ABSTRACT

Education plays a fundamental role in the counteraction of racism. Although school leaders hold a central position in counteracting racism, little is known about their everyday efforts in this endeavor. Considering the persistent presence of racism, it is imperative to understand the efforts undertaken by these powerful actors. In this study, in-depth interviews with 14 Norwegian principals have shown patterns of avoidance and denial of racism. Using the concept of everyday racism, principals’ practices were analyzed as multilevel work. This study highlights the importance of awareness of the complexities of racism and the need for powerful actors to engage in the critical exploration of racism and antiracism, and it argues that by making racism a nonissue, principals play a key role in absolving their schools of the pedagogical responsibility to counteract racism. Meanwhile, it also places focus on the structures around principals that inhibit their opportunity to engage in antiracism.

Introduction

Schools are assigned a central role in working against racism for the benefit of both individual students and overall society (Lynch, Swartz, and Isaacs Citation2017), and school leaders typically bare a responsibility in implementing antiracist practices. The presence of racism in schools is well documented in many countries, as are its devastating consequences (Benner et al. Citation2018; Paradies et al. Citation2015). While the literature suggests different ways in which school leaders can use their influence to eradicate racism and other forms of oppression (Bogotch Citation2002; Khalifa, Gooden, and Davis Citation2016; Kumashiro Citation2000; Shields Citation2010), and many countries place juridical obligations to counter racism on their educational systems (OECD Citation2023), there is reason for concern that school leaders may not be doing enough. Studies have shown that racism is characterized by those in school leadership as a nonissue and a task that they have little interest in and assign a low priority (Aveling Citation2007; Gooden and Showunmi Citation2021; Miller Citation2020). Hence, this article focuses on the perspectives of school principals on (not) addressing racism, with the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of these perspectives and the reasoning behind the principals’ approaches.

This paper focuses on Norway as a national context in which school leadership and racism or antiracism have rarely been studied. Much of the existing knowledge stems from specific country contexts in the core Anglosphere, which have dominated the knowledge formation of school leadership and racism over the last few decades. While this has translated into indispensable knowledge for the general field, there remains a need for insights from other contexts to understand how racism, antiracism, and educational leadership operate in different contemporary sociohistorical and cultural contexts and to make visible what can be learned. As Moreno Figueroa and Wade (Citation2024) contextualized in their analysis of the Latin American context, racism and antiracism have global and local features, and as Wade (Citation2024) proposed, a productive approach might be to adopt a relational perspective that focuses on the connections and shared aspects between seemingly separate and defined regions or cases. Hence, this contribution adds to perspectives that seek to understand the contemporary conditions of racism and antiracism within specific localities by investigating how school leaders, as specific, influential actors, use their own positions to work against racism.

There is a need to engage in a deeper understanding of the conditions for antiracism within different sectors and positions to make opportunities and challenges visible as precisely as possible. Within educational systems, formal school leaders are not the sole agents of institutional functioning and improvement (Courtney et al. Citation2021), but they do play an important role in the success of antiracist efforts (Ben, Kelly, and Paradies Citation2020). According to Miller (Citation2020), school principals typically have some degree of opportunity and responsibility to set the direction of their schools’ culture, manage organizational and human development, and follow legal mandates. In addition, principals may serve as a crucial link between educational policy and its implementation as well as between schools and the wider community (Miller Citation2020). The same is true for Norwegian principals. They have a mandate to counteract racism, but they also enjoy a high degree of freedom as to how and when to engage in antiracist efforts (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2023). Studying principals’ perceptions is therefore crucial for gaining insight into how they approach racism.

This paper presents a study that draws on qualitative in-depth interviews with 14 principals in the Norwegian primary and lower secondary school system (students aged 6–16 years). The following research questions guide this work: (a) What efforts did the principals focus on when discussing racism? and (b) How did the principals legitimize their work related to racism? The study is an empirical contribution that aims to map and provide an understanding of the efforts of Norwegian school leaders regarding racism and antiracism with the purpose of providing insight into the perspectives of these key actors in educational approaches against racism. By providing an analysis of principals’ efforts in this way, I also hope to provide relevant input to the discussion on the contemporary conditions of antiracism (Lentin Citation2016; Moreno Figueroa and Wade Citation2024; Rejón Piña Citation2023; Seikkula Citation2022).

In what follows, I review the relevant international literature on school leadership and racism. I then outline the Norwegian educational landscape, discussing the national understanding of racism and school leaders’ roles in antiracist work. The theoretical framework explains how Essed’s (Citation1991) understanding of everyday racism is used in the analysis. Then, the design and methods are presented. The analysis section highlights school principals’ self-defined efforts, focusing on the efforts they mentioned that may not in fact address racism. Since the majority of the efforts that the principals focused on may be understood as the avoidance and denial of racism, these are the main focuses of the analysis. In the discussion section, possible understandings that place the principals’ efforts in the context of political economy are discussed. The paper concludes by discussing the implications of these findings for future research and educational practices.

Antiracism and school leadership: what we know

It has been found that structural, institutional, and cultural barriers to antiracism persist within educational leadership (Aveling Citation2007; Gooden and Showunmi Citation2021; Khalifa, Gooden, and Davis Citation2016; Miller Citation2020). Decades of research on the existence and consequences of racism in education have not brought antiracism onto the agenda of school leaders. A growing body of literature on educational leadership and racism/antiracism has found that school leaders tend to ignore racism by underplaying its existence, view it solely as a single act of individual character, or ascribe it to cultural differences, as issues concerning race and racism are ascribed to individual factors, are not seen as relevant, or are believed to be solved through multicultural practices within schools (Gorski Citation2019; Khalifa, Gooden, and Davis Citation2016; Pollock Citation2006; Wiltgren Citation2023). International reviews have consistently shown that ignoring racism may be harmful and counterproductive (Paradies et al. Citation2009; Pedersen et al. Citation2011) and that for work against racism to be successful, it must be theoretically founded and strategically implemented over time and in all parts of an educational structure (Bezrukova, Jehn, and Spell Citation2012; Paradies et al. Citation2009).

