Abstract

The aim of this article is twofold. Firstly, it offers a new definition of ‘mainstream’. Moving beyond understandings of the concept that focus exclusively on parties’ alternation in power, or their ideology/message, the article’s conceptualisation considers both supply and demand sides of politics. Hence, an attitudinal component to functional definitions is added. This implies that, to be called ‘mainstream’, certain attitudes must be shared by a majority of the public, and there must be no significant differences in their endorsement across political groups. Secondly, consideration is given to whether liberal-, social-democratic, and populist radical right (PRR) parties and attitudes meet this new reconceptualisation. While liberal- and, to a lesser extent, social-democratic parties and attitudes are indeed shown to be ‘mainstream’, the PRR is found to fall outside of the proposed definition, despite being ‘established’ on the supply side. The article concludes by underlining its wider theoretical implications.

The term ‘mainstream’ is widely used in political science, whether it is applied to parties, ideologies or policies. Equally, the idea that parties may move from some sort of marginal position in the party system to a more central one, in a process often dubbed ‘mainstreaming’, has been the object of increasing attention (Akkerman et al. Citation2016a; Albertazzi and Vampa Citation2021; Mudde Citation2019). However, while the importance of debates around who is ‘mainstream’ may seem obvious, many pundits and academics regularly refer to the ‘mainstream’ without giving much thought to its meaning. In addition to this, the handful of scholars who endeavoured to nail the ‘mainstream’ down do not agree on a clear and comprehensive definition of the term, let alone the process of mainstreaming. Consequently, these key concepts have too often been left undefined (Moffitt Citation2022: 385). Reaching an agreement about what counts as the ‘mainstream’ in contemporary Europe has been made especially hard by the sheer number of radical actors (on both the left and the right of the political spectrum) that have suddenly become coalitionable and started to access positions of power throughout the continent (Akkerman et al. Citation2016b).

We claim that having a clear and operationalisable definition of the ‘mainstream’ is paramount for at least two purposes. First, it prevents theoretical and empirical research from adopting the term uncritically; and, second, it encourages broader public reflection on the socio-political foundations of contemporary European democracies. Therefore, our article puts forward a novel definition of the ‘mainstream’ which takes into account both the supply and demand sides of politics, by adding an attitudinal component to functional definitions of the concept (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016; Meguid Citation2005, Citation2008). Ultimately, we aim to offer a definition of the ‘mainstream’ that can be operationalised and deployed to decide whatever ideas and parties this label can be applied to. To achieve this, the article will proceed as follows.

In the next section we discuss why previous understandings of the ‘mainstream’ fall short of what we need, if we are to understand contemporary political developments. Usages of the term that appear to privilege the supposed ‘moderatism’ or ‘centrism’ of ‘mainstream’ parties and ideas according to normative values are rejected; equally, we set aside any definitions focused exclusively on the notion of ‘legitimisation’, as this brings in too rich a catch. To overcome the difficulties we identify with previous understandings of the ‘mainstream’, we put forward a novel definition of the concept in the third section and explain how this can be operationalised. Among other conditions, we suggest that, to be called ‘mainstream’, certain attitudes must be shared by a majority of the public, and there must be no significant differences in their endorsement across political groups. Next, we justify our methodology and discuss the findings of the empirical part of our study, which analyses to what extent different party families (their parties and ideas) can be said to be ‘mainstream’, according to our conceptualisation.

This section presenting our findings is split into two sub-sections. In the first, we look at the supply side. We start by briefly covering the electoral performance and participation in government of populist radical right (PRR) parties (Mudde Citation2007): this party family is chosen as a case study as there is a question mark over whether it has completed its journey towards the ‘mainstream’ in Europe today. In the same section we treat the claim that centrist, centre-left and centre-right parties have regularly alternated in government after World War II as undisputed, hence referring to them as clear examples of mainstream parties, as far as elections and government participation are concerned. The fact that PRR parties regularly return to government in a majority of European countries, as we show in this part of the article, satisfies a purely functional interpretation of what should be considered ‘mainstream’. In this sense (i.e. from the perspective of the supply side of politics), PRR parties are now arguably part of the European mainstream.

In the second sub-section, we focus on attitudes. Here we assess whether populist, radical-right (i.e. nativist and authoritarian), liberal-democratic and social-democratic attitudes are sufficiently widespread and commonly endorsed to justify regarding them as ‘mainstream’. We find that, while this is indeed true of liberal-democratic and, to a lesser extent, social-democratic attitudes, the same cannot be said of populist ones, and even less so of nativist and authoritarian ones. Since populism, nativism and authoritarianism are all essential ingredients of PRR identity and ideology (Mudde Citation2007; Rooduijn Citation2014), we conclude this sub-section by arguing that the populist radical right still falls outside the ‘mainstream’. In other words, while many PRR parties are now ‘established’ in that they are regularly accessing power, their ideas and message cannot be said to have become ‘mainstream’. This is because radical-right attitudes are only endorsed by a minority of contemporary Europeans, and embracing both populist and radical-right attitudes still sets PRR supporters apart from the electorate at large.

Our article concludes by arguing that a holistic reconceptualisation of the ‘mainstream’ gives us the opportunity to test where each party family (and sub-family) is in relation to government participation and public opinion, by being both functional and attitudinal, and by considering both the supply and the demand sides of politics. Therefore, we invite comparativists to delve into the dynamic relationship between political parties, public opinion, and the broader political landscape to reach an understanding of the ‘mainstream’ that can accommodate the fast pace of change within party systems and societies today.

The problem(s) with the ‘mainstream’

As Katy Brown et al. (Citation2023: 164) have argued, ‘while many scholars have developed precise, compelling and useful definitions and analyses of the parties and politics themselves, the concepts of the mainstream and mainstreaming often remain vague or uncritical’. In other words, scholars have relied too much on their intuitive understanding of what ‘mainstream’ means (as noted by Akkerman et al. Citation2016b: 7; Moffitt Citation2022: 385; Mondon and Winter Citation2020: chapter 3), so that ‘mainstream, it would seem, simply exists’ (Kallis Citation2015: 6).

The studies focusing on supply-side politics – political behaviour, electoral support, and party policies – are the ones that have managed to define ‘mainstream’ in more specific terms; however, they have done so on a purely functional basis, thereby limiting the breadth of the definition. In this context, whether a party – and by extension the politics it represents – belongs to the ‘mainstream’ is decided purely based on its participation in government and/or good electoral results, both of which lead that organisation to play a central role in its party system (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016; Meguid Citation2005, Citation2008). By conflating the definitions provided by these works, we can say that, in this context, actors have been defined as ‘mainstream’ because they were ‘electorally dominant’ (Meguid Citation2005: 348), ‘typically governing’ (Meguid Citation2008: 46), or, at the very least, regularly alternating between government and opposition (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012: 250; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016: 974). By enjoying an ‘overall advantageous position in the system’ (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012: 250), these parties have been said to exercise particular influence over policies in their countries.

