analysis of all (1,504) parliamentary questions raised during the Monetary and Banking Dialogues between 2014 and 2021, which we combine with primary data from 12 in-depth interviews with MEPs and staff members about their perceptions of oversight in both dialogues. Our findings reveal the prevalence of fire-alarm questions in the Banking Dialogues and of ambulance-chasing questions in the Monetary Dialogues, a result which we attribute to the resource intensity of preparing parliamentary questions and to the ambiguity of legislative goals in monetary policy compared to banking supervision.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. First, we offer a brief review of the literature on parliamentary oversight of the ECB, focussing on studies of the Monetary and Banking Dialogues (second section). We then develop our theoretical framework, introducing an extended typology of oversight logics that we subsequently apply to the EP and the ECB (third section). After discussing our research design and data (fourth section), we conduct an analysis of the Monetary and Banking Dialogues that uncovers the types of questions raised in the two fora as well as MEPs’ perceptions of the purpose of the dialogues (fifth section). The final section draws conclusions from the two cases and discusses the implications of our findings.

Parliamentary oversight of the ECB: from monetary policy to banking supervision

The European Parliament oversees the ECB in two separate capacities: first, as the central bank responsible for monetary policy in the euro area, and second, as the chief banking supervisor for countries participating in the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).Footnote1 The former is organised through the Monetary Dialogues, established in 1999 as the key platform for MEPs to engage directly with the ECB President, who appears four times a year before the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) (Eijffinger and Mujagic Citation2004). In banking supervision, the ECB’s Chair of the Supervisory Board participates in ordinary and ad hoc hearings in the ECON Committee three times a year (Art 20, SSM Regulation) since 2014, when the SSM came into being. This means that the oversight framework in banking supervision is newer and less studied than in monetary policy.

Critiques of the oversight of the ECB are as old as the Monetary Dialogues themselves (Berman and McNamara Citation1999; Buiter Citation1999; De Haan and Eijffinger Citation2000) and continue to be a staple in the literature on the ECB’s democratic accountability (Braun Citation2017; Chang and Hodson Citation2019; Dawson et al. Citation2019; Diessner Citation2022; Fraccaroli et al. Citation2020). Time and again, scholars have deplored the generic and superficial scope of the Monetary Dialogue, which has focussed – especially in the early years – on debating economic and financial policies rather than contesting ECB performance (Amtenbrink and van Duin Citation2009; Braun Citation2017; Gros Citation2004). Other studies have suggested that the ECB President mainly repeats to MEPs the information already conveyed through the Bank’s regular press conferences, which receive far more media attention than the Monetary Dialogues (Belke Citation2014; Claeys et al. Citation2014). The format of the Dialogues has also been criticised for preventing MEPs from asking follow-up questions and thus engaging in a genuine back-and-forth with the ECB President (Claeys and Domínguez-Jiménez Citation2020; Jourdan and Diessner Citation2019; Lastra Citation2020). Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that the hearings have improved over the years: MEPs ask questions that are both more frequent and more pertinent, while the ECB has become more responsive to their requests and the format of the hearings has been adapted several times to mitigate some of the aforementioned concerns (Collignon and Diessner Citation2016; Fraccaroli et al. Citation2018).

Moving to banking supervision, academic observers initially praised the SSM’s oversight framework as a marked improvement over similar arrangements in monetary policy (Braun Citation2017: 47; Fromage and Ibrido Citation2018: 306; ter Kuile et al. Citation2015: 155). However, a closer inspection of the content of parliamentary questions asked during the Banking Dialogues has revealed familiar problems. On the one hand, MEPs frequently pose questions about issues beyond the ECB’s competence in banking supervision, demonstrating either a lack of knowledge about the organisation of the SSM or a political interest in asking certain questions publicly, regardless of the correct addressee (Amtenbrink and Markakis Citation2019; Maricut-Akbik Citation2020). On the other hand, since MEPs are co-legislators in banking union law, they often use ECON hearings to solicit the ECB’s opinion on ongoing legislative proposals, which constitutes a form of ex-ante policy-making influence rather than ex-post oversight (Akbik Citation2022a, Citation2022b: ch. 4).

Over time, existing scholarship has attributed problems in the parliamentary oversight of the ECB to the format of the hearings, the limited powers conferred in the field by the EU Treaties, and the composition of the EP, which reflects diverse political and national interests (Claeys and Domínguez-Jiménez Citation2020; Dawson et al. Citation2019; Lastra Citation2020). Yet, despite these institutional constraints, MEPs still have ample opportunity – given the number of hearings per year – to pose pertinent questions to the ECB. While a number of recent analyses have shed light on the range of topics which MEPs emphasise in their questions (Akbik Citation2022b; Ferrara et al. Citation2022; Massoc Citation2022a), these accounts have stopped short of providing a theoretically-grounded understanding of the variation in parliamentary practices of oversight. We address this lacuna in the following section by developing a novel account of oversight dynamics, which we then apply to the EP and the ECB.

A typology of parliamentary oversight

At a basic level, parliamentary oversight aims to prevent abuses by executive actors, including but not limited to dishonesty, waste, arbitrariness, unresponsiveness, or deviation from legislative intent (MacMahon Citation1943: 162–3). Although definitions vary, the common understanding of the term implies an ex-post character (‘review after the fact’), focussing on ‘policies that are or have been in effect’ (Harris Citation1964: 9). Theoretically, the notion of oversight is anchored in studies on principal-agent relations in representative democracies and the question of how parliaments can control governments and the bureaucracy (Kiewiet and McCubbins Citation1991; Strøm Citation2000). In principal-agent terms, oversight is the counterpart to delegation, based on the premise that ‘A is obliged to act in some way on behalf of B’ and, in turn, that ‘B is empowered by some formal institutional or perhaps informal rules to sanction or reward A for her activities or performance in this capacity’ (Fearon Citation1999: 55).

A major distinction in the principal-agent literature is that between police-patrol and fire-alarm oversight (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984). As the label suggests, police patrols refer to the constant scrutiny of executive actors by parliaments in the attempt to detect violations and discourage divergence from legislative goals. According to McCubbins and Schwartz, this type of oversight is centralised, proactive, and direct: at their own initiative, members of Congress check the performance of a governmental agency by reading documents, requesting scientific studies, or conducting hearings (1984: 166). One important feature of police patrols is their general character, aiming to serve the public interest by evaluating, at random, a sample of executive activity. By contrast, fire alarms relate to the instruments available to those affected by executive decisions. In particular, fire alarms refer to the totality of procedures through which interested third parties (such as citizens, civil society organisations, or interest groups) can complain to the parliament about past or prospective decisions in policy areas mandated to the executive (Saalfeld Citation2000: 363). In this respect, fire alarms are indirect, reactive, and decentralised, offering members of parliament (MPs) the chance to act as intermediaries (or representatives) of aggrieved constituents.

