ABSTRACT

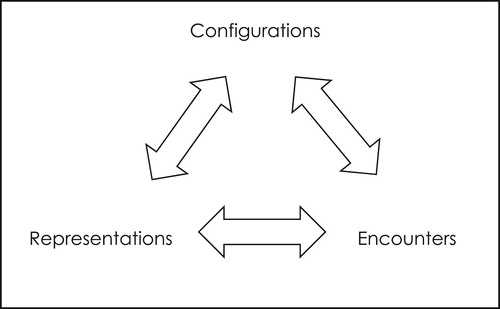

Rapidly diversifying societies, rising inequalities and the increasing significance of social differences are concurrent processes calling for a reexamination and reworking of certain conceptual and theoretical tools within the social sciences. Here, bringing together a range of theories and findings from various disciplines, a conceptual model is offered to facilitate analyses of such intertwined social processes. The model highlights mutually conditioning relationships between the fundamental conceptual domains of: social structures (here described as configurations), social categories (or representations) and social interactions (or encounters). The connections between these domains produce and reproduce, differentially in distinct times, scales and contexts, what can be called “the social organization of difference”.

Now is a vital time to study diversity and social change. Multiple kinds of diversification are deeply transforming societies, economies and polities (see for instance Bean Citation2018; Frey Citation2018; Tach et al. Citation2019). Indeed by this point in the twenty-first century, “The world is much more diverse on multiple dimensions and at many levels, typified by the salience of differences and their dynamic intersections” (Jones and Dovidio Citation2018, 45). At the same time – especially since the financial crisis of 2008, the Covid19 pandemic, growing White nationalism and the Black Lives Matter movement – there is more academic and public attention to the implications of difference in terms of social stratification, discrepant institutional experiences, and unequal political, health and economic outcomes.

This article is an exercise in reviewing and regrouping, from across the social sciences, a large number of insights on difference and social change. Rather than proposing any kind of new, unified theory, its aim is modestly to provide a condensed model and terminology to integrate more easily a breadth of literature concerning pertinent approaches, concepts and findings. The literature in question concerns three fundamental fields of social scientific theory or abstraction. These are: group categorizations, social interactions, and social stratification. The combined, mutually conditioning dynamics of these three abstract domains produce what I call “the social organization of difference”. Greater attention to the three-way working of these, I argue, will lead to better understanding of how social changes related to difference take place and generate various outcomes.

Prior to introducing a model of the social organization of difference, I must highlight the ideas of certain prominent scholars who have made substantial contributions toward these three fields and shaped my understanding of the inherent relationships between them. There are of course many, but in particular are: Fredrik Barth (Citation1969, Citation1972), Charles Tilly (Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2005), Douglas Massey (Citation2007; Massey and Brodman Citation2014), Michèle Lamont (Citation2014; Lamont and Molnár Citation2002; Lamont, Beljean, and Clair Citation2014), Andreas Wimmer (Citation2008, Citation2013) and Rogers Brubaker (Citation2004, Citation2015, Citation2016b). Some of the often overlapping lessons that I take from their works include these:

There are endemic, mutual connections – actually, processes of co-production – between the domains of human meanings, social interaction and social structure;

Social interactions, themselves structured by status and material inequalities, continuously shape social categories; shifting category meanings, in turn, can influence the nature and modes of social interaction and affect various aspects of social structure;

These mutually conditioning, cross-domain connections are situated both within and across micro-, meso – and macro-levels;

Meanings or categories are not just within individual minds, but are public; although public meanings are unevenly distributed in a population, they nevertheless both shape and are shaped by social interactions, status positions and hierarchies;

Social actions can be predicated on categories in ways that are conscious and deliberate, non-conscious and automatic, or in somewhat in-between way through sets of dispositions;

There are both general and discrete processes pertaining to different kinds of difference.

These lessons form the backdrop or starting point for considering the model outlined in this article. Specific insights from these scholars are cited throughout the piece.

The social organization of difference: a heuristic model

Especially in our current period characterized by heightened dynamics of diversification, a core task of social science should be to join disciplinary forces in order to arrive at better understandings of the ways that multiple aspects of difference relate to social relations and processes of social and economic stratification. “Diversity” is not a very satisfactory concept for framing this task within social science. It is a largely unwieldy concept for research and theory due to its ambiguity, normativity and polysemy (Vertovec Citation2012, Citation2015).

Instead we should try to comprehend “the social organization of difference” (Vertovec Citation2009, Citation2015, Citation2019). Intentionally echoing Barth’s (Citation1969) concern with the “social organization of culture difference”, the notion at once suggests a system. Moreover, it represents a tripartite scheme capturing the relationship between the three conceptual domains in question. That is, we have “social” (concerning interpersonal interactions and behaviours), “organization” (relating to patterns, forms, institutions and structures of society) and “difference” (referring to socially constructed categories).

The model offered here is not specific to race and ethnicity, but is applicable to numerous modes of difference: race, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexuality, age, disability, legal status and citizenship (see Vertovec Citation2015). Within the model, each category of difference can be examined in terms of its own meanings, constraints and processes, thereby avoiding a tendency to treat all differences as the same in effect. This is in keeping with the fact that every criterion or marker of difference (and their intersections) has a unique history of discrimination, with differential self- and other-ascribed meanings and discrete social, economic and political outcomes (cf. Delgado and Stefancic Citation2017).

The “social organization of difference” model draws directly on J. Clyde Mitchell’s analytical strategy for situational analysis (see Mitchell Citation1987; Rogers and Vertovec Citation1995; Vertovec Citation2019). This entails a similar tripartite model of different domains or levels of abstraction of structural, categorical and interpersonal actions in reflexive relation to one another. The method sees an analytical juxtaposition of (1) a situation or set of social actions, (2) the structural setting in which the situation is constituted, and (3) the meanings that the social actors themselves attribute to their actions. “The general perspective,” wrote Mitchell (Citation1987:, 9) is that “the behaviour of social actors may be interpreted as the resultant of the actors' shared understandings of the situation in which they find themselves and the constraints imposed upon these actors by the wider social order in which they are enmeshed.”