This purely functional understanding of the ‘mainstream’ has pros and cons. The main advantage is its clarity, which makes it easily operationalisable. When adopting this definition, researchers can easily make distinctions between two categories of parties: those who play a central role within their party systems (on the basis of their electoral success and/or ability to enter coalition governments or govern on their own) and everyone else (i.e. ‘challenger’ parties). The question that matters here, however, is why we should deploy the term ‘mainstream’ to refer to these parties in the first place. If the role a party plays in the system and its chances of sharing power are the focus of the discussion, then we can use the label ‘established’ instead. This is what Daniele Albertazzi and Davide Vampa (Citation2021: 283) mean in a recent book when they suggest that:

established parties would simply be those that routinely alternate in government […], are perceived as viable partners by other parties and show willingness to cooperate […]. On the contrary, challenger parties would be those with no prior experience of political office […] or that do not ordinarily participate in government.

Two conceptualisations of ‘mainstream’ that do take such ideas into consideration see either (1) ‘moderation/centrism’ or (2) the notion of ‘legitimisation’ as essential ingredients of it. In the first case, parties that are affected by a process of ‘mainstreaming’ are expected to moderate their positions and move towards the centre of the political spectrum; in the second case, parties benefit from a process of progressive legitimisation of their ideology and policy proposals through which they can overcome their ‘pariah’ status.

Pop-Eleches’ (Citation2010) definition of ‘mainstream’ falls into the first category. For him: ‘A political party is classified as mainstream if its electoral appeal is based on a recognisable and moderate ideological platform rather than on the personality of its leader and/or extremist rhetoric’ (Pop-Eleches Citation2010: 225; our emphasis). Similarly, Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah De Lange and Matthijs Rooduijn say that:

the term ‘mainstream’ can encompass programmatic and positional centrism, the high salience of socioeconomic issues, and behaviour and stances that show commitment to the principles of liberal democracy and to the formal and informal rules of the political game. (Akkerman et al. Citation2016b: 7; our emphasis)

While these definitions are helpful, insofar as they bring the supply side of politics into the equation by focusing on whatever parties themselves are willing to offer (i.e. their ideology and proposals), in the hands of these authors the concept of ‘mainstream’ remains static and normative. Static, because parties are here classified according to the extent to which they embrace a set of fixed positions which are seen as typical of political centrism; normative, because ‘moderate’ and ‘centrist’ conjure up ideas of ‘rationality’, ‘pro-democracy’, and ‘good behaviour’. Inevitably, therefore, ‘non-mainstream’ parties end up being tarred with the same brush, therefore implying that they must be irrational, irresponsible, and/or untrustworthy. The risk, in these cases, is to turn ‘mainstream’ into a reflection of whatever qualities the writer happens to see as desirable at a specific moment in time.

What about ‘mainstreaming’ as ‘legitimisation’ (and, consequently, ‘mainstream’ as that party/idea/politics which is, or has become, ‘legitimate’)? This is how Brown et al. (Citation2023) see the concept. For them, mainstreaming is:

the process by which parties/actors, discourses and/or attitudes move from marginal positions on the political spectrum or public sphere to more central ones, shifting what is deemed to be acceptable or legitimate in political, media and public circles and contexts. (Brown et al. Citation2023: 170; our emphasis)

We reject basing the definition of the ‘mainstream’ on the notion of ‘legitimisation’, too, since this would bring in too rich a catch, raising many doubts as to the usefulness of the concept. For instance, according to this definition, one-issue parties attracting tiny percentages of support and never managing to impact on the politics of their country and/or share power (say, ‘parties of car drivers’ or ‘parties of pensioners’, both of which are a reality in Europe) would have to be classified as ‘mainstream’, since no one questions that they are legitimate political actors. Indeed, according to this definition, only the anti-democratic extreme left and extreme right would end up populating the ‘non-mainstream’ brigade, which would make the ‘non-mainstream’ category very sparse indeed.

Nonetheless, those who invite us to conceive of ‘mainstream’ as a concept that is ‘constructed, contingent, and fluid’ (Brown et al. Citation2023: 166; original emphasis; see also Moffitt Citation2022: 385–86; Mondon and Winter Citation2020: 115) are clearly on to something.

We believe that a way out of the impasse can in fact be found which:

moves beyond the ‘purely functional’ approach, by refusing to use ‘mainstream’ merely to acknowledge who is ‘established’ and who is a ‘challenger’;

captures the mainstream’s contingent and fluid nature;

is operationalisable and not ‘too stretched’.

As for (1), the definition we provide below takes into account both the role of parties in the system and their ideas. Concerning (2), we do not take for granted that the specific ideologies that are widely regarded as ‘mainstream’ in Europe today (for instance, liberal-democratic values) should necessarily continue to be seen as such regardless of location and specific historical period. In fact, there have been contexts – such as Italy or Germany in the 1930s – in which an extreme phenomenon such as fascism could have been argued to have become ‘mainstream’ (Kallis Citation2015). Finally, concerning (3), we put forward a definition of ‘mainstream’ that is empirically testable and sets clear boundaries between what is ‘in it’ and what remains ‘outside’.

summarises this discussion. As we emphasise in the next section, the solution we have in mind brings the demand side of politics into the equation by recognising the importance of whatever the people, who are at the receiving end of political messages, think and subscribe to.

Table 1. The concept of the ‘mainstream’ in political science literature: pros and cons of different approaches.

Bringing the demand side in: a bi-dimensional and operationalisable conceptualisation

In order to develop a more sophisticated, comprehensive, and operationalisable conception of the ‘mainstream’, we propose to bring the demand side of politics in. Indeed, a crucial actor is missing from previous attempts at conceptualising the ‘mainstream’: the public, with its ideas. We believe that the attitudes that the receivers of party messages are seen to embrace, in a specific ‘here’ and ‘now’, should be put at the centre of what we mean by ‘mainstream’. Our answer to the question of whether a political phenomenon can be defined as ‘mainstream’ even when the ideas it propagates are shared by a minority of the public will therefore be an emphatic ‘no’.

