ABSTRACT

While antiracist protest has gained increasing prominence in Europe in recent years, the lack of representative data has so far prevented an assessment of the scope and drivers of antiracist protest outside of the United States. This paper addresses this gap drawing from a unique survey (N = 5003) on racism in Germany. Building upon sociological and social psychological theories of protest, the article explores the scope and role of key demographic, cognitive, and emotional factors for protest practice and protest potential. Our data suggests that antiracist protest is supported by considerable parts of German society and finds that mediated experiences of racism and emotional reactions matter as drivers of mobilization: those with and without a personal experience of racism are more likely to protest if they were told of racist experiences by others. This effect is even more pronounced if participants are emotionally affected by personal and mediated experiences of racism.

Introduction

In recent years, antiracist mobilization has gained prominence not only in the U.S. but also in various European countries, where tens of thousands joined the 2020 wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests (Milman et al. Citation2021). While patterns of participation and public support of racial justice movements are widely researched for the U.S. context (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022; Baskin-Sommers et al. Citation2021; Dunivin et al. Citation2022; Heaney Citation2022), survey-based research on antiracist protest in Europe is still in its infancy. Given the distinct histories of antiracist mobilizations, discourses on racism, and demographic compositions in the U.S. and in European countries, it remains an open empirical question if patterns and drivers of participation in and support for antiracist action differ cross-nationally (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022, 15). Against this background, this article draws from a unique representative survey on the topic of racism in Germany (N = 5003) conducted between April and August 2021 to assess the scope and explore drivers of antiracist protest participation and support in Germany.

Our data suggests that antiracist protest is supported by considerable parts of German society. When it comes to drivers of antiracist protest, we find that experiences of racism and emotions matter. We differentiate between firsthand “personal” experiences of racism and “mediated” experiences through interpersonal reports. Our data suggests that those with and without a personal experience of racism are more likely to protest if they have been told of racist experiences by family, friends, or acquaintances. Additionally, such mediated experiences of racism fueled the effects of personal experiences on protest behavior, indicating that sharing experiences is more important than personal affectedness as such. Finally, we find that this effect is even more pronounced if participants are emotionally affected by their personal and mediated experiences of racism. The paper thereby makes an empirical contribution to the understanding of antiracist protest outside the U.S. and advances theoretical debates on drivers of protest.

To unfold our argument, the paper is structured as follows: first, we embed our study in theories of protest participation and support to situate our analytical focus; second, we briefly contextualize racism and its contestation in Germany and third, we discuss the data and methods used. Fourth, we explore of the scope, demographic patterns and key drivers of antiracist protest practice and potential in Germany focusing on personal and mediated experiences of racism. Lastly, we discuss the theoretical and methodological implications of our findings and sketch-out research desiderata on the contentious politics of (anti)racism in Europe.

Theorizing antiracist protest participation and protest potential

Abundant literature on individual protest participation in sociology and social psychology has pointed at different types of factors related to resource availability, identity, and emotions. It has been argued that since protest requires the investment of considerable resources such as time and opportunity costs, individuals with more resources are more likely to engage in protest (Klandermans et al., Citation2008, 994). Similarly, individuals marginalized through racialization are considered less likely to engage in protest (Rojas, Heaney, and Adem Citation2023). Variants of this general argument point at the role of social networks and “biographical availability” (McAdam Citation1986), expecting individuals with larger social networks and those without care work duties or demanding full-time jobs to be more likely to engage in activism. Yet, while such patterns have been shown for the propensity to use protest as a form of action in general, research based on on-site protest surveys has found considerable differences in the socio-demographic profile of protesters depending on the protest topic (Daphi et al. Citation2023; Fisher and Rouse Citation2022). Beyond socio-structural characteristics, the affective turn in social movement studies has pointed to the role of emotions as important drivers of protest (Jasper Citation2011).

Partly resonant with this literature on collective action outlined above, specific literature has theorized the varied forms of antiracist action. As a social relationship of domination and (structural) violence, racism is historically intertwined with antiracist opposition (Lentin Citation2004; Oldfield Citation2013), ranging from individualized forms of everyday resistance by racialized groups and individuals acting in solidarity (Ellefsen, Banafsheh, and Sandberg Citation2022; Lamont et al. Citation2016; Radke et al. Citation2020) to large-scale antiracist social movements and protest (Lentin Citation2004; McAdam Citation1986; Woodly Citation2022).

In recent years, particularly related to the proliferation of the BLM movement, a growing literature has investigated the determinants of support for and participation in racial justice protests in the United States (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022). This literature has found that racial justice protests are disproportionally attended by racialized groups, particularly Black people (Rojas, Heaney, and Adem Citation2023). Leach and Allen have argued: “Likely because Black people have greater personal experience, and historical context, for racial bias, they are the most opposed to it in attitude and most ready to act against it through protest and other means” (Leach and Allen Citation2017, 545). In this line, Azevedo et al. have found that self-identifying as Black is a strong predictor for antiracist protest support in the U.S. (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022). However, personal experiences of racial discrimination as an explanatory factor have yielded inconclusive results. One of the few studies on BLM protests in Europe found that “[a]ll but two of the ethnic minority participants reported they had experienced or witnessed racism and most stated that this was important for their mobilization” (Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022, 1109). Quantitative studies on the U.S. context, however, have shown insignificant associations between a personal experience of discrimination and BLM protest support (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022).

Scholars have attributed these inconclusive results to the ambivalent emotions personal experiences of racist discrimination can evoke. It has been shown that some emotions such as anger about social inequalities can spark collective action by racialized groups, whereas others, such as fear, can also lead to withdrawal (Banks, White, and McKenzie Citation2019; Foster and Matheson Citation1998) or other similar coping strategies. Qualitative research on BLM in Norway concluded that “emotions played a crucial role before, during and after the BLM protests in 2020” (Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022).