Furthermore, McCubbins and Schwartz argue that fire alarms are more common and effective than police patrols for two reasons. First, MPs simply do not have the time or resources to conduct systematic oversight of all executive actors. Second, even if such an exercise became feasible owing to increased resources, legislative goals are often too vague to discern clear violations (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984: 172). By comparison, fire alarms allow affected parties to complain and seek remedy against governmental action in a more targeted way. From the perspective of MPs, fire alarms are more resource-efficient because the burden of gathering information typically falls on the complaining actor. Moreover, fire alarms acknowledge that MPs can change their preferences over time, in line with new political alignments and recent policy developments (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984: 171).

The distinction between police patrols and fire alarms has gained considerable traction in academic debates over the years. However, when it comes to the ubiquitous oversight practice of posing parliamentary questions, scholars routinely emphasise the disconnect between the subject of questions and the presumed goal to scrutinise the executive (Martin Citation2011; Wiberg and Koura Citation1994). Recent work in legislative studies, for example, has shown that MPs raise questions for a variety of reasons, including as a signal to their constituencies (Chiru Citation2018; Kellermann Citation2016), to gain strategic advantages within their own party or coalition (Höhmann and Sieberer Citation2020; Otjes and Louwerse Citation2018), or to maintain a media presence by inquiring about topics considered newsworthy (van Santen et al. Citation2015; Vliegenthart and Walgrave Citation2011). Put differently, it is a common practice across parliaments to use oversight instruments for reasons other than scrutinising the executive. If this is the case, however, it would seem necessary to update the distinction between police patrols and fire alarms to better understand the actual uses of parliamentary questions in practice. We develop such an updated typology below.

Types of questions in parliamentary oversight

Our typology starts from the premise that MPs do not necessarily use established oversight instruments for their originally intended purpose. To account for the wide range of questions found in the practice of parliamentary oversight, we propose to supplement the distinction between police patrols and fire alarms with insights from the literature on the functions of parliaments (Bagehot Citation1873; Norton Citation1993). Scholars in this tradition have identified a multitude of functions of parliaments, which can be grouped into four main categories: (i) legislative, (ii) elective, (iii) control, and (iv) expressive (von Beyme Citation2000; chapter 4). First, parliaments around the world have the task to draft, discuss, and adopt legislation, which is why they are also known as law-making bodies. Second, parliaments are responsible for the ex-ante selection of government office holders, especially in parliamentary regimes where they ‘elect’ the cabinet (Sieberer Citation2011). Third, parliaments exercise ex-post control over government officials, whom they can question and potentially remove from office, depending on the (constitutional) rules of a polity. Fourth, parliaments are expected to represent and articulate different societal interests; in this respect, they perform an expressive function on behalf of their constituents (von Beyme Citation2000: 73).

For the purpose of our typology, only some parliamentary functions are relevant for a discussion of oversight. With respect to the legislative function, previous research has established that parliamentary questions have a symbolic influence on legislation at best (Otjes and Louwerse Citation2018; Vliegenthart and Walgrave Citation2011). Similarly, when it comes to the elective function, oversight questions are formally separated from the ex-ante selection of office holders through appointment and confirmation hearings, for example (Sieberer Citation2011), which renders them beyond the scope of our typology. By contrast, control functions are directly related to the notion of parliamentary oversight, in line with the principle of checks and balances in a representative democracy: in essence, oversight is one of the key instruments through which legislatures exercise control over executive actors and contribute to democratic accountability (Strøm Citation2000). Finally, the expressive function of parliaments has an ambiguous relationship to oversight. In theory, MPs can articulate various societal interests in their oversight of the executive by asking probing questions on behalf of their constituents. At the same time, MPs may use parliamentary questions to position themselves on topical issues which are unrelated to the scrutiny of the executive, thus fulfilling a representative but not an oversight function.

Accordingly, we propose a typology of parliamentary questions organised around two dimensions: (1) the trigger of questions raised during parliamentary oversight, and (2) the function of questions in relation to the goals of elected representatives (see ). The first dimension (the trigger of questions) captures the original distinction between police patrols and fire alarms, namely, the proactive scrutiny of executive actors versus the event-driven reaction to developments brought to the attention of MPs by interested third parties (Balla and Deering Citation2013). Proactive questions reveal the willingness of MPs to inquire pre-emptively, at their own initiative, about the past or future activities of an actor under scrutiny. By contrast, reactive questions assume an external trigger: MPs raise questions in response to external complaints by stakeholders (the media, their constituents, other institutions).

Table 1. Types of questions in parliamentary oversight.

The second dimension (the function of questions) captures the potential reasons for which MPs might ask parliamentary questions in the first place. In particular, the intention behind raising a question in an oversight setting may either be (1) to control the executive (in line with the original logic of parliamentary oversight), or (2) to express or articulate societal interests (in line with MPs’ role as elected representatives). When focussed on control, parliamentary questions seek to throw ‘the light of publicity’ on executive actors, with MPs demanding ‘a full exposition and justification’ of decisions and ‘pressing for action’ to improve government conduct (Mill Citation1861). Control-oriented questions lie at the heart of parliamentary oversight, probing whether executive actors performed poorly or dishonestly, took arbitrary decisions, or deviated from legislative intent (MacMahon Citation1943: 162–3). By contrast, expressive questions are unrelated to the ex-post scrutiny of an executive actor. Their goal is to capture ‘the mind of the people’ by articulating what constituents want or find important (Bagehot Citation1873: 119) regardless of their connection to the addressee of the question. For MPs, expressive questions send a message to potential supporters that the interests of a constituency are represented, even if the query might not be relevant for executive scrutiny. While we acknowledge that control-oriented questions might in principle also be expressive, we separate the two for reasons of conceptual clarity. To put it simply, control-oriented questions are relevant for holding executive actors accountable in terms of their (core) tasks, whereas expressive questions are not.

Bringing the two dimensions together, we construct a 2 × 2 table that yields four different logics of questions in parliamentary oversight (). Following the original metaphor of McCubbins and Schwartz, we label questions related to the expressive function of parliaments as ‘planning bureaus’ (proactive) and ‘ambulance chasers’ (reactive) respectively. We briefly discuss the four logics in turn, with a focus on the two novel categories.

First, as regards the control function of parliamentary questions, police patrols are control-oriented in that they examine past and current activities of executive actors with the goal to proactively check compliance with legislative intent or to detect deviations such as waste or dishonesty. In the same vein, fire alarms are also about controlling the executive, but they are driven by external events or triggers, such as ongoing scandals or complaints that challenge the conduct or decisions of an actor.