Different explanations for the persistence of racism have been suggested, ranging from interpersonal and intergroup factors to structural and systemic conditions. Factors that have been observed to prevent school leaders’ implementation of antiracist change include weak legislative frameworks on issues of racism (Ahmed Citation2007; Arneback and Quennerstedt Citation2016; Moeller Citation2021), poor monitoring of institutional practices by governments (Miller Citation2019), a lack of focus on racism in leadership training (Miller Citation2020; Tanner and Welton Citation2021), and poorly developed antiracist language and practices within the field of education (Brooks and Watson Citation2019; Røthing Citation2015; Nyegaard Citationin review). Attention has also been brought to hegemonic understandings of race and racism that undermine school leaders’ ability to address racism (Brooks and Watson Citation2019); to the dominance of Westernized Eurocentric school leaders who impose imperialist, colonial control over education (Khalifa et al. Citation2019); and to the impact of neoliberal policies in education that constrain and shape the work of educational leadership (Bjordal Citation2023). As Miller (Citation2020) pointed out, there is no “quick fix” when it comes to school leaders combating racism; rather, it requires time, effort, training, and the willingness to grapple with difficult issues.

The Norwegian context

Demographically, Norway has had an increasingly diverse population since the 1970s. Today, over 16 per cent of the population has an “immigrant background”, meaning that they are born abroad or have parents or grandparents born abroad (Statistics Norway Citation2023a). The increase in the immigrant population has mainly been due to the immigration of workers from Eastern Europe since the expansion of the EU in the 2000s and from Asia since the 1970s, conflict-driven migration (refugees and asylum seekers), and family reunions (Statistics Norway Citation2023a). The Norwegian population also includes the Indigenous Sami and five national minorities (Kvens/Norwegian Finns, Jews, Forest Finns, Roma, and Romani people). Because there is very limited public registration of ethnic/racial background in Norway, the size and internal demographics of these groups is not certain. Additionally, according to the Norwegian Directorate for Children, there is a significant research gap when it comes to the immigrant population and their descendants, the Sami population, and the national minorities within the educational system (Bufdir Citation2021). The diversity among the general population is presumably represented within the public school system, as public schools are attended by 88 per cent of the population (Statistics Norway Citation2023b).

Norwegian educational institutions have been and continue to be central arenas for the production and reproduction of racism. Historically, schools have been the main arenas for the forced assimilation of the Sami people and other national minorities, and although the assimilation policy of “Norwegianization” officially ended in the 1970s, these wrongdoings still bear consequences today (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Citation2023, 458). Currently, schools are the main arena in which young people encounter racism (Proba Citation2023). Minorities in Norway experience racism in schools in the form of exclusion, underestimation, racist hate speech, violence, and micro-aggressions, yet these violations are often unmentioned, downplayed, or misunderstood by school staff (Erdal and Strømsø Citation2021; Eriksen and Stein Citation2022; Jore Citation2018; Røthing Citation2015; Svendsen Citation2014).

Norwegian schools have a mandate to combat racism, but the recommendations for addressing racism may lack specificity. National legislation, including the ratified United Nations declarations and conventions (Human Rights Act Citation1999), emphasizes the promotion of universal values, such as democracy, equality, and equal rights and opportunities. The Education Act (Citation1998), which regulates the Norwegian school system, obliges schools to combat all forms of discrimination and mandates systematic efforts by schools to identify and prevent “violations of a positive psychosocial school environment” (The Education Act Citation1998, Section 9 A-1). Alongside the Education Act, the national curriculum governs primary and secondary education. The current curriculum, however, mentions “racism” only once, and its focus on universal ideals that are seldom concretized or actionable has been critiqued (Nyegaard Citationin review).

Within the legislation, school leaders’ responsibilities are emphasized. In Norway, principals are chosen on the basis of their pedagogical education and leadership skills, and they have typically worked as teachers before becoming part of educational management. According to Bjørnset and Kindt (Citation2019), a typical school leader is older, often female, and highly educated and usually has school leadership education. There is low turnover within the principal position. Demands and expectations encompass the students’ learning environment, the professional community and collaboration, management and administration, development and change, and the leadership role (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2023). According to the Directorate for Education and Training, which provides guidelines for principals, the responsibility of a leader is “in principle all encompassing. The principal must ensure that everything is taken care of, but there must be many who contribute to this” (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2023).

Historically, the principal position in Norwegian schools is that of the head teacher – meaning a teacher who has additional managerial and administrative tasks. Over the last three decades, educational leadership has been professionalized to an increasing degree, and at the same time, the school system has become gradually affected by neoliberal policies (Møller Citation2021). Neoliberal managerial reforms took a strong hold in the early 2000s as policy- and lawmakers in Norway became increasingly concerned with following the international trends in education of effectivization, maximization of school quality and improvement of test scores in basic skills (Møller Citation2021, 72). According to Bjordal (Citation2023), the marketisation of education through, for instance, performance management, increased emphasis on parental choice, coordinated comparison of test results, and per capita funding affect the work of school leaders by creating high levels of performance expectations – in turn, creating a structure characterized by institutionalized status hierarchies based on ethnicity, “white flight” from schools with a high percentage of “immigrant” students, and lesser educational conditions for students from nondominant groups.