Another strand of literature has pointed at the role of social identity to explain movement participation that goes beyond the role of personal experiences of protesters. The evidence is mixed on how relevant personal experiences of being disadvantaged or protester’s identity as a member of an aggrieved group is. On the one hand Thomas, Zubielevitsch, and Osborne (Citation2020) found that identification with one’s ethnic group and the subjective feeling of collective relative deprivation motivate engagement in collective action among structurally disadvantaged groups. Shared grievances even foster collective identities that focus on political protests to challenge the status quo beyond specific ethnic identities (Simon and Klandermans Citation2001). On the other hand, being affected by racism may also have demobilizing effects (Foster and Matheson Citation1998; Lems Citation2021), indicating that other variables may play a role for translating a common grievance into collective action.

Furthermore, structurally advantaged groups also frequently engage in collective action on behalf of disadvantaged groups, as they develop a politicized identity and respond to perceived injustice (Thomas, Zubielevitsch, and Osborne Citation2020). Social psychological research documents that, for example, mobilization for gender equality is motivated by the attitude towards gender equality rather than gender identity (Subašić et al. Citation2018). Relatedly, individuals who strongly identify with a movement’s cause are more likely to engage in activism (Thomas, Mavor, and McGarty Citation2012), which can motivate a heterogeneous array of protest participants (Hechler et al. Citation2024). Indeed, advantaged (white) people also engage in antiracist collective action: Next to group and self-serving goals, white people who emotionally engage with the experience of racialized people may sense a shared superordinate identity that motivates action on their behalf (Radke et al. Citation2020).

In a similar vein, research on the U.S. context has found cognitive awareness and social relations with members of disadvantaged groups to be important predictors of protest support. When it comes to cognitive processes of problem recognition, an extensive meta-analysis of BLM support in the U.S. has consistently documented that “the more individuals recognize racial discrimination to be a pervasive issue in America, the more they support the BLM movement” (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022, 1311). It has been furthermore shown that an acknowledgment of the structural features of racism is a strong predictor of BLM support (Miller, O’Dea, and Saucier Citation2021).

In addition, intergroup contact theory (Allport Citation1954) suggests that contact with racialized groups is positively related to support for antiracist collective action. In this line, studies have found that contact to Black people has increased the support for antiracist collective action among white U.S. Americans (Selvanathan et al. Citation2018). Similarly (Uluğ and Tropp Citation2021) have shown that experiences that were mediated by others, such as witnessing racist discrimination, increase the awareness of racial privilege among white individuals, which in turn increases the likelihood to engage in collective action.

Context: from racial amnesia to contentious (anti)racism in Germany

Before we turn to the empirical analysis of contemporary patterns of antiracist protest and protest potential, we set the stage with a contextualization of racism and its contestation in Germany. Even though the social movements for racial justice evolving in Europe during 2020 related to BLM in the U.S. (della Porta et al. Citation2023), there are differences between protesters’ characteristics due to the different social contexts the movements are based in. Accordingly, some drivers of protest are likely to vary in their relevance across space. Therefore, bridging theories of (antiracist) protest mobilization to the specific context of Germany, we can formulate guiding expectations for our empirical analysis.

First, Germany has been characterized by a pronounced reluctance to engage with race and racism after the National Socialist racist rule (Beaman Citation2021; Chin et al. Citation2009; El-Tayeb Citation2020). According to Chin and Fehrenbach, “the term Rasse has virtually disappeared from the German lexicon and public discourse since 1945 despite the persistence of social ideologies and behaviors that look an awful lot like racism” (Chin and Fehrenbach Citation2009, 3). The racist Nazi ideology and genocidal violence of the Shoa was followed by a silence about issues of race in the postwar period. The resulting “post-racial” narrative (Roig Citation2017, 617) cemented the reduction of racism to a historical phenomenon, and the widespread externalization to contexts outside of Germany including Apartheid South-Africa or the United States. Manifestations of racism in Germany were instead “subsumed […] under the category of xenophobia (Ausländer – oder Fremdenfeindlichkeit) – a trivialization very much at odds with social reality” (al-Samurai Citation2004, 165, emphasis in original).

As a result of a closed discursive context regarding issues of race and racism, antiracist activism in Germany has historically predominantly emerged from societal niches spearheaded by groups who personally experienced racism. These included Sinti and Roma (Matras Citation1998; Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma Citation2017), migrant workers from Turkey and other countries (Bojadzijev Citation2008), as well as Black Germans (Florvil Citation2020; Oguntoye, Opitz, and Schultz Citation1995). Indeed, those mobilizing as “Black Germans” did not only include individuals of mixed-race descent and individuals with ancestry from Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, Latin America, and the United States, but also other People of Color who understood Black to be a political identity for community building and activism. (Florvil Citation2020, 4). Accordingly, activists bridged different migrant and non-migrant identities based on a shared experience of racialization. As a result of this specific historical and societal context, debates on racism in Germany – in contrast to the U.S. – never focused exclusively on anti-Black racism (or Black antiracist mobilizing), reflecting the distinct historic logics of racialization in the country. Nevertheless, common grievances of the different racialized groups may fuel antiracist protests in Germany as they share the personal experience of being targets of racist violence, discrimination and disadvantages (e.g. Thomas, Mavor, and McGarty Citation2012). We thus formulate a first expectation for the German context:

H1: Personal experiences of racism are positively associated with antiracist protest practice and protest potential.