Next, planning bureaus are proactive in that they allow MPs to pursue their political agendas related to the actor under scrutiny out of their own initiative. As their name suggests, planning bureaus are future-oriented and comprise envisaged changes to the policy decisions taken by the actor. They are expressive questions to the extent that they enable MPs to articulate political positions that they consider to be in the interests of their constituencies or in line with their party ideology, even if the topics covered are unrelated to the ex-post scrutiny of executive activities.

The fourth and final logic of parliamentary questions is ambulance chasing. The term originates in the legal profession, where ambulance chasers are personal injury lawyers who spend time at accident sites to advertise their services among potential victims (Reichstein Citation1965). In this context, the term is derogatory, denoting the search for financial gain from other people’s misfortunes. In scientific research, ambulance chasing is understood more broadly as a surge in the number of publications on a ‘hot topic’ whose novelty and added-value are yet to be confirmed (Backović Citation2016). We build on the second meaning and argue that ambulance chasing occurs in parliamentary oversight when MPs use institutionalised settings of scrutiny to bring up issues which are salient in the public sphere and easily lend themselves to political positioning – even if such topics are outside the scope of the activities conducted by their interlocutor. In this way, ambulance chasing is primarily expressive, allowing MPs to articulate interests as elected representatives and stay in the public spotlight, regardless of the relevance of their interventions for the logic of oversight. Similar to fire alarms, ambulance chasing is reactive, following up on reports from stakeholders such as negative media coverage, complaints by constituents, civil society groups, or other institutions. Unlike fire alarms, ambulance chasing does not seek to control the executive; for instance, MPs might be interested in taking a stance on an ongoing scandal, even if their interlocutor was not responsible for that scandal.

In line with McCubbins and Schwartz (Citation1984), we also formulate expectations about the relative frequency of different types of questions in the practice of oversight. First, we acknowledge that proactive questions are likely to be significantly more resource-intensive than reactive questions. For their part, police patrols require financial and human resources to be invested in monitoring executive actors, while planning bureaus assume up-to-date knowledge of future activities and planned decisions. By contrast, fire alarms and ambulance chasing are considerably less resource-intensive, as MPs merely follow up on items brought to their attention by external stakeholders, complaint bodies, or the media (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984). Ambulance chasing has the lowest resource threshold because the issues at stake do not even have to be directly related to the activities of the actor under scrutiny. In short, the more resources are required to scrutinise the activities of an executive actor, the more MPs can be expected to use reactive questions in the practice of parliamentary oversight.

Second, we build on McCubbins and Schwartz’s premise that legislative goals ‘are often stated in such a vague way that it is hard to decide whether any violation has occurred’ (1984: 172). In policy studies, vagueness (or ambiguity) is an in-built feature of the legislative process, considered ‘a prerequisite for getting new policies passed at the legitimation stage’ because it allows ‘diverse actors [to] interpret the same act in different ways’ (Matland Citation1995: 158). From a legal perspective, if a law is vague or ambiguous, the scope of its application becomes uncertain, including the likelihood of being held liable for breaking that law (Hadfield Citation1994). Transposed to public institutions and parliamentary oversight, we expect legislative ambiguity to make it harder for MPs to formulate control-oriented questions. While McCubbins and Schwartz see vagueness as a reason for the prevalence of fire alarms over police patrols, we expect this feature to fit best with the expressive function of elected representatives. Accordingly, the vaguer or more ambiguous the legislative goals in a policy area, the more MPs are going to make use of expressive questions in the practice of parliamentary oversight. This can be done either proactively (through planning bureaus) or reactively (through ambulance chasing). For their part, planning bureaus allow MPs to try to influence future policy agendas and potentially reduce existing ambiguity. By contrast, ambulance chasing assumes that MPs do not seek to overcome ambiguity and instead play along with it, using the toolkit of parliamentary oversight to take political positions on issues unrelated to the scrutiny of the executive. In the next section, we transpose our typology of parliamentary questions to the specific setting of ECB oversight.

The EP and the ECB

The scope for parliamentary oversight of the ECB is delineated by EU Treaty provisions on central bank independence as well as the EP’s rules of procedure for posing parliamentary questions (Braun Citation2017; Fromage and Ibrido Citation2018). Legally, the ECB’s mandate in monetary policy and banking supervision is relatively narrow, assigning primacy to price stability (as opposed to full employment, for example) and financial stability of the banking sector (as opposed to supervision of other types of financial entities) (Dawson et al. Citation2019). For our typology, these legal constraints help create the benchmarks against which we can classify individual questions, as explained below.

First, police patrols include parliamentary questions focussed on the routine activities of the ECB, where the goal is to check whether the central bank performs its functions as envisaged in the relevant legislation (EU Treaties, ECB Statutes, the SSM Regulation, Banking Union law). For monetary policy, this primarily means inquiring about price stability and the extent to which ECB policies and/or other developments affect the achievement of its inflation target (European Central Bank Citation2021).Footnote2 In banking supervision, police patrols refer to the ECB’s task to ensure ‘the stability of the financial system’ (SSM Regulation, Article 1) and to act as a ‘tough and fair’ supervisor in the SSM (Maricut-Akbik Citation2020). As an implementer of secondary law, the ECB is less independent in banking supervision than in monetary policy, where it has wider discretion to decide on the instruments necessary for achieving price stability (Akbik Citation2022b). Consequently, MEPs should be able to question the ECB more directly in matters of banking supervision, as this is where they can identify and challenge deviations from legislative intent.

Second, fire alarms are event-driven, meaning that MEPs ask questions about specific past policy decisions or actions brought to their attention. Typically, such events are reported in the news, are relevant to civil society or the research community, or are pushed by lobbyists and other stakeholders. For instance, the use of unconventional monetary policy instruments caught the attention of many MEPs, owing to strong criticism from national constitutional courts, governments, parts of the research community, and even former central bankers (Dawson et al. Citation2019; Fontan and Howarth Citation2021). In banking supervision, controversial decisions may stem from the preferential treatment of banks during stress tests or from the need to put an ailing bank into resolution. Moreover, MEPs can act on complaints from other EU bodies, such as the European Ombudsman or the European Court of Auditors. The key point is that fire-alarm questions are reactive, responding to concrete events, scandals, or external complaints about ECB actions.

Third, planning bureaus comprise expressive questions that anticipate or push for changes in the existing framework for monetary policy and banking supervision, either de iure or de facto. Despite the far-reaching independence of the ECB, MEPs frequently express their views about hypothetical central bank actions in established and novel policy areas. Planning-bureau questions have a clear ex-ante component, as they are invoked by MEPs who seek to shape the agenda of the ECB and draw attention to future-oriented topics. In monetary policy, planning bureaus revolve around issues that MEPs would like the ECB to consider more explicitly in its decision-making processes, such as inequality or, more recently, the fight against climate change (Ferrara et al. Citation2022; Massoc Citation2022a). In the area of banking supervision, planning bureaus may refer to ongoing negotiations over legislative proposals in the area of banking union law, for example, where the EP is a co-legislator (Akbik Citation2022b).