One explanation for this discrepancy between educational institutions as producers and reproducers of racism and antiracist policies and efforts may be that racism has been considered somewhat peripheral in the Norwegian educational system (Eriksen and Stein Citation2022; Harlap and Riese Citation2021; Osler and Lindquist Citation2018). Racism has been understood as individual, in that it has been linked to ideological actions, beliefs, and attitudes on the far right, and historical, in that it is considered something that occurred long ago or far away (Midtbøen, Orupabo, and Røthing Citation2014). These tendencies may be seen in the wider context of how racism is understood in Norway. While equity and social justice have been conceived as the core of the social democracy that characterizes Norwegian society, Norway’s national identity has also been strongly associated with homogeny (Führer Citation2021; Gullestad Citation2002). Eriksen and Stein (Citation2022) described the Norwegian educational system as highly influenced by national exceptionalism, where an elevated self-image and intentions in educational policy portray education in Norway as a provider of equity and solidarity. Within this limiting self-image, the role of educational institutions in the continuous reproduction of colonial structures is ignored and racism, epistemic violence, and exploitive capitalist structures are naturalized (Eriksen and Stein Citation2022, 461). Eriksen and Stein (Citation2022, 475) argued that discourses of national exceptionalism relieve educational institutions from their pedagogical duties of challenging and unsettling unfair social dynamics.

Theoretical approach and central concepts

School leaders both shape and are shaped by the political economies of which they are a part. Due to their strategic placement within educational organizations, they can reinforce, recreate, and reshape these political economies (Courtney et al. Citation2021). By understanding racism as an expression of structural conflict operating through the everyday practices of individuals (Essed Citation1991), it is possible to understand principals as actors in this structure.

Inspired by Essed (Citation1991), this study is placed within the tradition that aims to understand the ways racism and antiracism are situated in systematic, recurrent, and familiar practices – that is, it is concerned with everyday racism. In Norwegian society, where discrimination is forbidden by law and racism is morally condemned, everyday racism may be seen as the main form of racism (Bangstad and Døving Citation2023). Everyday racism is racism that is integrated into daily life as a common societal behavior. It is racism, yet it is often seen as “innocent”, unproblematic, or even necessary by dominant groups. In the words of Essed (Citation1991), everyday racism is understood “in terms of practices prevalent in a given system” (3). Practices of everyday racism are based on relations of dominance where the dominant culture, norms, and values are seen as superior and “others” are constantly being managed and adjusted through different forms of cultural control. In the Dutch setting in the 1990s, where Essed wrote her seminal work on everyday racism, the discourse of tolerance was seen as an instrument that “conceals the emptiness of the promise of cultural pluralism” (Essed Citation1991, 6). In today’s Norwegian setting, discourses of tolerance and inclusion may do the same (Helland Citation2019). Specifically, in the educational setting, where school leaders bear a responsibility to mold young students into capable Norwegian citizens, there is reason to investigate closely the narratives of everyday racism.

According to Essed (Citation1991), practices of everyday racism show consistency at all levels of society. It is not the result of an individual issue or separate, unconnected events that happen by chance, nor is it solely a policy issue. Everyday racism also bares consistency across global settings (Essed et al. Citation2019). Essed (Citation1991) held that “it prevails the everyday practices by which the dominant group secures the status quo of race and ethnic relations” (6). It is not necessarily conscious; rather, it is deeply rooted in “‘hidden currents of the ideology of pluralism” (Essed Citation1991, 6). In Essed (Citation1991), these claims were based on the repetitive and uniform nature of experienced racism. In this article, the “hidden currents” of everyday racism are studied through the understanding of racism of powerful actors – namely, school leaders who are responsible for detecting, counteracting, and preventing racism. Hence, the direct experiences of racism from the perspective of minorities are not in focus, yet the undeniable existence of students’ experiences with racism and the characteristics of these experiences as common and repetitive (Proba Citation2023) are a given on which this study is based.

Racism may take the form of both action and nonaction. It is seen as operating on one level in terms of daily actions and on another level in the refusal to acknowledge racism or take responsibility for it (Essed Citation1991, 44). In the words of Essed (Citation1991),

Once we recognize that racial oppression is inherent in the nature of the social order, it becomes clear that the real racial drama is not racism but the fact that racism is an everyday problem. When (…) racism is transmitted in routine practices that seem “normal”, at least for the dominant group, this can only mean that racism is often not recognized, not acknowledged—let alone problematized—by the dominant group. To expose racism in the system we must analyse ambiguous meanings, explore hidden currents, and generally question what seems normal or acceptable. (p. 10)

Particularly relevant to understanding the lack of attention to racism among school leaders is the literature focusing on the denial of racism (Essed Citation1991; Lentin Citation2008, Citation2018). Here, the willingness needed to address racism is questioned. The denial of racism refers to a distinct lack of attention to race and racism characterized by dominant groups’ evasion or deflection of the moral responsibility and accountability for racism (Elias Citation2024). The denial of racism connects to the illusion of the “postracial” society (Goldberg Citation2015), where racism is viewed as a problem of the past. The mere existence of racism is constantly contested as experiences of racism are dismissed, disregarded, and not seen as relevant in policy and public discourse (Elias Citation2024; Essed Citation1991). It is linked to the condemnation of the blatant forms of racism that are often forbidden by law and social norms and the rewriting or ignoring of all other forms of racism (Essed Citation1991), but also, to new ways of denying the need to address racism. In more recent works, Essed has developed the concept of entitlement racism (Essed Citation2020; Essed and Muhr Citation2018). Entitlement racism refers to the insistence that freedom of expression gives everyone the right to say anything, also when it is racially offensive (Essed and Muhr Citation2018). Hence, the denial of racism is no longer completely concealed, it is also reframed as freedom of expression.