In addition to mobilizations pioneered by groups affected by personal experiences of racism, leftist groups have also engaged in mobilizations, yet, often framed as an element of anti-fascism or mobilizations against the far-right (Bhattacharyya, Virdee, and Winter Citation2020; Lentin Citation2008) with a tendency to “underestimate the fact that racism is embedded and diffused in various state institutions” (Hechler and Essien Citationforthcoming; Perolini Citation2022).

While antiracist protest – typical for protest in general – has occurred in waves in Germany, often sparked by cases of racist violence, broader and more continuous debates on race and racism have unfolded since the mid-2000s (Steinhilper et al. Citation2024; Zajak, Steinhilper, and Sommer Citation2023), following the increasing recognition of Germany as a racially diverse or “post-migrant” society (Foroutan Citation2019). As a result, racism has increasingly become a central element in broader mobilizations for social justice, against the far right or in support of migrant rights (Perolini Citation2022; Stjepandić, Steinhilper, and Zajak Citation2023). While antiracism is likely to remain strong among persons leaning towards the left of the political spectrum (see Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022 for the U.S.), actors in antiracist mobilization diversified with partly overlapping and partly diverging frames and agendas. The common denominator of this heterogeneous field of action, might thus be the acknowledgement of racism in Germany.

H2: The acknowledgement of racism is positively associated with antiracist protest practice and protest potential.

The antisemitic and racist terror attacks in Halle in October 2019 and Hanau in February 2020 have ignited societal debates on antisemitism, racism, and far-right violence. Despite this visible discursive opening and growth of a post-migrant civil society with a strong antiracist identity, many observers were astonished by the resonance of the BLM mobilizations in response to the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, which pushed the visibility of antiracist mobilization and the salience of racism to new levels in Germany (Zajak, Steinhilper, and Sommer Citation2023). These exposures to racist violence and discrimination, which were mediated via public discourses, can also be accompanied by feelings of solidarity that motivate racialized people as well as white allies to engage in antiracist action (Radke et al. Citation2020; Uluğ and Tropp Citation2021). The new debates on racism in Germany may have also sparked that experiences of racism were shared and mediated experiences of racism through the stories of others became more frequent and more emotional (Selvanathan et al. Citation2018). Thus, the German antiracist movement may be based on solidary action by people who uphold social networks with racialized people, and have been told about racist discrimination of others:

H3: Mediated experiences of racism are positively associated with antiracist protest practice and protest potential.

H4: The combination of personal and mediated experiences of racism are positively associated with antiracist protest practice and protest potential.

H5: Stronger emotional reactions to personal or mediated experiences of racism are positively associated with antiracist protest practice and protest potential.

As this account suggests, antiracism has gained increasing traction in recent years and mobilized actors seem to have become increasingly heterogeneous. Yet, the lack of representative data has so far prevented a macroscopic assessment of the scope and characteristics of antiracist protest. Against the background of these insights on protest participation and antiracist collective action, we use the outlined hypotheses to structure our exploration of antiracist protest participation and protest potential in Germany.

Data and methods

We draw from a population survey on racism in Germany conducted using Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI). The sample (N = 5003) is representative for the German population between 14 and 67 years in German-speaking private households. Since landline connections are unevenly distributed among the population, a “dual frame” approach was implemented that included both landline and mobile phones. The landline sample was drawn on the basis of the data provided by the Federal Network Agency, while mobile numbers were randomly selected through the Gabler-Häder-Method (Häder and Häder Citation2014). The final sample consisted of 2,820 persons that were contacted through landline (56.4 per cent) and 2,183 contacted through mobile phone numbers (43.6 per cent), respectively. The questionnaire was constructed as part of the National Discrimination and Racism Monitor project by the German Centre for Integration and Migration Research. The market and opinion research institute BIK ASCHPURWIS + BEHRENS GmbH carried out the survey.

No formal ethics approval could be obtained for the study on which our secondary data analysis is based, since no ethics committee was in place at the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM) by the time the survey was conducted. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

To allow for more reliable inference on the German population, weights were applied to the data. Design weighting was used to balance the different ways participants were selected. Additionally, a non-response weighting was used to adjust the collected data based on known parameters of the population. The characteristics that we considered for weighting included gender, age, and employment status, as obtained from the “micro census” (official annual statistical survey on population data in Germany). Missing values were deleted case wise; the survey was fielded between April and August 2021.

Participants were asked a broad range of questions related to racism in Germany. For this article, we resort to two items on protest practice and protest potential as dependent variables. Participants were asked if they have attended an antiracist demonstration in the past five years (protest practice), and if they would potentially attend such a demonstration (protest potential) or not.

The survey assessed sociodemographic variables (i.e. age, gender, level of education, and region of residence), as well as participants’ racialized group status and political party preference. For the former, participants were asked if they self-identify as belonging to a list of racialized groups or not.Footnote1 The categories “Asian”, “Black”, “East-European”, “Jewish”, “Muslim” and “Sinti or Roma” were provided as they reflect the most common groups affected by racism in the German context. Participants that identified with at least one of these groups were then summarized as being racialized, whereas people that selected “none of these groups” were considered as non-racialized. Political orientation was indirectly collected based on the participants’ voting preference (right wing = Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU), Free Democratic Party (FDP), Alternative for Germany (AfD); left wing = Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Green Party (Bündnis 90/die Grünen), Left Party (Die Linke); others = other party, I do not vote, I am not eligible to participate in the federal election).