The following model and its constituent domains configurations – representations – encounters is not intended for explicating mechanisms or causal explanations, but rather for interpreting how social structures, meanings and social actions work generatively to shape each other. The approach perhaps represents a form of what Tilly called “systematic constructivism” (Citation2008, 196), addressing how social construction – of categories, social relations, status systems – actually works by examining the dynamics of mutually conditioning systems.

In using the model, broadly following Mitchell’s approach, the task for the social researcher is firstly to isolate a phenomenon or case to be described within one of the three abstract domains, and secondly to account for the conditioning influences of the other two domains upon it. The key feature, and indeed point, of the model is a kind of thought exercise. The model highlights the approach that from whatever “entry point” (by way of a phenomenon or case to be interpreted in any domain – such as an image in the domain of “representations”, an organizational arrangement as a “configuration”, or a specific interaction as “encounter”), a full analysis of the phenomenon or case – its content, development and implications – should entail a look at how it has been shaped by, and itself impacts, the two other domains.

Before engaging with the question how phenomena across these domains are linked, let us briefly look at what can be said to comprise each of the three domains themselves.

Configurations

By configurations, I refer to a variety of phenomena embodying stratified social structures (cf. Grusky Citation2014). The configurations concept is centered on the idea of social structure as an array of social positions (cf. Porpora Citation1989). It is based on the understanding that stratification has multiple facets, comprising an interplay of economic, cultural, social, power-based, honorific, civil and physical phenomena (Grusky and Weisshaar Citation2014). Class has conventionally been a significant notion for describing stratified social positions that includes many of these elements, especially economic ones. I suggest “configurations” rather than simply class-centred hierarchies or stratified social structures in order to convey a patterned assemblage or formation of social positions of both vertical and horizontal inequalities (cf. Stewart Citation2008). Configurations entail historically produced arrangements of social hierarchy, differential power, cultural distinction, economic wealth, poverty and other material outcomes.

I consider the rubric of configuration as somewhat analogous to that of “matrix of domination,” put forward by Patricia Collins (Citation2000).

A matrix of domination sees social structure as having multiple, interlocking levels of domination that stem from the societal configuration of race, class, and gender relations. This structural pattern affects individual consciousness, group interaction, and group access to institutional power and privileges. (Andersen and Collins Citation2018, 400).

Configurations are comprised of social positions, yet they are both expressed in and shaped by formations such as political structures and institutions, laws and criminal justice systems, legal statuses and legal frameworks, corporations and businesses, public organizational structures including health systems, schools and civil institutions. Configurations are most manifest in indicators such as wealth and income distribution, the allocation of jobs, health profiles and life expectancy, incarceration rates and various sites and modes of power relations. Despite undeniable progress, there is considerable evidence for the persistence if not exacerbation of difference-based disparities in these kinds of indicators (Manduca Citation2018). Configurations, as systems or structures of stratified social positions, also fundamentally manifest as space, particularly through systems of segregation (see, among others, Massey, Rothwell, and Domina Citation2009). This relates to what Lamont, Beljean, and Clair (Citation2014) consider to be “place-based inequality”, and what Brubaker (Citation2015:, 34) describes as “social separation,” that is “concentration in residential, occupational, institutional, social-relational, marital, consumption, media, and recreational space.”

Representations

Categorization and classification are of particular interest in Social Psychology. In this discipline, categorization is regarded as an intrinsic ability of the human mind that allows it to simplify a complex world or render it intelligible (Augoustinos Citation2001). Some key questions that have shaped research into social categorization include: what is a category’s nature and attributes, how is it bounded, how is it related to other categories or how is it ranked, and importantly, how are social categories produced, reproduced and changed?

One prominent set of responses to these questions is to be found in social representations theory (albeit a fragmented and diffuse body of literature; cf. Howarth Citation2006). Initiated by Serge Moscovici (Citation1984), this body of theory was inspired by Durkheim’s notion of collective representations. Unlike the Durkeimian idea which posits a broad and consistent set of meanings maintained over time across a population, Moscovici emphasized ongoing processes of dynamic and interactive co-construction of representations (hence the “social” qualifier). Social representations can be seen as systems of everyday meaning that allow people to know and interpret their social world, from situation to situation. Social representations research and theory focuses on “meaning-making processes” among and between people (Sammut et al. Citation2015, 5–6). Through such micro-level processes, social structures are created and reproduced.

Social categories or representations tend to be “groupist” in nature (Brubaker Citation2004). This means that people often tend to regard identities as based on groups that: have clear borders, are homogeneous in values and practices, act as one, and pit themselves against other, similarly conceived groups. Nevertheless, many representations of groups are not evenly distributed or shared, but evolve and circulate in specific milieus, and they are often contingent, temporary or fluctuating. In this way, it is crucial to recognize the plurality and positionality of representations in the public sphere. This realization also significantly informs theoretical work not just on how representations are dispersed, but also on how social representations change, how and to whom they are communicated, objectified, diffused, projected through images and propositions, made intelligible vis-à-vis other existing concepts and classifications, legitimized and reified.

Representations are often intersectional. Caroline Howarth (Citation2002) provides an apt illustration through an analysis of pervasive representations of race, place, and gender as well as their social effects in Brixton, London. These kinds of representations are also invested with moral meanings as well. Examples here are widespread notions of “soccer moms” (conveying notions associated with white, middle class, virtuous women) and “welfare queens” (conveying notions associated with black, poor, deceitful women) (Winter Citation2008, 160).

The notion of representations here also underscores the role of depictions – frames, schemas, images and discourses about categories, particularly in the public space and everyday life. Representations are the stuff not only of social interactions, but of public communication. In this way – again, going beyond some of the work to date on social categorization, the notion of representations takes into strong consideration the place of mass media and their effects.