Methods

The goal of this study was to provide insight into school leaders’ counteraction of racism in the Norwegian context. To do so, I focused on what the principals said they did and how they justified their efforts. I drew on qualitative, semi-structured in-depth interviews (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2018) with a sample of 14 school principals of primary and lower secondary schools. By focusing on the principals’ self-interpretations, I gained insights into their understanding of racism and justifications for the efforts they chose to adopt. As described above, principals in Norway have a general mandate from policy and state curricula to counteract discrimination and threats to the psychosocial environment of students, yet they have the freedom to interpret their mandate as they wish. Hence, to understand how principals dealt with racism, long interviews with open questions could provide a relevant source of information. Given the design and low number of informants in this study, the aim was not to generalize the findings but rather to gain a deeper understanding of different narratives on racism. This approach made it possible to distinguish between a range of narratives and, hence, to distinguish between antiracist efforts as well as efforts serving alternative goals, such as masking or ignoring racism.

The principals were carefully and purposefully sampled (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2018) based on their interest in working against racism. All their schools had been nominated either for the Benjamin Prize for work against racism or the Queen Sonja’s School Award for inclusion and equality between 2017 and 2021. Hence, an underlying assumption was that these principals all had some degree of interest in working against racism. The principals included in the sample were from public schools. Schools with a large and small percentage of students from different language backgrounds were represented and that schools from different areas of Norway were included.

To my knowledge, the principals were all representatives of the majority population (White native speakers of Norwegian). Since there is very limited public registration of ethnic or religious backgrounds in Norway, some of the principals might have a minority background that was not visible, but none made any mention of this during their interviews. There were nine women and five men in the sample. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using NVivo software, which enabled the tracking and comparison not only of each informant but also of each effort across all the materials. All principals, their schools and locations were properly anonymized in the transcription. The main themes addressed during the interviews were: (a) the presence and manifestations of racism in society and in the local school context; (b) the efforts made to counteract racism, including why those efforts were prioritized; (c) the value of work against racism for the school; (d) the actors who were considered stakeholders in the work against racism; and (e) the mandate the school leaders perceived they had been given to work against racism.

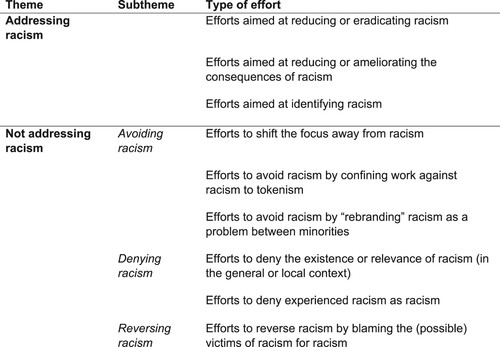

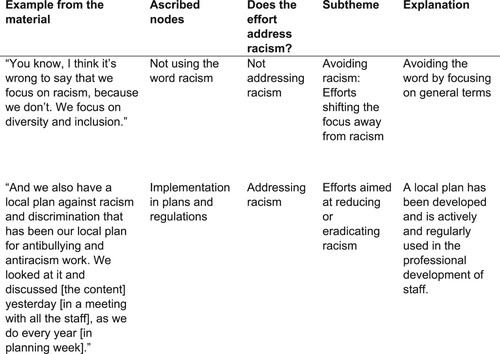

Content analysis of the transcribed interview data was conducted using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). First, I read the transcripts line by line, adding marginal notes, assigning nodes to segments of the material, and describing the meaning (see for examples from the process). In this process, all efforts that the principals associated with work against racism were identified (research question 1: What efforts did the principals focus on when discussing racism?). Then, the nodes were sorted into thematic categories or themes. Through the inductive process of ascribing nodes to the content, it became visible that many of the efforts described by the principals were not actually directed at counteracting racism but rather at not dealing with or not acknowledging racism. Hence, the categorization started with drawing a line between antiracist efforts and efforts clearly aimed at not addressing racism – for instance, stating that the school did not work directly against racism or that racism was not a relevant concern for the school. In the next step, I analyzed the content of each category via a deeper interpretation of each theme, grouping the efforts in each theme into subcategories. I focused on the contextualization of the efforts and manifestations of racism described by the participants within each category (research question 2: How did the principals justify their work against racism?). shows the process of analysis using two examples.

Figure 1. Examples from the coding process, with sample codes and explanations for how they led to the generation of key themes.

Through the analysis, the main themes of addressing racism and not addressing racism were identified. Not addressing racism included three subthemes: avoiding, denying, and reversing racism. shows descriptions of the efforts included in each theme.

Throughout the research process, I incorporated reflexive journal writing to trace my own positionality and my relationship with the data according to Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2022) recommendations. Since I am a White, predominantly Norwegian-majority representative who is a former teacher and a researcher within a somewhat polarized field, this process was important for me to understand the influence of my own biases and to use my positionality as a strength in the process.

Analysis

The interviews showed that while the principals used a wide range of efforts to address or not address racism, very few of the participants incorporated what could be understood as an overall antiracist practice at their schools, characterized by a wide range of efforts to address racism and a few efforts to avoid, deny, or reverse it. The incorporation of antiracism and the overall understanding of racism and the mandate varied greatly between the few principals who had made effort to address racism and the majority of principals who had made more effort not to address racism. In this analysis, I focus on the specific efforts used to avoid and deny racism and connect these to Essed’s (Citation1991) theory of everyday racism.

Importantly, racism was addressed by all principals to some degree, but the efforts varied. Very few principals acknowledged racism as a problem directly relevant to their schools; hence, few efforts were concrete and actionable. The reasoning behind the efforts to address racism followed three main purposes: reducing or eradicating racism, reducing or ameliorating the consequences of racism, and identifying experiences of racism. The most common efforts aimed at reducing or eradicating racism were increasing staff competence in racism and antiracism and incorporating preventive work into school plans. In working to ease the consequences of racism, the most common effort was instituting regulations and routines for dealing with incidents. A few principals adopted a wholesome approach to alleviating racism that included working to ease the societal and structural challenges of racism. While most principals believed that they did not need to investigate whether their students had experienced racism in school, some principals engaged in gathering specific data on students’ experiences or had plans and procedures in place to make these experiences known to the school.

Avoiding racism

The category includes all statements concerning efforts to shift the focus away from racism, efforts confining work against racism to tokenism, and efforts “rebranding” racism as a problem between minorities. Most of the principals used these different efforts to create detours around racism. In the analysis, these conceptions were interpreted as avoiding racism on the basis that they, in different ways, made a focus on racism unnecessary or even destructive for the students. For instance, the following statement was made about the term racism:

We don’t work specifically with the term “racism” because we wish to focus on the fact that we have mutual values and that we are all valued the same, no matter where we come from or what background we have.

Other reasons for avoiding the term “racism” were present. One principal expressed that it might stir up unnecessary fear, as they “didn’t know whether they [the students] had experienced it [racism]” and feared exposing students to harmful awareness by focusing on it. Another raised similar concerns, emphasizing that a focus on racism may cause a “victim mentality”:

They may have experienced a lot [of racism], or they may transfer others’ experiences to themselves because they have the same skin color, right? And they go around wondering if what they experienced was racism. When someone doesn’t sit next to you on the bus, you no longer have the same freedom as I [as a White person] have to think that it is random (…). And it’s about not making people into victims. One must work to be freed from that.

As a theme in the analysis, avoiding racism by avoiding the term indicates that the principals participated in established discourses of avoidance. Within this discourse, the legitimacy of students’ experiences of racism was questioned, along with their possible need to make sense of these experiences. Consequently, the opportunity to interpret racism as random, as oversensitivity, or as opportunism was enhanced. These practices may be seen as central to legitimizing everyday racism, embedding a “claim to mean well” (Essed Citation1991, 172) while pursuing a narrative of antiracism as problematic.

Other efforts used to avoid racism included different celebrations of diversity that, according to principals, made a focus on racism unnecessary, such as school songs, flags, and having students bring food from “their countries” to events; leaving responsibility to the teachers; or placing the responsibility on the parents (thereby outside the principals’ control or mandate). Furthermore, some principals hierarchically organized racism as a “lesser issue” than, for instance, prejudice against LGBTQ+ (making it less important to deal with). Another effort was to use narrow or vague definitions of the term “racism” and only deal with it if strictly necessary. According to one statement that underscored this: “We talk about it if we have to”.

While the focus on (empty) celebrations is connected to the much criticized practices of tokenism (Moreno Figueroa and Wade Citation2024), the avoidance of responsibility and the hierarchical downplaying of the importance of racism may be seen as legitimizing everyday racism. As Essed argued, legitimizing everyday racism is an essential part of established patterns of domination (Citation1991, 185). By constantly recreating patterns in which racism can or should be avoided, challenging racism becomes redundant. Hence, efforts of resistance, such as using the term “racism” and claiming that racism needs focus, are systematically dismissed.

Denying racism

The principals who engaged in the denial of racism did not accept racism as a construct or accept it as relevant to their context. A common method of denying racism in the material was to consider it a problem of the past or a problem in other places. The principals who positioned racism in the past typically focused on their schools as places where racism used to exist and where it was no longer a problem due to the work being done. Some also considered racism to be a problem in other schools, but due to either the diversity or lack of diversity in their own schools, this issue was seen as irrelevant to their contexts. Some principals also expressed that if anyone had experienced racism in their schools, they would surely have known about it, thereby ruling out the possibility of racism being an issue.

Principals engaged in the rewriting of experiences of racism. In these cases, minority students typically “misunderstood”. One principal shared a scenario in which a student reported feeling excluded by a group of girls in the class, with the student feeling that the exclusion was primarily due to her black skin:

I spoke with the students who were supposedly excluding this girl, and we agreed that the exclusion was in no way connected to the color of her skin but rather to her personality and type.

Racism was also considered a natural state by a few principals due to cultural differences and hostility and because group formation was “something that will just happen”:

I don’t really know how to get rid of such types of things (…) or, well, because they will always be prejudiced and these types of things (…) hm (…) against people from other cultures and nationalities. (…) It’s just the way it is, I guess.

Racism is connected to being an outsider and being outside “the Norwegian.” But what is Norwegian today? In such an open society as the Norwegian is today, this is about the fact that some choose to be on the outside.

Discussion

In the following discussion, I contextualize the findings by focusing on how avoidance and denial as approaches to racism reinforce practices of everyday racism. Then, the findings are viewed in connection with three intersecting aspects that may shed light on the tendencies of avoidance and denial of racism found in the material. The school leaders enacted their roles in relation to racism in ways that were defined not only by their personal choices but also by historical and cultural foundations of understandings of racism, by the specific conditions of their positions, and by the macro-level political contexts in which they were situated.

Obscuring racism and labeling it a nonissue

These findings demonstrate how the principals operated within different understandings of racism, avoiding racism by shifting focus, denying the existence of racism in their schools, or even reversing racism by blaming the minorities for being excluded or for somehow causing/provoking racism. Essed (Citation1991, 272) used the concept of cognitive detachment to describe how members of dominant groups neither understand nor are motivated to understand racism. This detachment may pave the way for denial and avoidance of racism in the sense that racism is not seen as the responsibility of the dominant group. Hence, everyday racism operates through the inaction of powerful actors – in this case, principals – who may choose not to see racism as a problem. These findings, then, reflect deeply rooted practices whereby everyday racism is not recognized or taken seriously and whereby not addressing racism may be considered a norm in schools. Importantly, these claims are not meant to be moral judgments upon the specific principals who participated in this study. The concern here is with their practices – or, rather, their own perceptions of these practices. Practices of avoidance and denial of racism stand in the way of antiracist change (Gümüş, Arar, and Oplatka Citation2021; Lynch, Swartz, and Isaacs Citation2017). If principals do not see the need to address racism, it is unlikely that their schools’ duty to denaturalize and disrupt racism will be fulfilled. By force of being leaders, principals bear a key responsibility for the “interweaving of racism in the fabric of the social system” (Essed Citation1991, 37). They are strategically placed to influence teachers, students, the community, and the very system within which they operate. By not engaging in antiracism, school leaders create an environment in which racism is not seen as relevant. Avoiding and denying racism may then have the effect of absolving educational institutions of their pedagogical responsibilities when it comes to racism.

Understanding avoidance and denial of racism

It is possible to understand the denial and avoidance of racism seen in this study as norms in Norwegian society, where discourses of national exceptionalism portray Norway as exceptionally good and innocent of historic atrocities such as colonialism and Holocaust (Eriksen and Stein Citation2022). Through a discourse of tolerance (Essed Citation1991, 274), where everyone has the same right to nondiscrimination, the divide between dominant and nondominant groups becomes invisible, yet it continues to operate hidden, often withdrawn from the consciousness of the dominant group. The reflections of the principals shown in the analysis portrayed examples of how nondiscriminatory self-images are reinforced. Racism is seen as important in principle, yet in practice, it is avoided and denied through different efforts that are justified through what can be understood as (White, “Norwegian”) “ideologically saturated definitions of reality” (Essed Citation1991, 273). If this normative reality is one in which racism is seen as nonexistent or counteracted through what are known to be ineffective strategies, the practices of denial and avoidance will not be understood as everyday racism or as clear threats to social justice and equitable education. In light of theoretical approaches to the denial of racism (Elias Citation2024; Lentin Citation2008; Citation2018), school leaders’ practices of not addressing racism may be seen as strategic – that is, whether conscious or unconscious, leaders seem to avoid racism. Elias (Citation2024), as did others (Ahmed Citation2007; Essed Citation1991; Lentin Citation2018), suggested that this avoidance may be connected to a structure of hegemonic power – and, hence, the maintenance of a social order that profits the dominant group.

In light of the increasingly high workload and conflicting pressure between administrative short-term tasks and long-term pedagogical development that mark Norwegian principal positions (Bjørnset and Kindt Citation2019), it is possible that there is simply not enough time to develop antiracist practices and that antiracism falls into the background among all the tasks that principals are supposed to be on top of. Racism and antiracism do not have a strong footing in Norwegian educational legislation, since the terms are not in use (Nyegaard Citationin review), and other concepts, such as inclusion and diversity, may provide false security that racism is sufficiently addressed. Entitlement racism (Essed Citation2020; Essed and Muhr Citation2018) may also be contributing to blurred lines between freedom of expression and racism. Enhanced by what Essed refers to as “the celebration of neo-liberal individualism to speak your mind” (Essed Citation2020, 444), school leaders are operating in a difficult climate. While racism is not directly in focus in the legislation, freedom of expression and ability to tolerate opposition is enhanced in the national curriculum (The Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training Citation2017), and hence, proactively addressing and moving against racism may be running the risk of being portrayed as one of many options that should be thoroughly weighted against other concerns, such as freedom of expression and learning to accept that people have “different opinions”.

Prioritizing racism may be particularly challenging in our time of neoliberal reforms within education, where measures such as standardized testing and the marketization of education have been found to reinforce unequal access to and gains from education along ethnic, cultural, and economic lines and, at the same time, individualize racism in the sense that it becomes a personal matter with presumably no need for political and systemic solutions (Au Citation2016; Bjordal, Citation2023; Gillborn and Youdell Citation1999). Principals stand in a position where there is pressure to provide output in the sense, for instance, of measurable results in standardized tests and where output-orientated efforts may be given a higher priority than making sure that schools are promoting true social justice.

Concluding remarks

Contemporary societies, including Norway, are marked by the growing popularity of populist right-wing political parties, strong anti-immigrant movements, and anti-antiracism. Further research on how these factors affect school leaders’ work against racism is needed. For educational practice, this study underscores the importance of creating antiracist structures within education, training leaders to understand racism in their local contexts and to critically and reflexively examine what goes on in their schools and society. School leaders, as antiracist actors, may equip staff and students with the knowledge and skills to confront racism, promote democratic citizenship, and ensure that education serves as a catalyst for positive social change.

Statement of ethics

This study has been reviewed by and received ethics clearance from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, project number: 214114. Date 25 July 2022.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their insightful comments. I am also grateful to the CLEG research group at the University of Oslo and the research group at the Norwegian Center of Holocaust and Minority Studies for comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2007. “‘You End up Doing the Document Rather than Doing the Doing’: Diversity, Race Equality and the Politics of Documentation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (4): 590–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701356015.

- Arneback, E., and A. Quennerstedt. 2016. “Locations of Racism in Education: A Speech act Analysis of a Policy Chain.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (6): 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1185670.

- Au, W. 2016. “Meritocracy 2.0.” Educational Policy 30 (1): 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815614916.

- Aveling, N. 2007. “Anti-Racism in Schools: A Question of Leadership?” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 28 (1): 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300601073630.

- Bangstad, S., and C. A. Døving. 2023. Hva er rasisme. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Ben, J., D. Kelly, and Y. Paradies. 2020. “Centemporary Anti-racism.” In Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racisms, edited by J. Solomos. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351047326.

- Benner, A. D., Y. Wang, Y. Shen, A. E. Boyle, R. Polk, and Y.-P. Cheng. 2018. “Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Well-being During Adolescence: A Meta-analytic Review.” American Psychologist 73 (7): 855. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000204.

- Bezrukova, K., K. A. Jehn, and C. S. Spell. 2012. “Reviewing Diversity Training: Where we Have Been and Where we Should Go.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 11 (2): 207–227. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2008.0090.

- Bjordal, I. 2023. “Markedsretting av utdanning og strukturell rasisme.” Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift 7 (1): 8–22. https://doi.org/10.18261/nost.7.1.2.

- Bjørnset, M., and M. T. Kindt. 2019. “Fra galionsfigur til overarbeidet altmuligmann, Report 37/2019.” Fafo. https://www.fafo.no/images/pub/2019/20734.pdf.

- Bogotch, I. E. 2002. “Educational Leadership and Social Justice: Practice Into Theory.” Journal of School Leadership 12 (2): 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460201200203.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

- Brinkmann, S., and S. Kvale. 2018. Doing Interviews. 2nd ed. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529716665.

- Brooks, J. S., and T. N. Watson. 2019. “School Leadership and Racism: An Ecological Perspective.” Urban Education 54 (5): 631–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918783821.

- Bufdir. 2021. Deltakelse i utdanning blant samer, nasjonale minoriteter og personer med innvandrerbakgrunn. https://www.bufdir.no/statistikk-og-analyse/etnisitet-religion/deltakelse-utdanning.

- Chinga-Ramirez, C. 2017. “Becoming a “Foreigner”: The Principle of Equality, Intersected Identities, and Social Exclusion in the Norwegian School.” European Education 49 (2–3): 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2017.1335173.

- Courtney, S. J., H. M. Gunter, R. Niesche, and T. Trujillo. 2021. Understanding Educational Leadership: Critical Perspectives and Approaches. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- The Education Act. 1998. LOV-1998-07-17-61 C.F.R.

- Elias, A. 2024. “Racism as Neglect and Denial.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 47 (3): 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2181668.

- Erdal, M. B., and M. Strømsø. 2021. “Interrogating Boundaries of the Everyday Nation Through First Impressions: Experiences of Young People in Norway.” Social & Cultural Geography 22 (1): 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1559345.

- Eriksen, K. G., and S. Stein. 2022. “Good Intentions, Colonial Relations: Interrupting the White Emotional Equilibrium of Norwegian Citizenship Education.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 44 (3): 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2021.1959210.

- Essed, P. 1991. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Vol. 2. California: Sage.

- Essed, P. 2020. “Humiliation, Dehumanization and the Quest for Dignity: Researching Beyond Racism.” In Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racisms, edited by J. Solomos, 442–455. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Essed, P., K. Farquharson, E. J. White, and K. Pillay. 2019. Relating Worlds of Racism: Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European Whiteness. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Essed, P., and S. L. Muhr. 2018. “Entitlement Racism and its Intersections: An Interview with Philomena Essed, Social Justice Scholar.” Ephemera 18 (1): 183–201.

- Führer, L. 2021. “‘The Social Meaning of Skin Color’: Interrogating the Interrelation of Phenotype/Race and Nation in Norway.” PhD doctoral diss., University of Oslo. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/88955/PhD-Fuehrer-2021.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Gillborn, D., and D. Youdell. 1999. Rationing Education: Policy, Practice, Reform, and Equity. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2015. Are We All Postracial Yet?. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gooden, M., and V. Showunmi. 2021. “Race and Educational Leadership.” In Understanding Educational Leadership. Critical Perspectives and Approaches, edited by S. J. Courtney, H. M. Gunter, R. Niesche, and T. Trujillo, 281–294. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gorski, P. 2019. “Avoiding Racial Equity Deto.” Educational Leadership 76 (7): 56–61.

- Gullestad, M. 2002. “Invisible Fences: Egalitarianism, Nationalism and Racism.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8 (1): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.00098.

- Gümüş, S., K. Arar, and I. Oplatka. 2021. “Review of International Research on School Leadership for Social Justice, Equity and Diversity.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 53 (1): 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2020.1862767.

- Harlap, Y., and H. Riese. 2021. ““We Don’t Throw Stones, we Throw Flowers”: Race Discourse and Race Evasiveness in the Norwegian University Classroom.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1218–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1904146.

- Helland, F. 2019. Rasismens retorikk- Studier i norsk offentlighet. Pax forlag.

- Human Rights Act. 1999. LOV-1999-05-21-30 C.F.R.

- Jore, M. K. 2018. “Fortellinger om 1814: Forestillingen om det eksepsjonelle norske demokrati” [Narratives of 1814: the notion of the exceptional Norwegian democracy]. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 2 (1): 72–86. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2270.

- Khalifa, M. A., M. A. Gooden, and J. E. Davis. 2016. “Culturally Responsive School Leadership.” Review of Educational Research 86 (4): 1272–1311. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316630383.

- Khalifa, M. A., D. Khalil, T. E. J. Marsh, and C. Halloran. 2019. “Toward an Indigenous, Decolonizing School Leadership: A Literature Review.” Educational Administration Quarterly 55 (4): 571–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18809348.