Our main predictors concerned acknowledgement of racism, as well as personal experiences of racism and mediated experiences and the emotional reaction to these experiences. To investigate the degree to which racism is acknowledged as a problem, participants agreed or disagreed to five statements on racism in Germany (e.g. “There is racism in Germany”, “Racial discrimination exists in German authorities”, “Racism is part of everyday life in Germany”, “We live in a racist society”, “Most people are racist sometimes”). The scale showed sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

Participants were asked if they had ever experienced racism in their lives (yes, no) to assess personal experiences of racism. In terms of the consequences of these personal experiences of racism, participants were additionally asked how much these experiences affected them emotionally. As a first follow-up, it was assessed if these racism experiences have stirred them emotionally, followed by the question, if they had to think about these experiences later. Both items were initially measured on a 4-point scale (from 1 = applies not at all to 4 = fully applies) and summarized to indicate emotional experiences (r = 0.65). For the following analyses, the emotional reaction to personal experiences of racism was dichotomized. So, a person was coded to have an emotional reaction if at least one of both emotional reactions applied (see below for a detailed description).

Irrespectively of their personal experience of racism, mediated experiences of racism were assessed. Participants were asked if they have contact with persons belonging to the list of racialized groups described above.Footnote2 If yes, they were asked whether they have been told about racist experiences by their family, friends, or acquaintances (yes, no). Once again, the two follow-up questions on emotional reactions to mediated racism were summarized into a single variable (r = 0.61) and dichotomized.

In our analysis, we proceed in three steps. First, we provide descriptive evidence on the patterns of antiracist action in Germany related to demographic variables. Second, we present findings from multinomial logit regression models predicting the likelihood of engaging in antiracist protest (protest practice) and willingness to do so in the future (protest potential) in dependency of the occurrence of a certain event (for example, that participants personally experienced racism). The analysis is structured along the guiding hypotheses presented above. Accordingly, we focus on the role of personal experiences of racism (H1), cognitive acknowledgement of racism (H2), mediated experiences of racism (H3) as well as emotional reactions to personal and mediated experiences of racism (H5). Third, to further examine the interplay of personal and mediated experiences (H4), we included specific interactions in a second model. For example, experiences were recoded among participants who had a personal but not a mediated experience, a personal and a mediated experience, or a personal and a mediated experience that included an emotional response. All models were weighted and controlled for the age, gender, and education of participants.

Results I: scope and patterns of antiracist protest and protest support

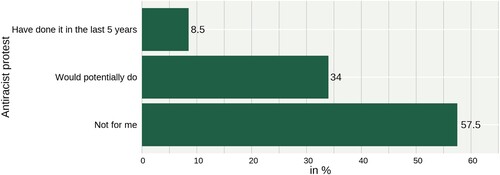

Our data documents that 8.5 per cent of the population in Germany have attended a demonstration against racism in the past five years preceding the survey, and an additional 34.0 per cent would potentially do so in the future (). This amounts to an antiracist mobilization potential or attitudinal support of 42.5 per cent.

The data indicates that antiracist mobilization in Germany has become fairly widespread in its practice and mobilization potential by the time the survey was conducted. It is likely that the increasing salience of racism resulting from the racist terror attacks in Halle and Hanau in 2019 and 2020 as well as the wave of Black Lives Matter protests has pushed the proliferation of antiracist action.

Regarding the socio-demographics of those engaged in antiracist action or willing to do so, findings correspond with the literature on the U.S. context (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022), that young persons are more frequently engaged in antiracist protest ().

Table 1. Socio-demographics and antiracist protest practice and potential in Germany.

This is most apparent for the youngest age group between 14 and 24, in which 63.8 per cent have either attended a protest or can imagine doing so in the future. In a similar vein, we find that regarding education, those still in school most frequently engaged in and support antiracist protest. However, when it comes to gender, the differences remain marginal with female participants being only slightly more frequently active. Also, related to racialized group status, the descriptive findings echo the U.S. context, with a disproportional antiracist protest participation and support from participants self-identifying with a racialized group.Footnote3 Nevertheless, the data indicates that anti-racism engagement has left the societal niche of marginalized groups and about 40.5 per cent of non-racialized participants demonstrate (potential) protest behavior.Footnote4

Based on these descriptive analyses, we turn to multivariate analyses to assess drivers for antiracist protest practice and potential.

Results II: drivers of antiracist protest and protest support

In the following, we present findings based on multinomial logit regression models for our dependent variables protest practice and protest potential. We present predictive margins for a variety of independent variables shown below. To obtain a specific predictive value of particular events (i.e. participants personally experienced racism or participants did not experience racism), we categorized all predictors: the racism acknowledgment scale was split mid-scale, with higher scores (2.5–4) reflecting an acknowledgement of racism in Germany and lower one’s no acknowledgement (1–2.49). Further, we re-coded personal experience of racism into three levels “did not experience racism” if participants indicated that they have never been targets of racism (77.8 per cent), “experienced racism” if participants indicated that they have experienced racism but did not report any emotional reactions to it (6.5 per cent), and finally “personal experienced racism and emotionally affected” if participants reported both: having personally experienced racism and reacted emotionally to it (15.7 per cent). A similar coding was applied to mediated experiences of racism, which then demonstrated the levels of “not been told about racism experience” (51.3 per cent), “only been told about racism experience” (9.8 per cent), “been told and reacted emotionally to it” (38.9 per cent).

The models for protest practice and protest potential were estimated jointly but presented separately. Regression tables can be found in the online supplement.