Finally, ambulance chasing is reactive and driven by whatever issues are considered salient by MEPs at a given moment in time, even if these are not directly related to the ECB mandate. Ambulance chasing allows MEPs to position themselves publicly on topical events and to draw the ECB into current debates, even if those are not strictly within the purview of the central bank. Examples include the debate about the reform of fiscal rules in European economic governance, the appropriate EU response to trade tensions with the United States under Donald Trump, or scandals related to money laundering and consumer protection in banking supervision (which are not an ECB competence).

To sum up, and considering our theoretical discussion above, we expect reactive questions (fire alarms and ambulance chasing) to outweigh proactive questions (police patrols and planning bureaus) in both monetary policy and banking supervision. However, in terms of legislative ambiguity, we consider monetary policy to have vaguer legislative goals than banking supervision owing to the operational independence and ample discretion of the ECB in this field, which allows it ‘to define and implement the monetary policy of the Union’ (Article 127(2) TFEU). Apart from the 2% inflation target over the medium term (European Central Bank Citation2021) and the prohibition of monetary financing (Art 123 TFEU), MEPs have few clear goals against which to assess the performance of the ECB in monetary policy. By contrast, the ECB was conferred specific tasks relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions, which are narrowly defined in EU secondary legislation (Art 4, SSM Regulation). Consequently, there is greater scope for checking deviation from legislative intent in banking supervision than in monetary policy, which is why we expect more fire-alarm questions in this field. Lastly, compared to banking supervision, monetary policy tends to get intertwined with broader and more salient economic governance issues – often in connection with the sustainability of the Eurozone as a whole – which is expected to invite more ambulance-chasing questions. Having outlined our main expectations, we now turn to the research design and data used for the empirical analysis.

Research design and data

Our analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we apply our extended typology to two datasets of parliamentary questions in the area of monetary policy (Fraccaroli et al. Citation2022; Massoc Citation2022b) and banking supervision (Akbik Citation2022b; Maricut-Akbik Citation2020), the latter of which we expand to 2021.Footnote3 The goal is to categorise questions as police patrols, fire alarms, planning bureaus, or ambulance chasers, in line with the preceding conceptualisation. The codebook for our qualitative content analysis is available in the Online Appendix, including a discussion of inter-coder reliability. The resulting classification allows us to examine our central theoretical expectations, namely: (1) whether reactive questions feature more prominently than proactive questions in both monetary policy and banking supervision; (2) whether ambulance chasing is more prominent in monetary policy; and (3) whether fire-alarm questions are most common in banking supervision.

To analyse comparable data, we only include Monetary Dialogues which took place since the establishment of the SSM in 2014, thus ensuring that the ECON Committee had the same membership in both fora. Accordingly, the period under investigation is 2014–2021, covering the eighth and ninth parliamentary terms. The data include a total of 976 individual questions for the Monetary Dialogue, retrieved from a dataset compiled by Massoc (Citation2022b),Footnote4 and 528 individual questions for the Banking Dialogue, retrieved from Akbik (Citation2022a) and Maricut-Akbik (Citation2020). Each question has been hand-coded by the authors in line with the codebook. The Online Appendix reports basic descriptive statistics and provides figures which illustrate the distribution of the data across time, hearing types, parliamentary groups, and the nationality of MEPs. We also provide examples for each type of question raised in both dialogues.

Next, we conduct a plausibility probe of the applicability of our typology to parliamentary oversight of the ECB (Levy Citation2008: 6) with the help of primary data on the perceptions of MEPs about their oversight activities. Since we are interested in MEPs’ reasoning behind asking parliamentary questions, we seek to understand their views and beliefs about the purpose of parliamentary oversight. To this end, we use interview data collected from the ECON Committee at different points in time. In the first round (2018), we conducted five interviews with two MEPs, two parliamentary assistants, and a staff member of the ECON Secretariat about their perceptions of the Monetary Dialogue. In the second round (2022), we conducted five interviews and received two completed interview questionnaires from MEPs about their perceptions of the Banking Dialogue in comparison with the Monetary Dialogue. The interviewed MEPs represent diverse political groups in the two parliamentary terms (for an overview, see the Online Appendix).

What the data show: types of questions in the parliamentary oversight of the ECB

Monetary Dialogues

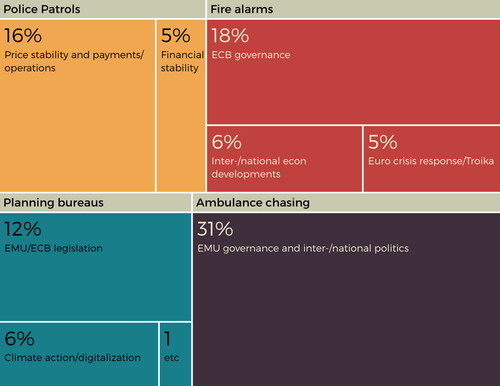

We start with an overview of parliamentary questions identified in the Monetary Dialogues during the period 2014–2021, which included 21 hearings from the eighth parliamentary term (2014–2019) and 10 hearings from the ninth parliamentary term (2019–2021). provides a breakdown of questions by topic and their categorisation as police patrols, fire alarms, planning bureaus, or ambulance chasers (for an overview of types of questions per year, see Figure A2 in the Online Appendix). First, police-patrol questions are proactive and oriented towards the ECB’s primary mandate. In this category, most questions refer to (a) the appropriate monetary policy stance to achieve price stability (both from above and from below) and (b) the general economic outlook for the euro area in terms of its implications for price and financial stability. The aim of police-patrol questions is proactive oversight, requiring MEPs to inform themselves about the state of the macroeconomy in order to assess the performance of the ECB’s monetary policy-making. In this category, a typical question from a more progressive/left-leaning MEP would ask what the ECB could do to reach its inflation target, while a more conservative/right-leaning MEP would usually inquire whether the ECB should end its unconventional policies considering prospective financial stability risks.

Second, fire-alarm questions illustrate how MEPs follow up on ECB response to crises or other challenges facing the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), as signalled by other stakeholders. Often, such questions refer to media reports, recent studies, or reports by civil society actors that describe problems in the field. Substantively, most questions relay concerns about the ECB’s governance of the Eurozone (such as the lack of risk-sharing, the threat of moral hazard, or the ECB’s participation in the Troika to oversee financial assistance programs). By default, fire-alarm questions are reactive, focussed on how the ECB has handled or positioned itself on concrete events.