- Kumashiro, K. K. 2000. “Toward a Theory of Anti-oppressive Education.” Review of Educational Research 70 (1): 25–53. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070001025.

- Lentin, A. 2008. “Europe and the Silence About Race.” European Journal of Social Theory 11 (4): 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431008097008.

- Lentin, A. 2016. “Racism in Public or Public Racism: Doing Anti-racism in ‘Post-racial’ Times.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (1): 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096409.

- Lentin, A. 2018. “Beyond Denial: ‘Not Racism’ as Racist Violence.” Continuum 32 (4): 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1480309.

- Lynch, I., S. Swartz, and D. Isaacs. 2017. “Anti-Racist Moral Education: A Review of Approaches, Impact and Theoretical Underpinnings from 2000 to 2015.” Journal of Moral Education 46 (2): 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1273825.

- Midtbøen, A. H., J. Orupabo, and A. Røthing. 2014. Etniske og religiøse minoriteter i læremidler: Lærer-og elevperspektiver. Report 8277634447. Institutt for Samfunnsforskning. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2387339.

- Miller, P. 2019. “Race and Ethnicity in Educational Leadership.” In Principles of Educational Leadership & Management, edited by T. Bush, D. Middlewood, and L. Bell, 3rd ed., 223–238. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Miller, P. 2020. “Anti-Racist School Leadership: Making ‘Race’ Count in Leadership Preparation and Development.” Professional Development in Education 47 (1): 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1787207.

- Moeller, K. 2021. “The Politics of Curricular Erasure: Debates on Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Brazilian ‘Common Core’ Curriculum.” Race Ethnicity and Education 24 (1): 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1798382.

- Møller, J. 2021. “Images of Norwegian Educational Leadership – Historical and Current Distinctions.” In The Cultural and Social Foundations of Educational Leadership: An International Comparison, edited by R. Normand, L. Moos, M. Liu, and P. Tulowitzki, 67–82. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Moreno Figueroa, M. G., and P. Wade. 2024. “Introduction: The Turn to Racism and Anti-Racism in Latin America.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2311–2325. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2024.2329335.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2017. Core Curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2023. Krav og forventninger til en rektor. https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/etter-og-videreutdanning/rektor/krav-og-forventninger-til-en-rektor/.

- Nyegaard, S. B. in review. Hvilke rammer gir læreplanverket for skolens antirasistiske arbeid?

- OECD. 2023. Equity and Inclusion in Education. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/e9072e21-en.

- Osler, A., and H. Lindquist. 2018. “Rase og etnisitet, to begreper vi måsnakke mer om.” Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift 102 (1): 26–37. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2018-01-04.

- Paradies, Y., J. Ben, N. Denson, A. Elias, N. Priest, A. Pieterse, and G. Gee. 2015. “Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS ONE 10 (9): e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

- Paradies, Y., L. Chandrakumar, N. Klocker, M. Frere, K. Webster, M. Burrell, and P. McLean. 2009. Building on Our Strengths: A Framework to Reduce Race-based Discrimination and Support Diversity in Victoria. Victoria: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation.

- Pedersen, A., I. Walker, Y. Paradies, and B. Guerin. 2011. “How to Cook Rice: A Review of Ingredients for Teaching Anti-prejudice.” Australian Psychologist 46 (1): 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00015.x.

- Pollock, M. 2006. “Everyday Antiracism in Education.” Anthropology News 47 (2): 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1525/an.2006.47.2.9.

- Proba. 2023. Barn og unges erfaringer med rasisme og diskriminering. Report 19-2023. Oslo: Proba. https://proba.no/wp-content/uploads/Rapport-2023-19-Barn-og-unges-erfaringer-med-rasisme-og-diskriminering.pdf.

- Rejón Piña, R. A. 2023. “Avoiding Backlash: Narratives and Strategies for Anti-Racist Activism in Mexico.” Ethnicities 23 (6): 843–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968221128381.

- Røthing, Å. 2015. “Rasisme som tema i norsk skole – Analyser av læreplaner og lærebøker og perspektiver på undervisning.” Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift 99 (2): 72–83. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2015-02-02.

- Seikkula, M. 2022. “Affirming or Contesting White Innocence? Anti-racism Frames in Grassroots Activists’ Accounts.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (5): 789–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1897639.

- Shields, C. M. 2010. “Transformative Leadership: Working for Equity in Diverse Contexts.” Educational Administration Quarterly 46 (4): 558–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X10375609.

- Statistics Norway. 2023a. Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/innvandrere-og-norskfodte-med-innvandrerforeldre.

- Statistics Norway. 2023b. Elevar i grunnskolen. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/grunnskoler/statistikk/elevar-i-grunnskolen.

- Svendsen, S. H. B. 2014. “Learning Racism in the Absence of ‘Race’.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 21 (1): 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506813507717.

- Tanner, M. N., and A. D. Welton. 2021. “Using Anti-racism to Challenge Whiteness in Educational Leadership.” In Handbook of Social Justice Interventions in Education, edited by C. A. Mullen, 395–414. Cham: Springer.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 2023. Sannhet og forsoning – grunnlag for et oppgjør med fornorskningspolitikk og urett mot samer, kvener/norskfinner og skogfinner. Rapport til Stortinget fra Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen (Dokument 19 (2022–2023)).

- Wade, P. 2024. “Working against racism: lessons from Latin America?.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 47 (11): 2456–2476. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2024.2329339.

- Wiltgren, L. 2023. “‘So Incredibly Equal’: How Polite Exclusion Becomes Invisible in the Classroom.” British Journal of Sociology of Education, 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2023.2164844.