The news media, for one, “play an influential role in shaping what and how people think about an issue” (Haynes, Merolla, and Karthik Ramakrishnan Citation2016, 19, emphasis in original). This is particularly evident in the increasing amount of research on the media framing of immigrants and immigration (such as Helbling Citation2014, Thorbjørnsrud Citation2015, Caviedes Citation2015). “From the perspective of scholars of migrants and minorities,” Erik Bleich, Irene Bloomraad and Els de Graauw (Citation2015: 862) suggest, “the relevance of framing and representation is clear: it is vital to understand how different groups are portrayed and the extent to which media representations affect public opinion, political mobilization and policy outcomes.” It is extremely common practice, across mass media and within political rhetoric, to represent immigrants as alien threats to the nation (Vertovec Citation2011). Migrant representations are regularly framed by notions of invasion, criminality, or economic threat (Bleich, Bloemraad, and Graauw Citation2015) or of system abuse through frames such as “anchor babies” and “chain migration” (Alamillo, Haynes, and Madrid Citation2019).

Increasingly we are witnessing how selective representations, via framing and strong imagery, are keys to understanding the power of social media, too. This is especially interesting to consider given – and because of – the brevity of format in many applications. In social media, categorical framings are especially brusque. It is also hugely important to study due to the sheer scale of the phenomenon. For example, no less than 68% of American adults use Facebook, the great majority of them daily (Pew Research Center Citation2018). “When people use Facebook to see exactly what they want to see,” Cass Sunstein (Citation2017, 2) says, “their understanding of the world will be greatly affected” (Ibid.: 2). Of course this includes – perhaps foremost – representations of social groups.

The dynamics and effects of public representations of difference are not monolithic, but vary across social groups. Moreover, mass media or social media audiences are “not just passive vessels ready to be filled with biased frames and subframes” (Ortega and Feagin Citation2017, 20). People are often quite aware of competing frames in the public sphere, knowing which politicians, movements or parts of the political spectrum are associated with which frames, thereby being able to follow or resist them (Haynes, Merolla, and Karthik Ramakrishnan Citation2016, 177). Indeed, as observed by Brubaker (Citation2004:, 68–9),

A common thread in studies of everyday classification is the recognition that ordinary actors usually have considerable room for maneuver in the ways in which they use even highly institutionalized and powerfully sanctioned categories. They are often able to deploy such categories strategically, bending them to their own purposes; or they may adhere nominally to official classificatory schemes while infusing official categories with alternative, unofficial meanings.

Further, public representations of difference are not fixed. The case of Muslims in the United Kingdom show this. Prior to Rushdie Affair at the end of the 1980s, British Muslims were often represented in the public sphere as a rather uncontentious sub-population, just one of several in multicultural Britain. Since the Rushdie Affair and alongside the rise of international Islamicist terrorism with which British Muslims have been increasingly impugned, representations of “Muslim” in the UK have been transformed into an ever-more stigmatized category, with direct effects on interactions and status (Poole Citation2002). Representations of Asians in America have travelled in the other direction, as it were, from “yellow peril” to “model minority” in the space of about a hundred years (Hsu Citation2015). Following the Covid19 pandemic, Asians in America and many other countries have been, once again, portrayed by many as a threat – this time, to public health.

Categorization is natural, social psychologists tell us, but group categories and their contents are social. Received and co-constructed representations of categories filter the social world and our activities in it. And they are directly related to processes surrounding inequality. As Tilly (Citation2005:, 111) put it, “Categories matters. To the extent that routine social life endows them with readily available names, markers, intergroup practices, and internal connections, categories facilitate unequal treatment by both members and outsiders.”

We are surrounded by and immersed by categories and their representations through public communication. They are a large part of our daily information processing and are fundamental to the social organization of difference.

These socially, culturally, and historically constituted ideas and beliefs, or cultural models, get inscribed in institutions and practices (e.g. language, law, organizational policies), and daily experiences (e.g. reading the newspaper, watching television, taking a test) such that they organize and coordinate individual understanding and psychological processes (e.g. categorization, attitudes, anxiety, motivation) and behavior (e.g. voting, interpersonal discrimination, disengagement) … (Plaut Citation2010, 82)

Encounters

Representations and unequal social structures are formed, manifested and remade through interactions across social categories and boundaries of difference. Such interactions are increasingly the subject of a cross-disciplinary literature on “encounters”.

In a review of recent geographical works, Helen Wilson (Citation2017:, 451) contends that ““encounter” is a conceptually charged construct that is worthy of sustained and critical attention.” Rather than a mere synonym for meeting, she describes encounters as a specific “genre of contact”, often considered to describe interactions that are by chance, casual or fleeting. Such brief interactions are considered to be emblematic of public spaces such as markets, transport links, shops and cafés. In any context, “encounters are fundamentally about difference and are thus central to understanding the embodied nature of social distinctions and the contingency of identity and belonging” (Ibid.: 452). Much work around encounters, Wilson notes, assumes a lack of commonality, an “us versus them”. Most often this is about inter-ethnic encounters, but also sometimes about crossing class, legal status, religion and sexuality. Encounter is a notion most employed in instances in which there are “clear distinctions of social identity and categorization, with an attention to how difference is negotiated, constructed and legitimated within contingent moments of encounter” (Ibid.: 454). Beyond these common uses of the notion, Wilson stresses that “Encounters make difference” (Ibid.: 455, emphasis in original). Interactions – as encounters across difference – may constitute, construct and reproduce representations of difference.

Wilson’s overview is paralleled by a review of anthropological ethnographies of encounter by Faier and Rofel (Citation2014). They, too, distill a general definition of encounters as engagements across difference. In this literature, there is often concern about “how culture making occurs through everyday encounters among members of two or more groups with different cultural backgrounds and unequally positioned stakes in their relationships” (Ibid.: 364). What is shown to arise from encounters across difference are “new cultural meanings and worlds” (Ibid.: 365). This is not always the result, however: among significantly differently situated groups, encounters may also reproduce or reify boundaries and identities (cf. Baumann Citation1996; Lamont and Molnár Citation2002; Wimmer Citation2013).