Such an approach can help us get out of the normative hole we have found ourselves in, and challenges us to address the problem of operationalisation. Hence, we provide a bi-dimensional definition of ‘mainstream’ by adding an ‘attitudinal’ component to the previous ‘functional’ definition, which, as we emphasise, is already easily operationalisable. Based on our conceptualisation, a set of ideas can be considered as belonging to the ‘mainstream’ if the following conditions are met:

It is represented by one or more ‘established parties’. These parties are ‘electorally dominant’ (Meguid Citation2005: 348) and ‘typically governing’ (Meguid Citation2008: 46), or, at the very least, regularly alternating between government and opposition (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012: 250; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016: 974).

But also:

(b1) it is embraced by a majority of the public,

and

(b2) there is no statistically and substantively significant difference in terms of endorsement of these ideas between supporters of the respective parties and everyone else.

illustrates our bi-dimensional definition of the ‘mainstream’.

Table 2. Bi-dimensional definition of the ‘mainstream’ in politics and societies.

In this sense, according to us, the ‘mainstream’ status is met when both (1) parties (i.e. actors) and (2) ideas have become established in politics and societies.Footnote1 As for the attitudinal component, the proposed criteria (b1) and (b2) should protect us from the risk of providing an overly stretched conceptualisation. Indeed, in our view, the fact that the key ideas characterising a political family – say, social-democratic parties – are endorsed by a majority of the public is not sufficient by itself. We believe that, in order to qualify as ‘mainstream’, such ideas must also be embraced in a highly similar manner across different political groups. Of course, criteria (b1) and (b2) are likely to occur simultaneously. However, there may be a situation in which some ideas are embraced by a majority of the public, but there is still a remarkable difference in their endorsement between supporters of the parties that advocate such ideas and everyone elseFootnote2 (because the intensity with which political groups embrace such ideas varies and the importance they place on such ideas also varies).

The following section shows how we went about using our definition to decide whether certain political families existing in Europe today, and the ideas they put forward, can be regarded as ‘mainstream’.

Research design

Case selection

We test our bi-dimensional definition of the ‘mainstream’ on three case studies: populist radical right (PRR), liberal-democratic and social-democratic parties and attitudes.

The PRR has been chosen as a case study because of the amount of academic interest its alleged ‘mainstreaming’ has attracted in recent years. During the first decade of the twenty first century it was common to question the durability of populism (Meny and Surel Citation2002: 18; Taggart Citation2000) and the ability of populist parties to be effective forces in government (Heinisch Citation2003), so much so that the terms commonly deployed to define them (e.g. ‘niche’, ‘outsider’, and/or ‘challenger’) (Akkerman et al. Citation2016b: 7–8; De Vries and Hobolt Citation2020) all stressed their alleged ‘non-mainstream’ nature. Indeed, one of the most interesting claims put forward by Tjitske Akkerman et al. in a book entirely dedicated to the alleged transformation of PRR parties was precisely that these ‘hardly move into the mainstream’ (Akkerman et al. Citation2016c: 47).

In recent years, however, PRR parties have proved themselves capable to join government coalitions, and in several cases to return to power more than once (Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2015). In a recent book, Vampa and Albertazzi (Citation2021: 283–84) went so far as to call populist parties – particularly of the radical right – ‘the new mainstream’, precisely due to their apparent ability to return to government time and again. There is now a rich literature showing that: (a) electoral support for PRR parties remains stable and important throughout the continent; (b) PRR parties increasingly participate in government coalitions, and (c) they have influenced other parties’ platforms through a ‘contagion effect’ (Rooduijn et al. Citation2023; Vittori and Morlino Citation2021: 39). In this article, we suggest referring to parties such as the ones studied by these scholars as ‘established’, hence leaving the question of whether the politics they represent has also become ‘mainstream’ to empirical research.

Besides the PRR, we consider two further case studies which are widely regarded as the embodiment of the ‘mainstream’. Let us consider, once again, the definition offered by Tjitske Akkerman et al. (Citation2016b: 7). Here the concept of the ‘mainstream’ is associated with ‘programmatic and positional centrism’, ‘the high salience of socioeconomic issues’, and ‘commitment to the principles of liberal democracy’ (our emphasis). Following this logic, in otherwise valuable research (e.g. Rooduijn Citation2016), parties and ideas are regarded as ‘mainstream’ simply because they belong to the traditional party families inspired by liberal, centre-left (e.g. Social-Democratic), and/or centre-right (e.g. Christian Democratic and Conservative) values. While there is no doubt that centre-left and centre-right parties are still part of the European mainstream according to the functional component of our definition, as they regularly alternate in government, whether the ideas that we intuitively consider ‘mainstream’ – such as support for liberal democracy and social democracy – can be considered as such in European societies today should be open to scrutiny. This is precisely what we assess below.

Operationalisation: questions, data and methods

We claim that the participation in government of liberal, conservative and social-democratic parties in Europe after World War II is a fact that does not need debating or demonstrating. What we cannot take for granted, however, is the assertion that PRR parties have also become ‘established’ in many European countries, and to a similar extent. Hence we will endeavour to clarify the ‘established’ nature of the PRR first, before moving to the most important part of our discussion: the assessment of whether populist radical right attitudes (endorsed by PRR parties), liberal-democratic attitudes (endorsed by all parties that are usually considered ‘mainstream’, including liberal, centre-left, and centre-right parties) and social-democratic attitudes (endorsed by centre-left parties) all satisfy the demand-side component of our definition (). The empirical analysis will allow us to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. Are: (a) PRR, (b) liberal-democratic, (c) social-democratic attitudes embraced by a majority of contemporary Europeans?

RQ2. Is there a significant difference between: (a) PRR, (b) liberal-democratic, (c) social-democratic voters on the one hand, and other voters on the other, when it comes to endorsing PRR, liberal-democratic, and social-democratic attitudes, respectively?

To explore whether these different sets of attitudes are in fact ‘mainstream’ across contemporary Europe we rely on the 10th wave of the European Social Survey – ESS (September 2020–May 2022), as released in July 2023. This wave allows us to investigate liberal-democratic, social-democratic and PRR attitudes across 23 European countries, fourteen in Western Europe (WE) and nine in Central-Eastern Europe (CEE).Footnote3

The PRR set of ideas comprises three distinct tenets: populism, nativism and authoritarianism (Mudde Citation2007; Rooduijn Citation2014). As for populist attitudes (Marcos-Marne et al. Citation2022), the seminal ‘populist attitude scale’ conceived by Agnes Akkerman et al. (Citation2014) included six items for their measurement. More recent studies have included even more (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020; Schulz et al. Citation2018). However, the 2020–22 round of the ESS contains only two questions that can measure these attitudes. The questions capture the two essential core elements of populist ideology, in line with the ideational approach as described by Mudde (Citation2004). These are: people centrism (the idea that politics should be an expression of the will of the people and that this must immediately be implemented) and anti-elitism (the idea that corrupt elites are working behind the scenes to deprive ‘the people’ of their voice) (). This still leaves out the key populist notion that ‘the people’ should be regarded as a homogeneous and virtuous group. Nonetheless, by using the 10th wave of the ESS, we can conduct a very large-N investigation drawing on current data from countries in all European regions – and this is a considerable advantage. Furthermore, the ESS dataset comprises items that can be used as proxies of the other key PRR attitudes besides populism: nativism and authoritarianism.Footnote4 For this purpose, we selected eight more questions ().