Third, planning bureau questions include topics through which MEPs seek to expand or influence future ECB agendas in line with their preferences. Many of these questions refer to (a) MEPs’ own legislative files or activities as rapporteurs, (b) challenges related to climate change and the green transition (including questions on green bond purchases, the Paris agreement, and sustainable finance more generally), and (c) the digital transition (including proposals for the regulation of crypto assets or the growing role of big tech and fintech firms). Such questions are often prefaced with an explanation for the need to change course in line with the concerns of particular groups of constituents, such as workers, the self-employed, families, poorer households, or the younger generations.

Lastly, ambulance-chasing questions cover a bewildering array of queries raised by MEPs, many of which are related to national and international political developments that defy straightforward subcategorization. Examples include requests for the ECB’s views on national election results, its assessment of the future value of the Chinese currency, or how the bank sees the latest decisions by the UK government in the Brexit negotiations. At times, the ECB President responds to queries of this kind with formulations like ‘I frankly do not know’. It should be noted, however, that the designation ‘ambulance chasing’ does not imply that MEPs are necessarily the ones initiating such questions. In fact, the proverbial ambulance can be ‘dispatched’ by the ECB itself, given that the central bank has had the tendency to weigh in on topics beyond its purview in the past. Examples include the ECB advocating for national structural reforms or stressing the need for a Capital Markets Union in the EU, which are then picked up by MEPs in their parliamentary questions.

Overall, the highest proportion of questions in the Monetary Dialogues between 2014 and 2021 are ambulance chasers (31%), in line with our theoretical expectation, followed by fire alarms (29%), police patrols (21%), and planning bureaus (19%). We also find empirical support for the expectation that reactive questions (fire alarms and ambulance chasers) outweigh proactive questions (police patrols and planning bureaus) in the parliamentary oversight of monetary policy. At the same time, the proportion of expressive questions (planning bureaus and ambulance chasers) is equal to that of control questions (police patrols and fire alarms). This suggests that the Monetary Dialogues are simultaneously a setting for the parliamentary scrutiny of the ECB and a prominent platform for political position-taking. The same cannot be said of banking supervision, as shown below.

Banking Dialogues

For banking supervision, the data include parliamentary questions asked in the ECON Committee during 14 hearings from the eighth parliamentary term (2014–19) and seven hearings from the ninth parliamentary term (2019–21). provides a breakdown of questions organised by topic and their classification according to our typology (for an overview of the type of questions asked every year, see Figure A3 in the Online Appendix).

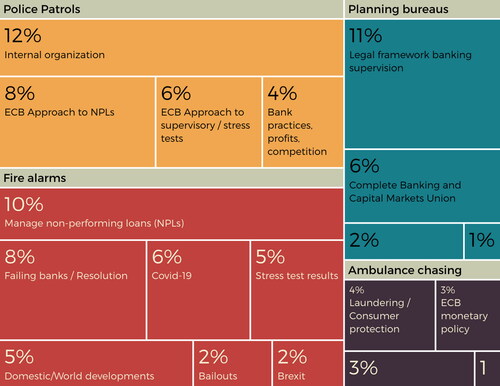

First, police patrols revolve around routine practices of ensuring the correct and consistent application of the SSM legal framework. In this category, most questions refer to (a) the internal organisation of the SSM (which was especially relevant in 2014–2015, when the ECB took over banking supervision in the euro area); (b) the general ECB approach to non-performing loans (NPLs), developed through so-called ‘guidance’ documents; (c) the practice of stress tests and the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, as well as (d) broad questions about banks’ profits and market competition. The point of police-patrol questions is proactive oversight, focussed on understanding and assessing the performance of the ECB in banking supervision.

Next, fire alarms capture how MEPs reacted to banking crises or concrete problems arising in the member states. Often, such questions directly cite media articles, complaints by stakeholders, auditors, or other legal reports. One prominent example comes from 2017, when MEPs ‘rang the alarm’ in response to a report by the parliament’s legal service which flagged the ECB’s new supervisory expectations on NPLs as ultra vires because they introduced additional obligations for banks beyond the current regulatory framework (Maricut-Akbik Citation2020: 208). Otherwise, most fire-alarm questions concern (a) specific banks that faced capital shortfalls owing to a high level of NPLs, (b) banks that were put into resolution after being declared failing-or-likely-to-fail, or (c) banks that performed poorly in stress tests.

Third, planning bureaus comprise items through which MEPs seek to expand or influence future ECB agendas. Most of these questions refer to (a) ongoing legislative proposals in the EU Banking Union as well as (b) related files on the adoption of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) and the completion of the Capital Markets Union. To a lesser extent, planning bureaus include queries about (c) the necessity to incorporate climate and digitalisation considerations in the ECB’s supervisory approach. Such questions were proactive, allowing MEPs to present and gather support for their own political positions in legislative files or to promote the agendas of their political groups and constituencies (for example, on climate change).

Finally, ambulance chasers include questions that are both reacting to external events and unrelated to ECB decisions in banking supervision. Such questions typically refer to issues falling under the competence of national supervisors, such as money laundering, consumer protection, granting state aid to banks or approving their recapitalisation (which is managed by the European Commission). Typically, MEPs would pick up on a current scandal unfolding at a bank in their member state and ask the ECB about it, even if the ECB did not have responsibilities to act on the matter. Lastly, there are questions on the ECB’s recent monetary policy decisions, which also fall outside the purview of the Supervisory Board, in line with the separation principle between banking supervision and monetary policy. In a handful of instances, it was unclear whether MEPs understood the different tasks of the ECB in monetary policy and banking supervision. Yet, compared to the Monetary Dialogues, there are notably fewer ambulance-chasing questions in the Banking Dialogues (only 10% overall).

In sum, and in contrast to the Monetary Dialogues, more than two thirds of the questions in banking supervision are connected to controlling the ECB’s conduct against its mandate, categorised as fire alarms (39%) and police patrols (30%) respectively. Expressive questions are fewer, but still considerable, including planning bureaus (21%) and ambulance chasing (10%). In line with our theoretical expectations, MEPs ask more fire-alarm questions in the Banking Dialogues owing to the greater possibility to identify concrete scandals or specific complaints by third parties. Contrary to our expectations, however, reactive questions (fire alarms and ambulance chasers) do not outnumber proactive questions (police patrols and planning bureaus), which are almost equal in number. One potential explanation for this finding is the ongoing legislative work done by MEPs in the ECON Committee, who are involved in all proposals in Banking Union law. According to previous research, questions on legislative proposals are typically asked by MEPs who are rapporteurs on those files (Maricut-Akbik Citation2020: 1207) and have an interest in shaping the fields’ policy agenda, which would translate into planning bureaus. In other words, MEPs can apply the know-how accumulated during the legislative process to the practice of parliamentary oversight, thus reducing the number of resources required for planning bureaus. In the next section, we explore these observations further by delving into MEPs’ own views concerning the goals of parliamentary oversight.