Here we can immediately see the relevance of what I am calling representations, or how the actors within an encounter categorize and narrate each other (especially by way of publically communicated categories involving boundaries, attributes and statuses). Tilly, too, observed this process and stated that, “When previously unconnected clusters of persons encounter each other, members of each cluster react to the encounter by creating names, practices, and understandings that mark the points of contact between them” (Citation2005, 112, emphasis in original). Furthermore, encounters do not take place in a vacuum, but within historically produced configurations of power and status. Hence, Matejskova and Leitner (Citation2011, 721) state that “Real-life contact between members of different social groups is always structurally mediated and embedded in particular historical and geographical contexts of power relations between and within social groups.”

Just as Wilson (Citation2017:, 455) puts forward that encounters “make difference”, she also asserts that encounters should be seen as “meetings that also make (a) difference” (Ibid.). That is, encounters can change representations or even status and structural positions. “[W]hilst fleeting encounters have been dismissed as having little meaning or little ability to transform values and belief,” Wilson (Ibid.: 463) writes, “it is possible that encounters accumulate, to gradually shift relations and behaviour over time – to both positive and negative effect.” One of the mechanisms by which this is accomplished is “to produce moments of cultural destabilization that allow participants to establish new intercultural understandings” (Valentine and Sadgrove Citation2014, 1980).

This approach to encounters across difference – as leading to shifts in perception, representation and attitudes – relates directly to the long-established and well-researched area of contact theory. Stemming from the work of Gordon Allport (Citation1954), contact theory posits that personal contact with out-group members can reduce prejudice. It is important to note that the theory posits certain conditions, including equivalent status of groups within the situation, common goals, cooperation/lack of competition and support of wider authorities. Allport also acknowledged the continued role of inequality in preventing positive outcomes of contact. Miles Hewstone (Citation1996) adds that for contact to work positively, group affiliation must be clear and salient. Persons with whom contact takes place must also be considered as representative of an out-group. Considerable evidence within social psychology clearly demonstrates that, given such suitable conditions, contact indeed “works” (see especially Pettigrew and Tropp’s Citation2006 meta-analysis of 515 contact studies).

Gill Valentine (Citation2008) suggests that perhaps many positive encounters may be merely enactments of codes of everyday urban etiquette or civility. This “ephemeral civility of the minor Goffmanian interaction rituals, casual conversations, shared greetings, little jokes, bits of gossip, small talk about the weather or how long a wait it is for a bus” (Collins Citation2000, 250) may mean very little in terms of changing attitudes, behaviours, everyday representations and micro-status positions. Or, as Wilson suggests above, they might actually accumulate to influence or change modes of interactions and the representations that accompany them.

The answer as to whether or not encounters produce meaningful or long-term change in categorization is not straight forward. For a start, several studies within the geography of encounter literature place emphasis on the role of specific contact spaces themselves (e.g. Mayblin, Valentine, and Andersson Citation2016). The approach is grounded in Ash Amin’s (Citation2002:, 959) noted call for observing “micropublics of everyday social contact and encounter” such as music clubs, theatre groups, and communal gardens. In this way, Piekut and Valentine (Citation2017, 176) set out to measure and understand the effects of different kinds of encounter spaces, reasoning that, “because the nature of encounter is socially produced differently in different types of space, depending on whether the encounter setting is more public or private inter-ethnic contact in different spaces will have a different effect on attitudes towards minorities.”

While Wilson suggests that fleeting encounters across difference might accumulate to change attitudes and representations, Matejskova and Leitner (Citation2011) note how such attitudes toward individual immigrants often do not “scale-up” to transform group stereotypes. This resonates with Valentine’s (Citation2013:, 6) view that,

In the context of both personal and community insecurity it is possible to see why some people find it hard to have mutual regard for groups they perceive as an economic or cultural threat. … This means that prejudiced individuals can have a vested interest in remaining intolerant despite positive individual social encounters with communities/individuals different from themselves.

Further, we must recognize the possibility that there might occur neither clearly positive nor negative outcomes of encounters. Through a study of Polish migrants in Britain, Anna Gawlewicz (Citation2015:, 268) understands the ““meaningful-ness” of encounters more broadly, as a capacity to form, alter or complicate people’s feelings about difference.” By way of encounters and their effects, her informants reported neither positive nor negative attitudes, but “in-between” or “complicated” feelings. Also within this field, new work attempts to assess intentional or engineered encounters (meetings, clubs, festivals and such) meant to break down prejudices and increase respect for others (e.g. Paulsen Galal and Hvenegård-Lassen Citation2020), or to observe non-conscious and habitual encounters (e.g. Wilson Citation2011). With a wide variety of interesting sites, methods and outcomes, everyday encounters and their influence on representations of difference and systems of social stratification currently presents a rich, indeed boom field of research and theory.

How or under what conditions does mutual conditioning between the three domains take place? Below, I take a closer look at what key scholars have said about each of the axes of mutual conditioning depicted in . The available literature suggests no specific set of conditions or singular process of mutual conditioning, but rather a variety of processes, conditions and mechanism potentially at play.

Representations - configurations

Across various disciplines, there are a number of studies that I would place on the axis referring to the mutual influence of representations and configurations. Many years ago, Omi and Winant’s (Citation1986) racial formation theory advocated a kind of mutual influence of these domains, as they put forward the premise that race must be seen through the linkage of social structure and cultural representation. For them, the category of race itself is framed in terms of social structure. More recently, on broader terms, James Jones and his co-authors (Jones, Dovidio, and Vietze Citation2014, 12) describe how “Societies construct significance for any concept or thing by imbuing it with beliefs and assumptions and by applying actions and organizing structures to it.” Categories such as Black, White, Asian, they (Ibid.) suggest, “are socially meaningful when they result in differences in treatment and different social outcomes within a diverse society.” Plaut (Citation2010:, 84) similarly describes societal processes “perpetuating representations of and behaviour toward social groups and ultimately reproducing cultural and structural realities.”