Protest practice

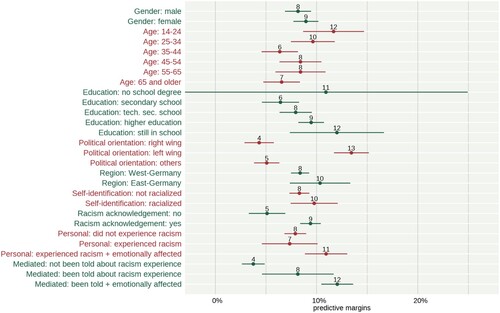

In contrast to the descriptive evidence presented above, multivariate results that are adjusted for all predictors in the model reveal that gender, education, and racialized group status do not constitute statistically significant drivers for antiracist protest practice (see ). Regarding age, instead, we find a clear negative association with protest practice. The probability of the youngest age group in the sample to engage in antiracist protest is more than twice as high as that of the oldest age group (13 vs. 6 per cent). As expected, participants who are politically left-leaning protest more often than those who are politically right-leaning or voted for other parties. We do not find differences concerning participants from Western or Eastern Germany.

Figure 2. Predictive margins, dependent variable = protest practice (in %, N = 4.854).

Note: Results of the multinomial regression analysis, controlled for all predictors in the model; error bars indicate 95%-confidence intervals of predicted margins; results weighed by population parameters.

Regarding the cognitive and emotional drivers of protest, the multivariate model yields positive associations between the acknowledgement of racism and antiracist protest practice. Those who acknowledge that racism constitutes a problem in Germany are more likely to have been protesting racism in the last five years than people that acknowledge it less. The difference of five percentage points is statistically significant ( and regression coefficients in the online supplement, Table A1). Furthermore, we find a mixed pattern regarding the effects of personal and mediated experiences of racism and emotional reactions to them. Importantly, participants with a personal experience of racism are not more likely to engage in protest practices than those without personal experiences, regardless of having an emotional reaction afterwards or not. However, those who were told of experiences of racism by family, friends, or acquaintances are more likely to get engaged than those who were not told about others’ experiences. This association is even stronger among those who have reported an additional emotional reaction to their mediated experience of racism (see Table A1).

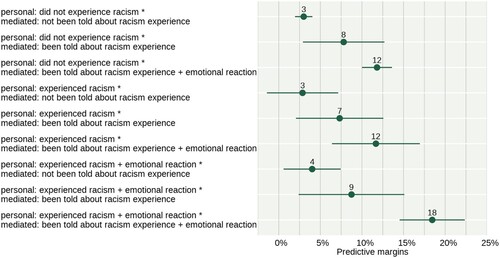

In , we further focus into the various interactions between personal and mediated racism experiences examined in . As the interactions show, personal experience of racism alone, even when it comes with emotional reaction (4 per cent), does not suffice to drive protest practice more than no experience at all (3 per cent). In contrast, having been told and feeling emotionally affected by these stories increases the likelihood of protesting irrespective of a personal experience of racism (12 per cent). Yet, those who have personally experienced racism and were told of experiences of racism by others are more likely to protest than those who only personally experienced racism. The differences are again substantial, jumping from 4.0 per cent (personal experience with emotional reaction, no mediated experience) to 18.0 per cent (personal experience with emotional reaction and mediated experience with emotional reaction). Accordingly, our data suggests, that when the personal experience of racism is communicatively and emotionally shared with others, it can have a mobilizing effect.

Figure 3. Predictive margins, interaction effects of direct and mediated experiences of racism, dependent variable = protest practice (in %, N = 4.854).

Note: Interaction effects between direct and mediated experiences, controlled for all predictors in the multinomial regression model; error bars indicate 95%-confidence intervals of predicted margins; results weighed by population parameters.

Protest potential

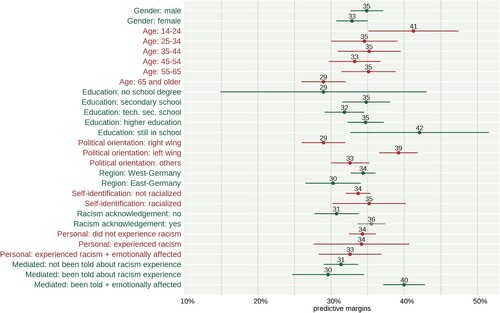

Turning to our second dependent variable – the mobilization potential for antiracist protest – summarizes the multivariate results. As in the previous model, gender, education, region of residency, and self-identification as a member of a racialized group do not increase the likelihood to get engaged. Age and political orientation again constitute significant predictors, where younger participants and those who vote for rather left-wing parties are more likely to potentially protest in the future.

Figure 4. Predictive margins, dependent variable = protest potential (in %, N = 4.854).

Note: Results of the multinomial regression analysis, controlled for all predictors in the model; error bars indicate 95%-confidence intervals of predicted margins; results weighed by population parameters.

Regarding cognitive and emotional drivers, we again find that those who acknowledge racism as a problem in Germany report more protest potential than those who do not acknowledge racism. Furthermore, people who personally experienced racism do not show more potential for protest than those who did not – irrespective of their emotional reaction to this.

In contrast, mediated experiences combined with an emotional reaction to these experiences turn out to be a strong predictor for protest potential. Those who report that they have been told about experiences of racism by others are twenty percentage points more likely to report willingness to get engaged if they were emotionally moved by these reports compared to when they did not react emotionally to them.

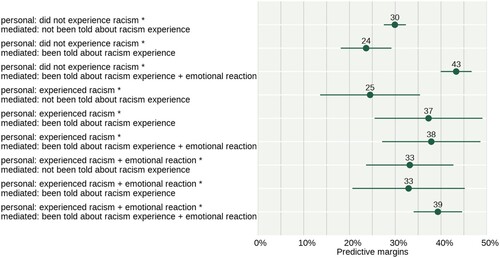

Lastly, inspecting the interactions between personal experience and mediated experience (), we find a marked difference compared to our results for protest practice. For protest potential, the additional mediated experience does not increase the willingness to protest racism. This is theoretically plausible. While protest practice involves higher efforts and risks, sharing experiences is more important than for the less demanding potential protest participation.