What MEPs think: perceptions of parliamentary oversight of the ECB

Our interview data reveal a wide range of views among MEPs concerning the purpose of the Monetary and Banking Dialogues. On average, MEPs emphasise elements of fire alarms and planning bureaus more frequently than police patrols. While ambulance chasing is not acknowledged openly due to its negative connotations, MEPs do stress the importance of media salience and political positioning for the practice of parliamentary oversight.

Given our expectation about the preponderance of reactive as opposed to proactive oversight of the ECB, we start by looking at the trigger of parliamentary questions. Several interviewees suggest that since MEPs must prioritise how they spend their time, they are often driven by media attention and public pressure on a given topic. In their words:

Only if there’s a scandal—concrete cases—then you can have a look and squeeze the ECB for answers. When things go fine, people don’t care. (Interview 11)

A politician always follows where public attention is. [This] is normal. So if there’s a big scandal with a bank that all the newspapers are talking about, then members immediately jump in. This is our job as well. (Interview 12)

Interestingly, in banking supervision, MEPs view the objective of hearings as linked to ‘pressing ongoing issues’ (fire alarms), such as the effect of the war in Ukraine on EU financial stability, but also in connection with ‘ongoing legislative procedures’ (planning bureaus) (Questionnaire 7). This last point is surprising because planning bureaus are part of proactive oversight and hence expected to be resource-intensive; however, in the context of the EP’s current legislative agenda in Banking Union law, it makes sense for MEPs to apply some of the resources invested in the legislative process to the parliamentary oversight of the ECB. Although the interest in influencing the ECB’s agenda – a key characteristic of planning bureaus – is mentioned several times, MEPs acknowledge that such efforts can only be indirect due to the ECB’s independence:

I think that what we look for—if I take my perspective as an MEP—are public commitments because those are public sessions. […] Then you know that the likelihood that this is going to happen is bigger. (Interview 12)

The observation leads us to the second dimension of our typology, namely the purpose of questions in relation to the goals of elected representatives. In fact, it seems that MEPs take for granted the use of the Monetary and Banking Dialogues as a platform for political positioning. For instance, several MEPs suggest that the Monetary Dialogue allows them to articulate important policy differences, depending on their political groups:

I have a very particular view regarding the ECB’s monetary role. I believe monetary policy should be subject to democratic control, meaning monetary decisions should be taken by elected governments. (Questionnaire 8)

I personally am very critical of quantitative easing, and the interest rates in recent years, and I ventilate my opinion in every interview, but there’s no hair on my head thinking that we should change the Treaties so that politicians can interfere in monetary policy. (Interview 6)

Monetary policy has expanded massively in the last years. Massively. Now it impacts on normal policies. […] If the ECB is taking a decision which is affecting our fight against climate change, like buying massively carbon assets, it means that it needs to respond on why they’re doing that. I think that the need for democratic accountability is today bigger than ten years ago because of that reason. (Interview 12)

Conclusion

This article expanded the classic typology of police-patrol and fire-alarm oversight with two new categories: planning bureaus and ambulance chasers. Focussing on the practice of parliamentary questions, we have shown that MPs have a marked tendency to try and shape future policy agendas or ‘play to the gallery’ on issues popular with their constituencies, regardless of the relevance of their interventions for oversight purposes. As such, parliamentary questions often go beyond ‘patrolling’ executive actions or ‘ringing the alarm’ in the event of a scandal or crisis. Instead, as political actors, MPs seek to influence policy decisions (planning bureaus) or position themselves on current events (ambulance chasing) through expressive questions.

Empirically, we provided the first systematic comparison of EP oversight in the Monetary and Banking Dialogues during the period 2014–2021. Our findings showed that MEPs are at least as likely to focus on reactive oversight as on proactive oversight in both dialogues, although the proportion of questions scrutinising potential ECB misconduct is higher in banking supervision than in monetary policy (69% versus 50% of all questions). Conversely, ambulance chasing is less common in the Banking Dialogues compared to the Monetary Dialogues (10% versus 31%), a finding which we attribute to the higher legislative ambiguity that characterises EU monetary policy-making. Indeed, MEPs have few benchmarks against which to assess the performance of the ECB in this field, especially when it comes to the unconventional monetary policies which have become ubiquitous since the 2007–08 global financial crisis. As a result, MEPs often link monetary policy to broader political debates, such as the pursuit of fiscal consolidation in the euro area or various proposals for completing the EMU. Since these issues have commanded public attention over the last decade, MEPs frequently ask about them in parliamentary questions, even if technically they fall outside the ECB’s remit. By contrast, banking supervision has clearer legislative goals – created by the legal framework of the Banking Union – which can be used to assess the performance of the ECB.

Future research may build on our analysis and dig deeper into the underlying causes of variation in the parliamentary oversight of the ECB over time, including the composition of the ECON Committee in terms of party affiliations and nationality of MEPs (as detailed in the Online Appendix). For instance, the proportion of ambulance-chasing questions raised during the Monetary Dialogues appears to have declined somewhat over the years, while the proportion of police patrol questions has been on the rise, if only modestly (see Figure A2 in the Online Appendix). Follow-up research could draw on data from the entire 9th parliamentary term to assess whether this trend has been sustained or not.

Finally, from a normative perspective, our analysis speaks to McCubbins and Schwartz’s contention that fire alarms, while less comprehensive than police patrols, are useful accountability instruments because they still fall under the control function of parliamentary scrutiny. However, our findings also suggest that many parliamentary questions deviate from the traditional function of controlling the executive and should instead be classified as fulfilling a parliament’s expressive function. For those concerned about the accountability of the ECB, the high frequency of expressive questions in the Monetary and Banking Dialogues is worrisome because it signals a certain degree of ‘forum drift’ away from the task of overseeing executive actors (Schillemans and Busuioc Citation2015). The silver lining of our analysis lies in the higher proportion of control questions identified during the Banking Dialogues, which suggests that a similar outcome could also be achieved in the Monetary Dialogues as well – if only the EP had more concrete benchmarks against which to assess the performance of monetary policy. A potential, albeit contentious, implication is that if MEPs were to become co-legislators in the monetary union – thereby approximating the role of principals over the ECB – the quality of parliamentary oversight will increase as well. Ultimately, however, our analysis revealed that a substantial subset of parliamentary questions is geared towards achieving an expressive function even in the more focussed Banking Dialogues. We therefore expect ambulance chasers and planning bureaus to remain pervasive features of parliamentary practice for the foreseeable future.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.6 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper to the participants of a workshop organized at the University of Florida in February 2023, the attendees of the EU Governance Seminar at Leiden University in March 2023, as well as for feedback received during panel discussions at the 2023 conference of the European Union Studies Association (EUSA). We are also thankful to the European Parliament’s Economic Governance Support Unit and Positive Money Europe for facilitating data collection while the authors prepared an in-depth analysis (Akbik Citation2022a) and a policy report (Jourdan and Diessner Citation2019) on the topic (for an overview and discussion of the data, see the Online Appendix).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Mendeley Data repository, doi: 10.17632/6kr8vmsbrc.1.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adina Akbik

Adina Akbik is Senior Assistant Professor of European Politics at Leiden University. Her research focuses on political accountability in the Economic and Monetary Union, the enforcement powers of EU agencies, and the role of cultural stereotypes in EU governance. Her work has been published by Cambridge University Press (2022), Comparative Political Studies and the Journal of European Public Policy, among others [[email protected]]

Sebastian Diessner

Sebastian Diessner is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University. His research focuses on the politics of economic policy, monetary and financial governance, and the interplay between technological and institutional change. His recent work has appeared in Perspectives on Politics, Review of International Political Economy and Politics & Society, among others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 As of January 2023, the SSM includes all 20 euro-area countries plus Bulgaria.

2 For a discussion of how the ECB might itself be seen as a ‘policeman and judge’, see Howarth (Citation2004).

3 The datasets are either publicly available or accessible upon request from the quoted authors.

4 Unlike Massoc (Citation2022b), we code individual questions by MEPs rather than full interventions, as MEPs can ask different questions at a time.

References

- Akbik, Adina (2022a). The European Parliament as an Accountability Forum: Overseeing the Economic and Monetary Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Akbik, Adina (2022b). ‘SSM Accountability: Lessons Learned for the Monetary Dialogues’, European Parliament Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV), available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2022/699545/IPOL_IDA(2022)699545_EN.pdf (accessed 25 July 2022).

- Amtenbrink, Fabian, and Kees van Duin (2009). ‘The European Central Bank before the European Parliament: Theory and Practice after Ten Years of Monetary Dialogue’, European Law Review, 34:4, 561–83.

- Amtenbrink, Fabian, and Menelaos Markakis (2019). ‘Towards a Meaningful Prudential Supervision Dialogue in the Euro Area? A Study of the Interaction between the European Parliament and the European Central Bank in the Single Supervisory Mechanism’, European Law Review, 44:1, 3–23.

- Backović, Mihailo (2016). ‘A Theory of Ambulance Chasing’, available at http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.01204 (accessed 5 December 2022).

- Bagehot, Walter (1873). The English Constitution. 2nd ed. London: H.S. King.

- Balla, Steven J., and Christopher J. Deering (2013). ‘Police Patrols and Fire Alarms: An Empirical Examination of the Legislative Preference for Oversight’, Congress & the Presidency, 40:1, 27–40.

- Belke, Ansgar (2014). ‘Monetary Dialogue 2009–2014: Looking Backward, Looking Forward’, Intereconomics, 49:4, 204–11.

- Berman, Sheri, and Kathleen R. McNamara (1999). ‘Bank on Democracy: Why Central Banks Need Public Oversight’, Foreign Affairs, 78:2, 2–8.

- von Beyme, Klaus (2000). Parliamentary Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Braun, Benjamin (2017). Two Sides of the Same Coin? Independence and Accountability at the ECB. Berlin: Transparency International EU, available at https://transparency.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TI-EU_ECB_Report_DIGITAL.pdf (accessed 11 January 2018).

- Buiter, Willem H. (1999). ‘Alice in Euroland’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37:2, 181–209.

- Chang, Michele, and Dermot Hodson (2019). ‘‘Reforming the European Parliament’s Monetary and Economic Dialogues: Creating Accountability through a Euro Area Oversight Subcommittee’, in Olivier Costa (ed.), The European Parliament in Times of EU Crisis: Dynamics and Transformations. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 343–64.

- Chiru, Mihail (2018). ‘The Electoral Value of Constituency-Oriented Parliamentary Questions in Hungary and Romania’, Parliamentary Affairs, 71:4, 950–69.

- Claeys, Grégory, and Marta Domínguez-Jiménez (2020). How Can the European Parliament Better Oversee the European Central Bank? European Parliament: In-depth analysis requested by the ECON Committee PE 652.747.

- Claeys, Grégory, Mark Hallerberg, and Olga Tschekassin (2014). ‘European Central Bank Accountability: How the Monetary Dialogue Could Be Improved’, Bruegel Policy Contribution, 2014/04, available at http://bruegel.org/2014/03/european-central-bank-accountability-how-the-monetary-dialogue-could-be-improved/ (accessed 18 October 2017).

- Collignon, Stefan, and Sebastian Diessner (2016). ‘The ECB’s Monetary Dialogue with the European Parliament: Efficiency and Accountability during the Euro Crisis?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:6, 1296–312.

- Dawson, Mark, Adina Maricut-Akbik, and Ana Bobić (2019). ‘Reconciling Independence and Accountability at the European Central Bank: The False Promise of Proceduralism’, European Law Journal, 25:1, 75–93.

- De Haan, Jakob, and Sylvester C. W. Eijffinger (2000). ‘The Democratic Accountability of the European Central Bank: A Comment on Two Fairy-Tales’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 38:3, 394.

- Diessner, Sebastian (2022). ‘The Promises and Pitfalls of the ECB’s “Legitimacy-as-Accountability” Towards the European Parliament Post-Crisis’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28:3, 402–20.

- Eijffinger, Sylvester C. W., and Edin Mujagic (2004). ‘An Assessment of the Effectiveness of the Monetary Dialogue on the ECB’s Accountability and Transparency: A Qualitative Approach’, Intereconomics, 39:4, 190–203.

- Elgie, Robert (1998). ‘Democratic Accountability and Central Bank Independence: Historical and Contemporary, National and European Perspectives’, West European Politics, 21:3, 53–76.

- European Central Bank (2021). ‘Two Per Cent Inflation Target’, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/strategy/pricestab/html/index.en.html (accessed 6 December 2022).

- Fearon, James D. (1999). ‘Electoral Accountability and the Control of Politicians: Selecting Good Types versus Sanctioning Poor Performance’, in Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin (eds.), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 55–97.

- Ferrara, Federico M., Donato Masciandaro, Manuela Moschella, and Davide Romelli (2022). ‘Political Voice on Monetary Policy: Evidence from the Parliamentary Hearings of the European Central Bank’, European Journal of Political Economy, 74, 102143.

- Fontan, Clément, and David Howarth (2021). ‘The European Central Bank and the German Constitutional Court: Police Patrols and Fire Alarms’, Politics and Governance, 9:2, 241–51.

- Fraccaroli, Nicolò, Alessandro Giovannini, and Jean-François Jamet (2018). ‘The Evolution of the ECB’s Accountability Practices during the Crisis’, ECB Economic Bulletin, 5, 47–71.

- Fraccaroli, Nicolò, Alessandro Giovannini, and Jean-François Jamet (2020). ‘Central Banks in Parliaments: A Text Analysis of the Parliamentary Hearings of the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve’, ECB Working Paper Series No 2442.

- Fraccaroli, Nicolò, Alessandro Giovannini, Jean-François Jamet, and Eric Persson (2022). ‘Ideology and Monetary Policy. The Role of Political Parties’ Stances in the European Central Bank’s Parliamentary Hearings’, European Journal of Political Economy, 74, 102207.

- Fromage, Diane, and Renato Ibrido (2018). ‘The “Banking Dialogue” as a Model to Improve Parliamentary Involvement in the Monetary Dialogue?’, Journal of European Integration, 40:3, 295–308.

- Gros, Daniel (2004). 5 Years of Monetary Dialogue. Brussels: European Parliament, available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=26318979c146097083a8ae3bc0d3a66ea5587396 (accessed 20 March 2024).

- Hadfield, Gillian K. (1994). ‘Weighing the Value of Vagueness: An Economic Perspective on Precision in the Law Symposium: Void for Vagueness’, California Law Review, 82:3, 541–54.

- Harris, Joseph P. (1964). Congressional Control of Administration. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Höhmann, Daniel, and Ulrich Sieberer (2020). ‘Parliamentary Questions as a Control Mechanism in Coalition Governments’, West European Politics, 43:1, 225–49.

- Howarth, David (2004). ‘The ECB and the Stability Pact: Policeman and Judge?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 11:5, 832–53.

- Jourdan, Stanislas, and Sebastian Diessner (2019). From Dialogue to Scrutiny: Strengthening the Parliamentary Oversight of the European Central Bank. Brussels: Positive Money Europe, available at https://www.positivemoney.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2019_From-Dialogue-to-Scrutiny_PM_Web.pdf (accessed 17 February 2023).

- Kellermann, Michael (2016). ‘Electoral Vulnerability, Constituency Focus, and Parliamentary Questions in the House of Commons’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18:1, 90–106.

- Kiewiet, D. Roderick, and Mathew D. McCubbins (1991). The Logic of Delegation: Congressional Parties and the Appropriations Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ter Kuile, Gijsbert, Laura Wissink, and Willem Bovenschen (2015). ‘Tailor-Made Accountability Within the Single Supervisory Mechanism’, Common Market Law Review, 52:1, 155–89.

- Lastra, Rosa M. (2020). ‘Accountability Mechanisms of the Bank of England and of the European Central Bank’, European Parliament: Study Requested by the ECON Committee PE 652.744.

- Levy, Jack S. (2008). ‘Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference’, Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25:1, 1–18.

- MacMahon, Arthur W. (1943). ‘Congressional Oversight of Administration: The Power of the Purse. I’, Political Science Quarterly, 58:2, 161–90.

- Maricut-Akbik, Adina (2020). ‘Contesting the European Central Bank in Banking Supervision: Accountability in Practice at the European Parliament’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 58:5, 1199–214.

- Martin, Shane (2011). ‘Parliamentary Questions, the Behaviour of Legislators, and the Function of Legislatures: An Introduction’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17:3, 259–70.

- Massoc, Elsa (2022a). ‘How Do Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) Hold the European Central Bank (ECB) Accountable? A Descriptive Quantitative Analysis of Three Accountability Forums (2014-2021)’, SSRN Electronic Journal, available at https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4155627 (accessed 30 November 2022).

- Massoc, Elsa (2022b). How MEPs Hold the ECB Accountable. Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), available at https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/167901/version/V1/view (accessed 4 December 2023).

- Matland, Richard E. (1995). ‘Synthesizing the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5:2, 145–74.

- McCubbins, Mathew D., and Thomas Schwartz (1984). ‘Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms’, American Journal of Political Science, 28:1, 165.

- Mill, John Stuart (1861). Considerations on Representative Government. Web Edition. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide Library, available at https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/m/mill/john_stuart/m645r/ (accessed 26 February 2019).

- Norton, Philip (1993). Does Parliament Matter? Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Otjes, Simon, and Tom Louwerse (2018). ‘Parliamentary Questions as Strategic Party Tools’, West European Politics, 41:2, 496–516.

- Reichstein, Kenneth J. (1965). ‘Ambulance Chasing: A Case Study of Deviation and Control within the Legal Profession’, Social Problems, 13:1, 3–17.

- Saalfeld, Thomas (2000). ‘Members of Parliament and Governments in Western Europe: Agency Relations and Problems of Oversight’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:3, 353–76.

- van Santen, Rosa, Luzia Helfer, and Peter van Aelst (2015). ‘When Politics Becomes News: An Analysis of Parliamentary Questions and Press Coverage in Three West European Countries’, Acta Politica, 50:1, 45–63.

- Schillemans, Thomas, and Madalina Busuioc (2015). ‘Predicting Public Sector Accountability: From Agency Drift to Forum Drift’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25:1, 191–215.

- Sieberer, Ulrich (2011). ‘The Institutional Power of Western European Parliaments: A Multidimensional Analysis’, West European Politics, 34:4, 731–54.

- Strøm, Kaare (2000). ‘Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:3, 261–89.

- Trichet, Jean-Claude (2011). ‘Monetary Dialogue with the President of the ECB, Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON)’, European Parliament, available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/174379/20110711ATT23762EN.pdf (accessed 23 January 2023).

- Vliegenthart, Rens, and Stefaan Walgrave (2011). ‘Content Matters: The Dynamics of Parliamentary Questioning in Belgium and Denmark’, Comparative Political Studies, 44:8, 1031–59.

- Wiberg, Matti, and Antti Koura (1994). ‘The Logic of Parliamentary Questioning’, in Matti Wiberg (ed.), Parliamentary Control in the Nordic Countries: Forms of Questioning and Behavioural Trends. Helsinki: The Finnish Political Science Association, 19–43.

- Wyplosz, Charles, Stephen Nickell, and Martin Wolf (2006). ‘European Monetary Union: The Dark Sides of a Major Success’, Economic Policy, 21:46, 208–61.

- Zeitlin, Jonathan, and Filipe Brito Bastos (2020). SSM and the SRB Accountability at European Level: Room for Improvements? European Parliament: In-depth analysis requested by the ECON Committee, PE 645.747, available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2020/645747/IPOL_IDA(2020)645747_EN.pdf