Table 3. ESS items regarding populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal- and social-democracy attitudes.

We chose the ESS items to be employed as proxies of liberal- and social-democratic attitudes by drawing on the multidimensional conception of democracy introduced by Ferrín and Kriesi (Citation2016). Five of the selected questions capture liberal-democratic attitudes, whereas the other two are typical of a social-democratic conception of democracy ().

We recoded all the questions in so that higher values corresponded to higher populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal-democratic and social-democratic attitudes. Therefore, in the second empirical section we are able to answer RQ1 by revealing whether distinct sets of ideas are embraced by a majority of contemporary Europeans.

In order to answer RQ2, we created five indexes of populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal-democratic and social-democratic attitudes for use as dependent variables in multilevel linear regression models. To do so, we simply added the respective (recoded) variables and then divided the results by the number of variables. Finally, we rescaled the five indexes we had obtained down to a [0,1] range. Cronbach’s α varies from 0.61 (authoritarianism scale) to 0.84 (nativism scale).Footnote5

The independent variables are dichotomous variables indicating whether the respondent is a PRR voter (models 1–3), a liberal-democratic voter at large (i.e. a liberal, centre-left or centre-right voter, model 4), or a social-democratic voter (model 5). As is customary, we controlled for sociodemographic variables (gender, age, level of education, occupational status), left–right self-placement, and residence (on a sliding scale from urban to rural). We also included two additional control variables: trust towards one’s national parliament and satisfaction with democracy (on the logic behind their inclusion see, for instance, Van Hauwaert and van Kessel Citation2018). Finally, our multilevel models also contain a country-level dummy variable indicating whether the respondent’s country is in WE or in CEE.

Findings

The supply side

We start by briefly covering the electoral performance and participation in government of PRR parties, assessing whether they fulfil the functional criterion of our bi-dimensional definition of ‘mainstream’ (). As anticipated, we do not cover centrist, centre-left and centre-right parties in this section, thereby treating the claim that they have regularly alternated in government as undisputed.

We rely on the latest iteration of the PopuList dataset (Rooduijn et al. Citation2023) to identify European PRR partiesFootnote6 (Mudde Citation2007) (). To be clear, we consider PRR parties to be those that the PopuList categorises as ‘populist’ and ‘far right’. Close examination of the definitions employed in the expert survey reveals that the label ‘far right’ is actually applied to parties that fit Mudde’s (Citation2007) conceptualisation of the radical right, that is parties that are nativist and authoritarian. Therefore, the PopuList labels as ‘populist’ and ‘far right’ those parties that Mudde originally described as ‘populist radical right’.

Table 4. The populist radical right on the supply side.

shows that, over the last two decades, which have been marked by a PRR wave (Mudde Citation2019: chapter 1), these parties have won first-order national elections in seven countries, of which one, Italy, is among the largest European countries. Furthermore, in another seven countries a PRR party has ranked second at least once over the last twenty years. While electoral performance is interesting, ultimately we follow De Vries and Hobolt (Citation2012), Hobolt and Tilley (Citation2016), and Meguid (Citation2005, Citation2008) in adopting alternation in government as the sufficient criterion to distinguish between ‘established’ and ‘challenger’ parties.

The analysis reveals that PRR parties have entered cabinets in fourteen countries, that is, in a majority of those European countries where this party family exists. Most of the countries in which no PRR party has participated in government as yet are characterised by either: (a) a plurality/majoritarian electoral system (e.g. the United Kingdom and France), which makes it harder for non-established parties to become established or (b) having had direct experience of an authoritarian government in the recent past (e.g. Germany, Portugal, and Spain), which makes radical-right politics less attractive to the electorate (see Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019: 15; Hutter et al. Citation2018: 14).

To sum up, PRR parties have become coalitionable in a majority of European countries. The fact that PRR parties regularly return to government and occupy an ‘overall advantageous position in the system’ (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012: 250) satisfies a purely functional interpretation of what is ‘mainstream’. Hence, we can conclude that the populist radical right is part of the contemporary European mainstream as far as the supply side is concerned.

If the populist radical right is increasingly allowed to access power, what do we make of the ideas it puts forward? Clearly, given our definition of the ‘mainstream’, our next task will be to assess whether PRR ideas can be classified as such, too. This will be the objective of the next sub-section, which provides an overview of PRR, liberal-democratic and social-democratic attitudes across Europe, leading to providing an answer to RQ1. Once this is accomplished, the following step will be a discussion of our regression models. These models make it possible to assess whether supporting PRR, liberal-democratic or social-democratic parties predict significantly higher endorsement of PRR, liberal-democratic or social-democratic attitudes, respectively (compared to the rest of the electorate). This analysis will allow us to answer RQ2.

The demand side

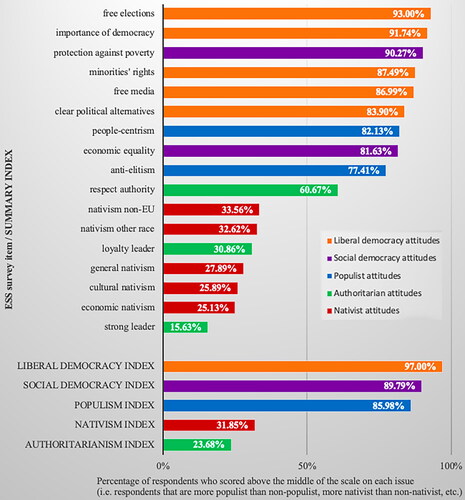

We start by evaluating whether populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal-democratic and social-democratic attitudes are embraced by a majority of Europeans. To do this, we need to verify whether more than 50% of respondents scored above the midpoint of the scale on each issue, i.e. whether or not a majority of respondents is characterised by populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal-democratic and/or social-democratic attitudes, as the case may be.

Our analysis shows that, on an aggregate European level, 82% and 77% of respondents scored above the middle of the scale on the people-centrism and anti-elitism variables, respectively (). Hence, these populist attitudes are embraced by most contemporary Europeans (RQ1a). Furthermore, a country-by-country analysis confirms that people centrism and anti-elitism are widespread throughout the whole of Europe, as the percentage of respondents who scored above the midpoint of the scales exceeds 62% in each of the 23 countries (see Online Appendix III). In short, commitment to populist ideas appears strikingly high. We cannot rule out that these very high percentages may be due to the specific wording of the ESS populism-related items. Nor can we rule out that the percentages would be different if alternative operationalisations of populist sentiments were used. Still, these findings are consistent with previous studies that, by using other items, provided evidence of populist attitudes being widely shared among European societies, as well as in North and South America (Hawkins et al. Citation2012, Citation2020; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020).Footnote7

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents who scored above the middle of the scale on the ESS items concerning populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal- and social-democracy attitudes, in descending order. N = 47,602–49,025.

Note: Percentages calculated using the analysis weight (anweight) available in the ESS. Descriptive statistics and percentage distributions of all variables in are reported in Appendix II.

The situation changes as soon as attention shifts specifically to radical-right attitudes. After all, as Mudde (Citation2007) points out, populism is the least important feature of PRR ideology, with nativism and authoritarianism playing a considerably more important role for this sub-family (on this point see also, e.g. Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Citation2022). When it comes to nativist and authoritarian attitudes, the data show that, except for the ‘respect authority’ variable, these are only supported by a minority of Europeans.

Indeed, the percentage of respondents who scored above the midpoint on the scales of nativist attitudes ranges between 25% (‘economic nativism’) and 34% (‘nativism non-EU’), therefore remaining well below 50% (). The exception is represented by the Visegrad countries (especially the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia) and Greece. Only here do a majority of interviewees appear to hold nativist attitudes.

A similar conclusion is reached concerning authoritarianism, although there are important differences between the three variables that are meant to measure it. Admittedly, almost 61% of respondents scored above the middle of the scale on ‘Obedience and respect for authority’ (); however, this is the only ‘ingredient’ of authoritarianism that performs rather well in this sense. Hence, the percentage of interviewees who score above the middle of the scale drops to 31% on the ‘loyalty leader’ variable and 16% on the ‘strong leader’ one. Moreover, the percentage of respondents who regard loyalty towards the country’s leader as a matter of major importance and find having a strong leader who is above the law acceptable is low, and below 50% in all countries (Online Appendix III).

Therefore, while populist attitudes are embraced by a majority of the contemporary European public, as we have seen, authoritarianism and nativism (even more crucial ‘ingredients’ of PRR ideology) are not. The percentage of respondents who score above the middle of the scale on nativism is ultimately 32%; for authoritarianism it is 24% – while it is 86% for populism. These results are consistent with previous studies: those that have provided evidence of how widespread populist attitudes are (Hawkins et al. Citation2012, Citation2020; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020) and those showing that nativist and authoritarian attitudes enjoy considerably less support (Crulli and Viviani Citation2022; Donovan Citation2019).

What about those attitudes that we normally assume must be ‘mainstream’? – and the percentage distributions in Online Appendix II – shows that Europeans are in fact very committed to the values of liberal democracy (RQ1b) and social democracy (RQ1c). Indeed, the percentage of respondents scoring above the midpoint on the scale ranges between 82% (‘economic equality’) and 93% (‘free elections’) – always consistently above 80%. The distribution of all liberal-democracy items is evidently skewed to the right, with most respondents choosing 10, i.e. the highest value on the scale. Hence, only one ‘ingredient’ of PRR ideology – ‘people centrism’ – can match the popularity of liberal- and social-democratic values in Europe today.

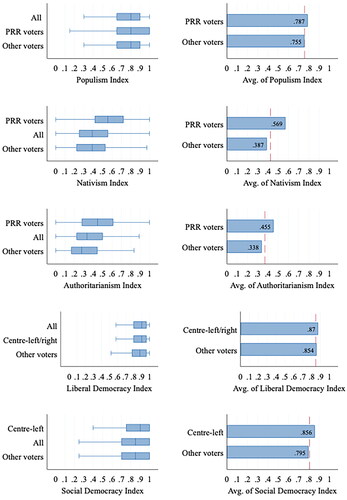

In order to answer our next research question (RQ2), we first plotted the boxplots and the averages of the five indexes over different groups of respondents to the ESS. In the cases of the populist, nativist, and authoritarian indexes, the groups were: all voters, PRR voters, and other voters. In the case of the liberal democracy index, the groups were: all voters, centre-left/right voters (including voters of liberal, centre-left and centre-right parties) and other voters. In the case of the social democracy index, the groups were: all voters, centre-left voters and other voters.Footnote8

We notice that there is a gap between the median/average PRR voter and the median/average European voter; however, this is low on the populism index, whereas it is more noticeable on the authoritarianism and nativism indexes (). This divide is especially pronounced concerning nativism: both the median and the average of PRR voters on the nativism index are slightly below 0.6, whereas for all voters these values drop to just above 0.4.

Figure 2. Boxplots and averages of the summary indexes of populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal- and social-democracy attitudes. Comparison between supporters and non-supporters of the relevant parties.

Note: Descriptive statistics calculated using the analysis weight (anweight) available in the ESS. Red lines mark the overall means.

Turning to the other two sets of ideas, there is practically no difference across the groups in terms of the liberal democracy index. This suggests that the level of support for liberal-democratic attitudes is (very) high, regardless of party affiliation. Lastly, although there is a gap between the median/average centre-left voter and the median/average European voter concerning social-democratic values, this gap is much narrower than the one observed between PRR voters and the others, when assessing radical-right attitudes.

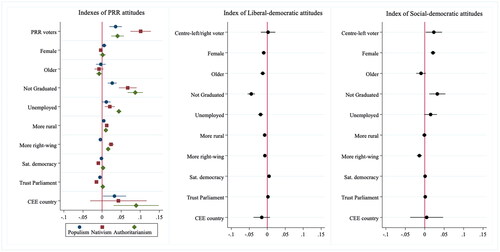

Finally, we ran our short series of multilevel linear regression models (), to fully assess RQ2. The regression analysis shows that voting for a PRR party predicts higher populist (β = 0.036), nativist (β = 0.101), and authoritarian (β = 0.041) attitudes in a significant manner, even controlling for sociodemographic, contextual, and political determinants. As we were expecting after the exploratory descriptive analysis, the coefficients are higher in the models with radical-right attitudes as dependent variables, particularly in the model explaining nativist attitudes. We can therefore say that PRR supporters differ significantly from other voters, particularly regarding authoritarian and nativist attitudes (to a lesser extent in terms of their populism) (RQ2a).

Figure 3. Coefficient plots of multilevel linear regression models explaining populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal and social democracy attitudes in contemporary Europe.

Note: Regression models run using the analysis weight (anweight) available in the ESS. 5-95 Cis displayed.

Online Appendix V reports the full regression outputs.

The model with the liberal democracy index as dependent variable confirms that being a supporter of those liberal, centre-left and centre-right parties that are usually considered to belong to the ‘mainstream’ does not affect support for liberal-democratic stances in any statistically significant manner (RQ2b). Instead, voting for a centre-left party predicts slightly higher social-democratic attitudes in a statistically significant manner. However, even here, the coefficient is too low (0.02 against a constant of 0.84) to indicate a substantive difference between social-democratic voters and the others (RQ2c).Footnote9

Therefore, we have found solid evidence that social-democratic, and especially liberal-democratic, attitudes match our criteria concerning what counts as the ‘mainstream’ in attitudinal terms. Unlike radical-right (i.e. nativist and authoritarian) attitudes, liberal-democratic ideas are embraced by an overwhelming majority of contemporary Europeans. Furthermore, there is not any difference in terms of support for liberal-democratic attitudes between voters and non-voters of the parties that explicitly advocate for a liberal-democratic conception of democracy. On the other hand, the low level of Europeans’ support for radical-right ideological features and the great divide that still exists between PRR voters and the rest of the electorate in terms of such attitudes suggest that the populist radical right is not mainstream as far as the demand side is concerned.

Robustness checks

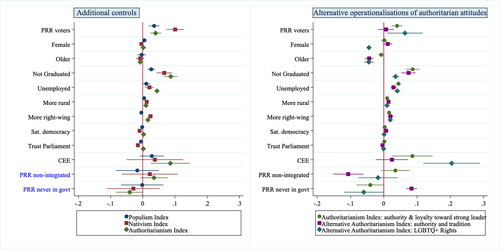

We conducted a series of additional checks to test whether our findings – especially on PRR attitudes – were biased due to: (1) the models’ specifications; (2) the lack of some relevant predictors; and/or (3) the way we constructed the summary indexes.

First, we performed the regression analysis again by running country fixed effects models (Online Appendix VI). The results were almost identical to those just expounded upon.

As for the second point, we replicated our main regression analysis by adding two country-level dummy variables: the first measures whether the PRR has been in government at least once in a country, and the second whether the PRR is ‘integrated’ in the system. The latter test is based on the conceptualisation and classification of ‘integrated’ and ‘non-integrated’ populist parties provided by Mattia Zulianello, where ‘integrated’ means that the party is involved in cooperative interactions at the systemic level (Zulianello Citation2020: 335–40). We deemed these two variables to be potentially relevant predictors because it seems logical to expect PRR attitudes to be more widely shared among the electorate in countries where PRR parties are more legitimised, having been in government and/or being ‘integrated’. Interestingly, however, the divide between PRR voters and the others is not altered by the introduction of these two variables, even though authoritarian attitudes appear weaker in countries where the PRR has never governed (left side of ). Therefore, there are no major differences between contexts where the PRR is ‘integrated’ and those where it remains on the fringe, in Zulianello’s (Citation2020) sense.

Figure 4. Robustness checks: multilevel linear regression models explaining PRR attitudes with additional controls (left-side) and multilevel linear regression models explaining different sets of authoritarian attitudes.

Note: Regression models run using the analysis weight (anweight) available in the ESS. 5-95 Cis displayed.

Online Appendix VI reports the full regression outputs.

Lastly, we needed to satisfy ourselves of the appropriateness of the authoritarianism index. Cas Mudde’s conception of ‘authoritarianism’, on which the definition of the PRR is founded, is rather broad. According to him, authoritarianism is ‘the belief in a strictly ordered society, in which infringements of authority are to be punished severely’ (Mudde Citation2007: 23). We previously operationalised this ideological tenet by resorting to three ESS items: one deals with obedience and respect for authority, and the other two with loyalty to a strong leader (). These three items turned out to constitute a coherent mindset (based on the PCA reported in Online Appendix I). However, it could be argued that, while the item on obedience and respect for authority fits Mudde’s definition well, the other two are more marginal to authoritarianism as conceived by this author. Therefore, we conducted a second PCA, this time excluding the two items on leadership, while adding one on the importance of tradition, as well as three on the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals (the extension of which is seen as contrary to a ‘strictly ordered society’ by many PRR actors). This new PCA resulted in four components. The populist and nativist dimensions are the same, whereas authoritarianism attitudes are ‘split’ into two components. The variables on obedience and respect for authority and on the importance of tradition load high on the same component; the three items on the perception of LGBTQ+ people load on another one. Based on these results, we created two new alternative measures of authoritarianism (by following the method previously described) and used them as dependent variables in further multilevel regressions (right side of ).

The results show that PRR voters support the rights of LGBTQ+ people less than other European voters. The gap in terms of respect for authority and importance of tradition is instead quite narrow and not statistically significant. Still, this result should be interpreted with caution: the number of countries in the respective model is lower, because the question on the importance of tradition was not asked in Austria, Germany, Spain, Poland and Sweden.

Despite these nuances between different operationalisations of authoritarian attitudes, all in all the robustness checks corroborate the overall validity of our results.

Discussion and conclusions

Our research has shown that populist and, even more so, radical-right (i.e. authoritarian and nativist) attitudes set PRR voters apart from the electorate at large. Moreover, radical-right attitudes are endorsed by a minority of Europeans and enjoy much lower levels of support than liberal and social-democratic ones. Therefore, if there is more to the meaning of ‘mainstream’ than just the ability of political parties to access power (i.e. to be seen as partners of government by other parties in the system), the populist radical right still cannot be considered fully as part of the mainstream today. Hence, on the basis of this analysis, we can define the populist radical right as ‘established but not mainstream’ in contemporary European politics. In other words, while this sub-family is part of the establishment in terms of being seen as a potential governing partner by other party families (especially the centre-right), it remains at the margins of the attitudinal mainstream – at least for now (). Whether this description also captures the situation of other families or sub-families (e.g. the radical left) is a matter for future empirical research.

Table 5. Outcome of the comparative analysis evaluating the extent to which three political families can be considered part of the contemporary European ‘mainstream’.

Our research’s main contribution, however, is not about the extent to which we are now able to clarify whether the populist radical right can be said to have become ‘mainstream’. Arguably, this is just an interesting by-product of our novel definition and operationalisation of the concept of ‘mainstream’. Hence, we argue that our holistic reconceptualisation of the ‘mainstream’ gives us the opportunity to test where each party family (and sub-family) sits in relation to government participation and public opinion, by being both functional and attitudinal, and by considering both the supply and the demand sides of politics.

We recognise our intellectual debt to those scholars who have focused our attention on the need to conceive of the ‘mainstream’ as constructed, contingent, and fluid (Brown et al. Citation2023; Moffitt Citation2022; Mondon and Winter Citation2020). In line with this intuition, any assessment of the kind we have offered in this study only provides a snapshot of where a party family is at a specific moment in time. It obviously does not exclude that things might look very different if assessed again, say, in ten years from now. This ‘situational’ character of our conceptualisation, i.e. the fact that the ‘mainstream’ is geographically and temporally bounded, suggests that many paths towards ‘mainstreaming’ exist. A non-mainstream party family can (intentionally) become more similar to the then current mainstream, thereby increasing its chances of entering it. Otherwise, the meaning of ‘mainstream’ itself can change to encompass the formerly ‘non-mainstream’, due to the inclusion of non-established parties in government, attitudinal shifts affecting the public, or both. In short, whatever can be included in the ‘mainstream’ is not fixed once and for all, due to changes in the structure of party competition and public opinion. Mainstreaming can be a consequence of ‘catch-allism’: that is, the blurring of ideological positions to hunt for votes outside the classe gardée and eventually achieve electoral success and power. However, ‘mainstream’ should not be seen as a mere synonym for ‘catch-all party’ (Kirchheimer, Citation1966). Firstly, as stressed throughout this article, we do not conceive of the ‘mainstream status’ as characterising individual parties. Rather, we see it as an attribute of political families/ideologies, dependent on both actors (i.e. parties) and ideas (i.e. public opinion). Secondly, abandoning the commitment to a thick ideology to conquer new electoral bases is neither (1) a sufficient nor (2) a necessary condition to become ‘mainstream’. As for (1), consider populism: the quintessence of a thin ideology. We showed that the core ideas of populism are endorsed by most contemporary Europeans, but distinctions in the degree of such endorsement still exist between different groups of voters. Regarding (2), there have arguably already been situations in which ‘the mainstream’ coincided with a clear and strong ideology supported by established political forces and embraced in a highly similar manner across socio-political groups, even though societal opposition to it existed. An example of this may be Christian Democracy in several European countries in the twentieth century. Of course we lack appropriate survey data to test this argument.

In conclusion, we offer our reconceptualisation of the ‘mainstream’ as a contribution to future research agendas investigating not only specific party families but, more broadly, what is meant by ‘mainstream’ at specific moments in time. In other words, by challenging prevailing paradigms and expanding our understanding of the ‘mainstream’, our study invites comparativists to delve into the dynamic relationship between political parties, public opinion, and the broader political landscape. Future comparative research drawing on our conceptualisation could also, and importantly, gauge geographical and temporal variations in the degree to which various party families/ideologies qualify as ‘mainstream’, including outside the European continent, to which we have restricted our investigation.Footnote10 Ultimately, our contribution underscores the crucial importance of re-evaluating the meaning of ‘mainstream’ in the context of rapidly evolving socio-political dynamics.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (971.5 KB)Acknowledgements

A draft version of this article was discussed at the Department of Politics of the University of Surrey with members of staff and research students. We thank the Politics community in that institution for providing useful feedback at the start of the project. A previous version of this article was also presented at the 2023 ECPR Conference (Prague) and the 2023 SISP Conference (Genoa). We are grateful to the participants in both events, especially Mattia Zulianello, Sofia Ammassari, and Gianluca Piccolino, for their suggestions. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers whose thorough criticisms and observations have helped us improve the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mirko Crulli

Mirko Crulli is a research fellow at the Department of Political Science, LUISS University. His main research interests are cleavage politics, electoral behaviour, public opinion, populism, and political geography. He has published on these themes in international scientific journals, including The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Comparative European Politics, and European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology. [[email protected]]

Daniele Albertazzi

Daniele Albertazzi is Professor of Politics and Co-Director of the Centre for Britain and Europe at the University of Surrey. The major strands of his work have been about populism in Western Europe, party organisation, Italian politics, and the communication strategies and mass media use of political parties. His most recent books are Populism and New Patterns of Political Competition in Western Europe (Routledge 2021), co-edited with Davide Vampa, and Populism in Europe—Lessons from Umberto Bossi’s Northern League (Manchester University Press, 2021), co-written with Davide Vampa. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Although the main actors involved in our conceptualisation are parties and the public/the electorate, the media are also indirectly involved. Indeed, people’s ideas are also shaped – to an extent – through and by the media.

2 As we will see in the second part of the article, this is the situation characterising populist attitudes in contemporary Europe.

3 There are 23 European countries participating in the 10th ESS round in which PRR, liberal-democratic and social-democratic parties exist: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland.

4 In other words, although the ESS10 only provides two questions that can be considered as proxies of populist attitudes, it remains our best option. To the best of our knowledge, it is the only recent survey conducted at the European level that:.

comprises items that can be used as proxies of all the attitudes relevant to this study: populist, nativist, authoritarian, liberal- and social-democratic;.

has been fielded in almost all European countries;.

comprises enough PRR voters to allow us to conduct statistically significant and meaningful analyses.

5 We also ran a principal component analysis (PCA) on the 10 ESS items that cover populist, nativist, and authoritarian attitudes, which identified three components characterised by an Eigenvalue greater than 1 (Online Appendix I). These were the three expected dimensions of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism.

6 However, we have also crosschecked the PopuList with another accurate (albeit less up-to-date) classification of populist parties: Zulianello (Citation2020).

7 To corroborate our argument further, we considered two national surveys: wave 20 of the British Election Study (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2020) and the 2022 Italian National Election Study (Vezzoni et al. Citation2023). These comprise the items used to construct the established Akkerman scale. The percentage of respondents who scored above the middle of this scale turned out to be 66% in Great Britain and 72% in Italy, which supports the claim that populist ideas are endorsed by a majority of individuals across Europe.

8 The ‘liberal’ group comprises parties that are not populist – according to the PopuList (Rooduijn et al. Citation2023) – and are defined as liberal in the ParlGov Database (Döring et al. Citation2022). The ‘centre-right’ group comprises non-populist parties that are defined as right-wing, Conservative, or Christian Democrats in the ParlGov Database. The ‘centre-left’ group comprises non-populist parties that are defined as Social Democratic or Socialist in the ParlGov Database. See Appendix IV for further details on party classification.

9 In other words, the difference in PRR attitudes between PRR voters and other voters appears to be significant, both statistically and substantively (RQ2a). Conversely, the divide in liberal-democratic attitudes between liberal-democratic voters and other voters is neither statistically nor substantively significant (RQ2b). Finally, although there is a statistically significant difference in social-democratic attitudes between social-democratic voters and others, the coefficient’s magnitude is too low for this to be regarded as a meaningful difference (RQ2c).

10 Furthermore, we have dealt with the ‘European mainstream’ in this article, without analysing cross-country differences in depth (also due to data availability). However, by referring to a ‘European mainstream’ we do not wish to imply that what is ‘mainstream’ at the aggregate European level is necessarily consistently ‘mainstream’ across all and any European states. On the contrary, ‘national’ mainstreams can potentially diverge from the ‘European’ mainstream. Therefore, future studies may also resort to our conceptualisation to explore variations between countries.

References

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove (2014). ‘How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:9, 1324–53.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn, eds. (2016a). Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? London: Routledge.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (2016b). ‘Inclusion and Mainstreaming? Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in the New Millennium’, in Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? London: Routledge, 1–28.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (2016c). ‘Into the Mainstream? A Comparative Analysis of the Programmatic Profiles of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe over Time’, in Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? London: Routledge, 31–52.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell (2015). Populists in Power. London: Routledge.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Davide Vampa, eds. (2021). Populism and New Patterns of Political Competition in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

- Brown, Katy, Aurelien Mondon, and Aaron Winter (2023). ‘The Far Right, the Mainstream and Mainstreaming: Towards a Heuristic Framework’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 28:2, 162–79.

- Crulli, Mirko, and Lorenzo Viviani (2022). ‘Turning to the Right? The Impact of the “Long Crisis Decade” (2008-2019) on Right-Wing Populist Vote and Attitudes in Europe’, Partecipazione e Conflitto, 15:2, 482–99.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Sara B. Hobolt (2012). ‘When Dimensions Collide: The Electoral Success of Issue Entrepreneurs’, European Union Politics, 13:2, 246–68.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Sara B. Hobolt (2020). ‘Challenger Parties and Populism’, LSE Public Policy Review, 1:1, 1–8.

- Donovan, Todd (2019). ‘Authoritarian Attitudes and Support for Radical Right Populists’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 29:4, 448–64.

- Döring, Holger, Constantin Huber, and Philip Manow (2022). ‘Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Established Democracies’, Development version. https://www.parlgov.org/about/

- Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fieldhouse, Edward, Jane Green, Geoffrey Evans, Jonathan Mellon, and Prosser Christopher (2020). ‘British Election Study Internet Panel Wave 17’. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8202-2

- Hawkins, Kirk A., Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, and Ioannis Andreadis (2020). ‘The Activation of Populist Attitudes’, Government and Opposition, 55:2, 283–307.

- Hawkins, Kirk A., Scott Riding, and Cas Mudde (2012). Measuring Populist Attitudes. Political concepts working paper series: Committee on Concepts and Methods, 1–35.

- Heinisch, Reinhard (2003). ‘Success in Opposition – Failure in Government: Explaining the Performamce of Right-Wing Populist Parties in Public Office’, West European Politics, 26:3, 91–130.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and James Tilley (2016). ‘Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis’, West European Politics, 39:5, 971–91.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2019). European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Guillem Vidal (2018). ‘Old versus New Politics: The Political Spaces in Southern Europe in Times of Crises’, Party Politics, 24:1, 10–22.

- Kallis, Aristotle (2015). ‘When Fascism Became Mainstream: The Challenge of Extremism in Times of Crisis’, Fascism, 4:1, 1–24.

- Kirchheimer, Otto (1966). ‘The Transformation of the Western European Party Systems’, in J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds.) Political Parties and Political Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 177–200.

- Marcos-Marne, Hugo, Homero Gil de Zúñiga, and Porismita Borah (2022). ‘What Do We (Not) Know about Demand-Side Populism? A Systematic Literature Review on Populist Attitudes’, European Political Science, 22:3, 293–307.

- Meguid, Bonnie (2005). ‘Competition between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success’, American Political Science Review, 99:3, 347–59.

- Meguid, Bonnie (2008). Party Competition between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meny, Yves, and Yves Surel (2002). ‘The Constitutive Ambiguity of Populism’, in Y. Meny and Y. Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–21.

- Moffitt, Benjamin (2022). ‘How Do Mainstream Parties “Become” Mainstream, and Pariah Parties “Become” Pariahs? Conceptualizing the Processes of Mainstreaming and Pariahing in the Labelling of Political Parties’, Government and Opposition, 57:3, 385–403.

- Mondon, Aurelien, and Aaron Winter (2020). Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso.

- Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541–63.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas (2019). The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity.

- Pop-Eleches, Grigore (2010). ‘Throwing out the Bums: Protest Voting and Unorthodox Parties after Communism’, World Politics, 62:2, 221–60.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs (2014). ‘Vox Populismus: A Populist Radical Right Attitude among the Public?’, Nations and Nationalism, 20:1, 80–92.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs (2016). ‘Closing the Gap? A Comparison of Voters for Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties and Mainstream Parties over Time’, in Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? London: Routledge, 53–69.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Andrea L. P. Pirro, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Caterina Froio, Stijn Van Kessel, Sarah L. De Lange, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2023). ‘The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC)’, British Journal of Political Science, 1–10.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, and Paul Taggart (2022). ‘The Populist Radical Right and the Pandemic’, Government and Opposition, 1–21.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, and Steven M. Van Hauwaert (2020). ‘The Populist Citizen: Empirical Evidence from Europe and Latin America’, European Political Science Review, 12:1, 1–18.

- Schulz, Anne, Philipp Müller, Christian Schemer, Dominique Stefanie Wirz, Martin Wettstein, and Werner Wirth (2018). ‘Measuring Populist Attitudes on Three Dimensions’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30:2, 316–26.

- Taggart, Paul (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Vampa, Davide, and Daniele Albertazzi (2021). ‘Conclusion’, in Daniele Albertazzi and Davide Vampa (eds.), Populism and New Patterns of Political Competition in Western Europe. London: Routledge, 269–88.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn van Kessel (2018). ‘Beyond Protest and Discontent. A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:1, 68–92.

- Vezzoni, Cristiano, et al. (2023). ‘Itanes 2022 – Italian National Election Study 2022 (Release 01, July 2023)’,

- Vittori, Davide, and Leonardo Morlino (2021). ‘Populism and Democracy in Europe’, in Daniele Albertazzi and Davide Vampa (eds.), Populism and New Patterns of Political Competition in Western Europe. London: Routledge, 19–49.

- Zulianello, Mattia (2020). ‘Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries’, Government and Opposition, 55:2, 327–47.