Figure 5. Predictive margins, interaction effects of direct and mediated experiences of racism, dependent variable = protest potential (in %, N = 4.854).

Note: Interaction effects between direct and mediated experiences, controlled for all predictors in the multinomial regression model; error bars indicate 95%-confidence intervals of predicted margins; results weighed by population parameters.

Discussion

This first assessment of antiracist protest practice and potential in Europe unveils both similarities and differences compared to the U.S. context.

The demographic distribution in Germany documents a disproportionately high practice and potential for antiracist collective action among young age groups and racialized groups. Our findings thereby echo research on antiracist protest in the U.S. and show marked differences to patterns of participation in protests in Germany, in which persons with migration background (which can serve as a rough proxy for racialized persons in Germany) are less frequently involved (Sommer, Steinhilper, and Zajak Citation2021; SVR-Forschungsbereich Citation2021). Furthermore, the findings for the predictive value of education deviate from the insights on protest participation on other issues. Whereas others have found a robust effect that higher education levels are strong predictors of protest practice in general (Dalton Citation2017; Sommer, Steinhilper, and Zajak Citation2021), our data suggests that the level of education does not predict engagement for the specific case antiracist protest in Germany. Accordingly, it seems to be a thematic context of collective action, which mobilizes and appeals to a more socially diverse part of society than other protests.

Moreover, the findings suggest that age and racial group status do not result as significant drivers in our multivariate models when the personal and mediated experiences of racism are considered. In addition, persons who report personal experiences of racism do not engage in more protest practice or potential than those who do not (disconfirming H1). However, alongside the cognitive acknowledgement of racism (confirming H2) and political orientation, reports of racist experiences by family, friends, or acquaintances drive protest participation and potential protest in the future (confirming H3). For the role of emotions, we find distinct patterns for personal and mediated experiences. While emotional reactions consistently increase the effect of mediated experiences, this is not the case for personal experiences (partly confirming H5). Lastly, the interactions between personal and mediated experience yield significant results for protest practice only (partly confirming H4), suggesting that both emotions and mediated experiences are more relevant for actual protest practice than mere protest potential. In a nutshell, the results indicate that solidarity through communicative exchange (i.e. mediated experiences), might be one of the mechanisms to overcome the potentially demobilizing effects of personal experiences of racism, which have been shown in previous research (Foster and Matheson Citation1998; Lems Citation2021).

These findings resonate with the social psychological processes that have previously been shown to increase engagement in collective action: a collectively shared experience can fuel a shared and collective identity among members of disadvantaged groups (Thomas, Zubielevitsch, and Osborne Citation2020), which can be a stronger motivator to protest than individual experiences of disadvantage or discrimination itself (Smith et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, being told about experiences of racism fuels protest behavior among white people who solidarize with those affected by racism (e.g. Subašić et al. Citation2018; Uluğ and Tropp Citation2021). Finally, protest aspirants or participants (independent of their racialized group status) acknowledge racism as a societal problem in Germany, resonant with research on the U.S. context (Azevedo, Marques, and Micheli Citation2022). This acknowledgement also indicates an increased perception of injustice and moral violation which has been shown to increase collective action intentions among advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Radke et al. Citation2020; Thomas, Zubielevitsch, and Osborne Citation2020).

In sum, whereas demographic variables of antiracist protesters and supporters seem to differ in Germany as compared to the U.S. due to contextual differences, the drivers of collective action are similar. In the current research, we highlight the role of personal and mediated experiences of racism and emotional reactions to them and show that being close to those directly affected is an important predictor of political engagement against racism. We thereby bridge recent insights from qualitative research on the role of emotions (Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022) to quantitative scholarship on drivers of antiracist mobilization.

Offering the first macroscopic view on patterns of antiracist protest in Germany, these results open various avenues for further analysis. First, given the timing of our survey, it is unclear how much the highly salient BLM mobilizations in 2020 drove the quantitative scope we have identified. Additional analysis, thus, could assess the dynamics of antiracist protest and protest potential over time. Second, this analysis has not differentiated between distinct kinds of emotions, which were found to be key in protest in general (Jasper Citation2011) and in antiracist protest in particular (Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022). Third, our tentative findings on the empowering role of communicative exchanges about experiences of racism highlight the value of including additional measures to survey-based research to assess where these exchanges take place. We assume that civil society organizations with a racially diverse membership and community organizations might be key in this regard. Lastly, while we could single-out similarities and differences between Germany and the U.S. context, additional research is needed to scrutinize intra-European variation. Based on existing research on the specific case of BLM in Europe, we suppose that the cognitive recognition of racism, (mediated) experiences and emotions matter in other European countries, too. Yet, given the differences in the levels of mobilization and the organizational structures (Beaman et al. Citation2023) within Europe, the patterns of antiracist mobilization require empirical scrutiny.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (39.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Elias Steinhilper acknowledges the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies (CES) at Harvard University for providing an ideal environment to draft this article and the 2023/2024 CES cohort for their valuable feedback on previous versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Question wording (authors’ translation from German): “Individuals can belong to different ethnic or cultural groups. How is it in your case? Do you belong to any of the following groups? Please mention all groups you belong to. (a) Asian people, (b) Jewish people, (c) Muslim people, (d) Sinti or Roma, (e) Eastern-European people, (f) Black people, (g) none of these groups.”

2 This question served as a filter for receiving questions about mediated experiences of being told about experiences of racist discrimination.