As evident in the earlier-referred to works of, for instance, Tilly and Wimmer (and to a certain degree, Massey), sometimes structuring by way of representations occurs through conscious acts of discrimination, exclusion or various acts of “boundary work”. Yet we must also recognize, following Brubaker and Lamont (and again Massey), that taken-for-granted or non-conscious processes utilizing representations and effectively reproducing stratifications are also part of everyday social dynamics. It is often hard to determine the degree of conscious/deliberate and non-conscious/inadvertent structuring-by-representation. Lamont, Beljean, and Clair (Citation2014) describe what they call “cultural processes” connecting social structures and individual cognition. These entail mechanisms of identification (including racialization and stigmatization), which seem to be more non-conscious, and mechanisms of rationalization (including standardization and evaluation) which seem to be more conscious. Together, such cultural processes and mechanisms serve to bridge micro and macro levels (Massey Citation2014). Individuals categorize themselves and others, usually following broad contextual frames, subsequently serving to reconfigure social relations and social structures over time (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2014; also see below).

There is often a question as to which categories are most salient in particular places or times as well as to how people get arrayed – or array themselves – into those categories. This is evident in the research of Saperstein, Penner, and Light (Citation2013), who examine the consequences of consciously and unconsciously organizing our workplaces, families, neighborhoods, and governments around such categorical distinctions of difference. Similarly, Domina, Penner, and Penner (Citation2017, 311) describe how schools function as “social sorting machines, creating categories that serve as the foundation of later life inequalities.”

Elsewhere, Saperstein and Penner (Citation2014) examine the social positions individuals occupy, how they identify themselves with social positions and the implications social positions have on how they are seen by others. Their findings suggest that,

some portion of Americans who experience an increase in their social position are “whitened” as a result of this mobility, and similarly, some portion of those who experience a decrease in their social position are “darkened”. Perversely, this implies that in the contemporary United States, the more fluid race is at the individual level, the more entrenched racial inequality will be at the societal level, as changes in the classifications and identifications of individuals serve to reinforce the existing racial order. (Ibid.: 678).

Configurations - encounters

The mutual conditioning of social structure and direct social interactions concerns the basic stuff of Sociology, significantly including debates around structure, agency and structuration (notably Giddens Citation1984). Social positions, status and power condition social interactions, and social interactions produce or reproduce social positions, status and power. With reference to such a dynamic, Randall Collins (Citation2000, Citation2004) underlines to what he describes as situational stratification. In this approach, stratification is something negotiated during actual interactions, which themselves are articulations of power and status. Macro-conditions of power and status impinge upon small everyday acts and interactions. In turn, macro conditions only form through micro-actions. Correspondingly, Brubaker (Citation2015:, 25–6) suggests that, “It is in and through these everyday encounters that respect, recognition, and status are distributed in iterative and cumulatively consequential ways.” Dirksmeier and Helbrecht (Citation2015, 487), too, submit that, “Encounters between strangers become the foundation for social stratification in general and, hence, any encounter is a subliminal negotiation of dominance, of distinction, and an expression of Foucault’s microphysics of power.”

For similar reasons, Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt (Citation2014) stress that researchers should examine the relatively durable kinds of relationships that are situated in local fields of action or socially organized spaces such as workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods. They see this as a crucial task of “specifying the social context in which the social relations that engender meaning-making develop” (Ibid.: 622).

Such dynamics are perhaps best portrayed ethnographically. For instance, in a study of small town Minnesota, Helga Leitner (Citation2012:, 830) shows how residents “draw on a broad scale and longer term conceptions of nation, community, and place to racialize immigrants of color as out of place and to set conditions of belonging to the local and national community.” In this way, macro-structures and their associated positionalities serve to shape encounters and relations with newcomers. However, the encounters do not always reproduce social structures. Rather, Leitner shows how encounters with difference are also able to disrupt preconceived categories, boundaries and structures. She (Ibid.: 833) writes, that “positionalities and encounters are co-constitutive. Encounters frequently reflect and reproduce the positionalities of those involved but also hold open the possibility of positionalities being called into question through the encounter.”

Encounters - representations

Again, a fundamental theme across the social sciences concerns the ways that social categories are constructed, formulated, shaped, blurred, sharpened and reproduced through social interactions (especially across modes of difference such as race, ethnicity, gender). Conversely – as engaged by key theoretical works on social and symbolic boundaries – social scientists have been equally concerned with the ways that social categories themselves differentially shape, constrain, and enable social interactions. In this way, as Massey (Citation2007:, 242) describes, neither categories nor social relations remain fixed:

The definition of categorical boundaries and the content of conceptual categories are not, however, automatic. They are learned through instruction and modified by experience. As social beings, people constantly test, extend, and refine the social schemas they carry in their heads, typically though interactions and discussions with other people.

Domain lag

Conditions of change in any single domain may, through variable processes, trigger and shape changes in one or both of the other domains. Yet while the three domains of the configurations-representations- encounters model are mutually conditioning, reasons for change are highly contingent and, especially, paces of change are not predictable.

The co-evolution of phenomena within the three domains is not necessarily an even process: changes in one domain might develop long before transformations are felt in either of the other domains. For instance, policy changes regularly take a considerable period to modify social relations, and shifting social relations might not be reflected in public or political discourse for some time. In such cases, we might consider the nature and implications of what can be called “domain lag”. (Vertovec Citation2015, 16)

For example with regard to the domain of configurations, Germany experienced a massive influx of over one million asylum-seekers in 2015–16 (Bock and Macdonald Citation2019): this exogenous or externally originating process entailed a rapid and largescale shift in social and political structures. New modes of encounter subsequently ensued across German society, from migrants’ engagements with state bureaucracies through exchanges between migrants and volunteer groups to everyday interactions involving the recent migrants in towns and urban neighborhoods. New public representations of the newcomers in Germany, however, have taken much longer to emerge. This is because the influx included migrants of many kinds that were not familiar in the German context, such that standard or longstanding categories, frames and schemas were not fit for purpose (cf. Vollmer and Karakayali Citation2018). As examples in the domain of representations, we have seen endogenous patterns of change surrounding the adoption of new language to talk of disabled persons (Thomas Citation2015), progress in the ways LGBTQ persons and relationships are represented on television (Albertson Citation2018), and attempts at fostering new modes of signification through the strategic adoption of nomenclature such as “African American” (Philogène Citation2001) and “People of Color” (Pérez Citation2020). It remains to be demonstrated whether such changes of representation have led to changing social encounters or shifting status configurations. And in the domain of encounters, as exemplified in neighborhoods of London, we can observe the emergence of commonplace patterns of everyday interaction across difference remain unremarked upon (as changes to representations) or that do not appear yet to impact patterns of social stratification (as changes to configurations) (Wessendorf Citation2014).

Developments in any single domain needn't immediately “cause” change in another domain. Cross-domain effects may be incremental over time (as in each example above, in which a substantial change in a domain only gradually, or some time later, shifts phenomena or patterns in another domain). In so many sociological studies and theories addressing links between categorization, social interactions and social structuring, the temporal dimension remains largely under-examined. It is hoped that the social organization of difference model offered here might provide a useful framework for elaborating and elucidating such temporal links.

Conclusion

There exists a considerable body of scholarly work concerning aspects of social stratification, categorization and social interaction – or in my terms, configurations, representations and encounters. It is not only the inherent nature of the processes within these topic areas or abstract domains (each a substantial field in its own right) that matters for understanding difference and social structure, but appreciating the linkage of these domains. Such linkage creates, shapes, reproduces or shifts the social organization of difference – including its distribution of inequality – in any society, within and across macro-, meso- and micro- scales (cf. Saperstein, Penner, and Light Citation2013).

Many key authors highlighted in this article have pursued the linkage of these domains in various ways themselves. Massey (Citation2007:, 16) has stated that,

No matter what their position in the system, people seek to define for themselves the content and meaning of social categories, embracing some elements ascribed to them by the dominant society and rejecting others, simultaneously accepting and resisting the constraints and opportunities associated with their particular social status. Through daily interactions with individuals and institutions, people construct an understanding of the lines between specific social groups …

conceptualize cultural processes as ongoing classifying representations/practices that unfold in the context of structures (organizations, institutions) to produce various types of outcomes. These processes shape everyday interactions and result in an array of consequences that may feed into the distribution of resources and recognition.

From above, we can focus on the ways in which categories are proposed, propagated, embedded in multifarious forms of “governmentality”. From below, we can study the “micropolitics” of categories, the ways in which the categorized appropriate, internalize, subvert, evade or transform the categories that are imposed on them …

The social organization of difference model can importantly be used comparatively, too. A close examination of specific processes and factors within and mutually influencing the three domains can shed light on specifics in the social organization of difference between countries such as the USA, Brazil and South Africa; within a country between cities like Houston, Los Angeles and Miami; or within a single city, for instance between neighborhoods such as Englewood, Lincoln Park and Little Village in Chicago. Each context or scale – nation, city or neighborhood – will have its own historically produced social organization of difference, its own set of configurations, representations and encounters. In this way, the model can be comparatively utilized brings to elucidate the kinds of conditions that make contexts similar to, or different from, each other.

Further fruitful areas for developing the model might entail the burgeoning field of emotion and affect studies and how it relates to the links between social categorizations, interactions and modes of stratification (see, among others, Bonilla-Silva Citation2019). Another might be to look at how processes or phenomena of categorical fusion – highlighted by work on themes such as mixed race identities (e.g. Aspinall and Song Citation2013), multiple categorical distinctions (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2014) and intersectional complexity (McCall Citation2005), transnationalism (e.g. Bauböck and Faist Citation2014) and creolization (e.g. Cohen and Sheringham Citation2016) – serve to disrupt or destabilize the social organization of difference in any particular setting (see Brubaker Citation2016a). Indeed, as Brubaker points out in his illuminating book Trans, we are in an “age of unsettled identities” in which

challenges to established categories have been spectacular, as indicated by the stunningly rapid shift toward social and legal recognition of gay marriage, the mainstreaming of transgender options and identities, and the gathering challenges to the binary regime of sex itself. But racial and ethnic categories have also been profoundly unsettled: by demands for the recognition of multiracial identities, by the increasing fluidity and fragmentation of the ethnoracial landscape, and by the proliferation of crossover forms of racial identification. (Brubaker Citation2016b, 5)

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to many colleagues for providing valuable criticism and feedback at various stages during the development of this work. In particular, my thanks go to Douglas Massey, Rogers Brubaker, Andreas Wimmer, Karen Schoenwaelder, Phil Gorski, John Solomos, Jeremy Walton, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Tilmann Heil, Fran Meissner, Boris Nieswand, Matthias Koenig, Ajay Gandhi, Susanne Wessendorf, Lucas Drouhot, Peter Scholten, Maria Schiller, Paul Spoonley and Robin Cohen. I am also obliged to students and colleagues for their engagement in seminars on the topic at the Max Planck Institute, Autonomous University Barcelona, University of Tübingen, University of Göttingen, Monash University as well as at Erasmus University Rotterdam, where I conducted much research under the auspices of a Visiting Professorship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alamillo, Rudy, Chris Haynes, and Raul Madrid. 2019. “Framing and Immigration Through the Trump era.” Sociology Compass 13 (5): 1–11.

- Alba, Richard D., Noura E. Insolera, and Scarlett Lindeman. 2016. “Is Race Really so Fluid? Revisiting Saperstein and Penner’s Empirical Claims.” American Journal of Sociology 122 (1): 247–262.

- Albertson, Cory. 2018. A Perfect Union? Television and the Winning of Same-Sex Marriage. London: Routledge.

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Amin, Ash. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A 34: 959–980.

- Amin, Ash. 2013. “Land of Strangers.” Identities 20 (1): 1–8.

- Andersen, Margaret L., and Patricia Hill Collins. 2018. “Why Race, Class, and Gender Matter.” In Inequality in the 21st Century, edited by D. B. Grusky, and J. Hill, 400–401. Boulder: Westview.

- Anderson, Elijah. 2011. The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Everyday Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Aspinall, Peter, and Miri Song. 2013. Mixed Race Identities. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Augoustinos, Martha. 2001. “Social Categorization: Towards Theoretical Integration.” In Representations of the Social: Bridging Theoretical Traditions, edited by K. Deux, and G. Philogène, 201–216. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Barth, Fredrik. 1969. “Introduction.” In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference, edited by F. Barth, 9–38. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Barth, Fredrik. 1972. “Analytical Dimensions in the Comparison of Social Organizations.” American Anthropologist 74 (1/2): 207–220.

- Bauböck, Rainer, and Thomas Faist, eds. 2014. Diaspora and Transnationalism: Concepts, Theories and Methods. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Baumann, Gerd. 1996. Contesting Culture: Discourses of Identity in Multi-Ethnic London. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bean, Frank D. 2018. “Growing U.S. Ethnoracial Diversity: A Positive or Negative Societal Dynamic?” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 677: 229–239.

- Bleich, Erik, Irene Bloemraad, and Els de Graauw. 2015. “Migrants, Minorities and the Media: Information, Representations and Participation in the Public Sphere.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 857–873.

- Bock, Jan-Jonathan, and Sharon Macdonald, eds. 2019. Refugees Welcome? Difference and Diversity in a Changing Germany. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2019. “Feeling Race: Theorizing the Racial Economy of Emotions.” American Sociological Review 84 (1): 1–25.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2004. Ethnicity Without Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2015. Grounds for Difference. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2016a. “The Dolezal Affair: Race, Gender, and the Micropolitics of Identity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (3): 414–448.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2016b. Trans: Gender and Race in an Age of Unsettled Identities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Caviedes, A. 2015. “An Emerging ‘European’ News Portrayal of Immigration?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 897–917.

- Cohen, Robin, and Olivia Sheringham. 2016. Encountering Difference: Diasporic Traces, Creolizing Spaces. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

- Collins, Randall. 2000. “Situational Stratification: A Micro-Macro Theory of Inequality.” Sociological Theory 18: 17–43.

- Collins, Randall. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. 2017. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. 3rd edn. New York: New York University Press.

- Dirksmeier, Peter, and Ilse Helbrecht. 2015. “Everyday Urban Encounters as Stratification Practices: Analysing Affects in Micro-Situations of Power Struggles.” City 19 (4): 486–498.

- Domina, Thurston, Andrew Penner, and Emily Penner. 2017. “Categorical Inequality: Schools as Sorting Machines.” Annual Review of Sociology 43: 311–330.

- Faier, Lieba, and Lisa Rofel. 2014. “Ethnographies of Encounter.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43: 363–377.

- Frey, William H. 2018. The Millennial Generation: A Demographic Bridge to America’s Diverse Future. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Gawlewicz, Anna. 2015. “Beyond Openness and Prejudice: The Consequences of Migrant Encounters with Difference.” Environment and Planning A 48: 256–272.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Grusky, David B., ed. 2014. Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective (4th edn.). Boulder: Westview.

- Grusky, David.B., and Katherine R. Weisshaar. 2014. “The Questions we ask About Inequality.” In Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective (4th edn.), edited by D. B. Grusky, 1–16. Boulder: Westview.

- Haynes, Chris, Jennifer L. Merolla, and S. Karthik Ramakrishnan. 2016. Framing Immigrants: News Coverage, Public Opinion, and Policy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Helbling, M. 2014. “Framing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (1): 21–41.

- Hewstone, Miles. 1996. “Contact and Categorization: Social Psychological Interventions to Change Intergroup Relations.” In Stereotypes and Stereotyping, edited by C. N. Macrae, C. Stangor, and M. Hewstone, 323–368. New York: Guildford Press.

- Howarth, Caroline. 2002. “So, You’re from Brixton?’: The Struggle for Recognition and Esteem in a Stigmatized Community.” Ethnicities 2 (2): 237–260.

- Howarth, Caroline. 2006. “A Social Representation is not a Quiet Thing: Exploring the Critical Potential of Social Representations Theory.” British Journal of Social Psychology 45: 65–86.

- Hsu, Madeline Y. 2015. The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jones, James M., and John F. Dovidio. 2018. “Change, Challenge, and Prospects for a Diversity Paradigm in Social Psychology.” Social Issues and Policy Review 12 (1): 7–56.

- Jones, James M., John F. Dovidio, and Deborah L. Vietze. 2014. The Psychology of Diversity: Beyond Prejudice and Racism. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Jost, John T., Mahzarin R. Banaji, and Brian A. Nosek. 2004. “A Decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated Evidence of Conscious and Unconscious Bolstering of the Status quo.” Political Psychology 25 (6): 881–919.

- Lamont, Michèle. 2014. “Reflections Inspired by Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks by Andreas Wimmer.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (5): 814–819.

- Lamont, Michèle, Stefan Beljean, and Matthew Clair. 2014. “What is Missing? Cultural Processes and Causal Pathways to Inequality.” Socio-Economic Review 12: 573–608.

- Lamont, Michèle, and Virág Molnár. 2002. “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167–195.

- Leitner, Helga. 2012. “Spaces of Encounters: Immigration, Race, Class, and the Politics of Belonging in Small-Town America.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (4): 828–846.

- Manduca, Robert. 2018. “Income Inequality and the Persistence of Racial Economic Disparities.” Sociological Science 5: 182–205.

- Marlowe, Jay. 2020. “Refugee Resettlement, Social Media and the Social Organization of Difference.” Global Networks 20 (2): 274–291.

- Martiniello, Marco. 2015. “Immigrants, Ethnicized Minorities and the Arts: A Relatively Neglected Research Area.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (8): 1229–1235.

- Massey, Douglas S. 2007. Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System. New York: Russell Sage.

- Massey, Douglas S. 2014. “Filling the Meso-Level gap in Stratification Theory.” Socio-Economic Review 12: 610–614.

- Massey, Douglas S., and Stefanie Brodman. 2014. Spheres of Influence: The Social Ecology of Racial and Class Inequality. New York: Russell Sage.

- Massey, Douglas S., Jonathan Rothwell, and Thurston Domina. 2009. “Changing Bases of Segregation in the United States.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 626: 74–90.

- Matejskova, Tatiana, and Helga Leitner. 2011. “Urban Encounters with Difference: The Contact Hypothesis and Immigrant Integration Projects in Eastern Berlin.” Social & Cultural Geography 12: 717–741.

- Mayblin, Lucy, Gill Valentine, and Johan Andersson. 2016. “In the Contact Zone: Engineering Meaningful Encounters Across Difference Through an Interfaith Project.” The Geographical Journal 182: 213–222.

- McCall, Leslie. 2005. “The Complexity of Intersectionality.” Signs 30 (3): 1771–1800.

- Mitchell, J. Clyde. 1987. Cities, Society and Social Perception: A Central African Perspective. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Moscovici, Serge. 1984. “The Phenomenon of Social Representations.” In Social Representations, edited by S. Farr, and S. Moscovici, 3–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1986. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge.

- Ortega, Frank J., and Joe R. Feagin. 2017. “Framing: The Undying White Racial Frame.” In The Routledge Companion to Media and Race, edited by C. P. Campbell, 19–30. New York: Routledge.

- Paulsen Galal, L., and K. Hvenegård-Lassen. 2020. Organised Cultural Encounters: Practices of Transformation. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783.

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Social Media Use in 2018. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/.

- Pérez, Efrén. 2020. “‘People of color’ are protesting. Here’s what you need to know about this new identity.” The Monkey Cage, Washington Post 2 July.

- Philogène, Gina. 2001. “From Race to Culture: The Emergence of African American.” In Representations of the Social: Bridging Theoretical Traditions, edited by K. Deaux, and G. Philogène, 113–128. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Piekut, Anna, and Gill Valentine. 2017. “Spaces of Encounter and Attitudes Towards Difference: A Comparative Study of two European Cities.” Social Science Research 62: 175–188.

- Plaut, Victoria C. 2010. “Diversity Science: How and why Difference Makes a Difference.” Psychological Inquiry 21: 77–99.

- Poole, Elizabeth. 2002. Reporting Islam: Media Representations of British Muslims. London: I.B. Taurus.

- Porpora, Douglas V. 1989. “Four Concepts of Social Structure.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 19 (2): 195–211.

- Rogers, Alisdair, and Steven Vertovec, eds. 1995. The Urban Context: Ethnicity, Social Networks and Situational Analysis. Oxford: Berg.

- Sammut, Gordon, Eeleni Androuli, George Gaskell, and Jaan Valsiner. 2015. “Social Representations: A Revolutionary Paradigm?” In The Cambridge Handbook of Social Representations, edited by G. Sammut, E. Androuli, G. Gaskell, and J. Valsiner, 3–11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saperstein, Aliya, and Andrew M. Penner. 2014. “Racial Fluidity and Inequality in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (3): 676–727.

- Saperstein, Aliya, Andrew M. Penner, and Ryan Light. 2013. “Racial Formation in Perspective: Connecting Individuals, Institutions, and Power Relations.” Annual Review of Sociology 39: 359–378.

- Stewart, Frances. 2008. Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group Violence in Multiethnic Societies. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Sunstein, Cass. 2017. #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Tach, Laura, Barrett Lee, Michael Martin, and Lauren Hannscott. 2019. “Fragmentation or Diversification? Ethnoracial Change and the Social and Economic Heterogeneity of Places.” Demography 56: 2193–2227.

- Thomas, Carol. 2015. “Disability and Diversity.” In Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies, edited by S. Vertovec, 43–51. London: Routledge.

- Thorbjørnsrud, K. 2015. “Framing Irregular Immigration in Western media.” American Behavioral Science 59 (7): 771–82.

- Tilly, Charles. 1998. Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tilly, Charles. 2001. “Anthropology Confronts Inequality.” Anthropological Theory 1 (3): 299–306.

- Tilly, Charles. 2005. Identities, Boundaries and Social Ties. Boulder: Paradigm.

- Tilly, Charles. 2008. Explaining Social Processes. Boulder: Paradigm.

- Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald, and Dustin Avent-Holt. 2014. “What is Still Missing? The Relational Context of Inequality.” Socio-Economic Review 12: 621–628.

- Valentine, Gill. 2008. “Living with Difference: Reflections on Geographies of Encounter.” Progress in Human Geography 32: 323–337.

- Valentine, Gill. 2013. “Living with Difference: Proximity and Encounter in Urban Life.” Geography (sheffield, England) 98 (1): 4–9.

- Valentine, Gill, and Joanna Sadgrove. 2014. “Biographical Narratives of Encounter: The Significance of Mobility and Emplacement in Shaping Attitudes Towards Difference.” Urban Studies 51 (9): 1979–1994.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2009. “Conceiving and researching diversity.” Göttingen: Max-Planck-Institute Working Paper 09-01.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2011. “The Cultural Politics of Nation and Migration.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 241–256.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2012. “‘Diversity’ and the Social Imaginary.” Archives Européennes de Sociologie/ European Journal of Sociology LIII (3): 287–312.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2015. “Introduction: Formulating Diversity Studies.” In Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies, edited by S. Vertovec, 1–20. London: Routledge.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2019. “Barth and the Social Organization of Difference.” In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries Today: A Legacy of Fifty Years, edited by T. H. Eriksen, and M. Jakoubek, 109–117. London: Routledge.

- Vollmer, Bastian, and Serhat Karakayali. 2018. “The Volatility of the Discourse on Refugees in Germany.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 118–139.

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2014. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Wilson, Helen F. 2011. “Passing Propinquities in the Multicultural City: The Everyday Encounters of bus Passengering.” Environment and Planning A 43: 634–649.

- Wilson, Helen F. 2017. “On Geography and Encounter: Bodies, Borders, and Difference.” Progress in Human Geography 41: 451–471.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113: 970–1022.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Winter, Nicholas J.G. 2008. Dangerous Frames: How Ideas About Race and Gender Shape Public Opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.