3 A closer examination suggests some variation between the different racialized groups that participated in the survey, although further analysis was not pursued due to the small subsample sizes.

4 A more detailed inspection showed a variation between these different groups, though further analysis were not traced due to small sample size.

References

- al-Samurai, N. L. 2004. “Neither Foreigners Nor Aliens: The Interwoven Stories of Sinti and Roma and Black Germans.” Women in German Yearbook (20), Article 163-183.

- Allport, G. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

- Azevedo, F., T. Marques, and L. Micheli. 2022. “In Pursuit of Racial Equality: Identifying the Determinants of Support for the Black Lives Matter Movement with a Systematic Review and Multiple Meta-Analyses.” Perspectives on Politics 20 (4): 1305–1327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001098.

- Banks, A. J., I. K. White, and B. D. McKenzie. 2019. “Black Politics: How Anger Influences the Political Actions Blacks Pursue to Reduce Racial Inequality.” Political Behavior 41 (4): 917–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9477-1.

- Baskin-Sommers, A., C. Simmons, M. Conley, S. an Chang, S. Estrada, M. Collins, W. Pelham, et al. 2021. “Adolescent Civic Engagement: Lessons from Black Lives Matter.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (41): 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2109860118.

- Beaman, J. 2021. “Towards a Reading of Black Lives Matter in Europe.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (S1): 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13275.

- Beaman, J., N. Doerr, P. Kocyba, A. Lavizzari, and S. Zajak. 2023. “Black Lives Matter and the new Wave of Anti-Racist Mobilizations in Europe.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 10 (4): 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2023.2274234.

- Bhattacharyya, G., S. Virdee, and A. Winter. 2020. “Revisiting Histories of Anti-Racist Thought and Activism.” Identities 27 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2019.1647686.

- Bojadzijev, M. 2008. Die windige Internationale Rassismus und Kämpfe der Migration. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

- Chin, R., and H. Fehrenbach. 2009. “Introduction. What’s Race Got to Do With It? Postwar German History in Context.” In After the Nazi Racial State: Difference and Democracy in Germany and Europe, edited by R. Chin, H. Fehrenbach, G. Eley, and A. Grossmann, 1–29. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Chin, R., H. Fehrenbach, G. Eley, and A. Grossmann. 2009. After the Nazi Racial State: Difference and Democracy in Germany and Europe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Dalton, R. J. 2017. The Participation Gap: Social Status and Political Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Daphi, P., S. Haunss, M. Sommer, and S. Teune. 2023. “Taking to the Streets in Germany – Disenchanted and Confident Critics in Mass Demonstrations.” German Politics 32 (3): 440–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.1998459.

- della Porta, D., A. Lavizzari, H. Reiter, M. Sommer, E. Steinhilper, and F. Ajayi. 2023. “Patterns of Adaptation and Recontextualization: The Transnational Diffusion of Black Lives Matter to Italy and Germany.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 10 (4): 653–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2023.2239324.

- Dunivin, Z. O., H. Y. Yan, J. Ince, and F. Rojas. 2022. “Black Lives Matter Protests Shift Public Discourse.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (10): e2117320119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117320119.

- El-Tayeb, F. 2020. “The Universal Museum.” Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 2020 (46): 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1215/10757163-8308198.

- Ellefsen, R., A. Banafsheh, and S. Sandberg. 2022. “Resisting Racism in Everyday Life: From Ignoring to Confrontation and Protest.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (16): 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2094716.

- Ellefsen, R., and S. Sandberg. 2022. “Black Lives Matter: The Role of Emotions in Political Engagement.” Sociology 56 (6): 1103–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385221081385.

- Fisher, D. R., and S. M. Rouse. 2022. “Intersectionality Within the Racial Justice Movement in the Summer of 2020.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (30): e2118525119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118525119.

- Florvil, T. N., ed. 2020. Black Internationalism Ser. Mobilizing Black Germany: Afro-German Women and the Making of a Transnational Movement. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press.

- Foroutan, N. 2019. “The Post-Migrant Paradigm.” In Refugees Welcome? Difference and Diversity in a Changing Germany, edited by J.-J. Bock, and S. Macdonald, 121–142. Oxford, New York: Berghahn.

- Foster, M. D., and K. Matheson. 1998. “Perceiving and Feeling Personal Discrimination: Motivation or Inhibition for Collective Action?” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 1 (2): 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430298012004.

- Häder, M., and S. Häder. 2014. “Stichprobenziehung in der quantitativen Sozialforschung.” In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, edited by N. Baur, and J. Blasius, 283–297. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Heaney, M. 2022. “Niche Realization in a Multimovement Environment Who Are Black Lives Matter Activists.” Perspectives on Politics 20 (4): 1362–1385. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001281.

- Hechler, S., M. Chayinska, C. S. Wekenborg, F. Moraga-Villablanca, T. Kessler, and C. McGarty. 2024. “Why Chile “Woke Up.” Antecedents of the Formation of Prochange Group Consciousness Promoting Collective Action.” Political Psychology 45 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12906.

- Hechler, S., and I. Essien. forthcoming. “Rassismus im Kontext rechtsextremer Ideologie.” In Psychologie der Rechtsradikalisierung –Theorien, Perspektiven, Prävention, edited by T. Rothemund, and E. Walther, 82–93. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. https://doi.org/10.17433/978-3-17-043998-6.

- Jasper, J. M. 2011. “Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 37 (1): 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150015.

- Klandermans, B., J. van Stekelenburg, and J. van der Toorn. 2008. “Embeddedness and Identity: How Immigrants Turn Grievances into Action.” American Sociological Review 73 (6): 992–1012.

- Lamont, M., G. M. Silva, J. Welburn, J. Guetzkow, N. Mizrachi, H. Herzog, and E. Reis. 2016. Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Leach, C. W., and A. M. Allen. 2017. “The Social Psychology of the Black Lives Matter Meme and Movement.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 26 (6): 543–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417719319.

- Lems, J. M. 2021. “Staying Silent or Speaking up: Reactions to Racialization Affecting Muslims in Madrid.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (7): 1192–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1779949.

- Lentin, A. 2004. Racism and Anti-Racism in Europe. Pluto Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0904/2003025962-b.html.

- Lentin, A. 2008. “After Anti-Racism?” European Journal of Cultural Studies 11 (3): 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549408091846.

- Matras, Y. 1998. “The Development of the Romani Civil Rights Movement in Germany 1945-1996.” In Sinti and Roma in German-Speaking Society and Literature, edited by S. Tebbutt, 49–63. Oxford, New York: Berghahn.

- McAdam, D. 1986. “Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer.” American Journal of Sociology 92 (1): 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/228463.

- Miller, S. S., C. J. O’Dea, and D. A. Saucier. 2021. “I Can’t Breathe”: Lay Conceptualizations of Racism Predict Support for Black Lives Matter.” Personality and Individual Differences 173:110625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110625.

- Milman, N., F. Ajayi, D. della Porta, N. Doerr, P. Kocyba, A. Lavizarri, H. Reiter, et al. 2021. Black Lives Matter in Europe: Transitional Diffusion, Local Translation and Resonance of Anti-Racist Protest in Germany, Italy, Denmark and Poland. DeZIM Research Notes (DeZIM Research Notes forthcoming). Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (DeZIM).

- Oguntoye, K., M. Opitz, and D. Schultz, eds. 1995. Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte. Frankfurt: Fischer.

- Oldfield, J. R. 2013. Transatlantic Abolitionism in the age of Revolution: An International History of Anti-Slavery, c. 1787-1820. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Perolini, M. 2022. “Challenging Oppression: How Grassroots Anti-Racism in Berlin Breaks Borders.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (8): 1475–1494. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1966066.

- Radke, H. R. M., M. Kutlaca, B. Siem, S. C. Wright, and J. C. Becker. 2020. “Beyond Allyship: Motivations for Advantaged Group Members to Engage in Action for Disadvantaged Groups.” Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc 24 (4): 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868320918698.

- Roig, E. 2017. “Uttering “Race” in Colorblind France and Post-Racial Germany.” In Rassismuskritik und Widerstandsformen, edited by K. Fereidooni, and M. El, 613–627. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Rojas, F., M. T. Heaney, and M. Adem. 2023. “Black Protesters in a White Social Movement: Looking to the Anti–Iraq War Movement to Develop a Theory of Racialized Activism.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 9: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231231157673.

- Selvanathan, H. P., P. Techakesari, L. R. Tropp, and F. K. Barlow. 2018. “Whites for Racial Justice: How Contact with Black Americans Predicts Support for Collective Action among White Americans.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21 (6): 893–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217690908.

- Simon, B., and B. Klandermans. 2001. “Politicized Collective Identity: A Social Psychological Analysis.” American Psychologist 56 (4): 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.4.319.

- Smith, H. J., T. F. Pettigrew, G. M. Pippin, and S. Bialosiewicz. 2012. “Relative Deprivation: A Theoretical and Meta-Analytic Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc 16 (3): 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311430825.

- Sommer, M., E. Steinhilper, and S. Zajak. 2021. “Wer protestiert? Das Profil von Protestierenden in Deutschland im Wandel.” In Zeitbild – „Protest, edited by M. Langebach, 44–63. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Steinhilper, E., T. J. Kim, T. J. Pöggel, and M. Sommer. 2024. “Antirassismus in Deutschland – soziale Bewegung und staatliche Politik.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 37 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/fjsb-2024-0001.

- Stjepandić, K., E. Steinhilper, and S. Zajak. 2023. “Forging Plural Coalitions in Times of Polarisation: Protest for an Open Society in Germany.” German Politics 32 (3): 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2023130.

- Subašić, E., S. Hardacre, B. Elton, N. R. Branscombe, M. K. Ryan, and K. J. Reynolds. 2018. “We for She”: Mobilising men and Women to act in Solidarity for Gender Equality.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21 (5): 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218763272.

- SVR-Forschungsbereich. 2021. Mitten im Spiel – oder nur an der Seitenlinie? Politische Partizipation und zivilgesellschaftliches Engagement von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration.

- Thomas, E. F., K. I. Mavor, and C. McGarty. 2012. “Social Identities Facilitate and Encapsulate Action-Relevant Constructs.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 15 (1): 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430211413619.

- Thomas, E. F., E. Zubielevitsch, and D. Osborne. 2020. “Testing the Social Identity Model of Collective Action Longitudinally and Across Structurally Disadvantaged and Advantaged Groups.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 46 (6): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672198791.

- Uluğ, ÖM, and L. R. Tropp. 2021. “Witnessing Racial Discrimination Shapes Collective Action for Racial Justice: Enhancing Awareness of Privilege among Advantaged Groups.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 51 (3): 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12731.

- Woodly, D. 2022. Reckoning. Black Lives Matter and the Democratic Necessity of Social Movements. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zajak, S., E. Steinhilper, and M. Sommer. 2023. “Agenda Setting and Selective Resonance – Black Lives Matter and Media Debates on Racism in Germany.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 10 (4): 552–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2023.2176335.

- Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma. 2017. 45 Jahre Bürgerrechtsarbeit deutscher Sinti und Roma / 45 years of civil rights work of German Sinti and Roma. Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma.